In

United States history, the Gilded Age was an era extending roughly from 1877 to 1900, which was sandwiched between the

Reconstruction era and the

Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s – late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

. It was a time of rapid economic growth, especially in the

Northern and

Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

United States. As American wages grew much higher than those in Europe, especially for skilled workers, and

industrialization demanded an ever-increasing unskilled labor force, the period saw an influx of millions of European immigrants.

The rapid expansion of industrialization led to

real wage

Real wages are wages adjusted for inflation, or, equivalently, wages in terms of the amount of goods and services that can be bought. This term is used in contrast to nominal wages or unadjusted wages.

Because it has been adjusted to account ...

growth of 60% between 1860 and 1890, and spread across the ever-increasing labor force. The average annual wage per industrial worker (including men, women, and children) rose from $380 in 1880, to $564 in 1890, a gain of 48%.

Conversely, the Gilded Age was also an era of

abject poverty and inequality, as millions of immigrants—many from impoverished regions—poured into the United States, and the high

concentration of wealth became more visible and contentious.

Railroads

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a prep ...

were the major growth industry, with the factory system, mining, and finance increasing in importance. Immigration from Europe, and the

Eastern United States

The Eastern United States, commonly referred to as the American East, Eastern America, or simply the East, is the region of the United States to the east of the Mississippi River. In some cases the term may refer to a smaller area or the East C ...

, led to the rapid growth of the West, based on farming, ranching, and mining. Labor unions became increasingly important in the rapidly growing industrial cities. Two major nationwide depressions—the

Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

and the

Panic of 1893—interrupted growth and caused social and political upheavals.

The

South remained economically devastated after the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

; the region's economy became increasingly tied to commodities, cotton, and tobacco production, which suffered from low prices. With the end of the

Reconstruction era in 1877, African American people in the South were stripped of political power and voting rights and were left economically disadvantaged.

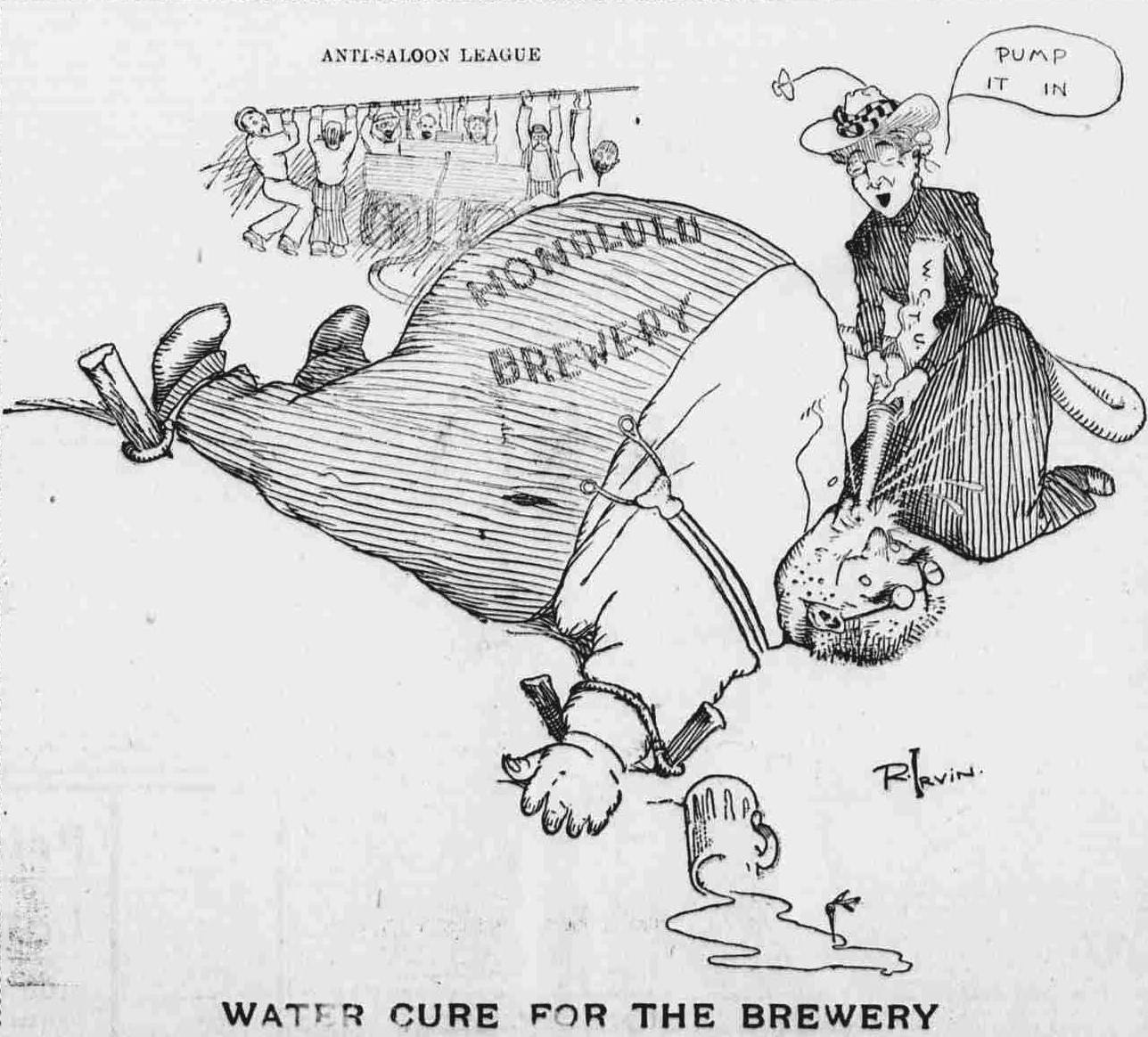

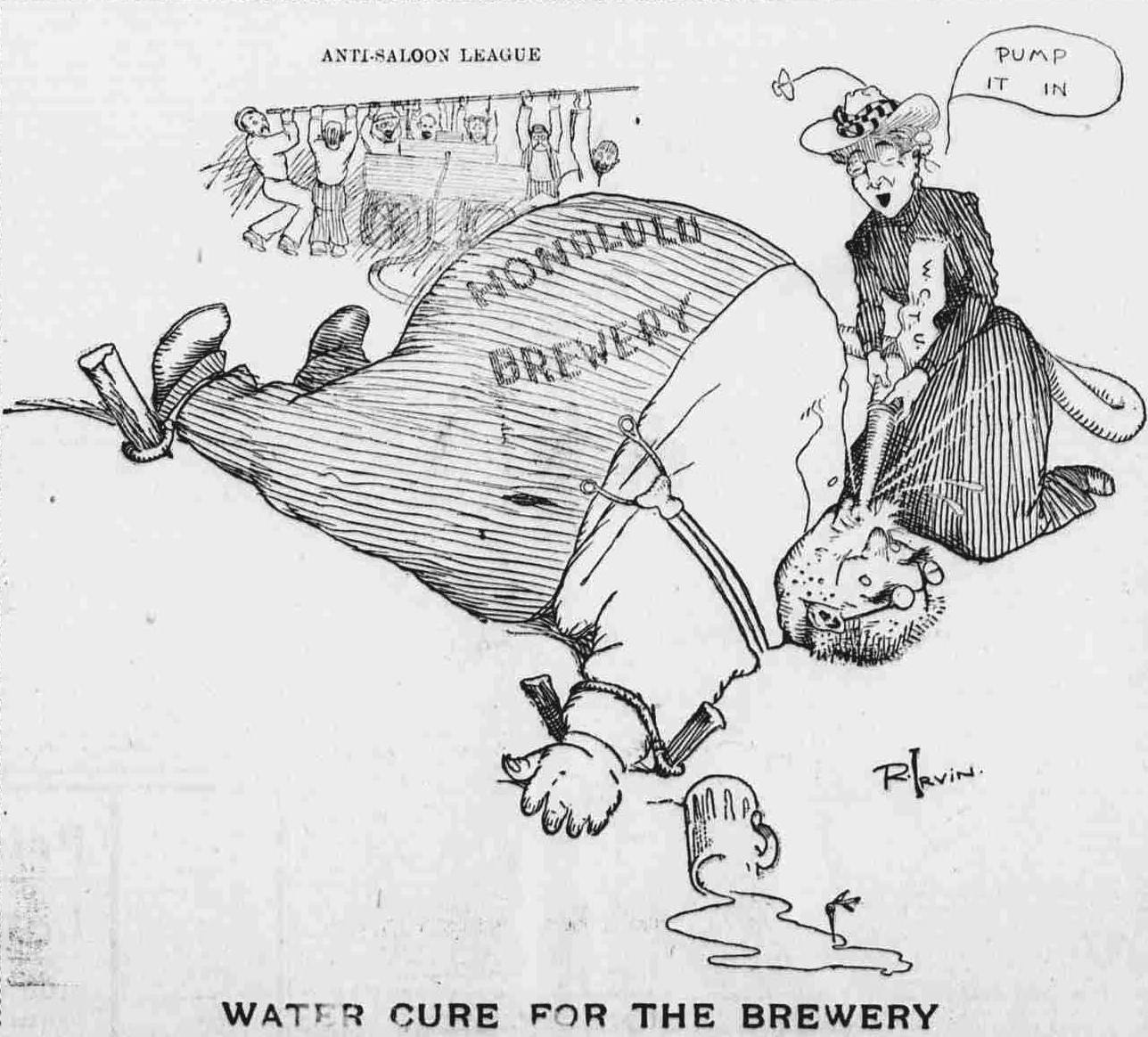

The political landscape was notable in that despite some corruption, election turnout was very high and national elections saw two evenly matched parties. The dominant issues were cultural (especially regarding

prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcohol ...

