Frederick I Barbarossa on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Frederick Barbarossa (December 1122 – 10 June 1190), also known as Frederick I (german: link=no, Friedrich I, it, Federico I), was the

The reigns of Henry IV and

The reigns of Henry IV and

Eager to restore the Empire to the position it had occupied under

Eager to restore the Empire to the position it had occupied under

As Frederick approached the gates of Rome, the Pope advanced to meet him. At the royal tent the king received him, and after kissing the pope's feet, Frederick expected to receive the traditional kiss of peace. Frederick had declined to hold the Pope's stirrup while leading him to the tent, however, so Adrian refused to give the kiss until this protocol had been complied with. Frederick hesitated, and Adrian IV withdrew; after a day's negotiation, Frederick agreed to perform the required ritual, reportedly muttering, "''Pro Petro, non Adriano'' – For Peter, not for Adrian." Rome was still in an uproar over the fate of Arnold of Brescia, so rather than marching through the streets of Rome, Frederick and Adrian retired to the Vatican.

As Frederick approached the gates of Rome, the Pope advanced to meet him. At the royal tent the king received him, and after kissing the pope's feet, Frederick expected to receive the traditional kiss of peace. Frederick had declined to hold the Pope's stirrup while leading him to the tent, however, so Adrian refused to give the kiss until this protocol had been complied with. Frederick hesitated, and Adrian IV withdrew; after a day's negotiation, Frederick agreed to perform the required ritual, reportedly muttering, "''Pro Petro, non Adriano'' – For Peter, not for Adrian." Rome was still in an uproar over the fate of Arnold of Brescia, so rather than marching through the streets of Rome, Frederick and Adrian retired to the Vatican.

The next day, 18 June 1155, Adrian IV crowned Frederick I

The next day, 18 June 1155, Adrian IV crowned Frederick I

The retreat of Frederick in 1155 forced Pope Adrian IV to come to terms with King William I of Sicily, granting to William I territories that Frederick viewed as his dominion. This aggrieved Frederick, and he was further displeased when

The retreat of Frederick in 1155 forced Pope Adrian IV to come to terms with King William I of Sicily, granting to William I territories that Frederick viewed as his dominion. This aggrieved Frederick, and he was further displeased when  In the meantime Frederick was focused on restoring peace in the Rhineland, where he organized a magnificent celebration of the

In the meantime Frederick was focused on restoring peace in the Rhineland, where he organized a magnificent celebration of the

Increasing anti-German sentiment swept through Lombardy, culminating in the restoration of Milan in 1169. In 1174 Frederick made his fifth expedition to Italy. (It was probably during this time that the famous ''

Increasing anti-German sentiment swept through Lombardy, culminating in the restoration of Milan in 1169. In 1174 Frederick made his fifth expedition to Italy. (It was probably during this time that the famous ''

"Frederick I (Barbarossa)"

''The Catholic Encyclopedia''. Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909. 21 May 2009. The cities of northern Italy had become exceedingly wealthy through trade, representing a marked turning point in the transition from medieval feudalism. While continental feudalism had remained strong socially and economically, it was in deep political decline by the time of Frederick Barbarossa. When the northern Italian cities inflicted a defeat on Frederick at Frederick did not forgive Henry the Lion for refusing to come to his aid in 1176. By 1180, Henry had successfully established a powerful and contiguous state comprising Saxony, Bavaria, and substantial territories in the north and east of Germany. Taking advantage of the hostility of other German princes to Henry, Frederick had Henry tried in absentia by a court of bishops and princes in 1180, declared that imperial law overruled traditional German law, and had Henry stripped of his lands and declared an outlaw. He then invaded Saxony with an imperial army to force his cousin to surrender. Henry's allies deserted him, and he finally had to submit to Frederick at an Imperial Diet in

Frederick did not forgive Henry the Lion for refusing to come to his aid in 1176. By 1180, Henry had successfully established a powerful and contiguous state comprising Saxony, Bavaria, and substantial territories in the north and east of Germany. Taking advantage of the hostility of other German princes to Henry, Frederick had Henry tried in absentia by a court of bishops and princes in 1180, declared that imperial law overruled traditional German law, and had Henry stripped of his lands and declared an outlaw. He then invaded Saxony with an imperial army to force his cousin to surrender. Henry's allies deserted him, and he finally had to submit to Frederick at an Imperial Diet in

