First Messenian War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The First Messenian War was a war between

Pausanias' description of the battle creates an apparent historical paradox. He refers to "the special characters of the two forces in their behaviors and in their frame of mind.". The Messenians "ran charging at the Lakonians reckless of their lives ....". "Some of them leapt forward out of rank and did glorious deeds of courage.". The Spartans on the other hand were "careful not to break rank." Says Pausanias, "... knowledge of war was something they had been brought up to, they kept a deeper formation, expecting the Messenians not to hold a line against them for as long as their own would hold ...."

The Spartan tactic being described is that of the

Pausanias' description of the battle creates an apparent historical paradox. He refers to "the special characters of the two forces in their behaviors and in their frame of mind.". The Messenians "ran charging at the Lakonians reckless of their lives ....". "Some of them leapt forward out of rank and did glorious deeds of courage.". The Spartans on the other hand were "careful not to break rank." Says Pausanias, "... knowledge of war was something they had been brought up to, they kept a deeper formation, expecting the Messenians not to hold a line against them for as long as their own would hold ...."

The Spartan tactic being described is that of the

Not wanting to experience another such battle, the Messenians fell back to the heavily fortified Mount Ithome. This is when the Messenians first sent for help from the

Not wanting to experience another such battle, the Messenians fell back to the heavily fortified Mount Ithome. This is when the Messenians first sent for help from the

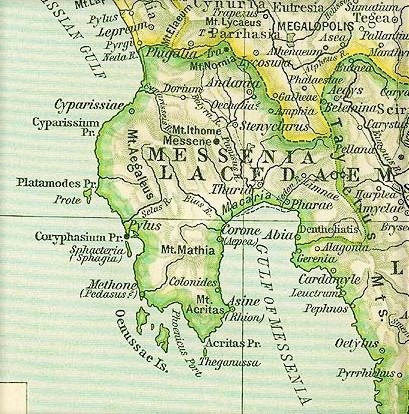

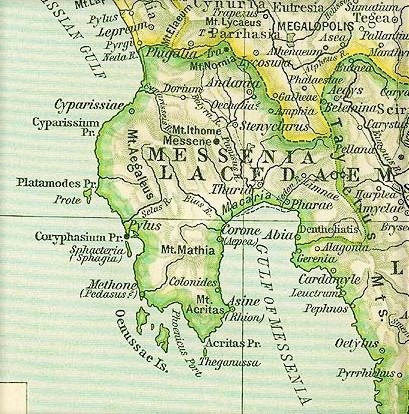

Messenia

Messenia or Messinia ( ; el, Μεσσηνία ) is a regional unit (''perifereiaki enotita'') in the southwestern part of the Peloponnese region, in Greece. Until the implementation of the Kallikratis plan on 1 January 2011, Messenia was a ...

and Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referr ...

. It began in 743 BC and ended in 724 BC, according to the dates given by Pausanias Pausanias ( el, Παυσανίας) may refer to:

*Pausanias of Athens, lover of the poet Agathon and a character in Plato's ''Symposium''

*Pausanias the Regent, Spartan general and regent of the 5th century BC

* Pausanias of Sicily, physician of t ...

.

The war continued the rivalry between the Achaeans and the Dorians

The Dorians (; el, Δωριεῖς, ''Dōrieîs'', singular , ''Dōrieús'') were one of the four major ethnic groups into which the Hellenes (or Greeks) of Classical Greece divided themselves (along with the Aeolians, Achaeans, and Ioni ...

that had been initiated by the purported Return of the Heracleidae. Both sides utilized an explosive incident to settle the rivalry by full-scale war. The war was prolonged into 20 years. The result was a Spartan victory. Messenia was depopulated by emigration of the Achaeans to other states. Those who did not emigrate were reduced socially to helot

The helots (; el, εἵλωτες, ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their ...

s, or serfs. Their descendants were held in hereditary servitude for centuries until the Spartan state finally needed them for defense.

