Francis Nicholson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In 1688 the Lords of Trade extended the dominion to include

In 1688 the Lords of Trade extended the dominion to include

After James was deposed by William III and

After James was deposed by William III and

Lord Effingham resigned the Virginia governorship in February 1692, beginning a contest between Nicholson and Andros for the Virginia governorship. Andros, who was in London and was a more senior figure, was awarded the post, much to Nicholson's annoyance. The episode deepened a growing dislike between the two men. One contemporary chronicler wrote that Nicholson "especially esentedSir Edmund Andros, against whom he has a particular pique on account of some earlier dealings", and Nicholson, placated with the lieutenant governorship of Maryland, worked from then on to unseat Andros.Lustig, p. 242 When Andros arrived in September 1692, Nicholson graciously received him before sailing for London.

Nicholson was still in England in 1693 when Maryland Governor, Sir Lionel Copley died. Under provisions of his commission, and at the request of the Maryland governor's council, Andros went to Maryland in September 1693 to organize affairs, and again in May 1694 to preside over the provincial court. For these services he was paid £500. When Nicholson, now appointed governor of Maryland, arrived in July, he found the provincial treasury empty, and testily demanded that Andros return the payment. Andros refused, and Nicholson appealed to the Lords of Trade. They ruled in October 1696 that Andros had to return £300. By this time, Nicholson was living in the house of Edward Dorsey.

Nicholson, a committed

Lord Effingham resigned the Virginia governorship in February 1692, beginning a contest between Nicholson and Andros for the Virginia governorship. Andros, who was in London and was a more senior figure, was awarded the post, much to Nicholson's annoyance. The episode deepened a growing dislike between the two men. One contemporary chronicler wrote that Nicholson "especially esentedSir Edmund Andros, against whom he has a particular pique on account of some earlier dealings", and Nicholson, placated with the lieutenant governorship of Maryland, worked from then on to unseat Andros.Lustig, p. 242 When Andros arrived in September 1692, Nicholson graciously received him before sailing for London.

Nicholson was still in England in 1693 when Maryland Governor, Sir Lionel Copley died. Under provisions of his commission, and at the request of the Maryland governor's council, Andros went to Maryland in September 1693 to organize affairs, and again in May 1694 to preside over the provincial court. For these services he was paid £500. When Nicholson, now appointed governor of Maryland, arrived in July, he found the provincial treasury empty, and testily demanded that Andros return the payment. Andros refused, and Nicholson appealed to the Lords of Trade. They ruled in October 1696 that Andros had to return £300. By this time, Nicholson was living in the house of Edward Dorsey.

Nicholson, a committed  Nicholson was a supporter of public education, promoting laws to support it, and funded the construction of "King William's School" (which was later incorporated into St. John's College). He became embroiled in a dispute with

Nicholson was a supporter of public education, promoting laws to support it, and funded the construction of "King William's School" (which was later incorporated into St. John's College). He became embroiled in a dispute with  Nicholson was exposed to French activities on the

