Germanic paganism or Germanic religion refers to the traditional, culturally significant religion of the

Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and ear ...

. With a chronological range of at least one thousand years in an area covering Scandinavia, the British Isles, modern Germany, and at times other parts of Europe, the beliefs and practices of Germanic paganism varied. Scholars typically assume some degree of continuity between Roman-era beliefs and those found in

Norse paganism

Old Norse religion, also known as Norse paganism, is the most common name for a branch of Germanic religion which developed during the Proto-Norse period, when the North Germanic peoples separated into a distinct branch of the Germanic peopl ...

, as well as between Germanic religion and reconstructed

Indo-European religion

Proto-Indo-European mythology is the body of myths and deities associated with the Proto-Indo-Europeans, the hypothetical speakers of the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European language. Although the mythological motifs are not directly atteste ...

and post-conversion

folklore

Folklore is shared by a particular group of people; it encompasses the traditions common to that culture, subculture or group. This includes oral traditions such as tales, legends, proverbs and jokes. They include material culture, rangin ...

, though the precise degree and details of this continuity are subjects of debate. Germanic religion was influenced by neighboring cultures, including that of the Celts, the Romans, and, later, by Christian religion. Very few sources exist that were written by pagan adherents themselves; instead, most were written by outsiders and can thus can present problems for reconstructing authentic Germanic beliefs and practices.

Some basic aspects of Germanic belief can be reconstructed, including one or more origin myths, a myth of the end of the world, a general belief in the inhabited world being a "

middle-earth

Middle-earth is the fictional setting of much of the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy. The term is equivalent to the '' Miðgarðr'' of Norse mythology and ''Middangeard'' in Old English works, including ''Beowulf''. Middle-earth is ...

", as well as some aspects of belief in fate and the afterlife. The Germanic peoples believed in a multitude of gods, and in other supernatural beings such as

jötnar (often glossed as giants),

dwarfs,

elves

An elf () is a type of humanoid supernatural being in Germanic mythology and folklore. Elves appear especially in North Germanic mythology. They are subsequently mentioned in Snorri Sturluson's Icelandic Prose Edda. He distinguishes ...

, and

dragons. Roman-era sources, using Roman names, mention several important male gods, as well as several goddesses such as

Nerthus and the

matronae

The Matres (Latin for "mothers") and Matronae (Latin for "matrons") were female deities venerated in Northwestern Europe, of whom relics are found dating from the first to the fifth century AD. They are depicted on votive offerings and altars th ...

. Early medieval sources identify a pantheon consisting of the gods *Wodanaz (

Odin

Odin (; from non, Óðinn, ) is a widely revered god in Germanic paganism. Norse mythology, the source of most surviving information about him, associates him with wisdom, healing, death, royalty, the gallows, knowledge, war, battle, victory, ...

), *Thunraz (

Thor

Thor (; from non, Þórr ) is a prominent god in Germanic paganism. In Norse mythology, he is a hammer-wielding god associated with lightning, thunder, storms, sacred groves and trees, strength, the protection of humankind, hallowing, ...

), *Tiwaz (

Tyr), and *Frijjō (

Frigg), as well as numerous other gods, many of whom are only attested from Norse sources (see

Proto-Germanic folklore).

Textual and archaeological sources allow the reconstruction of aspects of Germanic ritual and practice. These include well-attested burial practices, which likely had religious significance, such as rich grave goods and the burial in ships or wagons. Wooden carved figures that may represent gods have been discovered in bogs throughout northern Europe, and rich sacrificial deposits, including objects, animals, and human remains, have been discovered in springs, bogs, and under the foundations of new structures. Evidence for sacred places includes not only natural locations but also early evidence for the construction of structures such as temples and the worship of standing poles in some places. Other known Germanic religious practices include divination and magic, and there is some evidence for festivals and the existence of priests.

Subject and terminology

Definition

Germanic religion is principally defined as the religious traditions of speakers of Germanic languages (the

Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and ear ...

). The term "religion" in this context is itself controversial,

Bernhard Maier

Bernhard Maier (born 1963 in Oberkirch, Baden) is a German professor of religious studies, who publishes mainly on Celtic culture and religion.

Maier studied comparative religion, comparative linguistics, Celtic and Semitic studies at the Al ...

noting that it "implies a specifically modern point of view, which reflects the modern conceptual isolation of 'religion' from other aspects of culture". Never a unified or codified set of beliefs or practices, Germanic religion showed strong regional variations and

Rudolf Simek

Rudolf Simek (born 21 February 1954) is an Austrian philologist and religious studies scholar who is Professor and Chair of Ancient German and Nordic Studies at the University of Bonn. Simek specializes in Germanic studies, and is the author o ...

writes that it is better to refer to "Germanic ''religions''". In many contact areas (e.g.

Rhineland

The Rhineland (german: Rheinland; french: Rhénanie; nl, Rijnland; ksh, Rhingland; Latinised name: ''Rhenania'') is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly its middle section.

Term

Historically, the Rhinelands ...

and eastern and northern Scandinavia), Germanic paganism was similar to neighboring religions such as those of the

Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

,

Celts

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient ...

, or

Finnic peoples

The Finnic or Fennic peoples, sometimes simply called Finns, are the nations who speak languages traditionally classified in the Finnic (now commonly '' Finno-Permic'') language family, and which are thought to have originated in the region of ...

. The use of the qualifier "Germanic" (e.g. "Germanic religion" and its variants) remains common in

German-language

German ( ) is a West Germanic language mainly spoken in Central Europe. It is the most widely spoken and official or co-official language in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, and the Italian province of South Tyrol. It is also a ...

scholarship, but is less commonly used in English and other scholarly languages, where scholars usually specify which branch of paganism is meant (e.g.

Norse paganism

Old Norse religion, also known as Norse paganism, is the most common name for a branch of Germanic religion which developed during the Proto-Norse period, when the North Germanic peoples separated into a distinct branch of the Germanic peopl ...

or

Anglo-Saxon paganism

Anglo-Saxon paganism, sometimes termed Anglo-Saxon heathenism, Anglo-Saxon pre-Christian religion, or Anglo-Saxon traditional religion, refers to the religious beliefs and practices followed by the Anglo-Saxons between the 5th and 8th centurie ...

). The term "Germanic religion" is sometimes applied to practices dating to as early as the

Stone Age

The Stone Age was a broad prehistoric period during which stone was widely used to make tools with an edge, a point, or a percussion surface. The period lasted for roughly 3.4 million years, and ended between 4,000 BC and 2,000 BC, with ...

or

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

, but its use is more generally restricted to the time period after the Germanic languages had

become distinct from other

Indo-European languages

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, D ...

(early

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly ...

). Germanic paganism covers a period of around one thousand years in terms of written sources, from the first reports in Roman sources to the final conversion to Christianity.

Continuity

Because of the amount of time and space covered by the term "Germanic religion", controversy exists as to the degree of continuity of beliefs and practices between the earliest attestations in Tacitus and the later attestations of Norse paganism from the high Middle Ages. Many scholars argue for continuity, seeing evidence of commonalities between the Roman, early medieval, and Norse attestations, while many other scholars are skeptical. The majority of Germanic gods attested by name during the Roman period cannot be related to a later Norse god; many names attested in the Nordic sources are similarly without any known non-Nordic equivalents. The much higher number of sources on Scandinavian religion has led to a methodologically problematic tendency to use Scandinavian material to complete and interpret the much more sparsely attested information on continental Germanic religion.

Most scholars accept some form of continuity between

Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Du ...

and Germanic religion, but the degree of continuity is a subject of controversy. Jens Peter Schjødt writes that while many scholars view comparisons of Germanic religion with other attested Indo-European religions positively, "just as many, or perhaps even more, have been sceptical". While supportive of Indo-European comparison, Schjødt notes that the "dangers" of comparison are taking disparate elements out of context and arguing that myths and mythical structures found around the world must be Indo-European just because they appear in multiple Indo-European cultures.

Bernhard Maier

Bernhard Maier (born 1963 in Oberkirch, Baden) is a German professor of religious studies, who publishes mainly on Celtic culture and religion.

Maier studied comparative religion, comparative linguistics, Celtic and Semitic studies at the Al ...

argues that similarities with other Indo-European religions do not necessarily result from a common origin, but can also be the result of convergence.

