Frances Willard on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Frances Elizabeth Caroline Willard (September 28, 1839 – February 17, 1898) was an

Willard was born in 1839 to Josiah Flint Willard and Mary Thompson Hill Willard in Churchville, near

Willard was born in 1839 to Josiah Flint Willard and Mary Thompson Hill Willard in Churchville, near

After her resignation, Willard focused her energies on a new career: the women's

After her resignation, Willard focused her energies on a new career: the women's

Willard died quietly in her sleep at the Empire Hotel in

Willard died quietly in her sleep at the Empire Hotel in

The famous painting, ''American Woman and her Political Peers'', commissioned by Henrietta Briggs-Wall for the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition, features Frances Willard at the center, surrounded by a convict, American Indian, lunatic, and an idiot. The image succinctly portrayed one argument for female enfranchisement: without the right to vote, the educated, respectable woman was equated with the other outcasts of society to whom the franchise was denied.

After her death, Willard was the first woman included among America's greatest leaders in Statuary Hall in the

The famous painting, ''American Woman and her Political Peers'', commissioned by Henrietta Briggs-Wall for the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition, features Frances Willard at the center, surrounded by a convict, American Indian, lunatic, and an idiot. The image succinctly portrayed one argument for female enfranchisement: without the right to vote, the educated, respectable woman was equated with the other outcasts of society to whom the franchise was denied.

After her death, Willard was the first woman included among America's greatest leaders in Statuary Hall in the

Woman and Temperance, or the Work and Workers of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union

'' Hartford, Conn: Park Pub. Co., 1883. *

How to Win: A Book For Girls

'. NY: Funk & Wagnalls, 1886. reprinted 1887 & 1888. *

Nineteen Beautiful Years, or, Sketches of a Girl's Life

'' Chicago: Woman's Temperance Publication Association, 1886. *

Glimpses of Fifty Years: the Autobiography of an American Woman

'' Chicago: Woman's Temperance Publishing Association, 1889. *

A Classic Town: The Story of Evanston

'' Woman's Temperance Publishing Association, Chicago, 1891. *

President's Annual Address

'' 1891, Woman's Christian Temperance Union. * ''

