Francis Knollys (the elder) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

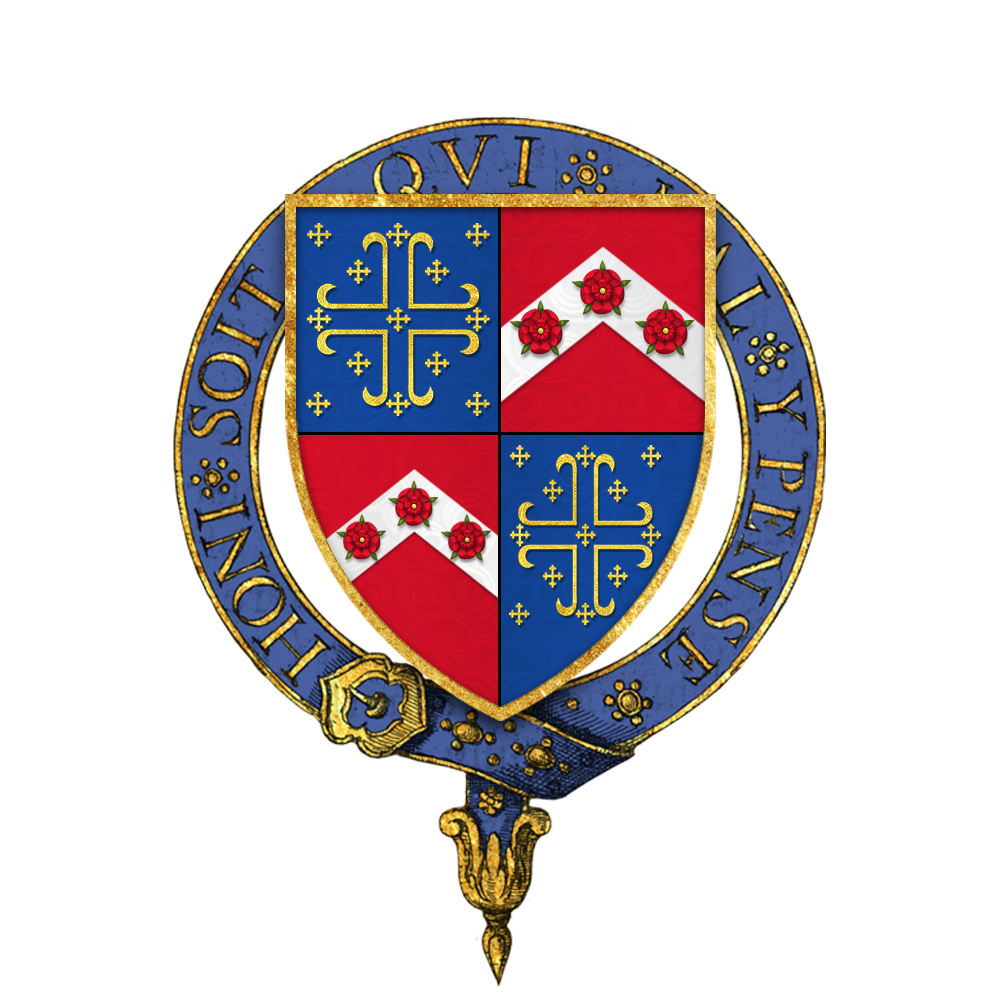

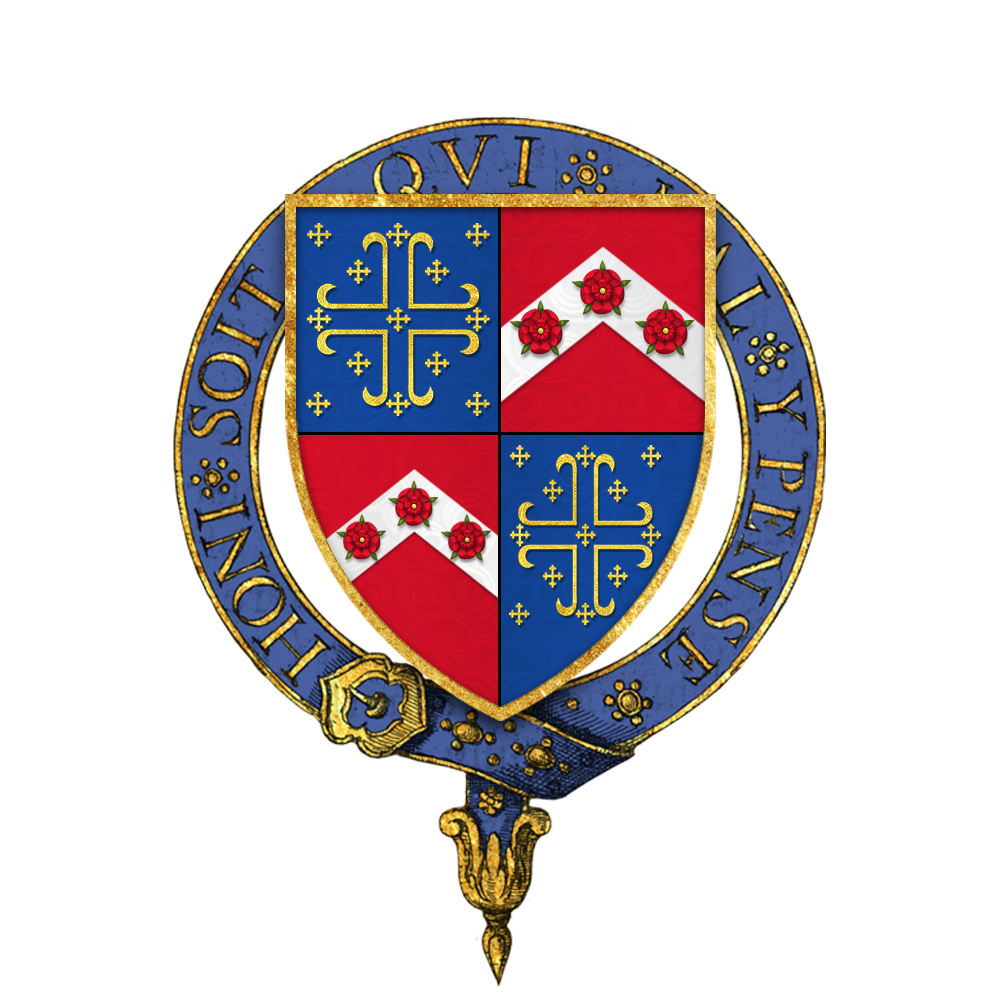

Sir Francis Knollys, KG of

Sir Francis Knollys, KG of

where he often resided by permission of the crown. The office of treasurer he retained till his death. Elizabeth was a first cousin of Knollys' wife. Although he was invariably on good terms personally with his sovereign, he never concealed his distrust of her statesmanship. Her unwillingness to take "safe counsel", her apparent readiness to encourage parasites and flatterers, whom he called "King Richard the Second's men", was, he boldly pointed out, responsible for most of her dangers and difficulties. In July 1578 he repeated his warnings in a long letter, and begged her to adopt straightforward measures so as to avert such disasters as the conquest of the

Sir Francis Knollys, KG of

Sir Francis Knollys, KG of Rotherfield Greys

Rotherfield Greys is a village and civil parish in the Chiltern Hills in South Oxfordshire. It is west of Henley-on-Thames and just over east of Rotherfield Peppard (locally known as Peppard). It is linked by a near-straight minor road to H ...

, Oxfordshire (c. 1511 / c. 1514 – 19 July 1596) was an English courtier

A courtier () is a person who attends the royal court of a monarch or other royalty. The earliest historical examples of courtiers were part of the retinues of rulers. Historically the court was the centre of government as well as the official ...

in the service of Henry VIII, Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first E ...

and Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is ...

, and was a Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

for a number of constituencies.

Early appointments

Francis Knollys was born 1511, the elder son of Sir Robert Knollys (d. 1520/1521) and Lettice Peniston (d. 1557/1558), daughter of Sir Thomas Peniston ofHawridge

