The German colonial empire (german: Deutsches Kolonialreich) constituted the overseas colonies, dependencies and territories of the

German Empire. Unified in the early 1870s, the chancellor of this time period was

Otto von Bismarck. Short-lived attempts at

colonization by

individual German states had occurred in preceding centuries, but Bismarck resisted pressure to construct a colonial empire until the

Scramble for Africa in 1884. Claiming much of the left-over uncolonized areas of Africa, Germany built the third-largest

colonial empire at the time, after the

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

and

French. The German Colonial Empire encompassed parts of several African countries, including parts of present-day

Burundi,

Rwanda,

Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands ...

,

Namibia

Namibia (, ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and ea ...

,

Cameroon

Cameroon (; french: Cameroun, ff, Kamerun), officially the Republic of Cameroon (french: République du Cameroun, links=no), is a country in west-central Africa. It is bordered by Nigeria to the west and north; Chad to the northeast; the C ...

,

Gabon

Gabon (; ; snq, Ngabu), officially the Gabonese Republic (french: République gabonaise), is a country on the west coast of Central Africa. Located on the equator, it is bordered by Equatorial Guinea to the northwest, Cameroon to the nort ...

,

Congo,

Central African Republic

The Central African Republic (CAR; ; , RCA; , or , ) is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Chad to the north, Sudan to the northeast, South Sudan to the southeast, the DR Congo to the south, the Republic of th ...

,

Chad,

Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

,

Togo

Togo (), officially the Togolese Republic (french: République togolaise), is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Ghana to the west, Benin to the east and Burkina Faso to the north. It extends south to the Gulf of Guinea, where its c ...

,

Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and To ...

, as well as northeastern

New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torr ...

,

Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands ( Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands ( Manono and Apolima); ...

and numerous

Micronesia

Micronesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, consisting of about 2,000 small islands in the western Pacific Ocean. It has a close shared cultural history with three other island regions: the Philippines to the west, Polynesia to the east, and ...

n islands. Including mainland Germany, the empire had a total land area of 3,503,352 square kilometers and population of 80,125,993 people.

Germany lost control of most of its colonial empire at the beginning of the

First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in 1914, but some German forces held out in

German East Africa until the end of the war. After the

German defeat in World War I, Germany's colonial empire was officially dissolved with the

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

. Each colony became a

League of Nations mandate under the supervision (but not ownership) of one of the victorious powers. Talk of regaining their lost colonial possessions persisted in Germany until 1943, but never became an official goal of the German government.

Origins

Germans had traditions of foreign sea-borne trade dating back to the

Hanseatic League; German emigrants had flowed eastward in the direction of the

Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

* Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originati ...

littoral

The littoral zone or nearshore is the part of a sea, lake, or river that is close to the shore. In coastal ecology, the littoral zone includes the intertidal zone extending from the high water mark (which is rarely inundated), to coastal a ...

,

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

and

Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

and westward to the

Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

; and North German merchants and

missionaries showed interest in overseas engagements. The Hanseatic republics of

Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

and

Bremen sent traders across the globe. Their

trading house

A joint-stock company is a business entity in which shares of the company's stock can be bought and sold by shareholders. Each shareholder owns company stock in proportion, evidenced by their shares (certificates of ownership). Shareholders are ...

s conducted themselves as successful ''Privatkolonisatoren''

ndependent colonizers concluding treaties and land purchases in Africa and the

Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

with chiefs and/or other tribal leaders. These early agreements with local entities later formed the basis for annexation treaties, diplomatic support and military protection by the

German government

The Federal Cabinet or Federal Government (german: link=no, Bundeskabinett or ') is the chief executive body of the Federal Republic of Germany. It consists of the Federal Chancellor and cabinet ministers. The fundamentals of the cabinet's or ...

.

However, until their

1871 unification, the German states had not concentrated on the development of a navy, and this essentially had precluded German participation in earlier

imperialist

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

scrambles for remote

colonial

Colonial or The Colonial may refer to:

* Colonial, of, relating to, or characteristic of a colony or colony (biology)

Architecture

* American colonial architecture

* French Colonial

* Spanish Colonial architecture

Automobiles

* Colonial (1920 au ...

territory. Without a blue-water navy, a would-be colonial power could not reliably defend, supply or trade with overseas dependencies. The German states prior to 1870 had retained separate political structures and goals, and

German foreign policy up to and including the age of

Otto von Bismarck (1815–1898; in office as Prussian Foreign Minister from 1862 to 1890) concentrated on resolving the "

German question

The "German question" was a debate in the 19th century, especially during the Revolutions of 1848, over the best way to achieve a unification of all or most lands inhabited by Germans. From 1815 to 1866, about 37 independent German-speaking sta ...

" in Europe and on securing German interests on the continent. However, by 1891 the Germans were mostly united under Prussian rule.

[Biskup, Thomas; Kohlrausch, Martin. "Germany 2: Colonial Empire". Credo Online. Credo Reference.] They also sought a more clear-cut "German" state, and saw colonies as a good way to achieve that.

German Confederation and the Zollverein

In the states of the

German Confederation

The German Confederation (german: Deutscher Bund, ) was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, w ...

founded in 1815 and the

Zollverein

The (), or German Customs Union, was a coalition of German states formed to manage tariffs and economic policies within their territories. Organized by the 1833 treaties, it formally started on 1 January 1834. However, its foundations had b ...

founded in 1834, there was some call from private and economic interests for the establishment of German colonies, especially in the 1840s. However, governments had no such aspirations. In 1839, private interests founded the , which sought to purchase the

Chatham Islands

The Chatham Islands ( ) (Moriori: ''Rēkohu'', 'Misty Sun'; mi, Wharekauri) are an archipelago in the Pacific Ocean about east of New Zealand's South Island. They are administered as part of New Zealand. The archipelago consists of about te ...

east of New Zealand and settle German emigrants there, but

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

had a pre-existing claim to the island.

Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

relied on the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

for its worldwide shipping interests and therefore gave no political support to the Colonial Society. The

Society for the Protection of German Immigrants to Texas, established in

Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-west, with Ma ...

in 1842 sought to expand the German settlements into a colony of "New Germany" (german: Neu Deutschland). About 7400 settlers were involved. The venture proved a complete failure. There was a constant lack of supplies and land and around half of the colonists died. The plan was definitively ended with the

annexation of Texas

The Texas annexation was the 1845 annexation of the Republic of Texas into the United States. Texas was admitted to the Union as the 28th state on December 29, 1845.

The Republic of Texas declared independence from the Republic of Mexico ...

by the United States in 1845.

Starting in the 1850s German commercial enterprises spread into areas that would later become German colonies in West Africa,

East Africa, the

Samoan Islands

The Samoan Islands ( sm, Motu o Sāmoa) are an archipelago covering in the central South Pacific, forming part of Polynesia and of the wider region of Oceania. Administratively, the archipelago comprises all of the Independent State of Samoa an ...

, the unexplored north-east quarter of

New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torr ...

with its adjacent islands, the

Douala

Douala is the largest city in Cameroon and its economic capital. It is also the capital of Cameroon's Littoral Region. Home to Central Africa's largest port and its major international airport, Douala International Airport (DLA), it is the com ...

delta in

Cameroon

Cameroon (; french: Cameroun, ff, Kamerun), officially the Republic of Cameroon (french: République du Cameroun, links=no), is a country in west-central Africa. It is bordered by Nigeria to the west and north; Chad to the northeast; the C ...

, and the mainland coast across from

Zanzibar

Zanzibar (; ; ) is an insular semi-autonomous province which united with Tanganyika in 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanzania. It is an archipelago in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of the mainland, and consists of many small islan ...

.

First state-sponsored colonial venture (1857–1862)

In 1857, the Austrian

frigate ''

Novara

Novara (, Novarese: ) is the capital city of the province of Novara in the Piedmont region in northwest Italy, to the west of Milan. With 101,916 inhabitants (on 1 January 2021), it is the second most populous city in Piedmont after Turin. It i ...

'' departed from

Triest

Trieste ( , ; sl, Trst ; german: Triest ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital city, and largest city, of the autonomous region of Friuli Venezia Giulia, one of two autonomous regions which are not subdivided into provi ...

on the Novara Expedition, which aimed to explore and take possession of the

Nicobar islands in the

Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by t ...

. The ''Novara'' arrived at the Nicobars in 1858, but the Austrians did not subsequently lay claim to the islands.

The next state-sponsored attempt to acquire a colony occurred in 1859, when

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

attempted to claim the island of

Formosa (modern

Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the nort ...