Dates

Pausanias' standard dates

Pausanias Pausanias ( el, Παυσανίας) may refer to:

*Pausanias of Athens, lover of the poet Agathon and a character in Plato's ''Symposium''

*Pausanias the Regent, Spartan general and regent of the 5th century BC

* Pausanias of Sicily, physician of t ...

says that the opening campaign was a surprise attack on Ampheia Ampheia ( grc, Ἄμφεια) was a town of ancient Messenia, situated on the frontiers of Laconia, upon a hill well supplied with water. It was surprised and taken by the Spartans at the beginning of the First Messenian War

The First Messenian ...

by a Spartan force commanded by Alcmenes, Agiad

The Agiad dynasty was one of the two royal families of Sparta, a powerful city-state of Ancient Greece. The Agiads were seniors to the other royal house, the Eurypontids, with whom they had an enduring rivalry. Their hypothetical founder was Agis I ...

king of Sparta, in the second year of the 9th Olympiad

An olympiad ( el, Ὀλυμπιάς, ''Olympiás'') is a period of four years, particularly those associated with the ancient and modern Olympic Games.

Although the ancient Olympics were established during Greece's Archaic Era, it was not unti ...

. The end of the war was the abandonment of Mt. Ithome in the first year of the 14th Olympiad. The time of the war is so clearly fixed at 743/742 BC through 724/722 BC that other events in Greek history are often dated by it. Pausanias evidently had access to a chronology of events by Olympiad. The details of the war are not so certain but Pausanias gives an evaluation of his two main sources, the epic poem by Rianos of Bene for the first half and the prose history of Myron of Priene for the second half. Nothing survives now of the sources except fragments.

Dates by the archaeology of Taras and Asine

A second method of dating presented by John Coldstream takes archaeology into consideration as well as other literary evidence, arriving at somewhat later dates. Argos had entered the war on the Messenian side toward the end of it. They decided to eliminateAsine

Asine (; grc, Ἀσίνη) was an ancient Greek city of ancient Argolis, located on the coast. It is mentioned by Homer in the Catalogue of Ships in the ''Iliad'' as one of the places subject to Diomedes, king of Argos. It is said to have bee ...

in reprisal for its assistance to Sparta during the Spartan invasion of Argos. After the war Sparta placed the refugees in a new settlement called Asine on the Messenian Gulf, today's Koroni

Koroni or Corone ( el, Κορώνη) is a town and a former municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Pylos-Nestoras, of which it is a municipal unit. Known as ''Corone'' ...

. The destruction level at the old Asine is dated 710 BC, more precise actually than can be obtained for most archaeological dates.

A second piece of apparently archaeologically supported evidence is the settlement of the Partheniai at Taras (Tarentum Tarentum may refer to:

* Taranto, Apulia, Italy, on the site of the ancient Roman city of Tarentum (formerly the Greek colony of Taras)

**See also History of Taranto

* Tarentum (Campus Martius), also Terentum, an area in or on the edge of the Camp ...

) in Italy. During the war while the men were away a certain number of Spartan ladies bore illegitimate children to non-Spartiate fathers, some with husbands stationed in Messenia. These Partheniai were denied citizenship and, being unwelcome in Sparta, they became a civic problem, ultimately staging a rebellion. They were sent off under Phalanthus at the suggestion of the Delphic oracle to found Taras at Satyrion later a suburb of Tarentum. Pottery from there is exclusively Greek and geometric from about 700 BC. Eusebius says Taras was founded in 706 BC. Granting a precision to the 710 date he does not grant to the 700 date and presuming the juveniles were sent away immediately after the war, Coldstream formulates new dates for the war of 730–710 BC.

Background

Early rejection of the Heraclid king

ThePeloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridge which ...

had been Achaean before the return of the Heracleidae in 1104 BC. The victorious Dorian commanders, who were Heraclids, divided the Peloponnese between them. Temenus

In Greek mythology, Temenus ( el, Τήμενος, ''Tḗmenos'') was a son of Aristomachus and brother of Cresphontes and Aristodemus.

