George E. Goodfellow on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

George Emory Goodfellow (December 23, 1855 – December 7, 1910) was a physician and naturalist in the 19th- and early 20th-century American

Goodfellow's father, Milton J. Goodfellow, came to California in 1853 to mine for gold. His mother, Amanda Baskin Goodfellow, followed two years later, arriving in San Francisco on the steamship . Goodfellow was born on December 23, 1855, in Downieville, California, then one of the largest cities in the state. His parents also had two daughters, Mary Catherine ("Kitty") and Bessie. His father became a mining engineer and maintained an interest in medicine. Goodfellow grew up around California Gold Rush mining camps and developed a deep interest in both mining and medicine. When he was 12, his parents sent him across the country to a private school in

Goodfellow's father, Milton J. Goodfellow, came to California in 1853 to mine for gold. His mother, Amanda Baskin Goodfellow, followed two years later, arriving in San Francisco on the steamship . Goodfellow was born on December 23, 1855, in Downieville, California, then one of the largest cities in the state. His parents also had two daughters, Mary Catherine ("Kitty") and Bessie. His father became a mining engineer and maintained an interest in medicine. Goodfellow grew up around California Gold Rush mining camps and developed a deep interest in both mining and medicine. When he was 12, his parents sent him across the country to a private school in

In 1880, Goodfellow decided to open his own medical practice. On September 15, he canceled his Army contract and he and his wife moved to the silver mining boomtown of Tombstone, in

In 1880, Goodfellow decided to open his own medical practice. On September 15, he canceled his Army contract and he and his wife moved to the silver mining boomtown of Tombstone, in

During the

During the

On the morning of December 8, 1883, a group of five outlaw

On the morning of December 8, 1883, a group of five outlaw

/nowiki>Luke Short and Charlie Storms /nowiki>.44 and .45

In addition to his medical practice and related studies, Goodfellow had other scientific interests. He published articles about rattlesnake and

In addition to his medical practice and related studies, Goodfellow had other scientific interests. He published articles about rattlesnake and

When the Bavispe earthquake struck the Mexican state of Sonora on May 3, 1887, it destroyed most of the adobe houses in Bavispe and killed 42 of the town's 700 residents. Goodfellow spoke excellent Spanish and he loaded his wagon with medical supplies and rode to aid survivors. The townspeople named him ''El Doctor Santo'' ("The Sainted Doctor"), and in recognition of his humanitarian contributions, Mexican President Porfirio Díaz presented him with a silver medal that had belonged to Emperor Maximilian and a horse named El Rosillo.

Goodfellow was fascinated by the earthquake and began a personal study of its effects. He noted that it was very difficult to pin down the time of the earthquake due to the absence of timepieces or a nearby railroad and the primitive living standards of the area's residents. Goodfellow returned twice more, the second time in July with Tombstone photographer C.S. Fly, to study and record the effects of the earthquake. He traveled over through the

When the Bavispe earthquake struck the Mexican state of Sonora on May 3, 1887, it destroyed most of the adobe houses in Bavispe and killed 42 of the town's 700 residents. Goodfellow spoke excellent Spanish and he loaded his wagon with medical supplies and rode to aid survivors. The townspeople named him ''El Doctor Santo'' ("The Sainted Doctor"), and in recognition of his humanitarian contributions, Mexican President Porfirio Díaz presented him with a silver medal that had belonged to Emperor Maximilian and a horse named El Rosillo.

Goodfellow was fascinated by the earthquake and began a personal study of its effects. He noted that it was very difficult to pin down the time of the earthquake due to the absence of timepieces or a nearby railroad and the primitive living standards of the area's residents. Goodfellow returned twice more, the second time in July with Tombstone photographer C.S. Fly, to study and record the effects of the earthquake. He traveled over through the

By 1890, Tombstone was on the decline. The price of silver had fallen, many of its silver mines had been permanently flooded, and a number of residents had left town. Goodfellow's wife fell ill and died in Oakland, California, at her mother-in-law's home in August 1891. Goodfellow and their daughter Edith attended her funeral at his mother's home in Oakland on August 16.

At noon on September 24, 1891, Goodfellow's good friend and colleague Dr. John C. Handy was shot on the streets of Tucson. Handy had divorced his wife and had recently been trying to evict her from the home the court had granted her. When she hired attorney

By 1890, Tombstone was on the decline. The price of silver had fallen, many of its silver mines had been permanently flooded, and a number of residents had left town. Goodfellow's wife fell ill and died in Oakland, California, at her mother-in-law's home in August 1891. Goodfellow and their daughter Edith attended her funeral at his mother's home in Oakland on August 16.

At noon on September 24, 1891, Goodfellow's good friend and colleague Dr. John C. Handy was shot on the streets of Tucson. Handy had divorced his wife and had recently been trying to evict her from the home the court had granted her. When she hired attorney

Old West

The American frontier, also known as the Old West or the Wild West, encompasses the geography, history, folklore, and culture associated with the forward wave of American expansion in mainland North America that began with European colonial ...

who developed a reputation as the United States' foremost expert in treating gunshot wounds

A gunshot wound (GSW) is a penetrating injury caused by a projectile (e.g. a bullet) from a gun (typically firearm or air gun). Damages may include bleeding, bone fractures, organ damage, wound infection, loss of the ability to move part ...

. As a medical practitioner in Tombstone, Arizona Territory, Goodfellow treated numerous bullet wounds to both lawmen and outlaws. He recorded several significant medical firsts throughout his career, including performing the first documented laparotomy

A laparotomy is a surgical procedure involving a surgical incision through the abdominal wall to gain access into the abdominal cavity. It is also known as a celiotomy.

Origins and history

The first successful laparotomy was performed without ane ...

for treating an abdominal gunshot wound and the first perineal prostatectomy

Prostatectomy (from the Greek , "prostate" and , "excision") as a medical term refers to the surgical removal of all or part of the prostate gland. This operation is done for benign conditions that cause urinary retention, as well as for pros ...

to remove an enlarged prostate

The prostate is both an accessory gland of the male reproductive system and a muscle-driven mechanical switch between urination and ejaculation. It is found only in some mammals. It differs between species anatomically, chemically, and phys ...

. He also pioneered the use of spinal anesthesia

Spinal anaesthesia (or spinal anesthesia), also called spinal block, subarachnoid block, intradural block and intrathecal block, is a form of neuraxial regional anaesthesia involving the injection of a local anaesthetic or opioid into the subara ...

and sterile techniques in treating gunshot wounds and is regarded as the first civilian trauma surgeon

Trauma surgery is a surgical specialty that utilizes both operative and non-operative management to treat traumatic injuries, typically in an acute setting. Trauma surgeons generally complete residency training in general surgery and often fel ...

.

Goodfellow was known as a pugnacious, "brilliant and versatile" physician with wide-ranging interests. He not only practiced medicine but also conducted research into the venom of Gila monster

The Gila monster (''Heloderma suspectum'', ) is a species of venomous lizard native to the Southwestern United States and the northwestern Mexican state of Sonora. It is a heavy, typically slow-moving reptile, up to long, and it is the only ve ...

s; published the first surface rupture

In seismology, surface rupture (or ground rupture, or ground displacement) is the visible offset of the ground surface when an earthquake rupture along a fault affects the Earth's surface. Surface rupture is opposed by buried rupture, where th ...

map of an earthquake in North America; interviewed Geronimo; and played a role in brokering a peace settlement in the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cloc ...

