Gheorghe Tătărescu on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

: ''For the artist, see

After the

After the

Gheorghe Tattarescu

Gheorghe Tattarescu (; October 1818 – October 24, 1894) was a Moldavian, later Romanian Painting, painter and a pioneer of neoclassicism in his country's modern painting.

Biography

Early life and studies

Tattarescu was born in Focşani i ...

.''

Gheorghe I. Tătărescu (also known as ''Guță Tătărescu'', with a slightly antiquated pet form of his given name; 2 November 1886 – 28 March 1957) was a Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

n politician who served twice as Prime Minister of Romania

The prime minister of Romania ( ro, Prim-ministrul României), officially the prime minister of the Government of Romania ( ro, Prim-ministrul Guvernului României, link=no), is the head of the Government of Romania. Initially, the office was ...

(1934–1937; 1939–1940), three times as Minister of Foreign Affairs

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between co ...

(''interim'' in 1934 and 1938, appointed to the office in 1945-1947) and once as Minister of War

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in som ...

(1934). Representing the "young liberals" faction inside the National Liberal Party (PNL), Tătărescu began his political career as a collaborator of Ion G. Duca, becoming noted for his anticommunism

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and the ...

and, in time, for his conflicts with the PNL's leader Dinu Brătianu

Dinu Brătianu (January 13, 1866 – May 20, 1950), born Constantin I. C. Brătianu, was a Romanian engineer and politician who led the National Liberal Party (PNL) starting in 1934.

Life Early career

Born at the estate of ''Florica'', in ...

and the Foreign Minister Nicolae Titulescu. During his first time in office, he moved closer to King Carol II

Carol II (4 April 1953) was King of Romania from 8 June 1930 until his forced abdication on 6 September 1940. The eldest son of Ferdinand I, he became crown prince upon the death of his grand-uncle, King Carol I in 1914. He was the first of th ...

and led an ambivalent policy toward the fascist Iron Guard and ultimately becoming instrumental in establishing the authoritarian and corporatist

Corporatism is a Collectivism and individualism, collectivist political ideology which advocates the organization of society by Corporate group (sociology), corporate groups, such as agricultural, labour, military, business, scientific, or guil ...

regime around the National Renaissance Front

The National Renaissance Front ( ro, Frontul Renașterii Naționale, FRN; also translated as ''Front of National Regeneration'', ''Front of National Rebirth'', ''Front of National Resurrection'', or ''Front of National Renaissance'') was a Romani ...

. In 1940, he accepted the cession of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

and had to resign.

After the start of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, Gheorghe Tătărescu initiated a move to rally political forces in opposition to Ion Antonescu's dictatorship, and sought an alliance with the Romanian Communist Party (PCR). He was twice expelled from the PNL, in 1938 and 1944, creating instead his own group, the National Liberal Party-Tătărescu

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, c ...

, and representing it inside the communist-endorsed Petru Groza

Petru Groza (7 December 1884 – 7 January 1958) was an Austro-Hungarian-born Romanian politician, best known as the first Prime Minister of the Communist Party-dominated government under Soviet occupation during the early stages of the Commu ...

cabinet. In 1946-1947, he was also the President of the Romanian Delegation to the Peace Conference in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

. Then, relations between Tătărescu and the PCR began to sour, and he was replaced from the leadership of both his own party and the Foreign Ministry when his name was implicated in the Tămădău Affair. Following the Communist takeover, he was arrested and held as a political prisoner

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although n ...

while being called to testify in the trial of Lucrețiu Pătrășcanu

Lucrețiu Pătrășcanu (; November 4, 1900 – April 17, 1954) was a Romanian communist politician and leading member of the Communist Party of Romania (PCR), also noted for his activities as a lawyer, sociologist and economist. For a while, he ...

. He died soon after his release from prison.

Elected an honorary member of the Romanian Academy in 1937, he was removed from his seat by the communist authorities in 1948.Gogan One of his brothers, Colonel Ștefan Tătărescu, was at some point the leader of a minor Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

group, the National Socialist Party.

Early life and politics

Born inTârgu Jiu

Târgu Jiu () is the capital of Gorj County in the Oltenia region of Romania. It is situated on the Southern Sub-Carpathians, on the banks of the river Jiu. Eight localities are administered by the city: Bârsești, Drăgoieni, Iezureni, Polat ...

, Tătărescu studied at Carol I High School in Craiova. He later went to France, where he was awarded a doctorate

A doctorate (from Latin ''docere'', "to teach"), doctor's degree (from Latin ''doctor'', "teacher"), or doctoral degree is an academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism ''li ...

from the University of Paris

, image_name = Coat of arms of the University of Paris.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of Arms

, latin_name = Universitas magistrorum et scholarium Parisiensis

, motto = ''Hic et ubique terrarum'' (Latin)

, mottoeng = Here and a ...

in 1912, with a thesis on the Romanian parliamentary system

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of th ...

(''Le régime électoral et parlementaire en Roumanie''). He subsequently worked as a lawyer in Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north of ...

. He fathered a son, Tudor, and a daughter, Sanda (married to the lawyer Ulise Negropontes in 1940).Petru

After joining the National Liberal Party (PNL), he was elected to the Chamber of Deputies for the first time in November 1919, representing Gorj County. Among his first notable actions as a politician was an initiative to interpellate Nicolae L. Lupu, the Minister of Interior Affairs Ministry in the Romanian National Party

The Romanian National Party ( ro, Partidul Național Român, PNR), initially known as the Romanian National Party in Transylvania and Banat (), was a political party which was initially designed to offer ethnic representation to Romanians in the ...