Hawridge, (recorded as Hoquerug in the 12th century) is a small village in the Chilterns in the county of Buckinghamshire, England and bordering the county boundary with Hertfordshire. It is from Chesham, from both Tring and Berkhamsted. H ...

, Buckinghamshire, henchman

A henchman (''vernacular:'' "hencher"), is a loyal Employment, employee, supporter, or aide to some powerful figure engaged in nefarious or criminal enterprises. Henchmen are typically relatively unimportant in the organization: minions whose val ...

to Henry VIII.

He appears to have received some education at Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

. He married Catherine Carey, first cousin (as well as possible half-sister) of Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is ...

. Henry VIII extended to him the favour that he had shown to his father, and secured to him in fee the estate of Rotherfield Greys

Rotherfield Greys is a village and civil parish in the Chiltern Hills in South Oxfordshire. It is west of Henley-on-Thames and just over east of Rotherfield Peppard (locally known as Peppard). It is linked by a near-straight minor road to H ...

in 1538. Acts of Parliament

Acts of Parliament, sometimes referred to as primary legislation, are texts of law passed by the legislative body of a jurisdiction (often a parliament or council). In most countries with a parliamentary system of government, acts of parliament be ...

in 1540–41 and in 1545–46 attested this grant, making his wife in the second act joint tenant with him. At the same time Francis became one of the gentlemen-pensioners at court, and in 1539 attended Anne of Cleves

Anne of Cleves (german: Anna von Kleve; 1515 – 16 July 1557) was Queen of England from 6 January to 12 July 1540 as the fourth wife of King Henry VIII. Not much is known about Anne before 1527, when she became betrothed to Francis, Duke o ...

on her arrival in England. In 1542 he entered the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

for the first time as member for Horsham.

