German occupation of Belgium during World War II on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The German occupation of Belgium (french: link=no, Occupation allemande, nl, Duitse bezetting) during

The German occupation of Belgium (french: link=no, Occupation allemande, nl, Duitse bezetting) during

Belgium had pursued a policy of neutrality since its independence in 1830, successfully avoiding becoming a belligerent in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71). In

Belgium had pursued a policy of neutrality since its independence in 1830, successfully avoiding becoming a belligerent in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71). In

Before leaving the country in 1940, the Belgian government had installed a panel of senior civil-servants, the so-called "

Before leaving the country in 1940, the Belgian government had installed a panel of senior civil-servants, the so-called "

Leopold III became

Leopold III became  Leopold was keen to find an accommodation with Germany in 1940, hoping that Belgium would remain as a unified and semi-autonomous state within a German-dominated Europe. As part of this plan, in November 1940, Leopold visited

Leopold was keen to find an accommodation with Germany in 1940, hoping that Belgium would remain as a unified and semi-autonomous state within a German-dominated Europe. As part of this plan, in November 1940, Leopold visited  For the rest of the war, Leopold was held under house-arrest in the

For the rest of the war, Leopold was held under house-arrest in the

Living standards in occupied Belgium decreased significantly from pre-war levels. Wages stagnated, while the occupying authorities tripled the amount of money in circulation, leading to rampant

Living standards in occupied Belgium decreased significantly from pre-war levels. Wages stagnated, while the occupying authorities tripled the amount of money in circulation, leading to rampant

Factories, ports and other strategic sites used by the German war effort were frequent targets of Allied bombers from both the British

Factories, ports and other strategic sites used by the German war effort were frequent targets of Allied bombers from both the British

Before 1941, Belgian workers could volunteer to work in Germany; nearly 180,000 Belgians signed up, hoping for better pay and living conditions. About 3,000 Belgians joined the (OT), and 4,000 more joined the paramilitary German supply corps, the (NSKK). The numbers, however, proved insufficient. Despite the protestation of the Secretaries-General, compulsory deportation of Belgian workers to Germany began in October 1942. At the beginning of the scheme, Belgian firms were obliged to select 10 percent of their work force, but from 1943 workers were conscripted by age class. 145,000 Belgians were conscripted and sent to Germany, most to work in manual jobs in industry or agriculture for the German war effort. Working conditions for forced workers in Germany were notoriously poor. Workers were paid little and worked long hours, and those in German towns were particularly vulnerable to Allied aerial bombing.

Following the introduction of compulsory deportation 200,000 Belgian workers (dubbed or ) went into hiding for fear of being conscripted. The were often aided by resistance organisations, such as Organisation Socrates run by the , who provided food and false papers. Many went on to enlist in resistance groups, swelling their numbers enormously from late 1942.

Before 1941, Belgian workers could volunteer to work in Germany; nearly 180,000 Belgians signed up, hoping for better pay and living conditions. About 3,000 Belgians joined the (OT), and 4,000 more joined the paramilitary German supply corps, the (NSKK). The numbers, however, proved insufficient. Despite the protestation of the Secretaries-General, compulsory deportation of Belgian workers to Germany began in October 1942. At the beginning of the scheme, Belgian firms were obliged to select 10 percent of their work force, but from 1943 workers were conscripted by age class. 145,000 Belgians were conscripted and sent to Germany, most to work in manual jobs in industry or agriculture for the German war effort. Working conditions for forced workers in Germany were notoriously poor. Workers were paid little and worked long hours, and those in German towns were particularly vulnerable to Allied aerial bombing.

Following the introduction of compulsory deportation 200,000 Belgian workers (dubbed or ) went into hiding for fear of being conscripted. The were often aided by resistance organisations, such as Organisation Socrates run by the , who provided food and false papers. Many went on to enlist in resistance groups, swelling their numbers enormously from late 1942.

In the first year of the occupation, the German administration pursued a conciliatory policy toward the Belgian people in order to gain their support and co-operation. This policy was, in part, because there was little resistance activity and because the demands the Germans needed to place on Belgian civilians and businesses were relatively small on account of their military success. During the fighting in Belgium, however, there were incidents of massacres against Belgian civilians by German forces, notably the Vinkt Massacre in which 86 civilians were killed.

From 1941, the regime became significantly more repressive. This was partly a result of the increasing demands on the German economy created by the

In the first year of the occupation, the German administration pursued a conciliatory policy toward the Belgian people in order to gain their support and co-operation. This policy was, in part, because there was little resistance activity and because the demands the Germans needed to place on Belgian civilians and businesses were relatively small on account of their military success. During the fighting in Belgium, however, there were incidents of massacres against Belgian civilians by German forces, notably the Vinkt Massacre in which 86 civilians were killed.

From 1941, the regime became significantly more repressive. This was partly a result of the increasing demands on the German economy created by the

Shortly after the invasion of Belgium, the Military Government passed a series of anti-Jewish laws (similar to the

Shortly after the invasion of Belgium, the Military Government passed a series of anti-Jewish laws (similar to the

Many important politicians who had opposed the Nazis before the war were arrested and deported to concentration camps in Germany and German-occupied Poland, as part of the (literally "Night and Fog") decree. Among them was the 71-year-old

Many important politicians who had opposed the Nazis before the war were arrested and deported to concentration camps in Germany and German-occupied Poland, as part of the (literally "Night and Fog") decree. Among them was the 71-year-old

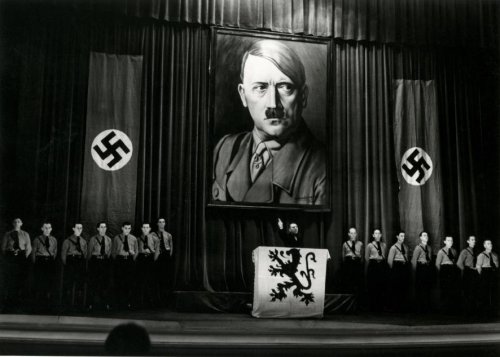

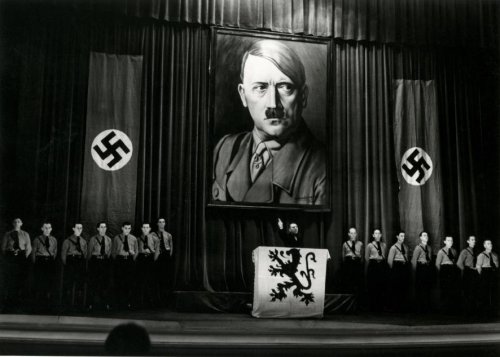

Before the war, several Fascist movements had existed in Flanders. The two major pre-war

Before the war, several Fascist movements had existed in Flanders. The two major pre-war

As a result of the , was not given the same favoured status accorded to Flemish Fascists. Nevertheless, it was permitted to republish its newspaper and re-establish and expand its paramilitary wing, the , which had been banned before the war. In April 1943, declared itself part of the SS. The were responsible for numerous attacks against Jews and, from 1944, also participated in arbitrary reprisals against civilians for attacks by the resistance. In 1944, Rexist paramilitaries massacred 20 civilians in the village of Courcelles in retaliation for an assassination of a Rexist politician by members of the resistance.

As a result of the , was not given the same favoured status accorded to Flemish Fascists. Nevertheless, it was permitted to republish its newspaper and re-establish and expand its paramilitary wing, the , which had been banned before the war. In April 1943, declared itself part of the SS. The were responsible for numerous attacks against Jews and, from 1944, also participated in arbitrary reprisals against civilians for attacks by the resistance. In 1944, Rexist paramilitaries massacred 20 civilians in the village of Courcelles in retaliation for an assassination of a Rexist politician by members of the resistance.

