Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

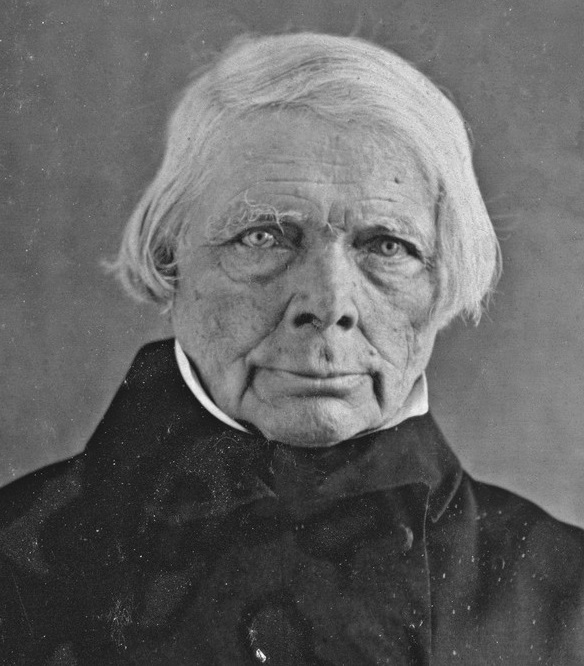

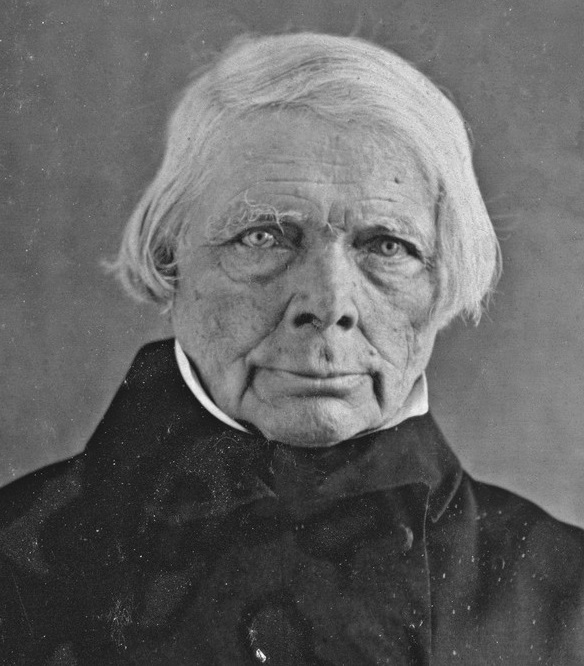

Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling (; 27 January 1775 – 20 August 1854), later (after 1812) von Schelling, was a

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

. Standard histories of philosophy make him the midpoint in the development of German idealism

German idealism was a philosophical movement that emerged in Germany in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It developed out of the work of Immanuel Kant in the 1780s and 1790s, and was closely linked both with Romanticism and the revolutiona ...

, situating him between Johann Gottlieb Fichte

Johann Gottlieb Fichte (; ; 19 May 1762 – 29 January 1814) was a German philosopher who became a founding figure of the philosophical movement known as German idealism

German idealism was a philosophical movement that emerged in Germany in ...

, his mentor in his early years, and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (; ; 27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a German philosopher. He is one of the most important figures in German idealism and one of the founding figures of modern Western philosophy. His influence extends ...

, his one-time university roommate, early friend, and later rival. Interpreting Schelling's philosophy is regarded as difficult because of its evolving nature.

Schelling's thought in the main has been neglected, especially in the English-speaking world

Speakers of English are also known as Anglophones, and the countries where English is natively spoken by the majority of the population are termed the '' Anglosphere''. Over two billion people speak English , making English the largest languag ...

. An important factor in this was the ascendancy of Hegel, whose mature works portray Schelling as a mere footnote in the development of idealism. Schelling's ''Naturphilosophie

''Naturphilosophie'' (German for "nature-philosophy") is a term used in English-language philosophy to identify a current in the philosophical tradition of German idealism, as applied to the study of nature in the earlier 19th century. German s ...

'' also has been attacked by scientists for its tendency to analogize and lack of empirical

Empirical evidence for a proposition is evidence, i.e. what supports or counters this proposition, that is constituted by or accessible to sense experience or experimental procedure. Empirical evidence is of central importance to the sciences and ...

orientation. However, some later philosophers have shown interest in re-examining Schelling's body of work.

Life

Early life

Schelling was born in the town ofLeonberg

Leonberg (; swg, Leaberg) is a town in the German federal state of Baden-Württemberg about to the west of Stuttgart, the state capital. About 45,000 people live in Leonberg, making it the third-largest borough in the rural district (''Landkr ...

in the Duchy of Württemberg

The Duchy of Württemberg (german: Herzogtum Württemberg) was a duchy located in the south-western part of the Holy Roman Empire. It was a member of the Holy Roman Empire from 1495 to 1806. The dukedom's long survival for over three centuries ...

(now Baden-Württemberg

Baden-Württemberg (; ), commonly shortened to BW or BaWü, is a German state () in Southwest Germany, east of the Rhine, which forms the southern part of Germany's western border with France. With more than 11.07 million inhabitants across a ...

), the son of Joseph Friedrich Schelling and Gottliebin Marie. He attended the monastic school

Monastic schools ( la, Scholae monasticae) were, along with cathedral schools, the most important institutions of higher learning in the Latin West from the early Middle Ages until the 12th century. Since Cassiodorus's educational program, the st ...

at Bebenhausen

Bebenhausen is a village (pop. 347) in the Tübingen district, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. Since 1974 it is a district of the city of Tübingen, its least populous one. It is located 3 km north of Tübingen proper (about 5 km northeast of the c ...

