German nationalist on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

German nationalism () is an ideological notion that promotes the unity of

German nationalism () is an ideological notion that promotes the unity of

Defining a German nation based on internal characteristics presented difficulties. In reality, most group memberships in "Germany" centered on other, mostly personal or regional ties (for example, to the Lehnsherren) - before the formation of modern nations. Indeed, quasi-national institutions are a basic prerequisite for the creation of a national identity that goes beyond the association of persons. Since the start of the

Defining a German nation based on internal characteristics presented difficulties. In reality, most group memberships in "Germany" centered on other, mostly personal or regional ties (for example, to the Lehnsherren) - before the formation of modern nations. Indeed, quasi-national institutions are a basic prerequisite for the creation of a national identity that goes beyond the association of persons. Since the start of the

The Oxford Handbook of Modern German History

'. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 234-259; here: p. 239-240. However, the cultural elites themselves faced difficulties in defining the German nation, often resorting to broad and vague concepts: the Germans as a "Sprachnation" (a people unified by the same language), a "Kulturnation" (a people unified by the same culture) or an "Erinnerungsgemeinschaft" (a community of remembrance, i.e. sharing a common history).

It was not until the concept of nationalism itself was developed by German philosopher

It was not until the concept of nationalism itself was developed by German philosopher

Forgive, O

The

The

An important element of German nationalism, as promoted by the government and intellectual elite, was the emphasis on Germany asserting itself as a world economic and military power, aimed at competing with

An important element of German nationalism, as promoted by the government and intellectual elite, was the emphasis on Germany asserting itself as a world economic and military power, aimed at competing with

The government established after WWI, the

The government established after WWI, the

The

The

After the Revolutions of 1848/49, in which the liberal nationalistic revolutionaries advocated the Greater German solution, the Austrian defeat in the

After the Revolutions of 1848/49, in which the liberal nationalistic revolutionaries advocated the Greater German solution, the Austrian defeat in the

File:Flag of Germany.svg, Flag of Germany, originally designed in 1848 and used at the

Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

and German-speakers into one unified nation state

A nation state is a political unit where the state and nation are congruent. It is a more precise concept than "country", since a country does not need to have a predominant ethnic group.

A nation, in the sense of a common ethnicity, may inc ...

. German nationalism also emphasizes and takes pride in the patriotism

Patriotism is the feeling of love, devotion, and sense of attachment to one's country. This attachment can be a combination of many different feelings, language relating to one's own homeland, including ethnic, cultural, political or histor ...

and national identity

National identity is a person's identity or sense of belonging to one or more states or to one or more nations. It is the sense of "a nation as a cohesive whole, as represented by distinctive traditions, culture, and language". National identity ...

of Germans as one nation and one person. The earliest origins of German nationalism began with the birth of romantic nationalism

Romantic nationalism (also national romanticism, organic nationalism, identity nationalism) is the form of nationalism in which the state claims its political legitimacy as an organic consequence of the unity of those it governs. This includes ...

during the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

when Pan-Germanism

Pan-Germanism (german: Pangermanismus or '), also occasionally known as Pan-Germanicism, is a pan-nationalist political idea. Pan-Germanists originally sought to unify all the German-speaking people – and possibly also Germanic-speaking ...

started to rise. Advocacy of a German nation-state began to become an important political force in response to the invasion of German territories by France under Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

.

In the 19th century Germans debated the German Question

The "German question" was a debate in the 19th century, especially during the Revolutions of 1848, over the best way to achieve a unification of Germany, unification of all or most lands inhabited by Germans. From 1815 to 1866, about 37 independ ...

over whether the German nation state should comprise a "Lesser Germany

{{more citations needed, date=April 2017

The term Lesser Germany (German: ''Kleindeutschland'') or Lesser German solution (German: Kleindeutsche Lösung) denoted essentially exclusion of Austria of the Habsburgs from the planned German unification ...

" that excluded Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

or a "Greater Germany" that included Austria. The faction led by Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

n Chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of J ...

succeeded in forging a Lesser Germany.

Aggressive German nationalism and territorial expansion was a key factor leading to both World Wars. Prior to World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Germany had established a colonial empire

A colonial empire is a collective of territories (often called colonies), either contiguous with the imperial center or located overseas, settled by the population of a certain state and governed by that state.

Before the expansion of early mode ...

in hopes of rivaling Britain and France. In the 1930s, the Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

came to power and sought to create a Greater Germanic Reich

The Greater Germanic Reich (german: Großgermanisches Reich), fully styled the Greater Germanic Reich of the German Nation (german: Großgermanisches Reich deutscher Nation), was the official state name of the political entity that Nazi Germany ...

, emphasizing ethnic German identity and German greatness to the exclusion of all others, eventually leading to the extermination of Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

, Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in Ce ...

, Romani

Romani may refer to:

Ethnicities

* Romani people, an ethnic group of Northern Indian origin, living dispersed in Europe, the Americas and Asia

** Romani genocide, under Nazi rule

* Romani language, any of several Indo-Aryan languages of the Roma ...

, and other people deemed ''Untermensch

''Untermensch'' (, ; plural: ''Untermenschen'') is a Nazi term for non- Aryan "inferior people" who were often referred to as "the masses from the East", that is Jews, Roma, and Slavs (mainly ethnic Poles, Serbs, and later also Russians). The ...

en'' (subhumans) in the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

After the defeat of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, the country was divided into East

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fa ...

and West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

in the opening acts of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

, and each state retained a sense of German identity and held reunification as a goal, albeit in different contexts. The creation of the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been des ...

was in part an effort to harness German identity to a European identity

Pan-European identity is the sense of personal identification with Europe, in a cultural or political sense. The concept is discussed in the context of European integration, historically in connection with hypothetical proposals, but since th ...

. West Germany underwent its economic miracle

Economic miracle is an informal economic term for a period of dramatic economic development that is entirely unexpected or unexpectedly strong. Economic miracles have occurred in the recent histories of a number of countries, often those undergoing ...

following the war, which led to the creation of a guest worker program A guest worker program allows foreign workers to temporarily reside and work in a host country until a next round of workers is readily available to switch. Guest workers typically perform low or semi-skilled agricultural, industrial, or domesti ...

; many of these workers ended up settling in Germany which has led to tensions around questions of national and cultural identity, especially with regard to Turks who settled in Germany.

German reunification

German reunification (german: link=no, Deutsche Wiedervereinigung) was the process of re-establishing Germany as a united and fully sovereign state, which took place between 2 May 1989 and 15 March 1991. The day of 3 October 1990 when the Ge ...

was achieved in 1990 following ''Die Wende

The Peaceful Revolution (german: Friedliche Revolution), as a part of the Revolutions of 1989, was the process of sociopolitical change that led to the opening of East Germany's borders with the West, the end of the ruling of the Socialist Unity ...