Temenus was a great-great-grandson of Heracles and helped lead the fifth and final attack on Mycenae in the ...

took Argos, Cresphontes

In Greek mythology, Cresphontes (; grc, Κρεσφόντης) was a son of Aristomachus, husband of Merope, father of Aepytus and brother of Temenus and Aristodemus. He was a great-great-grandson of Heracles and helped lead the fifth and fin ...

took Messenia

Messenia or Messinia ( ; el, Μεσσηνία ) is a regional unit (''perifereiaki enotita'') in the southwestern part of the Peloponnese region, in Greece. Until the implementation of the Kallikratis plan on 1 January 2011, Messenia was a ...

and the twin sons of Aristodemus

In Greek mythology, Aristodemus (Ancient Greek: Ἀριστόδημος) was one of the Heracleidae, son of Aristomachus and brother of Cresphontes and Temenus. He was a great-great-grandson of Heracles and helped lead the fifth and final attac ...

took Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referr ...

. The previous ruling family of Messenia, the Neleides Neleides or Nelides ( (Nηλείδης); also Neleiades (Νηληιάδης), Neleius, and in the plural Neleidae; grc-gre, Νηλεῖδαι) was a patronymic of ancient Greece derived from Neleus, son of the Greek god Poseidon, and was used to r ...

, had emigrated with the Atreids, rulers of Mycenae

Mycenae ( ; grc, Μυκῆναι or , ''Mykē̂nai'' or ''Mykḗnē'') is an archaeological site near Mykines in Argolis, north-eastern Peloponnese, Greece. It is located about south-west of Athens; north of Argos; and south of Corinth. ...

and Argos, to Athens. Most of the Achaeans remained in place.

The Dorians colonized Sparta, then a small state on the east of the central Eurotas

In Greek mythology, Eurotas (; Ancient Greek: Εὐρώτας) was a king of Laconia. Family

Eurotas was the son of King Myles of Laconia and grandson of Lelex, eponymous ancestor of the Leleges. The '' Bibliotheca'' gave a slight variant of ...

valley. Theras, their mother's brother, acted as regent for his nephews until they reached majority and then led a colony to Thera

Santorini ( el, Σαντορίνη, ), officially Thira (Greek: Θήρα ) and classical Greek Thera (English pronunciation ), is an island in the southern Aegean Sea, about 200 km (120 mi) southeast from the Greek mainland. It is the ...

. Meanwhile, the Messenians had accepted Cresphontes as king after he married Merope, daughter of Cypselus, king of Arcadia and an Achaean. They gave up some land to another Dorian enclave in Messenia. Subsequently the noble families of the Achaeans staged an insurrection, assassinating Cresphontes and all but one of his sons in a single coup. The youngest, Aepytus, was being educated in Arcadia.

Acceptance of the Aepytidae

Aepytus on reaching manhood shortly was restored by the kings of Sparta (Dorian), Argos (Dorian) and Arcadia (Achaean). The Messenian aristocracy was won by gifts and kindness, except for the regicides, who were executed. Aepytus founded a dynasty of kings of Messenia, the Aepytidae. The Heraclid part of the family background was explicitly dropped. The Aepytidae integrated totally into Achaean culture. They took the ancient Achaean (and Pelasgian) shrine on the summit of Mt.Ithome

Mount Ithome (Greek: Ἰθώμη) or Ithomi, previously Vourkano(s) ( el, Βουρκάνο(ς)) or Voulcano(s) ( el, Βουλκάνο(ς)), is the northernmost of twin peaks in Messenia, Greece. Mount Ithome rises to about , about over Valyra, ...

as their own, compelling the Dorians to worship there also. Ultimately under King Phintas they joined the yearly festival to Apollo at Delos

The island of Delos (; el, Δήλος ; Attic: , Doric: ), near Mykonos, near the centre of the Cyclades archipelago, is one of the most important mythological, historical, and archaeological sites in Greece. The excavations in the island ar ...