, near Tübingen

Tübingen (, , Swabian: ''Dibenga'') is a traditional university city in central Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is situated south of the state capital, Stuttgart, and developed on both sides of the Neckar and Ammer rivers. about one in three ...

, where his father was chaplain and an Orientalist professor. From 1783 to 1784 Schelling attended a Latin school in Nürtingen

Nürtingen () is a town on the river Neckar in the district of Esslingen in the state of Baden-Württemberg in southern Germany.

History

The following events occurred, by year:

*1046: First mention of ''Niuritingin'' in the document of Speyer ...

and knew Friedrich Hölderlin

Johann Christian Friedrich Hölderlin (, ; ; 20 March 1770 – 7 June 1843) was a German poet and philosopher. Described by Norbert von Hellingrath as "the most German of Germans", Hölderlin was a key figure of German Romanticism. Part ...

, who was five years his senior. On 18 October 1790, at the age of 15, he was granted permission to enroll at the Tübinger Stift (seminary of the Evangelical-Lutheran Church in Württemberg), despite not having yet reached the normal enrollment age of 20. At the Stift, he shared a room with Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (; ; 27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a German philosopher. He is one of the most important figures in German idealism and one of the founding figures of modern Western philosophy. His influence extends a ...

as well as Hölderlin, and the three became good friends.

Schelling studied the Church fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical per ...

and ancient Greek philosophers

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC, marking the end of the Greek Dark Ages. Greek philosophy continued throughout the Hellenistic period and the period in which Greece and most Greek-inhabited lands were part of the Roman Empire ...

. His interest gradually shifted from Lutheran theology

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

to philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. ...

. In 1792 he graduated with his master's thesis

A thesis ( : theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144: ...

, titled ''Antiquissimi de prima malorum humanorum origine philosophematis Genes. III. explicandi tentamen criticum et philosophicum'', and in 1795 he finished his doctoral thesis, titled ''De Marcione Paulinarum epistolarum emendatore'' (''On Marcion

Marcion of Sinope (; grc, Μαρκίων ; ) was an early Christian theologian in early Christianity. Marcion preached that God had sent Jesus Christ who was an entirely new, alien god, distinct from the vengeful God of Israel who had created ...

as emendator of the Pauline letters'') under Gottlob Christian Storr. Meanwhile, he had begun to study Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and aest ...

and Fichte, who influenced him greatly. Representative of Schelling´s early period is also a discourse between him and the philosophical writer , who was Fichte´s housemate at that time, in letters and in Fichte´s Journal (1796/97) on ''interaction'', ''the pragmatic'' and Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz . ( – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat. He is one of the most prominent figures in both the history of philosophy and the history of ma ...

.

In 1797, while tutoring two youths of an aristocratic family, he visited Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as ...

as their escort and had a chance to attend lectures at Leipzig University

Leipzig University (german: Universität Leipzig), in Leipzig in Saxony, Germany, is one of the world's oldest universities and the second-oldest university (by consecutive years of existence) in Germany. The university was founded on 2 December ...

, where he was fascinated by contemporary physical studies including chemistry and biology. He also visited Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label= Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth ...

, where he saw collections of the Elector of Saxony

The Electorate of Saxony, also known as Electoral Saxony (German: or ), was a territory of the Holy Roman Empire from 1356–1806. It was centered around the cities of Dresden, Leipzig and Chemnitz.

In the Golden Bull of 1356, Emperor Charles ...

, to which he referred later in his thinking on art. On a personal level, this Dresden visit of six weeks from August 1797 saw Schelling meet the brothers August Wilhelm Schlegel and Karl Friedrich Schlegel

Karl Wilhelm Friedrich (after 1814: von) Schlegel (; ; 10 March 1772 – 12 January 1829) was a German poet, literary critic, philosopher, philologist, and Indologist. With his older brother, August Wilhelm Schlegel, he was one of the main figures ...

and his future wife Caroline (then married to August Wilhelm), and Novalis

Georg Philipp Friedrich Freiherr von Hardenberg (2 May 1772 – 25 March 1801), pen name Novalis (), was a German polymath who was a writer, philosopher, poet, aristocrat and mystic. He is regarded as an idiosyncratic and influential figure o ...

.

Jena period

After two years tutoring, in October 1798, at the age of 23, Schelling was called toUniversity of Jena

The University of Jena, officially the Friedrich Schiller University Jena (german: Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, abbreviated FSU, shortened form ''Uni Jena''), is a public research university located in Jena, Thuringia, Germany.

The ...

as an extraordinary (i.e., unpaid) professor of philosophy. His time at Jena (1798–1803) put Schelling at the centre of the intellectual ferment of Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

. He was on close terms with Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as t ...

, who appreciated the poetic quality of the ''Naturphilosophie

''Naturphilosophie'' (German for "nature-philosophy") is a term used in English-language philosophy to identify a current in the philosophical tradition of German idealism, as applied to the study of nature in the earlier 19th century. German s ...

'', reading ''Von der Weltseele''. As the prime minister of the Duchy of Saxe-Weimar

Saxe-Weimar (german: Sachsen-Weimar) was one of the Saxon duchies held by the Ernestine branch of the Wettin dynasty in present-day Thuringia. The chief town and capital was Weimar. The Weimar branch was the most genealogically senior extant ...

, Goethe invited Schelling to Jena. On the other hand, Schelling was unsympathetic to the ethical idealism that animated the work of Friedrich Schiller

Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller (, short: ; 10 November 17599 May 1805) was a German playwright, poet, and philosopher. During the last seventeen years of his life (1788–1805), Schiller developed a productive, if complicated, friendsh ...

