Foreign relations of South Africa during apartheid on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Foreign relations of South Africa during apartheid refers to the

Relations between the

Relations between the

While some countries and organizations, like the Swiss-South African Association, supported the Apartheid government, most of the international community isolated South Africa. One of the primary means for the international community to show its aversion to apartheid was to

While some countries and organizations, like the Swiss-South African Association, supported the Apartheid government, most of the international community isolated South Africa. One of the primary means for the international community to show its aversion to apartheid was to

While international opposition to apartheid grew, the

While international opposition to apartheid grew, the

foreign relations of South Africa

The foreign relations of South Africa have spanned from the country's time as Dominion of the British Empire to its isolationist policies under Apartheid to its position as a responsible international actor taking a key role in Africa, particu ...

between 1948 and the early 1990s. South Africa introduced ''apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

'' in 1948, as a systematic extension of pre-existing racial discrimination

Racial discrimination is any discrimination against any individual on the basis of their skin color, race or ethnic origin.Individuals can discriminate by refusing to do business with, socialize with, or share resources with people of a certain g ...

laws. Initially the regime implemented an offensive foreign policy trying to consolidate South African hegemony over Southern Africa. These attempts had clearly failed by the late 1970s. As a result of its racism, occupation of Namibia

Namibia (, ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and ea ...

and foreign interventionism in Angola

, national_anthem = "Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordinat ...

, the country became increasingly isolated internationally.

Initial relations

In the aftermath ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

and the Nazi Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

, the Western world quickly distanced itself from ideas of racial dominanceSee Borstelmann, Thomas; 'Jim Crow’s coming out: Race relations and American foreign policy in the Truman years'; ''Presidential Studies Quarterly

''Presidential Studies Quarterly'' is a quarterly peer-reviewed political science journal dedicated to the scholarly study of the presidency of the United States. It was established in 1971 as ''Center House Bulletin'', obtaining its current name ...

''; volume 29, issue 3, (September 1999), pp. 549-569 and policies based on racial prejudice. Racially discriminatory

Racial discrimination is any discrimination against any individual on the basis of their skin color, race or ethnic origin.Individuals can discriminate by refusing to do business with, socialize with, or share resources with people of a certain g ...

and segregationist

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crime against humanity under the Statute of the Interna ...

principles were not novelties in South Africa, given the racial make-up of their society. From unification in 1910, the state had been run by the white minority and pursued segregation from there. Apartheid was a certified, lawful and inflexible type of separation that was methodically entrenched from 1948 through a battery of legislation. As it was not completely new to the country, and because many Western countries still exercised their own forms of prejudice in their assorted colonies, there was minimal rejoinder and indignation. The conclusion of the Second World War signified the commencement of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

, and South Africa, with its anticommunist stance, was considered a possible assistant in the passive battle against the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

.

The world did not, however, condone South Africa's discriminatory policies. At the first UN gathering in 1946, South Africa was placed on the program. The primary subject in question was the handling of South African Indians

Indian South Africans are South Africans who descend from indentured labourers and free migrants who arrived from British India during the late 1800s and early 1900s. The majority live in and around the city of Durban, making it one of the l ...

, a critical cause of hostility between South Africa and India. In 1952, apartheid was thrashed out again in the aftermath of the Defiance Campaign

The Defiance Campaign against Unjust Laws was presented by the African National Congress (ANC) at a conference held in Bloemfontein, South Africa in December 1951. The Campaign had roots in events leading up the conference. The demonstrations, ...

, and Indian demands caused the U.N. to set up a task team to keep watch on the state of racial affairs and the progress of apartheid in South Africa. Although racial segregation in South Africa was a cause for concern, most countries in the UN concurred that race was an internal issue for South Africa, which fell outside the UN's jurisdiction. Only later did the United Nations become resolute in challenging South Africa. In 1952 13 African and Asian countries sponsored a U.N. General Assembly resolution condemning apartheid as a violation of the Charter of the United Nations

The Charter of the United Nations (UN) is the foundational treaty of the UN, an intergovernmental organization. It establishes the purposes, governing structure, and overall framework of the UN system, including its six principal organs: the ...

.

Sharpeville and the severing of British ties

South Africa's policies were subject to international scrutiny in 1960, whenBritish Prime Minister

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As moder ...

Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986) was a British Conservative statesman and politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Caricatured as " Supermac", ...

criticised them during his celebrated Wind of Change speech in Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

. Weeks later, tensions came to a head in the Sharpeville massacre

The Sharpeville massacre occurred on 21 March 1960 at the police station in the township of Sharpeville in the then Transvaal Province of the then Union of South Africa (today part of Gauteng). After demonstrating against pass laws, a crowd ...

, resulting in more international condemnation. Soon thereafter, Verwoerd announced a referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a Representative democr ...

on whether the country should sever links with the British monarchy

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiwi ...

and become a republic instead. Verwoerd lowered the voting age

A voting age is a minimum age established by law that a person must attain before they become eligible to vote in a public election. The most common voting age is 18 years; however, voting ages as low as 16 and as high as 25 currently exist

( ...

for whites to eighteen and included whites in South West Africa

South West Africa ( af, Suidwes-Afrika; german: Südwestafrika; nl, Zuidwest-Afrika) was a territory under South African administration from 1915 to 1990, after which it became modern-day Namibia. It bordered Angola (Portuguese colony before 1 ...

on the voter's roll. The referendum on 5 October that year asked whites, "Do you support a republic for the Union?", and 52 per cent voted "Yes".

As a consequence of this change of status, South Africa needed to reapply for continued membership of the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

, with which it had privileged trade links. Even though India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

became a republic within the Commonwealth

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

in 1950 it became clear that African and Asian member states would oppose South Africa due to its apartheid policies. As a result, South Africa withdrew from the Commonwealth on the 31st of May, 1961, the day that the Republic came into existence.

In 1960, the UN's conservative stance on apartheid changed. The Sharpeville massacre had jolted the global neighbourhood, with the apartheid regime showing that it would use violent behaviour to repress opposition to racial inequity. Many Western states began to see apartheid as a possible danger to global harmony, as the policy caused much intercontinental abrasion over human-rights violation.

In April 1960, the Security Council of the UN settled for the first time on concerted action against the apartheid regime, demanding that the NP bring an end to racial separation and discrimination; but, instead, the South African administration merely employed further suppressive instruments. The ANC and PAC Pac or PAC may refer to:

Military

* Rapid Deployment Force (Malaysia), an armed forces unit

* Patriot Advanced Capability, of the MIM-104 Patriot missile

* Civil Defense Patrols (''Patrullas de Autodefensa Civil''), Guatemalan militia and paramil ...

were forbidden from continued existence, and political assemblies were prohibited. From then on, the UN placed the South African issue high on its list of priorities.

