Fitz John Porter on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

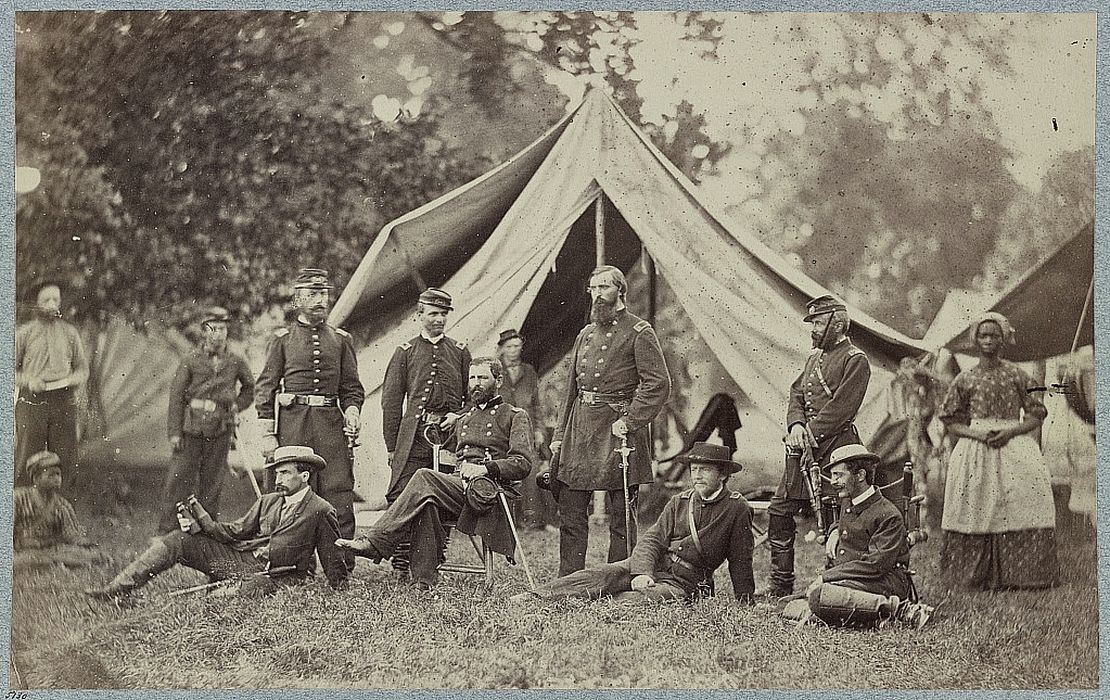

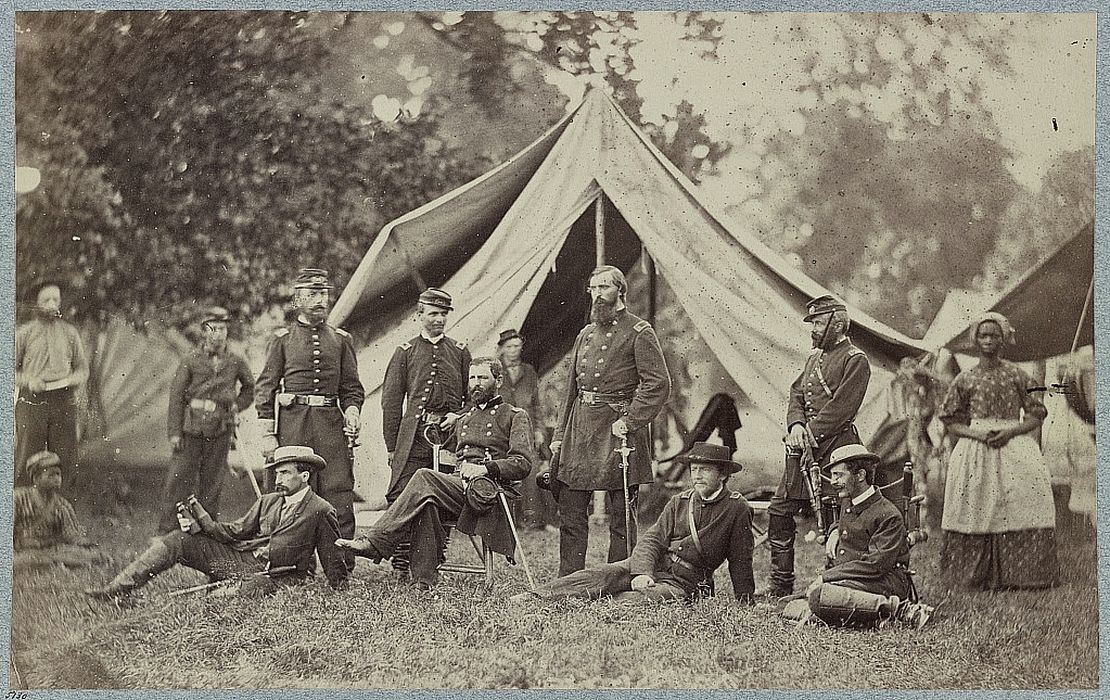

Fitz John Porter (August 31, 1822 – May 21, 1901) (sometimes written FitzJohn Porter or Fitz-John Porter) was a career

After the start of the Civil War, Porter became chief of staff and assistant adjutant general for the Department of

After the start of the Civil War, Porter became chief of staff and assistant adjutant general for the Department of

Porter's corps was sent to reinforce Maj. Gen. John Pope in the Northern Virginia Campaign, a reassignment that he openly challenged and complained about, criticizing Pope personally. During the

Porter's corps was sent to reinforce Maj. Gen. John Pope in the Northern Virginia Campaign, a reassignment that he openly challenged and complained about, criticizing Pope personally. During the  On August 30 Pope again ordered the flank attack, and Porter reluctantly complied. As the V Corps turned to head towards Jackson's right and attacked, it presented its own (and consequently the entire army's) flank to Longstreet's waiting men. About 30,000 Confederates assailed Porter's 5,000 or so men, driving through them and into the rest of Pope's forces, doing exactly what Porter most feared would come of these orders. Pope was infuriated by the defeat, accused Porter of insubordination, and relieved him of his command on September 5.Dupuy, p. 608.

Porter was soon restored to command of the corps by McClellan and led it through the Maryland Campaign, where the corps served in a reserve position during the

On August 30 Pope again ordered the flank attack, and Porter reluctantly complied. As the V Corps turned to head towards Jackson's right and attacked, it presented its own (and consequently the entire army's) flank to Longstreet's waiting men. About 30,000 Confederates assailed Porter's 5,000 or so men, driving through them and into the rest of Pope's forces, doing exactly what Porter most feared would come of these orders. Pope was infuriated by the defeat, accused Porter of insubordination, and relieved him of his command on September 5.Dupuy, p. 608.

