George Washington in the American Revolution on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Washington played a key role in the outbreak of the

Washington played a key role in the outbreak of the

In December 1758 Washington resigned his military commission, and spent the next 16 years as a wealthy Virginia plantation owner; as such he also served in the

In December 1758 Washington resigned his military commission, and spent the next 16 years as a wealthy Virginia plantation owner; as such he also served in the

Washington assumed command of the colonial forces outside Boston on July 3, 1775, during the ongoing

Washington assumed command of the colonial forces outside Boston on July 3, 1775, during the ongoing

In August, the British finally launched their campaign to capture New York City. They first landed on Long Island in force, and flanked Washington's forward positions in the

In August, the British finally launched their campaign to capture New York City. They first landed on Long Island in force, and flanked Washington's forward positions in the

This action significantly boosted the army's morale, but it also brought Cornwallis out of New York. He reassembled an army of more than 6,000 men, and marched most of them against a position Washington had taken south of Trenton. Leaving a garrison of 1,200 at

This action significantly boosted the army's morale, but it also brought Cornwallis out of New York. He reassembled an army of more than 6,000 men, and marched most of them against a position Washington had taken south of Trenton. Leaving a garrison of 1,200 at

Washington's difficulty in discerning Howe's motives was due to the presence of a British army moving south from Quebec toward Fort Ticonderoga under the command of General

Washington's difficulty in discerning Howe's motives was due to the presence of a British army moving south from Quebec toward Fort Ticonderoga under the command of General

Meanwhile, Burgoyne, out of reach from help from Howe, was trapped and forced to surrender his entire army on October 17, ten days after the

Meanwhile, Burgoyne, out of reach from help from Howe, was trapped and forced to surrender his entire army on October 17, ten days after the

Washington's opponent in New York, however, was not inactive. Clinton engaged in a number of amphibious raids against coastal communities from

Washington's opponent in New York, however, was not inactive. Clinton engaged in a number of amphibious raids against coastal communities from

The British in late 1779 embarked on a new strategy based on the assumption that most Southerners were Loyalists at heart. General Clinton withdrew the British garrison from Newport, and marshalled a force of more than 10,000 men that in the first half of 1780 successfully besieged Charleston, South Carolina. In June 1780 he captured over 5,000 Continental soldiers and militia in the single worst defeat of the war for the Americans. Washington had at the end of March pessimistically dispatched several regiments troops southward from his army, hoping they might have some effect in what he saw as a looming disaster. He also ordered troops stationed in Virginia and North Carolina south, but these were either captured at Charleston, or scattered later at

The British in late 1779 embarked on a new strategy based on the assumption that most Southerners were Loyalists at heart. General Clinton withdrew the British garrison from Newport, and marshalled a force of more than 10,000 men that in the first half of 1780 successfully besieged Charleston, South Carolina. In June 1780 he captured over 5,000 Continental soldiers and militia in the single worst defeat of the war for the Americans. Washington had at the end of March pessimistically dispatched several regiments troops southward from his army, hoping they might have some effect in what he saw as a looming disaster. He also ordered troops stationed in Virginia and North Carolina south, but these were either captured at Charleston, or scattered later at

The early months of 1781 continued to be difficult for the American cause. Troops mutinied in Pennsylvania, inspiring troops in New Jersey to also do so. Washington was uninvolved in resolving the Pennsylvania troops' demands, but he sent troops under General

The early months of 1781 continued to be difficult for the American cause. Troops mutinied in Pennsylvania, inspiring troops in New Jersey to also do so. Washington was uninvolved in resolving the Pennsylvania troops' demands, but he sent troops under General  General Clinton had turned over command of the southern army to General Cornwallis. After the defeat of Gates at Camden, he had nominally gained control over South Carolina, although there was significant militia skirmishing, led by partisan fighters like

General Clinton had turned over command of the southern army to General Cornwallis. After the defeat of Gates at Camden, he had nominally gained control over South Carolina, although there was significant militia skirmishing, led by partisan fighters like

Upon his arrival at Yorktown Washington had command of 5,700 Continentals, 3,200 militia and 7,800 French regulars. On September 28 the Franco-American army blockaded Yorktown, and began digging siege trenches on October 6. By the 9th guns had been emplaced on the first parallel, and began firing on the entrenched British camp. Work proceeded rapidly thereafter on the second parallel, only from the British defenses. On the 14th two outer redoubts of the British defenses were stormed, and the entirety of the British camp was with range of the French and American cannons. After a failed attempt to escape across the York River, Cornwallis opened negotiations on October 17. Two days later terms were agreed, and his 8,000 men paraded in surrender. Despite the size of the contending forces, and the importance of the siege, there were only 260 allied and 550 British casualties. One of the American casualties was Washington's stepson and aide-de-camp

Upon his arrival at Yorktown Washington had command of 5,700 Continentals, 3,200 militia and 7,800 French regulars. On September 28 the Franco-American army blockaded Yorktown, and began digging siege trenches on October 6. By the 9th guns had been emplaced on the first parallel, and began firing on the entrenched British camp. Work proceeded rapidly thereafter on the second parallel, only from the British defenses. On the 14th two outer redoubts of the British defenses were stormed, and the entirety of the British camp was with range of the French and American cannons. After a failed attempt to escape across the York River, Cornwallis opened negotiations on October 17. Two days later terms were agreed, and his 8,000 men paraded in surrender. Despite the size of the contending forces, and the importance of the siege, there were only 260 allied and 550 British casualties. One of the American casualties was Washington's stepson and aide-de-camp

In 1783 Washington continued to keep the army ready at Newburgh, although some of his officers made veiled threats to Congress about long-overdue pay. Washington diffused this hint at mutiny with an address to the troops on March 15 recommending patience. On March 26 he was informed that France and Spain had made peace with Britain, one of the last preconditions for a final peace. Thereafter he was occupied with the logistics of prisoner exchanges, and pressed Congress to ensure soldiers being furloughed or discharged received at least some of their back pay. He met once with General Carleton to discuss the return of runaway slaves, a contentious point on which Carleton refused to budge. (Carleton announced in the meeting, to Washington's apparent chagrin, that 6,000 Negroes had already been sent to Nova Scotia, and refused to assist the efforts of slave hunters.) In June troops in Pennsylvania mutinied, marching on Philadelphia and surrounding the State House where Congress sat. In response Congress temporarily relocated to Princeton, and Washington dispatched troops south from New York. After action by Congress addressed their concerns, the mutinous troops returned to their posts.

The Treaty of Paris was signed on September 3, 1783. On November 25, the British evacuated New York City, and Washington and Governor George Clinton took possession of the city, ending large-scale British occupation of American territory. (Britain continued to occupy frontier forts that had been ceded to the United States until the mid-1790s.)

In 1783 Washington continued to keep the army ready at Newburgh, although some of his officers made veiled threats to Congress about long-overdue pay. Washington diffused this hint at mutiny with an address to the troops on March 15 recommending patience. On March 26 he was informed that France and Spain had made peace with Britain, one of the last preconditions for a final peace. Thereafter he was occupied with the logistics of prisoner exchanges, and pressed Congress to ensure soldiers being furloughed or discharged received at least some of their back pay. He met once with General Carleton to discuss the return of runaway slaves, a contentious point on which Carleton refused to budge. (Carleton announced in the meeting, to Washington's apparent chagrin, that 6,000 Negroes had already been sent to Nova Scotia, and refused to assist the efforts of slave hunters.) In June troops in Pennsylvania mutinied, marching on Philadelphia and surrounding the State House where Congress sat. In response Congress temporarily relocated to Princeton, and Washington dispatched troops south from New York. After action by Congress addressed their concerns, the mutinous troops returned to their posts.

The Treaty of Paris was signed on September 3, 1783. On November 25, the British evacuated New York City, and Washington and Governor George Clinton took possession of the city, ending large-scale British occupation of American territory. (Britain continued to occupy frontier forts that had been ceded to the United States until the mid-1790s.)