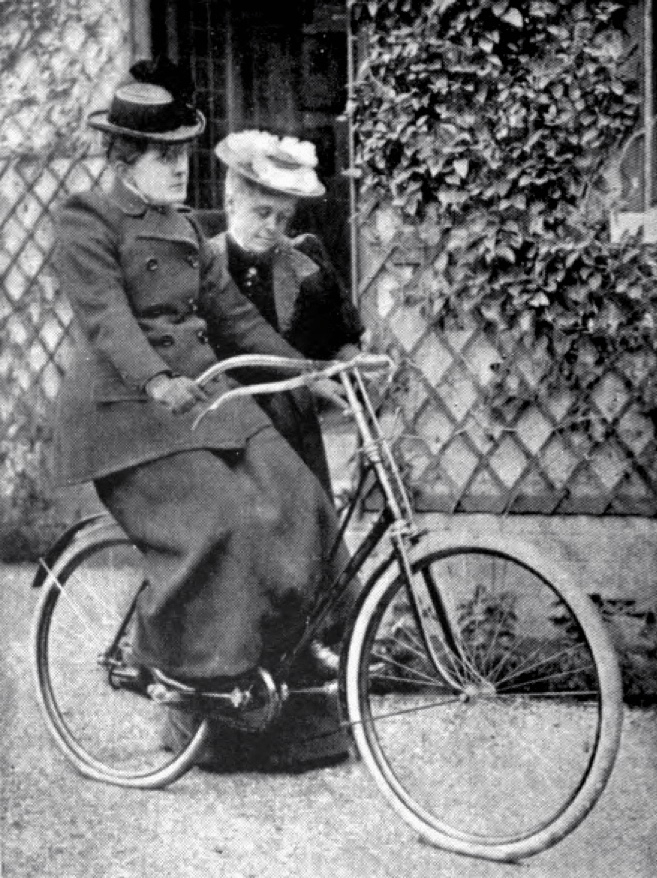

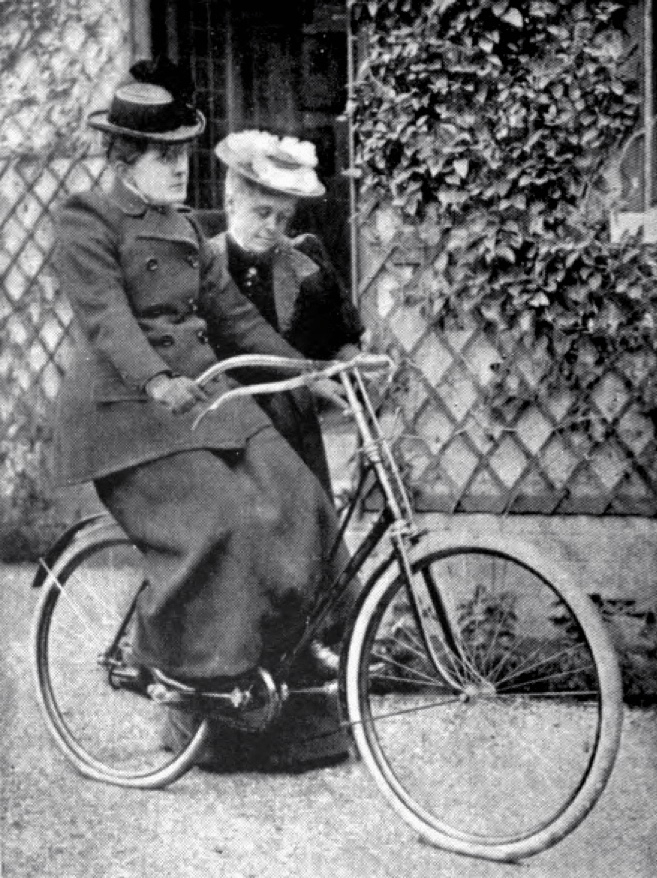

A Wheel Within a Wheel: How I Learned to Ride the Bicycle

'' 1895. *

Do Everything: a Handbook for the World's White Ribboners

'' Chicago: Woman's Temperance Publishing Association, 895? *

Book online

* William M. Thayer, ''Women who win'', 1896 s. 341–369 (355–383

Book online

Correspondence and images of Frances Willard

from Kansas Memory, the digital portal of the Kansas historical Society.

Frances E. Willard Papers, Northwestern University Archives, Evanston, IllinoisFrances E. Willard Journal Transcriptions, Northwestern University Archives, Evanston, Illinois

Frances Willard House

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Willard, Frances 1839 births 1898 deaths American suffragists American temperance activists Methodists from Wisconsin American Christian socialists American Congregationalists Burials at Rosehill Cemetery Northwestern University faculty Writers from Evanston, Illinois People from Janesville, Wisconsin LGBT feminists American LGBT writers American rhetoricians American socialist feminists Writers from Wisconsin 19th-century Methodists Writers from New York (state) Milwaukee-Downer College alumni Hall of Fame for Great Americans inductees Woman's Christian Temperance Union people Methodist socialists Deans of women Female Christian socialists Deaths from influenza Wikipedia articles incorporating text from A Woman of the Century Proponents of Christian feminism �

American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

educator, temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

* Temperance (group), Canadian dan ...

reformer, and women's suffragist. Willard became the national president of Woman's Christian Temperance Union

The Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) is an international temperance organization, originating among women in the United States Prohibition movement. It was among the first organizations of women devoted to social reform with a program th ...

(WCTU) in 1879 and remained president until her death in 1898. Her influence continued in the next decades, as the Eighteenth (on Prohibition) and Nineteenth (on women's suffrage) Amendments to the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the natio ...

were adopted. Willard developed the slogan "Do Everything" for the WCTU and encouraged members to engage in a broad array of social reforms by lobbying, petitioning, preaching, publishing, and education. During her lifetime, Willard succeeded in raising the age of consent

The age of consent is the age at which a person is considered to be legally competent to consent to sexual acts. Consequently, an adult who engages in sexual activity with a person younger than the age of consent is unable to legally cla ...

in many states as well as passing labor reforms including the eight-hour work day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses.