Nicholson was exposed to French activities on the

During

During

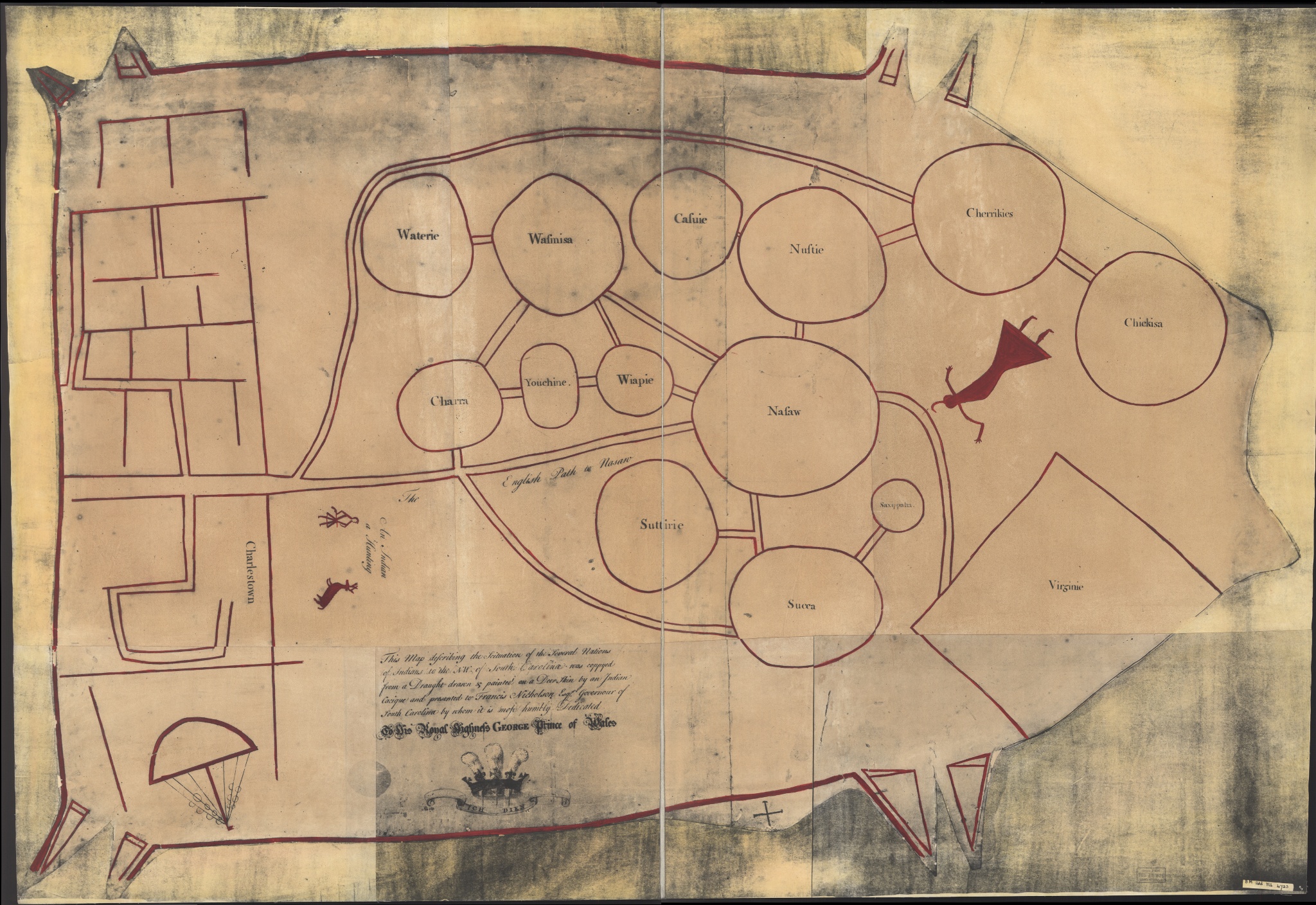

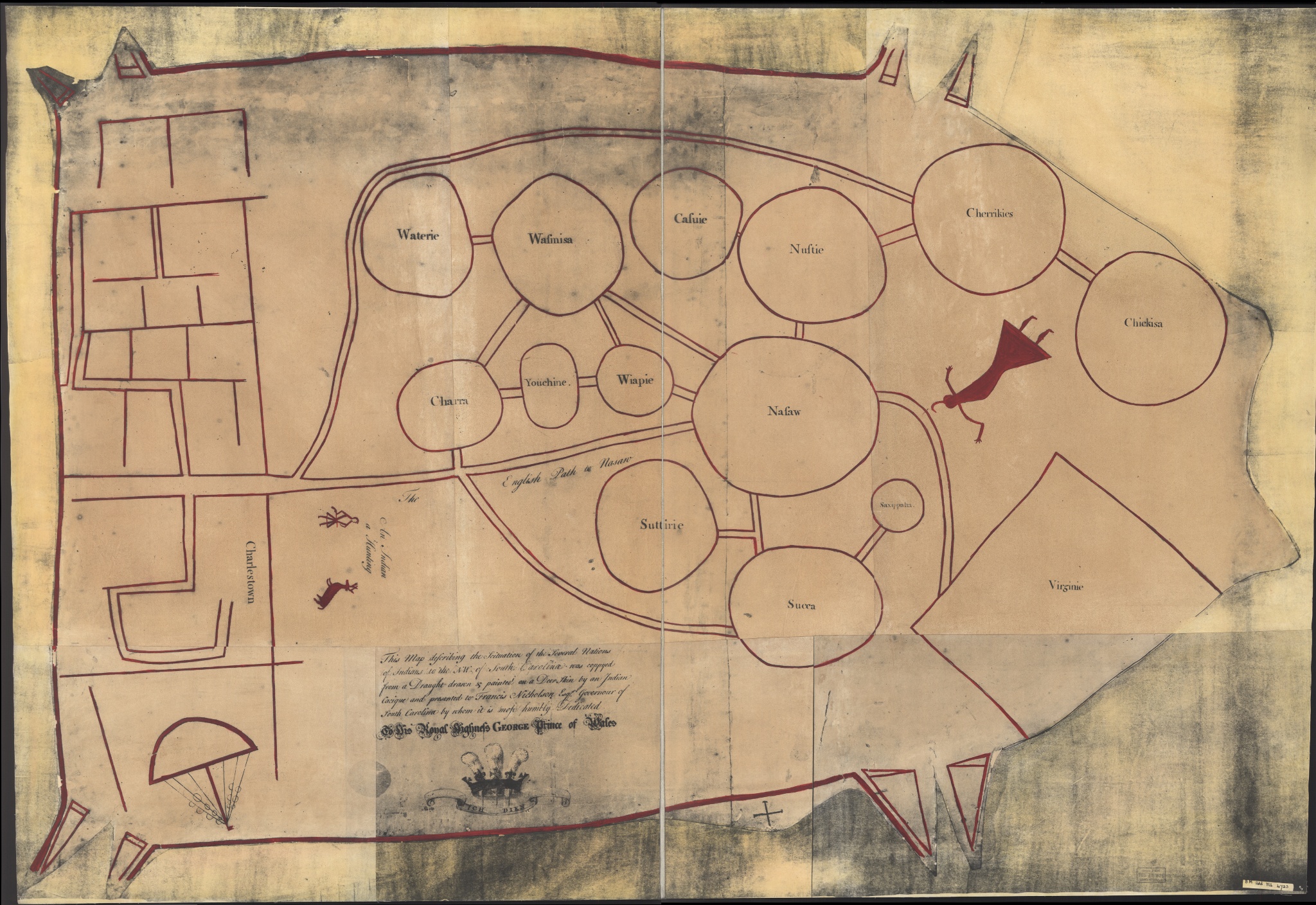

Nicholson next served as the first royal governor of South Carolina from 1721 to 1725. The colonists had rebelled against the rule of the proprietors, and Nicholson was appointed in response to their request for crown governance. The rebellion had been prompted by inadequate response by the proprietors to Indian threats, so Nicholson brought with him some British troops.Webb (1966), p. 547 He established a council composed primarily of supporters of the rebellion, and gave it significant latitude to control colonial affairs. As he had in some of his other posts, he used enforcement of the Navigation Acts as a means to crack down on political opposition. He established local governments modeled on those he set up in Maryland and Virginia, including the 1722 incorporation of Charleston.Weir, p. 107 He expended both public money and his own to further both education and the Church of England, and introduced ground-breaking judicial administration into the colony. He negotiated agreements and territorial boundaries with the

Nicholson next served as the first royal governor of South Carolina from 1721 to 1725. The colonists had rebelled against the rule of the proprietors, and Nicholson was appointed in response to their request for crown governance. The rebellion had been prompted by inadequate response by the proprietors to Indian threats, so Nicholson brought with him some British troops.Webb (1966), p. 547 He established a council composed primarily of supporters of the rebellion, and gave it significant latitude to control colonial affairs. As he had in some of his other posts, he used enforcement of the Navigation Acts as a means to crack down on political opposition. He established local governments modeled on those he set up in Maryland and Virginia, including the 1722 incorporation of Charleston.Weir, p. 107 He expended both public money and his own to further both education and the Church of England, and introduced ground-breaking judicial administration into the colony. He negotiated agreements and territorial boundaries with the

Biography of Francis Nicholson

at Chronicles of America (chroniclesofamerica.com)

at blupete.com

at carolana.com

Francis Nicholson

at ''Encyclopedia Virginia'' (encyclopediavirginia.org) *

Francis Nicholson

at The Historical Marker Database (HMdb.org) * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Nicholson, Francis 1655 births 1728 deaths British Army generals British military personnel of Queen Anne's War Burials at St George's, Hanover Square Colonial Governors of Maryland Colonial governors of South Carolina Colonial governors of Virginia Fellows of the Royal Society Governors of the Colony of Nova Scotia Governors of the Dominion of New England People from Richmondshire (district) Soldiers of the Tangier Garrison

Lieutenant-General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

Francis Nicholson (12 November 1655 – ) was a British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

general

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

and colonial official

An official is someone who holds an office (function or mandate, regardless whether it carries an actual working space with it) in an organization or government and participates in the exercise of authority, (either their own or that of their su ...

who served as the Governor of South Carolina

The governor of South Carolina is the head of government of South Carolina. The governor is the ''ex officio'' commander-in-chief of the National Guard when not called into federal service. The governor's responsibilities include making yea ...

from 1721 to 1725. He previously was the Governor of Nova Scotia

The following is a list of the governors and lieutenant governors of Nova Scotia. Though the present day office of the lieutenant governor in Nova Scotia came into being only upon the province's entry into Canadian Confederation in 1867, the po ...

from 1712 to 1715, the Governor of Virginia

The governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia serves as the head of government of Virginia for a four-year term. The incumbent, Glenn Youngkin, was sworn in on January 15, 2022.

