General James Longstreet on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

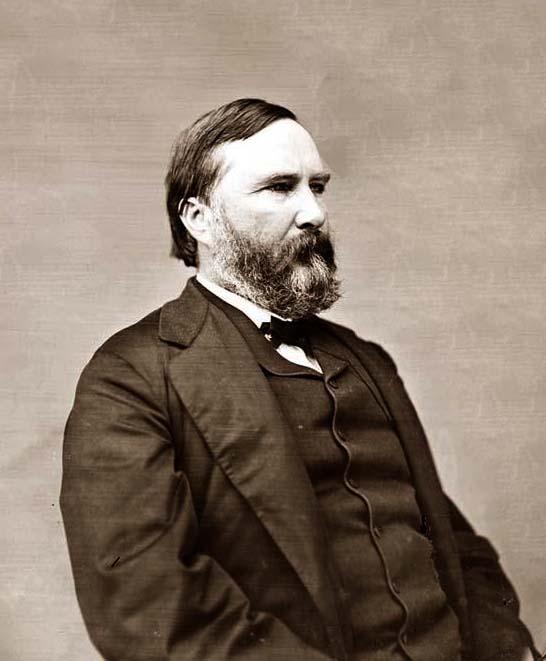

James Longstreet (January 8, 1821January 2, 1904) was one of the foremost

Longstreet arrived in

Longstreet arrived in

On May 31, during the

On May 31, during the

The military reputations of Lee's corps commanders are often characterized as Stonewall Jackson representing the audacious, offensive component of Lee's army, with Longstreet more typically advocating and executing strong defensive strategies and tactics. Wert describes Jackson as the hammer and Longstreet as the anvil of the army. In the first part of the Northern Virginia campaign of August 1862, this stereotype held true, but in the climactic battle, it did not. In June, the Federal Government created the 50,000-strong

The military reputations of Lee's corps commanders are often characterized as Stonewall Jackson representing the audacious, offensive component of Lee's army, with Longstreet more typically advocating and executing strong defensive strategies and tactics. Wert describes Jackson as the hammer and Longstreet as the anvil of the army. In the first part of the Northern Virginia campaign of August 1862, this stereotype held true, but in the climactic battle, it did not. In June, the Federal Government created the 50,000-strong  Despite this criticism, the following day, August 30, was, according to Wert, one of Longstreet's finest performances of the war. After his attacks on the 29th, Pope came to believe with little evidence that Jackson was in retreat. He ordered a reluctant Porter to move his corps forward in pursuit, and they collided with Jackson's men and suffered heavy casualties. The attack exposed the Union left flank, and Longstreet took advantage of this by launching a massive assault on the Union flank with over 25,000 men. For over four hours they "pounded like a giant hammer" with Longstreet actively directing artillery fire and sending brigades into the fray. Longstreet and Lee were together during the assault and both of them came under Union artillery fire. Although the Union troops put up a furious defense, Pope's army was forced to retreat in a manner similar to the embarrassing Union defeat at First Bull Run, fought on roughly the same battleground. Longstreet gave all of the credit for the victory to Lee, describing the campaign as "clever and brilliant". It established a strategic model he believed to be ideal—the use of defensive tactics within a strategic offensive. On September 1, Jackson's corps moved to cut off the Union retreat at the

Despite this criticism, the following day, August 30, was, according to Wert, one of Longstreet's finest performances of the war. After his attacks on the 29th, Pope came to believe with little evidence that Jackson was in retreat. He ordered a reluctant Porter to move his corps forward in pursuit, and they collided with Jackson's men and suffered heavy casualties. The attack exposed the Union left flank, and Longstreet took advantage of this by launching a massive assault on the Union flank with over 25,000 men. For over four hours they "pounded like a giant hammer" with Longstreet actively directing artillery fire and sending brigades into the fray. Longstreet and Lee were together during the assault and both of them came under Union artillery fire. Although the Union troops put up a furious defense, Pope's army was forced to retreat in a manner similar to the embarrassing Union defeat at First Bull Run, fought on roughly the same battleground. Longstreet gave all of the credit for the victory to Lee, describing the campaign as "clever and brilliant". It established a strategic model he believed to be ideal—the use of defensive tactics within a strategic offensive. On September 1, Jackson's corps moved to cut off the Union retreat at the

After a lengthy interlude with little military activity, beginning on October 26, McClellan marched his army across the Potomac River. On November 7, Lincoln replaced McClellan with Burnside. On November 15, Burnside began moving his army south towards

After a lengthy interlude with little military activity, beginning on October 26, McClellan marched his army across the Potomac River. On November 7, Lincoln replaced McClellan with Burnside. On November 15, Burnside began moving his army south towards

Longstreet's actions at the

Longstreet's actions at the

Since his plans for an early morning coordinated attack were now infeasible, Lee instead ordered Longstreet to coordinate a massive assault on the center of the Union line at Cemetery Ridge with his corps. The Union position was held by the

Since his plans for an early morning coordinated attack were now infeasible, Lee instead ordered Longstreet to coordinate a massive assault on the center of the Union line at Cemetery Ridge with his corps. The Union position was held by the

In mid-August 1863, Longstreet once again resumed his attempts to be transferred to the Western Theater. He wrote a private letter to Seddon, requesting that he be transferred to serve under his old friend Joseph Johnston. He followed this up in conversations with his congressional ally Wigfall, who had long considered Longstreet a suitable replacement for Braxton Bragg. Bragg had a poor combat record and was very unpopular with his men and officers. Lee and President Davis agreed to the request on September 5. McLaws, Hood, a brigade from Pickett's division, and Alexander's 26-gun artillery battalion, traveled over 16 railroads on a route through the Carolinas to reach Bragg in northern

In mid-August 1863, Longstreet once again resumed his attempts to be transferred to the Western Theater. He wrote a private letter to Seddon, requesting that he be transferred to serve under his old friend Joseph Johnston. He followed this up in conversations with his congressional ally Wigfall, who had long considered Longstreet a suitable replacement for Braxton Bragg. Bragg had a poor combat record and was very unpopular with his men and officers. Lee and President Davis agreed to the request on September 5. McLaws, Hood, a brigade from Pickett's division, and Alexander's 26-gun artillery battalion, traveled over 16 railroads on a route through the Carolinas to reach Bragg in northern

Bragg relieved or reassigned the generals who had testified against him and retaliated against Longstreet by reducing his command to only those units that he brought with him from Virginia. Bragg resigned himself to the siege in Chattanooga. At about this time, Longstreet learned of the birth of a son, who was named Robert Lee. Grant arrived in Chattanooga on October 23 and took overall command of the new Union

Bragg relieved or reassigned the generals who had testified against him and retaliated against Longstreet by reducing his command to only those units that he brought with him from Virginia. Bragg resigned himself to the siege in Chattanooga. At about this time, Longstreet learned of the birth of a son, who was named Robert Lee. Grant arrived in Chattanooga on October 23 and took overall command of the new Union

In March, Longstreet rejoined the Army of Northern Virginia. Presented by Lee with a plan for a joint offensive by Johnston and Longstreet into Kentucky, Longstreet made the scheme bolder by adding 20,000 men under General Beauregard, who was headquartered in South Carolina. The plan failed to be enacted as it met with disapproval from President Davis and his newly appointed military advisor, Braxton Bragg, and Longstreet remained in Virginia.