, the very central festival and most important place of worship of the Ionians

The Ionians (; el, Ἴωνες, ''Íōnes'', singular , ''Íōn'') were one of the four major tribes that the Greeks considered themselves to be divided into during the ancient period; the other three being the Dorians, Aeolians, and Achaea ...

, the descendants of the Achaeans.

This Achaeanizing provoked the Dorians living in Messenia. They viewed themselves as dominant over the Achaeans by right of conquest. They were supported in this view by Sparta, which had maintained a successful Dorian enclave, eventually achieving ascendance over the Achaeans in the Eurotas valley, who became the perioeci

The Perioeci or Perioikoi (, ) were the second-tier citizens of the '' polis'' of Sparta until 200 BC. They lived in several dozen cities within Spartan territories (mostly Laconia and Messenia), which were dependent on Sparta. The ''perioeci' ...

.

The raid on the temple of Artemis Limnatis

The intense ethnic animosity and contention that prevailed between the Dorians and the Achaeans is illustrated by an incident of violence that occurred 25 years prior to the First Messenian War, during a festival at thetemple

A temple (from the Latin ) is a building reserved for spiritual rituals and activities such as prayer and sacrifice. Religions which erect temples include Christianity (whose temples are typically called churches), Hinduism (whose temples ...

of Artemis Limnatis around 768 BC. This was the year that king Phintas, considered Dorian by the Dorians, brought Messenia to an Ionian festival. The temple was on the border between Messenia and Laconia and only Messenians and Laconians worshipped there. Artemis

In ancient Greek mythology and religion, Artemis (; grc-gre, Ἄρτεμις) is the goddess of the hunt, the wilderness, wild animals, nature, vegetation, childbirth, care of children, and chastity. She was heavily identified with ...

, sister of Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label=Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label= ...

, had long been a popular goddess among the Mycenaean Greeks.

Pausanias relates two versions of the story. The Spartan version tells of the raping of virgins and the killing of the king of the Agiad

The Agiad dynasty was one of the two royal families of Sparta, a powerful city-state of Ancient Greece. The Agiads were seniors to the other royal house, the Eurypontids, with whom they had an enduring rivalry. Their hypothetical founder was Agis I ...

line in Sparta, Teleklos. Ordinarily festivals and temples were sacred and were conducted on sacred ground in Greece; even hunted men could take refuge in a temple because of the taboo against violence. The Spartan version does not explain why the Messenians came to worship and suddenly began committing rape and murder on sacred ground.

The Messenian story says that the "virgins" were beardless soldiers dressed up as women under the leadership of Teleklos, and that the soldiers intended to get close to the Messenian aristocracy for an attempt at their lives. The usual religious considerations may not have been considered to apply since the shrine was an Achaean center, not a Dorian one. The soldiers selected for their beardlessness turned out to be too inexperienced, though, and the Messenian leaders easily threw them off and assassinated their commander. Pausanias says: "Those are the stories: believe one or the other according to which side you want to be on."

Cause

Immediate provocation

A generation later "the mutual hatred of the Lakonians and Messenians came to a head." The immediate provocation was an incident of cattle theft.Polychares of Messenia Polychares of Messenia ( grc, Πολυχάρης) was an athlete from Messenia who won the stadion race in the fourth Ancient Olympic Games in 764 BC.Eusebius. Chronicon' (English translation from Latin, original Greek lost) at Attalus.org The st ...

, an athlete and Olympic victor, leased some grazing land from Euaiphnos the Spartan, who promptly sold the cattle to some merchants, claiming pirates had stolen them. As he was making excuses to Polychares a herdsman of the latter, having escaped from the merchants, intervened to acquaint his master with the real facts. Apologizing Euaiphnos asked Polychares to let his son go with him to obtain the money from the sale, but once over the Spartan border he murdered the son. Polychares petitioned the Spartan magistrates for justice. Despairing of it he began to murder such Spartans as he could catch at random. The Spartans demanded extradition of Polychares. The Messenian magistrates insisted on an exchange for Euaiphnos.

