Frederick Augustus II of Poland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Augustus III ( pl, August III Sas, lt, Augustas III; 17 October 1696 5 October 1763) was King of Poland and

From his early years, Augustus was groomed to succeed as king of Poland-Lithuania; best tutors were hired from across the continent and the prince studied Polish, German, French and Latin. He was taught Russian, but was unable to speak it fluently,Staszewski, ''

From his early years, Augustus was groomed to succeed as king of Poland-Lithuania; best tutors were hired from across the continent and the prince studied Polish, German, French and Latin. He was taught Russian, but was unable to speak it fluently,Staszewski, '' On 26 September 1714, Augustus was warmly welcomed by

On 26 September 1714, Augustus was warmly welcomed by

On 20 August 1719, Augustus married

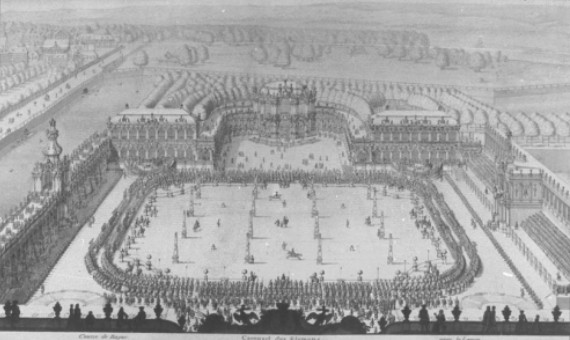

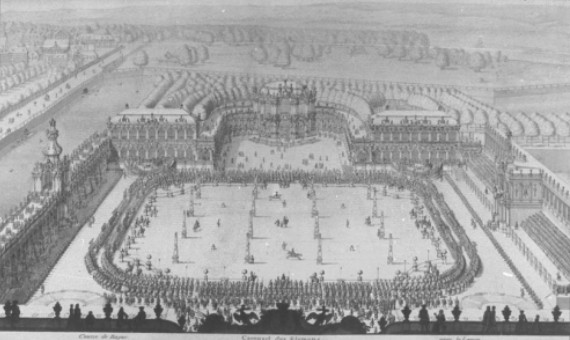

On 20 August 1719, Augustus married  The wedding celebration in Dresden was one of the most splendorous and expensive of the Baroque era in Europe. Over 800 guests were invited for a 2-week celebration. The main banquet was held in a chamber that was transformed into an artificial silver mine to astound the invitees. Apart from exotic dishes, over 500 deer were brought in from the

The wedding celebration in Dresden was one of the most splendorous and expensive of the Baroque era in Europe. Over 800 guests were invited for a 2-week celebration. The main banquet was held in a chamber that was transformed into an artificial silver mine to astound the invitees. Apart from exotic dishes, over 500 deer were brought in from the

page 32–33

Austria received a promise that as king, Augustus would both renounce any claim to the Austrian succession and continue respecting the

page 286–288

Augustus on his candidacy to the Polish throne was opposed by

Augustus on his candidacy to the Polish throne was opposed by

As King, Augustus was uninterested in the affairs of his Polish–Lithuanian dominion, focusing instead on hunting, the opera, and the collection of artwork at the

As King, Augustus was uninterested in the affairs of his Polish–Lithuanian dominion, focusing instead on hunting, the opera, and the collection of artwork at the

With the marriage to the Austrian princess Maria Josepha, Augustus was bound to accept the succession of her cousin, Maria Theresa, as Holy Roman Empress. Saxony mediated between the friendly French faction and the Habsburg faction of Maria Theresa. Between 1741 and 1742 Saxony was allied with France, but changed sides with the help of Austrian diplomats.

In the first days of December 1740, the Prussians assembled along the Oder river and on 16 December, Frederick invaded

With the marriage to the Austrian princess Maria Josepha, Augustus was bound to accept the succession of her cousin, Maria Theresa, as Holy Roman Empress. Saxony mediated between the friendly French faction and the Habsburg faction of Maria Theresa. Between 1741 and 1742 Saxony was allied with France, but changed sides with the help of Austrian diplomats.

In the first days of December 1740, the Prussians assembled along the Oder river and on 16 December, Frederick invaded  Saxony joined Austria in the

Saxony joined Austria in the

Augustus III was a great patron of the arts and architecture. During his reign the Baroque Catholic Church of the Royal Court in Dresden (present-day Dresden Cathedral) was built, in which he was later buried as one of the few Polish kings buried outside the

Augustus III was a great patron of the arts and architecture. During his reign the Baroque Catholic Church of the Royal Court in Dresden (present-day Dresden Cathedral) was built, in which he was later buried as one of the few Polish kings buried outside the

In 1732, a French priest named Gabriel Piotr Baudouin founded the first

In 1732, a French priest named Gabriel Piotr Baudouin founded the first

Grand Duke of Lithuania

The monarchy of Lithuania concerned the monarchical head of state of Kingdom of Lithuania, Lithuania, which was established as an Absolute monarchy, absolute and hereditary monarchy. Throughout Lithuania's history there were three Duke, ducal D ...

from 1733 until 1763, as well as Elector of Saxony

The Electorate of Saxony, also known as Electoral Saxony (German: or ), was a territory of the Holy Roman Empire from 1356–1806. It was centered around the cities of Dresden, Leipzig and Chemnitz.

In the Golden Bull of 1356, Emperor Charles ...

in the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

where he was known as Frederick Augustus II (german: link=no, Friedrich August II).

He was the only legitimate son of Augustus II the Strong

Augustus II; german: August der Starke; lt, Augustas II; in Saxony also known as Frederick Augustus I – Friedrich August I (12 May 16701 February 1733), most commonly known as Augustus the Strong, was Elector of Saxony from 1694 as well as K ...

, and converted to Roman Catholicism in 1712 to secure his candidacy for the Polish throne. In 1719 he married Maria Josepha, daughter of Joseph I, Holy Roman Emperor

, father = Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor

, mother = Eleonore Magdalene of Neuburg

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Vienna, Austria

, death_date =

, death_place = Vienna, Austria

, burial_place = Imperial Crypt, Vienna

, r ...

, and became Elector of Saxony following his father's death in 1733. Augustus was able to gain the support of Charles VI by agreeing to the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713

The Pragmatic Sanction ( la, Sanctio Pragmatica, german: Pragmatische Sanktion) was an edict issued by Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor, on 19 April 1713 to ensure that the Habsburg hereditary possessions, which included the Archduchy of Austria ...

and also gained recognition from Russian Empress Anna

Anna may refer to:

People Surname and given name

* Anna (name)

Mononym

* Anna the Prophetess, in the Gospel of Luke

* Anna (wife of Artabasdos) (fl. 715–773)

* Anna (daughter of Boris I) (9th–10th century)

* Anna (Anisia) (fl. 1218 to 12 ...

by supporting Russia's claim to the region of Courland. He was elected king of Poland by a small minority on 5 October 1733 and subsequently banished the former Polish king Stanisław I Stanislav and variants may refer to:

People

*Stanislav (given name), a Slavic given name with many spelling variations (Stanislaus, Stanislas, Stanisław, etc.)