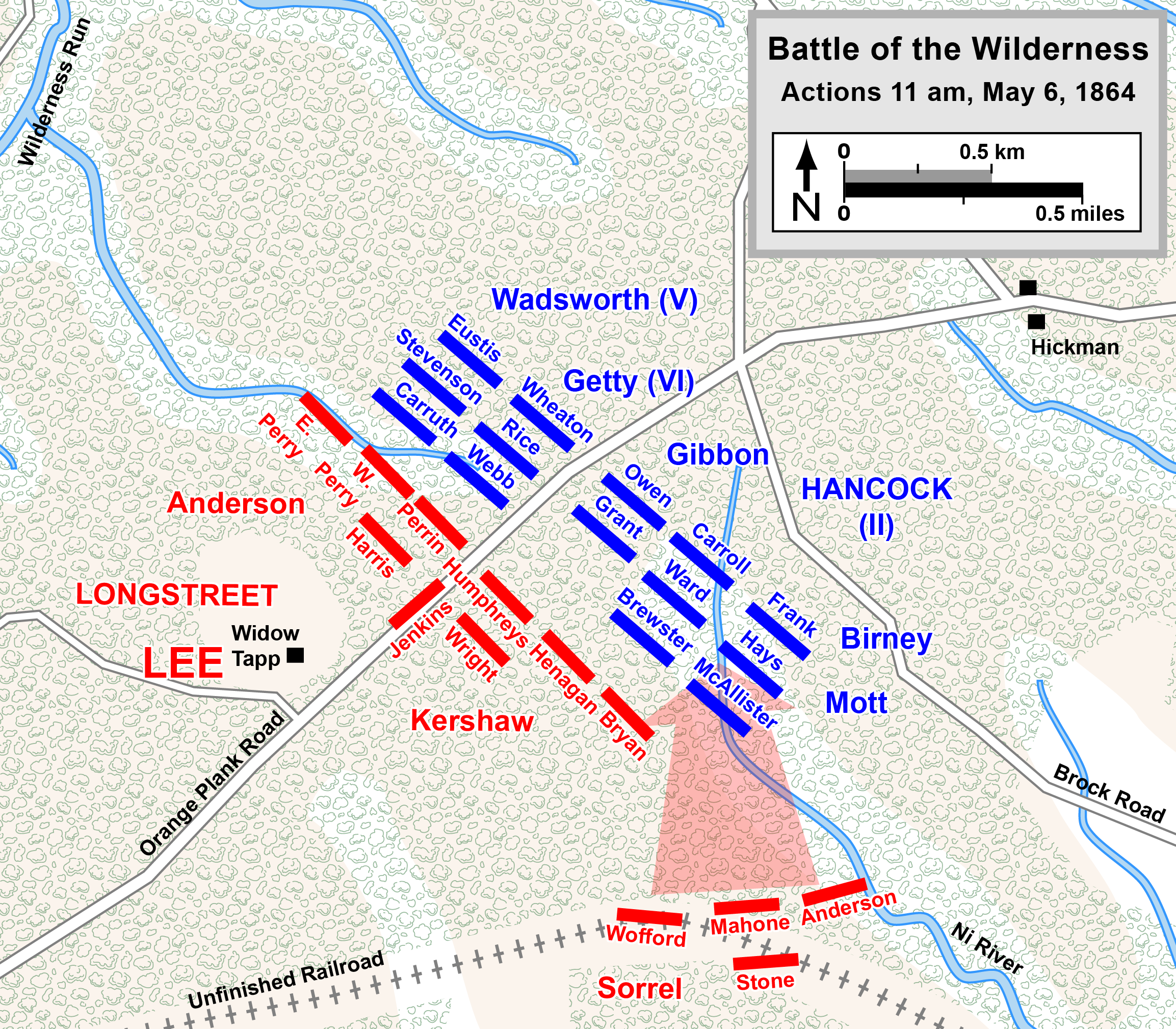

Longstreet discovered that his old friend Ulysses S. Grant had been appointed General-in-Chief of the Union Army, with headquarters in the field alongside the Army of the Potomac. Longstreet told his fellow officers that "he will fight us every day and every hour until the end of the war." Longstreet helped save the Confederate Army from defeat in his first battle back with Lee's army, the

In March, Longstreet rejoined the Army of Northern Virginia. Presented by Lee with a plan for a joint offensive by Johnston and Longstreet into Kentucky, Longstreet made the scheme bolder by adding 20,000 men under General Beauregard, who was headquartered in South Carolina. The plan failed to be enacted as it met with disapproval from President Davis and his newly appointed military advisor, Braxton Bragg, and Longstreet remained in Virginia.

Longstreet discovered that his old friend Ulysses S. Grant had been appointed General-in-Chief of the Union Army, with headquarters in the field alongside the Army of the Potomac. Longstreet told his fellow officers that "he will fight us every day and every hour until the end of the war." Longstreet helped save the Confederate Army from defeat in his first battle back with Lee's army, the

On June 7, 1865, Lee, Longstreet, and other former Confederate officers were indicted by a grand jury in

On June 7, 1865, Lee, Longstreet, and other former Confederate officers were indicted by a grand jury in  In April 1873, Longstreet dispatched a police force under Colonel Theodore W. DeKlyne to the Louisiana town of Colfax to help the local government and its majority-black supporters defend themselves against an insurrection by white supremacists. DeKlyne did not arrive until April 14, one day after the Colfax massacre. By then, his men's task consisted mainly of burying the bodies of blacks who had been killed and attempting to arrest the culprits. During protests of election irregularities in 1874, referred to as the

In April 1873, Longstreet dispatched a police force under Colonel Theodore W. DeKlyne to the Louisiana town of Colfax to help the local government and its majority-black supporters defend themselves against an insurrection by white supremacists. DeKlyne did not arrive until April 14, one day after the Colfax massacre. By then, his men's task consisted mainly of burying the bodies of blacks who had been killed and attempting to arrest the culprits. During protests of election irregularities in 1874, referred to as the

Longstreet applied for various jobs through the

Longstreet applied for various jobs through the

"Southern by the Grace of God but Prussian by Common Sense: James Longstreet and the Exercise of Command in the U.S. Civil War."

''The Journal of Military History'' 66. 4 (2002), pp. 1011–32. Noting Longstreet's delegation of control of battlefield movements to his staff, DiNardo argues that this allowed him to communicate more effectively during battles than the staffs of other Confederate generals. Praise for Longstreet's political conduct after the war in modern times is tempered by the fact that he urged white acceptance of Reconstruction at least in part so that whites, and not blacks, would have the preeminent role in rebuilding the South. Nevertheless, he has been commended for his willingness to work with the North, support for black voting rights, and bravery in leading a partially black militia force to suppress a white supremacist insurrection.

The Longstreet ChroniclesThe Longstreet SocietyOriginal Document: James Longstreet's Signature on The Confederate Surrender at Appomattox, Virginia April 10, 1865Lt. Gen. James Longstreet historical marker

* *

Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library

Emory University

James Longstreet papers, 1850–1904

{{DEFAULTSORT:Longstreet, James 1821 births 1904 deaths 19th-century American diplomats Academy of Richmond County alumni Ambassadors of the United States to the Ottoman Empire American military personnel of the Mexican–American War Army of Northern Virginia Burials in Georgia (U.S. state) Catholics from Louisiana Confederate States Army lieutenant generals Converts to Roman Catholicism from Evangelicalism Georgia (U.S. state) Republicans Louisiana Republicans People from Gainesville, Georgia People from New Orleans People from North Augusta, South Carolina People of Georgia (U.S. state) in the American Civil War American people of English descent American people of Dutch descent United States Army officers United States Military Academy alumni

Confederate generals

The general officers of the Confederate States Army (CSA) were the senior military leaders of the Confederacy during the American Civil War of 1861–1865. They were often former officers from the United States Army (the regular army) prior ...

of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

and the principal subordinate to General Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of Nor ...