Porter was soon restored to command of the corps by McClellan and led it through the Maryland Campaign, where the corps served in a reserve position during the

* In 1862, Camp Fitz-John Porter is established in Monroe County, NY one mile south of

* In 1862, Camp Fitz-John Porter is established in Monroe County, NY one mile south of

Porter biography

Civil War Home

Civil War Home

Harriet Porter

Wife Of Union General Fitz John Porter * {{DEFAULTSORT:Porter, Fitz John 1822 births 1901 deaths People from Portsmouth, New Hampshire People of New Hampshire in the American Civil War People from Morristown, New Jersey United States Army personnel who were court-martialed American military personnel of the Mexican–American War Members of the Aztec Club of 1847 Burials at Green-Wood Cemetery Union Army generals United States Military Academy alumni Recipients of American presidential pardons Phillips Exeter Academy alumni Military personnel from New Jersey

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

officer and a Union general

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. He is most known for his performance at the Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confedera ...

and his subsequent court martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

.

Although Porter served well in the early battles of the Civil War, his military career was ruined by the controversial trial, which was called by his political rivals. After the war, he worked for almost 25 years to restore his tarnished reputation and was finally restored to the army's roll.

Early life and education

Porter was born on August 31, 1822 inPortsmouth, New Hampshire

Portsmouth is a city in Rockingham County, New Hampshire, United States. At the 2020 census it had a population of 21,956. A historic seaport and popular summer tourist destination on the Piscataqua River bordering the state of Maine, Portsm ...