, the other pillar of Weimar Classicism

Weimar Classicism (german: Weimarer Klassik) was a German literary and cultural movement, whose practitioners established a new humanism from the synthesis of ideas from Romanticism, Classicism, and the Age of Enlightenment. It was named after ...

. Later, in Schelling's ''Vorlesung über die Philosophie der Kunst'' (''Lecture on the Philosophy of Art'', 1802/03), Schiller's theory on the sublime was closely reviewed.

In Jena, Schelling was on good terms with Fichte at first, but their different conceptions, about nature in particular, led to increasing divergence. Fichte advised him to focus on transcendental philosophy: specifically, Fichte's own ''Wissenschaftlehre''. But Schelling, who was becoming the acknowledged leader of the Romantic school, rejected Fichte's thought as cold and abstract.

Schelling was especially close to August Wilhelm Schlegel and his wife, Caroline

Caroline may refer to:

People

*Caroline (given name), a feminine given name

* J. C. Caroline (born 1933), American college and National Football League player

* Jordan Caroline (born 1996), American (men's) basketball player

Places Antarctica

* ...

. A marriage between Schelling and Caroline's young daughter, Auguste Böhmer, was contemplated by both. Auguste died of dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

in 1800, prompting many to blame Schelling, who had overseen her treatment. Robert Richards, however, argues in his book ''The Romantic Conception of Life'' that Schelling's interventions were most likely irrelevant, as the doctors called to the scene assured everyone involved that Auguste's disease was inevitably fatal. Auguste's death drew Schelling and Caroline closer. Schlegel had moved to Berlin, and a divorce was arranged with Goethe's help. Schelling's time at Jena came to an end, and on 2 June 1803 he and Caroline were married away from Jena. Their marriage ceremony was the last occasion Schelling met his school friend the poet Friedrich Hölderlin

Johann Christian Friedrich Hölderlin (, ; ; 20 March 1770 – 7 June 1843) was a German poet and philosopher. Described by Norbert von Hellingrath as "the most German of Germans", Hölderlin was a key figure of German Romanticism. Part ...

, who was already mentally ill at that time.

In his Jena period, Schelling had a closer relationship with Hegel again. With Schelling's help, Hegel became a private lecturer (''Privatdozent'') at Jena University

The University of Jena, officially the Friedrich Schiller University Jena (german: Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, abbreviated FSU, shortened form ''Uni Jena''), is a public research university located in Jena, Thuringia, Germany.

Th ...

. Hegel wrote a book titled ''Differenz des Fichte'schen und Schelling'schen Systems der Philosophie'' (''Difference between Fichte's and Schelling's Systems of Philosophy'', 1801), and supported Schelling's position against his idealistic predecessors, Fichte and Karl Leonhard Reinhold. Beginning in January 1802, Hegel and Schelling published the ''Kritisches Journal der Philosophie'' (''Critical Journal of Philosophy'') as co-editors, publishing papers on the philosophy of nature, but Schelling was too busy to stay involved with the editing and the magazine was mainly Hegel's publication, espousing a thought different from Schelling's. The magazine ceased publication in the spring of 1803 when Schelling moved from Jena to Würzburg

Würzburg (; Main-Franconian: ) is a city in the region of Franconia in the north of the German state of Bavaria. Würzburg is the administrative seat of the ''Regierungsbezirk'' Lower Franconia. It spans the banks of the Main River.

Würzburg ...

.

Move to Würzburg and personal conflicts

After Jena, Schelling went toBamberg

Bamberg (, , ; East Franconian: ''Bambärch'') is a town in Upper Franconia, Germany, on the river Regnitz close to its confluence with the river Main. The town dates back to the 9th century, when its name was derived from the nearby ' castl ...

for a time, to study Brunonian medicine (the theory of John Brown) with and Andreas Röschlaub

Andreas Röschlaub (21 October 1768 – 7 July 1835) was a German physician born in Lichtenfels, Bavaria.

He studied medicine at the Universities of Würzburg and Bamberg, gaining his doctorate at the latter institution in 1795. In 1798 he became ...

. From September 1803 until April 1806 Schelling was professor at the new University of Würzburg

The Julius Maximilian University of Würzburg (also referred to as the University of Würzburg, in German ''Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg'') is a public research university in Würzburg, Germany. The University of Würzburg is one of ...

. This period was marked by considerable flux in his views and by a final breach with Fichte and Hegel.

In Würzburg, a conservative Catholic city, Schelling found many enemies among his colleagues and in the government. He moved then to Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and ...

in 1806, where he found a position as a state official, first as associate of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities

The Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities (german: Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften) is an independent public institution, located in Munich. It appoints scholars whose research has contributed considerably to the increase of knowledg ...

and secretary of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, afterwards as secretary of the Philosophische Klasse (philosophical section) of the Academy of Sciences. 1806 was also the year Schelling published a book in which he criticized Fichte openly by name. In 1807 Schelling received the manuscript of Hegel's ''Phaenomenologie des Geistes

''The Phenomenology of Spirit'' (german: Phänomenologie des Geistes) is the most widely-discussed philosophical work of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel; its German title can be translated as either ''The Phenomenology of Spirit'' or ''The Phenomen ...

'' (''Phenomenology of the Spirit'' or ''Mind''), which Hegel had sent to him, asking Schelling to write the foreword. Surprised to find critical remarks directed at his own philosophical theory, Schelling wrote back, asking Hegel to clarify whether he had intended to mock Schelling's followers who lacked a true understanding of his thought, or Schelling himself. Hegel never replied. In the same year, Schelling gave a speech about the relation between the visual arts and nature at the Academy of Fine Arts; Hegel wrote a severe criticism of it to one of his friends. After that, they criticized each other in lecture rooms and in books publicly until the end of their lives.

