Geology of Iceland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The geology of Iceland is unique and of particular interest to

The geology of Iceland is unique and of particular interest to

The tectonic structure of Iceland is characterized by various seismically and volcanically active centers. Iceland is bordered to the south by the

The tectonic structure of Iceland is characterized by various seismically and volcanically active centers. Iceland is bordered to the south by the

Maps and illustrative photos

from

Trønnes, R.G. 2002: Field trip: Introduction. Geology and geodynamics of Iceland. In: S. Planke (ed.) Iceland 2002 – Petroloeum Geology Field Trip Guide, prepared for Statoil Faroes Licence Groups by Volcanic Basin Petroleum Research, Nordic Volcanological Institute and Iceland National Energy Authority, p. 23-43.

Thor Thordarson. Outline of Geology of Iceland. Chapman Conference 2012

* Bamlett M. and J. F. Potter (1994) "Iceland".

Geologists' Association Guide No.52

Interview of geologist Gro Birkefeldt Møller Pedersen about Iceland's geology, in particular its volcanoes.

{{Geology of Europe

The geology of Iceland is unique and of particular interest to

The geology of Iceland is unique and of particular interest to geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid, liquid, and gaseous matter that constitutes Earth and other terrestrial planets, as well as the processes that shape them. Geologists usually study geology, earth science, or geophysics, althou ...

s. Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its ...

lies on the divergent boundary

In plate tectonics, a divergent boundary or divergent plate boundary (also known as a constructive boundary or an extensional boundary) is a linear feature that exists between two tectonic plates that are moving away from each other. Divergent b ...

between the Eurasian plate

The Eurasian Plate is a tectonic plate that includes most of the continent of Eurasia (a landmass consisting of the traditional continents of Europe and Asia), with the notable exceptions of the Indian subcontinent, the Arabian subcontinent an ...

and the North American plate

The North American Plate is a tectonic plate covering most of North America, Cuba, the Bahamas, extreme northeastern Asia, and parts of Iceland and the Azores. With an area of , it is the Earth's second largest tectonic plate, behind the Paci ...

. It also lies above a hotspot, the Iceland plume

The Iceland hotspot is a hotspot which is partly responsible for the high volcanic activity which has formed the Iceland Plateau and the island of Iceland.

Iceland is one of the most active volcanic regions in the world, with eruptions occur ...

. The plume is believed to have caused the formation of Iceland itself, the island first appearing over the ocean surface about 16 to 18 million years ago. The result is an island characterized by repeated volcanism

Volcanism, vulcanism or volcanicity is the phenomenon of eruption of molten rock (magma) onto the surface of the Earth or a solid-surface planet or moon, where lava, pyroclastics, and volcanic gases erupt through a break in the surface called a ...

and geothermal phenomena such as geyser

A geyser (, ) is a spring characterized by an intermittent discharge of water ejected turbulently and accompanied by steam. As a fairly rare phenomenon, the formation of geysers is due to particular hydrogeological conditions that exist only i ...

s.

The eruption of Laki in 1783 caused much devastation and loss of life, leading to a famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including war, natural disasters, crop failure, population imbalance, widespread poverty, an economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenomenon is usually accompan ...

that killed about 25% of the island's population and resulted in a drop in global temperatures, as sulfur dioxide

Sulfur dioxide (IUPAC-recommended spelling) or sulphur dioxide (traditional Commonwealth English) is the chemical compound with the formula . It is a toxic gas responsible for the odor of burnt matches. It is released naturally by volcanic a ...

was spewed into the Northern Hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the Equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined as being in the same celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the solar system as Earth's Nort ...

. This caused crop failures in Europe and may have caused droughts in India. The eruption has been estimated to have killed over six million people globally.

Between 1963 and 1967, the new island of Surtsey

Surtsey (" Surtr's island" in Icelandic, ) is a volcanic island located in the Vestmannaeyjar archipelago off the southern coast of Iceland. At Surtsey is the southernmost point of Iceland. It was formed in a volcanic eruption which began ...

was created off the southwest coast by a volcanic eruption.

Geologic history

The opening of the North Atlantic and the origin of Iceland

Iceland is located above theMid-Atlantic Ridge

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a mid-ocean ridge (a divergent or constructive plate boundary) located along the floor of the Atlantic Ocean, and part of the longest mountain range in the world. In the North Atlantic, the ridge separates the North A ...