- Peasants' Party cabinet in answer to concerns that the executive was tolerating socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

agitation in the countryside.

He stood among the PNL's "young liberals" faction, as they were colloquially known, supporting free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

and a more authoritarian rule over the country around King Carol II

Carol II (4 April 1953) was King of Romania from 8 June 1930 until his forced abdication on 6 September 1940. The eldest son of Ferdinand I, he became crown prince upon the death of his grand-uncle, King Carol I in 1914. He was the first of th ...

, and opposing both the older generation of leaders (who tended to advocate protectionism

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulatio ...

and a liberal democracy

Liberal democracy is the combination of a liberal political ideology that operates under an indirect democratic form of government. It is characterized by elections between multiple distinct political parties, a separation of powers into ...

) and the dissident group of Gheorghe I. Brătianu

Gheorghe (George) I. Brătianu (January 28 1898 – April 23–27, 1953) was a Romanian politician and historian. A member of the Brătianu family and initially affiliated with the National Liberal Party (Romania, 1875), National Liberal Par ...

(''see National Liberal Party-Brătianu'').

The Undersecretary in the Interior Affairs Ministry under several PNL cabinets (beginning with that of Ion I. C. Brătianu in 1922–1926), he first became noted as a collaborator of Ion G. Duca. In 1924–1936, in contrast to his agenda after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

agenda, Tătărescu was a noted anticommunist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and the ...

, and reacted vehemently against the Romanian Communist Party (PCdR, later PCR), recommending and obtaining its outlawing, based on communist adversity to the concept of Greater Romania

The term Greater Romania ( ro, România Mare) usually refers to the borders of the Kingdom of Romania in the interwar period, achieved after the Great Union. It also refers to a pan-nationalist idea.

As a concept, its main goal is the creation ...

, and notably arguing that the Comintern-supported Tatarbunary Uprising

The Tatarbunary Uprising ( ro, Răscoala de la Tatarbunar) was a Bolshevik-inspired and Soviet-backed peasant revolt that took place on 15–18 September 1924, in and around the town of Tatarbunary (''Tatar-Bunar'' or ''Tatarbunar'') in Budjak ...

was evidence of "imperialist

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

".

First cabinet

Context

Tătărescu became leader of the cabinet in January 1934, as the fascist Iron Guard had assassinated Prime Minister Duca on 30 December 1933 (the five-day premiership of Constantin Anghelescu ensured transition between the two governments). His was the second PNL cabinet formed during Carol's reign, and the latter's failure to draw support from the mainstream group led to a tight connection being established between Carol and the young liberals, with Tătărescu backing the process leading to the creation of a royaldictatorship

A dictatorship is a form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, which holds governmental powers with few to no limitations on them. The leader of a dictatorship is called a dictator. Politics in a dictatorship a ...

. One of Tătărescu's first measures was a decisive move to end the conflict between the National Liberal executive and the Mayor of Bucharest

The Mayor of Bucharest ( ro, Primarul General al Municipiului București), sometimes known as the General Mayor, is the head of the Bucharest City Hall in Bucharest, Romania, which is responsible for citywide affairs, such as the water system, the ...

, Dem I. Dobrescu (who was backed by the National Peasants' Party

The National Peasants' Party (also known as the National Peasant Party or National Farmers' Party; ro, Partidul Național Țărănesc, or ''Partidul Național-Țărănist'', PNȚ) was an agrarian political party in the Kingdom of Romania. It w ...

)—making use of his prerogative, he removed Dobrescu from office on 18 January.

The brief period constituted a reference point in Romanian economy, as the emergence from the Great Depression, although marked by endemic problems, saw prosperity more widespread than ever before. This was, in part, the contribution of new economic relations which Tătărescu defended and encouraged: the state transformed itself into the main agent of economic activities, allowing for prosperous businesses to benefit from its demands, and, in time, leading to the creation of a '' camarilla'' dominated by the figures of industrialists such as Aristide Blank, Nicolae Malaxa

Nicolae Malaxa ( – 1965) was a Romanian engineer and industrialist.

Biography

Born in a family of Greek origin in Huşi, Malaxa studied engineering in Iaşi (at the University of Iaşi) and Karlsruhe (at the Polytechnic University). Lat ...

, and Max Auschnitt

Max Carol Auschnitt,Cerasela Moldoveanu, "În căutarea lui Schwartz... Contribuția evreilor la Războiul de Întregire Națională a României (1916–1919)", in ''Revista de Istorie Militară'', Issues 5–6/2017, p. 90 also known as Ausschnitt ...

. In this context, Tătărescu's allegedly subservient position in front of Carol was a frequent topic of ridicule at the time. According to a hostile account of the socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

Petre Pandrea Petre is a surname and given name derived from Peter. Notable persons with that name include:

People with the given name Petre

* Charles Petre Eyre (1817–1902), English Roman Catholic prelate

* Ion Petre Stoican (circa 1930–1990), Romanian v ...

:

"Tătărescu was ceremonious in order to cover his menial nature. When he was leaving audiences ith the King he pressed forward on the small of his back and returned ''facing backwards'' from the desk to the door, not daring to show his back. ..Watching over the scene .. Carol II exclaimed to his intimate assistants:Among other services rendered, he intervened in the conflict between Carol and his brother,

— I don't have a big enough tooshie for all the politicians to kiss!"

Prince Nicholas

Nicholas Teo () is a Malaysian Chinese singer under Good Tengz Entertainment Sdn Bhd. (Malaysia)

Career

Pre debut

Before returning to Malaysia, Nicholas was studying in Taiwan, where he won the Best Singer in a competition among all the Tai ...

