Fish anatomy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Fish anatomy is the study of the form or morphology of

In many respects, fish anatomy is different from

In many respects, fish anatomy is different from

There are two different skeletal types: the

There are two different skeletal types: the

Fish are vertebrates. All vertebrates are built along the basic

Fish are vertebrates. All vertebrates are built along the basic

The head or

The head or

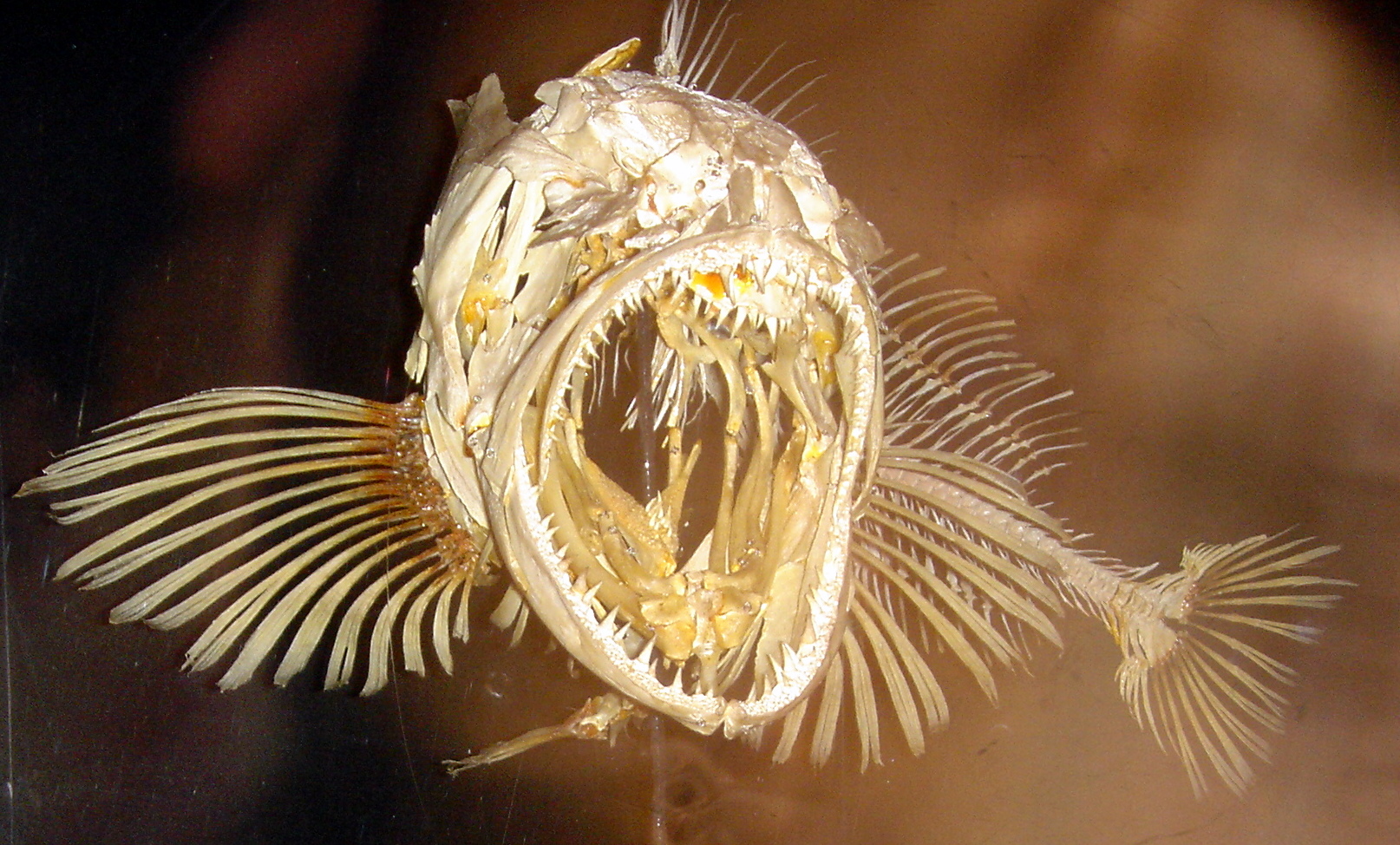

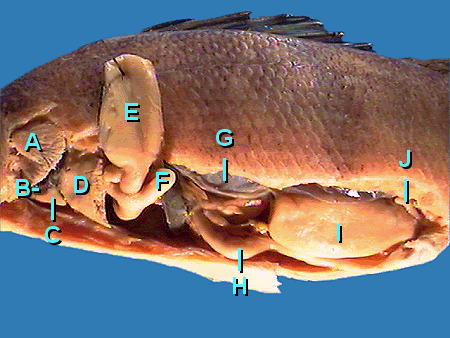

File:Esox luciusZZ.jpg, Skull of a

The vertebrate jaw probably originally evolved in the

The vertebrate jaw probably originally evolved in the  It is thought that the original selective advantage garnered by the jaw was not related to feeding, but to increase respiration efficiency. The jaws were used in the

It is thought that the original selective advantage garnered by the jaw was not related to feeding, but to increase respiration efficiency. The jaws were used in the

The gills, located under the operculum, are a respiratory organ for the extraction of oxygen from water and for the excretion of carbon dioxide. They are not usually visible, but can be seen in some species, such as the

The gills, located under the operculum, are a respiratory organ for the extraction of oxygen from water and for the excretion of carbon dioxide. They are not usually visible, but can be seen in some species, such as the

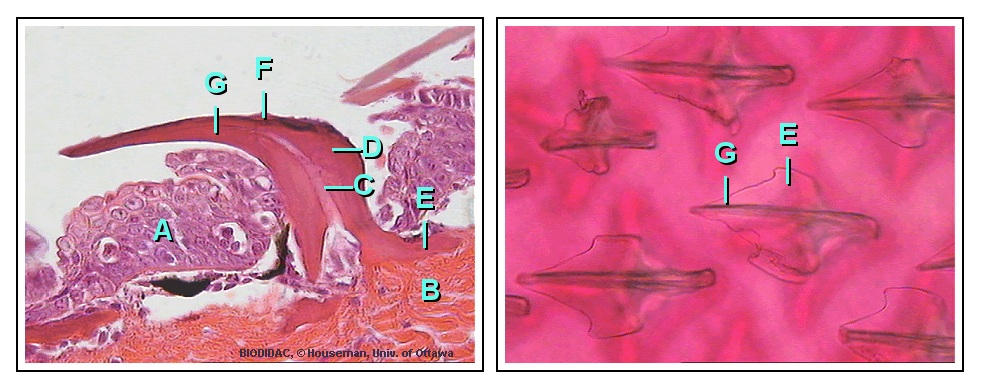

There are four principal types of fish scales that originate from the dermis.

*

There are four principal types of fish scales that originate from the dermis.

*

Another less common type of scale is the

Another less common type of scale is the

The lateral line is a sense organ used to detect movement and vibration in the surrounding water. For example, fish can use their lateral line system to follow the vortices produced by fleeing prey. In most species, it consists of a line of receptors running along each side of the fish.

The lateral line is a sense organ used to detect movement and vibration in the surrounding water. For example, fish can use their lateral line system to follow the vortices produced by fleeing prey. In most species, it consists of a line of receptors running along each side of the fish.

Fins are the most distinctive features of fish. They are either composed of bony spines or rays protruding from the body with skin covering them and joining them together, either in a webbed fashion as seen in most bony fish, or similar to a flipper as seen in sharks. Apart from the tail or caudal fin, fins have no direct connection with the spine and are supported by muscles only. Their principal function is to help the fish swim. Fins can also be used for gliding or crawling, as seen in the flying fish and frogfish. Fins located in different places on the fish serve different purposes, such as moving forward, turning, and keeping an upright position. For every fin, there are a number of fish species in which this particular fin has been lost during evolution.

Fins are the most distinctive features of fish. They are either composed of bony spines or rays protruding from the body with skin covering them and joining them together, either in a webbed fashion as seen in most bony fish, or similar to a flipper as seen in sharks. Apart from the tail or caudal fin, fins have no direct connection with the spine and are supported by muscles only. Their principal function is to help the fish swim. Fins can also be used for gliding or crawling, as seen in the flying fish and frogfish. Fins located in different places on the fish serve different purposes, such as moving forward, turning, and keeping an upright position. For every fin, there are a number of fish species in which this particular fin has been lost during evolution.

, Internet Encyclopedia of Science In cartilaginous and bony fish it consists primarily of red pulp and is normally a somewhat elongated organ as it actually lies inside the serosal lining of the intestine. The only vertebrates lacking a spleen are the lampreys and hagfishes. Even in these animals, there is a diffuse layer of haematopoietic tissue within the gut wall, which has a similar structure to

