Foley Square trial on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Smith Act trials of Communist Party leaders in New York City from 1949 to 1958 were the result of

After the

After the

available online

accessed June 13, 2012The Smith Act was officially called the Alien Registration Act of 1940

The Act has been amended since then

Text of 2012 version

The portion of the 1940 Act that was relevant to the CPUSA trials was: "Sec. 2. (a) It shall be unlawful for any person— (1) to knowingly or willfully advocate, abet, advise, or teach the duty, necessity, desirability, or propriety of overthrowing or destroying any government in the United States by force or violence, or by the assassination of any officer of any such government; (2) with the intent to cause the overthrow or destruction of any government in the United States, to print, publish, edit, issue, circulate, sell, distribute, or publicly display any written or printed matter advocating, advising, or teaching the duty, necessity, desirability, or propriety of overthrowing or destroying any government in the United States by force or violence. (3) to organize or help to organize any society, group, or assembly of persons who teach, advocate, or encourage the overthrow or destruction of any government in the United States by force or violence; or to be or become a member of, or affiliate with, any such society, group, or assembly of persons, knowing the purposes thereof...." Five million non-citizens were fingerprinted and registered following passage of the Act. The first persons convicted under the Smith Act were members of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) in

In July 1945, FBI director

In July 1945, FBI director

The 1949 trial was held in New York City at the Foley Square federal courthouse of the

The 1949 trial was held in New York City at the Foley Square federal courthouse of the

Sabin, p 41. Before becoming a judge, Medina successfully argued the case of '' Cramer v. United States'' before the Supreme Court, defending a German-American charged with treason. The trial opened on November 1, 1948, and preliminary proceedings and jury selection lasted until January 17, 1949; the defendants first appeared in court on March 7, and the case concluded on October 14, 1949.Morgan, p 315. Although later trials surpassed it, in 1949 it was the longest federal trial in US history. The trial was one of the country's most contentious legal proceedings and sometimes had a "circus-like atmosphere".Walker, p 185.

Morgan, p 315.

Sabin, pp 44–45. "Circus-like" are Sabin's words. Four hundred police officers were assigned to the site on the opening day of the trial. Magazines, newspapers, and radio reported on the case heavily; ''Time'' magazine featured the trial on its cover twice with stories titled "Communists: The Presence of Evil" and "Communists: The Little Commissar" (referring to Eugene Dennis)."Communists: The Little Commissar"

''Time'', April 25, 1949 (Cover photo: Eugene Dennis).

''Time'': October 24, 1949. (Cover photo: Harold Medina).

''Time'', (article, not cover), August 22, 1949.

''Time'', April 4, 1949.

See also ''Life'' magazine articles "Communist trial ends with 11 guilty", ''Life'', October 24, 1949, p 31; and "Unrepentant reds emerge", ''Life'', March 14, 1955, p 30.

, ''Life'', October 24, 1949, p 31. Defendant Eugene Dennis represented himself. The ACLU was dominated by anti-communist leaders during the 1940s, and did not enthusiastically support persons indicted under the Smith Act; but it did submit an ''amicus'' brief endorsing a motion for dismissal of the charges. The defense employed a three-pronged strategy: First, they sought to portray the CPUSA as a conventional political party, which promoted socialism by peaceful means; second, they attacked the trial as a capitalist venture which could never provide a fair outcome for proletarian defendants; and third, they used the trial as an opportunity to publicize CPUSA policies. The defense made pre-trial

Walker, p 185.

Starobin, p 206.

Medina's ruling on the jury selection issue i

83 F.Supp. 197 (1949)

The issue was addressed by the appeals court i

183 F.2d 201 (2d Cir. 1950)

The defense also argued that the jury selection process for the trial was similarly flawed.Belknap (1994), p 213. Their objections to the jury selection process were not successful and jurors included four African Americans and consisted primarily of working-class citizens.Belknap (1994), p 214. A primary theme of the defense was that the CPUSA sought to convert the US to socialism by education, not by force.Belknap (1994), p 219. The defense claimed that most of the prosecution's documentary evidence came from older texts that pre-dated the 1935 Seventh World Congress of the

During the ten-month trial, several events occurred in America that intensified the nation's

During the ten-month trial, several events occurred in America that intensified the nation's

Belknap (1994), p 221.

Redish, p 87.

One instruction from Medina to the jury was "I find as a matter of law that there is sufficient danger of a substantive evil that the Congress had a right to prevent, to justify the application of the statute under the First Amendment of the Constitution." After deliberating for seven and one-half hours, the jury returned guilty verdicts against all eleven defendants.Belknap (1994), p 221. The judge sentenced ten defendants to five years and a $10,000 fine each ($ in dollars). The eleventh defendant, Robert G. Thompsona veteran of World War IIwas sentenced to three years in consideration of his wartime service. Thompson said that he took "no pleasure that this Wall Street judicial flunky has seen fit to equate my possession of the

After the convictions, the Cold War continued in the international arena. In December 1950, Truman declared a national emergency in response to the Korean War. The

After the convictions, the Cold War continued in the international arena. In December 1950, Truman declared a national emergency in response to the Korean War. The

Kort, Michael, ''The Columbia Guide to the Cold War'', Columbia University Press, 2001, .

Walker, Martin, ''The Cold War: a History'', Macmillan, 1995, . Domestically, the Cold War was in the forefront of national consciousness. In February 1950, Senator

See also Fast, Howard, "The Big Finger", ''Masses & Mainstream'', March, 1950, pp 62–68. He testified that there were 21,105 potential persons that could be indicted under the Smith Act, and that 12,000 of those would be indicted if the Smith Act was upheld as constitutional. The FBI had compiled a list of 200,000 persons in its Communist Index; since the CPUSA had only around 32,000 members in 1950, the FBI explained the disparity by asserting that for every official Party member, there were ten persons who were loyal to the CPUSA and ready to carry out its orders. Seven months after the convictions, in May 1950, Hoover gave a radio address in which he declared "communists have been and are today at work within the very gates of America.... Wherever they may be, they have in common one diabolic ambition: to weaken and to eventually destroy American democracy by stealth and cunning." Other federal government agencies also worked to undermine organizations, such as the CPUSA, they considered subversive: The

Currie, David P., ''The Constitution in the Supreme Court: The Second Century, 1888–1986, Volume 2'', University of Chicago Press, 1994, p 269, .

Konvitz, Milton Ridvad, ''Fundamental Liberties of a Free People: Religion, Speech, Press, Assembly'', Transaction Publishers, 2003, p 304, .

Eastland, p 47. The Court continued to use the bad tendency test during the early twentieth century in cases such as 1919's '' Abrams v. United States'' which upheld the conviction of anti-war activists who passed out leaflets encouraging workers to impede the war effort. In ''Abrams'', Holmes and

Sabin, p 79 (Cold War in ''Dennis'' case).

