Gaelic clothing and fashion on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Gaelic Ireland ( ga, Éire Ghaelach) was the Gaelic political and social order, and associated culture, that existed in

Gaelic Ireland ( ga, Éire Ghaelach) was the Gaelic political and social order, and associated culture, that existed in

Succession to the kingship was through

Succession to the kingship was through

Gaelic law was originally passed down orally, but was written down in

Gaelic law was originally passed down orally, but was written down in

Ancient Irish culture was patriarchal. The

Ancient Irish culture was patriarchal. The

For most of the Gaelic period, dwellings and farm buildings were circular with conical thatched roofs (see roundhouse). Square and rectangle-shaped buildings gradually became more common, and by the 14th or 15th century they had replaced round buildings completely. In some areas, buildings were made mostly of stone. In others, they were built of timber,

For most of the Gaelic period, dwellings and farm buildings were circular with conical thatched roofs (see roundhouse). Square and rectangle-shaped buildings gradually became more common, and by the 14th or 15th century they had replaced round buildings completely. In some areas, buildings were made mostly of stone. In others, they were built of timber,

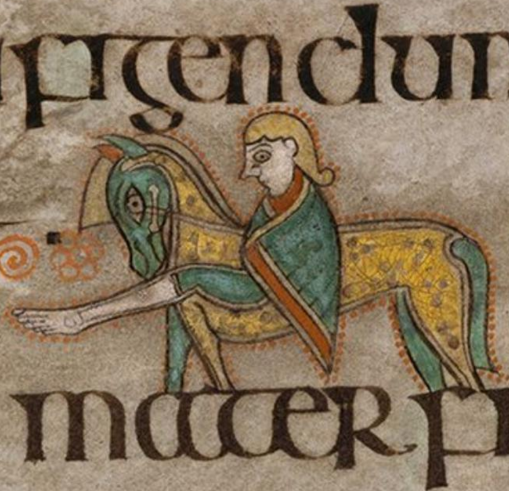

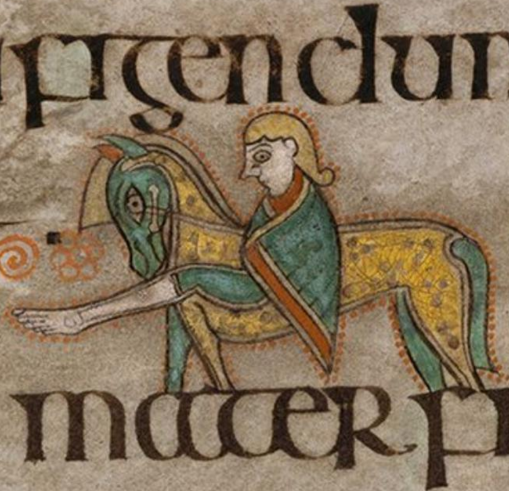

Throughout the Middle Ages, the common clothing amongst the Gaelic Irish consisted of a ''brat'' (a woollen semi circular cloak) worn over a ''léine'' (a loose-fitting, long-sleeved tunic made of linen). For men the ''léine'' reached to their ankles but was hitched up by means of a crios (pronounced 'kriss') which was a type of woven belt. The léine was hitched up to knee level. Women wore the léine at full length. Men sometimes wore tight-fitting trews (Gaelic triúbhas) but otherwise went bare-legged. The ''brat'' was simply thrown over both shoulders or sometimes over only one. Occasionally the brat was fastened with a ''dealg'' (

Throughout the Middle Ages, the common clothing amongst the Gaelic Irish consisted of a ''brat'' (a woollen semi circular cloak) worn over a ''léine'' (a loose-fitting, long-sleeved tunic made of linen). For men the ''léine'' reached to their ankles but was hitched up by means of a crios (pronounced 'kriss') which was a type of woven belt. The léine was hitched up to knee level. Women wore the léine at full length. Men sometimes wore tight-fitting trews (Gaelic triúbhas) but otherwise went bare-legged. The ''brat'' was simply thrown over both shoulders or sometimes over only one. Occasionally the brat was fastened with a ''dealg'' (

