Geneticism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Biological determinism, also known as genetic determinism, is the belief that human behaviour is directly controlled by an individual's genes or some component of their

Early ideas of biological determinism centred on the inheritance of undesirable traits, whether physical such as

Early ideas of biological determinism centred on the inheritance of undesirable traits, whether physical such as

physiology

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemical ...

, generally at the expense of the role of the environment, whether in embryonic development or in learning. Genetic reductionism is a similar concept, but it is distinct from genetic determinism in that the former refers to the level of understanding, while the latter refers to the supposedly causal role of genes. Biological determinism has been associated with movements in science and society including eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior o ...

, scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism (racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies ...

, and the debates around the heritability of IQ

Research on the heritability of IQ inquires into the degree of variation in IQ within a population that is due to genetic variation between individuals in that population. There has been significant controversy in the academic community about the ...

, the basis of sexual orientation

Sexual orientation is an enduring pattern of romantic or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, or to both sexes or more than one gender. These attractions are generall ...

, and sociobiology

Sociobiology is a field of biology that aims to examine and explain social behavior in terms of evolution. It draws from disciplines including psychology, ethology, anthropology, evolution, zoology, archaeology, and population genetics. Within ...

.

In 1892, the German evolutionary biologist August Weismann

August Friedrich Leopold Weismann FRS (For), HonFRSE, LLD (17 January 18345 November 1914) was a German evolutionary biologist. Fellow German Ernst Mayr ranked him as the second most notable evolutionary theorist of the 19th century, after Cha ...

proposed in his germ plasm

Germ plasm () is a biological concept developed in the 19th century by the German biologist August Weismann. It states that heritable information is transmitted only by germ cells in the gonads (ovaries and testes), not by somatic cells. The ...

theory that heritable information is transmitted only via germ cell

Germ or germs may refer to:

Science

* Germ (microorganism), an informal word for a pathogen

* Germ cell, cell that gives rise to the gametes of an organism that reproduces sexually

* Germ layer, a primary layer of cells that forms during emb ...

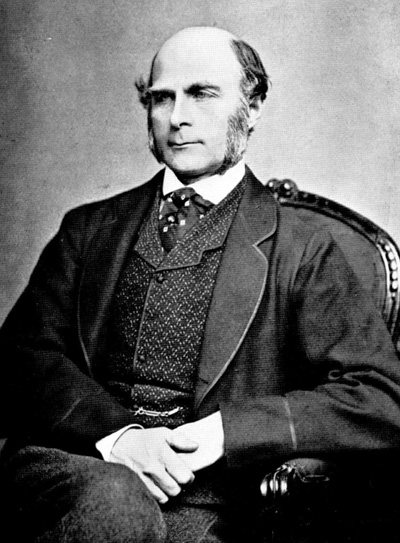

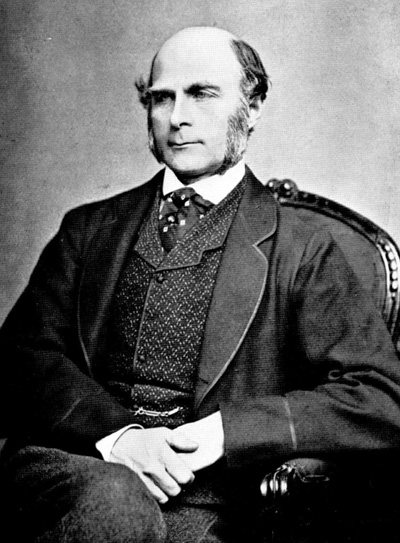

s, which he thought contained determinants (genes). The English polymath Francis Galton, supposing that undesirable traits such as club foot

Clubfoot is a birth defect where one or both feet are rotated inward and downward. Congenital clubfoot is the most common congenital malformation of the foot with an incidence of 1 per 1000 births. In approximately 50% of cases, clubfoot aff ...

and criminality

In ordinary language, a crime is an unlawful act punishable by a state or other authority. The term ''crime'' does not, in modern criminal law, have any simple and universally accepted definition,Farmer, Lindsay: "Crime, definitions of", in Ca ...