Washington's contribution to victory in the war was not that of a great battlefield tactician. He has been characterized, according to historian

Washington's contribution to victory in the war was not that of a great battlefield tactician. He has been characterized, according to historian

online

* Flynn, Matthew J., and Stephen E. Grffin. ''Washington and Napoleon: Leadership in the Age of Revolution'' (Potomac Books, 2012). * Freeman, Douglas Southall. ''Washington'' (1995) 896pp; Abridged version of his Pulitzer prize-winning seven volume Biography; vol 4-5-6 cover the war years

excerpt

* Higginbotham, Don. ''George Washington and the American Military Tradition'' (U of Georgia Press, 1987). * Higginbotham, Don. "American Historians and the Military History of the American Revolution." ''American Historical Review'' 70.1 (1964): 18–34. * Higginbotham, Don. "Essay Review: The Washington Theme in Recent Historical Literature." (1990): 423–437

online

* Kwasny, Mark V. ''Washington's Partisan War, 1775-1783'' (1996

online

* Laver, Harry S. and Jeffrey J. Matthews, eds. ''The Art of Command: Military Leadership from George Washington to Colin Powell'' (2008) pp 11–32

online

* McCullough, David. ''1776'' (2005) * Neimeyer, Charles Patrick. ''America Goes to War: A Social History of the Continental Army'' (1995

complete text online

* Orr III, Lt-Colonel Alan L. "George Washington: America's First Strategic Leader" (U.S. Army War College, 2007

online

* Palmer, Dave Richard. ''The Way of the Fox: American Strategy in the War for America, 1775-1783'' (1975) * Risch, Erna. ''Supplying Washington's Army'' (Center of Military History, 1981). * Royster, Charles. ''A Revolutionary People at War: The Continental Army and American Character, 1775-1783'' (1979) * Stillings, Kris J. "Washington and the Formulation of American Strategy for the War of Independence" (U.S. Marine Corps Staff and Command College, 2001

online

* Whiteley, Emily Stone. ''Washington and his Aides-de-Camp'' (1936) * Wright, Esmond. ''Washington and the American Revolution'' (1962), brief and scholarly.

online

* Kilmeade, Brian, and Don Yaeger. ''George Washington's Secret Six: The Spy Ring that Saved the American Revolution'' (Penguin, 2016). * Mahoney, Harry Thayer, and Marjorie Locke Mahoney. ''Gallantry in action: A biographic dictionary of espionage in the American revolutionary war'' (University Press of America, 1999). * Misencik, Paul R. ''Sally Townsend, George Washington's Teenage Spy'' (McFarland, 2015). * O'Toole, George J.A. ''Honorable Treachery: A History of US Intelligence, Espionage, and Covert Action from the American Revolution to the CIA'' (2nd ed. 2014), ch 1–5. * Rose, Alexander. ''Washington's Spies: The Story of America's First Spy Ring'' (2006), focuses on the Culper Ring. * Van Doren, Carl. ''Secret History of the American Revolution: An Account of the Conspiracies of Benedict Arnold and Numerous Others Drawn from the Secret Service'' (1941