, education, and ethnic or racial groups) and economic (tariffs and money supply). With the rapid growth of cities,

political machines increasingly took control of urban politics. In business, powerful nationwide

trusts

A trust is a legal relationship in which the holder of a right gives it to another person or entity who must keep and use it solely for another's benefit. In the Anglo-American common law, the party who entrusts the right is known as the "settl ...

formed in some industries. Unions crusaded for the

eight-hour working day, and the abolition of

child labor

Child labour refers to the exploitation of children through any form of work that deprives children of their childhood, interferes with their ability to attend regular school, and is mentally, physically, socially and morally harmful. Such e ...

; middle class reformers demanded

civil service reform, prohibition of liquor and beer, and

women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

.

Local governments across the North and West built public schools chiefly at the elementary level; public high schools started to emerge. The numerous religious denominations were growing in membership and wealth, with

Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

becoming the largest. They all expanded their missionary activity to the world arena. Catholics,

Lutherans

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched ...

, and

Episcopalians set up religious schools, and the larger of those set up numerous colleges, hospitals, and charities. Many of the problems faced by society, especially the poor, gave rise to attempted reforms in the subsequent

Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s – late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

.

The "Gilded Age" term came into use in the 1920s and 1930s and was derived from writer

Mark Twain and

Charles Dudley Warner

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was " ...

's 1873 novel ''

The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today'', which satirized an era of serious social problems masked by a thin gold

gilding. The early half of the Gilded Age roughly coincided with the mid-

Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardia ...

in Britain and the

Belle Époque in France. Its beginning, in the years after the American Civil War, overlaps the Reconstruction Era (which ended in 1877).

[Nichols, Christopher M.; Nancy C. Unger (2017). ''A Companion to the Gilded Age and Progressive Era''. Wiley, p. 7.] It was followed in the 1890s by the Progressive Era.

The name and the era

The ''Gilded Age'', the term for the period of economic boom which began after the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

and ended at the turn of the century was applied to the era by historians in the 1920s, who took the term from one of

Mark Twain's lesser-known novels, ''

The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today'' (1873). The book (co-written with

Charles Dudley Warner

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was " ...

) satirized the promised "

golden age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the '' Works and Days'' of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages, Gold being the first and the one during which the G ...

" after the Civil War, portrayed as an era of serious social problems masked by a thin

gold gilding of economic expansion.

In the 1920s and 1930s the metaphor "Gilded Age" began to be applied to a designated

period

Period may refer to:

Common uses

* Era, a length or span of time

* Full stop (or period), a punctuation mark

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Period (music), a concept in musical composition

* Periodic sentence (or rhetorical period), a concept ...

in American history. The term was adopted by literary and cultural critics as well as historians, including

Van Wyck Brooks

Van Wyck Brooks (February 16, 1886 in Plainfield, New Jersey – May 2, 1963 in Bridgewater, Connecticut) was an American literary critic, biographer, and historian.

Biography

Brooks graduated from Harvard University in 1908. As a student ...

,

Lewis Mumford

Lewis Mumford (October 19, 1895 – January 26, 1990) was an American historian, sociologist, philosopher of technology, and literary critic. Particularly noted for his study of cities and urban architecture, he had a broad career as a w ...

,

Charles Austin Beard,

Mary Ritter Beard

Mary Ritter Beard (August 5, 1876 – August 14, 1958) was an American historian, author, women's suffrage activist, and women's history archivist who was also a lifelong advocate of social justice. As a Progressive Era reformer, Beard was ...

,

Vernon Louis Parrington, and

Matthew Josephson. For them, ''Gilded Age'' was a pejorative term for a time of materialistic excesses combined with extreme poverty.

The early half of the Gilded Age roughly coincided with the middle portion of the

Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardia ...

in Britain and the

Belle Époque in France. With respect to eras of American history, historical views vary as to when the Gilded Age began, ranging from starting right after the Civil War ended in 1865, or 1873, or as the

Reconstruction Era ended in 1877.

The date marking the end of the Gilded Age also varies. The ending is generally given as the beginning of the

Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s – late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

in the 1890s (sometimes the

United States presidential election of 1896).

Industrial and technological advances

Technical advances

The Gilded Age was a period of economic growth as the United States jumped to the lead in

industrialization ahead of Britain. The nation was rapidly expanding its economy into new areas, especially

heavy industry

Heavy industry is an industry that involves one or more characteristics such as large and heavy products; large and heavy equipment and facilities (such as heavy equipment, large machine tools, huge buildings and large-scale infrastructure); o ...

like factories,

railroads

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a prep ...

, and

coal mining. In 1869, the

First transcontinental railroad opened up the far-west mining and ranching regions. Travel from New York to San Francisco then took six days instead of six months.

[Stephen E. Ambrose, ''Nothing Like It in the World; The Men Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad 1863–1869'' (2000)] Railroad track mileage tripled between 1860 and 1880, and then doubled again by 1920. The new track linked formerly isolated areas with larger markets and allowed for the rise of commercial farming, ranching, and mining, creating a truly national marketplace. American steel production rose to surpass the combined totals of Britain, Germany, and France.

Investors in London and Paris poured money into the railroads through the American financial market centered in

Wall Street. By 1900, the process of economic concentration had extended into most branches of industry—a few large corporations, called "

trusts

A trust is a legal relationship in which the holder of a right gives it to another person or entity who must keep and use it solely for another's benefit. In the Anglo-American common law, the party who entrusts the right is known as the "settl ...

", dominated in steel, oil, sugar, meat, and farm machinery. Through

vertical integration

In microeconomics, management and international political economy, vertical integration is a term that describes the arrangement in which the supply chain of a company is integrated and owned by that company. Usually each member of the suppl ...

these trusts were able to control each aspect of the production of a specific good, ensuring that the profits made on the finished product were maximized and prices minimized, and by controlling access to the raw materials, prevented other companies from being able to compete in the marketplace. Several monopolies—most famously

Standard Oil—came to dominate their markets by keeping prices low when competitors appeared; they grew at a rate four times faster than that of the competitive sectors.

Increased mechanization of industry is a major mark of the Gilded Age's search for cheaper ways to create more product.

Frederick Winslow Taylor

Frederick Winslow Taylor (March 20, 1856 – March 21, 1915) was an American mechanical engineer. He was widely known for his methods to improve industrial efficiency. He was one of the first management consultants. In 1909, Taylor summed up ...

observed that worker efficiency in steel could be improved through the use of very close observations with a stop watch to eliminate wasted effort. Mechanization made some factories an assemblage of unskilled laborers performing simple and repetitive tasks under the direction of skilled foremen and engineers. Machine shops grew rapidly, and they comprised highly skilled workers and engineers. Both the number of unskilled and skilled workers increased, as their wage rates grew.

Engineering colleges were established to feed the enormous demand for expertise, many through the Federal government sponsored

Morrill Land-Grant Acts

The Morrill Land-Grant Acts are United States statutes that allowed for the creation of land-grant colleges in U.S. states using the proceeds from sales of federally-owned land, often obtained from indigenous tribes through treaty, cession, or s ...

passed to stimulate public education, particularly in the agricultural and technical ("Ag & Tech") fields. Railroads, which had previously invented

railroad time to standardize time zones, production, and lifestyles, created modern management, with clear chains of command, statistical reporting, and complex bureaucratic systems. They systematized the roles of

middle managers and set up explicit career tracks for both skilled blue-collar jobs and for white-collar managers. These advances spread from railroads into finance, manufacturing, and trade. Together with rapid growth of small business, a new middle class was rapidly growing, especially in northern cities.

The nation became a world leader in applied technology. From 1860 to 1890, 500,000 patents were issued for new inventions—over ten times the number granted in the previous seventy years.

George Westinghouse

George Westinghouse Jr. (October 6, 1846 – March 12, 1914) was an American entrepreneur and engineer based in Pennsylvania who created the railway air brake and was a pioneer of the electrical industry, receiving his first patent at the age ...

invented

air brakes for trains (making them both safer and faster).

Theodore Vail

Theodore Newton Vail (July 16, 1845 – April 16, 1920) was president of American Telephone & Telegraph between 1885 and 1889, and again from 1907 to 1919. Vail saw telephone service as a public utility and moved to consolidate telephone networks u ...

established the

American Telephone & Telegraph Company and built a great communications network.

Elisha Otis developed the elevator, allowing the construction of

skyscrapers

A skyscraper is a tall continuously habitable building having multiple floors. Modern sources currently define skyscrapers as being at least or in height, though there is no universally accepted definition. Skyscrapers are very tall high-ri ...

and the concentration of ever greater populations in urban centers.

Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February 11, 1847October 18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventi ...

, in addition to inventing hundreds of devices, established the first electrical lighting utility, basing it on

direct current

Direct current (DC) is one-directional flow of electric charge. An electrochemical cell is a prime example of DC power. Direct current may flow through a conductor such as a wire, but can also flow through semiconductors, insulators, or eve ...

and an efficient

incandescent lamp. Electric power delivery spread rapidly across Gilded Age cities. The streets were lighted at night, and electric streetcars allowed for faster commuting to work and easier shopping.

[

]

Petroleum launched a new industry beginning with the Pennsylvania oil fields in the 1860s. The United States dominated the global industry into the 1950s.