In 1961, UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld

Dag Hjalmar Agne Carl Hammarskjöld ( , ; 29 July 1905 – 18 September 1961) was a Swedish economist and diplomat who served as the second Secretary-General of the United Nations from April 1953 until his death in a plane crash in September 196 ...

stopped over in South Africa and subsequently stated that he had been powerless to effect a concurrence with Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd

Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd (; 8 September 1901 – 6 September 1966) was a South African politician, a scholar of applied psychology and sociology, and chief editor of '' Die Transvaler'' newspaper. He is commonly regarded as the architect ...

. That same year, Verwoerd proclaimed South Africa's extraction from the Commonwealth as a result of its censure of his government.

Sanctions

On 6 November 1962, theUnited Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Curr ...

passed Resolution 1761, condemning South African apartheid policies. On 7 August 1963 the United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, ...

passed Resolution 181

The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was a proposal by the United Nations, which recommended a partition of Mandatory Palestine at the end of the British Mandate. On 29 November 1947, the UN General Assembly adopted the Plan as R ...

calling for a voluntary arms embargo

An arms embargo is a restriction or a set of sanctions that applies either solely to weaponry or also to " dual-use technology." An arms embargo may serve one or more purposes:

* to signal disapproval of the behavior of a certain actor

* to maintai ...

against South Africa, and that very year, a Special Committee Against Apartheid was established to encourage and oversee plans of action against the regime.

In 1966, the United Nations held the first (of many) colloquiums on apartheid. The General Assembly announced 21 March as the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, in memory of the Sharpeville massacre

The Sharpeville massacre occurred on 21 March 1960 at the police station in the township of Sharpeville in the then Transvaal Province of the then Union of South Africa (today part of Gauteng). After demonstrating against pass laws, a crowd ...

. In 1971, the UN General Assembly formally denounced the institution of homelands, and a motion was passed in 1974 to eject South Africa from the UN, but this was discarded by France, Britain and the United States of America, all of them key trade associates of South Africa.

One probable type of action against South Africa was economic sanction. If UN affiliates broke fiscal and trading links with the country, it would make it all the trickier for the apartheid government to uphold itself and its policies. Such sanctions were argued frequently within the UN, and many recognised and backed it as an effectual and non-violent way of applying force, but South Africa's major trading partners once more voted against mandatory sanctions. In 1962, the UN General Assembly requested that its members split political, fiscal and transportation connections with South Africa. In 1968, it suggested the deferral of all cultural, didactic and sporting commerce as well. From 1964, the US and Britain discontinued their dealings of armaments to South Africa. In spite of the many cries for sanctions, however, none were made obligatory, because South Africa's main trading partners were again primarily concerned for their own financial security.

In 1977, the voluntary UN arms embargo

An arms embargo is a restriction or a set of sanctions that applies either solely to weaponry or also to " dual-use technology." An arms embargo may serve one or more purposes:

* to signal disapproval of the behavior of a certain actor

* to maintai ...

became mandatory with the passing of United Nations Security Council Resolution 418

United Nations Security Council Resolution 418, adopted unanimously on 4 November 1977, imposed a mandatory arms embargo against South Africa. This resolution differed from the earlier Resolution 282, which was only voluntary. The embargo was ...

.

An oil embargo was introduced on 20 November 1987 when the United Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Curr ...

adopted a voluntary international oil

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) & lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturated ...

embargo

Economic sanctions are commercial and financial penalties applied by one or more countries against a targeted self-governing state, group, or individual. Economic sanctions are not necessarily imposed because of economic circumstances—they m ...

.

Aid to apartheid casualties

Another way in which the UN could do something to combat apartheid was to lend support and aid to its victims. In 1963, the General Assembly passed a decree requesting that members contribute financially towards assisting apartheid sufferers.Lusaka Manifesto

The Organisation for African Unity (OAU) was created in 1963. Its primary objectives were to eradicate colonialism and improve social, political and economic situations in Africa. It censured apartheid and demanded sanctions against South Africa. African states swore to aid the freedom movements in their fights against apartheid. In April 1969, fourteen autonomous nations fromCentral

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known a ...

and East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territories make up Eastern Africa:

Due to the historica ...

gathered in Lusaka

Lusaka (; ) is the capital and largest city of Zambia. It is one of the fastest-developing cities in southern Africa. Lusaka is in the southern part of the central plateau at an elevation of about . , the city's population was about 3.3 millio ...

, Zambia

Zambia (), officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central, Southern and East Africa, although it is typically referred to as being in Southern Africa at its most central point. Its neighbours are t ...

, to argue about various African matters. The assembly formulated the 'Lusaka Manifesto', which was signed on 13 April by all of the countries in attendance, except for Malawi

Malawi (; or aláwi Tumbuka: ''Malaŵi''), officially the Republic of Malawi, is a landlocked country in Southeastern Africa that was formerly known as Nyasaland. It is bordered by Zambia to the west, Tanzania to the north and northe ...

. This manifesto was later taken on by both the OAU and the United Nations.

The Lusaka Manifesto summarised the political situations of self-governing African countries, snubbing racism and inequity, and calling for black majority rule in all African nations. It did not rebuff South Africa entirely, though, adopting an appeasing manner towards the apartheid government, and even recognising its autonomy. Although African principals desired the emancipation of black South Africans, they trusted in their abilities to attain this in peaceable ways, intercession instead of militancy. The manifesto's signatories did not want to engage in a military war by supporting the liberation pugilists, because, for one thing, they could ill afford it and, for another, they dreaded retaliation.

Morogoro Conference

Neither the ANC nor the PAC was content with the Lusaka Manifesto. The signatories had not checked with them before laying out the document, and they foresaw the fact that African backing for the struggle would taper. The Manifesto did not truly recognise the significance of the liberation groups in the answer to South Africa's problems and even proposed dissuading them from an armed struggle. Both the ANC and the PAC had started using violent means in the 1960s, with the formation of their military wings. Disinclined to destroy the support that they did have, however, the ANC and PAC did not explicitly condemn the Manifesto. In 1969, though, the ANC held the inaugural National Consultative Conference inMorogoro

Morogoro is a city in the eastern part of Tanzania west of Dar es Salaam. Morogoro is the capital of the Morogoro Region.

It is also known informally as "Mji kasoro bahari" which translates to “city short of an ocean/port." The Belgian based ...

, Tanzania, where it ironed out its troubles and anxieties. The result was a decision not to end the armed struggle but, rather, to advance it. Oliver Tambo summed up thus: "Close Ranks! This is the order to our people, our youth, the army, to each Umkhonto we Sizwe militant, to all our many supporters the world over. This is the order to our leaders, to all of us. The order that comes from this conference is 'Close Ranks and Intensify the Armed Struggle!'"