''; an event that caused some alarm both inside and outside Germany. Germany has emerged as a great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power inf ...

inside Europe and in the world; its role in the European debt crisis

The European debt crisis, often also referred to as the eurozone crisis or the European sovereign debt crisis, is a multi-year debt crisis that took place in the European Union (EU) from 2009 until the mid to late 2010s. Several eurozone membe ...

and in the European migrant crisis

The 2015 European migrant crisis, also known internationally as the Syrian refugee crisis, was a period of significantly increased movement of refugees and migrants into Europe in 2015, when 1.3 million people came to the continent to reques ...

have led to criticism of German authoritarian abuse of its power, especially with regard to the Greek debt crisis

Greece faced a sovereign debt crisis in the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2007–2008. Widely known in the country as The Crisis (Greek: Η Κρίση), it reached the populace as a series of sudden reforms and austerity measures that le ...

, and raised questions within and outside Germany as to Germany's role in the world.

Due to post-1945 repudiation of the Nazi regime and its atrocities, German nationalism has been generally viewed in the country as taboo and people within Germany have struggled to find ways to acknowledge its past but take pride in its past and present accomplishments; the German question has never been fully resolved in this regard. A wave of national pride swept the country when it hosted the 2006 FIFA World Cup

The 2006 FIFA World Cup, also branded as Germany 2006, was the 18th FIFA World Cup, the quadrennial international football world championship tournament. It was held from 9 June to 9 July 2006 in Germany, which had won the right to host the ...

. Far-right

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being ...

parties that stress German national identity and pride have existed since the end of World War II but have never governed.

History

Defining a German nation

Defining a German nation based on internal characteristics presented difficulties. In reality, most group memberships in "Germany" centered on other, mostly personal or regional ties (for example, to the Lehnsherren) - before the formation of modern nations. Indeed, quasi-national institutions are a basic prerequisite for the creation of a national identity that goes beyond the association of persons. Since the start of the

Defining a German nation based on internal characteristics presented difficulties. In reality, most group memberships in "Germany" centered on other, mostly personal or regional ties (for example, to the Lehnsherren) - before the formation of modern nations. Indeed, quasi-national institutions are a basic prerequisite for the creation of a national identity that goes beyond the association of persons. Since the start of the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

in the 16th century, the German lands had been divided between Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and Lutherans

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched ...

and linguistic diversity was large as well. Today, the Swabian, Bavarian, Saxon

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

and Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western States of Germany, state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 m ...

dialects

The term dialect (from Latin , , from the Ancient Greek word , 'discourse', from , 'through' and , 'I speak') can refer to either of two distinctly different types of linguistic phenomena:

One usage refers to a variety of a language that is a ...

in their most pure forms are estimated to be 40% mutually intelligible

In linguistics, mutual intelligibility is a relationship between languages or dialects in which speakers of different but related varieties can readily understand each other without prior familiarity or special effort. It is sometimes used as an ...

with more modern Standard German

Standard High German (SHG), less precisely Standard German or High German (not to be confused with High German dialects, more precisely Upper German dialects) (german: Standardhochdeutsch, , or, in Switzerland, ), is the standardized variety ...

, meaning that in a conversation between any native speakers of any of these dialects and a person who speaks only standard German, the latter will be able to understand slightly less than half of what is being said without any prior knowledge of the dialect, a situation which is likely to have been similar or greater in the 19th century. To a lesser extent, however, this fact hardly differs from other regions in Europe.

Nationalism among the Germans first developed not among the general populace but among the intellectual elites of various German states. The early German nationalist Friedrich Karl von Moser, writing in the mid 18th century, remarked that, compared with "the British, Swiss, Dutch and Swedes", the Germans lacked a "national way of thinking".Jansen, Christian (2011), "The Formation of German Nationalism, 1740–1850," in: Helmut Walser Smith (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Modern German History

'. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 234-259; here: p. 239-240. However, the cultural elites themselves faced difficulties in defining the German nation, often resorting to broad and vague concepts: the Germans as a "Sprachnation" (a people unified by the same language), a "Kulturnation" (a people unified by the same culture) or an "Erinnerungsgemeinschaft" (a community of remembrance, i.e. sharing a common history).

Johann Gottlieb Fichte

Johann Gottlieb Fichte (; ; 19 May 1762 – 29 January 1814) was a German philosopher who became a founding figure of the philosophical movement known as German idealism, which developed from the theoretical and ethical writings of Immanuel Kan ...

– considered the founding father of German nationalism – devoted the 4th of his ''Addresses to the German Nation

The ''Addresses to the German Nation'' (German: ''Reden an die deutsche Nation'', 1806) is a political literature book by German philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte that advocates German nationalism in reaction to the occupation and subjugation of ...

'' (1808) to defining the German nation and did so in a very broad manner. In his view, there existed a dichotomy between the people of Germanic descent. There were those who had left their fatherland (which Fichte considered to be Germany) during the time of the Migration Period

The Migration Period was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories by various tribes, and the establishment of the post-Roman ...

and had become either assimilated or heavily influenced by Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

language

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of met ...

, culture

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups.Tyl ...

and customs

Customs is an authority or agency in a country responsible for collecting tariffs and for controlling the flow of goods, including animals, transports, personal effects, and hazardous items, into and out of a country. Traditionally, customs ...

, and those who stayed in their native lands and continued to hold on to their own culture.

Later German nationalists were able to define their nation more precisely, especially following the rise of Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

and formation of the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

in 1871 which gave the majority of German-speakers in Europe a common political, economic and educational framework. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, some German nationalists added elements of racial ideology, ultimately culminating in the Nuremberg Laws

The Nuremberg Laws (german: link=no, Nürnberger Gesetze, ) were antisemitic and racist laws that were enacted in Nazi Germany on 15 September 1935, at a special meeting of the Reichstag convened during the annual Nuremberg Rally of th ...

, sections of which sought to determine by law and genetics who was to be considered German.

19th century

It was not until the concept of nationalism itself was developed by German philosopher

It was not until the concept of nationalism itself was developed by German philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder

Johann Gottfried von Herder ( , ; 25 August 174418 December 1803) was a German philosopher, theologian, poet, and literary critic. He is associated with the Enlightenment, ''Sturm und Drang'', and Weimar Classicism.

Biography

Born in Mohrun ...

that German nationalism began. German nationalism was Romantic in nature and was based upon the principles of collective self-determination, territorial unification and cultural identity, and a political and cultural programme to achieve those ends. The German Romantic nationalism

Romantic nationalism (also national romanticism, organic nationalism, identity nationalism) is the form of nationalism in which the state claims its political legitimacy as an organic consequence of the unity of those it governs. This includes ...

derived from the Enlightenment era

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

's and French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

ary philosopher Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès' ideas of naturalism and that legitimate nations must have been conceived in the state of nature

The state of nature, in moral and political philosophy, religion, social contract theories and international law, is the hypothetical life of people before societies came into existence. Philosophers of the state of nature theory deduce that ther ...

