France–Asia relations span a period of more than two millennia, starting in the 6th century

BCE

Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE) are year notations for the Gregorian calendar (and its predecessor, the Julian calendar), the world's most widely used calendar era. Common Era and Before the Common Era are alternatives to the or ...

with the establishment of

Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Fra ...

by Greeks from

Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, and continuing in the 3rd century BCE with Gaulish invasions of Asia Minor to form the kingdom of

Galatia, and Frankish Crusaders forming the

Crusader states. Since these early interactions, France has had a rich history of contacts with the Asian continent.

Antiquity

The

Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

ns had an early presence around

Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Fra ...

in southern France. Phoenician inscriptions have been found there.

The oldest city of France, Marseille, was formally founded in 600 BCE by Greeks from the

Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

city of

Phocaea

Phocaea or Phokaia (Ancient Greek: Φώκαια, ''Phókaia''; modern-day Foça in Turkey) was an ancient Ionian Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia. Greek colonists from Phocaea founded the colony of Massalia (modern-day Marseille, in ...

(as mentioned by

Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His '' History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of " scienti ...

Book 1, 13,

Strabo,

Athenaeus

Athenaeus of Naucratis (; grc, Ἀθήναιος ὁ Nαυκρατίτης or Nαυκράτιος, ''Athēnaios Naukratitēs'' or ''Naukratios''; la, Athenaeus Naucratita) was a Greek rhetorician and grammarian, flourishing about the end of th ...

and

Justin

Justin may refer to: People

* Justin (name), including a list of persons with the given name Justin

* Justin (historian), a Latin historian who lived under the Roman Empire

* Justin I (c. 450–527), or ''Flavius Iustinius Augustus'', Eastern Rom ...

) as a trading port under the name Μασσαλία (''Massalia'').

''The Cambridge ancient history'' p. 754

''A history of ancient Greece'' Claude Orrieux p. 62 These eastern Greeks, established on the shores of southern France, were in close relations with the

Celts, Celtic inhabitants of France, and Greek influence and artifacts penetrated northwards along the

Rhône

The Rhône ( , ; wae, Rotten ; frp, Rôno ; oc, Ròse ) is a major river in France and Switzerland, rising in the Alps and flowing west and south through Lake Geneva and southeastern France before discharging into the Mediterranean Sea. At Ar ...

valley.

The site of

Vix

VIX is the ticker symbol and the popular name for the Chicago Board Options Exchange's CBOE Volatility Index, a popular measure of the stock market's expectation of volatility based on S&P 500 index options. It is calculated and disseminated ...

in northern

Burgundy became an active trading center between Greeks and natives, attested by the discovery of Greek artifacts of the period.

The mother city of Phocaea would ultimately be destroyed by the

Persians

The Persians are an Iranian ethnic group who comprise over half of the population of Iran. They share a common cultural system and are native speakers of the Persian language as well as of the languages that are closely related to Persian.

...

in 545 BCE, further reinforcing the exodus of the Phocaeans to their settlements of the Western Mediterranean. Populations intermixed, becoming half-Greek and half-indigenous.

Trading links were extensive, in iron, spices, wheat and slaves, and with

tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn (from la, stannum) and atomic number 50. Tin is a silvery-coloured metal.

Tin is soft enough to be cut with little force and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, t ...

being imported to Marseille overland from

Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

. The Greek settlements permitted cultural interaction between the Greeks and the Celts, and in particular helped develop an urban way of life in Celtic lands, contacts with sophisticated Greek methods, as well as regular East-West trade.

Overland trade with Celtic countries declined around 500 however, with the troubles following the end of the

Halstatt civilization.

Because of demographic pressure, the

Senones

The Senones or Senonii (Gaulish: "the ancient ones") were an ancient Gallic tribe dwelling in the Seine basin, around present-day Sens, during the Iron Age and the Roman period.

Part of the Senones settled in the Italian peninsula, where they ...

Gauls

The Gauls ( la, Galli; grc, Γαλάται, ''Galátai'') were a group of Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age and the Roman period (roughly 5th century BC to 5th century AD). Their homeland was known as Gaul (''Gallia''). They s ...

departed from Central France under

Brennus

Brennus or Brennos is the name of two Gaulish chieftains, famous in ancient history:

* Brennus, chieftain of the Senones, a Gallic tribe originating from the modern areas of France known as Seine-et-Marne, Loiret, and Yonne; in 387 BC, in t ...

to sack Rome in the

Battle of the Allia

The Battle of the Allia was a battle fought between the Senones – a Gallic tribe led by Brennus, who had invaded Northern Italy – and the Roman Republic. The battle was fought at the confluence of the Tiber and Allia rivers, 11 Roman ...

c. 390 BCE. Expansion continued eastward, into the

Aegean world, with a huge migration of Eastern Gauls appearing in

Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

, north of Greece, in 281 BCE in the

Gallic invasion of the Balkans, favoured by the troubled rule of the

Diadochi

The Diadochi (; singular: Diadochus; from grc-gre, Διάδοχοι, Diádochoi, Successors, ) were the rival generals, families, and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for control over his empire after his death in 323 BC. The War ...

after

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

.

A part of the invasion crossed over to

Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

and eventually settled in the area that came to be named after them, Galatia. The invaders, led by

Leonnorius

Leonnorius was one of the leaders of the Celts in their invasion of Macedonia and the adjoining countries.

When the main body under Brennus marched southwards into Macedonia and Greece (279 BC), Leonnorius and Lutarius led a detachment, twenty-th ...

and Lutarius, came at the invitation of

Nicomedes I

Nicomedes I ( grc, Νικομήδης; lived c. 300 BC – c. 255 BC, ruled 278 BC – c. 255 BC), second king of Bithynia, was the eldest son of Zipoetes I, whom he succeeded on the throne in 278 BC.

Life

He commenced his reign by putting ...

of

Bithynia, who required help in a dynastic struggle against his brother

Zipoites II. Three tribes crossed over from Thrace to Asia Minor. They numbered about 10,000 fighting men and about the same number of women and children, divided into three tribes,

Trocmi The Trocmii or Trocmi were one of the three ancient tribes of Galatia in central Asia Minor, together with the Tolistobogii and Tectosages,Livy, xxxviii. 16 part of the possible Gallic group who moved from Macedonia into Asia Minor

Anatolia ...

,

Tolistobogii

Tolistobogii (in other sources Tolistobogioi, Tolistobōgioi, Tolistoboioi, Tolistobioi, Toligistobogioi or Tolistoagioi) is the name used by the Roman historian, Livy, for one of the three ancient Gallic tribes of Galatia in central Asia Minor, ...

and

Tectosages

The Tectosages or Tectosagii (Gaulish: *''Textosagioi'', 'Dwelling-Seekers', or 'Possessions-Seekers') were one of the three ancient Gallic tribes of Galatia in central Asia Minor, together with the Tolistobogii and Trocmii.Livy, xxxviii. 16

...