Places

* Stanislav, a coastal village in Kherson, Ukraine

* Stanislaus County, Cal ...

. He was crowned in Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

on 17 January 1734.

Augustus was supportive of Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

against Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

in the War of the Austrian Succession (1742) and again in the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (175 ...

(1756), both of which resulted in Saxony being defeated and occupied by Prussia. In Poland, his rule was marked by the increasing influence of the Czartoryski

The House of Czartoryski (feminine form: Czartoryska, plural: Czartoryscy; lt, Čartoriskiai) is a Polish princely family of Lithuanian- Ruthenian origin, also known as the Familia. The family, which derived their kin from the Gediminids dyna ...

and Poniatowski

The House of Poniatowski (plural: ''Poniatowscy'') is a prominent Polish family that was part of the nobility of Poland. A member of this family, Stanisław Poniatowski, was elected as King of Poland and reigned from 1764 until his abdicatio ...

families, and by the intervention of Catherine the Great in Polish affairs. His rule deepened the social anarchy in Poland and increased the country's dependence on its neighbours, notably Prussia, Austria, and Russia. The Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

prevented him from installing his family on the Polish throne, supporting instead the aristocrat Stanisław August Poniatowski, the lover of Catherine the Great. Throughout his reign, Augustus was known to be more interested in ease and pleasure than in the affairs of state; this notable patron of the arts left the administration of Saxony and Poland to his chief adviser, Heinrich von Brühl

Heinrich, count von Brühl ( pl, Henryk Brühl, 13 August 170028 October 1763), was a Polish-Saxon statesman at the court of Saxony and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and a member of the powerful German von Brühl family. The incumbency of ...

, who in turn left Polish administration chiefly to the powerful Czartoryski family

The House of Czartoryski (feminine form: Czartoryska, plural: Czartoryscy; lt, Čartoriskiai) is a Polish princely family of Lithuanian- Ruthenian origin, also known as the Familia. The family, which derived their kin from the Gediminids dyna ...

.

Royal titles

Royal titles in la , Augustus tertius, Dei gratia rex Poloniae, magnus dux Lithuaniæ, Russiæ, Prussiæ, Masoviæ, Samogitiæ, Kijoviæ, Volhiniæ, Podoliæ, Podlachiæ, Livoniæ, Smolensciæ, Severiæ, Czerniechoviæque, nec non-hæreditarius dux Saxoniæ et princeps elector etc. English translation: ''August III, by the grace of God, King ofPoland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

, Grand Duke of Lithuania, Ruthenia, Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

, Masovia

Mazovia or Masovia ( pl, Mazowsze) is a historical region in mid-north-eastern Poland. It spans the North European Plain, roughly between Łódź and Białystok, with Warsaw being the unofficial capital and largest city. Throughout the centurie ...

, Samogitia

Samogitia or Žemaitija ( Samogitian: ''Žemaitėjė''; see below for alternative and historical names) is one of the five cultural regions of Lithuania and formerly one of the two core administrative divisions of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

, Kiev, Volhynia

Volhynia (also spelled Volynia) ( ; uk, Воли́нь, Volyn' pl, Wołyń, russian: Волы́нь, Volýnʹ, ), is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between south-eastern Poland, south-western Belarus, and western Ukraine. The ...

, Podolia

Podolia or Podilia ( uk, Поділля, Podillia, ; russian: Подолье, Podolye; ro, Podolia; pl, Podole; german: Podolien; be, Падолле, Padollie; lt, Podolė), is a historic region in Eastern Europe, located in the west-central ...

, Podlachia

Podlachia, or Podlasie, ( pl, Podlasie, , be, Падляшша, translit=Padliašša, uk, Підляшшя, translit=Pidliashshia) is a historical region in the north-eastern part of Poland. Between 1513 and 1795 it was a voivodeship with the c ...

, Livonia

Livonia ( liv, Līvõmō, et, Liivimaa, fi, Liivinmaa, German and Scandinavian languages: ', archaic German: ''Liefland'', nl, Lijfland, Latvian and lt, Livonija, pl, Inflanty, archaic English: ''Livland'', ''Liwlandia''; russian: Ли ...

, Smolensk

Smolensk ( rus, Смоленск, p=smɐˈlʲensk, a=smolensk_ru.ogg) is a city and the administrative center of Smolensk Oblast, Russia, located on the Dnieper River, west-southwest of Moscow. First mentioned in 863, it is one of the oldest ...

, Severia

Severia or Siveria ( orv, Сѣверія, russian: Северщина, translit=Severshchina, uk, Сіверія or , translit. ''Siveria'' or ''Sivershchyna'') is a historical region in present-day southwest Russia, northern Ukraine, eastern ...

, Chernihiv

Chernihiv ( uk, Черні́гів, , russian: Черни́гов, ; pl, Czernihów, ; la, Czernihovia), is a city and municipality in northern Ukraine, which serves as the administrative center of Chernihiv Oblast and Chernihiv Raion within ...

, and also hereditary Duke of Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a landlocked state of ...

and Prince-Elector

The prince-electors (german: Kurfürst pl. , cz, Kurfiřt, la, Princeps Elector), or electors for short, were the members of the electoral college that elected the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

From the 13th century onwards, the prin ...

, etc.''

Biography

Early life and education

Augustus was born 17 October 1696 inDresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label= Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth ...

, the only legitimate son of Augustus II the Strong

Augustus II; german: August der Starke; lt, Augustas II; in Saxony also known as Frederick Augustus I – Friedrich August I (12 May 16701 February 1733), most commonly known as Augustus the Strong, was Elector of Saxony from 1694 as well as K ...

, Prince-Elector

The prince-electors (german: Kurfürst pl. , cz, Kurfiřt, la, Princeps Elector), or electors for short, were the members of the electoral college that elected the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

From the 13th century onwards, the prin ...

of Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a landlocked state of ...

and ruler of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi- confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Poland and Lithuania ru ...

who belonged to the Albertine line of the House of Wettin

The House of Wettin () is a dynasty of German kings, prince-electors, dukes, and counts that once ruled territories in the present-day German states of Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia. The dynasty is one of the oldest in Europe, and its ori ...

. His mother was Christiane Eberhardine of Brandenburg-Bayreuth, daughter of Christian Ernst, Margrave of Brandenburg-Bayreuth

Christian Ernst of Brandenburg-Bayreuth (6 August 1644 in Bayreuth – 20 May 1712 in Erlangen) was a member of the House of Hohenzollern and Margrave of Brandenburg-Bayreuth.