The defendants appealed the Second Circuit's decision to the Supreme Court in ''

The defendants appealed the Second Circuit's decision to the Supreme Court in ''

Justia. Retrieved March 20, 2012. Vinson's opinion also addressed the contention that Medina's jury instructions were faulty. The defendants claimed that Medina's statement that "as matter of law that there is sufficient danger of a substantive evil that the Congress has a right to prevent to justify the application of the statute under the First Amendment of the Constitution" was erroneous, but Vinson concluded that the instructions were an appropriate interpretation of the Smith Act. The Supreme Court was, in one historian's words, "bitterly divided" on the

Retrieved March 20, 2012. The attorneys then appealed to the Supreme Court which denied the initial petition, but later reconsidered and accepted the appeal. The Supreme Court limited their review to the question, "was the charge of contempt, as and when certified, one which the accusing judge was authorized under Rule 42(a) to determine and punish himself; or was it one to be adjudged and punished under Rule 42(b) only by a judge other than the accusing one and after notice, hearing, and opportunity to defend?". The Supreme Court, in an opinion written by

After the 1949 convictions, prosecutors waited until the constitutional issues were settled by the Supreme Court before they tried additional leaders of the CPUSA. When the 1951 ''Dennis'' decision upholding the convictions was announced, prosecutors initiated indictments of 132 additional CPUSA leaders, called "second string" or "second-tier" defendants.Belknap (1994), p 225–226. The second-tier defendants were prosecuted in three waves: 1951, 1954, and 1956. Their trials were held in more than a dozen cities, including Los Angeles (15 CPUSA defendants, including Dorothy Healey, leader of the California branch of the CPUSA); New York (21 defendants, including National Committee members

After the 1949 convictions, prosecutors waited until the constitutional issues were settled by the Supreme Court before they tried additional leaders of the CPUSA. When the 1951 ''Dennis'' decision upholding the convictions was announced, prosecutors initiated indictments of 132 additional CPUSA leaders, called "second string" or "second-tier" defendants.Belknap (1994), p 225–226. The second-tier defendants were prosecuted in three waves: 1951, 1954, and 1956. Their trials were held in more than a dozen cities, including Los Angeles (15 CPUSA defendants, including Dorothy Healey, leader of the California branch of the CPUSA); New York (21 defendants, including National Committee members

The federal appeals courts upheld all convictions of second-tier officials. The Supreme Court refused to hear their appeals until 1956, when it agreed to hear the appeal of the California defendants; this led to the landmark ''

The federal appeals courts upheld all convictions of second-tier officials. The Supreme Court refused to hear their appeals until 1956, when it agreed to hear the appeal of the California defendants; this led to the landmark ''

Sabin, p 10.

Writing for the majority, Justice

Justia. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

The preceding federal appeals case, which upheld the conviction, was ''United States v. John Francis Noto'', 262 F.2d 501 (2d Cir. 1958) Noto was convicted under the membership clause of the Smith Act, and he challenged the constitutionality of that clause on appeal. The membership clause was in the portion of the Smith Act that made it a crime "to organize or help to organize any society, group, or assembly of persons who teach, advocate, or encourage the overthrow or destruction of any government in the United States by force or violence; or to be or become a member of, or affiliate with, any such society, group, or assembly of persons, knowing the purposes thereof ...". In a unanimous decision, the court reversed the conviction because the evidence presented at trial was not sufficient to demonstrate that the Party was advocating action (as opposed to mere doctrine) of forcible overthrow of the government.Konvitz, "Noto v. United States", p 697: "There must be substantial evidence, direct or circumstantial, of a call to violence 'now or in the future' that is both 'sufficiently strong and sufficiently persuasive' to lend color to the 'ambiguous theoretical material' regarding Communist party teaching ... and also substantial evidence to justify the reasonable inference that the call to violence may fairly be imputed to the party as a whole and not merely to a narrow segment of it." On behalf of the majority, Justice Harlan wrote: The decision did not rule the membership clause unconstitutional. In their concurring opinions, Justices Black and Douglas argued that the membership clause of the Smith Act was unconstitutional on its face as a violation of the First Amendment, with Douglas writing that "the utterances, attitudes, and associations in this case ... are, in my view, wholly protected by the First Amendment, and not subject to inquiry, examination, or prosecution by the Federal Government."

Oyez. Retrieved March 20, 2012. In 1961, the Supreme Court, in a 5–4 decision, upheld Scales' conviction, finding that the Smith Act membership clause was not obviated by the McCarran Act, because the Smith Act required prosecutors to prove first, that there was direct advocacy of violence; and second, that the defendant's membership was substantial and active, not merely passive or technical.Konvitz, "Scales v. United States", p 882: "Since the Communist party was considered an organization that engaged in criminal activity, the Court saw no constitutional obstacle to the prosecution of a person who actively and knowingly works in its ranks with intent to contribute to the success of its illegal objectives. Even though the evidence disclosed no advocacy for immediate overthrow of the government, the Court held that present advocacy of future action satisfied statutory and constitutional requirements no less than advocacy of immediate action." Two Justices of the Supreme Court who had supported the ''Yates'' decision in 1957, Harlan and Frankfurter, voted to uphold Scales' conviction. Scales was the only defendant convicted under the membership clause. All others were convicted of conspiring to overthrow the government.

The defendants at the 1949 trial were released from prison in the mid-1950s.

The defendants at the 1949 trial were released from prison in the mid-1950s.

US federal government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a f ...

prosecutions in the postwar period and during the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

between the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

and the United States. Leaders of the Communist Party of the United States

The Communist Party USA, officially the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), is a communist party in the United States which was established in 1919 after a split in the Socialist Party of America following the Russian Revo ...

(CPUSA) were accused of violating the Smith Act

The Alien Registration Act, popularly known as the Smith Act, 76th United States Congress, 3d session, ch. 439, , is a United States federal statute that was enacted on June 28, 1940. It set criminal penalties for advocating the overthrow of th ...

, a statute that prohibited advocating violent overthrow of the government. The defendants argued that they advocated a peaceful transition to socialism, and that the First Amendment

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and reco ...

's guarantee of freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recogni ...

and of association protected their membership in a political party. Appeals from these trials reached the US Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point of ...

, which ruled on issues in ''Dennis v. United States

''Dennis v. United States'', 341 U.S. 494 (1951), was a United States Supreme Court case relating to Eugene Dennis, General Secretary of the Communist Party USA. The Court ruled that Dennis did not have the right under the First Amendment to the U ...

'' (1951) and ''Yates v. United States

''Yates v. United States'', 354 U.S. 298 (1957), was a case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States that held that the First Amendment protected radical and reactionary speech, unless it posed a "clear and present danger."

Background

F ...

'' (1957).

The first trial of eleven communist leaders was held in New York in 1949; it was one of the lengthiest trials in United States history. Numerous supporters of the defendants protested outside the courthouse on a daily basis. The trial was featured twice on the cover of ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and event (philosophy), events that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various me ...

'' magazine. The defense frequently antagonized the judge and prosecution; five defendants were jailed for contempt of court

Contempt of court, often referred to simply as "contempt", is the crime of being disobedient to or disrespectful toward a court of law and its officers in the form of behavior that opposes or defies the authority, justice, and dignity of the cour ...

because they disrupted the proceedings. The prosecution's case relied on undercover informants, who described the goals of the CPUSA, interpreted communist texts, and testified of their own knowledge that the CPUSA advocated the violent overthrow of the US government.