online free

{{DEFAULTSORT:Revolution, George Washington In The American Revolutionary War

George Washington

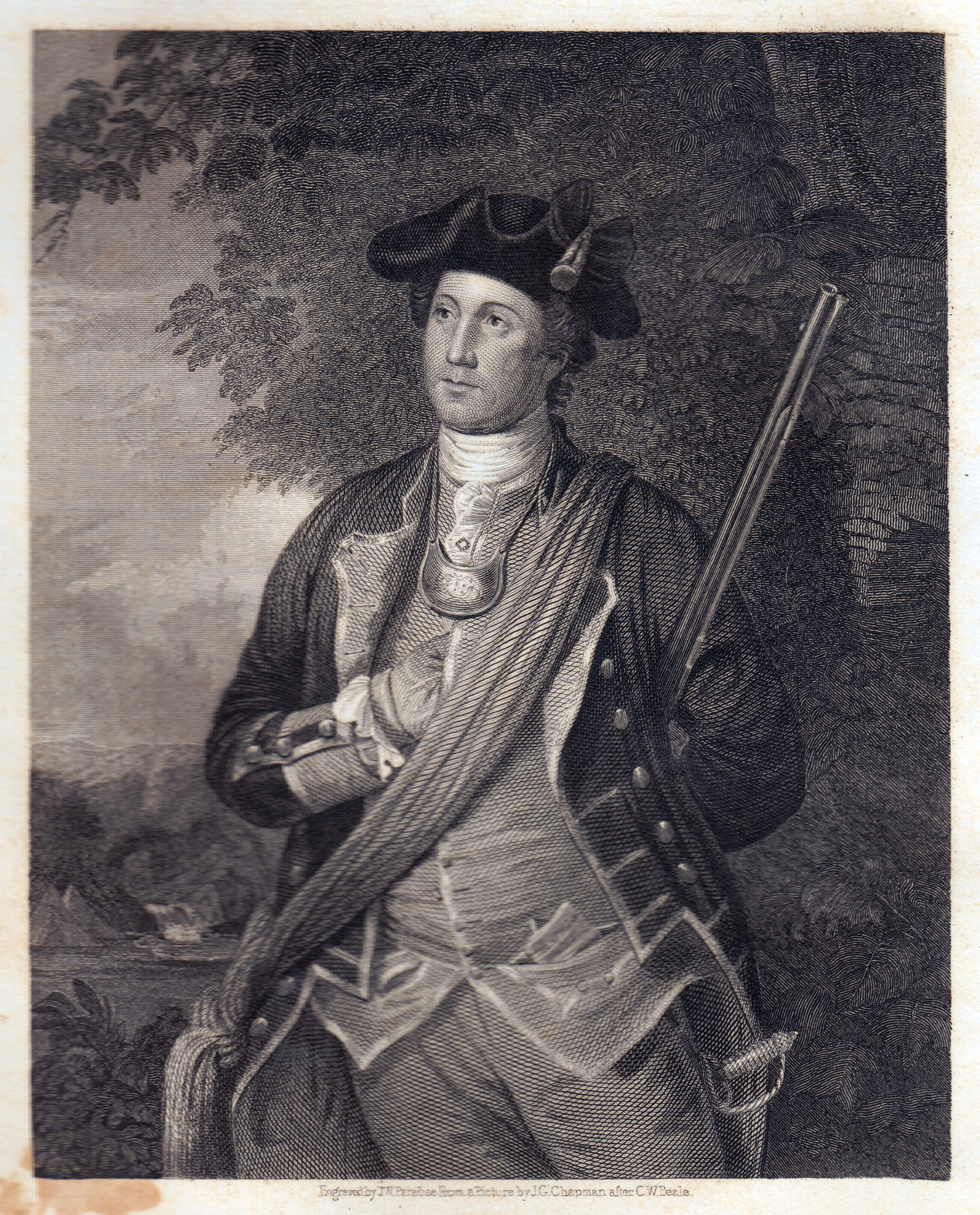

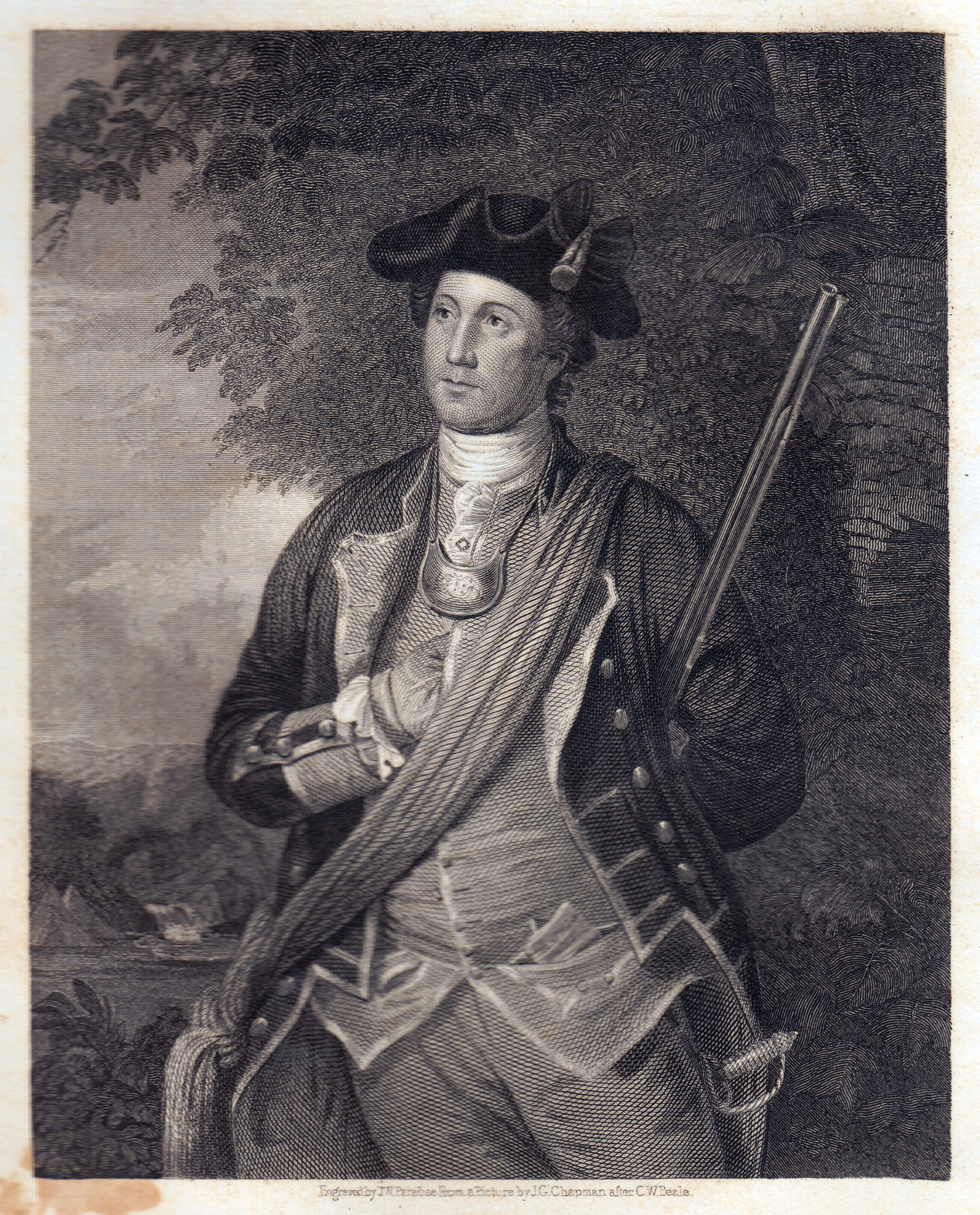

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

(February 22, 1732 – December 14, 1799) commanded the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

(1775–1783). After serving as President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

(1789 to 1797), he briefly was in charge of a new army in 1798.

Washington, despite his youth, played a major role in the frontier wars against the French and Indians in the 1750s and 1760s. He played the leading military role in the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

. When the war broke out with the Battles of Lexington and Concord

The Battles of Lexington and Concord were the first military engagements of the American Revolutionary War. The battles were fought on April 19, 1775, in Middlesex County, Province of Massachusetts Bay, within the towns of Lexington, Concord, ...

in April 1775, Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

appointed him the first commander-in-chief of the new Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

on June 14. The task he took on was enormous, balancing regional demands, competition among his subordinates, morale among the rank and file, attempts by Congress to manage the army's affairs too closely, requests by state governors for support, and an endless need for resources with which to feed, clothe, equip, arm, and move the troops. He was not usually in command of the many state militia units.

In the early years of the war Washington was often in the middle of the action, first directing the Siege of Boston

The siege of Boston (April 19, 1775 – March 17, 1776) was the opening phase of the American Revolutionary War. New England militiamen prevented the movement by land of the British Army, which was garrisoned in what was then the peninsular town ...

to its successful conclusion, but then losing New York City and almost losing New Jersey before winning surprising and decisive victories at Trenton and Princeton

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the nin ...

at the end of the 1776 campaign season. At the end of the year in both 1775 and 1776, he had to deal with expiring enlistments, since the Congress had only authorized the army's existence for single years. With the 1777 establishment of a more permanent army structure and the introduction of three-year enlistments, Washington built a reliable cohort of experienced troops, although hard currency and supplies of all types were difficult to come by. In 1777 Washington was again defeated in the defense of Philadelphia, but sent critical support to Horatio Gates

Horatio Lloyd Gates (July 26, 1727April 10, 1806) was a British-born American army officer who served as a general in the Continental Army during the early years of the Revolutionary War. He took credit for the American victory in the Battl ...

that made the defeat of Burgoyne at Saratoga possible. Following a difficult winter at Valley Forge

Valley Forge functioned as the third of eight winter encampments for the Continental Army's main body, commanded by General George Washington, during the American Revolutionary War. In September 1777, Congress fled Philadelphia to escape the ...

and the entry of France into the war in 1778, Washington followed the British army as it withdrew from Philadelphia back to New York, and fought an ultimately inconclusive battle at Monmouth Court House in New Jersey.

Washington's activities from late 1778 to 1780 were more diplomatic and organizational, as his army remained outside New York, watching Sir Henry Clinton's army that occupied the city. Washington strategized with the French on how best to cooperate in actions against the British, leading to ultimately unsuccessful attempts to dislodge the British from Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is an American seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, and northeast of New Yor ...

and Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Br ...

. His attention was also drawn to the frontier war, which prompted the 1779 Continental Army expedition of John Sullivan into upstate New York. When General Clinton sent the turncoat General Benedict Arnold to raid in Virginia, Washington began to detach elements of his army to face the growing threat there. The arrival of Lord Cornwallis

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, (31 December 1738 – 5 October 1805), styled Viscount Brome between 1753 and 1762 and known as the Earl Cornwallis between 1762 and 1792, was a British Army general and official. In the United S ...

in Virginia after campaigning in the south presented Washington with an opportunity to strike a decisive blow. Washington's army and the French army moved south to face Cornwallis, and a cooperative French navy under Admiral de Grasse

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

successfully disrupted British attempts to control of the Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the Eastern Shore of Maryland / ...

, completing the entrapment of Cornwallis, who surrendered after the Siege of Yorktown

The Siege of Yorktown, also known as the Battle of Yorktown, the surrender at Yorktown, or the German battle (from the presence of Germans in all three armies), beginning on September 28, 1781, and ending on October 19, 1781, at Yorktown, Virg ...

in October 1781. Although Yorktown marked the end of significant hostilities in North America, the British still occupied New York and other cities, so Washington had to maintain the army in the face of a bankrupt Congress and troops that were at times mutinous over conditions and pay. The army was formally disbanded after peace in 1783, and Washington resigned his commission as commander-in-chief on December 23, 1783.

Military experience

Born into a well-to-do Virginia family near Fredericksburg in , Washington was schooled locally until the age of 15. The early death of his father when he was 11 eliminated the possibility of schooling in England, and his mother rejected attempts to place him in theRoyal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

. Thanks to the connection by marriage of his half-brother Lawrence to the wealthy Fairfax family, Washington was appointed surveyor of Culpeper County

Culpeper County is a county located along the borderlands of the northern and central region of the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 United States Census, the population was 52,552. Its county seat and only incorporated community is C ...

in 1749; he was just 17 years old. Washington's brother had purchased an interest in the Ohio Company

The Ohio Company, formally known as the Ohio Company of Virginia, was a land speculation company organized for the settlement by Virginians of the Ohio Country (approximately the present U.S. state of Ohio) and to trade with the Native Americ ...

, a land acquisition and settlement company whose objective was the settlement of Virginia's frontier areas, including the Ohio Country, territory north and west of the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of ...