At this point the incident exploded into violence at the national level. The Spartans sent a delegation to petition the kings of Messenia, nominally Heraclids. Androcles was for extradition, Antiochus against. The whole history of Spartan-Messenian relations was reviewed, including the assassination of Teleclus 25 years earlier and the discussion became so heated that weapons were drawn. The parties of the two kings assaulted each other and Androcles was killed. Antiochus told the Spartans he would submit the case to the courts at Argos (Dorian) and Athens (Achaean). Antiochus died a few months later and his son, Euphaes, succeeded him. The law case seems to have vanished. Shortly after a Spartan army under both kings of Sparta launched an invasion of Messenia.

Possible underlying causes

Pausanias states the details of the immediate provocation for war and expresses his view that the underlying cause was ethnic and regional tension between Laconia and Messenia. Various scholars have given speculative analyses of the underlying causes throughout the centuries since Pausanias. A recent historian, William Dunstan, guesses that the Spartan invasion, except for the Spartan colony ofTarentum Tarentum may refer to:

* Taranto, Apulia, Italy, on the site of the ancient Roman city of Tarentum (formerly the Greek colony of Taras)

**See also History of Taranto

* Tarentum (Campus Martius), also Terentum, an area in or on the edge of the Camp ...

, as an alternative to the colonization undertaken by most of the other states of Greece to relieve overpopulation at home. No evidence is offered for that view. He also implies that the Spartan aristocracy were moved by the desire for wealth, based on a cultural floruit and some foreign goods dating to the Orientalizing Period found during the excavation of the temple of Artemis Orthia in Sparta. No such motives appear in the classical sources. As Dunstan points out, after about 600 BC Spartan luxuries were in deficit. The Spartan economy improved significantly with the inflow of dues from the new helot

The helots (; el, εἵλωτες, ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their ...

class of Messenia. There is no evidence that this economic arrangement was intended beforehand as a cause of the war.

The strongest case for an underlying, in this case ulterior, the Spartan motive for the war is an admission by one of the Spartan kings that the Spartans needed Messenian land. The Spartan Constitution

The Spartan Constitution (or Spartan politeia) are the government and laws of the classical Greek city-state of Sparta. All classical Greek city-states had a politeia; the politeia of Sparta however, was noted by many classical authors for its ...

was already in effect by the time the war broke out. The Spartans had already produced a professional army, which is evidenced not only by their tactics in the war but by the reluctance of the Messenians to engage them. Lycurgus

Lycurgus or Lykourgos () may refer to:

People

* Lycurgus (king of Sparta) (third century BC)

* Lycurgus (lawgiver) (eighth century BC), creator of constitution of Sparta

* Lycurgus of Athens (fourth century BC), one of the 'ten notable orators' ...

had redistributed all the land in Lacedaemon, creating 39,000 equal plots, of which 9000 went to the Spartiates and 30,000 to the Perioeci. The source of this information, Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

, states two opinions as to the location of the 9000: either 6000 originally in Lacedaemon with 3000 in Messenia, added by the king Polydorus

In Greek mythology, Polydorus (; grc, Πολύδωρος, i.e. "many-gift d) or Polydoros referred to several different people.

*Polydorus, son of Phineus and Cleopatra, and brother of Polydector (Polydectus). These two sons by his first wife were ...

, victor of the First Messenian War, or 4500 in each region. Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

later stated that the Spartans could support 3000 infantry and 1500 cavalry. Each Spartiatate by law had to have his own ''kleros'', an inalienable plot of land. Burckhardt notes that Polydorus, questioned whether he wanted to go to war against brothers (presumably, Dorians integrated into Messenian society) replied: "All we want is land not yet distributed; that is, not yet divided by lot for our people."

Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His '' History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of " scienti ...

states that Sparta controlled 2/5 of the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridge which ...

, which according to Nigel Kennel is . Using this figure as a rough estimate of the amount of land occupied by 39,000 klaroi obtains a figure of per klaros, a significant agricultural estate. As citizenship and other social status depended on the possession of one the availability of land must have been a strong motive.