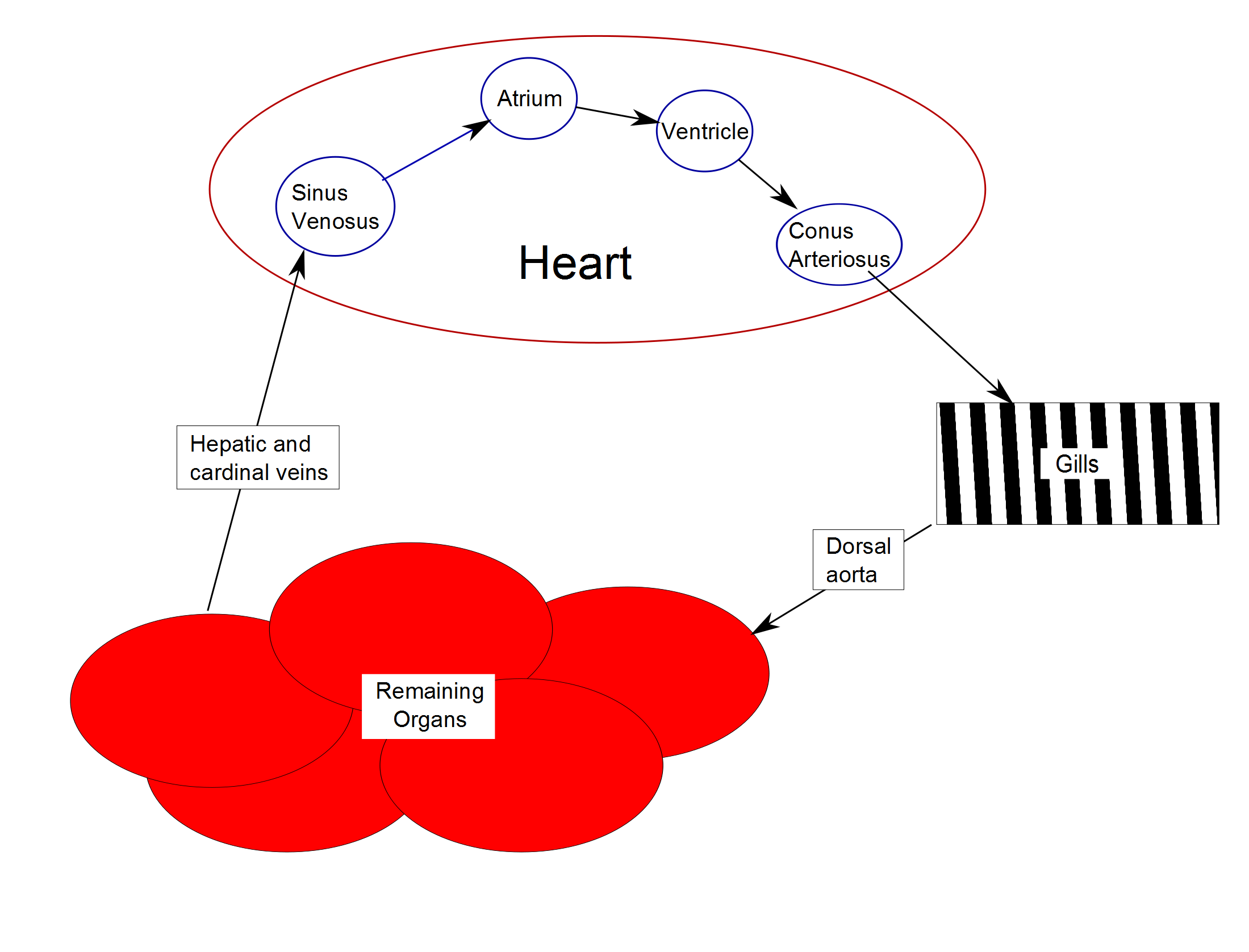

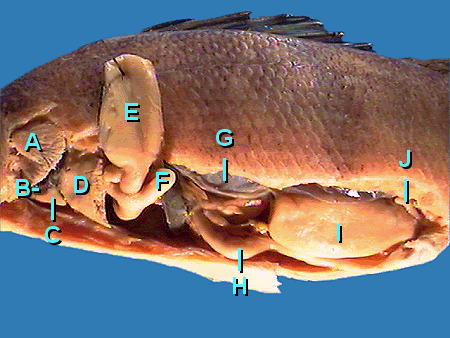

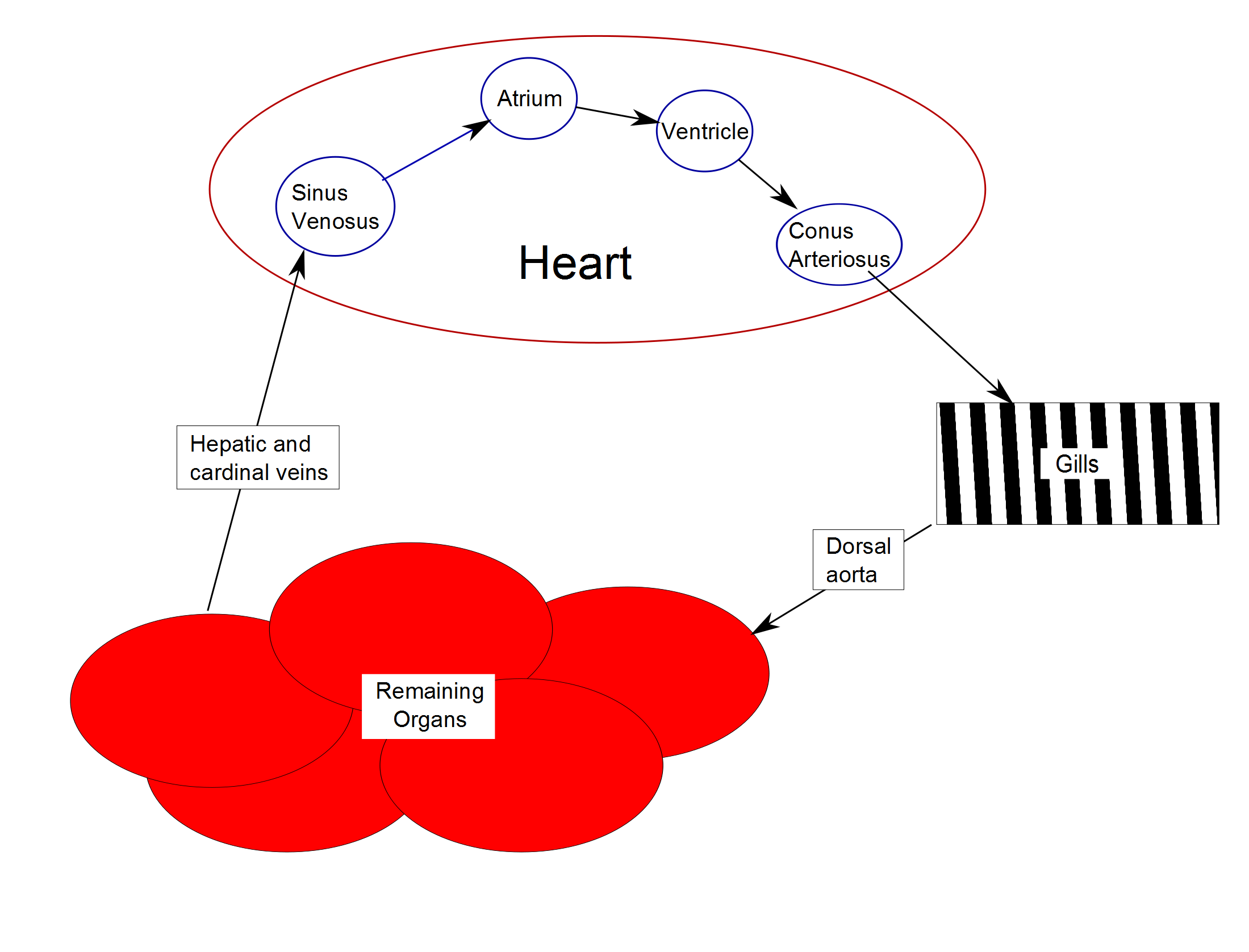

Fish have what is often described as a two-chambered heart, consisting of one atrium to receive blood and one ventricle to pump it, in contrast to three chambers (two atria, one ventricle) of amphibian and most reptile hearts and four chambers (two atria, two ventricles) of mammal and bird hearts. However, the fish heart has entry and exit compartments that may be called chambers, so it is also sometimes described as three-chambered, or four-chambered, depending on what is counted as a chamber. The atrium and ventricle are sometimes considered "true chambers", while the others are considered "accessory chambers".

The four compartments are arranged sequentially:

#

Fish have what is often described as a two-chambered heart, consisting of one atrium to receive blood and one ventricle to pump it, in contrast to three chambers (two atria, one ventricle) of amphibian and most reptile hearts and four chambers (two atria, two ventricles) of mammal and bird hearts. However, the fish heart has entry and exit compartments that may be called chambers, so it is also sometimes described as three-chambered, or four-chambered, depending on what is counted as a chamber. The atrium and ventricle are sometimes considered "true chambers", while the others are considered "accessory chambers".

The four compartments are arranged sequentially:

#

The swim bladder or gas bladder is an internal organ that contributes to the ability of a fish to control its

The swim bladder or gas bladder is an internal organ that contributes to the ability of a fish to control its

Mongabay.com Fish anatomy

Mongabay

Smithsonian exhibit, ''LiveScience'', 13 June 2011. {{Authority control Ichthyology Fishkeeping

fish

Fish are Aquatic animal, aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack Limb (anatomy), limbs with Digit (anatomy), digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and Chondrichthyes, cartilaginous and bony fish as we ...

. It can be contrasted with fish physiology

Fish physiology is the scientific study of how the component parts of fish function together in the living fish. It can be contrasted with fish anatomy, which is the study of the form or morphology of fishes. In practice, fish anatomy and physi ...

, which is the study of how the component parts of fish function together in the living fish. In practice, fish anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having i ...

and fish physiology

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemic ...

complement each other, the former dealing with the structure of a fish, its organs or component parts and how they are put together, such as might be observed on the dissecting table or under the microscope, and the latter dealing with how those components function together in living fish.

The anatomy of fish is often shaped by the physical characteristics of water, the medium in which fish live. Water is much denser

Density (volumetric mass density or specific mass) is the substance's mass per unit of volume. The symbol most often used for density is ''ρ'' (the lower case Greek letter rho), although the Latin letter ''D'' can also be used. Mathematically ...

than air, holds a relatively small amount of dissolved oxygen, and absorbs more light than air does. The body of a fish is divided into a head, trunk and tail, although the divisions between the three are not always externally visible. The skeleton, which forms the support structure inside the fish, is either made of cartilage

Cartilage is a resilient and smooth type of connective tissue. In tetrapods, it covers and protects the ends of long bones at the joints as articular cartilage, and is a structural component of many body parts including the rib cage, the neck ...

(cartilaginous fish

Chondrichthyes (; ) is a class that contains the cartilaginous fishes that have skeletons primarily composed of cartilage. They can be contrasted with the Osteichthyes or ''bony fishes'', which have skeletons primarily composed of bone tissue. ...

) or bone (bony fish

Osteichthyes (), popularly referred to as the bony fish, is a diverse superclass of fish that have skeletons primarily composed of bone tissue. They can be contrasted with the Chondrichthyes, which have skeletons primarily composed of cartil ...

). The main skeletal element is the vertebral column

The vertebral column, also known as the backbone or spine, is part of the axial skeleton. The vertebral column is the defining characteristic of a vertebrate in which the notochord (a flexible rod of uniform composition) found in all chordate ...

, composed of articulating vertebra

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates, Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristi ...

e which are lightweight yet strong. The ribs attach to the spine and there are no limbs or limb girdles. The main external features of the fish, the fins, are composed of either bony or soft spines called ray

Ray may refer to:

Fish

* Ray (fish), any cartilaginous fish of the superorder Batoidea

* Ray (fish fin anatomy), a bony or horny spine on a fin

Science and mathematics

* Ray (geometry), half of a line proceeding from an initial point

* Ray (gr ...

s which, with the exception of the caudal fin

Fins are distinctive anatomical features composed of bony spines or rays protruding from the body of a fish. They are covered with skin and joined together either in a webbed fashion, as seen in most bony fish, or similar to a flipper, as se ...

s, have no direct connection with the spine. They are supported by the muscles which compose the main part of the trunk.