, asking the latter to renounce either his marriage to Ioana Dumitrescu-Doletti—considered a misalliance by Carol, it had not been recognized by Romanian authorities—or his princely prerogatives.Scurtu, "Principele Nicolae..." Nicholas chose the latter alternative in 1937.

Inside his party, Tătărescu lost ground to Dinu Brătianu

Dinu Brătianu (January 13, 1866 – May 20, 1950), born Constantin I. C. Brătianu, was a Romanian engineer and politician who led the National Liberal Party (PNL) starting in 1934.

Life Early career

Born at the estate of ''Florica'', in ...

, elected by the traditional Liberal elite

Liberal elite, also referred to as the metropolitan elite or progressive elite, is a stereotype of politically liberal people whose education has traditionally opened the doors to affluence, wealth and power and who form a managerial elite. It is ...

as a compromise in order to ensure unity; upon his election in 1934, the latter stated:

"This time as well, I would have gladly conceded, if I were to believe that anyone else in the party could gather voter unanimity."The issue remained debated for the following two years. The party congress of July 1936 eventually elected Tătărescu to the second position in the party, that of general secretary.Scurtu, "Politica...", p.17

European politics

In his foreign policy, Prime Minister Tătărescu balanced two different priorities, attempting to strengthen the traditional military alliance withPoland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

which was aimed at the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, and reacting against the growing regional influence of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

by maintaining the relevancy of the Little Entente

The Little Entente was an alliance formed in 1920 and 1921 by Czechoslovakia, Romania and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (since 1929 Yugoslavia) with the purpose of common defense against Hungarian revanchism and the prospect of a Ha ...

and establishing further contacts with the Soviets.

In August 1936, he removed Nicolae Titulescu from the office of Foreign Minister, replacing him with Victor Antonescu

Victor Antonescu (September 3, 1871, Antonești, Teleorman County – August 22, 1947, Bucharest) was a Minister of Finance

A finance minister is an executive or cabinet position in charge of one or more of government finances, economic po ...

. This caused an uproar, with most of Romania's diplomatic corps

The diplomatic corps (french: corps diplomatique) is the collective body of foreign diplomats accredited to a particular country or body.

The diplomatic corps may, in certain contexts, refer to the collection of accredited heads of mission ( ...

voicing their dissatisfaction. Over the following months, virtually all of Titulescu's supporters were themselves recalled (including, among others, Constantin Vișoianu, the ambassador to Poland, Constantin Antoniade, Romania's representative to the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

, Dimitrie Ghyka, the ambassador to Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

, and Caius Brediceanu, the ambassador to Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

) while Titulescu's adversaries, such as Antoine Bibesco

Prince Antoine Bibesco ( ro, Prințul Anton Bibescu; July 19, 1878 – September 2, 1951) was a Romanian aristocrat, lawyer, diplomat, and writer.

Biography

His father was Prince Alexandre Bibesco, the last surviving son of the ''hospodar'' ...

, were returned to office. Bibesco subsequently campaigned in France and the United Kingdom, in an attempt to reassure Romania's main allies that the move did not signify a change in Romania's priorities. Tătărescu was later blamed by his own party for having renounced the diplomatic course on which Romania had engaged.Țurlea, p.29

In early 1937, Tătărescu rejected the proposal of Józef Beck

Józef Beck (; 4 October 1894 – 5 June 1944) was a Polish statesman who served the Second Republic of Poland as a diplomat and military officer. A close associate of Józef Piłsudski, Beck is most famous for being Polish foreign minister in ...

, Poland's Minister of Foreign Affairs, to withdraw Romania's support for Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

and attempt a reconciliation with Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the ...

(the following year, Romania withdrew its support for the former, indicating, just before the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

, that it was not in a position to guarantee Czechoslovakia's frontiers). This was accompanied by Czechoslovak initiatives to establish close contacts between the Little Entente and the Soviets: a scandal erupted in the same year, when the country's ambassador to Romania, Jan Šeba, published a volume calling for Soviet-Entente military cooperation (despite the Soviet-Romanian conflict over Bessarabia) and expressing the hope that the Soviet state would extend its borders into West Belarus

Western Belorussia or Western Belarus ( be, Заходняя Беларусь, translit=Zachodniaja Bielaruś; pl, Zachodnia Białoruś; russian: Западная Белоруссия, translit=Zapadnaya Belorussiya) is a historical region of mod ...

and Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

.Otu Kamil Krofta

Kamil Krofta (17 July 1876 – 16 August 1945) was a Czech historian and diplomat.Honajzer George (1995). ''Vznik a rozpad vládních koalic v Československu v letech 1918-1938.'' stablishment and dissolution of government coalitions in Czecho ...

, Czechoslovakia's Foreign Minister, received criticism for having prefaced the book, and, after Tătărescu paid a visit to Czechoslovak Prime Minister Milan Hodža

Milan Hodža (1 February 1878 – 27 June 1944) was a Slovak politician and journalist, serving from 1935 to 1938 as the prime minister of Czechoslovakia. As a proponent of regional integration, he was known for his attempts to establish a demo ...

, Šeba was recalled to Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and List of cities in the Czech Republic, largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 milli ...

.

Facing the Iron Guard

In combating the Iron Guard, Tătărescu chose to relax virtually all pressures on the latter (while mimicking some of its messages), and instead concentrated again on curbing the activities of the Romanian Communist Party (PCR) and outlawing its ''Popular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalition ...

''-type organizations (''see Amicii URSS'').

