Fish respiration on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Fish physiology is the scientific study of how the component parts of

Fish physiology is the scientific study of how the component parts of

Most fish exchange gases using

Most fish exchange gases using  All basal vertebrates breathe with

All basal vertebrates breathe with

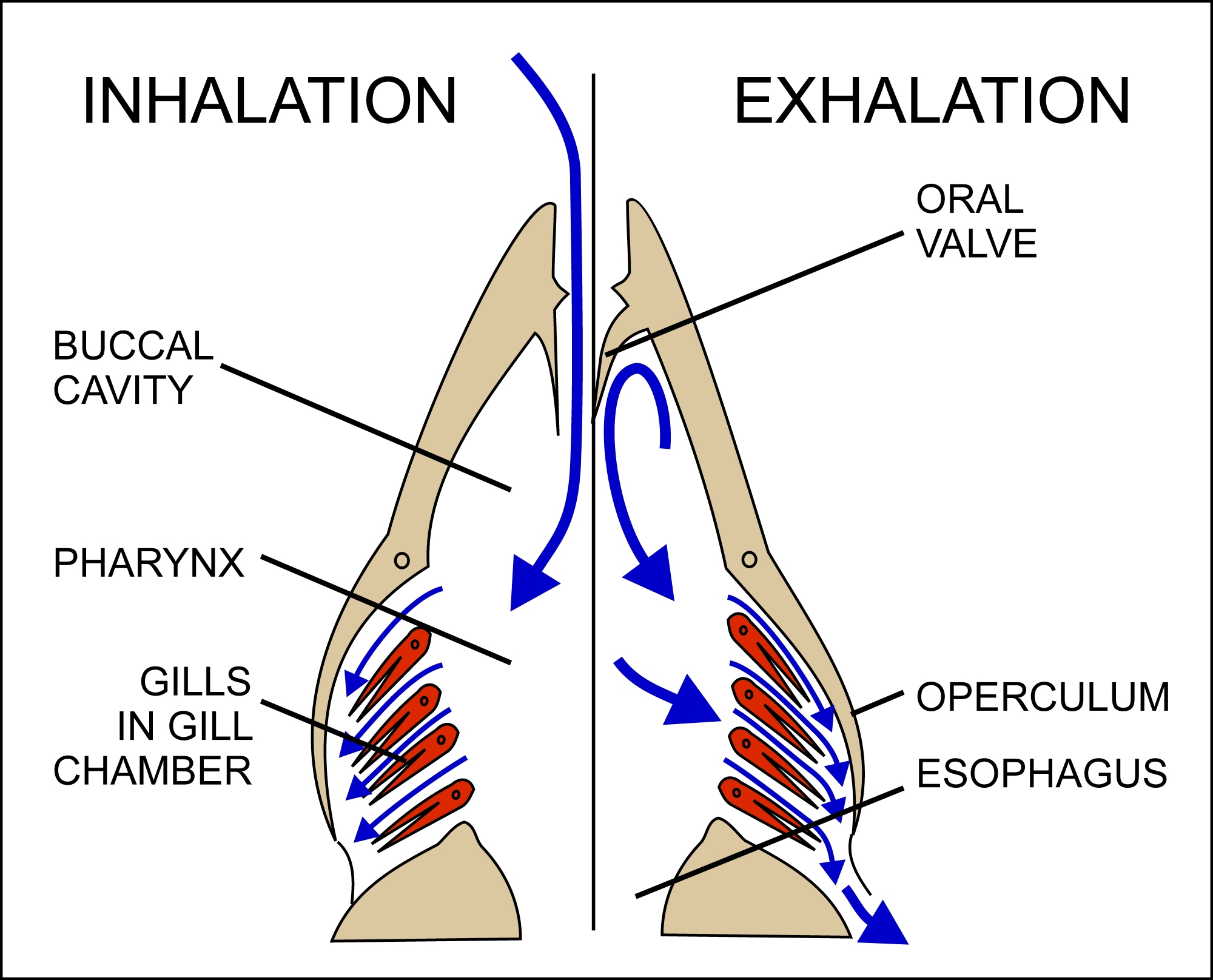

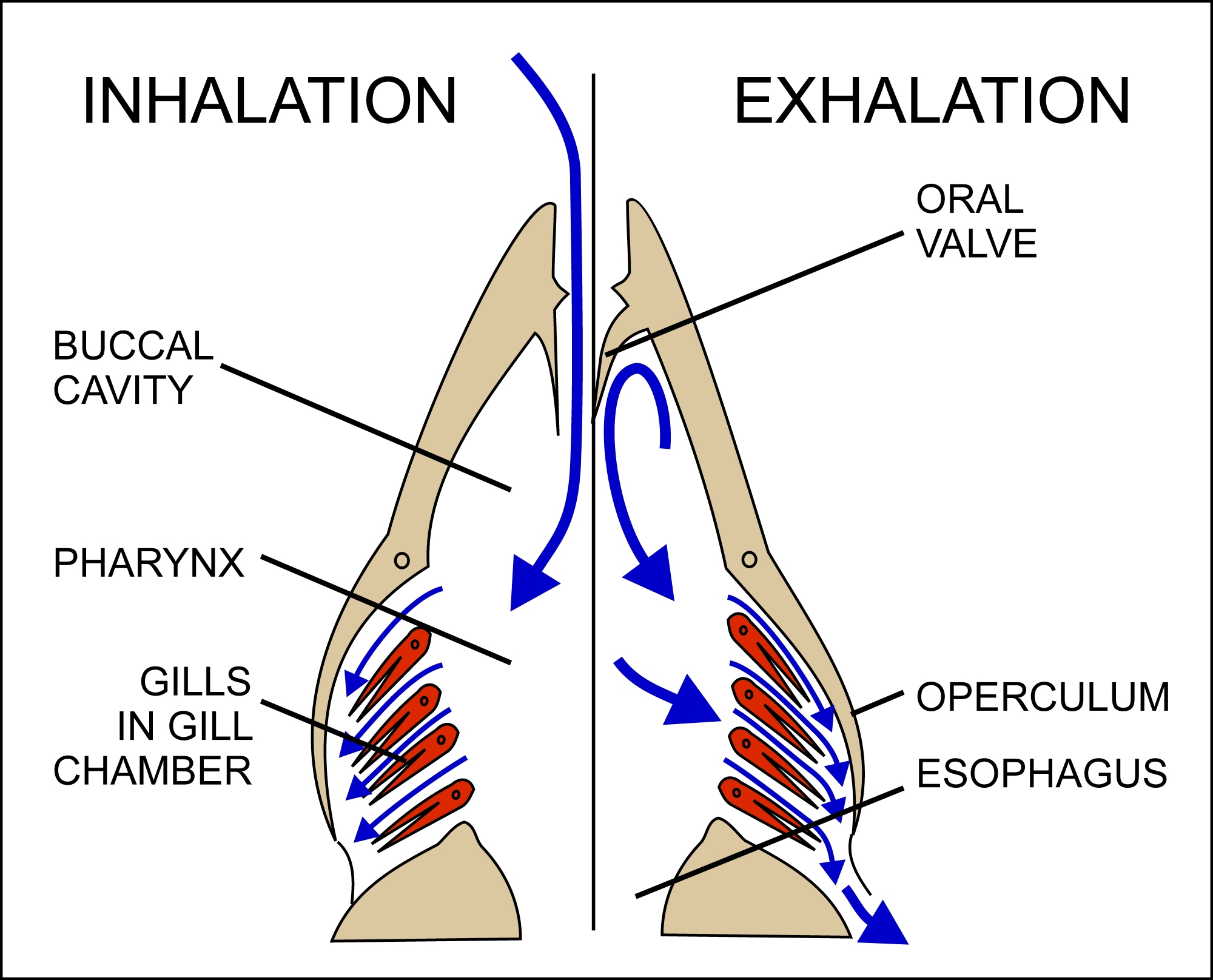

In bony fish, the gills lie in a branchial chamber covered by a bony operculum. The great majority of bony fish species have five pairs of gills, although a few have lost some over the course of evolution. The operculum can be important in adjusting the pressure of water inside of the pharynx to allow proper ventilation of the gills, so that bony fish do not have to rely on ram ventilation (and hence near constant motion) to breathe. Valves inside the mouth keep the water from escaping.

The gill arches of bony fish typically have no septum, so that the gills alone project from the arch, supported by individual gill rays. Some species retain gill rakers. Though all but the most primitive bony fish lack a spiracle, the pseudobranch associated with it often remains, being located at the base of the operculum. This is, however, often greatly reduced, consisting of a small mass of cells without any remaining gill-like structure.

In bony fish, the gills lie in a branchial chamber covered by a bony operculum. The great majority of bony fish species have five pairs of gills, although a few have lost some over the course of evolution. The operculum can be important in adjusting the pressure of water inside of the pharynx to allow proper ventilation of the gills, so that bony fish do not have to rely on ram ventilation (and hence near constant motion) to breathe. Valves inside the mouth keep the water from escaping.

