Gavril Myasnikov on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

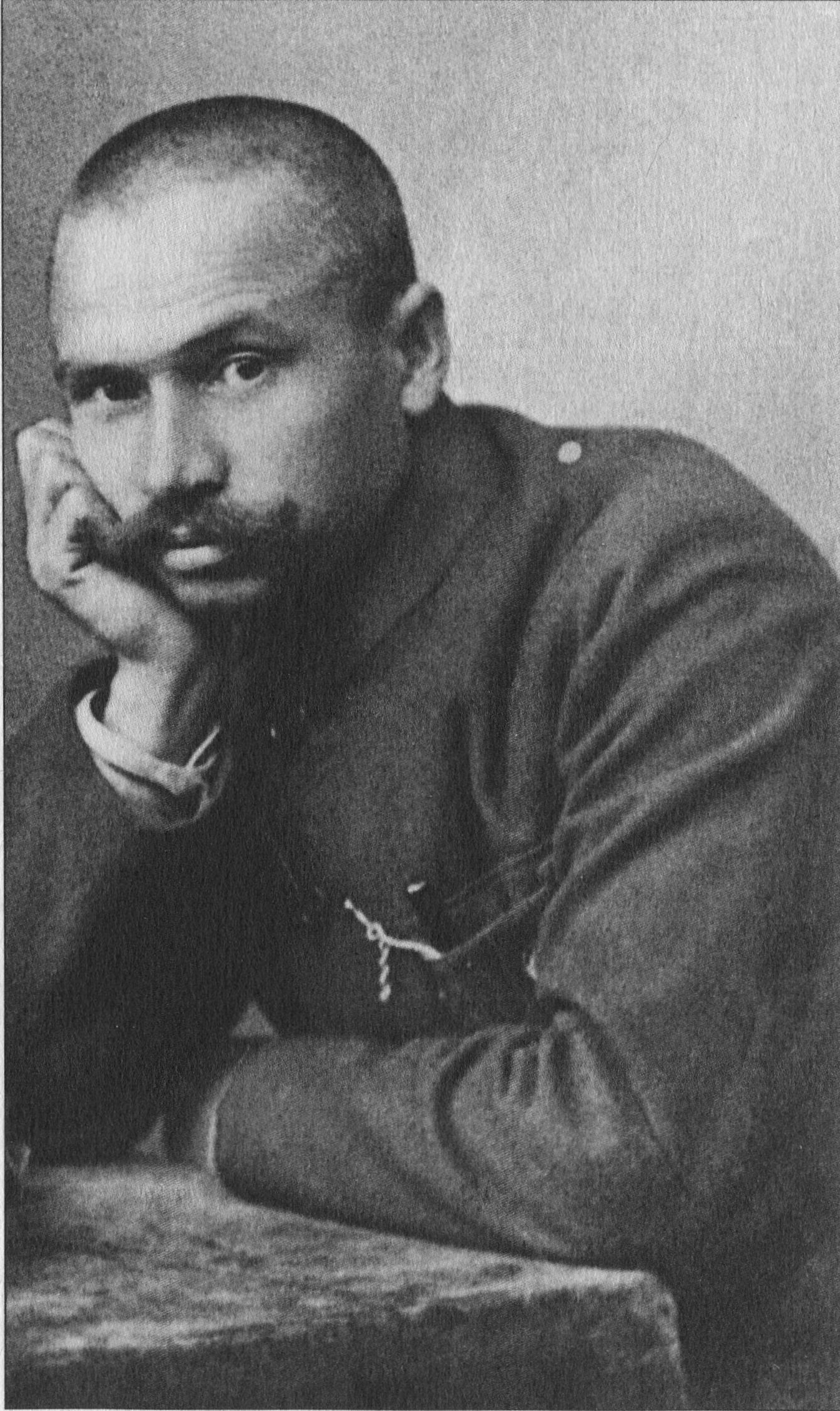

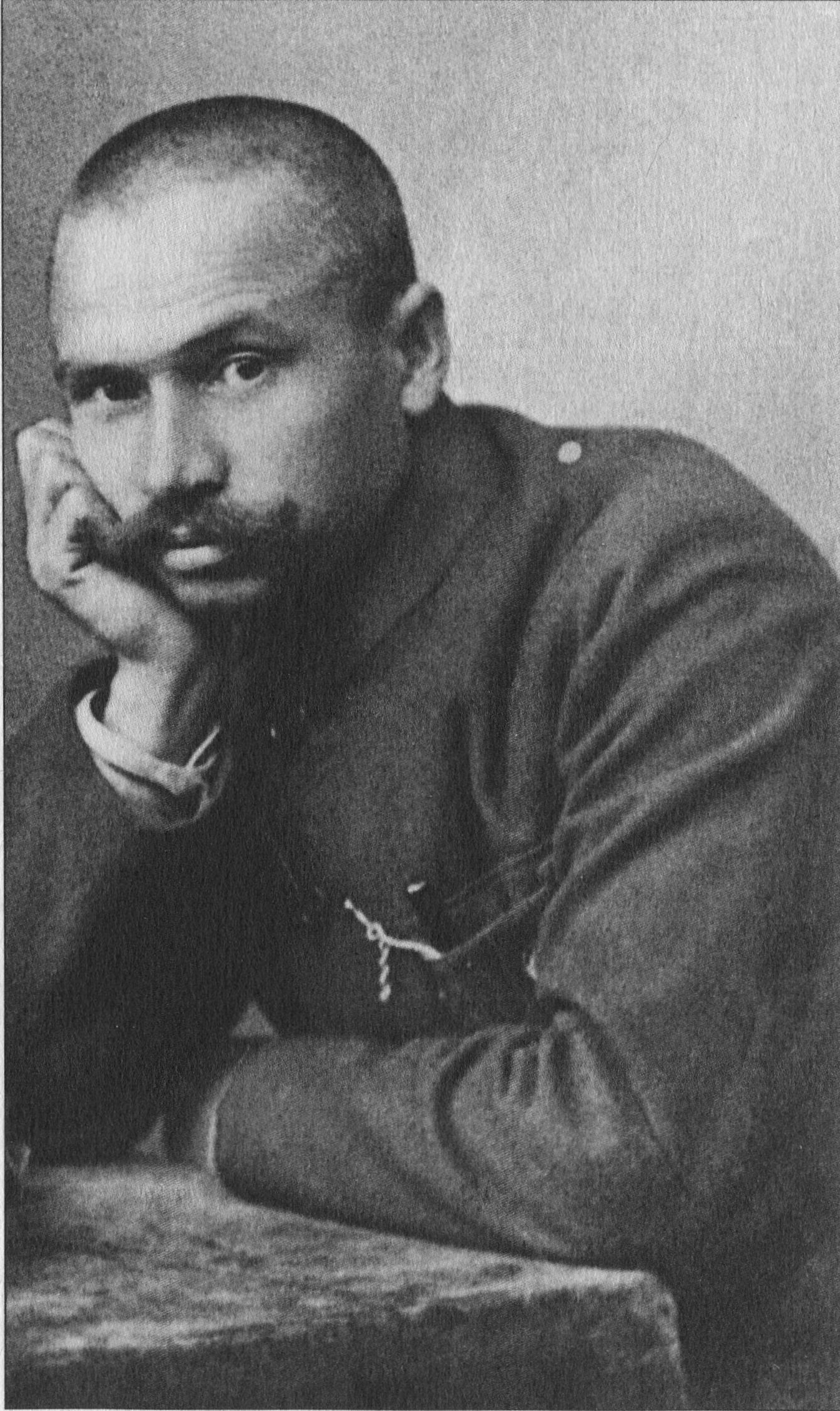

Gavril Ilyich Myasnikov (russian: Гавриил Ильич Мясников; February 25, 1889,

Gavril Ilyich Myasnikov (russian: Гавриил Ильич Мясников; February 25, 1889,

Born in to a working-class family, Gabriel Myasnikov left school at 11, to start work as a mechanic in the Motovilikha arms factory, in the

Born in to a working-class family, Gabriel Myasnikov left school at 11, to start work as a mechanic in the Motovilikha arms factory, in the

Archivists rehabilitate G. I. Myasnikov. Permian State Archive of Social-Political History (in Russian)