were inherited, advocated eugenics, aiming to prevent supposedly defective people from breeding. The American physician Samuel George Morton

Samuel George Morton (January 26, 1799 – May 15, 1851) was an American physician, natural scientist, and writer who argued against the single creation story of the Bible, monogenism, instead supporting a theory of multiple racial creations, p ...

and the French physician Paul Broca

Pierre Paul Broca (, also , , ; 28 June 1824 – 9 July 1880) was a French physician, anatomist and anthropologist. He is best known for his research on Broca's area, a region of the frontal lobe that is named after him. Broca's area is involve ...

attempted to relate the cranial capacity (internal skull volume) to skin colour, intending to show that white people were superior. Other workers such as the American psychologists H. H. Goddard and Robert Yerkes attempted to measure people's intelligence and to show that the resulting scores were heritable, again to demonstrate the supposed superiority of people with white skin.

Galton popularized the phrase nature and nurture, later often used to characterize the heated debate over whether genes or the environment determined human behavior. Scientists, such as ecologists, as well as behavioural geneticists, now see it as obvious that both factors are essential, and that they are intertwined, especially through the mechanisms of epigenetics

In biology, epigenetics is the study of stable phenotypic changes (known as ''marks'') that do not involve alterations in the DNA sequence. The Greek prefix '' epi-'' ( "over, outside of, around") in ''epigenetics'' implies features that are ...