The gill arches of bony fish typically have no septum, so that the gills alone project from the arch, supported by individual gill rays. Some species retain gill rakers. Though all but the most primitive bony fish lack a spiracle, the pseudobranch associated with it often remains, being located at the base of the operculum. This is, however, often greatly reduced, consisting of a small mass of cells without any remaining gill-like structure.

Marine

Marine

The circulatory systems of all

The circulatory systems of all

Fish swim by contracting longitudinal red muscle and obliquely oriented white muscles. The red muscle is aerobic and needs oxygen which is supplied by myoglobin. The white muscle is anaerobic and it does not need oxygen. Red muscles are used for sustained activity such as cruising at slow speeds on ocean migrations. White muscles are used for bursts of activity, such as jumping or sudden bursts of speed for catching prey.

Mostly fish have white muscles, but the muscles of some fishes, such as scombroids and salmonids, range from pink to dark red. The red myotomal muscles derive their colour from myoglobin, an oxygen-binding molecule, which tuna express in quantities far higher than most other fish. The oxygen-rich blood further enables energy delivery to their muscles.

Most fish move by alternately contracting paired sets of muscles on either side of the backbone. These contractions form S-shaped curves that move down the body. As each curve reaches the back fin, backward force is applied to the water, and in conjunction with the fins, moves the fish forward. The fish's fins function like an airplane's flaps. Fins also increase the tail's surface area, increasing speed. The streamlined body of the fish decreases the amount of friction from the water.

A typical characteristic of many animals that utilize undulatory locomotion is that they have segmented muscles, or blocks of

Fish swim by contracting longitudinal red muscle and obliquely oriented white muscles. The red muscle is aerobic and needs oxygen which is supplied by myoglobin. The white muscle is anaerobic and it does not need oxygen. Red muscles are used for sustained activity such as cruising at slow speeds on ocean migrations. White muscles are used for bursts of activity, such as jumping or sudden bursts of speed for catching prey.

Mostly fish have white muscles, but the muscles of some fishes, such as scombroids and salmonids, range from pink to dark red. The red myotomal muscles derive their colour from myoglobin, an oxygen-binding molecule, which tuna express in quantities far higher than most other fish. The oxygen-rich blood further enables energy delivery to their muscles.

Most fish move by alternately contracting paired sets of muscles on either side of the backbone. These contractions form S-shaped curves that move down the body. As each curve reaches the back fin, backward force is applied to the water, and in conjunction with the fins, moves the fish forward. The fish's fins function like an airplane's flaps. Fins also increase the tail's surface area, increasing speed. The streamlined body of the fish decreases the amount of friction from the water.

A typical characteristic of many animals that utilize undulatory locomotion is that they have segmented muscles, or blocks of

The body of a fish is denser than water, so fish must compensate for the difference or they will sink. Many bony fishes have an internal organ called a swim bladder, or gas bladder, that adjusts their buoyancy through manipulation of gases. In this way, fish can stay at the current water depth, or ascend or descend without having to waste energy in swimming. The bladder is only found in bony fishes. In the more primitive groups like some

The body of a fish is denser than water, so fish must compensate for the difference or they will sink. Many bony fishes have an internal organ called a swim bladder, or gas bladder, that adjusts their buoyancy through manipulation of gases. In this way, fish can stay at the current water depth, or ascend or descend without having to waste energy in swimming. The bladder is only found in bony fishes. In the more primitive groups like some

Sharks have keen olfactory senses, located in the short duct (which is not fused, unlike bony fish) between the anterior and posterior nasal openings, with some species able to detect as little as one

Sharks have keen olfactory senses, located in the short duct (which is not fused, unlike bony fish) between the anterior and posterior nasal openings, with some species able to detect as little as one

Some fish, such as catfish and sharks, have organs that detect weak electric currents on the order of millivolt. Other fish, like the South American electric fishes Gymnotiformes, can produce weak electric currents, which they use in navigation and social communication. In sharks, the ampullae of Lorenzini are electroreceptor organs. They number in the hundreds to thousands. Sharks use the ampullae of Lorenzini to detect the electromagnetic fields that all living things produce. This helps sharks (particularly the

Some fish, such as catfish and sharks, have organs that detect weak electric currents on the order of millivolt. Other fish, like the South American electric fishes Gymnotiformes, can produce weak electric currents, which they use in navigation and social communication. In sharks, the ampullae of Lorenzini are electroreceptor organs. They number in the hundreds to thousands. Sharks use the ampullae of Lorenzini to detect the electromagnetic fields that all living things produce. This helps sharks (particularly the

File:Oeufs002b,57.png, Egg of

The newly hatched young of oviparous fish are called

''Fish Physiology: Fish Neuroendocrinology''

Academic Press. . * Eddy FB and Handy RD (2012

'' Ecological and Environmental Physiology of Fishes''

Oxford University Press. . * Evans DH, JB Claiborne and S Currie (Eds) (2013

''The Physiology of Fishes''

4th edition, CRC Press. . * Grosell M, Farrell AP and Brauner CJ (2010

''Fish Physiology: The Multifunctional Gut of Fish''

Academic Press. . * Hara TJ and Zielinski B (2006

''Fish Physiology: Sensory Systems Neuroscience''

Academic Press. . * Kapoor BG and Khanna B (2004

"Ichthyology handbook"

Pages 137–140, Springer. . * McKenzie DJ, Farrell AP and Brauner CJ (2007

''Fish Physiology: Primitive Fishes''

Academic Press. . * Sloman KA, Wilson RW and Balshine S (2006

''Behaviour And Physiology of Fish''

Gulf Professional Publishing. . * Wood CM, Farrell AP and Brauner CJ (2011

''Fish Physiology: Homeostasis and Toxicology of Non-Essential Metals''

Academic Press. .

Fish physiology is the scientific study of how the component parts of

Fish physiology is the scientific study of how the component parts of fish

Fish are aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish as well as various extinct related groups. Approximately 95% of ...

function together in the living fish. It can be contrasted with fish anatomy

Fish anatomy is the study of the form or morphology of fish. It can be contrasted with fish physiology, which is the study of how the component parts of fish function together in the living fish. In practice, fish anatomy and fish physiology c ...

, which is the study of the form or morphology

Morphology, from the Greek and meaning "study of shape", may refer to:

Disciplines

* Morphology (archaeology), study of the shapes or forms of artifacts

* Morphology (astronomy), study of the shape of astronomical objects such as nebulae, galaxies ...

of fishes. In practice, fish anatomy and physiology complement each other, the former dealing with the structure of a fish, its organs or component parts and how they are put together, such as might be observed on the dissecting table or under the microscope, and the later dealing with how those components function together in the living fish. For this, at first we need to know about their intestinal morphology.

Respiration

Most fish exchange gases using

Most fish exchange gases using gill

A gill () is a respiratory organ that many aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow respiration on land provided they are ...

s on either side of the pharynx

The pharynx (plural: pharynges) is the part of the throat behind the mouth and nasal cavity, and above the oesophagus and trachea (the tubes going down to the stomach and the lungs). It is found in vertebrates and invertebrates, though its st ...

(throat). Gills are tissues which consist of threadlike structures called filaments. These filaments have many functions and "are involved in ion and water transfer as well as oxygen, carbon dioxide, acid and ammonia exchange. Each filament contains a capillary

A capillary is a small blood vessel from 5 to 10 micrometres (μm) in diameter. Capillaries are composed of only the tunica intima, consisting of a thin wall of simple squamous endothelial cells. They are the smallest blood vessels in the bod ...

network that provides a large surface area for exchanging oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as ...

and carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide ( chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is trans ...