While the first trial was under way, events outside the courtroom influenced public perception of communism: the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

tested its first nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

, and communists prevailed in the Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on main ...

. In this period, the House Un-American Activities Committee

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly dubbed the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative United States Congressional committee, committee of the United States House of Representatives, create ...

(HUAC) had also begun conducting investigations and hearings of writers and producers in Hollywood suspected of communist influence. Public opinion was overwhelmingly against the defendants in New York. After a 10-month trial, the jury found all 11 defendants guilty. The judge sentenced them to terms of up to five years in federal prison, and sentenced all five defense attorneys to imprisonment for contempt of court. Two of the attorneys were subsequently disbarred

Disbarment, also known as striking off, is the removal of a lawyer from a bar association or the practice of law, thus revoking their law license or admission to practice law. Disbarment is usually a punishment for unethical or criminal conduc ...

.

After the first trial, the prosecutorsencouraged by their success prosecuted more than 100 additional CPUSA officers for violating the Smith Act

The Alien Registration Act, popularly known as the Smith Act, 76th United States Congress, 3d session, ch. 439, , is a United States federal statute that was enacted on June 28, 1940. It set criminal penalties for advocating the overthrow of th ...

. Some were tried solely because they were members of the Party. Many of these defendants had difficulty finding attorneys to represent them. The trials decimated the leadership of the CPUSA. In 1957, eight years after the first trial, the US Supreme Court's ''Yates'' decision brought an end to similar prosecutions. It ruled that defendants could be prosecuted only for their actions, not for their beliefs.

Background

After the

After the revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

in Russia in 1917, the communist movement gradually gained footholds in many countries around the world. In Europe and the US, communist parties were formed, generally allied with trade union and labor causes. During the First Red Scare

The First Red Scare was a period during the early 20th-century history of the United States marked by a widespread fear of far-left movements, including Bolshevism and anarchism, due to real and imagined events; real events included the R ...

of 1919–1920, many U.S. capitalists were fearful that Bolshevism

Bolshevism (from Bolshevik) is a revolutionary socialist current of Soviet Marxist–Leninist political thought and political regime associated with the formation of a rigidly centralized, cohesive and disciplined party of social revolution, ...

and anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

would lead to disruption within the US. In the late 1930s, state and federal legislatures passed laws designed to expose communists, including laws requiring loyalty oaths, and laws requiring communists to register with the government. Even the American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1920 "to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States". T ...

(ACLU), a free-speech advocacy organization, passed a resolution in 1939 expelling communists from its leadership ranks.

Following Congressional investigation of left-wing and right-wing extremist political groups in the mid-1930s, support grew for a statutory prohibition of their activities. The alliance of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

in the August 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

, long_name = Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

, image = Bundesarchiv Bild 183-H27337, Moskau, Stalin und Ribbentrop im Kreml.jpg

, image_width = 200

, caption = Stalin and Ribbentrop shaking ...

and their invasion of Poland in September gave the movement added impetus. In 1940 the Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

passed the Alien Registration Act of 1940 (known as the Smith Act

The Alien Registration Act, popularly known as the Smith Act, 76th United States Congress, 3d session, ch. 439, , is a United States federal statute that was enacted on June 28, 1940. It set criminal penalties for advocating the overthrow of th ...

) which required all non-citizen adult residents to register with the government, and made it a crime "to knowingly or willfully advocate ... the duty, necessity, desirability, ... of overthrowing or destroying any government in the United States by force or violence ... with the intent to cause the overthrow or destruction of any government in the United States...."Levin, p 1488available online

accessed June 13, 2012The Smith Act was officially called the Alien Registration Act of 1940

The Act has been amended since then

Text of 2012 version

The portion of the 1940 Act that was relevant to the CPUSA trials was: "Sec. 2. (a) It shall be unlawful for any person— (1) to knowingly or willfully advocate, abet, advise, or teach the duty, necessity, desirability, or propriety of overthrowing or destroying any government in the United States by force or violence, or by the assassination of any officer of any such government; (2) with the intent to cause the overthrow or destruction of any government in the United States, to print, publish, edit, issue, circulate, sell, distribute, or publicly display any written or printed matter advocating, advising, or teaching the duty, necessity, desirability, or propriety of overthrowing or destroying any government in the United States by force or violence. (3) to organize or help to organize any society, group, or assembly of persons who teach, advocate, or encourage the overthrow or destruction of any government in the United States by force or violence; or to be or become a member of, or affiliate with, any such society, group, or assembly of persons, knowing the purposes thereof...." Five million non-citizens were fingerprinted and registered following passage of the Act. The first persons convicted under the Smith Act were members of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) in

Minneapolis

Minneapolis () is the largest city in Minnesota, United States, and the county seat of Hennepin County. The city is abundant in water, with thirteen lakes, wetlands, the Mississippi River, creeks and waterfalls. Minneapolis has its origin ...

in 1941. Leaders of the CPUSA, bitter rivals of the Trotskyist

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a ...

SWP, supported the Smith Act prosecution of the SWPa decision they would later regret. In 1943, the government used the Smith Act to prosecute American Nazis; that case ended in a mistrial

In law, a trial is a coming together of parties to a dispute, to present information (in the form of evidence) in a tribunal, a formal setting with the authority to adjudicate claims or disputes. One form of tribunal is a court. The tribunal, ...

when the judge died of a heart attack. Anxious to avoid alienating the Soviet Union, then an ally, the government did not prosecute any communists under the law during .

The CPUSA's membership peaked at around 80,000 members during World War II under the leadership of Earl Browder

Earl Russell Browder (May 20, 1891 – June 27, 1973) was an American politician, communist activist and leader of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). Browder was the General Secretary of the CPUSA during the 1930s and first half of the 1940s.

Durin ...

, who was not a strict Stalinist

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist-Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the theory ...

and cooperated with the US government during the war. In late 1945, hardliner William Z. Foster took over leadership of the CPUSA, and steered it on a course adhering to Stalin's policies. The CPUSA was not very influential in American politics, and by 1948 its membership had declined to 60,000 members. Truman did not feel that the CPUSA was a threat (he dismissed it as a "non problem") yet he made the specter of communism a campaign issue during the 1948 election.

The perception of communism in the US was shaped by the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

, which began after World War II when the Soviet Union failed to uphold the commitments it made at the Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (codenamed Argonaut), also known as the Crimea Conference, held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the post ...

. Instead of holding elections for new governments, as agreed at Yalta, the Soviet Union occupied several Eastern European countries

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

* Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

* Eastern Air ...

, leading to a strained relationship with the US. Subsequent international events served to increase the apparent danger that communism posed to Americans: the Stalinist threats in the Greek Civil War

The Greek Civil War ( el, ο Eμφύλιος �όλεμος}, ''o Emfýlios'' 'Pólemos'' "the Civil War") took place from 1946 to 1949. It was mainly fought against the established Kingdom of Greece, which was supported by the United Kingdom and ...