Oath of office

On inauguration day, the Governor-elect takes th ...

from 1698 to 1705, the Governor of Maryland

The Governor of the State of Maryland is the head of government of Maryland, and is the commander-in-chief of the state's National Guard units. The Governor is the highest-ranking official in the state and has a broad range of appointive powers ...

from 1694 to 1698, the Lieutenant Governor of Virginia

The lieutenant governor of Virginia is a constitutional officer of the Commonwealth of Virginia. The lieutenant governor is elected every four years along with the governor and attorney general.

The office is currently held by Winsome Earle ...

from 1690 to 1692, and the Lieutenant Governor of the Dominion of New England

The Dominion of New England in America (1686–1689) was an administrative union of English colonies covering New England and the Mid-Atlantic Colonies (except for Delaware Colony and the Province of Pennsylvania). Its political structure repres ...

from 1688 to 1689.

Nicholson's military service included time in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

and Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, after which he was sent to North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

as leader of the troops supporting Governor, Sir Edmund Andros

Sir Edmund Andros (6 December 1637 – 24 February 1714) was an English colonial administrator in British America. He was the governor of the Dominion of New England during most of its three-year existence. At other times, Andros served ...

in the Dominion of New England

The Dominion of New England in America (1686–1689) was an administrative union of English colonies covering New England and the Mid-Atlantic Colonies (except for Delaware Colony and the Province of Pennsylvania). Its political structure repres ...

. There he distinguished himself, and was appointed lieutenant governor of the Dominion in 1688. After news of the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

and the overthrow of King James II reached the colonies in 1689, Andros was himself overthrown in the Boston Revolt. Nicholson himself was soon caught up in the civil unrest from Leisler's Rebellion

Leisler's Rebellion was an uprising in late-17th century colonial New York in which German American merchant and militia captain Jacob Leisler seized control of the southern portion of the colony and ruled it from 1689 to 1691. The uprising too ...

in New York Town, and afterwards fled to England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

.

Nicholson next served as lieutenant governor or governor of the colonial Provinces of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

and Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean t ...

. He supported the founding of the College of William and Mary

The College of William & Mary (officially The College of William and Mary in Virginia, abbreviated as William & Mary, W&M) is a public research university in Williamsburg, Virginia. Founded in 1693 by letters patent issued by King William ...

, at Williamsburg, Virginia

Williamsburg is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, it had a population of 15,425. Located on the Virginia Peninsula, Williamsburg is in the northern part of the Hampton Roads metropolitan area. It is ...

, and quarreled with Andros after Andros was selected over him as Governor of Virginia

The governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia serves as the head of government of Virginia for a four-year term. The incumbent, Glenn Youngkin, was sworn in on January 15, 2022.

Oath of office

On inauguration day, the Governor-elect takes th ...

. In 1709, he became involved in colonial military actions during Queen Anne's War

Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) was the second in a series of French and Indian Wars fought in North America involving the colonial empires of Great Britain, France, and Spain; it took place during the reign of Anne, Queen of Great Britain. In E ...

(1702-1713, War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

), leading an aborted expedition against the French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

in New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

(modern Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

). He then led the expedition that successfully captured Port Royal, Acadia (Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

) on 2 October 1710. Afterward he served as governor of Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

and Placentia, and was the first royal governor of the colonial Province of South Carolina following a rebellion against its proprietors. He rose to the rank of Lieutenant-General, and died a bachelor in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, in 1728.

Nicholson supported public education in the colonies, and was a member of both the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts and the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

. He also influenced American architecture, being responsible for the planned layout and design of colonial/provincial capitals of Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Maryland and the county seat of, and only incorporated city in, Anne Arundel County. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east ...

and Williamsburg, Virginia

Williamsburg is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, it had a population of 15,425. Located on the Virginia Peninsula, Williamsburg is in the northern part of the Hampton Roads metropolitan area. It is ...

. He was one of the earliest advocates of colonial union, principally for reasons of defense against common enemies.

Early life and military service

Nicholson was born in the village of Downholme,Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, on 12 November 1655. Little is known of his ancestry or early life, although he apparently received some education.Dunn, p. 61 He served as a page

Page most commonly refers to:

* Page (paper), one side of a leaf of paper, as in a book

Page, PAGE, pages, or paging may also refer to:

Roles

* Page (assistance occupation), a professional occupation

* Page (servant), traditionally a young m ...

in the household of Charles Paulet (later the Marquess of Winchester and the Duke of Bolton), under whose patronage his career would be advanced. He waited on Paulet's daughter Jane, who married John Egerton, Earl of Bridgewater, another patron who promoted his career.

His military career began in January 1678 when Paulet purchased for him an ensign's commission in the Holland Regiment, in which he saw service against the French in Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to cultu ...

.Webb (1966), p. 515Dunn, p. 62 The regiment saw no combat, and was disbanded at the end of the year. In July 1680 he purchased a staff lieutenant's commission in the newly formed 2nd Tangier Regiment, which was sent to English Tangier

English Tangier was the period in Moroccan history in which the city of Tangier was occupied by England as part of the English colonial empire from 1661 to 1684. Tangier had been under Portuguese control before King Charles II acquired the c ...

to reinforce the garrison holding the city. Tangier's council was then headed by the Duke of York

Duke of York is a title of nobility in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. Since the 15th century, it has, when granted, usually been given to the second son of English (later British) monarchs. The equivalent title in the Scottish peerage was ...

