Floyd Collins on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

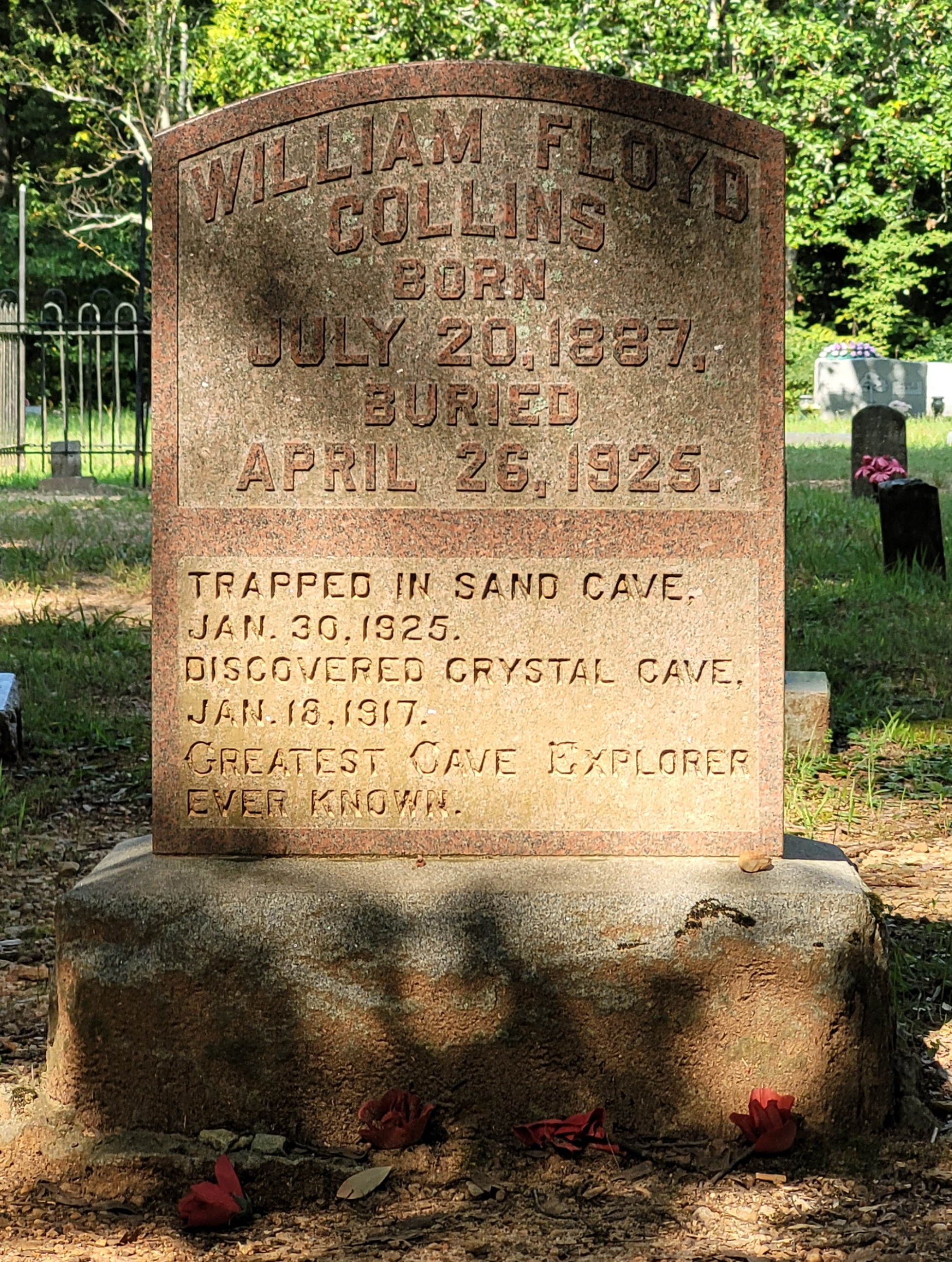

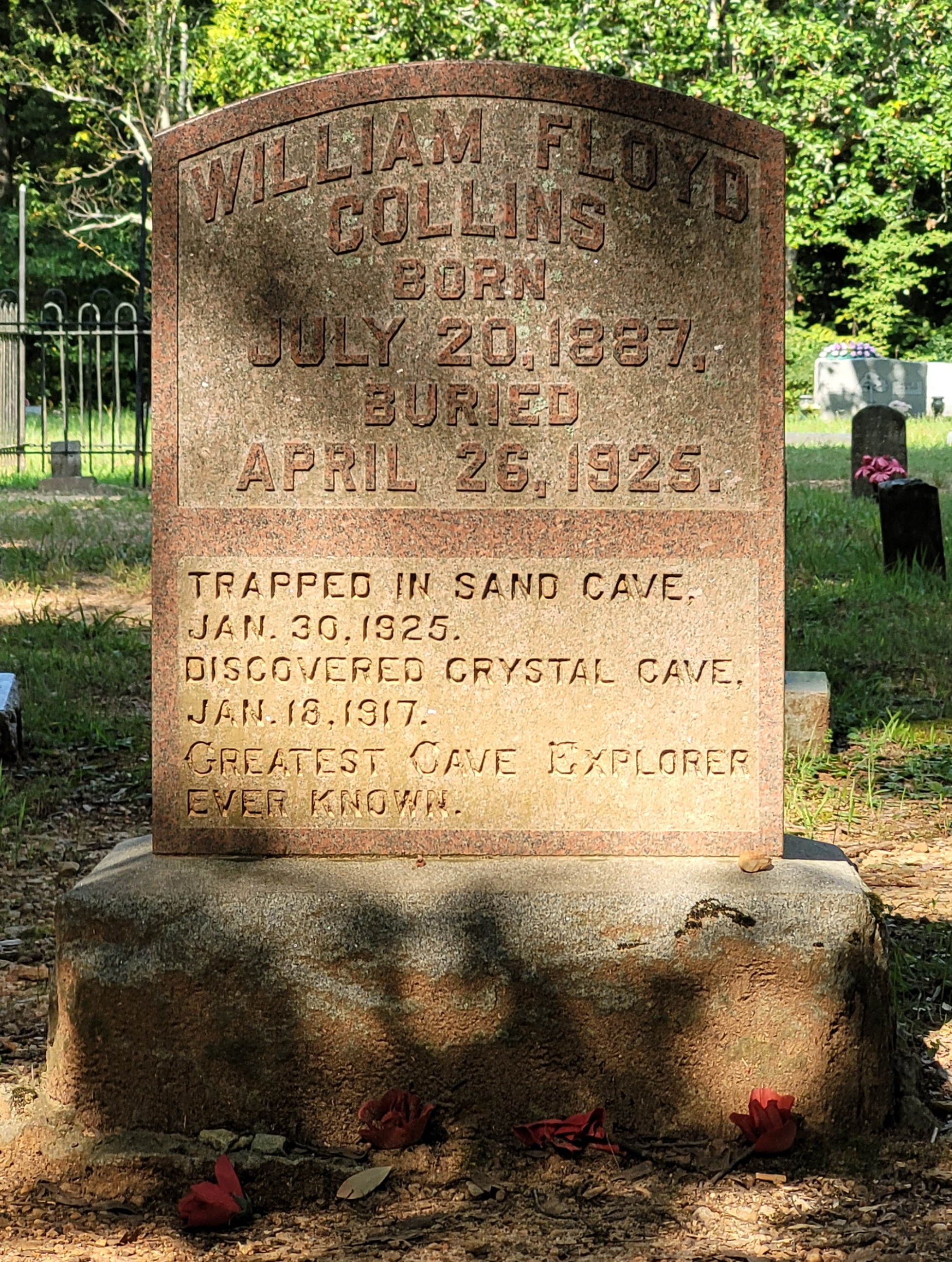

William Floyd Collins (July 20, 1887 – February 13, 1925) was an American cave explorer, principally in a region of

