Geologic fault on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

In

Owing to

Owing to

''Slip'' is defined as the relative movement of geological features present on either side of a fault plane. A fault's ''sense of slip'' is defined as the relative motion of the rock on each side of the fault concerning the other side. In measuring the horizontal or vertical separation, the ''throw'' of the fault is the vertical component of the separation and the ''heave'' of the fault is the horizontal component, as in "Throw up and heave out".

''Slip'' is defined as the relative movement of geological features present on either side of a fault plane. A fault's ''sense of slip'' is defined as the relative motion of the rock on each side of the fault concerning the other side. In measuring the horizontal or vertical separation, the ''throw'' of the fault is the vertical component of the separation and the ''heave'' of the fault is the horizontal component, as in "Throw up and heave out".

The vector of slip can be qualitatively assessed by studying any drag folding of strata, which may be visible on either side of the fault. Drag folding is a zone of folding close to a fault that likely arises from frictional resistance to movement on the fault. The direction and magnitude of heave and throw can be measured only by finding common intersection points on either side of the fault (called a

The vector of slip can be qualitatively assessed by studying any drag folding of strata, which may be visible on either side of the fault. Drag folding is a zone of folding close to a fault that likely arises from frictional resistance to movement on the fault. The direction and magnitude of heave and throw can be measured only by finding common intersection points on either side of the fault (called a

In a strike-slip fault (also known as a ''wrench fault'', ''tear fault'' or ''transcurrent fault''), the fault surface (plane) is usually near vertical, and the footwall moves laterally either left or right with very little vertical motion. Strike-slip faults with left-lateral motion are also known as ''sinistral'' faults and those with right-lateral motion as ''dextral'' faults. Each is defined by the direction of movement of the ground as would be seen by an observer on the opposite side of the fault.

A special class of strike-slip fault is the ''

In a strike-slip fault (also known as a ''wrench fault'', ''tear fault'' or ''transcurrent fault''), the fault surface (plane) is usually near vertical, and the footwall moves laterally either left or right with very little vertical motion. Strike-slip faults with left-lateral motion are also known as ''sinistral'' faults and those with right-lateral motion as ''dextral'' faults. Each is defined by the direction of movement of the ground as would be seen by an observer on the opposite side of the fault.

A special class of strike-slip fault is the ''

Dip-slip faults can be either ''normal'' (" extensional") or ''reverse''.

Dip-slip faults can be either ''normal'' (" extensional") or ''reverse''.

In a normal fault, the hanging wall moves downward, relative to the footwall. A downthrown block between two normal faults dipping towards each other is a

In a normal fault, the hanging wall moves downward, relative to the footwall. A downthrown block between two normal faults dipping towards each other is a  Flat segments of thrust fault planes are known as ''flats'', and inclined sections of the thrust are known as ''ramps''. Typically, thrust faults move ''within'' formations by forming flats and climb up sections with ramps.

