Frederick Reines on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Frederick Reines ( ; March 16, 1918 – August 26, 1998) was an American

In 1944

In 1944

In 1951, Reines and his colleague

In 1951, Reines and his colleague  From then on Reines dedicated the major part of his career to the study of the neutrino's properties and interactions, which work would influence study of the neutrino for future researchers to come. Cowan left Los Alamos in 1957 to teach at

From then on Reines dedicated the major part of his career to the study of the neutrino's properties and interactions, which work would influence study of the neutrino for future researchers to come. Cowan left Los Alamos in 1957 to teach at

Reines died after a long illness at the

Reines died after a long illness at the

"On the Detection of the Free Neutrino"

"The Free Antineutrino Absorption Cross Section. Part I. Measurement of the Free Antineutrino Absorption Cross Section. Part II. Expected Cross Section from Measurements of Fission Fragment Electron Spectrum"

"Neutrino Experiments at Reactors"

"Status and Aims of the DUMAND Neutrino Project: the Ocean as a Neutrino Detector"

Guide to the Frederick Reines Papers.

Special Collections and Archives, The UC Irvine Libraries, Irvine, California. * including the Nobel Lecture, December 8, 1995 ''The Neutrino: From Poltergeist to Particle'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Reines, Frederick 1918 births 1998 deaths Nobel laureates in Physics American Nobel laureates American people of Russian-Jewish descent 20th-century American physicists Case Western Reserve University faculty Jewish American scientists Jewish physicists National Medal of Science laureates New York University alumni People from Union City, New Jersey People from Paterson, New Jersey People from Rockland County, New York Stevens Institute of Technology alumni Union Hill High School alumni University of California, Irvine faculty Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Foreign Members of the Russian Academy of Sciences Winners of the Panofsky Prize Manhattan Project people Cold War history of the United States Scientists from New York (state)

physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

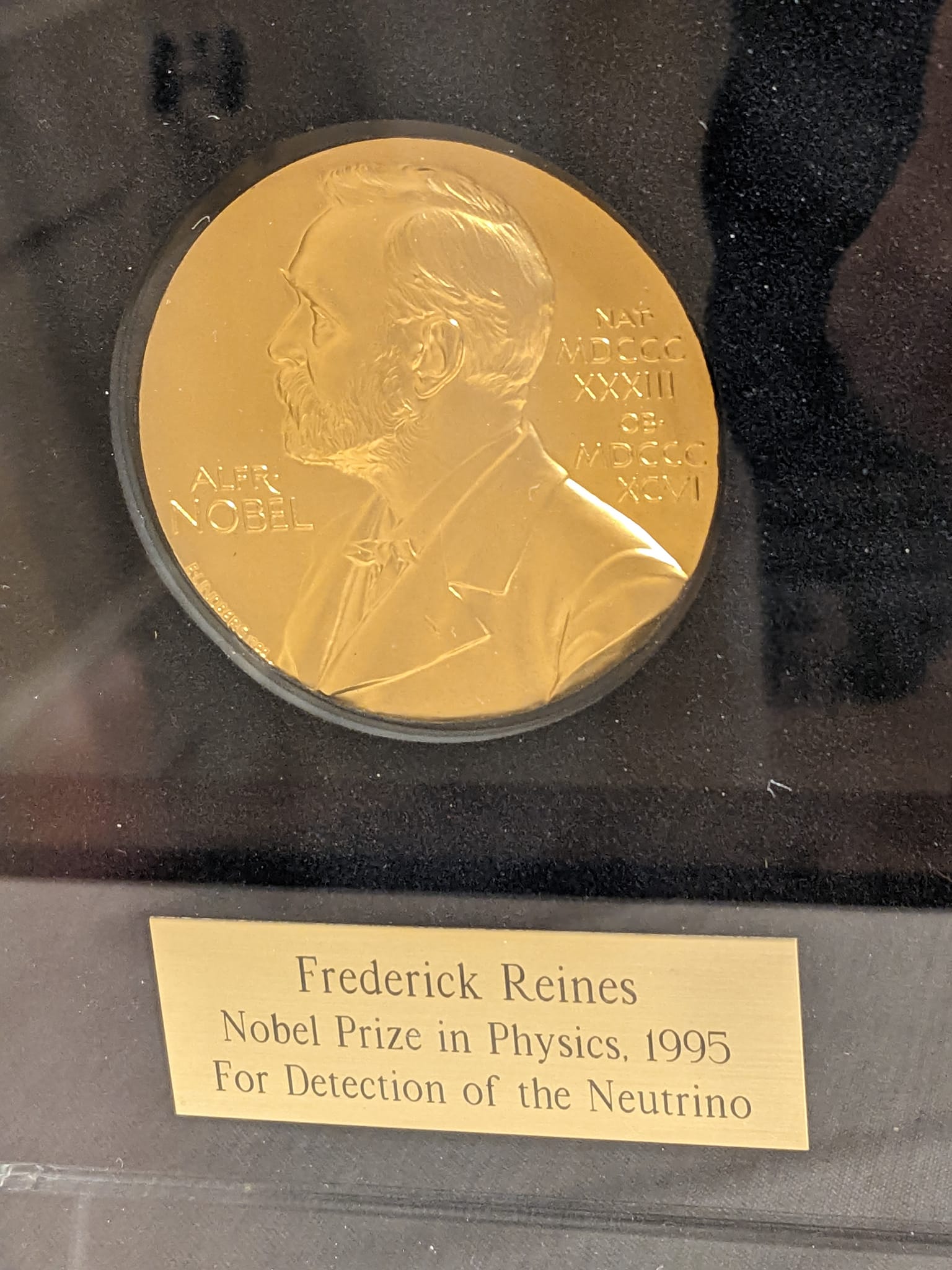

. He was awarded the 1995 Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

for his co-detection of the neutrino

A neutrino ( ; denoted by the Greek letter ) is a fermion (an elementary particle with spin of ) that interacts only via the weak interaction and gravity. The neutrino is so named because it is electrically neutral and because its rest mass ...

with Clyde Cowan

Clyde Lorrain Cowan Jr (December 6, 1919 – May 24, 1974) was an American physicist, the co-discoverer of the neutrino along with Frederick Reines. The discovery was made in 1956 in the neutrino experiment.

Frederick Reines received the Nobel P ...

in the neutrino experiment

A neutrino ( ; denoted by the Greek letter ) is a fermion (an elementary particle with spin of ) that interacts only via the weak interaction and gravity. The neutrino is so named because it is electrically neutral and because its rest mass is ...

. He may be the only scientist in history "so intimately associated with the discovery of an elementary particle

In particle physics, an elementary particle or fundamental particle is a subatomic particle that is not composed of other particles. Particles currently thought to be elementary include electrons, the fundamental fermions ( quarks, leptons, a ...

and the subsequent thorough investigation of its fundamental properties."

A graduate of Stevens Institute of Technology

Stevens Institute of Technology is a private research university in Hoboken, New Jersey. Founded in 1870, it is one of the oldest technological universities in the United States and was the first college in America solely dedicated to mechanical ...

and New York University

New York University (NYU) is a private research university in New York City. Chartered in 1831 by the New York State Legislature, NYU was founded by a group of New Yorkers led by then- Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin.

In 1832, th ...

, Reines joined the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

's Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and operated by the University of California during World War II. Its mission was to design and build the first atomic bombs. Ro ...

in 1944, working in the Theoretical Division in Richard Feynman

Richard Phillips Feynman (; May 11, 1918 – February 15, 1988) was an American theoretical physicist, known for his work in the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics, the theory of quantum electrodynamics, the physics of the superfl ...

's group. He became a group leader there in 1946. He participated in a number of nuclear tests

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine nuclear weapons' effectiveness, yield, and explosive capability. Testing nuclear weapons offers practical information about how the weapons function, how detonations are affected by ...

, culminating in his becoming the director of the Operation Greenhouse

Operation Greenhouse was the fifth American nuclear test series, the second conducted in 1951 and the first to test principles that would lead to developing thermonuclear weapons (''hydrogen bombs''). Conducted at the new Pacific Proving Gro ...

test series in the Pacific in 1951.

In the early 1950s, working in Hanford and Savannah River Site

The Savannah River Site (SRS) is a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) reservation in the United States in the state of South Carolina, located on land in Aiken, Allendale, and Barnwell counties adjacent to the Savannah River, southeast of August ...

s, Reines and Cowan developed the equipment and procedures with which they first detected the supposedly undetectable neutrinos in June 1956. Reines dedicated the major part of his career to the study of the neutrino's properties and interactions, which work would influence study of the neutrino for many researchers to come. This included the detection of neutrinos created in the atmosphere by cosmic ray

Cosmic rays are high-energy particles or clusters of particles (primarily represented by protons or atomic nuclei) that move through space at nearly the speed of light. They originate from the Sun, from outside of the Solar System in our own ...

s, and the 1987 detection of neutrinos emitted from Supernova SN1987A, which inaugurated the field of neutrino astronomy

Neutrino astronomy is the branch of astronomy that observes astronomical objects with neutrino detectors in special observatories. Neutrinos are created as a result of certain types of radioactive decay, nuclear reactions such as those that take ...

.

Early life

Frederick Reines was born in Paterson, New Jersey, one of four children of Gussie (Cohen) and Israel Reines. His parents were Jewish emigrants from the same town in Russia, but only met inNew York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

, where they were later married. He had an older sister, Paula, who became a doctor, and two older brothers, David and William, who became lawyers. He said that his "early education was strongly influenced" by his studious siblings. He was the great-nephew of the Rabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as ''semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of ...