. This emphasis on the naturalness of ethno-linguistic nations continued to be upheld by the early-19th-century Romantic German nationalists Johann Gottlieb Fichte

Johann Gottlieb Fichte (; ; 19 May 1762 – 29 January 1814) was a German philosopher who became a founding figure of the philosophical movement known as German idealism, which developed from the theoretical and ethical writings of Immanuel Kan ...

, Ernst Moritz Arndt

Ernst Moritz Arndt (26 December 1769 – 29 January 1860) was a German nationalist historian, writer and poet. Early in his life, he fought for the abolition of serfdom, later against Napoleonic dominance over Germany. Arndt had to flee to Swe ...

, and Friedrich Ludwig Jahn

(11August 177815October 1852) was a German gymnastics educator and nationalist whose writing is credited with the founding of the German gymnastics (Turner) movement as well as influencing the German Campaign of 1813, during which a coalition of ...

, who all were proponents of Pan-Germanism

Pan-Germanism (german: Pangermanismus or '), also occasionally known as Pan-Germanicism, is a pan-nationalist political idea. Pan-Germanists originally sought to unify all the German-speaking people – and possibly also Germanic-speaking ...

.

The invasion of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

(HRE) by Napoleon's French Empire and its subsequent dissolution brought about a German liberal nationalism

Civic nationalism, also known as liberal nationalism, is a form of nationalism identified by political philosophers who believe in an inclusive form of nationalism that adheres to traditional liberal values of freedom, tolerance, equality, in ...

as advocated primarily by the German middle-class bourgeoisie who advocated the creation of a modern German nation-state

A nation state is a political unit where the state and nation are congruent. It is a more precise concept than "country", since a country does not need to have a predominant ethnic group.

A nation, in the sense of a common ethnicity, may inc ...

based upon liberal democracy

Liberal democracy is the combination of a liberal political ideology that operates under an indirect democratic form of government. It is characterized by elections between multiple distinct political parties, a separation of powers into diff ...

, constitutionalism

Constitutionalism is "a compound of ideas, attitudes, and patterns of behavior elaborating the principle that the authority of government derives from and is limited by a body of fundamental law".

Political organizations are constitutional ...

, representation, and popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the authority of a state and its government are created and sustained by the consent of its people, who are the source of all political power. Popular sovereignty, being a principle, does not imply any ...

while opposing absolutism. Fichte in particular brought German nationalism forward as a response to the French occupation of German territories in his ''Addresses to the German Nation

The ''Addresses to the German Nation'' (German: ''Reden an die deutsche Nation'', 1806) is a political literature book by German philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte that advocates German nationalism in reaction to the occupation and subjugation of ...

'' (1808), evoking a sense of German distinctiveness in language, tradition, and literature that composed a common identity.

After the defeat of France in the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

at the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon B ...

, German nationalists tried but failed to establish Germany as a nation-state, instead the German Confederation

The German Confederation (german: Deutscher Bund, ) was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, w ...

was created that was a loose collection of independent German states that lacked strong federal institutions. Economic integration between the German states was achieved by the creation of the ''Zollverein

The (), or German Customs Union, was a coalition of German states formed to manage tariffs and economic policies within their territories. Organized by the 1833 treaties, it formally started on 1 January 1834. However, its foundations had b ...

'' ("Custom Union") of Germany in 1818 that existed until 1866. The move to create the ''Zollverein'' was led by Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

and the Zollverein was dominated by Prussia, causing resentment and tension between Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

and Prussia.

Romantic nationalism

The Romantic movement was essential in spearheading the upsurge ofGerman nationalism

German nationalism () is an ideological notion that promotes the unity of Germans and German-speakers into one unified nation state. German nationalism also emphasizes and takes pride in the patriotism and national identity of Germans as one na ...

in the 19th century and especially the popular movement aiding the resurgence of Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

after its defeat to Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

in the 1806 Battle of Jena

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

. Johann Gottlieb Fichte

Johann Gottlieb Fichte (; ; 19 May 1762 – 29 January 1814) was a German philosopher who became a founding figure of the philosophical movement known as German idealism, which developed from the theoretical and ethical writings of Immanuel Kan ...

's 1808 ''Addresses to the German Nation

The ''Addresses to the German Nation'' (German: ''Reden an die deutsche Nation'', 1806) is a political literature book by German philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte that advocates German nationalism in reaction to the occupation and subjugation of ...

'', Heinrich von Kleist

Bernd Heinrich Wilhelm von Kleist (18 October 177721 November 1811) was a German poet, dramatist, novelist, short story writer and journalist. His best known works are the theatre plays '' Das Käthchen von Heilbronn'', ''The Broken Jug'', ''Amph ...

's fervent patriotic stage dramas before his death, and Ernst Moritz Arndt

Ernst Moritz Arndt (26 December 1769 – 29 January 1860) was a German nationalist historian, writer and poet. Early in his life, he fought for the abolition of serfdom, later against Napoleonic dominance over Germany. Arndt had to flee to Swe ...

's war poet

A war poet is a poet who participates in a war and writes about their experiences, or a non-combatant who writes poems about war. While the term is applied especially to those who served during the First World War, the term can be applied to a p ...

ry during the anti-Napoleonic struggle of 1813-15 were all instrumental in shaping the character of German nationalism for the next one-and-a-half century in a racialized ethnic rather than civic nationalist

Civic nationalism, also known as liberal nationalism, is a form of nationalism identified by political philosophy, political philosophers who believe in an inclusive form of nationalism that adheres to traditional liberal values of Freedom (po ...

direction. Romanticism also played a role in the popularization of the Kyffhäuser myth, about the Emperor Frederick Barbarossa

Frederick Barbarossa (December 1122 – 10 June 1190), also known as Frederick I (german: link=no, Friedrich I, it, Federico I), was the Holy Roman Emperor from 1155 until his death 35 years later. He was elected King of Germany in Frankfurt o ...

sleeping atop the Kyffhäuser

The Kyffhäuser (,''Duden - Das Aussprachewörterbuch, 7. Auflage (German)'', Dudenverlag, sometimes also referred to as ''Kyffhäusergebirge'', is a hill range in Central Germany, shared by Thuringia and Saxony-Anhalt, southeast of the Harz mou ...

mountain and being expected to rise in a given time and save Germany) and the legend of the Lorelei

The Lorelei ( ; ), spelled Loreley in German, is a , steep slate rock on the right bank of the River Rhine in the Rhine Gorge (or Middle Rhine) at Sankt Goarshausen in Germany, part of the Upper Middle Rhine Valley UNESCO World Heritage Site. Th ...

(by Brentano Brentano is an Italian surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Antonie Brentano, philanthropist

* August Brentano, bookseller

* Bernard von Brentano, novelist

* Christian Brentano, German writer

* Clemens Brentano, poet and novelist ...

and Heine) among others.

The Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

movement later appropriated the nationalistic elements of Romanticism, with Nazi chief ideologue Alfred Rosenberg

Alfred Ernst Rosenberg ( – 16 October 1946) was a Baltic German Nazi theorist and ideologue. Rosenberg was first introduced to Adolf Hitler by Dietrich Eckart and he held several important posts in the Nazi government. He was the head of ...

writing: "The reaction in the form of German Romanticism was therefore as welcome as rain after a long drought. But in our own era of universal internationalism

Internationalism may refer to:

* Cosmopolitanism, the view that all human ethnic groups belong to a single community based on a shared morality as opposed to communitarianism, patriotism and nationalism

* International Style, a major architectur ...

, it becomes necessary to follow this racially linked Romanticism to its core, and to free it from certain nervous convulsions which still adhere to it." Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 19 ...

told theatre directors on 8 May 1933, just two days before the Nazi book burnings

The Nazi book burnings were a campaign conducted by the German Student Union (, ''DSt'') to ceremonially burn books in Nazi Germany and Austria in the 1930s. The books targeted for burning were those viewed as being subversive or as representin ...

in Berlin, that: "German art of the next decade will be heroic, it will be like steel, it will be Romantic, non-sentimental, factual; it will be national with great pathos, and at once obligatory and binding, or it will be nothing."

This made scholars and critics like Fritz Strich Fritz Strich (13 December 1882''Meyers Neues Lexikon.'' Bibliographisches Institut Mannheim, 1980. volume 7: Ru–Td, . – 15 August 1963) was a Swiss-German literature historian.

Life

Born in Königsberg, Strich was a student of Franz Muncker a ...

, Thomas Mann

Paul Thomas Mann ( , ; ; 6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. His highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novella ...

and Victor Klemperer

Victor Klemperer (9 October 188111 February 1960) was a German scholar who also became known as a diarist. His journals, published in Germany in 1995, detailed his life under the German Empire, the Weimar Republic, the Third Reich, and the Germa ...

, who before the war were supporters of Romanticism, to reconsider their stance after the war and the Nazi experience and to adopt a more anti-Romantic position.

Heinrich Heine

Christian Johann Heinrich Heine (; born Harry Heine; 13 December 1797 – 17 February 1856) was a German poet, writer and literary critic. He is best known outside Germany for his early lyric poetry, which was set to music in the form of '' Lied ...

parodied such Romantic modernizations of medieval folkloric myths by 19th century German nationalists in the "''Barbarossa''" chapter of his large 1844 poem '' Germany. A Winter's Tale'':

Barbarossa

Barbarossa, a name meaning "red beard" in Italian, primarily refers to:

* Frederick Barbarossa (1122–1190), Holy Roman Emperor

* Hayreddin Barbarossa (c. 1478–1546), Ottoman admiral

* Operation Barbarossa, the Axis invasion of the Soviet Un ...

, my hasty words!

I do not possess a wise soul

Like you, and I have little patience,

So, please, come back soon, after all!

...

Restore the old Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

,

As it was, whole and immense.

Bring back all its musty junk,

And all its foolish nonsense.

The Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

I’ll endure,

If you bring back the genuine item;