William Floyd Collins was born on July 20, 1887

, on the Collins family farm, located approximately east of

William Floyd Collins was born on July 20, 1887

, on the Collins family farm, located approximately east of

In September 1917, while climbing up a

In September 1917, while climbing up a

Collins hoped to find another entrance to the Mammoth Cave or possibly an unknown cave along the road to Mammoth Cave and draw more visitors and greater profits. He made an agreement with three farmers, who owned land closer to the main highway. If he found a cave, they would form a business partnership and share in the responsibilities of operating this tourist attraction. Working alone, within three weeks, he had explored and expanded a hole that would later be called "Sand Cave" by the news media. On January 30, 1925, after several hours of work, Collins managed to squeeze through several narrow passageways; he claimed he had discovered a large grotto chamber, though this was never verified. Because his lamp was dying, he had to leave quickly before losing all light to the chamber, but became trapped in a small passage on his way out. Collins accidentally knocked over his lamp, putting out the light, and was caught by a rock that fell from the cave ceiling, pinning his left leg. He was trapped from the entrance.

After he was found the next day by his younger brother, crackers were sent to him and an electric light was run down the passage to provide him lighting and some warmth. Collins survived for more than a week while rescue efforts were organized. On February 4, the cave passage collapsed in two places. Rescue leaders, led by Henry St. George Tucker Carmichael, determined the cave impassable and too dangerous and began to dig a shaft to reach the chamber behind Collins. The shaft and subsequent lateral tunnel intersected the cave just above Collins, but when he was finally reached on Monday, February 16, by miner Ed Brenner, he was "cold and apparently dead." Having been appointed as the members of a coroner's jury, Floyd's friend, Johnnie Gerald, a few other acquaintances of Floyd, were allowed to go into the lateral tunnel and positively identify the body. Dr. William Hazlett and Captain C.E. Francis, National Guard medical officer, were then unsuccessful in an attempt to reach the body but Brenner went in front of them to the body and was able to follow their examination instructions for the official death declaration to be made. It was estimated Floyd had been dead for three to five days, with February 13 the most likely date. Because he could not be reached from behind, the rescuers could not free his leg. Carmichael decided that Floyd's body would be left in place and the shaft would be filled with debris. After being allowed to enter the shaft, Skeets Miller and another reporter corroborated Carmichael's claim that it would be too dangerous to retrieve the body.

Collins hoped to find another entrance to the Mammoth Cave or possibly an unknown cave along the road to Mammoth Cave and draw more visitors and greater profits. He made an agreement with three farmers, who owned land closer to the main highway. If he found a cave, they would form a business partnership and share in the responsibilities of operating this tourist attraction. Working alone, within three weeks, he had explored and expanded a hole that would later be called "Sand Cave" by the news media. On January 30, 1925, after several hours of work, Collins managed to squeeze through several narrow passageways; he claimed he had discovered a large grotto chamber, though this was never verified. Because his lamp was dying, he had to leave quickly before losing all light to the chamber, but became trapped in a small passage on his way out. Collins accidentally knocked over his lamp, putting out the light, and was caught by a rock that fell from the cave ceiling, pinning his left leg. He was trapped from the entrance.

After he was found the next day by his younger brother, crackers were sent to him and an electric light was run down the passage to provide him lighting and some warmth. Collins survived for more than a week while rescue efforts were organized. On February 4, the cave passage collapsed in two places. Rescue leaders, led by Henry St. George Tucker Carmichael, determined the cave impassable and too dangerous and began to dig a shaft to reach the chamber behind Collins. The shaft and subsequent lateral tunnel intersected the cave just above Collins, but when he was finally reached on Monday, February 16, by miner Ed Brenner, he was "cold and apparently dead." Having been appointed as the members of a coroner's jury, Floyd's friend, Johnnie Gerald, a few other acquaintances of Floyd, were allowed to go into the lateral tunnel and positively identify the body. Dr. William Hazlett and Captain C.E. Francis, National Guard medical officer, were then unsuccessful in an attempt to reach the body but Brenner went in front of them to the body and was able to follow their examination instructions for the official death declaration to be made. It was estimated Floyd had been dead for three to five days, with February 13 the most likely date. Because he could not be reached from behind, the rescuers could not free his leg. Carmichael decided that Floyd's body would be left in place and the shaft would be filled with debris. After being allowed to enter the shaft, Skeets Miller and another reporter corroborated Carmichael's claim that it would be too dangerous to retrieve the body.