(1946–1949); the Czechoslovak coup d'état of 1948

Czechoslovak may refer to:

*A demonym or adjective pertaining to Czechoslovakia (1918–93)

**First Czechoslovak Republic (1918–38)

**Second Czechoslovak Republic (1938–39)

**Third Czechoslovak Republic (1948–60)

**Fourth Czechoslovak Repu ...

; and the 1948 blockade of Berlin.Belknap (1994), p 210.

The view of communism was also affected by evidence of espionage in the US conducted by agents of the USSR. In 1945, a Soviet spy, Elizabeth Bentley

Elizabeth Terrill Bentley (January 1, 1908 – December 3, 1963) was an American spy and member of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). She served the Soviet Union from 1938 to 1945 until she defected from the Communist Party and Soviet intellige ...

, repudiated the USSR and provided a list of Soviet spies in the US to the Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice ...

(FBI). The FBI also had access to secret Soviet communications, available from the Venona decryption effort, which revealed significant efforts by Soviet agents to conduct espionage within the US. The growing influence of communism around the world and the evidence of Soviet spies within the US motivated the Department of Justicespearheaded by the FBIto initiate an investigation of communists within the US.Belknap (1994), p 209.

1949 trial

In July 1945, FBI director

In July 1945, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American law enforcement administrator who served as the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He was appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation ...

instructed his agents to begin gathering information on CPUSA members to support an analysis of the Party's subversive goals, leading to a 1,850-page report published in 1946 which outlined a case for prosecution. As the Cold War continued to intensify in 1947, Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

held a hearing at which the Hollywood Ten

The Hollywood blacklist was an entertainment industry blacklist, broader than just Hollywood, put in effect in the mid-20th century in the United States during the early years of the Cold War. The blacklist involved the practice of denying empl ...

refused to testify about alleged involvement with the CPUSA, leading to their convictions for contempt of Congress

Contempt of Congress is the act of obstructing the work of the United States Congress or one of its committees. Historically, the bribery of a U.S. senator or U.S. representative was considered contempt of Congress. In modern times, contempt of C ...

in early 1948. The same year, Hoover instructed the Department of Justice

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

to bring charges against the CPUSA leaders with the intention of rendering the Party ineffective. John McGohey, a federal prosecutor from the Southern District of New York, was given the lead role in prosecuting the case and charged twelve leaders of the CPUSA with violations of the Smith Act. The specific charges against the defendants were first, that they conspired to overthrow the US government by violent means, and second, that they belonged to an organization that advocated the violent overthrow of the government. The indictment

An indictment ( ) is a formal accusation that a person has committed a crime. In jurisdictions that use the concept of felonies, the most serious criminal offence is a felony; jurisdictions that do not use the felonies concept often use that ...

, issued on June 29, 1948, asserted that the CPUSA had been in violation of the Smith Act since July 1945.Belknap (1994), p 211. The twelve defendants, arrested in late July 1948, were all members of the National Board of the CPUSA:

* Benjamin J. Davis, Jr. – Chairman of the CPUSA's Legislative Committee and Council-member of New York City

*Eugene Dennis

Francis Xavier Waldron (August 10, 1905 – January 31, 1961), best known by the pseudonym Eugene Dennis and Tim Ryan, was an American communist politician and union organizer, best remembered as the long-time leader of the Communist Party USA a ...

– CPUSA General Secretary

* William Z. Foster – CPUSA National Secretary (indicted; but not tried due to illness)

* John Gates – Leader of the Young Communist League

The Young Communist League (YCL) is the name used by the youth wing of various Communist parties around the world. The name YCL of XXX (name of country) originates from the precedent established by the Communist Youth International.

Examples of Y ...

* Gil Green – Member of the National Board (represented by A.J. Isserman)

*Gus Hall

Gus Hall (born Arvo Kustaa Halberg; October 8, 1910 – October 13, 2000) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) and a perennial candidate for president of the United States. He was the Communist Party nominee in the ...

– Member of the CPUSA National Board

* Irving Potash – Furriers Union official

*Jack Stachel

Jacob Abraham "Jack" Stachel (19001965) was an American Communist functionary who was a top official in the Communist Party from the middle 1920s until his death in the middle 1960s. Stachel is best remembered as one of 11 Communist leaders convic ...

– Editor of the ''Daily Worker

The ''Daily Worker'' was a newspaper published in New York City by the Communist Party USA, a formerly Comintern-affiliated organization. Publication began in 1924. While it generally reflected the prevailing views of the party, attempts were m ...

''

* Robert G. Thompson – Lead of the New York branch of CPUSA

* John Williamson – Member of the CPUSA Central Committee (represented by A.J. Isserman)

* Henry Winston – Member of the CPUSA National Board

*Carl Winter – Lead of the Michigan branch of CPUSA

Hoover hoped that all 55 members of the CPUSA's National Committee would be indicted and was disappointed that the prosecutors chose to pursue only twelve. A week before the arrests, Hoover complained to the Justice Departmentrecalling the arrests

An arrest is the act of apprehending and taking a person into custody (legal protection or control), usually because the person has been suspected of or observed committing a crime. After being taken into custody, the person can be quest ...

and convictions of over one hundred leaders of the Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines general ...

(IWW) in 1917"the IWW was crushed and never revived, similar action at this time would have been as effective against the Communist Party."

Start of the trial

The 1949 trial was held in New York City at the Foley Square federal courthouse of the

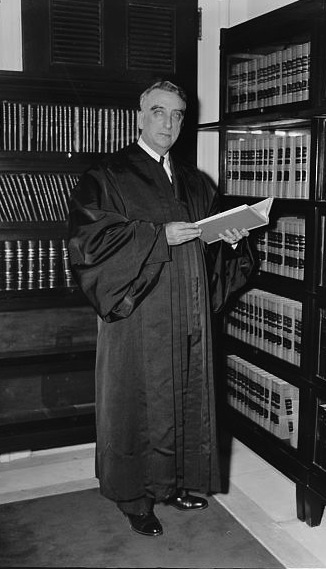

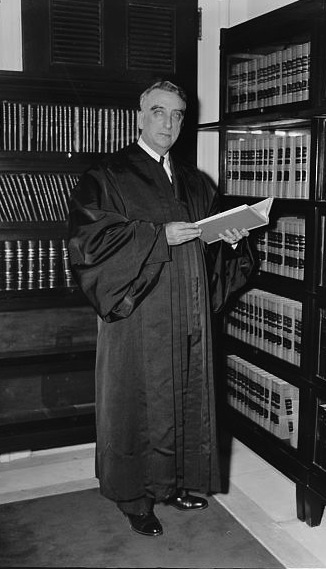

The 1949 trial was held in New York City at the Foley Square federal courthouse of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York

The United States District Court for the Southern District of New York (in case citations, S.D.N.Y.) is a federal trial court whose geographic jurisdiction encompasses eight counties of New York State. Two of these are in New York City: New ...

. Judge Harold Medina

Harold Raymond Medina (February 16, 1888 – March 14, 1990) was a United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit and previously was a United States district judge of the United States District Court fo ...