Kerosene

Kerosene, paraffin, or lamp oil is a combustible hydrocarbon liquid which is derived from petroleum. It is widely used as a fuel in aviation as well as households. Its name derives from el, κηρός (''keros'') meaning "wax", and was regi ...

replaced

whale oil

Whale oil is oil obtained from the blubber of whales. Whale oil from the bowhead whale was sometimes known as train oil, which comes from the Dutch word ''traan'' (" tear" or "drop").

Sperm oil, a special kind of oil obtained from the head ...

and candles for lighting homes.

John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American business magnate and philanthropist. He has been widely considered the wealthiest American of all time and the richest person in modern history. Rockefeller was ...

founded Standard Oil Company and monopolized the oil industry. It mostly produced kerosene before the automobile created a demand for gasoline in the 20th century.

Railroads

According to historian

Henry Adams the system of railroads needed:

:the energies of a generation, for it required all the new machinery to be created—capital, banks, mines, furnaces, shops, power-houses, technical knowledge, mechanical population, together with a steady remodelling of social and political habits, ideas, and institutions to fit the new scale and suit the new conditions. The generation between 1865 and 1895 was already mortgaged to the railways, and no one knew it better than the generation itself.

The impact can be examined through five aspects: shipping, finance, management, careers, and popular reaction.

Shipping freight and passengers

Railroads provided a highly efficient network for shipping freight and passengers throughout the U.S., spurring the evolution of a large national market. This had a transformative impact on most sectors of the economy including manufacturing, retail and wholesale, agriculture, and finance. The result was an integrated market practically the size of Europe's, with no internal barriers, tariffs, or language barriers to hamper it, and a common financial and legal system to support it.

Basis of the private financial system

Railroad financing provided the basis for a dramatic expansion of the private financial system. Construction of railroads was far more expensive than factories. In 1860, the combined total of railroad stocks and bonds was $1.8 billion; 1897 it reached $10.6 billion (compared to a total national debt of $1.2 billion). Funding came primarily from private finance throughout the Northeast, and from Europe, especially Britain, with about 10 percent coming from the Federal government, especially in the form of land grants that could be realized when a certain amount of trackage was opened. The emerging American financial system was based on railroad bonds. By 1860, New York was the dominant financial market. The British invested heavily in railroads around the world, but nowhere more so than the United States; The total came to about $3 billion by 1914. In 1914–1917, they liquidated their American assets to pay for war supplies.

Inventing modern management

Railroad management designed complex systems that could handle far more complicated simultaneous relationships than could be dreamed of by the local factory owner who could patrol every part of his own factory in a matter of hours. Civil engineers became the senior management of railroads. The leading innovators were the

Western Railroad of Massachusetts and the

Baltimore and Ohio Railroad in the 1840s, the

Erie

Erie (; ) is a city on the south shore of Lake Erie and the county seat of Erie County, Pennsylvania, United States. Erie is the fifth largest city in Pennsylvania and the largest city in Northwestern Pennsylvania with a population of 94,831 a ...

in the 1850s, and the

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

in the 1860s.

Career paths

The railroads invented the career path in the private sector for both blue- and white-collar workers. Railroading became a lifetime career for young men; women were almost never hired. A typical career path would see a young man hired at age 18 as a shop laborer, be promoted to skilled mechanic at age 24, brakemen at 25, freight conductor at 27, and passenger conductor at age 57. White-collar careers paths likewise were delineated. Educated young men started in clerical or statistical work and moved up to station agents or bureaucrats at the divisional or central headquarters.

At each level they had more and more knowledge, experience, and

human capital. They were very hard to replace, and were virtually guaranteed permanent jobs and provided with insurance and medical care. Hiring, firing, and wage rates were set not by foremen, but by central administrators, to minimize favoritism and personality conflicts. Everything was done by the book, whereby an increasingly complex set of rules dictated to everyone exactly what should be done in every circumstance, and exactly what their rank and pay would be. By the 1880s the career railroaders were retiring, and pension systems were invented to provide for them.

Love-hate relationship with the railroads

America developed a love-hate relationship with railroads.

Boosters in every city worked feverishly to make sure the railroad came through, knowing their urban dreams depended upon it. The mechanical size, scope, and efficiency of the railroads made a profound impression; people dressed in their Sunday best to go down to the terminal to watch the train come in. Travel became much easier, cheaper, and more common. Shoppers from small towns could make day trips to big city stores. Hotels, resorts, and tourist attractions were built to accommodate the demand. The realization that anyone could buy a ticket for a thousand-mile trip was empowering. Historians Gary Cross and Rick Szostak argue:

: With the freedom to travel came a greater sense of national identity and a reduction in regional cultural diversity. Farm children could more easily acquaint themselves with the big city, and easterners could readily visit the West. It is hard to imagine a United States of continental proportions without the railroad.

The civil and mechanical engineers became model citizens, bringing their can-do spirit and their systematic work effort to all phases of the economy as well as local and national government. By 1910, major cities were building magnificent palatial railroad stations, such as the

Pennsylvania Station

Pennsylvania Station (often abbreviated Penn Station) is a name applied by the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) to several of its grand passenger terminals. Several are still in active use by Amtrak and other transportation services; others have been ...

in New York City, and the

Union Station

A union station (also known as a union terminal, a joint station in Europe, and a joint-use station in Japan) is a railway station at which the tracks and facilities are shared by two or more separate railway companies, allowing passengers to ...

in Washington, D.C.

But there was also a dark side. By the 1870s railroads were vilified by Western farmers who absorbed the

Granger movement theme that monopolistic carriers controlled too much pricing power, and that the state legislatures had to regulate maximum prices. Local merchants and shippers supported the demand and got some "

Granger Laws" passed. Anti-railroad complaints were loudly repeated in late 19th century political rhetoric.

One of the most hated railroad men in the country was

Collis P. Huntington (1821–1900), the president of the

Southern Pacific Railroad, who dominated California's economy and politics. One textbook argues: "Huntington came to symbolize the greed and corruption of late-nineteenth-century business. Business rivals and political reformers accused him of every conceivable evil. Journalists and cartoonists made their reputations by pillorying him.... Historians have cast Huntington as the state's most despicable villain." However Huntington defended himself: "The motives back of my actions have been honest ones and the results have redounded far more to the benefit of California than they have to my own."

Impact on farming

The growth of railroads from 1850s to 1880s made commercial farming much more feasible and profitable. Millions of acres were opened to settlement once the railroad was nearby, and provided a long-distance outlet for wheat, cattle and hogs that reached all the way to Europe. Rural America became one giant market, as wholesalers bought the consumer products produced by the factories in the East and shipped them to local merchants in small stores nationwide. Shipping live animals was slow and expensive. It was more efficient to slaughter them in major packing centers such as Chicago, Kansas City, St. Louis, Milwaukee, and Cincinnati, and then ship dressed meat out in refrigerated freight cars. The cars were cooled by slabs of ice that had been harvested from the northern lakes in wintertime, and stored for summer and fall usage. Chicago, the main railroad center, benefited enormously, with Kansas City a distant second. Historian

William Cronon

William Cronon (born September 11, 1954 in New Haven, Connecticut) is an environmental historian and the Frederick Jackson Turner and Vilas Research Professor of History, Geography, and Environmental Studies at the University of Wisconsin–Madi ...

concludes:

:Because of the Chicago packers, ranchers in Wyoming and feedlot farmers in Iowa regularly found a reliable market for their animals, and on average received better prices for the animals they sold there. At the same time and for the same reason, Americans of all classes found a greater variety of more and better meats on their tables, purchased on average at lower prices than ever before. Seen in this light, the packers' "rigid system of economy" seemed a very good thing indeed.

Economic growth

During the 1870s and 1880s, the U.S. economy rose at the fastest rate in its history, with real wages, wealth, GDP, and

capital formation

Capital formation is a concept used in macroeconomics, national accounts and financial economics. Occasionally it is also used in corporate accounts. It can be defined in three ways:

*It is a specific statistical concept, also known as net inve ...

all increasing rapidly. For example, between 1865 and 1898, the output of wheat increased by 256%, corn by 222%, coal by 800%, and miles of railway track by 567%. Thick national networks for transportation and communication were created. The corporation became the dominant form of business organization, and a

scientific management revolution transformed business operations.

By the beginning of the 20th century, gross domestic product and industrial production in the United States led the world. Kennedy reports that "U.S. national income, in absolute figures in per capita, was so far above everybody else's by 1914." Per capita income in the United States was $377 in 1914 compared to Britain in second place at $244, Germany at $184, France at $153, and Italy at $108, while Russia and Japan trailed far behind at $41 and $36.

London remained the financial center of the world until 1914, yet the United States' growth caused foreigners to ask, as British author

W. T. Stead wrote in 1901, "What is the secret of American success?"

The businessmen of the

Second Industrial Revolution

The Second Industrial Revolution, also known as the Technological Revolution, was a phase of rapid scientific discovery, standardization, mass production and industrialization from the late 19th century into the early 20th century. The Fi ...

created industrial towns and cities in the

Northeast with new factories, and hired an ethnically diverse industrial working class, many of them new immigrants from Europe.