. He was a skilled boxer, and in his first year at the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy ...

he became the academy's boxing champion, though he was soon dismissed for his involvement in a hazing incident against the first African-American to attend the institution. In 1889, he got into a fight with another man and stabbed him, but was found to have acted in self-defense.

Goodfellow treated Virgil Earp

Virgil Walter Earp (July 18, 1843 – October 19, 1905) was both deputy U.S. Marshal and Tombstone, Arizona City Marshal when he led his younger brothers Wyatt and Morgan, and Doc Holliday, in a confrontation with outlaw Cowboys at the Gu ...

and Morgan Earp

Morgan Seth Earp (April 24, 1851 – March 18, 1882) was an American sheriff and Marshal, lawman. He served as Tombstone, Arizona, Tombstone, Arizona Territory, Arizona's Special Policeman when he helped his brothers Virgil Earp, Virgil and Wy ...

after they were wounded in the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral

The gunfight at the O.K. Corral was a thirty-second shootout between law enforcement officer, lawmen led by Virgil Earp and members of a loosely organized group of outlaws called the Cochise County Cowboys, Cowboys that occurred at about 3: ...

. His testimony later helped absolve the Earps and Doc Holliday of murder charges for having shot and killed three outlaw cowboys during the gunfight. He treated Virgil again when he was maimed in an ambush and rushed to Morgan's side when he was mortally wounded by an assassin. Goodfellow left Tombstone in 1889 and established a successful practice in Tucson

, "(at the) base of the black ill

, nicknames = "The Old Pueblo", "Optics Valley", "America's biggest small town"

, image_map =

, mapsize = 260px

, map_caption = Interactive map ...

before moving to San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17th ...

in 1899 and opening a medical office there. He lost his practice and all of his personal belongings in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and subsequently returned to the Southwest, where he became the chief surgeon for the Southern Pacific Railroad in Mexico. He fell ill in 1910 and died later that year in Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, largest city in the U.S. state, state of California and the List of United States cities by population, sec ...

.

Early life and education

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

. He returned to California two years later where he attended the California Military Academy in Oakland. He was then accepted to the University of California at Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant uni ...

, where he studied civil engineering

Civil engineering is a professional engineering discipline that deals with the design, construction, and maintenance of the physical and naturally built environment, including public works such as roads, bridges, canals, dams, airports, sewa ...

for one year before he applied to the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy ...

. In 1870, he was living with his family in Treasure City, Nevada, where his father was a mining superintendent.

Dismissed from Naval Academy

Goodfellow declined a congressional appointment to theUnited States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

at West Point, and instead accepted an appointment from Nevada congressional representative C.W. Kendall to attend the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy ...

, arriving there in June 1872. He became the school's resident boxing champion and was well accepted by his fellow midshipmen. Like many of his fellow cadets, he took exception to the presence of the academy's first black cadet, John H. Conyers.

While marching, Goodfellow and another cadet began kicking and punching Conyers, who had been shunned and constantly and brutally harassed since his arrival. Goodfellow later knocked Conyers down some stairs. News of the incidents and the constant hazing experienced by Conyers leaked to the newspapers, and a three-man board was convened to investigate the attacks. Goodfellow denied any wrongdoing and Conyers claimed he could not identify any of his attackers. The board nonetheless concluded, "His persecutors are left then without any excuse or palliation except the inadmissible one of prejudice." The review board believed the academy needed to give Conyers a fair chance at succeeding on his own merits, and recommended that strong measures should be taken. In December 1872, Goodfellow and two other students were dismissed from the academy.

Goodfellow immediately set about trying to get reinstated. His mother Amanda wrote a personal letter to First Lady Julia Grant

Julia Boggs Grant ( née Dent; January 26, 1826 – December 14, 1902) was the first lady of the United States and wife of President Ulysses S. Grant. As first lady, she became a national figure in her own right. Her memoirs, '' The Personal M ...

, who was known to consider blacks as inferior and whose family had owned slaves before the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

. Amanda closed her letter by reminding the first lady of their mutual friends. Goodfellow also appealed to his mother's uncle and United States Attorney Robert Baskin for assistance. Baskin interceded with his friend, President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

, who promised to reinstate Goodfellow, but the uncle left his office and Grant was busy seeking re-election. None of the efforts for reinstatement proved fruitful.

Medical education

Concerned about disappointing his father, Goodfellow sought out his cousin, Dr. T.H. Lashells, in Meadville, Pennsylvania, and read for medicine. He found he had a ready aptitude for the medical field and moved to Cleveland, Ohio, where an uncle lived. He attended Wooster University Medical School and on February 23, 1876, he graduated with honors. Goodfellow briefly opened a medical practice in Oakland. He was soon invited by his father to join him inYavapai County

Yavapai County is near the center of the U.S. state of Arizona. As of the 2020 census, its population was 236,209, making it the fourth-most populous county in Arizona. The county seat is Prescott.

Yavapai County comprises the Prescott, AZ M ...

, Arizona Territory, where Milton was a mining executive for Peck, Mine and Mill. Goodfellow worked in Prescott as the company physician for the next two years until he secured permission to serve with George Armstrong Custer

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the American Indian Wars.

Custer graduated from West Point in 1861 at the bottom of his class, b ...

's 7th Cavalry. His orders to join the unit were delayed, however, and he missed the Battle of the Little Bighorn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Nor ...

on June 25, 1876, at which most of the unit was destroyed. Instead, Goodfellow joined the U.S. Army as acting assistant surgeon at Fort Whipple in Prescott. In 1879, he became for a brief period the contract surgeon at Fort Lowell

Fort Lowell was a United States Army post active from 1873 to 1891 on the outskirts of Tucson, Arizona. Fort Lowell was the successor to Camp Lowell, an earlier Army installation.http://www.oflna.org/fort_lowell_museum/ftlowell.htm Fort Lowell, ...

near Tucson.

Family

On November 4, 1876, Goodfellow married Katherine ("Kate") Colt, daughter of Henry Tracy Colt, the proprietor of Meadville's Colt House, whom he had met while reading medicine in Meadville. Ironically, she was a cousin toSamuel Colt

Samuel Colt (; July 19, 1814 – January 10, 1862) was an American inventor, industrialist, and businessman who established Colt's Patent Fire-Arms Manufacturing Company (now Colt's Manufacturing Company) and made the mass production of ...

, inventor of the Colt revolver, a weapon that would later play a significant role in Goodfellow's medical practice. The Goodfellows left Meadville immediately after they were married, during the week of November 9, 1876, and traveled to Oakland, California

Oakland is the largest city and the county seat of Alameda County, California, United States. A major West Coast of the United States, West Coast port, Oakland is the largest city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, the third ...

.

The Goodfellows had a daughter, Edith, born on October 22, 1879, in Oakland. They also had a son, George Milton, born in May 1882 in Tombstone, Arizona Territory, who died from "general bleeding" on July 18. Kate Goodfellow died on August 16, 1891, at her mother-in-law's home in Oakland. Goodfellow and his daughter Edith caught the train to Oakland from Benson, Arizona

Benson is a city in Cochise County, Arizona, United States, east-southeast of Tucson. It was founded as a rail terminal for the area, and still serves as such. As of the 2010 census, the population of the city was 5,105.

History

The city was ...

, and when his wife died, he and Edith returned to Tombstone before he relocated to Tucson and took over the practice of his deceased friend, Dr. John C. Handy. Goodfellow married again, to Mary Elizabeth, sometime before March 1906.