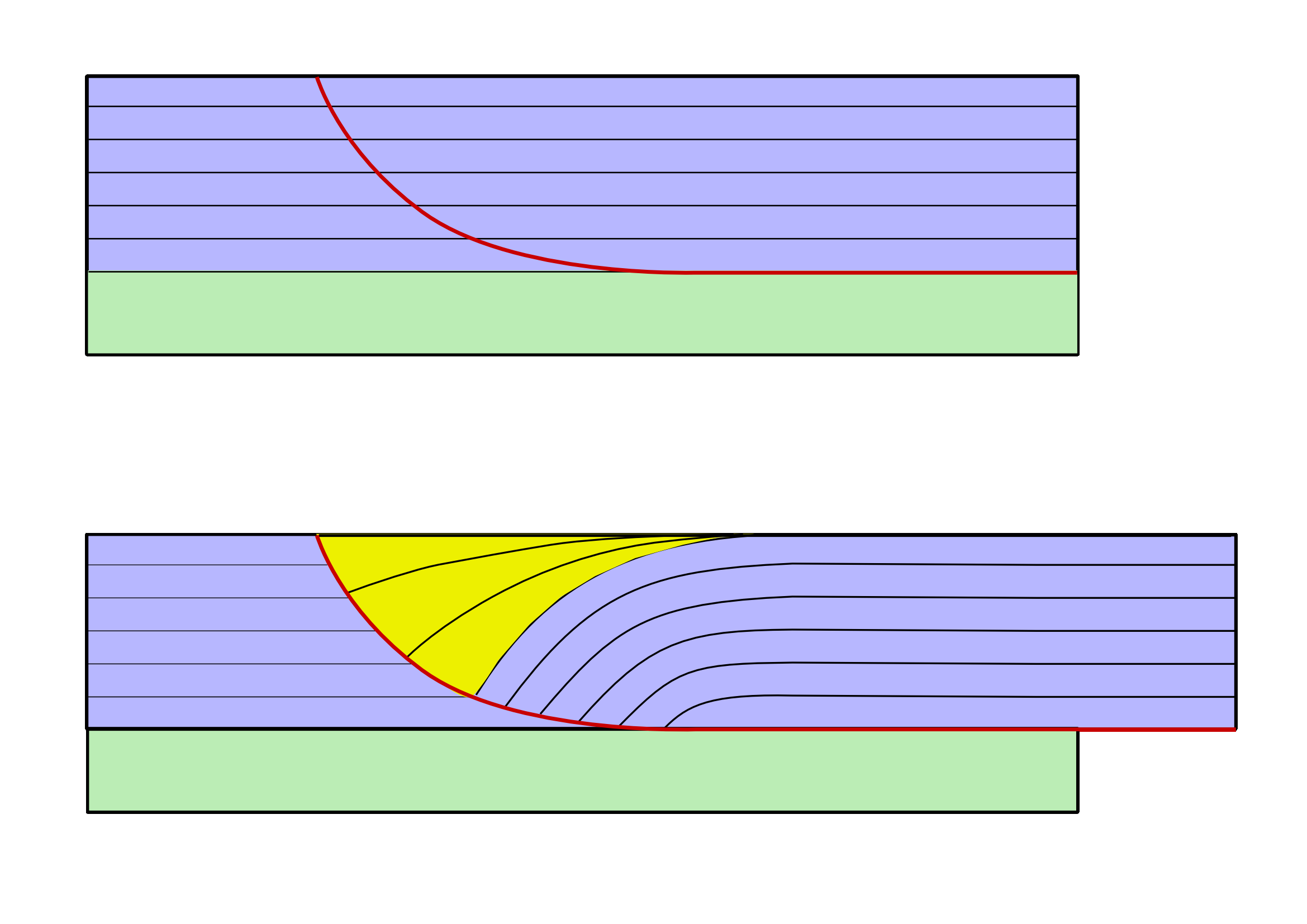

Fault-bend folds are formed by the movement of the hanging wall over a non-planar fault surface and are found associated with both extensional and thrust faults.

Faults may be reactivated at a later time with the movement in the opposite direction to the original movement (fault inversion). A normal fault may therefore become a reverse fault and vice versa.

Thrust faults form nappes and klippen in the large thrust belts. Subduction zones are a special class of thrusts that form the largest faults on Earth and give rise to the largest earthquakes.

Flat segments of thrust fault planes are known as ''flats'', and inclined sections of the thrust are known as ''ramps''. Typically, thrust faults move ''within'' formations by forming flats and climb up sections with ramps.

Fault-bend folds are formed by the movement of the hanging wall over a non-planar fault surface and are found associated with both extensional and thrust faults.

Faults may be reactivated at a later time with the movement in the opposite direction to the original movement (fault inversion). A normal fault may therefore become a reverse fault and vice versa.

Thrust faults form nappes and klippen in the large thrust belts. Subduction zones are a special class of thrusts that form the largest faults on Earth and give rise to the largest earthquakes.

A fault which has a component of dip-slip and a component of strike-slip is termed an oblique-slip fault. Nearly all faults have some component of both dip-slip and strike-slip; hence, defining a fault as oblique requires both dip and strike components to be measurable and significant. Some oblique faults occur within transtensional and transpressional regimes, and others occur where the direction of extension or shortening changes during the deformation but the earlier formed faults remain active.

The ''hade'' angle is defined as the complement of the dip angle; it is the angle between the fault plane and a vertical plane that strikes parallel to the fault.

A fault which has a component of dip-slip and a component of strike-slip is termed an oblique-slip fault. Nearly all faults have some component of both dip-slip and strike-slip; hence, defining a fault as oblique requires both dip and strike components to be measurable and significant. Some oblique faults occur within transtensional and transpressional regimes, and others occur where the direction of extension or shortening changes during the deformation but the earlier formed faults remain active.