In April 1936, he and the Minister of the Interior

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergency ...

Ion Inculeț allowed the a youth congress to gather in Târgu Mureș

Târgu Mureș (, ; hu, Marosvásárhely ) is the seat of Mureș County in the historical region of Transylvania, Romania. It is the 16th largest Romanian city, with 134,290 inhabitants as of the 2011 census. It lies on the Mureș River, the ...

, aware of the fact that it was masking a fascist gathering; delegates to the congress, traveling in a special train commissioned by the government, vandalized Ion Duca's memorial plate in Sinaia train station, and, upon their arrival in Târgu Mureș, made public their violent anti-Semitic agenda. It was probably there that death squads were designated and assigned missions, leading to the murder of Mihai Stelescu, a former associate, in June of the next year.

In February 1937, an intense publicity campaign by the Guard, begun with the ostentatious funerals of Ion Moța

Ion I. Moța (5 July 1902 — 13 January 1937) was the deputy leader of the Romanian fascist Iron Guard, Legionary Movement (Iron Guard), killed in battle during the Spanish Civil War.

Biography

Son of the nationalist Romanian Orthodox, Ort ...

and Vasile Marin (killed in the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, link ...

) and culminating in the physical assaulting of Traian Bratu, rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

of the University of Iași

The Alexandru Ioan Cuza University ( Romanian: ''Universitatea „Alexandru Ioan Cuza"''; acronym: UAIC) is a public university located in Iași, Romania. Founded by an 1860 decree of Prince Alexandru Ioan Cuza, under whom the former Academia M ...

, by Guardist students, provoked the premier's order to close down universities throughout the country.

Later in that year, the collaboration between monarch and premier, coupled with the fact that Tătărescu had successfully attracted nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

votes from the Iron Guard, led to the signing of an electoral agreement between the latter, the National Peasants' Party

The National Peasants' Party (also known as the National Peasant Party or National Farmers' Party; ro, Partidul Național Țărănesc, or ''Partidul Național-Țărănist'', PNȚ) was an agrarian political party in the Kingdom of Romania. It w ...

(the main democratic opposition group), and the National Liberal Party-Brătianu—the pact was meant to prevent all attempt by Carol to manipulate the votes in elections. (A secondary and unexpected development was that the illegal PCR, which had decided to back the National Peasants' Party prior to the elections, eventually supported the electoral pact.) Tătărescu's own alliance policy rose the anger of his opponents inside the PNL, as he signed collaboration agreements with the fascist Romanian Front

The Romanian Front ( ro, Frontul Românesc, FR) was a moderate fascist party created in Romania in 1935. Led by former Prime Minister Alexandru Vaida-Voevod, it originated as a right-wing splinter group from the mainstream National Peasants' Part ...

and German Party.

The 1937 elections led to an unprecedented situation: although the PNL and Tătărescu had gained the largest percentage of the vote (almost 36%), they fell short of being awarded majority bonus

The majority bonus system (MBS) is a form of semi-proportional representation used in some European countries. Its feature is a majority bonus which gives extra seats or representation in an elected body to the party or to the joined parties with ...

(granted at 40% of the vote). As the far right had gathered momentum (the Guard, running under the name of "Everything for the Fatherland Party", had obtained 15.6% of the vote), Carol was faced with the threat of an Iron Guard government, which would have been one deeply opposed to all of his political principles: he called on a third party, Octavian Goga

Octavian Goga (; 1 April 1881 – 7 May 1938) was a Romanian politician, poet, playwright, journalist, and translator.

Life and politics

Goga was born in Rășinari, near Sibiu.

Goga was an active member in the Romanian nationalisti ...

's National Christian Party

The National Christian Party ( ro, Partidul Național Creștin) was a radical-right authoritarian and strongly antisemitic political party in Romania active between 1935 and 1938. It was formed by a merger of Octavian Goga's National Agrarian Pa ...

(coming from the anti-Semitic far right but deeply opposed to the Guard) to form a new cabinet in December of that year.

Consequently, Tătărescu renounced his offices inside the party, and, while keeping his office of general secretary, he was surpassed by the readmitted Gheorghe I. Brătianu

Gheorghe (George) I. Brătianu (January 28 1898 – April 23–27, 1953) was a Romanian politician and historian. A member of the Brătianu family and initially affiliated with the National Liberal Party (Romania, 1875), National Liberal Par ...

— who was elected to the new office of PNL vice president on 10 January 1938. After the failure of Goga's policies to curb the rise of their competitors, the king, backed by Tătărescu, resorted to dissolving all political parties on 30 May 1938, creating instead the National Renaissance Front

The National Renaissance Front ( ro, Frontul Renașterii Naționale, FRN; also translated as ''Front of National Regeneration'', ''Front of National Rebirth'', ''Front of National Resurrection'', or ''Front of National Renaissance'') was a Romani ...

.

Rearmament

As Prime Minister, Tătărescu showed particular concern for the modernization of theRomanian Armed Forces

The Land Forces, Air Force and Naval Forces of Romania are collectively known as the Romanian Armed Forces ( ro, Forțele Armate Române or ''Armata Română''). The current Commander-in-chief is Lieutenant General Daniel Petrescu who is manage ...

. Almost immediately after becoming Prime Minister, he established the Ministry of Armaments, chaired by himself. This ministry lasted for over three years before being dissolved on 23 February 1937, during his third cabinet.