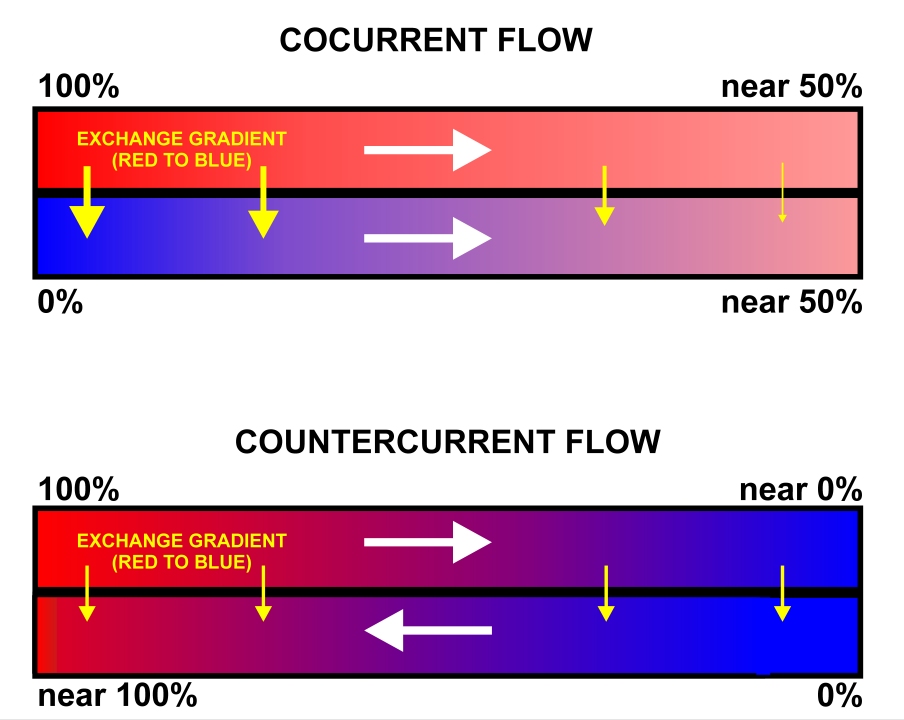

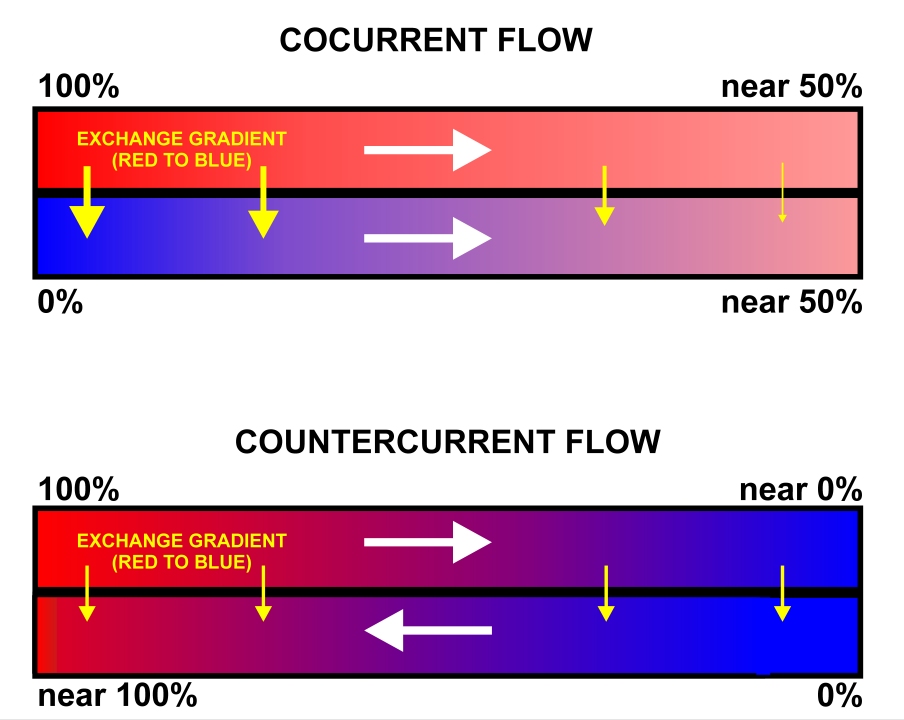

. Fish exchange gases by pulling oxygen-rich water through their mouths and pumping it over their gills. In some fish, capillary blood flows in the opposite direction to the water, causing countercurrent exchange

Countercurrent exchange is a mechanism occurring in nature and mimicked in industry and engineering, in which there is a crossover of some property, usually heat or some chemical, between two flowing bodies flowing in opposite directions to each ...

. The gills push the oxygen-poor water out through openings in the sides of the pharynx.

Fish from multiple groups can live out of the water for extended time periods. Amphibious fish such as the mudskipper can live and move about on land for up to several days, or live in stagnant or otherwise oxygen depleted water. Many such fish can breathe air via a variety of mechanisms. The skin of anguillid eels may absorb oxygen directly. The buccal cavity

The buccal space (also termed the buccinator space) is a fascial space of the head and neck (sometimes also termed fascial tissue spaces or tissue spaces). It is a potential space in the cheek, and is paired on each side. The buccal space is super ...

of the electric eel

The electric eels are a genus, ''Electrophorus'', of neotropical freshwater fish from South America in the family Gymnotidae. They are known for their ability to stun their prey by generating electricity, delivering shocks at up to 860 volt ...

may breathe air. Catfish of the families Loricariidae

The Loricariidae is the largest family of catfish (order Siluriformes), with 92 genera and just over 680 species. Loricariids originate from freshwater habitats of Costa Rica, Panama, and tropical and subtropical South America. These fish are not ...

, Callichthyidae

Callichthyidae is a family of catfishes (order Siluriformes), called armored catfishes due to the two rows of bony plates (or scutes) along the lengths of their bodies. It contains some of the most popular freshwater aquarium fish, such as many ...

, and Scoloplacidae

''Scoloplax'' is the only genus in the catfish (order Siluriformes) family Scoloplacidae, the spiny dwarf catfishes.

Species

The six currently recognized species in this genus are:

* ''Scoloplax baileyi'' Rocha, Lazzarotto & Rapp Py-Daniel, ...

absorb air through their digestive tracts. Lungfish

Lungfish are freshwater vertebrates belonging to the order Dipnoi. Lungfish are best known for retaining ancestral characteristics within the Osteichthyes, including the ability to breathe air, and ancestral structures within Sarcopterygii, i ...

, with the exception of the Australian lungfish, and bichir

Bichirs and the reedfish comprise Polypteridae , a family of archaic ray-finned fishes and the only family in the order Polypteriformes .Helfman GS, Collette BB, Facey DE, Bowen BW. 2009. The Diversity of Fishes. West Sussex, UK: Blackwell Pu ...

s have paired lungs similar to those of tetrapod

Tetrapods (; ) are four-limbed vertebrate animals constituting the superclass Tetrapoda (). It includes extant and extinct amphibians, sauropsids ( reptiles, including dinosaurs and therefore birds) and synapsids ( pelycosaurs, extinct t ...

s and must surface to gulp fresh air through the mouth and pass spent air out through the gills. Gar

Gars are members of the family Lepisosteidae, which are the only surviving members of the Ginglymodi, an ancient holosteian group of ray-finned fish, which first appeared during the Triassic, over 240 million years ago. Gars comprise seven livin ...

and bowfin have a vascularized swim bladder that functions in the same way. Loaches, trahiras, and many catfish

Catfish (or catfishes; order Siluriformes or Nematognathi) are a diverse group of ray-finned fish. Named for their prominent barbels, which resemble a cat's whiskers, catfish range in size and behavior from the three largest species alive ...

breathe by passing air through the gut. Mudskippers breathe by absorbing oxygen across the skin (similar to frogs). A number of fish have evolved so-called accessory breathing organs that extract oxygen from the air. Labyrinth fish (such as gourami

Gouramis, or gouramies , are a group of freshwater anabantiform fishes that comprise the family Osphronemidae. The fish are native to Asia—from the Indian Subcontinent to Southeast Asia and northeasterly towards Korea. The name "gourami", of ...

s and betta

''Betta'' is a large genus of small, active, often colorful, freshwater ray-finned fishes, in the gourami family (biology), family (Osphronemidae). The best known ''Betta'' species is ''B. splendens,'' commonly known as the Siamese fighting fi ...

s) have a labyrinth organ

The Anabantoidei are a suborder of anabantiform ray-finned freshwater fish distinguished by their possession of a lung-like labyrinth organ, which enables them to breathe air. The fish in the Anabantoidei suborder are known as anabantoids or lab ...

above the gills that performs this function. A few other fish have structures resembling labyrinth organs in form and function, most notably snakeheads, pikeheads, and the Clariidae catfish family.

Breathing air is primarily of use to fish that inhabit shallow, seasonally variable waters where the water's oxygen concentration may seasonally decline. Fish dependent solely on dissolved oxygen, such as perch and cichlids, quickly suffocate, while air-breathers survive for much longer, in some cases in water that is little more than wet mud. At the most extreme, some air-breathing fish are able to survive in damp burrows for weeks without water, entering a state of aestivation (summertime hibernation) until water returns.

Air breathing fish can be divided into ''obligate'' air breathers and ''facultative'' air breathers. Obligate air breathers, such as the African lungfish

''Protopterus'' is the genus of four species of lungfish found in Africa. ''Protopterus'' was formerly thought to be the sole genus in the family Protopteridae, but more recent studies have classified it with ''Lepidosiren'' in the family Lepi ...

, are obligated to breathe air periodically or they suffocate. Facultative air breathers, such as the catfish ''Hypostomus plecostomus

''Hypostomus plecostomus'', also known as the suckermouth catfish or the common pleco, is a tropical freshwater fish belonging to the armored catfish family (Loricariidae), named for the longitudinal rows of armor-like scutes that cover the upp ...

'', only breathe air if they need to and can otherwise rely on their gills for oxygen. Most air breathing fish are facultative air breathers that avoid the energetic cost of rising to the surface and the fitness cost of exposure to surface predators.

All basal vertebrates breathe with

All basal vertebrates breathe with gills

A gill () is a respiratory organ that many aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow respiration on land provided they are ...