. Its investors also included Virginia's Royal Governor, Robert Dinwiddie

Robert Dinwiddie (1692 – 27 July 1770) was a British colonial administrator who served as lieutenant governor of colonial Virginia from 1751 to 1758, first under Governor Willem Anne van Keppel, 2nd Earl of Albemarle, and then, from July 1756 ...

, who appointed Washington a major in the provincial militia in February 1753.

Washington played a key role in the outbreak of the

Washington played a key role in the outbreak of the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the st ...

, and then led the defense of Virginia between 1755 and 1758 as colonel of the Virginia Regiment. Although Washington never received a commission in the British Army, he gained valuable military, political, and leadership skills, and received significant public exposure in the colonies and abroad.O'Meara, p. 45 He closely observed British military tactics, gaining a keen insight into their strengths and weaknesses that proved invaluable during the Revolution. He demonstrated his toughness and courage in the most difficult situations, including disasters and retreats. He developed a command presence—given his size, strength, stamina, and bravery in battle, he appeared to soldiers to be a natural leader and they followed him without question. Washington learned to organize, train, and drill, and discipline his companies and regiments. From his observations, readings and conversations with professional officers, he learned the basics of battlefield tactics, as well as a good understanding of problems of organization and logistics.

He gained an understanding of overall strategy, especially in locating strategic geographical points. He developed a very negative idea of the value of militia, who seemed too unreliable, too undisciplined, and too short-term compared to regulars. On the other hand, his experience was limited to command of at most 1,000 men, and came only in remote frontier conditions that were far removed from the urban situations he faced during the Revolution at Boston, New York, Trenton and Philadelphia.

Political resistance

In December 1758 Washington resigned his military commission, and spent the next 16 years as a wealthy Virginia plantation owner; as such he also served in the

In December 1758 Washington resigned his military commission, and spent the next 16 years as a wealthy Virginia plantation owner; as such he also served in the Virginia House of Burgesses

The House of Burgesses was the elected representative element of the Virginia General Assembly, the legislative body of the Colony of Virginia. With the creation of the House of Burgesses in 1642, the General Assembly, which had been established ...

. Although he expressed opposition to the 1765 Stamp Act

The Stamp Act 1765, also known as the Duties in American Colonies Act 1765 (5 Geo. III c. 12), was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain which imposed a direct tax on the British colonies in America and required that many printed materials i ...

, the first direct tax on the colonies, he did not take a leading role in the growing colonial resistance until protests of the Townshend Acts (enacted in 1767) became widespread. In May 1769, Washington introduced a proposal, drafted by his friend George Mason

George Mason (October 7, 1792) was an American planter, politician, Founding Father, and delegate to the U.S. Constitutional Convention of 1787, one of the three delegates present who refused to sign the Constitution. His writings, including ...

, calling for Virginia to boycott British goods until the Acts were repealed. Parliament repealed the Townshend Acts in 1770, and, for Washington at least, the crisis had passed. However, Washington regarded the passage of the Intolerable Acts

The Intolerable Acts were a series of punitive laws passed by the British Parliament in 1774 after the Boston Tea Party. The laws aimed to punish Massachusetts colonists for their defiance in the Tea Party protest of the Tea Act, a tax measur ...

in 1774 as "an Invasion of our Rights and Privileges". In July 1774, he chaired the meeting at which the "Fairfax Resolves

The Fairfax Resolves were a set of resolutions adopted by a committee in Fairfax County in the colony of Virginia on July 18, 1774, in the early stages of the American Revolution. Written at the behest of George Washington and others, they were a ...

" were adopted, which called for, among other things, the convening of a Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for thirteen of Britain's colonies in North America, and the newly declared United States just before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. ...

. In August, Washington attended the First Virginia Convention

The Virginia Conventions have been the assemblies of delegates elected for the purpose of establishing constitutions of fundamental law for the Commonwealth of Virginia superior to General Assembly legislation. Their constitutions and subsequ ...

, where he was selected as a delegate to the First Continental Congress

The First Continental Congress was a meeting of delegates from 12 of the 13 British colonies that became the United States. It met from September 5 to October 26, 1774, at Carpenters' Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, after the British Nav ...

. As tensions rose in 1774, he assisted in the training of county militias in Virginia and organized enforcement of the boycott of British goods instituted by the Congress.

Major roles

General Washington, the Commander in Chief, assumed five main roles during the war. *First, he designed the overall strategy of the war, in cooperation with Congress. The goal was always independence. When France entered the war, he worked closely with the soldiers it sent—they were decisive in the great victory at Yorktown in 1781. *Second, he provided leadership of troops against the main British forces in 1775–1777 and again in 1781. He lost many of his battles, but he never surrendered his army during the war, and he continued to fight the British relentlessly until the war's end. Washington worked hard to develop a successful espionage system to detect British locations and plans. In 1778, he formed theCulper Ring

The Culper Ring was a network of spies active during the American Revolutionary War, organized by Major Benjamin Tallmadge and General George Washington in 1778 during the British occupation of New York City. The name "Culper" was suggested by ...

to spy on enemy movements in New York City. In 1780 it discovered Benedict Arnold

Benedict Arnold ( Brandt (1994), p. 4June 14, 1801) was an American military officer who served during the Revolutionary War. He fought with distinction for the American Continental Army and rose to the rank of major general before defect ...

was a traitor. The British intelligence system was completely fooled in 1781, unaware that Washington and the French armies were moving from the Northeast to Yorktown, Virginia.

*Third, he was charged selecting and guiding the generals. In June 1776, Congress made its first attempt at running the war effort with the committee known as "Board of War and Ordnance", succeeded by the Board of War in July 1777, a committee which eventually included members of the military. The command structure of the armed forces was a hodgepodge of Congressional appointees (and Congress sometimes made those appointments without Washington's input) with state-appointments filling the lower ranks. The results of his general staff were mixed, as some of his favorites never mastered the art of command, such as John Sullivan. Eventually, he found capable officers such as Nathanael Greene

Nathanael Greene (June 19, 1786, sometimes misspelled Nathaniel) was a major general of the Continental Army in the American Revolutionary War. He emerged from the war with a reputation as General George Washington's most talented and dependab ...

, Daniel Morgan

Daniel Morgan (1735–1736July 6, 1802) was an American pioneer, soldier, and politician from Virginia. One of the most respected battlefield tacticians of the American Revolutionary War of 1775–1783, he later commanded troops during the sup ...

, Henry Knox

Henry Knox (July 25, 1750 – October 25, 1806), a Founding Father of the United States, was a senior general of the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, serving as chief of artillery in most of Washington's campaigns. Following th ...

(chief of artillery), and Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charle ...

(chief of staff). The American officers never equaled their opponents in tactics and maneuver, and they lost most of the pitched battles. The great successes at Boston (1776), Saratoga (1777), and Yorktown (1781) came from trapping the British far from base with much larger numbers of troops.

*Fourth, he took charge of training the army and providing supplies, from food to gunpowder to tents. He recruited regulars and assigned Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben

Friedrich Wilhelm August Heinrich Ferdinand von Steuben (born Friedrich Wilhelm Ludolf Gerhard Augustin Louis von Steuben; September 17, 1730 – November 28, 1794), also referred to as Baron von Steuben (), was a Prussian military officer who ...

, a veteran of the Prussian general staff, to train them, who transformed Washington's army into a disciplined and effective force. The war effort and getting supplies to the troops were under the purview of Congress, but Washington pressured the Congress to provide the essentials. There was never nearly enough.

*Washington's fifth and most important role in the war effort was the embodiment of armed resistance to the Crown, serving as the representative man of the Revolution. His long-term strategy was to maintain an army in the field at all times, and eventually this strategy worked. His enormous personal and political stature and his political skills kept Congress, the army, the French, the militias, and the states all pointed toward a common goal. Furthermore, he permanently established the principle of civilian supremacy in military affairs by voluntarily resigning his commission and disbanding his army when the war was won, rather than declaring himself monarch. He also helped to overcome the distrust of a standing army by his constant reiteration that well-disciplined professional soldiers counted for twice as much as poorly trained and led militias.

