George S. Patton slapping incidents on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In early August 1943,

In early August 1943,

The August 10 incident—particularly the sight of Patton threatening a subordinate with a pistol—upset many of the medical staff present. The II Corps surgeon, Colonel Richard T. Arnest, submitted a report on the incident to Brigadier General

The August 10 incident—particularly the sight of Patton threatening a subordinate with a pistol—upset many of the medical staff present. The II Corps surgeon, Colonel Richard T. Arnest, submitted a report on the incident to Brigadier General

Patton was passed over to lead the invasion in northern Europe. In September, Patton's junior in both rank and was selected to command the

Patton was passed over to lead the invasion in northern Europe. In September, Patton's junior in both rank and was selected to command the

In early August 1943,

In early August 1943, Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on th ...

George S. Patton

George Smith Patton Jr. (November 11, 1885 – December 21, 1945) was a general in the United States Army who commanded the Seventh United States Army in the Mediterranean Theater of World War II, and the Third United States Army in France ...

slapped two United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

soldiers under his command during the Sicily Campaign

The Allied invasion of Sicily, also known as Operation Husky, was a major campaign of World War II in which the Allied forces invaded the island of Sicily in July 1943 and took it from the Axis powers ( Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany). It b ...

of World War II. Patton's hard-driving personality and lack of belief in the medical condition of combat stress reaction

Combat stress reaction (CSR) is acute behavioral disorganization as a direct result of the trauma of war. Also known as "combat fatigue", "battle fatigue", or "battle neurosis", it has some overlap with the diagnosis of acute stress reaction used ...

, then known as "battle fatigue" or "shell shock

Shell shock is a term coined in World War I by the British psychologist Charles Samuel Myers to describe the type of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) many soldiers were afflicted with during the war (before PTSD was termed). It is a react ...

", led to the soldiers' becoming the subject of his ire in incidents on August 3 and 10, when Patton struck and berated them after discovering they were patients at evacuation hospitals away from the front lines without apparent physical injuries.

Word of the incidents spread, eventually reaching Patton's superior, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, who ordered him to apologize to the men. Patton's actions were initially suppressed in the news until journalist Drew Pearson publicized them in the United States. While the reactions of the U.S. Congress and the general public were divided between support and disdain for Patton's actions, Eisenhower and Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall opted not to fire Patton as a commander.

Seizing the opportunity the predicament presented, Eisenhower used Patton as a decoy in Operation Fortitude

Operation Fortitude was the code name for a World War II military deception employed by the Allied nations as part of an overall deception strategy (code named ''Bodyguard'') during the build-up to the 1944 Normandy landings. Fortitude was di ...

, sending faulty intelligence to German agents that Patton was leading the Invasion of Europe

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 (D-Day) with the Nor ...

. While Patton eventually returned to combat command in the European Theater

The European theatre of World War II was one of the two main theatres of combat during World War II. It saw heavy fighting across Europe for almost six years, starting with Germany's invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939 and ending with the ...

in mid-1944, the slapping incidents were seen by Eisenhower, Marshall, and other leaders to be examples of Patton's brashness and impulsiveness.

Background

TheAllied invasion of Sicily

The Allied invasion of Sicily, also known as Operation Husky, was a major campaign of World War II in which the Allied forces invaded the island of Sicily in July 1943 and took it from the Axis powers ( Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany). It b ...

began on July 10, 1943, with Lieutenant General George S. Patton leading 90,000 men of the Seventh United States Army

The Seventh Army was a United States army created during World War II that evolved into the United States Army Europe (USAREUR) during the 1950s and 1960s. It served in North Africa and Italy in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations and Fran ...

in a landing near Gela

Gela (Sicilian and ; grc, Γέλα) is a city and (municipality) in the Autonomous Region of Sicily, Italy; in terms of area and population, it is the largest municipality on the southern coast of Sicily. Gela is part of the Province of Ca ...

, Scoglitti

Scoglitti ( scn, Scugghitti) is a fishing village and hamlet () of Vittoria, a municipality in the Province of Ragusa, Sicily, Italy. In 2011 it had a population of 4,175.

History

Scoglitti found a niche in history after being selected by the A ...

, and Licata to support Bernard Montgomery

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, (; 17 November 1887 – 24 March 1976), nicknamed "Monty", was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War, the Irish War of Independence an ...

's British 8th Army

The Eighth Army was an Allied field army formation of the British Army during the Second World War, fighting in the North African and Italian campaigns. Units came from Australia, British India, Canada, Czechoslovakia, Free French Force ...

landings to the north. Initially ordered to protect the British forces' flank, Patton took Palermo

Palermo ( , ; scn, Palermu , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital of both the autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan province. The city is noted for its ...

after Montgomery's forces were slowed by heavy resistance from troops of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to ...

. Patton then set his sights on Messina

Messina (, also , ) is a harbour city and the capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of more than 219,000 inhabitants in t ...

. He sought an amphibious assault

Amphibious warfare is a type of offensive military operation that today uses naval ships to project ground and air power onto a hostile or potentially hostile shore at a designated landing beach. Through history the operations were conducted u ...

, but it was delayed by lack of landing craft and his troops did not land in Santo Stefano until August 8, by which time the Germans and Italians had already evacuated the bulk of their troops to mainland Italy. Throughout the campaign, Patton's troops were heavily engaged by German and Italian forces as they pushed across the island.