/ref>

'' Russian Review'', vol. 43 (1984): 1-29. *Miasnikov, G. "Filosofiia ubiistva, ili pochemu i kak ia ubil Mikhaila Romanova." ''Minuvshee'', 18 (1995): 7–191. *Alikina, Nadezhda Alekseevna. ''Don Kikhot proletarskoi revoliutsii''. Perm: Izdatel'stvo Pushka, 2006. *

Gabriel Miasnikov Archive

at

Gabriel Miasnikov, ''The same, only in a different way''

(1920)

Gabriel Miasnikov, ''The latest deception''

(1930)

''Gavril Myasnikov: hero of the working class''

Communist League Tampa, 2015. {{DEFAULTSORT:Myasnikov, Gavril 1889 births 1945 deaths People from Chistopolsky Uyezd Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members Old Bolsheviks Left communists All-Russian Central Executive Committee members Russian murderers Regicides of Nicholas II Murder of the Romanov family People of the Russian Civil War Russian people executed by the Soviet Union Executed Soviet people from Russia

Gavril Ilyich Myasnikov (russian: Гавриил Ильич Мясников; February 25, 1889,

Gavril Ilyich Myasnikov (russian: Гавриил Ильич Мясников; February 25, 1889, Chistopol

Chistopol (russian: Чи́стополь; tt-Cyrl, Чистай, ''Çistay''; cv, Чистай, ''Çistay'') is a town in Tatarstan, Russia, located on the left bank of the Kuybyshev Reservoir, on the Kama River. As of the 2010 Census, its p ...

, Kazan Governorate

The Kazan Governorate (russian: Каза́нская губе́рния; tt-Cyrl, Казан губернасы; cv, Хусан кӗперниӗ; mhr, Озаҥ губерний), or the Government of Kazan, was a governorate (a ''guberniya'') o ...

– November 16, 1945, Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

), also transliterated as Gavriil Il'ich Miasnikov, was a Russian communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

revolutionary

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective, to refer to something that has a major, sudden impact on society or on some aspect of human endeavor.

...

, a metalworker from the Urals

The Ural Mountains ( ; rus, Ура́льские го́ры, r=Uralskiye gory, p=ʊˈralʲskʲɪjə ˈɡorɨ; ba, Урал тауҙары) or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through European ...

, and one of the first Bolsheviks to oppose and criticise the communist dictatorship .

Political career

Born in to a working-class family, Gabriel Myasnikov left school at 11, to start work as a mechanic in the Motovilikha arms factory, in the

Born in to a working-class family, Gabriel Myasnikov left school at 11, to start work as a mechanic in the Motovilikha arms factory, in the Perm

Perm or PERM may refer to:

Places

*Perm, Russia, a city in Russia

**Permsky District, the district

**Perm Krai, a federal subject of Russia since 2005

**Perm Oblast, a former federal subject of Russia 1938–2005

**Perm Governorate, an administrat ...

region. During the 1905 Revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

, he joined the Socialist Revolutionary Party

The Socialist Revolutionary Party, or the Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries (the SRs, , or Esers, russian: эсеры, translit=esery, label=none; russian: Партия социалистов-революционеров, ), was a major politi ...

and was involved in expropriating weapons, and ran combat unit. He joined the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

in 1906. He was arrested that same year and exiled to Eastern Siberia, but escaped in June 1908. He was arrested again in 1909 and 1911, but escaped each time. Arrested for the fourth time, in Baku

Baku (, ; az, Bakı ) is the capital and largest city of Azerbaijan, as well as the largest city on the Caspian Sea and of the Caucasus region. Baku is located below sea level, which makes it the lowest lying national capital in the world a ...

in 1913, he spent four years in Oryol Prison

The Oryol Prison has been a prison in Oryol since the 19th century. It was a notable place of incarceration for political prisoners and war prisoners of the Second World War.

The building of prison, built in 1840, is one of the oldest buildings ...

. He was released during the February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and somet ...

and returned to Motovilikha, where he was elected chairman of the local soviet of workers' and peasant's deputies.

Myasnikov supervised the execution of Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich of Russia

Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich of Russia (russian: Михаи́л Алекса́ндрович, r=Mikhail Aleksandrovich; 13 June 1918) was the youngest son and fifth child of Emperor Alexander III of Russia and youngest brother of Nicholas ...