Unlike the independence factions, the South African administration hailed the Lusaka Manifesto's plans for arbitration and détente. This tied in nicely with Prime Minister Vorster's own plan for the reduction of South Africa's seclusion from the rest of the world. He called his "Outward looking" policy. The state also maintained that the preservation of separate development through homelands carried out the Manifesto's insistence on human equality and dignity. The homelands, it argued, were meant eventually to be self-governing, decolonised nations where black people could take part in ballots and be free to live how they wished.

That is not to say that the NP government ''agreed'' to the Lusaka Manifesto, however. It rejected the manifesto's backing of liberation movements, although the movements themselves felt the Manifesto was showing a ''lack'' of support.

Mogadishu Declaration

South Africa's negative response to the Lusaka Manifesto and rejection of a change to its policies brought about another OAU announcement in 1971. The Mogadishu Declaration declared that "there is no way left to the liberation of Southern Africa except armed struggle", and condemned African states which maintained diplomatic and other relations with South Africa. Henceforth, it would be up to South Africa to keep contact with other African states.Outward-Looking Policy

In 1966,BJ Vorster

Balthazar Johannes "B. J." Vorster (; also known as John Vorster; 13 December 1915 – 10 September 1983) was a South African apartheid politician who served as the prime minister of South Africa from 1966 to 1978 and the fourth state presiden ...

was made South African Prime Minister. He was not about to eliminate apartheid, but he did try to redress South Africa's seclusion and the purported larger mentality. He wanted to perk up the country's global reputation and overseas dealings, even those with black-ruled nations in Africa. This he called his "Outward-Looking" policy: South Africa would look outwards, towards the global neighbourhood, rather than adopting a siege mentality and estranging it. The buzzwords for his strategy were "dialogue" and "détente", signifying arbitration and reduction of pressure.

Western ties

The "Outward Looking" principle had a significant consequence for South Africa's relationships with Western nations. When Vorster brought forth his strategy, it appeared to them that South Africa might be loosening its grip. At the same time, the West regarded the apartheid administration as a significant friend in theCold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

. Economically, such nations as Britain and America had numerous concerns in South Africa, and, although they did not endorse apartheid, these concerns led them to a more moderate stance on the country and to vote against financial sanctions at UN conferences.

United Kingdom

When South Africa pulled out of theCommonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

in 1961, the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

led resistance to calls for punitive monetary and trade sanctions. It had many key economic links and, in particular, benefited from trade with South Africa's gold mining industry.

There were also strategic motives for not severing all ties with the apartheid government. As the southernmost nation in Africa, and the juncture of the Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

and Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

s, South Africa was still a vital point in sea-trade routes. In 1969, the Commandant General of the South African Defence Force

The South African Defence Force (SADF) (Afrikaans: ''Suid-Afrikaanse Weermag'') comprised the armed forces of South Africa from 1957 until 1994. Shortly before the state reconstituted itself as a republic in 1961, the former Union Defence F ...

(SADF) confirmed that, " the entire ocean expanse from Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

to South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sou ...

, South Africa is the only fixed point offering modern naval bases, harbours and airfield facilities, a modern developed industry and stable government." South Africa was also a pivotal partner to the West in the years of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

. If the West ever required martial, maritime or air-force services on the African continent, it would have to rely on South Africa's assistance.

From 1960 to 1961, the relationship between South Africa and Britain started to change. In his " Wind of Change" speech in Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

, Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986) was a British Conservative statesman and politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Caricatured as " Supermac", ...

spoke of the changes in Africa and how South Africa's racist policies were swimming upstream. Even as more countries added to the call for sanctions, Britain remained unwilling to sever ties with the apartheid administration. Possible reasons were its copious assets in the state, an unwillingness to hazard turbulence brought on by intercontinental meddling, and the fact that many British people had kith and kin living in South Africa or, indeed, were living there themselves. Along with America, Britain would persistently vote against certain sanctions against South Africa.

However, there was significant and notable resistance to apartheid within the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

, such as the Anti-Apartheid Movement

The Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM), was a British organisation that was at the centre of the international movement opposing the South African apartheid system and supporting South Africa's non-White population who were persecuted by the policie ...

. '' London Recruits: The Secret War Against Apartheid'' is a 2012 book documenting assistance given to the ANC from activists in the UK. In 1995, during his official state visit to the UK, Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (; ; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African anti-apartheid activist who served as the first president of South Africa from 1994 to 1999. He was the country's first black head of state and the ...

appeared on the balcony of High Commission of South Africa, London

The High Commission of South Africa in London is the diplomatic mission from South Africa to the United Kingdom. It is located at South Africa House, a building on Trafalgar Square, London. As well as containing the offices of the High Com ...

to thank supporters in the UK. The High Commission had been a constant target of protests during apartheid.

South Africa rejoined the Commonwealth in 1994, albeit, as a republic in the Commonwealth of Nations

The republics in the Commonwealth of Nations are the sovereign states in the organisation with a republican form of government. , 36 out of the 56 member states were republics. Charles III, who is the reigning monarch in the Commonwealth realms ...

and not a realm

A realm is a community or territory over which a sovereign rules. The term is commonly used to describe a monarchical or dynastic state. A realm may also be a subdivision within an empire, if it has its own monarch, e.g. the German Empire.

Et ...

.

United States

At the outset of apartheid, the United States avoided serious criticism of South Africa's racial policies in part because severalU.S. state

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its sove ...

s, especially in the Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion in the Southern United States. The term was first used to describe the states most dependent on plantations and slavery prior to the American Civil War. Following the wa ...

, had similar policies under the Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the S ...

. Following the 1960 Sharpeville massacre, however, the country voted at the UN conference against it. The US impressed a severe armament embargo on South Africa from 1964, and, from 1967, the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

avoided South African harbors. Unlike Britain, the USA did not see much importance in the Cape route

The European-Asian sea route, commonly known as the sea route to India or the Cape Route, is a shipping route from the European coast of the Atlantic Ocean to Asia's coast of the Indian Ocean passing by the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Agulhas ...

, but they did see the economic opportunities for South African investment. Imports and exports between the two states came to many millions of dollars. Financial ties aside, there were also numerous cultural links between South Africa and the United States. South Africans of all races were given the chance to study in the US with scholarships. The US even utilised South Africa for its exploration of outer space, setting up a satellite tracking post near Krugersdorp

Krugersdorp (Afrikaans for ''Kruger's Town'') is a mining city in the West Rand, Gauteng Province, South Africa founded in 1887 by Marthinus Pretorius. Following the discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand, a need arose for a major town in the west ...

, and building numerous telescopes for lunar probes. This picked up ailing ties between the two countries, but, in the 1970s, the United States withdrew from the tracking station.