Intelligence

George Washington was a skilled manager of intelligence. He utilized agents behind enemy lines, recruited both Tory and Patriot sources, interrogated travelers for intelligence information, and launched scores of agents on both intelligence and counterintelligence missions. He was adept at deception operations and tradecraft and was a skilled propagandist. He also practiced sound operational security. His main failure was missing all the signals in 1780 thatBenedict Arnold

Benedict Arnold ( Brandt (1994), p. 4June 14, 1801) was an American military officer who served during the Revolutionary War. He fought with distinction for the American Continental Army and rose to the rank of major general before defect ...

was increasingly disaffected and had Loyalist connections.

As an intelligence manager, Washington insisted that the terms of an agent's employment and his instructions be precise and in writing. He emphasized his desire for receiving written, rather than verbal, reports. He demanded repeatedly that intelligence reports be expedited, reminding his officers of those bits of intelligence he had received which had become valueless because of delay in getting them to him. He also recognized the need for developing many different sources so that their reports could be cross-checked, and so that the compromise of one source would not cut off the flow of intelligence from an important area.

Washington sought and obtained a "secret service fund" from the Continental Congress. He strongly wanted gold or silver. In accounting for the sums in his journals, he did not identify the recipients: "The names of persons who are employed within the Enemy's lines or who may fall within their power cannot be inserted." He instructed his generals to "leave no stone unturned, nor do not stick to expense" in gathering intelligence, and urged that those employed for intelligence purposes be those "upon whose firmness and fidelity we may safely rely."

Boston

After theBattles of Lexington and Concord

The Battles of Lexington and Concord were the first military engagements of the American Revolutionary War. The battles were fought on April 19, 1775, in Middlesex County, Province of Massachusetts Bay, within the towns of Lexington, Concord, ...

near Boston in April 1775, the colonies went to war. Washington appeared at the Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress was a late-18th-century meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolutionary War. The Congress was creating a new country it first named "United Colonies" and in 1 ...

in a military uniform, signaling that he was prepared for war. Congress created the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

on June 14, 1775, and discussed who should lead it. Washington had the prestige, military experience, charisma and military bearing of a military leader and was known as a strong patriot; he was also popular in his home province. There was no other serious competition for the post, although Washington did nothing to actively pursue the appointment. Massachusetts delegate John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

nominated Washington, believing that appointing a southerner to lead what was then primarily an army of northerners would help unite the colonies. Washington reluctantly accepted, declaring "with the utmost sincerity, I do not think myself equal to the Command I mhonored with."

Washington assumed command of the colonial forces outside Boston on July 3, 1775, during the ongoing

Washington assumed command of the colonial forces outside Boston on July 3, 1775, during the ongoing siege of Boston

The siege of Boston (April 19, 1775 – March 17, 1776) was the opening phase of the American Revolutionary War. New England militiamen prevented the movement by land of the British Army, which was garrisoned in what was then the peninsular town ...

, after stopping in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

to begin organizing military companies for its defense. His first steps were to establish procedures and to weld what had begun as militia regiments into an effective fighting force. He was assisted in this effort by his adjutant, Brigadier General Horatio Gates

Horatio Lloyd Gates (July 26, 1727April 10, 1806) was a British-born American army officer who served as a general in the Continental Army during the early years of the Revolutionary War. He took credit for the American victory in the Battl ...

, and Major General Charles Lee, both of whom had significant experience serving in the British Army.

When inventory returns exposed a dangerous shortage of gunpowder, Washington asked for new sources. British arsenals were raided (including some in the West Indies) and some manufacturing was attempted; a barely adequate supply (about 2.5 million pounds) was obtained by the end of 1776, mostly from France. In search of heavy weapons, he sent Henry Knox

Henry Knox (July 25, 1750 – October 25, 1806), a Founding Father of the United States, was a senior general of the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, serving as chief of artillery in most of Washington's campaigns. Following th ...

on an expedition to Fort Ticonderoga

Fort Ticonderoga (), formerly Fort Carillon, is a large 18th-century star fort built by the French at a narrows near the south end of Lake Champlain, in northern New York, in the United States. It was constructed by Canadian-born French milit ...

to retrieve cannons that had been captured there. He resisted repeated calls from Congress to launch attacks against the British in Boston, calling war councils that supported the decisions against such action. Before the Continental Navy

The Continental Navy was the navy of the United States during the American Revolutionary War and was founded October 13, 1775. The fleet cumulatively became relatively substantial through the efforts of the Continental Navy's patron John Ad ...

was established in November 1775 he, without Congressional authorization, began arming a "secret navy" to prey on poorly protected British transports and supply ships. When Congress authorized an invasion of Quebec, believing that province's people would also rise against British military control, Washington reluctantly went along with it, even authorizing Benedict Arnold

Benedict Arnold ( Brandt (1994), p. 4June 14, 1801) was an American military officer who served during the Revolutionary War. He fought with distinction for the American Continental Army and rose to the rank of major general before defect ...

to lead a force from Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

to Quebec City

Quebec City ( or ; french: Ville de Québec), officially Québec (), is the capital city of the Canadian province of Quebec. As of July 2021, the city had a population of 549,459, and the metropolitan area had a population of 839,311. It is t ...

through the wilderness of present-day Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and nor ...

.

As the siege dragged on, the matter of expiring enlistments became a matter of serious concern. Washington tried to convince Congress that enlistments longer than one year were necessary to build an effective fighting force, but he was rebuffed in this effort. The 1776 establishment of the Continental Army only had enlistment terms of one year, a matter that would again be a problem in late 1776.

Washington finally forced the British to withdraw from Boston by putting Henry Knox's artillery on Dorchester Heights overlooking the city, and preparing in detail to attack the city from Cambridge if the British tried to assault the position. The British evacuated Boston and sailed away, although Washington did not know they were headed for Halifax, Nova Scotia

Halifax is the capital and largest municipality of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and the largest municipality in Atlantic Canada. As of the 2021 Census, the municipal population was 439,819, with 348,634 people in its urban area. Th ...

. Believing they were headed for New York City (which was indeed Major General William Howe's eventual destination), Washington rushed most of the army there.

New York and New Jersey Campaign

Washington's success in Boston was not repeated in New York. Congress insisted that he defend it and recognizing the city's importance as a naval base and gateway to theHudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between Ne ...

, Washington delegated the task of fortifying New York to Charles Lee in February 1776. The faltering military campaign in Quebec also led to calls for additional troops there, and Washington detached six regiments northward under John Sullivan in April. The wider theaters of war had also introduced regional frictions into the army. Somewhat surprised that regional differences would be a problem, on August 1 he read a speech to the army, in which he threatened to punish "any officers or soldiers so lost to virtue and a love of their country" that might exacerbate the regional differences.Flexner (1968), p. 93 The mixing of forces from different regions also brought more widespread camp diseases, especially dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

and smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

.

Washington had to deal with his first major command controversy while in New York, which was partially a product of regional friction. New England troops serving in northern New York under General Philip Schuyler

Philip John Schuyler (; November 18, 1804) was an American general in the Revolutionary War and a United States Senator from New York. He is usually known as Philip Schuyler, while his son is usually known as Philip J. Schuyler.

Born in Alb ...

, a scion of an old patroon

In the United States, a patroon (; from Dutch '' patroon'' ) was a landholder with manorial rights to large tracts of land in the 17th century Dutch colony of New Netherland on the east coast of North America. Through the Charter of Freedoms ...

family of New York, objected to his aristocratic style, and their Congressional representatives lobbied Washington to replace Schuyler with General Gates. Washington tried to resolve the issue by giving Gates command of the forces in Quebec, but the collapse of the Quebec expedition brought renewed complaints. Despite Gates' experience, Washington personally preferred Schuyler. To avoid a potentially messy situation, General Washington gave Schuyler overall command of the northern department, but assigned Gates as second in command with combat authority. The episode exposed Washington to Gates' desire for advancement, possibly at his expense, and to the latter's influence in Congress.