(from the area of

Toulouse

Toulouse ( , ; oc, Tolosa ) is the prefecture of the French department of Haute-Garonne and of the larger region of Occitania. The city is on the banks of the River Garonne, from the Mediterranean Sea, from the Atlantic Ocean and from Pa ...

in southern France). They were eventually defeated by the

Seleucid

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the ...

king

Antiochus I

Antiochus I Soter ( grc-gre, Ἀντίοχος Σωτήρ, ''Antíochos Sōtér''; "Antiochus the Saviour"; c. 324/32 June 261 BC) was a Greek king of the Seleucid Empire. Antiochus succeeded his father Seleucus I Nicator in 281 BC and reigned du ...

, in a battle where the Seleucid war elephants shocked the Celts. While the momentum of the invasion was broken, the Galatians were by no means exterminated. Instead, the migration led to the establishment of a long-lived Celtic territory in central

Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

, which included the eastern part of ancient

Phrygia, a territory that became known as Galatia. There they ultimately settled, and being strengthened by fresh accessions of the same clan from Europe, they overran

Bithynia and supported themselves by plundering neighbouring countries.

In 189 BCE Rome sent

Gnaeus Manlius Vulso on an expedition against the Galatians. He defeated them. Galatia was henceforth dominated by Rome through regional rulers from 189 BCE onward.

Christianity, following its emergence in the

Near-Eastern part of Asia, was traditionally introduced by

Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

,

Martha

Martha (Hebrew: מָרְתָא) is a biblical figure described in the Gospels of Luke and John. Together with her siblings Lazarus and Mary of Bethany, she is described as living in the village of Bethany near Jerusalem. She was witness ...

,

Lazarus and some companions, who were expelled by persecutions from the

Holy Land. They traversed the Mediterranean in a frail boat with neither rudder nor mast and landed at ''

Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer

Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer (, lit.: "Saint Marys of the Sea"; Provençal Occitan: ''Li Santi Mario de la Mar'') is the capital of the Camargue ( Provençal Occitan ''Camarga'') in the south of France. It is a commune in the Bouches-du-Rhône ...

'' near

Arles

Arles (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Arle ; Classical la, Arelate) is a coastal city and commune in the South of France, a subprefecture in the Bouches-du-Rhône department of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, in the former province of ...

in 40 CE.

Provençal tradition names Lazarus as the first

bishop of Marseille, while Martha purportedly went on to tame

a terrible beast in nearby

Tarascon

Tarascon (; ), sometimes referred to as Tarascon-sur-Rhône, is a commune situated at the extreme west of the Bouches-du-Rhône department of France in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Inhabitants are referred to as Tarasconnais or Taras ...

. Pilgrims visited their tombs at the abbey of

Vézelay

Vézelay () is a commune in the department of Yonne in the north-central French region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté. It is a defensible hill town famous for Vézelay Abbey. The town and its 11th-century Romanesque Basilica of St Magdalene are de ...

in

Burgundy. In the Abbey of the Trinity at

Vendôme

Vendôme (, ) is a subprefecture of the department of Loir-et-Cher, France. It is also the department's third-biggest commune with 15,856 inhabitants (2019).

It is one of the main towns along the river Loir. The river divides itself at the ...

, a

phylactery

Phylactery () originally referred to tefillin, leather boxes containing Torah verses worn by some Jews when praying.

In Mandaeism, some different types of phylacteries are known as ''zrazta'' and ''qmaha'', a list of which can be found at list of ...

was said to contain a

tear shed by Jesus at the tomb of Lazarus. The cathedral of

Autun

Autun () is a subprefecture of the Saône-et-Loire department in the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region of central-eastern France. It was founded during the Principate era of the early Roman Empire by Emperor Augustus as Augustodunum to give a Ro ...

, not far away, is dedicated to Lazarus as ''Saint Lazaire''.

The first written records of Christians in France date from the 2nd century when

Irenaeus

Irenaeus (; grc-gre, Εἰρηναῖος ''Eirēnaios''; c. 130 – c. 202 AD) was a Greek bishop noted for his role in guiding and expanding Christian communities in the southern regions of present-day France and, more widely, for the dev ...

detailed the deaths of ninety-year-old bishop

Pothinus

Pothinus or Potheinos ( grc-gre, Ποθεινὸς; early 1st century BC – 48 or 47 BC), a eunuch, was regent for Pharaoh Ptolemy XIII Theos Philopator of the Ptolemaic Kingdom. He is most remembered for turning Ptolemy against his sister and co ...

of

Lugdunum

Lugdunum (also spelled Lugudunum, ; modern Lyon, France) was an important Roman city in Gaul, established on the current site of Lyon. The Roman city was founded in 43 BC by Lucius Munatius Plancus, but continued an existing Gallic settle ...

(

Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan language, Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, third-largest city and Urban area (France), second-largest metropolitan area of F ...

) and other martyrs of the 177

persecution in Lyon

The persecution in Lyon in AD 177 was a legendary persecution of Christians in Lugdunum, Roman Gaul (present-day Lyon, France), during the reign of Marcus Aurelius (161–180). As there is no coeval account of this persecution the earliest sourc ...

.

In 496

Remigius baptized

Clovis I, who was converted from

paganism to

Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. Clovis I, considered the founder of France, made himself the ally and protector of the papacy and his predominantly Catholic subjects.

In the beginning of the 5th century, various Asian nomadic tribes of

Iranian

Iranian may refer to:

* Iran, a sovereign state

* Iranian peoples, the speakers of the Iranian languages. The term Iranic peoples is also used for this term to distinguish the pan ethnic term from Iranian, used for the people of Iran

* Iranian lan ...

origin, especially the

Taifals

The Taifals or Tayfals ( la, Taifali, Taifalae or ''Theifali''; french: Taïfales) were a people group of Germanic or Sarmatian origin, first documented north of the lower Danube in the mid third century AD. They experienced an unsettled and fra ...

and

Sarmatian

The Sarmatians (; grc, Σαρμαται, Sarmatai; Latin: ) were a large confederation of ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic peoples of classical antiquity who dominated the Pontic steppe from about the 3rd century BC to the 4th cen ...

s, were settled in Gaul by the Romans as ''

coloni''. They settled in the regions of

Aquitaine

Aquitaine ( , , ; oc, Aquitània ; eu, Akitania; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Aguiéne''), archaic Guyenne or Guienne ( oc, Guiana), is a historical region of southwestern France and a former administrative region of the country. Since 1 Janu ...

and

Poitou

Poitou (, , ; ; Poitevin: ''Poetou'') was a province of west-central France whose capital city was Poitiers. Both Poitou and Poitiers are named after the Pictones Gallic tribe.

Geography

The main historical cities are Poitiers (historical c ...

, which at one point was even called ''Thifalia'' or ''Theiphalia'' (Theofalgicus) in the 6th century, with remaining place names such as

Tiffauges.

[''Merovingian military organization, 481–751'' by Bernard S. Bachrach p. 1]

/ref> Some Sarmatians had also been settled in the Rodez–Velay

Velay () is a historical area of France situated in east Haute-Loire ''département'' and south east of Massif central.