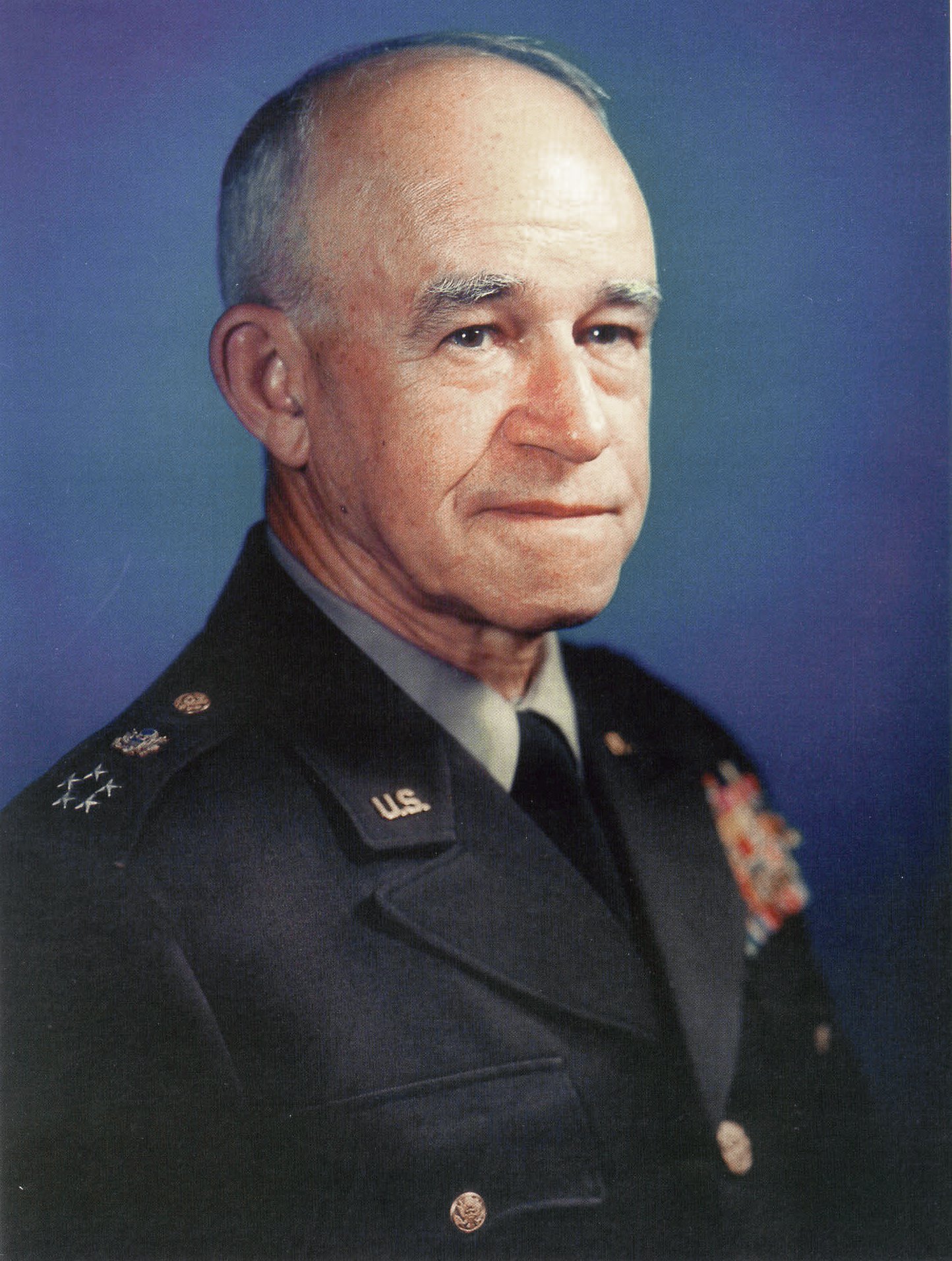

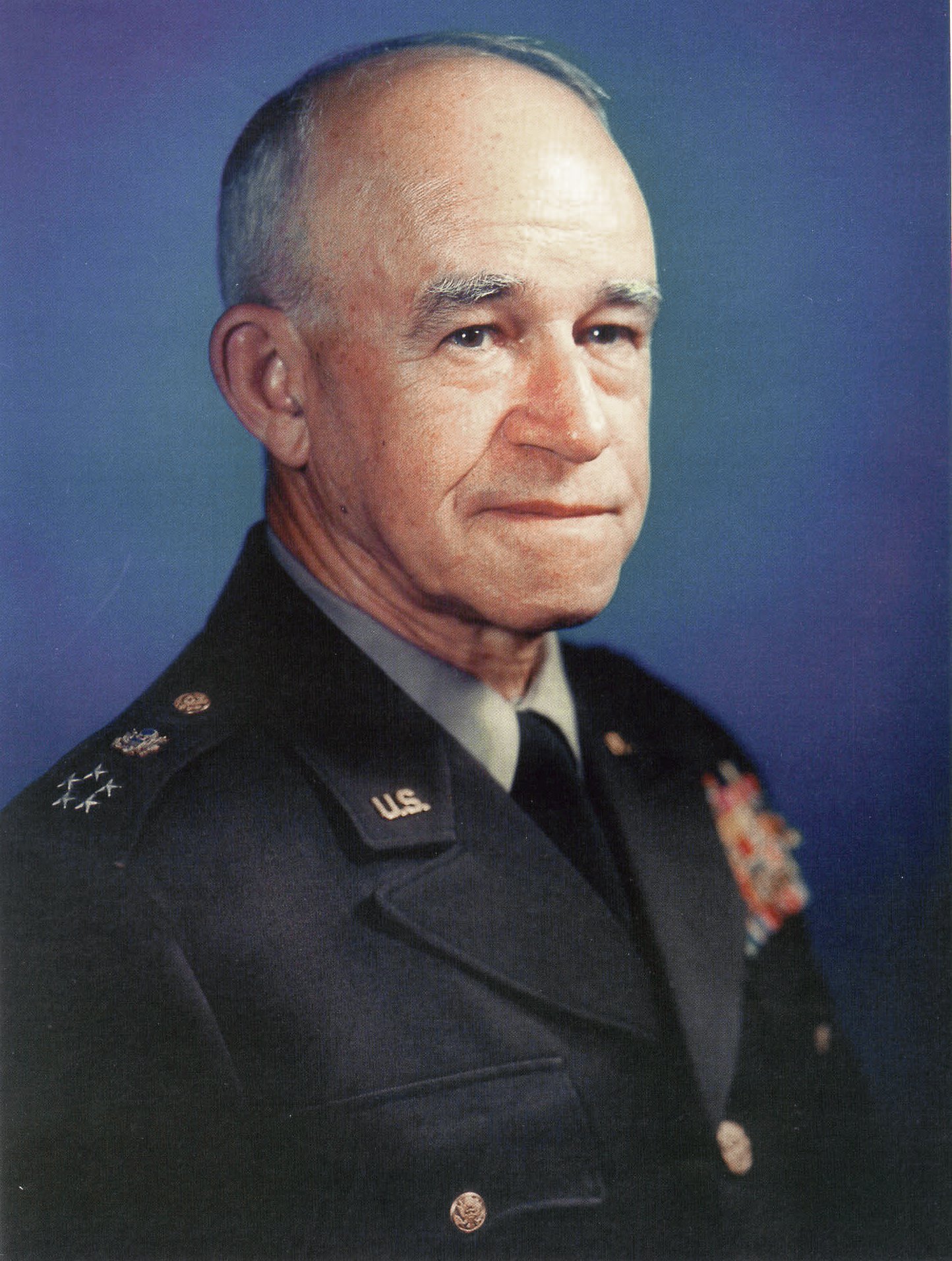

Patton had already developed a reputation in the U.S. Army as an effective, successful, and hard-driving commander, punishing subordinates for the slightest infractions but also rewarding them when they performed well. As a way to promote an image that inspired his troops, Patton created a larger-than-life personality. He became known for his flashy dress, highly polished helmet and boots, and no-nonsense demeanor. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the commander of the Sicily operation and Patton's friend and commanding officer, had long known of Patton's colorful leadership style, and also knew that Patton was prone to impulsiveness and a lack of self-restraint.

Battle fatigue

Prior to World War I, the U.S. Army considered the symptoms of battle fatigue to becowardice

Cowardice is a trait wherein excessive fear prevents an individual from taking a risk or facing danger. It is the opposite of courage. As a label, "cowardice" indicates a failure of character in the face of a challenge. One who succumbs to cowa ...

or attempts to avoid combat duty. Soldiers who reported these symptoms received harsh treatment. "Shell shock" had been diagnosed as a medical condition during World War I. But even before the conflict ended, what constituted shell shock was changing. This included the idea that it was caused by the shock of exploding shells. By World War II soldiers were usually diagnosed with "psychoneurosis" or "combat fatigue." Despite this, "shell shock" remained in the popular vocabulary. But the symptoms of what constituted combat fatigue were broader than what had constituted shell shock in World War I. By the time of