, who called him his "Old War Horse". He served under Lee as a corps

Corps (; plural ''corps'' ; from French , from the Latin "body") is a term used for several different kinds of organization. A military innovation by Napoleon I, the formation was first named as such in 1805. The size of a corps varies great ...

commander for most of the battles fought by the Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most oft ...

in the Eastern Theater, and briefly with Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg (March 22, 1817 – September 27, 1876) was an American army officer during the Second Seminole War and Mexican–American War and Confederate general in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War, serving in the Wester ...

in the Army of Tennessee

The Army of Tennessee was the principal Confederate army operating between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River during the American Civil War. It was formed in late 1862 and fought until the end of the war in 1865, participating in ...

in the Western Theater.

After graduating from the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

at West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

, Longstreet served in the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

during the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

. He was wounded in the thigh at the Battle of Chapultepec

The Battle of Chapultepec was a battle between American forces and Mexican forces holding the strategically located Chapultepec Castle just outside Mexico City, fought 13 September 1847 during the Mexican–American War. The building, sitting ...

, and during recovery married his first wife, Louise Garland. Throughout the 1850s, he served on frontier duty in the American Southwest

The Southwestern United States, also known as the American Southwest or simply the Southwest, is a geographic and cultural region of the United States that generally includes Arizona, New Mexico, and adjacent portions of California, Colorado ...

. In June 1861, Longstreet resigned his U.S. Army commission and joined the Confederate Army. He commanded Confederate troops during an early victory at Blackburn's Ford

Blackburn's Ford was the crossing of Bull Run by Centreville Road between Manassas and Centreville, Virginia, in the United States. It was named after the original owner of the Yorkshire Plantation (McLean's Farm), Col. Richard Blackburn, forme ...

in July and played a minor role at the First Battle of Bull Run

The First Battle of Bull Run (the name used by Union forces), also known as the Battle of First Manassas

.

Longstreet made significant contributions to most major Confederate victories, primarily in the Eastern Theater as one of Robert E. Lee's chief subordinates in the Army of Northern Virginia. He performed poorly at Seven Pines by accidentally marching his men down the wrong road, causing them to arrive late, but played an important role in the Confederate success of the Seven Days Battles

The Seven Days Battles were a series of seven battles over seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army of the Potomac, comman ...

in the summer of 1862, where he helped supervise repeated attacks which drove the Union army away from the Confederate capital of Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, Californi ...

. Longstreet led a devastating counterattack that routed the Union army at Second Bull Run in August. His men held their ground in defensive roles at Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union G ...

and Fredericksburg. He did not participate in the Confederate victory at Chancellorsville, as he and most of his soldiers had been detached on the comparatively minor Siege of Suffolk

The siege of Suffolk, also known as the Battle of Suffolk, took place from April 11 to May 4, 1863, near Suffolk, Virginia during the American Civil War.

Background

In 1863 Lieutenant General (CSA), Lt. Gen. James Longstreet was placed in comm ...

. Longstreet's most controversial service was at the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the ...

in July 1863, where he openly disagreed with General Lee on the tactics to be employed and reluctantly supervised several unsuccessful attacks on Union forces. Afterward, Longstreet was, at his own request, sent to the Western Theater to fight under Braxton Bragg, where his troops launched a ferocious assault on the Union lines at Chickamauga Chickamauga may refer to:

Entertainment

* "Chickamauga", an 1889 short story by American author Ambrose Bierce

* "Chickamauga", a 1937 short story by Thomas Wolfe

* "Chickamauga", a song by Uncle Tupelo from their 1993 album ''Anodyne (album), Ano ...

that carried the day. Afterward, his performance in semi-autonomous command during the Knoxville campaign resulted in a Confederate defeat. Longstreet's tenure in the Western Theater was marred by his central role in numerous conflicts amongst Confederate generals. Unhappy serving under Bragg, Longstreet and his men were sent back to Lee. He ably commanded troops during the Battle of the Wilderness

The Battle of the Wilderness was fought on May 5–7, 1864, during the American Civil War. It was the first battle of Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant's 1864 Virginia Overland Campaign against General Robert E. Lee and the Confederate Ar ...

in 1864, where he was seriously wounded by friendly fire. He later returned to the field, serving under Lee in the Siege of Petersburg

The Richmond–Petersburg campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War. Although it is more popularly known as the Siege of Petersburg, it was not a cla ...

and the Appomattox campaign.

Longstreet enjoyed a successful post-war career working for the U.S. government as a diplomat, civil servant, and administrator. His support for the Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

and his cooperation with his old friend, President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

, as well as critical comments he wrote about Lee's wartime performance, made him anathema

Anathema, in common usage, is something or someone detested or shunned. In its other main usage, it is a formal excommunication. The latter meaning, its ecclesiastical sense, is based on New Testament usage. In the Old Testament, anathema was a cr ...

to many of his former Confederate colleagues. His reputation in the South further suffered when he led African-American militia against the anti-Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

White League

The White League, also known as the White Man's League, was a white paramilitary terrorist organization started in the Southern United States in 1874 to intimidate freedmen into not voting and prevent Republican Party political organizing. Its f ...

at the Battle of Liberty Place

The Battle of Liberty Place, or Battle of Canal Street, was an attempted insurrection and coup d'etat by the Crescent City White League against the Reconstruction Era Louisiana Republican state government on September 14, 1874, in New Orleans ...

in 1874. Authors of the Lost Cause

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy (or simply Lost Cause) is an American pseudohistorical negationist mythology that claims the cause of the Confederate States during the American Civil War was just, heroic, and not centered on slavery. Firs ...

movement focused on Longstreet's actions at Gettysburg as a principal reason for why the South lost the Civil War. As an elderly man, he married Helen Dortch Longstreet

Helen Dortch Longstreet (, Dortch; April 20, 1863 – May 3, 1962), known as the "Fighting Lady", was an American social advocate, librarian, and newspaper woman serving as reporter, editor, publisher, and business manager. She was the first woman ...

, a woman several decades younger than him, who after his death worked to restore her husband's image. Since the late 20th century, Longstreet's reputation has undergone a slow reassessment. Many Civil War historians now consider him among the war's most gifted tactical commanders.

Early life

Boyhood

James Longstreet was born on January 8, 1821, in Edgefield District,South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, an area that is now part of North Augusta, Edgefield County

Edgefield County is a county located on the western border of the U.S. state of South Carolina. As of the 2020 census, its population was 25,657. Its county seat and largest municipality is Edgefield. The county was established on March 12, ...

. He was the fifth child and third son of James Longstreet (1783–1833), of Dutch descent, and Mary Ann Dent (1793–1855) of English descent, originally from New Jersey and Maryland respectively, who owned a cotton plantation close to where the village of Gainesville would be founded in northeastern Georgia. James's ancestor Dirck Stoffels Langestraet immigrated to the Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

colony of New Netherland

New Netherland ( nl, Nieuw Nederland; la, Novum Belgium or ) was a 17th-century colonial province of the Dutch Republic that was located on the east coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territories extended from the Delmarva ...

in 1657, but the name became Anglicized

Anglicisation is the process by which a place or person becomes influenced by English culture or British culture, or a process of cultural and/or linguistic change in which something non-English becomes English. It can also refer to the influenc ...

over the generations. James's father was impressed by his son's "rocklike" character on the rural plantation, giving him the nickname Peter, and he was known as Pete or Old Pete for the rest of his life. Longstreet's father decided on a military career for his son but felt that the local education available to him would not be adequate preparation. At the age of nine, James was sent to live with his aunt Frances Eliza and uncle Augustus Baldwin Longstreet

Augustus Baldwin Longstreet (September 22, 1790 – July 9, 1870) was an American lawyer, minister, educator, and humorist, known for his book ''Georgia Scenes''. He was the uncle of the senior Confederate General James Longstreet. He held p ...

in Augusta, Georgia

Augusta ( ), officially Augusta–Richmond County, is a consolidated city-county on the central eastern border of the U.S. state of Georgia. The city lies across the Savannah River from South Carolina at the head of its navigable portion. Geor ...