At the beginning of Edward VI's reign, he accompanied the English army to Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

, and was knighted by the commander-in-chief, the Duke of Somerset

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are rank ...

, at the camp at Roxburgh

Roxburgh () is a civil parish and formerly a royal burgh, in the historic county of Roxburghshire in the Scottish Borders, Scotland. It was an important trading burgh in High Medieval to early modern Scotland. In the Middle Ages it had at leas ...

on 28 September 1547.

Knollys' strong Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

convictions recommended him to the young king, and to his sister the Princess Elizabeth, and he spent much time at court, taking a prominent part not only in tournaments

A tournament is a competition involving at least three competitors, all participating in a sport or game. More specifically, the term may be used in either of two overlapping senses:

# One or more competitions held at a single venue and concentr ...

there, but also in religious discussion. On 25 November 1551, he was present at Sir William Cecil's house, at a conference between several Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

s and Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

s respecting the corporeal presence in the Sacrament. About the same date, he was granted the manors of Caversham in Oxfordshire (now Berkshire) and Cholsey

Cholsey is a village and civil parish south of Wallingford in South Oxfordshire. In 1974 it was transferred from Berkshire to Oxfordshire, and from Wallingford Rural District to the district of South Oxfordshire. The 2011 Census recorded Cho ...

in Berkshire (now Oxfordshire). At the end of 1552, he visited Ireland on public business.

Mary I of England and exile

The accession ofMary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

in 1553 darkened Knollys' prospects. His religious opinions placed him in opposition to the government, and he deemed it prudent to cross to Germany. On his departure the Princess Elizabeth wrote to his wife a sympathetic note, expressing a wish that they would soon be able to return in safety. Knollys first took up his residence in Frankfurt

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , " Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on it ...

, where he was admitted a church-member on 21 December 1557, but afterwards removed to Strasbourg. According to Fuller, he "bountifully communicated to the necessities" of his fellow-exiles in Germany, and at Strasburg he seems to have been on intimate terms with John Jewel

John Jewel (''alias'' Jewell) (24 May 1522 – 23 September 1571) of Devon, England was Bishop of Salisbury from 1559 to 1571.

Life

He was the youngest son of John Jewel of Bowden in the parish of Berry Narbor in Devon, by his wife Alice Bel ...

and Peter Martyr.

Before Mary's death he returned to England, and as a man "of assured understanding and truth, and well affected to the Protestant religion," he was admitted to Elizabeth's privy council in December 1558. He was soon afterwards made Vice-Chamberlain of the Household and captain of the halberdiers, while his wife – a first cousin of Elizabeth – became a woman of the queen's privy chamber. On the death of his mother in 1558 he took possession of Greys Court

Greys Court is a Tudor country house and gardens in the southern Chiltern Hills at Rotherfield Greys, near Henley-on-Thames in the county of Oxfordshire, England. Now owned by the National Trust, it is located at , and is open to the public.

...

at Rotherfield Greys and undertook a remodelling of the building in 1573–74. In 1560 Knollys' wife and son Robert were granted for their lives the manor of Taunton

Taunton () is the county town of Somerset, England, with a 2011 population of 69,570. Its thousand-year history includes a 10th-century monastic foundation, Taunton Castle, which later became a priory. The Normans built a castle owned by the ...

, part of the property of the see of Winchester

The Diocese of Winchester forms part of the Province of Canterbury of the Church of England. Founded in 676, it is one of the older dioceses in England. It once covered Wessex, many times its present size which is today most of the historic enla ...

.

Member of Parliament and other offices

In 1559 Knollys was chosen MP for Arundel and in 1562knight of the shire

Knight of the shire ( la, milites comitatus) was the formal title for a member of parliament (MP) representing a county constituency in the British House of Commons, from its origins in the medieval Parliament of England until the Redistributio ...

for Oxfordshire. He was appointed chief steward of Oxford in Feb 1564 until 1592. In 1572 he was re-elected member for Oxfordshire, and sat for that constituency until his death. The Queen granted him the manors of Littlemore

Littlemore is a district and civil parish in Oxford, England. The civil parish includes part of Rose Hill. It is about southeast of the city centre of Oxford, between Rose Hill, Blackbird Leys, Cowley, and Sandford-on-Thames. The 2011 Censu ...

and Temple Cowley. Throughout his parliamentary career he was a frequent spokesman for the government on questions of general politics, but in ecclesiastical matters he preserved as a zealous puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

an independent attitude.