the invasion of Sicily, the U.S. Army was initially classifying all psychological casualties as "exhaustion" which many still called shell shock. While the causes, symptoms, and effects of the condition were familiar to physicians by the time of the two incidents, it was generally less understood in military circles.

An important lesson from the Tunisia Campaign

The Tunisian campaign (also known as the Battle of Tunisia) was a series of battles that took place in Tunisia during the North African campaign of the Second World War, between Axis and Allied forces from 17 November 1942 to 13 May 1943. Th ...

was that neuropsychiatric

Neuropsychiatry or Organic Psychiatry is a branch of medicine that deals with psychiatry as it relates to neurology, in an effort to understand and attribute behavior to the interaction of neurobiology and social psychology factors. Within neurop ...

casualties had to be treated as soon as possible and not evacuated from the combat zone. This was not done in the early stages of the Sicilian Campaign, and large numbers of neuropsychiatric casualties were evacuated to North Africa, with the result that treatment became complicated and only 15 percent of them were returned to duty. As the campaign wore on, the system became better organized and nearly 50 percent were restored to combat duty.

Some time before what would become known as the "slapping incident," Patton spoke with Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

Clarence R. Huebner

Lieutenant General Clarence Ralph Huebner (November 24, 1888 – September 23, 1972) was a highly decorated senior officer of the United States Army who saw distinguished active service during both World War I and World War II. Perhaps his most ...

