Geography of New Caledonia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The geography of

New Caledonia is made up of a main island, the Grande Terre, and several smaller islands, the

New Caledonia is made up of a main island, the Grande Terre, and several smaller islands, the

The New Caledonian archipelago is a microcontinental island chain which originated as a fragment of

The New Caledonian archipelago is a microcontinental island chain which originated as a fragment of

The

The

Given its geographical isolation since the end of the

Given its geographical isolation since the end of the

Croixdusud.info

a site in both English and French including information on the geography, geology, and biodiversity of the area {{Geography of Oceania

New Caledonia

)

, anthem = ""

, image_map = New Caledonia on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of New Caledonia

, map_caption = Location of New Caledonia

, mapsize = 290px

, subdivision_type = Sovereign st ...

(''Nouvelle-CalГ©donie''), an overseas collectivity

The French overseas collectivities (''collectivitГ© d'outre-mer'' or ''COM'') are first-order administrative divisions of France, like the French regions, but have a semi-autonomous status. The COMs include some former French overseas colonies ...

of France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

located in the subregion

A subregion is a part of a larger region or continent and is usually based on location. Cardinal directions, such as south are commonly used to define a subregion.

United Nations subregions

The Statistics Division of the United Nations (UN) ...

of Melanesia

Melanesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It extends from Indonesia's New Guinea in the west to Fiji in the east, and includes the Arafura Sea.

The region includes the four independent countries of Fiji, V ...

, makes the continental island group unique in the southwest Pacific. Among other things, the island chain has played a role in preserving unique biological lineages from the Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretace ...

. It served as a waystation in the expansion of the predecessors of the Polynesians, the Lapita

The Lapita culture is the name given to a Neolithic Austronesian people and their material culture, who settled Island Melanesia via a seaborne migration at around 1600 to 500 BCE. They are believed to have originated from the northern Phili ...

culture. Under the Free French

Free France (french: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general , Free France was established as a government-in-exile ...

it was a vital naval base for Allied Forces during the War in the Pacific

The Pacific War, sometimes called the AsiaвҖ“Pacific War, was the theater of World War II that was fought in Asia, the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and Oceania. It was geographically the largest theater of the war, including the vast ...

.

The archipelago is located east of Australia, north of New Zealand, south of the Equator, and just west of Fiji and Vanuatu. New Caledonia

)

, anthem = ""

, image_map = New Caledonia on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of New Caledonia

, map_caption = Location of New Caledonia

, mapsize = 290px

, subdivision_type = Sovereign st ...

comprises a main island

An island (or isle) is an isolated piece of habitat that is surrounded by a dramatically different habitat, such as water. Very small islands such as emergent land features on atolls can be called islets, skerries, cays or keys. An isla ...

, Grande Terre, the Loyalty Islands

The Loyalty Islands Province (French ''Province des Г®les LoyautГ©'') is one of three administrative subdivisions of New Caledonia encompassing the Loyalty Island (french: ГҺles LoyautГ©) archipelago in the Pacific, which are located northeast of ...

, and several smaller islands. Approximately half the size of Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the no ...

, the group has a land area of . The islands have a coastline

The coast, also known as the coastline or seashore, is defined as the area where land meets the ocean, or as a line that forms the boundary between the land and the coastline. The Earth has around of coastline. Coasts are important zones in ...

of . New Caledonia claims an exclusive fishing zone to a distance of and a territorial sea of from shore.