Under Tătărăscu's premiership, Romania launched a ten-year rearmament program on 27 April 1935. Under this program, Romania acquired 248 Škoda 100 mm howitzers (delivered in the mid-1930s) and 180 Škoda 150 mm howitzers (delivered between 1936 and 1939). In 1936, Romania ordered 126 LT vz 35 tanks and 35 R-1 tankettes. These acquisitions from Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

were followed in 1937 by 12 Focke-Wulf Fw 58

The Focke-Wulf Fw 58 ''Weihe'' ( Harrier) was a German aircraft, built to fill a request by the ''Luftwaffe'' for a multi-role aircraft, to be used as an advanced trainer for pilots, gunners and radio operators.

Design and development

The Fw ...

aircraft, ordered from Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and delivered between April and June that same year. Romania employed German technicians to build a shipyard at Galați using materials supplied by the Reșița works

The Reșița Works are two companies, TMK Reșița and UCM Reșița, located in Reșița, in the Banat region of Romania. Founded in 1771 and operating under a single structure until 1948 and then from 1954 to 1962, during the Communist era they ...

. There, two submarines would be built between 1938 and 1943, among others ( ''Marsuinul'' and ''Rechinul''). The resumed and much improved trade relations with Škoda, following the disastrous " Škoda Affair" of the early 1930s, were credited to the energy and ability of Tătărăscu, "the soldier-politician who reversed the usual order in Romanian politics by placing the welfare of the country superior to the lust for graft". It is worth noting, however, that of the 35 tankettes and 126 tanks ordered during Tătărescu's premiership, only 10 of the former and 15 of the latter actually arrived in Romania before the end of his mandate at the end of 1937. Both of these orders were delivered in full during late 1938 and early 1939, respectively. In 1936, Romania also started producing the Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

PZL P.11

The PZL P.11 was a Polish fighter aircraft, designed and constructed during the early 1930s by Warsaw-based aircraft manufacturer PZL. Possessing an all-metal structure, metal-covering, and high-mounted gull wing, the type held the distinction of ...

fighter aircraft, of which 95 were ultimately built by IAR. In 1937, Romanian production of the improved PZL P.24 also commenced, with 25 fighters being built until 1939.

Second cabinet

In this context, Tătărescu chose to back the regime, as the PNL, like the National Peasants' Party, remained active in nominal clandestinity (as the law banning it had never been enforced any further). Having personally signed the document banning opposition parties, he was expelled from the PNL in April 1938, and contested the legitimacy of the action for the following years.Scurtu, "Politica...", p.18 Allegedly, his ousting was recommended byIuliu Maniu

Iuliu Maniu (; 8 January 1873 – 5 February 1953) was an Austro-Hungarian-born lawyer and Romanian politician. He was a leader of the National Party of Transylvania and Banat before and after World War I, playing an important role in the U ...

, leader of the National Peasants' Party's and, for the following years, the closest of Dinu Brătianu's political allies.

Soon after his second arrival to power, Tătărescu became noted for the enthusiastic support he gave to the modernist

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

sculptor Constantin Brâncuși, and directed state funds to finance the building of Brâncuși's '' The Endless Column'' complex in Târgu Jiu

Târgu Jiu () is the capital of Gorj County in the Oltenia region of Romania. It is situated on the Southern Sub-Carpathians, on the banks of the river Jiu. Eight localities are administered by the city: Bârsești, Drăgoieni, Iezureni, Polat ...

(completed in October 1938).

Alongside Alexandru Vaida-Voevod and Constantin Argetoianu

Constantin Argetoianu ( – 6 February 1955) was a Romanian politician, one of the best-known personalities of interwar Greater Romania, who served as the Prime Minister between 28 September and 23 November 1939. His memoirs, ''Memorii. Pentr ...

(whom he succeeded as Premier), Tătărescu became a dominant figure in the group of maverick pro-Carol politicians. After a bloody crackdown on the Iron Guard, the Front attempted to reunite political forces in a national government that was to back Carol's foreign policies in view of increasing threats on Romania's borders after the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. In 1945, Tătărescu stressed his belief that authoritarianism

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic voti ...

benefited Romania, and supported the view that Carol had meant to keep Romania out of the war.Pope Brewer Tătărescu's second cabinet was meant to reflect the latter policies, but it did not draw any support from traditional parties, and, in April 1940, Carol, assisted by Ernest Urdăreanu and Mihail Ghelmegeanu, began talks with the (by then much weaker) Iron Guard.

Tătărescu remained in office throughout the rest of the Phony War

The Phoney War (french: Drôle de guerre; german: Sitzkrieg) was an eight-month period at the start of World War II, during which there was only one limited military land operation on the Western Front, when French troops invaded Germa ...

, until the fall of France, and his cabinet signed an economic agreement with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

(through which virtually all Romanian exports were directed towards the latter country) and saw the crumbling of Romania's alliance with the United Kingdom and France. The cabinet was brought down by the cession of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina

Bukovinagerman: Bukowina or ; hu, Bukovina; pl, Bukowina; ro, Bucovina; uk, Буковина, ; see also other languages. is a historical region, variously described as part of either Central or Eastern Europe (or both).Klaus Peter Berge ...

to the Soviet Union (effects of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that enabled those powers to partition Poland between them. The pact was signed in Moscow on 23 August 1939 by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ri ...

), as well as by Carol's attempt to appease German hostility by dissolving it, replacing Tătărescu with Ion Gigurtu, and recreating the Front as the totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and reg ...

''Party of the Nation''.