, the newly appointed commander of the U.S. 1st Infantry Division, in which both men served. Patton had asked Huebner for a status report; Huebner replied: "The front lines seem to be thinning out. There seems to be a very large number of ' malingerers' at the hospitals, feigning illness in order to avoid combat duty." For his part, Patton did not believe the condition was real. In a directive issued to commanders on August 5, he forbade "battle fatigue" in the Seventh Army:

Incidents

August 3

Private Charles H. Kuhl, of L Company, U.S. 26th Infantry Regiment, reported to an aid station of C Company, 1st Medical Battalion, on August 2, 1943. Kuhl, who had been in the U.S. Army for eight months, had been attached to the 1st Infantry Division since June 2, 1943. He was diagnosed with "exhaustion," a diagnosis he had been given three times since the start of the campaign. From the aid station, he was evacuated to a medical company and givensodium amytal

Amobarbital (formerly known as amylobarbitone or sodium amytal as the soluble sodium salt) is a drug that is a barbiturate derivative. It has sedative-hypnotic properties. It is a white crystalline powder with no odor and a slightly bitter taste. ...

. Notes in his medical chart indicated "psychoneurosis

Neurosis is a class of functional mental disorders involving chronic distress, but neither delusions nor hallucinations. The term is no longer used by the professional psychiatric community in the United States, having been eliminated from th ...

anxiety state, moderately severe (soldier has been twice before in hospital within ten days. He can't take it at the front, evidently. He is repeatedly returned.)" Kuhl was transferred from the aid station to the 15th Evacuation Hospital near Nicosia

Nicosia ( ; el, Λευκωσία, Lefkosía ; tr, Lefkoşa ; hy, Նիկոսիա, romanized: ''Nikosia''; Cypriot Arabic: Nikusiya) is the largest city, capital, and seat of government of Cyprus. It is located near the centre of the Mesaori ...

for further evaluation.

Patton arrived at the hospital the same day, accompanied by a number of medical officers, as part of his tour of the U.S. II Corps troops. He spoke to some patients in the hospital, commending the physically wounded. He then approached Kuhl, who did not appear to be physically injured. Kuhl was sitting slouched on a stool midway through a tent ward filled with injured soldiers. When Patton asked Kuhl where he was hurt, Kuhl reportedly shrugged and replied that he was "nervous" rather than wounded, adding, "I guess I can't take it." Patton "immediately flared up," slapped Kuhl across the chin with his gloves, then grabbed him by the collar and dragged him to the tent entrance. He shoved him out of the tent with a kick to his backside. Yelling "Don't admit this son of a bitch," Patton demanded that Kuhl be sent back to the front, adding, "You hear me, you gutless bastard? You're going back to the front."

Corpsmen picked up Kuhl and brought him to a ward tent, where it was discovered he had a temperature of ; and was later diagnosed with malarial parasite

''Plasmodium'' is a genus of unicellular eukaryotes that are obligate parasites of vertebrates and insects. The life cycles of ''Plasmodium'' species involve development in a blood-feeding insect host which then injects parasites into a verteb ...

s. Speaking later of the incident, Kuhl noted "at the time it happened, atton

Atton () is a commune in the Meurthe-et-Moselle department in northeastern France.

Population

See also

*Communes of the Meurthe-et-Moselle department

The following is a list of the 591 communes of the Meurthe-et-Moselle department of France ...

was pretty well worn out ... I think he was suffering a little battle fatigue himself." Kuhl wrote to his parents about the incident, but asked them to "just forget about it." That night, Patton recorded the incident in his diary: " metthe only errant coward I have ever seen in this Army. Companies should deal with such men, and if they shirk their duty, they should be tried for cowardice and shot."

Patton was accompanied in this visit by Major General John P. Lucas

Major General John Porter Lucas (January 14, 1890 – December 24, 1949) was a senior officer of the United States Army who saw service in World War I and World War II. He is most remembered for being the commander of VI Corps during the Battle of ...

, who saw nothing remarkable about the incident. After the war he wrote:

Patton was further heard by war correspondent Noel Monks angrily claiming that shell shock

Shell shock is a term coined in World War I by the British psychologist Charles Samuel Myers to describe the type of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) many soldiers were afflicted with during the war (before PTSD was termed). It is a react ...

is "an invention of the Jews."

August 10

Private Paul G. Bennett, 21, of C Battery, U.S. 17th Field Artillery Regiment, was a four-year veteran of the U.S. Army, and had served in the division since March 1943. Records show he had no medical history until August 6, 1943, when a friend was wounded in combat. According to a report, he "could not sleep and was nervous." Bennett was brought to the 93rd Evacuation Hospital. In addition to having a fever, he exhibited symptoms of dehydration, including fatigue, confusion, and listlessness. His request to return to his unit was turned down by medical officers. A medical officer describing Bennett's condition On August 10, Patton entered the receiving tent of the hospital, speaking to the injured there. Patton approached Bennett, who was huddled and shivering, and asked what the trouble was. "It's my nerves," Bennett responded. "I can't stand the shelling anymore." Patton reportedly became enraged at him, slapping him across the face. He began yelling: "Your nerves, hell, you are just a goddamned coward. Shut up that goddamned crying. I won't have these brave men who have been shot at seeing this yellow bastard sitting here crying." Patton then reportedly slapped Bennett again, knocking his helmet liner off, and ordered the receiving officer,Major

Major ( commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicato ...

Charles B. Etter, not to admit him. Patton then threatened Bennett, "You're going back to the front lines and you may get shot and killed, but you're going to fight. If you don't, I'll stand you up against a wall and have a firing squad kill you on purpose. In fact, I ought to shoot you myself, you goddamned whimpering coward." Upon saying this, Patton pulled out his pistol threateningly, prompting the hospital's commander, Colonel Donald E. Currier, to physically separate the two. Patton left the tent, yelling to medical officers to send Bennett back to the front lines.