, a former Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

professor who had been on the bench for 18 months when the hearing began, presided.Morgan, p 314. Sabin, p 41. Before becoming a judge, Medina successfully argued the case of '' Cramer v. United States'' before the Supreme Court, defending a German-American charged with treason. The trial opened on November 1, 1948, and preliminary proceedings and jury selection lasted until January 17, 1949; the defendants first appeared in court on March 7, and the case concluded on October 14, 1949.Morgan, p 315. Although later trials surpassed it, in 1949 it was the longest federal trial in US history. The trial was one of the country's most contentious legal proceedings and sometimes had a "circus-like atmosphere".Walker, p 185.

Morgan, p 315.

Sabin, pp 44–45. "Circus-like" are Sabin's words. Four hundred police officers were assigned to the site on the opening day of the trial. Magazines, newspapers, and radio reported on the case heavily; ''Time'' magazine featured the trial on its cover twice with stories titled "Communists: The Presence of Evil" and "Communists: The Little Commissar" (referring to Eugene Dennis)."Communists: The Little Commissar"

''Time'', April 25, 1949 (Cover photo: Eugene Dennis).

''Time'': October 24, 1949. (Cover photo: Harold Medina).

''Time'', (article, not cover), August 22, 1949.

''Time'', April 4, 1949.

See also ''Life'' magazine articles "Communist trial ends with 11 guilty", ''Life'', October 24, 1949, p 31; and "Unrepentant reds emerge", ''Life'', March 14, 1955, p 30.

Public opinion

The opinion of the American public and the news media was overwhelming in favor of conviction. Magazines, newspapers, and radio reported on the case heavily; ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and event (philosophy), events that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various me ...

'' magazine featured the trial on its cover twice with stories titled "Communists: The Presence of Evil" and "Communists: The Little Commissar" (referring to Eugene Dennis).

Most American newspapers supported the prosecution, such as the ''New York World-Telegram

The ''New York World-Telegram'', later known as the ''New York World-Telegram and The Sun'', was a New York City newspaper from 1931 to 1966.

History

Founded by James Gordon Bennett Sr. as ''The Evening Telegram'' in 1867, the newspaper began ...

'' which reported that the Communist Party would soon be punished.Martelle, p 76. Martelle states that Shirer's statement was published in the ''New York Star''. ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', in an editorial, felt that the trial was warranted and denied assertions of the Party that the trial was a provocation comparable to the Reichstag fire

The Reichstag fire (german: Reichstagsbrand, ) was an arson attack on the Reichstag building, home of the German parliament in Berlin, on Monday 27 February 1933, precisely four weeks after Nazi leader Adolf Hitler was sworn in as Chancellor of ...

. ''The Christian Science Monitor

''The Christian Science Monitor'' (''CSM''), commonly known as ''The Monitor'', is a nonprofit news organization that publishes daily articles in electronic format as well as a weekly print edition. It was founded in 1908 as a daily newspaper ...

'' took a more detached view in an editorial: "The outcome of the case will be watched by government and political parties around the world as to how the United States, as an outstanding exponent of democratic government, intends to share the benefits of its civil liberties and yet protect them if and when they appear to be abused by enemies from within".

Support for the prosecutions was not universal, however.

During the proceedings, there were days when several thousand picketers protested in Foley Square

Foley Square, also called Federal Plaza, is a street intersection in the Civic Center neighborhood of Lower Manhattan, New York City, which contains a small triangular park named Thomas Paine Park. The space is bordered by Worth Street to t ...

outside the courthouse, chanting slogans like "Adolf Hitler never died / He's sitting at Medina's side". In response, the US House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

passed a bill in August to outlaw picketing near federal courthouses, but the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

did not vote on it before the end of the trial.Walker, p 186.

Journalist William L. Shirer

William Lawrence Shirer (; February 23, 1904 – December 28, 1993) was an American journalist and war correspondent. He wrote ''The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich'', a history of Nazi Germany that has been read by many and cited in scholarly w ...

was skeptical of the trial, writing "no overt act of trying to forcibly overthrow our government is charged ... The government's case is simply that by being members and leaders of the Communist Party, its doctrines and tactics being what they are, the accused are guilty of conspiracy". ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large n ...

'' wrote that the purpose of the government's legal attack on the CPUSA was "not so much the protection and security of the state as the exploitation of justice for the purpose of propaganda."

Third-party presidential candidate Henry A. Wallace

Henry Agard Wallace (October 7, 1888 – November 18, 1965) was an American politician, journalist, farmer, and businessman who served as the 33rd vice president of the United States, the 11th U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, and the 10th U.S. ...

claimed that the trial was an effort by the Truman administration to create an atmosphere of fear, writing "we Americans have far more to fear from those actions which are intended to suppress political freedom than from the teaching of ideas with which we are in disagreement." Farrell Dobbs

Farrell Dobbs (July 25, 1907 – October 31, 1983) was an American Trotskyist, trade unionist, politician, and historian.

Early years

Dobbs was born in Queen City, Missouri, where his father was a worker in a coal company garage. The family ...

of the SWP wrotedespite the fact that the CPUSA had supported Dobbs' prosecution under the Smith Act in 1941"I want to state in no uncertain terms that I as well as the Socialist Workers Party support their struggle against the obnoxious Smith Act, as well as against the indictments under that act".

Before the trial began, supporters of the defendants decided on a campaign of letter-writing and demonstrations: the CPUSA urged its members to bombard Truman with letters requesting that the charges be dropped.Belknap (1994), p 212. Later, supporters similarly flooded Judge Medina with telegrams and letters urging him to dismiss the charges.Redish, p 82.

The defense was not optimistic about the probability of success. After the trial was over, defendant Gates wrote: "The anti-communist hysteria was so intense, and most Americans were so frightened by the Communist issue, that we were convicted before our trial even started".Belknap (1994), p 208.

Prosecution

Prosecutor John McGohey did not assert that the defendants had a specific plan to violently overthrow the US government, but rather alleged that the CPUSA's philosophy generally advocated the violent overthrow of governments. The prosecution called witnesses who were either undercover informants, such as Angela Calomiris and Herbert Philbrick, or former communists who had become disenchanted with the CPUSA, such asLouis Budenz

Louis Francis Budenz (pronounced "byew-DENZ"; July 17, 1891 – April 27, 1972) was an American activist and writer, as well as a Soviet espionage agent and head of the ''Buben group'' of spies. He began as a labor activist and became a member ...

. The prosecution witnesses testified about the goals and policies of the CPUSA, and they interpreted the statements of pamphlets and books (including ''The Communist Manifesto

''The Communist Manifesto'', originally the ''Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (german: Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei), is a political pamphlet written by German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Commissioned by the Commu ...

'') and works by such authors as Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

and Joseph Stalin. The prosecution argued that the texts advocated violent revolution, and that by adopting the texts as their political foundation, the defendants were guilty of advocating violent overthrow of the government.