, the son of Captain John Porter and Eliza Chauncy Clark. He came from a family prominent in American naval service; his cousins were William D. Porter, David Dixon Porter

David Dixon Porter (June 8, 1813 – February 13, 1891) was a United States Navy admiral and a member of one of the most distinguished families in the history of the U.S. Navy. Promoted as the second U.S. Navy officer ever to attain the rank of ...

, and David G. Farragut. Porter's father was an alcoholic who had been reassigned to land duty. Porter's childhood was chaotic because of his father's illness. The younger Porter pursued an army career. He graduated from Phillips Exeter Academy

(not for oneself) la, Finis Origine Pendet (The End Depends Upon the Beginning) gr, Χάριτι Θεοῦ (By the Grace of God)

, location = 20 Main Street

, city = Exeter, New Hampshire

, zipcode ...

, then from the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

(West Point) in 1845, standing eighth out of 41 cadets, and was brevetted

In many of the world's military establishments, a brevet ( or ) was a warrant giving a commissioned officer a higher rank title as a reward for gallantry or meritorious conduct but may not confer the authority, precedence, or pay of real rank. ...

a second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army unt ...

in the 4th U.S. Artillery.Eicher & Eicher, p. 435.

Career

Porter was promoted to second lieutenant on June 18, 1846 andFirst Lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a ...

on May 29, 1847. He served in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

and was appointed a brevet captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

on September 8, 1847, for bravery at the Battle of Molino del Rey

The Battle of Molino del Rey (8 September 1847) was one of the bloodiest engagements of the Mexican–American War as part of the Battle for Mexico City. It was fought in September 1847 between Mexican forces under General Antonio León again ...

. He was wounded at Chapultepec

Chapultepec, more commonly called the "Bosque de Chapultepec" (Chapultepec Forest) in Mexico City, is one of the largest city parks in Mexico, measuring in total just over 686 hectares (1,695 acres). Centered on a rock formation called Chapultep ...

on September 13, for which he also received a brevet promotion to major

Major ( commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicato ...

. He was an original member of the Aztec Club of 1847

The Aztec Club of 1847 is a military society founded in 1847 by United States Army officers of the Mexican–American War. It exists as a hereditary organization including members who can trace a direct lineal connection to those originally eligib ...

, a military society composed of officers who served during the Mexican War.

After the war with Mexico ended, Porter returned to West Point and became a cavalry and artillery instructor from 1849 to 1853. He served as adjutant to the academy's superintendent until 1855. He next was posted to Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., and the oldest perma ...

, Kansas

Kansas () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its Capital city, capital is Topeka, Kansas, Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita, Kansas, Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebras ...

, as assistant adjutant general

An adjutant general is a military chief administrative officer.

France

In Revolutionary France, the was a senior staff officer, effectively an assistant to a general officer. It was a special position for lieutenant-colonels and colonels in staf ...

in the Department of the West in 1856; he was brevetted to captain at Fort Leavenworth that June. Porter served under future Confederate Albert Sidney Johnston

Albert Sidney Johnston (February 2, 1803 – April 6, 1862) served as a general in three different armies: the Texian Army, the United States Army, and the Confederate States Army. He saw extensive combat during his 34-year military career, figh ...

in the expedition against the Mormons in 1857 and 1858. Afterward, Porter inspected and reorganized the defenses of Charleston Harbor

The Charleston Harbor is an inlet (8 sq mi/20.7 km²) of the Atlantic Ocean at Charleston, South Carolina. The inlet is formed by the junction of Ashley and Cooper rivers at . Morris and Sullivan's Islands shelter the entrance. Charleston ...

, South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, until late 1860, when he aided the evacuation of military personnel from Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

after that state seceded from the Union.Dupuy, p. 607.