Medical practice in Tombstone

In 1880, Goodfellow decided to open his own medical practice. On September 15, he canceled his Army contract and he and his wife moved to the silver mining boomtown of Tombstone, in

In 1880, Goodfellow decided to open his own medical practice. On September 15, he canceled his Army contract and he and his wife moved to the silver mining boomtown of Tombstone, in Cochise County

Cochise County () is a county in the southeastern corner of the U.S. state of Arizona. It is named after the Native American chief Cochise.

The population was 125,447 at the 2020 census. The county seat is Bisbee and the most populous city is ...

, Arizona Territory. The town was less than a year old, but its population had exploded from about 100 residents in March 1879, when it consisted mostly of wooden shacks and tents. By the fall of 1879 more than a thousand miners and merchants lived in a canvas-and-matchstick camp built on top of the richest silver strike in the United States. When Goodfellow arrived the town had a population of more than 2,000. There were already 12 doctors practicing in Tombstone, but only Goodfellow and three others had medical school diplomas.

At age 25, Goodfellow opened an office on the second floor of the Crystal Palace Saloon, one of the most luxurious saloons in the West. It was also the location of offices for other notable officials, including County Coroner Dr. H.M. Mathews, Deputy U.S. Marshal Virgil Earp

Virgil Walter Earp (July 18, 1843 – October 19, 1905) was both deputy U.S. Marshal and Tombstone, Arizona City Marshal when he led his younger brothers Wyatt and Morgan, and Doc Holliday, in a confrontation with outlaw Cowboys at the Gu ...

, attorney George W. Berry, Cochise County Sheriff Johnny Behan, and justice of the peace Wells Spicer

Wells W. Spicer (1831–1885 or 1887) was an American journalist, prospector, politician, lawyer and judge whose legal career immersed him in two significant events in frontier history: the Mountain Meadows massacre in the Utah Territory in ...

. When he was not busy tending to patients, Goodfellow walked down the outside stairs to the saloon below, where he spent many hours drinking, playing faro, and betting on horse races, foot races, wrestling and boxing matches. He reportedly got along well with all of the town's diverse social classes, from the hardscrabble miners to the wealthy elite, as well as characters like the notoriously drunk lawyer Allen English.

Goodfellow lost his office when the saloon and most of downtown Tombstone burned to the ground on May 26, 1882. The building was rebuilt and the Crystal Palace earned a reputation for its gambling, entertainment, food and the best brands of wines, liquors, and cigars. Goodfellow cared for the indigent and was reimbursed by the county at the rate of $8,000 to $12,000 per year.

Tombstone was a dangerous frontier town at the time and the scene of considerable conflict. Most of the leading cattlemen as well as numerous local outlaws, including the Cowboys

A cowboy is a professional pastoralist or mounted livestock herder, usually from the Americas or Australia.

Cowboy(s) or The Cowboy(s) may also refer to:

Film and television

* ''Cowboy'' (1958 film), starring Glenn Ford

* ''Cowboy'' (1966 film), ...

, were Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

sympathizers and Democrats from Southern states, especially Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

and Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

. The mine and business owners, miners, city lawmen including brothers Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: th ...

, Morgan, and Wyatt Earp

Wyatt Berry Stapp Earp (March 19, 1848 – January 13, 1929) was an American lawman and gambler in the American West, including Dodge City, Deadwood, and Tombstone. Earp took part in the famous gunfight at the O.K. Corral, during which l ...

, and most of the other townspeople were largely Republicans from the Northern states. There was also the fundamental conflict over resources and land, of traditional, Southern-style, “small government

Libertarian conservatism, also referred to as conservative libertarianism and conservatarianism, is a political and social philosophy that combines conservatism and libertarianism, representing the libertarian wing of conservatism and vice ver ...

” agrarianism of the rural Cowboys contrasted to Northern-style industrial

Industrial may refer to:

Industry

* Industrial archaeology, the study of the history of the industry

* Industrial engineering, engineering dealing with the optimization of complex industrial processes or systems

* Industrial city, a city dominate ...

capitalism. The ''Tombstone Daily Journal'' asked in March 1881 how a hundred outlaws could terrorize the best system of government in the world, asking, "Can not the marshal summon a posse and throw the ruffians out?" Goodfellow later famously described Tombstone as the "condensation of wickedness."

Treatment of O.K. Corral lawmen

During the

During the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral

The gunfight at the O.K. Corral was a thirty-second shootout between law enforcement officer, lawmen led by Virgil Earp and members of a loosely organized group of outlaws called the Cochise County Cowboys, Cowboys that occurred at about 3: ...

on October 26, 1881, Deputy U.S. Marshal Virgil Earp

Virgil Walter Earp (July 18, 1843 – October 19, 1905) was both deputy U.S. Marshal and Tombstone, Arizona City Marshal when he led his younger brothers Wyatt and Morgan, and Doc Holliday, in a confrontation with outlaw Cowboys at the Gu ...

was shot through the calf and Assistant Deputy U.S. Marshal Morgan Earp

Morgan Seth Earp (April 24, 1851 – March 18, 1882) was an American sheriff and Marshal, lawman. He served as Tombstone, Arizona, Tombstone, Arizona Territory, Arizona's Special Policeman when he helped his brothers Virgil Earp, Virgil and Wy ...

was shot across both shoulder blades. Doc Holliday was grazed by a bullet. Goodfellow treated both Earps' wounds. Cowboy Billy Clanton

William Harrison Clanton (1862 – October 26, 1881) was an outlaw Cowboy in Cochise County, Arizona Territory. He, along with his father Newman Clanton and brother Ike Clanton, worked a ranch near the boomtown of Tombstone, Arizona Territor ...

, who had been mortally wounded in the shootout, asked someone to remove his boots before he died; Goodfellow was present and obliged.

After the gunfight, Ike Clanton filed murder charges against the Earps and Doc Holliday. Goodfellow reviewed Dr. H.M. Mathew's autopsy reports on the three outlaw cowboys the Earps and Holiday had killed: Billy Clanton and brothers Tom and Frank McLaury. Goodfellow's testimony about the nature of Billy Clanton's wounds during the hearing supported the defendants' version of events, that Billy's arm could not have been positioned holding his coats open by the lapels or raised in the air, as witnesses loyal to the Cowboys testified. Goodfellow's testimony was helpful in exonerating the Earps and the judge ruled that the lawmen had acted in self-defense.

Goodfellow treated Virgil Earp again two months later, on December 28, 1881, after he was ambushed. At about 11:30 pm that night, three men hid in an unfinished building across Allen Street from the Cosmopolitan Hotel where the Earps were staying. They shot Virgil as he walked from the Oriental Saloon to his room, hitting him in the back and left arm with three loads of double-barreled buckshot from about . Goodfellow advised Virgil that the arm ought to be amputated, but Virgil refused. Goodfellow operated on Virgil in the Cosmopolitan Hotel using the medical tools he had in his bag, and asked George Parsons and another fellow to fetch some supplies from the hospital. Virgil had a longitudinal fracture of the humerus and elbow that could not be repaired, requiring Goodfellow to remove more than of shattered humerus bone from Virgil's left arm, leaving him permanently crippled.