History

Julius Caesar mentioned the vellavi as subordinate of the arverni. Strabon suggested that they might have made ...

region.Alans

The Alans (Latin: ''Alani'') were an ancient and medieval Iranian nomadic pastoral people of the North Caucasus – generally regarded as part of the Sarmatians, and possibly related to the Massagetae. Modern historians have connected the A ...

who had allied and then split with the Visigoth

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is kn ...

s, entered into an agreement with the Romans which allowed them to settle in the area between Toulouse

Toulouse ( , ; oc, Tolosa ) is the prefecture of the French department of Haute-Garonne and of the larger region of Occitania. The city is on the banks of the River Garonne, from the Mediterranean Sea, from the Atlantic Ocean and from Pa ...

and the Mediterranean where they played a defensive role against the Visigoth in Spain.

The Roman general Aetius settled Alans in Gaul for military purposes, first in the region of Valence in 440 to control the lower Isère valley, and in 442 in the area around Orléans

Orléans (;["Orleans"](_blank)

(US) and [Armorica

Armorica or Aremorica (Gaulish: ; br, Arvorig, ) is the name given in ancient times to the part of Gaul between the Seine and the Loire that includes the Brittany Peninsula, extending inland to an indeterminate point and down the Atlantic Coast ...]

n '' Bacaudae''. Some cities have been named after them, such as Allaines or Allainville.

In 450 Attila proclaimed his intent to attack the powerful

In 450 Attila proclaimed his intent to attack the powerful Visigoth

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is kn ...

kingdom of Toulouse

Toulouse ( , ; oc, Tolosa ) is the prefecture of the French department of Haute-Garonne and of the larger region of Occitania. The city is on the banks of the River Garonne, from the Mediterranean Sea, from the Atlantic Ocean and from Pa ...

, making an alliance

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

with Emperor Valentinian III

Valentinian III ( la, Placidus Valentinianus; 2 July 41916 March 455) was Roman emperor in the West from 425 to 455. Made emperor in childhood, his reign over the Roman Empire was one of the longest, but was dominated by powerful generals vying ...

in order to do so. Attila gathered his vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain ...

s—Gepids

The Gepids, ( la, Gepidae, Gipedae, grc, Γήπαιδες) were an East Germanic tribe who lived in the area of modern Romania, Hungary and Serbia, roughly between the Tisza, Sava and Carpathian Mountains. They were said to share the religion ...

, Ostrogoths

The Ostrogoths ( la, Ostrogothi, Austrogothi) were a Roman-era Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Gothic kingdoms within the Roman Empire, based upon the large Gothic populations who ...

, Rugians

The Rugii, Rogi or Rugians ( grc, Ρογοί, Rogoi), were a Roman-era Germanic people. They were first clearly recorded by Tacitus, in his ''Germania'' who called them the ''Rugii'', and located them near the south shore of the Baltic Sea. Some ...

, Scirians

The Sciri, or Scirians, were a Germanic people. They are believed to have spoken an East Germanic language. Their name probably means "the pure ones".

The Sciri were mentioned already in the late 3rd century BC as participants in a raid on the ...

, Heruls

The Heruli (or Herules) were an early Germanic peoples, Germanic people. Possibly originating in Scandinavia, the Heruli are first mentioned by Ancient Rome, Roman authors as one of several "Scythians, Scythian" groups raiding Roman provinces in t ...

, Thuringians

The Thuringii, Toringi or Teuriochaimai, were an early Germanic people that appeared during the late Migration Period in the Harz Mountains of central Germania, a region still known today as Thuringia. It became a kingdom, which came into confl ...

, Alans, Burgundians, among others and began his march west. In 451 he arrived in Belgica with an army exaggerated by Jordanes to half a million strong. J.B. Bury

John Bagnell Bury (; 16 October 1861 – 1 June 1927) was an Anglo-Irish historian, classical scholar, Medieval Roman historian and philologist. He objected to the label "Byzantinist" explicitly in the preface to the 1889 edition of his ''Lat ...

believes that Attila's intent, by the time he marched west, was to extend his kingdom – already the strongest on the continent – across Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

to the Atlantic Ocean. On 7 April, Attila captured Metz

Metz ( , , lat, Divodurum Mediomatricorum, then ) is a city in northeast France located at the confluence of the Moselle and the Seille rivers. Metz is the prefecture of the Moselle department and the seat of the parliament of the Grand ...

. Saint Genevieve

Genevieve (french: link=no, Sainte Geneviève; la, Sancta Genovefa, Genoveva; 419/422 AD –

502/512 AD) is the patroness saint of Paris in the Catholic and Orthodox traditions. Her feast is on 3 January.

Genevieve was born in Nanterre a ...

is believed to have saved Paris.

The Romans under Aëtius allied with troops from among the Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools, ...

, the Burgundians, the Celts

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancien ...

, the Goths

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe ...

and the Alans and finally stopped the advancing Huns in the Battle of Châlons

The Battle of the Catalaunian Plains (or Fields), also called the Battle of the Campus Mauriacus, Battle of Châlons, Battle of Troyes or the Battle of Maurica, took place on June 20, 451 AD, between a coalition – led by the Roman general ...

.

Middle Ages

Exchanges with the Arab world (8th–13th centuries)

Following the rise of Islam in the Arabian peninsula in the 7th century, the Arabs invaded northern Africa, then the

Following the rise of Islam in the Arabian peninsula in the 7th century, the Arabs invaded northern Africa, then the Iberian peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

and France. They were finally repelled at the Battle of Poitiers in 732, but thereafter remained a significant presence in southern France and Spain.

Various exchanges are known around that time, as when Arculf

Arculf (later 7th century) was a Frankish bishop who toured the Levant in around 680. Bede claimed he was a bishop (). According to Bede's history of the Church in England (V, 15), Arculf was shipwrecked on the shore of Iona, Scotland on his return ...

, a Frankish Bishop, visited the Holy Land in the 670s.

Abbasid-Carolingian alliance

An Abbasid-Carolingian alliance

An Abbasid-Carolingian alliance

Heck, p. 172Carolingian Empire

The Carolingian Empire (800–888) was a large Frankish-dominated empire in western and central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the ...

and the Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

or the pro-Abbasid Muslim rulers in Spain.

These contacts followed an intense conflict between the Carolingians and the Umayyads Umayyads may refer to:

*Umayyad dynasty, a Muslim ruling family of the Caliphate (661–750) and in Spain (756–1031)

*Umayyad Caliphate (661–750)

:*Emirate of Córdoba (756–929)

:*Caliphate of Córdoba

The Caliphate of Córdoba ( ar, خ ...

, marked by the landslide Battle of Tours in 732, and were aimed at establishing a counter–alliance with the distant Abbasid Empire. There were numerous embassies between Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first ...

and the Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

caliph Harun al-Rashid

Abu Ja'far Harun ibn Muhammad al-Mahdi ( ar

, أبو جعفر هارون ابن محمد المهدي) or Harun ibn al-Mahdi (; or 766 – 24 March 809), famously known as Harun al-Rashid ( ar, هَارُون الرَشِيد, translit=Hārūn ...

from 797,

Cultural and scientific exchanges

From the 10th to the 13th century, Islamic contributions to Medieval Europe

During the High Middle Ages, the Islamic world was at its cultural peak, supplying information and ideas to Europe, via Al-Andalus, Sicily and the Crusader kingdoms in the Levant. These included Latin translations of the Greek Classics and of ...