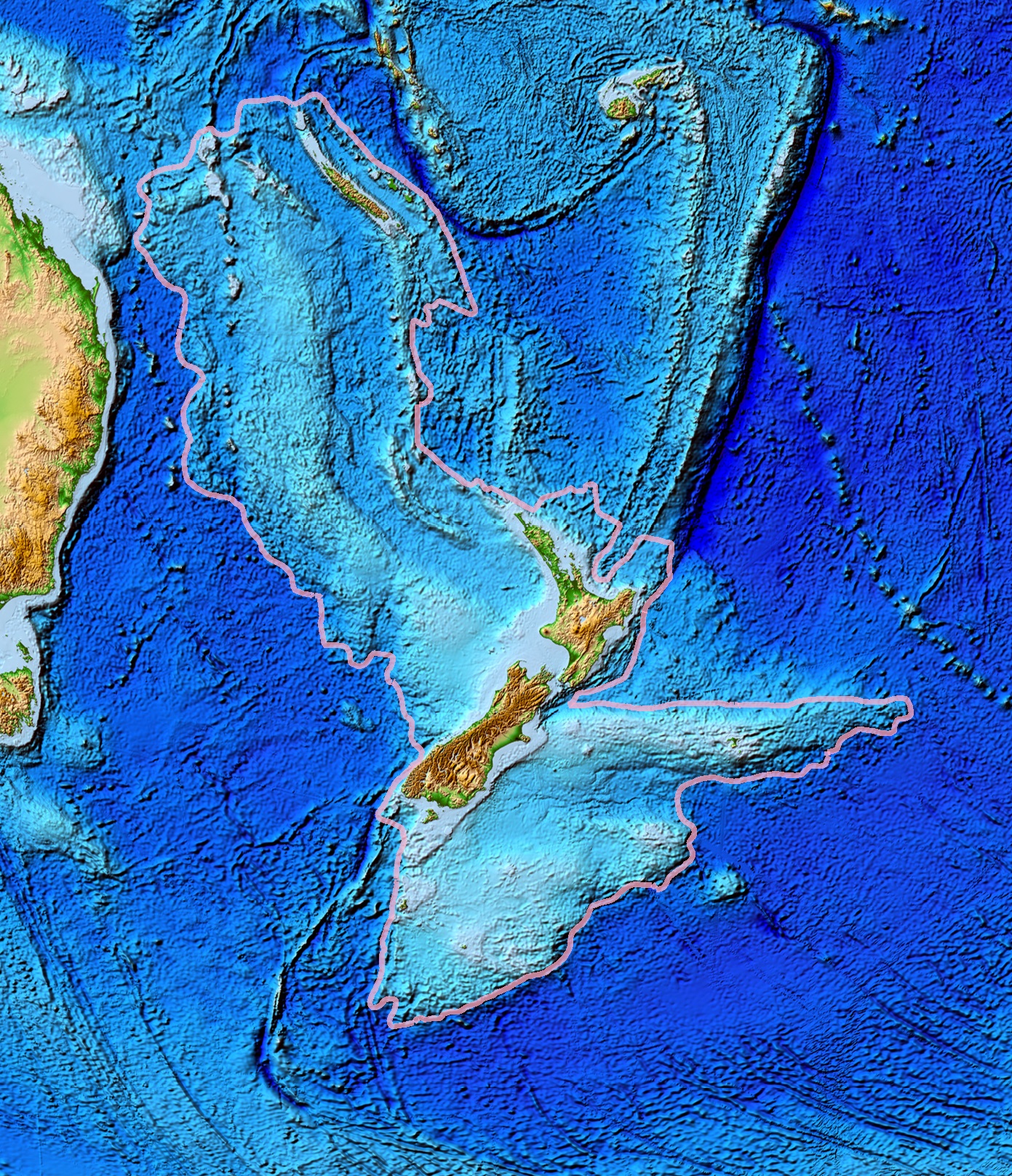

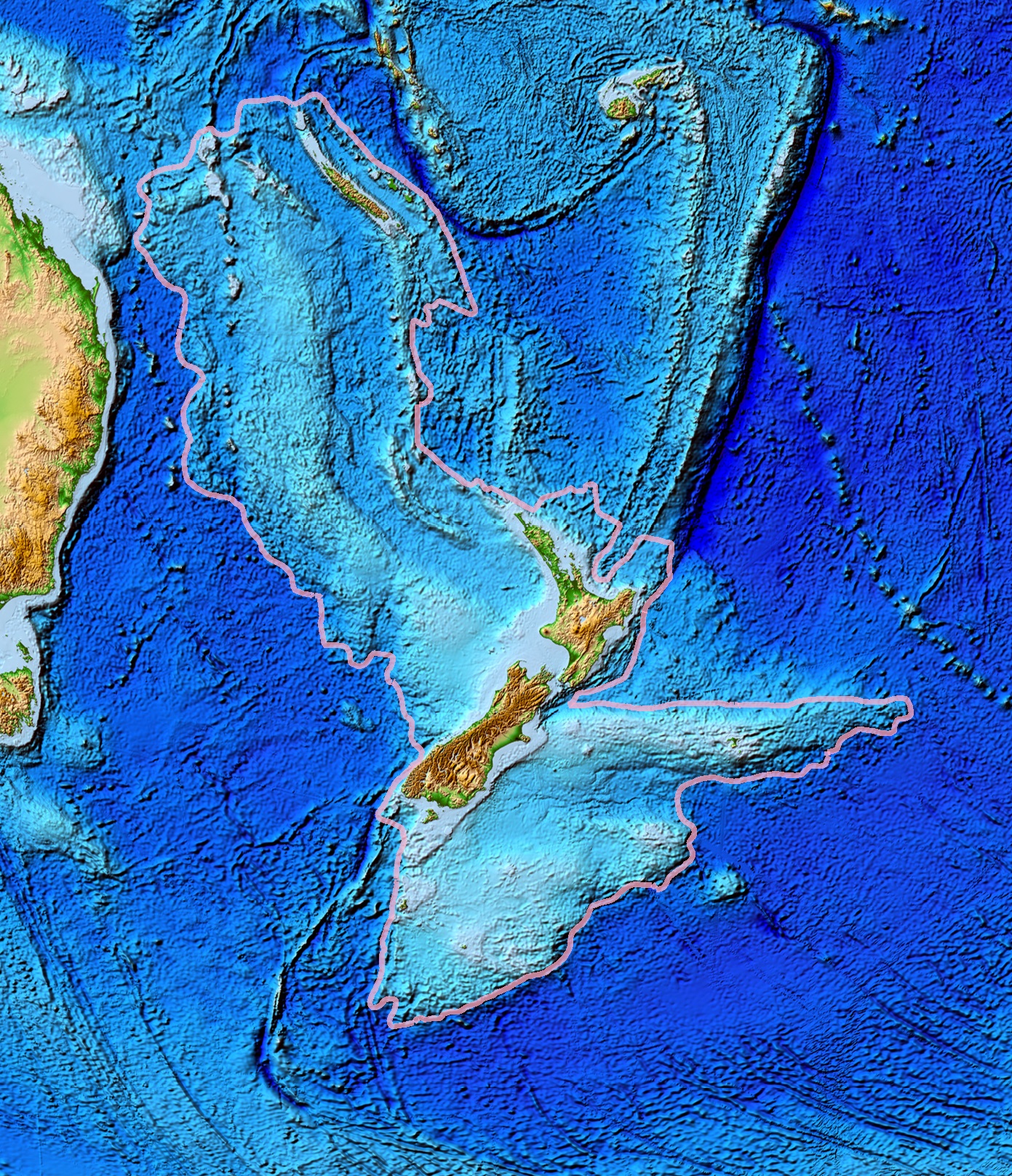

New Caledonia is one of the northernmost parts of an almost entirely (93%) submerged continent