An eight-hour work day has its origins in the 1 ...

. Her vision also encompassed prison reform, scientific temperance instruction, Christian socialism

Christian socialism is a religious and political philosophy that blends Christianity and socialism, endorsing left-wing politics and socialist economics on the basis of the Bible and the teachings of Jesus. Many Christian socialists believe capi ...

, and the global expansion of women's rights.

Early life and education

Willard was born in 1839 to Josiah Flint Willard and Mary Thompson Hill Willard in Churchville, near

Willard was born in 1839 to Josiah Flint Willard and Mary Thompson Hill Willard in Churchville, near Rochester, New York

Rochester () is a City (New York), city in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York, the county seat, seat of Monroe County, New York, Monroe County, and the fourth-most populous in the state after New York City, Buffalo, New York, Buffalo, ...

. She was named after English novelist Frances (Fanny) Burney, the American poet Frances Osgood, and her sister, Elizabeth Caroline, who had died the previous year. She had two other siblings: her older brother, Oliver, and her younger sister, Mary. Her father was a farmer, naturalist, and legislator. Her mother was a schoolteacher. In 1841 the family moved to Oberlin, Ohio

Oberlin is a city in Lorain County, Ohio, United States, 31 miles southwest of Cleveland. Oberlin is the home of Oberlin College, a liberal arts college and music conservatory with approximately 3,000 students.

The town is the birthplace of th ...

, where, at Oberlin College

Oberlin College is a private liberal arts college and conservatory of music in Oberlin, Ohio. It is the oldest coeducational liberal arts college in the United States and the second oldest continuously operating coeducational institute of highe ...

Josiah Willard studied for the ministry, and Mary Hill Willard took classes. They moved to Janesville, Wisconsin

Janesville is a city in Rock County, Wisconsin, United States. It is the county seat and largest city in the county. It is a principal municipality of the Janesville, Wisconsin, Metropolitan Statistical Area and is included in the Madison–Jan ...

in 1846 for Josiah Willard's health. In Wisconsin, the family, formerly Congregationalists

Congregational churches (also Congregationalist churches or Congregationalism) are Protestant churches in the Calvinist tradition practising congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs i ...

, became Methodists. Frances and her sister Mary attended Milwaukee Normal Institute, where their mother's sister taught.

In 1858, the Willard family moved to Evanston, Illinois

Evanston ( ) is a city, suburb of Chicago. Located in Cook County, Illinois, United States, it is situated on the North Shore along Lake Michigan. Evanston is north of Downtown Chicago, bordered by Chicago to the south, Skokie to the west, ...

, and Josiah Willard became a banker. Frances and Mary attended the North Western Female College (no affiliation with Northwestern University

Northwestern University is a private research university in Evanston, Illinois. Founded in 1851, Northwestern is the oldest chartered university in Illinois and is ranked among the most prestigious academic institutions in the world.

Charte ...

) and their brother Oliver attended the Garrett Biblical Institute.

Teaching career

After graduating from North Western Female College, Willard held various teaching positions throughout the country. She worked at the Pittsburgh Female College, and, aspreceptress

A preceptor (from Latin, "''praecepto''") is a teacher responsible for upholding a ''precept'', meaning a certain law or tradition.

Buddhist monastic orders

Senior Buddhist monks can become the preceptors for newly ordained monks. In the Buddhi ...

at the Genesee Wesleyan Seminary The Genesee Wesleyan Seminary was the name of two institutions located on the same site in Lima, New York.

The Genesee Wesleyan Seminary (I) was founded in 1831 by the Genesee Annual Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church. The plan for its ...

in New York (later Syracuse University

Syracuse University (informally 'Cuse or SU) is a Private university, private research university in Syracuse, New York. Established in 1870 with roots in the Methodist Episcopal Church, the university has been nonsectarian since 1920. Locate ...

). She was appointed president of the newly founded Evanston College for Ladies in 1871. When the Evanston College for Ladies became the Woman's College of Northwestern University

Northwestern University is a private research university in Evanston, Illinois. Founded in 1851, Northwestern is the oldest chartered university in Illinois and is ranked among the most prestigious academic institutions in the world.