Continuity also concerns the question of whether popular, post-conversion beliefs and practices (

folklore

Folklore is shared by a particular group of people; it encompasses the traditions common to that culture, subculture or group. This includes oral traditions such as tales, legends, proverbs and jokes. They include material culture, rangin ...

) found among Germanic speakers up to the modern day reflect a continuity with earlier Germanic religion. Earlier scholars, beginning with

Jacob Grimm

Jacob Ludwig Karl Grimm (4 January 1785 – 20 September 1863), also known as Ludwig Karl, was a German author, linguist, philologist, jurist, and folklorist. He is known as the discoverer of Grimm's law of linguistics, the co-author of t ...

, believed that modern folklore was of ancient origin and had changed little over the centuries, which allowed the use of folklore and

fairy tales

A fairy tale (alternative names include fairytale, fairy story, magic tale, or wonder tale) is a short story that belongs to the folklore genre. Such stories typically feature magic (paranormal), magic, incantation, enchantments, and mythical ...

as sources of Germanic religion. These ideas later came under the influence of

völkisch ideology, which stressed the organic unity of a Germanic "national spirit" (), as expressed in

Otto Höfler's "Germanic continuity theory". As a result, the use of folklore as a source went out of fashion after World War II, especially in Germany, but has experienced a revival since the 1990s in Nordic scholarship. Today, scholars are cautious in their use of folkloric material, keeping in mind that most was collected long after the conversion and the advent of writing. Areas where continuity can be noted include agrarian rites and magical ideas, as well as the root elements of some folktales.

Sources

Sources on Germanic religion can be divided between primary sources and secondary sources. Primary sources include texts, structures, place names, personal names, and objects that were created by devotees of the religion; secondary sources are normally texts that were written by outsiders.

Primary sources

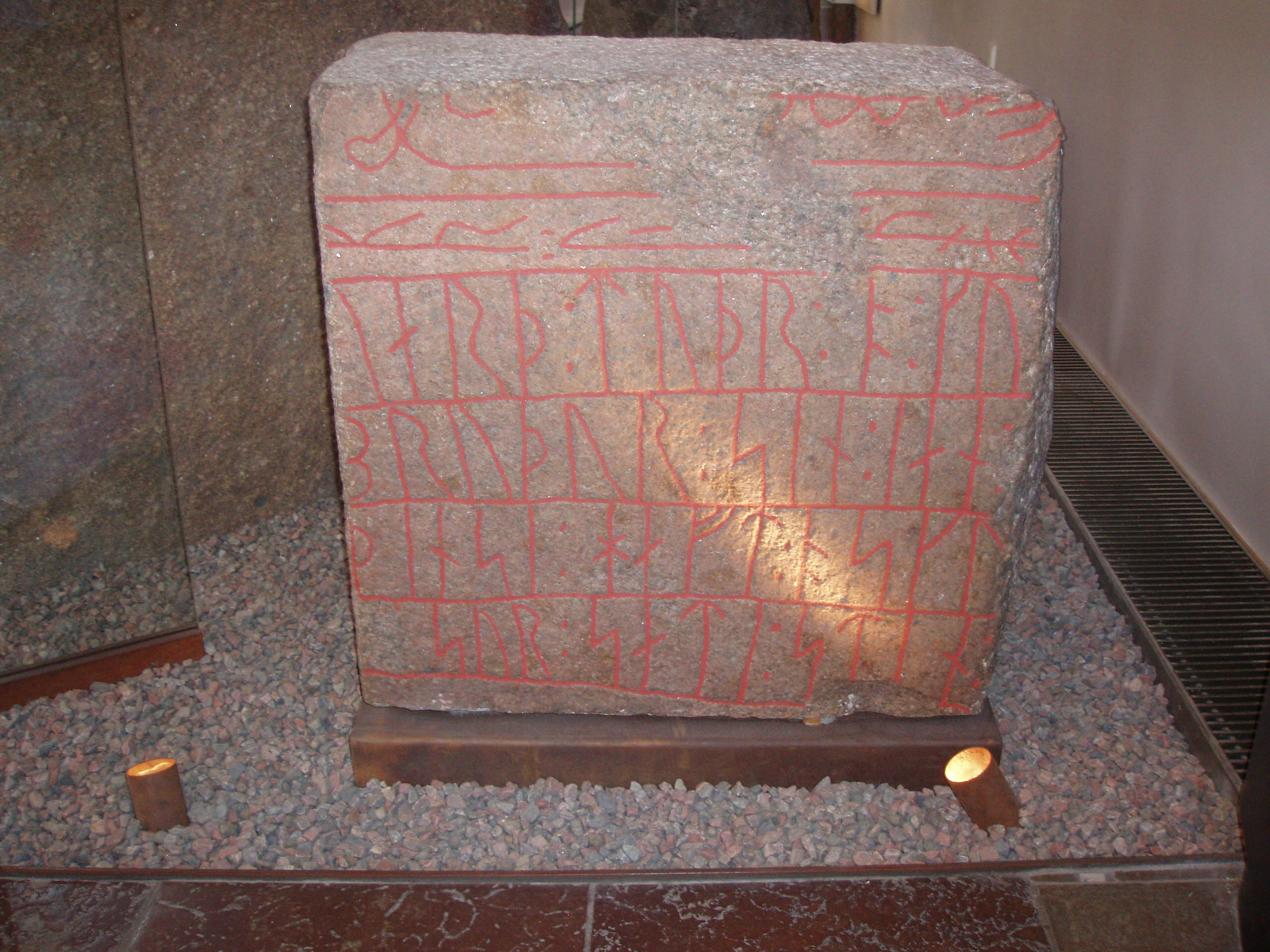

Examples of primary sources include some Latin alphabet and Runic inscriptions, as well as poetic texts such as the

Merseburg Charms

The Merseburg charms or Merseburg incantations (german: die Merseburger Zaubersprüche) are two medieval magic spells, charms or incantations, written in Old High German. They are the only known examples of Germanic pagan belief preserved in the ...

and heroic texts that may date from pagan times, but were written down by Christians. The poems of the

Edda, while pagan in origin, continued to circulate orally in a Christian context before being written down, which makes an application to pre-Christian times difficult. In contrast, pre-Christian images such as on

bracteates,

gold foil figures, and rune and picture stones are direct attestations of Germanic religion. The interpretation of these images is not always immediately obvious. Archaeological evidence is also extensive, including evidence from burials and sacrificial sites. Ancient votive altars from the Rhineland often contain inscriptions naming gods with Germanic or partially Germanic names.

Secondary sources

Most textual sources on Germanic religion were written by outsiders. The chief textual source for Germanic religion in the Roman period is Tacitus's ''Germania''. There are problems with Tacitus's work, however, as it is unclear how much he really knew about the Germanic peoples he described and because he employed numerous

topoi

In mathematics, a topos (, ; plural topoi or , or toposes) is a category that behaves like the category of sheaves of sets on a topological space (or more generally: on a site). Topoi behave much like the category of sets and possess a noti ...

dating back to

Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria (Italy). He is known fo ...

that were used when describing a barbarian people. Unlike some other Roman authors, Tacitus had not visited Germanic territories. Furthermore, Tacitus' reliability as a source can be characterized by his rhetorical tendencies, since one of the purposes of ''Germania'' was to present his Roman compatriots with an example of the virtues he believed they were missing. Julius Caesar,

Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea ( grc-gre, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; la, Procopius Caesariensis; – after 565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman gen ...

, and other ancient authors also offer some information on Germanic religion.

Textual sources for post-Roman continental Germanic religion are written by Christian authors: Some of the gods of the

Lombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 an ...

are described in the 7th-century ''

Origo gentis Langobardorum'' ("Origin of the Lombard People"), while a small amount of information on the religion of the pagan

Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools ...

can be found in

Gregory of Tours

Gregory of Tours (30 November 538 – 17 November 594 AD) was a Gallo-Roman historian and Bishop of Tours, which made him a leading prelate of the area that had been previously referred to as Gaul by the Romans. He was born Georgius Floren ...

's late 6th-century ("History of the Franks"). An important source for the pre-Christian religion of the Anglo-Saxons is

Bede

Bede ( ; ang, Bǣda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom ...

's ''

Ecclesiastical History of the English People

The ''Ecclesiastical History of the English People'' ( la, Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum), written by Bede in about AD 731, is a history of the Christian Churches in England, and of England generally; its main focus is on the conflict b ...