American Civil War

After the start of the Civil War, Porter became chief of staff and assistant adjutant general for the Department of

After the start of the Civil War, Porter became chief of staff and assistant adjutant general for the Department of Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, but he was soon promoted to colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

of the 15th Infantry on May 14, 1861. General John A. Logan, Porter's later political nemesis, would accuse Porter of helping persuade his commander Robert Patterson

Robert Patterson (January 12, 1792 – August 7, 1881) was an Irish-born United States major general during the American Civil War, chiefly remembered for inflicting an early defeat on Stonewall Jackson, but crucially failing to stop Confed ...

to let Joseph E. Johnston

Joseph Eggleston Johnston (February 3, 1807 – March 21, 1891) was an American career army officer, serving with distinction in the United States Army during the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) and the Seminole Wars. After Virginia secede ...

's force escape out of the Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridg ...

and reinforce P. G. T. Beauregard, thus turning the tide at the First Battle of Bull Run

The First Battle of Bull Run (the name used by Union forces), also known as the Battle of First Manassas

. In August, Porter was promoted to brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

of volunteers

Volunteering is a voluntary act of an individual or group freely giving time and labor for community service. Many volunteers are specifically trained in the areas they work, such as medicine, education, or emergency rescue. Others serve ...

, backdated to May 17 so he would be senior enough to receive divisional command in the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confede ...

, newly formed under Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

. Soon Porter became a trusted adviser and loyal friend to McClellan, but his association with the soon-to-be-controversial commanding general would prove to be disastrous for Porter's military career.

Porter led his division at the beginning of the Peninsula Campaign, seeing action at the Siege of Yorktown

The Siege of Yorktown, also known as the Battle of Yorktown, the surrender at Yorktown, or the German battle (from the presence of Germans in all three armies), beginning on September 28, 1781, and ending on October 19, 1781, at Yorktown, Virg ...

. McClellan created two provisional corps and Porter was assigned to command the V Corps 5th Corps, Fifth Corps, or V Corps may refer to:

France

* 5th Army Corps (France)

* V Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* V Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army ...

. During the Seven Days Battles

The Seven Days Battles were a series of seven battles over seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army of the Potomac, comman ...

, and particularly at the Battle of Gaines' Mill

The Battle of Gaines' Mill, sometimes known as the Battle of Chickahominy River, took place on June 27, 1862, in Hanover County, Virginia, as the third of the Seven Days Battles (Peninsula Campaign) of the American Civil War. Following the inconc ...

, he displayed a talent for defensive fighting. At the Battle of Malvern Hill

The Battle of Malvern Hill, also known as the Battle of Poindexter's Farm, was fought on July 1, 1862, between the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, led by Gen. Robert E. Lee, and the Union Army of the Potomac under Maj. Gen. George B. M ...

, Porter also played a leading role.

Inadvertent balloon ride

In addition, Porter had a memorable experience when he decided to make aerial observations in ahot air balloon

A hot air balloon is a lighter-than-air aircraft consisting of a bag, called an envelope, which contains heated air. Suspended beneath is a gondola or wicker basket (in some long-distance or high-altitude balloons, a capsule), which carries ...

without the assigned expert to handle the craft, Professor Thaddeus Lowe

Thaddeus Sobieski Constantine Lowe (August 20, 1832 – January 16, 1913), also known as Professor T. S. C. Lowe, was an American Civil War aeronaut, scientist and inventor, mostly self-educated in the fields of chemistry, meteorology, and a ...

. When he ascended with only one securing line, the balloon subsequently broke loose and General Porter found himself drifting west over enemy lines in danger of being captured or killed. Fortunately, the combination of a favorable wind change and himself adjusting the gas values allowed Porter to return to the Union lines and land safely. Although it was an embarrassing accident, General Porter was able to perform his observations of enemy defences as intended and recorded his findings, although the balloon program was disbanded a year later.

For his successful performance on the peninsula, he was promoted to major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

of volunteers on July 4, 1862.