The next victim of the feud was Morgan Earp

Morgan Seth Earp (April 24, 1851 – March 18, 1882) was an American sheriff and Marshal, lawman. He served as Tombstone, Arizona, Tombstone, Arizona Territory, Arizona's Special Policeman when he helped his brothers Virgil Earp, Virgil and Wy ...

. At 10:50 pm on March 18, 1882, Morgan was playing a round of billiards

Cue sports are a wide variety of games of skill played with a cue, which is used to strike billiard balls and thereby cause them to move around a cloth-covered table bounded by elastic bumpers known as .

There are three major subdivisions ...

at the Campbell & Hatch Billiard Parlor against owner Bob Hatch. Dan Tipton, Sherman McMaster, and Wyatt Earp watched, having also received death threats that same day. An unknown assailant shot Morgan through a glass-windowed, locked door that opened onto a dark alley between Allen and Fremont Streets. Morgan was struck in the back on the left of his spine and the bullet exited the front of his body near his gall bladder before lodging in the thigh of mining foreman George A.B. Berry. Morgan was mortally wounded and could not stand even with assistance. They laid him on a nearby lounge where he died within the hour. Drs. Matthews, Millar, and Goodfellow all examined Morgan. Even Goodfellow, recognized in the United States as the nation's leading expert at treating abdominal gunshot wounds, concluded that Morgan's wounds were fatal.

As County Coroner, Goodfellow conducted Morgan Earp's autopsy. He found the bullet "entering the body just to the left of the spinal column in the region of the left kidney emerging on the right side of the body in the region of the gall bladder. It certainly injured the great vessels of the body causing hemorrhage which undoubtedly causes death. It also injured the spinal column. It passed through the left kidney and also through the loin.” Berry recovered from his wound.

Treatment of cowboys

Goodfellow treated outlaws as well as lawmen, including a number of the notoriousCochise County Cowboys

The Cochise County Cowboys is the modern name for a loosely associated group of outlaws living in Pima and Cochise County, Arizona in the late 19th century. The term "''cowboy''", as opposed to "'' cowhand''," had only begun to come into wider ...

active in the Tombstone area during the 1880s. On May 26, 1881, the ''Arizona Daily Star'' reported that Curly Bill Brocius

William Brocius (c. 1845 – March 24, 1882), better known as Curly Bill Brocius, was an American gunman, rustler and an outlaw Cowboy in the Cochise County area of the Arizona Territory during the late 1870s and early 1880s. His name is like ...

was drunk when he got into an argument with Lincoln County War veteran Jim Wallace, who had insulted Brocius' friend and ally, Tombstone Deputy Marshal Billy Breakenridge. Brocius took offense and even though Wallace apologized, Brocius threatened to kill him. When Wallace left, Curly Bill followed him and Wallace shot him though the cheek and neck. Goodfellow treated Brocius, who recovered after several weeks. Marshal Breakenridge arrested Wallace but the court ruled he had acted in self-defense.

Goodfellow was noted for his wry humor. Once, a gambler named McIntire was shot and killed during an argument over a card game; Goodfellow performed an autopsy on the man and wrote in his report that he had done "the necessary assessment work and found the body full of lead, but too badly punctured to hold whiskey."

County Coroner

On the morning of December 8, 1883, a group of five outlaw

On the morning of December 8, 1883, a group of five outlaw Cowboys

A cowboy is a professional pastoralist or mounted livestock herder, usually from the Americas or Australia.

Cowboy(s) or The Cowboy(s) may also refer to:

Film and television

* ''Cowboy'' (1958 film), starring Glenn Ford

* ''Cowboy'' (1966 film), ...

robbed the Goldwater & Castaneda Mercantile in Bisbee, Arizona

Bisbee is a city in and the county seat of Cochise County in southeastern Arizona, United States. It is southeast of Tucson and north of the Mexican border. According to the 2020 census, the population of the town was 4,923, down from 5,575 ...

, which was rumored to be holding the $7,000 payroll for the Copper Queen Mine

The Copper Queen Mine was a copper mine in Cochise County, Arizona, United States. Its development led to the growth of the surrounding town of Bisbee in the 1880s. Its orebody ran 23% copper, an extraordinarily high grade. It was acquired by Ph ...

. But the payroll had not yet arrived, and the outlaws decided to steal whatever they could take from the safe and the employees and customers. They stole between $900 and $3,000 along with a gold watch and jewelry. In what became known as the Bisbee massacre, some of the robbers waiting outside began shooting passersby, killing four people, including a pregnant woman and her unborn child. John Heath (sometimes spelled Heith) had been a cattle rustler

Cattle raiding is the act of stealing cattle. In Australia, such stealing is often referred to as duffing, and the perpetrator as a duffer.Baker, Sidney John (1945) ''The Australian language : an examination of the English language and English ...

in Texas, but since arriving in Arizona he had served briefly as a Cochise County

Cochise County () is a county in the southeastern corner of the U.S. state of Arizona. It is named after the Native American chief Cochise.

The population was 125,447 at the 2020 census. The county seat is Bisbee and the most populous city is ...

deputy sheriff and had also opened a saloon. When the five bandits were caught, they quickly implicated Heath as the man who had planned the hold-up. He was arrested and tried separately from the other five, who were convicted of first-degree murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification or valid excuse, especially the unlawful killing of another human with malice aforethought. ("The killing of another person without justification or excuse, especially the ...

and sentenced to hang.

Heath was convicted of second-degree murder and conspiracy to commit robbery, and the judge could reluctantly sentence him only to a life term at the Yuma Territorial Prison

The Yuma Territorial Prison is a former prison located in Yuma, Arizona, United States. Opened on July 1, 1876, and shut down on September 15, 1909. It is one of the Yuma Crossing and Associated Sites on the National Register of Historic Places ...

. The citizens of Tombstone were outraged and broke into the jail, forcibly removing Heath and stringing him up from a nearby telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

pole. Heath's last words were: "I have faced death too many times to be disturbed when it actually comes. ... Dont mutilate my body or shoot me full of holes!" Goodfellow, who was present at Heath's hanging, was County Coroner and responsible for determining the exact cause of death. His wry conclusion reflected the popular sentiment of the town. He ruled that Heath died from “...emphysema of the lungs which might have been, and probably was, caused by strangulation, self-inflicted or otherwise, as in accordance with the medical evidence.”

Authority on gunshot wounds

Goodfellow is today remembered for having pioneered the practical use of sterile techniques in treating gunshot wounds by washing the patient's wound and his hands with lye soap or whisky. He simultaneously became America's leading authority on gunshot wounds and was widely recognized for his skill as a surgeon. On July 2, 1881, President James Garfield was shot by assassin Charles J. Guiteau. One bullet was thought later to have possibly lodged near his liver but could not be found. Standard medical practice at the time called for physicians to insert their unsterilized fingers into the wound to probe and locate the path of the bullet. Neither the germ theory nor Dr.Joseph Lister

Joseph Lister, 1st Baron Lister, (5 April 182710 February 1912) was a British surgeon, medical scientist, experimental pathologist and a pioneer of antiseptic surgery and preventative medicine. Joseph Lister revolutionised the craft of ...

's technique for "antisepsis surgery" using dilute carbolic acid

Phenol (also called carbolic acid) is an aromaticity, aromatic organic compound with the molecular chemical formula, formula . It is a white crystalline solid that is volatility (chemistry), volatile. The molecule consists of a phenyl group () ...