(later King James II), and its governor was Colonel Percy Kirke. Nicholson distinguished himself in the service, carrying dispatches between the enemy Moroccan camp, Tangier, and London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

. In addition to favorable notice from Kirke, this brought Nicholson to the attention of the powerful colonial secretary, William Blathwayt.Dunn, p. 63 Tangier was abandoned in 1683, and his regiment returned to England. During the service in Tangier he met a number of people who would figure prominently North American colonial history, including Thomas Dongan

Thomas Dongan, (pronounced "Dungan") 2nd Earl of Limerick (1634 – 14 December 1715), was a member of the Irish Parliament, Royalist military officer during the English Civil War, and Governor of the Province of New York. He is noted for ...

and Alexander Spotswood.

Nicholson was probably with the regiment when it put down Monmouth's Rebellion

The Monmouth Rebellion, also known as the Pitchfork Rebellion, the Revolt of the West or the West Country rebellion, was an attempt to depose James II, who in February 1685 succeeded his brother Charles II as king of England, Scotland and Ir ...

in 1685, but his role in some of the more unsavory behaviour on the part of Kirke's troops is unknown. Kirke, who had been selected by Charles II as the governor of the prospective Dominion of New England

The Dominion of New England in America (1686–1689) was an administrative union of English colonies covering New England and the Mid-Atlantic Colonies (except for Delaware Colony and the Province of Pennsylvania). Its political structure repres ...

, was strongly criticized for his role in the quashing of the rebellion, and James withdrew his nomination. The dominion's governorship instead went to Sir Edmund Andros

Sir Edmund Andros (6 December 1637 – 24 February 1714) was an English colonial administrator in British America. He was the governor of the Dominion of New England during most of its three-year existence. At other times, Andros served ...

, and Nicholson, now a captain, accompanied Andros as commander of a company of infantry to Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

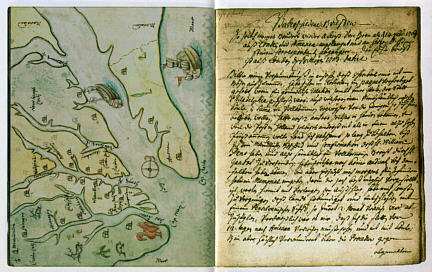

in October 1686.Dunn, p. 64 Andros sent Nicholson on what was essentially a reconnaissance mission to French Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17th and earl ...

. Under the cover of delivering a letter protesting a variety of issues to the Acadian governor, Nicholson made careful observations of Port Royal's defenses. Nicholson impressed Andros in this service, and was soon appointed to the dominion's council.

Dominion lieutenant governor

In 1688 the Lords of Trade extended the dominion to include

In 1688 the Lords of Trade extended the dominion to include New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

and East

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fac ...

and West Jersey

West Jersey and East Jersey were two distinct parts of the Province of New Jersey. The political division existed for 28 years, between 1674 and 1702. Determination of an exact location for a border between West Jersey and East Jersey was ofte ...

. Nicholson was commissioned the dominion's lieutenant governor, and traveled with Andros to New York to take control of those colonies. Nicholson's rule, in which he was assisted by a local council but no legislative assembly, was seen by many New Yorkers as the next in a line of royal governors who "had in a most arbitrary way subverted our ancient privileges".Webb (1966), p. 522 Nicholson justified his rule by stating that the colonists were "a conquered people, and therefore ... could not could not so much sclaim rights and priviledges as Englishmen".

Nicholson was at first seen as an improvement over the Catholic Thomas Dongan, the outgoing governor. However, the province's old guard was unhappy that Andros removed all of the provincial records to Boston, and then Nicholson alarmed the sometimes hardline Protestant population by preserving the trappings of the chapel in Fort James that Dongan and the handful of New York's Catholics had used for worship. In response to a rumored Dutch invasion of England (a rumor that turned out to be true), Nicholson in January 1689 ordered the provincial militias to be on alert to protect the province for the king. Unknown to Nicholson, events in England had already changed things.

Rebellion in Boston

After James was deposed by William III and

After James was deposed by William III and Mary II

Mary II (30 April 166228 December 1694) was Queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland, co-reigning with her husband, William III & II, from 1689 until her death in 1694.

Mary was the eldest daughter of James, Duke of York, and his first wife A ...

in the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

in late 1688, Massachusetts rose up in rebellion against Andros, arresting him and other dominion leaders in Boston.Dunn, p. 65 The revolt rapidly spread through the dominion, and the New England colonies quickly restored their pre-dominion governments. When news of the Boston revolt reached New York a week later,Webb (1966), p. 523 Nicholson took no steps to announce news of it, or of the revolution in England, for fear of raising prospects of rebellion in New York. When word of the Boston revolt reached Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated island in the southeastern region of the U.S. state of New York, part of the New York metropolitan area. With over 8 million people, Long Island is the most populous island in the United States and the 18 ...

, politicians and militia leaders became more assertive, and by mid-May dominion officials had been ousted from a number of communities. At the same time, Nicholson learned that France had declared war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the signing of a document) by an authorized party of a national government, ...

on England, bringing the threat of French and Indian attacks on New York's northern frontier. In an attempt to mollify panicked citizenry over rumored Indian raids, Nicholson invited the militia to join the army garrison at Fort James.Webb (1966), p. 524

Because New York's defenses were in poor condition, Nicholson's council voted to impose import duties to improve them. This move was met with immediate resistance, with a number of merchants refusing to pay the duty. One in particular was Jacob Leisler

Jacob Leisler ( – May 16, 1691) was a German-born colonist who served as a politician in the Province of New York. He gained wealth in New Amsterdam (later New York City) in the fur trade and tobacco business. In what became known as Leisler ...

, a well-born German Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John C ...

immigrant merchant and militia captain. Leisler was a vocal opponent of the dominion regime, which he saw as an attempt to impose "popery

The words Popery (adjective Popish) and Papism (adjective Papist, also used to refer to an individual) are mainly historical pejorative words in the English language for Roman Catholicism, once frequently used by Protestants and Eastern Orthodox ...

" on the province, and may have played a role in subverting Nicholson's regulars.Webb (1998), p. 202 On 22 May Nicholson's council was petitioned by the militia, who, in addition to seeking more rapid improvement to the city's defenses, also wanted access to the powder magazine in the fort. This latter request was denied, heightening concerns that the city had inadequate powder supplies. This concern was further exacerbated when city leaders began hunting through the city for additional supplies.