Newspaper reporter William Burke "Skeets" Miller from ''

Newspaper reporter William Burke "Skeets" Miller from ''

With Collins's body remaining in the cave, funeral services were held on the surface. Homer Collins was not pleased with Sand Cave as his brother's grave, and two months later, he and some friends reopened the shaft. They dug a new tunnel to the opposite side of the cave passage and recovered Floyd Collins' remains on April 23, 1925. The body was taken that day to Cave City for embalming at J.T. Geralds and Brothers funeral home. Following a 2-day visitation at the funeral home, on April 26, 1925, his body was transported to the Collins family farm and buried on the hillside over Great Crystal Cave, which Lee Collins renamed "Floyd Collins' Crystal Cave." In 1927, Lee Collins sold the homestead and cave to Dr. Harry Thomas, dentist and owner of Mammoth Onyx Cave and Hidden River Cave. The new owner placed Collins' body in a glass-topped coffin and exhibited it in Crystal Cave for many years. On the night of March 18–19, 1929, the body was stolen. The body was later recovered, having been found in a nearby field, but the injured left leg was missing. After this desecration, the remains were kept in a secluded portion of Crystal Cave in a chained casket. In 1961, Crystal Cave was purchased by Mammoth Cave National Park and closed to the public. The Collins family had objected to Collins' body being displayed in the cave and, at their request, the National Park Service re-interred him at Mammoth Cave Baptist Church Cemetery, Mammoth Cave, Kentucky in 1989. It took a team of 15 men three days to remove the

With Collins's body remaining in the cave, funeral services were held on the surface. Homer Collins was not pleased with Sand Cave as his brother's grave, and two months later, he and some friends reopened the shaft. They dug a new tunnel to the opposite side of the cave passage and recovered Floyd Collins' remains on April 23, 1925. The body was taken that day to Cave City for embalming at J.T. Geralds and Brothers funeral home. Following a 2-day visitation at the funeral home, on April 26, 1925, his body was transported to the Collins family farm and buried on the hillside over Great Crystal Cave, which Lee Collins renamed "Floyd Collins' Crystal Cave." In 1927, Lee Collins sold the homestead and cave to Dr. Harry Thomas, dentist and owner of Mammoth Onyx Cave and Hidden River Cave. The new owner placed Collins' body in a glass-topped coffin and exhibited it in Crystal Cave for many years. On the night of March 18–19, 1929, the body was stolen. The body was later recovered, having been found in a nearby field, but the injured left leg was missing. After this desecration, the remains were kept in a secluded portion of Crystal Cave in a chained casket. In 1961, Crystal Cave was purchased by Mammoth Cave National Park and closed to the public. The Collins family had objected to Collins' body being displayed in the cave and, at their request, the National Park Service re-interred him at Mammoth Cave Baptist Church Cemetery, Mammoth Cave, Kentucky in 1989. It took a team of 15 men three days to remove the

Tragedy at Sand Cave (U.S. National Park Service)

* ttps://skeptoid.com/blog/2014/09/26/undergound-war/ The Tragedy of History's Smallest Underground War {{DEFAULTSORT:Collins, William Floyd 1887 births 1925 deaths Accidental deaths in Kentucky American cavers American explorers Burials in Kentucky Caving incidents and rescues People from Logan County, Kentucky

Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

that houses hundreds of miles of interconnected cave

A cave or cavern is a natural void in the ground, specifically a space large enough for a human to enter. Caves often form by the weathering of rock and often extend deep underground. The word ''cave'' can refer to smaller openings such as sea ...

s, today a part of Mammoth Cave National Park, the longest known cave system in the world.