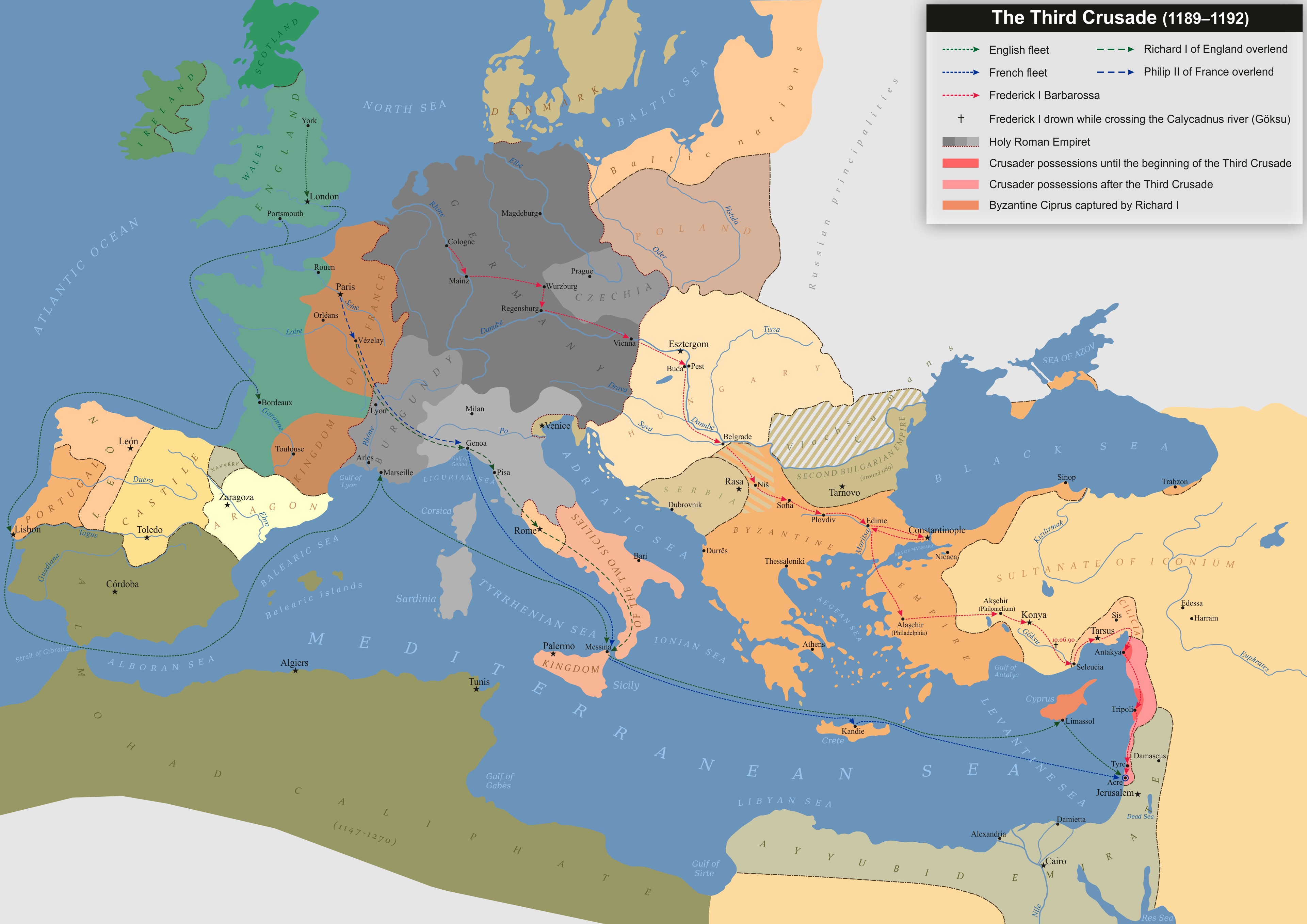

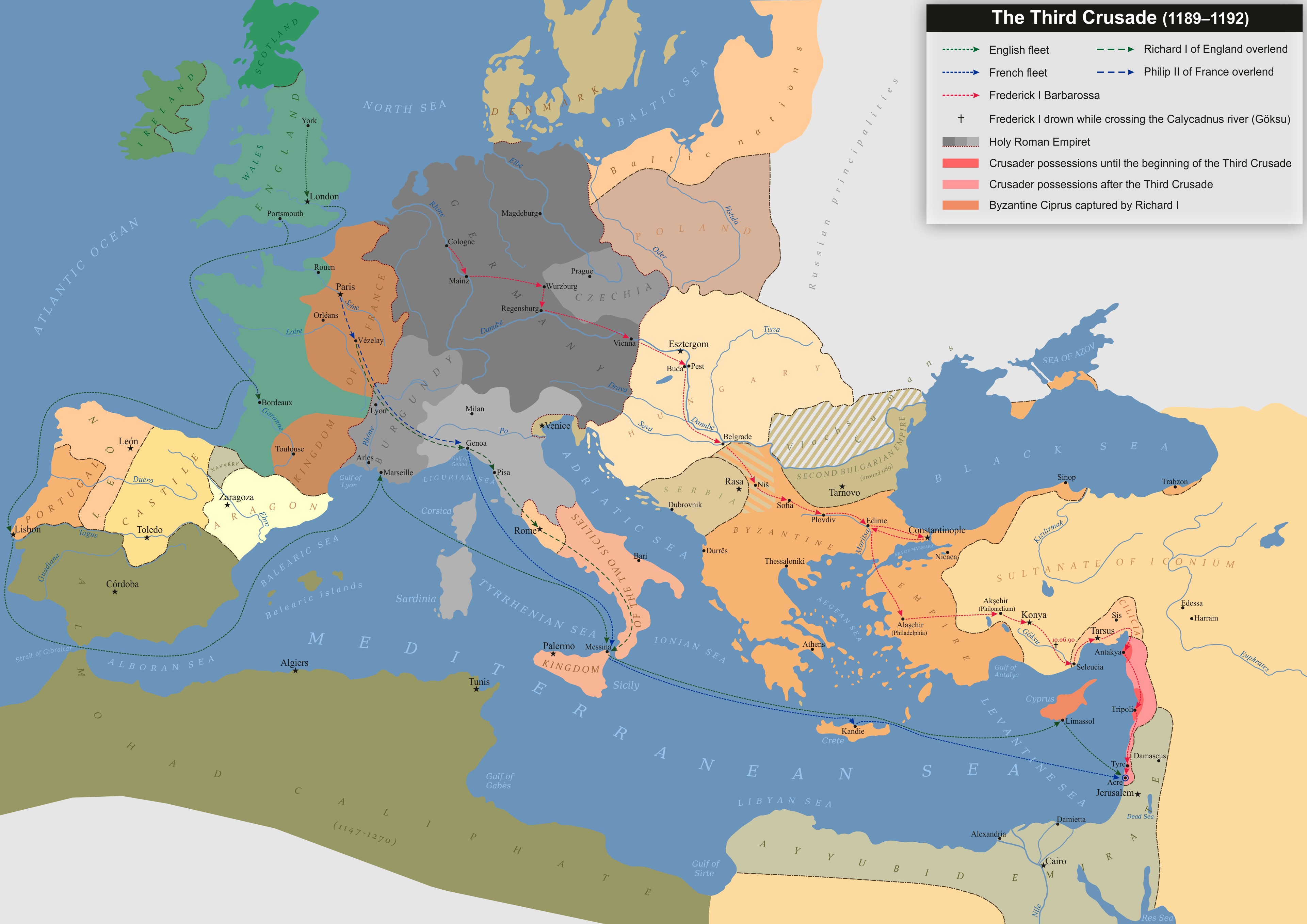

Around 23 November 1187, Frederick received letters that had been sent to him from the rulers of the

Around 23 November 1187, Frederick received letters that had been sent to him from the rulers of the  On 15 April 1189 in

On 15 April 1189 in

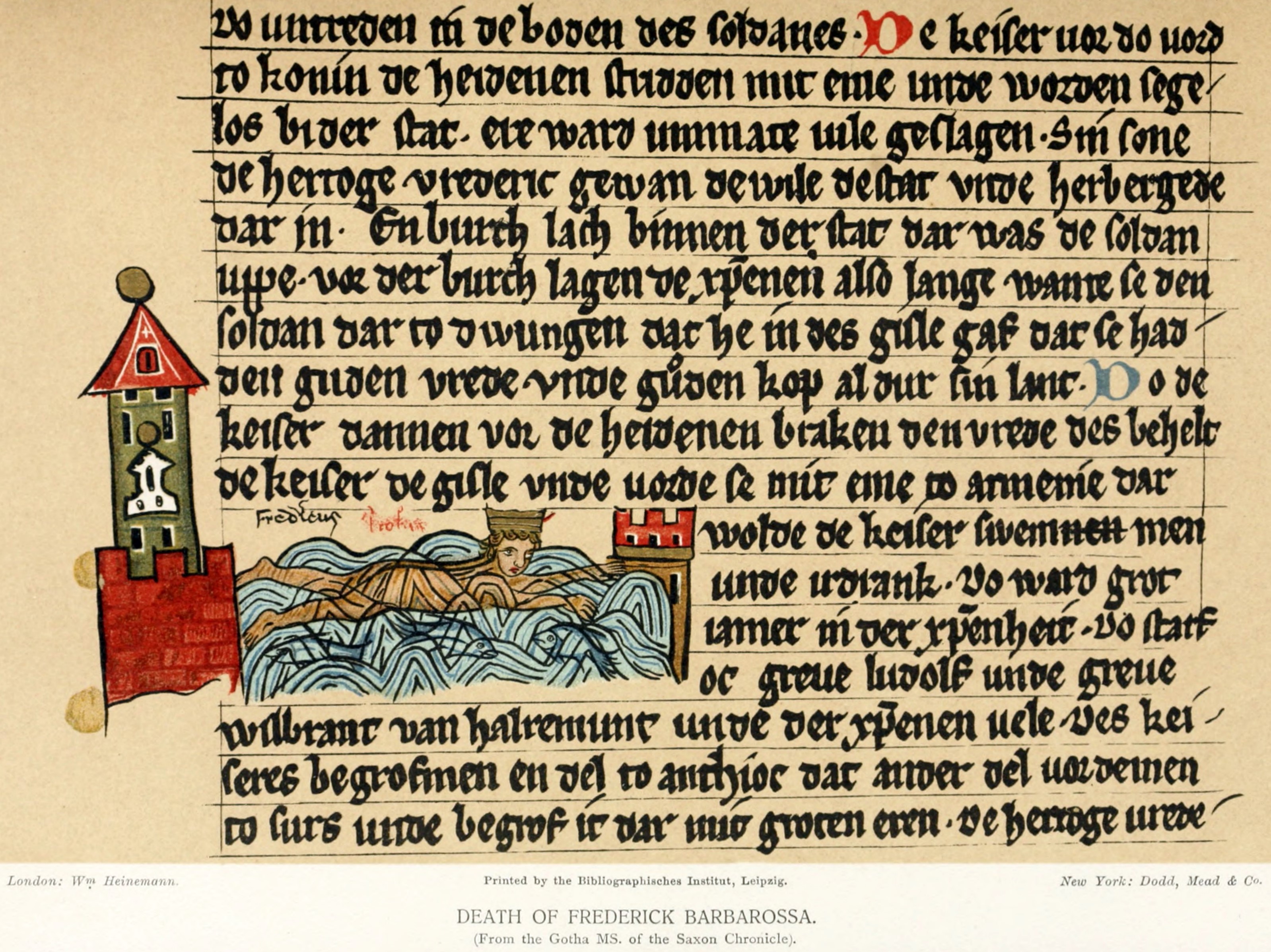

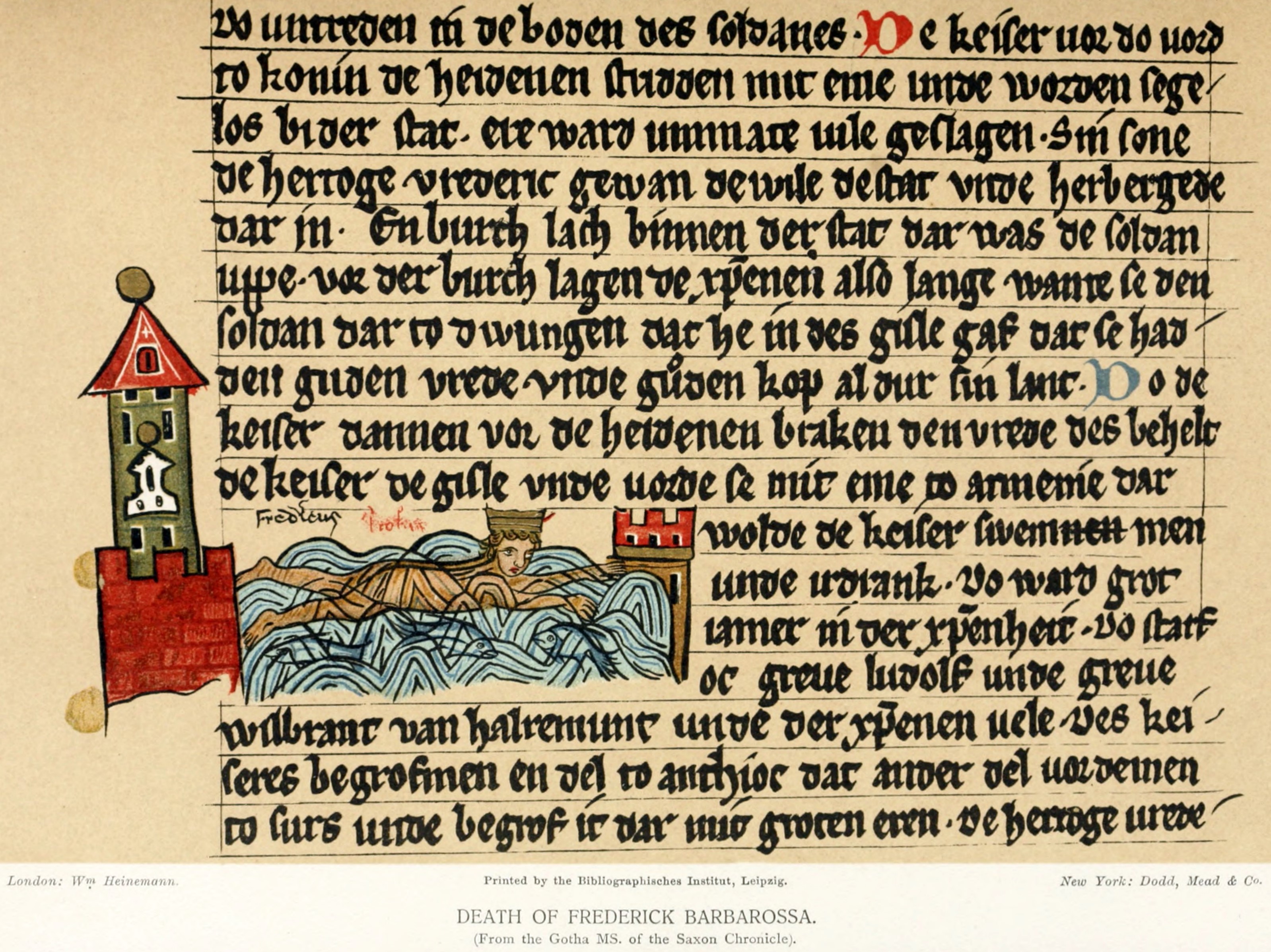

Emperor Frederick Barbarossa opted on the local Armenians' advice to follow a shortcut along the Saleph river. Meanwhile, the army started to traverse the mountain path. On 10 June 1190, he drowned near Silifke Castle in the Saleph river. There are several conflicting accounts of the event:

* According to "History of the Expedition of the Emperor Frederick, Ansbert", against everyone's advice, the emperor chose to swim across the river and was swept away by the current.