. The gills are carried right behind the head, bordering the posterior margins of a series of openings from the esophagus

The esophagus ( American English) or oesophagus (British English; both ), non-technically known also as the food pipe or gullet, is an organ in vertebrates through which food passes, aided by peristaltic contractions, from the pharynx to ...

to the exterior. Each gill is supported by a cartilaginous or bony gill arch

Branchial arches, or gill arches, are a series of bony "loops" present in fish, which support the gills. As gills are the primitive condition of vertebrates, all vertebrate embryos develop pharyngeal arches, though the eventual fate of these arc ...

. The gills of vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () (chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, with c ...

s typically develop in the walls of the pharynx

The pharynx (plural: pharynges) is the part of the throat behind the mouth and nasal cavity, and above the oesophagus and trachea (the tubes going down to the stomach and the lungs). It is found in vertebrates and invertebrates, though its st ...

, along a series of gill slits opening to the exterior. Most species employ a countercurrent exchange

Countercurrent exchange is a mechanism occurring in nature and mimicked in industry and engineering, in which there is a crossover of some property, usually heat or some chemical, between two flowing bodies flowing in opposite directions to each ...

system to enhance the diffusion of substances in and out of the gill, with blood and water flowing in opposite directions to each other, which increases the efficiency of oxygen-uptake from the water. Fresh oxygenated water taken in through the mouth is uninterruptedly "pumped" through the gills in one direction, while the blood in the lamellae flows in the opposite direction, creating the countercurrent blood and water flow, on which the fish's survival depends.

The gills are composed of comb-like filaments, the gill lamellae

Lamellae on a gecko's foot.

In surface anatomy, a lamella is a thin plate-like structure, often one amongst many lamellae very close to one another, with open space between. Aside from respiratory organs, they appear in other biological roles ...

, which help increase their surface area for oxygen exchange. When a fish breathes, it draws in a mouthful of water at regular intervals. Then it draws the sides of its throat together, forcing the water through the gill openings, so that it passes over the gills to the outside. The bony fish have three pairs of arches, cartilaginous fish have five to seven pairs, while the primitive jawless fish

Agnatha (, Ancient Greek 'without jaws') is an infraphylum of jawless fish in the phylum Chordata, subphylum Vertebrata, consisting of both present ( cyclostomes) and extinct (conodonts and ostracoderms) species. Among recent animals, cyclosto ...

have seven. The vertebrate ancestor no doubt had more arches, as some of their chordate

A chordate () is an animal of the phylum Chordata (). All chordates possess, at some point during their larval or adult stages, five synapomorphies, or primary physical characteristics, that distinguish them from all the other taxa. These fi ...

relatives have more than 50 pairs of gills.

Higher vertebrates

Amniotes are a clade of tetrapod vertebrates that comprises sauropsids (including all reptiles and birds, and extinct parareptiles and non-avian dinosaurs) and synapsids (including pelycosaurs and therapsids such as mammals). They are distingu ...

do not develop gills, the gill arches form during fetal development

Prenatal development () includes the development of the embryo and of the fetus during a viviparous animal's gestation. Prenatal development starts with fertilization, in the germinal stage of embryonic development, and continues in fetal devel ...

, and lay the basis of essential structures such as jaw

The jaw is any opposable articulated structure at the entrance of the mouth, typically used for grasping and manipulating food. The term ''jaws'' is also broadly applied to the whole of the structures constituting the vault of the mouth and serv ...

s, the thyroid gland, the larynx, the ''columella'' (corresponding to the stapes

The ''stapes'' or stirrup is a bone in the middle ear of humans and other animals which is involved in the conduction of sound vibrations to the inner ear. This bone is connected to the oval window by its annular ligament, which allows the foo ...

in mammals

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur o ...

) and in mammals the malleus and incus. Fish gill slits may be the evolutionary ancestors of the tonsil

The tonsils are a set of lymphoid organs facing into the aerodigestive tract, which is known as Waldeyer's tonsillar ring and consists of the adenoid tonsil, two tubal tonsils, two palatine tonsils, and the lingual tonsils. These organs play ...

s, thymus gland

The thymus is a specialized primary lymphoid organ of the immune system. Within the thymus, thymus cell lymphocytes or ''T cells'' mature. T cells are critical to the adaptive immune system, where the body adapts to specific foreign invaders. T ...

, and Eustachian tubes, as well as many other structures derived from the embryonic branchial pouch

In the embryonic development of vertebrates, pharyngeal pouches form on the endodermal side between the pharyngeal arches. The pharyngeal grooves (or clefts) form the lateral ectodermal surface of the neck region to separate the arches.

The pou ...

es.

Scientists have investigated what part of the body is responsible for maintaining the respiratory rhythm. They found that neuron

A neuron, neurone, or nerve cell is an electrically excitable cell that communicates with other cells via specialized connections called synapses. The neuron is the main component of nervous tissue in all animals except sponges and placozoa. ...

s located in the brainstem of fish are responsible for the genesis of the respiratory rhythm. The position of these neurons is slightly different from the centers of respiratory genesis in mammals but they are located in the same brain compartment, which has caused debates about the homology of respiratory centers between aquatic and terrestrial species. In both aquatic and terrestrial respiration, the exact mechanisms by which neurons can generate this involuntary rhythm are still not completely understood (see Involuntary control of respiration).

Another important feature of the respiratory rhythm is that it is modulated to adapt to the oxygen consumption of the body. As observed in mammals, fish "breathe" faster and heavier when they do physical exercise. The mechanisms by which these changes occur have been strongly debated over more than 100 years between scientists. The authors can be classified in 2 schools:

#Those who think that the major part of the respiratory changes are pre-programmed in the brain, which would imply that neurons from locomotion

Locomotion means the act or ability of something to transport or move itself from place to place.

Locomotion may refer to:

Motion

* Motion (physics)

* Robot locomotion, of man-made devices

By environment

* Aquatic locomotion

* Flight

* Locomo ...

centers of the brain connect to respiratory center

The respiratory center is located in the medulla oblongata and pons, in the brainstem. The respiratory center is made up of three major respiratory groups of neurons, two in the medulla and one in the pons. In the medulla they are the dorsal ...

s in anticipation of movements.

#Those who think that the major part of the respiratory changes result from the detection of muscle contraction, and that respiration is adapted as a consequence of muscular contraction and oxygen consumption. This would imply that the brain possesses some kind of detection mechanisms that would trigger a respiratory response when muscular contraction occurs.

Many now agree that both mechanisms are probably present and complementary, or working alongside a mechanism that can detect changes in oxygen and/or carbon dioxide blood saturation.

Bony fish

In bony fish, the gills lie in a branchial chamber covered by a bony operculum. The great majority of bony fish species have five pairs of gills, although a few have lost some over the course of evolution. The operculum can be important in adjusting the pressure of water inside of the pharynx to allow proper ventilation of the gills, so that bony fish do not have to rely on ram ventilation (and hence near constant motion) to breathe. Valves inside the mouth keep the water from escaping.

The gill arches of bony fish typically have no septum, so that the gills alone project from the arch, supported by individual gill rays. Some species retain gill rakers. Though all but the most primitive bony fish lack a spiracle, the pseudobranch associated with it often remains, being located at the base of the operculum. This is, however, often greatly reduced, consisting of a small mass of cells without any remaining gill-like structure.

In bony fish, the gills lie in a branchial chamber covered by a bony operculum. The great majority of bony fish species have five pairs of gills, although a few have lost some over the course of evolution. The operculum can be important in adjusting the pressure of water inside of the pharynx to allow proper ventilation of the gills, so that bony fish do not have to rely on ram ventilation (and hence near constant motion) to breathe. Valves inside the mouth keep the water from escaping.

The gill arches of bony fish typically have no septum, so that the gills alone project from the arch, supported by individual gill rays. Some species retain gill rakers. Though all but the most primitive bony fish lack a spiracle, the pseudobranch associated with it often remains, being located at the base of the operculum. This is, however, often greatly reduced, consisting of a small mass of cells without any remaining gill-like structure.

Marine

Marine teleost

Teleostei (; Greek ''teleios'' "complete" + ''osteon'' "bone"), members of which are known as teleosts ), is, by far, the largest infraclass in the class Actinopterygii, the ray-finned fishes, containing 96% of all extant species of fish. Tele ...

s also use gills to excrete electrolytes. The gills' large surface area tends to create a problem for fish that seek to regulate the osmolarity

Osmotic concentration, formerly known as osmolarity, is the measure of solute concentration, defined as the number of osmoles (Osm) of solute per litre (L) of solution (osmol/L or Osm/L). The osmolarity of a solution is usually expressed as Osm/L ...

of their internal fluids. Saltwater is less dilute than these internal fluids, so saltwater fish lose large quantities of water osmotically through their gills. To regain the water, they drink large amounts of seawater

Seawater, or salt water, is water from a sea or ocean. On average, seawater in the world's oceans has a salinity of about 3.5% (35 g/L, 35 ppt, 600 mM). This means that every kilogram (roughly one liter by volume) of seawater has appr ...

and excrete the salt

Salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl), a chemical compound belonging to the larger class of salts; salt in the form of a natural crystalline mineral is known as rock salt or halite. Salt is present in vast quant ...