As he toured the remainder of the hospital, Patton continued discussing Bennett's condition with Currier. Patton stated, "I can't help it, it makes my blood boil to think of a yellow bastard being babied," and "I won't have those cowardly bastards hanging around our hospitals. We'll probably have to shoot them some time anyway, or we'll raise a breed of morons."

Aftermath

Private reprimand and apologies

The August 10 incident—particularly the sight of Patton threatening a subordinate with a pistol—upset many of the medical staff present. The II Corps surgeon, Colonel Richard T. Arnest, submitted a report on the incident to Brigadier General

The August 10 incident—particularly the sight of Patton threatening a subordinate with a pistol—upset many of the medical staff present. The II Corps surgeon, Colonel Richard T. Arnest, submitted a report on the incident to Brigadier General William B. Kean

William Benjamin Kean (July 9, 1897 – March 10, 1981) was a general in the United States Army.

Early life

He was born William Benjamin Kean Jr. in Buffalo, New York on July 9, 1897. Kean graduated from the United States Military Academy in ...

, chief of staff of II Corps, who submitted it to Lieutenant General Omar Bradley, commander of II Corps. Bradley, out of loyalty to Patton, did nothing more than lock the report in his safe. Arnest also sent the report through medical channels to Brigadier General Frederick A. Blesse, General Surgeon of Allied Force Headquarters

Allied Force Headquarters (AFHQ) was the headquarters that controlled all Allied operational forces in the Mediterranean theatre of World War II from August 1942 until the end of the war in Europe in May 1945.

AFHQ was established in the Uni ...

, who then submitted it to Eisenhower, who received it on August 16. Eisenhower ordered Blesse to proceed immediately to Patton's command to ascertain the truth of the allegations. Eisenhower also formulated a delegation to investigate the incidents from the soldiers' points of view, including Major General John P. Lucas

Major General John Porter Lucas (January 14, 1890 – December 24, 1949) was a senior officer of the United States Army who saw service in World War I and World War II. He is most remembered for being the commander of VI Corps during the Battle of ...

, two colonels from the Inspector General

An inspector general is an investigative official in a civil or military organization. The plural of the term is "inspectors general".

Australia

The Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security (Australia) (IGIS) is an independent statutory of ...

's office, and a theater medical consultant, Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colon ...

Perrin H. Long, to investigate the incident and interview those involved. Long interviewed medical personnel who witnessed each incident, then filed a report entitled "Mistreatment of Patients in Receiving Tents of the 15th and 93rd Evacuation Hospitals" which extensively detailed Patton's actions at both hospitals.

By August 18, Eisenhower had ordered that Patton's Seventh Army be broken up, with a few of its units remaining garrisoned in Sicily. The majority of its combat forces would be transferred to the Fifth United States Army

Fifth is the ordinal form of the number five.

Fifth or The Fifth may refer to:

* Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, as in the expression "pleading the Fifth"

* Fifth column, a political term

* Fifth disease, a contagious rash tha ...

under Lieutenant General Mark W. Clark

Mark Wayne Clark (May 1, 1896 – April 17, 1984) was a United States Army officer who saw service during World War I, World War II, and the Korean War. He was the youngest four-star general in the US Army during World War II.

During World War I ...

. This had already been planned by Eisenhower, who had previously told Patton that his Seventh Army would not be part of the upcoming Allied invasion of Italy

The Allied invasion of Italy was the Allied amphibious landing on mainland Italy that took place from 3 September 1943, during the Italian campaign of World War II. The operation was undertaken by General Sir Harold Alexander's 15th Army ...

, scheduled for September. On August 20, Patton received a cable from Eisenhower regarding the arrival of Lucas at Palermo. Eisenhower told Patton it was "highly important" that he personally meet with Lucas as soon as possible, as Lucas would be carrying an important message. Before Lucas arrived, Blesse arrived from Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques d ...

to look into the health of the troops in Sicily. He was also ordered by Eisenhower to deliver a secret letter to Patton and investigate its allegations. In the letter, Eisenhower told Patton he had been informed of the slapping incidents. He said he would not be opening a formal investigation into the matter, but his criticism of Patton was sharp.

Eisenhower's letter to Patton, dated August 17, 1943:

Eisenhower noted that no formal record of the incidents would be retained at Allied Headquarters, save in his own secret files. Still, he strongly suggested Patton apologize to all involved. On August 21, Patton brought Bennett into his office; he apologized and the men shook hands. On August 22, he met with Currier as well as the medical staff who had witnessed the events in each unit and expressed regret for his "impulsive actions." Patton related to the medical staff a story of a friend from World War I who had committed suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and ...

after "skulking"; he stated he sought to prevent any recurrence of such an event. On August 23, he brought Kuhl into his office, apologized, and shook hands with him as well. After the apology, Kuhl said he thought Patton was "a great general," and that "at the time, he didn't know how sick I was." Currier later said Patton's remarks sounded like "no apology at all ut rather likean attempt to justify what he had done." Patton wrote in his diary that he loathed making the apologies, particularly when he was told by Bennett's brigade commander, Brigadier General John A. Crane, that Bennett had gone absent without leave (AWOL) and arrived at the hospital by "falsely representing his condition." Patton wrote, "It is rather a commentary on justice when an Army commander has to soft-soap a skulker to placate the timidity of those above." As word of the actions had spread informally among troops of the Seventh Army, Patton drove to each division

Division or divider may refer to:

Mathematics

*Division (mathematics), the inverse of multiplication

*Division algorithm, a method for computing the result of mathematical division

Military

*Division (military), a formation typically consisting ...

under his command between August 24 and 30 and gave a 15-minute speech in which he praised their behavior and apologized for any instances where he had been too harsh on soldiers, making only vague reference to the two slapping incidents. In his final apology speech to the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division

The 3rd Infantry Division (3ID) (nicknamed Rock of the Marne) is a combined arms division of the United States Army based at Fort Stewart, Georgia. It is a direct subordinate unit of the XVIII Airborne Corps and U.S. Army Forces Command. Its cu ...