He was the only son of Erdmann August, Hereditary Margrave (''E ...

. Unlike his father, Christiane remained a fervent Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

throughout her life and never set foot in Catholic Poland during her 30-year service as queen consort. Despite the pressure from Augustus II, she was never crowned at Wawel

The Wawel Royal Castle (; ''Zamek Królewski na Wawelu'') and the Wawel Hill on which it sits constitute the most historically and culturally significant site in Poland. A fortified residency on the Vistula River in Kraków, it was established o ...

in Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

and purely held a titular title of queen.Clarissa Campbell Orr: Queenship in Europe 1660–1815: The Role of the Consort. Cambridge University Press (2004) This move was viewed by the Polish nobility as a provocation and from the beginning the prince was treated with prejudice

Prejudice can be an affective feeling towards a person based on their perceived group membership. The word is often used to refer to a preconceived (usually unfavourable) evaluation or classification of another person based on that person's per ...

in Poland.

From his early years, Augustus was groomed to succeed as king of Poland-Lithuania; best tutors were hired from across the continent and the prince studied Polish, German, French and Latin. He was taught Russian, but was unable to speak it fluently,Staszewski, ''

From his early years, Augustus was groomed to succeed as king of Poland-Lithuania; best tutors were hired from across the continent and the prince studied Polish, German, French and Latin. He was taught Russian, but was unable to speak it fluently,Staszewski, ''Op. cit.

''Op. cit.'' is an abbreviation of the Latin phrase ' or ''opere citato'', meaning "the work cited" or ''in the cited work'', respectively.

Overview

The abbreviation is used in an endnote or footnote to refer the reader to a cited work, standing ...

'', p. 28 as well as exact sciences

The exact sciences, sometimes called the exact mathematical sciences, are those sciences "which admit of absolute precision in their results"; especially the mathematical sciences. Examples of the exact sciences are mathematics, optics, astron ...

including mathematics, chemistry and geography. He also practiced equestrianism in his youth. While his father spent time in Poland, the young Augustus was left in the care of his grandmother, Princess Anna Sophie of Denmark

Princess Anna Sophie of Denmark and Norway (1 September 1647 – 1 July 1717) was the eldest daughter of King Frederick III of Denmark and Sophie Amalie of Brunswick-Lüneburg, and Electress of Saxony from 1680 to 1691 as the wife of John Geor ...

, who initially raised him Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

. This was particularly unfavourable for the Poles, who wouldn't accept or tolerate a Protestant monarch. As a consequence, troubled Augustus II organized a tour of Catholic countries in Europe for his son which he hoped would bring him closer to Catholicism and break the bond between him and his controlling grandmother. In Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isla ...

, the Polish entourage thwarted a kidnapping attempt organized by British agents of Queen Anne in order to prevent him from converting. He also witnessed the coronation of Charles VI in 1711 after the death of his brother and predecessor, Joseph I Joseph I or Josef I may refer to:

*Joseph I of Constantinople, Ecumenical Patriarch in 1266–1275 and 1282–1283

* Joseph I, Holy Roman Emperor (1678–1711)

*Joseph I (Chaldean Patriarch) (reigned 1681–1696)

*Joseph I of Portugal (1750–1777) ...

.

Augustus eventually converted to Roman Catholicism in November 1712 while extensively touring Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, and its cultural and religious heritage. He was then under the supervision of the Jesuits

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

, who certainly contributed to the cause. The public announcement of conversion in 1717 triggered discontent among the Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

Saxon aristocracy... Faced with a hereditary Catholic succession for Saxony, Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

and Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

attempted to oust Saxony from the directorship of the Protestant body in the Reichstag of the Holy Roman Empire, but Saxony managed to retain the directorship.

On 26 September 1714, Augustus was warmly welcomed by

On 26 September 1714, Augustus was warmly welcomed by Louis XIV of France

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of ...

at Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, ...

. Louis rejoiced when he heard that Augustus converted to Catholicism and permitted him to stay at the royal court and in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

. The young prince participated in balls, masquerades and private parties that were hosted by the Sun King himself. During this time, Augustus improved his knowledge of the French language and learnt how to approach politics and diplomacy. In June 1715, he departed Versailles and travelled across France, visiting Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( , ; Gascon oc, Bordèu ; eu, Bordele; it, Bordò; es, Burdeos) is a port city on the river Garonne in the Gironde department, Southwestern France. It is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the prefect ...

, Moissac

Moissac () is a commune in the Tarn-et-Garonne department in the Occitanie region in southern France. The town is situated at the confluence of the rivers Garonne and Tarn at the Canal de Garonne. Route nationale N113 was constructed through ...

, Toulouse

Toulouse ( , ; oc, Tolosa ) is the prefecture of the French department of Haute-Garonne and of the larger region of Occitania. The city is on the banks of the River Garonne, from the Mediterranean Sea, from the Atlantic Ocean and from Pa ...

, Carcassonne

Carcassonne (, also , , ; ; la, Carcaso) is a French fortified city in the department of Aude, in the region of Occitanie. It is the prefecture of the department.

Inhabited since the Neolithic, Carcassonne is located in the plain of the Au ...

, Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Fra ...

and Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan language, Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, third-largest city and Urban area (France), second-largest metropolitan area of F ...

. Apart from sightseeing, the purpose of this trip was to understand how cities and villages function. Being brought up in great wealth, Augustus was not entirely aware of how extensive poverty and poor living conditions can be in the countryside.

Marriage and wedding

On 20 August 1719, Augustus married

On 20 August 1719, Augustus married Maria Josepha of Austria

Maria Josepha of Austria (Maria Josepha Benedikta Antonia Theresia Xaveria Philippine, pl, Maria Józefa; 8 December 1699 – 17 November 1757) was the Queen of Poland and Electress of Saxony by marriage to Augustus III. From 1711 to 1717, sh ...

in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

. She was the daughter of the deceased Emperor Joseph I and niece of Charles VI of the Holy Roman Empire, whose coronation young Augustus attended. This marriage wasn't coincidental; Augustus II the Strong orchestrated it to maintain the might of the Saxons within the Holy Roman Empire. The alliance with Catholic Charles would prove fruitful in case of hostile or armed opposition from the Protestant states within the Empire. Ten days earlier, on 10 August 1719, Maria Josepha was forced to renounce her claim to the throne of Austria in favour of her uncle's daughter, Maria Theresa. In accordance with the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713

The Pragmatic Sanction ( la, Sanctio Pragmatica, german: Pragmatische Sanktion) was an edict issued by Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor, on 19 April 1713 to ensure that the Habsburg hereditary possessions, which included the Archduchy of Austria ...

issued by Charles, a female heir or the eldest daughter would be permitted to inherit the throne of Austria. Augustus II also hoped to place Saxony in a better position should there arise a war of succession to the Austrian territories.