* Another account recorded that Frederick was thrown from his horse while crossing the river, weighed down by his armour, and drowned.

* According to the chronicler Ibn al-Athir, "the king went down to the river to wash himself and was drowned at a place where the water was not even up to his waist. Thus God saved us from the evil of such a man".

* The writer of the ''Letter on the Death of the Emperor Frederick'', a churchman who accompanied the crusader forces, reported that "after the many and terrible exertions that he [Frederick I] had undergone in the previous month and more, he decided to bathe in that same river, for he wanted to cool down with a swim. But by the secret judgment of God there was an unexpected and lamentable death and he drowned." Frederick who liked to swim, as he went to bathe with Otto I, Duke of Bavaria, Otto of Wittelsbach in the Adriatic, might have been exhausted from weeks of marching, hence he was fatally affected by the very hot summer in Anatolia. If the writer was Godfrey of Spitzenberg, Bishop of Würzburg, who was a close confidante to Frederick, the report would be the most plausible account of what happened, since he might have witnessed the emperor's death.

Jacques de Vitry, a historian of the Crusades, outlined Frederick's endeavors and Saladin's dilemma, in which he reported:

Frederick's death caused several thousand German soldiers to leave the force and return home through the Cilician and Syrian ports. The German-Hungarian army was struck with an onset of disease near Antioch, weakening it further. Only 5,000 soldiers, a third of the original force, arrived in

Emperor Frederick Barbarossa opted on the local Armenians' advice to follow a shortcut along the Saleph river. Meanwhile, the army started to traverse the mountain path. On 10 June 1190, he drowned near Silifke Castle in the Saleph river. There are several conflicting accounts of the event:

* According to "History of the Expedition of the Emperor Frederick, Ansbert", against everyone's advice, the emperor chose to swim across the river and was swept away by the current.

* Another account recorded that Frederick was thrown from his horse while crossing the river, weighed down by his armour, and drowned.

* According to the chronicler Ibn al-Athir, "the king went down to the river to wash himself and was drowned at a place where the water was not even up to his waist. Thus God saved us from the evil of such a man".

* The writer of the ''Letter on the Death of the Emperor Frederick'', a churchman who accompanied the crusader forces, reported that "after the many and terrible exertions that he [Frederick I] had undergone in the previous month and more, he decided to bathe in that same river, for he wanted to cool down with a swim. But by the secret judgment of God there was an unexpected and lamentable death and he drowned." Frederick who liked to swim, as he went to bathe with Otto I, Duke of Bavaria, Otto of Wittelsbach in the Adriatic, might have been exhausted from weeks of marching, hence he was fatally affected by the very hot summer in Anatolia. If the writer was Godfrey of Spitzenberg, Bishop of Würzburg, who was a close confidante to Frederick, the report would be the most plausible account of what happened, since he might have witnessed the emperor's death.

Jacques de Vitry, a historian of the Crusades, outlined Frederick's endeavors and Saladin's dilemma, in which he reported:

Frederick's death caused several thousand German soldiers to leave the force and return home through the Cilician and Syrian ports. The German-Hungarian army was struck with an onset of disease near Antioch, weakening it further. Only 5,000 soldiers, a third of the original force, arrived in

Frederick is the subject of many legends, including that of a King asleep in mountain, Kyffhäuser legend. Legend says he is not dead, but asleep with his knights in a cave in the Kyffhäuser mountains in Thuringia or Mount Untersberg at the border between Bavaria, Germany, and Salzburg, Austria, and that when the ravens cease to fly around the mountain he will awake and restore Germany to its ancient greatness. According to the story, his red beard has grown through the table at which he sits. His eyes are half closed in sleep, but now and then he raises his hand and sends a boy out to see if the ravens have stopped flying. A similar story, set in Sicily, was earlier attested about his grandson, Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick II. To garner political support the German Empire built atop the Kyffhäuser the Kyffhäuser Monument, which declared Kaiser Wilhelm I the reincarnation of Frederick; the 1896 dedication occurred on 18 June, the day of Frederick's coronation.

In medieval Europe, the Golden Legend became refined by Jacopo da Voragine. This was a popularized interpretation of the Biblical end of the world. It consisted of three things: (1) terrible natural disasters; (2) the arrival of the Antichrist; (3) the establishment of a good king to combat the anti-Christ. These millennial fables were common and freely traded by the populations on Continental Europe. Eschatology, End-time accounts had been around for thousands of years, but entered the Christian tradition with the writings of the Apostle Peter. German propaganda played into the exaggerated fables believed by the common people by characterizing Frederick Barbarossa and Frederick II as personification of the "good king".

Another legend states that when Barbarossa was in the process of seizing Milan in 1158, his wife, the Empress Beatrice, was taken captive by the enraged Milanese and forced to Parading on donkey, ride through the city on a donkey in a humiliating manner. Some sources of this legend indicate that Barbarossa implemented his revenge for this insult by forcing the magistrates of the city to remove a fig from the anus of a donkey using only their teeth. Another source states that Barbarossa took his wrath upon every able-bodied man in the city, and that it was not a fig they were forced to hold in their mouth, but excrement from the donkey. To add to this debasement, they were made to announce, ''"Ecco la fica"'' (meaning "behold the fig"), with the feces still in their mouths. It used to be said that the insulting gesture (called fico), of holding one's fist with the thumb in between the middle and forefinger came by its origin from this event.

Frederick's legend was further reinforced in the early twentieth century, when Adolf Hitler named Nazi Germany's Operation Barbarossa, invasion of the Soviet Union after him.

Frederick is the subject of many legends, including that of a King asleep in mountain, Kyffhäuser legend. Legend says he is not dead, but asleep with his knights in a cave in the Kyffhäuser mountains in Thuringia or Mount Untersberg at the border between Bavaria, Germany, and Salzburg, Austria, and that when the ravens cease to fly around the mountain he will awake and restore Germany to its ancient greatness. According to the story, his red beard has grown through the table at which he sits. His eyes are half closed in sleep, but now and then he raises his hand and sends a boy out to see if the ravens have stopped flying. A similar story, set in Sicily, was earlier attested about his grandson, Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick II. To garner political support the German Empire built atop the Kyffhäuser the Kyffhäuser Monument, which declared Kaiser Wilhelm I the reincarnation of Frederick; the 1896 dedication occurred on 18 June, the day of Frederick's coronation.

In medieval Europe, the Golden Legend became refined by Jacopo da Voragine. This was a popularized interpretation of the Biblical end of the world. It consisted of three things: (1) terrible natural disasters; (2) the arrival of the Antichrist; (3) the establishment of a good king to combat the anti-Christ. These millennial fables were common and freely traded by the populations on Continental Europe. Eschatology, End-time accounts had been around for thousands of years, but entered the Christian tradition with the writings of the Apostle Peter. German propaganda played into the exaggerated fables believed by the common people by characterizing Frederick Barbarossa and Frederick II as personification of the "good king".

Another legend states that when Barbarossa was in the process of seizing Milan in 1158, his wife, the Empress Beatrice, was taken captive by the enraged Milanese and forced to Parading on donkey, ride through the city on a donkey in a humiliating manner. Some sources of this legend indicate that Barbarossa implemented his revenge for this insult by forcing the magistrates of the city to remove a fig from the anus of a donkey using only their teeth. Another source states that Barbarossa took his wrath upon every able-bodied man in the city, and that it was not a fig they were forced to hold in their mouth, but excrement from the donkey. To add to this debasement, they were made to announce, ''"Ecco la fica"'' (meaning "behold the fig"), with the feces still in their mouths. It used to be said that the insulting gesture (called fico), of holding one's fist with the thumb in between the middle and forefinger came by its origin from this event.

Frederick's legend was further reinforced in the early twentieth century, when Adolf Hitler named Nazi Germany's Operation Barbarossa, invasion of the Soviet Union after him.

huge ground artwork

in Bad Frankenhausen, which uses among other things 300 roles of fabric (each was 100 meters long). The mission is named ("Redbeard").