. Freshwater is more dilute than the internal fluids of fish, however, so freshwater fish gain water osmotically through their gills.

In some primitive bony fishes and amphibians, the larva

A larva (; plural larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle.

...

e bear external gills, branching off from the gill arches. These are reduced in adulthood, their function taken over by the gills proper in fishes and by lungs in most amphibians. Some amphibians retain the external larval gills in adulthood, the complex internal gill system as seen in fish apparently being irrevocably lost very early in the evolution of tetrapod

Tetrapods (; ) are four-limbed vertebrate animals constituting the superclass Tetrapoda (). It includes extant and extinct amphibians, sauropsids ( reptiles, including dinosaurs and therefore birds) and synapsids ( pelycosaurs, extinct t ...

s.Clack, J. A. (2002): Gaining ground: the origin and evolution of tetrapods. ''Indiana University Press'', Bloomington, Indiana. 369 pp

Cartilaginous fish

Like other fish, sharks extractoxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as ...

from seawater as it passes over their gill

A gill () is a respiratory organ that many aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow respiration on land provided they are ...

s. Unlike other fish, shark gill slits are not covered, but lie in a row behind the head. A modified slit called a spiracle lies just behind the eye, which assists the shark with taking in water during respiration

Respiration may refer to:

Biology

* Cellular respiration, the process in which nutrients are converted into useful energy in a cell

** Anaerobic respiration, cellular respiration without oxygen

** Maintenance respiration, the amount of cellul ...

and plays a major role in bottom–dwelling sharks. Spiracles are reduced or missing in active pelagic

The pelagic zone consists of the water column of the open ocean, and can be further divided into regions by depth (as illustrated on the right). The word ''pelagic'' is derived . The pelagic zone can be thought of as an imaginary cylinder or w ...

sharks. While the shark is moving, water passes through the mouth and over the gills in a process known as "ram ventilation". While at rest, most sharks pump water over their gills to ensure a constant supply of oxygenated water. A small number of species have lost the ability to pump water through their gills and must swim without rest. These species are ''obligate ram ventilators'' and would presumably asphyxiate

Asphyxia or asphyxiation is a condition of deficient supply of oxygen to the body which arises from abnormal breathing. Asphyxia causes generalized hypoxia, which affects primarily the tissues and organs. There are many circumstances that ca ...

if unable to move. Obligate ram ventilation is also true of some pelagic bony fish species.

The respiration and circulation process begins when deoxygenated blood

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells. Blood in the cir ...

travels to the shark's two-chambered heart

The heart is a muscular organ in most animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels of the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrients to the body, while carrying metabolic waste such as carbon dioxide to t ...

. Here the shark pumps blood to its gills via the ventral aorta

The aorta ( ) is the main and largest artery in the human body, originating from the left ventricle of the heart and extending down to the abdomen, where it splits into two smaller arteries (the common iliac arteries). The aorta distributes o ...

artery

An artery (plural arteries) () is a blood vessel in humans and most animals that takes blood away from the heart to one or more parts of the body (tissues, lungs, brain etc.). Most arteries carry oxygenated blood; the two exceptions are the pu ...

where it branches into afferent brachial arteries. Reoxygenation takes place in the gills and the reoxygenated blood flows into the efferent brachial arteries, which come together to form the dorsal aorta

The dorsal aortae are paired (left and right) embryological vessels which progress to form the descending aorta. The paired dorsal aortae arise from aortic arches that in turn arise from the aortic sac.

The primary dorsal aorta is located deep ...

. The blood flows from the dorsal aorta throughout the body. The deoxygenated blood from the body then flows through the posterior cardinal veins and enters the posterior cardinal sinuses

Paranasal sinuses are a group of four paired air-filled spaces that surround the nasal cavity. The maxillary sinuses are located under the eyes; the frontal sinuses are above the eyes; the ethmoidal sinuses are between the eyes and the sphenoid ...

. From there blood enters the heart ventricle and the cycle repeats.

----

Shark

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch fish characterized by a cartilaginous skeleton, five to seven gill slits on the sides of the head, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the clade Selachi ...

s and rays

Ray may refer to:

Fish

* Ray (fish), any cartilaginous fish of the superorder Batoidea

* Ray (fish fin anatomy), a bony or horny spine on a fin

Science and mathematics

* Ray (geometry), half of a line proceeding from an initial point

* Ray (gra ...

typically have five pairs of gill slits that open directly to the outside of the body, though some more primitive sharks have six or seven pairs. Adjacent slits are separated by a cartilaginous

Cartilage is a resilient and smooth type of connective tissue. In tetrapods, it covers and protects the ends of long bones at the joints as articular cartilage, and is a structural component of many body parts including the rib cage, the neck a ...

gill arch from which projects a long sheet-like septum, partly supported by a further piece of cartilage called the ''gill ray''. The individual lamellae of the gills lie on either side of the septum. The base of the arch may also support gill raker

Gill rakers in fish are bony or cartilaginous processes that project from the branchial arch (gill arch) and are involved with suspension feeding tiny prey. They are not to be confused with the gill filaments that compose the fleshy part of the ...

s, small projecting elements that help to filter food from the water.

A smaller opening, the spiracle, lies in the back of the first gill slit

Gill slits are individual openings to gills, i.e., multiple gill arches, which lack a single outer cover. Such gills are characteristic of cartilaginous fish such as sharks and rays, as well as deep-branching vertebrates such as lampreys. In con ...

. This bears a small '' pseudobranch'' that resembles a gill in structure, but only receives blood already oxygenated by the true gills. The spiracle is thought to be homologous to the ear opening in higher vertebrates.

Most sharks rely on ram ventilation, forcing water into the mouth and over the gills by rapidly swimming forward. In slow-moving or bottom dwelling species, especially among skates and rays, the spiracle may be enlarged, and the fish breathes by sucking water through this opening, instead of through the mouth.

Chimaeras differ from other cartilagenous fish, having lost both the spiracle and the fifth gill slit. The remaining slits are covered by an operculum, developed from the septum of the gill arch in front of the first gill.

Lampreys and hagfish

Lamprey

Lampreys (sometimes inaccurately called lamprey eels) are an ancient extant lineage of jawless fish of the order Petromyzontiformes , placed in the superclass Cyclostomata. The adult lamprey may be characterized by a toothed, funnel-like s ...

s and hagfish

Hagfish, of the class Myxini (also known as Hyperotreti) and order Myxiniformes , are eel-shaped, slime-producing marine fish (occasionally called slime eels). They are the only known living animals that have a skull but no vertebral column, ...

do not have gill slits as such. Instead, the gills are contained in spherical pouches, with a circular opening to the outside. Like the gill slits of higher fish, each pouch contains two gills. In some cases, the openings may be fused together, effectively forming an operculum. Lampreys have seven pairs of pouches, while hagfishes may have six to fourteen, depending on the species. In the hagfish, the pouches connect with the pharynx internally. In adult lampreys, a separate respiratory tube develops beneath the pharynx proper, separating food and water from respiration by closing a valve at its anterior end.

Circulation

vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () (chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, with c ...

s are ''closed'', just as in humans. Still, the systems of fish

Fish are aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish as well as various extinct related groups. Approximately 95% of ...

, amphibians, reptiles, and bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweig ...

s show various stages of the evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

of the circulatory system

The blood circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the entire body of a human or other vertebrate. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, tha ...

. In fish, the system has only one circuit, with the blood being pumped through the capillaries of the gill

A gill () is a respiratory organ that many aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow respiration on land provided they are ...

s and on to the capillaries of the body tissues. This is known as ''single cycle'' circulation. The heart of fish is therefore only a single pump (consisting of two chambers). Fish have a closed-loop circulatory system. The heart

The heart is a muscular organ in most animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels of the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrients to the body, while carrying metabolic waste such as carbon dioxide to t ...

pumps the blood in a single loop throughout the body. In most fish, the heart consists of four parts, including two chambers and an entrance and exit. The first part is the sinus venosus

The sinus venosus is a large quadrangular cavity which precedes the atrium on the venous side of the chordate heart. In mammals, it exists distinctly only in the embryonic heart, where it is found between the two venae cavae. However, the sinus v ...

, a thin-walled sac that collects blood from the fish's vein

Veins are blood vessels in humans and most other animals that carry blood towards the heart. Most veins carry deoxygenated blood from the tissues back to the heart; exceptions are the pulmonary and umbilical veins, both of which carry oxygenat ...

s before allowing it to flow to the second part, the atrium

Atrium may refer to:

Anatomy

* Atrium (heart), an anatomical structure of the heart

* Atrium, the genital structure next to the genital aperture in the reproductive system of gastropods

* Atrium of the ventricular system of the brain

* Pulmona ...