Białowieża Forest

Białowieża Forest; lt, Baltvyžių giria; pl, Puszcza Białowieska ; russian: Беловежская пуща, Belovezhskaya Pushcha is a forest on the border between Belarus and Poland. It is one of the last and largest remaining pa ...

for the feast. Approximately 4 million thalers were spent for this occasion.

Succession

Augustus II died suddenly on 1 February 1733, following aSejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland ( Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of ...

(Polish parliament) session in Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

. Augustus III inherited the Saxon electorate without any problems, but his election to the Polish throne was much more complicated. Shortly before the ailing king died, Prussia, Austria and Russia signed a pact known as the Treaty of the Three Black Eagles

The Treaty of the Three Black Eagles, or Treaty of Berlin, was a secret treaty signed in September and December 1732 between the Austrian Empire, the Russian Empire and Prussia.

It concerned the joint policy of the three powers regarding to the ...

, which would prevent Augustus III and Stanisław Leszczyński from inheriting the Polish throne. The royal elections in Poland and the elective monarchy, in general, weakened the country and allowed other powers to meddle in Polish affairs. The neighbouring countries that signed the treaty preferred a neutral monarch like Infante Manuel, Count of Ourém

Infante Manuel, Count of Ourém, KGF (; ''Manuel José Francisco António Caetano Estêvão Bartolomeu''; ( Lisbon, 3 August 1697 - Quinta de Belas, 3 August 1766) was a Portuguese ''infante'' (prince), seventh child of Peter II, King of Portug ...

, brother of John V of Portugal

Dom John V ( pt, João Francisco António José Bento Bernardo; 22 October 1689 – 31 July 1750), known as the Magnanimous (''o Magnânimo'') and the Portuguese Sun King (''o Rei-Sol Português''), was King of Portugal from 9 December 17 ...

, or any living relative of the Piast dynasty. The agreement had provisions for all three powers to agree that it was in their best interest that their common neighbour, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, did not undertake any reforms that might strengthen it and trigger expansionism. The new king would also have to maintain friendly relations with these countries.

The treaty quickly became ineffective as Prussia began to support Leszczyński and allowed him safe passage from France to Poland through German lands. As a result, Austria and Russia signed on 19 August 1733 the Löwenwolde's Treaty, named after Karl Gustav von Löwenwolde

Count Karl Gustav von Löwenwolde (17th century - 30 April 1735 Räpina) ( pl, Karl Gustaw von Loewenwolde, russian: Левенвольде, Карл Густав, lv, Kārlis Gustavs Lēvenvolde) was a Russian diplomat and military commander of ...

. The terms of Löwenwolde's Treaty were direct; Russia opted for a '' quid pro quo'' – they would provide troops to ensure Augustus III is elected king and in turn, Augustus would recognise Anna Ivanovna

Anna Ioannovna (russian: Анна Иоанновна; ), also russified as Anna Ivanovna and sometimes anglicized as Anne, served as regent of the duchy of Courland from 1711 until 1730 and then ruled as Empress of Russia from 1730 to 1740. Much ...

as Empress of Russia

The emperor or empress of all the Russias or All Russia, ''Imperator Vserossiyskiy'', ''Imperatritsa Vserossiyskaya'' (often titled Tsar or Tsarina/Tsaritsa) was the monarch of the Russian Empire.

The title originated in connection with Russia' ...

, thus relinquishing Polish claims to Livonia

Livonia ( liv, Līvõmō, et, Liivimaa, fi, Liivinmaa, German and Scandinavian languages: ', archaic German: ''Liefland'', nl, Lijfland, Latvian and lt, Livonija, pl, Inflanty, archaic English: ''Livland'', ''Liwlandia''; russian: Ли ...

and Courland.Ragsdale, Hugh (1993) ''Imperial Russian foreign policy'' Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, Englandpage 32–33

Austria received a promise that as king, Augustus would both renounce any claim to the Austrian succession and continue respecting the

Pragmatic Sanction of 1713

The Pragmatic Sanction ( la, Sanctio Pragmatica, german: Pragmatische Sanktion) was an edict issued by Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor, on 19 April 1713 to ensure that the Habsburg hereditary possessions, which included the Archduchy of Austria ...

.Corwin, Edward Henry Lewinski (1917) ''The political History of Poland'' Polish Book Importing Company, New Yorkpage 286–288

War of the Polish Succession

Augustus on his candidacy to the Polish throne was opposed by

Augustus on his candidacy to the Polish throne was opposed by Stanisław I Leszczyński Stanislav and variants may refer to:

People

*Stanislav (given name), a Slavic given name with many spelling variations (Stanislaus, Stanislas, Stanisław, etc.)

Places

* Stanislav, a coastal village in Kherson, Ukraine

* Stanislaus County, Cali ...

(Stanislaus I), who had usurped the throne with Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

support during the Great Northern War

The Great Northern War (1700–1721) was a conflict in which a coalition led by the Tsardom of Russia successfully contested the supremacy of the Swedish Empire in Northern, Central and Eastern Europe. The initial leaders of the anti-Swed ...

. Reigning from 1706 until 1709, Stanisław was overthrown after the Swedish defeat at Poltava. Returning from exile in 1733 with the support of Louis XV of France

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reache ...

and Spain, Stanisław sparked the War of the Polish Succession

The War of the Polish Succession ( pl, Wojna o sukcesję polską; 1733–35) was a major European conflict sparked by a Polish civil war over the succession to Augustus II of Poland, which the other European powers widened in pursuit of thei ...

.

Throughout the spring and summer of 1733, France began mobilizing and stationing forces along its northern and eastern borders, while Austria massed troops on the Polish frontier, reducing garrisons in the Duchy of Milan for the purpose. Prince Eugene of Savoy

Prince Eugene Francis of Savoy–Carignano, (18 October 1663 – 21 April 1736) better known as Prince Eugene, was a field marshal in the army of the Holy Roman Empire and of the Austrian Habsburg dynasty during the 17th and 18th centuries. He ...

recommended to the emperor a more warlike posture against its longtime rival, France. He suggested that the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

valley and northern Italy should be strengthened with more troops, however only minimal steps were taken to improve imperial defences on the Rhine. In July 1733, Augustus agreed to Austria's and Russia's terms per Löwenwolde's Treaty. During the election sejm in August, Russian troops counting 30,000 men under the command of Peter Lacy

Peter Graf von Lacy (russian: link=no, Пётр Петро́вич Ла́сси, tr. ; en, Pierce Edmond de Lacy; ga, Peadar (Piarais Éamonn) de Lása; 26 September 1678 – 30 April 1751) was an Irish-born soldier who later served in the ...

entered Poland to secure Augustus' succession. The election was ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legally ...