A continent is any of several large landmasses. Generally identified by convention rather than any strict criteria, up to seven geographical regions are commonly regarded as continents. Ordered from largest in area to smallest, these seven ...

called Zealandia

Zealandia (pronounced ), also known as (MДҒori) or Tasmantis, is an almost entirely submerged mass of continental crust that subsided after breaking away from Gondwanaland 83вҖ“79 million years ago.Gurnis, M., Hall, C.E., and Lavier, L.L., ...

which rift

In geology, a rift is a linear zone where the lithosphere is being pulled apart and is an example of extensional tectonics.

Typical rift features are a central linear downfaulted depression, called a graben, or more commonly a half-grabe ...

ed away from Antarctica between 130 and 85 million years ago ( mya), and from Australia 85вҖ“60 mya. (Most of the elongated triangular continental mass of Zealandia is a subsurface plateau. New Zealand is a mountainous above-water promontory in its center, and New Caledonia is a promontory ridge on the continent's northern edge.) New Caledonia itself drifted away from Australia 66 mya, and subsequently drifted in a north-easterly direction, reaching its present position about 50 mya. Given its long stability and isolation, New Caledonia serves as a unique island refugiumвҖ”a sort of biological 'ark'вҖ”hosting a unique ecosystem and preserving Gondwanan

Gondwana () was a large landmass, often referred to as a supercontinent, that formed during the late Neoproterozoic (about 550 million years ago) and began to break up during the Jurassic period (about 180 million years ago). The final stage ...

plant and animal lineages no longer found elsewhere.

Composition

New Caledonia is made up of a main island, the Grande Terre, and several smaller islands, the

New Caledonia is made up of a main island, the Grande Terre, and several smaller islands, the Belep

Belep (sometimes unofficially spelled BГ©lep) is a commune in the North Province of New Caledonia, an overseas territory of France in the Pacific Ocean. It has almost 900 people living on 70 km2.

The commune's territory is made up of the B ...

archipelago to the north of the Grande Terre, the Loyalty Islands

The Loyalty Islands Province (French ''Province des Г®les LoyautГ©'') is one of three administrative subdivisions of New Caledonia encompassing the Loyalty Island (french: ГҺles LoyautГ©) archipelago in the Pacific, which are located northeast of ...

to the east of the Grande Terre, the (Isle of Pines) to the south of the Grande Terre, the Chesterfield Islands and Bellona Reefs further to the west. Each of these four island groups has a different geological origin:

* The New Caledonia archipelago, which includes Grande Terre, Belep

Belep (sometimes unofficially spelled BГ©lep) is a commune in the North Province of New Caledonia, an overseas territory of France in the Pacific Ocean. It has almost 900 people living on 70 km2.

The commune's territory is made up of the B ...

, and the ГҺle des Pins was born as a series of folds of the earth's mantle between the Permian period (251вҖ“299 mya) and the Paleogene

The Paleogene ( ; also spelled Palaeogene or PalГҰogene; informally Lower Tertiary or Early Tertiary) is a geologic period and system that spans 43 million years from the end of the Cretaceous Period million years ago ( Mya) to the beginning o ...

and Neogene

The Neogene ( ), informally Upper Tertiary or Late Tertiary, is a geologic period and system that spans 20.45 million years from the end of the Paleogene Period million years ago ( Mya) to the beginning of the present Quaternary Period Mya. ...

periods (1.5вҖ“66 mya). This mantle

A mantle is a piece of clothing, a type of cloak. Several other meanings are derived from that.

Mantle may refer to:

*Mantle (clothing), a cloak-like garment worn mainly by women as fashionable outerwear

**Mantle (vesture), an Eastern Orthodox ve ...

obduction

Obduction is a geological process whereby denser oceanic crust (and even upper mantle) is scraped off a descending ocean plate at a convergent plate boundary and thrust on top of an adjacent plate. When oceanic and continental plates converge ...

created large areas of peridotite

Peridotite ( ) is a dense, coarse-grained igneous rock consisting mostly of the silicate minerals olivine and pyroxene. Peridotite is ultramafic, as the rock contains less than 45% silica. It is high in magnesium (Mg2+), reflecting the high pr ...

and a bedrock rich in nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow t ...

.

* The Loyalty Islands

The Loyalty Islands Province (French ''Province des Г®les LoyautГ©'') is one of three administrative subdivisions of New Caledonia encompassing the Loyalty Island (french: ГҺles LoyautГ©) archipelago in the Pacific, which are located northeast of ...

, a hundred kilometers to the east, are coral

Corals are marine invertebrates within the class Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact colonies of many identical individual polyps. Coral species include the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and se ...

and limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms w ...

islands built on top of ancient collapsed volcanoes originating due to subduction at the Vanuatu

Vanuatu ( or ; ), officially the Republic of Vanuatu (french: link=no, RГ©publique de Vanuatu; bi, Ripablik blong Vanuatu), is an island country located in the South Pacific Ocean. The archipelago, which is of volcanic origin, is east of ...

trench.