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

and Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presid ...

had adopted a policy known as the Tar Baby Option, according to which the US ought to maintain close relations with the Apartheid government of South Africa. The United States also increased trade with the country, while describing the ANC as "a terrorist organisation." The Reagan administration

Ronald Reagan's tenure as the 40th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1981, and ended on January 20, 1989. Reagan, a Republican from California, took office following a landslide victory over ...

evaded international sanctions against South Africa and vetoed the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act

The Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986 was a law enacted by the United States Congress. The law imposed sanctions against South Africa and stated five preconditions for lifting the sanctions that would essentially end the system of apart ...

, which mandated compliance with the sanctions, but Congress in 1986 overruled the veto despite some Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

opposition. The U.S. also provided diplomatic support to the South African government in international forums.

As fiscal ties between South Africa, the United States and the United Kingdom were reinforced, however, sporting and cultural boycotts became important gadgets in South Africa's isolation from international society. The arms prohibition obliged South Africa to look elsewhere (particularly France) for its artillery, build up its own technology and manufacture weapons itself. At first, the Cold War had little influence on the connection between the West and South Africa: the US believed that the armament embargo would not put up a barrier between them. If a major quarrel broke out in Africa, South Africa would be forced to work with the US anyway.

Israel

Relations between the

Relations between the State of Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

and the Union of South Africa were established as early as 1948, the Nationalist Prime Minister Daniel François Malan

Daniël François Malan (; 22 May 1874 – 7 February 1959) was a South African politician who served as the fourth prime minister of South Africa from 1948 to 1954. The National Party implemented the system of apartheid, which enforce ...

paying a visit to Israel and ignoring the clearly antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Ant ...

profile his own party earned during the 1930s and by its opposition to joining in the Anti-Hitlerite coalition in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. In 1963, Israel imposed an arms embargo

An arms embargo is a restriction or a set of sanctions that applies either solely to weaponry or also to " dual-use technology." An arms embargo may serve one or more purposes:

* to signal disapproval of the behavior of a certain actor

* to maintai ...

in compliance with United Nations Security Council Resolution 181

United Nations Security Council Resolution 181, adopted on August 7, 1963, was concerned with an arms build-up by the Republic of South Africa and fears that those arms might be used to further the racial conflict in that country. The Counci ...

, and recalled its ambassador. During this period, Israel contributed an annual $7,000,000 in medical, agricultural, and other aid to Sub-Saharan states.

After the 1967 Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab states (primarily Egypt, Syria, and Jordan) from 5 to 10 ...

Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

n nations cut off diplomatic relations with Israel, and the latter became Pretoria's strategic partner, establishing strong economic and military relations with the 1975 Israel–South Africa Agreement, which included alleged nuclear collaboration.

Other African states

Vorster's attitude towards other African countries was not so much a modification of strategy as a continuance of Verwoerd's approach. Vorster's forerunner had already become aware of the fact that cordial dealings with as many black states as possible was of paramount importance. As more and more African states acquired statehood from their colonial rulers, and as the Portuguese hold over neighboringMozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

and Angola

, national_anthem = "Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordinat ...

weakened, bitterness towards the South African apartheid system increased. If South Africa did not wish to become completely cut off from the rest of the African continent, she had to sustain associations with it, starting, of course, with mutual economic support. Vorster persisted with this strategy and built good relationships with a number of independent African states.

In 1967, Vorster proffered technological and fiscal counsel gratis to any African state prepared to receive it, asserting that absolutely no political strings were attached. He gave great attention to financial facets, aware of the fact that many African states were very run-down and would require financial aid in spite of their rebuffing of South Africa's racial principles. Malawi

Malawi (; or aláwi Tumbuka: ''Malaŵi''), officially the Republic of Malawi, is a landlocked country in Southeastern Africa that was formerly known as Nyasaland. It is bordered by Zambia to the west, Tanzania to the north and northe ...

and Lesotho

Lesotho ( ), officially the Kingdom of Lesotho, is a country landlocked as an enclave in South Africa. It is situated in the Maloti Mountains and contains the highest mountains in Southern Africa. It has an area of over and has a population ...

were the first countries to enter discussions with the NP government.

One of the first steps to take in initiating dealings was to convene with the heads of these African countries. Here Vorster worked decidedly contrary to Verwoerd's policies. Where Verwoerd had declined to get together and engage in dialogue with such leaders as Abubakar Tafawa Balewa

Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa (December 1912 – 15 January 1966) was a Nigerian politician who served as the first and only Prime Minister of Nigeria upon independence.

Early life

Abubakar Tafawa Balewa was born in December 1912 in modern-day ...

of Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

in 1962 and Kenneth Kaunda

Kenneth David Kaunda (28 April 1924 – 17 June 2021), also known as KK, was a Zambian politician who served as the first President of Zambia from 1964 to 1991. He was at the forefront of the struggle for independence from British rule. Diss ...

of Zambia

Zambia (), officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central, Southern and East Africa, although it is typically referred to as being in Southern Africa at its most central point. Its neighbours are t ...

in 1964, Vorster, in 1966, met with the heads of the states of Lesotho, Swaziland and Botswana. There was still mutual suspicion, however, particularly after Vorster's denunciation of the Lusaka Manifesto in 1969. Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland stayed candid critics of apartheid, but they hinged on South Africa's economic aid. This was inclusive of pecuniary credit and the fact that many natives from these states worked the South African mines.

Malawi was the first country not on South African borders to accept South African aid. She identified the monetary benefits of such a deal, for there were also many Malawians working in South African mines. In 1967, the two states delineated their political and economic relations, and, in 1969, Malawi became the only country at the assembly which did not sign the Lusaka Manifesto. In 1970, Malawian President Hastings Banda

Hastings Kamuzu Banda (1898 – 25 November 1997) was the prime minister and later president of Malawi from 1964 to 1994 (from 1964 to 1966, Malawi was an independent Dominion / Commonwealth realm).

In 1966, the country became a republic and ...

made his first and most successful official stopover in South Africa.

Associations with Mozambique followed suit and were sustained after that country won its sovereignty in 1975. Angola was also granted South African loans. Other countries which formed relationships with South Africa were Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to Guinea–Liberia border, its north, Ivory Coast to Ivory Coast� ...

, Côte d'Ivoire

Ivory Coast, also known as Côte d'Ivoire, officially the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire, is a country on the southern coast of West Africa. Its capital is Yamoussoukro, in the centre of the country, while its largest city and economic centre ...

, Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Afric ...

, Mauritius

Mauritius ( ; french: Maurice, link=no ; mfe, label= Mauritian Creole, Moris ), officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island nation in the Indian Ocean about off the southeast coast of the African continent, east of Madagascar. It ...