Knollys' friendship with the queen and Cecil led to his employment in many state offices. In 1563 he was governor of Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

, and was much harassed in August by the difficulties of supplying the needs in men and money of the Earl of Warwick

Earl of Warwick is one of the most prestigious titles in the peerages of the United Kingdom. The title has been created four times in English history, and the name refers to Warwick Castle and the town of Warwick.

Overview

The first creation ...

, who was engaged on his disastrous expedition to Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very ...

. In April 1566 he was sent to Ireland to control the expenditure of Sir Henry Sidney

Sir Henry Sidney (20 July 1529 – 5 May 1586), Lord Deputy of Ireland, was the eldest son of Sir William Sidney of Penshurst, a prominent politician and courtier during the reigns of Henry VIII and Edward VI, from both of whom he receive ...

, the lord deputy, who was trying to repress the rebellion of Shane O'Neill, and was much hampered by the interference of court factions at home; but Knollys found himself compelled, contrary to Elizabeth's wish, to approve Sidney's plans. It was, he explained, out of the question to conduct the campaign against the Irish rebels on strictly economical lines. In August 1564 he accompanied the queen to Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a College town, university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cam ...

, and was created MA. Two years later he went to Oxford, also with his sovereign, and received a like distinction there. In the same year he was appointed treasurer of the queen's chamber and in 1570 promoted to Treasurer of the Household

The Treasurer of the Household is a member of the Royal Household of the Sovereign of the United Kingdom. The position is usually held by one of the government deputy Chief Whips in the House of Commons. The current holder of the office is Mar ...

.

Mary, Queen of Scots

In May 1568Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of S ...

fled to England, and flung herself on Elizabeth's protection. She had found refuge in Carlisle Castle, and the delicate duty of taking charge of the fugitive was entrusted jointly to Knollys and to Henry Scrope, 9th Baron Scrope of Bolton

Henry Scrope, 9th Baron Scrope of Bolton, KG (c. 1534 – 13 June 1592) was the son and heir of John Scrope, 8th Baron Scrope of Bolton and Catherine Clifford, daughter of Henry Clifford, 1st Earl of Cumberland.

Life

Henry Scrope, a loyal ...

. On 28 May Knollys arrived at the castle, and was admitted to Mary's presence. At his first interview he was conscious of Mary's powerful fascination. But to her requests for an interview with Elizabeth, and for help to regain her throne, he returned the evasive answers which Elizabeth's advisers had suggested to him, and he frankly drew her attention to the suspicions in which Darnley's murder involved her.

A month passed, and no decision was reached in London respecting Mary's future. On 13 July Knollys contrived to remove her, despite "'her tragical demonstrations", to Bolton Castle

Bolton Castle is a 14th-century castle located in Wensleydale, Yorkshire, England (). The nearby village of Castle Bolton takes its name from the castle. The castle is a Grade I listed building and a Scheduled Ancient Monument. The castle was da ...

, the seat of Lord Scrope, where he tried to amuse her by teaching her to write and speak English. Knollys's position grew more and more distasteful, and writing on 16 July to Cecil, whom he kept well informed of Mary's conversation and conduct, he angrily demanded his recall. But while lamenting his occupation, Knollys conscientiously endeavoured to convert his prisoner to his puritanic views, and she read the English prayer-book under his guidance. In his discussions with her he commended so unreservedly the doctrines and forms of Geneva

, neighboring_municipalities= Carouge, Chêne-Bougeries, Cologny, Lancy, Grand-Saconnex, Pregny-Chambésy, Vernier, Veyrier

, website = https://www.geneve.ch/

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevr ...

that Elizabeth, on learning his line of argument, sent him a sharp reprimand. Knollys, writing to Cecil in self-defence, described how contentedly Mary accepted his plain speaking on religious topics. Mary made in fact every effort to maintain good relations with him. Late in August, when Knollys was away at Seaton Delaval

Seaton Delaval is a village in Northumberland, England, with a population of 4,371. The largest of the five villages in Seaton Valley, it is the site of Seaton Delaval Hall, completed by Sir John Vanbrugh in 1727.

In 2010 the armed robbery of ...

, she sent him a present for his wife, desired his wife's acquaintance, and wrote to him a very friendly note, her first attempt in English composition. The gift was a chain of gold pomander beads strung on gold wire.

In October, when schemes for marrying Mary to an English nobleman were under consideration, Knollys proposed that his wife's nephew, George Carey, might prove a suitable match. In November the inquiry into Mary's misdeeds which had begun at York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

, was reopened at Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

, and Knollys pointed out that he needed a larger company of retainers to keep his prisoner safe from a possible attempt at rescue. In December he was directed by Elizabeth to induce Mary to assent to her abdication

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of duty, in other societ ...

of the Scottish throne. In January 1569 he plainly told Elizabeth that, in declining to allow Mary either to be condemned or to be acquitted on the charges brought against her, she was inviting perils which were likely to overwhelm her, and entreated her to leave the decision of Mary's fate to her well-tried councillors. On 20 January orders arrived at Bolton to transfer Mary to Tutbury

Tutbury is a village and civil parish in Staffordshire, England. It is north of Burton upon Trent and south of the Peak District. The village has a population of about 3,076 residents. It adjoins Hatton to the north on the Staffordshire–Derby ...