* The Chesterfield Islands, to the northwest, are reef outcroppings of the oceanic plateau.

* The Matthew and Hunter Islands

Hunter Island and Matthew Island are two small and uninhabited high islands in the South Pacific, located east of New Caledonia and south-east of Vanuatu archipelago. Hunter Island and Matthew Island, apart, are claimed by Vanuatu as part of ...

, at east, respectively, are volcanic islands that form the southern end of the arc of the New Hebrides

New Hebrides, officially the New Hebrides Condominium (french: link=no, Condominium des Nouvelles-HГ©brides, "Condominium of the New Hebrides") and named after the Hebrides, Hebrides Scottish archipelago, was the colonial name for the isla ...

.

The Grande Terre is by far the largest of the islands, and the only mountainous island. It has an area of , and is elongated northwestвҖ“southeast, in length and wide. A mountain range runs the length of the island, with five peaks over . The highest point is Mont PaniГ©

Mont PaniГ© is a mountain on the island of Grande Terre in New Caledonia, a special collectivity of France located in the south-west Pacific Ocean. At , it is the island's highest point. Mont PaniГ© is situated in the ChaГ®ne Centrale mountain ...

at elevation. The total area of New Caledonia is , of those being land.

A territorial dispute exists with regard to the uninhabited Matthew and Hunter Islands, which are claimed by both France (as part of New Caledonia) and Vanuatu

Vanuatu ( or ; ), officially the Republic of Vanuatu (french: link=no, RГ©publique de Vanuatu; bi, Ripablik blong Vanuatu), is an island country located in the South Pacific Ocean. The archipelago, which is of volcanic origin, is east of ...

.

Zealandian origin

The New Caledonian archipelago is a microcontinental island chain which originated as a fragment of

The New Caledonian archipelago is a microcontinental island chain which originated as a fragment of Zealandia

Zealandia (pronounced ), also known as (MДҒori) or Tasmantis, is an almost entirely submerged mass of continental crust that subsided after breaking away from Gondwanaland 83вҖ“79 million years ago.Gurnis, M., Hall, C.E., and Lavier, L.L., ...

, a nearly submerged continent

A continent is any of several large landmasses. Generally identified by convention rather than any strict criteria, up to seven geographical regions are commonly regarded as continents. Ordered from largest in area to smallest, these seven ...

or microcontinent

Continental crustal fragments, partly synonymous with microcontinents, are pieces of continents that have broken off from main continental masses to form distinct islands that are often several hundred kilometers from their place of origin.

Caus ...

which was part of the southern supercontinent

In geology, a supercontinent is the assembly of most or all of Earth's continental blocks or cratons to form a single large landmass. However, some geologists use a different definition, "a grouping of formerly dispersed continents", which leav ...

of Gondwana

Gondwana () was a large landmass, often referred to as a supercontinent, that formed during the late Neoproterozoic (about 550 million years ago) and began to break up during the Jurassic period (about 180 million years ago). The final sta ...

during the time of the dinosaurs. The Grande Terre group of New Caledonia, with Mont PaniГ©

Mont PaniГ© is a mountain on the island of Grande Terre in New Caledonia, a special collectivity of France located in the south-west Pacific Ocean. At , it is the island's highest point. Mont PaniГ© is situated in the ChaГ®ne Centrale mountain ...

at as its highest point, is the most elevated part of the Norfolk Ridge, a long and mostly underwater arm of the continent. While they were still one landmass, Zealandia and Australia combined broke away from Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest cont ...

between 85 and 130 million years ago

The abbreviation Myr, "million years", is a unit of a quantity of (i.e. ) years, or 31.556926 teraseconds.

Usage

Myr (million years) is in common use in fields such as Earth science and cosmology. Myr is also used with Mya (million years ago ...

. Australia and Zealandia split apart 60вҖ“85 million years ago. Although biologists consider it contrary to the evidence of surviving Gondwanan lineages, geologists consider the logical possibility that Zealandia may have been completely submerged about 23 million years ago. While a continent like Australia consists of a large body of land surrounded by a fringe of continental shelf, Zealandia consists almost entirely of continental shelf, with the vast majority, some 93%, submerged beneath the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the conti ...

. This viewpoint is not universal. Bernard Pelletier argues that Grande Terre was completely submerged for millions of years, and hence the origin of the flora may not be local in nature, but due to long distance-dispersal.

Zealandia is in area, larger than Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, GrГёnland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland ...

or India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

, and almost half the size of Australia. It is unusually slender, stretching from New Caledonia in the north to beyond New Zealand's subantarctic islands in the south (from latitude 19В° south to 56В° south, analogous to ranging from Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and s ...

to Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay ( crj, text=бҗҗб“ӮбҗҜб’„, translit=WГ®nipekw; crl, text=бҗҗб“Ӯбҗ№б’„, translit=WГ®nipГўkw; iu, text=б‘Іб–Ҹб–…б“ұбҗҠб“—б’ғ бҗғб“—бҗҠ, translit=Kangiqsualuk ilua or iu, text=б‘•б“Ҝбҗ…б”ӯб•җб”ӘбҗҠб–…, translit=Tasiujarjuaq; french: b ...

or from Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, Ш§Щ„ШіЩҲШҜШ§ЩҶ, as-SЕ«dДҒn, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, Ш¬Щ…ЩҮЩҲШұЩҠШ© Ш§Щ„ШіЩҲШҜШ§ЩҶ, link=no, JumhЕ«riyyat as-SЕ«dДҒn), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

to Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic countries, Nordic c ...

in the Northern Hemisphere). New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmassesвҖ”the North Island () and the South Island ()вҖ”and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

is the greatest part of Zealandia above sea level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical datuma standardis ...