Calomiris was recruited by the FBI in 1942 and infiltrated the CPUSA, gaining access to a membership roster.Mahoney, M.H., ''Women in Espionage: A Biographical Dictionary'', Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 1993, pp 37–39. She received a salary from the FBI during her seven years as an informant. Calomiris identified four of the defendants as members of the CPUSA and provided information about its organization. She testified that the CPUSA espoused violent revolution against the government, and that the CPUSAacting on instructions from Moscowhad attempted to recruit members working in key war industries.

Budenz, a former communist, was another important witness for the prosecution who testified that the CPUSA subscribed to a philosophy of violent overthrow of the government. He also testified that the clauses of the constitution of the CPUSA that disavowed violence were decoys written in " Aesopian language" which were put in place specifically to protect the CPUSA from prosecution.

Defense

The five attorneys who volunteered to defend the communists were familiar with leftist causes and supported the defendants' rights to espouse socialist viewpoints. They were Abraham Isserman,George W. Crockett Jr.

George William Crockett Jr. (August 10, 1909 – September 7, 1997) was an African-American attorney, jurist, and congressman from the U.S. state of Michigan. He also served as a national vice-president of the National Lawyers Guild and c ...

, Richard Gladstein, Harry Sacher, and Louis F. McCabe.Communist Trial Ends with 11 Guilty, ''Life'', October 24, 1949, p 31. Defendant Eugene Dennis represented himself. The ACLU was dominated by anti-communist leaders during the 1940s, and did not enthusiastically support persons indicted under the Smith Act; but it did submit an ''amicus'' brief endorsing a motion for dismissal of the charges. The defense employed a three-pronged strategy: First, they sought to portray the CPUSA as a conventional political party, which promoted socialism by peaceful means; second, they attacked the trial as a capitalist venture which could never provide a fair outcome for proletarian defendants; and third, they used the trial as an opportunity to publicize CPUSA policies. The defense made pre-trial

motions

In physics, motion is the phenomenon in which an object changes its position with respect to time. Motion is mathematically described in terms of displacement, distance, velocity, acceleration, speed and frame of reference to an observer and me ...

arguing that the defendants' right to trial by a jury of their peers had been denied because, at that time, a potential grand juror had to meet a minimum property requirement, effectively eliminating the less affluent from service.Belknap (1994), p 213. Walker, p 185.

Starobin, p 206.

Medina's ruling on the jury selection issue i

83 F.Supp. 197 (1949)

The issue was addressed by the appeals court i

183 F.2d 201 (2d Cir. 1950)

The defense also argued that the jury selection process for the trial was similarly flawed.Belknap (1994), p 213. Their objections to the jury selection process were not successful and jurors included four African Americans and consisted primarily of working-class citizens.Belknap (1994), p 214. A primary theme of the defense was that the CPUSA sought to convert the US to socialism by education, not by force.Belknap (1994), p 219. The defense claimed that most of the prosecution's documentary evidence came from older texts that pre-dated the 1935 Seventh World Congress of the

Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

, after which the CPUSA rejected violence as a means of change. The defense attempted to introduce documents into evidence which represented the CPUSA's advocacy of peace, claiming that these policies superseded the older texts that the prosecution had introduced which emphasized violence. Medina excluded most of the material proposed by the defense because it did not directly pertain to the specific documents the prosecution had produced. As a result, the defense complained that they were unable to portray the totality of their belief system to the jury.Belknap (1994), p 220.

The defense attorneys developed a "labor defense" strategy, by which they attacked the entire trial process, including the prosecutor, the judge, and the jury selection process.Redish, pp 81–82. The strategy involved verbally disparaging the judge and the prosecutors, and may have been an attempt to provoke a mistrial.Sabin, p 46. "Mutual hostility" is Sabin's characterization. Another aspect of the labor defense was an effort to rally popular support to free the defendants, in the hope that public pressure would help achieve acquittals. Throughout the course of the trial, thousands of supporters of the defendants flooded the judge with protests, and marched outside the courthouse in Foley Square. The defense used the trial as an opportunity to educate the public about their beliefs, so they focused their defense around the political aspects of communism, rather than rebutting the legal aspects of the prosecution's evidence.Belknap (1994), p 218. Defendant Dennis chose to represent himself so he could, in his role as attorney, directly address the jury and explain communist principles.

Courtroom atmosphere

The trial was one of the country's most contentious legal proceedings and sometimes had a "circus-like atmosphere". Four hundred police officers were assigned to the site on the opening day of the trial. The defense deliberately antagonized the judge by making a large number of objections and motions, which led to numerous bitter engagements between the attorneys and Judge Medina. Despite the aggressive defense tactics and a voluminous letter-writing campaign directed at Medina, he stated "I will not be intimidated". Out of the chaos, an atmosphere of "mutual hostility" arose between the judge and attorneys. Judge Medina attempted to maintain order by removing disorderly defendants. In the course of the trial, Medina sent five of the defendants to jail for outbursts, including Hall because he shouted "I've heard more law in akangaroo court

A kangaroo court is a court that ignores recognized standards of law or justice, carries little or no official standing in the territory within which it resides, and is typically convened ad hoc. A kangaroo court may ignore due process and come ...

", and Winstonan African Americanfor shouting "more than five thousand Negroes have been lynched in this country". Several times in July and August, the judge held defense attorneys in contempt of court, and told them their punishment would be meted out upon conclusion of the trial.

Fellow judge James L. Oakes

James Lowell Oakes (February 21, 1924 – October 13, 2007) was a United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit and previously was a United States district judge of the United States District Court for ...

described Medina as a fair and reasonable judge, and wrote that "after the judge saw what the lawyers were doing, he gave them a little bit of their own medicine, too."Oakes, p 1460. Legal scholar and historian Michal Belknap writes that Medina was "unfriendly" to the defense, and that "there is reason to believe that Medina was biased against the defendants", citing a statement Medina made before the trial: "If we let them do that sort of thing ostpone the trial start they'll destroy the government". According to Belknap, Medina's behavior towards the defense may have been exacerbated by the fact that another federal judge had died of a heart attack during the 1943 trial involving the Smith Act.Belknap (2001), p 860. Some historians speculate that Medina came to believe that the defense was deliberately trying to provoke him into committing a legal error with the goal of achieving a mistrial.

Events outside the courtroom

During the ten-month trial, several events occurred in America that intensified the nation's

During the ten-month trial, several events occurred in America that intensified the nation's anti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and the ...

sentiment: The Judith Coplon

Judith Coplon Socolov (May 17, 1921 – February 26, 2011) was a spy for the Soviet Union whose trials, convictions, and successful constitutional appeals had a profound influence on espionage prosecutions during the Cold War.

In 1949, three majo ...