'' won by Stanisław, with 12,000 votes. Augustus received 3,000, however, he had the support of Poland's influential, wealthiest and most corrupt magnates, such as Michael Servacy Wiśniowiecki.

The Franco-Spanish coalition declared war on Austria and Saxony on 10 October. The Italian states of Savoy-Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label=Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after ...

and Parma

Parma (; egl, Pärma, ) is a city in the northern Italian region of Emilia-Romagna known for its architecture, music, art, prosciutto (ham), cheese and surrounding countryside. With a population of 198,292 inhabitants, Parma is the second mos ...

also joined the struggle against Austrian rule in northern Italy. Most of the battles took place outside of Poland and the main focus of the war was personal interests and demonstration of superiority. The Russian-Saxon forces chased Stanisław until he was besieged at Gdańsk (Danzig) on 22 February 1734. In June, when the garrisons at Gdańsk surrendered, Stanisław fled to Königsberg

Königsberg (, ) was the historic Prussian city that is now Kaliningrad, Russia. Königsberg was founded in 1255 on the site of the ancient Old Prussian settlement ''Twangste'' by the Teutonic Knights during the Northern Crusades, and was name ...

and then back to France. The Pacification Sejm in 1736 ''de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with ''de jure'' ("by la ...

'' confirmed Augustus III as King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania.

To this day, the aphorism and phrase ''od Sasa do Lasa'' (lit. from the Saxon to Leszczyński) exists in the Polish language and is used when describing two completely opposite things in everyday life.

Reign and diplomacy

Poland

As King, Augustus was uninterested in the affairs of his Polish–Lithuanian dominion, focusing instead on hunting, the opera, and the collection of artwork at the

As King, Augustus was uninterested in the affairs of his Polish–Lithuanian dominion, focusing instead on hunting, the opera, and the collection of artwork at the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister

The Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (, ''Old Masters Gallery'') in Dresden, Germany, displays around 750 paintings from the 15th to the 18th centuries. It includes major Italian Renaissance works as well as Dutch and Flemish paintings. Outstand ...

. He spent less than three years of his thirty-year reign in Poland, where political feuding between the House of Czartoryski

The House of Czartoryski (feminine form: Czartoryska, plural: Czartoryscy; lt, Čartoriskiai) is a Polish princely family of Lithuanian- Ruthenian origin, also known as the Familia. The family, which derived their kin from the Gediminids dyna ...

and the Potocki paralyzed the Sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland ( Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of ...

( Liberum veto), fostering internal political anarchy and weakening the Commonwealth. Augustus delegated most of his powers and responsibilities in the Commonwealth to Heinrich von Brühl

Heinrich, count von Brühl ( pl, Henryk Brühl, 13 August 170028 October 1763), was a Polish-Saxon statesman at the court of Saxony and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and a member of the powerful German von Brühl family. The incumbency of ...

, who served in effect as the viceroy of Poland. Brühl in turn left the politics in Poland to the most powerful magnates and nobles, which resulted in widespread corruption. Under Augustus, Poland was not involved in any major conflicts which further lessened its position in Europe and allowed the neighbouring countries to take advantage of the disorder. Any opposition was violently crushed by Brühl, who used either Saxon or Russian forces that permanently stationed in the country.

Brühl was a skillful diplomat and strategist; Augustus could only be reached through him if an important political feud arose. He was also the head of the Saxon court in Dresden and was fond of collectibles, such as gadgets, jewellery and Meissen porcelain

Meissen porcelain or Meissen china was the first European hard-paste porcelain. Early experiments were done in 1708 by Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus. After his death that October, Johann Friedrich Böttger continued von Tschirnhaus's work an ...

, the most famous being the Swan Service composed of 2,200 individual pieces made between 1737 and 1741. It has been described as possibly "the finest table service ever produced" and part of it are exhibited at the National Museum in Warsaw

The National Museum in Warsaw ( pl, Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie), popularly abbreviated as MNW, is a national museum in Warsaw, one of the largest museums in Poland and the largest in the capital. It comprises a rich collection of ancient art ( Eg ...

. He also owned the largest collections of watches, vests, wigs and hats in Europe, though this cannot be accurately assessed. Brühl was depicted by his rivals as a nouveau-riche materialist, who used his wealth to gain support. His lavish spending was immortalized by Augustus' reported question to the viceroy "Brühl, do I have money?"

By 1748 Augustus III completed extending the Saxon Palace

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

in Warsaw and made significant contributions in remodelling the Royal Castle. In 1750, von Brühl purchased a residence adjacent to the larger Saxon Palace and transformed it into a rococo

Rococo (, also ), less commonly Roccoco or Late Baroque, is an exceptionally ornamental and theatrical style of architecture, art and decoration which combines asymmetry, scrolling curves, gilding, white and pastel colours, sculpted moulding, ...

masterpiece, which later became known as the Brühl Palace. Both buildings were completely destroyed by the Nazis during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

.

War of the Austrian Succession

With the marriage to the Austrian princess Maria Josepha, Augustus was bound to accept the succession of her cousin, Maria Theresa, as Holy Roman Empress. Saxony mediated between the friendly French faction and the Habsburg faction of Maria Theresa. Between 1741 and 1742 Saxony was allied with France, but changed sides with the help of Austrian diplomats.

In the first days of December 1740, the Prussians assembled along the Oder river and on 16 December, Frederick invaded

With the marriage to the Austrian princess Maria Josepha, Augustus was bound to accept the succession of her cousin, Maria Theresa, as Holy Roman Empress. Saxony mediated between the friendly French faction and the Habsburg faction of Maria Theresa. Between 1741 and 1742 Saxony was allied with France, but changed sides with the help of Austrian diplomats.

In the first days of December 1740, the Prussians assembled along the Oder river and on 16 December, Frederick invaded Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

without a formal declaration of war. The Austrian troops which then stationed in Silesia were poorly supplied and outnumbered as the Habsburgs concentrated their supreme force on Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the ...

and Italy. They held onto the fortresses of Glogau, Breslau, and Brieg, but abandoned the rest of the region and withdrew into Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The m ...

. This campaign gave Prussia control of most of the richest provinces in the Habsburg Empire

The Habsburg monarchy (german: Habsburgermonarchie, ), also known as the Danubian monarchy (german: Donaumonarchie, ), or Habsburg Empire (german: Habsburgerreich, ), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities ...

, with the commercial centre of Breslau as well as mining, weaving and dyeing industries. Silesia was also rich in natural resources such as coal, chalk

Chalk is a soft, white, porous, sedimentary carbonate rock. It is a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite and originally formed deep under the sea by the compression of microscopic plankton that had settled to the sea floor. Ch ...

, copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkis ...

and gold.