'' (c. 731). Other sources include historians such as

Jordanes

Jordanes (), also written as Jordanis or Jornandes, was a 6th-century Eastern Roman bureaucrat widely believed to be of Gothic descent who became a historian later in life. Late in life he wrote two works, one on Roman history ('' Romana'') an ...

(6th century CE) and

Paul the Deacon

Paul the Deacon ( 720s 13 April in 796, 797, 798, or 799 AD), also known as ''Paulus Diaconus'', ''Warnefridus'', ''Barnefridus'', or ''Winfridus'', and sometimes suffixed ''Cassinensis'' (''i.e.'' "of Monte Cassino"), was a Benedictine monk, ...

(8th century), as well as

saint lives

A hagiography (; ) is a biography of a saint or an ecclesiastical leader, as well as, by extension, an adulatory and idealized biography of a founder, saint, monk, nun or icon in any of the world's religions. Early Christian hagiographies might ...

and Christian legislation against various practices.

Textual sources for Scandinavian religion are much more extensive. They include the aforementioned poems of the Poetic Edda, Eddic poetry found in other sources, the

Prose Edda

The ''Prose Edda'', also known as the ''Younger Edda'', ''Snorri's Edda'' ( is, Snorra Edda) or, historically, simply as ''Edda'', is an Old Norse textbook written in Iceland during the early 13th century. The work is often assumed to have been ...

, which is usually attributed to the Icelander

Snorri Sturluson

Snorri Sturluson ( ; ; 1179 – 22 September 1241) was an Icelandic historian, poet, and politician. He was elected twice as lawspeaker of the Icelandic parliament, the Althing. He is commonly thought to have authored or compiled portions of th ...

(13th century CE),

Skaldic poetry

A skald, or skáld (Old Norse: , later ; , meaning "poet"), is one of the often named poets who composed skaldic poetry, one of the two kinds of Old Norse poetry, the other being Eddic poetry, which is anonymous. Skaldic poems were traditional ...

, poetic

kennings with mythological content, Snorri's ''

Heimskringla'', the ''

Gesta Danorum'' of

Saxo Grammaticus (12th-13th century CE), Icelandic historical writing and

saga

is a series of science fantasy role-playing video games by Square Enix. The series originated on the Game Boy in 1989 as the creation of Akitoshi Kawazu at Square. It has since continued across multiple platforms, from the Super NES to th ...

s, as well as outsider sources such as the report on the

Rus' made by the Arab traveler

Ahmad ibn Fadlan

Aḥmad ibn Faḍlān ibn al-ʿAbbās ibn Rāšid ibn Ḥammād, ( ar, أحمد بن فضلان بن العباس بن راشد بن حماد; ) commonly known as Ahmad ibn Fadlan, was a 10th-century Muslim traveler, famous for his account of hi ...

(10th century), the ''

Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum'' by bishop

Adam of Bremen

Adam of Bremen ( la, Adamus Bremensis; german: Adam von Bremen) (before 1050 – 12 October 1081/1085) was a German medieval chronicler. He lived and worked in the second half of the eleventh century. Adam is most famous for his chronicle ''Gest ...

(11th century CE), and various saints' lives.

Outside influences and syncretism

Germanic religion has been influenced by the beliefs of other cultures. Celtic and Germanic peoples were in close contact in the first millenium BCE, and evidence for Celtic influence on Germanic religion is found in religious vocabulary. This includes, for instance, the name of the deity *''Þun(a)raz'' (

Thor

Thor (; from non, Þórr ) is a prominent god in Germanic paganism. In Norse mythology, he is a hammer-wielding god associated with lightning, thunder, storms, sacred groves and trees, strength, the protection of humankind, hallowing, ...

), which is identical to Celtic *''Toranos'' (

Taranis), the Germanic name of the

runes

Runes are the letters in a set of related alphabets known as runic alphabets native to the Germanic peoples. Runes were used to write various Germanic languages (with some exceptions) before they adopted the Latin alphabet, and for specialised ...

(Celtic *''rūna'' 'secret, magic'), and the Germanic name for the

sacred groves, *''nemeđaz'' (Celtic ''

nemeton''). Evidence for further close religious contacts is found in the Roman-era Rhineland goddesses known as

matronae

The Matres (Latin for "mothers") and Matronae (Latin for "matrons") were female deities venerated in Northwestern Europe, of whom relics are found dating from the first to the fifth century AD. They are depicted on votive offerings and altars th ...

, which display both Celtic and Germanic names. During the Viking Age, there is evidence for continued Irish mythological and Insular Celtic influence on Norse religion.

During the Roman period, Germanic gods were equated with Roman gods and worshiped with Roman names in contact zones, a process known as ; later, Germanic names were also applied to Roman gods ().

This was done to better understand one another's religions as well as to

syncretize elements of each religion. This resulted in various aspects of Roman worship and iconography being adopted among the Germanic peoples, including those living at some distance from the Roman frontier.

In later centuries, Germanic religion was also influenced by Christianity. There is evidence for the appropriation of Christian symbolism on gold bracteates and possibly in the understanding of the roles of particular gods. The

Christianization of the Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples underwent gradual Christianization in the course of late antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. By AD 700, England and Francia were officially Christian, and by 1100 Germanic paganism had also ceased to have political influenc ...

was a long process during which there are many textual and archaeological examples of the co-existence and sometimes mixture of pagan and Christian worship and ideas. Christian sources frequently equate Germanic gods with

demon

A demon is a malevolent supernatural entity. Historically, belief in demons, or stories about demons, occurs in religion, occultism, literature, fiction, mythology, and folklore; as well as in Media (communication), media such as comics, video ...

s and forms of the

devil

A devil is the personification of evil as it is conceived in various cultures and religious traditions. It is seen as the objectification of a hostile and destructive force. Jeffrey Burton Russell states that the different conceptions of ...

().

Cosmology

Creation myth

It is likely that multiple creation myths existed among Germanic peoples. Creation myths are not attested for the continental Germanic peoples or Anglo-Saxons; Tacitus includes the story of Germanic tribes' descent from the gods

Tuisto

According to Tacitus's '' Germania'' (AD 98), Tuisto (or Tuisco) is the legendary divine ancestor of the Germanic peoples. The figure remains the subject of some scholarly discussion, largely focused upon etymological connections and compariso ...

(or Tuisco), who is born from the earth, and

Mannus (''Germania'' chapter 2), resulting in a division into three or five Germanic subgroups. Tuisto appears to mean "twin" or "double-being", suggesting that he was a hermaphroditic being capable of impregnating himself. These gods are only attested in ''Germania''. It is not possible to decide based on Tacitus's report whether the myth was meant to describe an origin of the gods or of humans. Tacitus also includes a second myth: the

Semnones

The Semnones were a Germanic and specifically a Suevian people, who were settled between the Elbe and the Oder in the 1st century when they were described by Tacitus in ''Germania'':

"The Semnones give themselves out to be the most ancient and r ...

believed that they originated in a sacred

grove of fetters where a particular god dwelled (''Germania'' chapter 39, for more on this see

"Sacred trees, groves, and poles" below).

The only Nordic comprehensive origin myth is provided by the ''

Prose Edda

The ''Prose Edda'', also known as the ''Younger Edda'', ''Snorri's Edda'' ( is, Snorra Edda) or, historically, simply as ''Edda'', is an Old Norse textbook written in Iceland during the early 13th century. The work is often assumed to have been ...

'' book ''

Gylfaginning

''Gylfaginning'' (Old Norse: 'The Beguiling of Gylfi' or 'The Deluding of Gylfi'; c. 20,000 words; 13th century Old Norse pronunciation ) is the first part of the 13th century ''Prose Edda'' after the Prologue. The ''Gylfaginning'' deals with t ...

''. According to ''Gylfaginning'', the first being was the giant

Ymir, who was followed by the cow

Auðumbla

In Norse mythology, Auðumbla �ɔuðˌumblɑ(also Auðhumla �ɔuðˌhumlɑ and Auðumla �ɔuðˌumlɑ ) is a primeval cow. The primordial frost jötunn Ymir fed from her milk, and over the course of three days she licked away the salty ri ...