Striking was the most notable form of passive resistance and often took place on symbolic dates, such as 10 May (the anniversary of the German invasion), 21 July ( National Day) and 11 November (anniversary of the German surrender in World War I). The largest was the "

Striking was the most notable form of passive resistance and often took place on symbolic dates, such as 10 May (the anniversary of the German invasion), 21 July ( National Day) and 11 November (anniversary of the German surrender in World War I). The largest was the "

In June 1944, the

In June 1944, the

The German occupation of Belgium (french: link=no, Occupation allemande, nl, Duitse bezetting) during

The German occupation of Belgium (french: link=no, Occupation allemande, nl, Duitse bezetting) during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

began on 28 May 1940, when the Belgian army surrendered to German forces, and lasted until Belgium's liberation by the Western Allies

The Allies, formally referred to as the United Nations from 1942, were an international military coalition formed during the Second World War (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis powers, led by Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, and Fascist Italy ...

between September 1944 and February 1945. It was the second time in less than thirty years that Germany had occupied Belgium.

After the success of the invasion, a military administration was established in Belgium, bringing the territory under the direct rule of the . Thousands of Belgian soldiers were taken as prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

, and many were not released until 1945. The German administration juggled competing objectives of maintaining order while extracting material from the territory for the war effort. They were assisted by the Belgian civil service, which believed that limited co-operation with the occupiers would result in the least damage to Belgian interests. Belgian Fascist parties in both Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to cultu ...

and Wallonia

Wallonia (; french: Wallonie ), or ; nl, Wallonië ; wa, Waloneye or officially the Walloon Region (french: link=no, Région wallonne),; nl, link=no, Waals gewest; wa, link=no, Redjon walone is one of the three regions of Belgium—al ...

, established before the war, collaborated much more actively with the occupiers; they helped recruit Belgians for the German army and were given more power themselves toward the end of the occupation. Food and fuel were tightly rationed, and all official news was closely censored. Belgian civilians living near possible targets such as railway junctions were in danger of Allied aerial bombing.

From 1942, the occupation became more repressive. Jews suffered systematic persecution and deportation to concentration camps. Despite vigorous protest, the Germans deported Belgian civilians to work in factories in Germany. Meanwhile, the Belgian Resistance

The Belgian Resistance (french: Résistance belge, nl, Belgisch verzet) collectively refers to the resistance movements opposed to the German occupation of Belgium during World War II. Within Belgium, resistance was fragmented between many se ...

, formed in late 1940, expanded vastly. From 1944, the SS and Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

gained much greater control in Belgium, particularly after the military government was replaced in July by a Nazi civil administration, the . In September 1944, Allied forces arrived in Belgium and quickly moved across the country. That December, the territory was incorporated ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legall ...

'' into the Greater German Reich although its collaborationist leaders were already in exile in Germany and German control in the region was virtually non-existent. Belgium was declared fully liberated in February 1945. In total, 40,690 Belgians, over half of them Jews, were killed during the occupation, and the country's pre-war gross domestic product

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a monetary measure of the market value of all the final goods and services produced and sold (not resold) in a specific time period by countries. Due to its complex and subjective nature this measure is of ...

(GDP) was reduced by eight percent.

Background

Belgium had pursued a policy of neutrality since its independence in 1830, successfully avoiding becoming a belligerent in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71). In

Belgium had pursued a policy of neutrality since its independence in 1830, successfully avoiding becoming a belligerent in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71). In World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

invaded Belgium. During the ensuing occupation, the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

encouraged Belgian workers to resist the occupiers through non-compliance, leading to large-scale reprisals against Belgian civilians by the German army.

As political tensions escalated in the years leading to World War II, the Belgian government again announced its intention to remain neutral in the event of war in Europe. The military was reorganised into a defensive force and the country left several international military treaties it had joined in the aftermath of World War I. Construction began of defences in the east of the country. When France and Britain declared war on Germany in September 1939, Belgium remained strictly neutral while mobilising its reserves.

Without warning, the Germans invaded Belgium on 10 May 1940. During the Battle of Belgium

The invasion of Belgium or Belgian campaign (10–28 May 1940), often referred to within Belgium as the 18 Days' Campaign (french: Campagne des 18 jours, nl, Achttiendaagse Veldtocht), formed part of the greater Battle of France, an offensive ...

, the Belgian army

The Land Component ( nl, Landcomponent, french: Composante terre) is the land branch of the Belgian Armed Forces. The King of the Belgians is the commander in chief. The current chief of staff of the Land Component is Major-General Pierre Gérard. ...

was pushed back into a pocket in the northwest of Belgium and surrendered on 28 May. The government fled to France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, and later the United Kingdom, establishing an official government in exile under pre-war Prime Minister Hubert Pierlot. They were responsible for forming a small military force made up of Belgian and colonial troops

Colonial troops or colonial army refers to various military units recruited from, or used as garrison troops in, colonial territories.

Colonial background

Such colonies may lie overseas or in areas dominated by neighbouring land powers such ...

, known as the Free Belgian Forces and which fought as part the Allied forces.

Administration and governance

Shortly after the surrender of the Belgian army, the (a "Military Administration" covering Belgium and the two French departments of Nord and Pas-de-Calais) was created by the Germans withBrussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

as administrative centre. Germany annexed Eupen-Malmedy

Eupen-Malmedy is a small, predominantly German-speaking region in eastern Belgium. It consists of three administrative cantons around the towns of Eupen, Malmedy, and Sankt Vith which encompass some . Elsewhere in Belgium, the region is common ...

, a German-speaking region that Belgium had seized after the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

of 1919. The Military Government was placed under the control of General Alexander von Falkenhausen, an aristocrat and career soldier. Under von Falkenhausen's command, the German administration had two military units at its disposal: the ("Field Gendarmerie", part of the ) and the ''Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one orga ...

'' (the "Secret State Police", part of the SS). The section of the Military Government that dealt with civil matters, the , commanded by Eggert Reeder

SS-''Gruppenführer'' Eggert Reeder (22 July 1894, Poppenbüll – 22 November 1959, Wuppertal) was a German jurist, civil servant, and district president of several regions. Reeder served as civilian administrator of Wehrmacht occupied Be ...

, was responsible for all economic, social and political matters in the territory.

Before leaving the country in 1940, the Belgian government had installed a panel of senior civil-servants, the so-called "

Before leaving the country in 1940, the Belgian government had installed a panel of senior civil-servants, the so-called "Committee of Secretaries-General

The Committee of Secretaries-General (french: Comité des Sécretaires-généraux, nl, Comité van de secretarissen-generaal) was a committee of senior civil servants and technocrats in German-occupied Belgium during World War II. It was forme ...

", to administer the territory in the absence of elected ministers. The Germans retained the Committee during the occupation; it was responsible for implementing demands made by the . The Committee hoped to stop the Germans from becoming involved in the day-to-day administration of the territory, allowing the nation to maintain a degree of autonomy. The Committee also hoped to be able to prevent the implementation of more radical German policies, such as forced labour and deportation. In practice, the Committee merely enabled the Germans to implement their policies more efficiently than the Military Government could have done by force.

In July 1944, the military administration was replaced by a civilian government (), led by Josef Grohé

Josef Grohé (6 November 1902 – 27 December 1987) was a German Nazi Party official. He was the long-serving ''Gauleiter'' of Gau Cologne-Aachen and ''Reichskommissar'' for Belgium and Northern France toward the end of the Second World Wa ...

. The territory was divided into , considerably increasing the power of the Nazi Party and SS in the territory. By 1944 the Germans were increasingly forced to share power, and day-to-day administration was increasingly delegated to Belgian civil authorities and organisations.