Just rescue us from this bastard state,

And from its farcical system...Revolutions of 1848 to German Unification of 1871

The

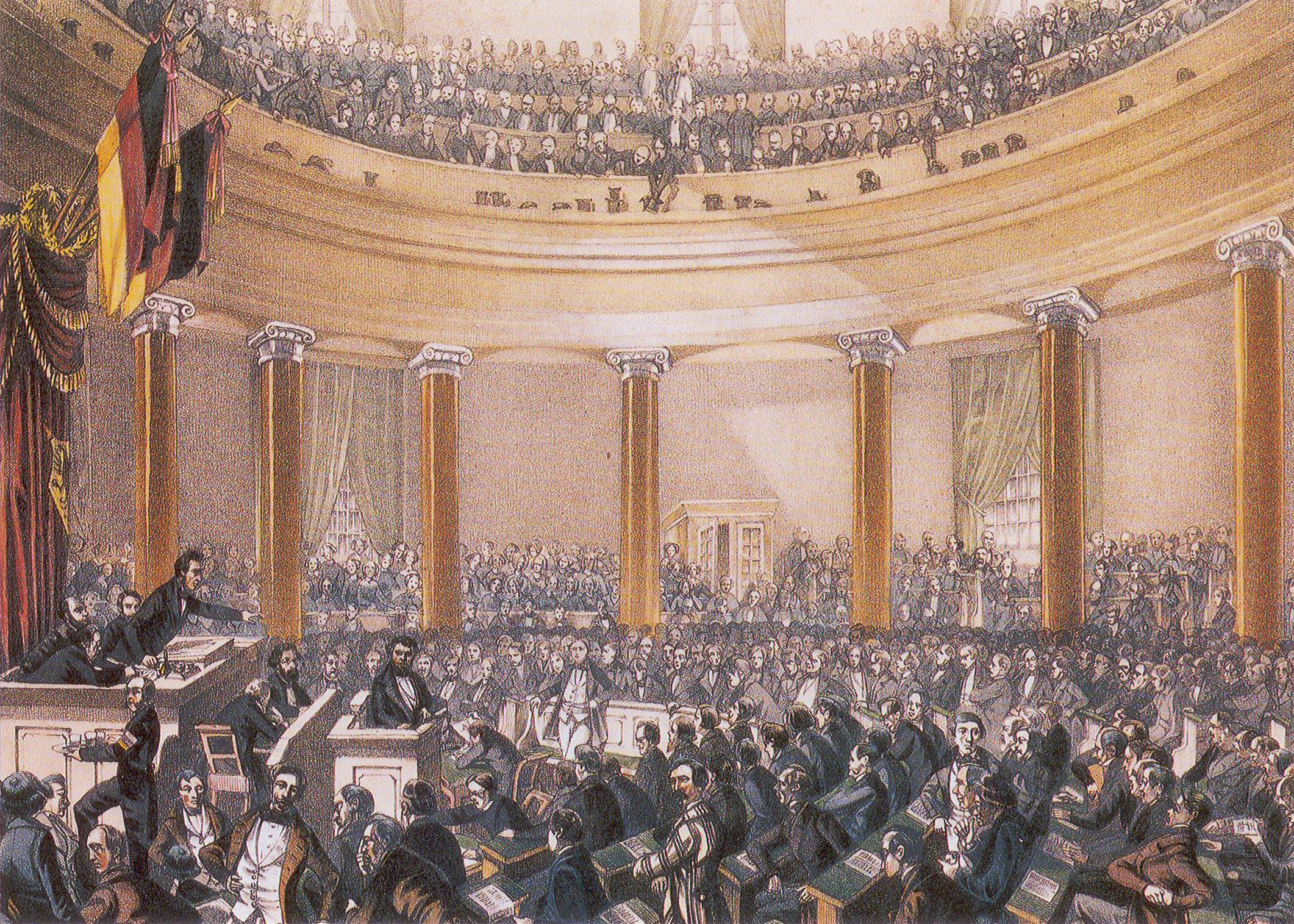

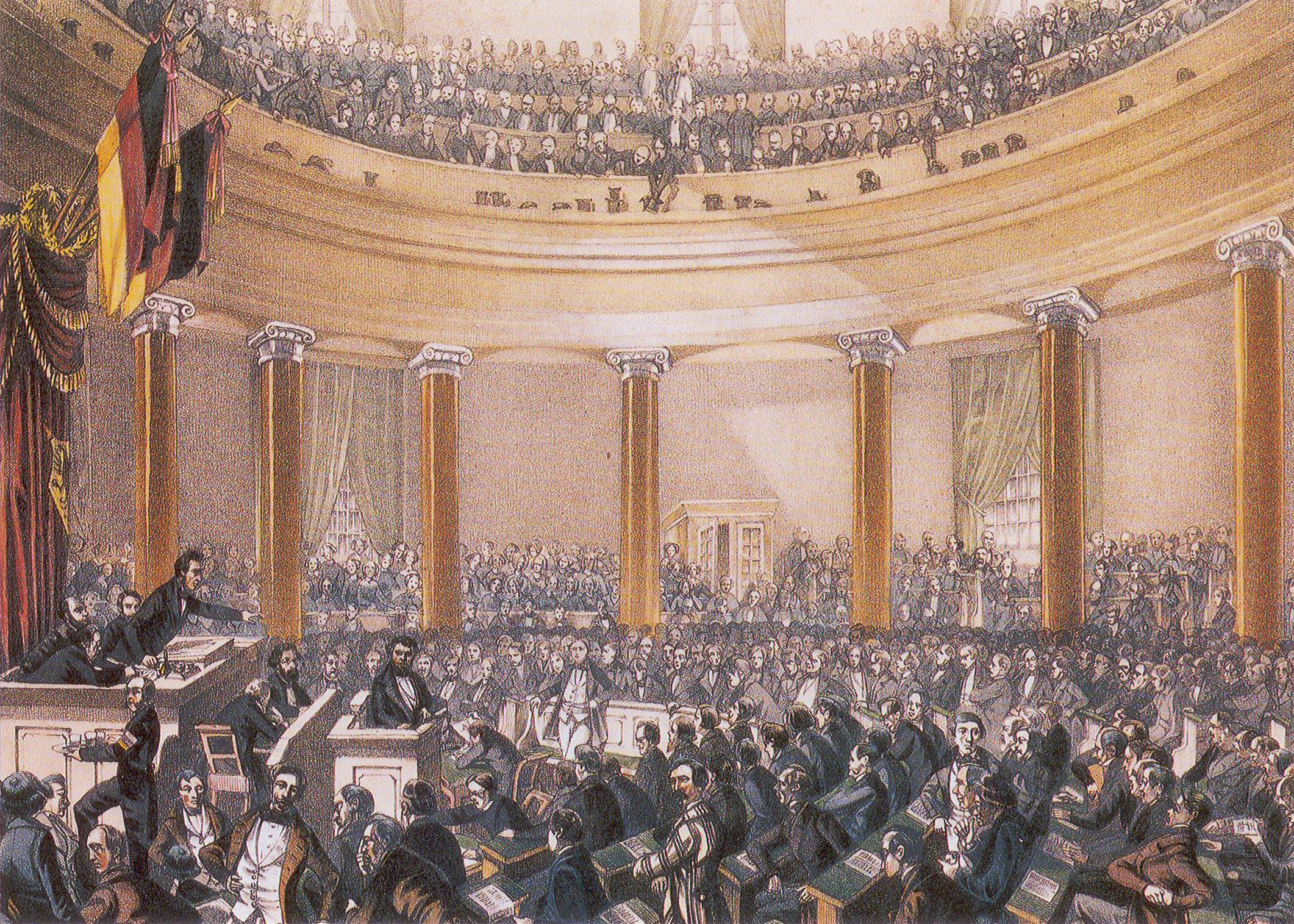

The Revolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europea ...

led to many revolutions in various German states. Nationalists did seize power in a number of German states and an all-German parliament was created in Frankfurt

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , "Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on its na ...

in May 1848. The Frankfurt Parliament

The Frankfurt Parliament (german: Frankfurter Nationalversammlung, literally ''Frankfurt National Assembly'') was the first freely elected parliament for all German states, including the German-populated areas of Austria-Hungary, elected on 1 Ma ...

attempted to create a national constitution for all German states but rivalry between Prussian and Austrian interests resulted in proponents of the parliament advocating a "small German" solution (a monarchical German nation-state without Austria) with the imperial crown of Germany being granted to the King of Prussia

The monarchs of Prussia were members of the House of Hohenzollern who were the hereditary rulers of the former German state of Prussia from its founding in 1525 as the Duchy of Prussia. The Duchy had evolved out of the Teutonic Order, a Roman C ...

. The King of Prussia refused the offer and efforts to create a leftist German nation-state faltered and collapsed.

In the aftermath of the failed attempt to establish a liberal German nation-state, rivalry between Prussia and Austria intensified under the agenda of Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of J ...

who blocked all attempts by Austria to join the ''Zollverein''. A division developed among German nationalists, with one group led by the Prussians that supported a "Lesser Germany" that excluded Austria and another group that supported a "Greater Germany

Pan-Germanism (german: Pangermanismus or '), also occasionally known as Pan-Germanicism, is a pan-nationalist political idea. Pan-Germanists originally sought to unify all the German-speaking people – and possibly also Germanic-speaking ...

" that included Austria. The Prussians sought a Lesser Germany to allow Prussia to assert hegemony over Germany that would not be guaranteed in a Greater Germany. This was a major propaganda point later asserted by Hitler.

By the late 1850s German nationalists emphasized military solutions. The mood was fed by hatred of the French, a fear of Russia, a rejection of the 1815 Vienna settlement, and a cult of patriotic hero-warriors. War seemed to be a desirable means of speeding up change and progress. Nationalists thrilled to the image of the entire people in arms. Bismarck harnessed the national movement's martial pride and desire for unity and glory to weaken the political threat the liberal opposition posed to Prussia's conservatism.

Prussia achieved hegemony over Germany in the "wars of unification": the Second Schleswig War

The Second Schleswig War ( da, Krigen i 1864; german: Deutsch-Dänischer Krieg) also sometimes known as the Dano-Prussian War or Prusso-Danish War was the second military conflict over the Schleswig-Holstein Question of the nineteenth century. T ...