, followed by New Caledonia.

Given its continental origin as a fragment of Zealandia, unlike many of the islands of the Pacific such as the Hawaiian chain, New Caledonia is not of geographically recent volcanic

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plat ...

provenance. Its separation from Australia at the end of the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

(65 mya) and from New Zealand in the mid-Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and means "less recen ...

has led to a long period of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

in near complete isolation. New Caledonia's natural heritage significantly comprises species whose ancestors were ancient and primitive flora and fauna present on New Caledonia when it broke away from Gondwana millions of years ago, not only species but entire genera

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nomenclat ...

and even families are unique to the island, and survive nowhere else.

Since the age of the dinosaurs, as the island moved north due to the effects of continental drift

Continental drift is the hypothesis that the Earth's continents have moved over geologic time relative to each other, thus appearing to have "drifted" across the ocean bed. The idea of continental drift has been subsumed into the science of pl ...

, some geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid, liquid, and gaseous matter that constitutes Earth and other terrestrial planets, as well as the processes that shape them. Geologists usually study geology, earth science, or geophysics, althou ...

s assert that it may have been fully submerged at various intervals. Botanist

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek wo ...

s, however, argue that there must have been some areas that remained above sea level

Height above mean sea level is a measure of the vertical distance ( height, elevation or altitude) of a location in reference to a historic mean sea level taken as a vertical datum. In geodesy, it is formalized as '' orthometric heights''.

Th ...

, serving as refugia for the descendants of the original flora that inhabited the island when it broke away from Gondwana. The isolation of New Caledonia was not absolute, however. New species came to New Caledonia while species of Gondwanan origin were able to penetrate further eastward into the Pacific Island region.

Climate

climate

Climate is the long-term weather pattern in an area, typically averaged over 30 years. More rigorously, it is the mean and variability of meteorological variables over a time spanning from months to millions of years. Some of the meteorologi ...

of New Caledonia is tropical

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the Equator. They are defined in latitude by the Tropic of Cancer in the Northern Hemisphere at N and the Tropic of Capricorn in

the Southern Hemisphere at S. The tropics are also referred to ...

, modified by southeasterly trade winds

The trade winds or easterlies are the permanent east-to-west prevailing winds that flow in the Earth's equatorial region. The trade winds blow mainly from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisp ...

. It is hot and humid. Natural hazards are posed in New Caledonia by cyclone

In meteorology, a cyclone () is a large air mass that rotates around a strong center of low atmospheric pressure, counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere as viewed from above (opposite to an an ...

s, which occur most frequently between November and March. While rainfall in the neighboring Vanuatu islands averages two meters annually, from the north of New Caledonia to the south the rain decreases to a little over . The mean annual temperature drops over the same interval from , and seasonality becomes more pronounced. The capital, NoumГ©a

NoumГ©a () is the capital and largest city of the French special collectivity of New Caledonia and is also the largest francophone city in Oceania. It is situated on a peninsula in the south of New Caledonia's main island, Grande Terre, and ...

, located on a peninsula on the southwestern coast of the island normally has a dry season which increases in intensity from August until mid-December, ending suddenly with the coming of rain in January. The northeastern coast of the island receives the most rain, with having been recorded near sea level in PouГ©bo

PouГ©bo is a commune in the North Province of New Caledonia, an overseas territory of France in the Pacific Ocean.

Geography Climate

Pouébo has a tropical monsoon climate (Köppen climate classification

The Köppen climate classification ...

.

Terrain

The terrain of Grande Terre consists of coastalplain

In geography, a plain is a flat expanse of land that generally does not change much in elevation, and is primarily treeless. Plains occur as lowlands along valleys or at the base of mountains, as coastal plains, and as plateaus or uplands ...

s, with mountain

A mountain is an elevated portion of the Earth's crust, generally with steep sides that show significant exposed bedrock. Although definitions vary, a mountain may differ from a plateau in having a limited summit area, and is usually higher ...

s in the interior. The lowest point is the Pacific Ocean, with an elevation of 0 m, and the highest is Mont Panie, with an elevation of .

The Diahot River is the longest river of New Caledonia, flowing for some 60 miles (100 kilometres). It has a catchment area of 620 square kilometres and opens north-westward into the Baie d'Harcourt, flowing towards the northern point of the island along the western escarpment of the Mount Panie.

In 1993, 12% of New Caledonian land was used for permanent pasture

Pasture (from the Latin ''pastus'', past participle of ''pascere'', "to feed") is land used for grazing. Pasture lands in the narrow sense are enclosed tracts of farmland, grazed by domesticated livestock, such as horses, cattle, sheep, or sw ...

, with 39% occupied by forest

A forest is an area of land dominated by trees. Hundreds of definitions of forest are used throughout the world, incorporating factors such as tree density, tree height, land use, legal standing, and ecological function. The United Nations' ...

s and woodland. In 1991, of the land was irrigated

Irrigation (also referred to as watering) is the practice of applying controlled amounts of water to land to help grow crops, landscape plants, and lawns. Irrigation has been a key aspect of agriculture for over 5,000 years and has been develo ...