. James spent eight years on his uncle's plantation, Westover, just outside the city while he attended the Academy of Richmond County

The Academy of Richmond County is a high school located in Augusta, Georgia, United States. Known previously as Richmond County Military Academy, it is commonly known as Richmond Academy or ARC.

Chartered in 1783, it is listed as the sixth old ...

. His father died from a cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium '' Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting an ...

epidemic while visiting Augusta in 1833. Although James's mother and the rest of the family moved to Somerville, Alabama

Somerville is a town in Morgan County, Alabama, Morgan County, Alabama, United States. It is included in the Decatur metropolitan area, Alabama, Decatur Metropolitan Area and the Huntsville-Decatur Combined Statistical Area. As of the 2020 census, ...

, following his father's death, James remained with his uncle.

As a boy, Longstreet enjoyed swimming, hunting, fishing, and riding horses. He became adept at shooting firearms. Northern Georgia was very rural frontier territory during Longstreet's boyhood, and Southern aristocratic traditions had not yet taken hold. As a result, Longstreet's manners were sometimes rather rough in spite of his plantation background. He dressed unceremoniously and at times used coarse language, although not in the presence of women. In his old age, Longstreet described his aunt and uncle as caring and loving. He made no known political statements before the war and appears to have been largely uninterested in politics. But Augustus, as a lawyer, judge, newspaper editor, and Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's ...

minister, was a fierce states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the ...

partisan who supported South Carolina during the Nullification crisis (1828–1833), ideas to which Longstreet probably would have been exposed. Augustus was also known for drinking whiskey and playing card games at a time when many Americans considered them immoral, habits he passed on to Longstreet.

West Point and early military service

In 1837, Augustus attempted to obtain an appointment for his nephew to theUnited States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

, but the vacancy for his congressional district had already been filled. Longstreet was instead appointed the following year by a relative Reuben Chapman

Reuben Chapman (July 15, 1799 – May 17, 1882) was an American lawyer and politician.

Life

Born on July 15, 1799, in Bowling Green, Virginia, he moved to Alabama in 1824, where he established a law practice. He represented Alabama in the U.S ...

, who represented the First District of Alabama, where Mary Longstreet lived. Longstreet was a poor student. By his own admission in his memoirs, he "had more interest in the school of the soldier, horsemanship, exercise, and the outside game of foot-ball than in the academic courses".

Longstreet ranked in the bottom third of every subject during his four years at the academy. In January of his third year, Longstreet initially failed his mechanics exam, but took a second test two days later and passed. Longstreet's engineering instructor in his fourth year was Dennis Hart Mahan

Dennis Hart Mahan (Mă-hăn) əˈhæn(April 2, 1802 – September 16, 1871) was a noted American military theorist, civil engineer and professor at the United States Military Academy at West Point from 1824–1871. He was the father of Amer ...

, a man who stressed swift maneuvering, protection of interior lines, and positioning troops in strategic points rather than attempting to destroy the enemy's army outright. Although Longstreet earned modest grades in the course, he used similar tactics during the Civil War. Longstreet was also a disciplinary problem at West Point. He earned a large number of demerits, especially in his final two years. His offenses included visiting after taps, absence at roll call, an untidy room, long hair, causing a disturbance during study time, and disobeying orders. Biographer Jeffry D. Wert says, "Longstreet was neither a model student nor a gentleman."

Longstreet was popular with his classmates, however, and befriended a number of men who would become prominent during the Civil War, including George Henry Thomas, William Rosecrans

William Starke Rosecrans (September 6, 1819March 11, 1898) was an American inventor, coal-oil company executive, diplomat, politician, and U.S. Army officer. He gained fame for his role as a Union general during the American Civil War. He was ...

(his West Point roommate), John Pope, Daniel Harvey Hill

Lieutenant-General Daniel Harvey Hill (July 12, 1821 – September 24, 1889), commonly known as D. H. Hill, was a senior officer of the Confederate States Army who commanded infantry in the eastern and western theaters of the American Civil ...

, Lafayette McLaws

Lafayette McLaws ( ; January 15, 1821 – July 24, 1897) was a United States Army officer and a Confederate general in the American Civil War. He served at Antietam and Fredericksburg, where Robert E. Lee praised his defense of Marye's Heights, ...

, George Pickett

George Edward Pickett (January 16,Military records cited by Eicher, p. 428, and Warner, p. 239, list January 28. The memorial that marks his gravesite in Hollywood Cemetery lists his birthday as January 25. Thclaims to have accessed the baptism ...

, and Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

. Longstreet ranked 54th out of 56 cadets when he graduated in 1842. He was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army unt ...

in the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

.

After a brief furlough, Longstreet was stationed for two years at the 4th U.S. Infantry

The U.S. 4th Infantry Regiment ("Warriors") is an infantry regiment in the United States Army. It has served the United States for approximately two hundred years.

History

Origins

It has been alleged that the regiment traces its lineage to the ...

at Jefferson Barracks

The Jefferson Barracks Military Post is located on the Mississippi River at Lemay, Missouri, south of St. Louis. It was an important and active U.S. Army installation from 1826 through 1946. It is the oldest operating U.S. military installation ...

, Missouri, under the command of Lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colon ...

John Garland. In 1843, he was joined by his friend, Lieutenant Ulysses Grant. In 1844, Longstreet met Garland's daughter and his future first wife Maria Louisa Garland, called Louise by her family. At about the same time as Longstreet began courting Louise, Grant courted Longstreet's fourth cousin, Julia Dent, and that couple eventually married. Longstreet attended the Grant wedding on August 22, 1848, in St. Louis, but his role at the ceremony remains unclear. Grant biographers Jean Edward Smith and Ron Chernow

Ronald Chernow (; born March 3, 1949) is an American writer, journalist and biographer. He has written bestselling historical non-fiction biographies.

He won the 2011 Pulitzer Prize for Biography and the 2011 American History Book Prize for hi ...

state that Longstreet served as Grant's best man

A groomsman or usher is one of the male attendants to the groom in a wedding ceremony and performs the first speech at the wedding. Usually, the groom selects close friends and relatives to serve as groomsmen, and it is considered an honor to be ...

at the wedding. John Y. Simon, editor of Julia Grant's memoirs, concluded that Longstreet "may have been a groomsman", and Longstreet biographer Donald Brigman Sanger called the role of best man "uncertain" while noting that neither Grant nor Longstreet mentioned such a role in either of their memoirs.

Later in 1844, the regiment, along with the Third Infantry, was transferred to Camp Salubrity near Natchitoches, Louisiana

Natchitoches ( ; french: link=no, Les Natchitoches) is a small city and the parish seat of Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana, United States. Established in 1714 by Louis Juchereau de St. Denis as part of French Louisiana, the community was name ...