In the early 20th century, in an era known as the Kentucky Cave Wars, spelunkers and property owners entered into bitter competition to exploit the bounty of caves for commercial profit from tourists, who paid to see the caves. In 1917 and 1918, Collins discovered and commercialized Great Crystal Cave in the Flint Ridge Cave System, but the cave was remote and visitors were few. Collins had an ambition to find another cave he could open to the public closer to the main roads, and entered into an agreement with a neighbor to open up Sand Cave, a small cave on the neighbor's property.

On January 30, 1925, while working to enlarge the small passage in Sand Cave, Collins became trapped in a narrow crawlway below ground. The rescue operation to save him became a national media sensation and one of the first major news stories to be reported using the new technology of broadcast radio

Radio broadcasting is transmission of audio (sound), sometimes with related metadata, by radio waves to radio receivers belonging to a public audience. In terrestrial radio broadcasting the radio waves are broadcast by a land-based radio ...

. After four days, during which rescuers were able to bring water and food to Collins, a rock collapse in the cave closed the entrance passageway, stranding him inside, except for voice contact, for more than two weeks. Collins died of thirst

Thirst is the craving for potable fluids, resulting in the basic instinct of animals to drink. It is an essential mechanism involved in fluid balance. It arises from a lack of fluids or an increase in the concentration of certain osmolites, suc ...

and hunger

In politics, humanitarian aid, and the social sciences, hunger is defined as a condition in which a person does not have the physical or financial capability to eat sufficient food to meet basic Human nutrition, nutritional needs for a sustaine ...

compounded by exposure through hypothermia

Hypothermia is defined as a body core temperature below in humans. Symptoms depend on the temperature. In mild hypothermia, there is shivering and mental confusion. In moderate hypothermia, shivering stops and confusion increases. In severe ...

after being isolated for fourteen days, and three days before a rescue shaft reached his position. Collins' body was recovered two months later.

Although Collins was an unknown figure for most of his lifetime, the fame he gained from the rescue efforts and his death led to him being memorialized on his tombstone as the "Greatest Cave Explorer Ever Known".

Early life

William Floyd Collins was born on July 20, 1887

, on the Collins family farm, located approximately east of

William Floyd Collins was born on July 20, 1887

, on the Collins family farm, located approximately east of Mammoth Cave

Mammoth Cave National Park is an American national park in west-central Kentucky, encompassing portions of Mammoth Cave, the longest cave system known in the world.

Since the 1972 unification of Mammoth Cave with the even-longer system under F ...

near the Green River in Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

. He was the third child of Leonidas "Lee" Collins and Martha Jane Burnett, who gave birth to eight children: Elizabeth (died at three months of age), James "Jim", Floyd, Annie, Andy Lee, Marshall, Nellie, and Homer. Floyd began entering cave

A cave or cavern is a natural void in the ground, specifically a space large enough for a human to enter. Caves often form by the weathering of rock and often extend deep underground. The word ''cave'' can refer to smaller openings such as sea ...

s by himself at the age of six in search of Native American artifacts to sell to tourists at the Mammoth Cave Hotel. In 1910 Floyd discovered his first cave, Donkey's Cave, on the Collins farm. In 1912, Edmund Turner, a geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid, liquid, and gaseous matter that constitutes Earth and other terrestrial planets, as well as the processes that shape them. Geologists usually study geology, earth science, or geophysics, althoug ...

, hired Floyd to show him caves of the region. Consequently, Turner and Floyd assisted with the discovery of Dossey's Dome Cave in 1912 and Great Onyx Cave in 1915. Later in 1915, Floyd's mother died due to tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, i ...

and Lee Collins married a Mammoth Cave guide's widow, Serilda Jane "Miss Jane" Buckingham.

Great Crystal Cave

In September 1917, while climbing up a

In September 1917, while climbing up a bluff

Bluff or The Bluff may refer to:

Places Australia

* Bluff, Queensland, Australia, a town

* The Bluff, Queensland (Ipswich), a rural locality in the city of Ipswich

* The Bluff, Queensland (Toowoomba Region), a rural locality

* Bluff River (New ...

on the Collins farm, Floyd noticed cool air coming from a hole in the ground. Upon widening the hole, he was able to drop down into a cavity that was part of a passage blocked by breakdown. In December 1917, after further excavation of the breakdown, Floyd discovered the sinkhole

A sinkhole is a depression or hole in the ground caused by some form of collapse of the surface layer. The term is sometimes used to refer to doline, enclosed depressions that are locally also known as ''vrtače'' and shakeholes, and to openi ...

entrance to what he would later name "Great Crystal Cave." Lee Collins deeded Floyd a half interest in the cave and they immediately decided to commercialize it. After tremendous preparation by the entire family, the transformed show cave was opened to tourists in April 1918. However, the cave attracted a low number of tourists due to its remote location.