, eventually leading to the birth of Odin and his two brothers. The brothers kill Ymir and make the world out of his body, before finally making the first man and woman out of trees (

Ask and Embla). Some scholars suspect that ''Gylfaginning'' had been compiled from various contradictory sources, with some details from those sources having been left out. Besides ''Gylfaginning'', the most important sources on Nordic creation myths are the

Eddic poems ''

Vǫluspá'', ''

Vafþrúðnismál

''Vafþrúðnismál'' ( Old Norse: "The Lay of Vafþrúðnir") is the third poem in the '' Poetic Edda''. It is a conversation in verse form conducted initially between the Æsir Odin and Frigg, and subsequently between Odin and the jötunn Vaf ...

'', and ''

Grímnismál''. The 9th-century Old High German

Wessobrunn Prayer begins with a series of negative pairs to describe the time before creation that show similarity to a number of Nordic descriptions of the time before the world, suggesting an orally transmitted formula.

There may be a continuity between Tacitus's account of Tuisto and Mannus and the ''Gylfaginning'' account of the creation of the world. The name ''Tuisto'', if it means 'twin' or 'double-being', could connect him to the name of the primordial being Ymir, whose name probably has a similar meaning. On the other hand, the form "Tuisco" may suggest a connection to

Tyr. Similarly, both myths have a genealogy consisting of a grandfather, a father, and then three sons. Ymir's name is etymologically connected to the Sanskrit

Yama

Yama (Devanagari: यम) or Yamarāja (यमराज), is a deity of death, dharma, the south direction, and the underworld who predominantly features in Hindu and Buddhist religion, belonging to an early stratum of Rigvedic Hindu deities. ...

and Iranian

Yima, while the creation of the world from Ymir's body is paralleled by the creation of the world from the primordial being

Purusha in Indic mythology, suggesting not only a Proto-Germanic origin for Ymir but an even older Indo-European origin (see

Indo-European cosmogony).

Myth of the end of the world

There is evidence of a myth of the

end of the world in Germanic mythology, which can be reconstructed in very general terms from the surviving sources. The best known is the myth of

Ragnarök

In Norse mythology, (; non, wikt:ragnarǫk, Ragnarǫk) is a series of events, including a great battle, foretelling the death of numerous great figures (including the Æsir, gods Odin, Thor, Týr, Freyr, Heimdallr, and Loki), natural disast ...

, attested from Old Norse sources, which involves a war between the gods and the beings of chaos, leading to the destruction of almost all gods, giants, and living things in a cataclysm of fire. It is followed by a rebirth of the world. The notion of the world's destruction by fire in the Southern Germanic area seems confirmed by the existence of the word (probably "

world conflagration") to refer to the end of the world in Old High German; however, it is possible that this aspect derives from Christian influence. Scholarship on Ragnarök tends to either argue that it is a myth with composite, partially non-Scandinavian origins, that it has Indo-European parallels and thus origins, or that it derives from Christian influence.

Physical cosmos

Information on Germanic cosmology is only provided in Nordic sources, but there is evidence for considerable continuity of beliefs despite variation over time and space. Scholarship is marked by disagreement about whether Snorri Sturlason's ''Edda'' is a reliable source for pre-Christian Norse cosmology, as Snorri has undoubtedly imposed an ordered, Christian worldview on his material.

Midgard ("dwelling place in the middle") is used to refer to the inhabited world or a barrier surrounding the inhabited world in Norse mythology. The term is first attested as in

Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

with

Wulfila's

translation of the bible (c. 370 CE), and has cognates in Saxon, Old English, and Old High German. It is thus probably an old Germanic designation. In the ''Prose Edda'', Midgard also seems to be the part of the world inhabited by the gods. The dwelling place of the gods themselves is known as

Asgard, while outside of Midgard, the giants dwell in lands sometimes referred to as

Jötunheimar. The ash tree

Yggdrasill is at the center of the world, and propped up the heavens in the same way as the Saxon pillar

Irminsul

An Irminsul (Old Saxon 'great pillar') was a sacred, pillar-like object attested as playing an important role in the Germanic paganism of the Saxons. Medieval sources describe how an Irminsul was destroyed by Charlemagne during the Saxon Wars. ...

was said to. The world of the dead (Hel) seems to have been underground, and it is possible that the realm of the gods was originally subterranean as well.

Fate

Some Christian authors of the Middle Ages, such as

Bede

Bede ( ; ang, Bǣda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom ...

(c. 700) and

Thietmar of Merseburg (c. 1000), attribute a strong belief in fate and chance to the followers of Germanic religion. Similarly, Old English, Old High German, and Old Saxon associate a word for fate, ''

wyrd'', as referring to an inescapable, impersonal fate or death. While scholarship of the early 20th century believed that this meant that Germanic religion was essentially fatalistic, scholars since 1969 have noted that this concept appears to have been heavily influenced by the Christianized Greco-Roman notion of ("fatal fortune") rather than reflecting Germanic belief. Nevertheless, Norse myth attests the belief that even the gods were subject to fate. While it is thus clear that older scholarship exaggerated the importance of fate in Germanic religion, it still had its own concept of fate. Most Norse texts dealing with fate are heroic, which probably influences their portrayal of fate.

In Norse myth, fate was created by supernatural female beings called

Norns

The Norns ( non, norn , plural: ) are deities in Norse mythology responsible for shaping the course of human destinies.'' Nordisk familjebok'' (1907)

In the '' Völuspá'', the three primary Norns Urðr (Wyrd), Verðandi, and Skuld draw w ...

, who appear either individually or as a collective and who give people their fate at birth and are somehow involved in their deaths. Other female beings, the

disir and

valkyries

In Norse mythology, a valkyrie ("chooser of the slain") is one of a host of female figures who guide souls of the dead to the god Odin's hall Valhalla. There, the deceased warriors become (Old Norse "single (or once) fighters"Orchard (1997:36) ...

, were also associated with fate.

Afterlife

Early Germanic beliefs about the afterlife are not well known, however, the sources indicate a variety of beliefs, including belief in an

underworld

The underworld, also known as the netherworld or hell, is the supernatural world of the dead in various religious traditions and myths, located below the world of the living. Chthonic is the technical adjective for things of the underwo ...

, continued life in the grave, a world of the dead in the sky, and reincarnation. Beliefs varied by time and place and may have contradictory in the same time and place. The two most important afterlives in the attested corpus were located at

Hel and

Valhalla

In Norse mythology Valhalla (;) is the anglicised name for non, Valhǫll ("hall of the slain").Orchard (1997:171–172) It is described as a majestic hall located in Asgard and presided over by the god Odin. Half of those who die in combat e ...

, while additional destinations for the dead are also mentioned. A number of sources refer to Hel as the general abode of the dead.

The Old Norse proper noun ''Hel'' and its cognates in other Germanic languages are used for the Christian

hell

In religion and folklore, hell is a location in the afterlife in which evil souls are subjected to punitive suffering, most often through torture, as eternal punishment after death. Religions with a linear divine history often depict hell ...

, but they originally refer to a Germanic underworld and/or afterlife location that predates Christianization. Its relation to the West Germanic verb ("to hide") suggests that it may have originally referred to the grave itself. It could also suggest the idea that the realm of the dead is hidden from human view. It was not conceived of as a place of punishment until the high Middle Ages, when it takes on some characteristics of the Christian hell. It is described as cold, dark, and in the north. Valhalla ("hall of the slain"), on the other hand, is a hall in Asgard where the illustrious dead dwell with Odin, feasting and fighting.

Old Norse material often include the notion that the dead lived in their graves, and that they can sometimes come back as

revenants

In folklore, a revenant is an animated corpse that is believed to have been revived from death to haunt the living. The word ''revenant'' is derived from the Old French word, ''revenant'', the "returning" (see also the related French verb ''re ...

. Several inscriptions in the

Elder Futhark

The Elder Futhark (or Fuþark), also known as the Older Futhark, Old Futhark, or Germanic Futhark, is the oldest form of the runic alphabets. It was a writing system used by Germanic peoples for Northwest Germanic dialects in the Migration Peri ...

found on stones marking graves seem intended to prevent this. The concept of the

Wild Hunt

The Wild Hunt is a folklore motif (Motif E501 in Stith Thompson's Motif-Index of Folk-Literature) that occurs in the folklore of various northern European cultures. Wild Hunts typically involve a chase led by a mythological figure escorted by ...

of the dead, first attested in the 11th century, is found throughout the Germanic-speaking regions.