, including France, were numerous, affecting such varied areas as art

Art is a diverse range of human activity, and resulting product, that involves creative or imaginative talent expressive of technical proficiency, beauty, emotional power, or conceptual ideas.

There is no generally agreed definition of wha ...

, architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing building ...

, medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pr ...

, agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people t ...

, music

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspe ...

, language

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of ...

, education

Education is a purposeful activity directed at achieving certain aims, such as transmitting knowledge or fostering skills and character traits. These aims may include the development of understanding, rationality, kindness, and honesty ...

, law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

, and technology

Technology is the application of knowledge to reach practical goals in a specifiable and Reproducibility, reproducible way. The word ''technology'' may also mean the product of such an endeavor. The use of technology is widely prevalent in me ...

. Over several centuries Europe absorbed knowledge from the Islamic civilization, but also knowledge from India or lost knowledge from the ancient Greeks which was being retransmitted by the Arabs. The French scientist Gerbert of Aurillac

Pope Sylvester II ( – 12 May 1003), originally known as Gerbert of Aurillac, was a French-born scholar and teacher who served as the bishop of Rome and ruled the Papal States from 999 to his death. He endorsed and promoted study of Arab and Gr ...

, future Pope Sylvester II

Pope Sylvester II ( – 12 May 1003), originally known as Gerbert of Aurillac, was a French-born scholar and teacher who served as the bishop of Rome and ruled the Papal States from 999 to his death. He endorsed and promoted study of Arab and Gre ...

, who had spent some time in Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a '' nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the nort ...

in the 960s, was instrumental in the adoption of Arabic numerals, as well as the abacus

The abacus (''plural'' abaci or abacuses), also called a counting frame, is a calculating tool which has been used since ancient times. It was used in the ancient Near East, Europe, China, and Russia, centuries before the adoption of the Hi ...

in France and Christian Europe.

France and the Near East (16th–19th centuries)

Between the 16th and 19th century, France had at times a relatively dormant relation with the Near East (or Western Asia

Western Asia, West Asia, or Southwest Asia, is the westernmost subregion of the larger geographical region of Asia, as defined by some academics, UN bodies and other institutions. It is almost entirely a part of the Middle East, and includes Ana ...

), while at other times was closely politically intertwined. Relations with the region were mostly dominated through the two empires that ruled the area, namely the rivaling Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, and the various Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

dynasties between these centuries (Safavids

Safavid Iran or Safavid Persia (), also referred to as the Safavid Empire, '. was one of the greatest Iranian empires after the 7th-century Muslim conquest of Persia, which was ruled from 1501 to 1736 by the Safavid dynasty. It is often conside ...

, Afsharids

Afsharid Iran ( fa, ایران افشاری), also referred as the Afsharid Empire was an Iranian empire established by the Turkoman Afshar tribe in Iran's north-eastern province of Khorasan, ruling Iran (Persia). The state was ruled by the Af ...

, and Qajars

The Qajar dynasty (; fa, دودمان قاجار ', az, Qacarlar ) was an IranianAbbas Amanat, ''The Pivot of the Universe: Nasir Al-Din Shah Qajar and the Iranian Monarchy, 1831–1896'', I. B. Tauris, pp 2–3 royal dynasty of Turkic origin ...

). The rivalry between the French, British, and Russians was a key factor in foreign policies for the French for the region, finding themselves at times allied with the Turks or Persians.

Franco-Ottoman alliance (16th–18th centuries)

Under the reign of Francis I, France became the first country in Europe to establish formal relations with the

Under the reign of Francis I, France became the first country in Europe to establish formal relations with the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, and to set up instruction in the Arabic language

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walte ...

, through the instruction of Guillaume Postel

Guillaume Postel (25 March 1510 – 6 September 1581) was a French linguist, astronomer, Christian Kabbalist, diplomat, polyglot, professor, religious universalist, and writer.

Born in the village of Barenton in Normandy, Postel made his w ...

at the Collège de France

The Collège de France (), formerly known as the ''Collège Royal'' or as the ''Collège impérial'' founded in 1530 by François I, is a higher education and research establishment ('' grand établissement'') in France. It is located in Paris n ...

.

A Franco-Ottoman alliance

The Franco-Ottoman Alliance, also known as the Franco-Turkish Alliance, was an alliance established in 1536 between the King of France Francis I and the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire Suleiman I. The strategic and sometimes tactical alliance was o ...

was established in 1536 between the king of France Francis I Francis I or Francis the First may refer to:

* Francesco I Gonzaga (1366–1407)

* Francis I, Duke of Brittany (1414–1450), reigned 1442–1450

* Francis I of France (1494–1547), King of France, reigned 1515–1547

* Francis I, Duke of Saxe-Lau ...

and the Turkish ruler of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

Suleiman the Magnificent

Suleiman I ( ota, سليمان اول, Süleyman-ı Evvel; tr, I. Süleyman; 6 November 14946 September 1566), commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent in the West and Suleiman the Lawgiver ( ota, قانونى سلطان سليمان, Ḳ ...

following the critical setbacks which Francis had encountered in Europe against Charles V Charles V may refer to:

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

* Charles V, Duke of Lorraine (1643–1690)

* Infa ...

. The alliance has been called "the first nonideological diplomatic alliance of its kind between a Christian and non-Christian empire". It caused a scandal in the Christian world,[Miller, p. 2] and was designated as "the impious alliance", or "the sacrilegious union of the Lily

''Lilium'' () is a genus of herbaceous flowering plants growing from bulbs, all with large prominent flowers. They are the true lilies. Lilies are a group of flowering plants which are important in culture and literature in much of the world. M ...

and the Crescent

A crescent shape (, ) is a symbol or emblem used to represent the lunar phase in the first quarter (the "sickle moon"), or by extension a symbol representing the Moon itself.

In Hinduism, Lord Shiva is often shown wearing a crescent moon on his ...

"; nevertheless, it endured since it served the objective interests of both parties.

The French forces, led by François de Bourbon and the Ottoman forces, led by Barbarossa

Barbarossa, a name meaning "red beard" in Italian, primarily refers to:

* Frederick Barbarossa (1122–1190), Holy Roman Emperor

* Hayreddin Barbarossa (c. 1478–1546), Ottoman admiral

* Operation Barbarossa, the Axis invasion of the Soviet Un ...

, joined at Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Fra ...

in August 1543, and collaborated to bombard the city of Nice

Nice ( , ; Niçard dialect, Niçard: , classical norm, or , nonstandard, ; it, Nizza ; lij, Nissa; grc, Νίκαια; la, Nicaea) is the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes departments of France, department in France. The Nice urban unit, agg ...

in the Siege of Nice

The siege of Nice occurred in 1543 and was part of the Italian War of 1542–46 in which Francis I and Suleiman the Magnificent collaborated as part of the Franco-Ottoman alliance against the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, and Henry VIII of Eng ...

.[''The Cambridge History of Islam'', p. 328] The Franco-Ottomans laid waste to the city, but met a stiff resistance which gave rise to the story of Catherine Ségurane. Afterwards, Francis allowed the Ottomans to winter at Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

.