). Prussia had already sought the approval of the

French Emperor

Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

for the undertaking, since France was also seeking to acquire colonies in East Asia at that time. Since French interests focused on

Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

, not Formosa, Prussia could seek to acquire the island. A Prussian

naval expedition, which departed Germany at the end of 1859, was tasked with concluding trade treaties in Asia for Prussian and the other states of the Zollverein and with occupying Formosa. However, this task was not carried out, due to the limited strength of the expedition forces and because they did not wish to preclude a trade treaty with

Qing China. In a cabinet order of 6 January 1862, the expedition's ambassador,

Friedrich Albrecht zu Eulenburg

Count Friedrich Albrecht zu Eulenburg (29 June 1815 – 2 June 1881) was a Prussian diplomat and politician. He led the Eulenburg Expedition and secured the Prusso-Japanese Treaty of 24 January 1861, which was similar to other unequal treaties ...

was "released from carrying out the part of his task concerned with identification of overseas settlements suitable for Prussian settlement."

Despite this, one ship from the expedition, the ''

Thetis

Thetis (; grc-gre, Θέτις ), is a figure from Greek mythology with varying mythological roles. She mainly appears as a sea nymph, a goddess of water, or one of the 50 Nereids, daughters of the ancient sea god Nereus.

When described as ...

'' was sent to

Patagonia

Patagonia () refers to a geographical region that encompasses the southern end of South America, governed by Argentina and Chile. The region comprises the southern section of the Andes Mountains with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and g ...

in South America to investigate its prospects as a colony, since the Prussian naval command in particular were interested in the establishment of a naval strong point on the South American coast. The ''Thetis'' had already reached

Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

which the commander of the ship decided to return to Germany due to the exhaustion of the men after the year-long expedition and the need for repairs to the ship.

Bismarck's rejection of colonisation (1862–1871)

After the

Second Schleswig War

The Second Schleswig War ( da, Krigen i 1864; german: Deutsch-Dänischer Krieg) also sometimes known as the Dano-Prussian War or Prusso-Danish War was the second military conflict over the Schleswig-Holstein Question of the nineteenth century. ...

in 1864, colonialist societies in Prussia aspired to take possession of the

Nicobar islands which had previously been in

Danish

Danish may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Denmark

People

* A national or citizen of Denmark, also called a "Dane," see Demographics of Denmark

* Culture of Denmark

* Danish people or Danes, people with a Danish a ...

possession. For its part, Denmark unsuccessfully proposed to exchange the

Danish West Indies

The Danish West Indies ( da, Dansk Vestindien) or Danish Antilles or Danish Virgin Islands were a Danish colony in the Caribbean, consisting of the islands of Saint Thomas with ; Saint John ( da, St. Jan) with ; and Saint Croix with . The ...

for some of the lost territory in

Schleswig

The Duchy of Schleswig ( da, Hertugdømmet Slesvig; german: Herzogtum Schleswig; nds, Hartogdom Sleswig; frr, Härtochduum Slaswik) was a duchy in Southern Jutland () covering the area between about 60 km (35 miles) north and 70 km ...

in 1865. In 1866 and then again in 1876, Jamal ul-Azam, Sultan of the

Sulu Islands, located between

Borneo

Borneo (; id, Kalimantan) is the third-largest island in the world and the largest in Asia. At the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, in relation to major Indonesian islands, it is located north of Java, west of Sulawesi, and ea ...

and the Philippines, offered to place his islands under Prussian and then Imperial German control, but both times he was rebuffed. Ahmad ibn Fumo Bakari, the Sultan of

Wituland

Wituland (also Witu, Vitu, Witu Protectorate or Swahililand) was a territory of approximately in East Africa centered on the town of Witu just inland from Indian Ocean port of Lamu north of the mouth of the Tana River in what is now Kenya.

Hist ...

asked the Prussian traveller to establish a Prussian protectorate over his lands, but this request was never considered in Berlin.

In the 1867 constitution of the

North German Confederation

The North German Confederation (german: Norddeutscher Bund) was initially a German military alliance established in August 1866 under the leadership of the Kingdom of Prussia, which was transformed in the subsequent year into a confederated st ...

, article 4.1 declared "colonisation" as one of the areas under the "oversight of the Confederation", which remained the case in the

Imperial constitution established in 1871.

In 1867/8,

Otto von Bismarck dispatched the warship ''

Augusta'' to the

Caribbean to show the flag of the North German Confederation. At the personal urging of

Prince Adalbert, the commander of the

North German Federal Navy

The North German Federal Navy (''Norddeutsche Bundesmarine'' or ''Marine des Norddeutschen Bundes''), was the Navy of the North German Confederation, formed out of the Prussian Navy in 1867. It was eventually succeeded by the Imperial German Navy ...

, and without Bismarck's knowledge, the commander of the ''Augusta'', conducted negotiations with

José María Castro Madriz

José María Castro Madriz (1 September 1818 – 4 April 1892) was a Costa Rican lawyer, academic, diplomat, and politician. He served twice as President of Costa Rica, from 1847 to 1849, and from 1866 to 1868. On both occasions he was prevente ...

, President of

Costa Rica with a view to establishing a naval base at

Puerto Limón. Bismarck rejected the acquisition, due to the American

Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile act ...

. This desire to avoid antagonising the United States also led him to reject a

Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

offer to establish a naval base on the Dutch island of

Curaçao.

In 1868, Bismarck made his opposition to any colonial acquisitions clear in a letter to the Prussian

Minister of War

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in som ...

Albrecht von Roon

Albrecht Theodor Emil Graf von Roon (; 30 April 180323 February 1879) was a Prussian soldier and statesman. As Minister of War from 1859 to 1873, Roon, along with Otto von Bismarck and Helmuth von Moltke, was a dominating figure in Prussia's ...

:

He also repeatedly stated "... I am no man for colonies"

The policy of the North German Confederation at this time focussed on the acquisition of individual

naval base

A naval base, navy base, or military port is a military base, where warships and naval ships are docked when they have no mission at sea or need to restock. Ships may also undergo repairs. Some naval bases are temporary homes to aircraft that u ...

s, not colonies. With these it would be able to use

gunboat diplomacy

In international politics, the term gunboat diplomacy refers to the pursuit of foreign policy objectives with the aid of conspicuous displays of naval power, implying or constituting a direct threat of warfare should terms not be agreeable to t ...

to protect the global trade interests of the Confederation through a kind of informal imperialism. In 1867, it was decided to establish five overseas bases. Accordingly, in 1868, land was bought in

Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of T ...

in

Japan for a German naval hospital, which remained in operation until 1911. In 1869 the "East Asian Station" (''Ostasiatische Station'') was established there by the navy as the first overseas base, with a permanent presence of German warships. Until the German Empire's acquisition of

Tsingtao

Qingdao (, also spelled Tsingtao; , Mandarin: ) is a major city in eastern Shandong Province. The city's name in Chinese characters literally means " azure island". Located on China's Yellow Sea coast, it is a major nodal city of the One Belt ...

in China as a military port in 1897, Yokohama remained the base of the German fleet in East Asia. It later proved useful following the acquisition of colonies in the Pacific and in

Kiaochow

The Jiaozhou Bay (; german: Kiautschou Bucht, ) is a bay located in the prefecture-level city of Qingdao (Tsingtau), China.

The bay has historically been romanized as Kiaochow, Kiauchau or Kiao-Chau in English and Kiautschou in German.

Geo ...

.

In 1869, the

Rhenish Missionary Society

The Rhenish Missionary Society (''Rhenish'' of the river Rhine) was one of the largest Protestant missionary societies in Germany. Formed from smaller missions founded as far back as 1799, the Society was amalgamated on 23 September 1828, and it ...

, which had been established in southwestern Africa for several decades asked

King William of Prussia for protection and suggested the establishment of a naval station at

Walvis Bay

Walvis Bay ( en, lit. Whale Bay; af, Walvisbaai; ger, Walfischbucht or Walfischbai) is a city in Namibia and the name of the bay on which it lies. It is the second largest city in Namibia and the largest coastal city in the country. The ci ...

. William was very interested in this suggestion, but the matter was forgotten following the outbreak of the

Franco-Prussian War.