Course

The capture of Ampheia for use as a Spartan base

Despairing finally of remedies at law for the murders of their citizens the Spartans resolved to go to war without the usual heraldic notification or any other warning to the Messenians. Alcmenes assembled an army. When it was ready they swore an oath not to stop fighting until they had taken Messenia no matter whether the war was long or short and regardless of the casualties and cost. The war's first battle was the Spartan attack on Ampheia, a city of unknown location now, but probably on the western flank of Taygetus. A swift night march brought them to the gates, which stood open. There was no garrison, nor were they in any way expected. The first sign the Ampheians had of war was the Spartans rousing people out of bed to kill them. Some few took refuge in the temples; others fled for their lives. The Spartans sacked the city then turned it into a garrison for the conduct of further operations against Messenia. The Messenian women and children were captured. The men who had survived the massacre were sold into slavery. When the news of Ampheia spread a crowd gathered at the capital, Stenykleros ("rough acres," location unknown, perhaps underMessene

Messene (Greek: Μεσσήνη 𐀕𐀼𐀙 ''Messini''), officially Ancient Messene, is a local community within the regional unit (''perifereiaki enotita'') of Messenia in the region (''perifereia'') of Peloponnese.

It is best known for the ...

), from all of Messenia. They were addressed by the king, Euphaes. He encouraged them to be true men in the hour of need, assuring them that justice and the gods were on their side because they had not attacked first. Subsequently he placed the entire citizenry under arms and arranged for their training.

From the beginning Euphaes relied on fixed defenses. He fortified and garrisoned the towns but avoided forays against the Spartan army. For two seasons more the Spartans raided the moveable wealth, especially confiscating grain and money, but were ordered to spare capital equipment such as buildings and trees, which might be of use after the war. In this matrix of fortified points the Spartans could never successfully siege any one point. Declining to attack the main Spartan army, the Messenians could only assault undefended Spartan border communities when the opportunity arose.

The skirmish for the fortified camp on the ravine

In the fourth campaigning season; that is, in the summer of 739 according to Pausanias' dating scheme, Euphaes resolved to bring the war to the Spartans at Ampheia ("let loose the full blast of Messenian anger"). The Spartans were denying the Messenians use of the countryside for agriculture. Subsequent events show that this denial was untenable in the long term for the Messenians. They needed to strike a blow to remove the Spartan presence from their country. Euphaes judged that his army was sufficiently trained to oppose the Spartan professional soldiers. He readied an expedition and subsequently marched out of the capital in what must have been the direction of Ampheia. That his first concern was to construct a fortified base nearer to Ampheia is indicated by the transport of "timber and all the materials for stockades" in his baggage train. No mention is made of any intelligence on the current position of the Spartan army. His actions were not those of a general expecting a battle that day. His intent must have been to move the start line of future attacks closer to the enemy, a standard tactic later used by the Roman army with repeated success. The Spartans on the other hand were tracking his every movement. They sent immediately for reinforcements from Sparta, who marched directly for the enemy, encountering the Messenians in the middle between Ithome and Taygetus. Their approach was no surprise to Euphaes. Choosing his ground carefully he selected a site with one side bordering an impassable ravine between the Messenians and the Spartans.Nino Luraghi

Nino Luraghi (born 30 November 1964) is an Italian historian of ancient Greece, who holds the Wykeham Professorship of Ancient History at Oxford University.

Life

Luraghi is the son of Raimondo Luraghi (1921–2012), an Italian resistance fight ...

finds it "rather odd" that Euphaes stationed his army where it could not be attacked by the Spartans. Whether he questions the account or the general is not stated, but seen from a different view, the problem disappears.

Subsequent events demonstrate that Euphaes intended to build a fortified camp, which is what he did. The main goal of siting such a camp is to deny the enemy access to it. The Spartan commanders understood Euphaes very well. They sent a force upstream to cross the ravine and outflank the Messenians, preventing them from building a camp, but Euphaes had anticipated this move. Following the Spartans along the other side of the ravine with 500 cavalry and light infantry under Pytharatos and Antandros they prevented the Spartans from crossing. The camp was finished the next day.