. Some scientists believe the hotspot beneath Iceland could have contributed to the rifting of the supercontinent Pangaea

Pangaea or Pangea () was a supercontinent that existed during the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras. It assembled from the earlier continental units of Gondwana, Euramerica and Siberia during the Carboniferous approximately 335 million y ...

and the subsequent formation of the North Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the "Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

. Igneous rock

Igneous rock (derived from the Latin word ''ignis'' meaning fire), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic. Igneous rock is formed through the cooling and solidification of magma o ...

s which arose from this hotspot have been found on both sides of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, which originated 57–53 million years ago ("Ma"), around the time North America and Eurasia separated and sea floor spreading

Seafloor spreading or Seafloor spread is a process that occurs at mid-ocean ridges, where new oceanic crust is formed through volcanic activity and then gradually moves away from the ridge.

History of study

Earlier theories by Alfred Wegener an ...

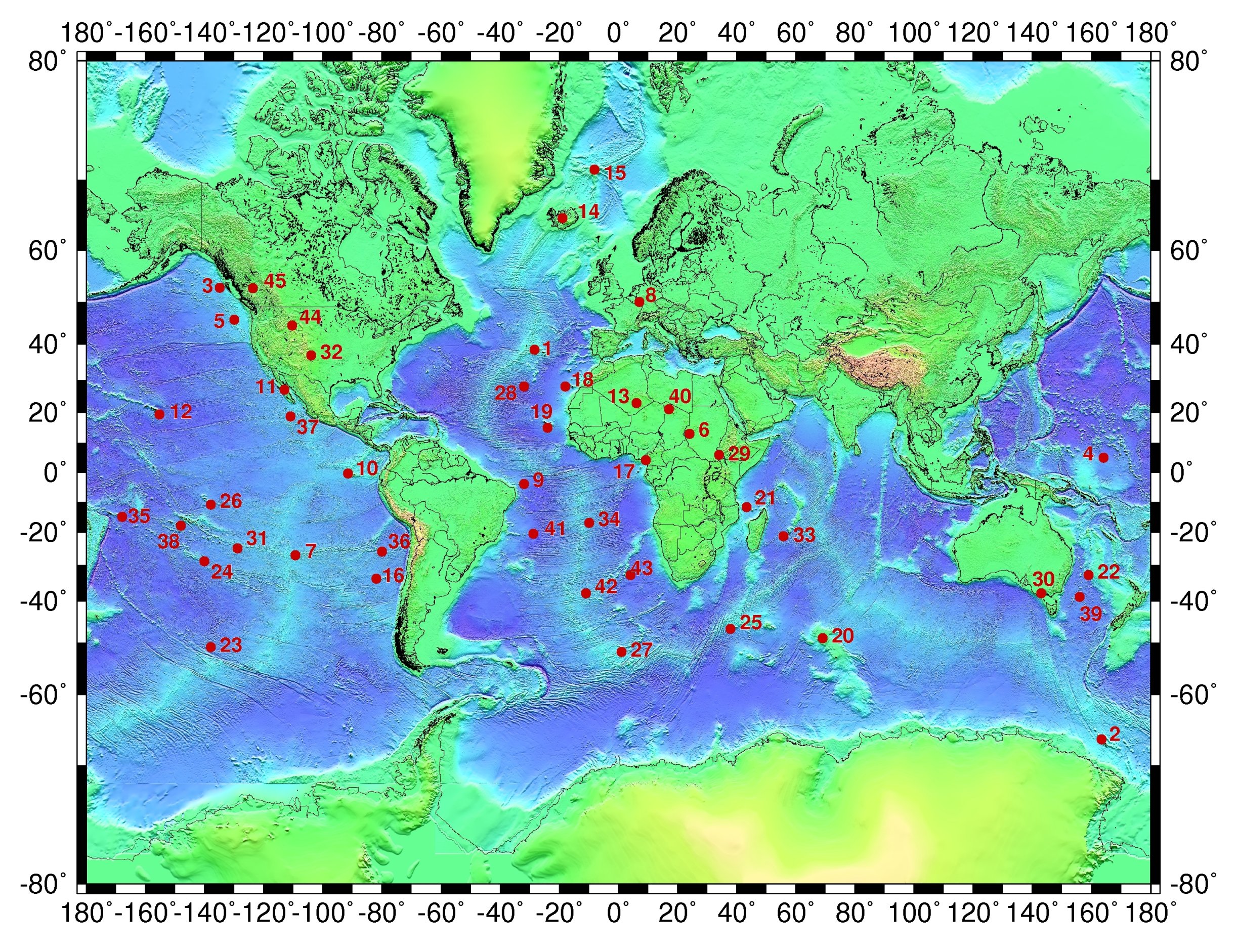

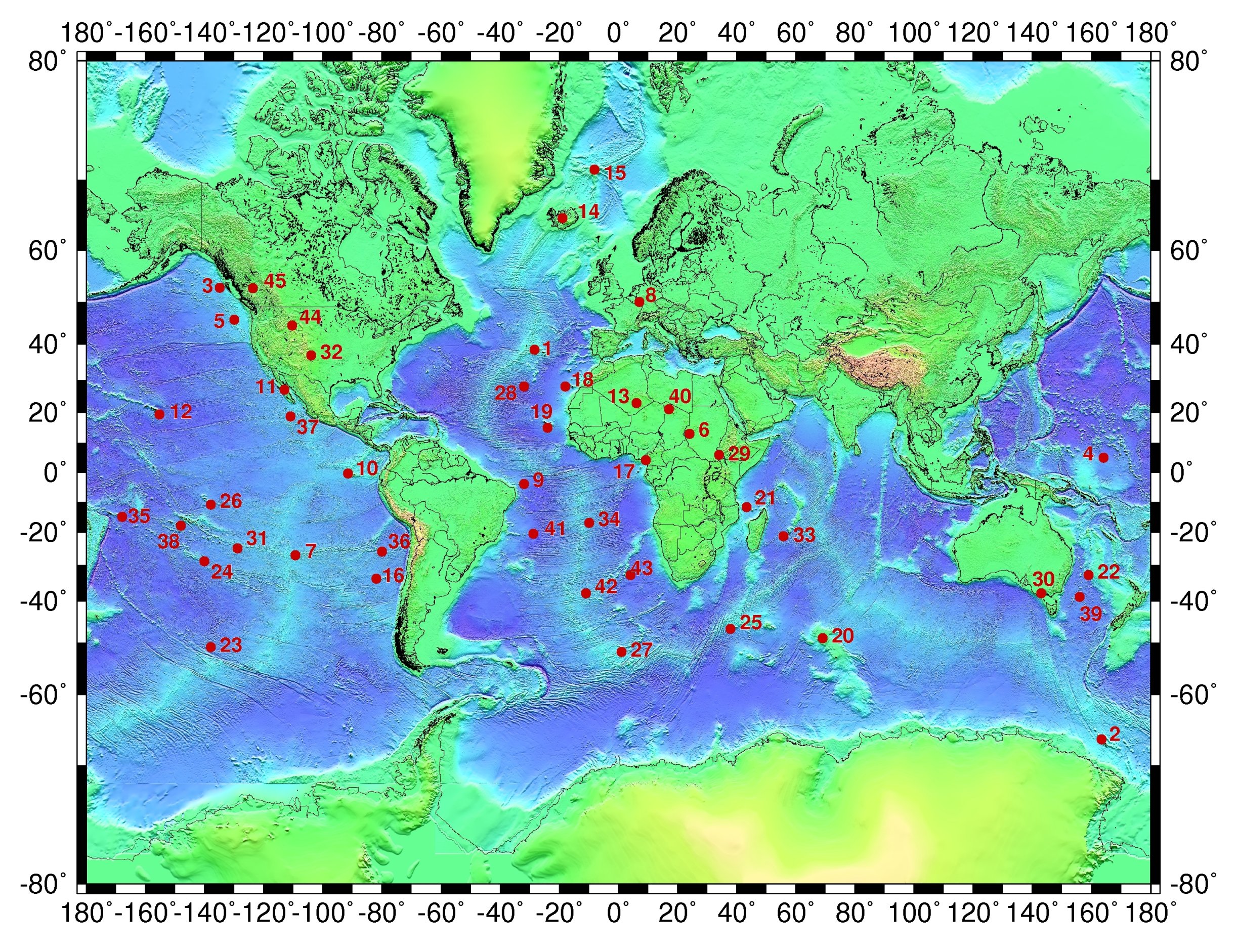

began in the Northeast Atlantic. Geologists can determine plate motion relative to the Icelandic hotspot by examining igneous rocks throughout the Northern Atlantic region. This is possible because certain rocks attributable to hotspot volcanism can be interpreted as volcanic traces left by the Iceland hotspot. By assuming that the hotspot is stationary, geologists use what is called the "hotspot frame of reference" to gather plate motion estimates and to create maps of plate movement on the surface of the Earth relative to a stationary hotspot.