; Secondary sources * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Raoul Manselli, Manselli, Raoul, and Josef Riedmann, eds. ''Federico Barbarossa nel dibattito storiografico in Italia e in Germania''. Bologna: Il Mulino, 1982. * * * * *

MSN Encarta – Frederick I (Holy Roman Empire)

2009-10-31)

Charter given by Emperor Frederick

for the bishopric of Bamberg showing the Emperor's seal, 6 April 1157. Taken from the collections of th

Lichtbildarchiv älterer Originalurkunden

at Marburg University {{DEFAULTSORT:Frederick 1, Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor, 1122 births 1190 deaths 12th-century Holy Roman Emperors 12th-century Kings of the Romans Christians of the Second Crusade Christians of the Third Crusade Deaths by drowning Dukes of Swabia Hohenstaufen People from Haguenau People temporarily excommunicated by the Catholic Church

Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

from 1155 until his death 35 years later. He was elected King of Germany in Frankfurt

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , " Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on it ...

on 4 March 1152 and crowned in Aachen

Aachen ( ; ; Aachen dialect: ''Oche'' ; French and traditional English: Aix-la-Chapelle; or ''Aquisgranum''; nl, Aken ; Polish: Akwizgran) is, with around 249,000 inhabitants, the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the 28th ...

on 9 March 1152. He was crowned King of Italy

King of Italy ( it, links=no, Re d'Italia; la, links=no, Rex Italiae) was the title given to the ruler of the Kingdom of Italy after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The first to take the title was Odoacer, a barbarian military leader ...

on 24 April 1155 in Pavia

Pavia (, , , ; la, Ticinum; Medieval Latin: ) is a town and comune of south-western Lombardy in northern Italy, south of Milan on the lower Ticino river near its confluence with the Po. It has a population of c. 73,086. The city was the ...

and emperor by Pope Adrian IV on 18 June 1155 in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

. Two years later, the term ' ("holy") first appeared in a document in connection with his empire. He was later formally crowned King of Burgundy, at Arles

Arles (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Arle ; Classical la, Arelate) is a coastal city and commune in the South of France, a subprefecture in the Bouches-du-Rhône department of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, in the former province ...

on 30 June 1178. He was named by the northern Italian cities which he attempted to rule: Barbarossa means "red beard" in Italian; in German, he was known as ', which means "Emperor Redbeard" in English. The prevalence of the Italian nickname, even in later German usage, reflects the centrality of the Italian campaigns to his career.

Frederick was by inheritance Duke of Swabia

The Dukes of Swabia were the rulers of the Duchy of Swabia during the Middle Ages. Swabia was one of the five stem duchies of the medieval German kingdom, and its dukes were thus among the most powerful magnates of Germany. The most notable famil ...

(1147–1152, as Frederick III) before his imperial election in 1152. He was the son of Duke Frederick II of the Hohenstaufen

The Hohenstaufen dynasty (, , ), also known as the Staufer, was a noble family of unclear origin that rose to rule the Duchy of Swabia from 1079, and to royal rule in the Holy Roman Empire during the Middle Ages from 1138 until 1254. The dynas ...

dynasty and Judith, daughter of Henry IX, Duke of Bavaria, from the rival House of Welf

The House of Welf (also Guelf or Guelph) is a European dynasty that has included many German and British monarchs from the 11th to 20th century and Emperor Ivan VI of Russia in the 18th century. The originally Franconian family from the Meus ...

. Frederick, therefore, descended from the two leading families in Germany, making him an acceptable choice for the Empire's prince-elector

The prince-electors (german: Kurfürst pl. , cz, Kurfiřt, la, Princeps Elector), or electors for short, were the members of the electoral college that elected the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

From the 13th century onwards, the princ ...

s.

Frederick joined the Third Crusade

The Third Crusade (1189–1192) was an attempt by three European monarchs of Western Christianity ( Philip II of France, Richard I of England and Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor) to reconquer the Holy Land following the capture of Jerusalem by ...

and opted to travel overland to the Holy Land

The Holy Land; Arabic: or is an area roughly located between the Mediterranean Sea and the Eastern Bank of the Jordan River, traditionally synonymous both with the biblical Land of Israel and with the region of Palestine. The term "Holy ...

. In 1190, Frederick drowned attempting to cross the Saleph river leading to most of his army abandoning the Crusade before reaching Acre.

Historians consider him among the Holy Roman Empire's greatest medieval emperors. He combined qualities that made him appear almost superhuman

The term superhuman refers to humans or human-like beings with enhanced qualities and abilities that exceed those naturally found in humans. These qualities may be acquired through natural ability, self-actualization or technological aids. Th ...

to his contemporaries: his longevity, his ambition, his extraordinary skills at organization, his battlefield acumen and his political perspicacity. His contributions to Central European society and culture include the reestablishment of the ', or the Roman rule of law, which counterbalanced the papal power that dominated the German states since the conclusion of the Investiture controversy

The Investiture Controversy, also called Investiture Contest (German: ''Investiturstreit''; ), was a conflict between the Church and the state in medieval Europe over the ability to choose and install bishops ( investiture) and abbots of mona ...

.

Due to his popularity and notoriety, in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, he was used as a political symbol by many movements and regimes: the Risorgimento, the Wilhelmine government in Germany (especially under Emperor Wilhelm I) and the National Socialist

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

(Nazi) movement, resulting in both golden and dark legends. Modern researchers, while exploring the legacy of Frederick, attempt to uncover the legends and reconstruct the true historical figure—these efforts result in new perspectives on both the emperor as a person and social developments associated with him.

Biography

Early life

Frederick was born in mid-December 1122 inHaguenau

Haguenau (; Alsatian language, Alsatian: or ; and historically in English: ''Hagenaw'') is a Communes of France, commune in the Bas-Rhin Département in France, department of France, of which it is a Subprefectures in France, sub-prefecture.

...

, to Frederick II, Duke of Swabia and Judith of Bavaria. He learned to ride, hunt and use weapons, but could neither read nor write, and was also unable to speak the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

language. Later on, he took part in the '' Hoftage'' during the reign of his uncle, King Conrad III

Conrad III (german: Konrad; it, Corrado; 1093 or 1094 – 15 February 1152) of the Hohenstaufen dynasty was from 1116 to 1120 Duke of Franconia, from 1127 to 1135 anti-king of his predecessor Lothair III and from 1138 until his death in 1152 ...

, in 1141 in Strasbourg

Strasbourg (, , ; german: Straßburg ; gsw, label= Bas Rhin Alsatian, Strossburi , gsw, label= Haut Rhin Alsatian, Strossburig ) is the prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est region of eastern France and the official seat of the ...

, 1142 in Konstanz

Konstanz (, , locally: ; also written as Constance in English) is a university city with approximately 83,000 inhabitants located at the western end of Lake Constance in the south of Germany. The city houses the University of Konstanz and was t ...

, 1143 in Ulm

Ulm () is a city in the German state of Baden-Württemberg, situated on the river Danube on the border with Bavaria. The city, which has an estimated population of more than 126,000 (2018), forms an urban district of its own (german: link=no, ...

, 1144 in Würzburg

Würzburg (; Main-Franconian: ) is a city in the region of Franconia in the north of the German state of Bavaria. Würzburg is the administrative seat of the ''Regierungsbezirk'' Lower Franconia. It spans the banks of the Main River.

Würzburg ...

and 1145 in Worms Worms may refer to:

*Worm, an invertebrate animal with a tube-like body and no limbs

Places

*Worms, Germany

Worms () is a city in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, situated on the Upper Rhine about south-southwest of Frankfurt am Main. It had ...

.

Second Crusade

In early 1147, Frederick joined theSecond Crusade

The Second Crusade (1145–1149) was the second major crusade launched from Europe. The Second Crusade was started in response to the fall of the County of Edessa in 1144 to the forces of Zengi. The county had been founded during the First Cru ...

. His uncle, King Conrad III, had taken the crusader vow in public on 28 December 1146. Frederick's father strongly objected to his son's crusade. According to Otto of Freising

Otto of Freising ( la, Otto Frisingensis; c. 1114 – 22 September 1158) was a German churchman of the Cistercian order and chronicled at least two texts which carries valuable information on the political history of his own time. He was Otto I ...

, the duke berated his brother, Conrad III, for permitting his son to go. The elder Frederick, who was dying, expected his son to look after his widow and young half-brother.

Perhaps in preparation for his crusade, Frederick married Adelaide of Vohburg

Adelaide of Vohburg (german: Adela or ''Adelheid''; – 25 May after 1187) was Duchess of Swabia from 1147 and German queen from 1152 until 1153, as the first wife of the Hohenstaufen king Frederick Barbarossa, the later Holy Roman Emperor.

Li ...

sometime before March 1147. His father died on 4 or 6 April and Frederick succeeded to the Duchy of Swabia. The German crusader army departed from Regensburg

Regensburg or is a city in eastern Bavaria, at the confluence of the Danube, Naab and Regen rivers. It is capital of the Upper Palatinate subregion of the state in the south of Germany. With more than 150,000 inhabitants, Regensburg is the ...

seven weeks later.

In August 1147, while crossing the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

, an ill crusader stopped in a monastery outside Adrianople

Edirne (, ), formerly known as Adrianople or Hadrianopolis ( Greek: Άδριανούπολις), is a city in Turkey, in the northwestern part of the province of Edirne in Eastern Thrace. Situated from the Greek and from the Bulgarian border ...

to recuperate. There he was robbed and killed. Conrad ordered Frederick to avenge him. The duke of Swabia razed the monastery, captured and executed the robbers and demanded a return of the stolen money. The intervention of the Byzantine general Prosuch prevented a further escalation.

A few weeks later, on 8 September, Frederick and Welf VI were among the few German crusaders spared when flash flooding destroyed the main camp. They had encamped on a hill away from the main army. The army reached Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

the following day.