, where the Earl of Shrewsbury

Earl of Shrewsbury () is a hereditary title of nobility created twice in the Peerage of England. The second earldom dates to 1442. The holder of the Earldom of Shrewsbury also holds the title of Earl of Waterford (1446) in the Peerage of Ireland ...

was to take charge of her. Against the removal the Scottish queen protested in a pathetic note to Knollys, intended for Elizabeth's eye, but next day she was forced to leave Bolton, and Knollys remained with her at Tutbury till 3 February. His wife's death then called him home. Mary blamed Elizabeth for the fatal termination of Lady Knollys' illness, attributing it to her husband's enforced absence in the north.

Relations with Elizabeth I

In April 1571 Knollys strongly supported the retrospective clauses of the bill for the better protection of Queen Elizabeth, by which any person who had previously put forward a claim to the throne was adjudged guilty ofhigh treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

. Next year he was appointed treasurer of the royal household, and he entertained Elizabeth at Abbey House in Reading

Reading is the process of taking in the sense or meaning of letters, symbols, etc., especially by sight or touch.

For educators and researchers, reading is a multifaceted process involving such areas as word recognition, orthography (spelling ...

br>where he often resided by permission of the crown. The office of treasurer he retained till his death. Elizabeth was a first cousin of Knollys' wife. Although he was invariably on good terms personally with his sovereign, he never concealed his distrust of her statesmanship. Her unwillingness to take "safe counsel", her apparent readiness to encourage parasites and flatterers, whom he called "King Richard the Second's men", was, he boldly pointed out, responsible for most of her dangers and difficulties. In July 1578 he repeated his warnings in a long letter, and begged her to adopt straightforward measures so as to avert such disasters as the conquest of the

Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

by Spain, the revolt of Scotland to France and Mary Stuart, and the growth of papist

The words Popery (adjective Popish) and Papism (adjective Papist, also used to refer to an individual) are mainly historical pejorative words in the English language for Roman Catholicism, once frequently used by Protestants and Eastern Orthodo ...

s in England. He did not oppose the first proposals for the queen's marriage with Alençon which were made in 1579, but during the negotiations he showed reluctance to accept the scheme, and Elizabeth threatened that "his zeal for religion would cost him dear".

In December 1581 he attended the Jesuit Campion's execution, and asked him on the scaffold whether he renounced the pope. He was a commissioner for the trials of Parry the Jesuit in 1585, of Anthony Babington and his fellow-conspirators, whom he tried to argue into Protestantism, in 1586, and of Queen Mary at Fotheringay in the same year. He urged Mary's immediate execution in 1587 both in Parliament and in the council. In April 1589 he was a commissioner for the trial of Philip Howard, earl of Arundel. On 16 December 1584 he introduced into the House of Commons the bill legalising a national association to protect the queen from assassination. In 1585 he offered to contribute £100 for seven years towards the expenses of the war for the defence of the Low Countries, and renewed the offer, which was not accepted, in July 1586. In 1588–9 he was placed in command of the land forces of Hertfordshire and Cambridgeshire

Cambridgeshire (abbreviated Cambs.) is a county in the East of England, bordering Lincolnshire to the north, Norfolk to the north-east, Suffolk to the east, Essex and Hertfordshire to the south, and Bedfordshire and Northamptonshire to the ...

, which had been called together to resist the Spanish Armada. Knollys was interested in the voyages of Frobisher and Drake

Drake may refer to:

Animals

* A male duck

People and fictional characters

* Drake (surname), a list of people and fictional characters with the family name

* Drake (given name), a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* ...

, and took shares in the first and second Cathay expeditions.

Puritanism

Knollys never wavered in his consistent championship of the puritans. In May 1574 he joinedEdmund Grindal

Edmund Grindal ( 15196 July 1583) was Bishop of London, Archbishop of York, and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reign of Elizabeth I. Though born far from the centres of political and religious power, he had risen rapidly in the church durin ...

(Archbishop of York), Sir Walter Mildmay

Sir Walter Mildmay (bef. 1523 – 31 May 1589) was a statesman who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer to Queen Elizabeth I, and founded Emmanuel College, Cambridge.

Origins

He was born at Moulsham in Essex, the fourth and youngest son of ...

, and Sir Thomas Smith in a letter to John Parkhurst

John Parkhurst (c. 1512 – 2 February 1575) was an English Marian exile and from 1560 the Bishop of Norwich.