, which had been first demonstrated in 1865, much less surgically opening abdominal cavities to repair gunshot wounds

A gunshot wound (GSW) is a penetrating injury caused by a projectile (e.g. a bullet) from a gun (typically firearm or air gun). Damages may include bleeding, bone fractures, organ damage, wound infection, loss of the ability to move part ...

, had yet been accepted as standard practice by prevailing medical authorities. Sixteen doctors attended to Garfield and most probed the wound with their fingers or dirty instruments. Historians agree that massive infection was a significant factor in President Garfield's death two months later.

On July 4, two days after the President was shot, a miner outside Tombstone was shot in the abdomen with a .32-caliber Colt revolver. Goodfellow was able to treat the man nine days later, on July 13, 1881, when he performed the first laparotomy

A laparotomy is a surgical procedure involving a surgical incision through the abdominal wall to gain access into the abdominal cavity. It is also known as a celiotomy.

Origins and history

The first successful laparotomy was performed without ane ...

to treat a bullet wound. Goodfellow noted that the abdomen showed symptoms of a serious infection, including distension from gas, tumefaction, redness and tenderness. The man's intestines were covered with a large amount of "purulent stinking lymph." The patient's small and large intestine

The large intestine, also known as the large bowel, is the last part of the gastrointestinal tract and of the digestive system in tetrapods. Water is absorbed here and the remaining waste material is stored in the rectum as feces before bein ...

were perforated by six holes, wounds very similar to President Garfield's injury. Goodfellow followed Lister's recommended procedure for sterilizing everything: his hands, instruments, sponges, and the area around the wound. He successfully repaired the miner's wounds and the miner, unlike the President, survived. A laparotomy is still the standard procedure for treating abdominal gunshot wounds today.

Goodfellow often traveled many hours to treat cowboys miles from Tombstone and performed surgery under primitive conditions. He traveled to Bisbee, from Tombstone, in January 1889 to treat a patient struck in the abdomen by a bullet from a .44 Colt. At midnight, he operated on the patient stretched out on a billiards table. Goodfellow removed a .45-caliber bullet, washed out the cavity with two gallons of hot water, folded the intestines back into position, stitched the wound closed with silk thread, and ordered the patient to take to a hard bed for recovery. He wrote about the operation: "I was entirely alone having no skilled assistant of any sort, therefore was compelled to depend for aid upon willing friends who were present—these consisting mostly of hard-handed miners just from their work on account of the fight. The anesthetic was administered by a barber, lamps held, hot water brought and other assistance rendered by others." The man lived for 18 hours after surgery, long enough to write out his will, but died of shock.

Thesis on abdominal wounds

Goodfellow was the first physician known to operate successfully on abdominal gunshot wounds, which had been previously considered an all-but-certain death sentence. During his career, he published 13 articles about abdominal bullet wounds based on treatments and techniques he developed while practicing medicine in Tombstone. His articles were laced with colorful commentary describing his medical practice in the primitive west. He wrote, "In the spring of 1881 I was a few feet distant from a couple of individualsWinchester rifle

Winchester rifle is a comprehensive term describing a series of lever action repeating rifles manufactured by the Winchester Repeating Arms Company. Developed from the 1860 Henry rifle, Winchester rifles were among the earliest repeaters. The Mo ...

s and carbines were the toys with which our festive or obstreperous citizens delight themselves." The .45-caliber Colt Peacemaker

The Colt Single Action Army (also known as the SAA, Model P, Peacemaker, or M1873) is a single-action revolver handgun. It was designed in 1872 for the U.S. government service revolver trials of 1872 by Colt's Patent Firearms Manufacturing Co ...

round contained 40 grains of black powder that shot a thumb-sized, 250- grain slug at the relatively slow velocity of 910 feet per second. But the large bullet could smash through a pine board at . Goodfellow saw the effect of these large-caliber weapons up close and was very familiar with their powerful impact. In an article titled "Cases of Gunshot Wound of the Abdomen Treated by Operation" in the ''Southern California Practitioner'' of 1889 he wrote, "the maxim is, shoot for the guts; knowing death is certain, yet sufficiently lingering and agonizing to afford a plenary sense of gratification to the victor in the contest." His article described five patients with penetrating abdominal wounds, four of whom survived, and the laparotomies he completed on all of them. He wrote, "it is inexcusable and criminal to neglect to operate upon a case of gunshot wound in the abdominal cavity."

Goodfellow learned that the caliber of the bullet determined whether a medical procedure was needed. If the bullet was .32-caliber or larger, it "inflicted enough damage to necessitate immediate operation." He noted, "Given a gunshot wound of the abdominal cavity with one of the above caliber balls hemorrhage

Bleeding, hemorrhage, haemorrhage or blood loss, is blood escaping from the circulatory system from damaged blood vessels. Bleeding can occur internally, or externally either through a natural opening such as the mouth, nose, ear, urethra, v ...

is beyond any chance of recovery.” W.W. Whitmore wrote in an October 9, 1932, article in the '' Arizona Daily Star'' that Goodfellow "presumably had a greater practice in gunshot wounds of the abdomen than any other man in civil life in the country."

Conceived of bulletproof fabrics

On February 25, 1881, faro dealerLuke Short

Luke Lamar Short (January22, 1854September8, 1893) was an American Old West gunfighter, cowboy, U.S. Army scout, dispatch rider, gambler, boxing promoter, and saloon owner. He survived numerous gunfights, the most famous of which were agains ...

and professional gambler and gunfighter Charlie Storms Charles Spencer Storms, known as Charlie Storms (1823–1881) was a professional gunfighter and gambler of the Old West, who is best known for having been killed in a gunfight with Luke Short in Tombstone, Arizona.

Early life

Charlie Storms ...

got into an argument in Tombstone. Storms had successfully defended himself several times with his pistol, but had inaccurately sized Short up as someone he could "slap in the face without expecting a return." Bat Masterson

Bartholemew William Barclay "Bat" Masterson (November 26, 1853 – October 25, 1921) was a U.S. Army scout, lawman, professional gambler, and journalist known for his exploits in the 19th and early 20th-century American Old West. He was born to ...

initially defused a confrontation between the two men, but Storms returned, yanked Short off the sidewalk, and pulled his cut-off Colt .45 pistol. Luke Short was quicker and pulled his own pistol, shooting Charlie Storms twice before he hit the ground. The first shot was from such close range it reportedly set fire to Storms' shirt. Short's actions were ruled self-defense.

In an autopsy of Storms' body, Goodfellow found that he had been shot in the heart but was surprised to see "not a drop of blood" exiting the wound, and noted that the bullet that struck Storms would ordinarily have passed through the body. He discovered that the bullet had ripped through the man's clothes and into a folded silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from the ...

handkerchief in his breast pocket. He extracted the intact bullet from the wound and found two thicknesses of silk wrapped around it and two tears where it had struck the vertebral column. Goodfellow showed the slightly flattened .45-caliber bullet and bloody handkerchief to George Parsons.