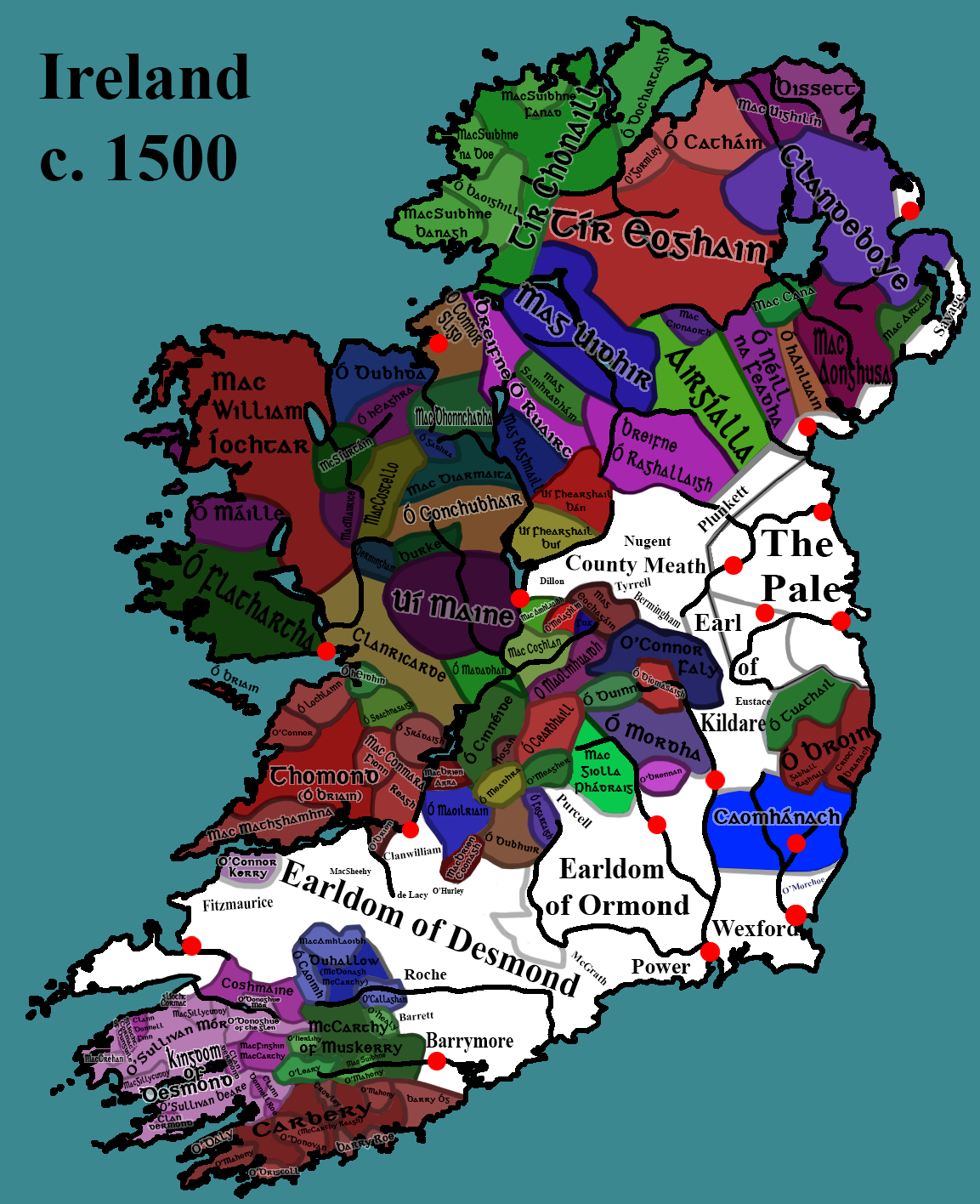

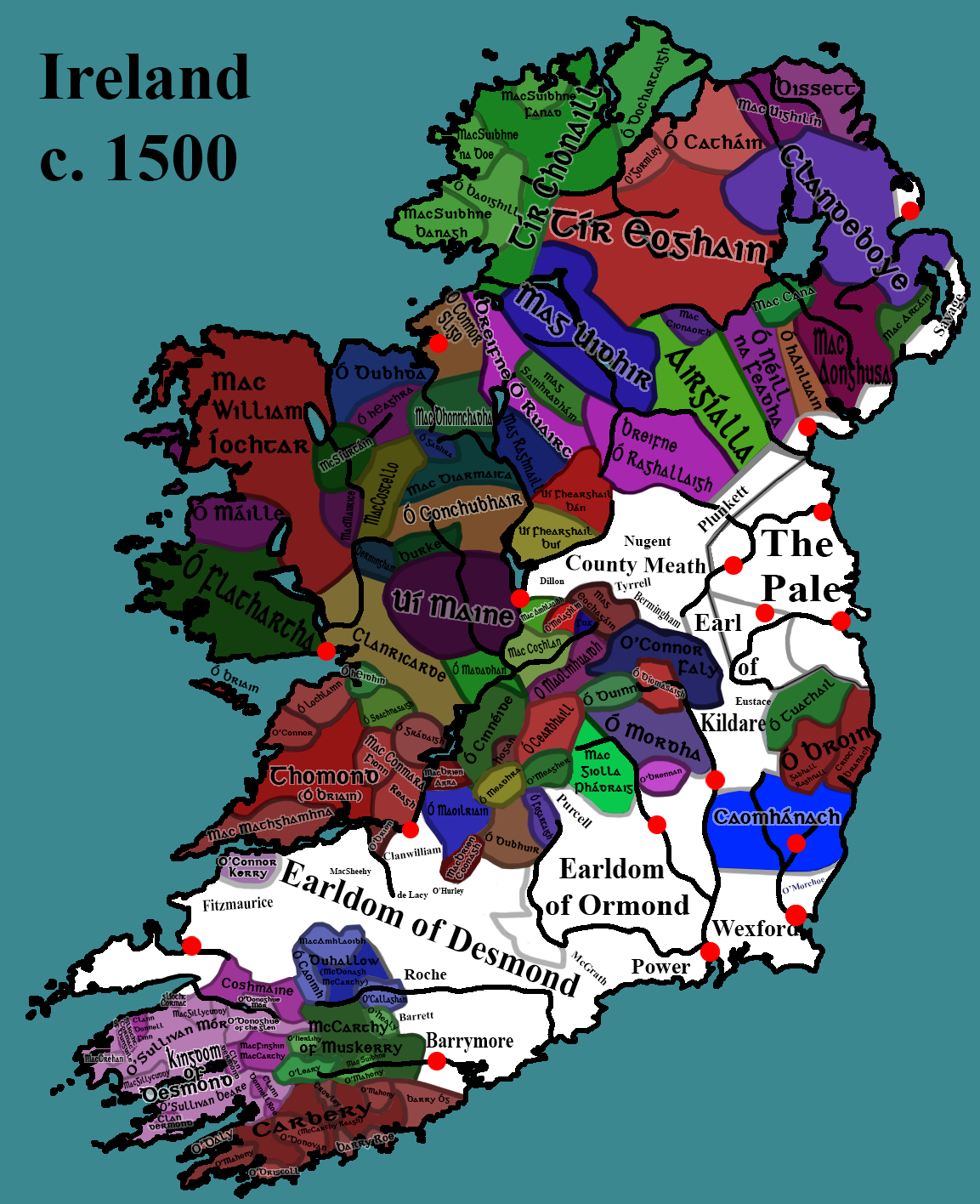

As mentioned before, Gaelic Ireland was split into many Irish Clans, clann territories and

As mentioned before, Gaelic Ireland was split into many Irish Clans, clann territories and

The Prehistoric Ireland, prehistory of

The Prehistoric Ireland, prehistory of

Gaelic Ireland of this era still consisted of the many semi-independent territories called (

Gaelic Ireland of this era still consisted of the many semi-independent territories called (

Ireland became

Ireland became

By 1261, the weakening of the

By 1261, the weakening of the

*

*  * Munster:

** Kingdom of Desmond, Desmond: Following the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland, Norman invasion of Ireland in the late 12th century, the eastern half of Desmond was conquered by the

* Munster:

** Kingdom of Desmond, Desmond: Following the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland, Norman invasion of Ireland in the late 12th century, the eastern half of Desmond was conquered by the

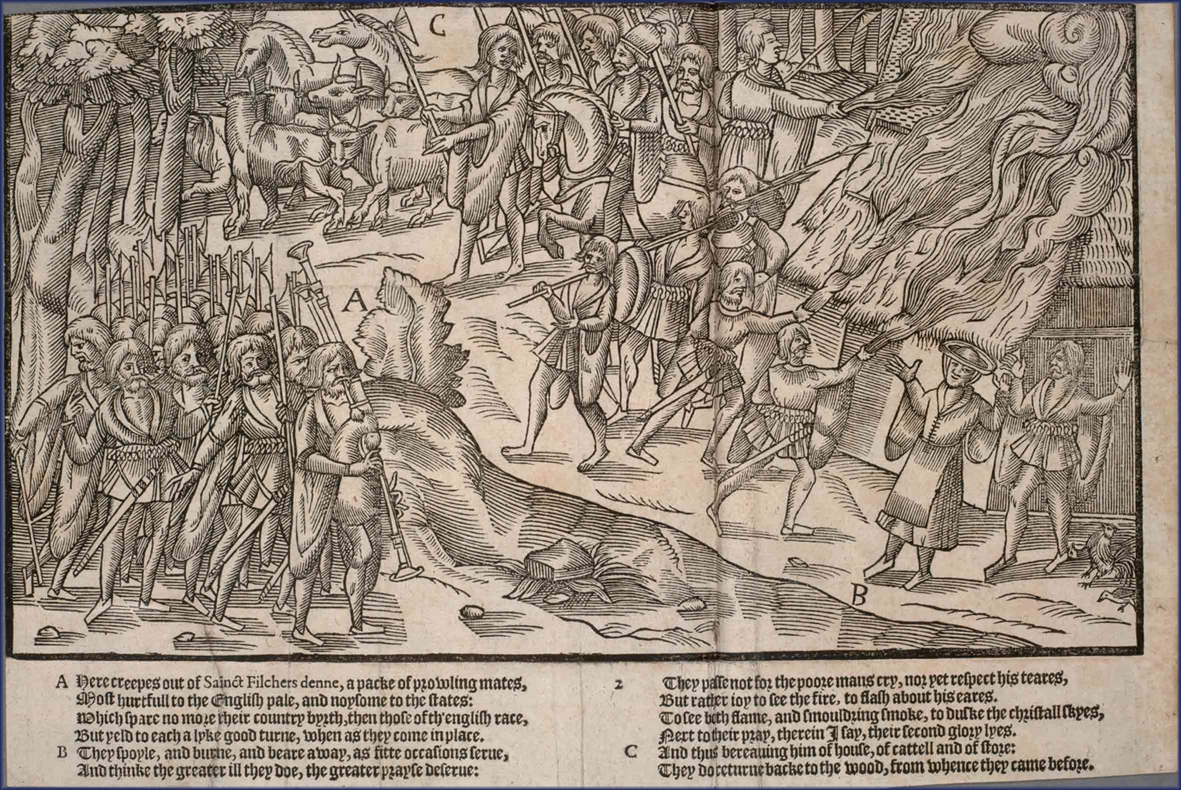

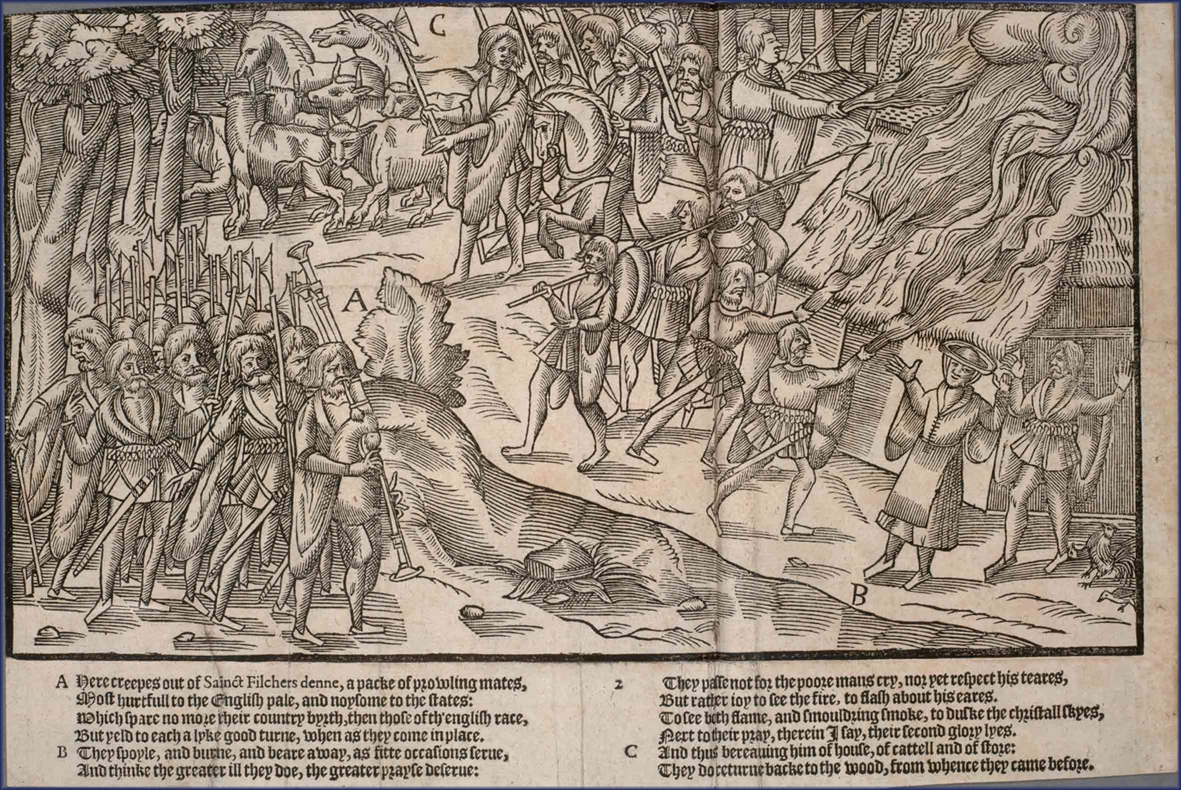

In 1603, with the Union of the Crowns, King James VI and I, King James of Scotland also became Monarchy of the United Kingdom#English monarchy, King of England and Monarchy of Ireland, Ireland. James saw the Gaels as a barbarous and rebellious people in need of civilizingEllis, Steven (2014). The Making of the British Isles: The State of Britain and Ireland, 1450–1660. Routledge. p. 296. and believed that Gaelic culture should be wiped out. James started official policies of Anglicisation in order Surrender and regrant, to convert the Gaelic nobility of Ireland to that of a Late Feudal model based upon English Law. He also set about Settler colonialism, colonising the land of the defeated rebel lords with English Language, English-speaking Protestant settlers from Great Britain, Britain, in what became known as the Plantation of Ulster. It was meant to establish a loyal Colonization, British Protestant colony in Ireland's most rebellious region and to sever County Antrim, Gaelic Ireland's Dál Riata, historical and Argyll, cultural links with Scottish Highlands, Gaelic Scotland.