Early life

Born about 1512, he was son of George Parkhurst of Guildford, Surrey. He initially attended the Royal Grammar School, Guild ...

(Bishop of Norwich), arguing in favour of the religious exercises known as "prophesyings". But he was zealous in opposition to heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

, and in September 1581 he begged Burghley and Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester to repress such " anabaptisticall sectaries" as members of the "Family of Love", "who do serve the turn of the papists". Writing to John Whitgift (Archbishop of Canterbury), 20 June 1584, he hotly condemned the archbishop's attempts to prosecute puritan preachers in the Court of High Commission

The Court of High Commission was the supreme ecclesiastical court in England. Some of its powers was to take action against conspiracies, plays, tales, contempts, false rumors, books. It was instituted by the Crown in 1559 to enforce the Act of U ...

as unjustly despotic, and treading "the highway to the pope". He supported Cartwright with equal vehemence. On 24 May 1584 he sent to Burghley a bitter attack on "the undermining ambition and covetousness of some of our bishops", and on their persecutions of the puritans. Repeating his views in July 1586, he urged the banishment of all recusants

Recusancy (from la, recusare, translation=to refuse) was the state of those who remained loyal to the Catholic Church and refused to attend Church of England services after the English Reformation.

The 1558 Recusancy Acts passed in the reign ...

and the exclusion from public offices of all who married recusants. In 1588 he charged Whitgift with endangering the queen's safety by his popish tyranny, and embodied his accusation in a series of articles which Whitgift characterised as a fond and scandalous syllogism.

In the parliament of 1588–9 he vainly endeavoured to pass a bill against non-residence of the clergy and pluralities. In the course of the discussion he denounced the claims of the bishops "to keep courts in their own name", and denied them any "worldly pre-eminence". This speech, "related by himself" to Burghley, was published in 1608, together with a letter to Knollys from his friend, the puritan John Rainolds

John Rainolds (or Reynolds) (1549 – 21 May 1607) was an English academic and churchman, of Puritan views. He is remembered for his role in the Authorized Version of the Bible, a project of which he was initiator.

Life

He was born about M ...

, in which Bishop Bancroft's sermon at St Paul's Cross

St Paul's Cross (alternative spellings – "Powles Crosse") was a preaching cross and open-air pulpit in the grounds of Old St Paul's Cathedral, City of London. It was the most important public pulpit in Tudor and early Stuart England, and ma ...

(9 February 1588–9) was keenly criticised. The volume was entitled "Informations, or a Protestation and a Treatise from Scotland … all suggesting the Usurpation of Papal Bishops". Knollys' contribution reappeared as "Speeches used in the parliament by Sir Francis Knoles", in William Stoughton's "Assertion for True and Christian Church Policie" (London, 1642). Throughout 1589 and 1590 he was seeking, in correspondence with Burghley, to convince the latter of the impolicy of adopting Whitgift's theory of the divine right of bishops. On 9 January 1591 he told his correspondent that he marvelled "how her Majestie can be persuaded that she is in as much danger of such as are called Purytanes as she is of the Papysts". Finally, on 14 May 1591, he declared that he would prefer to retire from politics and political office rather than cease to express his hostility to the bishops' claims with full freedom.

Domestic affairs and death

Knollys' domestic affairs at times caused him anxiety. In spite of his friendly relations with the Earl of Leicester, he did not approve the royal favourite's intrigues with his daughter,Lettice Lettice is both a given name and a surname. Notable people with the name include:

Given name

*Lettice Boyle, wife of George Goring, Lord Goring

* Lettice Bryan (1805–1877), American author

*Lettice Cooper (1897–1994), English writer

* Lettice ...

, widow of Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex

Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex, KG (16 September 1541 – 22 September 1576), was an English nobleman and general. From 1573 until his death he fought in Ireland in connection with the Plantations of Ireland, most notably the Rathlin Is ...

, and he finally insisted on their marriage at Wanstead on 21 September 1578. The wayward temper of his grandson, Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex

Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, KG, PC (; 10 November 1565 – 25 February 1601) was an English nobleman and a favourite of Queen Elizabeth I. Politically ambitious, and a committed general, he was placed under house arrest following ...

(son of his daughter Lettice by her first husband), was a source of trouble to him in his later years, and the queen seemed inclined to make him responsible for the youth's vagaries. Knollys was created KG in 1593 and died on 19 July 1596. He was buried at Rotherfield Greys, and an elaborate monument, with effigies of seven sons, six daughters, and his son William's wife, still stands in the church there.