Yitzchak Yaacov Reines

Yitzchak Yaacov Reines ( he, יצחק יעקב ריינס, Isaac Jacob Reines), (October 27, 1839 – August 20, 1915) was a Lithuanian Orthodox rabbi and the founder of the Mizrachi Religious Zionist Movement, one of the earliest movements o ...

, the founder of Mizrachi, a religious Zionist movement

Religious Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת דָּתִית, translit. ''Tziyonut Datit'') is an ideology that combines Zionism and Orthodox Judaism. Its adherents are also referred to as ''Dati Leumi'' ( "National Religious"), and in Israel, the ...

.

The family moved to Hillburn, New York

Hillburn, originally called "Woodburn" and incorporated in 1893, is a Administrative divisions of New York#Village, village in the town of Ramapo, New York, Ramapo, Rockland County, New York, Rockland County, New York (state), New York, United St ...

, where his father ran the general store, and he spent much of his childhood. He was an Eagle Scout

Eagle Scout is the highest achievement or rank attainable in the Scouts BSA program of the Boy Scouts of America (BSA). Since its inception in 1911, only four percent of Scouts have earned this rank after a lengthy review process. The Eagle S ...

. Looking back, Reines said: "My early childhood memories center around this typical American country store and life in a small American town, including Independence Day July celebrations marked by fireworks and patriotic music played from a pavilion bandstand."

Reines sang in a chorus, and as a soloist. For a time he considered the possibility of a singing career, and was instructed by a vocal coach from the Metropolitan Opera

The Metropolitan Opera (commonly known as the Met) is an American opera company based in New York City, resident at the Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center, currently situated on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The company is oper ...

who provided lessons for free because the family did not have the money for them. The family later moved to North Bergen, New Jersey

North Bergen is a township in the northern part of Hudson County, New Jersey, United States. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the township had a total population of 63,361. The township was founded in 1843. It was much diminished in territory by ...

, residing on Kennedy Boulevard and 57th Street. Because North Bergen did not have a high school, he attended Union Hill High School

Union Hill High School was a public high school serving students in grades 9–12 from Union City in Hudson County, New Jersey, United States, operating as one of two high schools of the Union City Board of Education, an Abbott District. The ...

in Union Hill, New Jersey

Union Hill was a town that existed in Hudson County, New Jersey, United States, from 1864 to June 1, 1925, when it merged with West Hoboken to form Union City.

History

Civic boundaries

The area that became West Hoboken was originally inhab ...

(today Union City, New Jersey

Union City is a city in the northern part of Hudson County, New Jersey, United States. According to the 2020 United States Census the city had a total population of 68,589,simulate

A simulation is the imitation of the operation of a real-world process or system over time. Simulations require the use of Conceptual model, models; the model represents the key characteristics or behaviors of the selected system or proc ...

a telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, absorption, or reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally meaning only an optical instrument using lenses, curved mirrors, or a combination of both to observ ...

, I noticed something peculiar about the light; it was the phenomenon of diffraction. That began for me a fascination with light.

Ironically, Reines excelled in literary and history courses, but received average or low marks in science and math in his freshman year of high school, though he improved in those areas by his junior

Junior or Juniors may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

* ''Junior'' (Junior Mance album), 1959

* ''Junior'' (Röyksopp album), 2009

* ''Junior'' (Kaki King album), 2010

* ''Junior'' (LaFontaines album), 2019

Films

* ''Junior'' (1994 ...

and senior years through the encouragement of a teacher who gave him a key to the school laboratory. This cultivated a love of science by his senior year. In response to a question seniors were asked about what they wanted to do for a yearbook quote, he responded: "To be a physicist extraordinaire."

Reines was accepted into the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the ...

, but chose instead to attend Stevens Institute of Technology

Stevens Institute of Technology is a private research university in Hoboken, New Jersey. Founded in 1870, it is one of the oldest technological universities in the United States and was the first college in America solely dedicated to mechanical ...

in Hoboken, New Jersey

Hoboken ( ; Unami: ') is a city in Hudson County in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the city's population was 60,417. The Census Bureau's Population Estimates Program calculated that the city's population was 58,690 i ...

, where he earned his Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University o ...

(B.S.) degree in mechanical engineering

Mechanical engineering is the study of physical machines that may involve force and movement. It is an engineering branch that combines engineering physics and mathematics principles with materials science, to design, analyze, manufacture, an ...

in 1939, and his Master of Science

A Master of Science ( la, Magisterii Scientiae; abbreviated MS, M.S., MSc, M.Sc., SM, S.M., ScM or Sc.M.) is a master's degree in the field of science awarded by universities in many countries or a person holding such a degree. In contrast t ...