. A current environmental issue is erosion

Erosion is the action of surface processes (such as water flow or wind) that removes soil, rock, or dissolved material from one location on the Earth's crust, and then transports it to another location where it is deposited. Erosion is d ...

caused by mining exploitation and forest fires.

Biological isolation

Given its geographical isolation since the end of the

Given its geographical isolation since the end of the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

, New Caledonia is a refugium, in effect a biological "Noah's Ark", an island home to both unique living plants and animals and also to its own special fossil endowment. Birds such as the crested and almost flightless kagu (French, ''cagou'') '' Rhynochetos jubatus'', whose closest relative may be the distantly related sunbittern of South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sou ...

, and plants such as ''Amborella trichopoda

''Amborella'' is a monotypic genus of understory shrubs or small trees endemic to the main island, Grande Terre, of New Caledonia in the southwest Pacific Ocean. The genus is the only member of the family Amborellaceae and the order Ambor ...

'', the only known member of the most basal living branch of flowering plant

Flowering plants are plants that bear flowers and fruits, and form the clade Angiospermae (), commonly called angiosperms. The term "angiosperm" is derived from the Greek words ('container, vessel') and ('seed'), and refers to those plants t ...

s, make this island a treasure trove and a critical concern for biologists and conservationists. The island was home to horned fossil turtles ('' Meiolania mackayi'') and terrestrial fossil crocodiles (''Mekosuchus inexpectatus

''Mekosuchus'' is a genus of extinct Australasian crocodiles within the subfamily Mekosuchinae. They are believed to have been made extinct by the arrival of humans on the South Pacific islands where they lived. The species of this genus were sm ...

'') which became extinct shortly after human arrival. There are no native amphibians, with geckos holding many of their niches. The crested gecko (''Correlophus ciliatus

''Correlophus'' is a genus of lizards in the family Diplodactylidae endemic to New Caledonia. It includes three species:

*'' Correlophus belepensis'' Bauer ''et al.'', 2012

*'' Correlophus ciliatus'' Guichenot, 1866 (formerly included in ''Rhacod ...

''), thought to have gone extinct, was rediscovered in 1994.

At 14 inches, Leach's giant gecko (''Rhacodactylus leachianus

''Rhacodactylus leachianus'', commonly known as the New Caledonian giant gecko, Leach's giant gecko, Leachianus Gecko, or simply Leachie, is a large species of gecko in the family Diplodactylidae. The species, which was first described by George ...

''), the world's largestAllison Ballance and Rod Morris, ''"Island Magic; wildlife of the south seas"'', David Bateman publishing, 2003 and a predator of smaller lizards is another native. The only native mammals are four species of bat including the endemic New Caledonia flying fox.

New Caledonia is home to 13 of the 19 extant species of evergreens in the genus ''Araucaria

''Araucaria'' (; original pronunciation: .ЙҫawЛҲka. Йҫja is a genus of evergreen coniferous trees in the family Araucariaceae. There are 20 extant species in New Caledonia (where 14 species are endemic, see New Caledonian ''Araucaria ...

''. The island has been called "a kind of 'Jurassic Park'" because of the archaic characteristics of its highly endemic vegetation. In addition to the basal angiosperm

Flowering plants are plants that bear flowers and fruits, and form the clade Angiospermae (), commonly called angiosperms. The term "angiosperm" is derived from the Greek words ('container, vessel') and ('seed'), and refers to those plants ...

plant genus ''Amborella

''Amborella'' is a monotypic genus of understory shrubs or small trees Endemism, endemic to the main island, Grande Terre (New Caledonia), Grande Terre, of New Caledonia in the southwest Pacific Ocean. The genus is the only member of the family ...

'', for example, the island is home to more gymnosperm

The gymnosperms ( lit. revealed seeds) are a group of seed-producing plants that includes conifers, cycads, '' Ginkgo'', and gnetophytes, forming the clade Gymnospermae. The term ''gymnosperm'' comes from the composite word in el, ОіП…ОјОҪ ...

species than any other tropic landmass, with 43 of its 44 conifer species being unique to the island, which is also home to the world's only known parasitic gymnosperm, the rootless conifer

Conifers are a group of cone-bearing seed plants, a subset of gymnosperms. Scientifically, they make up the division Pinophyta (), also known as Coniferophyta () or Coniferae. The division contains a single extant class, Pinopsida. All ext ...

'' Parasitaxus usta''.

Given their prehistoric appearance, the dry forests of western New Caledonia were chosen as the location for filming the first episode of the BBC miniseries Walking with Dinosaurs

''Walking with Dinosaurs'' is a 1999 six-part nature documentary television miniseries created by Tim Haines and produced by the BBC Science Unit the Discovery Channel and BBC Worldwide, in association with TV Asahi, ProSieben and France 3. Envi ...

, which was set in the Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, AlДӯ б№Јonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

of the late Triassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.36 Mya. The Triassic is the first and shortest per ...

.