The strategic and sometimes tactical alliance lasted for about three centuries,[Merriman, p. 132] until the Napoleonic Campaign in Egypt

The French campaign in Egypt and Syria (1798–1801) was Napoleon Bonaparte's campaign in the Ottoman territories of Egypt and Syria, proclaimed to defend French trade interests, to establish scientific enterprise in the region. It was the pr ...

, an Ottoman territory, in 1798–1801.

French diplomacy with Persia (16th–19th centuries)

The advent of Shah Ismail I

Ismail I ( fa, اسماعیل, Esmāʿīl, ; July 17, 1487 – May 23, 1524), also known as Shah Ismail (), was the founder of the Safavid dynasty of Safavid Iran, Iran, ruling as its King of Kings (''Shahanshah'') from 1501 to 1524. His re ...

in 1501 coincided with crucial world events. Becoming the eventual archrival of the Ottomans, the shah sought, unsuccessfully, to establish a precarious alliance against the Ottomans together with the Portuguese, Emperor Charles V, and King Ludvig II of Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the ...

.Francis I Francis I or Francis the First may refer to:

* Francesco I Gonzaga (1366–1407)

* Francis I, Duke of Brittany (1414–1450), reigned 1442–1450

* Francis I of France (1494–1547), King of France, reigned 1515–1547

* Francis I, Duke of Saxe-Lau ...

and Suleiman the Magnificent.Tabriz

Tabriz ( fa, تبریز ; ) is a city in northwestern Iran, serving as the capital of East Azerbaijan Province. It is the List of largest cities of Iran, sixth-most-populous city in Iran. In the Quri Chay, Quru River valley in Iran's historic Aze ...

during the Ottoman-Safavid War (1532-1555), he was accompanied by the French ambassador Gabriel de Luetz

Gabriel de Luetz, Baron et Seigneur d'Aramon et de Vallabregues (died 1553), often also abbreviated to Gabriel d'Aramon, was the French Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire from 1546 to 1553, in the service first of Francis I, who dispatched him to ...

, whose advice enabled the Ottomans to force the Persians to surrender the citadel of Van.Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

and the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia (country), Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range ...

.Safavids

Safavid Iran or Safavid Persia (), also referred to as the Safavid Empire, '. was one of the greatest Iranian empires after the 7th-century Muslim conquest of Persia, which was ruled from 1501 to 1736 by the Safavid dynasty. It is often conside ...

. However, France played an important part in post-Safavid external policies through Marquis de Bonnac, ambassador to the Porte, and who was an active mediator between Russia, Iran, and Turkey, all regional rivals.Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

.

Franco-Persian alliance (19th century)

Despite the hostility of Russian Empress Catherine the Great towards both neighbouring rival

Despite the hostility of Russian Empress Catherine the Great towards both neighbouring rival Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

and the French Revolution, the ascendancy of the new monarchy in Persia represented by the Qajar dynasty did not at once led to closer relations between the two,Guillaume-Antoine Olivier

Guillaume-Antoine Olivier (; 19 January 1756, Les Arcs near Toulon – 1 October 1814, Lyon) was a French entomologist and naturalist.

Life

Olivier studied medicine in Montpellier, where he became good friends with Pierre Marie Auguste Brous ...

.Fath-Ali Shah Qajar

Fath-Ali Shah Qajar ( fa, فتحعلىشاه قاجار, Fatḥ-ʻAli Šâh Qâjâr; May 1769 – 24 October 1834) was the second Shah (king) of Qajar Iran. He reigned from 17 June 1797 until his death on 24 October 1834. His reign saw the irr ...

asked Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

to help him recover Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, which had been ruled by Persia for centuries and was part of its integral domains, but had been invaded and annexed by Imperial Russia. Following his victory at

Following his victory at Austerlitz Austerlitz may refer to:

History

* Battle of Austerlitz, an 1805 victory by the French Grand Army of Napoleon Bonaparte

Places

* Austerlitz, German name for Slavkov u Brna in the Czech Republic, which gave its name to the Battle of Austerlitz a ...

in 1805, Napoleon managed to establish the short-lived Franco-Ottoman alliance

The Franco-Ottoman Alliance, also known as the Franco-Turkish Alliance, was an alliance established in 1536 between the King of France Francis I and the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire Suleiman I. The strategic and sometimes tactical alliance was o ...

and a Franco-Persian alliance

A Franco-Persian alliance or Franco-Iranian alliance was formed for a short period between the French Empire of Napoleon I and Fath Ali Shah of Qajar Persia against Russia and Great Britain between 1807 and 1809. The alliance was part of a plan ...

formalized in the Treaty of Finckenstein

The Treaty of Finckenstein, often spelled Finkenstein, was a treaty concluded between France and Persia (Iran) in the Finckenstein Palace (now Kamieniec, Poland) on 4 May 1807 and formalised the Franco-Persian alliance.

Napoleon I guaranteed ...

in 1807, while Persia and Russia were already for three years in the Russo-Persian War (1804-1813)

The Russo-Persian Wars or Russo-Iranian Wars were a series of conflicts between 1651 and 1828, concerning Persia (Iran) and the Russian Empire. Russia and Persia fought these wars over disputed governance of territories and countries in the Cau ...

, in order to obtain strategic support in his fight against the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

.

The treaty included French support for Persia to reclaim its lost territories comprising Georgia and other territories in the Caucasus that were occupied by Russia by that time, promising to act so that Russia would surrender the territory. In exchange, Persia was to fight Great Britain, and allow France to cross the Persian territory to eventually reach India.

"The Islamic World in decline" by Martin Sicker p. 97Treaty of Tilsit

The Treaties of Tilsit were two agreements signed by French Emperor Napoleon in the town of Tilsit in July 1807 in the aftermath of his victory at Friedland. The first was signed on 7 July, between Napoleon and Russian Emperor Alexander, when ...

made the alliance lose its motivation. The ongoing Russo-Persian War (1804-1813)

The Russo-Persian Wars or Russo-Iranian Wars were a series of conflicts between 1651 and 1828, concerning Persia (Iran) and the Russian Empire. Russia and Persia fought these wars over disputed governance of territories and countries in the Cau ...

despite several successes partly influenced due to initial French assistance, resulted eventually in combination with the Treaty of Tilsit in a disaster for Persia, as not only was it forced to recognize Russian suzerainty over Georgia, its own land which it had been ruling for centuries, but it also facilitated the cession of Dagestan and most of what is today Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan (, ; az, Azərbaycan ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, , also sometimes officially called the Azerbaijan Republic is a transcontinental country located at the boundary of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is a part of t ...

to Russia amongst the other terms of the Treaty of Gulistan

The Treaty of Gulistan (russian: Гюлистанский договор; fa, عهدنامه گلستان) was a peace treaty concluded between the Russian Empire and Iran on 24 October 1813 in the village of Gulistan (now in the Goranboy Distr ...

.