Leopold III

Leopold III became

Leopold III became King of the Belgians

Belgium is a constitutional, hereditary, and popular monarchy. The monarch is titled king or queen of the Belgians ( nl, Koning(in) der Belgen, french: Roi / Reine des Belges}, german: König(in) der Belgier) and serves as the country's ...

in 1934, following the death of his father Albert I Albert I may refer to:

People Born before 1300

*Albert I, Count of Vermandois (917–987)

*Albert I, Count of Namur ()

* Albert I of Moha

*Albert I of Brandenburg (), first margrave of Brandenburg

*Albert I, Margrave of Meissen (1158–1195)

*Alber ...

in a mountaineering accident. Leopold was one of the key exponents of Belgian political and military neutrality before the war. Under the Belgian Constitution

The Constitution of Belgium ( nl, Belgische Grondwet, french: Constitution belge, german: Verfassung Belgiens) dates back to 1831. Since then Belgium has been a parliamentary monarchy that applies the principles of ministerial responsibility ...

, Leopold played an important political role, served as commander-in-chief of the military, and personally commanded the Belgian army in May 1940.

On 28 May 1940, the King surrendered to the Germans alongside his soldiers. That violated the constitution, as it contradicted the orders of his ministers, who wanted him to follow the example of the Dutch Queen Wilhelmina

Wilhelmina (; Wilhelmina Helena Pauline Maria; 31 August 1880 – 28 November 1962) was Queen of the Netherlands from 1890 until her abdication in 1948. She reigned for nearly 58 years, longer than any other Dutch monarch. Her reign saw World Wa ...

and flee to France or England to rally resistance. His refusal to leave Belgium undermined his political legitimacy in the eyes of many Belgians, and was viewed as a sign of his support for the new order. He was denounced by the Belgian Prime Minister, Hubert Pierlot, and declared "incompetent to reign" by the government in exile.

Leopold was keen to find an accommodation with Germany in 1940, hoping that Belgium would remain as a unified and semi-autonomous state within a German-dominated Europe. As part of this plan, in November 1940, Leopold visited

Leopold was keen to find an accommodation with Germany in 1940, hoping that Belgium would remain as a unified and semi-autonomous state within a German-dominated Europe. As part of this plan, in November 1940, Leopold visited Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

, the ''Führer

( ; , spelled or ''Fuhrer'' when the umlaut is not available) is a German word meaning "leader" or " guide". As a political title, it is strongly associated with the Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler.

Nazi Germany cultivated the ("leader princip ...

'' of Germany, in Berchtesgaden

Berchtesgaden () is a municipality in the district Berchtesgadener Land, Bavaria, in southeastern Germany, near the border with Austria, south of Salzburg and southeast of Munich. It lies in the Berchtesgaden Alps, south of Berchtesgaden; th ...

to ask for Belgian prisoners of war

Belgian may refer to:

* Something of, or related to, Belgium

* Belgians, people from Belgium or of Belgian descent

* Languages of Belgium, languages spoken in Belgium, such as Dutch, French, and German

*Ancient Belgian language, an extinct languag ...

to be freed. No agreement was reached, and Leopold returned to Belgium. This fueled the belief that Leopold, who had expressed anti-Semitic views before the war, was collaborating with the Nazis rather than defending his country's interests.

Palace of Laeken

The Palace of Laeken or Castle of Laeken (french: Château de Laeken, nl, Kasteel van Laken, german: Schloss zu Laeken) is the official residence of the King of the Belgians and the Belgian Royal Family. It lies in the Brussels-Capital Regi ...

. In 1941, while still incarcerated, he married Mary Lilian Baels, undermining his popularity with the Belgian public, which disliked Baels and considered the marriage to discredit his claim to martyr status. Despite his position, he remained prominent in the occupied territory, and coins and stamps continued to carry his portrait or monogramme. While imprisoned, he sent a letter to Hitler in 1942 credited with saving an estimated 500,000 Belgian women and children from forced deportation to munitions factories in Germany. In January 1944, Leopold was moved to Germany where he remained for the rest of the war.

Despite his position, Leopold remained a figurehead for right-wing resistance movements and Allied propaganda portrayed him as a martyr, sharing his country's fate. Attempts by the government in exile to pursue Leopold to defect to the Allied side were unsuccessful; Leopold consistently refused to publicly support the Allies or to denounce German actions such as the deportation of Belgian workers. After the war, allegations that Leopold's surrender had been an act of collaboration provoked a political crisis over whether he could return to the throne; known as the Royal Question. While a majority voted in March 1950 for Leopold's return to Belgium as king, his return in July 1950 was greeted with widespread protests in Wallonia and a general strike which turned deadly when police open fired on protesters, killing four on 31 July. The next day Leopold announced his intention to abdicate in favour of his son, Baudouin, who took a constitutional oath before the United Chambers of the Belgian Parliament as Prince Royal on 11 August 1950. Leopold formally abdicated in 16 July 1951 and Baudouin ascended the throne and again took a constitutional oath the following day.

Life in occupied Belgium

inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reduct ...

.