The ''hade'' angle is defined as the complement of the dip angle; it is the angle between the fault plane and a vertical plane that strikes parallel to the fault.

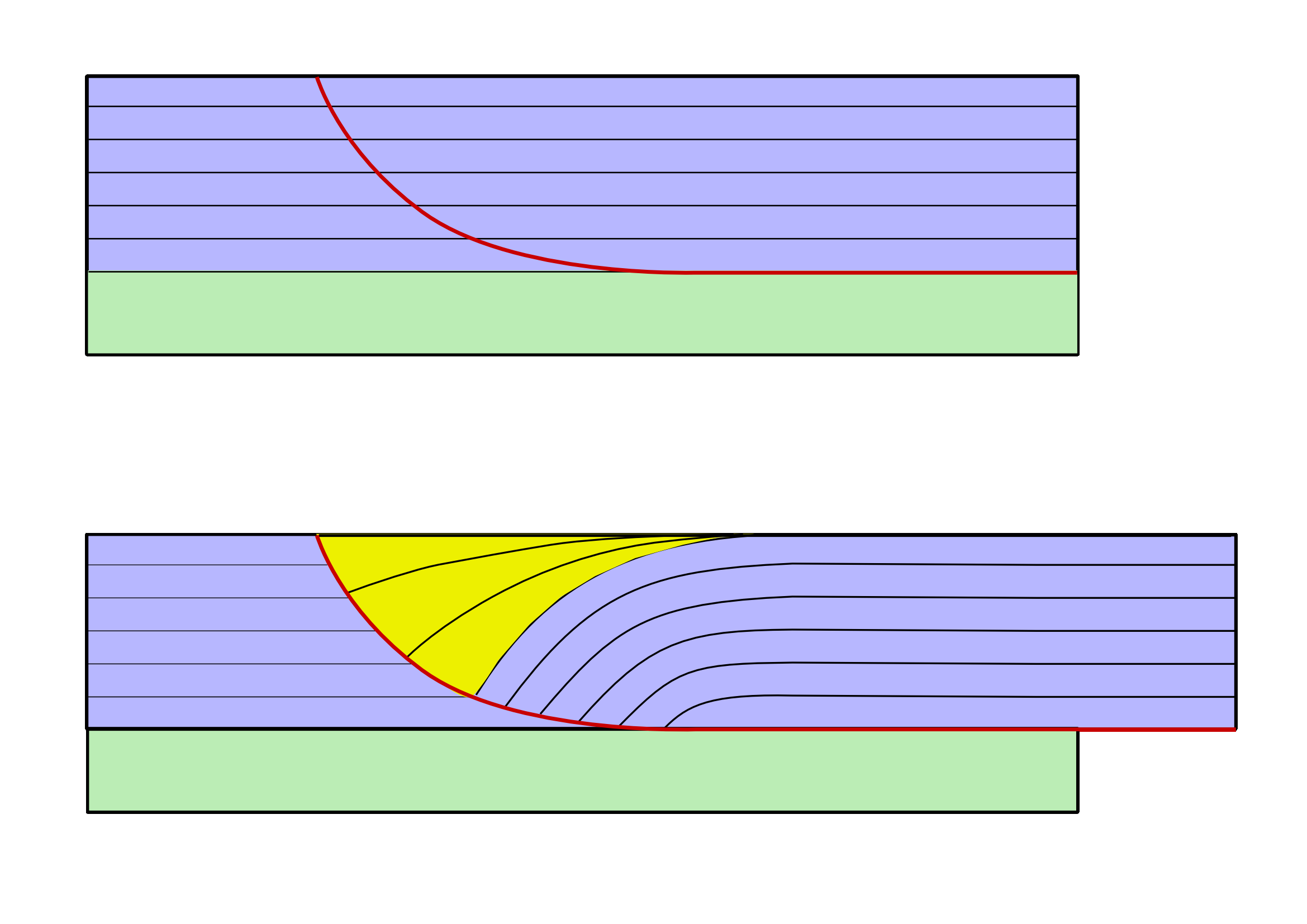

Listric faults are similar to normal faults but the fault plane curves, the dip being steeper near the surface, then shallower with increased depth. The dip may flatten into a sub-horizontal décollement, resulting in a horizontal slip on a horizontal plane. The illustration shows slumping of the hanging wall along a listric fault. Where the hanging wall is absent (such as on a cliff) the footwall may slump in a manner that creates multiple listric faults.