Rebellion in New York

A minor incident on 30 May 1689 in which Nicholson made an intemperate remark to a militia officer then flared into open rebellion. Nicholson, who was well known for his temper, told the officer "I rather would see the Towne on fire than to be commanded by you".McCormick, p. 179 Rumors flew around the town that Nicholson was in fact prepared to burn it down. The next day Nicholson summoned the officer, and demanded he surrender his commission.Abraham de Peyster

Abraham de Peyster (July 8, 1657 – August 3, 1728) was the 20th mayor of New York City from 1691 to 1694, and served as Governor of New York, 1700–1701.

Early life

De Peyster was born in New Amsterdam on July 8, 1657, to Johannes de Peyst ...

, the officer's commander and one of the wealthiest men in the city, then engaged in a heated argument with Nicholson, after which de Peyster and his brother Johannis, also a militia captain, stormed out of the council chamber.

The militia was called out, and descended en masse to Fort James, which they occupied. An officer was sent to the council to demand the keys to the powder magazine, which Nicholson eventually surrendered, to "hinder and prevent bloodshed and further mischiefe". The following day, a council of militia officers called on Jacob Leisler to take command of the city militia. He did so, and the rebels issued a declaration that they would hold the fort on behalf of the new monarchs until they sent a properly accredited governor.

At this point the militia controlled the fort, which gave them control over the harbor. When ships arrived in the harbor, they brought passengers and captains directly to the fort, cutting off outside communications to Nicholson and his council. On 6 June, Nicholson decided to leave for England, and began gathering depositions for use in proceedings there. He left the city on 10 June for the Jersey shore, where he hoped to join Thomas Dongan, who was expected to sail for England soon thereafter.McCormick, p. 210 However, it was not until 24 June that he actually managed to sail; he was denied passage on a number of ships, and eventually purchased a share of Dongan's brigantine

A brigantine is a two-masted sailing vessel with a fully square-rigged foremast and at least two sails on the main mast: a square topsail and a gaff sail mainsail (behind the mast). The main mast is the second and taller of the two masts.

Ol ...

in order to get away. In the meantime, Leisler proclaimed the rule of William and Mary on 22 June, and on the 28th a provincial committee of safety, acting in the absence of legitimate authority, chose Leisler to be the province's commander-in-chief.

Upon Nicholson's arrival in London in August, he outlined the situation in New York to the king and the Lords of Trade, urging the appointment of a new governor of New York, preferably himself. Despite the efforts of Charles Paulet (now Duke of Bolton) and other patrons, William in November instead chose Colonel Henry Sloughter

Henry Sloughter (died July 23, 1691) was briefly colonial governor of New York in 1691. Sloughter was the governor who put down Leisler's Rebellion, which had installed Jacob Leisler as ''de facto'' governor in 1689. He died suddenly in July 16 ...

to be the next governor of New York. The king did, however, acknowledge Nicholson's efforts with the lieutenant governorship of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

.Sommerville, p. 219

Virginia and Maryland

Nicholson was lieutenant governor of Virginia until 1692, serving under the absentee Governor Lord Howard of Effingham. During this tenure, he was instrumental in the creation of theCollege of William and Mary

The College of William & Mary (officially The College of William and Mary in Virginia, abbreviated as William & Mary, W&M) is a public research university in Williamsburg, Virginia. Founded in 1693 by letters patent issued by King William ...

and named as one of its original trustees. He worked to improve the provincial militia, and approved the establishment of additional ports of trade in the province. The latter was not without some opposition from some of the larger merchants in the province, who saw the additional ports as a competitive threat. During this time Nicholson was one of the only high-level representatives of Crown Rule in the colonies: most Crown Rule had been eliminated in the northern colonies, and the other southern colonies were governed by proprietary governors. Nicholson recommended to the King that, in order to better establish a common social order and a coordinated defense, Crown Rule should be established over all of the colonies as quickly as possible, including the conversion of the proprietary colonies to crown colonies.

Lord Effingham resigned the Virginia governorship in February 1692, beginning a contest between Nicholson and Andros for the Virginia governorship. Andros, who was in London and was a more senior figure, was awarded the post, much to Nicholson's annoyance. The episode deepened a growing dislike between the two men. One contemporary chronicler wrote that Nicholson "especially esentedSir Edmund Andros, against whom he has a particular pique on account of some earlier dealings", and Nicholson, placated with the lieutenant governorship of Maryland, worked from then on to unseat Andros.Lustig, p. 242 When Andros arrived in September 1692, Nicholson graciously received him before sailing for London.

Nicholson was still in England in 1693 when Maryland Governor, Sir Lionel Copley died. Under provisions of his commission, and at the request of the Maryland governor's council, Andros went to Maryland in September 1693 to organize affairs, and again in May 1694 to preside over the provincial court. For these services he was paid £500. When Nicholson, now appointed governor of Maryland, arrived in July, he found the provincial treasury empty, and testily demanded that Andros return the payment. Andros refused, and Nicholson appealed to the Lords of Trade. They ruled in October 1696 that Andros had to return £300. By this time, Nicholson was living in the house of Edward Dorsey.

Nicholson, a committed

Lord Effingham resigned the Virginia governorship in February 1692, beginning a contest between Nicholson and Andros for the Virginia governorship. Andros, who was in London and was a more senior figure, was awarded the post, much to Nicholson's annoyance. The episode deepened a growing dislike between the two men. One contemporary chronicler wrote that Nicholson "especially esentedSir Edmund Andros, against whom he has a particular pique on account of some earlier dealings", and Nicholson, placated with the lieutenant governorship of Maryland, worked from then on to unseat Andros.Lustig, p. 242 When Andros arrived in September 1692, Nicholson graciously received him before sailing for London.

Nicholson was still in England in 1693 when Maryland Governor, Sir Lionel Copley died. Under provisions of his commission, and at the request of the Maryland governor's council, Andros went to Maryland in September 1693 to organize affairs, and again in May 1694 to preside over the provincial court. For these services he was paid £500. When Nicholson, now appointed governor of Maryland, arrived in July, he found the provincial treasury empty, and testily demanded that Andros return the payment. Andros refused, and Nicholson appealed to the Lords of Trade. They ruled in October 1696 that Andros had to return £300. By this time, Nicholson was living in the house of Edward Dorsey.