Another case that attracted his attention was an incident when Assistant City Marshal Billy Breakenridge shot Billy Grounds from with a shotgun, killing him. Goodfellow examined Billy and found that two buckshot

A shotgun shell, shotshell or simply shell is a type of rimmed, cylindrical (straight-walled) cartridges used specifically in shotguns, and is typically loaded with numerous small, pellet-like spherical sub-projectiles called shot, fired thro ...

grains had penetrated Billy's thick Mexican felt hat band, which was embroidered with silver wire. These two buckshot and two others penetrated his head and flattened against the posterior wall of the skull, and others penetrated the face and chest. He also noted that one of the grains had passed through two heavy wool shirts and a blanket-lined canvas coat and vest before coming to rest deep in his chest. But Goodfellow was fascinated to find, in the folds of a Chinese silk handkerchief around Grounds' neck, two shotgun pellets but no holes. The ''Tombstone Epitaph

''The Tombstone Epitaph'' is a Tombstone, Arizona, monthly publication that covers the history and culture of the Old West. Founded in January 1880 (with its first issue published on Saturday May 1, 1880), it is the oldest continually published ...

'' reported, "A silken armor may be the next invention."

In a third instance, he described a man who had been shot through the right side of the neck, narrowly missing his carotid artery. A portion of the man's silk neckerchief had been carried into the wound by the bullet, preventing a more serious injury, but the scarf was undamaged. To Goodfellow, the remarkable protection offered by the silk was plainly evident from these examples, with the second case of the buckshot perhaps best illustrating the protection afforded by silk. In 1887, Goodfellow documented these cases in an article titled "Notes on the Impenetrability of Silk to Bullets" for the ''Southern California Practitioner''. He experimented with designs for bullet-resistant clothing made of multiple layers of silk. By 1900, gangsters were wearing $800 silk vests to protect themselves. In 2018, the US military began conducting research into the feasibility of using artificial silk as body armor.

Other medical firsts

Goodfellow was an innovative physician who was forced to experiment with differing methods than those utilized by physicians in more civilized eastern practices. He pioneered the idea of treatingtuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, i ...

patients by exposing them to Arizona's dry climate. Along with performing the first laparotomy, Goodfellow recorded several other surgical firsts, including performing the first appendectomy in the Arizona Territory. During 1891 at St. Mary's Hospital in Tucson, he performed what many consider to be the first perineal prostatectomy

Prostatectomy (from the Greek , "prostate" and , "excision") as a medical term refers to the surgical removal of all or part of the prostate gland. This operation is done for benign conditions that cause urinary retention, as well as for pros ...

, an operation he developed to treat bladder problems by removing the enlarged prostate

The prostate is both an accessory gland of the male reproductive system and a muscle-driven mechanical switch between urination and ejaculation. It is found only in some mammals. It differs between species anatomically, chemically, and phys ...

. He traveled extensively across the United States over the next decade, training other physicians to perform the procedure. Among these was Dr. Hugh Young, a well-known and respected urology

Urology (from Greek οὖρον ''ouron'' "urine" and '' -logia'' "study of"), also known as genitourinary surgery, is the branch of medicine that focuses on surgical and medical diseases of the urinary-tract system and the reproductive org ...

professor at Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hemisphere. It consi ...

. Goodfellow completed 78 operations and only two patients died, a remarkable level of success for the time period. He was among the first surgeons anywhere, let alone on the frontier of the United States, to implement the use of spinal anesthesia, which he improvised by crushing cocaine

Cocaine (from , from , ultimately from Quechua: ''kúka'') is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant mainly used recreationally for its euphoric effects. It is primarily obtained from the leaves of two Coca species native to South Ameri ...

crystals in spinal fluid and re-injecting the mixture into the patient's spine.

Other scientific pursuits

In addition to his medical practice and related studies, Goodfellow had other scientific interests. He published articles about rattlesnake and

In addition to his medical practice and related studies, Goodfellow had other scientific interests. He published articles about rattlesnake and Gila monster

The Gila monster (''Heloderma suspectum'', ) is a species of venomous lizard native to the Southwestern United States and the northwestern Mexican state of Sonora. It is a heavy, typically slow-moving reptile, up to long, and it is the only ve ...

bites in the ''Scientific American

''Scientific American'', informally abbreviated ''SciAm'' or sometimes ''SA'', is an American popular science magazine. Many famous scientists, including Albert Einstein and Nikola Tesla, have contributed articles to it. In print since 1845, it ...

'' and the ''Southern California Practitioner''. He was among the first to research the actual effects of Gila monster venom when the lizard was widely feared for its deadly bite. The ''Scientific American'' reported in 1890 that "The breath is very fetid, and its odor can be detected at some little distance from the lizard. It is supposed that this is one way in which the monster catches the insects and small animals which form a part of its food supply—the foul gas overcoming them." Goodfellow offered to pay local residents $5.00 for Gila monster specimens. He bought several and collected more on his own. In 1891, he purposefully provoked one of his captive lizards into biting him on his finger. The bite made him ill and he spent the next five days in bed, but he completely recovered. When ''Scientific American'' ran another ill-founded report on the lizard's ability to kill people, he wrote in reply and described his own studies and personal experience. He wrote that he knew several people who had been bitten by Gila monsters but had not died from the bite, suggesting that the bite was not necessarily fatal, as was commonly believed at the time.

1887 Sonora earthquake

When the Bavispe earthquake struck the Mexican state of Sonora on May 3, 1887, it destroyed most of the adobe houses in Bavispe and killed 42 of the town's 700 residents. Goodfellow spoke excellent Spanish and he loaded his wagon with medical supplies and rode to aid survivors. The townspeople named him ''El Doctor Santo'' ("The Sainted Doctor"), and in recognition of his humanitarian contributions, Mexican President Porfirio Díaz presented him with a silver medal that had belonged to Emperor Maximilian and a horse named El Rosillo.

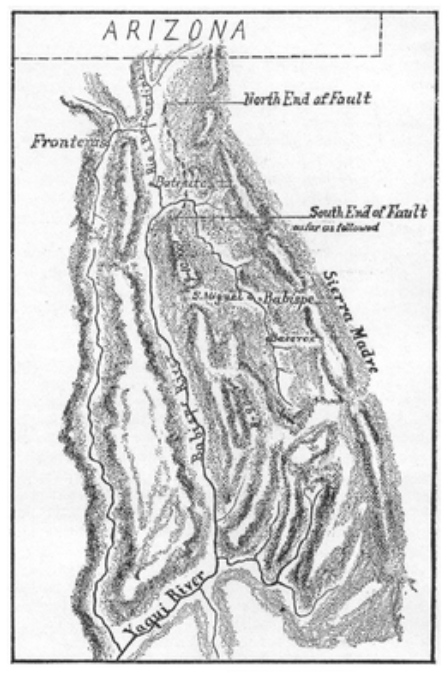

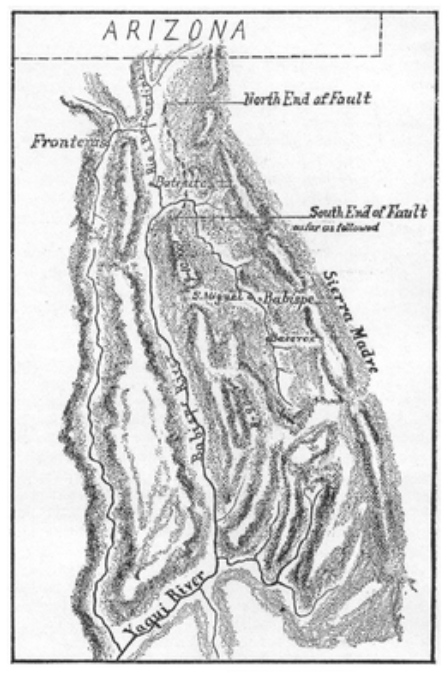

Goodfellow was fascinated by the earthquake and began a personal study of its effects. He noted that it was very difficult to pin down the time of the earthquake due to the absence of timepieces or a nearby railroad and the primitive living standards of the area's residents. Goodfellow returned twice more, the second time in July with Tombstone photographer C.S. Fly, to study and record the effects of the earthquake. He traveled over through the

When the Bavispe earthquake struck the Mexican state of Sonora on May 3, 1887, it destroyed most of the adobe houses in Bavispe and killed 42 of the town's 700 residents. Goodfellow spoke excellent Spanish and he loaded his wagon with medical supplies and rode to aid survivors. The townspeople named him ''El Doctor Santo'' ("The Sainted Doctor"), and in recognition of his humanitarian contributions, Mexican President Porfirio Díaz presented him with a silver medal that had belonged to Emperor Maximilian and a horse named El Rosillo.

