Gerald Smyth on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

CWGC entry

Profile

{{DEFAULTSORT:Smyth, Gerald Bryce Ferguson 1885 births 1920 deaths People from Banbridge Royal Engineers officers Royal Irish Constabulary officers British Army personnel of World War I British military personnel killed in the Irish War of Independence King's Own Scottish Borderers officers Graduates of the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich Recipients of the Croix de guerre (Belgium) Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 (France) Companions of the Distinguished Service Order Police misconduct during the Irish War of Independence People educated at Shrewsbury School Military personnel of British India

Lieutenant-Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colo ...

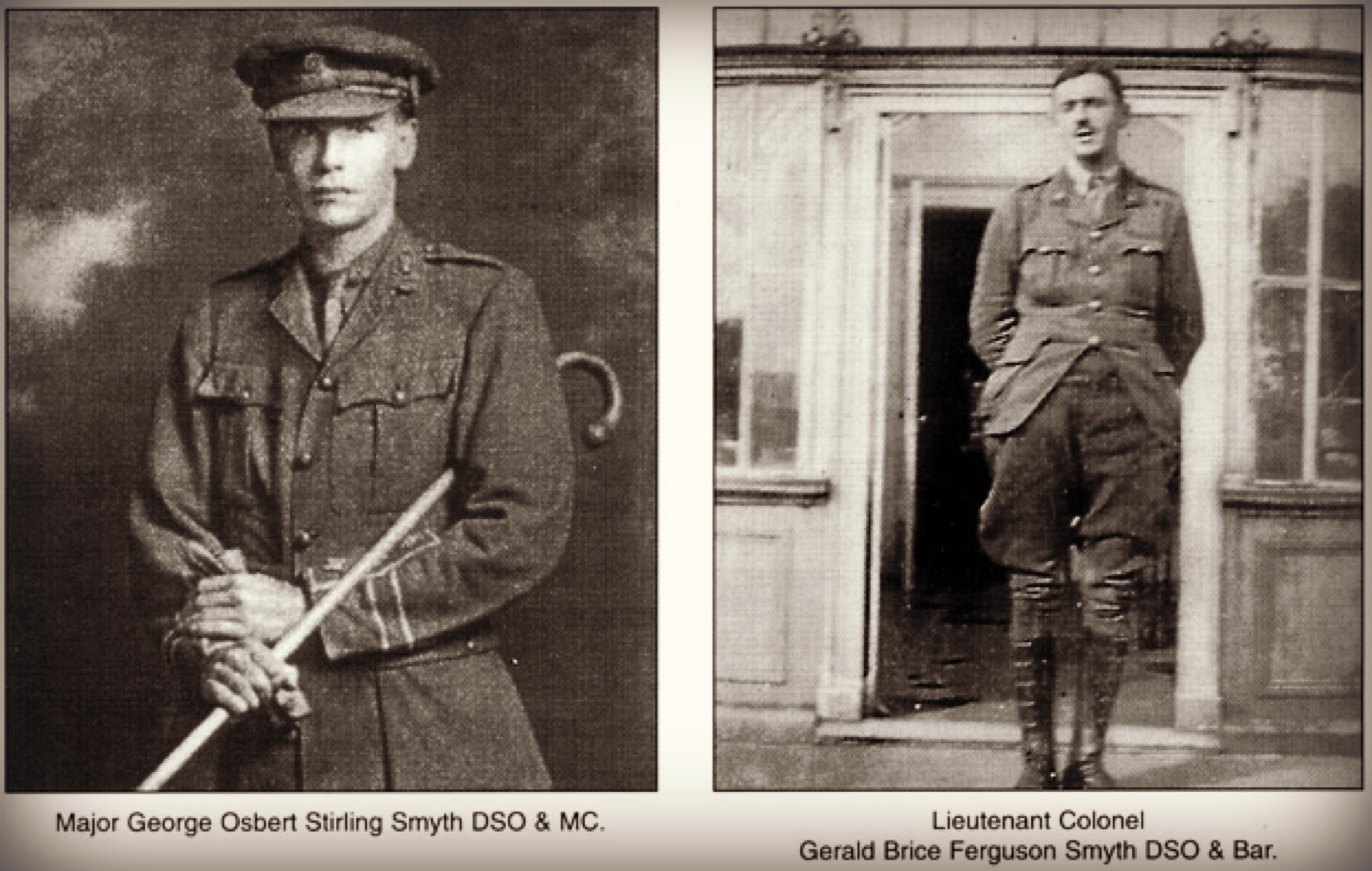

Gerald Bryce Ferguson Smyth, DSO and Bar, French Croix de Guerre

The ''Croix de Guerre'' (, ''Cross of War'') is a military decoration of France. It was first created in 1915 and consists of a square-cross medal on two crossed swords, hanging from a ribbon with various degree pins. The decoration was first aw ...