French plans in Egypt

Napoleon attempted to establish a decisive French presence in Asia, by first launching his Egyptian Campaign

The French campaign in Egypt and Syria (1798–1801) was Napoleon Bonaparte's campaign in the Ottoman territories of Egypt and Syria, proclaimed to defend French trade interests, to establish scientific enterprise in the region. It was the pr ...

in 1798. He wished to establish a French presence in the Middle East, and was then planning to make a junction with Tippu Sahib in India, against the British. Napoleon assured the Directoire

The Directory (also called Directorate, ) was the governing five-member committee in the French First Republic from 2 November 1795 until 9 November 1799, when it was overthrown by Napoleon Bonaparte in the Coup of 18 Brumaire and replaced by ...

that ''"as soon as he had conquered Egypt, he will establish relations with the Indian princes and, together with them, attack the English in their possessions."''

''Napoleon and Persia'' by Iradj Amini, p. 12Suez

Suez ( ar, السويس '; ) is a seaport city (population of about 750,000 ) in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez (a branch of the Red Sea), near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal, having the same bou ...

to India, to join the forces of Tipu-Sahib and drive away the English."''

Commercial, religious and military expansion (16th–18th century)

Early-modern contacts with East-Asia (1527-)

France began trading with Eastern Asia from the early 16th century. In 1526, a sailor from

France began trading with Eastern Asia from the early 16th century. In 1526, a sailor from Honfleur

Honfleur () is a commune in the Calvados department in northwestern France. It is located on the southern bank of the estuary of the Seine across from le Havre and very close to the exit of the Pont de Normandie. The people that inhabit Honf ...

named Pierre Caunay sailed to Sumatra. He lost his ship on the return leg between Africa and Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

, where the crew was imprisoned by the Portuguese.[''Orientalism in early Modern France'' 2008 Ina Baghdiantz McAbe, p. 78, ] In July 1527, a French Norman

Norman or Normans may refer to:

Ethnic and cultural identity

* The Normans, a people partly descended from Norse Vikings who settled in the territory of Normandy in France in the 10th and 11th centuries

** People or things connected with the Norm ...

trading ship from Rouen is recorded by the Portuguese João de Barros to have arrived in the Indian city of Diu.Dieppe maps

The Dieppe maps are a series of world maps and atlases produced in Dieppe, France, in the 1540s, 1550s, and 1560s. They are large hand-produced works, commissioned for wealthy and royal patrons, including Henry II of France and Henry VIII of Engla ...

, influencing the work of Dieppe cartographers, such as Jean Rotz

Jean Rotz, also called Johne Rotz, was a 16th-century French artist-cartographer. He was born to a Scottish father and a French mother.

Career

Rotz was a member of the school of the Dieppe maps. He may have accompanied Jean Parmentier to Sumatra ...

.

Following the Portuguese and Spanish forays into Asia after 1500, a few Frenchmen participated in the activities of Catholic religious orders in these countries during the 16th century. The first instance of France-Thailand relations occurred according to the Jesuit Giovanni Pietro Maffei when about 1550 a French Franciscan

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

, Bonferre, hearing of the great kingdom of the Peguans and the Siam

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

ese in the East, went on a Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

ship from Goa

Goa () is a state on the southwestern coast of India within the Konkan region, geographically separated from the Deccan highlands by the Western Ghats. It is located between the Indian states of Maharashtra to the north and Karnataka to the ...

to Cosme (Pegu

Bago (formerly spelt Pegu; , ), formerly known as Hanthawaddy, is a city and the capital of the Bago Region in Myanmar. It is located north-east of Yangon.

Etymology

The Burmese name Bago (ပဲခူး) is likely derived from the Mon langua ...

), where for three years he preached the Gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message (" the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words a ...

, but without any result.

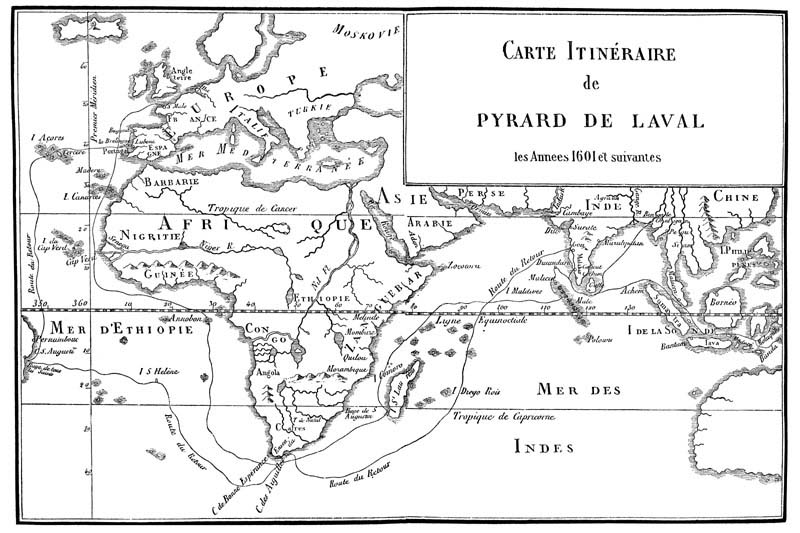

François Pyrard and François Martin (1601–1611)

In December 1600 a company was formed through the association of

In December 1600 a company was formed through the association of Saint-Malo

Saint-Malo (, , ; Gallo: ; ) is a historic French port in Ille-et-Vilaine, Brittany, on the English Channel coast.

The walled city had a long history of piracy, earning much wealth from local extortion and overseas adventures. In 1944, the Alli ...

, Laval and Vitré, to trade with the Moluccas

The Maluku Islands (; Indonesian: ''Kepulauan Maluku'') or the Moluccas () are an archipelago in the east of Indonesia. Tectonically they are located on the Halmahera Plate within the Molucca Sea Collision Zone. Geographically they are located ...

and Japan.Maldives

Maldives (, ; dv, ދިވެހިރާއްޖެ, translit=Dhivehi Raajje, ), officially the Republic of Maldives ( dv, ދިވެހިރާއްޖޭގެ ޖުމްހޫރިއްޔާ, translit=Dhivehi Raajjeyge Jumhooriyyaa, label=none, ), is an archipelag ...

, leading to the adventure of François Pyrard de Laval

François Pyrard de Laval (; 1578 – ca. 1623) was a French navigator who is remembered for a personal written account of his adventures in the Maldives Islands from 1602 to 1607, which was part of a ten-year sojourn (1601–1611) in South Asia, ...

who managed to return to France in 1611.Far East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The ter ...

in 1604, at the request of Henry IV, and from that time numerous accounts on Asia were published.French East India Company

The French East India Company (french: Compagnie française pour le commerce des Indes orientales) was a colonial commercial enterprise, founded on 1 September 1664 to compete with the English (later British) and Dutch trading companies in th ...

on the model of England and the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

.Dieppe

Dieppe (; Norman: ''Dgieppe'') is a coastal commune in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France.

Dieppe is a seaport on the English Channel at the mouth of the river Arques. A regular ferry service runs to N ...

merchants to form the Dieppe Company

The Dieppe Company (french: Compagnie de Dieppe) was a 17th-century French overseas trading company. It was founded on 1 June 1604 through the issuance of letter patents by Henry IV to Dieppe merchants, with an eye to Far East trade possibilities ...