Listric faults are similar to normal faults but the fault plane curves, the dip being steeper near the surface, then shallower with increased depth. The dip may flatten into a sub-horizontal décollement, resulting in a horizontal slip on a horizontal plane. The illustration shows slumping of the hanging wall along a listric fault. Where the hanging wall is absent (such as on a cliff) the footwall may slump in a manner that creates multiple listric faults.

All faults have a measurable thickness, made up of deformed rock characteristic of the level in the crust where the faulting happened, of the rock types affected by the fault and of the presence and nature of any mineralising fluids. Fault rocks are classified by their textures and the implied mechanism of deformation. A fault that passes through different levels of the lithosphere will have many different types of fault rock developed along its surface. Continued dip-slip displacement tends to juxtapose fault rocks characteristic of different crustal levels, with varying degrees of overprinting. This effect is particularly clear in the case of detachment faults and major

All faults have a measurable thickness, made up of deformed rock characteristic of the level in the crust where the faulting happened, of the rock types affected by the fault and of the presence and nature of any mineralising fluids. Fault rocks are classified by their textures and the implied mechanism of deformation. A fault that passes through different levels of the lithosphere will have many different types of fault rock developed along its surface. Continued dip-slip displacement tends to juxtapose fault rocks characteristic of different crustal levels, with varying degrees of overprinting. This effect is particularly clear in the case of detachment faults and major

Fault Motion Animations

at IRIS Consortium

Aerial view of the San Andreas fault in the Carrizo Plain, Central California, from "How Earthquakes Happen"

at

LANDSAT image of the San Andreas Fault in southern California, from "What is a Fault?"

at

In

In geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other Astronomical object, astronomical objects, the features or rock (geology), rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology ...

, a fault is a planar fracture

In geology, a fault is a planar fracture or discontinuity in a volume of rock across which there has been significant displacement as a result of rock-mass movements. Large faults within Earth's crust result from the action of plate tectoni ...

or discontinuity in a volume of rock across which there has been significant displacement as a result of rock-mass movements. Large faults within Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's sur ...

's crust result from the action of plate tectonic

Plate tectonics (from the la, label=Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large te ...

forces, with the largest forming the boundaries between the plates, such as the megathrust faults of subduction zones or transform fault

A transform fault or transform boundary, is a fault along a plate boundary where the motion is predominantly horizontal. It ends abruptly where it connects to another plate boundary, either another transform, a spreading ridge, or a subduct ...

s. Energy release associated with rapid movement on active faults is the cause of most earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, fr ...

s. Faults may also displace slowly, by aseismic creep.

A ''fault plane'' is the plane that represents the fracture surface of a fault. A '' fault trace'' or ''fault line'' is a place where the fault can be seen or mapped on the surface. A fault trace is also the line commonly plotted on geologic map

A geologic map or geological map is a special-purpose map made to show various geological features. Rock units or geologic strata are shown by color or symbols. Bedding planes and structural features such as faults, folds, are shown with s ...

s to represent a fault.

A ''fault zone'' is a cluster of parallel faults. However, the term is also used for the zone of crushed rock along a single fault. Prolonged motion along closely spaced faults can blur the distinction, as the rock between the faults is converted to fault-bound lenses of rock and then progressively crushed.

Mechanisms of faulting

Owing to

Owing to friction

Friction is the force resisting the relative motion of solid surfaces, fluid layers, and material elements sliding against each other. There are several types of friction:

*Dry friction is a force that opposes the relative lateral motion of ...

and the rigidity of the constituent rocks, the two sides of a fault cannot always glide or flow past each other easily, and so occasionally all movement stops. The regions of higher friction along a fault plane, where it becomes locked, are called '' asperities''. Stress builds up when a fault is locked, and when it reaches a level that exceeds the strength threshold, the fault ruptures and the accumulated strain energy is released in part as seismic wave

A seismic wave is a wave of acoustic energy that travels through the Earth. It can result from an earthquake, volcanic eruption, magma movement, a large landslide, and a large man-made explosion that produces low-frequency acoustic ener ...

s, forming an earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, fr ...

.

Strain occurs accumulatively or instantaneously, depending on the liquid state of the rock; the ductile lower crust and mantle

A mantle is a piece of clothing, a type of cloak. Several other meanings are derived from that.