The Flight of the Earls in 1607 is seen as a watershed moment for Gaelic Ireland. The flight of both Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone, Earl O'Neill of Tyrone and Hugh Roe O'Donnell, Earl O'Donnell of Tyrconnell into exile marked the destruction of the Ireland's independent

In 1603, with the Union of the Crowns, King James VI and I, King James of Scotland also became Monarchy of the United Kingdom#English monarchy, King of England and Monarchy of Ireland, Ireland. James saw the Gaels as a barbarous and rebellious people in need of civilizingEllis, Steven (2014). The Making of the British Isles: The State of Britain and Ireland, 1450–1660. Routledge. p. 296. and believed that Gaelic culture should be wiped out. James started official policies of Anglicisation in order Surrender and regrant, to convert the Gaelic nobility of Ireland to that of a Late Feudal model based upon English Law. He also set about Settler colonialism, colonising the land of the defeated rebel lords with English Language, English-speaking Protestant settlers from Great Britain, Britain, in what became known as the Plantation of Ulster. It was meant to establish a loyal Colonization, British Protestant colony in Ireland's most rebellious region and to sever County Antrim, Gaelic Ireland's Dál Riata, historical and Argyll, cultural links with Scottish Highlands, Gaelic Scotland.

The Flight of the Earls in 1607 is seen as a watershed moment for Gaelic Ireland. The flight of both Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone, Earl O'Neill of Tyrone and Hugh Roe O'Donnell, Earl O'Donnell of Tyrconnell into exile marked the destruction of the Ireland's independent

Gaelic Ireland ( ga, Éire Ghaelach) was the Gaelic political and social order, and associated culture, that existed in

Gaelic Ireland ( ga, Éire Ghaelach) was the Gaelic political and social order, and associated culture, that existed in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

from the late prehistoric era

Prehistory, also known as pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the use of the first stone tools by hominins 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use of ...

until the early 17th century. It comprised the whole island before Anglo-Normans conquered parts of Ireland in the 1170s. Thereafter, it comprised that part of the country not under foreign dominion at a given time (i.e. the part beyond The Pale

The Pale (Irish: ''An Pháil'') or the English Pale (' or ') was the part of Ireland directly under the control of the English government in the Late Middle Ages. It had been reduced by the late 15th century to an area along the east coast st ...

). For most of its history, Gaelic Ireland was a "patchwork" hierarchy of territories ruled by a hierarchy of kings or chiefs, who were chosen or elected through tanistry

Tanistry is a Gaelic system for passing on titles and lands. In this system the Tanist ( ga, Tánaiste; gd, Tànaiste; gv, Tanishtey) is the office of heir-apparent, or second-in-command, among the (royal) Gaelic patrilineal dynasties of Ir ...

. Warfare

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regul ...

between these territories was common. Occasionally, a powerful ruler was acknowledged as High King of Ireland. Society was made up of clans and, like the rest of Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

, was structured hierarchically according to class

Class or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used differentl ...

. Throughout this period, the economy was mainly pastoral and money was generally not used. A Gaelic Irish style of dress

A dress (also known as a frock or a gown) is a garment traditionally worn by women or girls consisting of a skirt with an attached bodice (or a matching bodice giving the effect of a one-piece garment). It consists of a top piece that co ...

, music

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspe ...

, dance, sport

Sport pertains to any form of competitive physical activity or game that aims to use, maintain, or improve physical ability and skills while providing enjoyment to participants and, in some cases, entertainment to spectators. Sports can, ...

and art

Art is a diverse range of human activity, and resulting product, that involves creative or imaginative talent expressive of technical proficiency, beauty, emotional power, or conceptual ideas.

There is no generally agreed definition of wha ...

can be identified, with Irish art later merging with Anglo-Saxon styles to create Insular art.

Gaelic Ireland was initially pagan and had an oral culture

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication wherein knowledge, art, ideas and cultural material is received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another. Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (1985) ...

maintained by traditional Gaelic storytellers/historians, the '' seanchaidhthe''. Writing, in the form of inscription

Epigraphy () is the study of inscriptions, or epigraphs, as writing; it is the science of identifying graphemes, clarifying their meanings, classifying their uses according to dates and cultural contexts, and drawing conclusions about the w ...

in the ogham

Ogham ( Modern Irish: ; mga, ogum, ogom, later mga, ogam, label=none ) is an Early Medieval alphabet used primarily to write the early Irish language (in the "orthodox" inscriptions, 4th to 6th centuries AD), and later the Old Irish langu ...

alphabet

An alphabet is a standardized set of basic written graphemes (called letters) that represent the phonemes of certain spoken languages. Not all writing systems represent language in this way; in a syllabary, each character represents a syllab ...

, began in the protohistoric period, perhaps as early as the 1st century. The conversion to Christianity, beginning in the 5th century, accompanied the introduction of literature

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to include ...

. In the Middle Ages, Irish mythology

Irish mythology is the body of myths native to the island of Ireland. It was originally passed down orally in the prehistoric era, being part of ancient Celtic religion. Many myths were later written down in the early medieval era by Ch ...

and Brehon law

Early Irish law, historically referred to as (English: Freeman-ism) or (English: Law of Freemen), also called Brehon law, comprised the statutes which governed everyday life in Early Medieval Ireland. They were partially eclipsed by the Norma ...

were recorded by Irish monks, albeit partly Christianized

Christianization ( or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of an individual, a practice, a place or a whole society. It began in the Roman Empire, conti ...

. Gaelic Irish monasteries were important centres of learning. Irish missionaries and scholars were influential in western Europe and helped to spread Christianity to much of Britain and parts of mainland Europe.

In the 9th century, Vikings

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and ...

began raiding and founding settlements along Ireland's coasts and waterways, which became its first large towns. Over time, these settlers were assimilated and became the Norse-Gaels. After the Norman invasion

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Normans, Norman, Duchy of Brittany, Breton, County of Flanders, Flemish, and Kingdom of France, French troops, ...

of 1169–71, large swathes of Ireland came under the control of Norman

Norman or Normans may refer to:

Ethnic and cultural identity

* The Normans, a people partly descended from Norse Vikings who settled in the territory of Normandy in France in the 10th and 11th centuries

** People or things connected with the Norm ...

lords, leading to centuries of conflict with the native Irish. The King of England claimed sovereignty over this territory – the Lordship of Ireland

The Lordship of Ireland ( ga, Tiarnas na hÉireann), sometimes referred to retroactively as Norman Ireland, was the part of Ireland ruled by the King of England (styled as "Lord of Ireland") and controlled by loyal Anglo-Norman lords between ...

– and the island as a whole. However, the Gaelic system continued in areas outside Anglo-Norman Anglo-Norman may refer to:

*Anglo-Normans, the medieval ruling class in England following the Norman conquest of 1066

* Anglo-Norman language

**Anglo-Norman literature

* Anglo-Norman England, or Norman England, the period in English history from 10 ...

control. The territory under English control gradually shrank to an area known as the Pale

The Pale (Irish: ''An Pháil'') or the English Pale (' or ') was the part of Ireland directly under the control of the English government in the Late Middle Ages. It had been reduced by the late 15th century to an area along the east coast st ...

and, outside this, many Hiberno-Norman lords adopted Gaelic culture.

In 1542, the Lordship of Ireland

The Lordship of Ireland ( ga, Tiarnas na hÉireann), sometimes referred to retroactively as Norman Ireland, was the part of Ireland ruled by the King of England (styled as "Lord of Ireland") and controlled by loyal Anglo-Norman lords between ...

became the Kingdom of Ireland when Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

was given the title of King of Ireland by the Parliament of Ireland

The Parliament of Ireland ( ga, Parlaimint na hÉireann) was the legislature of the Lordship of Ireland, and later the Kingdom of Ireland, from 1297 until 1800. It was modelled on the Parliament of England and from 1537 comprised two cham ...

. The English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

then began to extend their control over the island. By 1607, Ireland was fully under English control, bringing the old Gaelic political and social order to an end.

Culture and society

Gaelic culture and society was centred around the ''fine'' (explained below). Gaelic Ireland had a rich oral culture and appreciation of deeper and intellectual pursuits. ''Filí

The filí (singular: file) were members of an elite class of poets in Ireland and Scotland, up until the Renaissance.

Etymology

The word "file" is thought to derive from the Proto-Celtic ''*widluios'', meaning "seer, one who sees" (attested ...

'' and '' draoithe'' (druids) were held in high regard during Pagan times and orally passed down the history and traditions of their people. Later, many of their spiritual and intellectual tasks were passed on to Christian monks, after said religion prevailed from the 5th century onwards. However, the ''filí'' continued to hold a high position. Poetry, music, storytelling, literature and other art forms were highly prized and cultivated in both pagan and Christian Gaelic Ireland. Hospitality, bonds of kinship and the fulfilment of social and ritual responsibilities were highly important.