, giving them exclusive rights to Asian trade for 15 years, but no ships were actually sent.Nicolas Trigault

Nicolas Trigault (1577–1628) was a Jesuit, and a missionary in China. He was also known by his latinised name Nicolaus Trigautius or Trigaultius, and his Chinese name Jin Nige ().

Life and work

Born in Douai (then part of the County of Flanders ...

resumed France-China relations when he left Europe to do missionary work in Asia around 1610, eventually arriving at Nanjing

Nanjing (; , Mandarin pronunciation: ), alternately romanized as Nanking, is the capital of Jiangsu province of the People's Republic of China. It is a sub-provincial city, a megacity, and the second largest city in the East China region. T ...

, China in 1611.

Hasekura Tsunenaga (1615)

France-Japan relations started in 1615 when

France-Japan relations started in 1615 when Hasekura Tsunenaga

was a kirishitan Japanese samurai and retainer of Date Masamune, the daimyō of Sendai. He was of Japanese imperial descent with ancestral ties to Emperor Kanmu. Other names include Philip Francis Faxicura, Felipe Francisco Faxicura, and Phi ...

, a Japanese samurai and ambassador, sent to Rome by Date Masamune, landed at Saint-Tropez for a few days. In 1636, Guillaume Courtet

Guillaume Courtet, OP (1589–1637) was a French Dominican priest who has been described as the first Frenchman to have visited Japan. He was martyred in 1637 and canonized in 1987.

Career

Courtet was born in Sérignan, near Béziers, in 1589 o ...

, a French Dominican priest, would reciprocate when he set foot in Japan. He penetrated into Japan clandestinely, against the 1613 interdiction of Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

. He was caught, tortured, and died in Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest Cities of Japan, city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole Nanban trade, port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hi ...

on 29 September 1637.

Company of the Moluccas (1615)

In 1615, the regent Marie de Médicis

Marie de' Medici (french: link=no, Marie de Médicis, it, link=no, Maria de' Medici; 26 April 1575 – 3 July 1642) was Queen of France and Navarre as the second wife of King Henry IV of France of the House of Bourbon, and Regent of the Kingd ...

incorporated the merchants of Dieppe and other harbours to found the Company of the Moluccas. In 1616, two expeditions were Asia–bound from Honfleur

Honfleur () is a commune in the Calvados department in northwestern France. It is located on the southern bank of the estuary of the Seine across from le Havre and very close to the exit of the Pont de Normandie. The people that inhabit Honf ...

in Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

: three ships left for India, and two ships for Bantam. One ship returned from Bantam in 1617 with a small cargo, and letters from the Dutch expressing their hostility towards French ships in the East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies), is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The Indies refers to various lands in the East or the Eastern hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainlands found in and around ...

.Saint-Malo

Saint-Malo (, , ; Gallo: ; ) is a historic French port in Ille-et-Vilaine, Brittany, on the English Channel coast.

The walled city had a long history of piracy, earning much wealth from local extortion and overseas adventures. In 1944, the Alli ...

to Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's mos ...

. One was captured by the Dutch, but the other obtained an agreement from the ruler of Pondicherry

Pondicherry (), now known as Puducherry ( French: Pondichéry ʊdʊˈtʃɛɹi(listen), on-dicherry, is the capital and the most populous city of the Union Territory of Puducherry in India. The city is in the Puducherry district on the sout ...

to build a fortress and a factory there, and returned with a rich cargo. In 1619, an armed expedition composed of three ships (275 crew, 106 cannons) called the "Fleet of Montmorency" under General Augustin de Beaulieu was sent from Honfleur, to fight the Dutch in the Far East. They encountered the Dutch fleet off Sumatra. One ship was captured, another remained in Asia for inter-country trade, and the third returned to

In 1619, an armed expedition composed of three ships (275 crew, 106 cannons) called the "Fleet of Montmorency" under General Augustin de Beaulieu was sent from Honfleur, to fight the Dutch in the Far East. They encountered the Dutch fleet off Sumatra. One ship was captured, another remained in Asia for inter-country trade, and the third returned to Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very ...

in 1622. In 1624, with the Treaty of Compiègne

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal pers ...

, Richelieu obtained that the Dutch would stop fighting the French in the East.Isaac de Razilly

Isaac de Razilly (1587 – 1635) was a member of the French nobility appointed a knight of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem at the age of 18. He was born at the Château d'Oiseaumelle in the Province of Touraine, France. A member of the French ...

commented however:

However, trade further developed, with the activities of people such as

However, trade further developed, with the activities of people such as Jean de Thévenot

Jean de Thévenot (16 June 1633 – 28 November 1667) was a French traveller in the East, who wrote extensively about his journeys. He was also a linguist, natural scientist and botanist.

Education

He was born in Paris and received his educa ...

and Jean-Baptiste Tavernier

Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (1605–1689) was a 17th-century French gem merchant and traveler. Tavernier, a private individual and merchant traveling at his own expense, covered, by his own account, 60,000 leagues in making six voyages to Persia ...

in 17th century Asia. Gilles de Régimont travelled to Persia and India in 1630 and returned in 1632 with a rich cargo. He formed a trading company at Dieppe in 1633, and sent ships every year to the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by t ...

.Goa

Goa () is a state on the southwestern coast of India within the Konkan region, geographically separated from the Deccan highlands by the Western Ghats. It is located between the Indian states of Maharashtra to the north and Karnataka to the ...

in the mission of Francis Xavier

Francis Xavier (born Francisco de Jasso y Azpilicueta; Latin: ''Franciscus Xaverius''; Basque: ''Frantzisko Xabierkoa''; French: ''François Xavier''; Spanish: ''Francisco Javier''; Portuguese: ''Francisco Xavier''; 7 April 15063 December ...

, was martyred in Aceh.

Expansion under Louis XIV

France adopted a more structured approach to its expansion in Asia during the 17th century during the rule of Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Ver ...

, in an organized attempt to establish a mercantile empire by taking a share of the lucrative market of the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by t ...

. On the religious plane, the Paris Foreign Missions Society

The Society of Foreign Missions of Paris (french: Société des Missions Etrangères de Paris, short M.E.P.) is a Roman Catholic missionary organization. It is not a religious institute, but an organization of secular priests and lay persons de ...

was formed from 1658 in order to provide for missionary work in Asia mainly, under French control. Soon after, the French East India Company

The French East India Company (french: Compagnie française pour le commerce des Indes orientales) was a colonial commercial enterprise, founded on 1 September 1664 to compete with the English (later British) and Dutch trading companies in th ...

was established in 1664.

In 1664 a mission was sent to

In 1664 a mission was sent to Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

under François Caron

François Caron (1600–1673) was a French Huguenot refugee to the Netherlands who served the Dutch East India Company (''Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie'' or VOC) for 30 years, rising from cook's mate to the director-general at Batavia (Ja ...

, formerly in the service of the Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

. The Madagascar mission failed, but soon after, Caron succeeded in founding French outposts at Surat (1668) and at Masulipatam

Machilipatnam (), also known as Masulipatnam and Bandar, is a city in Krishna district of the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh. It is a municipal corporation and the administrative headquarters of Krishna district. It is also the mandal headquarte ...