Debate and tentative steps under the new German Empire (1871–1878)

A French proposal after the Franco-Prussian War to hand over the French colony of

Cochinchina

Cochinchina or Cochin-China (, ; vi, Đàng Trong (17th century - 18th century, Việt Nam (1802-1831), Đại Nam (1831-1862), Nam Kỳ (1862-1945); km, កូសាំងស៊ីន, Kosăngsin; french: Cochinchine; ) is a historical exony ...

instead of

Alsace–Lorraine, was rejected by Bismarck and a majority of the delegates in the North German

Reichstag in 1870. After

German Unification

The unification of Germany (, ) was the process of building the modern German nation state with federal features based on the concept of Lesser Germany (one without multinational Austria), which commenced on 18 August 1866 with adoption of t ...

in 1871, Bismarck maintained his earlier position. During the 1870s, colonialist propaganda achieved increasing public profile in Germany. In 1873, the was established, which considered exploration of Africa its main function. In 1878 the foundation of the was established, which sought to acquire colonies for Germany, and in 1881 was founded, which included the "acquisition of agricultural and commercial colonies for the German Empire" in its founding statute. In 1882, the first was established, which was a

lobby group for colonialist propaganda. In 1887, the competing

Society for German Colonization

The Society for German Colonization (german: Gesellschaft für Deutsche Kolonisation, GfdK) was founded on 28 March 1884 in Berlin by Carl Peters. Its goal was to accumulate capital for the acquisition of German colonial territories in overseas co ...

was established with the goal of actually undertaking colonisation. The two societies merged in 1887 into the

German Colonial Society

The German Colonial Society (german: Deutsche Kolonialgesellschaft) (DKG) was a German organisation formed on 19 December 1887 to promote German colonialism. The Society was formed through the merger of the (; established in 1882 in Frankfurt) an ...

. Generally, four arguments were advanced in favour of the acquisition of colonies:

* Once developed, colonies would offer

captive market

Captive markets are markets where the potential consumers face a severely limited number of competitive suppliers; their only choices are to purchase what is available or to make no purchase at all. The term therefore applies to any market where ...

s for German industrial products and thus provide a substitute for the decreasing consumer demand in Germany following the

Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

.

* Colonies would provide a space for the

German diaspora, so that they would not be lost to the nation. Since the diaspora had mainly emigrated to English-speaking areas up to this point, the prominent colonialist held that if they were allowed to leave, the Anglo-Saxon race would irretrievably overtake the German one demographically.

* Germany had, as the theologian put it, a "cultural mission" to spread its supposedly superior culture across the globe.

* The acquisition of colonies provided a possible solution for the

Social Question - workers would commit themselves to an absorbing national task and abandon

social democracy

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote s ...

. Through this and through the emigration of the overly rebellious masses to the colonies the internal unity of the nation would be strengthened.

Moreover, German public opinion in the late-19th century viewed colonial acquisitions as a true indication of having achieved full nationhood, and eventually arrived at an understanding that prestigious African and Pacific colonies went hand-in-hand with dreams of a

High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...

.

Bismarck remained opposed to these arguments and preferred an informal commercial imperialism, in which German companies carried out profitable trade with areas outside Europe and made economic inroads without the occupation of territories or the construction of states. Bismarck and many deputies in the

''Reichstag'' had no interest in making colonial conquests merely to acquire square miles of territory.

As a result, the first colonial enterprises abroad were extremely hesitant: a was signed in 1876, which provided for the establishment of a coal station on the

Tonga

Tonga (, ; ), officially the Kingdom of Tonga ( to, Puleʻanga Fakatuʻi ʻo Tonga), is a Polynesian country and archipelago. The country has 171 islands – of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in ...

n island of

Vavaʻu

Vavau is an island group, consisting of one large island ( ʻUtu Vavaʻu) and 40 smaller ones, in Tonga. It is part of Vavaʻu District, which includes several other individual islands. According to tradition, the Maui god created both Tongata ...

, guaranteeing all usage rights of the specified area to the German Empire, but leaving the King of Tonga's sovereignty untouched. No actual colonisation occurred. On 16 July 1878, he commander of the

SMS ''Ariadne'', occupied

Falealili and

Saluafata on the

Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands ( Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands ( Manono and Apolima); ...

n island of

Upolo "in the name of the Empire". The German occupation of these places was revoked in January 1879 with the conclusion of a treaty of friendship between th local rulers and Germany. On 19 November 1878, von Werner established a treaty with the leaders of

Jaluit Atoll

Jaluit Atoll ( Marshallese: , , or , ) is a large coral atoll of 91 islands in the Pacific Ocean and forms a legislative district of the Ralik Chain of the Marshall Islands. Its total land area is , and it encloses a lagoon with an area of . Mos ...

and the

Ralik

The Ralik Chain ( Marshallese: , ) is a chain of islands within the island nation of the Marshall Islands. Ralik means "sunset". It is west of the Ratak Chain. In 1999 the total population of the Ralik islands was 19,915. Christopher Loeak, who b ...

islands of Lebon and Letahalin, granting privileges like the exclusive right to establish a coal station. An official German colony in the

Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands ( mh, Ṃajeḷ), officially the Republic of the Marshall Islands ( mh, Aolepān Aorōkin Ṃajeḷ),'' () is an independent island country and microstate near the Equator in the Pacific Ocean, slightly west of the Intern ...

was only established in 1885. Von Werner also acquired a harbour on the islands of

Makada and

Mioko in the

Duke of York Islands

The Duke of York Islands (formerly german: link=no, Neu lauenburg) are a group of islands located in East New Britain Province, Papua New Guinea. They are found in StGeorge's Channel between New Britain and New Ireland islands and form part o ...

in December 1878, which would become a component part of the future protectorate of

German New Guinea

German New Guinea (german: Deutsch-Neu-Guinea) consisted of the northeastern part of the island of New Guinea and several nearby island groups and was the first part of the German colonial empire. The mainland part of the territory, called , ...

in 1884. On 20 April 1879, the commander of the

SMS ''Bismarck'', and the German Consul for the South Seas Islands, Gustav Godeffroy Junior established a treaty of commerce and friendship with "the government" of

Huahine

Huahine is an island located among the Society Islands, in French Polynesia, an overseas territory of France in the Pacific Ocean. It is part of the Leeward Islands group ''(Îles sous le Vent).'' At the 2017 census it had a population of 6,075. ...

, one of the

Society Islands

The Society Islands (french: Îles de la Société, officially ''Archipel de la Société;'' ty, Tōtaiete mā) are an archipelago located in the South Pacific Ocean. Politically, they are part of French Polynesia, an overseas country of the ...

, which granted the German fleet the right to anchor at all harbours on the island, among other things.

Establishment of the empire (1884–1890)

Although Bismarck "remained as contemptuous of all colonial dreams as ever", in 1884, he consented to the acquisition of colonies by the German Empire, in order to protect trade, safeguard raw materials and export-markets and to take advantage of opportunities for capital investment, among other reasons. In the very next year Bismarck shed personal involvement when "he abandoned his colonial drive as suddenly and casually as he had started it" – as if he had committed an error in judgment that could confuse the substance of his more significant policies.

[Crankshaw, p. 397.] "Indeed, in 1889,

ismarcktried to give

German South-West Africa

German South West Africa (german: Deutsch-Südwestafrika) was a colony of the German Empire from 1884 until 1915, though Germany did not officially recognise its loss of this territory until the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. With a total area of ...

away to the British. It was, he said, a burden and an expense, and he would like to saddle someone else with it."

Following 1884, Germany invaded several territories in Africa:

German East Africa (including present-day

Burundi,

Rwanda, and the mainland part of

Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands ...

);

German South-West Africa

German South West Africa (german: Deutsch-Südwestafrika) was a colony of the German Empire from 1884 until 1915, though Germany did not officially recognise its loss of this territory until the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. With a total area of ...

(present-day

Namibia

Namibia (, ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and ea ...

),

German Cameroon

Kamerun was an African colony of the German Empire from 1884 to 1916 in the region of today's Republic of Cameroon. Kamerun also included northern parts of Gabon and the Congo with western parts of the Central African Republic, southwestern ...

(including parts of present-day

Cameroon

Cameroon (; french: Cameroun, ff, Kamerun), officially the Republic of Cameroon (french: République du Cameroun, links=no), is a country in west-central Africa. It is bordered by Nigeria to the west and north; Chad to the northeast; the C ...

,

Gabon

Gabon (; ; snq, Ngabu), officially the Gabonese Republic (french: République gabonaise), is a country on the west coast of Central Africa. Located on the equator, it is bordered by Equatorial Guinea to the northwest, Cameroon to the nort ...