Loss of New York City

General Howe's army, reinforced by thousands of additional troops from Europe and a fleet under the command of his brother, AdmiralRichard Howe

Admiral of the Fleet Richard Howe, 1st Earl Howe, (8 March 1726 – 5 August 1799) was a British naval officer. After serving throughout the War of the Austrian Succession, he gained a reputation for his role in amphibious operations a ...

, began arriving the entrance of New York Harbor

New York Harbor is at the mouth of the Hudson River where it empties into New York Bay near the East River tidal estuary, and then into the Atlantic Ocean on the east coast of the United States. It is one of the largest natural harbors in ...

(at the Narrows

__NOTOC__

The Narrows is the tidal strait separating the boroughs of Staten Island and Brooklyn in New York City, United States. It connects the Upper New York Bay and Lower New York Bay and forms the principal channel by which the Hudson Riv ...

), in early July, and made an unopposed landing on Staten Island

Staten Island ( ) is a Boroughs of New York City, borough of New York City, coextensive with Richmond County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. Located in the city's southwest portion, the borough is separated from New Jersey b ...

. Without intelligence about Howe's intentions, Washington was forced to divide his still poorly trained forces, principally between Manhattan and Long Island. The Howes, who were politically ambivalent about the conflict, had been authorized to act as peace commissioners, and attempted to establish contact with Washington. However, they refused to address their letters to "General George Washington", and his representatives refused to accept them.

In August, the British finally launched their campaign to capture New York City. They first landed on Long Island in force, and flanked Washington's forward positions in the

In August, the British finally launched their campaign to capture New York City. They first landed on Long Island in force, and flanked Washington's forward positions in the Battle of Long Island

The Battle of Long Island, also known as the Battle of Brooklyn and the Battle of Brooklyn Heights, was an action of the American Revolutionary War fought on August 27, 1776, at the western edge of Long Island in present-day Brooklyn, New Yor ...

. General Howe refused to act on a significant tactical advantage that could have resulted in the capture of the remaining Continental troops on Long Island, but he chose instead to besiege the fortified positions to which they had retreated. Although Washington has been criticized by many historians for sending additional troops to reinforce the redoubts on Long Island, it was clear to both Washington and the Howes that the Americans had successfully blocked the East River

The East River is a saltwater tidal estuary in New York City. The waterway, which is actually not a river despite its name, connects Upper New York Bay on its south end to Long Island Sound on its north end. It separates the borough of Quee ...

against major shipping by sinking ships in the channel, and that he was consequently not risking the entrapment of additional men. In the face of a siege he seemed certain to lose, Washington then decided to withdraw. In what some historians call one of his greatest military feats, he executed a nighttime withdrawal from Long Island across the East River

The East River is a saltwater tidal estuary in New York City. The waterway, which is actually not a river despite its name, connects Upper New York Bay on its south end to Long Island Sound on its north end. It separates the borough of Quee ...

to Manhattan to save those troops and materiel

Materiel (; ) refers to supplies, equipment, and weapons in military supply-chain management, and typically supplies and equipment in a commercial supply chain context.

In a military context, the term ''materiel'' refers either to the spec ...

.

The Howe brothers then paused to consolidate their position, and the admiral engaged in a fruitless peace conference with Congressional representatives on September 11. Four days later the British landed on Manhattan, a bombardment from the river scattering inexperienced militia into a panicked retreat, and forcing Washington to retreat further.Fischer, pp. 102–107 After Washington stopped the British advance up Manhattan at Harlem Heights on September 16, Howe again made a flanking maneuver, landing troops at Pell's Point in a bid to cut off Washington's avenue of retreat. To defend against this move, Washington withdrew most of his army to White Plains, where after a short battle on October 28 he retreated further north. This isolated the remaining Continental Army troops in upper Manhattan, so Howe returned to Manhattan and captured Fort Washington in mid November, taking almost 3,000 prisoners. Four days later, Fort Lee, across the Hudson River from Fort Washington, was also taken. Washington brought much of his army across the Hudson into New Jersey, but was immediately forced to retreat by the aggressive British advance.

During the campaign a general lack of organization, shortages of supplies, fatigue, sickness, and above all, lack of confidence in the American leadership resulted in a melting away of untrained regulars and frightened militia. Washington grumbled, "The honor of making a brave defense does not seem to be sufficient stimulus, when the success is very doubtful, and the falling into the Enemy's hands probable." Washington was fortunate that General Howe was more focused on gaining control of New York than on destroying Washington's army. Howe's overly rigid adherence to his plans meant that he was unable to capitalize on the opportunities that arose during the campaign for a decisive action against Washington.

Counterattack in New Jersey

After the loss of New York, Washington's army was in two pieces. One detachment remained north of New York to protect the Hudson River corridor, while Washington retreated across New Jersey into Pennsylvania, chased by General Charles, Earl Cornwallis. Spirits were low, popular support was wavering, and Congress had abandoned Philadelphia, fearing a British attack. Washington ordered General Gates to bring troops from Fort Ticonderoga, and also ordered General Lee's troops, which he had left north of New York City, to join him. Lee, whose relationship with Washington was at times difficult, made excuses and only traveled as far asMorristown, New Jersey

Morristown () is a town and the county seat of Morris County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.Banastre Tarleton

Sir Banastre Tarleton, 1st Baronet, GCB (21 August 175415 January 1833) was a British general and politician. He is best known as the lieutenant colonel leading the British Legion at the end of the American Revolution. He later served in Portu ...

surrounded the inn where he was staying and took him prisoner. Lee's command was taken over by John Sullivan, who finished marching the army to Washington's camp across the river from Trenton.

The capture of Lee resulted an important point in negotiations between the sides concerning the treatment of prisoners. Since Lee had previously served in the British Army, he was treated as a deserter

Desertion is the abandonment of a military duty or post without permission (a pass, liberty or leave) and is done with the intention of not returning. This contrasts with unauthorized absence (UA) or absence without leave (AWOL ), which ...

, and threatened with military punishments appropriate to that charge. Even though he and Lee did not get on well, Washington threatened to treat captured British officers in the same manner Lee and other high-profile prisoners were treated. This resulted in an improvement in Lee's captivity, and he was eventually exchanged for Richard Prescott

Lieutenant General Richard Prescott (1725–1788) was a British officer, born in England.

Military career

He was appointed a major of the 33rd Regiment of Foot, on 20 December 1756, transferred to the 72nd Regiment of Foot on 9 May 1758, and ...

in 1778.

Despite the loss of troops due to desertion and expiring enlistments, Washington was heartened by a rise in militia enlistments in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. These militia companies were active in circumscribing the furthest outposts of the British, limiting their ability to scout and forage. Although Washington did not coordinate this resistance, he took advantage of it to organize an attack on an outpost of Hessians in Trenton. On the night of December 25–26, 1776, Washington led his forces across the Delaware River and surprised the Hessian garrison the following morning, capturing 1,000 men.

This action significantly boosted the army's morale, but it also brought Cornwallis out of New York. He reassembled an army of more than 6,000 men, and marched most of them against a position Washington had taken south of Trenton. Leaving a garrison of 1,200 at

This action significantly boosted the army's morale, but it also brought Cornwallis out of New York. He reassembled an army of more than 6,000 men, and marched most of them against a position Washington had taken south of Trenton. Leaving a garrison of 1,200 at Princeton

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the nin ...

, Cornwallis then attacked Washington's position on January 2, 1777, and was three times repulsed before darkness set in. During the night Washington evacuated the position, masking his army's movements by instructing the camp guards to maintain the appearance of a much larger force. Washington then circled around Cornwallis's position with the intention of attacking the Princeton garrison.

On January 3, Hugh Mercer, leading the American advance guard, encountered British soldiers from Princeton under the command of Charles Mawhood

Lt. Col. Charles Mawhood (23 December 1729 – 29 August 1780) was a British army officer during the 18th century, most noted for his command during the Battle of Princeton.