Munich period

Without resigning his official position in Munich, he lectured for a short time inStuttgart

Stuttgart (; Swabian: ; ) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Baden-Württemberg. It is located on the Neckar river in a fertile valley known as the ''Stuttgarter Kessel'' (Stuttgart Cauldron) and lies an hour from the Sw ...

(''Stuttgarter Privatvorlesungen'' tuttgart private lectures 1810), and seven years at the University of Erlangen (1820–1827). In 1809 Karoline died, just before he published ''Freiheitsschrift'' (''Freedom Essay'') the last book published during his life. Three years later, Schelling married one of her closest friends, Pauline Gotter, in whom he found a faithful companion.

During the long stay in Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and ...

(1806–1841) Schelling's literary activity came gradually to a standstill. It is possible that it was the overpowering strength and influence of the Hegelian system that constrained Schelling, for it was only in 1834, after the death of Hegel, that, in a preface to a translation by Hubert Beckers of a work by Victor Cousin

Victor Cousin (; 28 November 179214 January 1867) was a French philosopher. He was the founder of " eclecticism", a briefly influential school of French philosophy that combined elements of German idealism and Scottish Common Sense Realism. ...

, he gave public utterance to the antagonism in which he stood to the Hegelian, and to his own earlier, conception of philosophy. The antagonism certainly was not new; the 1822 Erlangen lectures on the history of philosophy expressed the same in a pointed fashion, and Schelling had already begun the treatment of mythology

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not objectively true, the identification of a narra ...

and religion

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatur ...

which, in his view, constituted the true positive complements to the negative of logical or speculative philosophy.

Berlin period

Public attention was powerfully attracted by hints of a new system which promised something more positive, especially in its treatment of religion, than the apparent results of Hegel's teaching. The appearance of critical writings by David Friedrich Strauss,Ludwig Feuerbach

Ludwig Andreas von Feuerbach (; 28 July 1804 – 13 September 1872) was a German anthropologist and philosopher, best known for his book '' The Essence of Christianity'', which provided a critique of Christianity that strongly influenced gene ...

, and Bruno Bauer

Bruno Bauer (; 6 September 180913 April 1882) was a German philosopher and theologian. As a student of G. W. F. Hegel, Bauer was a radical Rationalist in philosophy, politics and Biblical criticism. Bauer investigated the sources of the New Te ...

, and the disunion in the Hegelian school itself, expressed a growing alienation from the then dominant philosophy. In Berlin, the headquarters of the Hegelians, this found expression in attempts to obtain officially from Schelling a treatment of the new system that he was understood to have in reserve. Its realization did not come about until 1841, when Schelling's appointment as Prussian privy councillor and member of the Berlin Academy, gave him the right, a right he was requested to exercise, to deliver lectures in the university. Among those in attendance at his lectures were Søren Kierkegaard

Søren Aabye Kierkegaard ( , , ; 5 May 1813 – 11 November 1855) was a Danish theologian, philosopher, poet, social critic, and religious author who is widely considered to be the first existentialist philosopher. He wrote critical texts on ...

(who said Schelling talked "quite insufferable nonsense" and complained that he did not end his lectures on time), Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (; 1814–1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary s ...

(who called them "interesting but rather insignificant"), Jacob Burckhardt

Carl Jacob Christoph Burckhardt (25 May 1818 – 8 August 1897) was a Swiss historian of art and culture and an influential figure in the historiography of both fields. He is known as one of the major progenitors of cultural history. Sigfri ...

, Alexander von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (14 September 17696 May 1859) was a German polymath, geographer, naturalist, explorer, and proponent of Romantic philosophy and science. He was the younger brother of the Prussian minister ...

(who never accepted Schelling's natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancien ...

), future church historian Philip Schaff and Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ,"Engels"

'' H. E. G. Paulus, sharpened by Schelling's success, led to surreptitious publication of a verbatim report of the lectures on the philosophy of revelation. Schelling did not succeed in obtaining legal condemnation and suppression of this piracy and he stopped delivering public lectures in 1845.

In 1793 Schelling contributed to Heinrich Eberhard Gottlob Paulus's periodical ''Memorabilien''. His 1795 dissertation was ''De Marcione Paullinarum epistolarum emendatore'' (''On

In 1793 Schelling contributed to Heinrich Eberhard Gottlob Paulus's periodical ''Memorabilien''. His 1795 dissertation was ''De Marcione Paullinarum epistolarum emendatore'' (''On

'' H. E. G. Paulus, sharpened by Schelling's success, led to surreptitious publication of a verbatim report of the lectures on the philosophy of revelation. Schelling did not succeed in obtaining legal condemnation and suppression of this piracy and he stopped delivering public lectures in 1845.

Works

In 1793 Schelling contributed to Heinrich Eberhard Gottlob Paulus's periodical ''Memorabilien''. His 1795 dissertation was ''De Marcione Paullinarum epistolarum emendatore'' (''On

In 1793 Schelling contributed to Heinrich Eberhard Gottlob Paulus's periodical ''Memorabilien''. His 1795 dissertation was ''De Marcione Paullinarum epistolarum emendatore'' (''On Marcion

Marcion of Sinope (; grc, Μαρκίων ; ) was an early Christian theologian in early Christianity. Marcion preached that God had sent Jesus Christ who was an entirely new, alien god, distinct from the vengeful God of Israel who had created ...

as emendator of the Pauline letters''). In 1794, Schelling published an exposition of Fichte's thought entitled ''Ueber die Möglichkeit einer Form der Philosophie überhaupt'' (''On the Possibility of a Form of Philosophy in General''). This work was acknowledged by Fichte himself and immediately earned Schelling a reputation among philosophers. His more elaborate work, ''Vom Ich als Prinzip der Philosophie, oder über das Unbedingte im menschlichen Wissen'' (''On Self as Principle of Philosophy, or on the Unrestricted in Human Knowledge'', 1795), while still remaining within the limits of the Fichtean idealism, showed a tendency to give the Fichtean method a more objective application, and to amalgamate Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (born Bento de Espinosa; later as an author and a correspondent ''Benedictus de Spinoza'', anglicized to ''Benedict de Spinoza''; 24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677) was a Dutch philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, ...