Charte ...

in 1873, Willard was named the first Dean of Women at the university. However, that position was to be short-lived with her resignation in 1874 after confrontations with the University President, Charles Henry Fowler

Charles Henry Fowler (August 11, 1837 – March 20, 1908) was a Canadian- American bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church (elected in 1884) and President of Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois from 1872 to 1876.

Early life

Charle ...

, over her governance of the Woman's College. Willard had previously been engaged to Fowler and had broken off the engagement.

Activist (WCTU and suffrage)

After her resignation, Willard focused her energies on a new career: the women's

After her resignation, Willard focused her energies on a new career: the women's temperance movement

The temperance movement is a social movement promoting temperance or complete abstinence from consumption of alcoholic beverages. Participants in the movement typically criticize alcohol intoxication or promote teetotalism, and its leaders emph ...

. In 1874, Willard participated in the founding convention of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union

The Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) is an international temperance organization, originating among women in the United States Prohibition movement. It was among the first organizations of women devoted to social reform with a program th ...

(WCTU) where she was elected the first Corresponding Secretary. In 1876, she became head of the WCTU Publications Department, focusing on publishing and building a national audience for the WCTU's weekly newspaper, ''The Union Signal

''The Union Signal'' (formerly, ''The Woman's Temperance Union'', ''Our Union'') is a defunct American newspaper, established in 1883 in Chicago, Illinois. Focused on temperance, it was the organ of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), ...

''. In 1885 Willard joined with Elizabeth Boynton Harbert, Mary Ellen West, Frances Conant, Mary Crowell Van Benschoten (Willard's first secretary) and 43 others to found the Illinois Woman's Press Association The Illinois Woman's Press Association (IWPA) is an Illinois-based organization of professional women and men pursuing careers across the communications spectrum. It was founded in 1885 by a group of 47 women who saw a need for communication and sup ...

.

In 1879, she sought and successfully obtained presidency of the National WCTU. Once elected, she held the post until her death. Her tireless efforts for the temperance cause included a 50-day speaking tour in 1874, an average of 30,000 miles of travel a year, and an average of 400 lectures a year for a 10-year period, mostly with the assistance of her personal secretary, Anna Adams Gordon

Anna Adams Gordon (1853–1931) was an American social reformer, songwriter, and, as national president of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union when the Eighteenth Amendment was adopted, a major figure in the Temperance movement.

Biography

...

.

Meanwhile, Willard sought to expand WCTU membership in the South, and met Varina Davis

Varina Anne Banks Howell Davis (May 7, 1826 – October 16, 1906) was the only First Lady of the Confederate States of America, and the longtime second wife of President Jefferson Davis. She moved to a house in Richmond, Virginia, in mid- ...

, the wife of former Confederate President Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as ...

, who was secretary of the local chapter of the Women's Christian Association in Memphis (where one daughter lived). Willard had tried and failed to convince Lucy Hayes

Lucy Ware Hayes (née Webb; August 28, 1831 – June 25, 1889) was the wife of President Rutherford B. Hayes and served as first lady of the United States from 1877 to 1881.

Hayes was the first First Lady to have a college degree. She was als ...

(wife of President Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governo ...

) to assist the temperance cause, but writer Sallie F. Chapin, a former Confederate sympathizer who had published a temperance novel, supported Willard and was a friend of the Davises. In 1887, Davis invited Willard to her home to discuss the future of her unmarried daughter Winnie Davis, but both Davis women declined to become public supporters, in part because Jefferson Davis opposed legal prohibition. In 1887, Texas held a referendum on temperance, in part because former Confederate postmaster John Reagan supported temperance laws. When newspapers published a photograph of Willard handing Jefferson Davis a temperance button to give to his wife, Jefferson Davis publicly came out against the referendum (as contrary to states' rights) and it lost. Although Varina Davis and Willard would continue to correspond over the next decade (as Varina moved to New York after her husband's death, and Willard spent most of her last decade abroad); another temperance referendum would not occur for two decades.