, Patton was overcome with emotion when the soldiers supportively began to chant "No, general, no, no," to prevent him from having to apologize.

In a letter to General George Marshall on August 24, Eisenhower praised Patton's exploits as commander of the Seventh Army and his conduct of the Sicily campaign, particularly his ability to take initiative as a commander. Still, Eisenhower noted Patton continued "to exhibit some of those unfortunate traits of which you and I have always known." He informed Marshall of the two incidents and his requirement that Patton apologize. Eisenhower stated he believed Patton would cease his behavior "because fundamentally, he is so avid for recognition as a great military commander that he will ruthlessly suppress any habit of his that will tend to jeopardize it." When Eisenhower arrived in Sicily to award Montgomery the Legion of Merit

The Legion of Merit (LOM) is a military award of the United States Armed Forces that is given for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services and achievements. The decoration is issued to members of the eight u ...

on August 29, Patton gave Eisenhower a letter expressing his remorse about the incidents.

Media attention

Word of the slapping incidents spread informally among soldiers before eventually circulating to war correspondents. One of the nurses who witnessed the August 10 incident apparently told her boyfriend, a captain in the Seventh Army public affairs detachment. Through him, a group of four journalists covering the Sicily operation heard of the incident: Demaree Bess of the ''Saturday Evening Post

''The Saturday Evening Post'' is an American magazine, currently published six times a year. It was issued weekly under this title from 1897 until 1963, then every two weeks until 1969. From the 1920s to the 1960s, it was one of the most widely ...

'', Merrill Mueller

Merrill Mueller (January 27, 1916 – November 30, 1980) was an American journalist whose reporting included breaking the story of Hitler's invasion of Poland. He worked for numerous news agencies including the Independent News Service and NBC. W ...

of NBC News

NBC News is the news division of the American broadcast television network NBC. The division operates under NBCUniversal Television and Streaming, a division of NBCUniversal, which is, in turn, a subsidiary of Comcast. The news division's v ...

, Al Newman of ''Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly online news magazine co-owned 50 percent each by Dev Pragad, its president and CEO, and Johnathan Davis (businessman), Johnathan Davis, who has no operational role at ''Newsweek''. Founded as a weekly print m ...

'', and John Charles Daly of CBS News

CBS News is the news division of the American television and radio service CBS. CBS News television programs include the '' CBS Evening News'', '' CBS Mornings'', news magazine programs '' CBS News Sunday Morning'', '' 60 Minutes'', and '' 4 ...

. The four journalists interviewed Etter and other witnesses, but decided to bring the matter to Eisenhower instead of filing the story with their editors. Bess, Mueller, and Quentin Reynolds

Quentin James Reynolds (April 11, 1902 – March 17, 1965) was an American journalist and World War II war correspondent. He also played American football for one season in the National Football League (NFL) with the Brooklyn Lions.

Early life ...

of ''Collier's Magazine

''Collier's'' was an American general interest magazine founded in 1888 by Peter Fenelon Collier. It was launched as ''Collier's Once a Week'', then renamed in 1895 as ''Collier's Weekly: An Illustrated Journal'', shortened in 1905 to ''Colli ...

'' flew from Sicily to Algiers, and on August 19, Bess gave a summary on the slapping incidents to Eisenhower's chief of staff

The title chief of staff (or head of staff) identifies the leader of a complex organization such as the armed forces, institution, or body of persons and it also may identify a principal staff officer (PSO), who is the coordinator of the supporti ...

, Major General Walter Bedell Smith

General Walter Bedell "Beetle" Smith (5 October 1895 – 9 August 1961) was a senior officer of the United States Army who served as General Dwight D. Eisenhower's chief of staff at Allied Forces Headquarters (AFHQ) during the Tunisia Campai ...

. The reporters asked Eisenhower directly about the incident, and Eisenhower requested that the story be suppressed because the war effort could not afford to lose Patton. Bess and other journalists initially complied. However, the news reporters then demanded Eisenhower fire Patton in exchange for them not reporting the story, a demand which Eisenhower refused.

The story of Kuhl's slapping broke in the U.S. when newspaper columnist Drew Pearson revealed it on his November 21 radio program. Pearson received details of the Kuhl incident and other material on Patton from his friend Ernest Cuneo

Ernest L. Cuneo (May 27, 1905 – March 1, 1988)

''The New York Times'', March ...

, an official with the ''The New York Times'', March ...

Office of Strategic Services

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the intelligence agency of the United States during World War II. The OSS was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines for all branc ...