(1669) in India;.[Pope, George Uglow. (1880)]

''A Text-book of Indian History,'' p. 266 Caron became "Commissaire" at Pondicherry (1668—1672). The French East India Company set up a trading centre at Pondicherry in 1673. This outpost eventually became the chief French settlement in India.

In 1672, Caron helped lead French forces in Ceylon, where the strategic bay at Trincomalee

Trincomalee (; ta, திருகோணமலை, translit=Tirukōṇamalai; si, ත්රිකුණාමළය, translit= Trikuṇāmaḷaya), also known as Gokanna and Gokarna, is the administrative headquarters of the Trincomalee Dis ...

was captured and St. Thomé (also known as Meilâpûr) on the Coromandel coast

The Coromandel Coast is the southeastern coastal region of the Indian subcontinent, bounded by the Utkal Plains to the north, the Bay of Bengal to the east, the Kaveri delta to the south, and the Eastern Ghats to the west, extending over an ...

was also taken.[Frazer, Robert Watson. (1896)]

''British India,'' p. 42

During the reign of Louis XIV, France further developed France–Thailand relations

France–Thailand relations cover a period from the 16th century until modern times. Relations started in earnest during the reign of Louis XIV of France with numerous reciprocal embassies and a major attempt by France to Christianize the kingdom ...

and sent numerous embassies to Siam

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

, led by Chevalier de Chaumont

Alexandre, Chevalier de Chaumont (1640 – 28 January 1710 in Paris) was the first French ambassador for King Louis XIV in Siam in 1685.Chakrabongse, C., 1960, Lords of Life, London: Alvin Redman Limited He was accompanied on his mission by Ab ...

in 1685 and later by Simon de la Loubère

Simon de la Loubère (; 21 April 1642 – 26 March 1729) was a French diplomat to Siam (Thailand), writer, mathematician and poet. He is credited with bringing back a document which introduced Europe to Indian astronomy, the "Siamese method" ...

in 1687, until French troops were ousted from the country following the 1688 Siege of Bangkok

The siege of Bangkok was a key event of the Siamese revolution of 1688, in which the Kingdom of Siam ousted the French from Siam. Following a coup d'état, in which the pro-Western king Narai was replaced by Phetracha, Siamese troops besieged the F ...

. Around the same time France actively participated in the Jesuit China missions, as Louis XIV sent in 1685 a mission of five Jesuits "mathematicians" to China in an attempt to break the Portuguese predominance: Jean de Fontaney

Jean de Fontaney (1643–1710) was a French Jesuit who led a mission to China in 1687.Mungello, p. 329

Jean de Fontaney had been a teacher of mathematics and astronomy at the College Louis le Grand. He was asked by king Louis XIV to set up a m ...

(1643–1710), Joachim Bouvet

Joachim Bouvet (, courtesy name: 明远) (July 18, 1656, in Le Mans – June 28, 1730, in Peking) was a French Jesuit who worked in China, and the leading member of the Figurist movement.

China

Bouvet came to China in 1687, as one of six Jesuit ...

(1656–1730), Jean-François Gerbillon

Jean-François Gerbillon (4 June 1654, Verdun, France – 27 March 1707, Peking, China) was a French missionary who worked in China.

He entered the Society of Jesus, 5 Oct, 1670, and after completing the usual course of study taught grammar and ...

(1654–1707), Louis Le Comte Louis le Comte (1655–1728), also Louis-Daniel Lecomte, was a French Jesuit who participated in the 1687 French Jesuit mission to China under Jean de Fontaney. He arrived in China on 7 February 1688.

He returned to France in 1691 as Procurator of ...

(1655–1728) and Claude de Visdelou (1656–1737). While French Jesuits were found at the court of the Manchu Kangxi Emperor

The Kangxi Emperor (4 May 1654– 20 December 1722), also known by his temple name Emperor Shengzu of Qing, born Xuanye, was the third emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the second Qing emperor to rule over China proper, reigning from 1661 to ...

in China, Louis received the visit of a Chinese Jesuit, Michael Shen Fu-Tsung, by 1684. Furthermore, several years later, he had at his court a Chinese librarian and translator — Arcadio Huang

Arcadio Huang (, born in Xinghua, modern Putian, in Fujian, 15 November 1679, died on 1 October 1716 in Paris)Mungello, p.125 was a Chinese Christian convert, brought to Paris by the Missions étrangères. He took a pioneering role in the teachi ...

.

Louis XV/ Louis XVI

After these first experiences, France took a more active role in Asia from its base in India. France was able to establish the beginnings of a commercial and territorial empire in India, leading to the formation of French India. Active Franco-Indian alliances were established to reinforce French influence and counter British influence on the

After these first experiences, France took a more active role in Asia from its base in India. France was able to establish the beginnings of a commercial and territorial empire in India, leading to the formation of French India. Active Franco-Indian alliances were established to reinforce French influence and counter British influence on the subcontinent

A continent is any of several large landmasses. Generally identified by convention rather than any strict criteria, up to seven geographical regions are commonly regarded as continents. Ordered from largest in area to smallest, these seven ...

. Suffren had a considerable role in upholding French naval power in the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by t ...

.

Burma–France relations started in 1727 with approaches by Joseph François Dupleix

Joseph Marquis Dupleix (23 January 1697 – 10 November 1763) was Governor-General of French India and rival of Robert Clive.

Biography

Dupleix was born in Landrecies, on January 23, 1697. His father, François Dupleix, a wealthy ''fermier gé ...

, and were cemented in 1729 with the building of a shipyard in the city of Syriam. France allied with the Mon people

The Mon ( mnw, ဂကူမည်; my, မွန်လူမျိုး, ; th, มอญ, ) are an ethnic group who inhabit Lower Myanmar's Mon State, Kayin State, Kayah State, Tanintharyi Region, Bago Region, the Irrawaddy Delta, and se ...

and participated in the Burman-Mon conflict in 1751–1756 under Sieur de Bruno and Pierre de Milard

Pierre de Milard (often referred to as Chevalier Milard, also spelled Chevalier Millard; 1736–1778) was a French Navy officer, who became a senior officer and noble in the Royal Burmese Armed Forces. He had a key role in supporting the Burmese m ...

.

The geographical exploration of Asia was expanded thanks to the efforts of Bougainville and La Pérouse.

Following the development of France-Vietnam relations through early trade and religious contacts, France intervened militarily in Vietnam at the end of the 18th century through the French assistance to Nguyễn Ánh under Mgr Pigneau de Behaine

Pierre Joseph Georges Pigneau (2 November 1741 in Origny-en-Thiérache – 9 October 1799, in Qui Nhơn), commonly known as Pigneau de Béhaine (), also Pierre Pigneaux, Bá Đa Lộc ("Pedro" 百 多 祿), Bách Đa Lộc ( 伯 多 祿) and ...

.

France thus managed to gain strong positions in South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth descr ...

and Southeastern Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainland ...

, but these efforts were essentially wrecked with the outcome of the French revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

and Napoleonic wars