Conrad III attempted to lead the army overland across Anatolia. Finding this too difficult in the face of constant Turkish attacks near Dorylaeum, he turned back. The rearguard was subsequently annihilated. Conrad sent Frederick ahead to inform King Louis VII of France

Louis VII (1120 – 18 September 1180), called the Younger, or the Young (french: link=no, le Jeune), was King of the Franks from 1137 to 1180. He was the son and successor of King Louis VI (hence the epithet "the Young") and married Duchess ...

of the disaster and ask for help. The two armies, French and German, then advanced together. When Conrad fell ill at Christmas in Ephesus

Ephesus (; grc-gre, Ἔφεσος, Éphesos; tr, Efes; may ultimately derive from hit, 𒀀𒉺𒊭, Apaša) was a city in ancient Greece on the coast of Ionia, southwest of present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built i ...

, he returned to Constantinople by ship with his main followers, including Frederick.

With Byzantine ships and money, the German army left Constantinople on 7 March 1148 and arrived in Acre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial and US customary systems. It is traditionally defined as the area of one chain by one furlong (66 by 660 feet), which is exactly equal to 10 square chains, of a square mile, 4,840 square ...

on 11 April. After Easter, Conrad and Frederick visited Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

, where Frederick was impressed by the charitable works of the Knights Hospitaller

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic military order. It was headq ...

. He took part in the council that was held at Palmarea on 24 June, where it was decided to attack Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

.

The Siege of Damascus (24–28 July) lasted a mere five days and ended in ignominious defeat. Gilbert of Mons, writing fifty years later, recorded that Frederick "prevailed in arms before all others in front of Damascus". On 8 September, the German army sailed out of Acre.

On the route home, Conrad III and Frederick stopped in Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

where they swore oaths to uphold the treaty that Conrad had agreed with Emperor Manuel I Komnenos

Manuel I Komnenos ( el, Μανουήλ Κομνηνός, translit=Manouíl Komnenos, translit-std=ISO; 28 November 1118 – 24 September 1180), Latinized Comnenus, also called Porphyrogennetos (; " born in the purple"), was a Byzantine empero ...

the previous winter. This treaty obligated the Germans to attack King Roger II of Sicily

Roger II ( it, Ruggero II; 22 December 1095 – 26 February 1154) was King of Sicily and Africa, son of Roger I of Sicily and successor to his brother Simon. He began his rule as Count of Sicily in 1105, became Duke of Apulia and Calabria i ...

in cooperation with the Byzantines. After confirming the treaty, Frederick was sent ahead to Germany. He passed through Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

and Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Cr ...

and arrived in Germany in April 1149.

Election

When Conrad died in February 1152, only Frederick and the prince-bishop of Bamberg were at his deathbed. Both asserted afterwards that Conrad had, in full possession of his mental powers, handed the royal insignia to Frederick and indicated that Frederick, rather than Conrad's own six-year-old son, the futureFrederick IV, Duke of Swabia

Frederick IV of Hohenstaufen (1145–1167) was duke of Swabia, succeeding his cousin, Frederick Barbarossa, Holy Roman Emperor, in 1152.

He was the son of Conrad III of Germany and his second wife Gertrude von Sulzbach and thus the direct hei ...

, succeed him as king. Frederick energetically pursued the crown and at Frankfurt

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , " Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on it ...

on 4 March 1152 the kingdom's princely electors designated him as the next German king.

He was crowned King of the Romans

King of the Romans ( la, Rex Romanorum; german: König der Römer) was the title used by the king of Germany following his election by the princes from the reign of Henry II (1002–1024) onward.

The title originally referred to any German k ...

at Aachen

Aachen ( ; ; Aachen dialect: ''Oche'' ; French and traditional English: Aix-la-Chapelle; or ''Aquisgranum''; nl, Aken ; Polish: Akwizgran) is, with around 249,000 inhabitants, the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the 28th ...

several days later, on 9 March 1152. Frederick's father was from the Hohenstaufen

The Hohenstaufen dynasty (, , ), also known as the Staufer, was a noble family of unclear origin that rose to rule the Duchy of Swabia from 1079, and to royal rule in the Holy Roman Empire during the Middle Ages from 1138 until 1254. The dynas ...

family, and his mother was from the Welf family, the two most powerful families in Germany. The Hohenstaufens were often called Ghibellines

The Guelphs and Ghibellines (, , ; it, guelfi e ghibellini ) were factions supporting the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, respectively, in the Italian city-states of Central Italy and Northern Italy.

During the 12th and 13th centuries, r ...

, which derives from the Italianized name for Waiblingen

Waiblingen (; Swabian: ''Woeblinge'') is a town in the southwest of Germany, located in the center of the densely populated Stuttgart region, directly neighboring Stuttgart. It is the capital and largest city of the Rems-Murr district. , Wai ...

castle, the family seat in Swabia; the Welfs, in a similar Italianization, were called Guelfs

The House of Welf (also Guelf or Guelph) is a European dynasty that has included many German and British monarchs from the 11th to 20th century and Emperor Ivan VI of Russia in the 18th century. The originally Franconian family from the Meus ...

.

Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (c. 1173–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (121 ...

left the status of the German empire in disarray, its power waning under the weight of the Investiture controversy

The Investiture Controversy, also called Investiture Contest (German: ''Investiturstreit''; ), was a conflict between the Church and the state in medieval Europe over the ability to choose and install bishops ( investiture) and abbots of mona ...

. For a quarter of a century following the death of Henry V in 1125, the German monarchy was largely a nominal title with no real power. The king was chosen by the princes, was given no resources outside those of his own duchy, and he was prevented from exercising any real authority or leadership in the realm. The royal title was furthermore passed from one family to another to preclude the development of any dynastic interest in the German crown. When Frederick I of Hohenstaufen was chosen as king in 1152, royal power had been in effective abeyance for over twenty-five years, and to a considerable degree for more than eighty years. The only real claim to wealth lay in the rich cities of northern Italy, which were still within the nominal control of the German king. The Salian line had died out with the death of Henry V in 1125. The German princes refused to give the crown to his nephew, the duke of Swabia, for fear he would try to regain the imperial power held by Henry V. Instead, they chose Lothair III

Lothair III, sometimes numbered Lothair II and also known as Lothair of Supplinburg (1075 – 4 December 1137), was Holy Roman Emperor from 1133 until his death. He was appointed Duke of Saxony in 1106 and elected King of Germany in 1125 before b ...

(1125–1137), who found himself embroiled in a long-running dispute with the Hohenstaufens, and who married into the Welfs. One of the Hohenstaufens gained the throne as Conrad III of Germany

Conrad III (german: Konrad; it, Corrado; 1093 or 1094 – 15 February 1152) of the Hohenstaufen dynasty was from 1116 to 1120 Duke of Franconia, from 1127 to 1135 anti-king of his predecessor Lothair III and from 1138 until his death in 1152 ...

(1137–1152). When Frederick Barbarossa succeeded his uncle in 1152, there seemed to be excellent prospects for ending the feud, since he was a Welf on his mother's side. The Welf duke of Saxony, Henry the Lion

Henry the Lion (german: Heinrich der Löwe; 1129/1131 – 6 August 1195) was a member of the Welf dynasty who ruled as the duke of Saxony and Bavaria from 1142 and 1156, respectively, until 1180.

Henry was one of the most powerful German p ...

, would not be appeased, however, remaining an implacable enemy of the Hohenstaufen monarchy. Barbarossa had the duchies of Swabia and Franconia, the force of his own personality, and very little else to construct an empire.

The Germany that Frederick tried to unite was a patchwork of more than 1,600 individual states, each with its own prince. A few of these, such as Bavaria and Saxony, were large. Many were too small to pinpoint on a map. The titles afforded to the German king were "Caesar", "Augustus", and "Emperor of the Romans". By the time Frederick would assume these, they were little more than propaganda slogans with little other meaning. Frederick was a pragmatist who dealt with the princes by finding a mutual self-interest. Unlike Henry II of England

Henry II (5 March 1133 – 6 July 1189), also known as Henry Curtmantle (french: link=no, Court-manteau), Henry FitzEmpress, or Henry Plantagenet, was King of England from 1154 until his death in 1189, and as such, was the first Angevin kin ...

, Frederick did not attempt to end medieval feudalism, but rather tried to restore it, though this was beyond his ability. The great players in the German civil war had been the Pope, Emperor, Ghibellines and the Guelfs, but none of these had emerged as the winner.

Rise to power

Eager to restore the Empire to the position it had occupied under

Eager to restore the Empire to the position it had occupied under Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first E ...

and Otto I the Great, the new king saw clearly that the restoration of order in Germany was a necessary preliminary to the enforcement of the imperial rights in Italy. Issuing a general order for peace, he made lavish concessions to the nobles. Abroad, Frederick intervened in the Danish civil war between Svend III and Valdemar I of Denmark

Valdemar I (14 January 1131 – 12 May 1182), also known as Valdemar the Great ( da, Valdemar den Store), was King of Denmark from 1154 until his death in 1182. The reign of King Valdemar I saw the rise of Denmark, which reached its medieval ze ...

and began negotiations with the Eastern Roman Emperor, Manuel I Comnenus. It was probably about this time that the king obtained papal assent for the annulment of his childless marriage with Adelheid of Vohburg

Adelaide of Vohburg (german: Adela or ''Adelheid''; – 25 May after 1187) was Duchess of Swabia from 1147 and German queen from 1152 until 1153, as the first wife of the Hohenstaufen king Frederick Barbarossa, the later Holy Roman Emperor.

Li ...