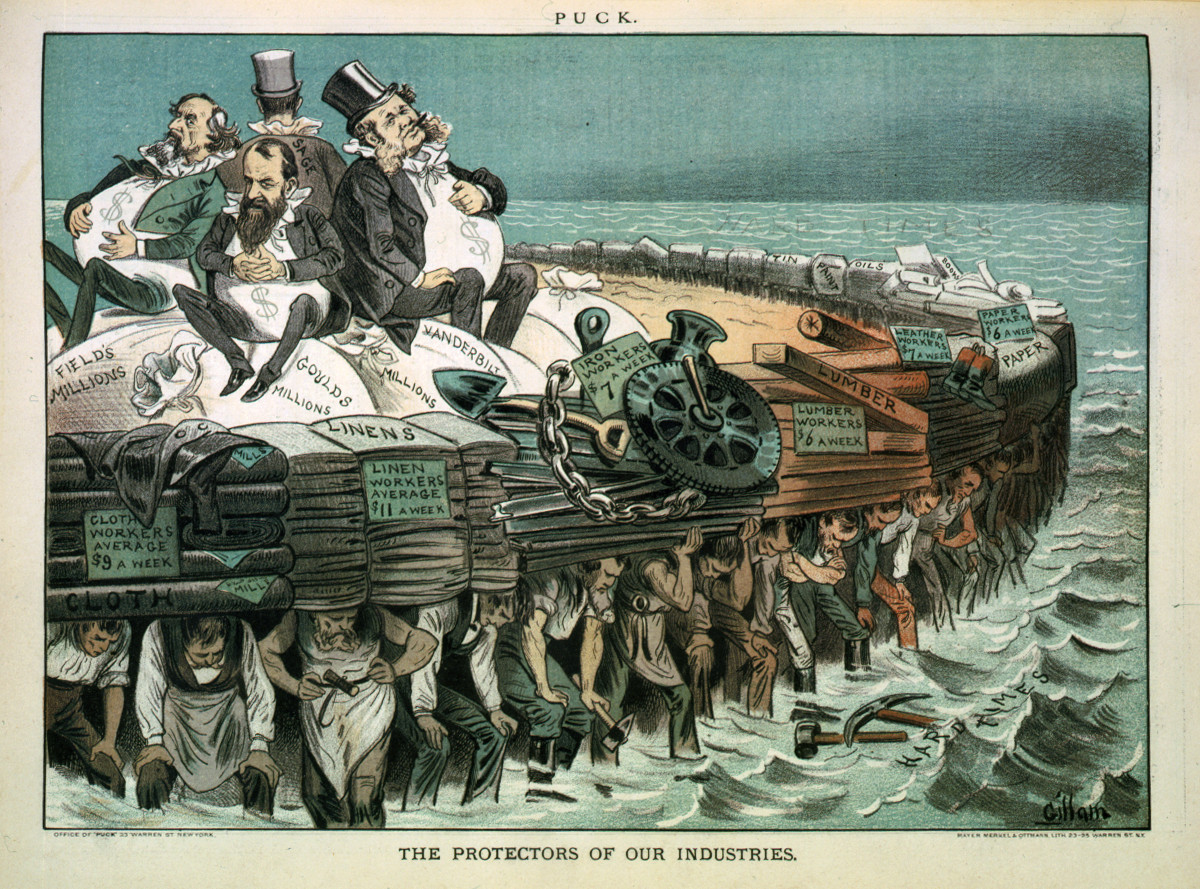

Wealthy industrialists and financiers such as

John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American business magnate and philanthropist. He has been widely considered the wealthiest American of all time and the richest person in modern history. Rockefeller was ...

,

Jay Gould

Jason Gould (; May 27, 1836 – December 2, 1892) was an American railroad magnate and financial speculator who is generally identified as one of the robber barons of the Gilded Age. His sharp and often unscrupulous business practices made him ...

,

Henry Clay Frick

Henry Clay Frick (December 19, 1849 – December 2, 1919) was an American industrialist, financier, and art patron. He founded the H. C. Frick & Company coke manufacturing company, was chairman of the Carnegie Steel Company, and played a maj ...

,

Andrew Mellon

Andrew William Mellon (; March 24, 1855 – August 26, 1937), sometimes A. W. Mellon, was an American banker, businessman, industrialist, philanthropist, art collector, and politician. From the wealthy Mellon family of Pittsburgh, Pennsylv ...

,

Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie (, ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans i ...

,

Henry Flagler,

Henry Huttleston Rogers,

J. P. Morgan

John Pierpont Morgan Sr. (April 17, 1837 – March 31, 1913) was an American financier and investment banker who dominated corporate finance on Wall Street throughout the Gilded Age. As the head of the banking firm that ultimately became known ...

,

Leland Stanford,

Meyer Guggenheim,

Jacob Schiff

Jacob (; ; ar, يَعْقُوب, Yaʿqūb; gr, Ἰακώβ, Iakṓb), later given the name Israel, is regarded as a patriarch of the Israelites and is an important figure in Abrahamic religions, such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Ja ...

,

Charles Crocker, and

Cornelius Vanderbilt

Cornelius Vanderbilt (May 27, 1794 – January 4, 1877), nicknamed "the Commodore", was an American business magnate who built his wealth in railroads and shipping. After working with his father's business, Vanderbilt worked his way into lead ...

would sometimes be labeled "

robber barons" by their critics, who argue their fortunes were made at the expense of the working class, by chicanery and a betrayal of democracy. Their admirers argued that they were "Captains of Industry" who built the core America industrial economy and also the non-profit sector through acts of philanthropy. For instance, Andrew Carnegie donated over 90% of his wealth and said that philanthropy was their duty—the "

Gospel of Wealth". Private money endowed thousands of colleges, hospitals, museums, academies, schools, opera houses, public libraries, and charities.

John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American business magnate and philanthropist. He has been widely considered the wealthiest American of all time and the richest person in modern history. Rockefeller was ...

donated over $500 million to various charities, slightly over half his entire net worth. Reflecting this, many business leaders were influenced by

Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English philosopher, psychologist, biologist, anthropologist, and sociologist famous for his hypothesis of social Darwinism. Spencer originated the expression " survival of the fi ...

's theory of

social Darwinism

Social Darwinism refers to various theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economics and politics, and which were largely defined by scholars in We ...

, which justified ''

laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups ...

'' capitalism, competition and

social stratification.

This emerging industrial economy quickly expanded to meet the new market demands. From 1869 to 1879, the U.S. economy grew at a rate of 6.8% for NNP (GDP minus capital depreciation) and 4.5% for NNP per capita. The economy repeated this period of growth in the 1880s, in which the wealth of the nation grew at an annual rate of 3.8%, while the GDP was also doubled.

Libertarian economist

Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (; July 31, 1912 – November 16, 2006) was an American economist and statistician who received the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his research on consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and the ...

states that for the 1880s, "The highest decadal rate

f growth of real reproducible, tangible wealth per head from 1805 to 1950for periods of about ten years was apparently reached in the eighties with approximately 3.8 percent."

Wages

The rapid expansion of industrialization led to real wage growth of 60% between 1860 and 1890, spread across the ever-increasing labor force. Real wages (adjusting for inflation) rose steadily, with the exact percentage increase depending on the dates and the specific work force. The Census Bureau reported in 1892 that the average annual wage per industrial worker (including men, women, and children) rose from $380 in 1880 to $564 in 1890, a gain of 48%.

Economic historian Clarence D. Long estimates that (in terms of constant 1914 dollars), the average annual incomes of all American non-farm employees rose from $375 in 1870 to $395 in 1880, $519 in 1890 and $573 in 1900, a gain of 53% in 30 years.

Australian historian

Peter Shergold found that the standard of living for industrial workers was higher than in Europe. He compared wages and the standard of living in Pittsburgh with Birmingham, England, one of the richest industrial cities of Europe. After taking account of the cost of living (which was 65% higher in the U.S.), he found the standard of living of unskilled workers was about the same in the two cities, while skilled workers in Pittsburgh had about 50% to 100% higher standard of living as those in Birmingham, England. Warren B. Catlin proposed that the natural resources and virgin lands that were available in America acted as a safety valve for poorer workers, hence, employers had to pay higher wages to hire labor. According to Shergold the American advantage grew over time from 1890 to 1914, and the perceived higher American wage led to a heavy steady flow of skilled workers from Britain to industrial America. According to historian Steve Fraser, workers generally earned less than $800 a year, which kept them mired in poverty. Workers had to put in roughly 60 hours a week to earn this much.

was widely condemned as

'wage slavery' in the working class press, and labor leaders almost always used the phrase in their speeches.

As the shift towards wage labor gained momentum, working class organizations became more militant in their efforts to "strike down the whole system of wages for labor."

In 1886, economist and New York Mayoral candidate

Henry George

Henry George (September 2, 1839 – October 29, 1897) was an American political economist and journalist. His writing was immensely popular in 19th-century America and sparked several reform movements of the Progressive Era. He inspired the eco ...

, author of ''

Progress and Poverty

''Progress and Poverty: An Inquiry into the Cause of Industrial Depressions and of Increase of Want with Increase of Wealth: The Remedy'' is an 1879 book by social theorist and economist Henry George. It is a treatise on the questions of why pover ...

'', stated "Chattel slavery is dead, but industrial slavery remains."