,

Congo,

Central African Republic

The Central African Republic (CAR; ; , RCA; , or , ) is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Chad to the north, Sudan to the northeast, South Sudan to the southeast, the DR Congo to the south, the Republic of th ...

,

Chad and

Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

); and

Togoland

Togoland was a German Empire protectorate in West Africa from 1884 to 1914, encompassing what is now the nation of Togo and most of what is now the Volta Region of Ghana, approximately 90,400 km2 (29,867 sq mi) in size. During the period kn ...

(present-day

Togo

Togo (), officially the Togolese Republic (french: République togolaise), is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Ghana to the west, Benin to the east and Burkina Faso to the north. It extends south to the Gulf of Guinea, where its c ...

and parts of

Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and To ...

). Germany was also active in the Pacific, annexing a series of islands that would be called

German New Guinea

German New Guinea (german: Deutsch-Neu-Guinea) consisted of the northeastern part of the island of New Guinea and several nearby island groups and was the first part of the German colonial empire. The mainland part of the territory, called , ...

(part of present-day

Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea (abbreviated PNG; , ; tpi, Papua Niugini; ho, Papua Niu Gini), officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea ( tpi, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niugini; ho, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niu Gini), is a country i ...

and several nearby island groups). The northeastern region of the island of New Guinea was called Kaiser-Wilhelmsland; the Bismarck Archipelago to the islands' east also contained two larger islands named New Mecklenburg and New Pomerania. They also acquired the Northern Solomon Islands. These islands were given the status of protectorate.

Bismarck moves towards a colonial policy (1878–1883)

The shift in Bismarck's policy on the acquisition of colonies began as part of his 1878 policy on the protection of the German economy from foreign competition. The beginning of his colonial policy in connection with the Schutzzollpolitik was the acquisition of

Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands ( Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands ( Manono and Apolima); ...

, where there were significant German economic interests. In June 1879, as

Imperial Chancellor, he acknowledged the "Treaty of Friendship" agreed between the Samoan chiefs and the German consul in Samoa in January 1879, with the result that the consul assumed control of the administration of the city of

Apia

Apia () is the capital and largest city of Samoa, as well as the nation's only city. It is located on the central north coast of Upolu, Samoa's second-largest island. Apia falls within the political district (''itūmālō'') of Tuamasaga.

...

on the island of

Upolo, along with the consuls of Britain and America. In the 1880s, Bismarck would unsuccessfully attempt to annex Samoa several times. The western Samoan islands, which included Apia, the main city, became a German colony in 1899.

In April 1880, Bismarck actively intervened in domestic politics in favour of colonial matters, when he presented the

Samoa Bill to the

Reichstag. It had been endorsed by the

Federal Council, but was rejected by the Reichstag. The bill would have provided German financial support to a private German colonial trade company that had fallen into difficulties.

In May 1880, Bismarck asked the banker

Adolph von Hansemann

Adolph von Hansemann (27 July 1826 – 9 December 1903) was an Imperial German businessman and banker.

Life

Born in Aachen in 1826 to German banker and railroad entrepreneur David Hansemann, Adolph Hansemann developed an early interest in busin ...

to produce a report on German colonial goals in the Pacific and the possibility of enforcing them. Hansemann submitted his ''Memorandum on Colonial Aspirations in the South Seas'' to Bismarck in September of the same year. The proposed territorial acquisitions were almost all taken or claimed as colonies four years later. Those Pacific territories that were claimed in 1884 but not taken were finally brought under German colonial administration in 1899. Significantly, Hausemann was a founding member of the

New Guinea Consortium for the acquisition of colonies in

New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torr ...

and the Pacific in 1882.

In November 1882, the

Bremen-based tobacco merchant

Adolf Lüderitz

Franz Adolf Eduard Lüderitz (16 July 1834 – end of October 1886) was a German merchant and the founder of German South West Africa, Imperial Germany's first colony. The coastal town of Lüderitz, located in the ǁKaras Region of southern N ...

contacted the

Foreign Office and requested protection for a trade station south of

Walvis Bay

Walvis Bay ( en, lit. Whale Bay; af, Walvisbaai; ger, Walfischbucht or Walfischbai) is a city in Namibia and the name of the bay on which it lies. It is the second largest city in Namibia and the largest coastal city in the country. The ci ...

on the southwest African coast. In February and November 1883, he asked the British government whether the United Kingdom would provide protection to Lüderitz's trade station. Both times the British government refused.

From March 1883,

Adolph Woermann, a

Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

bulkgoods trader, shipowner, and member of the

Hamburg Chamber of Commerce, engaged in extremely confidential negotiations with the Foreign Office, which was headed by Bismarck, for the acquisition of a colony in

West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, M ...

. The reason for this was the fear of tariffs that Hamburg traders might have to pay if the whole of West Africa were to come under British or French control. Finally a secret request from the Chamber of Commerce to Bismarck for the establishment of a colony in West Africa was submitted to Bismarck on 6 July 1883, stating that "through such acquisitions, German trade in Trans-Atlantic lands could only be given a firmer position and a surer support, while without political protection trade cannot now thrive and progress."

After this, in March 1883, the

Sierra Leone Convention between the United Kingdom and France was published, in which the two countries'

spheres of interest

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal al ...

were laid out without consideration of other trading nations. In response the German government asked the senates of the cities of

Lübeck

Lübeck (; Low German also ), officially the Hanseatic City of Lübeck (german: Hansestadt Lübeck), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 217,000 inhabitants, Lübeck is the second-largest city on the German Baltic coast and in the state ...

, Bremen, and Hamburg for their opinions. In their answer, the Hamburg merchants demanded the acquisition of colonies in West Africa. In December 1883, Bismarck let Hamburg known that an Imperial commissioner would be sent to West Africa to secure the safety of German trade and to conclude a treaty with "independent Negro states". A warship, the

SMS ''Sophie'' would be sent to provide military protection. Additionally, Bismarck requested suggestions on this plan and asked for Adolph Woermann's advice personally on what instructions should be given to the Imperial commissioner. In March 1884,

Gustav Nachtigal

Gustav Nachtigal (; born 23 February 1834 – 20 April 1885) was a German military surgeon and explorer of Central and West Africa. He is further known as the German Empire's consul-general for Tunisia and Commissioner for West Africa. His missio ...

was named as the Imperial Commissioner for the West African Coast and set sail for West Africa in the

SMS ''Möwe''.

Colonisation under Bismarck (1884–1888)

The year 1884 marks the beginning of actual German colonial acquisitions, building on the overseas possessions and rights that had been acquired for the German Empire since 1876. In one year, Germany's holdings became the third-largest colonial empire, after the

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

and

French empires. Following the British model, Bismarck placed many possessions of German merchants under the protection of the German empire. He took advantage of a period of foreign peace to begin the "colonial experiment", which he remained sceptical of. The transition to official acceptance of colonialism and to colonial government thus occurred during the last quarter of Bismarck's tenure of office.

[Miller, p. 7]

First, Adolf Lüderitz's trading post in the Bay of Angara Pequena ('

Lüderitz Bay') and the surrounding hinterland ('') was placed under the protection of the German Empire in April 1884 as

German South West Africa

German South West Africa (german: Deutsch-Südwestafrika) was a colony of the German Empire from 1884 until 1915, though Germany did not officially recognise its loss of this territory until the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. With a total area of ...

. In July,

Togoland

Togoland was a German Empire protectorate in West Africa from 1884 to 1914, encompassing what is now the nation of Togo and most of what is now the Volta Region of Ghana, approximately 90,400 km2 (29,867 sq mi) in size. During the period kn ...

and

Adolph Woermann's possessions in

Cameroon

Cameroon (; french: Cameroun, ff, Kamerun), officially the Republic of Cameroon (french: République du Cameroun, links=no), is a country in west-central Africa. It is bordered by Nigeria to the west and north; Chad to the northeast; the C ...

followed, then the northeastern section of New Guinea ('

Kaiser-Wilhelmsland

Kaiser-Wilhelmsland ("Emperor William's Land") formed part of German New Guinea (german: Deutsch-Neuguinea), the South Pacific protectorate of the German Empire. Named in honour of Wilhelm I, who reigned as German Emperor () from 1871 to 1888, ...

') and the neighbouring islands ('the

Bismarck Archipelago'). In January 1885, the German flag was raised at

Kapitaï and Koba on the west African coast. In February, imperialist and "man-of-action"

Carl Peters

Carl Peters (27 September 1856 – 10 September 1918), was a German colonial ruler, explorer, politician and author and a major promoter of the establishment of the German colony of East Africa (part of the modern republic Tanzania).