and Belgian Croix de guerre

The ''Croix de guerre'' ( French) or ''Oorlogskruis'' (Dutch), both literally translating as "Cross of War", is a military decoration of the Kingdom of Belgium established by royal decree on 25 October 1915. It was primarily awarded for bravery o ...

(7 September 1885 – 17 July 1920) was a British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

officer and police officer who was at the centre of a mutiny in the ranks of the Royal Irish Constabulary

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC, ga, Constáblacht Ríoga na hÉireann; simply called the Irish Constabulary 1836–67) was the police force in Ireland from 1822 until 1922, when all of the country was part of the United Kingdom. A separate ...

during the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

. He was shot and killed by the Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief th ...

in Cork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

in 1920.

Background

Gerald Smyth was born at Phoenix Lodge, Dalhousie,Punjab

Punjab (; Punjabi Language, Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also Romanization, romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the I ...

, India, the eldest son of George Smyth and Helen Ferguson Smyth. His father was the British High Commissioner in the Punjab and his mother was the daughter of Thomas Ferguson of Banbridge

Banbridge ( , ) is a town in County Down, Northern Ireland. It lies on the River Bann and the A1 road and is named after a bridge built over the River Bann in 1712. It is situated in the civil parish of Seapatrick and the historic barony of Iv ...

, County Down

County Down () is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, one of the nine counties of Ulster and one of the traditional thirty-two counties of Ireland. It covers an area of and has a population of 531,665. It borders County Antrim to th ...

, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

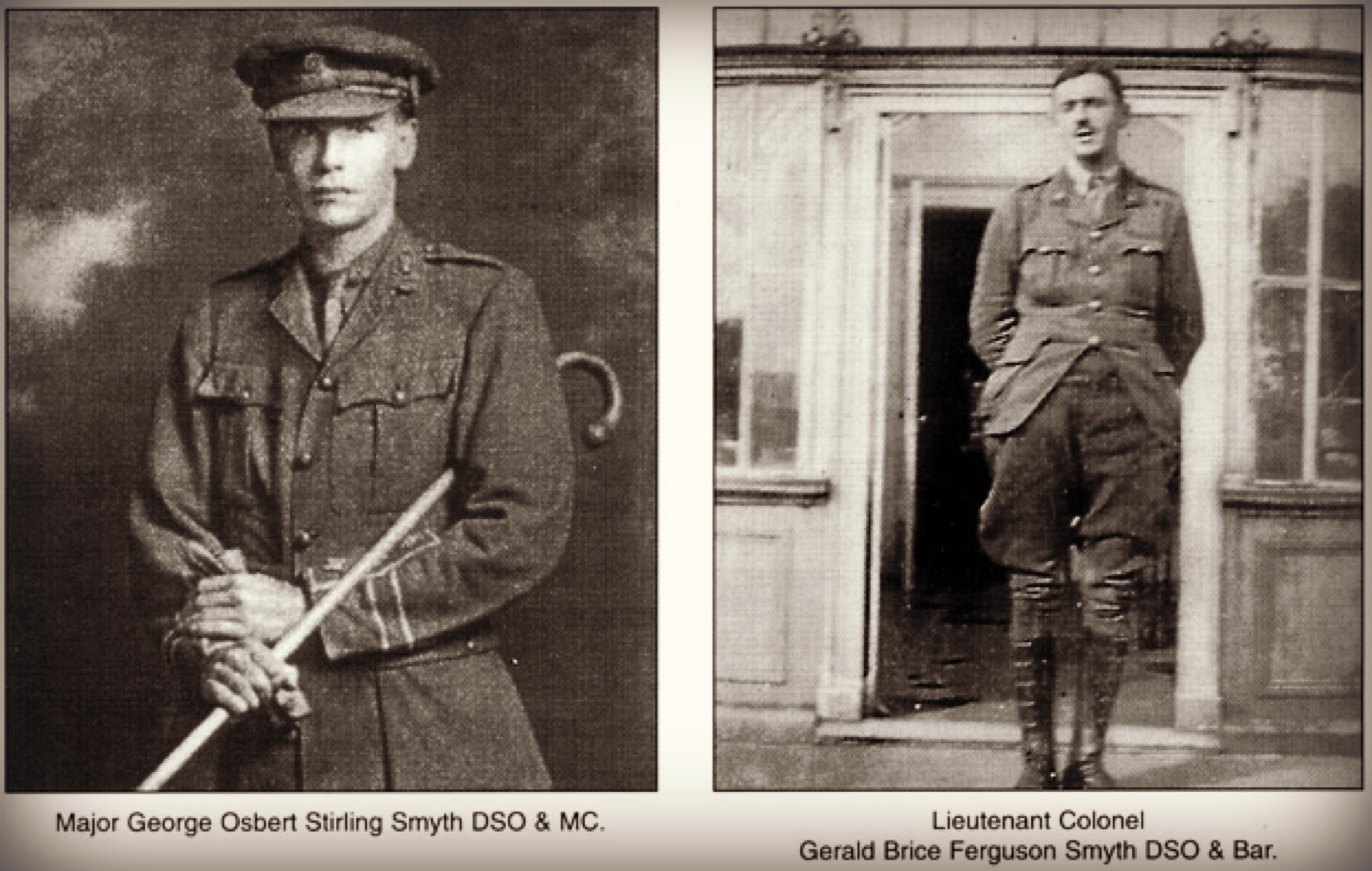

. Smyth had one brother, George Osbert Smyth, who also served as a British Army officer. Both served in the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

and in Ireland during the War of Independence.

Smyth was educated privately and as a pupil of Strangeways School and then Shrewsbury School

Shrewsbury School is a public school (English independent boarding school for pupils aged 13 –18) in Shrewsbury.

Founded in 1552 by Edward VI by Royal Charter, it was originally a boarding school for boys; girls have been admitted into ...

between 1899 and 1901.

Military service

After attending theRoyal Military Academy, Woolwich

The Royal Military Academy (RMA) at Woolwich, in south-east London, was a British Army military academy for the training of commissioned officers of the Royal Artillery and Royal Engineers. It later also trained officers of the Royal Corps of S ...

, Gerald Smyth was commissioned into the Royal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is a corps of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces and is head ...

29 July 1905 and excelled in mathematics and the Spanish language. He was posted to Gibraltar, serving with the 32nd and 45th companies and spending his free time with polo, photography and mountaineering, sustaining a serious injury to his shoulder during a trip to the Sierra Nevada

The Sierra Nevada () is a mountain range in the Western United States, between the Central Valley of California and the Great Basin. The vast majority of the range lies in the state of California, although the Carson Range spur lies primar ...

mountains. In 1913 he was posted to the Curragh

The Curragh ( ; ga, An Currach ) is a flat open plain of almost of common land in County Kildare. This area is well known for Irish horse breeding and training. The Irish National Stud is located on the edge of Kildare town, beside the ...

in Ireland where he served with the 17th Field Company.

First World War

Smyth volunteered at the outbreak of World War I even though he had been offered a position as Professor of Mathematics at theRoyal School of Military Engineering

The Royal School of Military Engineering (RSME) Group provides a wide range of training for the British Army and Defence. This includes; Combat Engineers, Carpenters, Chartered Engineers, Musicians, Band Masters, Sniffer Dogs, Veterinary Techni ...

, Chatham. He was sent to France on 17 August 1914 with the 14th Company and promoted to Captain in October. Serving throughout the war he was seriously injured on a number of occasions, losing his left arm at the elbow during the Battle of the Aisne at Givenchy whilst rescuing a wounded soldier who was caught in the open under heavy shellfire. From 1916 onwards he left the Royal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is a corps of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces and is head ...

and served with the Kings Own Scottish Borderers. He was mentioned in despatches

To be mentioned in dispatches (or despatches, MiD) describes a member of the armed forces whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which their gallant or meritorious action in the face ...

seven times and awarded the DSO twice. He served with the 6th Battalion of the KOSB at the Battle of Arras, the only unit to attain its objective on 3 May 1917. He was cited for a mention in dispatches for "consistent skill and daring," after being severely wounded, receiving shrapnel pieces in his right shoulder which at the time was believed would permanently weaken his arm. The citation in the ''London Gazette

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a major se ...