Mantle may refer to:

*Mantle (clothing), a cloak-like garment worn mainly by women as fashionable outerwear

**Mantle (vesture), an Eastern Orthodox ve ...

accumulate deformation gradually via shearing

Sheep shearing is the process by which the woollen fleece of a sheep is cut off. The person who removes the sheep's wool is called a '' shearer''. Typically each adult sheep is shorn once each year (a sheep may be said to have been "shorn" o ...

, whereas the brittle upper crust reacts by fracture – instantaneous stress release – resulting in motion along the fault. A fault in ductile rocks can also release instantaneously when the strain rate is too great.

Slip, heave, throw

''Slip'' is defined as the relative movement of geological features present on either side of a fault plane. A fault's ''sense of slip'' is defined as the relative motion of the rock on each side of the fault concerning the other side. In measuring the horizontal or vertical separation, the ''throw'' of the fault is the vertical component of the separation and the ''heave'' of the fault is the horizontal component, as in "Throw up and heave out".

''Slip'' is defined as the relative movement of geological features present on either side of a fault plane. A fault's ''sense of slip'' is defined as the relative motion of the rock on each side of the fault concerning the other side. In measuring the horizontal or vertical separation, the ''throw'' of the fault is the vertical component of the separation and the ''heave'' of the fault is the horizontal component, as in "Throw up and heave out".

The vector of slip can be qualitatively assessed by studying any drag folding of strata, which may be visible on either side of the fault. Drag folding is a zone of folding close to a fault that likely arises from frictional resistance to movement on the fault. The direction and magnitude of heave and throw can be measured only by finding common intersection points on either side of the fault (called a

The vector of slip can be qualitatively assessed by studying any drag folding of strata, which may be visible on either side of the fault. Drag folding is a zone of folding close to a fault that likely arises from frictional resistance to movement on the fault. The direction and magnitude of heave and throw can be measured only by finding common intersection points on either side of the fault (called a piercing point

In geology, a piercing point is defined as a feature (usually a geologic feature, preferably a linear feature) that is cut by a fault, then moved apart. Reconfiguring the piercing point back in its original position is the primary way geologists ...

). In practice, it is usually only possible to find the slip direction of faults, and an approximation of the heave and throw vector.

Hanging wall and footwall

The two sides of a non-vertical fault are known as the ''hanging wall'' and ''footwall''. The hanging wall occurs above the fault plane and the footwall occurs below it. This terminology comes from mining: when working a tabular ore body, the miner stood with the footwall under his feet and with the hanging wall above him. These terms are important for distinguishing different dip-slip fault types: reverse faults and normal faults. In a reverse fault, the hanging wall displaces upward, while in a normal fault the hanging wall displaces downward. Distinguishing between these two fault types is important for determining the stress regime of the fault movement.Fault types

Faults are mainly classified in terms of the angle that the fault plane makes with the earth's surface, known as the dip, and the direction of slip along the fault plane. Based on the direction of slip, faults can be categorized as: * ''strike-slip'', where the offset is predominantly horizontal, parallel to the fault trace; * ''dip-slip'', offset is predominantly vertical and/or perpendicular to the fault trace; or * ''oblique-slip'', combining strike-slip and dip-slip.Strike-slip faults

In a strike-slip fault (also known as a ''wrench fault'', ''tear fault'' or ''transcurrent fault''), the fault surface (plane) is usually near vertical, and the footwall moves laterally either left or right with very little vertical motion. Strike-slip faults with left-lateral motion are also known as ''sinistral'' faults and those with right-lateral motion as ''dextral'' faults. Each is defined by the direction of movement of the ground as would be seen by an observer on the opposite side of the fault.

A special class of strike-slip fault is the ''

In a strike-slip fault (also known as a ''wrench fault'', ''tear fault'' or ''transcurrent fault''), the fault surface (plane) is usually near vertical, and the footwall moves laterally either left or right with very little vertical motion. Strike-slip faults with left-lateral motion are also known as ''sinistral'' faults and those with right-lateral motion as ''dextral'' faults. Each is defined by the direction of movement of the ground as would be seen by an observer on the opposite side of the fault.

A special class of strike-slip fault is the ''transform fault

A transform fault or transform boundary, is a fault along a plate boundary where the motion is predominantly horizontal. It ends abruptly where it connects to another plate boundary, either another transform, a spreading ridge, or a subduct ...