(M.S.) degree in mathematical physics in 1941, writing a thesis on "A Critical Review of Optical Diffraction Theory". He married Sylvia Samuels on August 30, 1940. They had two children, Robert and Alisa. He then entered New York University

New York University (NYU) is a private research university in New York City. Chartered in 1831 by the New York State Legislature, NYU was founded by a group of New Yorkers led by then- Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin.

In 1832, th ...

, where he earned his Doctor of Philosophy

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, Ph.D., or DPhil; Latin: or ') is the most common degree at the highest academic level awarded following a course of study. PhDs are awarded for programs across the whole breadth of academic fields. Because it is ...

(Ph.D.) in 1944. He studied cosmic rays

Cosmic rays are high-energy particles or clusters of particles (primarily represented by protons or atomic nuclei) that move through space at nearly the speed of light. They originate from the Sun, from outside of the Solar System in our ow ...

there under Serge A. Korff, but wrote his thesis

A thesis ( : theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144: ...

under the supervision of Richard D. Present on "Nuclear fission and the liquid drop model of the nucleus". Publication of the thesis was delayed until after the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

; it appeared in Physical Review in 1946.

Los Alamos Laboratory

In 1944

In 1944 Richard Feynman

Richard Phillips Feynman (; May 11, 1918 – February 15, 1988) was an American theoretical physicist, known for his work in the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics, the theory of quantum electrodynamics, the physics of the superfl ...

recruited Reines to work in the Theoretical Division at the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

's Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and operated by the University of California during World War II. Its mission was to design and build the first atomic bombs. Ro ...

, where he would remain for the next fifteen years. He joined Feynman's T-4 (Diffusion Problems) Group, which was part of Hans Bethe

Hans Albrecht Bethe (; July 2, 1906 – March 6, 2005) was a German-American theoretical physicist who made major contributions to nuclear physics, astrophysics, quantum electrodynamics, and solid-state physics, and who won the 1967 Nobel ...

's T (Theoretical) Division. Diffusion

Diffusion is the net movement of anything (for example, atoms, ions, molecules, energy) generally from a region of higher concentration to a region of lower concentration. Diffusion is driven by a gradient in Gibbs free energy or chemica ...

was an important aspect of critical mass

In nuclear engineering, a critical mass is the smallest amount of fissile material needed for a sustained nuclear chain reaction. The critical mass of a fissionable material depends upon its nuclear properties (specifically, its nuclear fi ...

calculations. In June 1946, he became a group leader, heading the T-1 (Theory of Dragon) Group. An outgrowth of the " tickling the Dragon's tail" experiment, the Dragon was a machine that could attain a critical state for short bursts of time, which could be used as a research tool or power source.

Reines participated in a number of nuclear test

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine nuclear weapons' effectiveness, Nuclear weapon yield, yield, and explosive capability. Testing nuclear weapons offers practical information about how the weapons function, how detona ...

s, and writing reports on their results. These included Operation Crossroads

Operation Crossroads was a pair of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in mid-1946. They were the first nuclear weapon tests since Trinity in July 1945, and the first detonations of nuclear devices since the ...

at Bikini Atoll

Bikini Atoll ( or ; Marshallese: , , meaning "coconut place"), sometimes known as Eschscholtz Atoll between the 1800s and 1946 is a coral reef in the Marshall Islands consisting of 23 islands surrounding a central lagoon. After the Seco ...

in 1946, Operation Sandstone

Operation Sandstone was a series of nuclear weapon tests in 1948. It was the third series of American tests, following Trinity in 1945 and Crossroads in 1946, and preceding Ranger. Like the Crossroads tests, the Sandstone tests were carried ou ...

at Eniwetok Atoll

Enewetak Atoll (; also spelled Eniwetok Atoll or sometimes Eniewetok; mh, Ānewetak, , or , ; known to the Japanese as Brown Atoll or Brown Island; ja, ブラウン環礁) is a large coral atoll of 40 islands in the Pacific Ocean and with it ...

in 1948, and Operation Ranger

Operation Ranger was the fourth American nuclear test series. It was conducted in 1951 and was the first series to be carried out at the Nevada Test Site.

All the bombs were dropped by B-50D bombers and exploded in the open air over Frenchma ...

and Operation Buster–Jangle

Operation Buster–Jangle was a series of seven (six atmospheric, one cratering) nuclear weapons tests conducted by the United States in late 1951 at the Nevada Test Site. ''Buster–Jangle'' was the first joint test program between the DOD ...

at the Nevada Test Site

The Nevada National Security Site (N2S2 or NNSS), known as the Nevada Test Site (NTS) until 2010, is a United States Department of Energy (DOE) reservation located in southeastern Nye County, Nevada, about 65 miles (105 km) northwest of the ...