, Gabon

Gabon (; ; snq, Ngabu), officially the Gabonese Republic (french: République gabonaise), is a country on the west coast of Central Africa. Located on the equator, it is bordered by Equatorial Guinea to the northwest, Cameroon to the nort ...

, Zaire

Zaire (, ), officially the Republic of Zaire (french: République du Zaïre, link=no, ), was a Congolese state from 1971 to 1997 in Central Africa that was previously and is now again known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Zaire was, ...

(now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and Tog ...

and the Central African Republic

The Central African Republic (CAR; ; , RCA; , or , ) is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Chad to the north, Sudan to the northeast, South Sudan to the southeast, the DR Congo to the south, the Republic of th ...

. These African states criticised apartheid (more than ever after South Africa's denunciation of the Lusaka Manifesto), but fiscal reliance on South Africa, together with fear of its military power, resulted in their forming the aforementioned ties.

Effect of the Soweto uprising

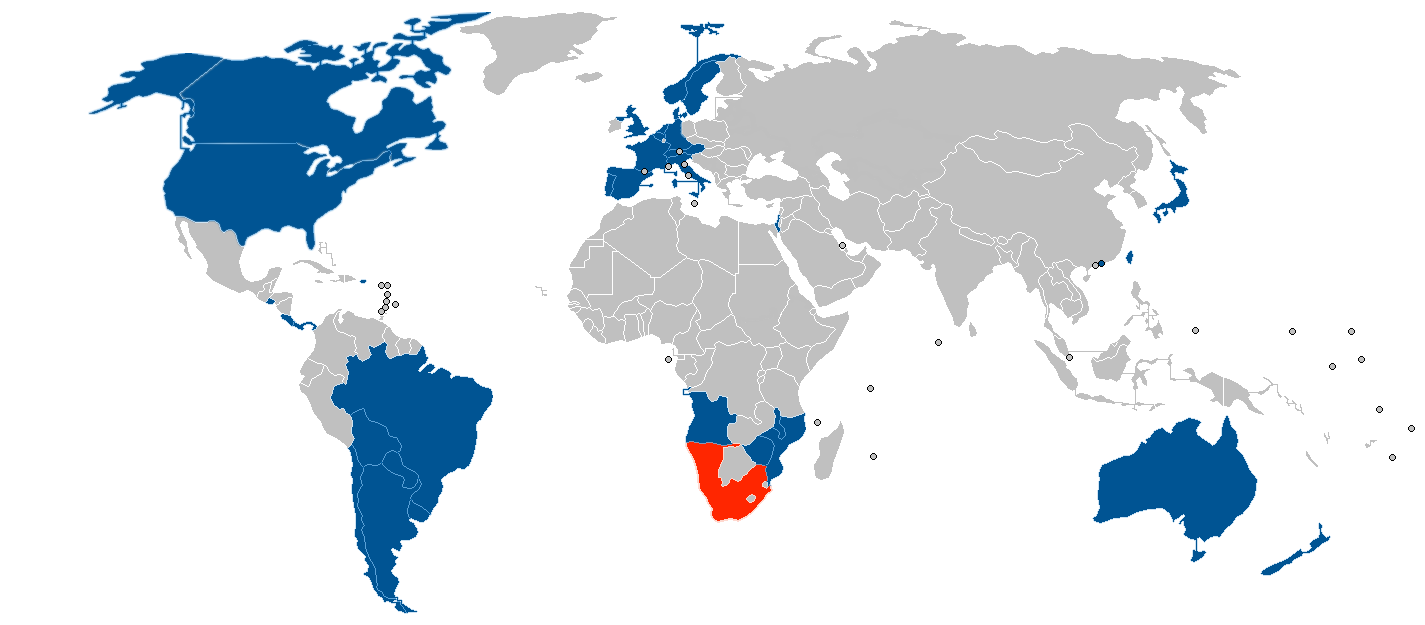

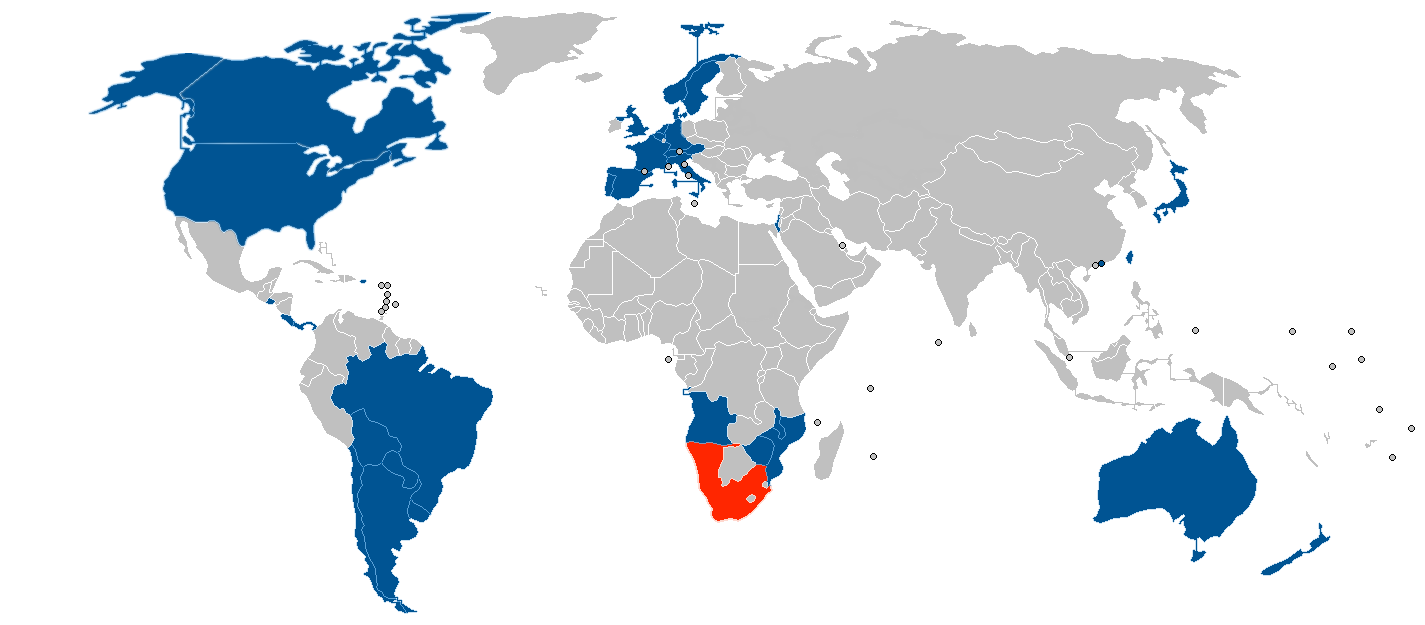

Following the Soweto uprising in 1976 and its brutal suppression by the apartheid regime, the arms embargo was made mandatory by the UN Security Council on 4 November 1977 and South Africa became increasingly isolated internationally, with tough economic sanctions weighing heavily. Not all countries imposed or fully supported the sanctions, however; instead, they continued to benefit from trade with apartheid South Africa. During the 1980s, though, the number of countries opposing South Africa increased, and the economy came under tremendous strain.Isolation