'' of 18 July 1917 read as follows:

"For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. Although seriously wounded he remained at the telephone in an ill-protected trench for many hours during a critical time, to report the course of events to Brigade Headquarters. He realised that there was no other officer of experience to replace him and his sense of duty may cost him his remaining arm, the other having been amputated as a result of a previous wound."Smyth would finish his First World War service as a brevet brigadier general commanding the 93rd Infantry Brigade of the 31st Division, despite being only 33. He would spend a year at Staff College before accepting command of the 12th Field Company in Cork on 7 June 1920, later being appointed divisional commander of the

Royal Irish Constabulary

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC, ga, Constáblacht Ríoga na hÉireann; simply called the Irish Constabulary 1836–67) was the police force in Ireland from 1822 until 1922, when all of the country was part of the United Kingdom. A separate ...

in Munster

Munster ( gle, an Mhumhain or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the south of Ireland. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" ( ga, rí ruirech). Following t ...

.

In his memoirs, Brigadier General Walker wrote of Smyth in the ''Royal Engineers Journal'': "No words can do justice to his services during the retreat of 1914. He was the life and soul of the Company, his Irish humour and pluck did wonders in maintaining the discipline of the Company".

In June 1920, Colonel Smyth was sent to Ireland at the height of the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

. He was seconded to the Royal Irish Constabulary, of which he was appointed divisional commissioner for the province of Munster

Munster ( gle, an Mhumhain or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the south of Ireland. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" ( ga, rí ruirech). Following t ...

.

Listowel

On 19 June 1920 Smyth allegedly made a speech to the ranks of theListowel

Listowel ( ; , IPA: �lʲɪsˠˈt̪ˠuəhəlʲ is a heritage market town in County Kerry, Ireland. It is on the River Feale, from the county town, Tralee. The town of Listowel had a population of 4,820 according to the CSO Census 2016.

Desc ...

RIC in which he was reported to have said:

"Police and military will patrol the country roads at least five nights a week. They are not to confine themselves to the main roads but make across the country, lie in ambush, take cover behind fences near roads, and when civilians are seen approaching shout: 'Hands up!' Should the order be not obeyed, shoot, and shoot with effect. If the persons approaching carry their hands in their pockets or are in any way suspicious looking, shoot them down. You may make mistakes occasionally and innocent persons may be shot, but that cannot be helped and you are bound to get the right persons sometimes. The more you shoot the better I will like you; and I assure you that no policeman will get into trouble for shooting any man and I will guarantee that your names will not be given at the inquest."There has been debate over the accuracy of this reported speech. The ''

Freeman's Journal

The ''Freeman's Journal'', which was published continuously in Dublin from 1763 to 1924, was in the nineteenth century Ireland's leading nationalist newspaper.

Patriot journal

It was founded in 1763 by Charles Lucas and was identified with rad ...

'' later reported that it was polemically based to discredit British governance.

One officer, Constable Jeremiah Mee, responded to Smyth's speech by placing his gun on the table and calling Smyth a murderer. Smyth ordered Mee's arrest, but the RIC men present refused. Mee and thirteen other RIC officers resigned, with most going on to join or assist the Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief th ...

. Mee became a confidant and ally of Michael Collins Michael Collins or Mike Collins most commonly refers to:

* Michael Collins (Irish leader) (1890–1922), Irish revolutionary leader, soldier, and politician

* Michael Collins (astronaut) (1930–2021), American astronaut, member of Apollo 11 and ...

.

However, Mee's claims were denied by Smyth plus Major General Henry Hugh Tudor and Inspector John M. Regan, who were both present at the occasion. Smyth was summoned to London to brief Prime Minister David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for lea ...

and his own written account of his remarks was read to Parliament and debated:

"I wish to make the present situation clear to all ranks. A policeman is perfectly justified in shooting any person seen with arms (guns) who does not immediately throw up his hands when ordered. A policeman is perfectly justified in shooting any man who he has good reason to believe is carrying arms (guns) and who does not immediately throw up his arms when ordered. Every proper precaution will be taken at police inquests that no information will be given to Sinn Fein as to the identity of any individual or the movements of the police. I wish to make it perfectly clear to all ranks that I will not tolerate reprisals. They bring discredit on the police and I will deal most severely with any officer or man concerned in them."

Death

Colonel Smyth's speech marked him for attention from the IRA. He subsequently returned to Cork and took lodgings at the Cork & County Club, anAnglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the establis ...

social club

A social club may be a group of people or the place where they meet, generally formed around a common interest, occupation, or activity. Examples include: book discussion clubs, chess clubs, anime clubs, country clubs, charity work, criminal ...