Life

H ...

accumulated vast tracts of land for his

Society for German Colonization

The Society for German Colonization (german: Gesellschaft für Deutsche Kolonisation, GfdK) was founded on 28 March 1884 in Berlin by Carl Peters. Its goal was to accumulate capital for the acquisition of German colonial territories in overseas co ...

, "emerging from the bush with X-marks

ffixed by unlettered tribal chiefson documents ... for some 60 thousand square miles of the Zanzibar Sultanate's mainland property." which became

German East Africa. Such exploratory missions required security measures that could be solved with small private, armed contingents recruited mainly in the Sudan and usually led by adventurous former military personnel of lower rank. Brutality, hanging and flogging prevailed during these land-grab expeditions under Peters' control as well as others as no-one "held a monopoly in the mistreatment of Africans", and in April 1885, the brothers

Clemens Clemens is both a Late Latin masculine given name and a surname meaning "merciful". Notable people with the name include:

Surname

* Adelaide Clemens (born 1989), Australian actress.

* Andrew Clemens (b. 1852 or 1857–1894), American folk artist

* ...

and

Gustav Denhardt acquired

Wituland

Wituland (also Witu, Vitu, Witu Protectorate or Swahililand) was a territory of approximately in East Africa centered on the town of Witu just inland from Indian Ocean port of Lamu north of the mouth of the Tana River in what is now Kenya.

Hist ...

in modern

Kenya

)

, national_anthem = " Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Nairobi

...

. With this, the first wave of German colonial acquisitions was largely completed.

The raising of German flags on Pacific islands claimed by

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

between August and October 1885 sparked the

Carolines Crisis, in which Germany ultimately backed down.

In October 1885, the

Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands ( mh, Ṃajeḷ), officially the Republic of the Marshall Islands ( mh, Aolepān Aorōkin Ṃajeḷ),'' () is an independent island country and microstate near the Equator in the Pacific Ocean, slightly west of the Intern ...

were also claimed and finally several of the

Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands in Oceania, to the east of Papua New Guinea and north-west of Vanuatu. It has a land area of , and a population of approx. 700,000. Its capit ...

in October 1886. In 1888, Germany ended the

civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

on

Nauru and annexed the island.

Causes

The causes of Bismarck's sudden shift to a policy of colonial acquisition remain a matter of controversy among historians. There are two dominant schools of thought: one which focusses on German domestic politics and one which focusses on foreign affairs.

In terms of internal politics, the key aspect is the public pressure which led to the development of a "Colonial fever" (''Kolonialfieber'') among the German populace. Although the colonial movement was not very strong institutionally, it succeeded in bringing its position into the public debate. A memorandum authored by Adolph Woermann and sent to Bismarck by the Hamburg Chamber of Commerce on 6 July 1883 is considered to have been particularly important in this respect. The approach of the

1884 German federal election and Bismarck's desire to strengthen his own position and bind the

National Liberal Party, which supported colonialism, to himself, have also been proposed as domestic factors in the adoption of the colonial policy.

Hans-Ulrich Wehler

Hans-Ulrich Wehler (September 11, 1931 – July 5, 2014) was a German left-liberal historian known for his role in promoting social history through the " Bielefeld School", and for his critical studies of 19th-century Germany.

Life

Wehler was bo ...

advanced the

social imperialism

As a political term, social imperialism is the political ideology of people, parties, or nations that are, according to Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin, "socialist in words, imperialist in deeds". In academic use, it refers to governments that enga ...

thesis, which holds that the colonial expansion served to "divert" social tensions created by economic crisis to the foreign sphere and helped to reinforce Bismarck's authority. The so-called "Crown-prince thesis" holds that Bismarck was attempting to deliberately worsen the German relationship with the United Kingdom before the anticipated succession of the "

anglophile

An Anglophile is a person who admires or loves England, its people, its culture, its language, and/or its various accents.

Etymology

The word is derived from the Latin word ''Anglii'' and Ancient Greek word φίλος ''philos'', meaning "frien ...

"

Frederick III to the German throne in order to prevent him from instituting liberal English-style policies.

In terms of foreign policy, the decision to colonise is seen as an extension of the concept of the European

balance of power to a global context. By participating in the

Scramble for Africa would also reinforce its position as one of the

Great Power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power in ...

s. Improving relations with France through a "colonial entente" that would divert French attention from

revanchism

Revanchism (french: revanchisme, from ''revanche'', "revenge") is the political manifestation of the will to reverse territorial losses incurred by a country, often following a war or social movement. As a term, revanchism originated in 1870s Fr ...

related to

Alsace-Lorraine, which had been annexed by Germany in 1871, has also been seen as a motive.

Company land acquisitions and stewardship

It is no longer believed that the initiation of colonial expansion represented a radical reversal of Bismarck's politics. The liberal-imperialist ideal of an overseas policy grounded in private economic initiatives, which he had held from the beginning, was not changed much by placing German merchants' possessions under the protection of the Empire.

As Bismarck was converted to the colonial idea by 1884, he favoured "chartered company" land management rather than establishment of colonial government due to financial considerations. He used official letters of protection to transfer the commerce and administration of individual "German protectorates" to private companies. The administration of these areas was assigned to the

German East Africa Company (1885–1890), the German Witu Company (1887-1890), the

German New Guinea Company (1885–1899), and the in the Marshall Islands (1888–1906). Bismarck would have liked the

German colonies in west Africa and

southwest Africa

South West Africa ( af, Suidwes-Afrika; german: Südwestafrika; nl, Zuidwest-Afrika) was a territory under South African administration from 1915 to 1990, after which it became modern-day Namibia. It bordered Angola (Portuguese colony before 1 ...

to be administered in this way as well, but neither the nor the Syndicate for West Africa were willing to take on the role.