Goodfellow was fascinated by the earthquake and began a personal study of its effects. He noted that it was very difficult to pin down the time of the earthquake due to the absence of timepieces or a nearby railroad and the primitive living standards of the area's residents. Goodfellow returned twice more, the second time in July with Tombstone photographer C.S. Fly, to study and record the effects of the earthquake. He traveled over through the Sierra Madre

Sierra Madre (Spanish, 'mother mountain range') may refer to:

Places and mountains Mexico

*Sierra Madre Occidental, a mountain range in northwestern Mexico and southern Arizona

*Sierra Madre Oriental, a mountain range in northeastern Mexico

*S ...

mountains recording his observations, mostly on foot. The United States Geological Service praised his "remarkable and creditable" report, describing it as "systematic, conscientious, and thorough."

On August 12, 1887, he wrote a letter following up on his initial report in the top U.S. scientific journal, ''Science''. It included the first surface rupture map of an earthquake in North America and photographs of the rupture scarp by C.S. Fly. The earthquake was at the time the “longest recorded normal-fault surface rupture in historic time.” It was later described as an “outstanding study” and a “pioneering achievement”. Goodfellow simultaneously developed a friendship with Mexican politician Ramón Corral and hosted him in 1904 when he visited San Francisco.

Personal reputation

Along with being an extremely talented and innovative surgeon, Goodfellow developed a reputation as a hard-drinking, irascible ladies-man. He kept company with some of thecourtesans

Courtesan, in modern usage, is a euphemism for a "kept" mistress or prostitute, particularly one with wealthy, powerful, or influential clients. The term historically referred to a courtier, a person who attended the court of a monarch or oth ...

who frequented the Crystal Palace Saloon. He was also known to be a vocal supporter of the Earps, town business owners, and miners, but that did not keep the rural Cowboys from seeking his services during the 11 years his office was located in Tombstone. He delivered babies, set miners' broken bones, treated gunshot wounds to cowboys and lawmen alike, and provided medical care to anyone in need. Tombstone had a large number of silver mines during its peak production period, and Goodfellow entered smoke-filled mining shafts on more than one occasion to help treat trapped and injured miners. The ''Tombstone Epitaph'' said Goodfellow had "both skill and nerve, both of which were brought into requisition on Contention Hill" when he personally rescued unconscious miners in late May 1886.

While Goodfellow lived in Tombstone, he was a founder in 1880 of the plush Tombstone Club located on the second floor of the Ritchie Building. The rooms were furnished with reading tables and chairs. The 60 male members had access to more than 70 publications. Goodfellow also helped organize the Tombstone Scientific Society. He was active in other community affairs, and invested in the Huachuca Water Company, which in 1881 built a pipeline from the Huachuca Mountains

The Huachuca Mountains are part of the Sierra Vista Ranger District of the Coronado National Forest in Cochise County in southeastern Arizona, approximately south-southeast of Tucson and southwest of the city of Sierra Vista. Included in this a ...

to Tombstone, along with a community swimming pool.

During the Tombstone fire in June 1881, George W. Parsons was helping to tear down a balcony to prevent the fire from spreading when he was struck by the falling wood. Parsons' upper lip and nose were pierced by a splinter of wood, severely flattening and deforming his nose. Goodfellow devised a wire framework and in a series of treatments successfully restored Parsons' nose to his pre-injury profile. He refused payment because Parsons had been hurt as he was assisting others.

Goodfellow was not a man to be taken lightly. In August 1889, he got into a fight while drunk during which he stabbed Frank White with a triple-edged, poignard

A poniard or ''poignard'' ( Fr.) is a long, lightweight thrusting knife with a continuously tapering, acutely pointed blade, and a cross-guard, historically worn by the upper class, noblemen, or members of the knighthood. Similar in design to a ...

. White was seriously injured but Goodfellow was not arrested, as the judge ruled Goodfellow had acted in self-defense.

Later life

In 1884, Goodfellow's father was a mining engineer in nearbyFairbank, Arizona

Fairbank is a ghost town in Cochise County, Arizona, next to the San Pedro River. First settled in 1881, Fairbank was the closest rail stop to nearby Tombstone, which made it an important location in the development of southeastern Arizona. The ...

, on the railroad line from Tucson to Nogales. His father died in 1887 in San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United State ...

. In 1886, Goodfellow reportedly rode with the U.S. Army while they were attempting to recapture Geronimo after he left the San Carlos Reservation

The San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation ( Western Apache: Tsékʼáádn), in southeastern Arizona, United States, was established in 1872 as a reservation for the Chiricahua Apache tribe as well as surrounding Yavapai and Apache bands removed f ...

against Army orders. During his escape, he and his warriors killed "fourteen Americans dead in the United States and between 500 and 600 Mexicans dead south of the border." After Geronimo was apprehended, Goodfellow, who spoke fluent Spanish and some Apache, befriended Geronimo.

Move to Tucson

By 1890, Tombstone was on the decline. The price of silver had fallen, many of its silver mines had been permanently flooded, and a number of residents had left town. Goodfellow's wife fell ill and died in Oakland, California, at her mother-in-law's home in August 1891. Goodfellow and their daughter Edith attended her funeral at his mother's home in Oakland on August 16.

At noon on September 24, 1891, Goodfellow's good friend and colleague Dr. John C. Handy was shot on the streets of Tucson. Handy had divorced his wife and had recently been trying to evict her from the home the court had granted her. When she hired attorney

By 1890, Tombstone was on the decline. The price of silver had fallen, many of its silver mines had been permanently flooded, and a number of residents had left town. Goodfellow's wife fell ill and died in Oakland, California, at her mother-in-law's home in August 1891. Goodfellow and their daughter Edith attended her funeral at his mother's home in Oakland on August 16.

At noon on September 24, 1891, Goodfellow's good friend and colleague Dr. John C. Handy was shot on the streets of Tucson. Handy had divorced his wife and had recently been trying to evict her from the home the court had granted her. When she hired attorney Francis J. Heney

Francis Joseph "Frank" Heney (March 17, 1859 – October 31, 1937) was an American lawyer, judge, and politician. Heney is known for killing an opposing plaintiff in self-defense and for being shot in the head by a prospective juror during the Sa ...

, Handy repeatedly threatened to kill him. He assaulted the attorney on the street that afternoon and Heney shot him in self-defense. Hearing the news, Goodfellow rode by horseback to Benson, Arizona

Benson is a city in Cochise County, Arizona, United States, east-southeast of Tucson. It was founded as a rail terminal for the area, and still serves as such. As of the 2010 census, the population of the city was 5,105.

History

The city was ...