Military career

His military service began with purchase of a corn ...

. The British troops engaged Mercer and in the ensuing battle, Mercer was mortally wounded. Washington sent reinforcements under General John Cadwalader, which were successful in driving Mawhood and the British from Princeton, with many of them fleeing to Cornwallis in Trenton. The British lost more than one quarter of their force in the battle, and American morale rose with the victory.

These unexpected victories drove the British back to the New York City area, and gave a dramatic boost to Revolutionary morale. During the winter, Washington, based in winter quarters at Morristown, loosely coordinated a low-level militia war against British positions in New Jersey, combining the actions of New Jersey and Pennsylvania militia companies with careful use of Continental Army resources to harry and harass the British and German troops quartered in New Jersey.

Washington's mixed performance in the 1776 campaigns had not led to significant criticism in Congress. Before fleeing Philadelphia for Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was ...

in December, Congress granted Washington powers that have ever since been described as "dictatorial". The successes in New Jersey nearly deified Washington in the eyes of some Congressmen, and the body became much more deferential to him as a result. John Adams complained of the "superstitious veneration" that Washington was receiving.Ferling (2010), p. 125 Washington's performance also received international notice: Frederick the Great

Frederick II (german: Friedrich II.; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was King in Prussia from 1740 until 1772, and King of Prussia from 1772 until his death in 1786. His most significant accomplishments include his military successes in the Sil ...

, one of the greatest military minds, wrote that "the achievements of Washington t Trenton and Princetonwere the most brilliant of any recorded in the history of military achievements." The French foreign minister, a strong supporter of the American cause, renewed the delivery of French supplies.

Philadelphia and Valley Forge

Early maneuvers

In May 1777, uncertain whether General Howe would move north toward Albany or south toward Philadelphia, Washington moved his army to theMiddlebrook encampment "Middlebrook encampment" may refer to one of two different seasonal stays of the Continental Army in central New Jersey near the Middlebrook in Bridgewater Township in Somerset County. They are usually differentiated by either the date of the encamp ...

in New Jersey's Watchung Mountains

The Watchung Mountains (once called the Blue Hills) are a group of three long low ridges of volcanic origin, between high, lying parallel to each other in northern New Jersey in the United States. The name is derived from the American Native Lena ...

. When Howe then moved his army southwest from New Brunswick, Washington correctly interpreted this as a move to draw him out of his strong position, and refused to move. Only after Howe apparently retreated back toward the shore did Washington follow, but Howe's attempt to separate him from his mountain defenses was foiled in the Battle of Short Hills

The Battle of Short Hills (also known as the Battle of Metuchen Meetinghouse and other names) was a conflict between a Continental Army force commanded by Brigadier General William Alexander ("Lord Stirling"), and an opposing British force comm ...

in late June. Howe, who had already decided to campaign against Philadelphia, then withdrew from New Jersey, embarked much of his army on ships in late July, and sailed away, leaving Washington mystified as to his destination.

Washington's difficulty in discerning Howe's motives was due to the presence of a British army moving south from Quebec toward Fort Ticonderoga under the command of General

Washington's difficulty in discerning Howe's motives was due to the presence of a British army moving south from Quebec toward Fort Ticonderoga under the command of General John Burgoyne

General John Burgoyne (24 February 1722 – 4 August 1792) was a British general, dramatist and politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1761 to 1792. He first saw action during the Seven Years' War when he participated in several bat ...

. Howe's departure was in part prompted by the successful capture of the fort by Burgoyne in early July. Although there had been an expectation on Burgoyne's part that Howe would support his campaign to gain control of the Hudson, Howe was to disappoint Burgoyne, with disastrous consequences to the British. When Washington learned of the abandonment of Ticonderoga (which he had been told by General Anthony Wayne

Anthony Wayne (January 1, 1745 – December 15, 1796) was an American soldier, officer, statesman, and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. He adopted a military career at the outset of the American Revolutionary War, where his mil ...

"can never be carried, without much loss of blood"), he was shocked. Concerned that Howe was heading up the Hudson, he ordered three of his best officers northwards, Benedict Arnold,Leckie, p. 387 Benjamin Lincoln

Benjamin Lincoln (January 24, 1733 ( O.S. January 13, 1733) – May 9, 1810) was an American army officer. He served as a major general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. Lincoln was involved in three major surrenders ...

, and Daniel Morgan

Daniel Morgan (1735–1736July 6, 1802) was an American pioneer, soldier, and politician from Virginia. One of the most respected battlefield tacticians of the American Revolutionary War of 1775–1783, he later commanded troops during the sup ...

and his corps of riflemen. He also sent 750 men from Israel Putnam

Israel Putnam (January 7, 1718 – May 29, 1790), popularly known as "Old Put", was an American military officer and landowner who fought with distinction at the Battle of Bunker Hill during the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783). He als ...

's forces north to assist General Gates with the defense of the Hudson.

Washington had had some difficulty with General Arnold in the spring. Congress had adopted a per-state scheme for the promotion of general officers, which resulted in the promotion of several officers to major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

ahead of other officers with more experience or seniority. Combined with the commissioning of foreign officers to high ranks, this had led to the resignation of John Stark. Arnold, who had distinguished himself in the Canadian campaign, had also threatened to resign. Washington wrote to Congress on behalf of Arnold and other officers who were disgruntled by this promotion scheme, stating that "two or three other very good officers" might be lost because of it. Washington had also laid the seeds for conflict between Arnold and Gates when he gave Arnold command of forces in Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

in late 1776; because of this move Gates came to view Arnold as a competitor for advancement, and the previously positive relationship between Gates and Arnold cooled. However, Arnold put aside his complaints when the news of Ticonderoga's fall arrived, and agreed to serve.

Congress, at the urging of its diplomatic representatives in Europe, had also issued military commissions to a number of European soldiers of fortune in early 1777. Two of those recommended by Silas Deane

Silas Deane (September 23, 1789) was an American merchant, politician, and diplomat, and a supporter of American independence. Deane served as a delegate to the Continental Congress, where he signed the Continental Association, and then became the ...

, the Marquis de Lafayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (, ), was a French aristocrat, freemason and military officer who fought in the American Revolutio ...

and Thomas Conway

Thomas Conway (February 27, 1735 – c. 1800) served as a major general in the American Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. He became involved with the alleged Conway Cabal with Horatio Gates. He later served with Émigré for ...

, would prove to be important in Washington's activities. Lafayette, just twenty years old, was at first told that Deane had exceeded his authority in offering him a major general's commission, but offered to volunteer in the army at his own expense. Washington and Lafayette took an instant liking to one another when they met, and Lafayette became one of Washington's most trusted generals and confidants. Conway, on the other hand, did not think highly of Washington's leadership, and proved to be a source of trouble in the 1777 campaign season and its aftermath.

Fall of Philadelphia

When Washington learned that Howe's fleet was sailing north inChesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the Eastern Shore of Maryland / ...

, he hurried his army south of Philadelphia to defend the city against Howe's threat. General Howe turned Washington's flank at the Battle of Brandywine

The Battle of Brandywine, also known as the Battle of Brandywine Creek, was fought between the American Continental Army of General George Washington and the British Army of General William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe, Sir William Howe on September& ...

on September 11, 1777, and marched unopposed into Philadelphia on September 26 after some further maneuvers. Washington's failure to defend the capital brought on a storm of criticism from Congress, which fled the city for York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

, and from other army officers. In part to silence his critics, Washington planned an elaborate assault on an exposed British base in Germantown Germantown or German Town may refer to:

Places

Australia

* Germantown, Queensland, a locality in the Cassowary Coast Region

United States

* Germantown, California, the former name of Artois, a census-designated place in Glenn County

* G ...