Saxony joined Austria in the

Saxony joined Austria in the Second Silesian War

The Second Silesian War (german: Zweiter Schlesischer Krieg, links=no) was a war between Prussia and Austria that lasted from 1744 to 1745 and confirmed Prussia's control of the region of Silesia (now in south-western Poland). The war was fough ...

, which erupted after Prussia proclaimed to keep Charles VII as Holy Roman Emperor and invaded Bohemia on 15 August 1744. The true cause behind the invasion was Frederick's personal expansionist

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military empire-building or colonialism.

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established polity (who of ...

ideas and goals. On 8 January 1745, the Treaty of Warsaw united Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

, the Habsburg Monarchy, the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

and Saxony into what became known as the "Quadruple Alliance", which was aimed at securing the Austrian throne for Maria Theresa. Soon-after Charles VII died of gout

Gout ( ) is a form of inflammatory arthritis characterized by recurrent attacks of a red, tender, hot and swollen joint, caused by deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals. Pain typically comes on rapidly, reaching maximal intens ...

in Munich, which weakened the Prussians. However, Prussia still maintained military superiority; the successful battles of Hennersdorf and Kesselsdorf opened the way to Dresden, which Frederick occupied on 18 December. The Treaty of Dresden

The Treaty of Dresden was signed on 25 December 1745 at the Saxon capital of Dresden between Austria, Saxony and Prussia, ending the Second Silesian War.

In the 1742 Treaty of Breslau, Maria Theresa of Austria, struggling for the succession aft ...

was eventually completed on Christmas Day (25 December) and Saxony was obliged to pay one million rixdollar Rixdollar is the English term for silver coinage used throughout the European continent (german: Reichsthaler, nl, rijksdaalder, da, rigsdaler, sv, riksdaler).

The same term was also used of currency in Cape Colony and Ceylon. However, the R ...

s in reparations to the Prussian state. The treaty ended the Second Silesian War with a '' status quo ante bellum''.

Maria Theresa was finally recognized as Empress with the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748, which proved a Pyrrhic victory for Augustus III, however, the conflict nearly bankrupted Saxony. Meanwhile, the affairs in Poland remained highly neglected.

Seven Years' War

The Electorate of Saxony was involved in theSeven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (175 ...

from 1756 to 1763. The Saxons were allied with Austria and Russia against Frederick the Great

Frederick II (german: Friedrich II.; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was King in Prussia from 1740 until 1772, and King of Prussia from 1772 until his death in 1786. His most significant accomplishments include his military successes in the S ...

of Prussia, who saw Saxony as another potential field for expansion. Saxony was then merely a buffer zone between Prussia and Austrian Bohemia as well as Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

, which Frederick attempted to annex in their entirety. Moreover, Saxony and Poland were separated by a strip of land in Silesia and Lusatia

Lusatia (german: Lausitz, pl, Łużyce, hsb, Łužica, dsb, Łužyca, cs, Lužice, la, Lusatia, rarely also referred to as Sorbia) is a historical region in Central Europe, split between Germany and Poland. Lusatia stretches from the Bóbr ...

which made the movement of troops even more difficult. Frederick's plans also entailed annexing Duchy of Hanover

A duchy, also called a dukedom, is a medieval country, territory, fief, or domain ruled by a duke or duchess, a ruler hierarchically second to the king or queen in Western European tradition.

There once existed an important difference between " ...

, but joining France would trigger an Austro-Russian attack and occupation. On 29 August 1756, the Prussian army preemptively invaded Saxony, beginning the Third Silesian War

The Third Silesian War () was a war between Prussia and Austria (together with its allies) that lasted from 1756 to 1763 and confirmed Prussia's control of the region of Silesia (now in south-western Poland). The war was fought mainly in Silesi ...

, a theatre of the Seven Years' War. Saxony was bled dry and exploited at the maximum extent to support Prussia's war effort. The Treaty of Hubertusburg

The Treaty of Hubertusburg (german: Frieden von Hubertusburg) was signed on 15 February 1763 at Hubertusburg Castle by Prussia, Austria and Saxony to end the Third Silesian War. Together with the Treaty of Paris, signed five days earlier, it mark ...

signed on 15 February 1763 ended the conflict with Frederick's victory and Saxony renounced its claim to Silesia.

Death

In April 1763, Augustus returned ill and frail from Poland to Dresden with his closest advisors, leaving Primate Władysław Aleksander Łubieński behind to take care of the affairs in the Commonwealth. He died suddenly on 5 October 1763 in Dresden fromapoplexy

Apoplexy () is rupture of an internal organ and the accompanying symptoms. The term formerly referred to what is now called a stroke. Nowadays, health care professionals do not use the term, but instead specify the anatomic location of the bleedi ...

(stroke). Unlike his father who rests at Wawel

The Wawel Royal Castle (; ''Zamek Królewski na Wawelu'') and the Wawel Hill on which it sits constitute the most historically and culturally significant site in Poland. A fortified residency on the Vistula River in Kraków, it was established o ...

in Kraków, Augustus III was buried at Dresden Cathedral

Dresden Cathedral, or the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity, Dresden, previously the Catholic Church of the Royal Court of Saxony, called in German Katholische Hofkirche and since 1980 also known as Kathedrale Sanctissimae Trinitatis, is the Catholi ...

and remains one of the few Polish monarchs who were buried outside of Poland.

Augustus's eldest surviving son, Frederick Christian of Saxony, succeeded his father as Elector but died two and a half months later.

In the Commonwealth, on September 7, 1764, with the small participation of the szlachta initiated by the Czartoryski's and the strong support of Russia, Stanisław August Poniatowski was elected king of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania. Reigning under the name Stanisław II Augustus, Poniatowski was the son of the elder Stanisław Poniatowski, a powerful Polish noble and a onetime agent of Stanisław I; in youth he was a lover of Catherine II of Russia and as such enjoyed strong support from that Empress's court.

Legacy

Patron of arts

Augustus III was a great patron of the arts and architecture. During his reign the Baroque Catholic Church of the Royal Court in Dresden (present-day Dresden Cathedral) was built, in which he was later buried as one of the few Polish kings buried outside the

Augustus III was a great patron of the arts and architecture. During his reign the Baroque Catholic Church of the Royal Court in Dresden (present-day Dresden Cathedral) was built, in which he was later buried as one of the few Polish kings buried outside the Wawel Cathedral

The Wawel Cathedral ( pl, Katedra Wawelska), formally titled the Royal Archcathedral Basilica of Saints Stanislaus and Wenceslaus, is a Roman Catholic cathedral situated on Wawel Hill in Kraków, Poland. Nearly 1000 years old, it is part of the ...

in Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

. He greatly expanded the Dresden art gallery, to the extent that in 1747 it was placed in a new location at the present-day Johanneum, where it remained until 1855 when it was moved to the newly built Semper Gallery

The Semper Gallery or Semper Building (German: Sempergalerie or Semperbau) in Dresden, Germany, was designed by the architect Gottfried Semper and constructed from 1847 until 1854.