, on the grounds of consanguinity

Consanguinity ("blood relation", from Latin '' consanguinitas'') is the characteristic of having a kinship with another person (being descended from a common ancestor).

Many jurisdictions have laws prohibiting people who are related by blood fr ...

(his great-great-grandfather was a brother of Adela's great-great-great-grandmother, making them fourth cousins, once removed). He then made a vain attempt to obtain a bride from the court of Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

. On his accession, Frederick had communicated the news of his election to Pope Eugene III, but had neglected to ask for papal confirmation. In March 1153, Frederick concluded the Treaty of Constance

The Peace of Constance (25 June 1183) was a privilege granted by Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor, and his son and co-ruler, Henry VI, King of the Romans, to the members of the Lombard League to end the state of rebellion (war) that had been ong ...

with the Pope, wherein he promised, in return for his coronation, to defend the papacy, to make no peace with king Roger II of Sicily

Roger II ( it, Ruggero II; 22 December 1095 – 26 February 1154) was King of Sicily and Africa, son of Roger I of Sicily and successor to his brother Simon. He began his rule as Count of Sicily in 1105, became Duke of Apulia and Calabria i ...

or other enemies of the Church without the consent of Eugene, and to help Eugene regain control of the city of Rome.

First Italian Campaign: 1154–55

Frederick undertook six expeditions into Italy. In the first, beginning in October 1154, his plan was to launch a campaign against theNormans

The Normans ( Norman: ''Normaunds''; french: Normands; la, Nortmanni/Normanni) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norse Viking settlers and indigenous West Franks and Gallo-Romans. ...

under King William I of Sicily. He marched down and almost immediately encountered resistance to his authority. Obtaining the submission of Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city ...

, he successfully besieged Tortona

Tortona (; pms, Torton-a , ; lat, Dhertona) is a '' comune'' of Piemonte, in the Province of Alessandria, Italy. Tortona is sited on the right bank of the Scrivia between the plain of Marengo and the foothills of the Ligurian Apennines.

Histor ...

on 13 February 1155, razing it to the ground on 18 April. He moved on to Pavia

Pavia (, , , ; la, Ticinum; Medieval Latin: ) is a town and comune of south-western Lombardy in northern Italy, south of Milan on the lower Ticino river near its confluence with the Po. It has a population of c. 73,086. The city was the ...

, where he according to some historians he received the Iron Crown and the title of King of Italy

King of Italy ( it, links=no, Re d'Italia; la, links=no, Rex Italiae) was the title given to the ruler of the Kingdom of Italy after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The first to take the title was Odoacer, a barbarian military leader ...

on 24 April in the Basilica of San Michele Maggiore. Others historians instead suggest his coronation took place in Monza

Monza (, ; lmo, label= Lombard, Monça, locally ; lat, Modoetia) is a city and ''comune'' on the River Lambro, a tributary of the Po in the Lombardy region of Italy, about north-northeast of Milan. It is the capital of the Province of Mo ...

on 15 April. Moving through Bologna

Bologna (, , ; egl, label= Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bononia) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different na ...

and Tuscany

it, Toscano (man) it, Toscana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Citizenship

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 = Italian

, demogra ...

, he was soon approaching the city of Rome. There, Pope Adrian IV was struggling with the forces of the republican city commune led by Arnold of Brescia

Arnold of Brescia ( 1090 – June 1155), also known as Arnaldus ( it, Arnaldo da Brescia), an Italian canon regular from Lombardy, called on the Church to renounce property-ownership and participated in the failed Commune of Rome of 1144– ...

, a student of Abelard

Peter Abelard (; french: link=no, Pierre Abélard; la, Petrus Abaelardus or ''Abailardus''; 21 April 1142) was a Middle Ages, medieval French Scholasticism, scholastic philosopher, leading logician, theologian, poet, composer and musician. This ...

. As a sign of good faith, Frederick dismissed the ambassadors from the revived Roman Senate, and Imperial forces suppressed the republicans. Arnold was captured and hanged for treason and rebellion. Despite his unorthodox teaching concerning theology, Arnold was not charged with heresy.

As Frederick approached the gates of Rome, the Pope advanced to meet him. At the royal tent the king received him, and after kissing the pope's feet, Frederick expected to receive the traditional kiss of peace. Frederick had declined to hold the Pope's stirrup while leading him to the tent, however, so Adrian refused to give the kiss until this protocol had been complied with. Frederick hesitated, and Adrian IV withdrew; after a day's negotiation, Frederick agreed to perform the required ritual, reportedly muttering, "''Pro Petro, non Adriano'' – For Peter, not for Adrian." Rome was still in an uproar over the fate of Arnold of Brescia, so rather than marching through the streets of Rome, Frederick and Adrian retired to the Vatican.

As Frederick approached the gates of Rome, the Pope advanced to meet him. At the royal tent the king received him, and after kissing the pope's feet, Frederick expected to receive the traditional kiss of peace. Frederick had declined to hold the Pope's stirrup while leading him to the tent, however, so Adrian refused to give the kiss until this protocol had been complied with. Frederick hesitated, and Adrian IV withdrew; after a day's negotiation, Frederick agreed to perform the required ritual, reportedly muttering, "''Pro Petro, non Adriano'' – For Peter, not for Adrian." Rome was still in an uproar over the fate of Arnold of Brescia, so rather than marching through the streets of Rome, Frederick and Adrian retired to the Vatican.

Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

at St Peter's Basilica

The Papal Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican ( it, Basilica Papale di San Pietro in Vaticano), or simply Saint Peter's Basilica ( la, Basilica Sancti Petri), is a Church (building), church built in the Renaissance architecture, Renaissanc ...

, amidst the acclamations of the German army. The Romans began to riot, and Frederick spent his coronation day putting down the revolt, resulting in the deaths of over 1,000 Romans and many more thousands injured. The next day, Frederick, Adrian, and the German army travelled to Tivoli

Tivoli may refer to:

* Tivoli, Lazio, a town in Lazio, Italy, known for historic sites; the inspiration for other places named Tivoli

Buildings

* Tivoli (Baltimore, Maryland), a mansion built about 1855

* Tivoli Building (Cheyenne, Wyoming), ...

. From there, a combination of the unhealthy Italian summer and the effects of his year-long absence from Germany meant he was forced to put off his planned campaign against the Normans of Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

. On their way northwards, they attacked Spoleto

Spoleto (, also , , ; la, Spoletum) is an ancient city in the Italian province of Perugia in east-central Umbria on a foothill of the Apennines. It is S. of Trevi, N. of Terni, SE of Perugia; SE of Florence; and N of Rome.

History

Sp ...

and encountered the ambassadors of Manuel I Comnenus, who showered Frederick with costly gifts. At Verona

Verona ( , ; vec, Verona or ) is a city on the Adige River in Veneto, Italy, with 258,031 inhabitants. It is one of the seven provincial capitals of the region. It is the largest city municipality in the region and the second largest in nor ...

, Frederick declared his fury with the rebellious Milanese before finally returning to Germany.

Disorder was again rampant in Germany, especially in Bavaria, but general peace was restored by Frederick's vigorous, but conciliatory, measures. The duchy of Bavaria was transferred from Henry II Jasomirgott, margrave of Austria, to Frederick's formidable younger cousin Henry the Lion

Henry the Lion (german: Heinrich der Löwe; 1129/1131 – 6 August 1195) was a member of the Welf dynasty who ruled as the duke of Saxony and Bavaria from 1142 and 1156, respectively, until 1180.

Henry was one of the most powerful German p ...

, Duke of Saxony

This article lists dukes, electors, and kings ruling over different territories named Saxony from the beginning of the Saxon Duchy in the 6th century to the end of the German monarchies in 1918.

The electors of Saxony from John the Steadfast on ...

, of the House of Guelph, whose father had previously held both duchies. Henry II Jasomirgott was named Duke of Austria

This is a list of people who have ruled either the Margraviate of Austria, the Duchy of Austria or the Archduchy of Austria. From 976 until 1246, the margraviate and its successor, the duchy, was ruled by the House of Babenberg. At that time, ...

in compensation for his loss of Bavaria. As part of his general policy of concessions of formal power to the German princes and ending the civil wars within the kingdom, Frederick further appeased Henry by issuing him with the Privilegium Minus, granting him unprecedented entitlements as Duke of Austria. This was a large concession on the part of Frederick, who realized that Henry the Lion had to be accommodated, even to the point of sharing some power with him. Frederick could not afford to make an outright enemy of Henry.

On 9 June 1156 at Würzburg

Würzburg (; Main-Franconian: ) is a city in the region of Franconia in the north of the German state of Bavaria. Würzburg is the administrative seat of the ''Regierungsbezirk'' Lower Franconia. It spans the banks of the Main River.

Würzburg ...

, Frederick married Beatrice of Burgundy, daughter and heiress of Renaud III, thus adding to his possessions the sizeable realm of the County of Burgundy. In an attempt to create comity, Emperor Frederick proclaimed the Peace of the Land, written between 1152 and 1157, which enacted punishments for a variety of crimes, as well as systems for adjudicating many disputes. He also declared himself the sole Augustus of the Roman world, ceasing to recognise Manuel I at Constantinople.

Second, Third and Fourth Italian Campaigns: 1158–1174

The retreat of Frederick in 1155 forced Pope Adrian IV to come to terms with King William I of Sicily, granting to William I territories that Frederick viewed as his dominion. This aggrieved Frederick, and he was further displeased when

The retreat of Frederick in 1155 forced Pope Adrian IV to come to terms with King William I of Sicily, granting to William I territories that Frederick viewed as his dominion. This aggrieved Frederick, and he was further displeased when Papal legate

300px, A woodcut showing Henry II of England greeting the pope's legate.