, which is a large muscular chamber. The atrium serves as a one-way antechamber, sends blood to the third part, ventricle. The ventricle is another thick-walled, muscular chamber and it pumps the blood, first to the fourth part, bulbus arteriosus, a large tube, and then out of the heart. The bulbus arteriosus connects to the aorta

The aorta ( ) is the main and largest artery in the human body, originating from the left ventricle of the heart and extending down to the abdomen, where it splits into two smaller arteries (the common iliac arteries). The aorta distributes o ...

, through which blood flows to the gills

A gill () is a respiratory organ that many aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow respiration on land provided they are ...

for oxygenation.

In amphibians and most reptiles, a double circulatory system is used, but the heart is not always completely separated into two pumps. Amphibians have a three-chambered heart

The heart is a muscular organ in most animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels of the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrients to the body, while carrying metabolic waste such as carbon dioxide to t ...

.

Digestion

Jaws

Jaws or Jaw may refer to:

Anatomy

* Jaw, an opposable articulated structure at the entrance of the mouth

** Mandible, the lower jaw

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Jaws (James Bond), a character in ''The Spy Who Loved Me'' and ''Moonraker''

* ...

allow fish to eat a wide variety of food, including plants and other organisms. Fish ingest food through the mouth and break it down in the esophagus

The esophagus ( American English) or oesophagus (British English; both ), non-technically known also as the food pipe or gullet, is an organ in vertebrates through which food passes, aided by peristaltic contractions, from the pharynx to ...

. In the stomach, food is further digested and, in many fish, processed in finger-shaped pouches called pyloric caeca

Starfish or sea stars are star-shaped echinoderms belonging to the class Asteroidea (). Common usage frequently finds these names being also applied to ophiuroids, which are correctly referred to as brittle stars or basket stars. Starfish a ...

, which secrete digestive enzymes and absorb nutrients. Organs such as the liver

The liver is a major organ only found in vertebrates which performs many essential biological functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the synthesis of proteins and biochemicals necessary for digestion and growth. In humans, it ...

and pancreas

The pancreas is an organ of the digestive system and endocrine system of vertebrates. In humans, it is located in the abdomen behind the stomach and functions as a gland. The pancreas is a mixed or heterocrine gland, i.e. it has both an en ...

add enzymes and various chemicals as the food moves through the digestive tract. The intestine completes the process of digestion and nutrient absorption.

In most vertebrates, digestion is a four-stage process involving the main structures of the digestive tract

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans and ...

, starting with ingestion, placing food into the mouth, and concluding with the excretion of undigested material through the anus. From the mouth, the food moves to the stomach, where as bolus it is broken down chemically. It then moves to the intestine, where the process of breaking the food down into simple molecules continues and the results are absorbed as nutrients into the circulatory and lymphatic system.

Although the precise shape and size of the stomach varies widely among different vertebrates, the relative positions of the oesophageal and duodenal openings remain relatively constant. As a result, the organ always curves somewhat to the left before curving back to meet the pyloric sphincter. However, lamprey

Lampreys (sometimes inaccurately called lamprey eels) are an ancient extant lineage of jawless fish of the order Petromyzontiformes , placed in the superclass Cyclostomata. The adult lamprey may be characterized by a toothed, funnel-like s ...

s, hagfish

Hagfish, of the class Myxini (also known as Hyperotreti) and order Myxiniformes , are eel-shaped, slime-producing marine fish (occasionally called slime eels). They are the only known living animals that have a skull but no vertebral column, ...

es, chimaeras, lungfish

Lungfish are freshwater vertebrates belonging to the order Dipnoi. Lungfish are best known for retaining ancestral characteristics within the Osteichthyes, including the ability to breathe air, and ancestral structures within Sarcopterygii, i ...

es, and some teleost

Teleostei (; Greek ''teleios'' "complete" + ''osteon'' "bone"), members of which are known as teleosts ), is, by far, the largest infraclass in the class Actinopterygii, the ray-finned fishes, containing 96% of all extant species of fish. Tele ...

fish have no stomach at all, with the oesophagus opening directly into the intestine. These animals all consume diets that either require little storage of food, or no pre-digestion with gastric juices, or both.

The small intestine is the part of the digestive tract following the stomach and followed by the large intestine

The large intestine, also known as the large bowel, is the last part of the gastrointestinal tract and of the digestive system in tetrapods. Water is absorbed here and the remaining waste material is stored in the rectum as feces before bein ...

, and is where much of the digestion

Digestion is the breakdown of large insoluble food molecules into small water-soluble food molecules so that they can be absorbed into the watery blood plasma. In certain organisms, these smaller substances are absorbed through the small intest ...

and absorption of food takes place. In fish, the divisions of the small intestine are not clear, and the terms ''anterior'' or ''proximal'' intestine may be used instead of duodenum.

The small intestine is found in all teleost

Teleostei (; Greek ''teleios'' "complete" + ''osteon'' "bone"), members of which are known as teleosts ), is, by far, the largest infraclass in the class Actinopterygii, the ray-finned fishes, containing 96% of all extant species of fish. Tele ...

s, although its form and length vary enormously between species. In teleosts, it is relatively short, typically around one and a half times the length of the fish's body. It commonly has a number of ''pyloric caeca'', small pouch-like structures along its length that help to increase the overall surface area of the organ for digesting food. There is no ileocaecal valve in teleosts, with the boundary between the small intestine and the rectum being marked only by the end of the digestive epithelium.

There is no small intestine as such in non-teleost fish, such as shark

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch fish characterized by a cartilaginous skeleton, five to seven gill slits on the sides of the head, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the clade Selachi ...

s, sturgeons, and lungfish

Lungfish are freshwater vertebrates belonging to the order Dipnoi. Lungfish are best known for retaining ancestral characteristics within the Osteichthyes, including the ability to breathe air, and ancestral structures within Sarcopterygii, i ...

. Instead, the digestive part of the gut forms a spiral intestine, connecting the stomach to the rectum. In this type of gut, the intestine itself is relatively straight, but has a long fold running along the inner surface in a spiral fashion, sometimes for dozens of turns. This valve greatly increases both the surface area and the effective length of the intestine. The lining of the spiral intestine is similar to that of the small intestine in teleosts and non-mammalian tetrapods. In lamprey

Lampreys (sometimes inaccurately called lamprey eels) are an ancient extant lineage of jawless fish of the order Petromyzontiformes , placed in the superclass Cyclostomata. The adult lamprey may be characterized by a toothed, funnel-like s ...

s, the spiral valve is extremely small, possibly because their diet requires little digestion. Hagfish

Hagfish, of the class Myxini (also known as Hyperotreti) and order Myxiniformes , are eel-shaped, slime-producing marine fish (occasionally called slime eels). They are the only known living animals that have a skull but no vertebral column, ...

have no spiral valve at all, with digestion occurring for almost the entire length of the intestine, which is not subdivided into different regions.

The large intestine

The large intestine, also known as the large bowel, is the last part of the gastrointestinal tract and of the digestive system in tetrapods. Water is absorbed here and the remaining waste material is stored in the rectum as feces before bein ...

is the last part of the digestive system normally found in vertebrate animals. Its function is to absorb water from the remaining indigestible food matter, and then to pass useless waste material from the body. In fish, there is no true large intestine, but simply a short rectum connecting the end of the digestive part of the gut to the cloaca. In shark

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch fish characterized by a cartilaginous skeleton, five to seven gill slits on the sides of the head, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the clade Selachi ...

s, this includes a ''rectal gland'' that secretes salt to help the animal maintain osmotic

Osmosis (, ) is the spontaneous net movement or diffusion of solvent molecules through a selectively-permeable membrane from a region of high water potential (region of lower solute concentration) to a region of low water potential (region o ...

balance with the seawater. The gland somewhat resembles a caecum in structure, but is not a homologous structure.

As with many aquatic animals, most fish release their nitrogenous wastes as ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous wa ...

. Some of the wastes diffuse

Diffusion is the net movement of anything (for example, atoms, ions, molecules, energy) generally from a region of higher concentration to a region of lower concentration. Diffusion is driven by a gradient in Gibbs free energy or chemical p ...

through the gills. Blood wastes are filtered

Filtration is a physical separation process that separates solid matter and fluid from a mixture using a ''filter medium'' that has a complex structure through which only the fluid can pass. Solid particles that cannot pass through the filter m ...

by the kidney

The kidneys are two reddish-brown bean-shaped organs found in vertebrates. They are located on the left and right in the retroperitoneal space, and in adult humans are about in length. They receive blood from the paired renal arteries; blo ...

s.

Saltwater fish tend to lose water because of osmosis

Osmosis (, ) is the spontaneous net movement or diffusion of solvent molecules through a selectively-permeable membrane from a region of high water potential (region of lower solute concentration) to a region of low water potential (region o ...

. Their kidneys return water to the body. The reverse happens in freshwater fish

Freshwater fish are those that spend some or all of their lives in fresh water, such as rivers and lakes, with a salinity of less than 1.05%. These environments differ from marine conditions in many ways, especially the difference in levels of ...