, where he caught a locomotive and caboose, set aside just for him, to Tucson. In an effort to save Handy, he apparently took over the engine from the engineer and drove the train at high speed, covering the in record time. Handy had been attended by Drs. Michael Spencer, John Trail Green, and Hiram W. Fenner until Goodfellow arrived in Tucson at 8:15 PM. He began operating on Handy at about 10:00 PM. He found 18 perforations in Handy's intestines, which he immediately set about cleaning and closing. Goodfellow was too late, however, and Handy died at 1:15 AM, before Goodfellow could complete the surgery.

After Handy's death, Dr. Goodfellow was invited to take over his Tucson practice, and he and his daughter Edith relocated there. He purchased the old Orndorff Hotel located near present-day City Hall and used it as a hospital. He also practiced at St. Mary's Hospital. In 1891, he operated on the chief surgeon of the Southern Pacific Railroad, who, like Handy, had been shot by his estranged wife's attorney. The surgeon died, and Goodfellow soon after accepted the railroad job, serving from 1891 to 1896. He was appointed by Governor Louis C. Hughes in 1893 as the Arizona Territorial Health Officer, a position he held until 1896. He was living in Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, largest city in the U.S. state, state of California and the List of United States cities by population, sec ...

in 1896 and was listed in the 1897 Los Angeles City Directory.

Further military service

Goodfellow returned to Tucson in 1898 and later that year he became the personal physician to his friend General William "Pecos Bill" Shafter during theSpanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cloc ...

. Appointed as a major, he was in charge of the general's field hospital

A field hospital is a temporary hospital or mobile medical unit that takes care of casualties on-site before they can be safely transported to more permanent facilities. This term was initially used in military medicine (such as the Mobile A ...

.

Shafter relied on Goodfellow's excellent knowledge of the Spanish language to help negotiate the final surrender after the Battle of San Juan Hill

The Battle of San Juan Hill, also known as the Battle for the San Juan Heights, was a major battle of the Spanish–American War fought between an American force under the command of William Rufus Shafter and Joseph Wheeler against a Spanish fo ...

. Goodfellow attributed part of his success to a bottle of “ol’ barleycorn” he kept handy in his medical kit, which he properly prescribed to himself and Spanish General José Toral, lending a more convivial atmosphere to the conference. Goodfellow was recognized with a commendation for his service that cited his "especially meritorious services professional and military".

Practice in San Francisco

In late 1899, Goodfellow moved toSan Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17th ...

and established his practice at 771 Sutter St. On January 19, 1900, he was appointed as the surgeon for the Santa Fe Railroad

The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway , often referred to as the Santa Fe or AT&SF, was one of the larger railroads in the United States. The railroad was chartered in February 1859 to serve the cities of Atchison and Topeka, Kansas, and ...

headquartered in San Francisco. He was an active member of the Bohemian Club and attended their summer camp on the Russian River regularly. On February 15, 1900, Wells Fargo Express Agent Jeff Milton, a friend of Goodfellow, arrived on board a train in Fairbank, near Benson, Arizona. Former lawman-turned-outlaw Burt Alvord

Albert "Burt" Alvord (September 11, 1867 – after 1910) was an American lawman and later outlaw of the Old West. Alvord began his career in law enforcement in 1886 as a deputy under Sheriff John Slaughter in Cochise County, Arizona, but turne ...

and five other robbers attempted to rob an arriving train of its cash. Milton was seriously wounded in the left arm and the railroad dispatched a special engine and boxcar to transport Milton from Benson to Tucson for treatment. In Tucson, Dr. H.W. Fenner tied the shattered bone together with piano wire. When the wound failed to heal, he sent Milton to San Francisco, where he could be seen by experts at the Southern Pacific Hospital there. They wanted to amputate his arm at the elbow, but he refused and got a ride to Dr. Goodfellow's office. Goodfellow successfully cleaned and treated Milton's wound but told him he would never be able to use the arm again. Milton's arm healed but was of little use and noticeably shorter than his right arm.

In April 1906, at the time of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, Goodfellow had remarried and was living at the St. Francis Hotel

The Westin St. Francis, formerly known as St. Francis Hotel, is a hotel located on Powell and Geary Streets on Union Square, San Francisco, California. The two 12-story south wings of the hotel were built in 1904, and the double-width north wing ...

. He lost all of his records and personal manuscripts in the hotel and his office due to the earthquake and subsequent fires. His finances were ruined and Goodfellow returned to the Southern Pacific Railroad, where he was chief surgeon in Guaymas

Guaymas () is a city in Guaymas Municipality, in the southwest part of the state of Sonora, in northwestern Mexico. The city is south of the state capital of Hermosillo, and from the U.S. border. The municipality is located on the Gulf of Cali ...

, Mexico, from 1907 to 1910.

Death

Goodfellow fell ill in the summer of 1910 with an illness which he had reportedly been exposed to during the Spanish–American War. He sought treatment from his sister Mary's husband, Dr. Charles W. Fish, in Los Angeles. Over the next six months his health gradually declined, and soon a nervous disorder prevented him from performing surgery. He was hospitalized for several weeks at the end of 1910 at Angelus Hospital in Los Angeles. Goodfellow declared he did not want to live any longer and on December 7, 1910, he died. His brother-in-law gave his cause of death as "multipleneuritis

Neuritis () is inflammation of a nerve or the general inflammation of the peripheral nervous system. Inflammation, and frequently concomitant demyelination, cause impaired transmission of neural signals and leads to aberrant nerve function. Neuri ...

". His obituary attributed his death to a nervous breakdown

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. Such features may be persistent, relapsing and remitt ...

. However, a local urologist and others thought alcoholism

Alcoholism is, broadly, any drinking of alcohol that results in significant mental or physical health problems. Because there is disagreement on the definition of the word ''alcoholism'', it is not a recognized diagnostic entity. Predomi ...

may have played a role in his death. Goodfellow was buried in the Angelus-Rosedale Cemetery

Angelus-Rosedale Cemetery is a cemetery in Los Angeles at 1831 West Washington Boulevard in the Pico-Union district, southwest of Downtown.

It was founded as Rosedale Cemetery in 1884, when Los Angeles had a population of approximately 28,000, o ...

in Los Angeles.

Legacy

Goodfellow is credited as the United States' first civiliantrauma surgeon

Trauma surgery is a surgical specialty that utilizes both operative and non-operative management to treat traumatic injuries, typically in an acute setting. Trauma surgeons generally complete residency training in general surgery and often fel ...

. His pioneering work in the treatment of abdominal wounds, specifically those caused by gunshots, as well as his recognition of the significance of sterile technique at a time when much of the medical establishment had not yet accepted it as a surgical necessity, has contributed to his modern image as a physician well ahead of his time. Decades after his death, by the late 1950s, mandatory laparotomy had become and remains the standard of care for managing patients with abdominal penetrating trauma. To recognize financial supporters, the University of Arizona

The University of Arizona (Arizona, U of A, UArizona, or UA) is a public land-grant research university in Tucson, Arizona. Founded in 1885 by the 13th Arizona Territorial Legislature, it was the first university in the Arizona Territory.

T ...

School of Medicine established the George E. Goodfellow Society.

References

Further reading

* *External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Goodfellow, George Emory 1855 births 1910 deaths People from Downieville, California United States Naval Academy alumni American surgeons Physicians from Arizona Physicians from California People of the American Old West People of the Arizona Territory Burials at Angelus-Rosedale Cemetery