, who obtained the information from War Department files and correspondence. Pearson's version not only conflated details of both slapping incidents but falsely reported that the private in question was visibly "out of his head," telling Patton to "duck down or the shells would hit him" and that in response "Patton struck the soldier, knocking him down." Pearson punctuated his broadcast by twice stating that Patton would never again be used in combat, despite the fact that Pearson had no factual basis for this prediction. In response, Allied Headquarters denied that Patton had received an official reprimand, but confirmed that Patton had slapped at least one soldier.

Patton's wife, Beatrice Patton, spoke to the media to defend him. She appeared in '' True Confessions'', a women's confession magazine Confessional Writing is a literary style and genre that developed in American writing schools following the Second World War. A prominent mode of confessional writing is confessional poetry, which emerged in the 1950s and 1960s. Confessional writin ...

, where she characterized Patton as "the toughest, most hard boiled General in the U.S. Army ... but he's quite sweet, really." She was featured in a ''Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large na ...

'' article on November 26. While she did not attempt to justify Patton's action, she characterized him as a "tough perfectionist," stating that he cared deeply about the men under his command and would not ask them to do something he would not do himself:

Public response

Demands for Patton to be relieved of duty and sent home were made in Congress and in newspapers across the country. U.S. Representative Jed Johnson of Oklahoma's 6th district described Patton's actions as a "despicable incident" and was "amazed and chagrined" Patton was still in command. He called for the general's immediate dismissal on the grounds that his actions rendered him no longer useful to the war effort. RepresentativeCharles B. Hoeven

Charles Bernard Hoeven (March 30, 1895 – November 9, 1980) was an American politician. Elected to represent districts in northern Iowa for eleven terms, from the Seventy-eighth to Eighty-eighth Congresses, in all he held elective office f ...

of Iowa's 9th district said on the House floor that parents of soldiers need no longer worry of their children being abused by "hard boiled officers." He wondered whether the Army had "too much blood and guts." Eisenhower submitted a report to Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson

Henry Lewis Stimson (September 21, 1867 – October 20, 1950) was an American statesman, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. Over his long career, he emerged as a leading figure in U.S. foreign policy by serving in both Republican and ...

, who presented it to Senator Robert R. Reynolds

Robert Rice Reynolds (June 18, 1884 – February 13, 1963) was an American politician who served as a Democratic US senator from North Carolina from 1932 to 1945. Almost from the outset of his Senate career, "Our Bob," as he was known among ...

, Chairman of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs. The report laid out Eisenhower's response to the incident and gave details of Patton's decades of military service. Eisenhower concluded that Patton was invaluable to the war effort and that he was confident the corrective actions taken would be adequate. Investigators Eisenhower sent to Patton's command found the general remained overwhelmingly popular with his troops.

By mid-December, the government had received around 1,500 letters related to Patton, with many calling for his dismissal and others defending him or calling for his promotion. Kuhl's father, Herman F. Kuhl, wrote to his own congressman, stating that he forgave Patton for the incident and requesting that he not be disciplined. Retired generals also weighed in on the matter. Former Army Chief of Staff Charles P. Summerall

General Charles Pelot Summerall (March 4, 1867 – May 14, 1955) was a senior United States Army officer. He commanded the 1st Infantry Division in World War I, was Chief of Staff of the United States Army from 1926 to 1930, and was President of ...

wrote to Patton that he was "indignant about the publicity given a trifling incident," adding that "whatever atton

Atton () is a commune in the Meurthe-et-Moselle department in northeastern France.

Population

See also

*Communes of the Meurthe-et-Moselle department

The following is a list of the 591 communes of the Meurthe-et-Moselle department of France ...

did" he was sure it was "justified by the provocation. Such cowards used to be shot, now they are only encouraged." Major General Kenyon A. Joyce, another combat commander and one of Patton's friends, attacked Pearson as a "sensation mongerer," stating that "niceties" should be left for "softer times of peace." In one notable dissension, Patton's friend, former mentor and General of the Armies

General of the Armies of the United States, more commonly referred to as General of the Armies, is the highest military rank in the United States Army. The rank has been conferred three times: to John J. Pershing in 1919, as a personal accola ...

John J. Pershing publicly condemned his actions, an act that left Patton "deeply hurt" and caused him to never speak to Pershing again.

After consulting with Marshall, Stimson, and Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy

John Jay McCloy (March 31, 1895 – March 11, 1989) was an American lawyer, diplomat, banker, and a presidential advisor. He served as Assistant Secretary of War during World War II under Henry Stimson, helping deal with issues such as German sa ...

, Eisenhower retained Patton in the European theater, though his Seventh Army saw no further combat. Patton remained in Sicily for the rest of the year. Marshall and Stimson not only supported Eisenhower's decision, but defended it. In a letter to the U.S. Senate, Stimson stated that Patton must be retained because of the need for his "aggressive, winning leadership in the bitter battles which are to come before final victory." Stimson acknowledged retaining Patton was a poor move for public relations but remained confident it was the right decision militarily.

Effect on plans for invasion of Europe

Contrary to his statements to Patton, Eisenhower never seriously considered removing the general from duty in the European Theater. Writing of the incident before the media attention, he said, "If this thing ever gets out, they'll be howling for Patton's scalp, and that will be the end of Georgie's service in this war. I simply cannot let that happen. Patton is indispensable to the war effort – one of the guarantors of our victory." Still, following the capture of Messina in August 1943, Patton did not command a force in combat for 11 months. Patton was passed over to lead the invasion in northern Europe. In September, Patton's junior in both rank and was selected to command the

Patton was passed over to lead the invasion in northern Europe. In September, Patton's junior in both rank and was selected to command the First United States Army

First Army is the oldest and longest-established field army of the United States Army. It served as a theater army, having seen service in both World War I and World War II, and supplied the US army with soldiers and equipment during the Kore ...

that was forming in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

to prepare for Operation Overlord

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 (D-Day) with the Norm ...