The heart has two chambers and pumps the blood through the respiratory surfaces of the gill

A gill () is a respiratory organ that many aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow respiration on land provided they ar ...

s and then around the body in a single circulatory loop. The eyes are adapted for seeing underwater and have only local vision. There is an inner ear

The inner ear (internal ear, auris interna) is the innermost part of the vertebrate ear. In vertebrates, the inner ear is mainly responsible for sound detection and balance. In mammals, it consists of the bony labyrinth, a hollow cavity in th ...

but no external or middle ear. Low frequency vibrations are detected by the lateral line

The lateral line, also called the lateral line organ (LLO), is a system of sensory organs found in fish, used to detect movement, vibration, and pressure gradients in the surrounding water. The sensory ability is achieved via modified epithelial ...

system of sense organs that run along the length of the sides of fish, which responds to nearby movements and to changes in water pressure.

Sharks and ray

Ray may refer to:

Fish

* Ray (fish), any cartilaginous fish of the superorder Batoidea

* Ray (fish fin anatomy), a bony or horny spine on a fin

Science and mathematics

* Ray (geometry), half of a line proceeding from an initial point

* Ray (gr ...

s are basal fish with numerous primitive anatomical features similar to those of ancient fish, including skeletons composed of cartilage. Their bodies tend to be dorso-ventrally flattened, and they usually have five pairs of gill slits and a large mouth set on the underside of the head. The dermis

The dermis or corium is a layer of skin between the epidermis (with which it makes up the cutis) and subcutaneous tissues, that primarily consists of dense irregular connective tissue and cushions the body from stress and strain. It is divided ...

is covered with separate dermal placoid scales

A fish scale is a small rigid plate that grows out of the skin of a fish. The skin of most jawed fishes is covered with these protective scales, which can also provide effective camouflage through the use of reflection and colouration, as ...

. They have a cloaca

In animal anatomy, a cloaca ( ), plural cloacae ( or ), is the posterior orifice that serves as the only opening for the digestive, reproductive, and urinary tracts (if present) of many vertebrate animals. All amphibians, reptiles and birds, ...

into which the urinary and genital passages open, but not a swim bladder

The swim bladder, gas bladder, fish maw, or air bladder is an internal gas-filled organ that contributes to the ability of many bony fish (but not cartilaginous fish) to control their buoyancy, and thus to stay at their current water depth wit ...

. Cartilaginous fish produce a small number of large yolk

Among animals which produce eggs, the yolk (; also known as the vitellus) is the nutrient-bearing portion of the egg whose primary function is to supply food for the development of the embryo. Some types of egg contain no yolk, for example ...

y eggs. Some species are ovoviviparous, having the young develop internally, but others are oviparous

Oviparous animals are animals that lay their eggs, with little or no other embryonic development within the mother. This is the reproductive method of most fish, amphibians, most reptiles, and all pterosaurs, dinosaurs (including birds), and m ...

and the larvae develop externally in egg cases.

The bony fish lineage shows more derived

Derive may refer to:

*Derive (computer algebra system), a commercial system made by Texas Instruments

* ''Dérive'' (magazine), an Austrian science magazine on urbanism

*Dérive, a psychogeographical concept

See also

*

*Derivation (disambiguation ...

anatomical traits, often with major evolutionary changes from the features of ancient fish. They have a bony skeleton, are generally laterally flattened, have five pairs of gills protected by an operculum, and a mouth at or near the tip of the snout. The dermis is covered with overlapping scales

Scale or scales may refer to:

Mathematics

* Scale (descriptive set theory), an object defined on a set of points

* Scale (ratio), the ratio of a linear dimension of a model to the corresponding dimension of the original

* Scale factor, a number w ...

. Bony fish have a swim bladder which helps them maintain a constant depth in the water column

A water column is a conceptual column of water from the surface of a sea, river or lake to the bottom sediment.Munson, B.H., Axler, R., Hagley C., Host G., Merrick G., Richards C. (2004).Glossary. ''Water on the Web''. University of Minnesota-D ...

, but not a cloaca. They mostly spawn

Spawn or spawning may refer to:

* Spawn (biology), the eggs and sperm of aquatic animals

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Spawn (character), a fictional character in the comic series of the same name and in the associated franchise

** '' Spawn: A ...

a large number of small eggs with little yolk which they broadcast into the water column.

Body

mammalian

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fu ...

anatomy. However, it still shares the same basic body plan

A body plan, ( ), or ground plan is a set of morphological features common to many members of a phylum of animals. The vertebrates share one body plan, while invertebrates have many.

This term, usually applied to animals, envisages a "blueprin ...

from which all vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, with ...

s have evolved: a notochord

In anatomy, the notochord is a flexible rod which is similar in structure to the stiffer cartilage. If a species has a notochord at any stage of its life cycle (along with 4 other features), it is, by definition, a chordate. The notochord consi ...

, rudimentary vertebrae, and a well-defined head and tail.

Fish have a variety of different body plans. At the broadest level, their body is divided into head, trunk, and tail, although the divisions are not always externally visible. The body is often fusiform

Fusiform means having a spindle-like shape that is wide in the middle and tapers at both ends. It is similar to the lemon-shape, but often implies a focal broadening of a structure that continues from one or both ends, such as an aneurysm on a ...

, a streamlined body plan often found in fast-moving fish. They may also be filiform ( eel-shaped) or vermiform (worm-shaped). Fish are often either compressed (laterally thin) or depressed (dorso-ventrally flat).

Skeleton

exoskeleton

An exoskeleton (from Greek ''éxō'' "outer" and ''skeletós'' "skeleton") is an external skeleton that supports and protects an animal's body, in contrast to an internal skeleton ( endoskeleton) in for example, a human. In usage, some of the ...

, which is the stable outer shell of an organism, and the endoskeleton, which forms the support structure inside the body. The skeleton of the fish is made of either cartilage (cartilaginous fishes) or bone (bony fishes). The fins are made up of bony fin rays and, except for the caudal fin, have no direct connection with the spine. They are supported only by the muscles. The ribs attach to the spine.

Bones are rigid organs that form part of the endoskeleton of vertebrates. They function to move, support, and protect the various organs of the body, produce red and white blood cell

White blood cells, also called leukocytes or leucocytes, are the cells of the immune system that are involved in protecting the body against both infectious disease and foreign invaders. All white blood cells are produced and derived from mult ...

s and store mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid chemical compound with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2 ...

s. Bone tissue is a type of dense connective tissue

Connective tissue is one of the four primary types of animal tissue, along with epithelial tissue, muscle tissue, and nervous tissue. It develops from the mesenchyme derived from the mesoderm the middle embryonic germ layer. Connective tiss ...

. Bones come in a variety of shapes and have a complex internal and external structure. They are lightweight, yet strong and hard, in addition to fulfilling their many other biological functions.

Vertebrae

Fish are vertebrates. All vertebrates are built along the basic

Fish are vertebrates. All vertebrates are built along the basic chordate

A chordate () is an animal of the phylum Chordata (). All chordates possess, at some point during their larval or adult stages, five synapomorphies, or primary physical characteristics, that distinguish them from all the other taxa. These fi ...

body plan: a stiff rod running through the length of the animal (vertebral column or notochord), with a hollow tube of nervous tissue (the spinal cord

The spinal cord is a long, thin, tubular structure made up of nervous tissue, which extends from the medulla oblongata in the brainstem to the lumbar region of the vertebral column (backbone). The backbone encloses the central canal of the sp ...

) above it and the gastrointestinal tract

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans and ...

below. In all vertebrates, the mouth is found at, or right below, the anterior

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek language, Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. Th ...

end of the animal, while the anus

The anus (Latin, 'ring' or 'circle') is an opening at the opposite end of an animal's digestive tract from the mouth. Its function is to control the expulsion of feces, the residual semi-solid waste that remains after food digestion, which, ...

opens to the exterior before the end of the body. The remaining part of the body beyond the anus forms a tail with vertebrae and the spinal cord, but no gut.Romer, A.S. (1949): ''The Vertebrate Body.'' W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia. (2nd ed. 1955; 3rd ed. 1962; 4th ed. 1970)

The defining characteristic of a vertebrate is the vertebral column, in which the notochord (a stiff rod of uniform composition) found in all chordates has been replaced by a segmented series of stiffer elements (vertebrae) separated by mobile joints ( intervertebral discs, derived embryonically and evolutionarily from the notochord). However, a few fish have secondarily lost this anatomy, retaining the notochord into adulthood, such as the sturgeon

Sturgeon is the common name for the 27 species of fish belonging to the family Acipenseridae. The earliest sturgeon fossils date to the Late Cretaceous, and are descended from other, earlier acipenseriform fish, which date back to the Early ...

.

The vertebral column consists of a centrum (the central body or spine of the vertebra), vertebral arch

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates, Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristic ...

es which protrude from the top and bottom of the centrum, and various processes which project from the centrum or arches. An arch extending from the top of the centrum is called a neural arch, while the haemal arch or chevron

Chevron (often relating to V-shaped patterns) may refer to:

Science and technology

* Chevron (aerospace), sawtooth patterns on some jet engines

* Chevron (anatomy), a bone

* '' Eulithis testata'', a moth

* Chevron (geology), a fold in rock la ...

is found underneath the centrum in the caudal vertebrae

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates,Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristic i ...

of fish. The centrum of a fish is usually concave at each end (amphicoelous), which limits the motion of the fish. In contrast, the centrum of a mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur ...

is flat at each end (acoelous), a shape that can support and distribute compressive forces.

The vertebrae of lobe-finned fishes consist of three discrete bony elements. The vertebral arch surrounds the spinal cord, and is broadly similar in form to that found in most other vertebrates. Just beneath the arch lies the small plate-like pleurocentrum, which protects the upper surface of the notochord. Below that, a larger arch-shaped intercentrum protects the lower border. Both of these structures are embedded within a single cylindrical mass of cartilage. A similar arrangement was found in primitive tetrapod

Tetrapods (; ) are four-limbed vertebrate animals constituting the superclass Tetrapoda (). It includes extant and extinct amphibians, sauropsids ( reptiles, including dinosaurs and therefore birds) and synapsids ( pelycosaurs, extinct t ...

s, but in the evolutionary line that led to reptiles

Reptiles, as most commonly defined are the animals in the class Reptilia ( ), a paraphyletic grouping comprising all sauropsids except birds. Living reptiles comprise turtles, crocodilians, squamates ( lizards and snakes) and rhynchoceph ...

, mammals and birds, the intercentrum became partially or wholly replaced by an enlarged pleurocentrum, which in turn became the bony vertebral body.