World War

After the

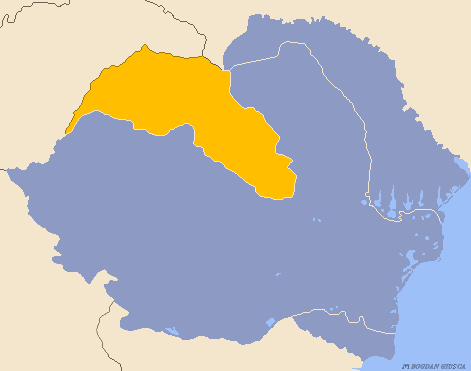

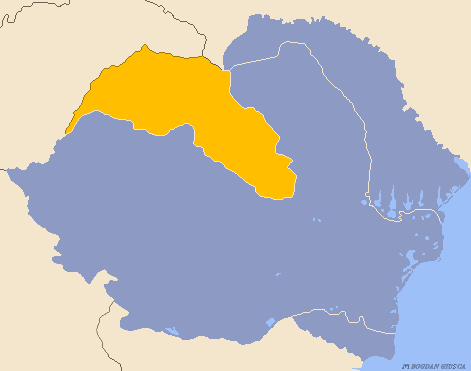

After the Second Vienna Award

The Second Vienna Award, also known as the Vienna Diktat, was the second of two territorial disputes that were arbitrated by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. On 30 August 1940, they assigned the territory of Northern Transylvania, including all o ...

(when Northern Transylvania was lost to Hungary), confirming Carol's failure to preserve both the country's neutrality and it's territorial integrity, Romania was taken over by an Iron Guard dictatorial government (the National Legionary State

The National Legionary State was a totalitarian fascist regime which governed Romania for five months, from 14 September 1940 until its official dissolution on 14 February 1941. The regime was led by General Ion Antonescu in partnership with the ...

). Speaking five years later, Dinu Brătianu

Dinu Brătianu (January 13, 1866 – May 20, 1950), born Constantin I. C. Brătianu, was a Romanian engineer and politician who led the National Liberal Party (PNL) starting in 1934.

Life Early career

Born at the estate of ''Florica'', in ...

placed the blame for the serious developments on Tătărescu's own actions, addressing him directly:

"I remind you: ..you have contributed directly, in 1940, in steering the country towards a foreign policy that, as one could tell even then, was to prove ill-fated and which led us to the loathsome Vienna settlement, one which you have supported inside the Crown Council .."Brătianu, in Țurlea, p.29On 26 November 1940, the Iron Guard began a bloody retaliation against various political figures who had served under Carol (following a late investigation into the 1938 killing of

Corneliu Zelea Codreanu

Corneliu Zelea Codreanu (; born Corneliu Codreanu, according to his birth certificate; 13 September 1899 – 30 November 1938) was a Romanian politician of the far right, the founder and charismatic leader of the Iron Guard or ''The Legion o ...

, the movement's founder and early leader, by Carol's authorities). Tătărescu and Constantin Argetoianu

Constantin Argetoianu ( – 6 February 1955) was a Romanian politician, one of the best-known personalities of interwar Greater Romania, who served as the Prime Minister between 28 September and 23 November 1939. His memoirs, ''Memorii. Pentr ...

were among the second wave of captured politicians (on 27 November), and were destined for arbitrary execution; they were, however, saved by the intervention of regular police forces, most of whom had grown hostile to the Guardist militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

s.

Retired from political life during the war, he was initially sympathetic to Ion Antonescu's pro-German dictatorship (''see Romania during World War II

Following the outbreak of World War II on 1 September 1939, the Kingdom of Romania under King Carol II officially adopted a position of neutrality. However, the rapidly changing situation in Europe during 1940, as well as domestic political uph ...

'')—Dinu Brătianu, who remained in opposition to the Antonescu regime, made mention an official visit to Bessarabia, recovered after the start of Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

, when Tătărescu had accompanied Antonescu, "thus making common cause with his warmongering action". At the time, his daughter Sandra Tătărescu Negropontes worked as an ambulance

An ambulance is a medically equipped vehicle which transports patients to treatment facilities, such as hospitals. Typically, out-of-hospital medical care is provided to the patient during the transport.

Ambulances are used to respond to medi ...

driver for the Romanian Red Cross

The Romanian Red Cross (CRR), also known as the National Society of Red Cross from Romania (''Societatea Naționalǎ de Cruce Roșie din România''), is a volunteer-led, humanitarian organization that provides emergency assistance, disaster relie ...

.

In the end, Tătărescu became involved in negotiations aimed at withdrawing Romania from the conflict, and, while beginning talks with the Romanian Communist Party (PCR), tried to build foreign connections to support Romania's cause following the inevitable defeat; he thus corresponded with Edvard Beneš

Edvard Beneš (; 28 May 1884 – 3 September 1948) was a Czech politician and statesman who served as the president of Czechoslovakia from 1935 to 1938, and again from 1945 to 1948. He also led the Czechoslovak government-in-exile 1939 to 194 ...

, leader of the Czechoslovak

Czechoslovak may refer to:

*A demonym or adjective pertaining to Czechoslovakia (1918–93)

**First Czechoslovak Republic (1918–38)

**Second Czechoslovak Republic (1938–39)

**Third Czechoslovak Republic (1948–60)

**Fourth Czechoslovak Repub ...

government in exile

A government in exile (abbreviated as GiE) is a political group that claims to be a country or semi-sovereign state's legitimate government, but is unable to exercise legal power and instead resides in a foreign country. Governments in exile ...

in England.Tejchman Beneš, who had already been discussing matters involving Romania with Richard Franasovici and Grigore Gafencu, and had agreed to support the Romanian cause, informed the Allied governments of Tătărescu's designs.