As president of the WCTU

The Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) is an international temperance organization, originating among women in the United States Prohibition movement. It was among the first organizations of women devoted to social reform with a program th ...

, Willard also argued for female suffrage, based on "Home Protection," which she described as "the movement … the object of which is to secure for all women above the age of twenty-one years the ballot as one means for the protection of their homes from the devastation caused by the legalized traffic in strong drink." The "devastation" referred to violent acts against women committed by intoxicated men, which was common both in and outside the home. Willard argued that it was too easy for men to get away with their crimes without women's suffrage. The "Home Protection" argument was used to garner the support of the "average woman," who was told to be suspicious of female suffragists by the patriarchal press, religious authorities, and society as a whole.Frances Willard, "Speech At Queen's Hall, London," June 9, 1894, in Citizen and Home Guard, July 23, 1894, WCTU series, roll 41, frame 27. Reprinted as "The Average Woman," in Slagell, "Good Woman Speaking Well," 619-625. The desire for home protection gave the average woman a socially appropriate avenue to seek enfranchisement. Willard insisted that women must forgo the notions that they were the "weaker" sex and that they must embrace their natural dependence on men. She encouraged women to join the movement to improve society: "Politics is the place for woman." The goal of the suffrage movement for Willard was to construct an "ideal of womanhood" that allowed women to fulfill their potential as the companions and counselors of men, as opposed to the "incumbrance and toy of man."

Willard's suffrage argument also hinged on her feminist interpretation of Scripture

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual pra ...

. She claimed that natural and divine laws called for equality in the American household, with the mother and father sharing leadership. She expanded this notion of the home, arguing that men and women should lead side by side in matters of education, church, and government, just as "God sets male and female side by side throughout his realm of law."

Willard's work took to an international scale in 1883 with the circulation of the Polyglot Petition against the international drug trade. She also joined May Wright Sewall

May Wright Sewall (May 27, 1844 – July 22, 1920) was an American reformer, who was known for her service to the causes of education, women's rights, and world peace. She was born in Greenfield, Milwaukee County, Wisconsin. Sewall served as cha ...

at the International Council of Women meeting in Washington, DC

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morg ...

, laying the permanent foundation for the National Council of Women of the United States

The National Council of Women of the United States (NCW/US) is the oldest nonsectarian organization of women in America. Officially founded in 1888, the NCW/US is an accredited non-governmental organization (NGO) with the Department of Public I ...

. She became the organization's first president in 1888 and continued in that post until 1890. Willard also founded the World WCTU in 1888 and became its president in 1893. She collaborated closely with Lady Isabel Somerset, president of the British Women's Temperance Association, whom she visited several times in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

.

In 1892 she took part in the St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

convention during the formation of the People's (or Populist) Party. The convention was brought a set of principles that was drafted in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

, by her and twenty-eight of the United States' leading reformers, whom had assembled at her invitation. However, the new party refused to endorse women's suffrage or temperance because it wanted to focus on economic issues.

After 1893, Willard was influenced by the British Fabian Society

The Fabian Society is a British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in democracies, rather than by revolutionary overthrow. T ...

and became a committed Christian socialist

Christian socialism is a religious and political philosophy that blends Christianity and socialism, endorsing left-wing politics and socialist economics on the basis of the Bible and the teachings of Jesus. Many Christian socialists believe cap ...

.

Death and legacy

Willard died quietly in her sleep at the Empire Hotel in

Willard died quietly in her sleep at the Empire Hotel in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

after contracting influenza

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptom ...

while she was preparing to set sail for England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

. She is buried at Rosehill Cemetery

Rosehill Cemetery (founded 1859) is an American garden cemetery on the North Side of Chicago, Illinois, and at , is the largest cemetery in the City of Chicago. According to legend, the name "Rosehill" resulted from a City Clerk's error – the a ...

, Chicago, Illinois. She bequeathed her Evanston home to the WCTU. The Frances Willard House was opened as a museum in 1900 when it also became the headquarters for the WCTU. In 1965 it was elevated to the status of National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places liste ...

.

Willard Hall in Temperance Temple, Chicago, was named in her honor.