While some countries and organizations, like the Swiss-South African Association, supported the Apartheid government, most of the international community isolated South Africa. One of the primary means for the international community to show its aversion to apartheid was to

While some countries and organizations, like the Swiss-South African Association, supported the Apartheid government, most of the international community isolated South Africa. One of the primary means for the international community to show its aversion to apartheid was to boycott

A boycott is an act of nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organization, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for moral, social, political, or environmental reasons. The purpose of a boycott is to inflict so ...

South Africa in a variety of spheres of multinational life. Economic and military sanctions were among these, but cultural and sporting boycotts also found their way in. South Africa, in this way, was cut off from the rest of the globe. It also awakened the South African community to the opinions of other countries. Despite financial shunning causing significant harm to Black South Africans

Racial groups in South Africa have a variety of origins. The racial categories introduced by Apartheid remain ingrained in South African society with South Africans and the South African government continuing to classify themselves, and each o ...

, the ANC proclaimed it as an essential means of achieving liberty. Cultural and sporting boycotts, on the other hand, did not have a negative effect on the lives of black people, as they were already barred from these by their own government.

Sports boycotts

Sporting seclusion commenced in the mid-1950s and increased through the 1960s. Apartheid forbade multiracial sport, which meant that overseas teams, by virtue of their having players of diverse races, could not play in South Africa. In 1956, theInternational Table Tennis Federation

The International Table Tennis Federation (ITTF) is the governing body for all national table tennis associations. The role of the ITTF includes overseeing rules and regulations and seeking technological improvement for the sport of table ten ...

severed its ties with the all-white South African Table Tennis Union, preferring the non-racial South African Table Tennis Board in its stead. The apartheid government came back by confiscating the passports of the Board's players so that they were unable to attend international games. Other global sports unions followed the example, but they were sluggish in doing so.

In 1959, the non-racial South African Sports Association (SASA) was shaped to secure the rights of all players on the global field. After meeting with no success in its endeavours to attain credit by collaborating with white establishments, SASA went to the International Olympic Committee

The International Olympic Committee (IOC; french: link=no, Comité international olympique, ''CIO'') is a non-governmental sports organisation based in Lausanne, Switzerland. It is constituted in the form of an association under the Swis ...

(IOC) in 1962, calling for South Africa's eviction from the Olympic Games

The modern Olympic Games or Olympics (french: link=no, Jeux olympiques) are the leading international sporting events featuring summer and winter sports competitions in which thousands of athletes from around the world participate in a multi ...

. The IOC sent South Africa a caution to the effect that, if there were no changes, it would be barred from the 1964 games. The changes were initiated, and in January 1963, the South African Non-Racial Olympic Committee (SANROC) was set up. The Anti-Apartheid Movement persisted in its campaign for South Africa's exclusion, and the IOC acceded in barring the country from the 1964 Games in Tokyo. South Africa selected a multi-racial side for the next Games, and the IOC opted to include the country in the 1968 Games in Mexico. Because of protests from AAMs and African nations, however, the IOC was forced to retract the invitation, along with one for Rhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' successor state to the British colony of So ...

.

Foreign complaints about South Africa's bigoted sports brought more isolation. In 1960, Verwoerd barred a Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the Co ...

rugby

Rugby may refer to:

Sport

* Rugby football in many forms:

** Rugby league: 13 players per side

*** Masters Rugby League

*** Mod league

*** Rugby league nines

*** Rugby league sevens

*** Touch (sport)

*** Wheelchair rugby league

** Rugby union: 1 ...

player from touring South Africa with the All Blacks

The New Zealand national rugby union team, commonly known as the All Blacks ( mi, Ōpango), represents New Zealand in men's international rugby union, which is considered the country's national sport. The team won the Rugby World Cup in 1987, ...

, and the tour was cancelled. New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

made a decision not to convey an authorised rugby team to South Africa again.

B. J. Vorster

Balthazar Johannes "B. J." Vorster (; also known as John Vorster; 13 December 1915 – 10 September 1983) was a South African apartheid politician who served as the prime minister of South Africa from 1966 to 1978 and the fourth state presiden ...

took Verwoerd's place as PM in 1966 and declared that South Africa would no longer dictate to other countries what their teams should look like. Although this reopened the gate for sporting meets, it did not signal the end of South Africa's racist sporting policies. In 1968, Vorster went against his policy by refusing to permit Basil D'Oliveira

Basil Lewis D'Oliveira CBE OIS (4 October 1931 – 19 November 2011) was an England international cricketer of South African Cape Coloured background, whose potential selection by England for the scheduled 1968–69 tour of apartheid-era South ...

, a Coloured

Coloureds ( af, Kleurlinge or , ) refers to members of multiracial ethnic communities in Southern Africa who may have ancestry from more than one of the various populations inhabiting the region, including African, European, and Asian. South ...

South African-born cricketer, to join the English cricket team on its tour to South Africa. Vorster said that the side had been chosen only to prove a point, and not on merit. After protests, however, "Dolly" was eventually included in the team; see the D'Oliveira affair. Protests against certain tours brought about the cancellation of a number of other visits, like that of an England rugby team in 1969/70.

As sporting segregation persisted, it became obvious that South Africa would have to make further changes to its sporting policies if it was to be recognised on the international stage. More and more careers were impinged upon by segregation, and they began to stand up against apartheid. In 1971, Vorster altered his policies even further by distinguishing multiracial from multinational sport. Multiracial sport, between teams with players of different races, remained outlawed; multinational sport, however, was now acceptable: international sides would not be subject to South Africa's racial stipulations.

International censure of segregated sport and calls for sporting sanctions persisted. The UN would continue to hold them against South Africa until the end of apartheid. These measures did not bring an end to international sport for South African teams, but they added very much to the country's seclusion. The bans were revoked in 1993, when conciliations for a democratic South Africa were well under way.