Tătărescu later contrasted his diplomatic approach with the strategy of Barbu Știrbey

Prince Barbu Alexandru Știrbey (; 4 November 1872 – 24 March 1946) was 30th Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Romania in 1927. He was the son of Prince Alexandru Știrbey and his wife Princess Maria Ghika-Comănești, and grandson of another ...

(who had only attempted an agreement with the Western Allies

The Allies, formally referred to as the United Nations from 1942, were an international military coalition formed during the Second World War (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis powers, led by Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, and Fascist Italy ...

in Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the Capital city, capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, List of ...

, instead of opening relations with the Soviets). Initially meeting with the refusal of Iuliu Maniu

Iuliu Maniu (; 8 January 1873 – 5 February 1953) was an Austro-Hungarian-born lawyer and Romanian politician. He was a leader of the National Party of Transylvania and Banat before and after World War I, playing an important role in the U ...

and Dinu Brătianu (who decided to invest their trust in Știrbey), he was relatively successful after the Cairo initiative proved fruitless: the two traditional parties accepted collaboration with the bloc formed by the PCR, the Romanian Social Democratic Party, the Ploughmen's Front

The Ploughmen's Front ( ro, Frontul Plugarilor) was a Romanian left-wing agrarian-inspired political organisation of ploughmen, founded at Deva in 1933 and led by Petru Groza. At its peak in 1946, the Front had over 1 million members.

Histor ...

, and the Socialist Peasants' Party, leading to the formation of the short-lived and unstable ''National Democratic Bloc'' (BND) in June 1944. It overthrew Antonescu in August, by means of the successful King Michael Coup

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

.

Alliance with the Communists

Tătărescu returned to the PNL later in 1944—after the SovietRed Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army ( Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, afte ...

had entered Romania and the country had become an Allied state, political parties were again allowed to register. Nevertheless, Tătărescu was again opposed to the party leaders Dinu and Gheorghe I. Brătianu

Gheorghe (George) I. Brătianu (January 28 1898 – April 23–27, 1953) was a Romanian politician and historian. A member of the Brătianu family and initially affiliated with the National Liberal Party (Romania, 1875), National Liberal Par ...

, and split to form his own group in June–July 1945. Dinu Brătianu convened the PNL leadership and formally excluded Tătărescu and his partisans, citing their support for dictatorial regimes.

As the PCR, which was growing more influential (with the backing of Soviet occupation

During World War II, the Soviet Union occupied and annexed several countries effectively handed over by Nazi Germany in the secret Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of 1939. These included the eastern regions of Poland (incorporated into two different ...

) while generally lacking popular appeal, sought to form alliances with various forces in order to increase its backing, Tătărescu declared his group to be left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

and Social liberal

Social liberalism (german: Sozialliberalismus, es, socioliberalismo, nl, Sociaalliberalisme), also known as new liberalism in the United Kingdom, modern liberalism, or simply liberalism in the contemporary United States, left-liberalism ...

, while attempting to preserve a middle course in the new political setting, by pleading for close relations to be maintained with both the Soviet Union and the Western Allies. N. D. Cocea, a prominent socialist who had joined the PNL, represented the faction in talks for an alliance with the Communists. The agreement, favored by Ana Pauker

Ana Pauker (born Hannah Rabinsohn; 13 February 1893 – 3 June 1960) was a Romanian communist leader and served as the country's foreign minister in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Ana Pauker became the world's first female foreign minister whe ...

, was vehemently opposed by another member of the Communist leadership, Lucrețiu Pătrășcanu

Lucrețiu Pătrășcanu (; November 4, 1900 – April 17, 1954) was a Romanian communist politician and leading member of the Communist Party of Romania (PCR), also noted for his activities as a lawyer, sociologist and economist. For a while, he ...

, who argued in favor of "making a distinction inside the bourgeoisie", and collaborating with the main PNL, while calling Tătărescu's faction "a gang of con artists, blackmailers, and well-known bribe

Bribery is the offering, giving, receiving, or soliciting of any item of value to influence the actions of an official, or other person, in charge of a public or legal duty. With regard to governmental operations, essentially, bribery is "Corru ...

rs".

Tătărescu became Foreign Minister and vice president of the government in the cabinet of Petru Groza

Petru Groza (7 December 1884 – 7 January 1958) was an Austro-Hungarian-born Romanian politician, best known as the first Prime Minister of the Communist Party-dominated government under Soviet occupation during the early stages of the Commu ...

when the latter came into office after Soviet pressures in 1945; his faction had been awarded leadership of four other ministries—Finance, with three successive office-holders (of whom the last was Alexandru Alexandrini), Public Works, with Gheorghe Vântu, Industry (with Petre N. Bejan), and Religious Affairs, with Radu Roșculeț. He indirectly helped the PCR carry out an electoral fraud during the general election in 1946 by failing to reply to American proposals for organizing fair elections. At the Paris Conference, where he was accompanied by the PCR leaders Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej

Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej (; 8 November 1901 – 19 March 1965) was a Romanian communist politician and electrician. He was the first Communist leader of Romania from 1947 to 1965, serving as first secretary of the Romanian Communist Party ...

and Pătrășcanu, he acknowledged the dissolution of ''Greater Romania

The term Greater Romania ( ro, România Mare) usually refers to the borders of the Kingdom of Romania in the interwar period, achieved after the Great Union. It also refers to a pan-nationalist idea.

As a concept, its main goal is the creation ...

'' under the provisions of the new Treaty (1947).