Issue

He married Catherine Carey, the daughter of Sir William Carey of Aldenham and Mary Boleyn in Hertfordshire on 26 April 1540. Sir Francis and Lady Knollys had a total of 15 children: *Mary Knollys (c. 1541 – 1593). She married Edward Stalker. *Sir Henry Knollys (c. 1542 – 1583). He was a Member of Parliament representing Shoreham, Sussex in 1562,Reading, Berkshire

Reading ( ) is a town and borough in Berkshire, Southeast England, southeast England. Located in the Thames Valley at the confluence of the rivers River Thames, Thames and River Kennet, Kennet, the Great Western Main Line railway and the M4 mot ...

(1563–1572) and then Oxfordshire. Esquire of the Body to Elizabeth I. He was married to Margaret Cave (1549–1600), daughter of Sir Ambrose Cave and Margaret Willington. Their daughter Lettice Knollys (1583–1655) married before 19 June 1602 William Paget, 4th Baron Paget

William Paget, 4th Baron Paget of Beaudesert (1572 – 29 August 1629) was an English peer and colonist born in Beaudesert House, Staffordshire, England to Thomas Paget, 3rd Baron Paget and Nazareth Newton. His grandfather was William Paget, 1st ...

.

*Lettice Knollys

Lettice Knollys ( , sometimes latinized as Laetitia, alias Lettice Devereux or Lettice Dudley), Countess of Essex and Countess of Leicester (8 November 1543Adams 2008a – 25 December 1634), was an English noblewoman and mother to the courtier ...

, Countess of Essex and of Leicester (8 November 1543 – 25 December 1634). She married first Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex

Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex, KG (16 September 1541 – 22 September 1576), was an English nobleman and general. From 1573 until his death he fought in Ireland in connection with the Plantations of Ireland, most notably the Rathlin Is ...

, secondly Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester and thirdly Sir Christopher Blount

Sir Christopher Blount (1555/1556Hammer 2008 – 18 March 1601) was an English soldier, secret agent, and rebel. He served as a leading household officer of Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester. A Catholic, Blount corresponded with Mary, Queen of ...

.

*Sir William Knollys, 1st Earl of Banbury

William Knollys, 1st Earl of Banbury, KG, PC (1544 – 25 May 1632) was an English nobleman at the court of Queen Elizabeth I and King James I.

Biography

He was the son of Sir Francis Knollys, of Greys Court in Oxfordshire, and of Readin ...

, (c. 1544 – 25 May 1632). Member of Parliament for Tregony

Tregony ( kw, Trerigoni), sometimes in the past Tregoney, is a village and former civil parish, now in the parish of Tregony with Cuby, in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It lies on the River Fal. In the village there is a post office (now ...

and Oxfordshire. He was married first to Dorothy Bray, who was 20 years his senior; and secondly to Elizabeth Howard, daughter of Thomas Howard, 1st Earl of Suffolk

Thomas Howard, 1st Earl of Suffolk, (24 August 156128 May 1626) of Audley End House in the parish of Saffron Walden in Essex, and of Suffolk House near Westminster, a member of the House of Howard, was the second son of Thomas Howard, 4th ...

and his second wife Catherine Knyvett.

*Edward Knollys

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sax ...

(1546–1580). He was a member of Parliament for Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

(1571–1575).

* Sir Robert Knollys (1547 1619 or 1626). Member of Parliament representing Reading, Berkshire

Reading ( ) is a town and borough in Berkshire, Southeast England, southeast England. Located in the Thames Valley at the confluence of the rivers River Thames, Thames and River Kennet, Kennet, the Great Western Main Line railway and the M4 mot ...

(1572–1589), Brecknockshire (1589–1604), Abingdon, Oxfordshire

Abingdon-on-Thames ( ), commonly known as Abingdon, is a historic market town and civil parish in the ceremonial county of Oxfordshire, England, on the River Thames. Historically the county town of Berkshire, since 1974 Abingdon has been admin ...

(1604, 1624–1625) and finally Berkshire again (1626). He married Catherine Vaughan, daughter of Sir Rowland Vaughan, of Porthamel.

* Richard Knollys (1548 – 21 August 1596). Member of Parliament representing first Wallingford (1584) and then Northampton (1588). Married Joan Heigham, daughter of John Heigham, of Gifford's Hall, Wickhambrook

Wickhambrook is a village and civil parish in the West Suffolk district of Suffolk in eastern England. It is about south-west from Bury St Edmunds, halfway to Haverhill, off the A143 road.

Wickhambrook is the largest village by area in the ...

, Suffolk.

* Elizabeth Knollys (15 June 1549 – c.1605). She married Sir Thomas Leighton of Feckenham

Feckenham is a village and civil parish in the Borough of Redditch in Worcestershire, England. It lies some south-west of the town of Redditch and some east of the city of Worcester. It had a population of 670 in the 2001 census and its immed ...

, Worcester

Worcester may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Worcester, England, a city and the county town of Worcestershire in England

** Worcester (UK Parliament constituency), an area represented by a Member of Parliament

* Worcester Park, London, Engla ...