, younger brother of the deposed Tsar Nicholas II (1918). As the representative of the Perm Soviet, he attended a special session of the Ural Soviet on 29 June 1918 under the chairmanship of his close comrade Alexander Beloborodov, where it was unanimously decided by those present that the former Tsar and his family be shot. When Myasnikov left Yekaterinburg ahead of the advance of the White Army

The White Army (russian: Белая армия, Belaya armiya) or White Guard (russian: Бѣлая гвардія/Белая гвардия, Belaya gvardiya, label=none), also referred to as the Whites or White Guardsmen (russian: Бѣлогв� ...

, he took with him Beloborodov's wife and children at Beloborodov's request, as he feared for the safety of his own family as the Whites advanced on the city. Despite these efforts, Beloborodov ultimately lost his family a week later when his wife and three children drowned when a crowded ferry they had boarded to cross the River Vythegda capsized. Beloborodov himself would not learn of this until after he returned to Moscow.Rappaport p. 97

In opposition

Myasnikov was aLeft Communist

Left communism, or the communist left, is a position held by the left wing of communism, which criticises the political ideas and practices espoused by Marxist–Leninists and social democrats. Left communists assert positions which they rega ...

in 1918, opposed to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace, separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russian SFSR, Russia and the Central Powers (German Empire, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Kingdom of ...

. Towards the end of the civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, he emerged as one of the most outspoken critics of the communist state, and the only prominent Bolshevik to be expelled from the party and arrested during the lifetime of Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

. He called for freedom of the press to be restored, which the Central Committee

Central committee is the common designation of a standing administrative body of Communist party, communist parties, analogous to a board of directors, of both ruling and nonruling parties of former and existing socialist states. In such party org ...

condemned as "incompatible with the interests of the party." He also suggested that:

Lenin wrote to Myasnikov in August 1921, to say that "We do not believe in 'absolutes'. We laugh at 'pure democracy' .... Freedom of the press in the R.S.F.S.R., which is surrounded by the bourgeois enemies of the whole world, means freedom of political organisation for the bourgeoisie and its most loyal servants, the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries. The bourgeoisie (all over the world) is still very much stronger than we are. To place in its hands yet another weapon ... means facilitating the enemy’s task." Myasnikov replied that the only reason he, Myasnikov, was not in prison was that he was an old Bolshevik, while thousands of ordinary workers were in prison for saying the same things as he had.

In 1920, he also called for the formation of peasant unions to heal the breach between the urban and rural workers - making him apparently the only prominent figure in the communist party to be concerned that early about the living conditions of the rural poor.

Even after his views had been condemned by the Central Committee, Myasnikov succeeded in getting them adopted by the party organisation in Motovilikhin, where he formed a group called “Workers Group of the Russian Communist Party

The Workers Group of the Russian Communist Party was formed in 1923 to oppose the excessive power of bureaucrats and managers in the new soviet society and in the Communist Party. Its leading member was Gavril Myasnikov.

The Workers Group defend ...

”. He was expelled from the party on 22 February 1922.

Myasnikov had never belonged to the Workers Opposition, which in 1920–21, called for the management of the economy to be turned over to the trade unions. Myasnikov disagreed with the Workers' Opposition's call for unions to manage the economy. Instead, in a 1921 manifesto, Myasnikov argued that "those comrades who think there is nothing outside of the trade unions are mistaken, because there are institutions that are strictly united with each factory, each department, each workshop: these institutions are the soviets" and called for “producers’ soviets

Soviet people ( rus, сове́тский наро́д, r=sovyétsky naród), or citizens of the USSR ( rus, гра́ждане СССР, grázhdanye SSSR), was an umbrella demonym for the population of the Soviet Union.

Nationality policy in th ...

” to administer industry and for freedom of the press for all workers. Leaders of the Workers Opposition Alexander Shlyapnikov

Alexander Gavrilovich Shliapnikov (russian: link=no, Алекса́ндр Гаври́лович Шля́пников) (August 30, 1885 – September 2, 1937) was a Russian communist revolutionary, metalworker, and trade union leader. He is best ...

and Sergei Medvedev feared that Myasnikov's proposals would give too much power to peasants. But, by 1922, the two groups made common cause against the absence of free debate within the communist party. Shlyapnikov, Medvedev and Myasnikov were all signatories of the "Letter of the Twenty-Two" to the Comintern in 1922, protesting the Russian Communist Party Communist Party of Russia might refer to:

* Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, founded in 1898 – the forerunner of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks)

* Communist Party of the Soviet Union, formally established in 1912 and known origina ...

leaders' suppression of dissent among proletarian members of the Communist Party.