1947 and after

Tensions between his group with the PCR occurred when the former founded itself as a party under the name of ''National-Liberal Party'' (commonly known as theNational Liberal Party-Tătărescu

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, c ...

), and, in June–July 1945, proclaimed its goal to be the preservation of property and a middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. Com ...

under a new regime. Of himself and his principles, Tătărescu stated:

"I am not a communist. Taking in view my attitudes towards mankind, society, property, I am not a communist. Thus, the new orientation in external politics which I demand for my country cannot be accused of being determined by affinities or sympathies of doctrine."Speaking in retrospect, Gheorghiu-Dej indicated the actual relation between his party and Tătărescu's: "we have had to tolerate by our side a

capitalist

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, priva ...

-gentry

Gentry (from Old French ''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest c ...

political group, Tătărescu's group".

Tătărescu himself continued to show his support for several PCR policies: in the summer of 1947, he condemned the United States for having protested against the repression of forces in the opposition. Nevertheless, at around the same time, he issued his own critique of the Groza government, becoming the target of violent attacks initiated by Miron Constantinescu

Miron Constantinescu (13 December 1917 – 18 July 1974) was a Romanian communist politician, a leading member of the Romanian Communist Party (PCR, known as PMR for a period of his lifetime), as well as a Marxist sociologist, historian, academic, ...

in the PCR press. Consequently, he was singled out for negligence in office when, during the kangaroo trial of Iuliu Maniu

Iuliu Maniu (; 8 January 1873 – 5 February 1953) was an Austro-Hungarian-born lawyer and Romanian politician. He was a leader of the National Party of Transylvania and Banat before and after World War I, playing an important role in the U ...

(''see Tămădău Affair''), it was alleged that several employees of his ministry had conspired against the government. ''Scînteia

''Scînteia'' (Romanian for "The Spark") was the name of two newspapers edited by Communist groups at different intervals in Romanian history. The title is a homage to the Russian language paper ''Iskra''. It was known as ''Scânteia'' until th ...

'', the official voice of the PCR, wrote of all National Liberal Party-Tătărescu offices in the government: "The rot is all-encompassing! It has to be removed!".

Tătărescu resigned his office on 6 November 1947, and was replaced by the Communist Ana Pauker

Ana Pauker (born Hannah Rabinsohn; 13 February 1893 – 3 June 1960) was a Romanian communist leader and served as the country's foreign minister in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Ana Pauker became the world's first female foreign minister whe ...

. For the following two months, he was sidelined in his own party by PCR pressures, and removed from its leadership in January 1948 (being replaced with Petre N. Bejan—the party was subsequently known as ''National Liberal Party-Petre N. Bejan''). One of his last actions as cabinet member had been to sign the document officially rejecting the Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred over $13 billion (equivalent of about $ in ) in economic re ...

.

After the proclamation of the ''People's Republic of Romania

The Socialist Republic of Romania ( ro, Republica Socialistă România, RSR) was a Marxist–Leninist one-party socialist state that existed officially in Romania from 1947 to 1989. From 1947 to 1965, the state was known as the Romanian Peopl ...

'' on 30 December 1947, the existence of all parties other than the PCR had become purely formal, and, after the elections of 28 March the one-party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system, or single-party system is a type of sovereign state in which only one political party has the right to form the government, usually based on the existing constitution. All other parties ...

was confirmed by legislation. He was arrested on 5 May 1950, and held in the notorious Sighet prison

The Sighet prison, located in the city of Sighetu Marmației, Maramureș County, Romania, was used by Romania to hold criminals, prisoners of war, and political prisoners. It is now the site of the Sighet Memorial Museum, part of the Memorial ...

(alongside three of his brothers— Ștefan Tătărescu included—and his former collaborator Bejan). His son Tudor, who was living in Paris, suffered from schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a mental disorder characterized by continuous or relapsing episodes of psychosis. Major symptoms include hallucinations (typically hearing voices), delusions, and disorganized thinking. Other symptoms include social wit ...

after 1950, and had to be committed to an institution (where he died in 1955). Sandra Tătărescu Negropontes was also imprisoned in 1950, and released three years later, upon the death of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

.

One of Gheorghe Tătărescu's last appearances in public was his stand as one of the prosecution's witnesses in the 1954 trial of Lucrețiu Pătrășcanu

Lucrețiu Pătrășcanu (; November 4, 1900 – April 17, 1954) was a Romanian communist politician and leading member of the Communist Party of Romania (PCR), also noted for his activities as a lawyer, sociologist and economist. For a while, he ...

, when he claimed that the defendant had been infiltrated into the PCR during the time when he had been premier (Pătrășcanu was posthumously cleared of all charges). Released in 1955, Tătărescu died in Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north of ...

, less than two years later.Gogan; Petru According to Sanda Tătărescu Negropontes, this came as a result of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, i ...

contracted while in detention.

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Tatarescu, Gheorghe 1886 births 1957 deaths People from Târgu Jiu Prime Ministers of Romania Deputy Prime Ministers of Romania Romanian Ministers of Defence Romanian Ministers of Foreign Affairs Romanian Ministers of Industry and Commerce Romanian Ministers of Interior Honorary members of the Romanian Academy Members of the Chamber of Deputies (Romania) National Liberal Party (Romania) politicians National Renaissance Front politicians Romanian people of World War II World War II political leaders Romanian delegation to the Paris Peace Conference of 1946 Members of the Romanian Orthodox Church Carol I National College alumni University of Paris alumni 20th-century Romanian lawyers Inmates of Sighet prison Heads of government who were later imprisoned 20th-century deaths from tuberculosis Tuberculosis deaths in Romania