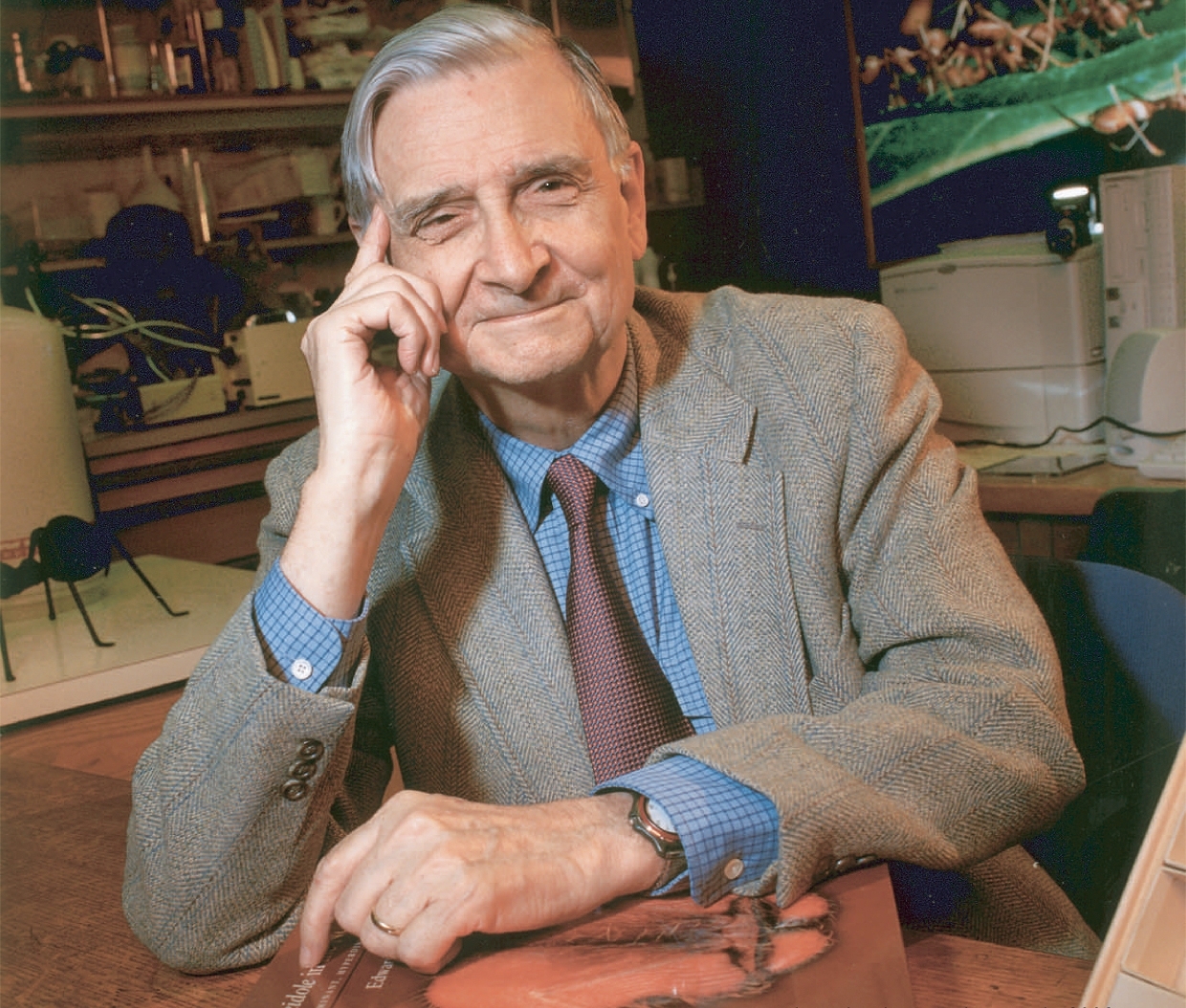

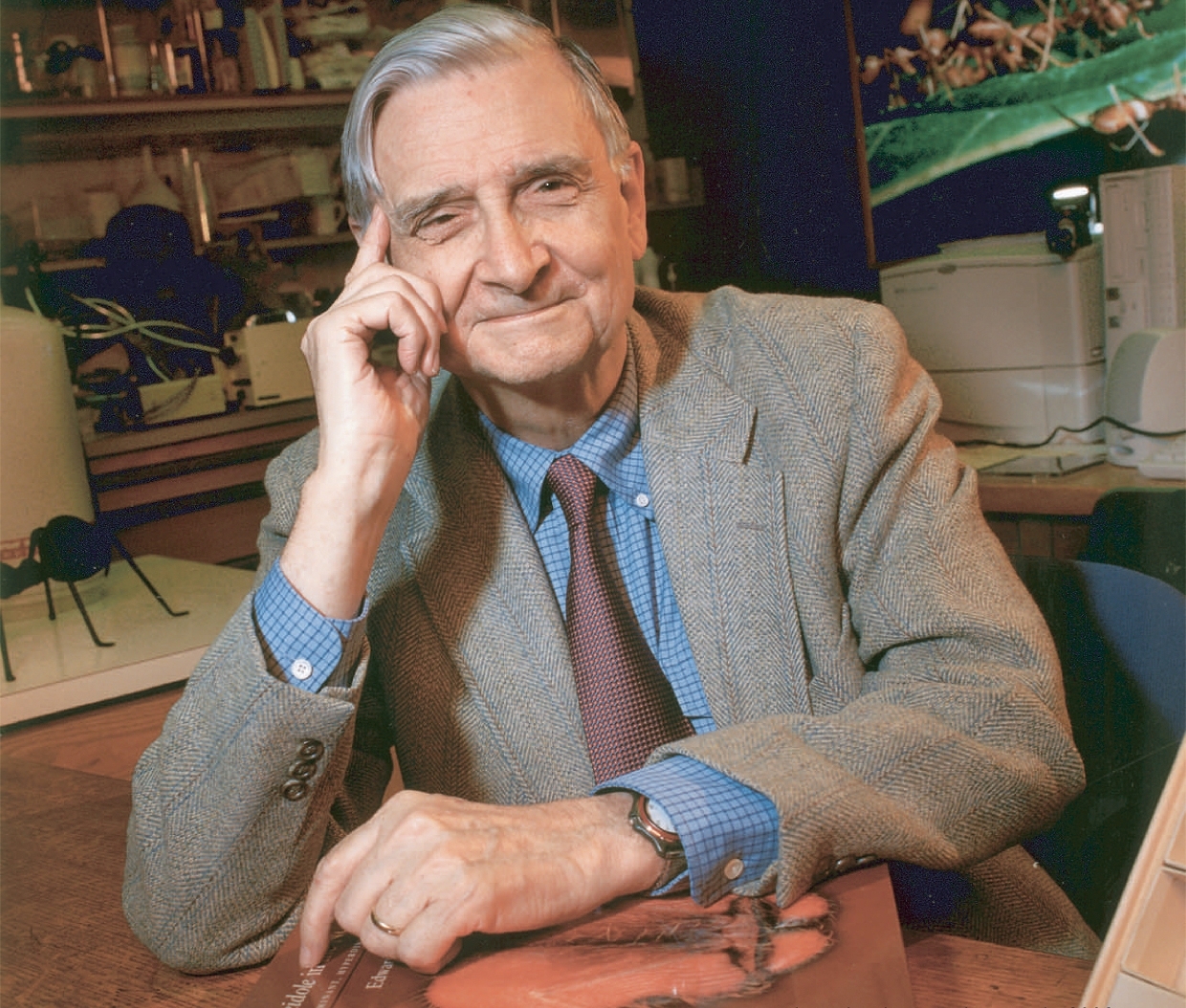

. The American biologist E. O. Wilson

Edward Osborne Wilson (June 10, 1929 – December 26, 2021) was an American biologist, naturalist, entomologist and writer. According to David Attenborough, Wilson was the world's leading expert in his specialty of myrmecology, the study of an ...

, who founded the discipline of sociobiology based on observations of animals such as social insects, controversially suggested that its explanations of social behaviour might apply to humans.

History

Germ plasm

In 1892, the Austrian biologistAugust Weismann

August Friedrich Leopold Weismann FRS (For), HonFRSE, LLD (17 January 18345 November 1914) was a German evolutionary biologist. Fellow German Ernst Mayr ranked him as the second most notable evolutionary theorist of the 19th century, after Cha ...

proposed that multicellular organisms consist of two separate types of cell: somatic cells, which carry out the body's ordinary functions, and germ cell

Germ or germs may refer to:

Science

* Germ (microorganism), an informal word for a pathogen

* Germ cell, cell that gives rise to the gametes of an organism that reproduces sexually

* Germ layer, a primary layer of cells that forms during emb ...

s, which transmit heritable information. He called the material that carried the information, now identified as DNA, the germ plasm

Germ plasm () is a biological concept developed in the 19th century by the German biologist August Weismann. It states that heritable information is transmitted only by germ cells in the gonads (ovaries and testes), not by somatic cells. The ...

