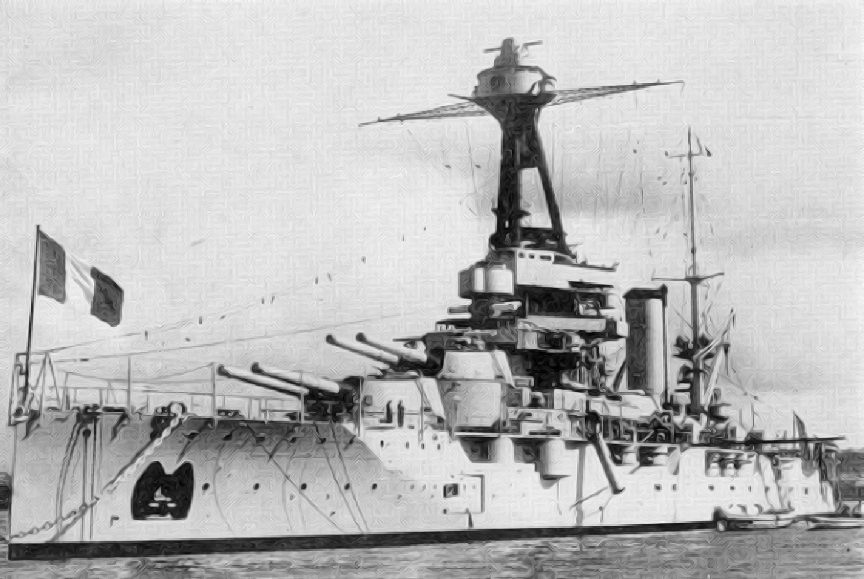

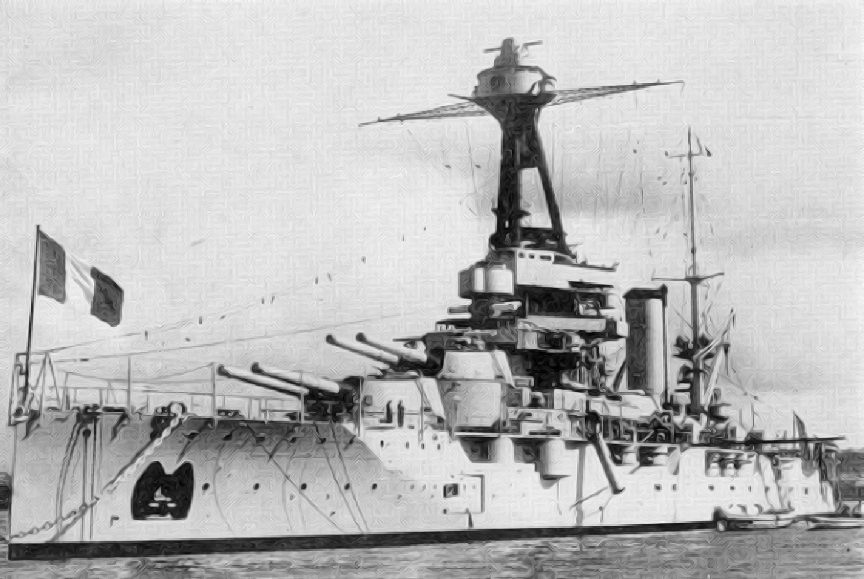

French battleship Provence on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Provence'' was one of three s built for the

The ''Bretagne'' class was designed as an improved version of the preceding with a more powerful armament, but the limited size of French drydocks forced the turrets to be closer to the ends of the ships, adversely affecting their

The ''Bretagne'' class was designed as an improved version of the preceding with a more powerful armament, but the limited size of French drydocks forced the turrets to be closer to the ends of the ships, adversely affecting their

After entering service in 1916, ''Provence'' and her sisters were assigned to the 1st Division of the 1st Battle Squadron, with ''Provence'' as the fleet

After entering service in 1916, ''Provence'' and her sisters were assigned to the 1st Division of the 1st Battle Squadron, with ''Provence'' as the fleet