(1864), the Austro-Prussian War

The Austro-Prussian War, also by many variant names such as Seven Weeks' War, German Civil War, Brothers War or Fraternal War, known in Germany as ("German War"), (; "German war of brothers") and by a variety of other names, was fought in 186 ...

(which effectively excluded Austria from Germany) (1866), and the Franco-Prussian War (1870). A German nation-state was founded in 1871 called the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

as a Lesser Germany with the King of Prussia taking the throne of German Emperor

The German Emperor (german: Deutscher Kaiser, ) was the official title of the head of state and hereditary ruler of the German Empire. A specifically chosen term, it was introduced with the 1 January 1871 constitution and lasted until the offi ...

(''Deutscher Kaiser'') and Bismarck becoming Chancellor of Germany

The chancellor of Germany, officially the federal chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany,; often shortened to ''Bundeskanzler''/''Bundeskanzlerin'', / is the head of the federal government of Germany and the commander in chief of the Ge ...

.

1871 to World War I, 1914–1918

Unlike the prior German nationalism of 1848 that was based upon liberal values, the German nationalism utilized by supporters of the German Empire was based upon Prussianauthoritarianism

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political '' status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic vot ...

, and was conservative, reactionary

In political science, a reactionary or a reactionist is a person who holds political views that favor a return to the ''status quo ante'', the previous political state of society, which that person believes possessed positive characteristics abse ...

, anti-Catholic

Anti-Catholicism is hostility towards Catholics or opposition to the Catholic Church, its clergy, and/or its adherents. At various points after the Reformation, some majority Protestant states, including England, Prussia, Scotland, and the Uni ...

, anti-liberal

Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for co ...

and anti-socialist

Criticism of socialism (also known as anti-socialism) is any critique of socialist models of economic organization and their feasibility as well as the political and social implications of adopting such a system. Some critiques are not directed ...

in nature. The German Empire's supporters advocated a Germany based upon Prussian and Protestant cultural dominance. This German nationalism focused on German identity based upon the historical crusading Teutonic Order

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians on ...

. These nationalists supported a German national identity claimed to be based on Bismarck's ideals that included Teutonic values of willpower, loyalty, honesty, and perseverance.

The Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

-Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

divide in Germany at times created extreme tension and hostility between Catholic and Protestant Germans after 1871, such as in response to the policy of ''Kulturkampf

(, 'culture struggle') was the conflict that took place from 1872 to 1878 between the Catholic Church led by Pope Pius IX and the government of Prussia led by Otto von Bismarck. The main issues were clerical control of education and ecclesiastic ...

'' in Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

by German Chancellor and Prussian Prime Minister Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of J ...

, that sought to dismantle Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

culture in Prussia, that provoked outrage amongst Germany's Catholics and resulted in the rise of the pro-Catholic Centre Party and the Bavarian People's Party

The Bavarian People's Party (german: Bayerische Volkspartei; BVP) was the Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria ...

.

There have been rival nationalists within Germany, particularly Bavarian nationalists who claim that the terms that Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

entered into Germany in 1871 were controversial and have claimed the German government has long intruded into the domestic affairs of Bavaria.

German nationalists in the German Empire who advocated a Greater Germany during the Bismarck era focused on overcoming dissidence by Protestant Germans to the inclusion of Catholic Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, image = Hohe_Domkirche_St._Petrus.jpg

, imagewidth = 200px

, alt =

, caption = Cologne Cathedral, Cologne

, abbreviation =

, type = Nati ...

in the state by creating the ''Los von Rom!'' ("Away from Rome!

''Away from Rome!'' (german: Los-von-Rom-Bewegung) was a religious movement founded in Austria by the Pan-German politician Georg Ritter von Schönerer aimed at conversion of all the Roman Catholic German-speaking population of Austria to Lutheran ...

") movement that advocated assimilation of Catholic Germans to Protestantism. During the time of the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

, a third faction of German nationalists (especially in the Austrian parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

) advocated a strong desire for a Greater Germany but, unlike earlier concepts, led by Prussia instead of Austria; they were known as '' Alldeutsche''.

Social Darwinism

Social Darwinism refers to various theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economics and politics, and which were largely defined by scholars in We ...

, messianism

Messianism is the belief in the advent of a messiah who acts as the savior of a group of people. Messianism originated as a Zoroastrianism religious belief and followed to Abrahamic religions, but other religions have messianism-related concepts ...

, and racialism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism (racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies can be more ...

began to become themes used by German nationalists after 1871 based on the concepts of a people's community (''Volksgemeinschaft

''Volksgemeinschaft'' () is a German expression meaning "people's community", "folk community",Richard Grunberger, ''A Social History of the Third Reich'', London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971, p. 44. "national community", or "racial community", ...

'').

Colonial empire

An important element of German nationalism, as promoted by the government and intellectual elite, was the emphasis on Germany asserting itself as a world economic and military power, aimed at competing with

An important element of German nationalism, as promoted by the government and intellectual elite, was the emphasis on Germany asserting itself as a world economic and military power, aimed at competing with France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

for world power. German colonial rule in Africa (1884–1914) was an expression of nationalism and moral superiority that was justified by constructing and employing an image of the natives as "Other". This approach highlighted racist views of mankind. German colonization was characterized by the use of repressive violence in the name of ‘culture’ and ‘civilization’, concepts that had their origins in the Enlightenment. Germany's cultural-missionary project boasted that its colonial programs were humanitarian and educational endeavors. Furthermore, the widespread acceptance among intellectuals of social Darwinism

Social Darwinism refers to various theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economics and politics, and which were largely defined by scholars in We ...

justified Germany's right to acquire colonial territories as a matter of the ‘survival of the fittest’, according to historian Michael Schubert.

Interwar period, 1918–1933

Weimar republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

, established a law of nationality that was based on pre-unification notions of the German volk

The German noun ''Volk'' () translates to people,

both uncountable in the sense of ''people'' as in a crowd, and countable (plural ''Völker'') in the sense of '' a people'' as in an ethnic group or nation (compare the English term ''folk'') ...

as an ethno-racial group defined more by heredity

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic inform ...

than modern notions of citizenship

Citizenship is a "relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection".

Each state determines the conditions under which it will recognize persons as its citizens, and ...

; the laws were intended to include Germans who had immigrated and to exclude immigrant groups. These laws remained the basis of German citizenship laws until after reunification.

The government and economy of the Weimar republic was weak; Germans were dissatisfied with the government, the punitive conditions of war reparations and territorial losses of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

as well as the effects of hyperinflation

In economics, hyperinflation is a very high and typically accelerating inflation. It quickly erodes the real value of the local currency, as the prices of all goods increase. This causes people to minimize their holdings in that currency as t ...

. Economic, social, and political cleavages fragmented Germany's society. Eventually the Weimar Republic collapsed under these pressures and the political maneuverings of leading German officials and politicians.