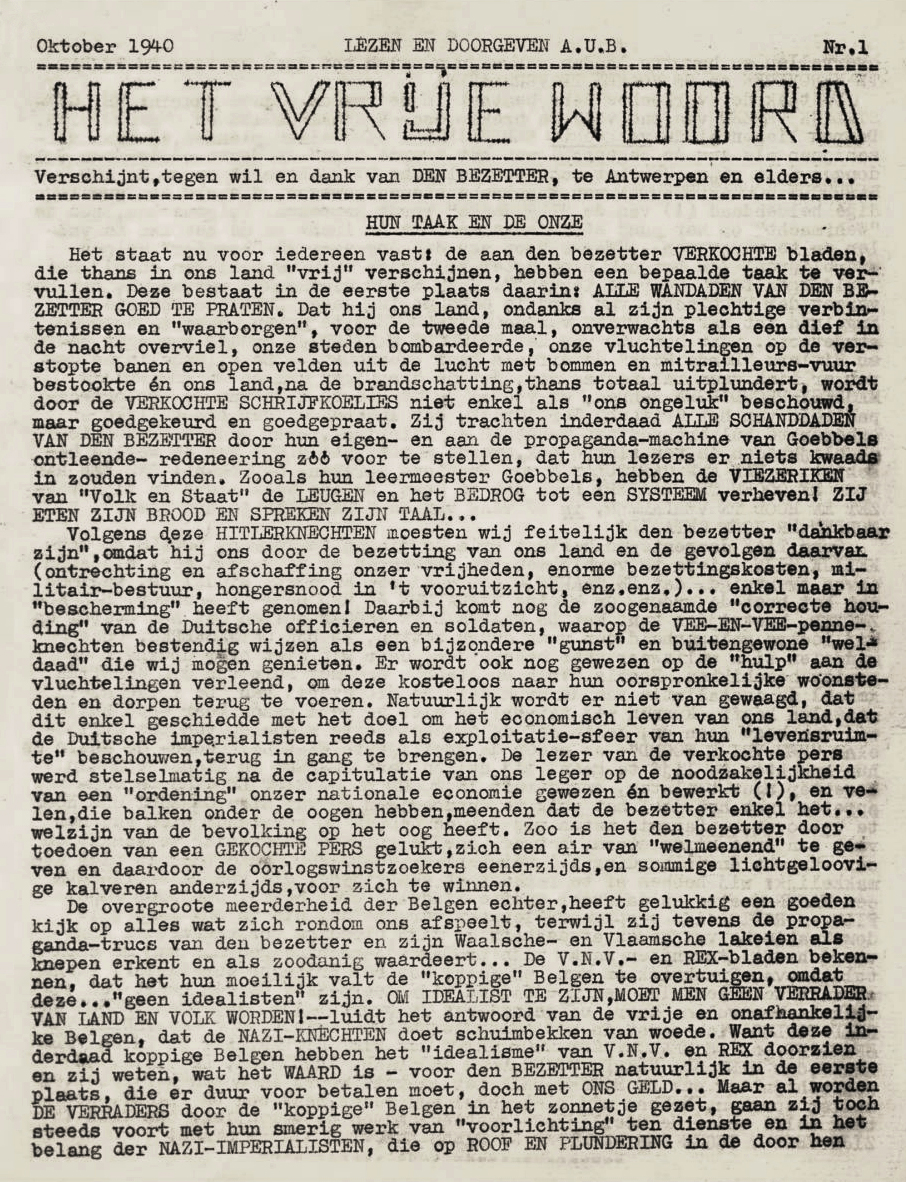

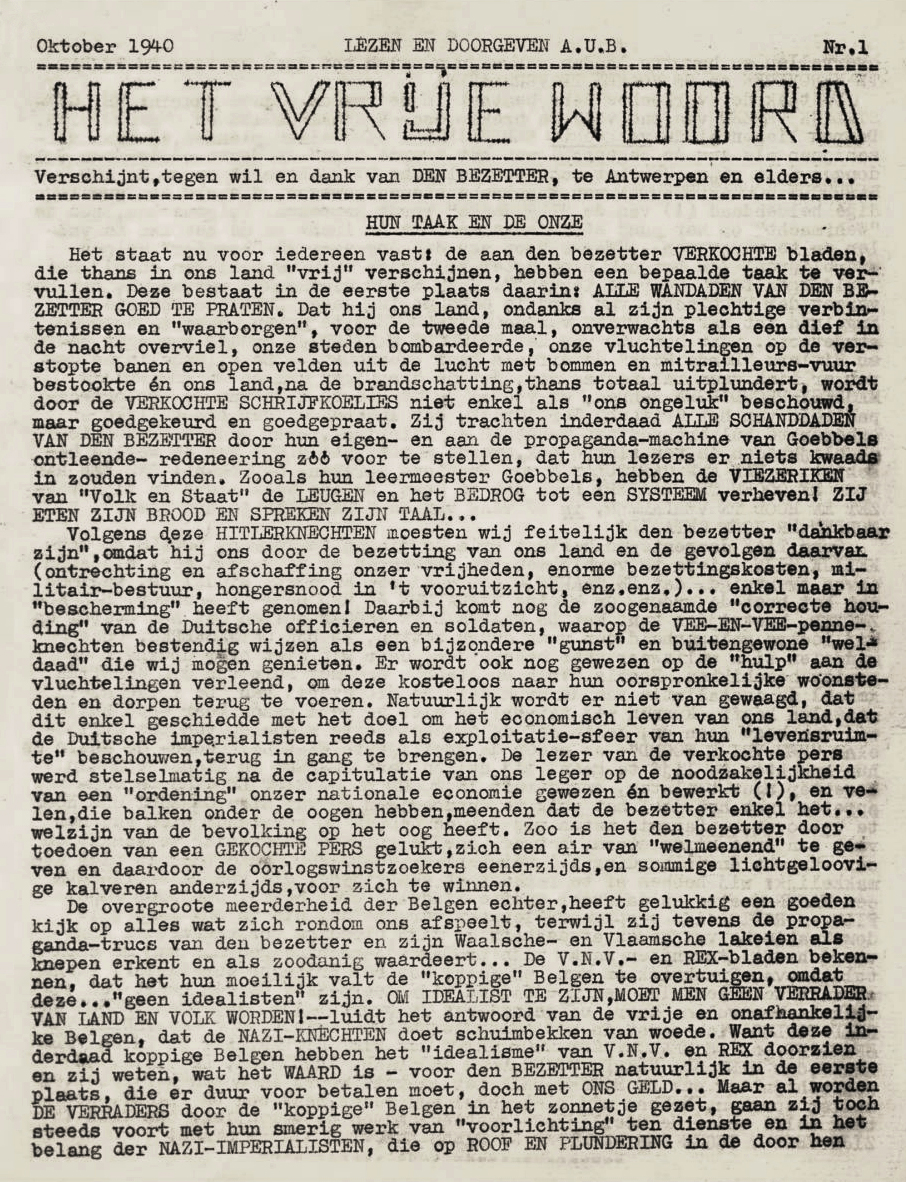

The occupying authorities tightly controlled which newspapers could be published and what news they could print. Newspapers of pro-Nazi political parties continued to be printed, along with so-called "stolen" newspapers such as ''Le Soir

''Le Soir'' (, "The Evening") is a French-language Belgian daily newspaper. Founded in 1887 by Emile Rossel, it was intended as a politically independent source of news. It is one of the most popular Francophone newspapers in Belgium, competing ...

'' or ''Het Laatste Nieuws

''Het Laatste Nieuws'' (; in English ''The Latest News'') is a Dutch-language newspaper based in Antwerp, Belgium. It was founded by Julius Hoste Sr. on 7 June 1888. It is now part of DPG Media, and is the most popular newspaper in Flanders an ...

'', which were published by pro-German groups without their owners' permission. Despite the tight censorship and propagandist content, the circulation of these newspapers remained high, as did the sales of party newspapers such as ''Le Pays Réel

''Le Pays Réel'' ( French; literally "The Real Country") was a Catholic-Fascist newspaper published by the Rexist Party in Belgium. Its first issue appeared on 3 May 1936 and it continued to be published during the Second World War. It was brief ...

'' and '' Volk en Staat''. Many civilians listened to regular broadcasts from Britain, so-called '' Radio Belgique'', despite being officially prohibited from December 1940.

Most Belgians continued their pre-war professions during the occupation. The Belgian cartoonist Hergé

Georges Prosper Remi (; 22 May 1907 – 3 March 1983), known by the pen name Hergé (; ), from the French pronunciation of his reversed initials ''RG'', was a Belgian cartoonist. He is best known for creating ''The Adventures of Tintin'', ...

, whose work since 1928 had contributed to the popularisation of comics in Europe, completed three volumes of ''The Adventures of Tintin

''The Adventures of Tintin'' (french: Les Aventures de Tintin ) is a series of 24 bande dessinée#Formats, ''bande dessinée'' albums created by Belgians, Belgian cartoonist Georges Remi, who wrote under the pen name Hergé. The series was one ...

'' under the occupation, serialised in the pro-German newspaper .

Rationing

Before the war, the Belgian government had planned an emergency system of rationing, which was implemented on the day of the German invasion. The German occupying authority used Belgium's reliance on food imports as a bargaining tool. The amount of food permitted to Belgian citizens was roughly two-thirds of that allowed to comparable German citizens and was amongst the lowest in occupied Europe. On average, scarcity of food led to a loss of five to seven kilograms of weight per Belgian in 1940 alone. A Belgian citizen was entitled to of bread each day, and of butter, sugar, meat and of potatoes each month. Later in the war, even this was not always available and many civilians survived by fishing or by growing vegetables in allotments. Because of the tight rationing, ablack market

A black market, underground economy, or shadow economy is a clandestine market or series of transactions that has some aspect of illegality or is characterized by noncompliance with an institutional set of rules. If the rule defines the ...

in food and other consumer goods emerged. Food on the black market was extremely expensive. Prices could be 650 percent higher than in legal shops and rose constantly during the war. Because of the profits to be made, the black market spawned large and well-organised networks. Numerous members of the German administration were involved in the black market, stealing military or official supplies and reselling them.

Allied bombing

Factories, ports and other strategic sites used by the German war effort were frequent targets of Allied bombers from both the British

Factories, ports and other strategic sites used by the German war effort were frequent targets of Allied bombers from both the British Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

(RAF) and American United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

(USAAF). Many of these were located in towns and cities, and inaccuracy of the bombing resulted in substantial civilian casualties.

In the early years of the occupation, Allied bombing took the form of small-scale attacks on specific targets, such as the ports of Knokke

Knokke () is a town in the municipality of Knokke-Heist, which is located in the province of West Flanders in Flanders, Belgium. The town itself has 15,708 inhabitants (2007), while the municipality of Knokke-Heist has 33,818 inhabitants (2009). ...

and Zeebrugge

Zeebrugge (, from: ''Brugge aan zee'' meaning "Bruges at Sea", french: Zeebruges) is a village on the coast of Belgium and a subdivision of Bruges, for which it is the modern port. Zeebrugge serves as both the international port of Bruges-Zee ...