Second Bull Run

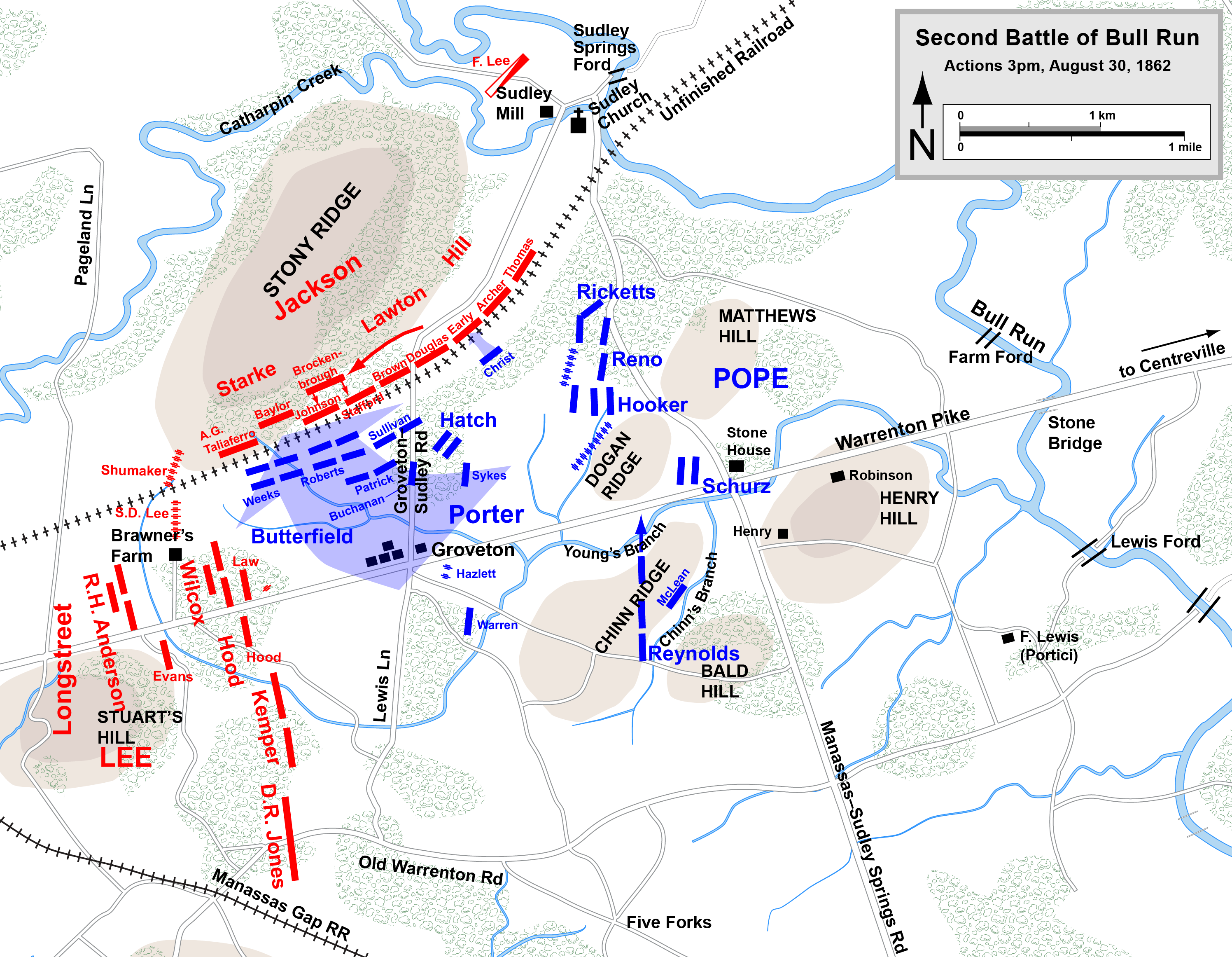

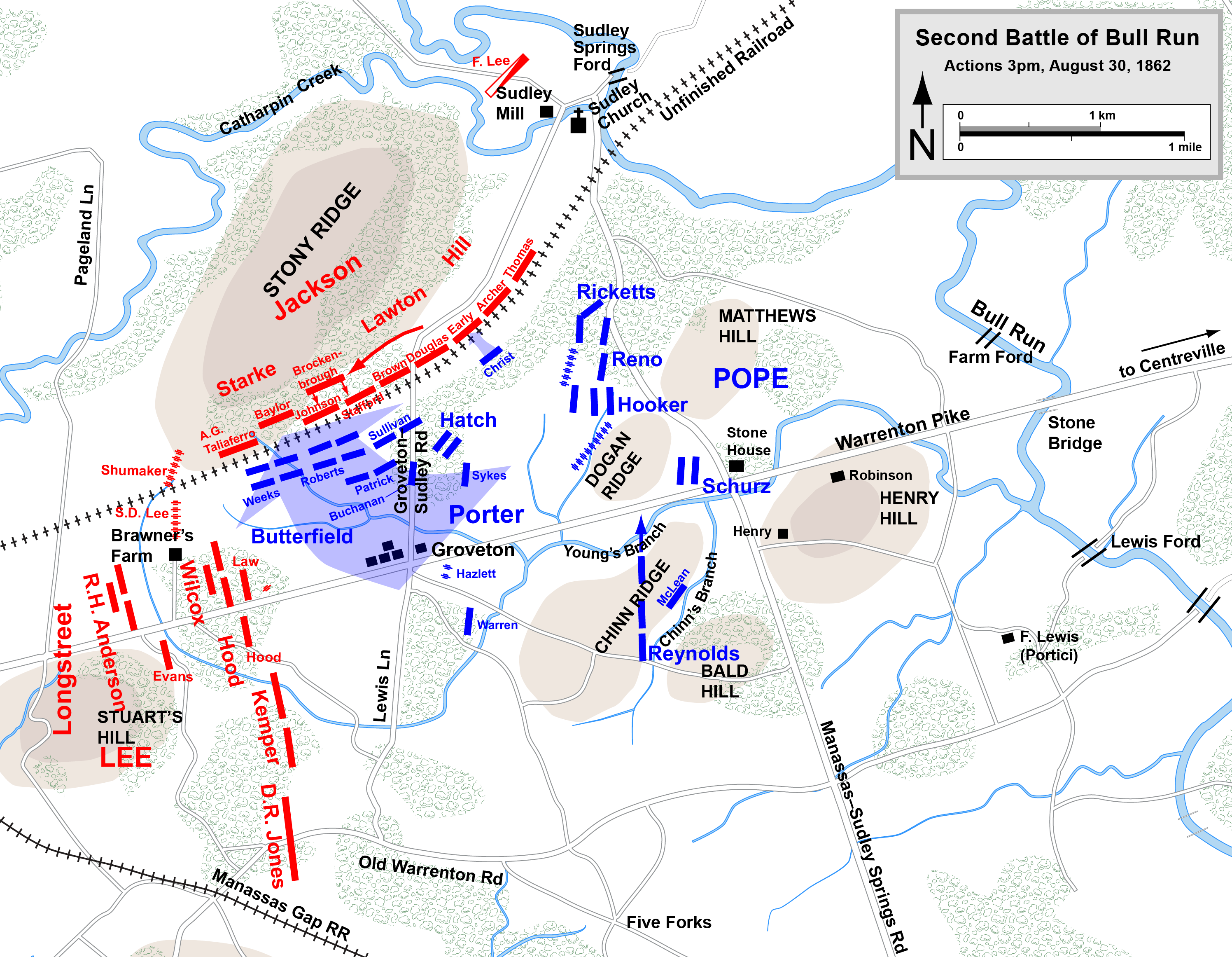

Porter's corps was sent to reinforce Maj. Gen. John Pope in the Northern Virginia Campaign, a reassignment that he openly challenged and complained about, criticizing Pope personally. During the

Porter's corps was sent to reinforce Maj. Gen. John Pope in the Northern Virginia Campaign, a reassignment that he openly challenged and complained about, criticizing Pope personally. During the Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confedera ...

, on August 29, 1862, he was ordered to attack the flank and rear of Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's wing of the Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most oft ...

. Porter had stopped at Dawkin's Branch, where he had encountered Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart's cavalry screen. On August 29 he received a message from Pope directing him to attack the Confederate right (which Pope assumed to be Jackson on Stony Ridge), but at the same time to maintain contact with the neighboring division under Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds, a conflict in orders that could not be resolved. Pope was apparently unaware that Confederate Maj. Gen. James Longstreet

James Longstreet (January 8, 1821January 2, 1904) was one of the foremost General officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate generals of the American Civil War and the principal subordinate to General Robert E. Lee, who called him his ...