, and individual components of it, now called gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "... Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a b ...

s, determinants which controlled the organism. Weismann argued that there is a one-way transfer of information from the germ cells to somatic cells, so that nothing acquired by the body during an organism's life can affect the germ plasm and the next generation. This effectively denied that Lamarckism (inheritance of acquired characteristics) was a possible mechanism of evolution. The modern equivalent of the theory, expressed at molecular rather than cellular level, is the central dogma of molecular biology.

Eugenics

Early ideas of biological determinism centred on the inheritance of undesirable traits, whether physical such as

Early ideas of biological determinism centred on the inheritance of undesirable traits, whether physical such as club foot

Clubfoot is a birth defect where one or both feet are rotated inward and downward. Congenital clubfoot is the most common congenital malformation of the foot with an incidence of 1 per 1000 births. In approximately 50% of cases, clubfoot aff ...

or cleft palate

A cleft lip contains an opening in the upper lip that may extend into the nose. The opening may be on one side, both sides, or in the middle. A cleft palate occurs when the palate (the roof of the mouth) contains an opening into the nose. The ...

, or psychological such as alcoholism

Alcoholism is, broadly, any drinking of alcohol that results in significant mental or physical health problems. Because there is disagreement on the definition of the word ''alcoholism'', it is not a recognized diagnostic entity. Predomi ...

, bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder, previously known as manic depression, is a mental disorder characterized by periods of depression and periods of abnormally elevated mood that last from days to weeks each. If the elevated mood is severe or associated with ...

and criminality

In ordinary language, a crime is an unlawful act punishable by a state or other authority. The term ''crime'' does not, in modern criminal law, have any simple and universally accepted definition,Farmer, Lindsay: "Crime, definitions of", in Ca ...

. The belief that such traits were inherited led to the desire to solve the problem with the eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior o ...

movement, led by a follower of Darwin, Francis Galton (1822–1911), by forcibly reducing breeding by supposedly defective people. By the 1920s, many U.S. states brought in laws permitting the compulsory sterilization of people considered genetically unfit, including inmates of prison

A prison, also known as a jail, gaol (dated, standard English, Australian, and historically in Canada), penitentiary (American English and Canadian English), detention center (or detention centre outside the US), correction center, corre ...

s and psychiatric hospital

Psychiatric hospitals, also known as mental health hospitals, behavioral health hospitals, are hospitals or wards specializing in the treatment of severe mental disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, dissociat ...

s. This was followed by similar laws in Germany, and throughout the Western world, in the 1930s.

Scientific racism

Under the influence of determinist beliefs, the American craniologistSamuel George Morton

Samuel George Morton (January 26, 1799 – May 15, 1851) was an American physician, natural scientist, and writer who argued against the single creation story of the Bible, monogenism, instead supporting a theory of multiple racial creations, p ...

(1799–1851), and later the French anthropologist Paul Broca

Pierre Paul Broca (, also , , ; 28 June 1824 – 9 July 1880) was a French physician, anatomist and anthropologist. He is best known for his research on Broca's area, a region of the frontal lobe that is named after him. Broca's area is involve ...

(1824–1880), attempted to measure the cranial capacities (internal skull volumes) of people of different skin colours, intending to show that whites were superior to the rest, with larger brains. All the supposed proofs from such studies were invalidated by methodological flaws. The results were used to justify slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, and to oppose women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

.

Heritability of IQ

Alfred Binet

Alfred Binet (; 8 July 1857 – 18 October 1911), born Alfredo Binetti, was a French psychologist who invented the first practical IQ test, the Binet–Simon test. In 1904, the French Ministry of Education asked psychologist Alfred Binet to ...

(1857–1911) designed tests specifically to measure performance, not innate ability. From the late 19th century, the American school, led by researchers such as H. H. Goddard (1866–1957), Lewis Terman

Lewis Madison Terman (January 15, 1877 – December 21, 1956) was an American psychologist and author. He was noted as a pioneer in educational psychology in the early 20th century at the Stanford Graduate School of Education. He is best known ...

(1877–1956), and Robert Yerkes (1876–1956), transformed these tests into tools for measuring inherited mental ability. They attempted to measure people's intelligence with IQ tests

An intelligence quotient (IQ) is a total score derived from a set of standardized tests or subtests designed to assess human intelligence. The abbreviation "IQ" was coined by the psychologist William Stern for the German term ''Intelligenzq ...

, to demonstrate that the resulting scores were heritable

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic informa ...

, and so to conclude that people with white skin were superior to the rest. It proved impossible to design culture-independent tests and to carry out testing in a fair way given that people came from different backgrounds, or were newly arrived immigrants, or were illiterate. The results were used to oppose immigration

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not natives or where they do not possess citizenship in order to settle as permanent residents or naturalized citizens. Commuters, tourists, a ...

of people from southern and eastern Europe to America.

Human sexual orientation

Human sexual orientation, which ranges over a continuum from exclusive attraction to the opposite sex to exclusive attraction to the same sex, is caused by the interplay of genetic and environmental influences. There is considerably more evidence for biological causes of sexual orientation than social factors, especially for males.Sociobiology

Sociobiology

Sociobiology is a field of biology that aims to examine and explain social behavior in terms of evolution. It draws from disciplines including psychology, ethology, anthropology, evolution, zoology, archaeology, and population genetics. Within ...

emerged with E. O. Wilson

Edward Osborne Wilson (June 10, 1929 – December 26, 2021) was an American biologist, naturalist, entomologist and writer. According to David Attenborough, Wilson was the world's leading expert in his specialty of myrmecology, the study of an ...