, and on airfields. The Germans encouraged the building of 6,000 air-raid shelter

Air raid shelters are structures for the protection of non-combatants as well as combatants against enemy attacks from the air. They are similar to bunkers in many regards, although they are not designed to defend against ground attack (but many ...

s between 1941 and 1942, at a cost of 220 million francs. From 1943, the Allies began targeting sites in urban areas. In a raid on the Erla Motor Works in the town of Mortsel

Mortsel () is a city and Municipalities of Belgium, municipality close to the city of Antwerp located in the Belgium, Belgian province of Antwerp (province), Antwerp. The municipality only comprises the city of Mortsel proper. In 2021, Mortsel ha ...

(near Antwerp

Antwerp (; nl, Antwerpen ; french: Anvers ; es, Amberes) is the largest city in Belgium by area at and the capital of Antwerp Province in the Flemish Region. With a population of 520,504,

) on April 5, 1943, just two bombs dropped by the B-17 Flying Fortresses

The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress is a four-engined heavy bomber developed in the 1930s for the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC). Relatively fast and high-flying for a bomber of its era, the B-17 was used primarily in the European Theater ...

of the U.S. 8th Air Force fell on the intended target. The remaining 24 tonnes of bombs fell on civilian areas, killing 936 and injuring 1,340 more.

During the preparation for D-Day

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

in the spring of 1944, the Allies launched the Transport Plan, carrying out intensive bombing of railway junctions and transport networks across northern France and Belgium. Many of these targets were in towns near densely populated civilian areas, such as La Louvière

La Louvière (; wa, El Lovire) is a city and municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Hainaut, Belgium.

The municipality consists of the following districts: Boussoit, Haine-Saint-Paul, Haine-Saint-Pierre, Houdeng-Aimeries, Houde ...

and Kortrijk

Kortrijk ( , ; vls, Kortryk or ''Kortrik''; french: Courtrai ; la, Cortoriacum), sometimes known in English as Courtrai or Courtray ( ), is a Belgian city and municipality in the Flemish province of West Flanders.

It is the capital and larg ...

in Belgium, which were bombed in March 1944. The phase of bombing in the lead up to D-Day alone resulted in 1,500 civilian casualties. Bombing of targets in Belgium steadily increased as the Allies advanced westward across France. Allied bombing during the liberation in September 1944 killed 9,750 Belgians and injured 40,000.

The Allied policy was condemned by many leading figures in Belgium, including Cardinal van Roey, who appealed to Allied commanders to "spare the private possessions of the citizens, as otherwise the civilised world will one day call to account those responsible for the terrible treatment dealt out to an innocent and loyal country".

Economic situation

The German government levied the costs of the military occupation on the Belgians through taxes, while also demanding "external occupation costs" (or " Anti-Bolshevik charges") to support operations elsewhere. In total, Belgium was forced to pay nearly two-thirds of its national income for these charges, equalling 5.7 billionReichsmark

The (; sign: ℛℳ; abbreviation: RM) was the currency of Germany from 1924 until 20 June 1948 in West Germany, where it was replaced with the , and until 23 June 1948 in East Germany, where it was replaced by the East German mark. The Reich ...

s (equivalent to billion euros) over the course of the occupation. The value of the Belgian franc

The Belgian franc ( nl, Belgische frank, french: Franc belge, german: Belgischer Franken) was the currency of the Kingdom of Belgium from 1832 until 2002 when the Euro was introduced. It was subdivided into 100 subunits, each known as a in Dutc ...

was artificially suppressed, further increasing the size of the Anti-Bolshevik charge and benefitting German companies exporting to the occupied country.

The considerable Belgian gold reserves, on which the Belga had been secured, were mostly transported to Britain, Canada and the United States before the German invasion. Over 198 tonnes, however, had been entrusted to the ''Banque de France

The Bank of France (French: ''Banque de France''), headquartered in Paris, is the central bank of France. Founded in 1800, it began as a private institution for managing state debts and issuing notes. It is responsible for the accounts of the ...

'' before the war, and shipped to Dakar

Dakar ( ; ; wo, Ndakaaru) (from daqaar ''tamarind''), is the capital and largest city of Senegal. The city of Dakar proper has a population of 1,030,594, whereas the population of the Dakar metropolitan area is estimated at 3.94 million in 2 ...

in French West Africa

French West Africa (french: Afrique-Occidentale française, ) was a federation of eight French colonial territories in West Africa: Mauritania, Senegal, French Sudan (now Mali), French Guinea (now Guinea), Ivory Coast, Upper Volta (now B ...

. Under the pro-German Vichy régime, the gold was seized by the Germans, who used it to buy munitions from neutral Switzerland and Sweden.

Galopin Doctrine

Before fleeing in May 1940, the Belgian government established a body of important economic figures, under the leadership ofAlexandre Galopin

Alexandre Galopin (26 September 1879 – 28 February 1944) was a Belgian businessman notable for his role in German-occupied Belgium during World War II. Galopin was director of the Société Générale de Belgique, a major Belgian company, and ...

, known as the "Galopin Committee". Galopin was the director of the ''Société Générale de Belgique

The ' ( nl, Generale Maatschappij van België; literally "General Company of Belgium") was a large Belgian bank and later holdings company which existed between 1822 and 2003.

The ''Société générale'' was originally founded as an investm ...

'' (SGB), a company which dominated the Belgian economy and controlled almost 40 percent of the country's industrial production. The Committee was able to negotiate with the German authorities and was also in contact with the government in exile.

Galopin pioneered a controversial policy, known as the "Galopin Doctrine". The Doctrine decreed that Belgian companies continue producing goods necessary for the Belgian population (food, consumer goods etc.) under the German occupiers, but refused to produce war materiel or anything which could be used in the German war effort. The policy hoped to prevent a repeat of World War I, when the Allies had encouraged Belgian workers to passively resist the Germans by refusing to work. The Germans instead deported Belgian workers and industrial machinery to German factories, benefitting their economy more. The policy also hoped to avoid an industrial decline which would have negative effects on the country's recovery after the war; however, many viewed the policy as collaboration. Between 1941 and 1942, the German authorities began to force Belgian businessmen to make an explicit choice between obeying the Doctrine (and refusing to produce war materials, at risk of death) and circumventing the doctrine as collaborators.

Deportation and forced labour

Before 1941, Belgian workers could volunteer to work in Germany; nearly 180,000 Belgians signed up, hoping for better pay and living conditions. About 3,000 Belgians joined the (OT), and 4,000 more joined the paramilitary German supply corps, the (NSKK). The numbers, however, proved insufficient. Despite the protestation of the Secretaries-General, compulsory deportation of Belgian workers to Germany began in October 1942. At the beginning of the scheme, Belgian firms were obliged to select 10 percent of their work force, but from 1943 workers were conscripted by age class. 145,000 Belgians were conscripted and sent to Germany, most to work in manual jobs in industry or agriculture for the German war effort. Working conditions for forced workers in Germany were notoriously poor. Workers were paid little and worked long hours, and those in German towns were particularly vulnerable to Allied aerial bombing.

Following the introduction of compulsory deportation 200,000 Belgian workers (dubbed or ) went into hiding for fear of being conscripted. The were often aided by resistance organisations, such as Organisation Socrates run by the , who provided food and false papers. Many went on to enlist in resistance groups, swelling their numbers enormously from late 1942.