Wealth disparity

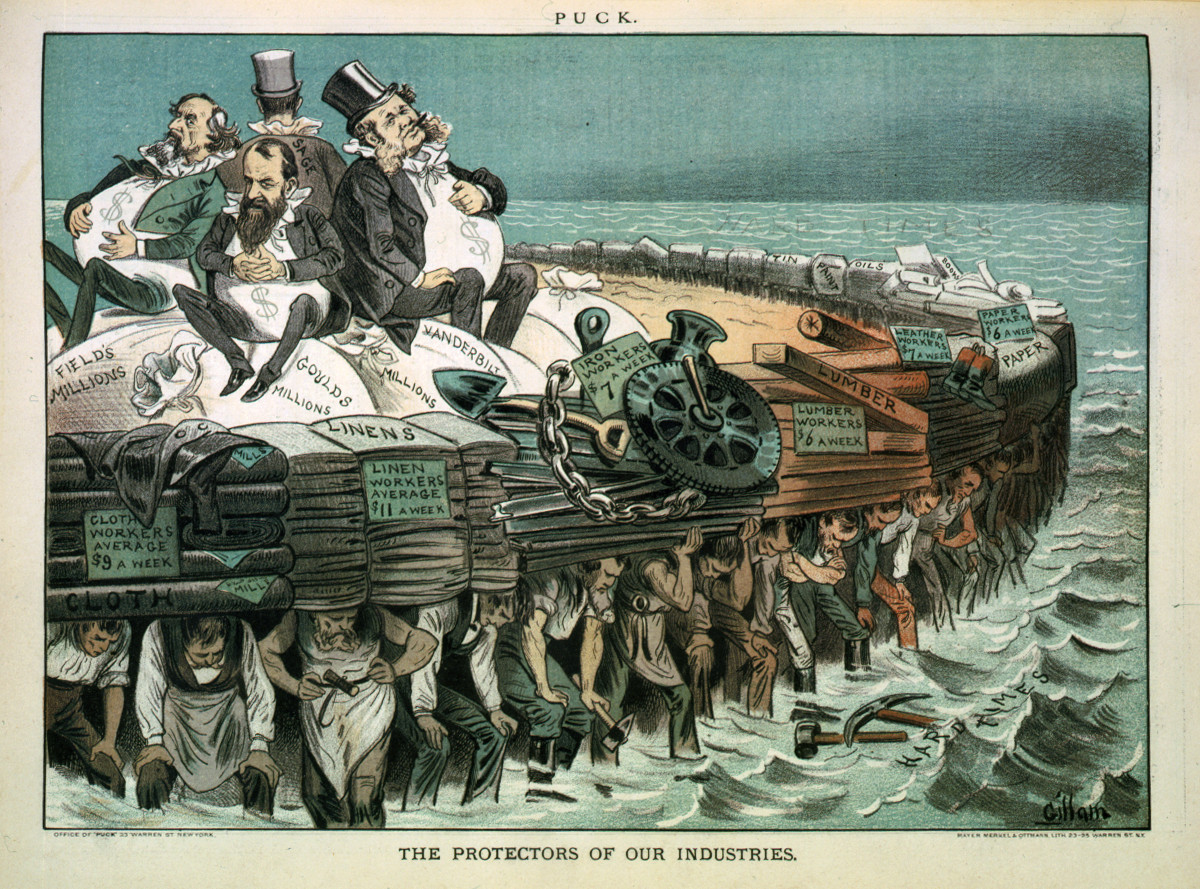

The unequal

distribution of wealth

The distribution of wealth is a comparison of the wealth of various members or groups in a society. It shows one aspect of economic inequality or economic heterogeneity.

The distribution of wealth differs from the income distribution in that ...

remained high during this period. From 1860 to 1900, the wealthiest 2% of American households owned more than a third of the nation's wealth, while the top 10% owned roughly three-quarters of it. The bottom 40% had no wealth at all.

In terms of property, the wealthiest 1% owned 51%, while the bottom 44% claimed 1.1%.

Historian

Howard Zinn

Howard Zinn (August 24, 1922January 27, 2010) was an American historian, playwright, philosopher, socialist thinker and World War II veteran. He was chair of the history and social sciences department at Spelman College, and a politica ...

argues that this disparity along with precarious working and living conditions for the working classes prompted the rise of

populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term develop ...

,

anarchist, and

socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

movements. French economist

Thomas Piketty

Thomas Piketty (; born 7 May 1971) is a French economist who is Professor of Economics at the School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences, Associate Chair at the Paris School of Economics and Centennial Professor of Economics in the I ...

notes that economists during this time, such as

Willford I. King, were concerned that the United States was becoming increasingly inegalitarian to the point of becoming like old Europe, and "further and further away from its original pioneering ideal."

According to economist

Richard Sutch in an alternative view of the era, the bottom 25% owned 0.32% of the wealth while the top 0.1% owned 9.4%, which would mean the period had the lowest wealth gap in recorded history. He attributes this to the lack of government interference.

There was a significant human cost attached to this period of economic growth, as American industry had the highest rate of accidents in the world.

In 1889, railroads employed 704,000 men, of whom 20,000 were injured and 1,972 were killed on the job. The U.S. was also the only industrial power to have no workman's compensation program in place to support injured workers.

[Tindall, George Brown and Shi, David E. ''America: A Narrative History (Brief 9th ed. 2012) vol 2 p. 590]

Rise of labor unions

Craft-oriented

Craft-oriented labor unions, such as carpenters, printers, shoemakers and cigar makers, grew steadily in the industrial cities after 1870. These unions used frequent short strikes as a method to attain control over the labor market, and fight off competing unions. They generally blocked women, blacks and Chinese from union membership, but welcomed most European immigrants.