'' when it forms a plate boundary. This class is related to an offset in a spreading center, such as a mid-ocean ridge

A mid-ocean ridge (MOR) is a seafloor mountain system formed by plate tectonics. It typically has a depth of about and rises about above the deepest portion of an ocean basin. This feature is where seafloor spreading takes place along a div ...

, or, less common, within continental lithosphere, such as the Dead Sea Transform in the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

or the Alpine Fault in New Zealand. Transform faults are also referred to as "conservative" plate boundaries since the lithosphere is neither created nor destroyed.

Dip-slip faults

In a normal fault, the hanging wall moves downward, relative to the footwall. A downthrown block between two normal faults dipping towards each other is a

In a normal fault, the hanging wall moves downward, relative to the footwall. A downthrown block between two normal faults dipping towards each other is a graben

In geology, a graben () is a depressed block of the crust of a planet or moon, bordered by parallel normal faults.

Etymology

''Graben'' is a loan word from German, meaning 'ditch' or 'trench'. The word was first used in the geologic conte ...

. An upthrown block between two normal faults dipping away from each other is a horst. The dip of most normal faults is at least 60 degrees but some normal faults dip at less than 45 degrees. Low-angle normal faults with regional tectonic significance may be designated detachment faults.

A reverse fault is the opposite of a normal fault—the hanging wall moves up relative to the footwall. Reverse faults indicate compressive shortening of the crust. The terminology of "normal" and "reverse" comes from coal mining

Coal mining is the process of extracting coal from the ground. Coal is valued for its energy content and since the 1880s has been widely used to generate electricity. Steel and cement industries use coal as a fuel for extraction of iron from ...

in England, where normal faults are the most common.

A ''thrust fault

A thrust fault is a break in the Earth's crust, across which older rocks are pushed above younger rocks.

Thrust geometry and nomenclature

Reverse faults

A thrust fault is a type of reverse fault that has a dip of 45 degrees or less.

If ...

'' has the same sense of motion as a reverse fault, but with the dip of the fault plane at less than 45°. Thrust faults typically form ramps, flats and fault-bend (hanging wall and footwall) folds.

Oblique-slip faults

Listric fault

Listric faults are similar to normal faults but the fault plane curves, the dip being steeper near the surface, then shallower with increased depth. The dip may flatten into a sub-horizontal décollement, resulting in a horizontal slip on a horizontal plane. The illustration shows slumping of the hanging wall along a listric fault. Where the hanging wall is absent (such as on a cliff) the footwall may slump in a manner that creates multiple listric faults.

Listric faults are similar to normal faults but the fault plane curves, the dip being steeper near the surface, then shallower with increased depth. The dip may flatten into a sub-horizontal décollement, resulting in a horizontal slip on a horizontal plane. The illustration shows slumping of the hanging wall along a listric fault. Where the hanging wall is absent (such as on a cliff) the footwall may slump in a manner that creates multiple listric faults.

Ring fault

Ring faults, also known as caldera faults, are faults that occur within collapsed volcaniccaldera

A caldera ( ) is a large cauldron-like hollow that forms shortly after the emptying of a magma chamber in a volcano eruption. When large volumes of magma are erupted over a short time, structural support for the rock above the magma chamber is ...

s and the sites of bolide strikes, such as the Chesapeake Bay impact crater. Ring faults are the result of a series of overlapping normal faults, forming a circular outline. Fractures created by ring faults may be filled by ring dikes.

Synthetic and antithetic faults

''Synthetic'' and ''antithetic'' are terms used to describe minor faults associated with a major fault. Synthetic faults dip in the same direction as the major fault while the antithetic faults dip in the opposite direction. These faults may be accompanied by rollover anticlines (e.g. theNiger Delta

The Niger Delta is the delta of the Niger River sitting directly on the Gulf of Guinea on the Atlantic Ocean in Nigeria. It is located within nine coastal southern Nigerian states, which include: all six states from the South South geopolitic ...

Structural Style).

Fault rock

thrust fault

A thrust fault is a break in the Earth's crust, across which older rocks are pushed above younger rocks.

Thrust geometry and nomenclature

Reverse faults

A thrust fault is a type of reverse fault that has a dip of 45 degrees or less.

If ...

s.