Most researchers of plate motion agree that the Iceland hotspot was probably located beneath Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland ...

for a period of time. As the North Atlantic Ocean continued to spread apart, Greenland was located to the southeast of the Iceland hotspot and likely moved over it 70–40 Ma. Some research using new plate motion data gathered from hotspot reference frames from around the world suggests that the Iceland hotspot's path differs from that estimated from older investigations. Many older rocks (dated 75–70 Ma) located throughout the area to the west are not only located near hypothesized Iceland hotspot paths but are also attributable to hotspot volcanism. This implies that the Iceland hotspot may be much older than the earliest rift

In geology, a rift is a linear zone where the lithosphere is being pulled apart and is an example of extensional tectonics.

Typical rift features are a central linear downfaulted depression, called a graben, or more commonly a half-grabe ...

ing of what is now the northernmost Northeast Atlantic. If this is true, then much of the rifting in the North Atlantic was likely caused by thinning and bulging of the crust as opposed to the more direct influence of the mantle plume

A mantle plume is a proposed mechanism of convection within the Earth's mantle, hypothesized to explain anomalous volcanism. Because the plume head partially melts on reaching shallow depths, a plume is often invoked as the cause of volcanic hot ...

which sustains the Iceland hotspot.

In other scientific work on the path of the Iceland hotspot, no such westward track toward Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

(where the aforementioned older igneous rocks exist) can be detected, which implies that the older igneous rocks found in the Northern Atlantic may not have originated from the hotspot. Although the exact path of the Iceland hotspot is debated, a preponderance of geophysical evidence, such as the geothermal heat flux over Greenland, shows that the hotspot likely moved below Greenland around 80–50 Ma.

Around 60–50 Ma, when the hotspot was located near the eastern coast of Greenland and the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, volcanism, perhaps generated by the Iceland hotspot, connected the Eurasian and North American continents and formed a land bridge

In biogeography, a land bridge is an isthmus or wider land connection between otherwise separate areas, over which animals and plants are able to cross and colonize new lands. A land bridge can be created by marine regression, in which sea leve ...

between the continents while they spread apart. This feature is known as the Greenland Scotland Transverse Ridge, and it now lies below sea level.Denk, Thomas; Grímsson, Friðgeir; Zetter, Reinhard; Símonarson, Leifur (2011-02-23), ''Introduction to the Nature and Geology of Iceland'', 35, retrieved 2018-10-16 About 36 Ma, the Iceland hotspot was fully in contact with the oceanic crust and possibly fed segments of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge which continued to form the oldest rocks located directly to the east and west of modern-day Iceland. The oldest sub-aerial rocks in modern-day Iceland are from 16.5 Ma.

Although most scientists believe Iceland is capable of being an island because it is both in contact with a mantle plume, and being actively split apart by the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, some other convincing seismological and geophysical evidence calls the previously discussed mantle plume/hotspot assumption into question. Some geologists believe there is not enough definitive evidence to suggest a mantle plume exists beneath Iceland because sea floor heat flow through the lithosphere

A lithosphere () is the rigid, outermost rocky shell of a terrestrial planet or natural satellite. On Earth, it is composed of the crust and the portion of the upper mantle that behaves elastically on time scales of up to thousands of years ...

surrounding Iceland does not deviate from normal oceanic lithosphere heat flow that is uninfluenced by a plume. This cold crust hypothesis directly opposes the idea that Iceland is located above a hot mantle plume. Additional evidence indicates that seismic waves created under Iceland do not behave as expected based on other seismic surveys near hypothesized mantle plumes. As it is one of the only places where sea floor spreading can be observed on land, and where there is evidence for a mantle plume, the geological history of Iceland will likely remain a popular area of research.

Glaciations

*Glacier extent *Nunatak

A nunatak (from Inuit language, Inuit ''nunataq'') is the summit or ridge of a mountain that protrudes from an ice field or glacier that otherwise covers most of the mountain or ridge. They are also called glacial islands. Examples are natural p ...

s and ice free areas

*Interglacial

An interglacial period (or alternatively interglacial, interglaciation) is a geological interval of warmer global average temperature lasting thousands of years that separates consecutive glacial periods within an ice age. The current Holocene i ...

s

*Tuya

A tuya is a flat-topped, steep-sided volcano formed when lava erupts through a thick glacier or ice sheet. They are rare worldwide, being confined to regions which were covered by glaciers and had active volcanism during the same period.

As lava ...

s and subglacial volcanism

Holocene changes and volcanism

*Revegetation

Revegetation is the process of replanting and rebuilding the soil of disturbed land. This may be a natural process produced by plant colonization and succession, manmade rewilding projects, accelerated process designed to repair damage to a la ...