In most ray-finned fishes, including all teleost

Teleostei (; Greek ''teleios'' "complete" + ''osteon'' "bone"), members of which are known as teleosts ), is, by far, the largest infraclass in the class Actinopterygii, the ray-finned fishes, containing 96% of all extant species of fish. Tele ...

s, these two structures are fused with and embedded within a solid piece of bone superficially resembling the vertebral body of mammals. In living amphibian

Amphibians are four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terrestrial, fossorial, arbo ...

s, there is simply a cylindrical piece of bone below the vertebral arch, with no trace of the separate elements present in the early tetrapods.

In cartilaginous fish such as shark

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch fish characterized by a cartilaginous skeleton, five to seven gill slits on the sides of the head, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the clade Selachi ...

s, the vertebrae consist of two cartilaginous tubes. The upper tube is formed from the vertebral arches, but also includes additional cartilaginous structures filling in the gaps between the vertebrae, enclosing the spinal cord in an essentially continuous sheath. The lower tube surrounds the notochord and has a complex structure, often including multiple layers of calcification

Calcification is the accumulation of calcium salts in a body tissue. It normally occurs in the formation of bone, but calcium can be deposited abnormally in soft tissue,Miller, J. D. Cardiovascular calcification: Orbicular origins. ''Nature M ...

.

Lamprey

Lampreys (sometimes inaccurately called lamprey eels) are an ancient extant lineage of jawless fish of the order Petromyzontiformes , placed in the superclass Cyclostomata. The adult lamprey may be characterized by a toothed, funnel-like s ...

s have vertebral arches, but nothing resembling the vertebral bodies found in all higher vertebrates. Even the arches are discontinuous, consisting of separate pieces of arch-shaped cartilage around the spinal cord in most parts of the body, changing to long strips of cartilage above and below in the tail region. Hagfishes lack a true vertebral column, and are therefore not properly considered vertebrates, but a few tiny neural arches are present in the tail. Hagfishes do, however, possess a cranium

The skull is a bone protective cavity for the brain. The skull is composed of four types of bone i.e., cranial bones, facial bones, ear ossicles and hyoid bone. However two parts are more prominent: the cranium and the mandible. In humans, th ...

. For this reason, the vertebrate subphylum is sometimes referred to as "Craniata

A craniate is a member of the Craniata (sometimes called the Craniota), a proposed clade of chordate animals with a skull of hard bone or cartilage. Living representatives are the Myxini (hagfishes), Hyperoartia (including lampreys), and the m ...

" when discussing morphology. Molecular analysis since 1992 has suggested that the hagfishes are most closely related to lampreys, and so also are vertebrates in a monophyletic

In cladistics for a group of organisms, monophyly is the condition of being a clade—that is, a group of taxa composed only of a common ancestor (or more precisely an ancestral population) and all of its lineal descendants. Monophyletic gr ...

sense. Others consider them a sister group of vertebrates in the common taxon of Craniata.

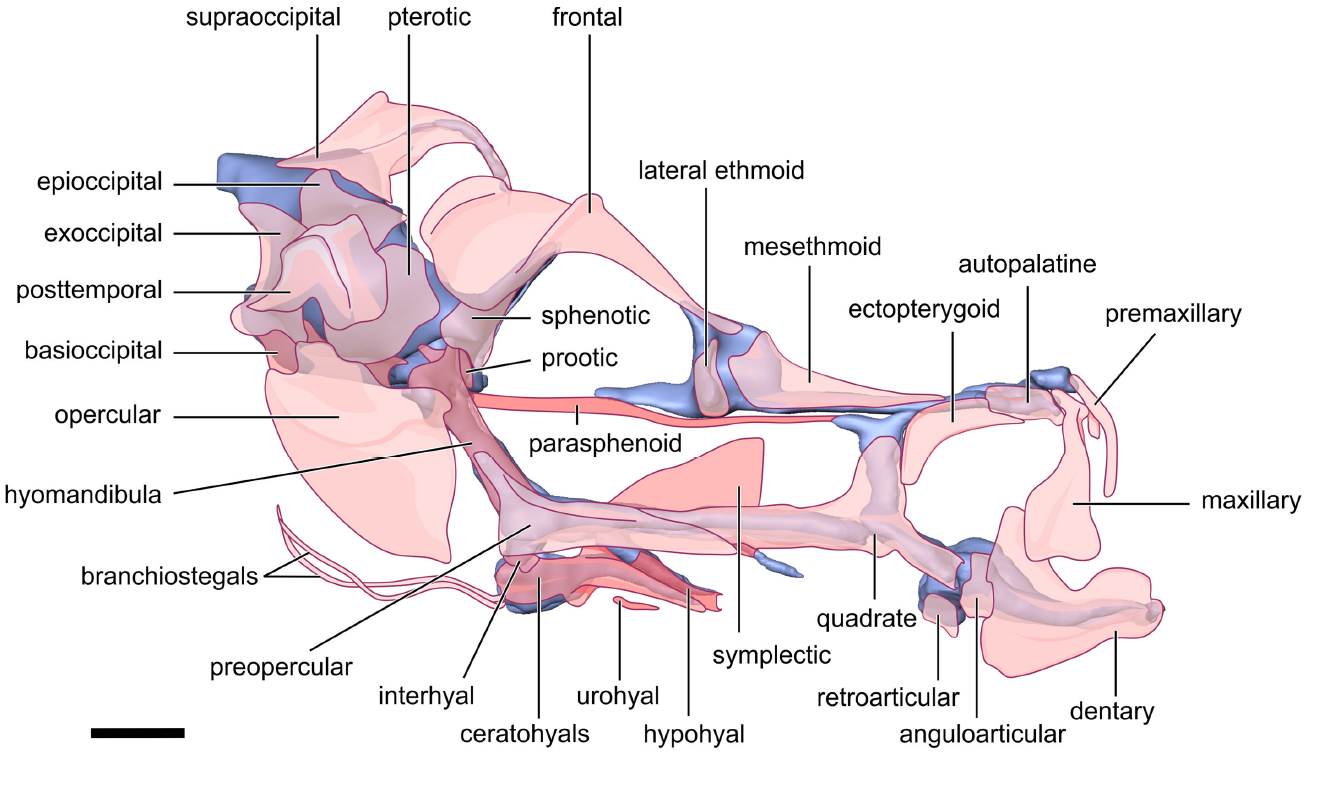

Head

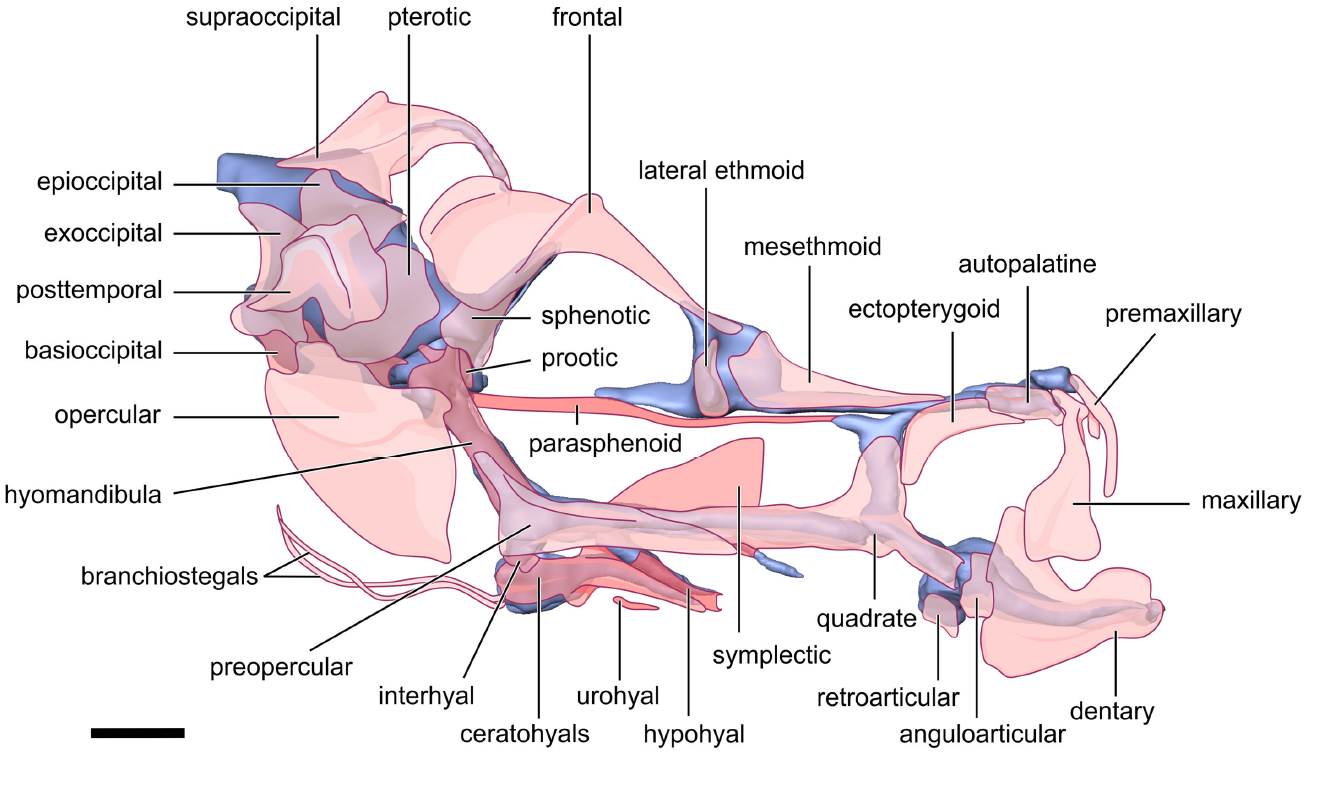

The head or

The head or skull

The skull is a bone protective cavity for the brain. The skull is composed of four types of bone i.e., cranial bones, facial bones, ear ossicles and hyoid bone. However two parts are more prominent: the cranium and the mandible. In humans, th ...

includes the skull roof

The skull roof, or the roofing bones of the skull, are a set of bones covering the brain, eyes and nostrils in bony fishes and all land-living vertebrates. The bones are derived from dermal bone and are part of the dermatocranium.

In compar ...

(a set of bones covering the brain, eyes and nostrils), the snout (from the eye to the forward-most point of the upper jaw), the operculum or gill cover (absent in sharks and jawless fish

Agnatha (, Ancient Greek 'without jaws') is an infraphylum of jawless fish in the phylum Chordata, subphylum Vertebrata, consisting of both present ( cyclostomes) and extinct (conodonts and ostracoderms) species. Among recent animals, cyclosto ...

), and the cheek, which extends from the eye to the preopercle. The operculum and preopercle may or may not have spines. In sharks and some primitive bony fish the spiracle, a small extra gill opening, is found behind each eye.