: they tend to gain water osmotically. Their kidneys produce dilute urine for excretion. Some fish have specially adapted kidneys that vary in function, allowing them to move from freshwater to saltwater.

In sharks, digestion can take a long time. The food moves from the mouth to a J-shaped stomach, where it is stored and initial digestion occurs. Unwanted items may never get past the stomach, and instead the shark either vomits or turns its stomachs inside out and ejects unwanted items from its mouth. One of the biggest differences between the digestive systems of sharks and mammals is that sharks have much shorter intestines. This short length is achieved by the spiral valve

A spiral valve or scroll valve is the corkscrew-shaped lower portion of the intestine of some sharks, Acipenseriformes (sturgeon and paddlefish), rays, skates, bichirs, Lepisosteiformes (gars), and lungfishes. A modification of the ileum, the s ...

with multiple turns within a single short section instead of a long tube-like intestine. The valve provides a long surface area, requiring food to circulate inside the short gut until fully digested, when remaining waste products pass into the cloaca.

Endocrine system

Regulation of social behaviour

Oxytocin is a group ofneuropeptide

Neuropeptides are chemical messengers made up of small chains of amino acids that are synthesized and released by neurons. Neuropeptides typically bind to G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) to modulate neural activity and other tissues like the ...

s found in most vertebrates. One form of oxytocin functions as a hormone

A hormone (from the Greek participle , "setting in motion") is a class of signaling molecules in multicellular organisms that are sent to distant organs by complex biological processes to regulate physiology and behavior. Hormones are require ...

which is associated with

human love. In 2012, researchers injected cichlids from the social species '' Neolamprologus pulcher'', either with this form of isotocin or with a control saline solution. They found isotocin increased "responsiveness to social information", which suggests "it is a key regulator of social behavior that has evolved and endured since ancient times".

Effects of pollution

Fish canbioaccumulate

Bioaccumulation is the gradual accumulation of substances, such as pesticides or other chemicals, in an organism. Bioaccumulation occurs when an organism absorbs a substance at a rate faster than that at which the substance is lost or eliminated ...

pollutants that are discharged into waterways. Estrogenic compounds found in pesticides, birth control, plastics, plants, fungi, bacteria, and synthetic drugs leeched into rivers are affecting the endocrine system

The endocrine system is a messenger system comprising feedback loops of the hormones released by internal glands of an organism directly into the circulatory system, regulating distant target organs. In vertebrates, the hypothalamus is the neu ...

s of native species. In Boulder, Colorado, white sucker

The white sucker (''Catostomus commersonii)'' is a species of freshwater cypriniform fish inhabiting the upper Midwest and Northeast in North America, but it is also found as far south as Georgia and as far west as New Mexico. The fish is common ...

fish found downstream of a municipal waste water treatment plant exhibit impaired or abnormal sexual development. The fish have been exposed to higher levels of estrogen, and leading to feminized fish. Males display female reproductive organs, and both sexes have reduced fertility, and a higher hatch mortality.

Freshwater habitats in the United States are widely contaminated by the common pesticide atrazine

Atrazine is a chlorinated herbicide of the triazine class. It is used to prevent pre-emergence broadleaf weeds in crops such as maize (corn), soybean and sugarcane and on turf, such as golf courses and residential lawns. Atrazine's primary manu ...

. There is controversy over the degree to which this pesticide harms the endocrine systems of freshwater fish and amphibians. Non-industry-funded researchers consistently report harmful effects while industry-funded researchers consistently report no harmful effects.

In the marine ecosystem, organochlorine

An organochloride, organochlorine compound, chlorocarbon, or chlorinated hydrocarbon is an organic compound containing at least one covalently bonded atom of chlorine. The chloroalkane class (alkanes with one or more hydrogens substituted by chlo ...

contaminants like pesticides, herbicides (DDT), and chlordan are accumulating within fish tissue and disrupting their endocrine system. High frequencies of infertility and high levels of organochlorines have been found in bonnethead shark

The bonnethead (''Sphyrna tiburo''), also called a bonnet shark or shovelhead, is a small member of the hammerhead shark genus ''Sphyrna'', and part of the family Sphyrnidae. It is an abundant species in the littoral zone of the North Atlantic ...

s along the Gulf Coast of Florida. These endocrine-disrupting compounds are similar in structure to naturally occurring hormones in fish. They can modulate hormonal interactions in fish by:

* binding to cellular receptors, causing unpredictable and abnormal cell activity

* blocking receptor sites, inhibiting activity

* promoting the creation of extra receptor sites, amplifying the effects of the hormone or compound

* interacting with naturally occurring hormones, changing their shape and impact

* affecting hormone synthesis or metabolism, causing an improper balance or quantity of hormones

Osmoregulation

Two major types ofosmoregulation

Osmoregulation is the active regulation of the osmotic pressure of an organism's body fluids, detected by osmoreceptors, to maintain the homeostasis of the organism's water content; that is, it maintains the fluid balance and the concentration o ...

are osmoconformers and osmoregulators. Osmoconformer

Osmoconformers are marine organisms that maintain an internal environment which is isotonic to their external environment. This means that the osmotic pressure of the organism's cells is equal to the osmotic pressure of their surrounding environme ...

s match their body osmolarity to their environment actively or passively. Most marine invertebrates are osmoconformers, although their ionic composition may be different from that of seawater.

Osmoregulator

Osmoregulation is the active regulation of the osmotic pressure of an organism's body fluids, detected by osmoreceptors, to maintain the homeostasis of the organism's water content; that is, it maintains the fluid balance and the concentration of ...

s tightly regulate their body osmolarity

Osmotic concentration, formerly known as osmolarity, is the measure of solute concentration, defined as the number of osmoles (Osm) of solute per litre (L) of solution (osmol/L or Osm/L). The osmolarity of a solution is usually expressed as Osm/L ...

, which always stays constant, and are more common in the animal kingdom. Osmoregulators actively control salt concentrations despite the salt concentrations in the environment. An example is freshwater fish. The gills actively uptake salt from the environment by the use of mitochondria-rich cells. Water will diffuse into the fish, so it excretes a very hypotonic

In chemical biology, tonicity is a measure of the effective osmotic pressure gradient; the water potential of two solutions separated by a partially-permeable cell membrane. Tonicity depends on the relative concentration of selective membrane-imp ...

(dilute) urine to expel all the excess water. A marine fish

Fish are aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish as well as various extinct related groups. Approximately 95% of ...

has an internal osmotic concentration lower than that of the surrounding seawater, so it tends to lose water and gain salt. It actively excretes salt

Salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl), a chemical compound belonging to the larger class of salts; salt in the form of a natural crystalline mineral is known as rock salt or halite. Salt is present in vast quant ...

out from the gill

A gill () is a respiratory organ that many aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow respiration on land provided they are ...

s. Most fish are stenohaline, which means they are restricted to either salt or fresh water and cannot survive in water with a different salt concentration than they are adapted to. However, some fish show a tremendous ability to effectively osmoregulate across a broad range of salinities; fish with this ability are known as euryhaline species, e.g., salmon

Salmon () is the common name for several commercially important species of euryhaline ray-finned fish from the family Salmonidae, which are native to tributaries of the North Atlantic (genus ''Salmo'') and North Pacific (genus '' Oncorhy ...

. Salmon has been observed to inhabit two utterly disparate environments — marine and fresh water — and it is inherent to adapt to both by bringing in behavioral and physiological modifications.

In contrast to bony fish, with the exception of the coelacanth

The coelacanths ( ) are fish belonging to the order Actinistia that includes two extant species in the genus ''Latimeria'': the West Indian Ocean coelacanth (''Latimeria chalumnae''), primarily found near the Comoro Islands off the east coast ...

, the blood and other tissue of sharks and Chondrichthyes

Chondrichthyes (; ) is a class that contains the cartilaginous fishes that have skeletons primarily composed of cartilage. They can be contrasted with the Osteichthyes or ''bony fishes'', which have skeletons primarily composed of bone tissue. ...

is generally isotonic to their marine environments because of the high concentration of urea

Urea, also known as carbamide, is an organic compound with chemical formula . This amide has two amino groups (–) joined by a carbonyl functional group (–C(=O)–). It is thus the simplest amide of carbamic acid.

Urea serves an important ...

and trimethylamine

Trimethylamine (TMA) is an organic compound with the formula N(CH3)3. It is a colorless, hygroscopic, and flammable tertiary amine. It is a gas at room temperature but is usually sold as a 40% solution in water. (It is also sold in pressurized ...

N-oxide (TMAO), allowing them to be in osmotic

Osmosis (, ) is the spontaneous net movement or diffusion of solvent molecules through a selectively-permeable membrane from a region of high water potential (region of lower solute concentration) to a region of low water potential (region o ...

balance with the seawater. This adaptation prevents most sharks from surviving in freshwater, and they are therefore confined to marine environments. A few exceptions exist, such as the bull shark

The bull shark (''Carcharhinus leucas''), also known as the Zambezi shark (informally zambi) in Africa and Lake Nicaragua shark in Nicaragua, is a species of requiem shark commonly found worldwide in warm, shallow waters along coasts and in ri ...