's views with it. He contributed articles and reviews to the ''Philosophisches Journal'' of Fichte and Friedrich Immanuel Niethammer

Friedrich Philipp Immanuel Niethammer (6 March 1766 – 1 April 1848), later Ritter von Niethammer, was a German theologian, philosopher and Lutheran educational reformer.

Biography

He received instruction at the Maulbronn monastery, and in 1 ...

, and threw himself into the study of physical and medical science. In 1795 Schelling published ''Philosophische Briefe über Dogmatismus und Kritizismus'' (''Philosophical Letters on Dogmatism and Criticism''), consisting of 10 letters addressed to an unknown interlocutor that presented both a defense and critique of the Kantian system.

Between 1796/97 there was written a seminal manuscript now known as the ''Das älteste Systemprogramm des deutschen Idealismus'' ("The Oldest Systematic Program of German Idealism "The Oldest Systematic Program of German Idealism" (german: Das älteste Systemprogramm des deutschen Idealismus) is a fragmentary 1796/97 essay of unknown authorship. The document was first published (in German) by Franz Rosenzweig in 1917. An Eng ...

"). It survives in Hegel's handwriting. First published in 1916 by Franz Rosenzweig

Franz Rosenzweig (, ; 25 December 1886 – 10 December 1929) was a German theologian, philosopher, and translator.

Early life and education

Franz Rosenzweig was born in Kassel, Germany, to an affluent, minimally observant Jewish family. His f ...

, it was attributed to Schelling. It has also been claimed that Hegel or Hölderlin was the author.Kai Hammermeister, ''The German Aesthetic Tradition'', Cambridge University Press, 2002, p. 76.

In 1797, Schelling published the essay ''Neue Deduction des Naturrechts'' ("New Deduction of Natural Law"), which anticipated Fichte's treatment of the topic in ''Grundlage des Naturrechts'' (''Foundations of Natural Law''). His studies of physical science bore fruit in ''Ideen zu einer Philosophie der Natur'' (''Ideas Concerning a Philosophy of Nature'', 1797), and the treatise ''Von der Weltseele'' (''On the World-Soul'', 1798). In ''Ideen'' Schelling referred to Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz . ( – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat. He is one of the most prominent figures in both the history of philosophy and the history of ma ...

and quoted from his '' Monadology''. He held Leibniz in high regard because of his view of nature during his natural philosophy period.

In 1800 Schelling published ''System des transcendentalen Idealismus'' ('' System of Transcendental Idealism''). In this book Schelling described transcendental philosophy and nature philosophy as complementary to one another. Fichte reacted by stating that Schelling's argument was unsound: in Fichte's theory nature as Not-Self (''Nicht-Ich'' = object) could not be a subject of philosophy, whose essential content is the subjective activity of the human intellect. The breach became unrecoverable in 1801 after Schelling published ''Darstellung des Systems meiner Philosophie'' ("Presentation of My System of Philosophy"). Fichte thought this title absurd since, in his opinion, philosophy could not be personalized. Moreover, in this book Schelling publicly expressed his estimation of Spinoza, whose work Fichte had repudiated as dogmatism, and declared that nature and spirit differ only in their quantity, but are essentially identical. According to Schelling, the absolute was the indifference to identity, which he considered to be an essential philosophical subject.

The "Aphorismen über die Naturphilosophie" ("Aphorisms on Nature Philosophy"), published in the ''Jahrbücher der Medicin als Wissenschaft'' (1805–1808), are for the most part extracts from the Würzburg lectures, and the ''Denkmal der Schrift von den göttlichen Dingen des Herrn Jacobi'' ("Monument to the Scripture of the Divine Things of Mr. Jacobi") was a response to an attack by Jacobi Jacobi may refer to:

* People with the surname Jacobi

Mathematics:

* Jacobi sum, a type of character sum

* Jacobi method, a method for determining the solutions of a diagonally dominant system of linear equations

* Jacobi eigenvalue algorithm, ...

(the two accused each other of atheism). A work of significance is the 1809 ''Philosophische Untersuchungen über das Wesen der menschlichen Freiheit und die damit zusammenhängenden Gegenstände'' ('' Philosophical Inquiries into the Essence of Human Freedom''), which elaborates, with increasing mysticism

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning. It may also refer to the attainment of insight in ...

, on ideas in the 1804 work ''Philosophie und Religion'' (''Philosophy and Religion''). However, in a change from the Jena period, evil is not an appearance coming from quantitative differences between the real and the ideal, but is something substantial. This work clearly paraphrased Kant's distinction between intelligible and empirical character. Schelling himself called freedom "a capacity for good and evil".

The 1815 essay ''Ueber die Gottheiten zu Samothrake'' ("On the Divinities of Samothrace

Samothrace (also known as Samothraki, el, Σαμοθράκη, ) is a Greek island in the northern Aegean Sea. It is a municipality within the Evros regional unit of Thrace. The island is long and is in size and has a population of 2,859 (2011 ...