Cultural boycotts

In the 1960s, theAnti-Apartheid Movement

The Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM), was a British organisation that was at the centre of the international movement opposing the South African apartheid system and supporting South Africa's non-White population who were persecuted by the policie ...

worldwide began to campaign for ''cultural'' boycotts of apartheid South Africa. Artists were requested not to present or let their works be hosted in South Africa. In 1963, 45 British writers put their signatures to an affirmation approving of the boycott, and, in 1964, American actor Marlon Brando

Marlon Brando Jr. (April 3, 1924 – July 1, 2004) was an American actor. Considered one of the most influential actors of the 20th century, he received numerous accolades throughout his career, which spanned six decades, including two Academ ...

called for a similar affirmation for films. In 1965, the Writers' Guild of Great Britain

The Writers' Guild of Great Britain (WGGB), established in 1959, is a trade union for professional writers. It is affiliated with both the Trades Union Congress (TUC) and the International Affiliation of Writers Guilds (IAWG).

History

The un ...

called for a proscription on the sending of films to South Africa. Over sixty American artists signed a statement against apartheid and against professional links with the state. The presentation of some South African plays in Britain and America was also vetoed. After the arrival of television

Television, sometimes shortened to TV, is a telecommunication medium for transmitting moving images and sound. The term can refer to a television set, or the medium of television transmission. Television is a mass medium for advertising, ...

in South Africa in 1975, the British Actors Union, Equity

Equity may refer to:

Finance, accounting and ownership

*Equity (finance), ownership of assets that have liabilities attached to them

** Stock, equity based on original contributions of cash or other value to a business

** Home equity, the diff ...

, boycotted the service, and no British program concerning its associates could be sold to South Africa. Sporting and cultural boycotts did not have the same impact as economic sanctions, but they did much to lift consciousness amongst normal South Africans of the global condemnation of apartheid.

These facets of social remoteness from the worldwide hamlet made apartheid a discomfiture and were most trying for sports and culture fans. These boycotts effectively egged on little changes to apartheid policy, and corroded white South Africans' dedication to it.

Political isolation and economic boycotts

Numerous conferences were held and the United Nations passed resolutions condemning South Africa, including theWorld Conference Against Racism

The World Conference Against Racism (WCAR) is a series of international events organized by UNESCO to promote struggle against racism ideologies and behaviours. Five conferences have been held so far, in 1978, 1983, 2001, 2009 and 2021. Founded ...

in 1978 and 1983. A significant divestment movement started, pressuring investors to refuse to invest in South African companies or companies that did business with South Africa. South African sports teams were barred from participation in international events, and South African culture and tourism were boycott

A boycott is an act of nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organization, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for moral, social, political, or environmental reasons. The purpose of a boycott is to inflict so ...

ed.

Countries such as Zambia, Tanzania and the Soviet Union provided military support for the ANC and PAC. It was more difficult, though, for neighbouring states such as Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland, because they were economically dependent on South Africa. Still, they did feed the struggle underground.

Ordinary people in foreign countries did much in protest against the apartheid government, too. The British Anti-Apartheid Movement was one of these, organising boycotts against South African sports teams, South African products such as wine and fruit, and British companies that traded with or in South Africa. Other organisations were formed to prevent musicians and the like from coming into the country, and others raised funds for the ANC and PAC.

After much debate, by the late 1980s the United States, the United Kingdom, and 23 other nations had passed laws placing various trade sanctions on South Africa. A divestment

In finance and economics, divestment or divestiture is the reduction of some kind of asset for financial, ethical, or political objectives or sale of an existing business by a firm. A divestment is the opposite of an investment. Divestiture is ...

movement in many countries was similarly widespread, with individual cities and provinces around the world implementing various laws and local regulations forbidding registered corporations under their jurisdiction from doing business with South African firms, factories, or banks.

In an analysis of the effect of sanctions on South Africa by the FW de Klerk Foundation

The FW de Klerk Foundation is a nonpartisan organisation that was established in 1999 by former South African president Frederik Willem de Klerk.

It promotes activities in "multi-community" countries and seeks to nurture the democracy of South A ...

, it was argued that they were not a leading contributor to the political reforms leading to the end of Apartheid. The analysis concluded that in many instances sanctions undermined effective reform forces, such as the changing economic and social order within South Africa. Furthermore, it was argued that forces encouraging economic growth and development resulted in a more international and liberal outlook amongst South Africans, and were far more powerful agents of reform than sanctions.

Western influence in anti-apartheid movement

While international opposition to apartheid grew, the

While international opposition to apartheid grew, the Nordic countries

The Nordic countries (also known as the Nordics or ''Norden''; lit. 'the North') are a geographical and cultural region in Northern Europe and the North Atlantic. It includes the sovereign states of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sw ...

in particular provided both moral and financial support for the ANC. On 21 February 1986– a week before he was murdered– Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic countries, Nordic c ...

's prime minister Olof Palme

Sven Olof Joachim Palme (; ; 30 January 1927 – 28 February 1986) was a Swedish politician and statesman who served as Prime Minister of Sweden from 1969 to 1976 and 1982 to 1986. Palme led the Swedish Social Democratic Party from 1969 until ...

made the keynote

A keynote in public speaking is a talk that establishes a main underlying theme. In corporate or commercial settings, greater importance is attached to the delivery of a keynote speech or keynote address. The keynote establishes the framework fo ...

address to the ''Swedish People's Parliament Against Apartheid'' held in Stockholm

Stockholm () is the capital and largest city of Sweden as well as the largest urban area in Scandinavia. Approximately 980,000 people live in the municipality, with 1.6 million in the urban area, and 2.4 million in the metropo ...

. In addressing the hundreds of anti-apartheid sympathisers as well as leaders and officials from the ANC and the Anti-Apartheid Movement

The Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM), was a British organisation that was at the centre of the international movement opposing the South African apartheid system and supporting South Africa's non-White population who were persecuted by the policie ...

such as Oliver Tambo

Oliver Reginald Kaizana Tambo (27 October 191724 April 1993) was a South African anti-apartheid politician and revolutionary who served as President of the African National Congress (ANC) from 1967 to 1991.

Biography

Higher education

Oliv ...

, Palme said Apartheid needed to be abolished, not reformed.

Other Western countries adopted a more ambivalent position. In the 1980s, both the Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

and Thatcher administrations in the US and UK followed a 'constructive engagement

Constructive engagement was the name given to the conciliatory foreign policy of the Reagan administration towards the apartheid regime in South Africa. Devised by Chester Crocker, Reagan's U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for African Affair ...

' policy with the apartheid government, vetoing the imposition of UN economic sanctions on South Africa, as they both fiercely believed in free trade and saw South Africa as a bastion against Marxist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialecti ...

forces in Southern Africa. Thatcher declared the ANC a terrorist organisation, and in 1987 her spokesman, Bernard Ingham, said that anyone who believed that the ANC would ever form the government of South Africa was "living in cloud cuckoo land".