At the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, ''Provence'' was in Toulon along with ''Bretagne'' in the 2nd Squadron, with ''Provence'' serving as the flagship of Vice Admiral Ollive. On 21 October, she went into drydock for periodic maintenance, which lasted until 2 December. Two days later, ''Provence'' and ''Bretagne'', along with numerous cruisers and destroyers, sortied from

At the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, ''Provence'' was in Toulon along with ''Bretagne'' in the 2nd Squadron, with ''Provence'' serving as the flagship of Vice Admiral Ollive. On 21 October, she went into drydock for periodic maintenance, which lasted until 2 December. Two days later, ''Provence'' and ''Bretagne'', along with numerous cruisers and destroyers, sortied from

French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

in the 1910s, named in honor of the French region of Provence

Provence (, , , , ; oc, Provença or ''Prouvènço'' , ) is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which extends from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the Italian border to the east; it is bo ...

; she had two sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

s, ''Bretagne'' and ''Lorraine''. ''Provence'' entered service in March 1916, after the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. She was armed with a main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a gun or group of guns, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, this came to be turreted ...

of ten guns and had a top speed of .

''Provence'' spent the bulk of her career in the French Mediterranean Squadron, where she served as the fleet flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the ...

. During World War I, she was stationed at Corfu

Corfu (, ) or Kerkyra ( el, Κέρκυρα, Kérkyra, , ; ; la, Corcyra.) is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands, and, including its small satellite islands, forms the margin of the northwestern frontier of Greece. The isl ...

to prevent the Austro-Hungarian fleet

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with t ...

from leaving the Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to th ...

, but she saw no action. She was modernized significantly in the 1920s and 1930s, and conducted normal peacetime cruises and training maneuvers in the Mediterranean and Atlantic Ocean. She participated in non-intervention

Non-interventionism or non-intervention is a political philosophy or national foreign policy doctrine that opposes interference in the domestic politics and affairs of other countries but, in contrast to isolationism, is not necessarily opposed t ...

patrols during the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

.

In the early days of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, ''Provence'' conducted patrols and sweeps into the Atlantic to search for German surface raiders. She was stationed in Mers-el-Kébir when France surrendered on 22 June 1940. Fearful that the Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

would seize the French Navy, the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

attacked the ships at Mers-el-Kébir. ''Provence'' was damaged and sank in the harbor, though she was refloated and moved to Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

, where she became the flagship of the training fleet there. In late November 1942, the Germans occupied Toulon and, to prevent them from seizing the fleet, the French scuttled their ships, including ''Provence''. She was raised in July 1943, and some of her guns were used for coastal defense in the area; the Germans scuttled her a second time in Toulon as a blockship

A blockship is a ship deliberately sunk to prevent a river, channel, or canal from being used. It may either be sunk by a navy defending the waterway to prevent the ingress of attacking enemy forces, as in the case of at Portland Harbour in 1914 ...

in 1944. ''Provence'' was ultimately raised in April 1949 and sold to ship breakers.

Background and description

The ''Bretagne'' class was designed as an improved version of the preceding with a more powerful armament, but the limited size of French drydocks forced the turrets to be closer to the ends of the ships, adversely affecting their

The ''Bretagne'' class was designed as an improved version of the preceding with a more powerful armament, but the limited size of French drydocks forced the turrets to be closer to the ends of the ships, adversely affecting their seakeeping

Seakeeping ability or seaworthiness is a measure of how well-suited a watercraft is to conditions when underway. A ship or boat which has good seakeeping ability is said to be very seaworthy and is able to operate effectively even in high sea stat ...

abilities. The ships were long overall, had a beam of and a mean draft

Draft, The Draft, or Draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a vesse ...

of . They displaced at normal load and at deep load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into we ...

. Their crew numbered 34 officers and 1,159 men as a private ship and increased to 42 officers and 1,208 crewmen when serving as a flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the ...