. According to Eisenhower, this decision had been made months before the slapping incidents became public knowledge, but Patton felt they were the reason he was denied the command. Eisenhower had already decided on Bradley because he felt the invasion of Europe was too important to risk any uncertainty. While Eisenhower and Marshall both considered Patton to be a superb corps-level combat commander, Bradley possessed two of the traits that a theater

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The perfor ...

-level strategic command required, and that Patton conspicuously lacked: a calm, reasoned demeanor, and a meticulously consistent nature. The slapping incidents had only further confirmed to Eisenhower that Patton lacked the ability to exercise discipline and self-control at such a command level. Still, Eisenhower re-emphasized his confidence in Patton's skill as a ground combat commander by recommending him for promotion to four-star general

A four-star rank is the rank of any four-star officer described by the NATO OF-9 code. Four-star officers are often the most senior commanders in the armed services, having ranks such as (full) admiral, (full) general, colonel general, army ge ...

in a private letter to Marshall on September 8, noting his previous combat exploits and admitting that he had a "driving power" that Bradley lacked.

By mid-December, Eisenhower had been appointed Supreme Allied Commander

Supreme Allied Commander is the title held by the most senior commander within certain multinational military alliances. It originated as a term used by the Allies during World War I, and is currently used only within NATO for Supreme Allied Com ...

in Europe and moved to England. As media attention surrounding the incident began to subside, McCloy told Patton he would indeed be eventually returning to combat command. Patton was briefly considered to lead the Seventh Army in Operation Dragoon

Operation Dragoon (initially Operation Anvil) was the code name for the landing operation of the Allied invasion of Provence ( Southern France) on 15August 1944. Despite initially designed to be executed in conjunction with Operation Overlord ...

, but Eisenhower felt his experience would be more useful in the Normandy campaign

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 (D-Day) with the Norm ...

. Eisenhower and Marshall privately agreed that Patton would command a follow-on field army

A field army (or numbered army or simply army) is a military formation in many armed forces, composed of two or more corps and may be subordinate to an army group. Likewise, Air army, air armies are equivalent formation within some air forces, ...

after Bradley's army conducted the initial invasion of Normandy; Bradley would then command the resulting army group

An army group is a military organization consisting of several field armies, which is self-sufficient for indefinite periods. It is usually responsible for a particular geographic area. An army group is the largest field organization handled ...

. Patton was told on January 1, 1944 only that he would be relieved of command of the Seventh Army and moved to Europe. In his diary, he wrote that he would resign if he was not given command of a field army. On January 26, 1944, formally given command of a newly arrived unit, the Third United States Army

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* 1⁄60 of a ''second'', or 1⁄3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (disambiguation)

* Third Avenue (disambiguation)

* Hig ...

, he went to the United Kingdom to prepare the unit's inexperienced soldiers for combat. This duty occupied Patton throughout early 1944.

Exploiting Patton's situation, Eisenhower sent him on several high-profile trips throughout the Mediterranean in late 1943. He traveled to Algiers, Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

, Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

, Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

, Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

, and Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

in an effort to confuse German commanders as to where the Allied forces might next attack. By the next year, the German High Command still had more respect for Patton than for any other Allied commander and considered him central to any plan to invade Europe from the north. Because of this, Patton was made a central figure in Operation Fortitude

Operation Fortitude was the code name for a World War II military deception employed by the Allied nations as part of an overall deception strategy (code named ''Bodyguard'') during the build-up to the 1944 Normandy landings. Fortitude was di ...

in early 1944. The Allies fed the German intelligence organizations, through double agents, a steady stream of false intelligence that Patton had been named commander of the First United States Army Group

First United States Army Group (often abbreviated FUSAG) was a fictitious (paper command) Allied Army Group in World War II prior to D-Day, part of Operation Quicksilver, created to deceive the Germans about where the Allies would land in Fr ...

(FUSAG) and was preparing for an invasion of Pas de Calais

The Strait of Dover or Dover Strait (french: Pas de Calais - ''Strait of Calais''), is the strait at the narrowest part of the English Channel, marking the boundary between the Channel and the North Sea, separating Great Britain from continent ...

. The FUSAG command was actually an intricately constructed "phantom" army of decoys, props and radio signals based around southeast England to mislead German aircraft and to make Axis leaders believe a large force was massing there. Patton was ordered to keep a low profile to deceive the Germans into thinking he was in Dover throughout early 1944, when he was actually training the Third Army. As a result of Operation Fortitude, the German 15th Army remained at Pas de Calais to defend against the expected attack. The formation remained there even after the invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944.

It was during the following month of July 1944 that Patton and the Third Army finally did travel to Europe, and entered into combat on August 1.

References

Notes

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Patton, George S., slapping incidents 1943 controversies 1943 in Italy 1943 in military history August 1943 events Allied invasion of SicilySlapping incident

Slap or slapping may refer to:

* Slapping (strike), a method of striking with the palm of the hand

* Slapping (music), a musical technique used with stringed instruments

* Slap tonguing, a musical technique used on wind instruments

* ''Slap'' (m ...

Post-traumatic stress disorder

United States military scandals

United States Army in World War II

Province of Enna