, as part of the Army of Observation under Major General Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

. On March 8, 1845, Longstreet received a promotion to second lieutenant, and was transferred to the Eighth Infantry, stationed at Fort Marion

The Castillo de San Marcos ( Spanish for "St. Mark's Castle") is the oldest masonry fort in the continental United States; it is located on the western shore of Matanzas Bay in the city of St. Augustine, Florida.

It was designed by the Spanish ...

in St. Augustine, Florida

St. Augustine ( ; es, San Agustín ) is a city in the Southeastern United States and the county seat of St. Johns County on the Atlantic coast of northeastern Florida. Founded in 1565 by Spanish explorers, it is the oldest continuously inhabi ...

. He served for the month of August on court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

duty in Pensacola

Pensacola () is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle, and the county seat and only incorporated city of Escambia County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 54,312. Pensacola is the principal ci ...

. The regiment was then transferred to Corpus Christi, Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

, where he was reunited with the officers of the Third and Fourth Regiments, including Grant. The men passed the winter by staging plays.

Mexican–American War

Longstreet served with distinction in theMexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

with the 8th U.S. Infantry. He fought under Zachary Taylor as a lieutenant in May 1846 in the battles of Palo Alto

Palo Alto (; Spanish for "tall stick") is a charter city in the northwestern corner of Santa Clara County, California, United States, in the San Francisco Bay Area, named after a coastal redwood tree known as El Palo Alto.

The city was es ...

and Resaca de la Palma. He recounted both of these battles in his memoirs but wrote nothing about his personal role in them. On June 10, Longstreet was given command of Company A of the Eighth Infantry of William J. Worth

William Jenkins Worth (March 1, 1794 – May 7, 1849) was an American officer during the War of 1812, the Second Seminole War, and the Mexican–American War.

Early military career

Worth was commissioned as a first lieutenant in March 1813, s ...

's Second Division. He fought again with Taylor's army at the Battle of Monterrey

In the Battle of Monterrey (September 21–24, 1846) during the Mexican–American War, General Pedro de Ampudia and the Mexican Army of the North was defeated by the Army of Occupation, a force of United States Regulars, Volunteers and ...

in September 1846. During the battle, about 200 Mexican lancer

A lancer was a type of cavalryman who fought with a lance. Lances were used for mounted warfare in Assyria as early as and subsequently by Persia, India, Egypt, China, Greece, and Rome. The weapon was widely used throughout Eurasia during the ...

s drove back a group of American troops. Longstreet, commanding companies A and B, led a counterattack, killing or wounding almost half of the lancers.

On February 23, 1847, he was promoted to the rank of first lieutenant. General-in-Chief Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

ordered Worth's division out of Taylor's army and under his direct command in order to participate in an assault on the Mexican capital of Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley o ...

. Worth's division was sent first to Lobos Island. From there it sailed 180 miles (289.7 km) south to the city of Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

. Worth led Scott's army in its amphibious approach on the city, arriving there on March 9. Scott besieged the city and subjected it to regular bombardments. It surrendered on March 29. The American army then marched north towards the capital. In August, Longstreet served in the Battle of Churubusco

The Battle of Churubusco took place on August 20, 1847, while Santa Anna's army was in retreat from the Battle of Contreras or Battle of Padierna during the Mexican–American War. It was the battle where the San Patricio Battalion, made u ...

, a pivotal battle as the U.S. Army moved closer to capturing Mexico City. The Eighth Infantry was the only force in Worth's division to reach the Mexican earthworks. Longstreet carried the regimental banner under heavy Mexican fire. The troops found themselves stuck in a ditch and could only scale the Mexican defenses by standing on each other. In the fierce hand-to-hand combat that ensued, the Americans prevailed. Longstreet received a brevet promotion to captain for his actions at Churubusco.

He received a brevet promotion to major for Molino del Rey. In the Battle of Chapultepec

The Battle of Chapultepec was a battle between American forces and Mexican forces holding the strategically located Chapultepec Castle just outside Mexico City, fought 13 September 1847 during the Mexican–American War. The building, sitting ...

on September 12, he was wounded in the thigh while charging up the hill with his regimental colors; falling, he handed the flag to his friend, Lt. Pickett, who was able to reach the summit. The capture of the Chapultepec fortress led to the fall of Mexico City. Longstreet recovered in the home of the Escandón family, which treated wounded American soldiers. His wound was slow to heal and he did not leave the home until December. After a brief visit with his family, Longstreet went to Missouri to see Louise.

Subsequent activities

After the war and his recovery from the Chapultepec wound, Longstreet and Louise Garland were officially married on March 8, 1848, and the marriage produced 10 children. Little is known of their courtship or marriage. Longstreet rarely mentions her in his memoirs, and never reveals any personal details. There are no surviving letters between the two. Most anecdotes about their relationship come through the writings of Longstreet's second wife,Helen Dortch Longstreet

Helen Dortch Longstreet (, Dortch; April 20, 1863 – May 3, 1962), known as the "Fighting Lady", was an American social advocate, librarian, and newspaper woman serving as reporter, editor, publisher, and business manager. She was the first woman ...

. Novelist Ben Ames Williams

Ben Ames Williams (March 7, 1889 – February 4, 1953) was an American novelist and writer of short stories; he wrote hundreds of short stories and over 30 novels. Among his novels are ''Come Spring'' (1940), ''Leave Her to Heaven'' (1944) ...

, a descendant of Longstreet, included Longstreet as a minor character in two of his novels. Williams questioned Longstreet's surviving children and grandchildren, and in the novels depicted him as a very devoted family man with an exceptionally happy marriage.

Longstreet's next assignment placed him on recruiting duty in Poughkeepsie, New York

Poughkeepsie ( ), officially the City of Poughkeepsie, separate from the Town of Poughkeepsie around it) is a city in the U.S. state of New York. It is the county seat of Dutchess County, with a 2020 census population of 31,577. Poughkeeps ...

, where he served for several months. After travelling to St. Louis for the Grant wedding, Longstreet and his wife moved to Carlisle Barracks

Carlisle Barracks is a United States Army facility located in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. The site of the U.S. Army War College, it is the nation's second-oldest active military base. The first structures were built in 1757, during the French and I ...

, Pennsylvania. On January 1, 1850, he was appointed Chief Commissary for the Department of Texas, responsible for the acquisition and distribution of food to the soldiers and animals of the department. The job was complex and consisted mainly of paperwork, although it provided experience in administrative military work. In June, Longstreet, hoping to find promotion and an income above his $40-per month salary to support his growing family, requested a transfer to the cavalry. His request was rejected. He resigned as commissary in March 1851 and returned to the Eighth Infantry. Longstreet served on frontier duty in Texas at Fort Martin Scott

Fort Martin Scott is a restored United States Army outpost near Fredericksburg in the Texas Hill Country, United States, that was active from December 5, 1848, until April, 1853. It was part of a line of frontier forts established to protect trave ...

near Fredericksburg. The primary purpose of the military in Texas was to protect frontier communities against Indians, and Longstreet frequently participated in scouting missions against the Comanche

The Comanche or Nʉmʉnʉʉ ( com, Nʉmʉnʉʉ, "the people") are a Native American tribe from the Southern Plains of the present-day United States. Comanche people today belong to the federally recognized Comanche Nation, headquartered in ...

. His family remained in San Antonio

("Cradle of Freedom")

, image_map =

, mapsize = 220px

, map_caption = Interactive map of San Antonio

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = United States

, subdivision_type1= State

, subdivision_name1 = Texas

, subdivision_ ...