. The ships were powered by two license-built Parsons

Parsons may refer to:

Places

In the United States:

* Parsons, Kansas, a city

* Parsons, Missouri, an unincorporated community

* Parsons, Tennessee, a city

* Parsons, West Virginia, a town

* Camp Parsons, a Boy Scout camp in the state of Washingt ...

steam turbine

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam tu ...

sets, each driving two propeller shafts. Each of the ''Bretagne''-class ships had a different type of boiler

A boiler is a closed vessel in which fluid (generally water) is heated. The fluid does not necessarily boil. The heated or vaporized fluid exits the boiler for use in various processes or heating applications, including water heating, central ...

providing steam to the turbines; ''Provence'' herself had 18 Guyot- Du Temple boilers. The turbines were rated at a total of and were designed for a top speed of , but none of the ships exceeded during their sea trial

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a " shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and ...

s. They carried enough coal and fuel oil

Fuel oil is any of various fractions obtained from the distillation of petroleum (crude oil). Such oils include distillates (the lighter fractions) and residues (the heavier fractions). Fuel oils include heavy fuel oil, marine fuel oil (MFO), b ...

to give them a range of at a speed of .

The ''Bretagne'' class's main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a gun or group of guns, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, this came to be turreted ...

consisted of ten Canon de 34 cm (13.4 in) modèle 1912 guns mounted in five twin-gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechanis ...

s, numbered one to five from front to rear. Two were in a superfiring pair forward, one amidships

This glossary of nautical terms is an alphabetical listing of terms and expressions connected with ships, shipping, seamanship and navigation on water (mostly though not necessarily on the sea). Some remain current, while many date from the 17t ...

, and the last two in a superfiring pair aft. The secondary armament

Secondary armament is a term used to refer to smaller, faster-firing weapons that were typically effective at a shorter range than the main (heavy) weapons on military systems, including battleship- and cruiser-type warships, tanks/armored p ...

consisted of twenty-two Canon de 138 mm (5.4 in) modèle 1910 guns in casemate

A casemate is a fortified gun emplacement or armored structure from which guns are fired, in a fortification, warship, or armoured fighting vehicle.Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary

When referring to antiquity, the term "casemate wall" me ...

s along the length of the hull. She also carried a pair of Canon de modèle 1902 guns mounted in the forward superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

. Five older 47 mm weapons were placed on each turret roof for sub-caliber training

Sub-caliber training is used to save wear and expense when training with a larger gun by use of smaller weapons (sometimes, but not always, with very similar ballistic characteristics). The smaller weapons could be inserted into the larger weapo ...

before they entered service. The ''Bretagne''s were also armed with four submerged torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s and could stow 20–28 mines below decks. Their waterline

The waterline is the line where the hull of a ship meets the surface of the water. Specifically, it is also the name of a special marking, also known as an international load line, Plimsoll line and water line (positioned amidships), that indi ...

belt

Belt may refer to:

Apparel

* Belt (clothing), a leather or fabric band worn around the waist

* Championship belt, a type of trophy used primarily in combat sports

* Colored belts, such as a black belt or red belt, worn by martial arts practiti ...

ranged in thickness from and was thickest amidships. The gun turrets were protected by of armor and plates protected the casemates. The curved armored deck was thick on the flat and on the outer slopes. The conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armored, from which an officer in charge can conn the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for the ship's engine, rudder, lines, and gro ...

had thick face and sides.

Service

After entering service in 1916, ''Provence'' and her sisters were assigned to the 1st Division of the 1st Battle Squadron, with ''Provence'' as the fleet

After entering service in 1916, ''Provence'' and her sisters were assigned to the 1st Division of the 1st Battle Squadron, with ''Provence'' as the fleet flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the ...

. The three ships remained in the unit for the remainder of the war. They spent the majority of their time at Corfu

Corfu (, ) or Kerkyra ( el, Κέρκυρα, Kérkyra, , ; ; la, Corcyra.) is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands, and, including its small satellite islands, forms the margin of the northwestern frontier of Greece. The isl ...

to prevent the Austro-Hungarian fleet from attempting to break out of the Adriatic. The fleet's presence was also intended to intimidate Greece, which had become increasingly hostile to the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

. Later in the war, men were drawn from their crews for anti-submarine warfare vessels. As the Austro-Hungarians largely remained in port for the duration of the war, ''Provence'' saw no action during the conflict. Indeed, she did not leave port at all for the entirety of 1917. In April 1919, she returned to Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

. The French Navy intended to send the ship to the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

to join operations against the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

, but a major mutiny prevented the operation. She and ''Lorraine'' went to Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

in October 1919, where they formed the core of the Eastern Mediterranean Squadron.