A papal legate or apostolic legate (from the ancient Roman title '' legatus'') is a personal representative of the pope to foreign nations, or to some part of the Catholic ...

s chose to interpret a letter from Adrian to Frederick in a manner that seemed to imply that the imperial crown was a gift from the Papacy

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

and that in fact the Empire itself was a fief

A fief (; la, feudum) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form ...

of the Papacy. Disgusted with the pope, and still wishing to crush the Normans in the south of Italy, in June 1158, Frederick set out upon his second Italian expedition, accompanied by Henry the Lion

Henry the Lion (german: Heinrich der Löwe; 1129/1131 – 6 August 1195) was a member of the Welf dynasty who ruled as the duke of Saxony and Bavaria from 1142 and 1156, respectively, until 1180.

Henry was one of the most powerful German p ...

and his Saxon troops. This expedition resulted in the revolt and capture of Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city ...

, the Diet of Roncaglia that saw the establishment of imperial officers and ecclesiastical reforms in the cities of northern Italy, and the beginning of the long struggle with Pope Alexander III

Pope Alexander III (c. 1100/1105 – 30 August 1181), born Roland ( it, Rolando), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 7 September 1159 until his death in 1181.

A native of Siena, Alexander became pope after a con ...

. Milan soon rebelled again and humiliated Empress Beatrice (see Legend below).

The death of Pope Adrian IV in 1159 led to the election of two rival popes, Alexander III and the antipope

An antipope ( la, antipapa) is a person who makes a significant and substantial attempt to occupy the position of Bishop of Rome and leader of the Catholic Church in opposition to the legitimately elected pope. At times between the 3rd and mi ...

Victor IV, and both sought Frederick's support. Frederick, busy with the siege of Crema

The siege of Crema was a siege of the town of Crema, Lombardy by the Holy Roman Empire from 2 July 1159 to 25 January 1160. The Cremaschi attempted to defend their city from the Germans, but were eventually defeated by Frederick Barbarossa's men ...

, appeared unsupportive of Alexander III, and after the sacking of Crema demanded that Alexander appear before the emperor at Pavia and to accept the imperial decree. Alexander refused, and Frederick recognised Victor IV as the legitimate pope in 1160. In response, Alexander III excommunicate

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

d both Frederick I and Victor IV. Frederick attempted to convoke a joint council with King Louis VII of France in 1162 to decide the issue of who should be pope. Louis neared the meeting site, but when he became aware that Frederick had stacked the votes for Alexander, Louis decided not to attend the council. As a result, the issue was not resolved at that time.

The political result of the struggle with Pope Alexander was an alliance formed between the Norman state of Sicily and Pope Alexander III against Frederick. In the meantime, Frederick had to deal with another rebellion at Milan, in which the city surrendered on 6 March 1162; much of it was destroyed three weeks later on the emperor's orders. The fate of Milan led to the submission of Brescia

Brescia (, locally ; lmo, link=no, label= Lombard, Brèsa ; lat, Brixia; vec, Bressa) is a city and '' comune'' in the region of Lombardy, Northern Italy. It is situated at the foot of the Alps, a few kilometers from the lakes Garda and Iseo ...

, Placentia, and many other northern Italian cities. In August 1162 he entered triumphally Turin and was crowned with his consort in the cathedral on August 15. Returning to Germany towards the close of 1162, Frederick prevented the escalation of conflicts between Henry the Lion from Saxony and a number of neighbouring princes who were growing weary of Henry's power, influence, and territorial gains. He also severely punished the citizens of Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-west, with Ma ...

for their rebellion against Archbishop Arnold. In Frederick's third visit to Italy in 1163, his plans for the conquest of Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

were ruined by the formation of a powerful league against him, brought together mainly by opposition to imperial taxes.

In 1164 Frederick took what are believed to be the relics

In religion, a relic is an object or article of religious significance from the past. It usually consists of the physical remains of a saint or the personal effects of the saint or venerated person preserved for purposes of veneration as a tangi ...

of the "Biblical Magi" (the Wise Men or Three Kings

The biblical Magi from Middle Persian ''moɣ''(''mard'') from Old Persian ''magu-'' 'Zoroastrian clergyman' ( or ; singular: ), also referred to as the (Three) Wise Men or (Three) Kings, also the Three Magi were distinguished foreigners in the ...

) from the Basilica di Sant'Eustorgio

The Basilica of Sant'Eustorgio is a church in Milan in northern Italy, which is in the Basilicas Park city park. It was for many years an important stop for pilgrims on their journey to Rome or to the Holy Land, because it was said to contain th ...

in Milan and gave them as a gift (or as loot) to the Archbishop of Cologne

The Archbishop of Cologne is an archbishop governing the Archdiocese of Cologne of the Catholic Church in western North Rhine-Westphalia and is also a historical state in the Rhine holding the birthplace of Beethoven and northern Rhineland-Palat ...

, Rainald of Dassel

Rainald of Dassel (c. 1120 – 14 August 1167) was Archbishop of Cologne and Archchancellor of Italy from 1159 until his death. A close advisor to the Hohenstaufen emperor Frederick Barbarossa, he had an important influence on Imperial po ...

. The relics had great religious significance and could be counted upon to draw pilgrims from all over Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwin ...

. Today they are kept in the Shrine of the Three Kings in the Cologne cathedral

Cologne Cathedral (german: Kölner Dom, officially ', English: Cathedral Church of Saint Peter) is a Catholic cathedral in Cologne, North Rhine-Westphalia. It is the seat of the Archbishop of Cologne and of the administration of the Archdiocese ...

. After the death of the antipope Victor IV, Frederick supported antipope Paschal III

Antipope Paschal III (or Paschal III) () was a 12th-century clergyman who, from 1164 to 1168, was the second antipope to challenge the reign of Pope Alexander III. He had previously served as Cardinal of St. Maria.

Biography

Born Guido of Crem ...

, but he was soon driven from Rome, leading to the return of Pope Alexander III in 1165.

In the meantime Frederick was focused on restoring peace in the Rhineland, where he organized a magnificent celebration of the

In the meantime Frederick was focused on restoring peace in the Rhineland, where he organized a magnificent celebration of the canonization

Canonization is the declaration of a deceased person as an officially recognized saint, specifically, the official act of a Christian communion declaring a person worthy of public veneration and entering their name in the canon catalogue of ...

of Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first E ...

at Aachen, under the authority of the antipope Paschal III. Concerned over rumours that Alexander III was about to enter into an alliance with the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I, in October 1166 Frederick embarked on his fourth Italian campaign, hoping as well to secure the claim of Paschal III and the coronation of his wife Beatrice as Holy Roman Empress. This time, Henry the Lion refused to join Frederick on his Italian trip, tending instead to his own disputes with neighbors and his continuing expansion into Slavic territories in northeastern Germany. In 1167 Frederick began besieging Ancona

Ancona (, also , ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region in central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona and of the region. The city is located northeast of Rome, on the Adriatic ...

, which had acknowledged the authority of Manuel I; at the same time, his forces achieved a great victory over the Romans at the Battle of Monte Porzio. Heartened by this victory, Frederick lifted the siege of Ancona and hurried to Rome, where he had his wife crowned empress and also received a second coronation from Paschal III. Unfortunately, his campaign was halted by the sudden outbreak of an epidemic (malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

or the plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pes ...

), which threatened to destroy the Imperial army and drove the emperor as a fugitive to Germany, where he remained for the ensuing six years. During this period, Frederick decided conflicting claims to various bishoprics, asserted imperial authority over Bohemia, Poland, and Hungary, initiated friendly relations with Manuel I, and tried to come to a better understanding with Henry II of England and Louis VII of France. Many Swabian counts, including his cousin the young Duke of Swabia, Frederick IV, died in 1167, so he was able to organize a new mighty territory in the Duchy of Swabia under his reign in this time. Consequently, his younger son Frederick V became the new Duke of Swabia in 1167, while his eldest son Henry was crowned King of the Romans

King of the Romans ( la, Rex Romanorum; german: König der Römer) was the title used by the king of Germany following his election by the princes from the reign of Henry II (1002–1024) onward.

The title originally referred to any German k ...

in 1169, alongside his father who also retained the title.

Later years

Increasing anti-German sentiment swept through Lombardy, culminating in the restoration of Milan in 1169. In 1174 Frederick made his fifth expedition to Italy. (It was probably during this time that the famous ''

Increasing anti-German sentiment swept through Lombardy, culminating in the restoration of Milan in 1169. In 1174 Frederick made his fifth expedition to Italy. (It was probably during this time that the famous ''Tafelgüterverzeichnis

The ''Tafelgüterverzeichnis'' is a list of the "courts which belong to the table of the king of the Romans" (''curie que pertinent ad mensam regis Romanorum''), that is, a register of the lands belonging to the royal demesne (or fisc) and of t ...

'', a record of the royal estates, was made.) He was opposed by the pro-papal Lombard League (now joined by Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

, Sicily and Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

), which had previously formed to stand against him.Kampers, Franz"Frederick I (Barbarossa)"

''The Catholic Encyclopedia''. Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909. 21 May 2009. The cities of northern Italy had become exceedingly wealthy through trade, representing a marked turning point in the transition from medieval feudalism. While continental feudalism had remained strong socially and economically, it was in deep political decline by the time of Frederick Barbarossa. When the northern Italian cities inflicted a defeat on Frederick at

Alessandria

Alessandria (; pms, Lissandria ) is a city and ''comune'' in Piedmont, Italy, and the capital of the Province of Alessandria. The city is sited on the alluvial plain between the Tanaro and the Bormida rivers, about east of Turin.