The skull in fishes is formed from a series of only loosely connected bones. Jawless fish and sharks only possess a cartilaginous endocranium

The endocranium in comparative anatomy is a part of the skull base in vertebrates and it represents the basal, inner part of the cranium. The term is also applied to the outer layer of the dura mater in human anatomy.

Structure

Structurally, ...

, with the upper and lower jaws of cartilaginous fish being separate elements not attached to the skull. Bony fishes have additional dermal bone

A dermal bone or investing bone or membrane bone is a bony structure derived from intramembranous ossification forming components of the vertebrate skeleton including much of the skull, jaws, gill covers, shoulder girdle and fin spines rays ( le ...

, forming a more or less coherent skull roof in lungfish

Lungfish are freshwater vertebrates belonging to the order Dipnoi. Lungfish are best known for retaining ancestral characteristics within the Osteichthyes, including the ability to breathe air, and ancestral structures within Sarcopterygii, i ...

and holost fish. The lower jaw defines a chin.

In lampreys, the mouth is formed into an oral disk. In most jawed fish, however, there are three general configurations. The mouth may be on the forward end of the head (terminal), may be upturned (superior), or may be turned downwards or on the bottom of the fish (subterminal or inferior). The mouth may be modified into a suckermouth adapted for clinging onto objects in fast-moving water.

The simpler structure is found in jawless fish, in which the cranium is represented by a trough-like basket of cartilaginous elements only partially enclosing the brain and associated with the capsules for the inner ears and the single nostril. Distinctively, these fish have no jaws.

Cartilaginous fish such as sharks also have simple, and presumably primitive, skull structures. The cranium is a single structure forming a case around the brain, enclosing the lower surface and the sides, but always at least partially open at the top as a large fontanelle

A fontanelle (or fontanel) (colloquially, soft spot) is an anatomical feature of the infant human skull comprising soft membranous gaps ( sutures) between the cranial bones that make up the calvaria of a fetus or an infant. Fontanelles allow ...

. The most anterior part of the cranium includes a forward plate of cartilage, the rostrum, and capsules to enclose the olfactory

The sense of smell, or olfaction, is the special sense through which smells (or odors) are perceived. The sense of smell has many functions, including detecting desirable foods, hazards, and pheromones, and plays a role in taste.

In humans, ...

organs. Behind these are the orbits, and then an additional pair of capsules enclosing the structure of the inner ear. Finally, the skull tapers towards the rear, where the foramen magnum

The foramen magnum ( la, great hole) is a large, oval-shaped opening in the occipital bone of the skull. It is one of the several oval or circular openings (foramina) in the base of the skull. The spinal cord, an extension of the medulla oblon ...

lies immediately above a single condyle, articulating with the first vertebra. Smaller foramina for the cranial nerves can be found at various points throughout the cranium. The jaws consist of separate hoops of cartilage, almost always distinct from the cranium proper.

In the ray-finned fishes, there has also been considerable modification from the primitive pattern. The roof of the skull is generally well formed, and although the exact relationship of its bones to those of tetrapods is unclear, they are usually given similar names for convenience. Other elements of the skull, however, may be reduced; there is little cheek region behind the enlarged orbits, and little if any bone in between them. The upper jaw is often formed largely from the premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammal has ...

, with the maxilla

The maxilla (plural: ''maxillae'' ) in vertebrates is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. T ...

itself located further back, and an additional bone, the sympletic, linking the jaw to the rest of the cranium.

Although the skulls of fossil lobe-finned fish resemble those of the early tetrapods, the same cannot be said of those of the living lungfishes. The skull roof is not fully formed, and consists of multiple, somewhat irregularly shaped bones with no direct relationship to those of tetrapods. The upper jaw is formed from the pterygoid bone

The pterygoid is a paired bone forming part of the palate of many vertebrates

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and ...

s and vomer

The vomer (; lat, vomer, lit=ploughshare) is one of the unpaired facial bones of the skull. It is located in the midsagittal line, and articulates with the sphenoid, the ethmoid, the left and right palatine bones, and the left and right max ...

s alone, all of which bear teeth. Much of the skull is formed from cartilage, and its overall structure is reduced.

The head may have several fleshy structures known as barbels, which may be very long and resemble whiskers. Many fish species also have a variety of protrusions or spines on the head. The nostrils or nares of almost all fishes do not connect to the oral cavity, but are pits of varying shape and depth.

northern pike

The northern pike (''Esox lucius'') is a species of carnivorous fish of the genus ''Esox'' (the pikes). They are typical of brackish water, brackish and fresh waters of the Northern Hemisphere (''i.e.'' holarctic in distribution). They are kno ...

File:Tiktaalik_skull_front.jpg, Skull of '' Tiktaalik'', a genus of extinct sarcopterygian

Sarcopterygii (; ) — sometimes considered synonymous with Crossopterygii () — is a taxon (traditionally a class or subclass) of the bony fishes known as the lobe-finned fishes. The group Tetrapoda, a mostly terrestrial superclass includ ...

(lobe-finned "fish") from the late Devonian period

External organs

Jaw

Silurian

The Silurian ( ) is a geologic period and system spanning 24.6 million years from the end of the Ordovician Period, at million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Devonian Period, Mya. The Silurian is the shortest period of the Paleoz ...

period and appeared in the Placoderm fish which further diversified in the Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the Silurian, million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Carboniferous, Mya. It is named after Devon, England, wh ...

. Jaws are thought to derive from the pharyngeal arches that support the gills in fish. The two most anterior of these arches are thought to have become the jaw itself (see hyomandibula

The hyomandibula, commonly referred to as hyomandibular one( la, os hyomandibulare, from el, hyoeides, "upsilon-shaped" (υ), and Latin: mandibula, "jawbone") is a set of bones that is found in the hyoid region in most fishes. It usually plays ...

) and the hyoid arch

The pharyngeal arches, also known as visceral arches'','' are structures seen in the embryonic development of vertebrates that are recognisable precursors for many structures. In fish, the arches are known as the branchial arches, or gill ar ...

, which braces the jaw against the braincase and increases mechanical efficiency. While there is no fossil evidence directly to support this theory, it makes sense in light of the numbers of pharyngeal arches that are visible in extant

Extant is the opposite of the word extinct. It may refer to:

* Extant hereditary titles

* Extant literature, surviving literature, such as ''Beowulf'', the oldest extant manuscript written in English

* Extant taxon, a taxon which is not extinct, ...

jawed animals (the gnathostomes), which have seven arches, and primitive jawless vertebrates (the Agnatha), which have nine.

It is thought that the original selective advantage garnered by the jaw was not related to feeding, but to increase respiration efficiency. The jaws were used in the

It is thought that the original selective advantage garnered by the jaw was not related to feeding, but to increase respiration efficiency. The jaws were used in the buccal pump

Buccal pumping is "breathing with one's cheeks": a method of ventilation used in respiration in which the animal moves the floor of its mouth in a rhythmic manner that is externally apparent.Brainerd, E. L. (1999). New perspectives on the evolutio ...

(observable in modern fish and amphibians) that pumps water across the gills of fish or air into the lungs of amphibians. Over evolutionary time, the more familiar use of jaws in feeding was selected for and became a very important function in vertebrates.

Linkage systems are widely distributed in animals. The most thorough overview of the different types of linkages in animals has been provided by M. Muller, who also designed a new classification system which is especially well suited for biological systems. Linkage mechanisms are especially frequent and various in the head of bony fishes, such as wrasses

The wrasses are a family, Labridae, of marine fish, many of which are brightly colored. The family is large and diverse, with over 600 species in 81 genera, which are divided into 9 subgroups or tribes.

They are typically small, most of them ...

, which have evolved many specialized aquatic feeding mechanisms. Especially advanced are the linkage mechanisms of jaw protrusion

Most bony fishes have two sets of jaws made mainly of bone. The primary oral jaws open and close the mouth, and a second set of pharyngeal jaws are positioned at the back of the throat. The oral jaws are used to capture and manipulate prey by b ...

. For suction feeding a system of connected four-bar linkages is responsible for the coordinated opening of the mouth and 3-D expansion of the buccal cavity. Other linkages are responsible for protrusion of the premaxilla.

Eyes

Fish eyes are similar to terrestrial vertebrates likebirds

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweigh ...

and mammals, but have a more spherical lens. Their retina

The retina (from la, rete "net") is the innermost, light-sensitive layer of tissue of the eye of most vertebrates and some molluscs. The optics of the eye create a focused two-dimensional image of the visual world on the retina, which the ...

s generally have both rod cell

Rod cells are photoreceptor cells in the retina of the eye that can function in lower light better than the other type of visual photoreceptor, cone cells. Rods are usually found concentrated at the outer edges of the retina and are used in pe ...

s and cone cell

Cone cells, or cones, are photoreceptor cells in the retinas of vertebrate eyes including the human eye. They respond differently to light of different wavelengths, and the combination of their responses is responsible for color vision. Cone ...

s (for scotopic and photopic vision), and most species have colour vision

Color vision, a feature of visual perception, is an ability to perceive differences between light composed of different wavelengths (i.e., different spectral power distributions) independently of light intensity. Color perception is a part of ...

. Some fish can see ultraviolet

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 PHz) to 400 nm (750 THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation ...

and some can see polarized light

Polarization ( also polarisation) is a property applying to transverse waves that specifies the geometrical orientation of the oscillations. In a transverse wave, the direction of the oscillation is perpendicular to the direction of motion of t ...

. Amongst jawless fish, the lamprey has well-developed eyes, while the hagfish has only primitive eyespots. The ancestors of modern hagfish, thought to be protovertebrate, were evidently pushed to very deep, dark waters, where they were less vulnerable to sighted predators and where it is advantageous to have a convex eyespot, which gathers more light than a flat or concave one. Unlike humans, fish normally adjust focus by moving the lens closer to or further from the retina.Helfman, Collette, Facey and Bowen, 2009, ''The Diversity of Fishes: Biology, Evolution, and Ecology ''pp. 84–87.

Gills

The gills, located under the operculum, are a respiratory organ for the extraction of oxygen from water and for the excretion of carbon dioxide. They are not usually visible, but can be seen in some species, such as the

The gills, located under the operculum, are a respiratory organ for the extraction of oxygen from water and for the excretion of carbon dioxide. They are not usually visible, but can be seen in some species, such as the frilled shark

The frilled shark (''Chlamydoselachus anguineus'') and the southern African frilled shark (''Chlamydoselachus africana'') are the two extant species of shark in the family ''Chlamydoselachidae''. The frilled shark is considered a living fossil, ...