. In 1951 he was the director of Operation Greenhouse

Operation Greenhouse was the fifth American nuclear test series, the second conducted in 1951 and the first to test principles that would lead to developing thermonuclear weapons (''hydrogen bombs''). Conducted at the new Pacific Proving Gro ...

series of nuclear tests

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine nuclear weapons' effectiveness, yield, and explosive capability. Testing nuclear weapons offers practical information about how the weapons function, how detonations are affected by ...

in the Pacific. This saw the first American tests of boosted fission weapon

A boosted fission weapon usually refers to a type of nuclear bomb that uses a small amount of fusion fuel to increase the rate, and thus yield, of a fission reaction. The neutrons released by the fusion reactions add to the neutrons released ...

s, an important step towards thermonuclear weapon

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a low ...

s. He studied the effects of nuclear blasts, and co-authored a paper with John von Neumann

John von Neumann (; hu, Neumann János Lajos, ; December 28, 1903 – February 8, 1957) was a Hungarian-American mathematician, physicist, computer scientist, engineer and polymath. He was regarded as having perhaps the widest cove ...

on Mach stem formation, an important aspect of an air blast wave

In fluid dynamics, a blast wave is the increased pressure and flow resulting from the deposition of a large amount of energy in a small, very localised volume. The flow field can be approximated as a lead shock wave, followed by a self-similar sub ...

.

In spite or perhaps because of his role in these nuclear tests, Reines was concerned about the dangers of radioactive pollution from atmospheric nuclear tests, and became an advocate of underground nuclear testing

Underground nuclear testing is the test detonation of nuclear weapons that is performed underground. When the device being tested is buried at sufficient depth, the nuclear explosion may be contained, with no release of radioactive materials to ...

. In the wake of the Sputnik crisis, he participated in John Archibald Wheeler

John Archibald Wheeler (July 9, 1911April 13, 2008) was an American theoretical physicist. He was largely responsible for reviving interest in general relativity in the United States after World War II. Wheeler also worked with Niels Bohr in ...

's Project 137, which evolved into JASON

Jason ( ; ) was an ancient Greek mythological hero and leader of the Argonauts, whose quest for the Golden Fleece featured in Greek literature. He was the son of Aeson, the rightful king of Iolcos. He was married to the sorceress Medea. He ...

. He was also a delegate at the Atoms for Peace

"Atoms for Peace" was the title of a speech delivered by U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower to the UN General Assembly in New York City on December 8, 1953.

The United States then launched an "Atoms for Peace" program that supplied equipment ...

Conference in Geneva in 1958.

Discovery of the neutrino and the inner workings of stars

Theneutrino

A neutrino ( ; denoted by the Greek letter ) is a fermion (an elementary particle with spin of ) that interacts only via the weak interaction and gravity. The neutrino is so named because it is electrically neutral and because its rest mass ...

is a subatomic particle first proposed by Wolfgang Pauli

Wolfgang Ernst Pauli (; ; 25 April 1900 – 15 December 1958) was an Austrian theoretical physicist and one of the pioneers of quantum physics. In 1945, after having been nominated by Albert Einstein, Pauli received the Nobel Prize in Physics ...

on December 4, 1930. The particle was required to resolve the problem of missing energy in observations of beta decay

In nuclear physics, beta decay (β-decay) is a type of radioactive decay in which a beta particle (fast energetic electron or positron) is emitted from an atomic nucleus, transforming the original nuclide to an isobar of that nuclide. For ...

, when a neutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , which has a neutral (not positive or negative) charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. Protons and neutrons constitute the nuclei of atoms. Since protons and neutrons beh ...

decays into a proton and an electron

The electron ( or ) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. Electrons belong to the first generation of the lepton particle family,

and are generally thought to be elementary particles because they have no ...

. The new hypothetical particle was required to preserve the fundamental law of conservation of energy. Enrico Fermi renamed it the neutrino

A neutrino ( ; denoted by the Greek letter ) is a fermion (an elementary particle with spin of ) that interacts only via the weak interaction and gravity. The neutrino is so named because it is electrically neutral and because its rest mass ...