The location of the ravine remains unknown nor does the battle have a name. Blocked, the Spartan army withdrew from Messenia. As it did not settle the war the battle is most often called inconclusive. As far as the tactical goals of the two armies are concerned, it was a Messenian victory.

The pitched battle in the vicinity of Ampheia

Both sides knew that in the next campaigning season a major battle would be fought. Meanwhile, at Sparta Alcmenes died and was replaced by his son, Polydorus. Cleonnis commanded the Messenian fortified camp. At the start of the season he took his command to the east to engage a Spartan army that was marching west from Sparta.Disposition of troops

They met on the plains beneath Taygetus at a still unknown location in Messenia, perhaps near Ampheia. The battle was mainly a heavy infantry engagement. The terms "light infantry" and "infantry" are being used by Pausanias. The Spartan army was mainly infantry. Some "light infantry" were present as Dryopians, an ethnic group of Pelasgians whose ancestors had been driven from Dryopia by the Dorians, who then called it Doris, and from their Achaean place of refuge, Asine, when Dorian Argos subjected it. They were finally offered protection by Dorian Sparta. These were drafted by the Spartans. Also present was a contingent of Cretan archers. Light troops played little part in the battle; they were mainly spectators. The two armies faced each other in traditional start lines. Euphaes yielded the command of the Messenian center to Cleonnis, while he took the left flank with Antandros, and Pythartos on the right. Facing Cleonnis was Euryleon, a noble Spartan and a Cadmid, with Polydorus on his left and Theopompus on the right. The latter in his harangue appealed to glory, wealth and the oath they had all taken. Euphaes chose to present death or slavery, pointing to the fate of Ampheia. The signal was given to advance simultaneously on both sides.The problem of the phalanx

phalanx

The phalanx ( grc, φάλαγξ; plural phalanxes or phalanges, , ) was a rectangular mass military formation, usually composed entirely of heavy infantry armed with spears, pikes, sarissas, or similar pole weapons. The term is particularly ...

, the unbroken line of men creating a killing zone in front of them. The chief weapon of the ancient Greek phalanx was the spear. Pausanias says that those who tried to plunder the dead "were speared and stabbed while they were too busy to see what was coming,...."

The paradox is that there is no supporting evidence of the use of the phalanx in Greece at that time. Anthony Snodgrass defined "the hoplite revolution," which included both the use of the phalanx in Greece and standardization of a "hoplite panoply" of arms and equipment. The panoply consisted of artifacts adapted from previous models: corselet, greaves, ankle guards, closed "Corinthian" helmet, large round shield with a band for the arm and a side grip, spear, long steel sword. Each element except the greaves is dated to 750-700 BC, perhaps earlier.

They are first depicted together on Proto-Corinthian vases of 675 BC for the panoply and the phalanx around 650 BC, much too late for either the Great Rhetra

The Great Rhetra ( el, Μεγάλη Ῥήτρα, literally: Great "Saying" or "Proclamation", charter) was used in two senses by the classical authors. In one sense, it was the Spartan Constitution, believed to have been formulated and establish ...

or the First Messenian War. Snodgrass dates the small figures of hoplites found in Sparta, "a sign of a unified and self-conscious hoplite class," as he believes, to not before 650. He then questions the date of the Great Rhetra, implying it should be reinterpreted or moved to the 7th century.

After Snodgrass published his analysis of pottery decoration there was a double effort to bring the Great Rhetra to a later time and find phalanxes in an earlier time, neither successful. The earliest evidence that John Salmon found was the vase paintings of the Macmillan Painter, who painted what appear to be phalanxes around the shoulders of Proto-Corinthian aryballoi. The Chigi Vase, for example, shows the overlapping shields, the spears, the grips of the shields and the corselets and closed helmets. It is dated 650; another, the Macmillan aryballos, to 655. The earliest of the series is an aryballos from Perchora dated 675, showing matched pairs, which are not necessarily phalanxes, but they fight in the presence of a flautist. These musicians were specific to phalanxes. They coordinated its movements.