, and he saw them regularly. In 1854, he was transferred to Fort Bliss

Fort Bliss is a United States Army post in New Mexico and Texas, with its headquarters in El Paso, Texas. Named in honor of William Wallace Smith Bliss, LTC William Bliss (1815–1853), a mathematics professor who was the son-in-law of President ...

in El Paso, and Louise and the children moved in with him. In 1855, Longstreet was involved in fighting against the Mescalero. He assumed command of the garrison at Fort Bliss on two occasions between the spring of 1856 and the spring of 1858. The small size of the garrison allowed for easy socialization with the local people, and the fort's location allowed for visits with Louise's parents in Santa Fe. Longstreet performed scouting missions.

On March 29, 1858, Longstreet wrote to the adjutant general's office in Washington, D.C. requesting that he be assigned to recruiting duty in the East, which would allow him to better educate his children. He was granted a six-month leave, but the request for assignment in the East was denied, and he was instead directed to serve as major and paymaster for the 8th Infantry in Leavenworth, Kansas

Leavenworth () is the county seat and largest city of Leavenworth County, Kansas, United States and is part of the Kansas City metropolitan area. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 37,351. It is located on the west bank of t ...

. He left his son Garland in a school at Yonkers, New York

Yonkers () is a city in Westchester County, New York, United States. Developed along the Hudson River, it is the third most populous city in the state of New York, after New York City and Buffalo. The population of Yonkers was 211,569 as en ...

, before journeying to Kansas. On the way, Longstreet came across his old friend Grant in St. Louis, Missouri. Longstreet's time in Leavenworth lasted about a year until he was transferred to Colonel Garland's department in Albuquerque, New Mexico

Albuquerque ( ; ), ; kee, Arawageeki; tow, Vakêêke; zun, Alo:ke:k'ya; apj, Gołgéeki'yé. abbreviated ABQ, is the most populous city in the U.S. state of New Mexico. Its nicknames, The Duke City and Burque, both reference its founding i ...

, to serve as paymaster, where he was joined by Louise and their children.

Knowledge of Longstreet's prewar life is extremely limited. His experience resembles that of many Civil War generals insofar as he went to West Point, served with distinction in the War with Mexico, and continued his career in the peacetime army of the 1850s. But beyond that, there are few details. He left no diary, and his lengthy memoirs focus almost entirely on recounting and defending his Civil War military record. They reveal little of his personal side while providing only a very cursory view of his pre-war activities. Not only that, but an 1889 fire destroyed his personal papers, making it so that the number of " isting antebellum private letters written by Longstreet ouldbe counted on one hand".

American Civil War

Joining the Confederacy and initial hostilities

At the beginning of theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, Longstreet was paymaster for the United States Army and stationed in Albuquerque, having not yet resigned his commission. After news of the Battle of Fort Sumter

The Battle of Fort Sumter (April 12–13, 1861) was the bombardment of Fort Sumter near Charleston, South Carolina by the South Carolina militia. It ended with the surrender by the United States Army, beginning the American Civil War.

Fol ...

, he joined his fellow Southerners in leaving the post. In his memoirs, Longstreet calls it a "sad day", and records that a number of Northern officers attempted to persuade him not to go. He writes that he asked one of them "what course he would pursue if his State should pass ordinances of secession and call him to its defence. He confessed that he would obey the call."

Longstreet was not enthusiastic about secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics l ...

from the Union, but he had long been infused with the concept of states' rights and felt he could not go against his homeland. Although he was born in South Carolina and brought up in Georgia, he offered his services to the state of Alabama, which had appointed him to West Point and where his mother still lived. He was the senior West Point graduate from that state, which meant that he could potentially be placed in command of that state's soldiers. After settling his accounts, he submitted his resignation letter from the United States Army on May 9, 1861, intending to join the Confederacy. He had already accepted a commission as a lieutenant colonel in the Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

on May 1, before submitting his resignation from the United States Army. His resignation from the United States Army was accepted on June 1.

Longstreet arrived in

Longstreet arrived in Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

, with his new commission. He met with Confederate President

The president of the Confederate States was the head of state and head of government of the Confederate States. The president was the chief executive of the federal government and was the commander-in-chief of the Confederate Army and the Confed ...

Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as ...

at the executive mansion on June 22, 1861, where he was informed that he had been appointed a brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

with the date of rank on June 17, a commission he accepted on June 25. He was ordered to report to Brigadier General P. G. T. Beauregard at Manassas, where he was given command of a brigade of three Virginia regiments—the 1st

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and reco ...

, 11th, and 17th Virginia Infantry regiments in the Confederate Army of the Potomac

The Confederate Army of the Potomac, whose name was short-lived, was under the command of Brig. Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard in the early days of the American Civil War. Its only major combat action was the First Battle of Bull Run. Afterwards, the ...

.

Longstreet assembled his staff and trained his brigade incessantly. On July 16, Union Brigadier General Irvin McDowell

Irvin McDowell (October 15, 1818 – May 4, 1885) was a career American army officer. He is best known for his defeat in the First Battle of Bull Run, the first large-scale battle of the American Civil War. In 1862, he was given command ...

began marching his army toward Manassas Junction. Longstreet's brigade first saw action at Blackburn's Ford

Blackburn's Ford was the crossing of Bull Run by Centreville Road between Manassas and Centreville, Virginia, in the United States. It was named after the original owner of the Yorkshire Plantation (McLean's Farm), Col. Richard Blackburn, forme ...

on July 18, when it collided with McDowell's advance division under Brigadier General Daniel Tyler, clashing heavily with the brigade of Israel B. Richardson

Israel Bush Richardson (December 26, 1815 – November 3, 1862) was a United States Army officer during the Mexican–American War and American Civil War, where he was a major general in the Union Army. Nicknamed "Fighting Dick" for his prowess o ...

. An infantry charge pushed Longstreet's men back, and in his own words Longstreet "rode with sabre

A sabre (French: �sabʁ or saber in American English) is a type of backsword with a curved blade associated with the light cavalry of the early modern and Napoleonic periods. Originally associated with Central European cavalry such as t ...

in hand for the leading files, determined to give them all that was in the sword and my horse's heels, or stop the break". Colonel Jubal Early

Jubal Anderson Early (November 3, 1816 – March 2, 1894) was a Virginia lawyer and politician who became a Confederate States of America, Confederate general during the American Civil War. Trained at the United States Military Academy, Early r ...

's brigade arrived to reinforce Longstreet. One of Early's regiments, the 7th Virginia, fired a volley while Longstreet was still in front of its position, forcing him to dive off of his horse and onto the ground. Under the renewed Confederate strength, the Union left wavered. Tyler withdrew, as he had orders not to bring on a general engagement.

The battle preceded the First Battle of Bull Run

The First Battle of Bull Run (the name used by Union forces), also known as the Battle of First Manassas

(First Manassas). When the main attack came at the opposite end of the line on July 21, Longstreet's brigade endured artillery fire for nine hours but played a minor role in the fighting. Between 5 and 6 in the evening, Longstreet received an order from Brigadier General Joseph E. Johnston instructing him to take part in the pursuit of the Federal troops, who had been defeated and were fleeing the battlefield. He obeyed, but when he met Brigadier General Milledge Bonham's brigade, Bonham, who outranked Longstreet, ordered him to retreat. An order soon arrived from Johnston ordering the same. Longstreet was infuriated that his commanders would not allow a vigorous pursuit of the defeated Union Army. His Chief of Staff, Moxley Sorrel

Gilbert Moxley Sorrel (February 23, 1838 – August 10, 1901) was a staff officer and Brigadier General in the Provisional Army of the Confederate States.