Religiously significant numbers

In Germanic mythology, the numbers three, nine, and twelve play an important role. The symbolic importance of the number three is attested widely among many cultures, and the number twelve is also attested as significant in other cultures, meaning that foreign influence is possible. The number three often occurs as a symbol of completeness, which is probably how the frequent use in Germanic religion of triads of gods or giants should be understood. Groups of three gods are mentioned in a number of sources, including Adam of Bremen, the Nordendorf Fibula, the Old Saxon Baptismal Formula, ''Gylfaginning'', and ''Þorsteins þáttr uxafóts''. The number nine can be understand as three threes. Its importance is attested in both mythology and worship.

Supernatural and divine beings

Gods

The Germanic gods were a category of supernatural beings who interacted with humans, as well as with other supernatural beings such as giants (jötnar), elves, and dwarfs. The distinction between gods and other supernaturally powerful beings might not always be clear. Unlike the Christian god, the Germanic gods were born, can die, and are unable to change the fate of the world. The gods had mostly human features, with human forms, male or female gender, and familial relationships, and lived in a society organized like human society; however, their sight, hearing, and strength were superhuman, and they possessed a superhuman ability to influence the world. Within the religion, they functioned as helpers of humans, granting ("good luck, good fortune") for correct religious observance. The adjectival form (English ''holy'') is attested in all Germanic languages, including Gothic on the

Ring of Pietroassa

The Ring of Pietroassa or Buzău torc is a gold torc-like necklace found in a ring barrow in Pietroassa (now Pietroasele), Buzău County, southern Romania (formerly Wallachia), in 1837. It formed part of a large gold hoard (the Pietroasele treas ...

.

Based on Old Norse evidence, Germanic paganism probably had a variety of words to refer to gods. Words descended from Proto-Germanic *''ansuz'', the origin of the Old Norse family of gods known as the

Aesir (singular Áss), are attested as a name for divine beings from around the Germanic world. The earliest attestations are the name of a war goddess ("

battle goddess") that appears on a Roman inscription from

Tongeren

Tongeren (; french: Tongres ; german: Tongern ; li, Tóngere ) is a city and municipality located in the Belgian province of Limburg, in the southeastern corner of the Flemish region of Belgium. Tongeren is the oldest town in Belgium, as the ...

and a Runic belt-buckle found at

Vimose

Finds from Vimose (), on the island of Funen, Denmark, include some of the oldest datable Elder Futhark runic inscriptions in early Proto-Norse or late Proto-Germanic from the 2nd to 3rd century in the Scandinavian Iron Age and were written in ...

, Denmark from around 200 CE. The historian Jordanes mentions the Latinized form in the ''Getica'', while the Old English rune poem attests the Old English form , and personal names also exist using the word from the area where Old High German was spoken. The Indo-European word for god, ''*deiuos'', is only found in Old Norse, where it occurs as ; it mostly appears in the plural () or in compound

bynames.

In Norse mythology, the Aesir is one of two families of gods, the other being the

Vanir

In Norse mythology, the Vanir (; Old Norse: , singular Vanr ) are a group of gods associated with fertility, wisdom, and the ability to see the future. The Vanir are one of two groups of gods (the other being the Æsir) and are the namesake of the ...

: the most important gods of Norse mythology belong to the Aesir and the term can also be used for the gods in general. The Vanir appear to have been mostly

fertility gods. There is no evidence for the existence of a separate Vanir family of gods outside of Icelandic mythological texts, namely the Eddic poem ''

Vǫluspá'' and Snorri Sturluson's

Prose Edda

The ''Prose Edda'', also known as the ''Younger Edda'', ''Snorri's Edda'' ( is, Snorra Edda) or, historically, simply as ''Edda'', is an Old Norse textbook written in Iceland during the early 13th century. The work is often assumed to have been ...

and

Ynglinga Saga

''Ynglinga saga'' ( ) is a Kings' saga, originally written in Old Norse by the Icelandic poet and historian Snorri Sturluson about 1225. It is the first section of his '' Heimskringla''. It was first translated into English and published in 1 ...

. These sources detail a mythical

Æsir–Vanir War, which, however, is portrayed quite differently in the different accounts.

Giants (Jötnar)

Giants (Jötnar) play a significant role in Germanic myth as preserved in Iceland, being just as important as the gods in myths of the cosmology and the creation and the end of the world. They appear to have been various types of powerful, non-divine supernatural beings who lived in a kind of wilderness and were mostly hostile to humans and gods. They have human form and live in families, but can sometimes take on animal form. In addition to non, jötnar, the beings are also commonly referred to as , both terms having cognates in West Germanic; is probably derived from the verb "to eat", either referring to their strength, or possibly to cannibalism as a characteristic trait of giants. Giants often have a special association with some phenomena of nature, such as frost, mountains, water, and fire. Scholars are divided as to whether there were any religious offerings or rituals offered to giants in Germanic religion. Scholars such as Gro Steisland and Nanna Løkka have suggested that the division of the gods from giants is not actually very clear.

Elves, dwarfs and other beings

Germanic religion also contained various other mythological beings, such as the monstrous wolf

Fenrir, as well as beings such as

elves

An elf () is a type of humanoid supernatural being in Germanic mythology and folklore. Elves appear especially in North Germanic mythology. They are subsequently mentioned in Snorri Sturluson's Icelandic Prose Edda. He distinguishes ...

,

dwarfs, and other non-divine supernatural beings.

Elves are beings of Germanic

lower mythology

Lower mythology is a sphere of mythological representations relating to characters who have no divine status, demons and spirits, as opposed to higher gods and the official cult. This opposition is particularly pronounced in world religions.'' I ...

that are mostly male and appear as a collective. Snorri Sturluson divides the elves into two groups, the dark elves and the light elves; however, this division is not attested elsewhere. People's understanding of elves varied by time and place: in some instances they were godlike beings, in others dead ancestors, nature spirits, or demons. In Norse pagan belief, elves seem to have been worshiped to some extent. The concept of elves begins to differ between Scandinavia and the West Germanic peoples in the Middle Ages, possibly under Celtic influence. In Anglo-Saxon England, elves seem to have been potentially dangerous, powerful supernatural beings associated with woods, fields, hills, and bodies of water.

Like elves, dwarfs are beings of Germanic lower mythology. They are mostly male and imagined as a collective; however, individual named dwarfs also play an important role in Norse mythology. In Norse and German texts, dwarfs live in mountains and are known as great smiths and craftsmen. They may have originally been nature spirits or demons of death. Snorri Sturluson equates the dwarfs to a subgroup of the elves, and many high medieval German epics and some Old Norse myths give dwarfs names with the word or ("elf") in them, suggesting some confusion between the two. However, there is no evidence that the dwarfs were worshiped. In Anglo-Saxon England, dwarfs were potentially dangerous supernatural beings associated with madness, fever, and dementia, and have no known association with mountains.

Dragon

A dragon is a reptilian legendary creature that appears in the folklore of many cultures worldwide. Beliefs about dragons vary considerably through regions, but dragons in western cultures since the High Middle Ages have often been depicted a ...

s occur in Germanic mythology, with Norse examples including

Níðhöggr

In Norse mythology, Níðhöggr (''Malice Striker'', in Old Norse traditionally also spelled Níðhǫggr , often anglicized NidhoggWhile the suffix of the name, ''-höggr'', clearly means "striker" the prefix is not as clear. In particular, the ...

and the world-serpent

Jörmungandr. It is difficult to tell how much existing sources have been influenced by Greco-Roman and Christian ideas about dragons. Based on the native word ( goh, lintwurm, related to non, linnr, "snake"), the early description in ''

Beowulf

''Beowulf'' (; ang, Bēowulf ) is an Old English epic poem in the tradition of Germanic heroic legend consisting of 3,182 alliterative lines. It is one of the most important and most often translated works of Old English literature. ...

'', and early pictorial depictions, they were probably imagined as snake-like and of large size, able to spit poison or fire, and dwelled under the earth. Some dragons are described as crawling, while others are said to be able to fly.

Pantheon

Due to the scarcity of sources and the origin of the Germanic gods over a broad period of time and in different locations, it is not possible to reconstruct a full pantheon of Germanic deities that is valid for Germanic religion everywhere; this is only possible for the last stage of Germanic religion, Norse paganism. People in different times and places would have worshiped different individual gods and groups of gods. Placename evidence containing divine names gives some indication of which gods were important in particular regions, however, such names are not well attested or researched outside Scandinavia.