Before 1941, Belgian workers could volunteer to work in Germany; nearly 180,000 Belgians signed up, hoping for better pay and living conditions. About 3,000 Belgians joined the (OT), and 4,000 more joined the paramilitary German supply corps, the (NSKK). The numbers, however, proved insufficient. Despite the protestation of the Secretaries-General, compulsory deportation of Belgian workers to Germany began in October 1942. At the beginning of the scheme, Belgian firms were obliged to select 10 percent of their work force, but from 1943 workers were conscripted by age class. 145,000 Belgians were conscripted and sent to Germany, most to work in manual jobs in industry or agriculture for the German war effort. Working conditions for forced workers in Germany were notoriously poor. Workers were paid little and worked long hours, and those in German towns were particularly vulnerable to Allied aerial bombing.

Following the introduction of compulsory deportation 200,000 Belgian workers (dubbed or ) went into hiding for fear of being conscripted. The were often aided by resistance organisations, such as Organisation Socrates run by the , who provided food and false papers. Many went on to enlist in resistance groups, swelling their numbers enormously from late 1942.

Belgian prisoners of war

After the Belgian defeat, around 225,000 Belgian soldiers (around 30 percent of the total force mobilised in 1940) who had been made prisoners of war in 1940 were sent to prisoner of war camps in Germany. The majority of those in captivity (145,000) were Flemish, and 80,000 were Walloons. Most had been reservists, rather than professional soldiers, before the outbreak of war and their detention created a large labour shortage in civilian occupations. As part of their , the Germans began repatriatingFlemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

prisoners of war in August 1940. By February 1941, 105,833 Flemish soldiers had been repatriated. Gradually, more prisoners were released, but 67,000 Belgian soldiers were still in captivity by 1945. Many prisoners of war were forced to work in quarries or in agriculture and around 2,000 died in captivity.

Repression

In the first year of the occupation, the German administration pursued a conciliatory policy toward the Belgian people in order to gain their support and co-operation. This policy was, in part, because there was little resistance activity and because the demands the Germans needed to place on Belgian civilians and businesses were relatively small on account of their military success. During the fighting in Belgium, however, there were incidents of massacres against Belgian civilians by German forces, notably the Vinkt Massacre in which 86 civilians were killed.

From 1941, the regime became significantly more repressive. This was partly a result of the increasing demands on the German economy created by the

In the first year of the occupation, the German administration pursued a conciliatory policy toward the Belgian people in order to gain their support and co-operation. This policy was, in part, because there was little resistance activity and because the demands the Germans needed to place on Belgian civilians and businesses were relatively small on account of their military success. During the fighting in Belgium, however, there were incidents of massacres against Belgian civilians by German forces, notably the Vinkt Massacre in which 86 civilians were killed.

From 1941, the regime became significantly more repressive. This was partly a result of the increasing demands on the German economy created by the invasion of the Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

, as well as the decision to implement Nazi racial policies. From August 1941, the Military Government announced that for every German murdered by the resistance, five Belgian civilian hostages would be executed. Although the German military command, the (OKW), had advised a ratio of 50 civilians for every one German soldier killed, von Falkenhausen moderated the policy and decreed that the hostages be selected from political prisoners and criminals rather than civilians picked at random. The systematic persecution of minorities (such as Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

, Roma

Roma or ROMA may refer to:

Places Australia

* Roma, Queensland, a town

** Roma Airport

** Roma Courthouse

** Electoral district of Roma, defunct

** Town of Roma, defunct town, now part of the Maranoa Regional Council

* Roma Street, Brisbane, a ...

and Freemasons

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

) began from 1942, and was also coupled with much stricter repression of Belgian political dissent.

Persecution of Jews and the Holocaust

At the start of the war, the population of Belgium was overwhelminglyCatholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. Jews made up the largest non-Christian population in the country, numbering between 70–75,000 out of a population of 8 million. Most lived in large towns and cities in Belgium, such as Antwerp and Brussels. The vast majority were recent immigrants to Belgium fleeing persecution in Germany and Eastern Europe and, as a result, only a small minority actually possessed Belgian citizenship.

Shortly after the invasion of Belgium, the Military Government passed a series of anti-Jewish laws (similar to the

Shortly after the invasion of Belgium, the Military Government passed a series of anti-Jewish laws (similar to the Vichy laws on the status of Jews

Anti-Jewish laws were enacted by the Vichy France government in 1940 and 1941 affecting metropolitan France and its overseas territories during World War II. These laws were, in fact, decrees of head of state Marshal Philippe Pétain, since Parli ...

) in October 1940. The Committee of Secretaries-General refused from the start to co-operate on passing any anti-Jewish measures and the Military Government seemed unwilling to pass further legislation. The German government began to seize Jewish-owned business and forced Jews out of positions in the civil service. In April 1941, without orders from the German authorities, members of the and other Flemish fascists pillaged two synagogues in Antwerp and burned the house of the chief Rabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as '' semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form o ...

of the town in the so-called "Antwerp Pogrom." The Germans also created a in the country, the (AJB; "Association of Jews in Belgium") in which all Jews were required to inscribe.

As part of the "Final Solution

The Final Solution (german: die Endlösung, ) or the Final Solution to the Jewish Question (german: Endlösung der Judenfrage, ) was a Nazi plan for the genocide of individuals they defined as Jews during World War II. The "Final Solution to th ...

" from 1942, the persecution of Belgian Jews escalated. From May 1942, Jews were forced to wear yellow Star-of-David badges to mark them out in public. Using the registers compiled by the AJB, the Germans began deporting Jews to concentration camps built by Germans in occupied Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

. Jews chosen from the lists were required to turn up at the newly established Mechelen transit camp; they were then deported by train

In rail transport, a train (from Old French , from Latin , "to pull, to draw") is a series of connected vehicles that run along a railway track and transport people or freight. Trains are typically pulled or pushed by locomotives (often ...

to concentration camps at Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 Nazi concentration camps, concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, occupied Poland (in a portion annexed int ...

and Bergen-Belsen

Bergen-Belsen , or Belsen, was a Nazi concentration camp in what is today Lower Saxony in northern Germany, southwest of the town of Bergen near Celle. Originally established as a prisoner of war camp, in 1943, parts of it became a concentrati ...

. Between August 1942 and July 1944, around 25,000 Jews and 350 Roma were deported from Belgium; more than 24,000 were killed before their camps were liberated by the Allies. Among them was the celebrated artist Felix Nussbaum

Felix Nussbaum (December 11, 1904 – August 9, 1944) was a German-Jewish surrealist painter. Nussbaum’s work gives insights into the essence of one person among the victims of the Holocaust.

Early life and education

Nussbaum was born in ...

.

From 1942 and the introduction of the Star-of-David badges, opposition to the treatment of the Jews among the general population in Belgium grew. By the end of the occupation, more than 40 percent of all Jews in Belgium were in hiding; many of them hid by gentile

Gentile () is a word that usually means "someone who is not a Jew". Other groups that claim Israelite heritage, notably Mormons, sometimes use the term ''gentile'' to describe outsiders. More rarely, the term is generally used as a synonym fo ...

s and in particular Catholic priests and nuns. Some were helped by the organised resistance, such as the (CDJ), which provided food and safe housing. Many of the Jews in hiding went on to join the armed resistance. The treatment of Jews was denounced by the senior Catholic priest in Belgium, Cardinal Jozef-Ernest van Roey, who described their treatment as "inhuman." The had a notably large Jewish section in Brussels. In April 1943, members of the CDJ attacked the twentieth rail convoy to Auschwitz and succeeded in rescuing many of the passengers.

Political dissent

Because of the Nazi-Soviet Pact, signed in 1939, theCommunist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of '' The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engel ...

was briefly tolerated in the early stages of the occupation. Coinciding with the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 however, the Germans rounded up a large number of Communists (identified in police

The police are a Law enforcement organization, constituted body of Law enforcement officer, persons empowered by a State (polity), state, with the aim to law enforcement, enforce the law, to ensure the safety, health and possessions of citize ...

dossiers compiled before the war) in an operation codenamed "Summer Solstice" (''Sommersonnenwende''). In September 1942, the Germans arrested over 400 workers which they feared were plotting a large-scale strike action.