Early life

Sorrel was born in Savannah, Georgia, the son of one of the wealthiest men in ...

, recorded that he was "in a fine rage. He dashed his hat furiously to the ground, stamped, and bitter words escaped him." He quoted Longstreet as saying afterward, "Retreat! Hell, the Federal army has broken to pieces."

On October 7, Longstreet was promoted to major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

and assumed command of a division in the newly reorganized and renamed Confederate Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most oft ...

under Johnston (formed from the previous Army of the Potomac and the Army of the Shenandoah) – with four infantry brigades commanded by Generals D.H. Hill, David R. Jones, Bonham, and Louis Wigfall

Louis Trezevant Wigfall (April 21, 1816 – February 18, 1874) was an American politician who served as a Confederate States Senator from Texas from 1862 to 1865. He was among a group of leading secessionists known as Fire-Eaters, advocati ...

, as well as Hampton's Legion

Hampton's Legion was an American Civil War military unit of the Confederate States of America, organized and partially financed by wealthy South Carolina planter Wade Hampton III. Initially composed of infantry, cavalry, and artillery battali ...

commanded by Wade Hampton III

Wade Hampton III (March 28, 1818April 11, 1902) was an American military officer who served the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War and later a politician from South Carolina. He came from a wealthy planter family, and ...

.

Family tragedy

On January 10, 1862, Longstreet traveled under orders from Johnston to Richmond, where he discussed with Davis the creation of a draft or conscription program. He spent much of the intervening time with Louise and their children, and was back at army headquarters in Centreville by January 20. After only a day or two, he received a telegram informing him that all four of his children were extremely sick in an outbreak ofscarlet fever

Scarlet fever, also known as Scarlatina, is an infectious disease caused by '' Streptococcus pyogenes'' a Group A streptococcus (GAS). The infection is a type of Group A streptococcal infection (Group A strep). It most commonly affects chi ...

. Longstreet immediately returned to the city.

Longstreet arrived in Richmond before the death of his one-year-old daughter Mary Anne on January 25. Four-year-old James died the following day. Eleven-year-old Augustus Baldwin ("Gus") died on February 1. His 13-year-old son Garland remained ill but appeared to be out of mortal danger. George Pickett and his future wife LaSalle Corbell were in the Longstreets' company throughout the affair. They arranged the funeral and burials, which for unknown reasons neither Longstreet nor his wife attended. Longstreet waited a very short time to return to the army, doing so on February 5. He rushed back to Richmond later in the month when Garland took a turn for the worse, but came back after he recovered. The losses were devastating for Longstreet and he became withdrawn, both personally and socially. In 1861, his headquarters were noted for parties, drinking, and poker games. After he returned, the headquarters social life became for a time more somber. He rarely drank, and his religious devotion increased.

Peninsula

That spring, UnionMajor General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

, commander of the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confede ...

, launched the Peninsula campaign intending to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond. In his memoirs, Longstreet would write that while in temporary command of the Confederate army, he wrote to Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson proposing that he march to Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridg ...

and combine forces. No evidence has emerged for this claim.

Following the delay of the Union offensive against Richmond at the Siege of Yorktown

The Siege of Yorktown, also known as the Battle of Yorktown, the surrender at Yorktown, or the German battle (from the presence of Germans in all three armies), beginning on September 28, 1781, and ending on October 19, 1781, at Yorktown, Virg ...

, Johnston oversaw a tactical withdrawal to the outskirts of Richmond, where defenses had already been prepared. Longstreet's division formed the rearguard, which was heavily engaged at the Battle of Williamsburg

The Battle of Williamsburg, also known as the Battle of Fort Magruder, took place on May 5, 1862, in York County, James City County, and Williamsburg, Virginia, as part of the Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War. It was the first p ...

on May 5. There, Union troops beginning with Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was an American Civil War general for the Union, chiefly remembered for his decisive defeat by Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863.

Hooker had serv ...

's division of the Union III Corps 3rd Corps, Third Corps, III Corps, or 3rd Army Corps may refer to:

France

* 3rd Army Corps (France)

* III Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* III Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of t ...

, which was commanded by Samuel P. Heintzelman

Samuel Peter Heintzelman (September 30, 1805 – May 1, 1880) was a United States Army general. He served in the Seminole War, the Mexican–American War, the Yuma War and the Cortina Troubles. During the American Civil War he was a prominent fig ...

, came out of a forest into open ground to attack Longstreet's men. To protect the army's supply wagons, Longstreet launched a counterattack with the brigades of Cadmus M. Wilcox

Cadmus Marcellus Wilcox (May 20, 1824 – December 2, 1890) was a career United States Army officer who served in the Mexican–American War and also was a Confederate general during the American Civil War.

Early life and career

Wilcox was ...

, A. P. Hill, Pickett, Raleigh E. Colston

Raleigh Edward Colston (October 1, 1825 – July 29, 1896) was a France, French-born United States, American professor, soldier, cartographer, and writer. He was a controversial Brigadier General (CSA), brigadier general in the Confederate S ...

, and two other regiments. The assault drove the Union soldiers back. Finding the ground he occupied untenable, Longstreet requested reinforcements from D.H. Hill's division a little further up the road and received Early's brigade, to which was later added the entire division. Early then launched a fruitless and bloody attack well after the wagons had already been safely evacuated. Overall, the battle was a success, protecting the passage of Confederate supply wagons and delaying the advance of McClellan's army toward Richmond. The affair gave the Confederates possession of four cannon. McClellan inaccurately characterized the battle as a Union victory in a dispatch to Washington.

On May 31, during the

On May 31, during the Battle of Seven Pines

The Battle of Seven Pines, also known as the Battle of Fair Oaks or Fair Oaks Station, took place on May 31 and June 1, 1862, in Henrico County, Virginia, nearby Sandston, as part of the Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War. It was th ...

, Longstreet received his orders verbally from Johnston but apparently misremembered them. He marched his men in the wrong direction down the wrong road, causing congestion and confusion with other Confederate units, diluting the effect of the Confederate counterattack against McClellan. He then got into an argument with Major General Benjamin Huger over who had seniority, causing a significant delay. When D.H. Hill subsequently asked Longstreet for reinforcements, he complied, but failed to properly coordinate his brigades. Only one of Longstreet's brigades and none of Huger's reached the field. Late in the day, Major General Edwin Vose Sumner crossed the rain-swollen Chickahominy River

The Chickahominy is an U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed April 1, 2011 river in the eastern portion of the U.S. state of Virginia. The river, which serves as the eastern bo ...

with two divisions. General Johnston was wounded during the battle. Although Johnston preferred Longstreet as his replacement, command of the Army of Northern Virginia shifted to G. W. Smith

Gustavus Woodson Smith (November 30, 1821 – June 24, 1896), more commonly known as G.W. Smith, was a career United States Army officer who fought in the Mexican–American War, a civil engineer, and a major general in the Confederate St ...

, the senior major general, for a single day. On June 1, Richardson's division of Sumner's corps engaged Longstreet's men, routing Lewis Armistead

Lewis Addison Armistead (February 18, 1817 – July 5, 1863) was a career United States Army officer who became a brigadier general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. On July 3, 1863, as part of Pickett's Charge during ...

's brigade, but the brigades of Pickett, William Mahone

William Mahone (December 1, 1826October 8, 1895) was an American civil engineer, railroad executive, Confederate States Army general, and Virginia politician.

As a young man, Mahone was prominent in the building of Virginia's roads and railroa ...