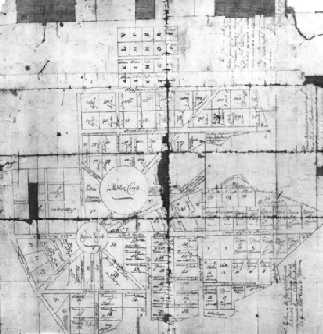

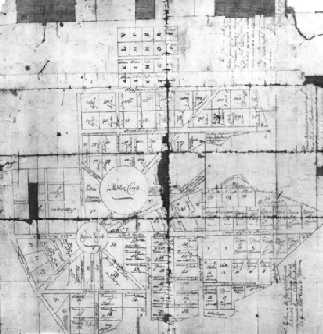

Nicholson, a committed Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of t ...

as a member of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

, sought to reduce Roman Catholic influence in the Maryland government, and moved the old colonial capital from the Catholic stronghold of St. Mary's City in southern Maryland's St. Mary's County along the Potomac River

The Potomac River () drains the Mid-Atlantic United States, flowing from the Potomac Highlands into Chesapeake Bay. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map. Retrieved Augu ...

to what was then called "Anne Arundel's Town" (also known briefly as "Providence"), which was later renamed "Annapolis" in honour of the future monarch, Princess Anne

Anne, Princess Royal (Anne Elizabeth Alice Louise; born 15 August 1950), is a member of the British royal family. She is the second child and only daughter of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, and the only sister of ...

. He chose its site and laid out the plan for the town, placing the Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of t ...

(later Episcopal church and the state house in well-designed public spaces (known later as "State Circle" and "Church Circle") and the use of diagonal avenues to connect various parts of the town (foreseeing details of Pierre L'Enfant

Pierre "Peter" Charles L'Enfant (; August 2, 1754June 14, 1825) was a French-American military engineer who designed the basic plan for Washington, D.C. (capital city of the United States) known today as the L'Enfant Plan (1791).

Early life ...

's, (1754–1825), plan for the National Capital or "Federal City" in Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

and the District of Columbia

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle (Washington, D.C.), Logan Circle, Jefferson Memoria ...

, a century later. Architectural historian Mark Childs describes Annapolis, along with Williamsburg, Virginia

Williamsburg is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, it had a population of 15,425. Located on the Virginia Peninsula, Williamsburg is in the northern part of the Hampton Roads metropolitan area. It is ...

, which Nicholson also laid out during his later tenure there, as some of the best-designed towns in the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

.

Nicholson was a supporter of public education, promoting laws to support it, and funded the construction of "King William's School" (which was later incorporated into St. John's College). He became embroiled in a dispute with

Nicholson was a supporter of public education, promoting laws to support it, and funded the construction of "King William's School" (which was later incorporated into St. John's College). He became embroiled in a dispute with William Penn

William Penn ( – ) was an English writer and religious thinker belonging to the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, a North American colony of England. He was an early advocate of democracy a ...

from the Middle Atlantic colony to the north, over how to deal with the issue of piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

. In Maryland, Nicholson vigorously cracked down on the practices of some colonists to tolerate pirates, who brought goods and hard currency into the provinces. Aware that Penn's governor William Markham was similarly tolerant (he was said to be taking bribes to allow pirates such as Thomas Day Thomas Day may refer to:

Sports

* Tom Day (rugby union) (1907–1980), Welsh rugby union player

* Tom Day (American football) (1935–2000), American football player

* Tom Day (footballer) (born 1997), English footballer

Others

* Thomas Day (wri ...

to trade in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

), Nicholson ordered that ships destined for Pennsylvania be stopped and searched in Maryland waters, and collected duties if they were carrying European finished goods. Penn protested to the Board of Trade

The Board of Trade is a British government body concerned with commerce and industry, currently within the Department for International Trade. Its full title is The Lords of the Committee of the Privy Council appointed for the consideration of ...

, and the dispute subsided when Nicholson moderated his tactics. During Nicholson's rule in Maryland, he specifically denied that the colonists had the Rights of Englishmen, writing that "if I had not hampered them olonial interestsin Maryland, and kept them under, I should never have been able to govern them." His feud with pirates took a personal turn when in 1700 he accompanied the captain of HMS ''Shoreham'' in a fierce all-day battle against French pirate Louis Guittar

Louis Guittar (alternatively spelled Lewis Gittar, died 13 November 1700) was a French pirate active in the Caribbean, the West Indies, and New England during the late 1690s and 1700s.

History

Based in St. Malo in the late 1690s, Guittar comma ...

. The defeated pirates asked Nicholson for quarter and pardon; he granted them quarter but referred them to King William III of England

William III (William Henry; ; 4 November 16508 March 1702), also widely known as William of Orange, was the sovereign Prince of Orange from birth, Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel in the Dutch Republic f ...

for mercy, in whose courts Guittar and his crew were all sentenced to hang.

Nicholson's feud with Andros persisted, and Nicholson acquired a powerful ally in James Blair, the founder of the College of William and Mary. The two were able to gain the support of the Anglican establishment in England against Andros, and filed a long list of complaints with the Lords of Trade. These efforts were successful in convincing Andros to request permission to resign, and in December 1698, Nicholson was given the governorship of Virginia. Andros angrily refused to give Nicholson his records. During his term, which lasted until 1705, Nicholson was largely at the mercy of his council, which was dominated by a small group of powerful Virginia families. The Andros rule had been so unpopular in Virginia that Nicholson's instructions gave him little leeway in acting without their consent. At one point Nicholson characterized the Virginia council as "mere brutes who understand not manners". Nicholson made a number of unsuccessful attempts to alter the balance of power, including moving the provincial capital from Jamestown to Middle Plantation, which was renamed Williamsburg.Steele, pp. 71–72 Although he was opposed by the upper house, the colonial legislature was generally supportive of him, and he continued to be favored by the London government.

Nicholson was exposed to French activities on the

Nicholson was exposed to French activities on the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

while governor of Maryland. He warned the Board of Trade in 1695 that the French were working to complete the designs of explorer Robert La Salle to gain control of the river and dominate the Indian relations in the interior, which "may be of fatal consequence" to the English colonies. He reiterated the warning in a 1698 report, and suggested that the Board of Trade issue instructions to all of the governors encouraging the development of trade with Indians across the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. The ...

. "I am afraid", he wrote, "that now please God, there is a peace, the French will be able to doe more dammage to these Countrys, than they were able to doe in the ing William'sWar ."Crane, p. 61 These observations were among the earliest anyone made concerning the threat French expansion posed to the English, and some of his suggestions were ultimately adopted as policy. He actively promoted the idea of expansionist trade on the frontier with other colonial governors, including Bellomont of New York, and Blake of South Carolina.