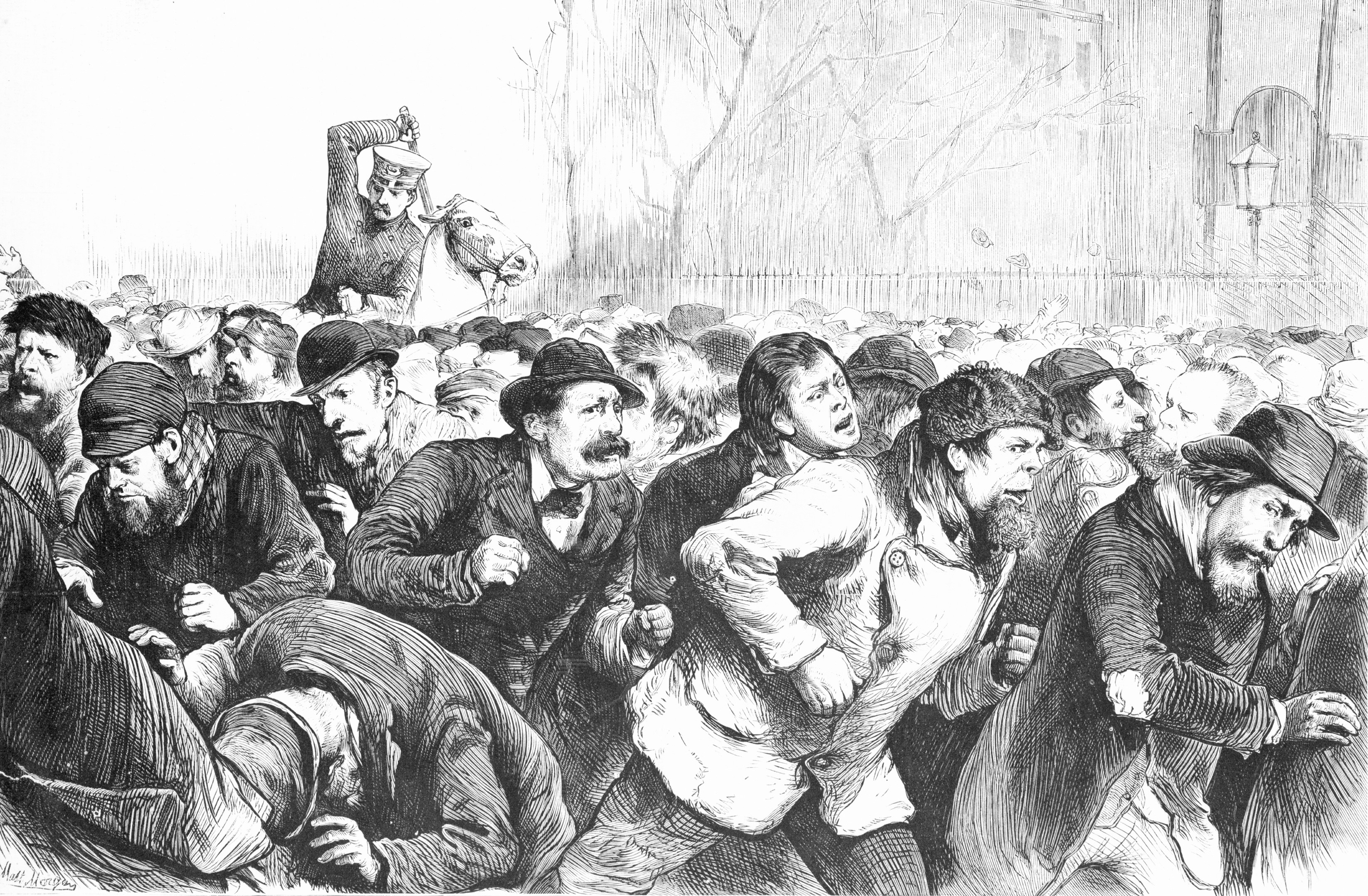

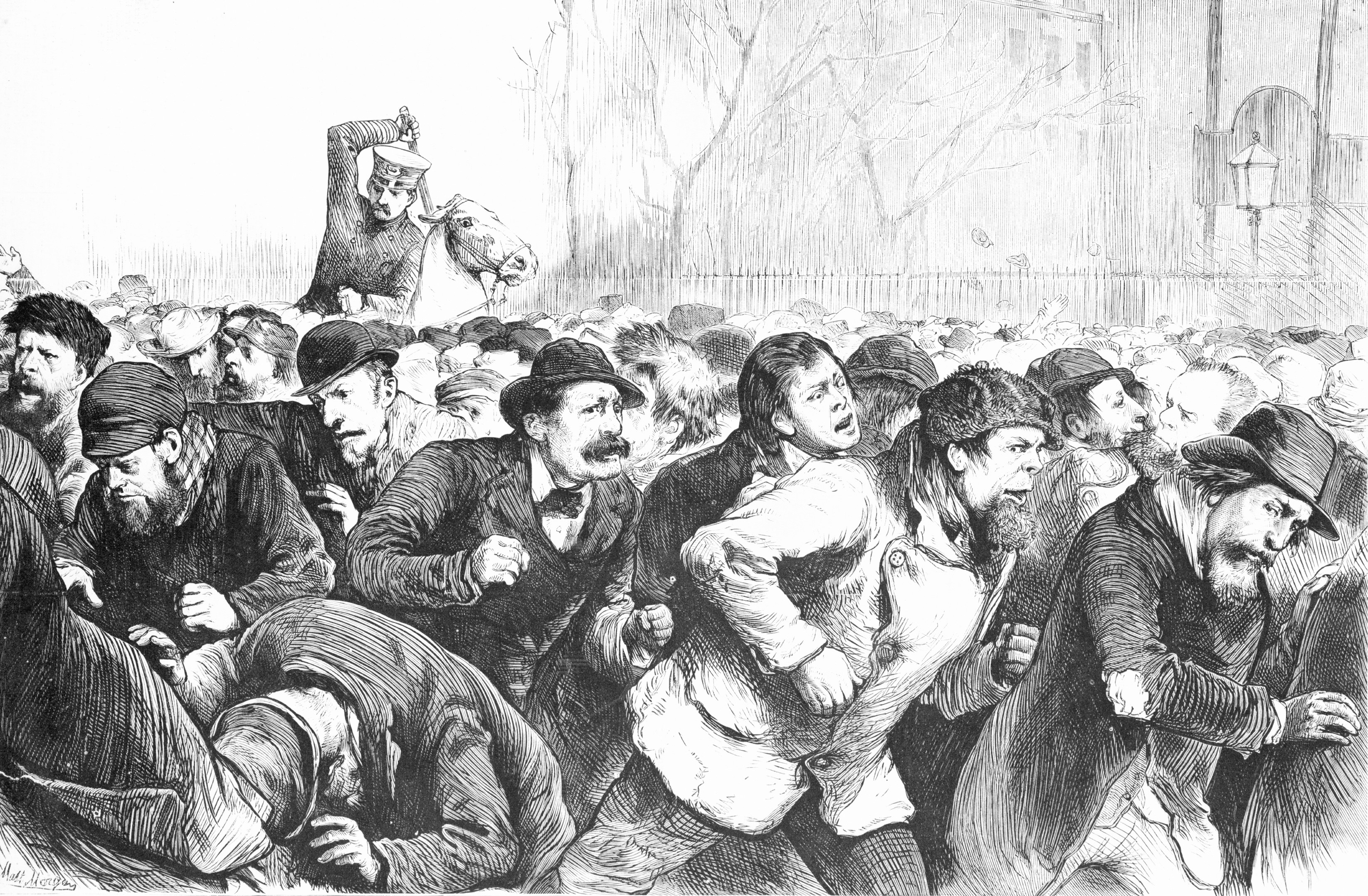

The railroads had their own separate unions. An especially large episode of unrest (estimated at eighty thousand railroad workers and several hundred thousand other Americans, both employed and unemployed) broke out during the

economic depression of the 1870s and became known as the

Great Railroad Strike of 1877

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877, sometimes referred to as the Great Upheaval, began on July 14 in Martinsburg, West Virginia, after the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) cut wages for the third time in a year. This strike finally ended 52 day ...

, which was, according to historian

Jack Beatty, "the largest strike anywhere in the world in the 19th century." This strike did not involve labor unions, but rather uncoordinated outbursts in numerous cities. The strike and associated riots lasted 45 days and resulted in the deaths of several hundred participants (no police or soldiers were killed), several hundred more injuries, and millions in damages to railroad property. The unrest was deemed severe enough by the government that President

Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governo ...

intervened with federal troops.

Starting in the mid-1880s a new group, the

Knights of Labor

Knights of Labor (K of L), officially Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was an American labor federation active in the late 19th century, especially the 1880s. It operated in the United States as well in Canada, and had chapters also ...

, grew too rapidly, and it spun out of control and failed to handle the

Great Southwest Railroad Strike of 1886. The Knights avoided violence, but their reputation collapsed in the wake of the

Haymarket Square Riot in Chicago in 1886, when anarchists allegedly bombed the policemen dispersing a meeting. Police then randomly fired into the crowd, killing and wounding a number of people, including other police, and arbitrarily rounded up anarchists, including leaders of the movement. Seven anarchists went on trial; four were hanged even though no evidence directly linked them to the bombing.

One had in his possession a Knights of Labor membership card.

At its peak, the Knights claimed 700,000 members. By 1890, membership had plummeted to fewer than 100,000, then faded away.

Strikes organized by labor unions became routine events by the 1880s as the gap between the rich and the poor widened. There were 37,000 strikes between 1881 and 1905. By far the largest number were in the building trades, followed far behind by coal miners. The main goal was control of working conditions and settling which rival union was in control. Most were of very short duration. In times of depression strikes were more violent but less successful, because the company was losing money anyway. They were successful in times of prosperity when the company was losing profits and wanted to settle quickly.

The largest and most dramatic strike was the 1894

Pullman Strike

The Pullman Strike was two interrelated strikes in 1894 that shaped national labor policy in the United States during a period of deep economic depression. First came a strike by the American Railway Union (ARU) against the Pullman factory in Chi ...

, a coordinated effort to shut down the national railroad system. The strike was led by the upstart

American Railway Union led by

Eugene V. Debs and was not supported by the established brotherhoods. The union defied federal court orders to stop blocking the mail trains, so President Cleveland used the U.S. Army to get the trains moving again. The ARU vanished and the traditional railroad brotherhoods survived, but avoided strikes.

The new

American Federation of Labor, headed by

Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers (; January 27, 1850December 13, 1924) was a British-born American cigar maker, labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and served as the organization's ...

, found the solution. The AFL was a coalition of unions, each based on strong local chapters; the AFL coordinated their work in cities and prevented jurisdictional battles. Gompers repudiated socialism and abandoned the violent nature of the earlier unions. The AFL worked to control the local labor market, thereby empowering its locals to obtain higher wages and more control over hiring. As a result, the AFL unions spread to most cities, reaching a peak membership in 1919.

This period saw several

financial crises

A financial crisis is any of a broad variety of situations in which some financial assets suddenly lose a large part of their nominal value. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, many financial crises were associated with banking panics, and man ...

and economic recessions—called "panics", notably the

Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

and the

Panic of 1893. They lasted several years, with high urban unemployment, low incomes for farmers, low profits for business, slow overall growth, and reduced immigration. They generated political unrest.

Politics

Gilded Age politics, called the

Third Party System

In the terminology of historians and political scientists, the Third Party System was a period in the history of political parties in the United States from the 1850s until the 1890s, which featured profound developments in issues of American n ...

, featured intense competition between two major parties, with minor parties coming and going, especially on issues of concern to prohibitionists, to labor unions and to farmers. The

Democrats and

Republicans (the latter nicknamed the "Grand Old Party", GOP) fought over control of offices, which were the rewards for party activists, as well as over major economic issues. Very high voter turnout typically exceeded 80% or even 90% in some Northern states as the parties drilled their loyal members much as an army drills its soldiers. Turnout in the South was lower. Average presidential turnout 1872 to 1900 was 83% in the North and 62% in the South.

Competition was intense and elections were very close. In the southern states, lingering resentment over the Civil War remained and meant that much of the South would vote Democrat. After the end of Reconstruction in 1877, competition in the South took place mainly inside the Democratic Party. Nationwide, turnout fell sharply after 1900.

Metropolitan area politics

The major metropolitan centers underwent rapid population growth and as a result had many lucrative contracts and jobs to award. To take advantage of the new economic opportunity, both parties built so-called "

political machines" to manage elections, to reward supporters and to pay off potential opponents. Financed by the "

spoils system

In politics and government, a spoils system (also known as a patronage system) is a practice in which a political party, after winning an election, gives government jobs to its supporters, friends (cronyism), and relatives (nepotism) as a reward ...

", the winning party distributed most local, state and national government jobs, and many government contracts, to its loyal supporters.

Large cities became dominated by political machines in which constituents supported a candidate in exchange for anticipated

patronage. These votes would be repaid with favors back from the government once the appropriate candidate was elected; and very often candidates were selected based on their willingness to play along with the spoils system. The largest and most notorious political machine was

Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York City political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society. It became the main loc ...

in New York City, led by

Boss Tweed.

Scandals and corruption

Political corruption was rampant, as business leaders spent significant amounts of money ensuring that government did not regulate the activities of

big business

Big business involves large-scale corporate-controlled financial or business activities. As a term, it describes activities that run from "huge transactions" to the more general "doing big things". In corporate jargon, the concept is commonly ...

—and they more often than not got what they wanted. Such corruption was so commonplace that in 1868 the New York state legislature legalized such bribery. Historian Howard Zinn argues that the U.S. government was acting exactly as

Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

described capitalist states: "pretending neutrality to maintain order, but serving the interests of the rich". Historian Mark Wahlgren Summers calls it, "The Era of Good Stealings," noting how machine politicians used "padded expenses, lucrative contracts, outright embezzlements, and illegal bond issues." He concludes:

:Corruption gave the age a distinctive flavor. It marred the planning and development of the cities, infected lobbyists dealings, and disgraced even the cleanest of the Reconstructed states. For many reasons, however, its effect on ''policy'' was less overwhelming than once imagined. Corruption influenced a few substantive decisions; it rarely determined one.