In 1911, the Willard Hall and Willard Guest House in Wakefield Street, Adelaide, South Australia

Adelaide ( ) is the capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater Adelaide (including the Adelaide Hills) or the Adelaide city centre. The demo ...

were opened by the South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a States and territories of Australia, state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest o ...

n branch of the WCTU.

Memorials and portrayals

United States Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called The Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the seat of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, which is formally known as the United States Congress. It is located on Capitol Hill ...

. Her statue was designed by Helen Farnsworth Mears

Helen Farnsworth Mears (; December 21, 1872 – February 17, 1916) was an American sculptor.

Early years

Mears was born December 21, 1872, in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, daughter of John Hall Mears and Elizabeth Farnsworth Mears (pen names "Nellie Wild ...

and was unveiled in 1905.

The ''Frances Elizabeth Willard'' relief by Lorado Taft

Lorado Zadok Taft (April 29, 1860, in Elmwood, Illinois – October 30, 1936, in Chicago) was an American sculptor, writer and educator. His 1903 book, ''The History of American Sculpture,'' was the first survey of the subject and stood for deca ...

and commissioned by the National Woman's Christian Temperance Union

The Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) is an international temperance organization, originating among women in the United States Prohibition movement. It was among the first organizations of women devoted to social reform with a program th ...

in 1929 is in the Indiana Statehouse

The Indiana Statehouse is the state capitol building of the U.S. state of Indiana. It houses the Indiana General Assembly, the office of the Governor of Indiana, the Indiana Supreme Court, and other state officials. The Statehouse is located in ...

, Indianapolis, Indiana

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Mar ...

. The plaque commemorates the fiftieth anniversary of Willard's election as president of the WCTU on October 31, 1879: "In honor of one who made the world wider for women and more homelike for humanity Frances Elizabeth Willard Intrepid Pathfinder and beloved leader of the National and World's Woman's Christian Temperance Union."

Frances E. Willard elementary school. Evanston, Il.

The Frances Willard House Museum and Archives is located in Evanston, Illinois.

A dormitory at Northwestern University, Willard Residential College, opened in 1938 as a female dormitory and became the university's first undergraduate co-ed housing in 1970.

The Frances E. Willard School in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

was added to the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic ...

in 1987.

The Frances Willard Schoolhouse

The Frances Willard Schoolhouse is a one-room schoolhouse built in 1853 in Janesville, Wisconsin. Prominent women's suffragist and social reformer Frances Willard studied and taught there. In 1977 the school was added to the National Register of ...

in Janesville, Wisconsin was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1977.

Willard Middle School

The Berkeley Unified School District (BUSD) is the public school district for the city of Berkeley, California, United States. The district is managed by the Superintendent of Schools, and governed by the Berkeley Board of Education, whose membe ...

, established in Berkeley, California

Berkeley ( ) is a city on the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay in northern Alameda County, California, United States. It is named after the 18th-century Irish bishop and philosopher George Berkeley. It borders the cities of Oakland and E ...

in 1916, was named in her honor. Willard Park, also in Berkeley and adjacent to the middle school, was dedicated to Frances Willard in 1982.

Frances Willard Elementary School is a public school in Scranton, Pennsylvania.https://willard.scrsd.org/

Frances Willard Avenue in Chico, California

Chico ( ; Spanish for "little") is the most populous city in Butte County, California. Located in the Sacramento Valley region of Northern California, the city had a population of 101,475 in the 2020 census, reflecting an increase from 86,18 ...

is named in her honor. She was a guest of John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

and Annie Bidwell

Annie Kennedy Bidwell (June 30, 1839 – March 9, 1918) was a 19th-century pioneer and founder of society in the Sacramento Valley area of California. She is known for her contributions to social causes, such as women's suffrage, the temperance ...

, the town founders and fellow leaders in the prohibitionist movement. The avenue is adjacent to the Bidwell Mansion

Bidwell Mansion, located at 525 Esplanade in Chico, California, was the home of General John Bidwell and Annie Bidwell from late 1868 until 1900, when Gen. Bidwell died. Annie continued to live there until her death in 1918. John Bidwell began ...

.