Following a political crisis in England and the accession of Queen Anne to the throne in 1702, a Tory ministry emerged that sidelined most of Nicholson's Whig patrons. Despite his best efforts to retain his post, he was recalled and replaced in 1705 by Edward Nott Colonel Edward Nott (1657 – August 23, 1706) was an English Colonial Governor of Virginia. He was appointed by Queen Anne on either April 25, 1705 or August 15, 1705. His administration lasted only one year, as he died in 1706 at the age of 49. ...

. He returned to London, where he was active in the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, and was awarded membership in the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

for his scientific observations of North America. He also acted as a consultant to the Board of Trade, and thus maintained an awareness of colonial issues.

Queen Anne's War

During

During King William's War

King William's War (also known as the Second Indian War, Father Baudoin's War, Castin's War, or the First Intercolonial War in French) was the North American theater of the Nine Years' War (1688–1697), also known as the War of the Grand Alli ...

in the 1690s Nicholson asked the House of Burgesses to appropriate money for New York's defense, since it was threatened from New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

and acted as a buffer to protect Virginia. The Burgesses refused, even after Nicholson appealed to London. When Queen Anne's War

Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) was the second in a series of French and Indian Wars fought in North America involving the colonial empires of Great Britain, France, and Spain; it took place during the reign of Anne, Queen of Great Britain. In E ...

broke out in 1702, Nicholson lent New York £900 of his own money, with the expectation that it would be repaid from Virginia's quit rent

Quit rent, quit-rent, or quitrent is a tax or land tax imposed on occupants of freehold or leased land in lieu of services to a higher landowning authority, usually a government or its assigns.

Under feudal law, the payment of quit rent (La ...

s (it was not). The publicity of this scheme increased dislike of him in Virginia, and may have played a role in his recall. Virginia was not militarily affected by the war. These efforts by Nicholson to gain broader colonial support for the war were followed by larger proposals to London, suggesting, for example, that all of the colonies be joined under a single viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning " ...

, who would have power of taxation and control of a standing army. According to historian John Fiske, Nicholson was one of the first people to propose uniting all of the North American colonies in this way.

In the course of the ten-year conflict in North America now known as Queen Anne's War, Samuel Vetch, a Scottish businessman with interests in New York and New England, came to London during the winter of 1708–9 and proposed to the Queen and the Board of Trade a major assault on New France.McCully, p. 442 He recruited Nicholson to join the effort, which was to include a sea-based attack on Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirte ...

with Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

support, and a land-based expedition to ascend the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between Ne ...

, descend Lake Champlain

, native_name_lang =

, image = Champlainmap.svg

, caption = Lake Champlain-River Richelieu watershed

, image_bathymetry =

, caption_bathymetry =

, location = New York/ Vermont in the United States; and Quebec in Canada

, coords =

, type ...

, and attack Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...

. Nicholson was given command of the land-based effort while Vetch was to command the provincial militia of New England that were to accompany the fleet. Arriving in Boston in April 1709 Nicholson and Vetch immediately began raising the forces and supplies needed for these operations. Nicholson was able to draw on his earlier connections to New York's aristocracy to recruit the needed forces from there, with additional units coming from New Jersey and Connecticut. He raised a force of about 1,500 regulars and provincial militia and 600 Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian Peoples, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Indigenous confederations in North America, confederacy of First Nations in Canada, First Natio ...

, and in June began the construction of three major encampments between Stillwater, just north of Albany, and the southern end of Lake Champlain, while awaiting word of the fleet's arrival in Boston. The expedition turned out to be a disaster. Many men became sick and died from the poor conditions in the camps as the summer dragged on without any news of the fleet. Supplies ran short the men became mutinous and began deserting. Finally, in October Nicholson learned that, due to circumstances in Europe, the fleet's participation had been canceled in July. By this time the men were deserting by whole units and destroyed all of the fortifications and stores.

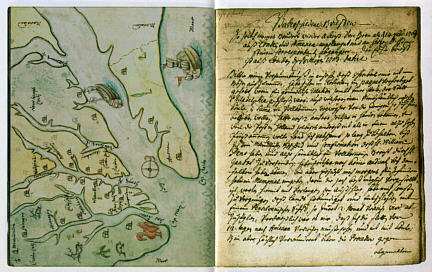

In the aftermath of the debacle Nicholson returned to London, taking four Indian chiefs with him, and petitioned Queen Anne for permission to lead a more limited expedition against Port Royal

Port Royal is a village located at the end of the Palisadoes, at the mouth of Kingston Harbour, in southeastern Jamaica. Founded in 1494 by the Spanish, it was once the largest city in the Caribbean, functioning as the centre of shipping and ...

, the capital of French Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17th and earl ...

. The Queen granted the petition, and Nicholson was in charge of the forces that captured Port Royal on 2 October 1710. This battle marked the conquest of Acadia, and began permanent British control over the territory they called Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

. Nicholson published an account of the expedition in his 1711 ''Journal of an Expedition for the Reduction of Port Royal''. The victorious Nicholson returned to England to petition Queen Anne for another expedition to capture the center of New France, Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirte ...

. The resulting naval expedition was led by Admiral Hovenden Walker, and Nicholson led an associated land expedition that retraced the route he had taken in 1709 toward Lake Champlain

, native_name_lang =

, image = Champlainmap.svg

, caption = Lake Champlain-River Richelieu watershed

, image_bathymetry =

, caption_bathymetry =

, location = New York/ Vermont in the United States; and Quebec in Canada

, coords =

, type ...

. Many ships of Walker's fleet foundered on rocks near the mouth of the Saint Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connecting ...

, and the whole expedition was cancelled, much to Nicholson's anger; he was reported to tear off his wig and throw it to the ground when he heard the news.

Nova Scotia and South Carolina

Nicholson returned to London after the failed expedition, and began working to acquire for himself the governorship of Nova Scotia. After the 1710 victory, Samuel Vetch had become its governor, but his rule over the colony (where he only really controlled Port Royal itself) was somewhat ineffective. Vetch and the Tory ministry then in power disagreed on how to handle affairs, especially with respect to the resident French Catholic population, and Nicholson capitalized on these complaints. In a dispute marked by bitterness and sometimes extreme accusations (Vetch, for example, accused Nicholson of Jacobite sympathies), Nicholson was awarded the post in October 1712. His commission also included the governorship of Placentia, and authority as auditor of all colonial accounts. He only spent a few weeks in Port Royal in 1714, leaving most of the governance to lieutenant governorThomas Caulfeild

Thomas Caulfeild (often also spelled Caulfield, baptized 26 March 1685 – 2 March 1716/7) was an early British Lieutenant-Governor of Nova Scotia. Due to the frequent absence of governors Samuel Vetch and Francis Nicholson, Caulfeild often ac ...