Numerous swindlers were active, especially before the

Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

exposed the falsifications and caused a wave of bankruptcies.

Former President

Ulysses S. Grant was the most famous victim of scoundrels and con-men, of whom he most trusted

Ferdinand Ward. Grant was cheated out of all his money, although some genuine friends bought Grant's personal assets and allowed him to keep their use.

Interpreting the phenomena, historian

Allan Nevins

Joseph Allan Nevins (May 20, 1890 – March 5, 1971) was an American historian and journalist, known for his extensive work on the history of the Civil War and his biographies of such figures as Grover Cleveland, Hamilton Fish, Henry Ford, and J ...

deplored "The Moral Collapse in Government and Business: 1865–1873." He argued that at war's end society showed confusion and unsettlement as well as a hurried aggressive growth on the other. They:

:united to give birth to an alarming public and private corruption. Obviously much of the shocking improbity was due to the heavy war-time expenditures.... Speculators and jobbers waxed fat on government money, the collection of federal revenues offered large opportunities for graft.... Under the stimulus of greenback inflation, business ran into excesses and lost sight of elementary canons of prudence. Meanwhile, it became clear that thievery had found a better opportunity to grow because the conscience of the nation aroused against slavery, had neglected what seemed minor evils..... The thousands who had rushed into speculations which they had no moral right to risk, the pushing, hardened men brought to the front by the turmoil, observed a courser, lower standard of conduct.... Much of the trouble lay in the immense growth of national wealth unaccompanied by any corresponding growth in civic responsibility.

National politics

Major scandals reached into Congress with the

Crédit Mobilier scandal

The Crédit Mobilier scandal () was a two-part fraud conducted from 1864 to 1867 by the Union Pacific Railroad and the Crédit Mobilier of America construction company in the building of the eastern portion of the First transcontinental railroad. ...

of 1872, and

disgraced the White House during the

Grant

Grant or Grants may refer to:

Places

*Grant County (disambiguation)

Australia

* Grant, Queensland, a locality in the Barcaldine Region, Queensland, Australia

United Kingdom

* Castle Grant

United States

* Grant, Alabama

* Grant, Inyo County, ...

Administration (1869–1877). This corruption divided the Republican party into two different factions: the

Stalwarts led by

Roscoe Conkling

Roscoe Conkling (October 30, 1829April 18, 1888) was an American lawyer and Republican politician who represented New York in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate. He is remembered today as the leader of the ...

and the

Half-Breeds led by

James G. Blaine. There was a sense that government-enabled political machines intervened in the economy and that the resulting favoritism, bribery, inefficiency, waste, and corruption were having negative consequences. Accordingly, there were widespread calls for reform, such as

Civil Service Reform led by the

Bourbon Democrats

Bourbon Democrat was a term used in the United States in the later 19th century (1872–1904) to refer to members of the Democratic Party who were ideologically aligned with fiscal conservatism or classical liberalism, especially those who supp ...

and Republican

Mugwump

The Mugwumps were Republican political activists in the United States who were intensely opposed to political corruption. They were never formally organized. Typically they switched parties from the Republican Party by supporting Democratic ...

s. In 1884, their support elected Democrat

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

to the White House, and in doing so gave the Democrats their first national victory since 1856.

The Bourbon Democrats supported a

free market

In economics, a free market is an economic system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of government or any ot ...

policy, with low tariffs, low taxes, less spending and, in general, a ''

laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups ...

'' (hands-off) government. They argued that tariffs made most goods more expensive for the consumer and subsidized "the trusts" (monopolies). They also denounced

imperialism and overseas expansion. By contrast, Republicans insisted that national prosperity depended on industry that paid high wages, and warned that lowering the tariff would bring disaster because goods from low-wage European factories would flood American markets.

Presidential elections between the two major parties were so closely contested that a slight nudge could tip the election in the advantage of either party, and Congress was marked by political stalemate. With support from

Union veterans, businessmen, professionals, craftsmen, and larger farmers, the Republicans consistently carried the North in presidential elections. The Democrats, often led by

Irish Catholics, had a base among Catholics, poorer farmers, and traditional party-members.

The nation elected a string of relatively weak presidents collectively referred to as the "forgettable presidents" (

Johnson,

Grant

Grant or Grants may refer to:

Places

*Grant County (disambiguation)

Australia

* Grant, Queensland, a locality in the Barcaldine Region, Queensland, Australia

United Kingdom

* Castle Grant

United States

* Grant, Alabama

* Grant, Inyo County, ...

,

Hayes,

Garfield

''Garfield'' is an American comic strip created by Jim Davis. Originally published locally as ''Jon'' in 1976, then in nationwide syndication from 1978 as ''Garfield'', it chronicles the life of the title character Garfield the cat, his hum ...

,

Arthur

Arthur is a common male given name of Brythonic origin. Its popularity derives from it being the name of the legendary hero King Arthur. The etymology is disputed. It may derive from the Celtic ''Artos'' meaning “Bear”. Another theory, more wi ...

, and

Harrison

Harrison may refer to:

People

* Harrison (name)

* Harrison family of Virginia, United States

Places

In Australia:

* Harrison, Australian Capital Territory, suburb in the Canberra district of Gungahlin

In Canada:

* Inukjuak, Quebec, or " ...

, with the exception of

Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

) who served in the White House during this period.

"What little political vitality existed in Gilded Age America was to be found in local settings or in Congress, which overshadowed the White House for most of this period."

[

Overall, Republican and Democratic political platforms remained remarkably constant during the years before 1900. Both favored business interests. Republicans called for high tariffs, while Democrats wanted hard money and ]free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

. Regulation was rarely an issue.

Ethnocultural politics: pietistic Republicans versus liturgical Democrats

From 1860 to the early 20th century, the Republicans took advantage of the association of the Democrats with "Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion". "Rum" stood for the liquor interests and the tavern keepers, in contrast to the GOP, which had a strong dry element. "Romanism" meant Roman Catholics, especially Irish Americans, who ran the Democratic Party in most cities, and whom the reformers denounced for political corruption and their separate parochial school system. "Rebellion" harked back to the Democrats of the Confederacy, who had tried to break the Union in 1861, as well as to their northern allies, called " Copperheads".

Demographic trends boosted the Democratic totals, as the German and Irish Catholic immigrants became Democrats and outnumbered the English and Scandinavian Republicans. The new immigrants who arrived after 1890 seldom voted at this time. During the 1880s and 1890s, the Republicans struggled against the Democrats' efforts, winning several close elections and losing two to Grover Cleveland (in 1884 and 1892).

Religious lines were sharply drawn.

Immigration

Prior to the Gilded Age, the time commonly referred to as the old immigration saw the first real boom of new arrivals to the United States. During the Gilded Age, approximately 20 million immigrants came to the United States in what is known as the new immigration. Some of them were prosperous farmers who had the cash to buy land and tools in the Plains states especially. Many were poor peasants looking for the American Dream in unskilled manual labor in mills, mines, and factories. Few immigrants went to the poverty-stricken South, though. To accommodate the heavy influx, the federal government in 1892 opened a reception center at

Prior to the Gilded Age, the time commonly referred to as the old immigration saw the first real boom of new arrivals to the United States. During the Gilded Age, approximately 20 million immigrants came to the United States in what is known as the new immigration. Some of them were prosperous farmers who had the cash to buy land and tools in the Plains states especially. Many were poor peasants looking for the American Dream in unskilled manual labor in mills, mines, and factories. Few immigrants went to the poverty-stricken South, though. To accommodate the heavy influx, the federal government in 1892 opened a reception center at Ellis Island

Ellis Island is a federally owned island in New York Harbor, situated within the U.S. states of New York and New Jersey, that was the busiest immigrant inspection and processing station in the United States. From 1892 to 1954, nearly 12 mil ...

near the Statue of Liberty; new arrivals needed to pass a medical inspection.

Waves of old and new immigrants

These immigrants consisted of two groups: The last big waves of the "Old Immigration" from Germany, Britain, Ireland, and Scandinavia, and the rising waves of the "New Immigration", which peaked about 1910. Some men moved back and forth across the Atlantic, but most were permanent settlers. They moved into well-established communities, both urban and rural. The German American communities spoke German, but their younger generation was bilingual. The Scandinavian groups generally assimilated quickly; they were noted for their support of reform programs, such as prohibition.

In terms of immigration after 1880, the old immigration of Germans, British, Irish, and Scandinavians slackened off. The United States was producing large numbers of new unskilled jobs every year, and to fill them came number from Italy, Poland, Austria, Hungary, Russia, Greece, and other points in southern and central Europe, as well as French Canada. The older immigrants by the 1870s had formed highly stable communities, especially the German Americans. The British immigrants tended to blend into the general population.

Irish Catholics had arrived in large numbers in the 1840s and 1850s in the wake of the great famine in Ireland when starvation killed millions. Their first few decades were characterized by extreme poverty, social dislocation, crime, and violence in their slums. By the late 19th century, the Irish communities had largely stabilized, with a strong new "lace curtain" middle class of local businessmen, professionals, and political leaders typified by P. J. Kennedy (1858–1929) in Boston. In economic terms, Irish Catholics were nearly at the bottom in the 1850s. They reached the national average by 1900, and by the late 20th century they far surpassed the national average.