The following section first includes some information on the gods attested during the Roman period, then the four main Germanic gods *Tiwaz (Tyr), Thunraz (Thor), *Wodanaz (Odin), and Frijjō (Frigg), who are securely attested since the early Middle Ages but were probably worshiped during Roman times, and finally some information on other gods, many of whom are only attested in Norse paganism.

Roman-era

Germanic gods with Roman names

The Roman authors Julius Caesar and Tacitus both use Roman names to describe foreign gods, but whereas Caesar claims the Germani worshiped no individual gods but only natural phenomena such as the sun, moon, and fire, Tacitus mentions a number of deities, saying that the most worshiped god is

Mercury, followed by

Hercules

Hercules (, ) is the Roman equivalent of the Greek divine hero Heracles, son of Jupiter and the mortal Alcmena. In classical mythology, Hercules is famous for his strength and for his numerous far-ranging adventures.

The Romans adapted the ...

, and

Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin at ...

; he also mentions

Isis

Isis (; ''Ēse''; ; Meroitic: ''Wos'' 'a''or ''Wusa''; Phoenician: 𐤀𐤎, romanized: ʾs) was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kin ...

,

Odysseus

Odysseus ( ; grc-gre, Ὀδυσσεύς, Ὀδυσεύς, OdysseúsOdyseús, ), also known by the Latin variant Ulysses ( , ; lat, UlyssesUlixes), is a legendary Greek king of Ithaca and the hero of Homer's epic poem the ''Odyssey''. Odys ...

, and

Laertes. Scholars generally interpret Mercury as meaning Odin, Herculus as meaning Thor, and Mars as meaning Tyr. As these names are only attested much later, however, there is some doubt about these identifications and it has been suggested that the gods Tacitus names were not worshiped by all Germanic peoples or that he has transferred information about the

Gauls

The Gauls ( la, Galli; grc, Γαλάται, ''Galátai'') were a group of Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age and the Roman period (roughly 5th century BC to 5th century AD). Their homeland was known as Gaul (''Gallia''). They sp ...

to the Germans.

The Germani themselves also worshiped gods with Roman names at votive altars constructed according to Roman tradition; while isolated instances of Germanic bynames (such as "Mars Thingsus") indicate that a Germanic god was meant, often it is not possible to know if the Roman god or a Germanic equivalent is meant. Most surviving dedications are to Mercury. Female deities, on the other hand, were not given Roman names. Additionally, the Germanic speakers also translated Roman gods' names into their own languages () most prominently in the Germanic

days of the week

A day is the time period of a full rotation of the Earth with respect to the Sun. On average, this is 24 hours, 1440 minutes, or 86,400 seconds. In everyday life, the word "day" often refers to a solar day, which is the length between two ...

. Usually the translation of the days of the week is dated to the 3rd or 4th century CE; however, they are not attested until the early Middle Ages. This late attestation causes some scholars to question the usefulness of the days of the week for reconstructing early Germanic religion.

Alcis

Tacitus mentions a divine pair of twins called the

Alcis worshipped by the

Naharvali, whom he compares to the Roman twin horsemen

Castor and Pollux. These twins can be associated with the Indo-European myth of the

divine twin horsemen (Dioscuri) attested in various Indo-European cultures. Among later Germanic peoples, twin founding figures such as

Hengist and Horsa allude to the motif of the divine twins; Hengist and Horsa's names both mean "horse", strengthening the connection. In Scandinavia, images of divine twins are attested from 15th century BCE until the 8th century CE, after which they disappear, apparently as a result of religious change. Norse texts contain no identifiable divine twins, though scholars have looked for parallels among gods and heroes.

Nerthus

In ''Germania'', Tacitus mentions that the

Lombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 an ...

and

Suebi

The Suebi (or Suebians, also spelled Suevi, Suavi) were a large group of Germanic peoples originally from the Elbe river region in what is now Germany and the Czech Republic. In the early Roman era they included many peoples with their own name ...

venerated a particular deity,

Nerthus. He describes this wagon procession in some detail: Nerthus's cart is found on an unspecified island in the "ocean", where it is kept in a

sacred grove

Sacred groves or sacred woods are groves of trees and have special religious importance within a particular culture. Sacred groves feature in various cultures throughout the world. They were important features of the mythological landscape and ...

and draped in white cloth. Only a priest may touch it. When the priest detects Nerthus's presence by the cart, the cart is drawn by

heifers. Nerthus's cart is met with celebration and peacetime everywhere it goes, and during her procession no one goes to war and all iron objects are locked away. In time, after the goddess has had her fill of human company, the priest returns the cart to her "temple" and slaves ritually wash the goddess, her cart, and the cloth in a "secluded lake". According to Tacitus, the slaves are then immediately drowned in the lake.

The majority of modern scholars identify Nerthus as a direct etymological precursor to the Old Norse deity

Njörðr, attested over a thousand years later. However, Njörðr is attested as male, leading to many proposals regarding this apparent change, such as incest motifs described among the Vanir, a group of gods to which Njörðr belongs, in Old Norse sources.

Matronae

Collectives of three goddess known as

matronae

The Matres (Latin for "mothers") and Matronae (Latin for "matrons") were female deities venerated in Northwestern Europe, of whom relics are found dating from the first to the fifth century AD. They are depicted on votive offerings and altars th ...

appear on numerous votive altars from the Roman province of

Germania inferior, especially from Cologne, dating to the third and fourth centuries CE. The altars depict three women in non-Roman dress. About half of serving matronae altars can be identified as Germanic because of their

bynames; other have Latin or Celtic bynames. The bynames are often connected to a place or ethnic group, but a number are associated with water, and many of them seem to indicate a giving and protecting nature. Despite their frequency in the archaeological record, the matronae receive no mention in any written source.

The matronae may be connected to female deities attested in collectives from later times, such as the

Norns

The Norns ( non, norn , plural: ) are deities in Norse mythology responsible for shaping the course of human destinies.'' Nordisk familjebok'' (1907)

In the '' Völuspá'', the three primary Norns Urðr (Wyrd), Verðandi, and Skuld draw w ...

, the

disir and

valkyries

In Norse mythology, a valkyrie ("chooser of the slain") is one of a host of female figures who guide souls of the dead to the god Odin's hall Valhalla. There, the deceased warriors become (Old Norse "single (or once) fighters"Orchard (1997:36) ...

;

Rudolf Simek

Rudolf Simek (born 21 February 1954) is an Austrian philologist and religious studies scholar who is Professor and Chair of Ancient German and Nordic Studies at the University of Bonn. Simek specializes in Germanic studies, and is the author o ...

suggests that a connection to the disir is most likely. The disir may be etymologically connected to minor Hindu deities known as

dhisanās, who likewise appear in a group; this would give them an Indo-European origin. Since

Jacob Grimm

Jacob Ludwig Karl Grimm (4 January 1785 – 20 September 1863), also known as Ludwig Karl, was a German author, linguist, philologist, jurist, and folklorist. He is known as the discoverer of Grimm's law of linguistics, the co-author of t ...

, scholars have sought to connect the disir with the found in the Old High German

First Merseburg Charm and with a conjecturally corrected place name from Tacitus; however, these connections are contested. The disir share some functions with the Norns and valkyries, and the Nordic sources suggest a close association between the three groups of Norse minor female deities. Further connections of the matronae have been proposed: the Anglo-Saxon pagan festival of ("

night of the mothers") mentioned by Bede has been associated with the matronae. Likewise, the poorly attested Anglo-Saxon goddesses

Eostre and

Rheda may be connected with the matronae.

Other female deities

Besides Nerthus, Tacitus elsewhere mentions other important female deities worshiped by the Germanic peoples, such as

Tamfana In Germanic paganism, Tamfana is a goddess. The destruction of a temple dedicated to the goddess is recorded by Roman senator Tacitus to have occurred during a massacre of the Germanic Marsi by forces led by Roman general Germanicus. Scholars have a ...

by the

Marsi

The Marsi were an Italic people of ancient Italy, whose chief centre was Marruvium, on the eastern shore of Lake Fucinus (which was drained for agricultural land in the late 19th century). The area in which they lived is now called Marsica. D ...