Like Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

, Gaelic Ireland consisted not of one single unified kingdom, but several. The main kingdoms were Ulaid

Ulaid (Old Irish, ) or Ulaidh ( Modern Irish, ) was a Gaelic over-kingdom in north-eastern Ireland during the Middle Ages made up of a confederation of dynastic groups. Alternative names include Ulidia, which is the Latin form of Ulaid, and i ...

(Ulster), Mide

Meath (; Old Irish: ''Mide'' ; spelt ''Mí'' in Modern Irish) was a kingdom in Ireland from the 1st to the 12th century AD. Its name means "middle," denoting its location in the middle of the island.

At its greatest extent, it included all ...

(Meath), Laigin

The Laigin, modern spelling Laighin (), were a Gaelic population group of early Ireland. They gave their name to the Kingdom of Leinster, which in the medieval era was known in Irish as ''Cóiced Laigen'', meaning "Fifth/province of the Leinster ...

(Leinster), Muma (Munster, consisting of Iarmuman

Iarmhumhain (older spellings: Iarmuman, Iarmumu or Iarluachair) was a Kingdom in the early Christian period of Ireland in west Munster. Its ruling dynasty was related to the main ruling dynasty of Munster known as the Eóganachta. Its ruling branc ...

, Tuadmumain and Desmumain), Connacht

Connacht ( ; ga, Connachta or ), is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the west of Ireland. Until the ninth century it consisted of several independent major Gaelic kingdoms ( Uí Fiachrach, Uí Briúin, Uí Maine, Conmhaícne, and Del ...

, Bréifne (Breffny), In Tuaiscert (The North), and Airgíalla (Oriel). Each of these overkingdoms were built upon lordships known as ''túath

''Túath'' (plural ''túatha'') is the Old Irish term for the basic political and jurisdictional unit of Gaelic Ireland. ''Túath'' can refer to both a geographical territory as well the people who lived in that territory.

Social structure

In ...

a'' (singular: ''túath''). Law tracts from the early 700s describe a hierarchy of kings: kings of ''túath'' subject to kings of several ''túatha'' who again were subject to the regional overkings. Already before the 8th century these overkingdoms had begun to replace the túatha as the basic sociopolitical unit.

Religion and mythology

Paganism

BeforeChristianization

Christianization ( or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of an individual, a practice, a place or a whole society. It began in the Roman Empire, conti ...

, the Gaelic Irish were polytheistic

Polytheism is the belief in multiple deities, which are usually assembled into a pantheon of gods and goddesses, along with their own religious sects and rituals. Polytheism is a type of theism. Within theism, it contrasts with monotheism, the ...

or pagan. They had many gods and goddesses, which generally have parallels in the pantheons of other European nations. Two groups of supernatural beings who appear throughout Irish mythology—the Tuatha Dé Danann

The Tuath(a) Dé Danann (, meaning "the folk of the goddess Danu"), also known by the earlier name Tuath Dé ("tribe of the gods"), are a supernatural race in Irish mythology. Many of them are thought to represent deities of pre-Christian Gae ...

and Fomorians

The Fomorians or Fomori ( sga, Fomóire, Modern ga, Fomhóraigh / Fomóraigh) are a supernatural race in Irish mythology, who are often portrayed as hostile and monstrous beings. Originally they were said to come from under the sea or the eart ...

—are believed to represent the Gaelic pantheon. They were also animists

Animism (from Latin: ' meaning 'breath, spirit, life') is the belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence. Potentially, animism perceives all things—animals, plants, rocks, rivers, weather systems, hu ...

, believing that all aspects of the natural world contained spirits, and that these spirits could be communicated with. Burial practices—which included burying food, weapons, and ornaments with the dead—suggest a belief in life after death

The afterlife (also referred to as life after death) is a purported existence in which the essential part of an individual's identity or their stream of consciousness continues to live after the death of their physical body. The surviving ess ...

. Some have equated this afterlife with the Otherworld

The concept of an otherworld in historical Indo-European religion is reconstructed in comparative mythology. Its name is a calque of ''orbis alius'' (Latin for "other Earth/world"), a term used by Lucan in his description of the Celtic Otherwor ...

realms known as Magh Meall and Tír na nÓg

In Irish mythology Tír na nÓg (; "Land of the Young") or Tír na hÓige ("Land of Youth") is one of the names for the Celtic Otherworld, or perhaps for a part of it. Tír na nÓg is best known from the tale of Oisín and Niamh.

Other Old Ir ...

in Irish mythology. There were four main religious festivals each year, marking the traditional four divisions of the year – Samhain

Samhain ( , , , ; gv, Sauin ) is a Gaelic festival on 1 NovemberÓ hÓgáin, Dáithí. ''Myth Legend and Romance: An Encyclopaedia of the Irish Folk Tradition''. Prentice Hall Press, 1991. p. 402. Quote: "The basic Irish division of the year ...

, Imbolc

Imbolc or Imbolg (), also called Saint Brigid's Day ( ga, Lá Fhéile Bríde; gd, Là Fhèill Brìghde; gv, Laa'l Breeshey), is a Gaelic traditional festival. It marks the beginning of spring, and for Christians it is the feast day of Saint B ...

, Bealtaine

Beltane () is the Gaelic May Day festival. Commonly observed on the first of May, the festival falls midway between the spring equinox and summer solstice in the northern hemisphere. The festival name is synonymous with the month marking th ...

and Lughnasadh

Lughnasadh or Lughnasa ( , ) is a Gaelic festival marking the beginning of the harvest season. Historically, it was widely observed throughout Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man. In Modern Irish it is called , in gd, Lùnastal, and in gv, ...

.

The mythology of Ireland was originally passed down orally, but much of it was eventually written down by Irish monks

The Hiberno-Scottish mission was a series of expeditions in the 6th and 7th centuries by Gaelic missionaries originating from Ireland that spread Celtic Christianity in Scotland, Wales, England and Merovingian France. Celtic Christianity sp ...

, who Christianized and modified it to an extent. This large body of work is often split into three overlapping cycles: the Mythological Cycle

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not objectively true, the identification of a narrati ...

, the Ulster Cycle

The Ulster Cycle ( ga, an Rúraíocht), formerly known as the Red Branch Cycle, is a body of medieval Irish heroic legends and sagas of the Ulaid. It is set far in the past, in what is now eastern Ulster and northern Leinster, particularly coun ...

, and the Fenian Cycle

The Fenian Cycle (), Fianna Cycle or Finn Cycle ( ga, an Fhiannaíocht) is a body of early Irish literature focusing on the exploits of the mythical hero Finn or Fionn mac Cumhaill and his warrior band the Fianna. Sometimes called the Ossi ...

. The first cycle is a pseudo-history that describes how Ireland, its people and its society came to be. The second cycle tells of the lives and deaths of Ulaid

Ulaid (Old Irish, ) or Ulaidh ( Modern Irish, ) was a Gaelic over-kingdom in north-eastern Ireland during the Middle Ages made up of a confederation of dynastic groups. Alternative names include Ulidia, which is the Latin form of Ulaid, and i ...

h heroes and villains such as Cúchulainn, Queen Medb and Conall Cernach

Conall Cernach (modern spelling: Conall Cearnach) is a hero of the Ulaid in the Ulster Cycle of Irish mythology. He had a crooked neck and is said to have always slept with the head of a Connachtman under his knee. His epithet is normally transla ...

. The third cycle tells of the exploits of Fionn mac Cumhaill

Fionn mac Cumhaill ( ; Old and mga, Find or ''mac Cumail'' or ''mac Umaill''), often anglicized Finn McCool or MacCool, is a hero in Irish mythology, as well as in later Scottish and Manx folklore. He is leader of the ''Fianna'' bands of y ...

and the Fianna

''Fianna'' ( , ; singular ''Fian''; gd, Fèinne ) were small warrior-hunter bands in Gaelic Ireland during the Iron Age and early Middle Ages. A ''fian'' was made up of freeborn young males, often aristocrats, "who had left fosterage but had ...

. There are also a number of tales that do not fit into these cycles – this includes the ''immrama

An immram (; plural immrama; ga, iomramh , 'voyage') is a class of Old Irish tales concerning a hero's sea journey to the Otherworld (see Tír na nÓg and Mag Mell). Written in the Christian era and essentially Christian in aspect, they prese ...

'' and '' echtrai'', which are tales of voyages to the 'Otherworld

The concept of an otherworld in historical Indo-European religion is reconstructed in comparative mythology. Its name is a calque of ''orbis alius'' (Latin for "other Earth/world"), a term used by Lucan in his description of the Celtic Otherwor ...

'.

Christianity

The introduction of Christianity to Ireland dates to sometime before the 5th century, with Palladius (later bishop of Ireland) sent byPope Celestine I

Pope Celestine I ( la, Caelestinus I) (c. 376 – 1 August 432) was the bishop of Rome from 10 September 422 to his death on 1 August 432. Celestine's tenure was largely spent combatting various ideologies deemed heretical. He supported the missi ...

in the mid-5th century to preach "''ad Scotti in Christum''"M. De Paor – L. De Paor, Early Christian Ireland, London, 1958, p. 27. or in other words to minister to the Scoti

''Scoti'' or ''Scotti'' is a Latin name for the Gaels,Duffy, Seán. ''Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia''. Routledge, 2005. p.698 first attested in the late 3rd century. At first it referred to all Gaels, whether in Ireland or Great Britain, but l ...

or Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

"believing in Christ". Early medieval traditions credit Saint Patrick as being the first Primate of Ireland

The Primacy of Ireland was historically disputed between the Archbishop of Armagh and the Archbishop of Dublin until finally settled by Pope Innocent VI. ''Primate'' is a title of honour denoting ceremonial precedence in the Church, and in ...

. Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

would eventually supplant the existing pagan traditions, with the prologue of the 9th century ''Martyrology of Tallaght

The ''Martyrology of Tallaght'', which is closely related to the '' Félire Óengusso'' or ''Martyrology of Óengus the Culdee'', is an eighth- or ninth-century martyrology, a list of saints and their feast days assembled by Máel Ruain and/o ...

'' (attributed to author Óengus of Tallaght

Óengus mac Óengobann, better known as Saint Óengus of Tallaght or Óengus the Culdee, was an Irish bishop, reformer and writer, who flourished in the first quarter of the 9th century and is held to be the author of the ''Félire Óengusso'' ...

) speaking of the last vestiges of paganism in Ireland.

Social and political structure

In Gaelic Ireland each person belonged to an agnatic kin-group known as a ''fine'' (plural: ''finte''). This was a large group of related people supposedly descended from one progenitor through male forebears. It was headed by a man whose office was known in Old Irish as a ''cenn fine'' or ''toísech'' (plural: ''toísig''). Nicholls suggests that they would be better thought of as akin to the modern-day corporation. Within each ''fine'', the family descended from a common great-grandparent was called a ''derbfine

The derbfine ( ; ga, dearbhfhine , from ''derb'' 'real' + ''fine'' 'group of persons of the same family or kindred', thus literally 'true kin'electronic Dictionary of the Irish Language s.vderbḟine/ref>) was a term for patrilineal groups and po ...

'' (modern form ''dearbhfhine''), lit. "close clan". The ''cland'' (modern form ''clann'') referred to the children of the nuclear family.

Succession to the kingship was through

Succession to the kingship was through tanistry

Tanistry is a Gaelic system for passing on titles and lands. In this system the Tanist ( ga, Tánaiste; gd, Tànaiste; gv, Tanishtey) is the office of heir-apparent, or second-in-command, among the (royal) Gaelic patrilineal dynasties of Ir ...

. When a man became king, a relative was elected to be his deputy or 'tanist' (Irish: ''tánaiste'', plural ''tanaistí''). When the king died, his tanist would automatically succeed him. The tanist had to share the same ''derbfine'' and he was elected by other members of the ''derbfine''. Tanistry meant that the kingship usually went to whichever relative was deemed to be the most fitting. Sometimes there would be more than one tanist at a time and they would succeed each other in order of seniority. Some Anglo-Norman lordships later adopted tanistry from the Irish.

Gaelic Ireland was divided into a hierarchy of territories ruled by a hierarchy of kings of chiefs. The smallest territory was the ''túath

''Túath'' (plural ''túatha'') is the Old Irish term for the basic political and jurisdictional unit of Gaelic Ireland. ''Túath'' can refer to both a geographical territory as well the people who lived in that territory.

Social structure

In ...

'' (plural: ''túatha''), which was typically the territory of a single kin-group. It was ruled by a ''rí túaithe'' (king of a ''túath'') or ''toísech túaithe'' (leader of a ''túath''). Several ''túatha'' formed a ''mór túath'' (overkingdom), which was ruled by a ''rí mór túath'' or ''ruirí'' (overking). Several ''mór túatha'' formed a ''cóiced'' (province), which was ruled by a ''rí cóicid'' or ''rí ruirech'' (provincial king). In the early Middle Ages the ''túatha'' was the main political unit, but over time they were subsumed into bigger conglomerate territories and became much less important politically.

Gaelic society was structured hierarchically, with those further up the hierarchy generally having more privileges, wealth and power than those further down.

* The top social layer was the ''sóernemed'', which included kings, tanists, ''ceann finte'', '' fili'', clerics, and their immediate families. The roles of a ''fili'' included reciting traditional lore, eulogizing the king and satirizing injustices within the kingdom. Before the Christianization of Ireland, this group also included the druids (''druí'') and vates

In modern English, the nouns vates () and ovate (, ), are used as technical terms for ancient Celtic bards, prophets and philosophers. The terms correspond to a Proto-Celtic word which can be reconstructed as *''wātis''.Bernhard Maier, ''Dictio ...

(''fáith'').

* Below that were the ''dóernemed'', which included professionals such as jurists (''brithem''), physicians, skilled craftsmen, skilled musicians, scholars, and so on. A master in a particular profession was known as an ''ollam

An or ollamh (; anglicised as ollave or ollav), plural ollomain, in early Irish literature, is a member of the highest rank of filí. The term is used to refer to the highest member of any group; thus an ''ollam brithem'' would be the highes ...

'' (modern spelling: ''ollamh''). The various professions—including law, poetry, medicine, history and genealogy—were associated with particular families and the positions became hereditary. Since the poets, jurists and doctors depended on the patronage of the ruling families, the end of the Gaelic order brought their demise.

* Below that were freemen who owned land and cattle (for example the '' bóaire'').

* Below that were freemen who did not own land or cattle, or who owned very little.

* Below that were the unfree, which included serfs and slaves. Slaves were typically criminals ( debt slaves) or prisoners of war. Slavery and serfdom was inherited, though slavery in Ireland

Slavery had already existed in Ireland for centuries by the time the Vikings began to establish their coastal settlements, but it was under the Norse-Gael Kingdom of Dublin that it reached its peak, in the 11th century.

History

Gaelic Ireland

...

had died out by 1200.

* The warrior bands known as ''fianna

''Fianna'' ( , ; singular ''Fian''; gd, Fèinne ) were small warrior-hunter bands in Gaelic Ireland during the Iron Age and early Middle Ages. A ''fian'' was made up of freeborn young males, often aristocrats, "who had left fosterage but had ...

'' generally lived apart from society. A ''fian'' was typically composed of young men who had not yet come into their inheritance

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, titles, debts, entitlements, privileges, rights, and obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ among societies and have changed over time. Officia ...

of land. A member of a ''fian'' was called a ''fénnid'' and the leader of a ''fian'' was a ''rígfénnid''. Geoffrey Keating

Geoffrey Keating ( ga, Seathrún Céitinn; c. 1569 – c. 1644) was a 17th-century historian. He was born in County Tipperary, Ireland, and is buried in Tubrid Graveyard in the parish of Ballylooby-Duhill. He became an Irish Catholic priest and a ...

, in his 17th-century ''History of Ireland'', says that during the winter the ''fianna'' were quartered and fed by the nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The character ...

, during which time they would keep order on their behalf. But during the summer, from Bealtaine

Beltane () is the Gaelic May Day festival. Commonly observed on the first of May, the festival falls midway between the spring equinox and summer solstice in the northern hemisphere. The festival name is synonymous with the month marking th ...

to Samhain

Samhain ( , , , ; gv, Sauin ) is a Gaelic festival on 1 NovemberÓ hÓgáin, Dáithí. ''Myth Legend and Romance: An Encyclopaedia of the Irish Folk Tradition''. Prentice Hall Press, 1991. p. 402. Quote: "The basic Irish division of the year ...

, they were beholden to live by hunting for food and for hides to sell.

Although distinct, these ranks were not utterly exclusive castes like those of India. It was possible to rise or sink from one rank to another. Rising upward could be achieved a number of ways, such as by gaining wealth, by gaining skill in some department, by qualifying for a learned profession, by showing conspicuous valour, or by performing some service to the community. An example of the latter is a person choosing to become a ''briugu'' (hospitaller). A ''briugu'' had to have his house open to any guests, which included feeding no matter how big the group. For the ''briugu'' to fulfill these duties, he was allowed more land and privileges, but this could be lost if he ever refused guests.

A freeman could further himself by becoming the client of one or more lords. The lord made his client a grant of property (i.e. livestock or land) and, in return, the client owed his lord yearly payments of food and fixed amounts of work. The clientship agreement could last until the lord's death. If the client died, his heirs would carry on the agreement. This system of clientship enabled social mobility as a client could increase his wealth until he could afford clients of his own, thus becoming a lord. Clientship was also practised between nobles, which established hierarchies of homage and political support.

Law

Gaelic law was originally passed down orally, but was written down in

Gaelic law was originally passed down orally, but was written down in Old Irish

Old Irish, also called Old Gaelic ( sga, Goídelc, Ogham script: ᚌᚑᚔᚇᚓᚂᚉ; ga, Sean-Ghaeilge; gd, Seann-Ghàidhlig; gv, Shenn Yernish or ), is the oldest form of the Goidelic/Gaelic language for which there are extensive writt ...

during the period 600–900 AD. This collection of oral and written laws is known as the ''Fénechas'' or, in English, as the Brehon Law(s). The brehon

Brehon ( ga, breitheamh, ) is a term for a historical arbitration, mediative and judicial role in Gaelic culture. Brehons were part of the system of Early Irish law, which was also simply called " Brehon law". Brehons were judges, close in impo ...

s (Old Irish: ''brithem'', plural ''brithemain'') were the jurists in Gaelic Ireland. Becoming a brehon took many years of training and the office was, or became, largely hereditary. Most legal cases were contested privately between opposing parties, with the brehons acting as arbitrators.