Mineral wealth

After a formation discovered inOman

Oman ( ; ar, Ш№ЩҸЩ…ЩҺШ§ЩҶ ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, ШіЩ„Щ’Ш·ЩҶШ©ЩҸ Ш№ЩҸЩ…Ш§ЩҶ ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of ...

in the 1970s, New Caledonia has the planet's largest known outcrop of ultrabasic rock, derived not from the crust, but from an upthrust fold of the more deeply underlying mantle

A mantle is a piece of clothing, a type of cloak. Several other meanings are derived from that.

Mantle may refer to:

*Mantle (clothing), a cloak-like garment worn mainly by women as fashionable outerwear

**Mantle (vesture), an Eastern Orthodox ve ...

of the earth. These mineral-rich rocks are a source of nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow t ...

, chromium

Chromium is a chemical element with the symbol Cr and atomic number 24. It is the first element in group 6. It is a steely-grey, lustrous, hard, and brittle transition metal.

Chromium metal is valued for its high corrosion resistance and hard ...

, iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in ...

, cobalt

Cobalt is a chemical element with the symbol Co and atomic number 27. As with nickel, cobalt is found in the Earth's crust only in a chemically combined form, save for small deposits found in alloys of natural meteoric iron. The free element, p ...

, manganese

Manganese is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Mn and atomic number 25. It is a hard, brittle, silvery metal, often found in minerals in combination with iron. Manganese is a transition metal with a multifaceted array of ...

, silver

Silver is a chemical element with the symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European ''hвӮӮerЗө'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical ...

, gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile ...

, lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cut, ...

and copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pink ...

. The toxicity of the mineral-rich soil has helped preserve the endemic vegetation, which has long been adapted to it, from competition from would-be colonizers which find it unsuitable.

Human geography

Before Western contact

Anthropologically, New Caledonia is considered the southernmost archipelago ofMelanesia

Melanesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It extends from Indonesia's New Guinea in the west to Fiji in the east, and includes the Arafura Sea.

The region includes the four independent countries of Fiji, V ...

, grouping it with the more close by islands to its north, rather than its geologically associated neighbour, New Zealand, to the south. The New Caledonian languages, whose speakers are called Kanaks, and the dialects of the Loyalty Islands

The Loyalty Islands Province (French ''Province des Г®les LoyautГ©'') is one of three administrative subdivisions of New Caledonia encompassing the Loyalty Island (french: ГҺles LoyautГ©) archipelago in the Pacific, which are located northeast of ...

find their closest relatives in the languages of Vanuatu

Vanuatu ( or ; ), officially the Republic of Vanuatu (french: link=no, RГ©publique de Vanuatu; bi, Ripablik blong Vanuatu), is an island country located in the South Pacific Ocean. The archipelago, which is of volcanic origin, is east of ...

to the east. Together, these comprise the Southern Oceanic language family, a member of the Oceanic language

The approximately 450 Oceanic languages are a branch of the Austronesian languages. The area occupied by speakers of these languages includes Polynesia, as well as much of Melanesia and Micronesia. Though covering a vast area, Oceanic languages ...

branch of the Austronesian language family. The Fijian languages

The family of Central Pacific or Central Oceanic languages, also known as FijianвҖ“Polynesian, are a branch of the Oceanic languages.

Classification

Ross et al. (2002) classify the languages as a linkage as follows: Lynch, John, Malcolm Ross ...

, the MДҒori language

MДҒori (), or ('the MДҒori language'), also known as ('the language'), is an Eastern Polynesian language spoken by the MДҒori people, the indigenous population of mainland New Zealand. Closely related to Cook Islands MДҒori, Tuamotuan, and ...

of New Zealand, and other Polynesian language

The Polynesian languages form a genealogical group of languages, itself part of the Oceanic branch of the Austronesian family.

There are 38 Polynesian languages, representing 7 percent of the 522 Oceanic languages, and 3 percent of the Austro ...

s such as Tahitian, Samoan and Hawaiian are cousins of the New Caledonian languages within the Oceanic language family.

Linguistic

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Linguis ...

analysis using the comparative method

In linguistics, the comparative method is a technique for studying the development of languages by performing a feature-by-feature comparison of two or more languages with common descent from a shared ancestor and then extrapolating backwards t ...

provides a detailed family tree of the Austronesian languages to which the native languages of New Caledonia belong. The Lapita

The Lapita culture is the name given to a Neolithic Austronesian people and their material culture, who settled Island Melanesia via a seaborne migration at around 1600 to 500 BCE. They are believed to have originated from the northern Phili ...

culture, hypothesized to have spoken proto-Oceanic, and defined by its typical style of pottery, originated to the northwest in the Bismarck Archipelago

The Bismarck Archipelago (, ) is a group of islands off the northeastern coast of New Guinea in the western Pacific Ocean and is part of the Islands Region of Papua New Guinea. Its area is about 50,000 square km.

History

The first inhabitants o ...

around 1500 BC. The earliest known human settlement of New Caledonia, dated to 1240 Вұ220 BC at the Tiwi rockshelter, is attributed to the Lapitans, who then moved on to Fiji

Fiji ( , ,; fj, Viti, ; Fiji Hindi: аӨ«аӨјаӨҝаӨңаҘҖ, ''FijД«''), officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consis ...

by approximately 900 BC, whence the Polynesian expansion would begin.

Since Western contact

Western colonization of the area began in the 18th century. The British explorerJames Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October вҖ“ 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean and ...

sighted Grande Terre in 1774 and named it New Caledonia, Caledonia being Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

for Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

. In 1853, under Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis NapolГ©on Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-NapolГ©on Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A neph ...