(''Annals'', 1:50) and the "mother of the gods" () by the

Aestii

The Aesti (also Aestii, Astui or Aests) were an ancient people first described by the Roman historian Tacitus in his treatise ''Germania'' (circa 98 AD). According to Tacitus, the land of ''Aesti'' was located somewhere east of the ''Suiones'' (p ...

(''Germania'', chapter 45).

In addition to the collective , votive altars from Roman Germania attest a number of individual goddesses. A goddess

Nehelenia

Nehalennia (spelled variously) is a goddess of unclear origin, perhaps Germanic or Celtic. She is attested on and depicted upon numerous votive altars discovered around what is now the province of Zeeland, the Netherlands, where the Schelde Ri ...

is attested on numerous votive altars from the 3rd century CE on the Rhine islands of Walcheren and Noord-Beveland, as well as at Cologne. Dedicatory inscriptions to Nehelenia make up 15% of all extant dedications to gods from the Roman province

Germania inferior and 50% of dedications to female deities. She appears to have been associated with trade and commerce, and was possibly a

chthonic

The word chthonic (), or chthonian, is derived from the Ancient Greek word ''χθών, "khthon"'', meaning earth or soil. It translates more directly from χθόνιος or "in, under, or beneath the earth" which can be differentiated from Γῆ ...

deity: she is usually depicted with baskets of fruit, a dog, or the prow of a ship or an oar. Her attributes are shared with the Hellenistic-Egyptian goddess

Isis

Isis (; ''Ēse''; ; Meroitic: ''Wos'' 'a''or ''Wusa''; Phoenician: 𐤀𐤎, romanized: ʾs) was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kin ...

, suggesting a connection to the

Isis of the Suebi

Isis (; ''Ēse''; ; Meroitic: ''Wos'' 'a''or ''Wusa''; Phoenician: 𐤀𐤎, romanized: ʾs) was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kingdo ...

mentioned by Tacitus. Despite her obvious importance, she is not attested in later periods.

Another goddess,

Hludana Hludana (or Dea Hludana) is a Germanic goddess attested in five ancient Latin inscriptions from the Rhineland and Frisia, all dating from 197–235 AD.

Three of these inscriptions come from the lower Rhine (; ; ), one from Münstereifel () and o ...

, is also attested from five votive inscriptions along the Rhine; her name is cognate with Old Norse Hlóðyn, one of the names of

Jörð (earth), the mother of Thor. It has thus been suggested she may have been a chthonic deity, possibly also connected to later attested figures such as

Hel,

Huld and

Frau Holle

"Frau Holle" ( ; also known as "Mother Holle", "Mother Hulda" or "Old Mother Frost") is a German fairy tale collected by the Brothers Grimm in ''Children's and Household Tales'' in 1812 (KHM 24). It is of Aarne-Thompson type 480.

Frau Holle (als ...

.

Post-Roman era

*Tiwaz/Tyr

The god *Tiwaz (

Tyr) may be attested as early as 450-350 BCE on the

Negau helmet

The Negau helmets are 26 bronze helmets (23 of which are preserved) dating to c. 450 BC–350 BC, found in 1812 in a cache in Ženjak, near Negau, Duchy of Styria (now Negova, Slovenia). The helmets are of typical Etruscan ' vetulonic' shape, ...

. Etymologically, his name is related to the Vedic

Dyaus

Dyaus ( ), or Dyauspitar (Devanagari द्यौष्पितृ, ), is the Ṛigvedic sky deity. His consort is Prithvi, the earth goddess, and together they are the archetypal parents in the Rigveda.

Nomenclature

stems from Proto-Indo ...

and Greek

Zeus

Zeus or , , ; grc, Δῐός, ''Diós'', label= genitive Boeotian Aeolic and Laconian grc-dor, Δεύς, Deús ; grc, Δέος, ''Déos'', label= genitive el, Δίας, ''Días'' () is the sky and thunder god in ancient Greek relig ...

, indicating an origin in the reconstructed Indo-European sky deity *

Dyēus

''*Dyḗus'' ( lit. "daylight-sky-god"), also ''*Dyḗus ph₂tḗr'' (lit. "father daylight-sky-god"), is the reconstructed name of the daylight-sky god in Proto-Indo-European mythology. ''*Dyēus'' was conceived as a divine personification of ...

. He is thus the only attested Germanic god who was already important in Indo-European times. When the days of the week were translated into Germanic, Tyr was associated with the Roman god

Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin at ...

, so that (day of Mars) became "Tuesday" ("day of *Tiwaz/Tyr"). A votive inscription to "Mars Thingsus" (Mars of the

thing) suggests he also had a connection to the legal sphere.

Scholars generally believe that Tyr became less and less important in the Scandinavian branch of Germanic paganism over time and had largely ceased to be worshiped by the Viking Age. He plays a major role in only one myth, the binding of the monstrous wolf

Fenrir, during which Tyr loses his hand.

*Thunraz/Thor

Thor was the most widely known and perhaps the most widely worshiped god in

Viking Age

The Viking Age () was the period during the Middle Ages when Norsemen known as Vikings undertook large-scale raiding, colonizing, conquest, and trading throughout Europe and reached North America. It followed the Migration Period and the Germ ...

Scandinavia. When the days of the week were translated into Germanic, he was associated with

Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but slightly less than one-thousand ...

, so that ("Day of Jupiter") becomes "Thursday"

day of Thunraz/Thor". This contradicts the earlier , where Thor is generally thought to be Hercules. Textual sources such as

Adam of Bremen

Adam of Bremen ( la, Adamus Bremensis; german: Adam von Bremen) (before 1050 – 12 October 1081/1085) was a German medieval chronicler. He lived and worked in the second half of the eleventh century. Adam is most famous for his chronicle ''Gest ...

as well as the association with Jupiter in the suggest he may have been the head of the pantheon, at least in some times and places. Alternatively, Thor's hammer may have been equated with Jupiter's lightning bolt. Outside of Scandinavia, he appears on the

Nordendorf fibulae (6th or 7th century CE) and in the

Old Saxon Baptismal Vow (9th century CE). The

Oak of Jupiter, destroyed by

Saint Boniface

Boniface, OSB ( la, Bonifatius; 675 – 5 June 754) was an English Benedictine monk and leading figure in the Anglo-Saxon mission to the Germanic parts of the Frankish Empire during the eighth century. He organised significant foundations o ...

among the

Chatti

The Chatti (also Chatthi or Catti) were an ancient Germanic tribe

whose homeland was near the upper Weser (''Visurgis''). They lived in central and northern Hesse and southern Lower Saxony, along the upper reaches of that river and in the val ...

in 723 CE, is also usually presumed to have been dedicated to Thor.

Viking age runestones as well as the Nordendorf fibulae appear to call upon Thor to bless objects. The most important archaeological evidence for the worship of Thor in Viking Age Scandinavia is found in the form of

Thor's hammer

Thor (; from non, Þórr ) is a prominent god in Germanic paganism. In Norse mythology, he is a hammer-wielding god associated with lightning, thunder, storms, sacred groves and trees, strength, the protection of humankind, hallowing, and ...

pendants. Myths about Thor are only attested from Scandinavia, and it is unclear how representative the Nordic corpus is for the entire Germanic region. As Thor's name means "thunder", scholars since

Jacob Grimm

Jacob Ludwig Karl Grimm (4 January 1785 – 20 September 1863), also known as Ludwig Karl, was a German author, linguist, philologist, jurist, and folklorist. He is known as the discoverer of Grimm's law of linguistics, the co-author of t ...

have interpreted him to be a sky and weather god. In Norse mythology, he shares features with other Indo-European thunder gods, including his slaying of monsters; these features likely derive from a common Indo-European source. In the extant mythology of Thor, however, he has very little association with thunder.

*Wodanaz/Odin

Odin (*Wodanaz) plays the main role in a number of myths as well as well-attested Norse rituals; he appears to have been venerated by many Germanic peoples in the early Middle Ages, though his exact characteristics probably varied in different times and places. In the Germanic days of the week, Odin is equated with

Mercury (

ay of Mercury

Ay, AY or variants, may refer to:

People

* Ay (pharaoh), a pharaoh of the 18th Egyptian dynasty

* Merneferre Ay, a pharaoh of the 13th Egyptian dynasty

* A.Y. (musician) (born 1981), a Tanzanian "bongo flava" artist

* A.Y, stage name of Ayo Mak ...

which became "Wednesday"

day of *Wodanaz/Odin", an association that accords with the usual scholarly interpretation of the and is also found in early medieval authors. It may have been inspired by both gods' connections to arcane knowledge and the dead.