. The labyrinth organ of Anabantoidei

The Anabantoidei are a suborder of anabantiform ray-finned freshwater fish distinguished by their possession of a lung-like labyrinth organ, which enables them to breathe air. The fish in the Anabantoidei suborder are known as anabantoids or la ...

and Clariidae is used to allow the fish to extract oxygen from the air. Gill rakers are finger-like projections off the gill arch which function in filter feeders to retain filtered prey. They may be bony or cartilaginous.

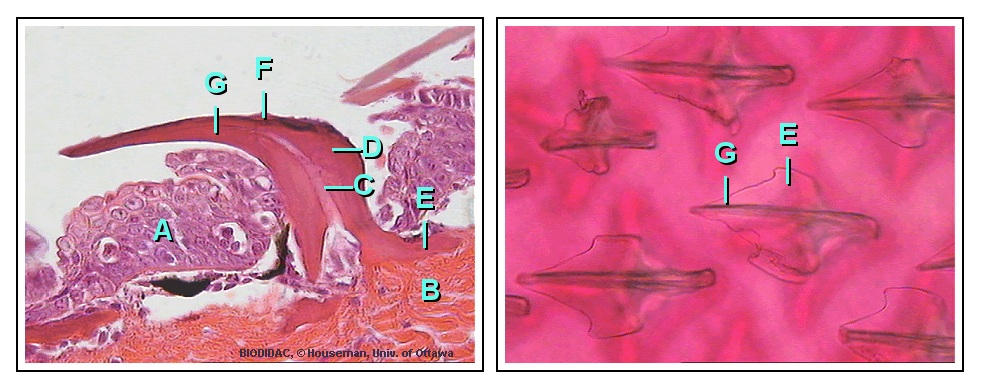

Skin

The skin of the fish are a part of theintegumentary system

The integumentary system is the set of organs forming the outermost layer of an animal's body. It comprises the skin and its appendages, which act as a physical barrier between the external environment and the internal environment that it serves ...

, which contains two layers: the epidermis and the dermis layer. The epidermis

The epidermis is the outermost of the three layers that comprise the skin, the inner layers being the dermis and hypodermis. The epidermis layer provides a barrier to infection from environmental pathogens and regulates the amount of water rel ...

is derived from the ectoderm

The ectoderm is one of the three primary germ layers formed in early embryonic development. It is the outermost layer, and is superficial to the mesoderm (the middle layer) and endoderm (the innermost layer). It emerges and originates from t ...

and becomes the most superficial layer that consists entirely of live cells, with only minimal quantities of keratin

Keratin () is one of a family of structural fibrous proteins also known as ''scleroproteins''. Alpha-keratin (α-keratin) is a type of keratin found in vertebrates. It is the key structural material making up Scale (anatomy), scales, hair, Nail ...

. It is generally permeable. The dermis

The dermis or corium is a layer of skin between the epidermis (with which it makes up the cutis) and subcutaneous tissues, that primarily consists of dense irregular connective tissue and cushions the body from stress and strain. It is divided ...

is derived from the mesoderm

The mesoderm is the middle layer of the three germ layers that develops during gastrulation in the very early development of the embryo of most animals. The outer layer is the ectoderm, and the inner layer is the endoderm.Langman's Medical Emb ...

and resembles the little connective tissue

Connective tissue is one of the four primary types of animal tissue, along with epithelial tissue, muscle tissue, and nervous tissue. It develops from the mesenchyme derived from the mesoderm the middle embryonic germ layer. Connective tiss ...

which are composed of mostly collagen fibers

Type I collagen is the most abundant collagen of the human body. It forms large, eosinophilic fibers known as collagen fibers.

It is present in scar tissue, the end product when tissue heals by repair, as well as tendons, ligaments, the endomy ...

found in bony fish. Some fish species have scales that emerge from the dermis, penetrate the thin layer of the basement membrane

The basement membrane is a thin, pliable sheet-like type of extracellular matrix that provides cell and tissue support and acts as a platform for complex signalling. The basement membrane sits between epithelial tissues including mesothelium an ...

that lies between the epidermis and dermis, and becomes externally visible and covers the epidermis layer.

Generally, the skin also contains sweat glands and sebaceous glands

A sebaceous gland is a microscopic exocrine gland in the skin that opens into a hair follicle to secrete an oily or waxy matter, called sebum, which lubricates the hair and skin of mammals. In humans, sebaceous glands occur in the greatest number ...

that are both unique to mammals, but additional types of skin glands are found in fish. Found in the epidermis, fish typically have numerous individual mucus

Mucus ( ) is a slippery aqueous secretion produced by, and covering, mucous membranes. It is typically produced from cells found in mucous glands, although it may also originate from mixed glands, which contain both serous and mucous cells. It ...

-secreting skin cells called goblet cells

Goblet cells are simple columnar epithelial cells that secrete gel-forming mucins, like mucin 5AC. The goblet cells mainly use the merocrine method of secretion, secreting vesicles into a duct, but may use apocrine methods, budding off their s ...

that produce a slimy substance to the surface of the skin. This aids in insulation and protection from bacterial infection. The skin colour of many mammals are often due to melanin

Melanin (; from el, μέλας, melas, black, dark) is a broad term for a group of natural pigments found in most organisms. Eumelanin is produced through a multistage chemical process known as melanogenesis, where the oxidation of the amino ...

found in their epidermis. In fish, however, the colour of the skin are largely due to chromatophores in the dermis, which, in addition to melanin, may contain guanine

Guanine () ( symbol G or Gua) is one of the four main nucleobases found in the nucleic acids DNA and RNA, the others being adenine, cytosine, and thymine ( uracil in RNA). In DNA, guanine is paired with cytosine. The guanine nucleoside is ...

or carotenoid

Carotenoids (), also called tetraterpenoids, are yellow, orange, and red organic pigments that are produced by plants and algae, as well as several bacteria, and fungi. Carotenoids give the characteristic color to pumpkins, carrots, parsnips, ...

pigments. Many species, such as flounders

Flounders are a group of flatfish species. They are demersal fish, found at the bottom of oceans around the world; some species will also enter estuaries.

Taxonomy

The name "flounder" is used for several only distantly related species, thoug ...

, change the colour of their skin by adjusting the relative size of their chromatophores. Some fishes may also have venom

Venom or zootoxin is a type of toxin produced by an animal that is actively delivered through a wound by means of a bite, sting, or similar action. The toxin is delivered through a specially evolved ''venom apparatus'', such as fangs or a st ...

glands, photophores

A photophore is a glandular organ that appears as luminous spots on various marine animals, including fish and cephalopods. The organ can be simple, or as complex as the human eye; equipped with lenses, shutters, color filters and reflectors, ...

, or cells that produce a more watery serous fluid in the dermis.

Scales

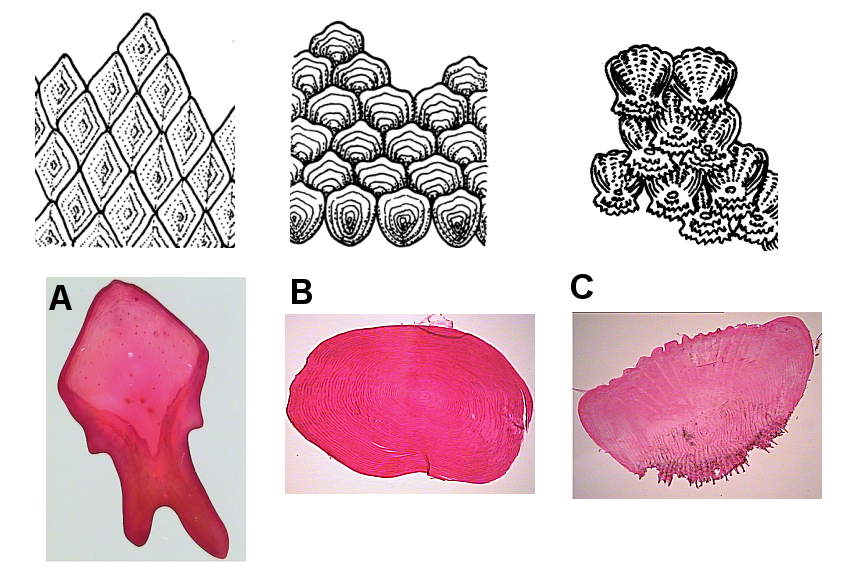

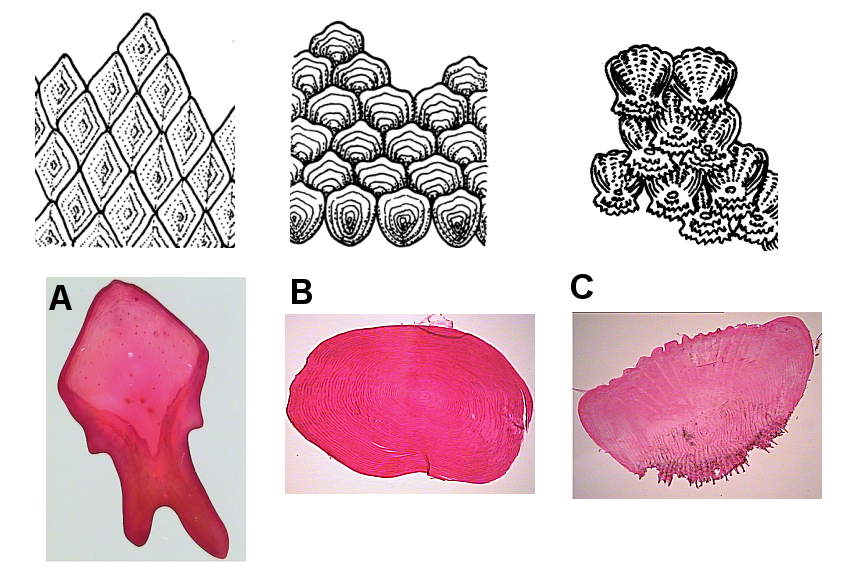

Also part of the fish's integumentary system are the scales that cover the outer body of many jawed fish. The commonly known scales are the ones that originate from the dermis or mesoderm, and may be similar in structure to teeth. Some species are covered by scutes instead. Others may have no scales covering the outer body.

There are four principal types of fish scales that originate from the dermis.

*

There are four principal types of fish scales that originate from the dermis.

* Placoid scales

A fish scale is a small rigid plate that grows out of the skin of a fish. The skin of most jawed fishes is covered with these protective scales, which can also provide effective camouflage through the use of reflection and colouration, as ...

, also called dermal denticles, are pointed scales. They are similar to the structure of teeth

A tooth ( : teeth) is a hard, calcified structure found in the jaws (or mouths) of many vertebrates and used to break down food. Some animals, particularly carnivores and omnivores, also use teeth to help with capturing or wounding prey, ...