. The October 4 Battle of Germantown

The Battle of Germantown was a major engagement in the Philadelphia campaign of the American Revolutionary War. It was fought on October 4, 1777, at Germantown, Pennsylvania, between the British Army led by Sir William Howe, and the American Con ...

failed in part due to the complexity of the assault, and the inexperience of the militia forces employed in it. Over 400 of Washington's men were captured, including Colonel George Mathews and the entire 9th Virginia Regiment.Jenkins, Charles F. (1904) ''The Guide Book to Historic Germantown'', Innes & Sons, 1904.Jenkins, Charles F. ''The Guide Book to Historic Germantown'', Innes & Sons, 1904. p 142. It did not help that Adam Stephen

Adam Stephen ( – 16 July 1791) was a Scottish-born American doctor and military officer who helped found what became Martinsburg, West Virginia. He emigrated to North America, where he served in the Province of Virginia's militia under Georg ...

, leading one of the branches of the attack, was drunk, and broke from the agreed-upon plan of attack. He was court martialed and cashiered from the army. Historian Robert Leckie observes that the battle was a near thing, and that a small number of changes might have resulted in a decisive victory for Washington.

Meanwhile, Burgoyne, out of reach from help from Howe, was trapped and forced to surrender his entire army on October 17, ten days after the

Meanwhile, Burgoyne, out of reach from help from Howe, was trapped and forced to surrender his entire army on October 17, ten days after the Battle of Bemis Heights

The Battles of Saratoga (September 19 and October 7, 1777) marked the climax of the Saratoga campaign, giving a decisive victory to the Americans over the British in the American Revolutionary War. British General John Burgoyne led an invasion ...

. The victory made a hero of General Gates, who received the adulation of Congress. While this was taking place Washington presided from a distance over the loss of control of the Delaware River to the British, and marched his army to its winter quarters at Valley Forge

Valley Forge functioned as the third of eight winter encampments for the Continental Army's main body, commanded by General George Washington, during the American Revolutionary War. In September 1777, Congress fled Philadelphia to escape the ...

in December. Washington chose Valley Forge, over recommendations that he camp either closer or further from Philadelphia, because it was close enough to monitor British army movements, and protected rich farmlands to the west from the enemy's foraging expeditions.

Valley Forge

Washington's army stayed at Valley Forge for the next six months. Over the winter, 2,500 men (out of 10,000) died from disease and exposure. The army's difficulties were exacerbated by a number of factors, including a quartermaster's department that had been badly mismanaged by one of Washington's political opponents,Thomas Mifflin

Thomas Mifflin (January 10, 1744January 20, 1800) was an American merchant, soldier, and politician from Pennsylvania, who is regarded as a Founding Father of the United States for his roles during and after the American Revolution. Mifflin wa ...

, and the preference of farmers and merchants to sell their goods to the British for hard currency instead of the nearly worthless Continental currency. Profiteers also sought to benefit at the army's expense, charging it 1,000 times what they charged civilians for the same goods. Congress authorized Washington to seize supplies needed for the army, but he was reluctant to use such authority, since it smacked of the tyranny the war was supposedly being fought over.Leckie, p. 435

During the winter he introduced a full-scale training program supervised by Baron von Steuben

Friedrich Wilhelm August Heinrich Ferdinand von Steuben (born Friedrich Wilhelm Ludolf Gerhard Augustin Louis von Steuben; September 17, 1730 – November 28, 1794), also referred to as Baron von Steuben (), was a Prussian military officer who p ...

, a veteran of the Prussian general staff. Despite the hardships the army suffered, this program was a remarkable success, and Washington's army emerged in the spring of 1778 a much more disciplined force.

Washington himself had to face discontent at his leadership from a variety of sources. His loss of Philadelphia prompted some members of Congress to discuss removing him from command. They were prodded along by Washington's detractors in the military, who included Generals Gates, Mifflin, and Conway.Chernow, p. 320 Gates in particular was viewed by Conway and Congressmen Benjamin Rush

Benjamin Rush (April 19, 1813) was a Founding Father of the United States who signed the United States Declaration of Independence, and a civic leader in Philadelphia, where he was a physician, politician, social reformer, humanitarian, educa ...

and Richard Henry Lee

Richard Henry Lee (January 20, 1732June 19, 1794) was an American statesman and Founding Father from Virginia, best known for the June 1776 Lee Resolution, the motion in the Second Continental Congress calling for the colonies' independence f ...

as a desirable replacement for Washington. Although there is no evidence of a formal conspiracy, the episode is known as the Conway Cabal

The Conway Cabal was a group of senior Continental Army officers in late 1777 and early 1778 who aimed to have George Washington replaced as commander-in-chief of the Army during the American Revolutionary War. It was named after Brigadier Gene ...

because the scale of the discontent within the army was exposed by a critical letter from Conway to Gates, some of whose contents were relayed to Washington. Washington exposed the criticisms to Congress, and his supporters, within Congress and the army, rallied to support him. Gates eventually apologized for his role in the affair, and Conway resigned. Washington's position and authority were not seriously challenged again. Biographer Ron Chernow points out that Washington's handling of the episode demonstrated that he was "a consummate political infighter" who maintained his temper and dignity while his opponents schemed.

French entry into the war

The victory at Saratoga (and to some extent Washington's near success at Germantown) were influential in convincing France to enter the war openly as an American ally. French entry into the war changed its dynamics, for the British were no longer sure of command of the seas and had to worry about an invasion of their home islands and other colonial territories across the globe. The British, now under the command of General Sir Henry Clinton, evacuated Philadelphia in 1778 and returned to New York City, with Washington attacking them along the way at theBattle of Monmouth

The Battle of Monmouth, also known as the Battle of Monmouth Court House, was fought near Monmouth Court House in modern-day Freehold Borough, New Jersey on June 28, 1778, during the American Revolutionary War. It pitted the Continental Army, co ...

; this was the last major battle in the north. Prior to the battle Washington gave command of the advance forces to Charles Lee, who had been exchanged earlier in the year. Lee, despite firm instructions from Washington, refused Lafayette's suggestion to launch an organized attack on the British rear, and then retreated when the British turned to face him. When Washington arrived at the head of the main army, he and Lee had an angry exchange of words, and Washington ordered Lee off the command. Washington, with his army's tactics and ability to execute improved by the training programs of the previous winter, was able to recover, and fought the British to a draw. Lee was court martialed and eventually dismissed from the army.

Not long after Clinton's return to New York, a French fleet arrived off the North American coast. Washington was involved in the discussion on how to best use this force, and an attack was planned against the British outpost at Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is an American seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, and northeast of New Yor ...

. Despite the presence of two of Washington's most reliable subordinates, Lafayette and Greene, the attempt at cooperation was a dismal failure. British and Indian forces organized and supported by Sir Frederick Haldimand

Sir Frederick Haldimand, KB (11 August 1718 – 5 June 1791) was a military officer best known for his service in the British Army in North America during the Seven Years' War and the American Revolutionary War. From 1778 to 1786, he serve ...

in Quebec began to raid frontier settlements in 1778, and Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Br ...

was captured late in the year.

During the comparatively mild winter of 1778–79, Washington and Congress discussed options for the 1779 campaign season. The possibility of a Franco-American campaign against Quebec, first proposed for 1778, had a number of adherents in Congress, and was actively supported by Lafayette in Washington's circle. Despite known weaknesses in Quebec's provincial defenses, Washington was adamantly opposed to the idea, citing the lack of troops and supplies with which to conduct such an operation, the nation's fragile financial state, and French imperial ambitions to recover the territory. Under pressure from Congress to answer the frontier raids, Washington countered with the proposal of a major expedition against the Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian Peoples, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Indigenous confederations in North America, confederacy of First Nations in Canada, First Natio ...

. This was approved, and in the summer of 1779 a sizable force under Major General John Sullivan made a major expedition into the northwestern frontier of New York in reprisal for the frontier raids. The expedition successfully drove the Iroquois out of New York, but otherwise had little effect on the frequency and severity of frontier raids.

Washington's opponent in New York, however, was not inactive. Clinton engaged in a number of amphibious raids against coastal communities from