, which has developed a way to change its kidney

The kidneys are two reddish-brown bean-shaped organs found in vertebrates. They are located on the left and right in the retroperitoneal space, and in adult humans are about in length. They receive blood from the paired renal arteries; blo ...

function to excrete large amounts of urea. When a shark dies, the urea is broken down to ammonia by bacteria, causing the dead body to gradually smell strongly of ammonia.

Sharks have adopted a different, efficient mechanism to conserve water, i.e., osmoregulation. They retain urea in their blood in relatively higher concentration. Urea is damaging to living tissue so, to cope with this problem, some fish retain ''trimethylamine oxide

Trimethylamine ''N''-oxide (TMAO) is an organic compound with the formula (CH3)3NO. It is in the class of amine oxides. Although the anhydrous compound is known, trimethylamine ''N''-oxide is usually encountered as the dihydrate. Both the anhydro ...

''. This provides a better solution to urea's toxicity. Sharks, having slightly higher solute concentration (i.e., above 1000 mOsm which is sea solute concentration), do not drink water like fresh water fish.

Thermoregulation

Homeothermy

Homeothermy, homothermy or homoiothermy is thermoregulation that maintains a stable internal body temperature regardless of external influence. This internal body temperature is often, though not necessarily, higher than the immediate environmen ...

and poikilothermy

A poikilotherm () is an animal whose internal temperature varies considerably. Poikilotherms have to survive and adapt to environmental stress. One of the most important stressors is temperature change, which can lead to alterations in membrane ...

refer to how stable an organism's temperature is. Most endothermic

In thermochemistry, an endothermic process () is any thermodynamic process with an increase in the enthalpy (or internal energy ) of the system.Oxtoby, D. W; Gillis, H.P., Butler, L. J. (2015).''Principle of Modern Chemistry'', Brooks Cole. ...

organisms are homeothermic, like mammals. However, animals with facultative endothermy

An endotherm (from Greek ἔνδον ''endon'' "within" and θέρμη ''thermē'' "heat") is an organism that maintains its body at a metabolically favorable temperature, largely by the use of heat released by its internal bodily functions inste ...

are often poikilothermic, meaning their temperature can vary considerably. Similarly, most fish are ectotherm

An ectotherm (from the Greek () "outside" and () "heat") is an organism in which internal physiological sources of heat are of relatively small or of quite negligible importance in controlling body temperature.Davenport, John. Animal Life ...

s, as all of their heat comes from the surrounding water. However, most are homeotherms because their temperature is very stable.

Most organisms have a preferred temperature range, however some can be acclimated to temperatures colder or warmer than what they are typically used to. An organism's preferred temperature is typically the temperature at which the organism's physiological processes can act at optimal rates. When fish become acclimated to other temperatures, the efficiency of their physiological processes may decrease but will continue to function. This is called the thermal neutral zone

Endothermic organisms known as homeotherms maintain internal temperatures with minimal metabolic regulation within a range of ambient temperatures called the thermal neutral zone (TNZ). Within the TNZ the basal rate of heat production is equal to ...

at which an organism can survive indefinitely.

H.M. Vernon has done work on the death temperature and paralysis temperature (temperature of heat rigor) of various animals. He found that species of the same class

Class or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used differentl ...

showed very similar temperature values, those from the Amphibia

Amphibians are four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terrestrial, fossorial, arbor ...

examined being 38.5 °C, fish 39 °C, Reptilia

Reptiles, as most commonly defined are the animals in the class Reptilia ( ), a paraphyletic grouping comprising all sauropsids except birds. Living reptiles comprise turtles, crocodilians, squamates (lizards and snakes) and rhynchocephalians ( ...

45 °C, and various Molluscs 46 °C.

To cope with low temperatures, some fish

Fish are aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish as well as various extinct related groups. Approximately 95% of ...

have developed the ability to remain functional even when the water temperature is below freezing; some use natural antifreeze

An antifreeze is an additive which lowers the freezing point of a water-based liquid. An antifreeze mixture is used to achieve freezing-point depression for cold environments. Common antifreezes also increase the boiling point of the liquid, all ...

or antifreeze proteins

Antifreeze proteins (AFPs) or ice structuring proteins refer to a class of polypeptides produced by certain animals, plants, fungi and bacteria that permit their survival in temperatures below the freezing point of water. AFPs bind to small i ...

to resist ice crystal formation in their tissues.

Most sharks are "cold-blooded" or, more precisely, poikilotherm

A poikilotherm () is an animal whose internal temperature varies considerably. Poikilotherms have to survive and adapt to environmental stress. One of the most important stressors is temperature change, which can lead to alterations in membrane ...

ic, meaning that their internal body temperature

Thermoregulation is the ability of an organism to keep its body temperature within certain boundaries, even when the surrounding temperature is very different. A thermoconforming organism, by contrast, simply adopts the surrounding temperature ...

matches that of their ambient environment. Members of the family Lamnidae

The Lamnidae are the family of mackerel sharks known as white sharks. They are large, fast-swimming predatory fish found in oceans worldwide, though prefer environments with colder water. The name of the family is formed from the Greek word ''la ...

(such as the shortfin mako shark

The shortfin mako shark (; ; ''Isurus oxyrinchus''), also known as the blue pointer or bonito shark, is a large mackerel shark. It is commonly referred to as the mako shark, as is the longfin mako shark (''Isurus paucus''). The shortfin mako can ...

and the great white shark

The great white shark (''Carcharodon carcharias''), also known as the white shark, white pointer, or simply great white, is a species of large Lamniformes, mackerel shark which can be found in the coastal surface waters of all the major ocean ...

) are homeothermic

Homeothermy, homothermy or homoiothermy is thermoregulation that maintains a stable internal body temperature regardless of external influence. This internal body temperature is often, though not necessarily, higher than the immediate environmen ...

and maintain a higher body temperature than the surrounding water. In these sharks, a strip of aerobic

Aerobic means "requiring air," in which "air" usually means oxygen.

Aerobic may also refer to

* Aerobic exercise, prolonged exercise of moderate intensity

* Aerobics, a form of aerobic exercise

* Aerobic respiration, the aerobic process of cel ...

red muscle located near the center of the body generates the heat, which the body retains via a countercurrent exchange

Countercurrent exchange is a mechanism occurring in nature and mimicked in industry and engineering, in which there is a crossover of some property, usually heat or some chemical, between two flowing bodies flowing in opposite directions to each ...

mechanism by a system of blood vessel

The blood vessels are the components of the circulatory system that transport blood throughout the human body. These vessels transport blood cells, nutrients, and oxygen to the tissues of the body. They also take waste and carbon dioxide away ...

s called the rete mirabile

A rete mirabile (Latin for "wonderful net"; plural retia mirabilia) is a complex of arteries and veins lying very close to each other, found in some vertebrates, mainly warm-blooded ones. The rete mirabile utilizes countercurrent blood flow within ...

("miraculous net"). The common thresher shark has a similar mechanism for maintaining an elevated body temperature, which is thought to have evolved independently.

Tuna

A tuna is a saltwater fish that belongs to the tribe Thunnini, a subgrouping of the Scombridae ( mackerel) family. The Thunnini comprise 15 species across five genera, the sizes of which vary greatly, ranging from the bullet tuna (max len ...

can maintain the temperature of certain parts of their body above the temperature of ambient seawater. For example, bluefin tuna Bluefin tuna is a common name used to refer to several species of tuna

A tuna is a saltwater fish that belongs to the tribe Thunnini, a subgrouping of the Scombridae (mackerel) family. The Thunnini comprise 15 species across five genera, th ...

maintain a core body temperature of , in water as cold as . However, unlike typical endothermic creatures such as mammals and birds, tuna do not maintain temperature within a relatively narrow range. Tuna achieve endothermy

An endotherm (from Greek ἔνδον ''endon'' "within" and θέρμη ''thermē'' "heat") is an organism that maintains its body at a metabolically favorable temperature, largely by the use of heat released by its internal bodily functions inste ...

by conserving the heat generated through normal metabolism

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run c ...

. The rete mirabile

A rete mirabile (Latin for "wonderful net"; plural retia mirabilia) is a complex of arteries and veins lying very close to each other, found in some vertebrates, mainly warm-blooded ones. The rete mirabile utilizes countercurrent blood flow within ...

("wonderful net"), the intertwining of veins and arteries in the body's periphery, transfers heat from venous blood

Venous blood is deoxygenated blood which travels from the peripheral blood vessels, through the venous system into the right atrium of the heart. Deoxygenated blood is then pumped by the right ventricle to the lungs via the pulmonary artery wh ...

to arterial blood

Arterial blood is the oxygenated blood in the circulatory system found in the pulmonary vein, the left chambers of the heart, and in the artery, arteries. It is bright red in color, while venous blood is dark red in color (but looks purple through ...