The main types of fault rock include:

* Cataclasite

Cataclasite is a cohesive granular fault rock. Comminution, also known as cataclasis, is an important process in forming cataclasites. They fall into the category of cataclastic rocks which are formed through faulting or fracturing in the upper ...

– a fault rock which is cohesive with a poorly developed or absent planar fabric

Textile is an umbrella term that includes various fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, filaments, threads, different fabric types, etc. At first, the word "textiles" only referred to woven fabrics. However, weaving is not ...

, or which is incohesive, characterised by generally angular clasts and rock fragments in a finer-grained matrix

Matrix most commonly refers to:

* ''The Matrix'' (franchise), an American media franchise

** '' The Matrix'', a 1999 science-fiction action film

** "The Matrix", a fictional setting, a virtual reality environment, within ''The Matrix'' (franchi ...

of similar composition.

** Tectonic or fault breccia – a medium- to coarse-grained cataclasite containing >30% visible fragments.

** Fault gouge – an incohesive, clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4).

Clays develop plasticity when wet, due to a molecular film of water surrounding the clay pa ...

-rich fine- to ultrafine-grained cataclasite, which may possess a planar fabric and containing <30% visible fragments. Rock clasts may be present

*** Clay smear - clay-rich fault gouge formed in sedimentary

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock that are formed by the accumulation or deposition of mineral or organic particles at Earth's surface, followed by cementation. Sedimentation is the collective name for processes that cause these particles ...

sequences containing clay-rich layers which are strongly deformed and sheared into the fault gouge.

* Mylonite – a fault rock which is cohesive and characterized by a well-developed planar fabric resulting from tectonic reduction of grain size, and commonly containing rounded porphyroclast 350px, A mylonite showing a number of (rotated) porphyroclasts: a clear red garnet left in the picture while smaller white feldspar porphyroclasts can be found all over. ''Location'': the tectonics, tectonic contact between the wiktionary:autochth ...

s and rock fragments of similar composition to mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid chemical compound with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2 ...

s in the matrix

* Pseudotachylyte

Pseudotachylyte (sometimes written as pseudotachylite) is an extremely fine-grained to glassy, dark, cohesive rock occurring as veinsTrouw, R.A.J., C.W. Passchier, and D.J. Wiersma (2010) ''Atlas of Mylonites- and related microstructures.'' Spring ...

– ultrafine-grained glassy-looking material, usually black and flint

Flint, occasionally flintstone, is a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as the variety of chert that occurs in chalk or marly limestone. Flint was widely used historically to make stone tools and start ...

y in appearance, occurring as thin planar veins

Veins are blood vessels in humans and most other animals that carry blood towards the heart. Most veins carry deoxygenated blood from the tissues back to the heart; exceptions are the pulmonary and umbilical veins, both of which carry oxygenated ...

, injection veins or as a matrix to pseudoconglomerates or breccia

Breccia () is a rock composed of large angular broken fragments of minerals or rocks cemented together by a fine-grained matrix.

The word has its origins in the Italian language, in which it means "rubble". A breccia may have a variety of ...

s, which infills dilation fractures in the host rock. Pseudotachylyte likely only forms as the result of seismic slip rates and can act as a fault rate indicator on inactive faults.

Impacts on structures and people

In geotechnical engineering, a fault often forms a discontinuity that may have a large influence on the mechanical behavior (strength, deformation, etc.) ofsoil

Soil, also commonly referred to as earth or dirt, is a mixture of organic matter, minerals, gases, liquids, and organisms that together support life. Some scientific definitions distinguish ''dirt'' from ''soil'' by restricting the former ...

and rock masses in, for example, tunnel, foundation, or slope

In mathematics, the slope or gradient of a line is a number that describes both the ''direction'' and the ''steepness'' of the line. Slope is often denoted by the letter ''m''; there is no clear answer to the question why the letter ''m'' is use ...

construction.

The level of a fault's activity can be critical for (1) locating buildings, tanks, and pipelines and (2) assessing the seismic shaking and tsunami

A tsunami ( ; from ja, 津波, lit=harbour wave, ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and other underwater exp ...

hazard to infrastructure and people in the vicinity. In California, for example, new building construction has been prohibited directly on or near faults that have moved within the Holocene

The Holocene ( ) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years Before Present (), after the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene togeth ...