The age of the cult of Odin is disputed. Archaeological evidence for Odin is found in the form of his later

bynames on Runic inscriptions found in Danish bogs from 4th or 5th century AD; other possible archaeological attestations may date to the 3rd century CE. Images of Odin dating to the late migration period are known from

Frisia

Frisia is a cross-border cultural region in Northwestern Europe. Stretching along the Wadden Sea, it encompasses the north of the Netherlands and parts of northwestern Germany. The region is traditionally inhabited by the Frisians, a West G ...

, but appear to have come there from Scandinavia. The earliest textual reference to Odin by name may be in

Jonas of Bobbio's ''Life of Saint Columbanus'' from the 640s.

In Norse myths, Odin plays one of the most important roles of all the gods. He is also attested in myths outside of the Norse area. In the mid-7th century CE, the Franco-Burgundian chronicler

Fredegar narrates that "Wodan" gave the

Lombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 an ...

their name; this story also appears in the roughly contemporary ''

Origo gentis Langobardorum'' and later in the ''

Historia Langobardorum

The ''History of the Lombards'' or the ''History of the Langobards'' ( la, Historia Langobardorum) is the chief work by Paul the Deacon, written in the late 8th century. This incomplete history in six books was written after 787 and at any rate ...

'' of

Paul the Deacon

Paul the Deacon ( 720s 13 April in 796, 797, 798, or 799 AD), also known as ''Paulus Diaconus'', ''Warnefridus'', ''Barnefridus'', or ''Winfridus'', and sometimes suffixed ''Cassinensis'' (''i.e.'' "of Monte Cassino"), was a Benedictine monk, ...

(790 CE). In Germany, Odin is attested as part of a divine triad on the Nordendorf fibulae and the second Merseburg charm, in which he heals Balder's horse. In England, he appears as a healing magician in the

Nine Herbs Charm and in

Anglo-Saxon genealogies. It is disputed whether he was worshiped among the Goths.

*Frijjō/Frigg

The only major Norse goddess also found in the pre-Viking period is

Frigg, Odin's wife. When the Germanic days of the week were translated, Frigg was equated with

Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never f ...

, so that ("day of Venus") became "Friday" ("day of Frijjō/Frigg"). This translation suggests a connection to fertility and sexuality, and her name is etymologically derived from an Indo-European root meaning "love". In the stories of how the Lombard's got their name, Frea (Frigg) plays an important role in tricking her husband Vodan (Odin) into giving the Lombards victory. She is also mentioned in the Merseburg Charms, where she displays magical abilities. The only Norse myth in which Frigg plays a major role is the death of Baldr, and there is only little evidence for a cult of Frigg in Scandinavia.

Other gods

The god

Baldr

Baldr (also Balder, Baldur) is a god in Germanic mythology. In Norse mythology, Baldr (Old Norse: ) is a son of the god Odin and the goddess Frigg, and has numerous brothers, such as Thor and Váli. In wider Germanic mythology, the god was ...

is attested from Scandinavia, England, and Germany; except for the Old High German

Second Merseburg Charm

The Merseburg charms or Merseburg incantations (german: die Merseburger Zaubersprüche) are two medieval magic spells, charms or incantations, written in Old High German. They are the only known examples of Germanic pagan belief preserved in t ...

(9th century CE), all literary references to the god are from Scandinavia and nothing is known of his worship.

The god

Freyr was the most important fertility god of the Viking Age. He is sometimes known as Yngvi-Freyr, which would associate him with the god or hero *''Ingwaz'', the presumed progenitor of the

Inguaeones found in Tacitus's ''Germania'', whose name is attested in the

Old English rune poem (8th or 9th century CE) as Ing. A minor god named

Forseti is attested in a few Old Norse sources; he is generally associated with the Frisian god Fosite who was worshiped on

Helgoland, but this connection is uncertain. The Old Saxon Baptismal Formula and some Old English genealogies mention a god

Saxnot, who appears to be the founder of the

Saxons

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

; some scholars identify him as a form of Tyr, while others propose that he may be a form of Freyr.

The most important goddess in the recorded Old Norse pantheon was Freyr's sister,

Freyja

In Norse paganism, Freyja (Old Norse "(the) Lady") is a goddess associated with love, beauty, fertility, sex, war, gold, and seiðr (magic for seeing and influencing the future). Freyja is the owner of the necklace Brísingamen, rides a chario ...

, who features in more myths and appears to have been worshiped more than Frigg, Odin's wife. She was associated with sexuality and fertility, as well as war, death, and magic. It is unclear how old the worship of Freyja is, and there is no indisputable evidence for her or any of the vanir gods in the southern Germanic area. There is considerable debate about

whether Frigg and Freyja were originally the same goddess or aspects of the same goddess.

Besides Freyja, many gods and goddesses are only known from Scandinavia, including

Ægir,

Höðr,

Hönir,

Heimdall,

Idunn,

Loki

Loki is a god in Norse mythology. According to some sources, Loki is the son of Fárbauti (a jötunn) and Laufey (mentioned as a goddess), and the brother of Helblindi and Býleistr. Loki is married to Sigyn and they have two sons, Narfi ...

,

Njörðr,

Sif, and

Ullr

In Norse mythology, Ullr (Old Norse: ) is a god associated with archery. Although literary attestations of Ullr are sparse, evidence including relatively ancient place-name evidence from Scandinavia suggests that he was a major god in earlier ...

. There are a number of minor or regional gods mentioned in various medieval Norse sources: in some cases, it is unclear whether or not they are post-conversion literary creations. Many regional or highly local gods and spirits are probably not mentioned in the sources at all. It is also likely that many Roman-era and continental Germanic gods do not appear in Norse mythology.

Places and objects of worship

Divine images

Julius Caesar and Tacitus claimed that the Germani did not venerate their gods in human form; however, this is a

topos of ancient ethnography when describing supposedly primitive people. Archaeologists have found Germanic statues that appear to depict gods, and Tacitus appears to contradict himself when discussing the cult of Nerthus (''Germania'' chapter 40); the Eddic poem Hávamál also mentions wooden statues of gods, while Gregory of Tours (''Historia Francorum'' II: 29) mentions wooden statues and ones made of stone and metal. Archaeologists have not found any divine statues dating from after the end of the migration period; it is likely that they were destroyed during Christianization, as is repeatedly depicted in the Norse sagas.

Roughly carved wooden male and female figures that may depict gods are frequent finds in

bog

A bog or bogland is a wetland that accumulates peat as a deposit of dead plant materials often mosses, typically sphagnum moss. It is one of the four main types of wetlands. Other names for bogs include mire, mosses, quagmire, and muskeg; a ...

s; these figures generally follow the natural form of a branch. It is unclear whether the figures themselves were sacrifices or if they were the beings to whom the sacrifice was given. Most date from the first several centuries CE. For the pre-Roman iron age, board-like statues that were set up in dangerous places encountered in everyday life are also attested. Most statues were made out of oak wood. Small animal figurines of cattle and horses are also found in bogs; some may have been worn as amulets while others seem to have been placed by hearths before they were sacrificed.

Holy sites from the migration period frequently contain gold

bracteates and gold foil figures that depict obviously divine figures. The bracteates are originally based on motifs found on Roman gold medallions and coins of the era of

Constantine the Great

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterran ...

, but have become highly stylized. A few them have runic inscriptions that may be names of Odin. Others, such as Trollhätten-A, may display scenes known from later mythological texts.

The stone altars of the matronae and Nehalennia show women in Germanic dress, but otherwise follow Roman models, while images of Mercury, Hercules, or Mars do not show any difference from Roman models. Many bronze and silver statues of Roman gods have been found throughout Germania, some made by the ''Germani'' themselves, suggesting an appropriation of these figures by the ''Germani''. Heiko Steuer suggests that these statues likely were reinterpreted as local, Germanic gods and used on home altars: a find from

Odense dating c. 100-300 CE includes statues of Mercury, Mars, Jupiter, and Apollo. Imported Roman swords, found from Scandinavia to the Black Sea, frequently depicted the Roman god

Mars Ultor ("Mars the Avenger").

Sacred places