, in which they are made of dentin

Dentin () (American English) or dentine ( or ) (British English) ( la, substantia eburnea) is a calcified tissue of the body and, along with enamel, cementum, and pulp, is one of the four major components of teeth. It is usually covered by e ...

and covered by enamel. They are typical of cartilaginous fish (even though chimaeras

Chimaeras are cartilaginous fish in the order Chimaeriformes , known informally as ghost sharks, rat fish, spookfish, or rabbit fish; the last three names are not to be confused with rattails, Opisthoproctidae, or Siganidae, respectively.

A ...

have it on claspers only).

* Ganoid scales are flat, basal-looking scales. Derived from placoid scales, they have a thick coat of enamel, but without the underlying layer of dentin. These scales cover the fish's body with little overlapping. They are typical of gar and bichirs.

* Cycloid scale

A fish scale is a small rigid plate that grows out of the skin of a fish. The skin of most jawed fishes is covered with these protective scales, which can also provide effective camouflage through the use of reflection and colouration, as ...

s are small, oval-shaped scales with growth rings

Dendrochronology (or tree-ring dating) is the scientific method of dating tree rings (also called growth rings) to the exact year they were formed. As well as dating them, this can give data for dendroclimatology, the study of climate and at ...

like the rings of a tree. They lack enamel, dentin, and a vascular bone layer. Bowfin

The bowfin (''Amia calva'') is a bony fish, native to North America. Common names include mudfish, mud pike, dogfish, grindle, grinnel, swamp trout, and choupique. It is regarded as a relict, being the sole surviving species of the Halecomorp ...

and remora have cycloid scales.

* Ctenoid scales are similar to cycloid scales, also having growth rings, lack enamel, dentin, and a vascular bone layer. They are distinguished by spines or projections along one edge. Halibut have this type of scale.

Another less common type of scale is the

Another less common type of scale is the scute

A scute or scutum (Latin: ''scutum''; plural: ''scuta'' "shield") is a bony external plate or scale overlaid with horn, as on the shell of a turtle, the skin of crocodilians, and the feet of birds. The term is also used to describe the anterior po ...

, which may be an external, shield-like bony plate; a modified, thickened scale that is often keeled or spiny; or a projecting, modified (rough and strongly ridged) scale. Scutes are usually associated with the lateral line

The lateral line, also called the lateral line organ (LLO), is a system of sensory organs found in fish, used to detect movement, vibration, and pressure gradients in the surrounding water. The sensory ability is achieved via modified epithelial ...

, but may be found on the caudal peduncle (where they form caudal keels) or along the ventral profile. Some fish, such as pineconefish, are completely or partially covered in scutes. Their function are intended for protection as a body armor for fish against environmental abrasions and predations from other species.

Lateral line

The lateral line is a sense organ used to detect movement and vibration in the surrounding water. For example, fish can use their lateral line system to follow the vortices produced by fleeing prey. In most species, it consists of a line of receptors running along each side of the fish.

The lateral line is a sense organ used to detect movement and vibration in the surrounding water. For example, fish can use their lateral line system to follow the vortices produced by fleeing prey. In most species, it consists of a line of receptors running along each side of the fish.

Photophores

Photophores are light-emitting organs which appear as luminous spots on some fishes. The light can be produced from compounds during the digestion of prey, from specializedmitochondrial

A mitochondrion (; ) is an organelle found in the cells of most Eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is used t ...

cells in the organism called photocytes

A photocyte is a cell that specializes in catalyzing enzymes to produce light (bioluminescence). Photocytes typically occur in select layers of epithelial tissue, functioning singly or in a group, or as part of a larger apparatus (a photophore). ...

, or from symbiotic bacteria Symbiotic bacteria are bacteria living in symbiosis with another organism or each other. For example, rhizobia living in root nodules of legumes provide nitrogen fixing activity for these plants. Symbiosis was first defined by Marko de Bary in 1869 ...

. Photophores are used for attracting food or confusing predators.

Fins

Spines and rays

In bony fish, most fins may have spines or rays. A fin may contain only spiny rays, only soft rays, or a combination of both. If both are present, the spiny rays are always anterior. Spines are generally stiff, sharp and unsegmented. Rays are generally soft, flexible, segmented, and may be branched. This segmentation of rays is the main difference that distinguishes them from spines; spines may be flexible in certain species, but never segmented. Spines have a variety of uses. Incatfish

Catfish (or catfishes; order Siluriformes or Nematognathi) are a diverse group of ray-finned fish. Named for their prominent barbels, which resemble a cat's whiskers, catfish range in size and behavior from the three largest species alive, ...

, they are used as a form of defense; many catfish have the ability to lock their spines outwards. Triggerfish

Triggerfish are about 40 species of often brightly colored fish of the family Balistidae. Often marked by lines and spots, they inhabit tropical and subtropical oceans throughout the world, with the greatest species richness in the Indo-Pacif ...

also use spines to lock themselves in crevices to prevent them being pulled out.

Lepidotrichia are bony, bilaterally-paired, segmented fin rays found in bony fishes. They develop around actinotrichia as part of the dermal exoskeleton. Lepidotrichia may have some cartilage or bone in them as well. They are actually segmented and appear as a series of disks stacked one on top of another. The genetic basis for the formation of the fin rays is thought to be genes coding for the proteins actinodin 1 and actinodin 2.

Types of fin

*Dorsal fin

A dorsal fin is a fin located on the back of most marine and freshwater vertebrates within various taxa of the animal kingdom. Many species of animals possessing dorsal fins are not particularly closely related to each other, though through c ...

s: Located on the back of the fish, dorsal fins serve to prevent the fish from rolling and assist in sudden turns and stops. Most fishes have one dorsal fin, but some fishes have two or three. In anglerfish

The anglerfish are fish of the teleost order Lophiiformes (). They are bony fish named for their characteristic mode of predation, in which a modified luminescent fin ray (the esca or illicium) acts as a lure for other fish. The luminescence ...

, the anterior of the dorsal fin is modified into an illicium

''Illicium'' is a genus of flowering plants treated as part of the family Schisandraceae,

and esca

The anglerfish are fish of the teleost order Lophiiformes (). They are bony fish named for their characteristic mode of predation, in which a modified luminescent fin ray (the esca or illicium) acts as a lure for other fish. The luminescence c ...

, a biological equivalent to a fishing rod

A fishing rod is a long, thin rod used by anglers to catch fish by manipulating a line ending in a hook (formerly known as an ''angle'', hence the term "angling"). At its most basic form, a fishing rod is a straight rigid stick/pole with ...

and lure. The two to three bones that support the dorsal fin are called the proximal, middle, and distal

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position pro ...

pterygiophore

A dorsal fin is a fin located on the back of most marine and freshwater vertebrates within various taxa of the animal kingdom. Many species of animals possessing dorsal fins are not particularly closely related to each other, though through con ...

s. In spinous fins, the distal pterygiophore is often fused to the middle or not present at all.

* Caudal/Tail fins: Also called the tail fins, caudal fins are attached to the end of the caudal peduncle and used for propulsion. The caudal peduncle is the narrow part of the fish's body. The hypural joint is the joint between the caudal fin and the last of the vertebrae. The hypural is often fan-shaped. The tail may be heterocercal

Fins are distinctive anatomical features composed of bony spines or rays protruding from the body of a fish. They are covered with skin and joined together either in a webbed fashion, as seen in most bony fish, or similar to a flipper, as ...

, reversed heterocercal, protocercal, diphycercal, or homocercal.

** Heterocercal: vertebrae extend into the upper lobe of the tail, making it longer (as in sharks)

** Reversed heterocercal: vertebrae extend into the lower lobe of the tail, making it longer (as in the Anaspida

Anaspida ("without shield") is an extinct group of primitive jawless vertebrates that lived primarily during the Silurian period, and became extinct soon after the start of the Devonian. They were classically regarded as the ancestors of lampre ...

)

** Protocercal: vertebrae extend to the tip of the tail; the tail is symmetrical but not expanded (as in cyclostomata

Cyclostomi, often referred to as Cyclostomata , is a group of vertebrates that comprises the living jawless fishes: the lampreys and hagfishes. Both groups have jawless mouths with horny epidermal structures that function as teeth called cer ...

ns, the ancestral vertebrates and lancelets

The lancelets ( or ), also known as amphioxi (singular: amphioxus ), consist of some 30 to 35 species of "fish-like" benthic filter feeding chordates in the order Amphioxiformes. They are the modern representatives of the subphylum Cephalochorda ...

).

** Diphycercal: vertebrae extend to the tip of the tail; the tail is symmetrical and expanded (as in the bichir, lungfish, lamprey and coelacanth). Most Palaeozoic

The Paleozoic (or Palaeozoic) Era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The name ''Paleozoic'' ( ;) was coined by the British geologist Adam Sedgwick in 1838

by combining the Greek words ''palaiós'' (, "old") and '' ...

fishes had a diphycercal heterocercal tail.

** Homocercal: vertebrae extend a very short distance into the upper lobe of the tail; tail still appears superficially symmetric. Most fish have a homocercal tail, but it can be expressed in a variety of shapes. The tail fin can be rounded at the end, truncated (almost vertical edge, as in salmon), forked (ending in two prongs), emarginate (with a slight inward curve), or continuous (dorsal, caudal, and anal fins attached, as in eels).

* Anal fin

Fins are distinctive anatomical features composed of bony spines or rays protruding from the body of a fish. They are covered with skin and joined together either in a webbed fashion, as seen in most bony fish, or similar to a flipper, as see ...

s: Located on the ventral surface behind the anus, this fin is used to stabilize the fish while swimming.

* Pectoral fin

Fins are distinctive anatomical features composed of bony spines or rays protruding from the body of a fish. They are covered with skin and joined together either in a webbed fashion, as seen in most bony fish, or similar to a flipper, as se ...

s: Found in pairs on each side, usually just behind the operculum. Pectoral fins are homologous to the forelimbs of tetrapods, and aid walking

Walking (also known as ambulation) is one of the main gaits of terrestrial locomotion among legged animals. Walking is typically slower than running and other gaits. Walking is defined by an ' inverted pendulum' gait in which the body vaults ...

in several fish species such as some anglerfish and the mudskipper

Mudskippers are any of the 23 extant species of amphibious fish from the subfamily Oxudercinae of the goby family Oxudercidae. They are known for their unusual body shapes, preferences for semiaquatic habitats, limited terrestrial locomotion ...