In June 1921, ''Provence'' and ''Bretagne'' went to Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very ...

for a naval review

A fleet review or naval review is an event where a gathering of ships from a particular navy is paraded and reviewed by an incumbent head of state and/or other official civilian and military dignitaries. A number of national navies continue to ...

, and were back in Toulon in September. In 1922, ''Provence'' and ''Lorraine'' were placed in reserve, leaving ''Bretagne'' the only member of her class in service; while out of service, ''Provence'' underwent a significant refit. The work lasted from 1 February 1922 to 4 July 1923, and was carried out in Toulon. The ship had her armament improved; her main guns were given greater elevation to increase their range, and four 75 mm M1897 guns were installed on the forward superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

. A heavy tripod mast with a fire control station and a rangefinder

A rangefinder (also rangefinding telemeter, depending on the context) is a device used to measure distances to remote objects. Originally optical devices used in surveying, they soon found applications in other fields, such as photography an ...

for the ship's anti-aircraft guns were also added.

Another refit followed on 12 December 1925 – 11 July 1927. The elevation of the main battery guns was again increased, the bow section of the belt armor was removed, and half of her boilers were converted to oil-firing models. A third and final modernization began on 20 September 1931 and lasted until 20 August 1934. The rest of the coal-fired boilers were replaced with six Indret oil-fired boilers, new turbines and main battery guns were installed, along with eight new 75 mm anti-aircraft guns. After emerging from the refit, ''Provence'' and ''Bretagne'' were assigned to the 2nd Squadron in the Atlantic. There, they joined fleet exercises off the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

, Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

, and Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to A ...

. The two ships took part in a cruise to Africa in 1936. In August, they were involved in non-intervention

Non-interventionism or non-intervention is a political philosophy or national foreign policy doctrine that opposes interference in the domestic politics and affairs of other countries but, in contrast to isolationism, is not necessarily opposed t ...

patrols after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

; these patrols lasted until April 1937.

World War II

At the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, ''Provence'' was in Toulon along with ''Bretagne'' in the 2nd Squadron, with ''Provence'' serving as the flagship of Vice Admiral Ollive. On 21 October, she went into drydock for periodic maintenance, which lasted until 2 December. Two days later, ''Provence'' and ''Bretagne'', along with numerous cruisers and destroyers, sortied from

At the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, ''Provence'' was in Toulon along with ''Bretagne'' in the 2nd Squadron, with ''Provence'' serving as the flagship of Vice Admiral Ollive. On 21 October, she went into drydock for periodic maintenance, which lasted until 2 December. Two days later, ''Provence'' and ''Bretagne'', along with numerous cruisers and destroyers, sortied from Dakar

Dakar ( ; ; wo, Ndakaaru) (from daqaar ''tamarind''), is the capital and largest city of Senegal. The city of Dakar proper has a population of 1,030,594, whereas the population of the Dakar metropolitan area is estimated at 3.94 million in 2 ...

to cover French merchant shipping off West Africa and the Azores. Around the middle of the month, the French warships returned to port.

''Provence'' was then sent to Casablanca

Casablanca, also known in Arabic as Dar al-Bayda ( ar, الدَّار الْبَيْضَاء, al-Dār al-Bayḍāʾ, ; ber, ⴹⴹⴰⵕⵍⴱⵉⴹⴰ, ḍḍaṛlbiḍa, : "White House") is the largest city in Morocco and the country's econom ...

, where she joined Force Y. The unit conducted several fruitless sweeps into the Atlantic. While in Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = "Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gibr ...