*Increased volcanism

Volcanism, vulcanism or volcanicity is the phenomenon of eruption of molten rock (magma) onto the surface of the Earth or a solid-surface planet or moon, where lava, pyroclastics, and volcanic gases erupt through a break in the surface called a ...

* Soil formation

*Isostatic rebound

Post-glacial rebound (also called isostatic rebound or crustal rebound) is the rise of land masses after the removal of the huge weight of ice sheets during the last glacial period, which had caused isostatic depression. Post-glacial rebound ...

*Holocene

The Holocene ( ) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years Before Present (), after the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene togeth ...

sediments

*Coastal erosion

Coastal erosion is the loss or displacement of land, or the long-term removal of sediment and rocks along the coastline due to the action of waves, currents, tides, wind-driven water, waterborne ice, or other impacts of storms. The landwar ...

Rock types

Volcanic deposits

*Tholeiitic

The tholeiitic magma series is one of two main magma series in subalkaline igneous rocks, the other being the calc-alkaline series. A magma series is a chemically distinct range of magma compositions that describes the evolution of a mafic magma ...

volcanic series

* Alkalic volcanic series

*Hyaloclastite

Hyaloclastite is a volcanoclastic accumulation or breccia consisting of glass (from the Greek ''hyalus'') fragments (clasts) formed by quench fragmentation of lava flow surfaces during submarine or subglacial extrusion. It occurs as thin margin ...

*Tephra

Tephra is fragmental material produced by a volcanic eruption regardless of composition, fragment size, or emplacement mechanism.

Volcanologists also refer to airborne fragments as pyroclasts. Once clasts have fallen to the ground, they r ...

s and ash

Intrusive rocks

*Dikes

Dyke (UK) or dike (US) may refer to:

General uses

* Dyke (slang), a slang word meaning "lesbian"

* Dike (geology), a subvertical sheet-like intrusion of magma or sediment

* Dike (mythology), ''Dikē'', the Greek goddess of moral justice

* Dikes ...

* Sills

*Pluton

In geology, an igneous intrusion (or intrusive body or simply intrusion) is a body of intrusive igneous rock that forms by crystallization of magma slowly cooling below the surface of the Earth. Intrusions have a wide variety of forms and com ...

s

Sedimentary deposits

One of the rare examples of sedimentary rocks in Iceland is the sequence of marine and non-marine sediments present on the Tjörnes Peninsula in northern Iceland. ThesePliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.333 million to 2.58late Pleistocene

The Late Pleistocene is an unofficial age in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, also known as Upper Pleistocene from a stratigraphic perspective. It is intended to be the fourth division of the Pleistocene Epoch withi ...

deposits are composed of silt and sandstones, with fossils preserved in the lower layers. The primary fossil types found in the Tjörnes beds are marine mollusk shells and plant remains (lignite).

*Vegetational changes

*Past climate

*Origin of the strata

*Fossil preservation

Active tectonics

The tectonic structure of Iceland is characterized by various seismically and volcanically active centers. Iceland is bordered to the south by the

The tectonic structure of Iceland is characterized by various seismically and volcanically active centers. Iceland is bordered to the south by the Reykjanes Ridge

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a mid-ocean ridge (a divergent or constructive plate boundary) located along the floor of the Atlantic Ocean, and part of the longest mountain range in the world. In the North Atlantic, the ridge separates the North Am ...

segment of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and to the north by the Kolbeinsey Ridge

The Kolbeinsey Ridge is a segment of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge located to the north of Iceland in the Arctic Ocean. It is bounded to the south by the Tjörnes Fracture Zone, which connects the submarine ridge to the on-shore Northern Volcanic Zone ri ...

. Rifting in the southern part of Iceland is focused in two main parallel rift zone

A rift zone is a feature of some volcanoes, especially shield volcanoes, in which a set of linear cracks (or rifts) develops in a volcanic edifice, typically forming into two or three well-defined regions along the flanks of the vent. Believed t ...

s. The Reykjanes Peninsula

Southern Peninsula ( is, Suðurnes ) is an administrative unit and part of Reykjanesskagi (pronounced ), or Reykjanes Peninsula, a region in southwest Iceland. It was named after Reykjanes, the southwestern tip of Reykjanesskagi.

The region ha ...