The only supporting evidence for the phalanx therefore is dated to the time of the Second Messenian War

The Second Messenian War was a war which occurred ca. 660–650 BC between the Ancient Greek states of Messenia and Sparta, with localized resistance possibly lasting until the end of the century. It started around 40 years after the end of the F ...

, not the First. However, this is proof from a deficit. The vases may only demonstrate that depictions of phalanx warfare began at that time, not that phalanxes did. Pausanias on the other hand is positive evidence. Moreover, attempts to discount or select out what he says often create other problems. He is a vital part of all the evidence for the period.

Establishment of a fixed defense at Mt. Ithome

Not wanting to experience another such battle, the Messenians fell back to the heavily fortified Mount Ithome. This is when the Messenians first sent for help from the

Not wanting to experience another such battle, the Messenians fell back to the heavily fortified Mount Ithome. This is when the Messenians first sent for help from the Oracle

An oracle is a person or agency considered to provide wise and insightful counsel or prophetic predictions, most notably including precognition of the future, inspired by deities. As such, it is a form of divination.

Description

The word ...

at Delphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), in ancient times was a sacred precinct that served as the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient classical world. The orac ...

. They were told that a sacrifice of a royal virgin was the key to their success and the daughter of Aristodemus

In Greek mythology, Aristodemus (Ancient Greek: Ἀριστόδημος) was one of the Heracleidae, son of Aristomachus and brother of Cresphontes and Temenus. He was a great-great-grandson of Heracles and helped lead the fifth and final attac ...

, a Messenian hero, was chosen for the sacrifice.

Upon hearing of this, the Spartans held off from attacking Ithome for several years, before finally making a long march under their kings and killing the Messenian leader. Aristodemus was made the new Messenian king and led an offensive, meeting the enemy and driving them back into their own territory.

The Fall of Mt. Ithome

The Spartans then sent an envoy to Delphi and their following of her advice caused Messenian reverses so great that Aristodemus committed suicide and Ithome fell. The Messenians who had fortified themselves on the mountain either fled abroad or were captured and enslaved.Legacy

Sparta, under the rule of adiarchy

Diarchy (from ancient Greek, Greek , ''di-'', "double", and , ''-arkhía'', "ruled"),Occasionally misspelled ''dyarchy'', as in the ''Encyclopaedia Britannica'' article on the colonial British institution duarchy, or duumvirate (from Latin ', ...

, suddenly gained wealth and culture with the "socio-economic basis" of classical Sparta emerging from this war and expansion.Dunstan, ''Ancient Greece''. p.95 In 685 BC, a helot

The helots (; el, εἵλωτες, ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their ...

revolt caused a Second Messenian War

The Second Messenian War was a war which occurred ca. 660–650 BC between the Ancient Greek states of Messenia and Sparta, with localized resistance possibly lasting until the end of the century. It started around 40 years after the end of the F ...

.

In literature

F. L. Lucas

Frank Laurence Lucas (28 December 1894 – 1 June 1967) was an English classical scholar, literary critic, poet, novelist, playwright, political polemicist, Fellow of King's College, Cambridge, and intelligence officer at Bletchley Park during ...

's ''Messene Redeemed

F. L. Lucas's ''Messene Redeemed'' (1940) is a long poem (some 900 lines), based on Pausanias, about the struggle for independence of ancient Messene against Sparta. As well as narrating Messenian history from earliest times to the defeat of S ...

'' (1940) is a verse drama, based on Pausanias, about Messenian history, including episodes from the First Messenian War.

References

Bibliography

* * * {{Ancient Greek Wars 8th-century BC conflicts Messenian Wars 8th century BC in Greece Wars involving Sparta de:Messenische Kriege#1. Messenischer Krieg