, Italian for "little neutral one", and in 1934, proposed his theory of beta decay by which the electrons emitted from the nucleus were created by the decay of a neutron into a proton, an electron, and a neutrino:

: → + +

The neutrino accounted for the missing energy, but Fermi's theory described a particle with little mass and no electric charge that appeared to be impossible to observe directly. In a 1934 paper, Rudolf Peierls

Sir Rudolf Ernst Peierls, (; ; 5 June 1907 – 19 September 1995) was a German-born British physicist who played a major role in Tube Alloys, Britain's nuclear weapon programme, as well as the subsequent Manhattan Project, the combined Allie ...

and Hans Bethe

Hans Albrecht Bethe (; July 2, 1906 – March 6, 2005) was a German-American theoretical physicist who made major contributions to nuclear physics, astrophysics, quantum electrodynamics, and solid-state physics, and who won the 1967 Nobel ...

calculated that neutrinos could easily pass through the Earth, and concluded "there is no practically possible way of observing the neutrino."  In 1951, Reines and his colleague

In 1951, Reines and his colleague Clyde Cowan

Clyde Lorrain Cowan Jr (December 6, 1919 – May 24, 1974) was an American physicist, the co-discoverer of the neutrino along with Frederick Reines. The discovery was made in 1956 in the neutrino experiment.

Frederick Reines received the Nobel P ...

decided to see if they could detect neutrinos and so prove their existence. At the conclusion of the Greenhouse test series, Reines had received permission from the head of T Division, J. Carson Mark, for a leave in residence to study fundamental physics. "So why did we want to detect the free neutrino?" he later explained, "Because everybody said, you couldn't do it."

According to Fermi's theory, there was also a corresponding reverse reaction, in which a neutrino combines with a proton to create a neutron and a positron:

: + → +

The positron would soon be annihilated by an electron and produce two 0.51 MeV gamma rays

A gamma ray, also known as gamma radiation (symbol γ or \gamma), is a penetrating form of electromagnetic radiation arising from the radioactive decay of atomic nuclei. It consists of the shortest wavelength electromagnetic waves, typically ...

, while the neutron would be captured by a proton and release a 2.2 MeV gamma ray. This would produce a distinctive signature that could be detected. They then realised that by adding cadmium

Cadmium is a chemical element with the symbol Cd and atomic number 48. This soft, silvery-white metal is chemically similar to the two other stable metals in group 12, zinc and mercury. Like zinc, it demonstrates oxidation state +2 in most of ...

salt to their liquid scintillator they would enhance the neutron capture reaction, resulting in a 9 MeV burst of gamma rays. For a neutrino source, they proposed using an atomic bomb. Permission for this was obtained from the laboratory director, Norris Bradbury

Norris Edwin Bradbury (May 30, 1909 – August 20, 1997), was an American physicist who served as director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory for 25 years from 1945 to 1970. He succeeded Robert Oppenheimer, who personally chose Bradbur ...

. Work began on digging a shaft for the experiment when J. M. B. Kellogg convinced them to use a nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat fr ...

instead of a bomb. Although a less intense source of neutrinos, it had the advantage in allowing for multiple experiments to be carried out over a long period of time.

In 1953, they made their first attempts using one of the large reactors at the Hanford nuclear site

The Hanford Site is a decommissioned nuclear production complex operated by the United States federal government on the Columbia River in Benton County, Washington, Benton County in the U.S. state of Washington (state), Washington. The site h ...

in what is now known as the Cowan–Reines neutrino experiment

The Cowan–Reines neutrino experiment was conducted by Washington University in St. Louis alumnus Clyde L. Cowan and Stevens Institute of Technology and New York University alumnus Frederick Reines in 1956. The experiment confirmed the existenc ...

. Their detector now included of scintillating fluid and 90 photomultiplier A photomultiplier is a device that converts incident photons into an electrical signal.

Kinds of photomultiplier include:

* Photomultiplier tube, a vacuum tube converting incident photons into an electric signal. Photomultiplier tubes (PMTs for sh ...

tubes, but the effort was frustrated by background noise from cosmic rays. With encouragement from John A. Wheeler

John Archibald Wheeler (July 9, 1911April 13, 2008) was an American theoretical physicist. He was largely responsible for reviving interest in general relativity in the United States after World War II. Wheeler also worked with Niels Bohr in e ...

, they tried again in 1955, this time using one of the newer, larger 700 MW reactors at the Savannah River Site

The Savannah River Site (SRS) is a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) reservation in the United States in the state of South Carolina, located on land in Aiken, Allendale, and Barnwell counties adjacent to the Savannah River, southeast of August ...

that emitted a high neutrino flux of 1.2 x 1012 / cm2 sec. They also had a convenient, well-shielded location from the reactor and underground. On June 14, 1956, they were able to send Pauli a telegram announcing that the neutrino had been found. When Bethe was informed that he had been proven wrong, he said, "Well, you shouldn't believe everything you read in the papers."

From then on Reines dedicated the major part of his career to the study of the neutrino's properties and interactions, which work would influence study of the neutrino for future researchers to come. Cowan left Los Alamos in 1957 to teach at

From then on Reines dedicated the major part of his career to the study of the neutrino's properties and interactions, which work would influence study of the neutrino for future researchers to come. Cowan left Los Alamos in 1957 to teach at George Washington University

The George Washington University (GW or GWU) is a Private university, private University charter#Federal, federally chartered research university in Washington, D.C. Chartered in 1821 by the United States Congress, GWU is the largest Higher educat ...