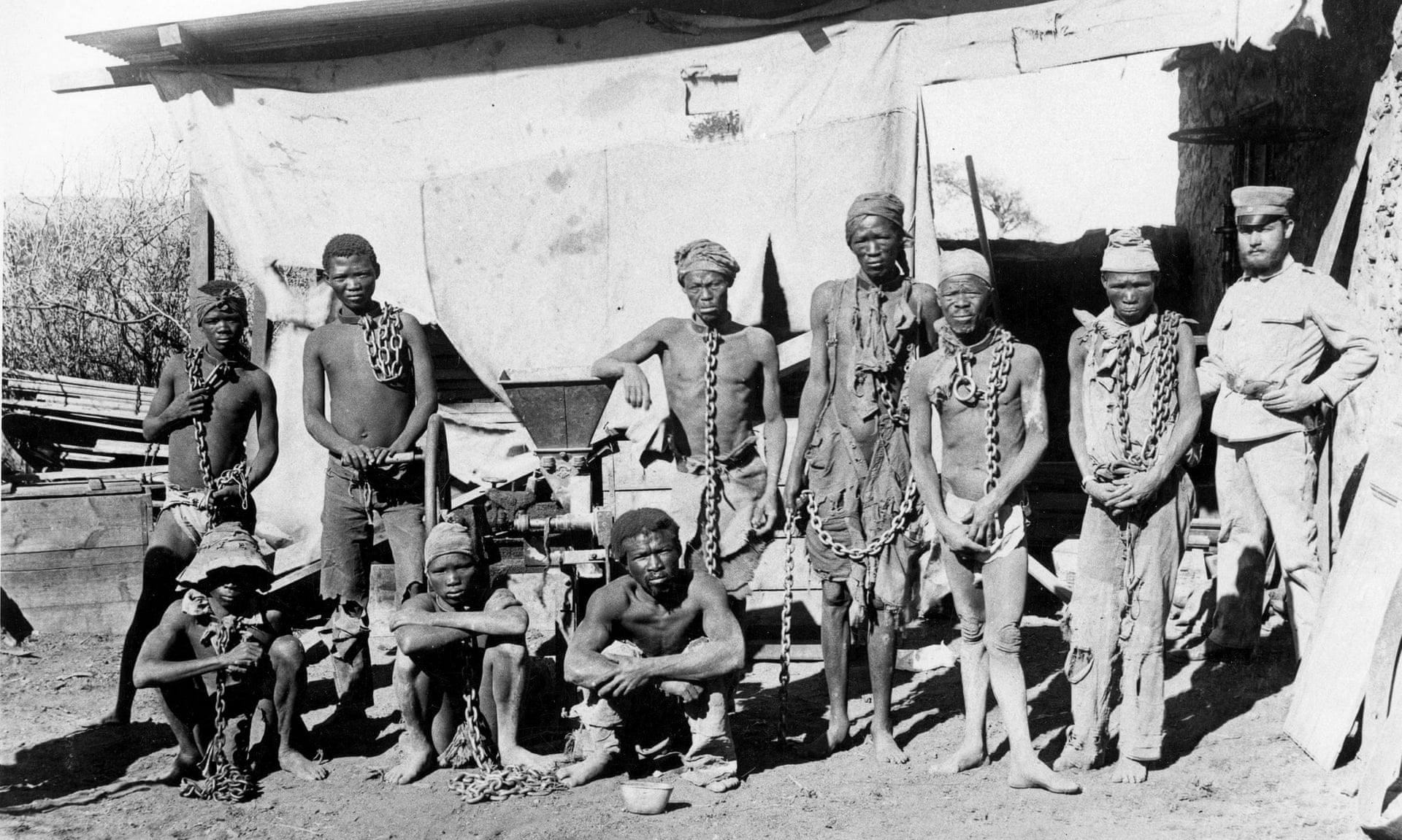

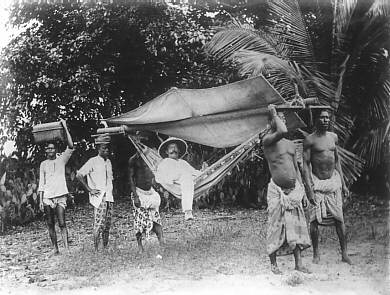

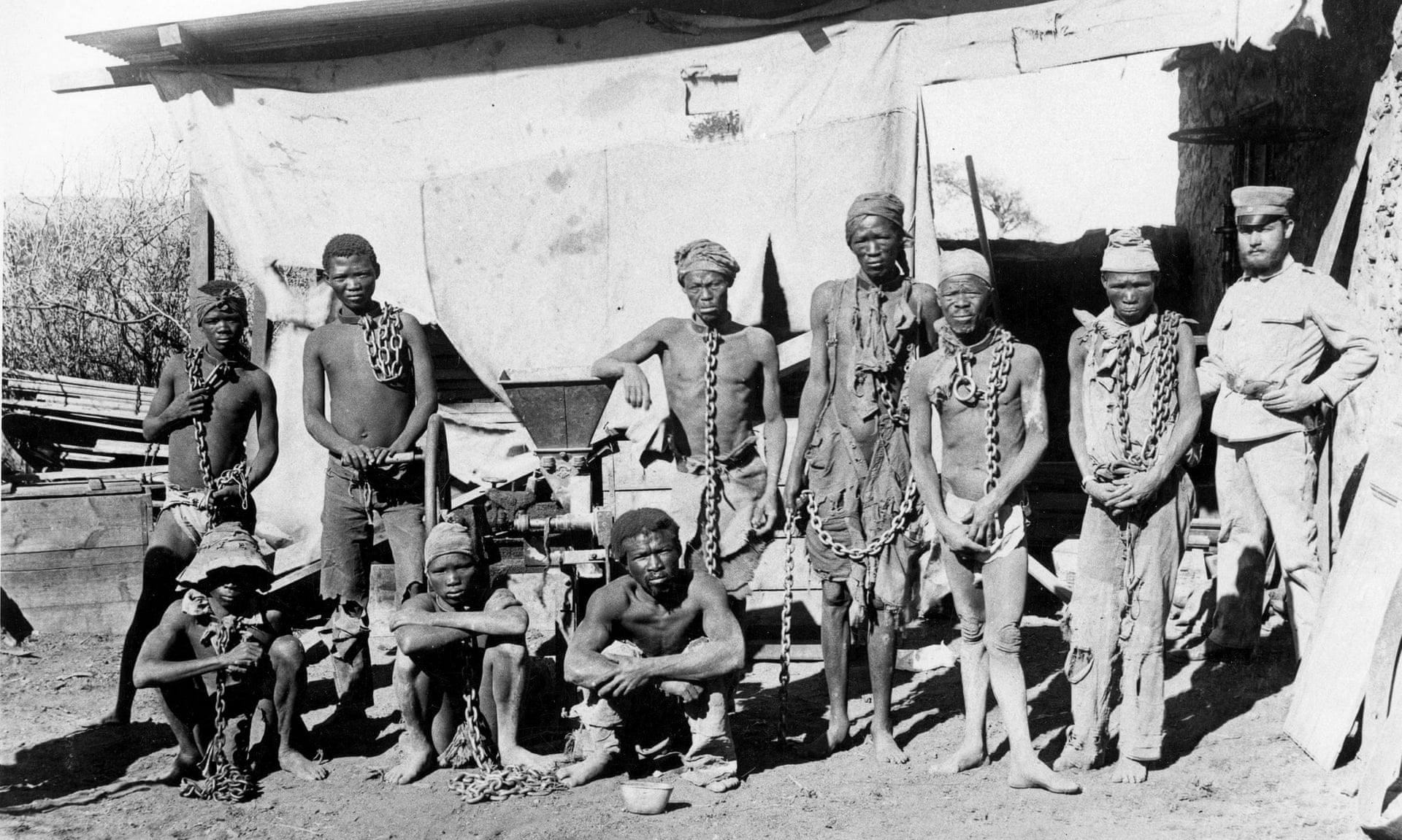

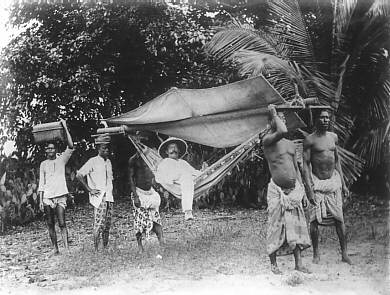

These areas were brought into German possession with extremely

unequal treaties

Unequal treaty is the name given by the Chinese to a series of treaties signed during the 19th and early 20th centuries, between China (mostly referring to the Qing dynasty) and various Western powers (specifically the British Empire, France, the ...

following demonstrations of military power. Indigenous rulers ceded vast areas, which they often had no legal claim to, in exchange for vague promises of protection and laughably low purchase prices. Details of the treaties often remained unclear to them due to the language barrier. They engaged with these deals, however, because the long negotiations with the colonisers and the ritual act of signing a treaty enormously enhanced their authority. These treaties were approved by the German government, which granted complete authority without oversight to the colonial companies, while retaining for itself only ultimate

sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

and a few unspecified rights to intervene. In this way, state financial and administrative engagement with the colonies was kept to a minimum.

However, this strategy failed within a few years. The poor financial situation of almost all of the "protectorates" as well as the precarious security situation (indigenous revolts broke out in South West Africa and East Africa in 1888, while in Cameroon and Togo border conflicts with the neighbouring British colonies were feared, and in general the demands of efficient administration overwhelmed the colonial companies) compelled Bismarck and his successors to implement direct and formal rule in all the colonies.

Although temperate zone cultivation flourished, the demise and often failure of tropical low-land enterprises contributed to changing Bismarck's view. He reluctantly acquiesced to pleas for help to deal with revolts and armed hostilities by often powerful

rulers

A ruler, sometimes called a rule, line gauge, or scale, is a device used in geometry and technical drawing, as well as the engineering and construction industries, to measure distances or draw straight lines.

Variants

Rulers have long ...

whose lucrative slaving activities seemed at risk. German native military forces initially engaged in dozens of punitive expeditions to apprehend and punish freedom fighters, at times with British assistance. The author Charles Miller offers the theory that the Germans had the handicap of trying to colonise African areas inhabited by aggressive tribes, whereas their colonial neighbours had more docile peoples to contend with. At that time, the German penchant for giving muscle priority over patience contributed to continued unrest. Several of the African colonies remained powder kegs throughout this phase (and beyond).

Halt to colonial acquisitions (1888–1890)

After 1885, Bismarck opposed further colonial acquisitions and maintained his policy focus on maintaining good relationships with the Great Powers of England and France. In 1888, when the journalist

Eugen Wolf

Eugen Wolf (born 24 January 1850 in Kirchheimbolanden; died 10 May 1912 in Munich) was a German journalist and traveller.