Myasnikov was arrested by the OGPU

The Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU; russian: Объединённое государственное политическое управление) was the intelligence and state security service and secret police of the Soviet Union f ...

in May 1923, but then released him and sent on a trade mission in Germany. There he formed ties to the Communist Workers' Party of Germany

The Communist Workers' Party of Germany (german: Kommunistische Arbeiter-Partei Deutschlands; KAPD) was an anti-parliamentarian and left communist party that was active in Germany during the time of the Weimar Republic. It was founded in April 1 ...

, a group at odds with the Russian Communist Party. These groups helped him publish the Manifesto of the Workers Group, without permission from the Russian Communist Party. Workers' Group was suppressed and later in 1923 Myasnikov was persuaded to return to Russia, where he was arrested and imprisoned.

In 1927, his sentence was changed to internal exile in Yerevan

Yerevan ( , , hy, Երևան , sometimes spelled Erevan) is the capital and largest city of Armenia and one of the world's List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest continuously inhabited cities. Situated along the Hrazdan River, Y ...

, Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''Ox ...

. In November 1928, he fled the USSR for Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

. He was arrested in Iran and then deported to Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

. In 1930, he immigrated to France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, where he worked in factories until 1944. In exile, he wrote a long essay denouncing the communist system in the Soviet Union as 'state capitalism', and calling for it to be destroyed and replaced by a workers' democracy.

In 1941, Myasnikov was arrested by Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one organi ...

after visiting the Soviet Embassy in Paris. In 1942, he escaped to Toulouse in the unoccupied zone, but was captured by the French police and sent to Camp du Récébédou. He was assigned by the Organisation Todt as a forced labourer to work on the Atlantic Wall

The Atlantic Wall (german: link=no, Atlantikwall) was an extensive system of coastal defences and fortifications built by Nazi Germany between 1942 and 1944 along the coast of continental Europe and Scandinavia as a defence against an anticip ...

defense system. He returned to Paris after being released in July 1943.

Death

In November 1944, he was invited by the Soviet embassy in France to return to the USSR. He accepted the invitation, received a visa and was sent to the USSR via the embassy on 18 December 1944. He left in January 1945, on the same aircraft as the spyAlexander Foote

Alexander Allan Foote (13 April 1905 – 1 August 1956) was a radio operator for a Soviet espionage ring in Switzerland during World War II. Foote was born in Liverpool, and raised mostly in Yorkshire by his Scottish born father and English mother. ...

. Despite the promise of amnesty, he was arrested by the Soviet secret police on 17 January 1945, and executed on 16 November 1945.

On 25 December 2001, Myasnikov was rehabilitated./ref>

Bibliography

*Avrich, Paul.'' Russian Review'', vol. 43 (1984): 1-29. *Miasnikov, G. "Filosofiia ubiistva, ili pochemu i kak ia ubil Mikhaila Romanova." ''Minuvshee'', 18 (1995): 7–191. *Alikina, Nadezhda Alekseevna. ''Don Kikhot proletarskoi revoliutsii''. Perm: Izdatel'stvo Pushka, 2006. *

References

External links

Gabriel Miasnikov Archive

at

marxists.org

Marxists Internet Archive (also known as MIA or Marxists.org) is a non-profit online encyclopedia that hosts a multilingual library (created in 1990) of the works of communist, anarchist, and socialist writers, such as Karl Marx, Friedrich Enge ...

Gabriel Miasnikov, ''The same, only in a different way''

(1920)

Gabriel Miasnikov, ''The latest deception''

(1930)

Communist League Tampa, 2015. {{DEFAULTSORT:Myasnikov, Gavril 1889 births 1945 deaths People from Chistopolsky Uyezd Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members Old Bolsheviks Left communists All-Russian Central Executive Committee members Russian murderers Regicides of Nicholas II Murder of the Romanov family People of the Russian Civil War Russian people executed by the Soviet Union Executed Soviet people from Russia