Alessandri ...

in 1175, the European world was shocked. With the refusal of Henry the Lion to bring help to Italy, the campaign was a complete failure. Frederick suffered a heavy defeat at the Battle of Legnano

The Battle of Legnano was a battle between the imperial army of Frederick Barbarossa and the troops of the Lombard League on May 29, 1176, near the town of Legnano in present-day Lombardy, in Italy. Although the presence of the enemy nearby w ...

near Milan, on 29 May 1176, where he was wounded and for some time was believed to be dead. This battle marked the turning point in Frederick's claim to empire. He had no choice other than to begin negotiations for peace with Alexander III and the Lombard League. In the Peace of Anagni in 1176, Frederick recognized Alexander III as pope, and in the Peace of Venice

The Treaty or Peace of Venice, 1177, was a peace treaty between the papacy and its allies, the north Italian city-states of the Lombard League, and Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor. The Norman Kingdom of Sicily also took part in negotiations and ...

in 1177, Frederick and Alexander III were formally reconciled. With decisions of Paschal III nullfied, Beatrice ceased to be referred as empress.

The scene was similar to that which had occurred between Pope Gregory VII

Pope Gregory VII ( la, Gregorius VII; 1015 – 25 May 1085), born Hildebrand of Sovana ( it, Ildebrando di Soana), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 22 April 1073 to his death in 1085. He is venerated as a saint ...

and Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor

Henry IV (german: Heinrich IV; 11 November 1050 – 7 August 1106) was Holy Roman Emperor from 1084 to 1105, King of Germany from 1054 to 1105, King of Italy and Burgundy from 1056 to 1105, and Duke of Bavaria from 1052 to 1054. He was the ...

at Canossa

Canossa ( Reggiano: ) is a '' comune'' and castle town in the Province of Reggio Emilia, Emilia-Romagna, northern Italy. It is where Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV did penance in 1077 and stood three days bare-headed in the snow to reverse his ...

a century earlier. The conflict was the same as that resolved in the Concordat of Worms

The Concordat of Worms(; ) was an agreement between the Catholic Church and the Holy Roman Empire which regulated the procedure for the appointment of bishops and abbots in the Empire. Signed on 23 September 1122 in the German city of Worms by ...

: Did the Holy Roman Emperor have the power to name the pope and bishops? The Investiture controversy

The Investiture Controversy, also called Investiture Contest (German: ''Investiturstreit''; ), was a conflict between the Church and the state in medieval Europe over the ability to choose and install bishops ( investiture) and abbots of mona ...

from previous centuries had been brought to a tendentious peace with the Concordat of Worms and affirmed in the First Council of the Lateran. Now it had recurred, in a slightly different form. Frederick had to humble himself before Alexander III at Venice. The emperor acknowledged the pope's sovereignty over the Papal States, and in return Alexander acknowledged the emperor's overlordship of the Imperial Church. Also in the Peace of Venice, a truce was made with the Lombard cities, which took effect in August 1178. The grounds for a permanent peace were not established until 1183, however, in the Peace of Constance

The Peace of Constance (25 June 1183) was a privilege granted by Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor, and his son and co-ruler, Henry VI, King of the Romans, to the members of the Lombard League to end the state of rebellion (war) that had been ong ...

, when Frederick conceded their right to freely elect town magistrates. By this move, Frederick recovered his nominal domination over Italy, which became his chief means of applying pressure on the papacy.

In a move to consolidate his reign after the disastrous expedition into Italy, Frederick was formally crowned King of Burgundy at Arles

Arles (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Arle ; Classical la, Arelate) is a coastal city and commune in the South of France, a subprefecture in the Bouches-du-Rhône department of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, in the former province ...

on 30 June 1178. Although traditionally the German kings had automatically inherited the royal crown of Arles since the time of Conrad II

Conrad II ( – 4 June 1039), also known as and , was the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire from 1027 until his death in 1039. The first of a succession of four Salian emperors, who reigned for one century until 1125, Conrad ruled the kingdoms ...

, Frederick felt the need to be crowned by the Archbishop of Arles, regardless of his laying claim to the title from 1152.

Frederick did not forgive Henry the Lion for refusing to come to his aid in 1176. By 1180, Henry had successfully established a powerful and contiguous state comprising Saxony, Bavaria, and substantial territories in the north and east of Germany. Taking advantage of the hostility of other German princes to Henry, Frederick had Henry tried in absentia by a court of bishops and princes in 1180, declared that imperial law overruled traditional German law, and had Henry stripped of his lands and declared an outlaw. He then invaded Saxony with an imperial army to force his cousin to surrender. Henry's allies deserted him, and he finally had to submit to Frederick at an Imperial Diet in

Frederick did not forgive Henry the Lion for refusing to come to his aid in 1176. By 1180, Henry had successfully established a powerful and contiguous state comprising Saxony, Bavaria, and substantial territories in the north and east of Germany. Taking advantage of the hostility of other German princes to Henry, Frederick had Henry tried in absentia by a court of bishops and princes in 1180, declared that imperial law overruled traditional German law, and had Henry stripped of his lands and declared an outlaw. He then invaded Saxony with an imperial army to force his cousin to surrender. Henry's allies deserted him, and he finally had to submit to Frederick at an Imperial Diet in Erfurt

Erfurt () is the capital and largest city in the Central German state of Thuringia. It is located in the wide valley of the Gera river (progression: ), in the southern part of the Thuringian Basin, north of the Thuringian Forest. It sits in ...

in November 1181. Henry spent three years in exile at the court of his father-in-law Henry II of England

Henry II (5 March 1133 – 6 July 1189), also known as Henry Curtmantle (french: link=no, Court-manteau), Henry FitzEmpress, or Henry Plantagenet, was King of England from 1154 until his death in 1189, and as such, was the first Angevin kin ...

in Normandy before being allowed back into Germany. He finished his days in Germany, as the much-diminished Duke of Brunswick. Frederick's desire for revenge was sated. Henry the Lion lived a relatively quiet life, sponsoring arts and architecture. Frederick's victory over Henry did not gain him as much in the German feudalistic system as it would have in the English feudalistic system. While in England the pledge of fealty went in a direct line from overlords to those under them, the Germans pledged oaths only to the direct overlord, so that in Henry's case, those below him in the feudal chain owed nothing to Frederick. Thus, despite the diminished stature of Henry the Lion, Frederick did not gain his allegiances.

Frederick was faced with the reality of disorder among the German states, where continuous civil wars were waged between pretenders and the ambitious who wanted the crown for themselves. Italian unity under German rule was more myth than truth. Despite proclamations of German hegemony, the pope was the most powerful force in Italy. When Frederick returned to Germany after his defeat in northern Italy, he was a bitter and exhausted man. The German princes, far from being subordinated to royal control, were intensifying their hold on wealth and power in Germany and entrenching their positions. There began to be a generalized social desire to "create greater Germany" by conquering the Slavs to the east.

Although the Italian city states had achieved a measure of independence from Frederick as a result of his failed fifth expedition into Italy, the emperor had not given up on his Italian dominions. In 1184, he held a massive celebration, the Diet of Pentecost, when his two eldest sons were knighted, and thousands of knights were invited from all over Germany. While payments upon the knighting of a son were part of the expectations of an overlord in England and France, only a "gift" was given in Germany for such an occasion. Frederick's monetary gain from this celebration is said to have been modest. Later in 1184, Frederick again moved into Italy, this time joining forces with the local rural nobility to reduce the power of the Tuscan cities. In 1186, he engineered the marriage of his son Henry to Constance of Sicily

Constance I ( it, Costanza; 2 November 1154 – 27 November 1198) was reigning Queen of Sicily from 1194–98, jointly with her spouse from 1194 to 1197, and with her infant son Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, in 1198, as the heiress of the ...

, heiress to the Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily ( la, Regnum Siciliae; it, Regno di Sicilia; scn, Regnu di Sicilia) was a state that existed in the south of the Italian Peninsula and for a time the region of Ifriqiya from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 un ...

, over the objections of Pope Urban III.

Pope Urban III died shortly after, and was succeeded by Pope Gregory VIII, who even as Papal Chancellor had pursued a more conciliatory line with the Emperor than previous popes and was more concerned with troubling reports from the Holy Land than with a power struggle with Barbarossa.

Third Crusade

Around 23 November 1187, Frederick received letters that had been sent to him from the rulers of the

Around 23 November 1187, Frederick received letters that had been sent to him from the rulers of the Crusader states

The Crusader States, also known as Outremer, were four Catholic realms in the Middle East that lasted from 1098 to 1291. These feudal polities were created by the Latin Catholic leaders of the First Crusade through conquest and political i ...

in the Near East urging him to come to their aid. Around 1 December, Cardinal Henry of Marcy

Henry of Marcy, or Henri de Marsiac, (c. 1136 –1 January 1189) was a Cistercian abbot, first of Hautecombe in Savoy (1160–1177), and then of Clairvaux, from 1177 until 1179. He was created Cardinal Bishop of Albano by Pope Alexander II ...

preached a crusade sermon before Frederick and a public assembly in Strasbourg

Strasbourg (, , ; german: Straßburg ; gsw, label= Bas Rhin Alsatian, Strossburi , gsw, label= Haut Rhin Alsatian, Strossburig ) is the prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est region of eastern France and the official seat of the ...

. Frederick expressed support for the crusade but declined to take the cross on the grounds of his ongoing conflict with Archbishop Philip of Cologne. He did, however, urge King Philip II of France