Yosemite National Park (Part 1).ogg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Yosemite National Park ( ) is a

Accounts from this battalion were the first well-documented reports of European Americans entering Yosemite Valley. Attached to Savage's unit was Doctor

Accounts from this battalion were the first well-documented reports of European Americans entering Yosemite Valley. Attached to Savage's unit was Doctor

After the Mariposa War, Native Americans continued to live in the Yosemite area in reduced numbers. The remaining Yosemite

After the Mariposa War, Native Americans continued to live in the Yosemite area in reduced numbers. The remaining Yosemite

Muir and his

Muir and his

In 1937, conservationist

In 1937, conservationist

Yosemite National Park is located in the central Sierra Nevada. Three wilderness areas are adjacent to Yosemite: the Ansel Adams Wilderness to the southeast, the

Yosemite National Park is located in the central Sierra Nevada. Three wilderness areas are adjacent to Yosemite: the Ansel Adams Wilderness to the southeast, the

Almost all of the landforms are cut from the granitic rock of the

Almost all of the landforms are cut from the granitic rock of the

The Tuolumne and

The Tuolumne and  Yosemite is famous for its high concentration of waterfalls in a small area. Numerous sheer drops, glacial steps and hanging valleys in the park feature spectacular cascades, especially during April, May, and June (as the snow melts). Located in Yosemite Valley, Yosemite Falls is the fourth tallest waterfall in North America at according to the World Waterfall Database. Also in the valley is the much lower volume

Yosemite is famous for its high concentration of waterfalls in a small area. Numerous sheer drops, glacial steps and hanging valleys in the park feature spectacular cascades, especially during April, May, and June (as the snow melts). Located in Yosemite Valley, Yosemite Falls is the fourth tallest waterfall in North America at according to the World Waterfall Database. Also in the valley is the much lower volume

Yosemite has a

Yosemite has a

The location of the park was a

The location of the park was a

Starting 10 million years ago, vertical movement along the Sierra fault started to uplift the Sierra Nevada. Subsequent tilting of the Sierra block and the resulting accelerated uplift of the Sierra Nevada increased the

Starting 10 million years ago, vertical movement along the Sierra fault started to uplift the Sierra Nevada. Subsequent tilting of the Sierra block and the resulting accelerated uplift of the Sierra Nevada increased the

A series of glaciations further modified the region starting about 2 to 3 million years ago and ending sometime around 10,000 BP. At least four major glaciations occurred in the Sierra, locally called the Sherwin (also called the pre-Tahoe), Tahoe, Tenaya, and Tioga. The Sherwin glaciers were the largest, filling Yosemite and other valleys, while later stages produced much smaller glaciers. A Sherwin-age glacier was almost surely responsible for the major excavation and shaping of Yosemite Valley and other canyons in the area.

Glacial systems reached depths of up to and left their marks. The longest glacier ran down the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne River for , passing well beyond Hetch Hetchy Valley. Merced Glacier flowed out of Yosemite Valley and into the Merced River Gorge. Lee Vining Glacier carved Lee Vining Canyon and emptied into Lake Russel (the much-enlarged ice age version of Mono Lake). Only the highest peaks, such as Mount Dana and Mount Conness, were not covered by glaciers. Retreating glaciers often left recessional

A series of glaciations further modified the region starting about 2 to 3 million years ago and ending sometime around 10,000 BP. At least four major glaciations occurred in the Sierra, locally called the Sherwin (also called the pre-Tahoe), Tahoe, Tenaya, and Tioga. The Sherwin glaciers were the largest, filling Yosemite and other valleys, while later stages produced much smaller glaciers. A Sherwin-age glacier was almost surely responsible for the major excavation and shaping of Yosemite Valley and other canyons in the area.

Glacial systems reached depths of up to and left their marks. The longest glacier ran down the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne River for , passing well beyond Hetch Hetchy Valley. Merced Glacier flowed out of Yosemite Valley and into the Merced River Gorge. Lee Vining Glacier carved Lee Vining Canyon and emptied into Lake Russel (the much-enlarged ice age version of Mono Lake). Only the highest peaks, such as Mount Dana and Mount Conness, were not covered by glaciers. Retreating glaciers often left recessional

The park has an elevation range from and contains five major vegetation zones:

The park has an elevation range from and contains five major vegetation zones:

The black bears of Yosemite were once famous for breaking into parked cars to steal food. They were an encouraged tourist sight for many years at the park's garbage dumps, where they congregated to eat garbage and tourists gathered to photograph them. Increasing bear/human encounters and increasing property damage led to an aggressive campaign to discourage bears from interacting with people and their stuff. The open-air dumps were closed; trash receptacles were replaced with bear-proof receptacles; campgrounds were equipped with bear-proof food lockers so that people would not leave food in their vehicles. Because bears who show aggression towards people usually are destroyed, park personnel have come up with innovative ways to lead bears to associate humans and their property with experiences such as getting hit with a rubber bullet. , about 30 bears a year were captured and ear-tagged and their DNA sampled so that, when bear damage occurs, rangers can ascertain which bear was causing the problem.