, ending their collaboration. On the basis of his work in first detecting the neutrino

A neutrino ( ; denoted by the Greek letter ) is a fermion (an elementary particle with spin of ) that interacts only via the weak interaction and gravity. The neutrino is so named because it is electrically neutral and because its rest mass ...

, Reines became the head of the physics department of Case Western Reserve University from 1959 to 1966. At Case, he led a group that was the first to detect neutrinos created in the atmosphere by cosmic ray

Cosmic rays are high-energy particles or clusters of particles (primarily represented by protons or atomic nuclei) that move through space at nearly the speed of light. They originate from the Sun, from outside of the Solar System in our own ...

s. Reines had a booming voice, and had been a singer since childhood. During this time, besides performing his duties as a research supervisor and chairman of the physics department, Reines sang in the Cleveland Orchestra Chorus under the direction of Robert Shaw in performances with George Szell

George Szell (; June 7, 1897 – July 30, 1970), originally György Széll, György Endre Szél, or Georg Szell, was a Hungarian-born American conductor and composer. He is widely considered one of the twentieth century's greatest condu ...

and the Cleveland Orchestra

The Cleveland Orchestra, based in Cleveland, is one of the five American orchestras informally referred to as the " Big Five". Founded in 1918 by the pianist and impresario Adella Prentiss Hughes, the orchestra plays most of its concerts at Se ...

.

In 1966, Reines took most of his neutrino research team with him when he left for the new University of California, Irvine

The University of California, Irvine (UCI or UC Irvine) is a public land-grant research university in Irvine, California. One of the ten campuses of the University of California system, UCI offers 87 undergraduate degrees and 129 graduate and p ...

(UCI), becoming its first dean of physical sciences. At UCI, Reines extended the research interests of some of his graduate students into the development of medical radiation detectors, such as for measuring total radiation delivered to the whole human body in radiation therapy

Radiation therapy or radiotherapy, often abbreviated RT, RTx, or XRT, is a therapy using ionizing radiation, generally provided as part of cancer treatment to control or kill malignant cells and normally delivered by a linear accelerator. Radi ...

.

Reines had prepared for the possibility of measuring the distant events of a supernova explosion. Supernova explosions are rare, but Reines thought he might be lucky enough to see one in his lifetime, and be able to catch the neutrinos streaming from it in his specially-designed detectors. During his wait for a supernova to explode, he put signs on some of his large neutrino detectors, calling them "Supernova Early Warning Systems". In 1987, neutrinos emitted from Supernova SN1987A were detected by the Irvine–Michigan–Brookhaven (IMB) Collaboration, which used an 8,000 ton Cherenkov detector located in a salt mine near Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

. Normally, the detectors recorded only a few background events each day. The supernova registered 19 events in just ten seconds. This discovery is regarded as inaugurating the field of neutrino astronomy

Neutrino astronomy is the branch of astronomy that observes astronomical objects with neutrino detectors in special observatories. Neutrinos are created as a result of certain types of radioactive decay, nuclear reactions such as those that take ...

.

In 1995, Reines was honored, along with Martin L. Perl with the Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

for his work with Cowan in first detecting the neutrino. Unfortunately, Cowan had died in 1974, and the Nobel Prize is not awarded posthumously. Reines also received many other awards, including the J. Robert Oppenheimer Memorial Prize in 1981, the National Medal of Science

The National Medal of Science is an honor bestowed by the President of the United States to individuals in science and engineering who have made important contributions to the advancement of knowledge in the fields of behavioral and social scienc ...

in 1985, the Bruno Rossi Prize

The Bruno Rossi Prize is awarded annually by the High Energy Astrophysics division of the American Astronomical Society "for a significant contribution to High Energy Astrophysics, with particular emphasis on recent, original work". Named after as ...

in 1989, the Michelson–Morley Award The Michelson–Morley Award is a science award that originated from the Michelson Award that was established in 1963 by the Case Institute of Technology. It was renamed in 1968 by the newly formed Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) after the f ...

in 1990, the Panofsky Prize

The Panofsky Prize in Experimental Particle Physics is an annual prize of the American Physical Society. It is given to recognize and encourage outstanding achievements in experimental particle physics, and is open to scientists of any nation. It w ...

in 1992, and the Franklin Medal

The Franklin Medal was a science award presented from 1915 until 1997 by the Franklin Institute

The Franklin Institute is a science museum and the center of science education and research in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It is named after the Am ...

in 1992. He was elected a member of the National Academy of Sciences in 1980 and a foreign member of the Russian Academy of Sciences

The Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS; russian: Росси́йская акаде́мия нау́к (РАН) ''Rossíyskaya akadémiya naúk'') consists of the national academy of Russia; a network of scientific research institutes from across ...

in 1994. He remained dean of physical sciences at UCI until 1974, and became a professor emeritus

''Emeritus'' (; female: ''emerita'') is an adjective used to designate a retired chair, professor, pastor, bishop, pope, director, president, prime minister, rabbi, emperor, or other person who has been "permitted to retain as an honorary title ...

in 1988, but he continued teaching until 1991, and remained on UCI's faculty until his death.