Epoch (the last 11,700 years) of the Earth's geological history. Also, faults that have shown movement during the Holocene plus Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

Epochs (the last 2.6 million years) may receive consideration, especially for critical structures such as power plants, dams, hospitals, and schools. Geologists assess a fault's age by studying soil

Soil, also commonly referred to as earth or dirt, is a mixture of organic matter, minerals, gases, liquids, and organisms that together support life. Some scientific definitions distinguish ''dirt'' from ''soil'' by restricting the former ...

features seen in shallow excavations and geomorphology seen in aerial photographs. Subsurface clues include shears and their relationships to carbonate

A carbonate is a salt of carbonic acid (H2CO3), characterized by the presence of the carbonate ion, a polyatomic ion with the formula . The word ''carbonate'' may also refer to a carbonate ester, an organic compound containing the carbonate ...

nodules, eroded clay, and iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in ...

oxide mineralization, in the case of older soil, and lack of such signs in the case of younger soil. Radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was de ...

of organic

Organic may refer to:

* Organic, of or relating to an organism, a living entity

* Organic, of or relating to an anatomical organ

Chemistry

* Organic matter, matter that has come from a once-living organism, is capable of decay or is the product ...

material buried next to or over a fault shear is often critical in distinguishing active from inactive faults. From such relationships, paleoseismologists can estimate the sizes of past earthquakes

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, fro ...

over the past several hundred years, and develop rough projections of future fault activity.

Faults and ore deposits

Many ore deposits lie on or are associated with faults. This is because the fractured rock associated with fault zones allow for magma ascent or the circulation of mineral-bearing fluids. Intersections of near-vertical faults are often locations of significant ore deposits. An example of a fault hosting valuableporphyry copper deposit

Porphyry copper deposits are copper ore bodies that are formed from hydrothermal fluids that originate from a voluminous magma chamber several kilometers below the deposit itself. Predating or associated with those fluids are vertical dikes o ...

s is northern Chile's Domeyko Fault The Domeyko Fault ( es, Falla Domeyko) or Precordilleran Fault System is a geological fault located in Northern Chile. The fault is of the strike-slip type and runs parallel to the Andes, the coast and the nearby Atacama Fault. The fault origi ...

with deposits at Chuquicamata

Chuquicamata ( ; referred to as Chuqui for short) is the largest open pit copper mine in terms of excavated volume in the world. It is located in the north of Chile, just outside Calama, at above sea level. It is northeast of Antofagasta and ...

, Collahuasi, El Abra

El Abra is the name given to an extensive archeological site, located in the valley of the same name. El Abra is situated in the east of the municipality Zipaquirá extending to the westernmost part of Tocancipá in the department of Cundinamarc ...

, El Salvador

El Salvador (; , meaning " The Saviour"), officially the Republic of El Salvador ( es, República de El Salvador), is a country in Central America. It is bordered on the northeast by Honduras, on the northwest by Guatemala, and on the south ...

, La Escondida and Potrerillos. Further south in Chile Los Bronces and El Teniente porphyry copper deposit lie each at the intersection of two fault systems.

Faults may not always act as conduits to surface. It has been proposed that deep-seated "misoriented" faults may instead be zones where magmas forming porphyry copper stagnate achieving the right time for—and type of—igneous differentiation

In geology, igneous differentiation, or magmatic differentiation, is an umbrella term for the various processes by which magmas undergo bulk chemical change during the partial melting process, cooling, emplacement, or eruption. The sequence of ...

. At a given time differentiated magmas would burst violently out of the fault-traps and head to shallower places in the crust where porphyry copper deposits would be formed.

See also

* Anderson's Theory of Faulting * Aseismic creep * * * * * * Paleostress inversion * * * Vertical displacement – Vertical movement of Earth's crustReferences

Other reading

* * * * *External links

Fault Motion Animations

at IRIS Consortium

Aerial view of the San Andreas fault in the Carrizo Plain, Central California, from "How Earthquakes Happen"

at

USGS

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), formerly simply known as the Geological Survey, is a scientific agency of the United States government. The scientists of the USGS study the landscape of the United States, its natural resources, ...

LANDSAT image of the San Andreas Fault in southern California, from "What is a Fault?"

at

USGS

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), formerly simply known as the Geological Survey, is a scientific agency of the United States government. The scientists of the USGS study the landscape of the United States, its natural resources, ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Fault (Geology)

Structural geology

Stratigraphy

Faults (geology)

Tectonic landforms

Earth's crust