Many important politicians who had opposed the Nazis before the war were arrested and deported to concentration camps in Germany and German-occupied Poland, as part of the (literally "Night and Fog") decree. Among them was the 71-year-old

Many important politicians who had opposed the Nazis before the war were arrested and deported to concentration camps in Germany and German-occupied Poland, as part of the (literally "Night and Fog") decree. Among them was the 71-year-old Paul-Émile Janson

Paul-Émile (Paul Emil) Janson (30 May 1872 – 3 March 1944) was a francophone Belgian liberal politician and the prime minister from 1937 to 1938. During the German occupation, he was arrested as a political prisoner and died in a German conce ...

who had served as Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

between 1937 and 1938. He was arrested at his home in Belgium in 1943 and deported to Buchenwald concentration camp

Buchenwald (; literally 'beech forest') was a Nazi concentration camp established on hill near Weimar, Germany, in July 1937. It was one of the first and the largest of the concentration camps within Germany's 1937 borders. Many actual or su ...

where he died in 1944. Many captured members of the resistance were also sent to concentration camps. Albert Guérisse

Major General Count Albert-Marie Edmond Guérisse (5 April 1911 – 26 March 1989) was a Belgian Resistance member who organized French and Belgian escape routes for downed Allied pilots during World War II under the alias of Patrick Albert ...

(one of the leading members of the "Pat" escape line) was imprisoned at Dachau

Dachau () was the first concentration camp built by Nazi Germany, opening on 22 March 1933. The camp was initially intended to intern Hitler's political opponents which consisted of: communists, social democrats, and other dissidents. It is lo ...

and briefly served as president of the camp's "International Prisoners' Committee" after its liberation by the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

.

In 1940, the German army requisitioned a former Belgian army fort at Breendonk and transformed it into an or prison camp. Initially, the prison camp was used for detaining Jews, but from 1941 most of those detained at Breendonk were political prisoners or captured members of the resistance. Though it was reasonably small, the camp was infamous for its poor conditions and high death rate. It was also where summary execution

A summary execution is an execution in which a person is accused of a crime and immediately killed without the benefit of a full and fair trial. Executions as the result of summary justice (such as a drumhead court-martial) are sometimes includ ...

s of hostages as reprisals for resistance actions occurred. Unusually, Breendonk was mainly guarded by Flemish collaborators of the , rather than German soldiers. Prisoners were often tortured, or even mauled by the camp commander's dog, and forced to move tonnes of earth around the fort by hand. Many were summarily executed and still more died as a result of the conditions at the camp. Of the 3,500 people incarcerated in Breendonk between November 1942 and April 1943, around 300 people were killed in the camp itself with at least 84 dying as a result of deprivation or torture. Few inmates remained long in Breendonk itself and were sent on to larger concentration camps in Germany.

Collaboration

Both Flanders and Wallonia had right-wing Fascist parties which had been established in the 1930s, often with their own newspapers and paramilitary organisations. All had supported the Belgian policy of neutrality before the war, but after the start of the occupation began to collaborate actively with the Germans. Because of their different ideological backgrounds, they often differed with the Nazis on a variety of ideological issues such as the role ofCatholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

or the status of Flanders. Though allowed more freedom than other political groups, the Germans did not fully trust these organisations and, even by the end of 1941, identified them as a potential "threat to state security".

After the war, 53,000 Belgian citizens (0.6 percent of the population) were found guilty of collaboration, providing the only estimate of the number involved during the period. Around 15,000 Belgians served in two separate divisions of the Waffen-SS

The (, "Armed SS") was the combat branch of the Nazi Party's ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with Waffen-SS foreign volunteers and conscripts, volunteers and conscripts from both occup ...

, divided along linguistic lines. In particular, many Belgians were persuaded to work with the occupiers as a result of long-running hostility to Communism, particularly after the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941.

By 1944, Belgian collaborationist groups began to feel increasingly abandoned by the German government as the situation deteriorated. As resistance attacks against them escalated, collaborationist parties became more violent and launched reprisals against civilians, including the Courcelles Massacre in August 1944.

In Flanders

Before the war, several Fascist movements had existed in Flanders. The two major pre-war

Before the war, several Fascist movements had existed in Flanders. The two major pre-war Flemish Movement

The Flemish Movement ( nl, Vlaamse Beweging) is an umbrella term which encompasses various political groups in the Belgium, Belgian region of Flanders and, less commonly, in French Flanders. Ideologically, it encompasses groups which have sought ...

parties, the (VNV) and , called for the creation of an independent authoritarian Flanders or "'' Dietse Staat''" encompassing both Flanders and the Netherlands. Shortly after the occupation, VNV decided to collaborate with the Germans and soon became the biggest group in Flanders, gaining many members after disbanded in 1941 and after fusing with the Flemish wing of the nationwide Fascist . There was also an organisation, the ("German-Flemish Work Community", known by its acronym DeVlag), which advocated Nazi-style anti-clericalism

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historical anti-clericalism has mainly been opposed to the influence of Roman Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, which seeks to ...

and the inclusion of Flanders into Germany itself.

During the occupation in World War I, the Germans had favoured the Flemish area of the country in the so-called ''Flamenpolitik'', supporting Flemish cultural and political movements. This policy was continued during World War II, as the military government encouraged Flemish Movement parties, especially the VNV, and promoted Flemish nationalists, like Victor Leemans

Victor Leemans (21 July 1901 – 3 March 1971) was a Belgian sociologist, politician and prominent ideologist of the radical Flemish movement in the 1930s. A member of the militant organisation Verdinaso, he is seen by some as the main Flemish ex ...

, to important administrative positions in the occupied territory. In turn, the VNV was important in recruiting men for a new "Flemish Legion", an infantry unit within the , formed in July 1941 after the invasion of Russia. In 1943, the legion was "annexed" into the Waffen SS as the 27th SS ''Langemarck'' Division, despite the protestations of the party. The unit fought on the Eastern Front, where it suffered 10 percent casualties. The Germans also encouraged the formation of independent Flemish paramilitary organisations, such as the ("Flemish Guard"), founded in May 1941, which they hoped would eventually be able to act as a garrison in the region, freeing German troops for the front.

From 1942, VNV's dominance was increasingly challenged by the more radical DeVlag, which had the support of the SS and Nazi Party. DeVlag was closely affiliated to the paramilitary ("General-SS Flanders"), which was stationed in Belgium itself and involved in the so-called Antwerp Pogrom of 1941.

In Wallonia

Though both Fascist and anti-Semitic, 's ideology had been more closely aligned withBenito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

's than with the Nazi Party before the war. 's newspaper , which frequently attacked perceived Nazi anti-clericalism, had even been banned from circulation in Germany in the 1930s. With the German invasion, however, rapidly accepted the occupation and became a major force in collaboration in Wallonia.

As a result of the , was not given the same favoured status accorded to Flemish Fascists. Nevertheless, it was permitted to republish its newspaper and re-establish and expand its paramilitary wing, the , which had been banned before the war. In April 1943, declared itself part of the SS. The were responsible for numerous attacks against Jews and, from 1944, also participated in arbitrary reprisals against civilians for attacks by the resistance. In 1944, Rexist paramilitaries massacred 20 civilians in the village of Courcelles in retaliation for an assassination of a Rexist politician by members of the resistance.

As a result of the , was not given the same favoured status accorded to Flemish Fascists. Nevertheless, it was permitted to republish its newspaper and re-establish and expand its paramilitary wing, the , which had been banned before the war. In April 1943, declared itself part of the SS. The were responsible for numerous attacks against Jews and, from 1944, also participated in arbitrary reprisals against civilians for attacks by the resistance. In 1944, Rexist paramilitaries massacred 20 civilians in the village of Courcelles in retaliation for an assassination of a Rexist politician by members of the resistance.