, the area was made a French colony. The French brought colonial subjects such as Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, Ш№ЩҺШұЩҺШЁЩҗЩҠЩҢЩ‘, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, Ш№ЩҺШұЩҺШЁ, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

from the Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ar, Ш§Щ„Щ’Щ…ЩҺШәЩ’ШұЩҗШЁ, al-Maghrib, lit=the west), also known as the Arab Maghreb ( ar, Ш§Щ„Щ…ШәШұШЁ Ш§Щ„Ш№ШұШЁЩҠ) and Northwest Africa, is the western part of North Africa and the Arab world. The region includes Algeria, ...

to settle in the territory. Given its strategic location and that it was unoccupied by Japanese troops it played a vital role under the Free French Forces as an Allied Forces naval base during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countriesвҖ”including all of the great powersвҖ”forming two opposi ...

.

Today, while French is the official language, 28 indigenous tongues are still spoken. At the 2004 census, 97.0% reported they could speak French, whereas only 0.97% reported that they had no knowledge of French. In the same census, 37.1% reported that they could speak (but not necessarily read or write) one of the 28 indigenous Austronesian languages.

At the 1996 census, the indigenous Melanesia

Melanesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It extends from Indonesia's New Guinea in the west to Fiji in the east, and includes the Arafura Sea.

The region includes the four independent countries of Fiji, V ...

n Kanak

The Kanak (French spelling until 1984: Canaque) are the indigenous Melanesian inhabitants of New Caledonia, an overseas collectivity of France in the southwest Pacific. According to the 2019 census, the Kanak make up 41.2% of New Caledonia' ...

community represented 44.6% of the whole population. They are no longer a majority, their proportion of the population having declined due to immigration and other factors. The rest of the population is made up of ethnic groups that arrived in New Caledonia in the last 150 years: Europeans

Europeans are the focus of European ethnology, the field of anthropology related to the various ethnic groups that reside in the states of Europe. Groups may be defined by common genetic ancestry, common language, or both. Pan and Pfeil (20 ...

(34.5%) (predominantly French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

, with German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

, British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

and Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

minorities), Polynesians ( Wallisians, Tahitians

The Tahitians ( ty, MДҒohi; french: Tahitiens) are the Polynesian ethnic group indigenous to Tahiti and thirteen other Society Islands in French Polynesia. The numbers may also include the modern population in these islands of mixed Polynesia ...

) (11.8%), Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Gui ...

ns (2.6%), Vietnamese (1.4%), Ni-Vanuatu

Ni-Vanuatu (informally abbreviated Ni-Van) is a large group of closely related Melanesian ethnic groups native to the island country of Vanuatu. As such, ''Ni-Vanuatu'' are a mixed ethnolinguistic group with a shared ethnogenesis that speak a mu ...

(1.2%), and various other groups (3.9%), Tamils

The Tamil people, also known as Tamilar ( ta, а®Өа®®а®ҝа®ҙа®°аҜҚ, Tamiбё»ar, translit-std=ISO, in the singular or ta, а®Өа®®а®ҝа®ҙа®°аҜҚа®•а®іаҜҚ, Tamiбё»arkaбё·, translit-std=ISO, label=none, in the plural), or simply Tamils (), are a Drav ...

, other South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The region consists of the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.;;;;; ...

ns, Berbers

, image = File:Berber_flag.svg

, caption = The Berber ethnic flag

, population = 36 million

, region1 = Morocco

, pop1 = 14 million to 18 million

, region2 = Algeria

, pop2 ...

, Japanese, Chinese, Fijians

Fijians ( fj, iTaukei, lit=Owners (of the land)) are a nation and ethnic group native to Fiji, who speak Fijian and share a common history and culture.

Fijians, or ''iTaukei'', are the major indigenous people of the Fiji Islands, and live i ...

, Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, Ш№ЩҺШұЩҺШЁЩҗЩҠЩҢЩ‘, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, Ш№ЩҺШұЩҺШЁ, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

, West Indian

A West Indian is a native or inhabitant of the West Indies (the Antilles and the Lucayan Archipelago). For more than 100 years the words ''West Indian'' specifically described natives of the West Indies, but by 1661 Europeans had begun to use it ...

(mostly from other French territories) and a small number of ethnic Africans.

See also

*d'Entrecasteaux Ridge

The d'Entrecasteaux () Ridge (DER) is a double oceanic ridge in the south-west Pacific Ocean, north of New Caledonia and west of Vanuatu Islands. It forms the northern extension of the New CaledoniaвҖ“ Loyalty Islands arc, and is now actively ...

* List of islands of New Caledonia

''Other microcontinental islands:''

* Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: RГ©publique de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Afric ...

* Seychelles

Seychelles (, ; ), officially the Republic of Seychelles (french: link=no, RГ©publique des Seychelles; Creole: ''La Repiblik Sesel''), is an archipelagic state consisting of 115 islands in the Indian Ocean. Its capital and largest city, ...

* Socotra

Socotra or Soqotra (; ar, ШіЩҸЩӮЩҸШ·Щ’ШұЩҺЩүЩ° ; so, Suqadara) is an island of the Republic of Yemen in the Indian Ocean, under the ''de facto'' control of the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council, a secessionist participant in Yemenв ...

References

External links

Croixdusud.info

a site in both English and French including information on the geography, geology, and biodiversity of the area {{Geography of Oceania