The long-stretched building in Neoclassical style closes the Zwi ...

. In 1748 he founded the Opera House (''Operalnia'') in Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

and the ''Collegium medico-chirurgicum'', the first medical school in Dresden. During his reign, the extension of the Saxon Palace

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

in Warsaw, begun by his father Augustus II, was completed, and the reconstruction of the eastern façade of the Royal Castle was ordered, thus creating the so-called Saxon Facade, an iconic part of the Vistula

The Vistula (; pl, Wisła, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in ...

panorama of the Warsaw Old Town

Warsaw Old Town ( pl, Stare Miasto, italic=yes and colloquially as ''Starówka'') is the oldest part of Warsaw, the capital city of Poland. It is bounded by the ''Wybrzeże Gdańskie'' (Gdańsk Boulevards), along with the bank of the Vistula river, ...

.

In 1733, the composer Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the '' Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suites; keyboard wo ...

dedicated the Kyrie–Gloria Mass in B minor, (early version), to Augustus in honor of his succession to the Saxon electorate, with the hope of appointment as Court Composer, a title Bach received three years later. Bach's title of ''Koeniglicher Pohlnischer Hoff Compositeur'' (''Royal Polish Court Composer'', and court composer to the Elector of Saxony) is engraved on the title page of Bach's famous Goldberg Variations

The ''Goldberg Variations'', BWV 988, is a musical composition for keyboard by Johann Sebastian Bach, consisting of an aria and a set of 30 variations. First published in 1741, it is named after Johann Gottlieb Goldberg, who may also hav ...

. Augustus III was also the patron of composer Johann Adolph Hasse

Johann Adolph Hasse (baptised 25 March 1699 – 16 December 1783) was an 18th-century German composer, singer and teacher of music. Immensely popular in his time, Hasse was best known for his prolific operatic output, though he also composed a co ...

, who was granted the title of the Royal-Polish and Electoral-Saxon Kapellmeister by his father, Augustus II, in 1731, and thanks to Augustus III the same title was obtained in 1716 by composer Johann David Heinichen.

Personal life and criticism

In 1732, a French priest named Gabriel Piotr Baudouin founded the first

In 1732, a French priest named Gabriel Piotr Baudouin founded the first orphanage

An orphanage is a residential institution, total institution or group home, devoted to the care of orphans and children who, for various reasons, cannot be cared for by their biological families. The parents may be deceased, absent, or ab ...

in Poland, situated in Warsaw's Old Town. The facility was later moved to the nearby Warecki Square (now Warsaw Uprising Square

Warsaw Uprising Square (Polish: ''Plac Powstańców Warszawy''), still popularly known by its former name Napoleon Square (Polish: ''Plac Napoleona''), is a square in the central Warsaw district of Śródmieście.

Located at the junction of '' ...

), and in 1758 Augustus III decreed that the new institution be called ''Szpital Generalny Dzieciątka Jezus'' (The General Hospital of Infant Jesus). The newly established hospital expanded its operations into treating not only orphans but also the sick and the poor. Augustus remained a charitable man throughout his life and donated to the hospital. His successor, Stanisław Augustus, also contributed to the cause.

Despite his charitable manner, Augustus was viewed in Poland as an impotent monarch, obese, plump, ugly and lazy sybarite with no interest in the affairs of the state. Such harsh critique and opinion continues to this day. On the other hand, historian Jacek Staszewski was able to find a description of Augustus' character in the Dresden archives in the late 1980s; he was considered an honest and affectionate man, who was widely respected during his reign by both the Saxons and the Poles. In his personal life, Augustus was a devoted husband to Maria Josepha, with whom he had sixteen children. Unlike his father who was a notorious womanizer, he was never unfaithful and enjoyed spending time with his spouse, uncommon among the royalty in those days. He also favoured hunting.

Depictions

Augustus III was portrayed byErnst Dernburg

Ernst Dernburg (born Erich Wilhelm Franz Hermann Calow; 4 April 1887 – 23 September 1969) was a German stage and film actor.Giesen p.198

Selected filmography

*'' The Sacrifice'' (1918)

* '' The Living Dead'' (1919)

* '' The Marquise of Armiani ...

in the 1941 film '' Friedemann Bach''.

Issue

On 20 August 1719, Augustus marriedArchduchess Maria Josepha of Austria

Archduchess Maria Josepha of Austria (Maria Josepha Gabriella Johanna Antonia Anna; 19 March 1751 – 15 October 1767) was the duodenary daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Francis I and Holy Roman Empress Maria Theresa. She died of smallpox at th ...

, the eldest child of Joseph I, the Holy Roman Emperor. They had sixteen children, but only fourteen or fifteen are recognized by historians:

* Frederick Augustus Franz Xavier (born Dresden, 18 November 1720 – died Dresden, 22 January 1721)

* Joseph Augustus Wilhelm Frederick Franz Xavier Johann Nepomuk (born Pillnitz, 24 October 1721 – died Dresden, 14 March 1728)

* Frederick Christian Leopold Johann Georg Franz Xavier (born Dresden, 5 September 1722 – died Dresden, 17 December 1763), successor to his father as Elector of Saxony

* Unknown stillborn daughter (Dresden, 23 June 1723)

* Maria Amalia Christina Franziska Xaveria Flora Walburga (born Dresden, 24 November 1724 – died Buen Retiro, 27 September 1760); married on 19 June 1738 to Charles VII, King of Naples, later King Charles III of Spain

* Maria Margaretha Franziska Xaveria (born Dresden, 13 September 1727 – died Dresden, 1 February 1734), died in childhood.

* Maria Anna Sophie Sabina Angela Franziska Xaveria (born Dresden, 29 August 1728 – died Munich, 17 February 1797); married on 9 August 1747 to Maximilian III Joseph, Elector of Bavaria

Maximilian III Joseph, "the much beloved", (28 March 1727 – 30 December 1777) was a Prince-elector of the Holy Roman Empire and Duke of Bavaria from 1745 to 1777.

Biography

Born in Munich, Maximilian was the eldest son of Holy Roman Empero ...

* Unknown child (1729–1730)

* Franz Xavier Albert August Ludwig Benno (born Dresden, 25 August 1730 – died Dresden, 21 June 1806), Regent of Saxony (1763–1768)

* Maria Josepha Karolina Eleonore Franziska Xaveria (born Dresden, 4 November 1731 – died Versailles, 13 March 1767); married on 9 February 1747 to Louis, Dauphin of France (1729–1765)

, house = Bourbon

, spouse =

, issue = Marie Thérèse, Madame Royale Princess Marie Zéphyrine Prince Louis, Duke of BurgundyLouis XVI of FranceLouis XVIII of France Charles X of France Marie Clothilde, Queen of Sardinia ...