Soviet espionage case was in progress; former government employee Alger Hiss

Alger Hiss (November 11, 1904 – November 15, 1996) was an American government official accused in 1948 of having spied for the Soviet Union in the 1930s. Statutes of limitations had expired for espionage, but he was convicted of perjury in co ...

was tried for perjury

Perjury (also known as foreswearing) is the intentional act of swearing a false oath or falsifying an affirmation to tell the truth, whether spoken or in writing, concerning matters material to an official proceeding."Perjury The act or an inst ...

stemming from accusations that he was a communist (a trial also held at the Foley Square courthouse); labor leader Harry Bridges

Harry Bridges (28 July 1901 – 30 March 1990) was an Australian-born American union leader, first with the International Longshoremen's Association (ILA). In 1937, he led several chapters in forming a new union, the International Longshore an ...

was accused of perjury when he denied being a communist; and the ACLU passed an anti-communist resolution.Sabin, p 45. Two events during the final month of the trial may have been particularly influential: On September 23, 1949, Truman announced that the Soviet Union detonated its first nuclear bomb; and on October 1, 1949, the Communist Party of China

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Ci ...

prevailed in the Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on main ...

.

Defendants Irving Potash and Benjamin J. Davis were among the audience members attacked as they left a September 4 concert headlined by Paul Robeson

Paul Leroy Robeson ( ; April 9, 1898 – January 23, 1976) was an American bass-baritone concert artist, stage and film actor, professional American football, football player, and activist who became famous both for his cultural accomplish ...

in Peekskill, New York

Peekskill is a city in northwestern Westchester County, New York, United States, from New York City. Established as a village in 1816, it was incorporated as a city in 1940. It lies on a bay along the east side of the Hudson River, across from ...

. It was given to benefit the Civil Rights Congress

The Civil Rights Congress (CRC) was a United States civil rights organization, formed in 1946 at a national conference for radicals and disbanded in 1956. It succeeded the International Labor Defense, the National Federation for Constitutional ...

(CRC), which was funding the defendants' legal expenses. Hundreds lined the roads leaving the performance grounds and threw rocks and bottles at the departing vehicles without interference by the police. Over 140 people suffered injuries, including Potash, whose eyes were struck by glass from a broken windshield. The trial was suspended for two days while Potash recovered from his injuries.

Convictions and sentencing

On October 14, 1949, after the defense rested their case, the judge gave the jury instructions to guide them in reaching a verdict. He instructed the jury that the prosecution was not required to prove that the danger of violence was "clear and present"; instead, the jury should consider if the defendants had advocated communist policy as a "rule or principle of action" with the intention of inciting overthrow by violence "as speedily as circumstances would permit". This instruction was in response to the defendants, who endorsed the "clear and present danger

''Clear and Present Danger'' is a political thriller novel, written by Tom Clancy and published on August 17, 1989. A sequel to '' The Cardinal of the Kremlin'' (1988), main character Jack Ryan becomes acting Deputy Director of Intelligence in ...

" test, yet that test was not adopted as law by the Supreme Court. The judge's instructions included the phrase "I find as a matter of law that there is sufficient danger of a substantive evil ..." which would later be challenged by the defense during their appeals.Sabin, p 45. Belknap (1994), p 221.

Redish, p 87.

One instruction from Medina to the jury was "I find as a matter of law that there is sufficient danger of a substantive evil that the Congress had a right to prevent, to justify the application of the statute under the First Amendment of the Constitution." After deliberating for seven and one-half hours, the jury returned guilty verdicts against all eleven defendants.Belknap (1994), p 221. The judge sentenced ten defendants to five years and a $10,000 fine each ($ in dollars). The eleventh defendant, Robert G. Thompsona veteran of World War IIwas sentenced to three years in consideration of his wartime service. Thompson said that he took "no pleasure that this Wall Street judicial flunky has seen fit to equate my possession of the

Distinguished Service Cross The Distinguished Service Cross (D.S.C.) is a military decoration for courage. Different versions exist for different countries.

*Distinguished Service Cross (Australia)

*Distinguished Service Cross (United Kingdom)

*Distinguished Service Cross (U ...

to two years in prison."

Immediately after the jury rendered a verdict, Medina turned to the defense attorneys saying he had some "unfinished business" and he held them in contempt of court, and sentenced all of them to jail terms ranging from 30 days to six months; Dennis, acting as his own attorney, was also cited. Since the contempt sentences were based on behavior witnessed by the judge, no hearings were required for the contempt charges, and the attorneys were immediately handcuffed and led to jail.Sabin, p 47.

Public reaction

The vast majority of the public, and most news media, endorsed the verdict. Typical was a letter to the ''New York Times'': "The Communist Party may prove to be a hydra-headed monster unless we can discover how to kill the body as well as how to cut off its heads." The day of the convictions, New York Gov.Thomas E. Dewey

Thomas Edmund Dewey (March 24, 1902 – March 16, 1971) was an American lawyer, prosecutor, and politician who served as the 47th governor of New York from 1943 to 1954. He was the Republican candidate for president in 1944 and 1948: although ...

and Senator John Foster Dulles

John Foster Dulles (, ; February 25, 1888 – May 24, 1959) was an American diplomat, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. He served as United States Secretary of State under President Dwight D. Eisenhower from 1953 to 1959 and was briefly ...

praised the verdicts.

Some vocal supporters of the defendants spoke out in their defense. A New York resident wrote: "I am not afraid of communism ... I am only afraid of the trend in our country today away from the principles of democracy." Another wrote: "the trial was a political trial ... Does not the Soviet Union inspire fear in the world at large precisely because masses of human beings have no confidence in the justice of its criminal procedures against dissidents? ... I trust that the Supreme Court will be able to correct a grave error in the operation of our political machinery by finding the ... Smith bill unconstitutional." William Z. Foster wrote: "every democratic movement in the United States is menaced by this reactionary verdict ... The Communist Party will not be dismayed by this scandalous verdict, which belies our whole national democratic traditions. It will carry the fight to the higher courts, to the broad masses of the people." Vito Marcantonio

Vito is an Italian name that is derived from the Latin word "''vita''", meaning "life".

It is a modern form of the Latin name Vitus, meaning "life-giver," as in San Vito or Saint Vitus, the patron saint of dogs and a heroic figure in southern I ...

of the American Labor Party

The American Labor Party (ALP) was a political party in the United States established in 1936 that was active almost exclusively in the state of New York. The organization was founded by labor leaders and former members of the Socialist Party of A ...

wrote that the verdict was "a sharp and instant challenge to the freedom of every American." The ACLU

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1920 "to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States". ...

issued a statement reiterating its opposition to the Smith Act, because it felt the act criminalized political advocacy.

Abroad, the trial received little mention in mainstream press, but Communist newspapers were unanimous in their condemnation. The Moscow press wrote that Medina showed "extraordinary prejudice"; the London communist newspaper wrote that the defendants had been convicted only of "being communists"; and in France, a paper decried the convictions as "a step on the road that leads to war."

On October 21, President Truman appointed prosecutor John McGohey to serve as a US District Court judge. Judge Medina was hailed as a national hero and received 50,000 letters congratulating him on the trial outcome. On October 24, ''Time'' magazine featured Medina on its cover, and soon thereafter he was asked to consider running for governor of New York. On June 11, 1951, Truman nominated Medina to the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, where he served until 1980.

Bail and prison

After sentencing, the defendants postedbail

Bail is a set of pre-trial restrictions that are imposed on a suspect to ensure that they will not hamper the judicial process. Bail is the conditional release of a defendant with the promise to appear in court when required.