. A peculiar function of pectoral fins, highly developed in some fish, is the creation of the dynamic lifting force that assists some fish such as sharks in maintaining depth and also enables the "flight" for flying fish. Certain rays of the pectoral fins may be adapted into finger-like projections, such as in sea robins and flying gurnard

The flying gurnard (''Dactylopterus volitans''), also known as the helmet gurnard, is a bottom-dwelling fish of tropical to warm temperate waters on both sides of the Atlantic. On the American side, it is found as far north as Massachusetts (ex ...

s.

** "Cephalic fins": The "horns" of manta ray

Manta rays are large rays belonging to the genus ''Mobula'' (formerly its own genus ''Manta''). The larger species, '' M. birostris'', reaches in width, while the smaller, '' M. alfredi'', reaches . Both have triangular pectoral fins, horn-s ...

s and their relatives, sometimes called cephalic fins, are actually a modification of the anterior portion of the pectoral fin.

* Pelvic/ Ventral fins: Found in pairs on each side ventrally below the pectoral fins, pelvic fins are homologous to the hindlimbs of tetrapods. They assist the fish in going up or down through the water, turning sharply, and stopping quickly. In gobies, the pelvic fins are often fused into a single sucker disk that can be used to attach to objects.

* Adipose fin: A soft, fleshy fin found on the back behind the dorsal fin and just in front of the caudal fin. It is absent in many fish families, but is found in Salmonidae, characin

Characiformes is an order of ray-finned fish, comprising the characins and their allies. Grouped in 18 recognized families, more than 2000 different species are described, including the well-known piranha and tetras.; Buckup P.A.: "Relationsh ...

s and catfishes. Its function has remained a mystery, and is frequently clipped off to mark hatchery-raised fish, though data from 2005 showed that trout with their adipose fin removed have an 8% higher tailbeat frequency. Additional research published in 2011 has suggested that the fin may be vital for the detection of and response to stimuli such as touch, sound and changes in pressure. Canadian researchers identified a neural network in the fin, indicating that it likely has a sensory function, but are still not sure exactly what the consequences of removing it are.

* Caudal keel: A lateral ridge, usually composed of scutes, on the caudal peduncle just in front of the tail fin. Found on some types of fast-swimming fish, it provides stability and support to the caudal fin, much like the keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in Br ...

of a ship. There may be a single paired keel, one on each side, or two pairs above and below.

* Finlet

Fins are distinctive anatomical features composed of bony spines or rays protruding from the body of a fish. They are covered with skin and joined together either in a webbed fashion, as seen in most bony fish, or similar to a flipper, as se ...

s: Small fins generally between the dorsal and the caudal fins, but may also be between the anal fin and the caudal fin. In bichirs, there are only finlets on the dorsal surface and no dorsal fin. In some fish such as tuna

A tuna is a saltwater fish that belongs to the tribe Thunnini, a subgrouping of the Scombridae (mackerel) family. The Thunnini comprise 15 species across five genera, the sizes of which vary greatly, ranging from the bullet tuna (max length: ...

or sauries, they are rayless, non-retractable, and found between the last dorsal or anal fin and the caudal fin.

Internal organs

Intestines

As with other vertebrates, theintestine

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans an ...

s of fish consist of two segments, the small intestine

The small intestine or small bowel is an organ (anatomy), organ in the human gastrointestinal tract, gastrointestinal tract where most of the #Absorption, absorption of nutrients from food takes place. It lies between the stomach and large intes ...

and the large intestine

The large intestine, also known as the large bowel, is the last part of the gastrointestinal tract and of the digestive system in tetrapods. Water is absorbed here and the remaining waste material is stored in the rectum as feces before bein ...

. In most higher vertebrates, the small intestine is further divided into the duodenum

The duodenum is the first section of the small intestine in most higher vertebrates, including mammals, reptiles, and birds. In fish, the divisions of the small intestine are not as clear, and the terms anterior intestine or proximal intestine m ...

and other parts. In fish, the divisions of the small intestine are not as clear, and the terms ''anterior intestine'' or ''proximal intestine'' may be used instead of duodenum.

In bony fish, the intestine is relatively short, typically around one and a half times the length of the fish's body. It commonly has a number of pyloric caeca, small pouch-like structures along its length that help to increase the overall surface area of the organ for digesting food. There is no ileocaecal valve in teleosts, with the boundary between the small intestine and the rectum

The rectum is the final straight portion of the large intestine in humans and some other mammals, and the gut in others. The adult human rectum is about long, and begins at the rectosigmoid junction (the end of the sigmoid colon) at the l ...

being marked only by the end of the digestive epithelium

Epithelium or epithelial tissue is one of the four basic types of animal tissue, along with connective tissue, muscle tissue and nervous tissue. It is a thin, continuous, protective layer of compactly packed cells with a little intercellul ...

. There is no small intestine as such in non-teleost fish, such as sharks, sturgeons, and lungfish. Instead, the digestive part of the gut forms a ''spiral intestine'', connecting the stomach

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the gastrointestinal tract of humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates. The stomach has a dilated structure and functions as a vital organ in the digestive system. The stomach i ...

to the rectum. In this type of gut, the intestine itself is relatively straight, but has a long fold running along the inner surface in a spiral fashion, sometimes for dozens of turns. This fold creates a valve-like structure that greatly increases both the surface area and the effective length of the intestine. The lining of the spiral intestine is similar to that of the small intestine in teleosts and non-mammalian tetrapods. In lampreys, the spiral valve is extremely small, possibly because their diet requires little digestion. Hagfish have no spiral valve at all, with digestion occurring for almost the entire length of the intestine, which is not subdivided into different regions.

Pyloric caeca

The pyloriccaecum

The cecum or caecum is a pouch within the peritoneum that is considered to be the beginning of the large intestine. It is typically located on the right side of the body (the same side of the body as the appendix, to which it is joined). The wo ...

is a pouch, usually peritoneal

The peritoneum is the serous membrane forming the lining of the abdominal cavity or coelom in amniotes and some invertebrates, such as annelids. It covers most of the intra-abdominal (or coelomic) organs, and is composed of a layer of mes ...

, at the beginning of the large intestine. It receives faecal material from the ileum, and connects to the ascending colon

''Ascending'' is a science fiction novel by the Canadian writer James Alan Gardner, published in 2001 by HarperCollins Publishers under its various imprints.HarperCollins, Avon, HarperCollins Canada, SFBC/Avon; paperback edition 2001, Eos Books. ...

of the large intestine. It is present in most amniote

Amniotes are a clade of tetrapod vertebrates that comprises sauropsids (including all reptiles and birds, and extinct parareptiles and non-avian dinosaurs) and synapsids (including pelycosaurs and therapsids such as mammals). They are dis ...

s, and also in lungfish. Many fish in addition have a number of small outpocketings, also called pyloric caeca, along their intestine; despite the name they are not homologous to the caecum of amniotes. Their purpose is to increase the overall surface area of the digestive epithelium, therefore optimizing the absorption of sugars, amino acids

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

, and dipeptides A dipeptide is an organic compound derived from two amino acids. The constituent amino acids can be the same or different. When different, two isomers of the dipeptide are possible, depending on the sequence. Several dipeptides are physiologicall ...

, among other nutrients.

Stomach

As with other vertebrates, the relative positions of the esophageal and duodenal openings to the stomach remain relatively constant. As a result, the stomach always curves somewhat to the left before curving back to meet the pyloric sphincter. However, lampreys, hagfishes,chimaera

Chimaeras are cartilaginous fish in the order Chimaeriformes , known informally as ghost sharks, rat fish, spookfish, or rabbit fish; the last three names are not to be confused with rattails, Opisthoproctidae, or Siganidae, respectively.

At ...

s, lungfishes, and some teleost fish have no stomach at all, with the esophagus

The esophagus (American English) or oesophagus (British English; both ), non-technically known also as the food pipe or gullet, is an organ in vertebrates through which food passes, aided by peristaltic contractions, from the pharynx to t ...

opening directly into the intestine. These fish consume diets that either require little storage of food, no pre-digestion with gastric juices, or both.

Kidneys

Thekidney

The kidneys are two reddish-brown bean-shaped organs found in vertebrates. They are located on the left and right in the retroperitoneal space, and in adult humans are about in length. They receive blood from the paired renal arteries; blo ...

s of fish are typically narrow, elongated organs, occupying a significant portion of the trunk. They are similar to the mesonephros of higher vertebrates (reptiles, birds, and mammals). The kidneys contain clusters of nephrons, serviced by collecting ducts which usually drain into a mesonephric duct. However, the situation is not always so simple. In cartilaginous fish, there is also a shorter duct which drains the posterior (metanephric) parts of the kidney, and joins with the mesonephric duct at the bladder

The urinary bladder, or simply bladder, is a hollow organ in humans and other vertebrates that stores urine from the kidneys before disposal by urination. In humans the bladder is a distensible organ that sits on the pelvic floor. Urine en ...

or cloaca. Indeed, in many cartilaginous fish, the anterior portion of the kidney may degenerate or cease to function altogether in the adult. Hagfish and lamprey kidneys are unusually simple. They consist of a row of nephrons, each emptying directly into the mesonephric duct.

Like the Nile tilapia, the kidney of some fish shows its three parts; head, trunk, and tail kidneys.

Fish do not have a discrete adrenal gland with distinct cortex and medulla, similar to those found in mammals. The interrenal and chromaffin cells are located within the head kidney.

Spleen

Thespleen

The spleen is an organ found in almost all vertebrates. Similar in structure to a large lymph node, it acts primarily as a blood filter. The word spleen comes .

is found in nearly all vertebrates. It is a non-vital organ, similar in structure to a large lymph node

A lymph node, or lymph gland, is a kidney-shaped organ of the lymphatic system and the adaptive immune system. A large number of lymph nodes are linked throughout the body by the lymphatic vessels. They are major sites of lymphocytes that includ ...

. It acts primarily as a blood filter, and plays important roles in regards to red blood cells and the immune system

The immune system is a network of biological processes that protects an organism from diseases. It detects and responds to a wide variety of pathogens, from viruses to parasitic worms, as well as cancer cells and objects such as wood splinte ...

.Spleen, Internet Encyclopedia of Science In cartilaginous and bony fish it consists primarily of red pulp and is normally a somewhat elongated organ as it actually lies inside the serosal lining of the intestine. The only vertebrates lacking a spleen are the lampreys and hagfishes. Even in these animals, there is a diffuse layer of haematopoietic tissue within the gut wall, which has a similar structure to

red pulp

The red pulp of the spleen is composed of connective tissue known also as the cords of Billroth and many splenic sinusoids that are engorged with blood, giving it a red color. Its primary function is to filter the blood of antigens, microorgan ...

, and is presumed to be homologous to the spleen of higher vertebrates.

Liver

The liver is a largevital organ