, son of Louis XV of France

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reache ...

(she was the mother of Kings Louis XVI

Louis XVI (''Louis-Auguste''; ; 23 August 175421 January 1793) was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. He was referred to as ''Citizen Louis Capet'' during the four months just before he was ...

, Louis XVIII

Louis XVIII (Louis Stanislas Xavier; 17 November 1755 – 16 September 1824), known as the Desired (), was King of France from 1814 to 1824, except for a brief interruption during the Hundred Days in 1815. He spent twenty-three years in ...

and Charles X

Charles X (born Charles Philippe, Count of Artois; 9 October 1757 – 6 November 1836) was King of France from 16 September 1824 until 2 August 1830. An uncle of the uncrowned Louis XVII and younger brother to reigning kings Louis XVI and Lou ...

) of France

* Karl Christian Joseph Ignaz Eugen Franz Xavier (born Dresden, 13 July 1733 – died Dresden, 16 June 1796), Duke of Courland and Zemgale

Semigallia, also spelt Semigalia, ( lv, Zemgale; german: Semgallen; lt, Žiemgala; pl, Semigalia; liv, Zemgāl) is one of the Historical Latvian Lands located in the south of the Daugava river and the north of the Saule region of Samogitia. ...

(1758–1763)

* Maria Christina Anna Teresia Salomea Eulalia Franziska Xaveria (born Warsaw, 12 February 1735 – died Brumath, 19 November 1782), Princess-Abbess

A prince-abbot (german: Fürstabt) is a title for a clergy, cleric who is a Prince of the Church (like a Prince-bishop), in the sense of an ''ex officio'' temporal lord of a feudalism, feudal entity, usually a Imperial State, State of the Holy R ...

of Remiremont

Remiremont (; german: Romberg or ) is a town and commune in the Vosges department, northeastern France, situated in southern Grand Est. The town has been an abbatial centre since the 7th century, is an economic crossroads of the Moselle and Mos ...

* Maria Elisabeth Apollonia Casimira Francisca Xaveria (born Warsaw, 9 February 1736 – died Dresden, 24 December 1818), died unmarried.

* Albert Kasimir August Ignaz Pius Franz Xavier (born Moritzburg, near Dresden, 11 July 1738 – died Vienna, 10 February 1822), Duke of Teschen and Governor of the Austrian Netherlands (1781–1793)

* Clemens Wenceslaus August Hubertus Franz Xavier (born Schloss Hubertusburg, Wermsdorf, 28 September 1739 – died Marktoberdorf, Allgäu, 27 July 1812), Archbishop of Trier

The Diocese of Trier, in English historically also known as ''Treves'' (IPA "tɾivz") from French ''Trèves'', is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the Catholic church in Germany.Maria Kunigunde Dorothea Hedwig Franziska Xaveria Florentina (born Warsaw, 10 November 1740 – died Dresden, 8 April 1826),

File:August III.jpg, Portrait of Crown Prince Augustus

File:August III the Saxon in Polish costume.PNG, Augustus III in Sarmatian costume, by

Princess-Abbess

A prince-abbot (german: Fürstabt) is a title for a clergy, cleric who is a Prince of the Church (like a Prince-bishop), in the sense of an ''ex officio'' temporal lord of a feudalism, feudal entity, usually a Imperial State, State of the Holy R ...

of Thorn

Thorn(s) or The Thorn(s) may refer to:

Botany

* Thorns, spines, and prickles, sharp structures on plants

* ''Crataegus monogyna'', or common hawthorn, a plant species

Comics and literature

* Rose and Thorn, the two personalities of two DC Com ...

and Essen

Gallery

Louis de Silvestre

Louis de Silvestre (23 June 1675 – 11 April 1760) was a French portrait and history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the invention of writing sy ...

, ''c.''1737

File:Coat of arms of Augustus III of Poland as vicar of the Holy Roman Empire.svg, Coat of arms of Augustus III of Poland as vicar of the Holy Roman Empire

File:Polish Royal Banner of The House of Wettin.svg, Banner of Poland during the reign of Augustus III of Poland

File:POL JS Mock Wjazd Augusta III do Warszawy.jpg, ''Entry of Augustus III into Warsaw'' by Johann Samuel Mock

File:Köler Regalia of Augustus III and Maria Josepha.jpg, Crown Regalia of King Augustus and Maria Josepha

File:POLAND, DANZIG (GDANSK), AUGUSTUS III 1763 -6 GROSCHEN a - Flickr - woody1778a.jpg, 6 groschen

Groschen (; from la, grossus "thick", via Old Czech ') a (sometimes colloquial) name for various coins, especially a silver coin used in various states of the Holy Roman Empire and other parts of Europe. The word is borrowed from the late L ...

, 1763

Ancestry

See also

*History of Saxony

The history of Saxony began with a small tribe living on the North Sea between the Elbe and Eider River in what is now Holstein. The name of this tribe, the Saxons (Latin: ''Saxones''), was first mentioned by the Greek author Ptolemy. The name ...

* History of Poland (1569–1795)

The history of Poland spans over a thousand years, from medieval tribes, Christianization and monarchy; through Poland's Golden Age, expansionism and becoming one of the largest European powers; to its collapse and partitions, two world wars, ...

* Rulers of Saxony

This article lists dukes, electors, and kings ruling over different territories named Saxony from the beginning of the Saxon Duchy in the 6th century to the end of the German monarchies in 1918.

The electors of Saxony from John the Steadfast on ...

* List of Lithuanian rulers

The article is a list of heads of state of Lithuania over historical Lithuanian state. The timeline includes all heads of state of Lithuania as a sovereign entity, legitimately part of a greater sovereign entity, a client state, or a Republics o ...

* Dresden Castle

Dresden Castle or Royal Palace (german: Dresdner Residenzschloss or ) is one of the oldest buildings in Dresden, Germany. For almost 400 years, it was the residence of the electors (1547–1806) and kings (1806–1918) of Saxony from the Alberti ...

– Residence of Augustus III

Notes and references

External links

* . {{DEFAULTSORT:Augustus 03 of Poland 1696 births 1763 deaths 18th-century Polish monarchs Electoral Princes of Saxony Nobility from Dresden Prince-electors of Saxony Grand Dukes of Lithuania Imperial vicars House of Wettin Converts to Roman Catholicism from Lutheranism Polish Roman Catholics Burials at Dresden Cathedral Knights of the Golden Fleece of Austria Polish–Lithuanian military personnel of the War of the Polish Succession Polish people of German descent People of the Silesian Wars Albertine branch Recipients of the Order of the White Eagle (Poland)