Life

He devoted most of his life to travelling, first within Europe and then to the New World, Africa, and the Far East. In ...

urged him to acquire further colonies for Germany, so that it would not fall behind in the

scramble

Scramble, Scrambled, or Scrambling may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Games

* ''Scramble'' (video game), a 1981 arcade game

Music Albums

* ''Scramble'' (album), an album by Atlanta-based band the Coathangers

* ''Scrambles'' (album)

...

with the other Great Powers for colonies, which he understood in a

social Darwinian sense, Bismarck replied that his priority was rather the protection of the recently won national unity, which he considered to be under threat due to Germany's central location:

In 1889, Bismarck considered withdrawing Germany from colonial policy, wishing to entirely end Germany activities in East Africa and Samoa, according to eyewitnesses. It was further reported that Bismarck wanted nothing more to do with the administration of the colonies and intended to hand them over to the admiralty. In May 1889, Bismarck offered to sell the German possessions in Africa to the Italian Prime Minister,

Francesco Crispi – who countered with an offer to sell

Italy's colonies to Germany.

Bismarck also found the colonies useful as bargaining chips. Thus, at the

Congo Conference

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, also known as the Congo Conference (, ) or West Africa Conference (, ), regulated European colonisation and trade in Africa during the New Imperialism period and coincided with Germany's sudden emergence ...

held in Berlin from 1884 to 1885, he divied Africa up between the Great Powers. In 1884, a treaty was concluded in the name of Lüderitz with the

Zulu king

Dinuzulu

Dinuzulu kaCetshwayo (1868 – 18 October 1913, commonly misspelled Dinizulu) was the king of the Zulu nation from 20 May 1884 until his death in 1913.

He succeeded his father Cetshwayo, who was the last king of the Zulus to be officially reco ...

, which would have given Germany a claim to

St Lucia Bay in Zululand. However, the claim was dropped as part of a concession to Britain in May 1885, along with a claim to

Pondoland

Pondoland or Mpondoland (Xhosa: ''EmaMpondweni''), is a natural region on the South African shores of the Indian Ocean. It is located in the coastal belt of the Eastern Cape province. Its territory is the former Mpondo Kingdom of the Mpondo peop ...

. Also in 1885, Germany waived its claim to the west African territories of

Kapitaï and Koba and

Mahinland, in favour of France and Britain respectively. In 1886, Germany and Britain agreed on the boundaries of their spheres of interest in East Africa.

After Bismarck had ended the policy of colonial acquisition in March 1890, he concluded the

Heligoland–Zanzibar Treaty

The Heligoland–Zanzibar Treaty (german: Helgoland-Sansibar-Vertrag; also known as the Anglo-German Agreement of 1890) was an agreement signed on 1 July 1890 between the German Empire and the United Kingdom.

The accord gave Germany control of ...

with Britain on 1 July 1890, in which Germany renounced all remaining claims north of German East Africa. In this way, he established a balance with Great Britain. Renouncing the

German claims to the Somali coast between

Burgabo and

Alula

The alula , or bastard wing, (plural ''alulae'') is a small projection on the anterior edge of the wing of modern birds and a few non-avian dinosaurs. The word is Latin and means "winglet"; it is the diminutive of ''ala'', meaning "wing". The al ...

also improved relations with Italy, one of Germany's partners in the

Triple Alliance. In exchange for this, Germany acquired the

Caprivi Strip

The Caprivi Strip, also known simply as Caprivi, is a geographic salient protruding from the northeastern corner of Namibia. It is surrounded by Botswana to the south and Angola and Zambia to the north. Namibia, Botswana and Zambia meet at a s ...

, which extended German South West Africa east to the

Zambezi River

The Zambezi River (also spelled Zambeze and Zambesi) is the fourth-longest river in Africa, the longest east-flowing river in Africa and the largest flowing into the Indian Ocean from Africa. Its drainage basin covers , slightly less than hal ...

(it was hoped that the river would enable overland transport between German South West Africa and German East Africa). In these circumstances, further German colonial aspirations in South East Africa were brought to an end.

German interest in African colonies was accompanied by a growth of scholarly interest in Africa. In 1845, the orientalist

Heinrich Leberecht Fleischer

Heinrich Leberecht Fleischer (21 February 1801 – 10 February 1888) was a German Orientalist.

Biography

He was born at Schandau, Saxony. From 1819 to 1824, he studied theology and Oriental languages at Leipzig, subsequently continuing his stud ...

of

Leipzig University

Leipzig University (german: Universität Leipzig), in Leipzig in Saxony, Germany, is one of the world's oldest universities and the second-oldest university (by consecutive years of existence) in Germany. The university was founded on 2 December ...

and others founded the

Deutsche Morgenländische Gesellschaft

The Deutsche Morgenländische Gesellschaft (, ''German Oriental Society''), abbreviated DMG, is a scholarly organization dedicated to Oriental studies, that is, to the study of the languages and cultures of the Near East and the Far East, the broa ...

. The linguist

Hans Stumme, also of Leipzig, researched African languages. Leipzig established a professorship of Anthropology, Ethnography, and Pre-history in 1901 (

Karl Weule, who established an ethnological and

biological determinist school of African research) and a professorship for "Colonial geography and colonial policy" in 1915. The researcher

Hans Meyer was director of the "Institute for Colonial Geography". In 1919, the Seminar for Colonial geography and colonial policy" was established.

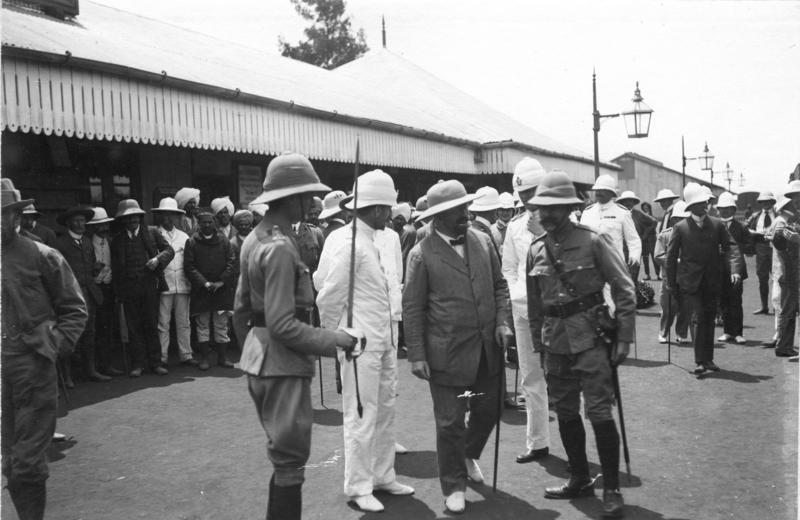

The empire under Kaiser Wilhelm (1890–1914)

Kaiser

Wilhelm II

, house = Hohenzollern

, father = Frederick III, German Emperor

, mother = Victoria, Princess Royal

, religion = Lutheranism (Prussian United)

, signature = Wilhelm II, German Emperor Signature-.svg

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor ...

(1888-1918) was keen for Germany to expand its colonial holdings. Bismarck's immediate successor in 1890,

Leo von Caprivi

Georg Leo Graf von Caprivi de Caprara de Montecuccoli (English: ''Count George Leo of Caprivi, Caprara, and Montecuccoli''; born Georg Leo von Caprivi; 24 February 1831 – 6 February 1899) was a German general and statesman who served as the cha ...

, was willing to maintain the colonial burden of what already existed, but opposed new ventures. Others who followed, especially

Bernhard von Bülow, as foreign minister and chancellor, sanctioned the acquisition of further Pacific Ocean colonies and provided substantial treasury assistance to existing protectorates to employ administrators, commercial agents, surveyors, local "peacekeepers" and tax collectors. This accorded with the expansionistic policy and a forced upgrade of the

Imperial German Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the Imperial Navy () was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for coast defence. Kaise ...

. Colonial acquisition became a serious factor in German domestic politics. The German colonial society was joined in 1891 by the extremely nationalistic

Pan-German League. In addition to the arguments previously made in support of colonialism, it was now argued that Germany had a duty to end the

slave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

in the colonies and free indigenous people from their Muslim enslavers. These

abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

demands, with their clear anti-Muslim bias turned the 1888 "

Arab revolt

The Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية, ) or the Great Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية الكبرى, ) was a military uprising of Arab forces against the Ottoman Empire in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. On ...

" on the East African coast into a

holy war

A religious war or a war of religion, sometimes also known as a holy war ( la, sanctum bellum), is a war which is primarily caused or justified by differences in religion. In the modern period, there are frequent debates over the extent to wh ...