By the late 1980s, however, with the tide of the Cold War turning and no sign of a political resolution in South Africa, Western patience with the apartheid government began to run out. By 1989, a bipartisan Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

/ Democratic initiative in the US favoured economic sanctions

Economic sanctions are commercial and financial penalties applied by one or more countries against a targeted self-governing state, group, or individual. Economic sanctions are not necessarily imposed because of economic circumstances—they ...

(realised as the ''Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act

The Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986 was a law enacted by the United States Congress. The law imposed sanctions against South Africa and stated five preconditions for lifting the sanctions that would essentially end the system of apart ...

''), the release of Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (; ; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African anti-apartheid activist who served as the first president of South Africa from 1994 to 1999. He was the country's first black head of state and the ...

and a negotiated settlement involving the ANC. Thatcher too began to take a similar line, but insisted on the suspension of the ANC's armed struggle.

South West Africa

Separate from the issue of apartheid was a major quarrel between the UN and South Africa about the management ofSouth West Africa

South West Africa ( af, Suidwes-Afrika; german: Südwestafrika; nl, Zuidwest-Afrika) was a territory under South African administration from 1915 to 1990, after which it became modern-day Namibia. It bordered Angola (Portuguese colony before 1 ...

. After World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, all German colonies were made mandates of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

, the UN's forbearer. Direction of these mandates was allotted to certain countries. The Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

declared German South West Africa

German South West Africa (german: Deutsch-Südwestafrika) was a colony of the German Empire from 1884 until 1915, though Germany did not officially recognise its loss of this territory until the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. With a total area of ...

a League of Nations Mandate

A League of Nations mandate was a legal status for certain territories transferred from the control of one country to another following World War I, or the legal instruments that contained the internationally agreed-upon terms for administ ...

under South African administration, and it then became known as South West Africa

South West Africa ( af, Suidwes-Afrika; german: Südwestafrika; nl, Zuidwest-Afrika) was a territory under South African administration from 1915 to 1990, after which it became modern-day Namibia. It bordered Angola (Portuguese colony before 1 ...

.

Walvis Bay

Walvis Bay ( en, lit. Whale Bay; af, Walvisbaai; ger, Walfischbucht or Walfischbai) is a city in Namibia and the name of the bay on which it lies. It is the second largest city in Namibia and the largest coastal city in the country. The ci ...

was annexed by the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

in 1878 and incorporated into the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with ...

in 1884. It thus became part of the Union of South Africa in 1910. In 1915 the Union occupied German South West Africa at the request of the Allied powers. South Africa was granted a "C" Class mandate by the League of Nations to administer this former German colony as an integral part of South Africa. The South African government transferred administration of Walvis Bay to South West Africa in 1922 but would in 1977 transfer it back to Cape Province.

After the configuration of the UN in 1945, and the transfer of mandates from the League of Nations to the new body, the arrangement changed: former obligatory powers (vis-à-vis those in charge of ex-German colonies) were now obliged to form new concurrences with the U.N. over their management of the mandates. South Africa, however, refused to play ball, declining to allow the territory to move towards independence. The National Party government argued that, for a quarter of a century, South-West Africa had been directed as a piece of South Africa, and the preponderance of South-West Africans wanted to become South Africans anyway. Instead, South-West Africa was treated as a ''de facto'' "fifth province" of the Union. The South African government turned this mandate arrangement into a military occupation, and extended apartheid to South-West Africa.

The UN attempted to compel South Africa to let go of the mandate, and, in 1960, Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to Guinea–Liberia border, its north, Ivory Coast to Ivory Coast� ...

and Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

requested that the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; french: Cour internationale de justice, links=no; ), sometimes known as the World Court, is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN). It settles disputes between states in accordan ...

announce that South Africa's management of South West Africa was illegitimate. They argued that South Africa was bringing apartheid to South-West Africa, too. South Africa was formally accused of maladministration, and the lawsuit, commencing in November 1960, lasted almost six years. The International Court's verdict astonished the UN: it ruled that Liberia and Ethiopia had no right to take issue with South Africa's deeds in South-West Africa. The Court did not, however, pass judgement on whether or not South Africa still had a mandate over the region. The UN declared that the mandate was indeed concluded, and a council of the UN was to run the state until its independence in 1968. South Africa rebuffed the resolution, but declared its ostensible intention to ready South-West Africa for independence.

Anxiety increased when the UN Council for South-West Africa was declined admission, and steepened still further when South Africa indicted 35 South-West Africans and then found them guilty of terror campaigns. The UN reproached South Africa and declared that South-West Africa would thenceforth be known as Namibia

Namibia (, ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and ea ...

. At the New York Accords in 1988, South Africa finally signed the agreement that granted the country its independence.

The UN allowed the South African government back in 1994, however the South African government had to first show that they had undertaken certain measures to get rid of the racial judgement. Soon after the South African government created the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was supposed to aid the transition from Apartheid to Democracy.

Border War

By 1966,SWAPO

The South West Africa People's Organisation (, SWAPO; af, Suidwes-Afrikaanse Volks Organisasie, SWAVO; german: Südwestafrikanische Volksorganisation, SWAVO), officially known as the SWAPO Party of Namibia, is a political party and former ind ...

launched guerilla raids from neighbouring countries against South Africa's occupation of South-West Africa/Namibia

Namibia (, ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and ea ...

. Initially South Africa fought a counter-insurgency war against SWAPO. But this conflict deepened after Angola

, national_anthem = "Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordinat ...

gained its independence in 1975 under Communist leadership, the MPLA

The People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola ( pt, Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola, abbr. MPLA), for some years called the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola – Labour Party (), is an Angolan left-wing, social dem ...

, and South Africa promptly challenged them, allying with the Angolan rival party, UNITA

The National Union for the Total Independence of Angola ( pt, União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola, abbr. UNITA) is the second-largest political party in Angola. Founded in 1966, UNITA fought alongside the Popular Movement for ...

. By the end of the 1970s, Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

had joined the fray, in one of several late Cold War flashpoints throughout Southern Africa. This developed into a conventional war between South Africa and UNITA on one side against the Angolan government, the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces

The Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces ( es, Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias; FAR) are the military forces of Cuba. They include ground forces, naval forces, air and air defence forces, and other paramilitary bodies including the Territorial T ...

, the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, and SWAPO on the other side.

Total onslaught

By 1980, as international opinion turned decisively against the apartheid regime, the government and much of the white population increasingly looked upon the country as abastion

A bastion or bulwark is a structure projecting outward from the curtain wall of a fortification, most commonly angular in shape and positioned at the corners of the fort. The fully developed bastion consists of two faces and two flanks, with fi ...

besieged by communism and radical black nationalists. Considerable effort was put into circumventing sanctions, and the government even went so far as to develop nuclear weapons

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

, allegedly with the help of Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...