") was ostensibly a part of a larger work, '' Weltalter'' ("The Ages of the World"), frequently announced as ready for publication, but of which little was ever written. Schelling planned ''Weltalter'' as a book in three parts, describing the past, present, and future of the world; however, he began only the first part, rewriting it several times and at last keeping it unpublished. The other two parts were left only in planning. Christopher John Murray describes the work as follows:Building on the premise that philosophy cannot ultimately explain existence, he merges the earlier philosophies of Nature and identity with his newfound belief in a fundamental conflict between a dark unconscious principle and a conscious principle in God. God makes the universe intelligible by relating to the ground of the real but, insofar as nature is not complete intelligence, the real exists as a lack within the ideal and not as reflective of the ideal itself. The three universal ages – distinct only to us but not in the eternal God – therefore comprise a beginning where the principle of God before God is divine will striving for being, the present age, which is still part of this growth and hence a mediated fulfillment, and a finality where God is consciously and consummately Himself to Himself.No authentic information on Schelling's new positive philosophy (''positive Philosophie'') was available until after his death at Bad Ragatz, on 20 August 1854. His sons then issued four volumes of his Berlin lectures: vol. i. ''Introduction to the Philosophy of Mythology'' (1856); ii. ''Philosophy of Mythology'' (1857); iii. and iv. ''Philosophy of Revelation'' (1858).

Periodization

Schelling, at all stages of his thought, called to his aid outward forms of some other system. Fichte, Spinoza, Jakob Boehme and the mystics, and finally, major Greek thinkers with theirNeoplatonic

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some id ...

, Gnostic

Gnosticism (from grc, γνωστικός, gnōstikós, , 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems which coalesced in the late 1st century AD among Jewish and early Christian sects. These various groups emphasized p ...

, and Scholastic commentators, give colouring to particular works. In Schelling's own view, his philosophy fell into three stages. These were:

#Transition from Fichte's philosophy to a more objective conception of nature (an advance to ''Naturphilosophie'')

#Formulation of the identical, indifferent, absolute substratum of both nature and spirit (''Identitätsphilosophie'').

#Opposition of negative and positive philosophy, which was the theme of his Berlin lectures, though the concepts can be traced back to 1804.

''Naturphilosophie''

The function of Schelling's ''Naturphilosophie'' is to exhibit the ideal as springing from the real. The change which experience brings before us leads to the conception of duality, the polar opposition through which nature expresses itself. The dynamic series of stages in nature are matter (as the equilibrium of the fundamental expansive) and contractive forces (light, with its subordinate processes of magnetism, electricity, and chemical action) and organism (with its component phases of reproduction, irritability and sensibility).Reputation and influence

Some scholars characterize Schelling as a protean thinker who, although brilliant, jumped from one subject to another and lacked the synthesizing power needed to arrive at a complete philosophical system. Others challenge the notion that Schelling's thought is marked by profound breaks, instead arguing that his philosophy always focused on a few common themes, especially human freedom, the absolute, and the relationship between spirit and nature. Unlike Hegel, Schelling did not believe that the absolute could be known in its true character through rational inquiry alone. Schelling is still studied, although his reputation has varied over time. His work impressed the English romantic poet and criticSamuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lak ...

, who introduced his ideas into English-speaking culture, sometimes without full acknowledgment, as in the ''Biographia Literaria

The ''Biographia Literaria'' is a critical autobiography by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, published in 1817 in two volumes. Its working title was 'Autobiographia Literaria'. The formative influences on the work were Wordsworth's theory of poetry, th ...

''. Coleridge's critical work was influential, and it was he who introduced into English literature Schelling's concept of the unconscious. Schelling's '' System of Transcendental Idealism'' has been seen as a precursor of Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( , ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies explained as originating in conflicts i ...

's '' Interpretation of Dreams'' (1899).

Up to 1950, Schelling was almost a forgotten philosopher even in Germany. In the 1910s and 1920s, philosophers of neo-Kantianism and neo-Hegelianism, like Wilhelm Windelband

Wilhelm Windelband (; ; 11 May 1848 – 22 October 1915) was a German philosopher of the Baden School.

Biography

Windelband was born the son of a Prussian official in Potsdam. He studied at Jena, Berlin, and Göttingen.

Philosophical work

Win ...

or Richard Kroner, tended to describe Schelling as an episode connecting Fichte and Hegel. His late period tended to be ignored, and his philosophies of nature and of art in the 1790s and first decade of the 19th century were the main focus. In this context Kuno Fischer

Ernst Kuno Berthold Fischer (23 July 1824 – 5 July 1907) was a German philosopher, a historian of philosophy and a critic.

Biography

After studying philosophy at Leipzig and Halle,

became a privatdocent at Heidelberg in 1850. The Baden gover ...

characterized Schelling's early philosophy as "aesthetic idealism", focusing on the argument where he ranked art as "the sole document and the eternal organ of philosophy" (''das einzige wahre und ewige Organon zugleich und Dokument der Philosophie''). From socialist philosophers like György Lukács

György Lukács (born György Bernát Löwinger; hu, szegedi Lukács György Bernát; german: Georg Bernard Baron Lukács von Szegedin; 13 April 1885 – 4 June 1971) was a Hungarian Marxist philosopher, literary historian, critic, and aesth ...

, he was regarded as anachronistic. An exception was Martin Heidegger

Martin Heidegger (; ; 26 September 188926 May 1976) was a German philosopher who is best known for contributions to phenomenology, hermeneutics, and existentialism. He is among the most important and influential philosophers of the 20th centu ...

, who found in Schelling's '' On Human Freedom'' central themes of Western ontology - being, existence, and freedom - and expounded on them in his 1936 lectures.

In the 1950s, the situation began to change. In 1954, the centennial of his death, an international conference on Schelling was held. Several philosophers, including Karl Jaspers

Karl Theodor Jaspers (, ; 23 February 1883 – 26 February 1969) was a German-Swiss psychiatrist and philosopher who had a strong influence on modern theology, psychiatry, and philosophy. After being trained in and practicing psychiatry, Jaspe ...