Sand Cave – 1925 incident

Collins hoped to find another entrance to the Mammoth Cave or possibly an unknown cave along the road to Mammoth Cave and draw more visitors and greater profits. He made an agreement with three farmers, who owned land closer to the main highway. If he found a cave, they would form a business partnership and share in the responsibilities of operating this tourist attraction. Working alone, within three weeks, he had explored and expanded a hole that would later be called "Sand Cave" by the news media. On January 30, 1925, after several hours of work, Collins managed to squeeze through several narrow passageways; he claimed he had discovered a large grotto chamber, though this was never verified. Because his lamp was dying, he had to leave quickly before losing all light to the chamber, but became trapped in a small passage on his way out. Collins accidentally knocked over his lamp, putting out the light, and was caught by a rock that fell from the cave ceiling, pinning his left leg. He was trapped from the entrance.

After he was found the next day by his younger brother, crackers were sent to him and an electric light was run down the passage to provide him lighting and some warmth. Collins survived for more than a week while rescue efforts were organized. On February 4, the cave passage collapsed in two places. Rescue leaders, led by Henry St. George Tucker Carmichael, determined the cave impassable and too dangerous and began to dig a shaft to reach the chamber behind Collins. The shaft and subsequent lateral tunnel intersected the cave just above Collins, but when he was finally reached on Monday, February 16, by miner Ed Brenner, he was "cold and apparently dead." Having been appointed as the members of a coroner's jury, Floyd's friend, Johnnie Gerald, a few other acquaintances of Floyd, were allowed to go into the lateral tunnel and positively identify the body. Dr. William Hazlett and Captain C.E. Francis, National Guard medical officer, were then unsuccessful in an attempt to reach the body but Brenner went in front of them to the body and was able to follow their examination instructions for the official death declaration to be made. It was estimated Floyd had been dead for three to five days, with February 13 the most likely date. Because he could not be reached from behind, the rescuers could not free his leg. Carmichael decided that Floyd's body would be left in place and the shaft would be filled with debris. After being allowed to enter the shaft, Skeets Miller and another reporter corroborated Carmichael's claim that it would be too dangerous to retrieve the body.

Collins hoped to find another entrance to the Mammoth Cave or possibly an unknown cave along the road to Mammoth Cave and draw more visitors and greater profits. He made an agreement with three farmers, who owned land closer to the main highway. If he found a cave, they would form a business partnership and share in the responsibilities of operating this tourist attraction. Working alone, within three weeks, he had explored and expanded a hole that would later be called "Sand Cave" by the news media. On January 30, 1925, after several hours of work, Collins managed to squeeze through several narrow passageways; he claimed he had discovered a large grotto chamber, though this was never verified. Because his lamp was dying, he had to leave quickly before losing all light to the chamber, but became trapped in a small passage on his way out. Collins accidentally knocked over his lamp, putting out the light, and was caught by a rock that fell from the cave ceiling, pinning his left leg. He was trapped from the entrance.