Léon Degrelle

Léon Joseph Marie Ignace Degrelle (; 15 June 1906 – 31 March 1994) was a Belgian Walloon politician and Nazi collaborator. He rose to prominence in Belgium in the 1930s as the leader of the Rexist Party (Rex). During the German occupatio ...

, the founder and leader of , offered to form a "Walloon Legion" in the Wehrmacht, but his request was denied by the Germans who questioned its feasibility. It was finally accepted in July 1941, after the invasion of Russia, and Degrelle enlisted. As part of the , the Germans refused Degrelle's demands for a "Belgian Legion", preferring to support the creation of separate linguistic units. After a brief period of fighting, it became clear that the Walloon Legion suffered from a lack of training and from political infighting. It was reformed and sent to the Eastern Front, and became part of the Waffen SS (as the 28th SS ''Wallonien'' Division) in 1943. During the fighting at the Korsun–Cherkassy Pocket, the unit was nearly annihilated and its popular commander, Lucien Lippert, was killed. In order to make up numbers, and because of a lack of Belgian volunteers, the unit was allocated French and Spanish volunteers.

Resistance

Resistance to the German occupiers began in Belgium in the winter of 1940, after the German defeat in theBattle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

made it clear that the war was not lost for the Allies. Involvement in illegal resistance activity was a decision made by a minority of Belgians (approximately five percent of the population) but many more were involved in passive resistance

Nonviolent resistance (NVR), or nonviolent action, sometimes called civil resistance, is the practice of achieving goals such as social change through symbolic protests, civil disobedience, economic or political noncooperation, satyagraha, c ...

. If captured, resistance members risked torture and execution, and around 17,000 were killed during the occupation.Henri Bernard's estimate quoted in

Striking was the most notable form of passive resistance and often took place on symbolic dates, such as 10 May (the anniversary of the German invasion), 21 July ( National Day) and 11 November (anniversary of the German surrender in World War I). The largest was the "

Striking was the most notable form of passive resistance and often took place on symbolic dates, such as 10 May (the anniversary of the German invasion), 21 July ( National Day) and 11 November (anniversary of the German surrender in World War I). The largest was the "Strike of the 100,000

The Strike of the 100,000 (french: Grève des 100 000) was an 8-day strike in German-occupied Belgium which took place from 10–18 May 1941. It was led by Julien Lahaut, head of the Belgian Communist Party (''Parti Communiste de Belgique'' or ...

", which broke out on 10 May 1941 in the Cockerill steel works in Seraing. News of the strike spread rapidly and soon at least 70,000 workers were on strike across the province of . The Germans increased workers' salaries by eight percent and the strike finished rapidly. The Germans repressed later large-scale strikes, though further important strikes occurred in November 1942 and February 1943. Passive resistance, however, could also take the form of much more minor actions, such as offering one's seat in trams

A tram (called a streetcar or trolley in North America) is a rail vehicle that travels on tramway tracks on public urban streets; some include segments on segregated right-of-way. The tramlines or networks operated as public transport ar ...

to Jews, which was not explicitly illegal but which subtly subverted the German-imposed order.

Active resistance in Belgium took the form of sabotaging railways and lines of communication as well as hiding Jews and Allied airmen. The resistance produced large numbers of illegal newspapers in both French and Dutch, distributed to the public to provide news about the war not available in officially approved, censored newspapers. Some such publications achieved considerable success, such as ''La Libre Belgique

''La Libre Belgique'' (; literally ''The Free Belgium''), currently sold under the name ''La Libre'', is a major daily newspaper in Belgium. Together with '' Le Soir'', it is one of the country's major French language newspapers and is popular ...

'', which reached a circulation of 70,000. Attacks on German soldiers were comparatively rare as the German administration made a practice of executing at least five Belgian hostages for each German soldier killed. At great personal risk, Belgian civilians also hid large numbers of Jews and political dissenters hunted by the Germans.

Belgian groups such as the Comet Line specialized in helping allied airmen shot down by the Germans evade capture. They sheltered the airmen and, at great risk to themselves, escorted them through occupied France to neutral Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

from where the airmen could be transported back to Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

.

The resistance was never a single group; numerous groups evolved divided by political affiliation, geography or specialisation. The danger of infiltration posed by German informants meant that some groups were extremely small and localised, and although nationwide groups did exist, they were split along political and ideological lines. They ranged from the far left, such as the Communist or Socialist , to the far-right, such as the monarchist and the , which had been created by members of the pre-war Fascist movement. Some, such as , had no obvious political affiliation, but specialised in particular types of resistance activity and recruited only from very specific demographics.

Liberation

In June 1944, the

In June 1944, the Western Allies

The Allies, formally referred to as the United Nations from 1942, were an international military coalition formed during the Second World War (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis powers, led by Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, and Fascist Italy ...

landed in Normandy in Northern France, around west of the Belgian border. After fierce fighting in the areas around the landing sites, the Allies broke through the German lines and began advances toward Paris and then toward the Belgian border. By August, the main body of the German army in Northern France (with the exception of the garrisons of fortified towns such as Dunkirk

Dunkirk (french: Dunkerque ; vls, label=French Flemish, Duunkerke; nl, Duinkerke(n) ; , ;) is a commune in the department of Nord in northern France.

) was openly retreating eastward. As the Allies neared the border, coded messages broadcast on encouraged the resistance to rise up. The German civil administrator, Joseph Grohé, ordered a general retreat from the country on 28 August, and on 1 September the first Allied units (amongst them the Free Belgian SAS) crossed the Belgian frontier. By 4 September, Brussels was in Allied hands. The Belgian government in exile returned to the country on 8 September and began rebuilding the Belgian state and army. Leopold III's brother, Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was " ...

, was appointed Prince-Regent while a decision was made about whether the King could return to his functions. As the German army regrouped and the Allies' supply lines became stretched, the front line stabilised along Belgium's eastern border. Areas in the south-east of the country remained in German hands, and were briefly recaptured during the German Ardennes Offensive

The Battle of the Bulge, also known as the Ardennes Offensive, was the last major German offensive campaign on the Western Front during World War II. The battle lasted from 16 December 1944 to 28 January 1945, towards the end of the war i ...

in the winter of 1944. This no more than delayed the total liberation of the country and on 4 February 1945, with the capture of the village of Krewinkel

Krewinkel is a hamlet in the municipality of Büllingen, in the province of Liège, Belgium. It has 84 inhabitants and lies at an altitude of about 560 meters. Until 1919 it was owned by Germany.

Krewinkel is the easternmost place in Belgium.

O ...

, the entire country was in Allied hands.

Over the course of the occupation, a total of 40,690 Belgians were killed, over half of them Jews. Around eight percent of the country's pre-war GDP had been destroyed or removed to Germany.

See also

*Belgium in World War II

Despite being neutral at the start of World War II, Belgium and its colonial possessions found themselves at war after the country was invaded by German forces on 10 May 1940. After 18 days of fighting in which Belgian forces were pushed bac ...

*Belgian Congo in World War II

The involvement of the Belgian Congo (the modern-day Democratic Republic of the Congo) in World War II began with the German invasion of Belgium in May 1940. Despite Belgium's surrender, the Congo remained in the conflict on the Allied side, ...

* German occupation of Luxembourg in World War II

*'' Secret Army'' – a television series about resistance in Belgium, 1977–79.

Notes

References

Bibliography

;Primary sources * ;General histories * * * ;Thematic studies * * * * * {{WWII history by nationGerman occupation

German-occupied Europe refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly occupied and civil-occupied (including puppet governments) by the military forces and the government of Nazi Germany at various times between 1939 ...

Belgium–Germany relations