. On the evening of 17 July 1920 he was in the smoking room

A smoking room (or smoking lounge) is a room which is specifically provided and furnished for smoking, generally in buildings where smoking is otherwise prohibited.

Locations and facilities

Smoking rooms can be found in public buildings suc ...

when a six-man IRA team led by Dan "Sandow" O'Donovan entered and allegedly said to him, "Colonel, were not your orders to shoot on sight? Well you are in sight now, so prepare." Colonel Smyth jumped to his feet before being riddled with bullets. Despite being shot twice in the head, once through the heart and twice through the chest, the Colonel staggered to the passage where he dropped dead. He was 34 years old.

Colonel Gerald Smyth was buried at Banbridge

Banbridge ( , ) is a town in County Down, Northern Ireland. It lies on the River Bann and the A1 road and is named after a bridge built over the River Bann in 1712. It is situated in the civil parish of Seapatrick and the historic barony of Iv ...

, County Down

County Down () is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, one of the nine counties of Ulster and one of the traditional thirty-two counties of Ireland. It covers an area of and has a population of 531,665. It borders County Antrim to th ...

on 21 July 1920. His funeral was followed by a three-day sectarian riot during which a Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

man William Steritt was shot and killed, two days after attending his funeral. Three Irish nationalists

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cu ...

were later convicted of firearms offences. The date of Smyth's burial coincided with the mass expulsion or "clearing" of Catholics, Socialists and Protestants (that were considered disloyal) from Belfast's shipyards, foundries, linen mills and other commercial concerns that was part of the Troubles of the early 1920s.

Smyth's brother, George Osbert Smyth, allegedly became a member of the Dublin District Special Branch, nicknamed the Cairo Gang

The Cairo Gang was a group of British intelligence agents who were sent to Dublin during the Irish War of Independence to conduct intelligence operations against prominent members of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) with, according to Irish intel ...

, a group of British intelligence officers in Dublin sent specially to spy on leading IRA figures. Osbert Smyth was fatally shot in October 1920 while trying to arrest IRA members Dan Breen

Daniel Breen (11 August 1894 – 27 December 1969) was a volunteer in the Irish Republican Army during the Irish War of Independence and the Irish Civil War. In later years he was a Fianna Fáil politician.

Background

Breen was born in Gr ...

and Seán Treacy

Seán Allis Treacy ( ga, Seán Ó Treasaigh; 14 February 1895 – 14 October 1920) was one of the leaders of the Third Tipperary Brigade of the IRA during the Irish War of Independence. He was one of a small group whose actions initiated tha ...

at a house in Drumcondra. Several other Cairo Gang members were shot dead early in the morning of Bloody Sunday

Bloody Sunday may refer to:

Historical events Canada

* Bloody Sunday (1923), a day of police violence during a steelworkers' strike for union recognition in Sydney, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia

* Bloody Sunday (1938), police violence aga ...

, 21 November 1920, on the orders of Michael Collins Michael Collins or Mike Collins most commonly refers to:

* Michael Collins (Irish leader) (1890–1922), Irish revolutionary leader, soldier, and politician

* Michael Collins (astronaut) (1930–2021), American astronaut, member of Apollo 11 and ...

.

Smyth was honoured by the Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants, particularly those of Ulster Scots people, Ulster Sco ...

who renamed Loyal Orange Lodge 518 as the 'Colonel Smyth Memorial Lodge' (Steritt was similarly commemorated by Orange Lodge 257). According to historians Tom Mahon and James Gillogly, "Smyth was the most senior police officer killed in the conflict." Tom Mahon and James J. Gillogly (2008), ''Decoding the IRA'', Mercier Press, Cork City

Cork ( , from , meaning 'marsh') is the second largest city in Ireland and third largest city by population on the island of Ireland. It is located in the south-west of Ireland, in the province of Munster. Following an extension to the city's ...

. Page 273.

References

External links

CWGC entry

Profile

{{DEFAULTSORT:Smyth, Gerald Bryce Ferguson 1885 births 1920 deaths People from Banbridge Royal Engineers officers Royal Irish Constabulary officers British Army personnel of World War I British military personnel killed in the Irish War of Independence King's Own Scottish Borderers officers Graduates of the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich Recipients of the Croix de guerre (Belgium) Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 (France) Companions of the Distinguished Service Order Police misconduct during the Irish War of Independence People educated at Shrewsbury School Military personnel of British India