's 1975 book '' Sociobiology: The New Synthesis''. The existence of a putative altruism gene has been debated; the evolutionary biologist W. D. Hamilton

William Donald Hamilton (1 August 1936 – 7 March 2000) was a British evolutionary biologist, recognised as one of the most significant evolutionary theorists of the 20th century.

Hamilton became known for his theoretical work expounding a ...

proposed "genes underlying altruism" in 1964, while the biologist Graham J. Thompson and colleagues identified the genes OXTR

The oxytocin receptor, also known as OXTR, is a protein which functions as receptor for the hormone and neurotransmitter oxytocin. In humans, the oxytocin receptor is encoded by the ''OXTR'' gene which has been localized to human chromosome 3p ...

, CD38, COMT

Catechol-''O''-methyltransferase (COMT; ) is one of several enzymes that degrade catecholamines (neurotransmitters such as dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine), catecholestrogens, and various drugs and substances having a catechol struct ...

, DRD4

The dopamine receptor D4 is a dopamine D2-like G protein-coupled receptor encoded by the gene on chromosome 11 at 11p15.5.

The structure of DRD4 was recently reported in complex with the antipsychotic drug nemonapride.

As with other dopamine ...

, DRD5, IGF2

Insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF-2) is one of three protein hormones that share structural similarity to insulin. The MeSH definition reads: "A well-characterized neutral peptide believed to be secreted by the liver and to circulate in the blo ...

, GABRB2 as candidates "affecting altruism". The geneticist Steve Jones argues that altruistic behaviour like "loving our neighbour" is built into the human genome, with the proviso that neighbour means member of "our tribe", someone who shares many genes with the altruist, and that the behaviour can thus be explained by kin selection

Kin selection is the evolutionary strategy that favours the reproductive success of an organism's relatives, even when at a cost to the organism's own survival and reproduction. Kin altruism can look like altruistic behaviour whose evolution i ...

. Evolutionary biologists such as Jones have argued that genes that did not lead to selfish behaviour would die out compared to genes that did, because the selfish genes would favour themselves. However, the mathematician George Constable and colleagues have argued that altruism can be an evolutionarily stable strategy

An evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS) is a strategy (or set of strategies) that is ''impermeable'' when adopted by a population in adaptation to a specific environment, that is to say it cannot be displaced by an alternative strategy (or set o ...

, making organisms better able to survive random catastrophes.

Nature versus nurture debate

The belief in biological determinism was matched in the 20th century by ablank slate

''Tabula rasa'' (; "blank slate") is the theory that individuals are born without built-in mental content, and therefore all knowledge comes from experience or perception. Epistemological proponents of ''tabula rasa'' disagree with the doctri ...

denial of any possible influence of genes on human behaviour, leading to a long and heated debate about "nature and nurture". By the 21st century, many scientists had come to feel that the dichotomy made no sense. They noted that genes are expressed within an environment, in particular that of prenatal development, and that gene expression is continuously influenced by the environment through mechanisms such as epigenetics

In biology, epigenetics is the study of stable phenotypic changes (known as ''marks'') that do not involve alterations in the DNA sequence. The Greek prefix '' epi-'' ( "over, outside of, around") in ''epigenetics'' implies features that are ...

. Epigenetics provides evidence that human behaviours or physiology

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemical ...

can be decided by interactions between genes and environments. For example, monozygotic twins

Twins are two offspring produced by the same pregnancy.MedicineNet > Definition of TwinLast Editorial Review: 19 June 2000 Twins can be either ''monozygotic'' ('identical'), meaning that they develop from one zygote, which splits and forms two em ...

usually have exactly identical genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding g ...

s. Scientists have focused on comparison studies of such twins for evaluating the heritability of genes and the roles of epigenetics in divergences and similarities between monozygotic twins, and have found that epigenetics plays an important part in human behaviours, including the stress response.

See also

* * * * * * * *References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Biological Determinism Determinism Philosophy of science Determinism