Offences against people and property were primarily settled by the offender paying compensation to the victims. Although any such offence required compensation, the law made a distinction between intentional and unintentional harm, and between murder and manslaughter. If an offender did not pay outright, his property was seized until he did so. Should the offender be unable to pay, his family would be responsible for doing so. Should the family be unable or unwilling to pay, responsibility would broaden to the wider kin-group. Hence, it has been argued that "the people were their own police". Acts of violence were generally settled by payment of compensation known as an ''éraic

Éraic (or ''eric'') was the Irish equivalent of the Welsh galanas and the Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian weregild, a form of tribute paid in reparation for murder or other major crimes. The term survived into the sixteenth century as ', by then r ...

'' fine; the Gaelic equivalent of the Welsh ''galanas

''Galanas'' in Welsh law was a payment made by a killer and his family to the family of his or her victim. It is similar to éraic in Ireland and the Anglo-Saxon weregild.

The compensation depended on the status of the victim, but could also be af ...

'' and the Germanic ''weregild

Weregild (also spelled wergild, wergeld (in archaic/historical usage of English), weregeld, etc.), also known as man price (blood money), was a precept in some archaic legal codes whereby a monetary value was established for a person's life, to b ...

''. If a free person was murdered, the ''éraic'' was equal to 21 cows, regardless of the victim's rank in society. Each member of the murder victim's agnatic kin-group received a payment based on their closeness to the victim, their status, and so forth. There were separate payments for the kin-group of the victim's mother, and for the victim's foster-kin.

Execution seems to have been rare and carried out only as a last resort. If a murderer was unable or unwilling to pay ''éraic'' and was handed to his victim's family, they might kill him if they wished should nobody intervene by paying the ''éraic''. Habitual or particularly serious offenders might be expelled from the kin-group and its territory. Such people became outlaws (with no protection from the law) and anyone who sheltered him became liable for his crimes. If he still haunted the territory and continued his crimes there, he was proclaimed in a public assembly and after this anyone might lawfully kill him.

Each person had an honour-price, which varied depending on their rank in society. This honour-price was to be paid to them if their honour was violated by certain offences. Those of higher rank had a higher honour-price. However, an offence against the property of a poor man (who could ill afford it), was punished more harshly than a similar offence upon a wealthy man. The clergy were more harshly punished than the laity. When a layman had paid his fine he would go through a probationary period and then regain his standing, but a clergyman could never regain his standing.

Some laws were pre-Christian in origin. These secular laws existed in parallel, and sometimes in conflict, with Church law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is th ...

. Although brehons usually dealt with legal cases, kings would have been able to deliver judgments also, but it is unclear how much they would have had to rely on brehons. Kings had their own brehons to deal with cases involving the king's own rights and to give him legal advice. Unlike other kingdoms in Europe, Gaelic kings—by their own authority—could not enact new laws as they wished and could not be "above the law". They could, however, enact temporary emergency laws. It was mainly through these emergency powers that the Church attempted to change Gaelic law.

The law texts take great care to define social status, the rights and duties that went with that status, and the relationships between people. For example, ''ceann finte'' had to take responsibility for members of their ''fine'', acting as a surety for some of their deeds and making sure debts were paid. He would also be responsible for unmarried women after the death of their fathers.

Marriage, women and children

Ancient Irish culture was patriarchal. The

Ancient Irish culture was patriarchal. The Brehon

Brehon ( ga, breitheamh, ) is a term for a historical arbitration, mediative and judicial role in Gaelic culture. Brehons were part of the system of Early Irish law, which was also simply called " Brehon law". Brehons were judges, close in impo ...

law excepted women from the ordinary course of the law so that, in general, every woman had to have a male guardian. However, women had some legal capacity. By the 8th century, the preferred form of marriage was one between social equals, under which a woman was technically legally dependent on her husband and had half his honor price, but could exercise considerable authority in regard to the transfer of property. Such women were called "women of joint dominion". Thus historian Patrick Weston Joyce

Patrick Weston Joyce, commonly known as P. W. Joyce (1827 – 7 January 1914) was an Irish historian, writer and music collector, known particularly for his research in Irish etymology and local place names of Ireland.

Biography

He was born i ...

could write that, relative to other European countries of the time, free women in Gaelic Ireland "held a good position" and their social and property rights were "in most respects, quite on a level with men".

Gaelic Irish society was also patrilineal

Patrilineality, also known as the male line, the spear side or agnatic kinship, is a common kinship system in which an individual's family membership derives from and is recorded through their father's lineage. It generally involves the inheritan ...

, with land being primarily owned by men and inherited by the sons. Only when a man had no sons would his land pass to his daughters, and then only for their lifetimes. Upon their deaths, the land was redistributed among their father's male relations. Under Brehon law, rather than inheriting land, daughters had assigned to them a certain number of their father's cattle as their marriage-portion. It seems that, throughout the Middle Ages, the Gaelic Irish kept many of their marriage laws and traditions separate from those of the Church. Under Gaelic law, married women could hold property independent of their husbands, a link was maintained between married women and their own families, couples could easily divorce or separate, and men could have concubines

Concubinage is an interpersonal and sexual relationship between a man and a woman in which the couple does not want, or cannot enter into a full marriage. Concubinage and marriage are often regarded as similar but mutually exclusive.

Concubi ...

(which could be lawfully bought). These laws differed from most of contemporary Europe and from Church law.

The lawful age of marriage

Marriageable age (or marriage age) is the general age, as a legal age or as the minimum age subject to parental, religious or other forms of social approval, at which a person is legitimately allowed for marriage. Age and other prerequisites to ...

was fifteen for girls and eighteen for boys, the respective ages at which fosterage

Fosterage, the practice of a family bringing up a child not their own, differs from adoption in that the child's parents, not the foster-parents, remain the acknowledged parents. In many modern western societies foster care can be organised by th ...

ended. Upon marriage, the families of the bride and bridegroom were expected to contribute to the match. It was custom for the bridegroom and his family to pay a ''coibche'' (modern spelling: ''coibhche'') and the bride was allowed a share of it. If the marriage ended owing to a fault of the husband then the ''coibche'' was kept by the wife and her family, but if the fault lay with the wife then the ''coibche'' was to be returned. It was custom for the bride to receive a ''spréid'' (modern spelling: ''spréidh'') from her family (or foster family) upon marriage. This was to be returned if the marriage ended through divorce or the death of the husband. Later, the ''spréid'' seems to have been converted into a dowry

A dowry is a payment, such as property or money, paid by the bride's family to the groom or his family at the time of marriage. Dowry contrasts with the related concepts of bride price and dower. While bride price or bride service is a payment ...

. Women could seek divorce/separation as easily as men could and, when obtained on her behalf, she kept all the property she had brought her husband during their marriage. Trial marriages seem to have been popular among the rich and powerful, and thus it has been argued that cohabitation

Cohabitation is an arrangement where people who are not married, usually couples, live together. They are often involved in a romantic or sexually intimate relationship on a long-term or permanent basis. Such arrangements have become increas ...

before marriage must have been acceptable. It also seems that the wife of a chieftain was entitled to some share of the chief's authority over his territory. This led to some Gaelic Irish wives wielding a great deal of political power.

Before the Norman invasion, it was common for priests and monks to have wives. This remained mostly unchanged after the Norman invasion, despite protests from bishops and archbishops. The authorities classed such women as priests' concubines and there is evidence that a formal contract of concubinage existed between priests and their women. However, unlike other concubines, they seem to have been treated just as wives were.

In Gaelic Ireland a kind of fosterage

Fosterage, the practice of a family bringing up a child not their own, differs from adoption in that the child's parents, not the foster-parents, remain the acknowledged parents. In many modern western societies foster care can be organised by th ...

was common, whereby (for a certain length of time) children would be left in the care of others to strengthen family ties or political bonds. Foster parents were beholden to teach their foster children or to have them taught. Foster parents who had properly done their duties were entitled to be supported by their foster children in old age (if they were in need and had no children of their own). As with divorce, Gaelic law again differed from most of Europe and from Church law in giving legal standing to both "legitimate" and "illegitimate" children.

Settlements and architecture

For most of the Gaelic period, dwellings and farm buildings were circular with conical thatched roofs (see roundhouse). Square and rectangle-shaped buildings gradually became more common, and by the 14th or 15th century they had replaced round buildings completely. In some areas, buildings were made mostly of stone. In others, they were built of timber,

For most of the Gaelic period, dwellings and farm buildings were circular with conical thatched roofs (see roundhouse). Square and rectangle-shaped buildings gradually became more common, and by the 14th or 15th century they had replaced round buildings completely. In some areas, buildings were made mostly of stone. In others, they were built of timber, wattle and daub

Wattle and daub is a composite building method used for making walls and buildings, in which a woven lattice of wooden strips called wattle is daubed with a sticky material usually made of some combination of wet soil, clay, sand, animal dung a ...

, or a mix of materials. Most ancient and early medieval stone buildings were of dry stone

Dry stone, sometimes called drystack or, in Scotland, drystane, is a building method by which structures are constructed from stones without any mortar to bind them together. Dry stone structures are stable because of their construction m ...

construction. Some buildings would have had glass windows. Among the wealthy, it was common for women to have their own 'apartment' called a ''grianan'' (anglicized "greenan") in the sunniest part of the homestead.