Death

Reines died after a long illness at the

Reines died after a long illness at the University of California, Irvine Medical Center

The University of California, Irvine Medical Center (UCIMC or UCI Medical Center) is a major research hospital located in Orange, California. It is the teaching hospital for the University of California, Irvine School of Medicine.

History

Pl ...

in Orange, California

Orange is a city located in North Orange County, California. It is approximately north of the county seat, Santa Ana. Orange is unusual in this region because many of the homes in its Old Town District were built before 1920. While many other ...

, on August 26, 1998. He was survived by his wife and children. His papers are compiled in the UCI Libraries. Frederick Reines Hall, which houses the Physics and Astronomy Department at the University of California, Irvine, was named in his honor.

Publications

* Reines, F. & C. L. Cowan, Jr"On the Detection of the Free Neutrino"

Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory (often shortened as Los Alamos and LANL) is one of the sixteen research and development laboratories of the United States Department of Energy (DOE), located a short distance northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, ...

(LANL) (through predecessor agency Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory), United States Department of Energy

The United States Department of Energy (DOE) is an executive department of the U.S. federal government that oversees U.S. national energy policy and manages the research and development of nuclear power and nuclear weapons in the United Stat ...

(through predecessor agency the Atomic Energy Commission), (August 6, 1953).

* Reines, F., Cowan, C. L. Jr., Carter, R. E., Wagner, J. J. & M. E. Wyman"The Free Antineutrino Absorption Cross Section. Part I. Measurement of the Free Antineutrino Absorption Cross Section. Part II. Expected Cross Section from Measurements of Fission Fragment Electron Spectrum"

Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory (often shortened as Los Alamos and LANL) is one of the sixteen research and development laboratories of the United States Department of Energy (DOE), located a short distance northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, ...

(LANL) (through predecessor agency Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory), United States Department of Energy

The United States Department of Energy (DOE) is an executive department of the U.S. federal government that oversees U.S. national energy policy and manages the research and development of nuclear power and nuclear weapons in the United Stat ...

(through predecessor agency the Atomic Energy Commission), (June 1958).

* Reines, F., Gurr, H. S., Jenkins, T. L. & J. H. Munsee"Neutrino Experiments at Reactors"

University of California-Irvine

The University of California, Irvine (UCI or UC Irvine) is a public land-grant research university in Irvine, California. One of the ten campuses of the University of California system, UCI offers 87 undergraduate degrees and 129 graduate and pr ...

, Case Western Reserve University, United States Department of Energy

The United States Department of Energy (DOE) is an executive department of the U.S. federal government that oversees U.S. national energy policy and manages the research and development of nuclear power and nuclear weapons in the United Stat ...

(through predecessor agency the Atomic Energy Commission), (September 9, 1968).

* Roberts, A., Blood, H., Learned, J. & F. Reines"Status and Aims of the DUMAND Neutrino Project: the Ocean as a Neutrino Detector"

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab), located just outside Batavia, Illinois, near Chicago, is a United States Department of Energy national laboratory specializing in high-energy particle physics. Since 2007, Fermilab has been operat ...

(FNAL), United States Department of Energy

The United States Department of Energy (DOE) is an executive department of the U.S. federal government that oversees U.S. national energy policy and manages the research and development of nuclear power and nuclear weapons in the United Stat ...

(through predecessor agency the Energy Research and Development Administration), (July 1976).

*

Notes

References

* *External links

Guide to the Frederick Reines Papers.

Special Collections and Archives, The UC Irvine Libraries, Irvine, California. * including the Nobel Lecture, December 8, 1995 ''The Neutrino: From Poltergeist to Particle'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Reines, Frederick 1918 births 1998 deaths Nobel laureates in Physics American Nobel laureates American people of Russian-Jewish descent 20th-century American physicists Case Western Reserve University faculty Jewish American scientists Jewish physicists National Medal of Science laureates New York University alumni People from Union City, New Jersey People from Paterson, New Jersey People from Rockland County, New York Stevens Institute of Technology alumni Union Hill High School alumni University of California, Irvine faculty Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Foreign Members of the Russian Academy of Sciences Winners of the Panofsky Prize Manhattan Project people Cold War history of the United States Scientists from New York (state)