Rift in SW Iceland is the landward continuation of the Reykjanes Ridge that connects to the Western Volcanic Zone (WVZ). The more active Eastern Volcanic Zone (EVZ) represents a rift jump, although it is unclear how the eastward propagation of the main rifting activity has occurred. The offset between the WVZ and the EVZ is accommodated by the South Iceland Seismic Zone, an area characterized by high earthquake activity. The EVZ transitions northward into the Northern Volcanic Zone (NVZ), which contains Krafla

Krafla () is a volcanic caldera of about 10 km in diameter with a 90 km long fissure zone. It is located in the north of Iceland in the Mývatn region and is situated on the Iceland hotspot atop the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, which forms the d ...

volcano. The NVZ is connected to the Kolbeinsey Ridge by the Tjörnes Fracture Zone, another major center of seismicity and deformation.

A great deal of volcanic activity was occurring in the Reykjanes Peninsula in 2020 and into 2021, after nearly 800 years of inactivity. After the eruption of the Fagradalsfjall volcano on 19 March 2021, National Geographic

''National Geographic'' (formerly the ''National Geographic Magazine'', sometimes branded as NAT GEO) is a popular American monthly magazine published by National Geographic Partners. Known for its photojournalism, it is one of the most widel ...

's experts predicted that this "may mark the start of decades of volcanic activity". The eruption was small leading to a prediction that this volcano was unlikely to threaten "any population centers".

Modern glaciers

Glaciers cover about 11% of Iceland; easily the largest of these isVatnajökull

Vatnajökull ( Icelandic pronunciation: , literally "Glacier of Lakes"; sometimes translated as Vatna Glacier in English) is the largest and most voluminous ice cap in Iceland, and the second largest in area in Europe after the Severny Island i ...

. As many glaciers overlie active volcanoes, subglacial eruptions can pose hazards due to sudden floods produced by glacial meltwater, known as jökulhlaup

A jökulhlaup ( ) (literally "glacial run") is a type of glacial outburst flood. It is an Icelandic term that has been adopted in glaciological terminology in many languages.

It originally referred to the well-known subglacial outburst flood ...

. Icelandic glaciers have generally been retreating over the past 100 years; Vatnajökull has lost as much as 10% of its volume.

Human impact and natural catastrophes

*Overgrazing

Overgrazing occurs when plants are exposed to intensive grazing for extended periods of time, or without sufficient recovery periods. It can be caused by either livestock in poorly managed agricultural applications, game reserves, or nature res ...

:*Soil erosion

Soil erosion is the denudation or wearing away of the upper layer of soil. It is a form of soil degradation. This natural process is caused by the dynamic activity of erosive agents, that is, water, ice (glaciers), snow, air (wind), plants, a ...

*Jökulhlaup

A jökulhlaup ( ) (literally "glacial run") is a type of glacial outburst flood. It is an Icelandic term that has been adopted in glaciological terminology in many languages.

It originally referred to the well-known subglacial outburst flood ...

* Fluorosis

* Laki eruption

*2008 Iceland earthquake

The 2008 Iceland earthquake was a doublet earthquake that struck on May 29 at 15:46 UTC in southwestern Iceland.. The recorded magnitudes of the two main quakes were 5.9 and 5.8 , respectively, giving a composite magnitude of 6.1 . There were ...

*Deforestation

Deforestation or forest clearance is the removal of a forest or stand of trees from land that is then converted to non-forest use. Deforestation can involve conversion of forest land to farms, ranches, or urban use. The most concentrated ...

*Geothermal energy

Geothermal energy is the thermal energy in the Earth's crust which originates from the formation of the planet and from radioactive decay of materials in currently uncertain but possibly roughly equal proportions. The high temperature and pr ...

use

See also

References

External links

Maps and illustrative photos

from

Union College

Union College is a private liberal arts college in Schenectady, New York. Founded in 1795, it was the first institution of higher learning chartered by the New York State Board of Regents, and second in the state of New York, after Columbia Co ...

Trønnes, R.G. 2002: Field trip: Introduction. Geology and geodynamics of Iceland. In: S. Planke (ed.) Iceland 2002 – Petroloeum Geology Field Trip Guide, prepared for Statoil Faroes Licence Groups by Volcanic Basin Petroleum Research, Nordic Volcanological Institute and Iceland National Energy Authority, p. 23-43.

Thor Thordarson. Outline of Geology of Iceland. Chapman Conference 2012

* Bamlett M. and J. F. Potter (1994) "Iceland".

Geologists' Association Guide No.52

Interview of geologist Gro Birkefeldt Møller Pedersen about Iceland's geology, in particular its volcanoes.

{{Geology of Europe