. These few weeks were marked by discord with the Acadians, who sought to capitalize on the change of governor to gain concessions Nicholson was not prepared to give. Nicholson also issued order restricting the interaction between the troops and the town, resulting in the further reduction of already-poor morale in the Port Royal garrison. He also cracked down on open trade between British colonial merchants and the French, requiring the licensing of any British merchant wanting to trade at French ports.

Nicholson spent most of his time as Nova Scotia governor in Boston, where he devoted a significant amount of time investigating Vetch's finances. Vetch interpreted Nicholson's hostile and intrusive examination of his affairs as a largely partisan attempt to smear him. He called Nicholson a "malicious madman" who would do anything that "fury, malice, and madness could inspire." Nicholson attempted to prevent Vetch from sailing for England where he might better defend himself, forcing Vetch to flee beyond Nicholson's reach to New London, Connecticut

New London is a seaport city and a port of entry on the northeast coast of the United States, located at the mouth of the Thames River in New London County, Connecticut. It was one of the world's three busiest whaling ports for several decade ...

, in order to get a ship for England. With the accession of George I to the throne and the change to a Whig ministry, Vetch succeeded in clearing his name and recovered his post from Nicholson, who was accused by Vetch and others of neglecting the province.

Nicholson next served as the first royal governor of South Carolina from 1721 to 1725. The colonists had rebelled against the rule of the proprietors, and Nicholson was appointed in response to their request for crown governance. The rebellion had been prompted by inadequate response by the proprietors to Indian threats, so Nicholson brought with him some British troops.Webb (1966), p. 547 He established a council composed primarily of supporters of the rebellion, and gave it significant latitude to control colonial affairs. As he had in some of his other posts, he used enforcement of the Navigation Acts as a means to crack down on political opposition. He established local governments modeled on those he set up in Maryland and Virginia, including the 1722 incorporation of Charleston.Weir, p. 107 He expended both public money and his own to further both education and the Church of England, and introduced ground-breaking judicial administration into the colony. He negotiated agreements and territorial boundaries with the

Nicholson next served as the first royal governor of South Carolina from 1721 to 1725. The colonists had rebelled against the rule of the proprietors, and Nicholson was appointed in response to their request for crown governance. The rebellion had been prompted by inadequate response by the proprietors to Indian threats, so Nicholson brought with him some British troops.Webb (1966), p. 547 He established a council composed primarily of supporters of the rebellion, and gave it significant latitude to control colonial affairs. As he had in some of his other posts, he used enforcement of the Navigation Acts as a means to crack down on political opposition. He established local governments modeled on those he set up in Maryland and Virginia, including the 1722 incorporation of Charleston.Weir, p. 107 He expended both public money and his own to further both education and the Church of England, and introduced ground-breaking judicial administration into the colony. He negotiated agreements and territorial boundaries with the Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, th ...

, and promoted trade, pursuing policies similar to those he had advocated while in Maryland and Virginia. He introduced a commissioner of Indian affairs into the colonial government, a post that survived until the crown assumed the duties of managing Indian affairs in the 1750s.

Like other colonies, South Carolina suffered from chronic shortages of currency, and issued bills of credit to compensate. During Nicholson's administration this was done several times, but the inflationary consequences did not reach crisis proportions until after he left the colony. It did, however, anger merchant interests enough to raise complaints against him with the Board of Trade. Combined with long-running but false accusations by William Rhett and other supporters of the proprietors that Nicholson was improperly engaged in smuggling, he felt the need to return to England to defend himself against these charges. He returned to London in 1725, carrying with him Cherokee baskets that became part of the earliest collections in the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

.

Personal and later life

Nicholson courted the teenage Lucy Burwell of the Burwell family of Virginia at the turn of the 18th century. Burwell, known for her beauty and charm, did not reciprocate his feelings. Nicholson continued to press Burwell and her parents for the match he desired. Instead, Burwell looked for love and affection of a man of good manners with whom she was compatible. Nicholson's behavior, along with his unpopular policies, drove four Burwell relatives and two others to petitionAnne, Queen of Great Britain

Anne (6 February 1665 – 1 August 1714) was Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland from 8 March 1702 until 1 May 1707. On 1 May 1707, under the Acts of Union, the kingdoms of England and Scotland united as a single sovereign state known as ...

for Nicholson's removal as governor. Titled "Memorial Concerning the Maladministration of Governor Nicholson", it was signed by six councilors John Blair, Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 23rd president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia–a grandson of the ninth pr ...

, Robert Carter, Matthew Page, Philip Ludwell, and John Lightfoot. She married Edmund Berkeley, a successful planter.

In England, Nicholson was promoted to lieutenant-general. He never married, and died in London on 5/16 March 1728/9. He was buried in the parish of St George Hanover Square. A claim cited in some 19th-century biographies that he was knighted turned out to be false when his will was discovered early in the 20th century.

Personality

Nicholson was notorious for his temper. He was, according to historian George Waller, "subject to fits of passion". In one story, an Indian said of Nicholson, "The general is drunk." When informed that Nicholson did not partake of strong drink, the Indian replied, "I do not mean that he is drunk with rum, he was born drunk."Waller, p. 257 Waller also points out that his "hasty and overmastering temper led him into great excesses".Waller, p. 276Legacy

Nicholson Hall of theCollege of William and Mary

The College of William & Mary (officially The College of William and Mary in Virginia, abbreviated as William & Mary, W&M) is a public research university in Williamsburg, Virginia. Founded in 1693 by letters patent issued by King William ...

is named in honour of Francis Nicholson. Additionally the two main streets of Colonial Williamsburg, one block north and south of the central street (Duke of Gloucester St.) are named Francis and Nicholson, in his honour.

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* Includes a detailed discussion of his potential ancestry and his Moroccan service.External links

*Biography of Francis Nicholson

at Chronicles of America (chroniclesofamerica.com)

at blupete.com

at carolana.com

Francis Nicholson

at ''Encyclopedia Virginia'' (encyclopediavirginia.org) *

Francis Nicholson

at The Historical Marker Database (HMdb.org) * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Nicholson, Francis 1655 births 1728 deaths British Army generals British military personnel of Queen Anne's War Burials at St George's, Hanover Square Colonial Governors of Maryland Colonial governors of South Carolina Colonial governors of Virginia Fellows of the Royal Society Governors of the Colony of Nova Scotia Governors of the Dominion of New England People from Richmondshire (district) Soldiers of the Tangier Garrison