In some countrie ...

, enabling them to remain free during the appeal process. The $260,000 bail ($ in dollars) was provided by Civil Rights Congress

The Civil Rights Congress (CRC) was a United States civil rights organization, formed in 1946 at a national conference for radicals and disbanded in 1956. It succeeded the International Labor Defense, the National Federation for Constitutional ...

, a non-profit trust fund which was created to assist CPUSA members with legal expenses. While out on bail, Hall was appointed to a position in the secretariat within the CPUSA. Eugene Dennis wasin addition to his Smith Act chargesfighting contempt of Congress

Contempt of Congress is the act of obstructing the work of the United States Congress or one of its committees. Historically, the bribery of a U.S. senator or U.S. representative was considered contempt of Congress. In modern times, contempt of C ...

charges stemming from an incident in 1947 when he refused to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly dubbed the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative United States Congressional committee, committee of the United States House of Representatives, create ...

. He appealed the contempt charge, but the Supreme Court upheld his conviction for contempt in March 1950, and he began to serve a one-year term at that time.

While waiting for their legal appeals to be heard, the CPUSA leaders became convinced that the government would undertake the prosecution of many additional Party officers. To ensure continuity of their leadership, they decided that four of the defendants should go into hiding and lead the CPUSA from outside prison.Belknap (1994), pp 224–225. The defendants were ordered to report to prison on July 2, 1951, after the Supreme Court upheld their convictions and their legal appeals were exhausted. When July arrived, only seven defendants reported to prison, and four (Winston, Green, Thompson, and Hall) went into hiding, forfeiting $80,000 bail ($ in dollars). Hall was captured in Mexico in 1951, trying to flee to the Soviet Union. Thompson was captured in California in 1952. Both had three years added to their five-year sentences. Winston and Green surrendered voluntarily in 1956 after they felt that anti-communist hysteria had diminished. Some of the defendants did not fare well in prison: Thompson was attacked by an anti-communist inmate; Winston became blind because a brain tumor was not treated promptly; Gates was put into solitary confinement because he refused to lock the cells of fellow inmates; and Davis was ordered to mop floors because he protested against racial segregation in prison.Martelle, pp 256–257.

Perception of communism after the trial

After the convictions, the Cold War continued in the international arena. In December 1950, Truman declared a national emergency in response to the Korean War. The

After the convictions, the Cold War continued in the international arena. In December 1950, Truman declared a national emergency in response to the Korean War. The First Indochina War

The First Indochina War (generally known as the Indochina War in France, and as the Anti-French Resistance War in Vietnam) began in French Indochina from 19 December 1946 to 20 July 1954 between France and Việt Minh (Democratic Republic of Vi ...

continued in Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making ...

, in which communist forces in the north fought against French Union

The French Union () was a political entity created by the French Fourth Republic to replace the old French colonial empire system, colloquially known as the " French Empire" (). It was the formal end of the "indigenous" () status of French subj ...

forces in the south. The US expanded the Radio Free Europe

Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) is a United States government funded organization that broadcasts and reports news, information, and analysis to countries in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, Caucasus, and the Middle East where it says tha ...

broadcasting system in an effort to promote Western political ideals in Eastern Europe. In March 1951, American communists Julius and Ethel Rosenberg

Julius Rosenberg (May 12, 1918 – June 19, 1953) and Ethel Rosenberg (; September 28, 1915 – June 19, 1953) were American citizens who were convicted of spying on behalf of the Soviet Union. The couple were convicted of providing top-secret i ...

were convicted of spying for the Soviet Union. In 1952, the US exploded its first hydrogen bomb

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

, and the Soviet Union followed suit in 1953.Gregory, Ross, ''Cold War America, 1946 to 1990'', Infobase Publishing, 2003, pp 48–53, . Kort, Michael, ''The Columbia Guide to the Cold War'', Columbia University Press, 2001, .

Walker, Martin, ''The Cold War: a History'', Macmillan, 1995, . Domestically, the Cold War was in the forefront of national consciousness. In February 1950, Senator

Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican United States Senate, U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death in 1957. Beginning in 1950, McCarth ...

rose suddenly to national fame when he claimed "I have here in my hand a list" of over 200 communists who were employed in the State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other na ...

. In September 1950, the US Congress passed the McCarran Internal Security Act, which required communist organizations to register with the government, and formed the Subversive Activities Control Board to investigate persons suspected of engaging in subversive activities. High-profile hearings involving alleged communists included the 1950 conviction of Alger Hiss, the 1951 trial of the Rosenbergs, and the 1954 investigation of J. Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist. A professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley, Oppenheimer was the wartime head of the Los Alamos Laboratory and is oft ...

.

The convictions in the 1949 trial encouraged the Department of Justice to prepare for additional prosecutions of CPUSA leaders. Three months after the trial, in January 1950, a representative of the Justice Department testified before Congress during appropriation hearings to justify an increase in funding to support Smith Act prosecutions.Sabin, p 56. See also Fast, Howard, "The Big Finger", ''Masses & Mainstream'', March, 1950, pp 62–68. He testified that there were 21,105 potential persons that could be indicted under the Smith Act, and that 12,000 of those would be indicted if the Smith Act was upheld as constitutional. The FBI had compiled a list of 200,000 persons in its Communist Index; since the CPUSA had only around 32,000 members in 1950, the FBI explained the disparity by asserting that for every official Party member, there were ten persons who were loyal to the CPUSA and ready to carry out its orders. Seven months after the convictions, in May 1950, Hoover gave a radio address in which he declared "communists have been and are today at work within the very gates of America.... Wherever they may be, they have in common one diabolic ambition: to weaken and to eventually destroy American democracy by stealth and cunning." Other federal government agencies also worked to undermine organizations, such as the CPUSA, they considered subversive: The

Internal Revenue Service

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is the revenue service for the United States federal government, which is responsible for collecting U.S. federal taxes and administering the Internal Revenue Code, the main body of the federal statutory t ...

investigated 81 organizations that were deemed to be subversive, threatening to revoke their tax exempt status; Congress passed a law prohibiting members of subversive organizations from obtaining federal housing benefits; and attempts were made to deny Social Security benefits, veterans benefits, and unemployment benefits to communist sympathizers.

Legal appeals of 1949 trial

The 1949 trial defendants appealed to theSecond Circuit Court of Appeals

The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit (in case citations, 2d Cir.) is one of the thirteen United States Courts of Appeals. Its territory comprises the states of Connecticut, New York and Vermont. The court has appellate juri ...

in 1950. In the appeal they raised issues about the use of informant witnesses, the impartiality of the jury and judge, the judge's conduct, and free speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recog ...

.Belknap (2005), pp 258–259. Their free speech arguments raised important constitutional issues: they asserted that their political advocacy was protected by the First Amendment

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and reco ...

, because the CPUSA did not advocate imminent violence, but instead merely promoted revolution as an abstract concept.

Free speech law

One of the major issues raised on appeal was that the defendants' political advocacy was protected by theFirst Amendment