, gave presentations about the uniqueness and relevance of his thought, the interest shifting toward his later work on the origin of existence. Schelling was the subject of Jürgen Habermas

Jürgen Habermas (, ; ; born 18 June 1929) is a German social theorist in the tradition of critical theory and pragmatism. His work addresses communicative rationality and the public sphere.

Associated with the Frankfurt School, Habermas's wo ...

's 1954 dissertation.

In 1955 Jaspers published ''Schelling'', representing him as a forerunner of the existentialists and Walter Schulz, one of organizers of the 1954 conference, published "Die Vollendung des Deutschen Idealismus in der Spätphilosophie Schellings" ("The Perfection of German Idealism in Schelling's Late Philosophy") claiming that Schelling had made German idealism complete with his late philosophy, particularly with his Berlin lectures in the 1840s. Schulz presented Schelling as the person who resolved the philosophical problems which Hegel had left incomplete, in contrast to the contemporary idea that Schelling had been surpassed by Hegel much earlier. Theologian Paul Tillich

Paul Johannes Tillich (August 20, 1886 – October 22, 1965) was a German-American Christian existentialist philosopher, religious socialist, and Lutheran Protestant theologian who is widely regarded as one of the most influential theolo ...

wrote: "what I learned from Schelling became determinative of my own philosophical and theological development". Maurice Merleau-Ponty likened his own project of natural ontology to Schelling's in his 1957–58 Course on Nature.

In the 1970s nature was again of interest to philosophers in relation to environmental issues. Schelling's philosophy of nature, particularly his intention to construct a program which covers both nature and the intellectual life in a single system and method, and restore nature as a central theme of philosophy, has been reevaluated in the contemporary context. His influence and relation to the German art scene, particularly to Romantic literature and visual art, has been an interest since the late 1960s, from Philipp Otto Runge

Philipp Otto Runge (; 1777–1810) was a German artist, a draftsman, painter, and color theorist. Runge and Caspar David Friedrich are often regarded as the leading painters of the German Romantic movement.Koerner, Joseph Leo. 1990. ''Caspar Dav ...

to Gerhard Richter

Gerhard Richter (; born 9 February 1932) is a German visual artist. Richter has produced abstract as well as photorealistic paintings, and also photographs and glass pieces. He is widely regarded as one of the most important contemporary German ...

and Joseph Beuys

Joseph Heinrich Beuys ( , ; 12 May 1921 – 23 January 1986) was a German artist, teacher, performance artist, and art theorist whose work reflected concepts of humanism, sociology, and anthroposophy. He was a founder of a provocative art mov ...

. This interest has been revived in recent years through the work of the environmental philosopher Arran Gare who has identified a tradition of Schellingian science overcoming the opposition between science and the humanities, and offering the basis for an understanding of ecological science and ecological philosophy.

In relation to psychology, Schelling was considered to have coined the term "unconsciousness

Unconsciousness is a state in which a living individual exhibits a complete, or near-complete, inability to maintain an awareness of self and environment or to respond to any human or environmental stimulus. Unconsciousness may occur as the r ...

". Slavoj Žižek

Slavoj Žižek (, ; ; born 21 March 1949) is a Slovenian philosopher, cultural theorist and public intellectual. He is international director of the Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities at the University of London, visiting professor at New ...

has written two books attempting to integrate Schelling's philosophy, mainly his middle period works including ''Weltalter'', with work of Jacques Lacan

Jacques Marie Émile Lacan (, , ; 13 April 1901 – 9 September 1981) was a French psychoanalyst and psychiatrist. Described as "the most controversial psycho-analyst since Freud", Lacan gave yearly seminars in Paris from 1953 to 1981, and ...

. The opposition and division in God and the problem of evil in God examined by the later Schelling influenced Luigi Pareyson

Luigi Pareysón (4 February 1918 – 8 September 1991) was an Italian philosopher, best known for challenging the positivist and idealist aesthetics of Benedetto Croce in his 1954 monograph, ''Estetica. Teoria della formatività'' (Aesthetic ...

's thought. Ken Wilber places Schelling as one of two philosophers who "after Plato, had the broadest impact on the Western mind".

Quotations

*"Nature is visible spirit, spirit is invisible nature." Natur ist hiernach der sichtbare Geist, Geist die unsichtbare Natur"(''Ideen'', "Introduction") *"History as a whole is a progressive, gradually self-disclosing revelation of the Absolute." (''System of Transcendental Idealism'', 1800) *"Now if the appearance of ''freedom'' is necessarily infinite, the total evolution of the Absolute is also an infinite process, and history itself a never wholly completed revelation of that Absolute which, for the sake of consciousness, and thus merely for the sake of appearance, separates itself into conscious and unconscious, the free and the intuitant; but which ''itself'', however, in the inaccessible light wherein it dwells, is Eternal Identity and the everlasting ground of harmony between the two." (''System of Transcendental Idealism'', 1800) *"Has creation a final goal? And if so, why was it not reached at once? Why was the consummation not realized from the beginning? To these questions there is but one answer: Because God is ''Life'', and not merely Being." (''Philosophical Inquiries into the Nature of Human Freedom

''Philosophical Inquiries into the Essence of Human Freedom'' (german: Philosophische Untersuchungen über das Wesen der menschlichen Freiheit und die damit zusammenhängenden Gegenstände) is an 1809 work by Friedrich Schelling. It was the last ...