Nazi Germany, 1933–1945

The

The Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

(NSDAP), led by Austrian-born Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

, believed in an extreme form of German nationalism. The first point of the Nazi 25-point programme was that "We demand the unification of all Germans in the Greater Germany

Pan-Germanism (german: Pangermanismus or '), also occasionally known as Pan-Germanicism, is a pan-nationalist political idea. Pan-Germanists originally sought to unify all the German-speaking people – and possibly also Germanic-speaking ...

on the basis of the people's right to self-determination". Hitler, an Austrian-German by birth, began to develop his strong patriotic German nationalist

German nationalism () is an ideological notion that promotes the unity of Germans and German-speakers into one unified nation state. German nationalism also emphasizes and takes pride in the patriotism and national identity of Germans as one nat ...

views from a very young age. He was greatly influenced by many other Austrian pan-German nationalists in Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, notably Georg Ritter von Schönerer

Georg Ritter von Schönerer (17 July 1842 – 14 August 1921) was an Austrian landowner and politician of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy active in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A major exponent of pan-Germanism and German nationalism in ...

and Karl Lueger

Karl Lueger (; 24 October 1844 – 10 March 1910) was an Austrian politician, mayor of Vienna, and leader and founder of the Austrian Christian Social Party. He is credited with the transformation of the city of Vienna into a modern city. The pop ...

. Hitler's pan-German ideas envisioned a Greater German Reich which was to include the Austrian Germans, Sudeten Germans and other ethnic Germans. The annexing of Austria ''(Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a " Greater Germany ...

)'' and the Sudetenland ''( annexing of Sudetenland)'' completed Nazi Germany's desire to the German nationalism of the German Volksdeutsche

In Nazi German terminology, ''Volksdeutsche'' () were "people whose language and culture had German origins but who did not hold German citizenship". The term is the nominalised plural of '' volksdeutsch'', with ''Volksdeutsche'' denoting a sin ...

(people/folk).

The ''Generalplan Ost

The ''Generalplan Ost'' (; en, Master Plan for the East), abbreviated GPO, was the Nazi German government's plan for the genocide and ethnic cleansing on a vast scale, and colonization of Central and Eastern Europe by Germans. It was to be un ...

'' called for the extermination, expulsion, Germanization

Germanisation, or Germanization, is the spread of the German language, people and culture. It was a central idea of German conservative thought in the 19th and the 20th centuries, when conservatism and ethnic nationalism went hand in hand. In ling ...

or enslavement of most or all Czechs, Poles, Russians, Belarusians and Ukrainians for the purpose of providing more living space

Housing, or more generally, living spaces, refers to the construction and assigned usage of houses or buildings individually or collectively, for the purpose of shelter. Housing ensures that members of society have a place to live, whether ...

for the German people.

1945 to the present

After WWII, the German nation was divided in two states,West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

and East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

, and some former German territories east of the Oder–Neisse line

The Oder–Neisse line (german: Oder-Neiße-Grenze, pl, granica na Odrze i Nysie Łużyckiej) is the basis of most of the international border between Germany and Poland from 1990. It runs mainly along the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers a ...

were made part of Poland. The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany

The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany (german: Grundgesetz für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland) is the constitution of the Federal Republic of Germany.

The West German Constitution was approved in Bonn on 8 May 1949 and came in ...

which served as the constitution for West Germany was conceived and written as a provisional document, with the hope of reuniting East and West Germany in mind.

The formation of the European Economic Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organization created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisb ...

, and latterly the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been des ...

, was driven in part by forces inside and outside Germany that sought to embed Germany identity more deeply in a broader European identity, in a kind of "collaborative nationalism".

The reunification of Germany became a central theme in West German politics, and was made a central tenet of the East German Socialist Unity Party of Germany

The Socialist Unity Party of Germany (german: Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands, ; SED, ), often known in English as the East German Communist Party, was the founding and ruling party of the German Democratic Republic (GDR; East German ...

, albeit in the context of a Marxist vision of history in which the government of West Germany would be swept away in a proletarian revolution.

The question of Germans and former German territory in Poland, as well as the status of Königsberg

Königsberg (, ) was the historic Prussian city that is now Kaliningrad, Russia. Königsberg was founded in 1255 on the site of the ancient Old Prussian settlement ''Twangste'' by the Teutonic Knights during the Northern Crusades, and was named ...

as part of Russia, remained hard, with people in West Germany advocating to take that territory back through the 1960s. East Germany confirmed the border with Poland in 1950, while West Germany, after a period of refusal, finally accepted the border (with reservations) in 1970.

The desire of the German people to be one nation again remained strong, but was accompanied by a feeling of hopelessness through the 1970s and into the 1980s; Die Wende

The Peaceful Revolution (german: Friedliche Revolution), as a part of the Revolutions of 1989, was the process of sociopolitical change that led to the opening of East Germany's borders with the West, the end of the ruling of the Socialist Unity ...

, when it arrived in the late 1980s driven by the East German people, came as a surprise, leading to the 1990 elections which put a government in place that negotiated the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany

The Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany (german: Vertrag über die abschließende Regelung in Bezug auf Deutschland;

rus, Договор об окончательном урегулировании в отношении Ге� ...

and reunited East and West Germany, and the process of inner reunification began.

The reunification was opposed in several quarters both inside and outside Germany, including Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. S ...

, Jürgen Habermas

Jürgen Habermas (, ; ; born 18 June 1929) is a German social theorist in the tradition of critical theory and pragmatism. His work addresses communicative rationality and the public sphere.

Associated with the Frankfurt School, Habermas's wor ...

, and Günter Grass

Günter Wilhelm Grass (born Graß; ; 16 October 1927 – 13 April 2015) was a German novelist, poet, playwright, illustrator, graphic artist, sculptor, and recipient of the 1999 Nobel Prize in Literature.

He was born in the Free City of Da ...

, out of fear of that a united Germany might resume its aggression toward other countries. Just prior to reunification West Germany had gone through a national debate, called Historikerstreit

The ''Historikerstreit'' (, "historians' dispute") was a dispute in the late 1980s in West Germany between conservative and left-of-center academics and other intellectuals about how to incorporate Nazi Germany and the Holocaust into German hist ...