The dwellings of freemen and their families were often surrounded by a circular rampart

A circular rampart (German: ''Ringwall'') is an embankment built in the shape of a circle that was used as part of the defences for a military fortification, hill fort or refuge, or was built for religious purposes or as a place of gathering.

The ...

called a " ringfort". There are two main kinds of ringfort. The ''ráth'' is an earthen ringfort, averaging 30m diameter, with a dry outside ditch. The ''cathair'' or ''caiseal'' is a stone ringfort. The ringfort would typically have enclosed the family home, small farm buildings or workshops, and animal pens. Most date to the period 500–1000 CE and there is evidence of large-scale ringfort desertion at the end of the first millennium. The remains of between 30,000 and 40,000 lasted into the 19th century to be mapped by Ordnance Survey Ireland. Another kind of native dwelling was the ''crannóg

A crannog (; ga, crannóg ; gd, crannag ) is typically a partially or entirely artificial island, usually built in lakes and estuarine waters of Scotland, Wales, and Ireland. Unlike the prehistoric pile dwellings around the Alps, which were bu ...

'', which were roundhouses built on artificial islands in lakes.

There were very few nucleated settlements, but after the 5th century some monasteries

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which ...

became the heart of small "monastic towns". By the 10th century the Norse-Gaelic ports of Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 c ...

, Wexford

Wexford () is the county town of County Wexford, Ireland. Wexford lies on the south side of Wexford Harbour, the estuary of the River Slaney near the southeastern corner of the island of Ireland. The town is linked to Dublin by the M11/N11 ...

, Cork and Limerick

Limerick ( ; ga, Luimneach ) is a western city in Ireland situated within County Limerick. It is in the province of Munster and is located in the Mid-West which comprises part of the Southern Region. With a population of 94,192 at the 2016 ...

had grown into substantial settlements, all ruled by Gaelic kings by 1052. In this era many of the Irish round tower

Irish round towers ( ga, Cloigtheach (singular), (plural); literally 'bell house') are early mediaeval stone towers of a type found mainly in Ireland, with two in Scotland and one on the Isle of Man. As their name indicates, they were origin ...

s were built.

In the fifty years before the Norman invasion

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Normans, Norman, Duchy of Brittany, Breton, County of Flanders, Flemish, and Kingdom of France, French troops, ...

, the term "castle" ( sga, caistél/caislén) appears in Gaelic writings, although there are few intact surviving examples of pre-Norman castles. After the invasion, the Normans built motte-and-bailey castle

A motte-and-bailey castle is a European fortification with a wooden or stone keep situated on a raised area of ground called a motte, accompanied by a walled courtyard, or bailey, surrounded by a protective ditch and palisade. Relatively easy t ...

s in the areas they occupied, some of which were converted from ringforts. By 1300 "some mottes, especially in frontier areas, had almost certainly been built by the Gaelic Irish in imitation". The Normans gradually replaced wooden motte-and-baileys with stone castles and tower house

A tower house is a particular type of stone structure, built for defensive purposes as well as habitation. Tower houses began to appear in the Middle Ages, especially in mountainous or limited access areas, in order to command and defend strateg ...

s. Tower houses are free-standing multi-storey stone towers usually surrounded by a wall (see bawn) and ancillary buildings. Gaelic families had begun to build their own tower houses by the 15th century. As many as 7000 may have been built, but they were rare in areas with little Norman settlement or contact. They are concentrated in counties Limerick and Clare but are lacking in Ulster, except the area around Strangford Lough

Strangford Lough (from Old Norse ''Strangr Fjörðr'', meaning "strong sea-inlet"PlaceNames N ...

.

In Gaelic law, a 'sanctuary' called a ''maighin digona'' surrounded each person's dwelling. The ''maighin digona's'' size varied according to the owner's rank. In the case of a '' bóaire'' it stretched as far as he, while sitting at his house, could cast a ''cnairsech'' (variously described as a spear or sledgehammer). The owner of a ''maighin digona'' could offer its protection to someone fleeing from pursuers, who would then have to bring that person to justice by lawful means.

Economy

Gaelic Ireland was involved intrade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct excha ...

with Britain and mainland Europe from ancient times

Ancient history is a time period from the beginning of writing and recorded human history to as far as late antiquity. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the Sumerian cuneiform script. Ancient history cov ...

, and this trade increased over the centuries. Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

, for example, wrote in the 1st century that most of Ireland's harbours were known to the Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

through commerce. There are many passages in early Irish literature that mention luxury goods imported from foreign lands, and the fair of Carman in Leinster

Leinster ( ; ga, Laighin or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, situated in the southeast and east of Ireland. The province comprises the ancient Kingdoms of Meath, Leinster and Osraige. Following the 12th-century Norman invasion of ...

included a market of foreign traders. In the Middle Ages the main exports were textile

Textile is an umbrella term that includes various fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, filaments, threads, different fabric types, etc. At first, the word "textiles" only referred to woven fabrics. However, weaving is not the ...

s such as wool

Wool is the textile fibre obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have properties similar to animal wool. ...

and linen while the main imports were luxury items.

Money

Money is any item or verifiable record that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular country or socio-economic context. The primary functions which distinguish money are as ...

was seldom used in Gaelic society; instead, goods and services were usually exchanged for other goods and services (barter

In trade, barter (derived from ''baretor'') is a system of exchange in which participants in a transaction directly exchange goods or services for other goods or services without using a medium of exchange, such as money. Economists disti ...

). The economy was mainly a pastoral one, based on livestock (cow

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus ''Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult ma ...

s, sheep

Sheep or domestic sheep (''Ovis aries'') are domesticated, ruminant mammals typically kept as livestock. Although the term ''sheep'' can apply to other species in the genus '' Ovis'', in everyday usage it almost always refers to domesticated ...

, pig

The pig (''Sus domesticus''), often called swine, hog, or domestic pig when distinguishing from other members of the genus '' Sus'', is an omnivorous, domesticated, even-toed, hoofed mammal. It is variously considered a subspecies of ''Sus ...

s, goat

The goat or domestic goat (''Capra hircus'') is a domesticated species of goat-antelope typically kept as livestock. It was domesticated from the wild goat (''C. aegagrus'') of Southwest Asia and Eastern Europe. The goat is a member of the a ...

s, etc.) and their products. Cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus ''Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult ma ...

was "the main element in the Irish pastoral economy" and the main form of wealth

Wealth is the abundance of valuable financial assets or physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions. This includes the core meaning as held in the originating Old English word , which is from an I ...

, providing milk

Milk is a white liquid food produced by the mammary glands of mammals. It is the primary source of nutrition for young mammals (including breastfed human infants) before they are able to digest solid food. Immune factors and immune-modula ...

, butter

Butter is a dairy product made from the fat and protein components of churned cream. It is a semi-solid emulsion at room temperature, consisting of approximately 80% butterfat. It is used at room temperature as a spread, melted as a condimen ...

, cheese, meat, fat

In nutrition, biology, and chemistry, fat usually means any ester of fatty acids, or a mixture of such compounds, most commonly those that occur in living beings or in food.

The term often refers specifically to triglycerides (triple est ...

, hides, and so forth. They were a "highly mobile form of wealth and economic resource which could be quickly and easily moved to a safer locality in time of war or trouble". The nobility owned great herds of cattle that had herdsmen and guards. Sheep, goats and pigs were also a valuable resource but had a lesser role in Irish pastoralism.

Horticulture

Horticulture is the branch of agriculture that deals with the art, science, technology, and business of plant cultivation. It includes the cultivation of fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, herbs, sprouts, mushrooms, algae, flowers, seaweeds and no ...

was practised; the main crops being oat

The oat (''Avena sativa''), sometimes called the common oat, is a species of cereal grain grown for its seed, which is known by the same name (usually in the plural, unlike other cereals and pseudocereals). While oats are suitable for human con ...

s, wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeologi ...

and barley

Barley (''Hordeum vulgare''), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains, particularly in Eurasia as early as 10,000 years ago. Globally 70% of barley p ...

, although flax was also grown for making linen.

Transhumance

Transhumance is a type of pastoralism or nomadism, a seasonal movement of livestock between fixed summer and winter pastures. In montane regions (''vertical transhumance''), it implies movement between higher pastures in summer and lower val ...

was also practised, whereby people moved with their livestock to higher pasture

Pasture (from the Latin ''pastus'', past participle of ''pascere'', "to feed") is land used for grazing. Pasture lands in the narrow sense are enclosed tracts of farmland, grazed by domesticated livestock, such as horses, cattle, sheep, or sw ...

s in summer and back to lower pastures in the cooler months. The summer pasture was called the ''buaile'' (anglicized as ''booley'') and it is noteworthy that the Irish word for ''boy'' (''buachaill'') originally meant a herdsman. Many moorland areas were "shared as a common summer pasturage by the people of a whole parish or barony".

Transport

Gaelic Ireland was well furnished with roads and bridges. Bridges were typically wooden and in some places the roads were laid with wood and stone. There were five main roads leading from Tara: Slíghe Asail, Slíghe Chualann, Slíghe Dála, Slíghe Mór and Slíghe Midluachra. Horses were one of the main means of long-distance transport. Although horseshoes andrein

Reins are items of horse tack, used to direct a horse or other animal used for riding. They are long straps that can be made of leather, nylon, metal, or other materials, and attach to a bridle via either its bit or its noseband.