's wing of the opposing army had arrived on the battlefield; the proposed envelopment of Jackson's position would have collided suicidally with Longstreet's large force. Porter chose not to make the attack because of the intelligence he had received that Longstreet was to his immediate front.

On August 30 Pope again ordered the flank attack, and Porter reluctantly complied. As the V Corps turned to head towards Jackson's right and attacked, it presented its own (and consequently the entire army's) flank to Longstreet's waiting men. About 30,000 Confederates assailed Porter's 5,000 or so men, driving through them and into the rest of Pope's forces, doing exactly what Porter most feared would come of these orders. Pope was infuriated by the defeat, accused Porter of insubordination, and relieved him of his command on September 5.Dupuy, p. 608.

Porter was soon restored to command of the corps by McClellan and led it through the Maryland Campaign, where the corps served in a reserve position during the

On August 30 Pope again ordered the flank attack, and Porter reluctantly complied. As the V Corps turned to head towards Jackson's right and attacked, it presented its own (and consequently the entire army's) flank to Longstreet's waiting men. About 30,000 Confederates assailed Porter's 5,000 or so men, driving through them and into the rest of Pope's forces, doing exactly what Porter most feared would come of these orders. Pope was infuriated by the defeat, accused Porter of insubordination, and relieved him of his command on September 5.Dupuy, p. 608.

Porter was soon restored to command of the corps by McClellan and led it through the Maryland Campaign, where the corps served in a reserve position during the Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union ...

. He is said to have told McClellan, "Remember, General, I command the last reserve of the last Army of the Republic." McClellan took his implied advice and failed to commit his reserves into a battle that might have been won if he had used his forces aggressively.

Court martial

On November 25, 1862, Porter was arrested andcourt-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

ed for his actions at Second Bull Run. By this time, McClellan had been relieved by President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

and could not provide political cover for his protégé. Porter's association with the disgraced McClellan and his open criticism of Pope were significant reasons for his conviction at court-martial. Porter was found guilty on January 10, 1863, of disobedience and misconduct, and he was dismissed from the Army on January 21, 1863.

In describing the Battle of Second Manassas, Edward Porter Alexander wrote that Confederates who knew Porter respected him greatly and considered his dismissal "one of the best fruits of their victory".

Later life and death

After the war ended, Porter was offered a command in the Egyptian Army but declined it. He spent most of the remainder of his public life fighting against the perceived injustice of his court-martial. In 1878, a special commission under GeneralJohn Schofield

John McAllister Schofield (September 29, 1831 – March 4, 1906) was an American soldier who held major commands during the American Civil War. He was appointed U.S. Secretary of War (1868–1869) under President Andrew Johnson and later served ...

exonerated Porter by finding that his reluctance to attack Longstreet probably saved Pope's Army of Virginia

The Army of Virginia was organized as a major unit of the Union Army and operated briefly and unsuccessfully in 1862 in the American Civil War. It should not be confused with its principal opponent, the Confederate Army of ''Northern'' Virginia ...

from an even greater defeat. Eight years later, President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

commuted Porter's sentence and a special act of the U.S. Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washin ...

restored Porter's commission as an infantry colonel in the U.S. Army, backdated to May 14, 1861, but without any back pay due. Two days later, August 7, 1886, Porter, seeing vindication, voluntarily retired from the Army.

Porter was involved in mining, construction, and commerce. He was appointed as the New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

Commissioner of Public Works, the New York City Police Commissioner, and the New York City Fire Commissioner.

On December 27, 1894, Porter, along with 18 others, founded the Military and Naval Order of the United States, which was soon renamed the Military Order of Foreign Wars

The Military Order of Foreign Wars of the United States (MOFW) is one of the oldest veterans' and hereditary associations in the nation with a membership that includes officers and their hereditary descendants from all of the Armed Services. Memb ...

. Porter's name was at the top of the list of signers of the original institution and received the first insignia issued by the Order.