. Pre-eminent, however, was the matter of German national prestige and the belief that Germany was locked in a

Social Darwinist

Social Darwinism refers to various theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economics and politics, and which were largely defined by scholars in We ...

competition with the other Great Powers, in which Germany, as a "late-comer" had to claim her due share.

Wilhelm himself lamented his nation's position as colonial followers rather than leaders. In an interview with

Cecil Rhodes in March 1899 he stated the alleged dilemma clearly: "... Germany has begun her colonial enterprise very late, and was, therefore, at the disadvantage of finding all the desirable places already occupied." Under the new

Weltpolitik

''Weltpolitik'' (, "world politics") was the imperialist foreign policy adopted by the German Empire during the reign of Emperor Wilhelm II. The aim of the policy was to transform Germany into a global power. Though considered a logical conseq ...

("Global policy"), a "place in the Sun" was sought for the "latecoming nation" (as the chancellor

Bernhard von Bülow put it in a speech to the Reichstag on 6 December 1897), which entailed the possession of colonies and a right to have a say in other colonial matters. This policy focussed on national prestige sharply contrasted with the pragmatic colonial policy advanced by Bismarck in 1884 and 1885.

Acquisitions after 1890

After 1890, Germany succeeded in acquiring only relatively minor territories. In 1895,

concessions were acquired from

Qing China in Hankau and Tientsin (modern

Wuhan

Wuhan (, ; ; ) is the capital of Hubei Province in the People's Republic of China. It is the largest city in Hubei and the most populous city in Central China, with a population of over eleven million, the ninth-most populous Chinese city an ...

and

Tianjin

Tianjin (; ; Mandarin: ), alternately romanized as Tientsin (), is a municipality and a coastal metropolis in Northern China on the shore of the Bohai Sea. It is one of the nine national central cities in Mainland China, with a total popu ...

). Following the

Juye Incident

The Juye Incident (, german: Juye Vorfall) refers to the killing of two German Catholic missionaries, Richard Henle and Franz Xaver Nies, of the Society of the Divine Word, in Juye County Shandong Province, China in the night of 1–2 Nov ...

of 1 November 1897, in which two German missionaries from the

Society of the Divine Word were murdered, Kaiser Wilhelm dispatched the

German East Asia Squadron

The German East Asia Squadron (german: Kreuzergeschwader / Ostasiengeschwader) was an Imperial German Navy cruiser squadron which operated mainly in the Pacific Ocean between the mid-1890s until 1914, when it was destroyed at the Battle of the ...

to occupy

Jiaozhou Bay

The Jiaozhou Bay (; german: Kiautschou Bucht, ) is a bay located in the prefecture-level city of Qingdao (Tsingtau), China.

The bay has historically been romanized as Kiaochow, Kiauchau or Kiao-Chau in English and Kiautschou in German.

Geogra ...

and its chief port, Tsingtao (modern

Qingdao) on the southern coast of the

Shandong peninsula

The Shandong (Shantung) Peninsula or Jiaodong (Chiaotung) Peninsula is a peninsula in Shandong Province in eastern China, between the Bohai Sea to the north and the Yellow Sea to the south. The latter name refers to the east and Jiaozhou.

Geo ...

. This became the

Kiautschou Bay Leased Territory and the area within 50 km of Jiaozhou Bay became a "Neutral Zone" in which Chinese sovereignty was limited in favour of Germany. Furthermore, Germany received mining and railway concessions in

Shandong province.

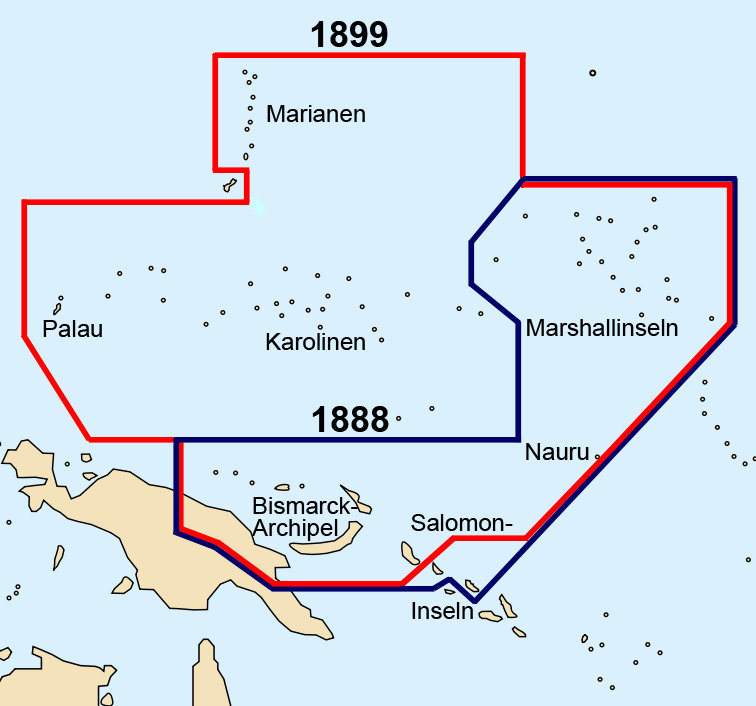

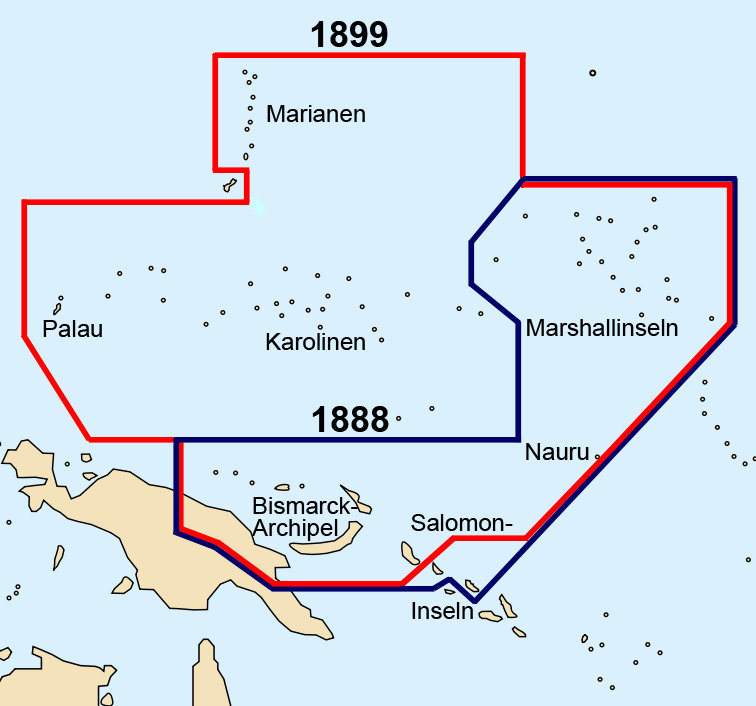

Through the

German–Spanish Treaty of 1899, Germany acquired the

Caroline Islands

The Caroline Islands (or the Carolines) are a widely scattered archipelago of tiny islands in the western Pacific Ocean, to the north of New Guinea. Politically, they are divided between the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) in the ce ...

,

Mariana Islands, and

Palau

Palau,, officially the Republic of Palau and historically ''Belau'', ''Palaos'' or ''Pelew'', is an island country and microstate in the western Pacific. The nation has approximately 340 islands and connects the western chain of the ...

in

Micronesia

Micronesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, consisting of about 2,000 small islands in the western Pacific Ocean. It has a close shared cultural history with three other island regions: the Philippines to the west, Polynesia to the east, and ...

for 17 million

gold mark

The German mark (german: Goldmark ; sign: ℳ) was the currency of the German Empire, which spanned from 1871 to 1918. The mark was paired with the minor unit of the pfennig (₰); 100 pfennigs were equivalent to 1 mark. The mark was on the g ...

s. Through the

Tripartite Convention

The Tripartite Convention of 1899 concluded the Second Samoan Civil War, resulting in the formal partition of the Samoan archipelago into a German colony and a United States territory.

Forerunners to the Tripartite Convention of 1899 were the ...

of 1899, the west part of the

Samoan islands

The Samoan Islands ( sm, Motu o Sāmoa) are an archipelago covering in the central South Pacific, forming part of Polynesia and of the wider region of Oceania. Administratively, the archipelago comprises all of the Independent State of Samoa an ...

became a German protectorate. Simultaneously, the control of existing colonies was extended inland; for example the kingdoms of

Burundi and