'', 1809)

*"Only he who has tasted freedom can feel the desire to make over everything in its image, to spread it throughout the whole universe." (''Philosophical Inquiries into the Nature of Human Freedom'', 1809)

*"As there is nothing before or outside of God he must contain within himself the ground of his existence. All philosophies say this, but they speak of this ground as a mere concept without making it something real and actual." (''Philosophical Inquiries into the Nature of Human Freedom'', 1809)

*" he Godheadis not divine nature or substance, but the devouring ferocity of purity that a person is able to approach only with an equal purity. Since all Being goes up in it as if in flames, it is necessarily unapproachable to anyone still embroiled in Being." (''The Ages of the World'', c. 1815)

*"God then has no beginning only insofar as there is no beginning of his beginning. The beginning in God is eternal beginning, that is, such a one as was beginning from all eternity, and still is, and also never ceases to be beginning." (Quoted in Hartshorne & Reese, ''Philosophers Speak of God'', Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1953, p. 237.)

Bibliography

Selected works are listed below. * ''Ueber Mythen, historische Sagen und Philosopheme der ältesten Welt'' (''On Myths, Historical Legends and Philosophical Themes of Earliest Antiquity'', 1793) # ''Ueber die Möglichkeit einer Form der Philosophie überhaupt'' (''On the Possibility of an Absolute Form of Philosophy'', 1794), # ''Vom Ich als Prinzip der Philosophie oder über das Unbedingte im menschlichen Wissen'' (''Of the I as the Principle of Philosophy or on the Unconditional in Human Knowledge'', 1795), and # ''Philosophische Briefe über Dogmatismus und Kriticismus'' (''Philosophical Letters on Dogmatism and Criticism'', 1795). * 1, 2, 3 in ''The Unconditional in Human Knowledge: Four Early Essays 1794–6'', translation and commentary by F. Marti, Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press (1980). * ''De Marcione Paulinarum epistolarum emendatore'' (1795). * ''Abhandlung zur Erläuterung des Idealismus der Wissenschaftslehre'' (1796). Translated as ''Treatise Explicatory of the Idealism in the 'Science of Knowledge in Thomas Pfau, ''Idealism and the Endgame of Theory'', Albany: SUNY Press (1994). * ''Ideen zu einer Philosophie der Natur als Einleitung in das Studium dieser Wissenschaft'' (1797) as ''Ideas for a Philosophy of Nature: as Introduction to the Study of this Science'', translated by E. E. Harris and P. Heath, introduction R. Stern, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1988). * ''Von der Weltseele'' (1798). * '' System des transcendentalen Idealismus'' (1800) as ''System of Transcendental Idealism'', translated by P. Heath, introduction M. Vater, Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia (1978). * ''Ueber den wahren Begriff der Naturphilosophie und die richtige Art ihre Probleme aufzulösen'' (1801). * "Darstellung des Systems meiner Philosophie" (1801), also known as "Darstellung meines Systems der Philosophie", as "Presentation of My System of Philosophy," translated by M. Vater, ''The Philosophical Forum'', 32(4), Winter 2001, pp. 339–371. * ''Bruno oder über das göttliche und natürliche Prinzip der Dinge'' (1802) as ''Bruno, or on the Natural and the Divine Principle of Things'', translated with an introduction by M. Vater, Albany: State University of New York Press (1984). * ''On the Relationship of the Philosophy of Nature to Philosophy in General'' (1802). Translated by George di Giovanni and H.S. Harris in ''Between Kant and Hegel'', Albany: SUNY Press (1985). * ''Philosophie der Kunst'' (lecture) (delivered 1802–3; published 1859) as ''The Philosophy of Art'' (1989) Minnesota: Minnesota University Press. * ''Vorlesungen über die Methode des akademischen Studiums'' (delivered 1802; published 1803) as ''On University Studies'', translated E. S. Morgan, edited N. Guterman, Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press (1966). * ''Ideas on a Philosophy of Nature as an Introduction to the Study of This Science'' (Second edition, 1803). Translated by Priscilla Hayden-Roy in ''Philosophy of German Idealism'', New York: Continuum (1987). * ''System der gesamten Philosophie und der Naturphilosophie insbesondere'' (''Nachlass

''Nachlass'' (, older spelling ''Nachlaß'') is a German word, used in academia to describe the collection of manuscripts, notes, correspondence, and so on left behind when a scholar dies. The word is a compound in German: ''nach'' means "after ...

'') (1804). Translated as ''System of Philosophy in General and of the Philosophy of Nature in Particular'' in Thomas Pfau, ''Idealism and the Endgame of Theory'', Albany: SUNY Press (1994).

* '' Philosophische Untersuchungen über das Wesen der menschlichen Freiheit und die damit zusammenhängenden Gegenstände'' (1809) as ''Of Human Freedom'', a translation with critical introduction and notes by J. Gutmann, Chicago: Open Court (1936); also as ''Philosophical Investigations into the Essence of Human Freedom'', trans. Jeff Love and Johannes Schmidt, SUNY Press (2006).

* ''Clara. Oder über den Zusammenhang der Natur- mit der Geisterwelt'' (''Nachlass'') (1810) as ''Clara: or on Nature's Connection to the Spirit World'' trans. Fiona Steinkamp, Albany: State University of New York Press, 2002.

* ''Stuttgart Seminars'' (1810), translated by Thomas Pfau in ''Idealism and the Endgame of Theory'', Albany: SUNY Press (1994).

* ''Weltalter'' (1811–15) as ''The Ages of the World'', translated with introduction and notes by F. de W. Bolman, jr., New York: Columbia University Press (1967); also in ''The Abyss of Freedom/Ages of the World'', trans. Judith Norman, with an essay by Slavoj Žižek

Slavoj Žižek (, ; ; born 21 March 1949) is a Slovenian philosopher, cultural theorist and public intellectual. He is international director of the Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities at the University of London, visiting professor at New ...

, Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press (1997).

* "Ueber