The Frances E. Willard Temperance Hospital operated under that name from 1929 to 1936 in Chicago. It is now Loretto Hospital.

There's a small memorial at Richardson Beach in Kingston, Ontario, Canada put there by the Kingston Woman's Christian Temperance Union on Sept. 28, 1939.

Willard appears as one of two main female protagonist

A protagonist () is the main character of a story. The protagonist makes key decisions that affect the plot, primarily influencing the story and propelling it forward, and is often the character who faces the most significant obstacles. If a st ...

s in the young adult novel '' Bicycle Madness'' by Jane Kurtz.

FEW Spirits, a distillery located in Evanston, Illinois, uses Willard's initials as its name.

In 2000, Willard was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame

The National Women's Hall of Fame (NWHF) is an American institution incorporated in 1969 by a group of men and women in Seneca Falls, New York, although it did not induct its first enshrinees until 1973. As of 2021, it had 303 inductees.

Induc ...

.

Relationships

The loves of women for each other grow more numerous each day, and I have pondered much why these things were. That so little should be said about them surprises me, for they are everywhere.... In these days when any capable and careful woman can honorably earn her own support, there is no village that has not its examples of 'two hearts in counsel,' both of which are feminine.Contemporary accounts described Willard's friendships and her pattern of long-term domestic assistance from women. She formed the strongest friendships with co-workers. It is difficult to redefine Willard's 19th-century life in terms of the culture and norms of later centuries, but some scholars describe her inclinations and actions as aligned with same-sex emotional alliance (what historian Judith M. Bennett calls "lesbian-like").

Frances Willard, ''The Autobiography of an American Woman: Glimpses of Fifty Years'', 1889

Controversy over civil rights issues

In the 1890s, Willard came into conflict with African-American journalist and anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells. While trying to expose the evils of alcohol, Willard and other temperance reformers often depicted one of the evils as its effect to incite purported black criminality, thus implying that this was one of the serious problems requiring an urgent cure. The rift first surfaced during Wells' speaking tour of Britain in 1893, where Willard was also touring and was already a popular reformist speaker. Wells openly questioned Willard's silence onlynching in the United States

Lynching was the widespread occurrence of extrajudicial killings which began in the United States' pre–Civil War South in the 1830s and ended during the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s. Although the victims of lynchings were ...

and accused Willard of having pandered to the racist myth that white women were in constant danger of rape from drunken black males to avoid endangering WCTU efforts in the South. She recounted a time when Willard had visited the South and blamed the failure of the temperance movement there on the population: "The colored race multiplies like the locusts of Egypt," and "the grog

Grog is a term used for a variety of alcoholic beverages.

The word originally referred to rum diluted with water (and later on long sea voyages, also added the juice of limes or lemons), which British Vice-Admiral Edward Vernon introduced ...

shop is its center of power.... The safety of women, of childhood, of the home is menaced in a thousand localities."

Willard repeatedly denied Wells' accusations and wrote that "the attitude of the society CTUtoward the barbarity of lynching has been more pronounced than that of any other association in the United States,""About Southern Lynchings," Baltimore Herald, 20 October 1895 (Temperance and Prohibition Papers microfilm (1977), section III, reel 42, scrapbook 70, frame 153). and she maintained that her primary focus was upon empowering and protecting women, including the many African-American members of the WCTU. While it is true that neither Willard nor the WCTU had ever spoken out directly against lynching, the WCTU actively recruited black women and included them in its membership.

After their acrimonious exchange, Willard explicitly stated her opposition to lynching and successfully urged the WCTU to pass a resolution against lynching. She, however, continued to use the rhetoric that Wells alleged incited lynching. In her pamphlets ''Southern Horrors'' and ''The Red Record'', Wells linked rhetoric portraying white women as symbols of innocence and purity that black men could not resist, as facilitating lynchings.

Wells also believed that Willard condoned segregation by permitting the practice within WCTU's southern chapters. Under Willard's presidency, the national WCTU maintained a policy of "states rights" which allowed southern charters to be more conservative than their northern counterparts regarding questions of race and the role of women in politics.