After he was found the next day by his younger brother, crackers were sent to him and an electric light was run down the passage to provide him lighting and some warmth. Collins survived for more than a week while rescue efforts were organized. On February 4, the cave passage collapsed in two places. Rescue leaders, led by Henry St. George Tucker Carmichael, determined the cave impassable and too dangerous and began to dig a shaft to reach the chamber behind Collins. The shaft and subsequent lateral tunnel intersected the cave just above Collins, but when he was finally reached on Monday, February 16, by miner Ed Brenner, he was "cold and apparently dead." Having been appointed as the members of a coroner's jury, Floyd's friend, Johnnie Gerald, a few other acquaintances of Floyd, were allowed to go into the lateral tunnel and positively identify the body. Dr. William Hazlett and Captain C.E. Francis, National Guard medical officer, were then unsuccessful in an attempt to reach the body but Brenner went in front of them to the body and was able to follow their examination instructions for the official death declaration to be made. It was estimated Floyd had been dead for three to five days, with February 13 the most likely date. Because he could not be reached from behind, the rescuers could not free his leg. Carmichael decided that Floyd's body would be left in place and the shaft would be filled with debris. After being allowed to enter the shaft, Skeets Miller and another reporter corroborated Carmichael's claim that it would be too dangerous to retrieve the body.

Media attention

Newspaper reporter William Burke "Skeets" Miller from ''

Newspaper reporter William Burke "Skeets" Miller from ''The Courier-Journal

''The Courier-Journal'',

also known as the

''Louisville Courier Journal''

(and informally ''The C-J'' or ''The Courier''),

is the highest circulation newspaper in Kentucky. It is owned by Gannett and billed as "Part of the ''USA Today'' Net ...

'' in Louisville

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border.

...

reported on the rescue efforts from the scene. Miller, of small stature, was able to remove a lot of earth from around Collins. He also interviewed Collins in the cave, receiving a Pulitzer Prize for his coverage and playing a part in Collins' attempted rescue. Miller's reports were distributed by telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

and were printed by newspapers across the country and abroad, and the rescue attempts were followed by regular news bulletins on the new medium of broadcast radio

Radio is the technology of signaling and communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 30 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmi ...

(the first broadcast radio station KDKA having been established in 1920). Shortly after the media arrived, the publicity drew crowds of tourists to the site, at one point numbering in the tens of thousands. Collins' neighbors sold hamburgers for 25 cents. Other vendors set up stands to sell food and souvenirs, creating a circus-like atmosphere. The Sand Cave rescue attempt grew to become the third-biggest media event

A media event, also known as a pseudo-event, is an event, activity, or experience conducted for the purpose of media publicity. It may also include any event that is covered in the mass media or was hosted largely with the media in mind.

In media ...

between the world wars. (The biggest media events of that time both involved Charles Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. On May 20–21, 1927, Lindbergh made the first nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, a distance o ...

—the trans-Atlantic flight and his son's kidnapping—and Lindbergh actually had a minor role in the Sand Cave rescue, too, having been hired to fly photographic negatives from the scene for a newspaper.) Since the nearest telegraph station was in Cave City, some miles from the cave, two amateur radio operators with the callsigns 9BRK and 9CHG provided the link to pass messages to the authorities and the press.

Burials and exhibition of body

With Collins's body remaining in the cave, funeral services were held on the surface. Homer Collins was not pleased with Sand Cave as his brother's grave, and two months later, he and some friends reopened the shaft. They dug a new tunnel to the opposite side of the cave passage and recovered Floyd Collins' remains on April 23, 1925. The body was taken that day to Cave City for embalming at J.T. Geralds and Brothers funeral home. Following a 2-day visitation at the funeral home, on April 26, 1925, his body was transported to the Collins family farm and buried on the hillside over Great Crystal Cave, which Lee Collins renamed "Floyd Collins' Crystal Cave." In 1927, Lee Collins sold the homestead and cave to Dr. Harry Thomas, dentist and owner of Mammoth Onyx Cave and Hidden River Cave. The new owner placed Collins' body in a glass-topped coffin and exhibited it in Crystal Cave for many years. On the night of March 18–19, 1929, the body was stolen. The body was later recovered, having been found in a nearby field, but the injured left leg was missing. After this desecration, the remains were kept in a secluded portion of Crystal Cave in a chained casket. In 1961, Crystal Cave was purchased by Mammoth Cave National Park and closed to the public. The Collins family had objected to Collins' body being displayed in the cave and, at their request, the National Park Service re-interred him at Mammoth Cave Baptist Church Cemetery, Mammoth Cave, Kentucky in 1989. It took a team of 15 men three days to remove the