In political terms, the Irish Catholics comprised a major element in the leadership of the urban Democratic machines across the country. Although they were only a third of the total Catholic population, the Irish also dominated the Catholic Church, producing most of the bishops, college presidents, and leaders of charitable organizations. The network of Catholic institutions provided high status, but low-paying lifetime careers to sisters and nuns in parochial schools, hospitals, orphanages and convents. They were part of an international Catholic network, with considerable movement back and forth from Ireland, England, France, Germany, and Canada.

In terms of immigration after 1880, the old immigration of Germans, British, Irish, and Scandinavians slackened off. The United States was producing large numbers of new unskilled jobs every year, and to fill them came number from Italy, Poland, Austria, Hungary, Russia, Greece, and other points in southern and central Europe, as well as French Canada. The older immigrants by the 1870s had formed highly stable communities, especially the German Americans. The British immigrants tended to blend into the general population.

Irish Catholics had arrived in large numbers in the 1840s and 1850s in the wake of the great famine in Ireland when starvation killed millions. Their first few decades were characterized by extreme poverty, social dislocation, crime, and violence in their slums. By the late 19th century, the Irish communities had largely stabilized, with a strong new "lace curtain" middle class of local businessmen, professionals, and political leaders typified by P. J. Kennedy (1858–1929) in Boston. In economic terms, Irish Catholics were nearly at the bottom in the 1850s. They reached the national average by 1900, and by the late 20th century they far surpassed the national average.

In political terms, the Irish Catholics comprised a major element in the leadership of the urban Democratic machines across the country. Although they were only a third of the total Catholic population, the Irish also dominated the Catholic Church, producing most of the bishops, college presidents, and leaders of charitable organizations. The network of Catholic institutions provided high status, but low-paying lifetime careers to sisters and nuns in parochial schools, hospitals, orphanages and convents. They were part of an international Catholic network, with considerable movement back and forth from Ireland, England, France, Germany, and Canada.

New immigrants

The "New Immigration" were much poorer peasants and rural folk from southern and eastern Europe, including mostly Italians, Poles, and Jews. Some men, especially the Italians and Greeks, saw themselves as temporary migrants who planned to return to their home villages with a nest egg of cash earned in long hours of unskilled labor. Others, especially the Jews, had been driven out of Eastern Europe and had no intention of returning.

Historians analyze the causes of immigration in terms of push factors (pushing people out of the homeland) and pull factors (pulling them to America). The push factors included economic dislocation, shortages of land, and antisemitism. Pull factors were the economic opportunity of good inexpensive farmland or jobs in factories, mills and mines.

The first generation typically lived in ethnic enclaves with a common language, food, religion, and connections through the old village. The sheer numbers caused overcrowding in tenements in the larger cities. In the small mill towns, however, management usually built company housing with cheap rents.

The "New Immigration" were much poorer peasants and rural folk from southern and eastern Europe, including mostly Italians, Poles, and Jews. Some men, especially the Italians and Greeks, saw themselves as temporary migrants who planned to return to their home villages with a nest egg of cash earned in long hours of unskilled labor. Others, especially the Jews, had been driven out of Eastern Europe and had no intention of returning.

Historians analyze the causes of immigration in terms of push factors (pushing people out of the homeland) and pull factors (pulling them to America). The push factors included economic dislocation, shortages of land, and antisemitism. Pull factors were the economic opportunity of good inexpensive farmland or jobs in factories, mills and mines.

The first generation typically lived in ethnic enclaves with a common language, food, religion, and connections through the old village. The sheer numbers caused overcrowding in tenements in the larger cities. In the small mill towns, however, management usually built company housing with cheap rents.

Chinese immigrants

Chinese immigrants were hired by California construction companies for temporary railroad work. European Americans strongly disliked the Chinese for their alien lifestyles and the threat of low wages. The construction of the Central Pacific Railroad from California to Utah was handled largely by Chinese laborers. In the 1870 census, there were 63,000 Chinese men, with a few women in the entire U.S.; this number grew to 106,000 in 1880. Labor unions, led by Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers (; January 27, 1850December 13, 1924) was a British-born American cigar maker, labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and served as the organization's ...

strongly opposed the presence of Chinese labor. Immigrants from China were not allowed to become citizens until 1950; however, as a result of the Supreme Court decision in '' United States v. Wong Kim Ark'', their children born in the U.S. were full citizens.

Congress further banned Chinese immigration through the Chinese Exclusion Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The law excluded merchants, teachers, students, travelers, and diplo ...

in 1882; the act prohibited Chinese laborers from entering the United States, but some students and businessmen were allowed in on a temporary basis. The Chinese population declined to only 37,000 in 1940. Although many returned to China (a greater proportion than most other immigrant groups), most of them stayed in the United States. Chinese people were unwelcome in urban neighborhoods, so they resettled in the " Chinatown" districts of large cities. The exclusion policy lasted until the 1940s.

Rural life

A dramatic expansion in farming took place during the Gilded Age,[''Historical Statistics'' (1975) p. 437 series K1-K16]

The federal government issued tracts virtually free to settlers under the Homestead Act

The Homestead Acts were several laws in the United States by which an applicant could acquire ownership of government land or the public domain, typically called a homestead. In all, more than of public land, or nearly 10 percent of t ...

of 1862. Even larger numbers purchased lands at very low interest from the new railroads, which were trying to create markets. The railroads advertised heavily in Europe and brought over, at low fares, hundreds of thousands of farmers from Germany, Scandinavia and Britain.[William Clark, ''Farms and farmers: the story of American agriculture'' (1970) p. 205]

Despite their remarkable progress and general prosperity, 19th century U.S. farmers experienced recurring cycles of hardship, caused primarily by falling world prices for cotton and wheat.Populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term develop ...

movement of the 1890s. Wheat farmers blamed local grain elevator owners (who purchased their crop), railroads and eastern bankers for the low prices.[Elwyn B. Robinson, ''History of North Dakota'' (1982) p. 203] This protest has now been attributed to the far increased uncertainty in farming due to its commercialisation, with monopolies, the gold standard and loans being simply visualisations of this risk.

The first organized effort to address general agricultural problems was the Grange movement. Launched in 1867, by employees of the U.S. Department of Agriculture

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is the federal executive department responsible for developing and executing federal laws related to farming, forestry, rural economic development, and food. It aims to meet the needs of comme ...

, the Granges focused initially on social activities to counter the isolation most farm families experienced. Women's participation was actively encouraged. Spurred by the Panic of 1873, the Grange soon grew to 20,000 chapters and 1.5 million members. The Granges set up their own marketing systems, stores, processing plants, factories and cooperative

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically-contro ...

s. Most went bankrupt. The movement also enjoyed some political success during the 1870s. A few Midwestern states passed " Granger Laws", limiting railroad and warehouse fees.[D. Sven Nordin, ''Rich Harvest: A History of the Grange, 1867–1900'' (1974)] The agricultural problems gained mass political attention in the Populist movement, which won 44 votes in the Electoral College in 1892

Events

January–March

* January 1 – Ellis Island begins accommodating immigrants to the United States.

* February 1 - The historic Enterprise Bar and Grill was established in Rico, Colorado.

* February 27 – Rudolf Diesel applies fo ...

. Its high point came in 1896 with the candidacy of William Jennings Bryan for the Democrats, who was sympathetic to populist concerns such as the silver standard.

Urban life

American society experienced significant changes in the period following the Civil War, most notably the rapid urbanization of the North. Due to the increasing demand for unskilled workers, most European immigrants went to mill towns, mining camps, and industrial cities. New York, Philadelphia, and especially Chicago saw rapid growth.

American society experienced significant changes in the period following the Civil War, most notably the rapid urbanization of the North. Due to the increasing demand for unskilled workers, most European immigrants went to mill towns, mining camps, and industrial cities. New York, Philadelphia, and especially Chicago saw rapid growth. Louis Sullivan

Louis Henry Sullivan (September 3, 1856 – April 14, 1924) was an American architect, and has been called a "father of skyscrapers" and "father of modernism". He was an influential architect of the Chicago School, a mentor to Frank Lloy ...

became a noted architect using steel frames to construct skyscrapers for the first time while pioneering the idea of "form follows function

Form follows function is a principle of design associated with late 19th and early 20th century architecture and industrial design in general, which states that the shape of a building or object should primarily relate to its intended function ...

". Chicago became the center of the skyscraper craze, starting with the ten-story Home Insurance Building

The Home Insurance Building was a skyscraper that stood in Chicago from 1885 to 1931. Originally ten stories and tall, it was designed by William Le Baron Jenney in 1884 and completed the next year. Two floors were added in 1891, bringing its ...

in 1884–1885 by William Le Baron Jenney

William Le Baron Jenney (September 25, 1832 – June 14, 1907) was an American architect and engineer who is known for building the first skyscraper in 1884.

In 1998, Jenney was ranked number 89 in the book ''1,000 Years, 1,000 People: Ran ...

.

As immigration increased in cities, poverty rose as well. The poorest crowded into low-cost housing such as the Five Points and Hell's Kitchen

Hell's Kitchen, also known as Clinton, is a neighborhood on the West Side of Midtown Manhattan in New York City. It is considered to be bordered by 34th Street (or 41st Street) to the south, 59th Street to the north, Eighth Avenue to the ea ...

neighborhoods in Manhattan. These areas were quickly overridden with notorious criminal gangs such as the Five Points Gang

The Five Points Gang was a criminal street gang of primarily Irish-American origins, based in the Five Points of Lower Manhattan, New York City, during the late 19th and early 20th century.

Paul Kelly, born Paolo Antonio Vaccarelli, was an It ...