Publications

*Woman and Temperance, or the Work and Workers of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union

'' Hartford, Conn: Park Pub. Co., 1883. *

How to Win: A Book For Girls

'. NY: Funk & Wagnalls, 1886. reprinted 1887 & 1888. *

Nineteen Beautiful Years, or, Sketches of a Girl's Life

'' Chicago: Woman's Temperance Publication Association, 1886. *

Glimpses of Fifty Years: the Autobiography of an American Woman

'' Chicago: Woman's Temperance Publishing Association, 1889. *

A Classic Town: The Story of Evanston

'' Woman's Temperance Publishing Association, Chicago, 1891. *

President's Annual Address

'' 1891, Woman's Christian Temperance Union. * ''

A Woman of the Century

A, or a, is the first letter and the first vowel of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''a'' (pronounced ), plural ''aes' ...

'' (1893) (ed. Willard, Frances E. & Livermore, Mary A.) - available online at Wikisource

Wikisource is an online digital library of free-content textual sources on a wiki, operated by the Wikimedia Foundation. Wikisource is the name of the project as a whole and the name for each instance of that project (each instance usually re ...

.

* A Wheel Within a Wheel: How I Learned to Ride the Bicycle

'' 1895. *

Do Everything: a Handbook for the World's White Ribboners

'' Chicago: Woman's Temperance Publishing Association, 895? *

See also

*List of civil rights leaders

Civil rights leaders are influential figures in the promotion and implementation of political freedom and the expansion of personal civil liberties and rights. They work to protect individuals and groups from political repressio ...

* List of suffragists and suffragettes

This list of suffragists and suffragettes includes noted individuals active in the worldwide women's suffrage movement who have campaigned or strongly advocated for women's suffrage, the organisations which they formed or joined, and the public ...

* List of women's rights activists

This article is a list of notable women's rights activists, arranged alphabetically by modern country names and by the names of the persons listed.

Afghanistan

* Amina Azimi – disabled women's rights advocate

* Hasina Jalal – women's empower ...

* Timeline of women's suffrage

Women's suffrage – the right of women to vote – has been achieved at various times in countries throughout the world. In many nations, women's suffrage was granted before universal suffrage, so women and men from certain classes or races w ...

Sources

References

* Baker, Jean H. ''Sisters: The Lives of America's Suffragists'' Hill and Wang, New York, 2005 . * Gordon, Anna Adams ''The Beautiful Life of Frances E. Willard'', Chicago, 1898 * McCorkindale, Isabel ''Frances E. Willard centenary book'' (Adelaide, 1939) Woman's Christian Temperance Union of Australia, 2nd ed. * Strachey, Ray '' Frances Willard, her life and work - with an introduction by Lady Henry Somerset'', New York, Fleming H. Revell (1913)Further reading

*Anna Adams Gordon, ''The beautiful life of Frances Elizabeth Willard'', 189Book online

* William M. Thayer, ''Women who win'', 1896 s. 341–369 (355–383

Book online

Primary sources

* ''Let Something Good Be Said: Speeches and Writings of Frances E. Willard,'' ed. by Carolyn De Swarte Gifford and Amy R. Slagell,University of Illinois Press

The University of Illinois Press (UIP) is an American university press and is part of the University of Illinois system. Founded in 1918, the press publishes some 120 new books each year, plus 33 scholarly journals, and several electronic proje ...

, 2007 .

Correspondence and images of Frances Willard

from Kansas Memory, the digital portal of the Kansas historical Society.

External links

Frances Willard House

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Willard, Frances 1839 births 1898 deaths American suffragists American temperance activists Methodists from Wisconsin American Christian socialists American Congregationalists Burials at Rosehill Cemetery Northwestern University faculty Writers from Evanston, Illinois People from Janesville, Wisconsin LGBT feminists American LGBT writers American rhetoricians American socialist feminists Writers from Wisconsin 19th-century Methodists Writers from New York (state) Milwaukee-Downer College alumni Hall of Fame for Great Americans inductees Woman's Christian Temperance Union people Methodist socialists Deans of women Female Christian socialists Deaths from influenza Wikipedia articles incorporating text from A Woman of the Century Proponents of Christian feminism �