, over how to regard its Nazi past, with one side claiming that there was nothing specifically German about Nazism, and that the German people should let go its shame over the past and look forward, proud of its national identity, and others holding that Nazism grew out of German identity and the nation needed to remain responsible for its past and guard carefully against any recrudescence of Nazism. This debate did not give comfort to those concerned about whether a reunited Germany might be a danger to other countries, nor did the rise of skinhead

A skinhead is a member of a subculture which originated among working class youths in London, England, in the 1960s and soon spread to other parts of the United Kingdom, with a second working class skinhead movement emerging worldwide in th ...

neo-nazi

Neo-Nazism comprises the post–World War II militant, social, and political movements that seek to revive and reinstate Nazism, Nazi ideology. Neo-Nazis employ their ideology to promote hatred and Supremacism#Racial, racial supremacy (ofte ...

groups in the former East Germany, as exemplified by riots in Hoyerswerda

Hoyerswerda () or Wojerecy () is a major district town in the district of Bautzen in the German state of Saxony. It is located in the Sorbian settlement area of Upper Lusatia, a region where some people speak the Sorbian language in addition to G ...

in 1991. An identity-based nationalist backlash arose after unification as people reached backward to answer "the German question", leading to violence by four Neo-Nazi

Neo-Nazism comprises the post–World War II militant, social, and political movements that seek to revive and reinstate Nazism, Nazi ideology. Neo-Nazis employ their ideology to promote hatred and Supremacism#Racial, racial supremacy (ofte ...

/far-right

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being ...

parties which were all banned by Germany's Federal Constitutional Court

The Federal Constitutional Court (german: link=no, Bundesverfassungsgericht ; abbreviated: ) is the supreme constitutional court for the Federal Republic of Germany, established by the constitution or Basic Law () of Germany. Since its inc ...

after committing or inciting violence: the Nationalist Front, National Offensive The National Offensive (german: Nationale Offensive; abbreviated NO) was a German neo-Nazi party, which existed from 3 July 1990 to 22 December 1992. ''Verfassungsschutzbericht'' 1990. Verfassungsschutz. ISSN 0177-0357. Pg. 99

It was founded by M ...

, German Alternative

The German Alternative (german: Deutsche Alternative or ) was a minor neo-nazi group set up in Germany by Michael Kühnen in 1989.

Ideology

Its declared goal was the restoration of the German Reich and rejected the cession of German areas in ...

, and the Kamaradenbund.

One of the key questions for the reunified government, was how to define a German citizen. The laws inherited from the Weimar republic that based citizenship on heredity had been taken to their extreme by the Nazis and were unpalatable and fed the ideology of German far-right nationalist parties like the National Democratic Party of Germany

The National Democratic Party of Germany (german: Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands or NPD) is a far-right Neo-Nazi and ultranationalist political party in Germany.

The party was founded in 1964 as successor to the German Reich Party ...

(NPD) which was founded in 1964 from other far-right groups. Additionally, West Germany had received large numbers of immigrants (especially Turks

Turk or Turks may refer to:

Communities and ethnic groups

* Turkic peoples, a collection of ethnic groups who speak Turkic languages

* Turkish people, or the Turks, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

* Turkish citizen, a citizen of the Republic o ...

), membership in the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been des ...

meant that people could move more or less freely across national borders within Europe, and due to its declining birthrate even united Germany needed to receive about 300,000 immigrants per year in order to maintain its workforce. (Germany had been importing workers ever since its post-war "economic miracle" through its Gastarbeiter

(; both singular and plural; ) are foreign worker, foreign or migrant workers, particularly those who had moved to West Germany between 1955 and 1973, seeking work as part of a formal guest worker program (). As a result, guestworkers are ge ...

program.) The Christian Democratic Union/ Christian Social Union government that was elected throughout the 1990s did not change the laws, but around 2000 a new coalition led by the Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Party of Germany (german: Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, ; SPD, ) is a centre-left social democratic political party in Germany. It is one of the major parties of contemporary Germany.

Saskia Esken has been the ...

came to power and made changes to the law defining who was a German based on ''jus soli

''Jus soli'' ( , , ; meaning "right of soil"), commonly referred to as birthright citizenship, is the right of anyone born in the territory of a state to nationality or citizenship.

''Jus soli'' was part of the English common law, in contras ...

'' rather than ''jus sanguinis

( , , ; 'right of blood') is a principle of nationality law by which citizenship is determined or acquired by the nationality or ethnicity of one or both parents. Children at birth may be citizens of a particular state if either or both of t ...

''.

The issue of how to address its Turkish population has remained a difficult issue in Germany; many Turks have not integrated and have formed a parallel society

Parallel society refers to the self-organization of an ethnic or religious minority, often but not always immigrant groups, with the intent of a reduced or minimal spatial, social and cultural contact with the majority society into which they immi ...

inside Germany, and issues of using education or legal penalties to drive integration have roiled Germany from time to time, and issues of what a "German" is, accompany debates about "the Turkish question".

Pride in being German remained a difficult issue; one of the surprises of the 2006 FIFA World Cup

The 2006 FIFA World Cup, also branded as Germany 2006, was the 18th FIFA World Cup, the quadrennial international football world championship tournament. It was held from 9 June to 9 July 2006 in Germany, which had won the right to host the ...

which was held in Germany, were widespread displays of national pride by Germans, which seemed to take even the Germans themselves by surprise and cautious delight.

Germany's role in managing the European debt crisis

The European debt crisis, often also referred to as the eurozone crisis or the European sovereign debt crisis, is a multi-year debt crisis that took place in the European Union (EU) from 2009 until the mid to late 2010s. Several eurozone membe ...

, especially with regard to the Greek government-debt crisis

Greece faced a sovereign debt crisis in the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2007–2008. Widely known in the country as The Crisis ( Greek: Η Κρίση), it reached the populace as a series of sudden reforms and austerity measures that ...

, led to criticism from some quarters, especially within Greece, of Germany wielding its power in a harsh and authoritarian way that was reminiscent of its authoritarian past and identity.

Tensions over the European debt crisis

The European debt crisis, often also referred to as the eurozone crisis or the European sovereign debt crisis, is a multi-year debt crisis that took place in the European Union (EU) from 2009 until the mid to late 2010s. Several eurozone membe ...

and the European migrant crisis

The 2015 European migrant crisis, also known internationally as the Syrian refugee crisis, was a period of significantly increased movement of refugees and migrants into Europe in 2015, when 1.3 million people came to the continent to reques ...

and the rise of right-wing populism

Right-wing populism, also called national populism and right-wing nationalism, is a political ideology that combines right-wing politics and populist rhetoric and themes. Its rhetoric employs anti-elitist sentiments, opposition to the Establi ...

sharpened questions of German identity around 2010. The Alternative for Germany

Alternative for Germany (german: link=no, Alternative für Deutschland, AfD; ) is a right-wing populist

*

*

*

*

*

*

* political party in Germany. AfD is known for its opposition to the European Union, as well as immigration to Germany. I ...

party was created in 2013 as a backlash against further European integration and bailouts of other countries during the European debt crisis; from its founding to 2017 the party took on nationalist and populist stances, rejecting German guilt over the Nazi era and calling for Germans to take pride in their history and accomplishments.

In the 2014 European Parliament election

The 2014 European Parliament election was held in the European Union, from 22 to 25 May 2014.

It was the 8th parliamentary election since the first direct elections in 1979, and the first in which the European political parties fielded candid ...

, the NPD won their first ever seat in the European Parliament