, she was damaged and forced to return to Toulon for repairs. While en route, she intercepted the Italian passenger ship ''Oceania''; ''Provence'' dispatched her to Marseilles

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Franc ...

so she could be inspected for contraband. ''Provence'' sailed for Oran

Oran ( ar, وَهران, Wahrān) is a major coastal city located in the north-west of Algeria. It is considered the second most important city of Algeria after the capital Algiers, due to its population and commercial, industrial, and cultural ...

on 24 January 1940, and then returned to Force Y in Dakar. Force Y was transferred to Oran on 11 April, arriving five days later. On 27 April, ''Provence'', her two sisters, and several cruisers were moved to Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

. On 18 May, ''Provence'' and ''Bretagne'' returned to Mers El Kébir.

Following the French surrender on 22 June, the French fleet was to be disarmed under German and Italian supervision, under the terms of the Armistice. The British high command, however, was concerned that the French ships would be seized by the Axis powers and placed in service. The Axis navies would then outnumber the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

. Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

therefore ordered Vice Admiral James Somerville

Admiral of the Fleet Sir James Fownes Somerville, (17 July 1882 – 19 March 1949) was a Royal Navy officer. He served in the First World War as fleet wireless officer for the Mediterranean Fleet where he was involved in providing naval suppo ...

, the commander of Force H

Force H was a British naval formation during the Second World War. It was formed in 1940, to replace French naval power in the western Mediterranean removed by the French armistice with Nazi Germany. The force occupied an odd place within the ...

, to neutralize the French fleet at Mers-el-Kébir. He was instructed to order the French vessels to comply with one of various possible courses of action: these were as follows, either to join the British with the Free French

Free France (french: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general , Free France was established as a government-in-exile ...

, or to move the ships to French possessions like Martinique where they would be outside the reach of the Axis powers, or to move them to the USA where they would be interned, or to scuttle themselves, or be sunk. On 3 July, Somerville arrived and delivered the ultimatum. After 10 hours of discussions and the French rejection of any part of the ultimatum, the British ships opened fire.

''Provence'' returned fire about 90 seconds after the British attacked, though she had no success against her assailants. ''Bretagne'' was hit by several shells and exploded, killing most of her crew. ''Provence'' was also hit several times and badly damaged; the shells set her on fire and caused her to settle to the bottom of the harbor, but she did not explode like her sister ship. The ship was subsequently refloated and temporarily repaired, and on 5 November, she was transferred to Toulon, arriving on the 8th. ''Provence'' was escorted by the destroyers , , , , and . Beginning on 1 January 1942, ''Provence'' became the flagship of the Flag Officer, Training Division. On 27 November, the German Army occupied Toulon, and to prevent them from seizing the fleet there, including ''Provence'', the French scuttled their ships. At the time, ''Provence'' was moored next to the old pre-dreadnought

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built between the mid- to late- 1880s and 1905, before the launch of in 1906. The pre-dreadnought ships replaced the ironclad battleships of the 1870s and 1880s. Built from steel, protec ...

and the seaplane carrier

A seaplane tender is a boat or ship that supports the operation of seaplanes. Some of these vessels, known as seaplane carriers, could not only carry seaplanes but also provided all the facilities needed for their operation; these ships are rega ...

. The Italians moved into Toulon and raised ''Provence'' on 11 July 1943. Two of her 340 mm guns were removed from the ship and emplaced in a coastal battery at Saint-Mandrier-sur-Mer

Saint-Mandrier-sur-Mer (, "Saint-Mandrier on Sea"; oc, Sant Mandrier de Mar), commonly referred to simply as Saint-Mandrier (former official name), is a commune in the southeastern French department of Var, Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. ...

outside Toulon. The Axis then scuttled the ship a second time, as a blockship

A blockship is a ship deliberately sunk to prevent a river, channel, or canal from being used. It may either be sunk by a navy defending the waterway to prevent the ingress of attacking enemy forces, as in the case of at Portland Harbour in 1914 ...

in the harbor. ''Provence'' was ultimately raised in April 1949 and was broken up for scrap.

Footnotes

References

* * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Provence Bretagne-class battleships World War I battleships of France World War II battleships of France Ships built in France Shipwrecks of France World War II shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea 1913 ships World War II warships scuttled at Toulon Maritime incidents in July 1940 Maritime incidents in November 1942 Scuttled vessels