With Collins's body remaining in the cave, funeral services were held on the surface. Homer Collins was not pleased with Sand Cave as his brother's grave, and two months later, he and some friends reopened the shaft. They dug a new tunnel to the opposite side of the cave passage and recovered Floyd Collins' remains on April 23, 1925. The body was taken that day to Cave City for embalming at J.T. Geralds and Brothers funeral home. Following a 2-day visitation at the funeral home, on April 26, 1925, his body was transported to the Collins family farm and buried on the hillside over Great Crystal Cave, which Lee Collins renamed "Floyd Collins' Crystal Cave." In 1927, Lee Collins sold the homestead and cave to Dr. Harry Thomas, dentist and owner of Mammoth Onyx Cave and Hidden River Cave. The new owner placed Collins' body in a glass-topped coffin and exhibited it in Crystal Cave for many years. On the night of March 18–19, 1929, the body was stolen. The body was later recovered, having been found in a nearby field, but the injured left leg was missing. After this desecration, the remains were kept in a secluded portion of Crystal Cave in a chained casket. In 1961, Crystal Cave was purchased by Mammoth Cave National Park and closed to the public. The Collins family had objected to Collins' body being displayed in the cave and, at their request, the National Park Service re-interred him at Mammoth Cave Baptist Church Cemetery, Mammoth Cave, Kentucky in 1989. It took a team of 15 men three days to remove the casket

A casket jewelry box is a container that is usually smaller than a chest, and in the past were typically decorated. Whereas cremation jewelry is a small container, usually in the shape of a pendant or bracelet, to hold a small amount of ashes.

...

and tombstone from the cave.

Legacy

Collins' life and death inspired the musical ''Floyd Collins'' byAdam Guettel

Adam Guettel (; born December 16, 1964) is an American composer- lyricist of musical theater and opera. The grandson of musical theatre composer Richard Rodgers, he is best known for his musical '' The Light in the Piazza'', for which he won the ...

and Tina Landau

Tina Landau (born May 21, 1962) is an American playwright and theatre director. Known for her large-scale, musical, and ensemble-driven work, Landau's productions have appeared on Broadway, Off-Broadway, and regionally, most extensively at the ...

, as well as one film documentary, several books, a museum and many short songs.

In 2006, actor Billy Bob Thornton

Billy Bob Thornton (born August 4, 1955) is an American actor, filmmaker and musician. He had his first break when he co-wrote and starred in the 1992 thriller ''One False Move'', and received international attention after writing, directing, a ...

optioned the film rights to ''Trapped! The Story of Floyd Collins'' and a screenplay was adapted by Thornton's writing partner, Tom Epperson. However, Thornton's option expired and the film rights were acquired by producer Peter R. J. Deyell in 2011.

Fiddlin' John Carson

"Fiddlin'" John Carson (March 23, 1868 – December 11, 1949) was an American old-time fiddler and singer who recorded what is widely considered to be the first country music song featuring vocals and lyrics.

Early life

Carson was born near M ...

and Vernon Dalhart

Marion Try Slaughter (April 6, 1883 – September 14, 1948), better known by his stage name Vernon Dalhart, was an American country music singer and songwriter. His recording of the classic ballad "Wreck of the Old 97" was the first country song ...

recorded "The Death of Floyd Collins" in 1925.

John Prine

John Edward Prine (; October 10, 1946 – April 7, 2020) was an American singer-songwriter of country-folk music. He was active as a composer, recording artist, live performer, and occasional actor from the early 1970s until his death. He ...

and Mac Wiseman recorded "Death of Floyd Collins" on their 2007 album '' Standard Songs for Average People''.

See also

* Moose River Disaster, mine cave-in covered extensively on radio in 1936References

Further reading

*External links

Tragedy at Sand Cave (U.S. National Park Service)

* ttps://skeptoid.com/blog/2014/09/26/undergound-war/ The Tragedy of History's Smallest Underground War {{DEFAULTSORT:Collins, William Floyd 1887 births 1925 deaths Accidental deaths in Kentucky American cavers American explorers Burials in Kentucky Caving incidents and rescues People from Logan County, Kentucky