, son of John Leighton of Watlesburgh and Joyce Sutton, in 1578. Her husband served as Governor of Jersey

Jersey ( , ; nrf, Jèrri, label= Jèrriais ), officially the Bailiwick of Jersey (french: Bailliage de Jersey, links=no; Jèrriais: ), is an island country and self-governing Crown Dependency near the coast of north-west France. It is the l ...

and Guernsey.

*Maud Knollys (c.1550 – 155?/6?), died young.

* Sir Francis Knollys "the Younger" (c. 1552 – 1648). Privateer and admiral and Member of Parliament representing several constituencies from 1575 to his death in 1648. He married Lettice Barrett, daughter of John Barrett, of Hanham; their daughter, Letitia, married John Hampden

John Hampden (24 June 1643) was an English landowner and politician whose opposition to arbitrary taxes imposed by Charles I made him a national figure. An ally of Parliamentarian leader John Pym, and cousin to Oliver Cromwell, he was one of t ...

.

* Anne Knollys (19 July 1555 – 30 August 1608), who married Thomas West, 2nd Baron De La Warr

Thomas West, 2nd and 11th Baron De La Warr ( ; c. 1550 – 24 March 1601/1602) of Wherwell Abbey, Hampshire, was a member of Elizabeth I's Privy Council.

Biography

Thomas West was the eldest son of William West, 1st Baron De La Warr, by his f ...

, by whom she had six sons and eight daughters, including Thomas West, 3rd Baron De La Warr

Thomas West, 3rd Baron De La Warr ( ; 9 July 1577 – 7 June 1618), was an English merchant and politician, for whom the bay, the river, and, consequently, a Native American people and U.S. state, all later called "Delaware", were named. He wa ...

, after whom the state of Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent Del ...

is named.

* Sir Thomas Knollys (1558 – 1596). Better known for service in the Eighty Years' War (1568–1648). Governor of Ostend

Ostend ( nl, Oostende, ; french: link=no, Ostende ; german: link=no, Ostende ; vls, Ostende) is a coastal city and municipality, located in the province of West Flanders in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It comprises the boroughs of Mariakerk ...

in 1586. Married Odelia de Morana, daughter of John de Morada, Marquess of Bergen.

*Catherine Knollys (21 October 1559 – 20 December 1620). Married first in October 1578Charles Mosley, editor, Burke's Peerage, Baronetage & Knightage, 107th edition, 3 Volumes (Wilmington, Delaware, U.S.A.: Burke's Peerage (Genealogical Books) Ltd, 2003), Volume 2, p. 2298. Gerald FitzGerald, Baron Offaly (son of Gerald FitzGerald, 11th Earl of Kildare

Gerald is a male Germanic given name meaning "rule of the spear" from the prefix ''ger-'' ("spear") and suffix ''-wald'' ("rule"). Variants include the English given name Jerrold, the feminine nickname Jeri and the Welsh language Gerallt and ...

and Mabel Browne

Mabel Browne, Countess of Kildare (c. 1536 – 25 August 1610) was an English courtier. She was wife of Gerald FitzGerald, 11th Earl of Kildare, Baron of Offaly (25 February 1525 – 16 November 1585). She was born into the English Roman Catholi ...

) and secondly Sir Phillip Butler, of Watton Woodhall. She was the mother of Lettice Digby, 1st Baroness Offaly

Lettice FitzGerald, 1st Baroness Offaly (c. 1580 – 1 December 1658) was an Irish noblewoman and a member of the FitzGerald dynasty. Although she became heiress-general to the Earls of Kildare on the death of her father, the title instead ...

.

*Cecily Knollys (c. 1560 - ?). No known descendants.

*Margaret Knollys. No known descendants.

*Dudley Knollys (1562 - 156?/157?), died young.

See also

*Knollys (family)

Knollys, Knolles or Knowles (), the name of an English family descended from Sir Thomas Knollys (died 1435), Lord Mayor of London, possibly a kinsman of the celebrated general Sir Robert Knolles. The next distinguished member of the family was S ...

Notes

References

* * *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Knollys, Francis (The Elder) Francis English civil servants English courtiers 1514 births 1596 deaths People of the Elizabethan era Esquires of the Body Knights of the Garter Lord-Lieutenants of Berkshire Members of the pre-1707 English Parliament for constituencies in Cornwall People from Reading, Berkshire People from Rotherfield Greys English MPs 1529–1536 English MPs 1545–1547 English MPs 1547–1552 English MPs 1559 English MPs 1563–1567 English MPs 1571 English MPs 1572–1583 English MPs 1584–1585 English MPs 1586–1587 English MPs 1589 English MPs 1593 Knights Bachelor Court of Henry VIII Court of Elizabeth I