Porter died in Morristown, New Jersey

Morristown () is a town and the county seat of Morris County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.Green-Wood Cemetery

Green-Wood Cemetery is a cemetery in the western portion of Brooklyn, New York City. The cemetery is located between South Slope/ Greenwood Heights, Park Slope, Windsor Terrace, Borough Park, Kensington, and Sunset Park, and lies several blo ...

, Brooklyn, New York

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

. His grave can be found in Section 54, Lot 5685/89.

Legacy

* In 1862, Camp Fitz-John Porter is established in Monroe County, NY one mile south of

* In 1862, Camp Fitz-John Porter is established in Monroe County, NY one mile south of Rochester, NY

Rochester () is a city in the U.S. state of New York, the seat of Monroe County, and the fourth-most populous in the state after New York City, Buffalo, and Yonkers, with a population of 211,328 at the 2020 United States census. Located in Wes ...

on the western bank of the Genesee River. The camp was the mustering location for the 108th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment the 140th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment

The 140th New York Infantry Regiment was a volunteer infantry regiment that was created on September 13, 1862, for the Union Army during the American Civil War. From January 1864 they wore a Zouave uniform.

Formation

On August 8, 1862, Captai ...

and Mack's 18th Independent "Black Horse" artillery battery. In 2008 a historical marker is erected to mark the location.

* In 1904, a statue of Porter designed by artist James E. Kelly was dedicated in Haven Park in Portsmouth, New Hampshire

Portsmouth is a city in Rockingham County, New Hampshire, United States. At the 2020 census it had a population of 21,956. A historic seaport and popular summer tourist destination on the Piscataqua River bordering the state of Maine, Portsm ...

.

*

* Porterstown Road in the town by the same name runs directly through the area where his forces were placed for the Battle of Sharpsburg.

* His Portsmouth home is listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic ...

See also

*List of American Civil War generals (Union)

Union generals

__NOTOC__

The following lists show the names, substantive ranks, and brevet ranks (if applicable) of all general officers who served in the United States Army during the Civil War, in addition to a small selection of lower-rank ...

* List of people pardoned or granted clemency by the president of the United States

Notes

Bibliography

* Dupuy, Trevor N., Curt Johnson, and David L. Bongard. ''Harper Encyclopedia of Military Biography

''The Harper Encyclopedia of Military Biography'' () was written by Trevor N. Dupuy, Curt Johnson and David Bongard, and was issued in 1992 by HarperCollins Publishers. It contains more than three thousand short biographies of military figures f ...

''. New York: HarperCollins, 1992. .

* Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. ''Civil War High Commands''. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. .

* Grant, U. S. "An Undeserved Stigma" in ''North American Review'', Vol. 135, No. 313, December 1882, pp. 536–46.

* McPherson, James M. '' Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era''. Oxford History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. .

* Sears, Stephen W. ''Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam''. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1983. .

Porter biography

Civil War Home

Civil War Home

Further reading

* Eisenschiml, Otto, ''The Celebrated Case of Fitz John Porter: An AmericanDreyfus Affair

The Dreyfus affair (french: affaire Dreyfus, ) was a political scandal that divided the French Third Republic from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. "L'Affaire", as it is known in French, has come to symbolise modern injustice in the Francop ...

'', Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill, 1950.

* Hennessy, John J. ''Return to Bull Run: The Campaign and Battle of Second Manassas.'' Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1993. .

* Soini, Wayne. ''Porter's Secret: Fitz John Porter's Monument Decoded.'' Portsmouth, New Hampshire: Jetty House an imprint of Peter E. Randall Publisher, 2011. .

* Paleno, Gene. "The Porter Conspiracy, A story of the Civil War", PAL Publishing, Upper Lake CA ()

*

External links

Harriet Porter

Wife Of Union General Fitz John Porter * {{DEFAULTSORT:Porter, Fitz John 1822 births 1901 deaths People from Portsmouth, New Hampshire People of New Hampshire in the American Civil War People from Morristown, New Jersey United States Army personnel who were court-martialed American military personnel of the Mexican–American War Members of the Aztec Club of 1847 Burials at Green-Wood Cemetery Union Army generals United States Military Academy alumni Recipients of American presidential pardons Phillips Exeter Academy alumni Military personnel from New Jersey