Use f ...

s were used, the Gaelic Irish did not use saddle

The saddle is a supportive structure for a rider of an animal, fastened to an animal's back by a girth. The most common type is equestrian. However, specialized saddles have been created for oxen, camels and other animals. It is not k ...

s, stirrups or spur

A spur is a metal tool designed to be worn in pairs on the heels of riding boots for the purpose of directing a horse or other animal to move forward or laterally while riding. It is usually used to refine the riding aids (commands) and to ba ...

s. Every man was trained to spring from the ground on to the back of his horse (an ''ech-léim'' or "steed-leap") and they urged-on and guided their horses with a rod having a hooked goad at the end.

Two-wheeled and four-wheeled chariots (singular ''carbad'') were used in Ireland from ancient times, both in private life and in war. They were big enough for two people, made of wickerwork and wood, and often had decorated hoods. The wheels were spoked, shod all round with iron, and were from three to four and a half feet high. Chariots were generally drawn by horses or oxen, with horse-drawn chariots being more common among chiefs and military men. War chariots furnished with scythes

Scythes ( grc, Σκύθης, ''Skýthi̱s'') was tyrant or ruler of Zancle in Sicily. He was appointed to that post in about 494 BC by Hippocrates of Gela.

The Zanclaeans had contacted Ionian leaders to invite colonists to join them in founding a ...

and spikes, like those of the ancient Gauls

The Gauls ( la, Galli; grc, Γαλάται, ''Galátai'') were a group of Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age and the Roman period (roughly 5th century BC to 5th century AD). Their homeland was known as Gaul (''Gallia''). They s ...

and Britons

British people or Britons, also known colloquially as Brits, are the citizens of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the British Overseas Territories, and the Crown dependencies.: British nationality law governs mod ...

, are mentioned in literature.

Boats used in Gaelic Ireland include canoe

A canoe is a lightweight narrow water vessel, typically pointed at both ends and open on top, propelled by one or more seated or kneeling paddlers facing the direction of travel and using a single-bladed paddle.

In British English, the ter ...

s, currach

A currach ( ) is a type of Irish boat with a wooden frame, over which animal skins or hides were once stretched, though now canvas is more usual. It is sometimes anglicised as "curragh".

The construction and design of the currach are unique ...

s, sailboat

A sailboat or sailing boat is a boat propelled partly or entirely by sails and is smaller than a sailing ship. Distinctions in what constitutes a sailing boat and ship vary by region and maritime culture.

Types

Although sailboat terminolo ...

s and Irish galleys. Ferryboats were used to cross wide rivers and are often mentioned in the Brehon Law

Early Irish law, historically referred to as (English: Freeman-ism) or (English: Law of Freemen), also called Brehon law, comprised the statutes which governed everyday life in Early Medieval Ireland. They were partially eclipsed by the Norma ...

s as subject to strict regulations. Sometimes they were owned by individuals and sometimes they were the common property of those living round the ferry. Large boats were used for trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct excha ...

with mainland Europe.

Dress

Throughout the Middle Ages, the common clothing amongst the Gaelic Irish consisted of a ''brat'' (a woollen semi circular cloak) worn over a ''léine'' (a loose-fitting, long-sleeved tunic made of linen). For men the ''léine'' reached to their ankles but was hitched up by means of a crios (pronounced 'kriss') which was a type of woven belt. The léine was hitched up to knee level. Women wore the léine at full length. Men sometimes wore tight-fitting trews (Gaelic triúbhas) but otherwise went bare-legged. The ''brat'' was simply thrown over both shoulders or sometimes over only one. Occasionally the brat was fastened with a ''dealg'' (

Throughout the Middle Ages, the common clothing amongst the Gaelic Irish consisted of a ''brat'' (a woollen semi circular cloak) worn over a ''léine'' (a loose-fitting, long-sleeved tunic made of linen). For men the ''léine'' reached to their ankles but was hitched up by means of a crios (pronounced 'kriss') which was a type of woven belt. The léine was hitched up to knee level. Women wore the léine at full length. Men sometimes wore tight-fitting trews (Gaelic triúbhas) but otherwise went bare-legged. The ''brat'' was simply thrown over both shoulders or sometimes over only one. Occasionally the brat was fastened with a ''dealg'' (brooch

A brooch (, also ) is a decorative jewelry item designed to be attached to garments, often to fasten them together. It is usually made of metal, often silver or gold or some other material. Brooches are frequently decorated with enamel or with g ...

), with men usually wearing the ''dealg'' at their shoulders and women at their chests. The ''ionar'' (a short, tight-fitting jacket) became popular later on. In ''Topographia Hibernica

''Topographia Hibernica'' (Latin for ''Topography of Ireland''), also known as ''Topographia Hiberniae'', is an account of the landscape and people of Ireland written by Gerald of Wales around 1188, soon after the Norman invasion of Ireland ...

'', written during the 1180s, Gerald de Barri wrote that the Irish commonly wore hoods at that time (perhaps forming part of the ''brat''), while Edmund Spenser wrote in the 1580s that the ''brat'' was (in general) their main item of clothing. Gaelic clothing does not appear to have been influenced by outside styles.

Women invariably grew their hair long and, as in other European cultures, this custom was also common among the men. It is said that the Gaelic Irish took great pride in their long hair

Long hair is a hairstyle where the head hair is allowed to grow to a considerable length. Exactly what constitutes long hair can change from culture to culture, or even within cultures. For example, a woman with chin-length hair in some cultures ...

—for example, a person could be forced to pay the heavy fine of two cows for shaving a man's head against his will. For women, very long hair was seen as a mark of beauty. Sometimes, wealthy men and women would braid their hair and fasten hollow golden balls to the braids. Another style that was popular among some medieval Gaelic men was the ''glib'' (short all over except for a long, thick lock of hair towards the front of the head). A band or ribbon around the forehead was the typical way of holding one's hair in place. For the wealthy, this band was often a thin and flexible band of burnished gold, silver or findruine. When the Anglo-Normans and the English colonized Ireland, hair length came to signify one's allegiance. Irishmen who cut their hair short were deemed to be forsaking their Irish heritage. Likewise, English colonists who grew their hair long at the back were deemed to be giving in to the Irish life.

Gaelic men typically wore a beard

A beard is the hair that grows on the jaw, chin, upper lip, lower lip, cheeks, and neck of humans and some non-human animals. In humans, usually pubescent or adult males are able to grow beards.

Throughout the course of history, societal at ...

and mustache

A moustache (; en-US, mustache, ) is a strip of facial hair grown above the upper lip. Moustaches have been worn in various styles throughout history.

Etymology

The word "moustache" is French, and is derived from the Italian ''mustaccio'' ( ...

, and it was often seen as dishonourable for a Gaelic man to have no facial hair. Beard styles varied – the long forked beard and the rectangular Mesopotamian-style beard were fashionable at times.

Warfare

Warfare

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regul ...

was common in Gaelic Ireland, as territories

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or a ...

, kingdoms

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 2007 British television drama s ...

and clans fought for supremacy against each other and later against the Vikings

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and ...

and Anglo-Normans

The Anglo-Normans ( nrf, Anglo-Normaunds, ang, Engel-Norðmandisca) were the medieval ruling class in England, composed mainly of a combination of ethnic Normans, French, Anglo-Saxons, Flemings and Bretons, following the Norman conquest. A sma ...

.

Champion warfare

Champion warfare refers to a type of battle, most commonly found in the epic poetry and myth of ancient history, in which the outcome of the conflict is determined by single combat, an individual duel between the best soldiers ("champions") f ...

is a common theme in Early Irish mythology

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not objectively true, the identification of a narra ...

, literature

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to include ...

and culture. In the Middle Ages all able-bodied men, apart from the learned and the clergy, were eligible for military service on behalf of the king

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

or chief. Throughout the Middle Ages and for some time after, outsiders often wrote that the Irish style of warfare differed greatly from what they deemed to be the norm in Western Europe. The Gaelic Irish preferred hit-and-run

In traffic laws, a hit and run or a hit-and-run is the act of causing a traffic collision and not stopping afterwards. It is considered a supplemental crime in most jurisdictions.

Additional obligation

In many jurisdictions, there may be an ...

raids (the ''crech''), which involved catching the enemy unaware. If this worked they would then seize any valuables (mainly livestock) and potentially valuable hostages, burn the crops, and escape. The cattle raid

Cattle raiding is the act of stealing cattle. In Australia, such stealing is often referred to as duffing, and the perpetrator as a duffer.Baker, Sidney John (1945) ''The Australian language : an examination of the English language and English ...

was a social institution

Institutions are humanly devised structures of rules and norms that shape and constrain individual behavior. All definitions of institutions generally entail that there is a level of persistence and continuity. Laws, rules, social conventions a ...

and was called a ''Táin Bó

The ''Táin Bó'', or cattle raid (literally "driving-off of cows"), is one of the genres of early Irish literature. The medieval Irish literati organised their work into genres such as the Cattle Raid (''Táin Bó''), adventure ('' Echtra''), the ...

'' in Gaelic literature. Although hit-and-run raiding was the preferred tactic in medieval times, there were also pitched battle

A pitched battle or set-piece battle is a battle in which opposing forces each anticipate the setting of the battle, and each chooses to commit to it. Either side may have the option to disengage before the battle starts or shortly thereafter. A ...