, and Roger Atkinson Pryor

Roger Atkinson Pryor (July 19, 1828 – March 14, 1919) was a Virginian newspaper editor and politician who became known for his fiery oratory in favor of secession; he was elected both to national and Confederate office, and served as a gen ...

positioned in the woods managed to hold it back. After six hours of fighting, the battle ended in a draw. Johnston praised Longstreet's performance in the battle. Biographer William Garrett Piston marks it as "the lowest point in Longstreet's military career". Longstreet's report unfairly blamed Huger for the mishaps. On June 1, the President's military advisor Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of Nor ...

assumed command of the Army of Northern Virginia. In his memoirs, Longstreet suggested that he initially doubted Lee's capacity for command. He wrote that his arrival "was far from reconciling the troops to the loss of our beloved chief, Joseph E. Johnston". He wrote that Lee did not have much of a reputation at the time that he took command and that there were, therefore "misgivings" about Lee's "power and skill for field service".

In late June, Lee organized a plan to drive McClellan's army away from the capital, which culminated in what became known as the Seven Days Battles

The Seven Days Battles were a series of seven battles over seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army of the Potomac, comman ...

. At daybreak on June 27 at Gaines's Mill, the Confederate Army attacked the V Corps 5th Corps, Fifth Corps, or V Corps may refer to:

France

* 5th Army Corps (France)

* V Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* V Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army ...

of the Union Army under Brigadier General Fitz John Porter, which was positioned north of the Chickahominy River on McClellan's right flank. Federal troops held their lines for most of the day against attacks from the divisions of A.P. Hill and D.H. Hill, and Jackson did not arrive until the afternoon. At about 5 P.M., Longstreet received orders from Lee to join the battle. Longstreet's fresh brigades under Pickett and Richard H. Anderson, accompanied by the brigades of Brigadier General John Bell Hood

John Bell Hood (June 1 or June 29, 1831 – August 30, 1879) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War. Although brave, Hood's impetuosity led to high losses among his troops as he moved up in rank. Bruce Catton wrote that "the de ...

and Colonel Evander M. Law

Evander McIver Law (August 7, 1836 – October 31, 1920) was an author, teacher, and a Confederate general in the American Civil War.

Early life

Law was born in Darlington, South Carolina. His grandfather and his two great-grandfathers had f ...

from William H.C. Whiting

William Henry Chase Whiting (March 22, 1824 – March 10, 1865) was a United States Army officer who resigned after 16 years of service in the Army Corps of Engineers to serve in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. He ...

's division, charged the Union lines, forcing them to retreat across the Chickahominy. Longstreet was engaged again on June 30 with about 20,000 men at Glendale Glendale is the anglicised version of the Gaelic Gleann Dail, which means ''valley of fertile, low-lying arable land''.

It may refer to:

Places Australia

*Glendale, New South Wales

** Stockland Glendale, a shopping centre

* Glendale, Queensland, ...

. He departed from his usual strategy of placing troops several lines deep and instead spread them out, which in the opinion of some military historians cost him the battle. His efforts were further damaged by the slowness of other Confederate commanders, and McClellan was able to withdraw his army to the high plateau of Malvern Hill. Jackson, engaged at White Oak Swamp, ignored reports of ways in which to cross the swamp, and refused to answer an inquiry from Longstreet's staff officer John Fairfax. Huger's advance was slow enough to allow Federal troops to be transported away from guarding him and towards Longstreet, and Theophilus Holmes also performed poorly. Nearly 50,000 Confederate troops stood within a few miles of the field at Glendale and rendered little to no assistance. In a reconnaissance on the evening of June 30, Longstreet reported to Lee that conditions were favorable enough to justify assault. At the Battle of Malvern Hill

The Battle of Malvern Hill, also known as the Battle of Poindexter's Farm, was fought on July 1, 1862, between the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, led by Gen. Robert E. Lee, and the Union Army of the Potomac under Maj. Gen. George B. M ...

the next day, Longstreet surrendered A.P. Hill's entire division to Magruder, and marched his remaining troops toward the Union positions on the Confederate extreme right. His men were exposed to fire on their flanks from McClellan's troops and were forced to withdraw without success.

Throughout the Seven Days Battles, Longstreet had operational command of nearly half of Lee's army—15 brigades—as it drove McClellan back down the Peninsula. Longstreet performed aggressively and quite well in his new, larger command, particularly at Gaines's Mill and Glendale. Lee's army suffered from poor maps, organizational flaws, and weak performances by Longstreet's peers, including, uncharacteristically, Stonewall Jackson, and was unable to destroy the Union army. Moxley Sorrel wrote of Longstreet's confidence and calmness in battle: "He was like a rock in steadiness when sometimes in battle the world seemed flying to pieces." General Lee said shortly after Seven Days, "Longstreet was the staff in my right hand." He had been established as Lee's principal lieutenant. Lee reorganized the Army of Northern Virginia after Seven Days, increasing Longstreet's command from six brigades to 28. Longstreet took command of the Right Wing (later to become known as the First Corps) and Jackson was given command of the Left Wing. Over time, Lee and Longstreet became good friends and set up headquarters very near each other. Despite sharing with Jackson a belief in temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

* Temperance (group), Canadian dan ...

as well as a deep religious conviction, Lee never developed as strong a friendship with him. Piston speculates that the more relaxed atmosphere of Longstreet's headquarters, which included gambling and drinking, allowed Lee to relax and take his mind off the war, and reminded him of his happier younger days.

After the campaign, an editorial appeared in the ''Richmond Examiner

The ''Richmond Examiner'', a newspaper which was published before and during the American Civil War under the masthead of ''Daily Richmond Examiner'', was one of the newspapers published in the Confederate capital of Richmond. Its editors view ...

'' inaccurately claiming that the Battle of Glendale "was fought exclusively by General A.P. Hill and the forces under his command". Longstreet then drafted a letter refuting the article, which was published in the ''Richmond Whig.'' Hill took offense and requested that his division be transferred out of Longstreet's command. Longstreet agreed, but Lee took no action. Then, Hill refused to accede to Longstreet's repeated requests for information and was eventually arrested on Longstreet's orders. He challenged Longstreet to a duel. Longstreet accepted, but Lee intervened and transferred Hill's division out of Longstreet's command and into Jackson's.

Second Bull Run

The military reputations of Lee's corps commanders are often characterized as Stonewall Jackson representing the audacious, offensive component of Lee's army, with Longstreet more typically advocating and executing strong defensive strategies and tactics. Wert describes Jackson as the hammer and Longstreet as the anvil of the army. In the first part of the Northern Virginia campaign of August 1862, this stereotype held true, but in the climactic battle, it did not. In June, the Federal Government created the 50,000-strong

The military reputations of Lee's corps commanders are often characterized as Stonewall Jackson representing the audacious, offensive component of Lee's army, with Longstreet more typically advocating and executing strong defensive strategies and tactics. Wert describes Jackson as the hammer and Longstreet as the anvil of the army. In the first part of the Northern Virginia campaign of August 1862, this stereotype held true, but in the climactic battle, it did not. In June, the Federal Government created the 50,000-strong Army of Virginia

The Army of Virginia was organized as a major unit of the Union Army and operated briefly and unsuccessfully in 1862 in the American Civil War. It should not be confused with its principal opponent, the Confederate Army of ''Northern'' Virginia ...

, and put Major General John Pope in command. Pope moved south in an attempt to attack Lee and threaten Richmond through an overland march. Lee left Longstreet near Richmond to guard the city and dispatched Jackson to hinder Pope's advance. Jackson won a major victory at the Battle of Cedar Mountain