Despite the richness of high-quality habitats in Yosemite, the

The black bears of Yosemite were once famous for breaking into parked cars to steal food. They were an encouraged tourist sight for many years at the park's garbage dumps, where they congregated to eat garbage and tourists gathered to photograph them. Increasing bear/human encounters and increasing property damage led to an aggressive campaign to discourage bears from interacting with people and their stuff. The open-air dumps were closed; trash receptacles were replaced with bear-proof receptacles; campgrounds were equipped with bear-proof food lockers so that people would not leave food in their vehicles. Because bears who show aggression towards people usually are destroyed, park personnel have come up with innovative ways to lead bears to associate humans and their property with experiences such as getting hit with a rubber bullet. , about 30 bears a year were captured and ear-tagged and their DNA sampled so that, when bear damage occurs, rangers can ascertain which bear was causing the problem.

Despite the richness of high-quality habitats in Yosemite, the  Yosemite National Park has documented the presence of more than 130 non-native plant species within park boundaries. They were introduced into Yosemite following the migration of early Euro-American settlers in the late 1850s. Natural and human-caused disturbances, such as wildland fires and construction activities, have contributed to a rapid increase in the spread of non-native plants. Some of these species invade and displace the native plant communities, impacting park resources. Non-native plants can bring about significant ecosystem changes by altering native plant communities and the processes that support them. Some non-native species may cause an increase in fire frequency or increase the available soil nitrogen that allow other non-native plants to establish. Many non-native species, such as

Yosemite National Park has documented the presence of more than 130 non-native plant species within park boundaries. They were introduced into Yosemite following the migration of early Euro-American settlers in the late 1850s. Natural and human-caused disturbances, such as wildland fires and construction activities, have contributed to a rapid increase in the spread of non-native plants. Some of these species invade and displace the native plant communities, impacting park resources. Non-native plants can bring about significant ecosystem changes by altering native plant communities and the processes that support them. Some non-native species may cause an increase in fire frequency or increase the available soil nitrogen that allow other non-native plants to establish. Many non-native species, such as

Indigenous residents intentionally set small fires in the early 1860s and before to clear the ground of brush as part as their farming practices. These fires are comparable to contemporary practices such as

Indigenous residents intentionally set small fires in the early 1860s and before to clear the ground of brush as part as their farming practices. These fires are comparable to contemporary practices such as

Over of trails are available to hikers—everything from an easy stroll to a challenging mountain hike, or backpacking trips. The popular Half Dome hike to the summit of

Over of trails are available to hikers—everything from an easy stroll to a challenging mountain hike, or backpacking trips. The popular Half Dome hike to the summit of

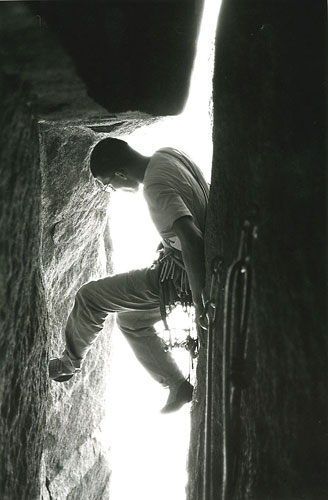

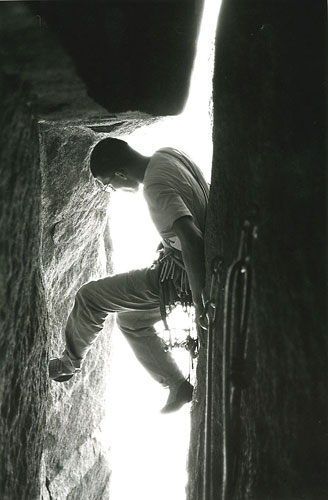

Rock climbing is an important part of Yosemite. In particular the valley is surrounded by summits such as Half Dome and El Capitan. Camp 4 is a walk-in campground in the Valley that was instrumental in the development of rock climbing as a sport, and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Climbers can generally be spotted in the snow-free months on anything from ten-foot-high (3 m) boulders to the face of El Capitan. Classes on rock climbing are offered there.

Tuolumne Meadows is well known for rock and mountain climbing.

Rock climbing is an important part of Yosemite. In particular the valley is surrounded by summits such as Half Dome and El Capitan. Camp 4 is a walk-in campground in the Valley that was instrumental in the development of rock climbing as a sport, and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Climbers can generally be spotted in the snow-free months on anything from ten-foot-high (3 m) boulders to the face of El Capitan. Classes on rock climbing are offered there.

Tuolumne Meadows is well known for rock and mountain climbing.

Away from the Valley, the park is snowed in during the winter months, with many roads closed.

Away from the Valley, the park is snowed in during the winter months, with many roads closed.

Features of the Proposed Yosemite National Park

" ''The Century; a popular quarterly'' (Sept. 1890) 40#5 * * * * ** ** ** ** **

* * from American Studies at the University of Virginia

Project Yosemite , Yosemite HD , Motion Timelapse Video

* *

Project Yosemite timelapse photography

* {{Authority control World Heritage Sites in California 1890 establishments in California Protected areas established in 1890 Sierra Nevada (United States) Parks in Madera County, California Parks in Mariposa County, California Parks in Tuolumne County, California World Heritage Sites in the United States Hetch Hetchy Project Protected areas of the Sierra Nevada (United States) National parks in California Nature centers in California Articles with WikiMiniAtlas displaying incorrectly; WMA not showing area

national park

A national park is a nature park, natural park in use for conservation (ethic), conservation purposes, created and protected by national governments. Often it is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state dec ...

in California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

. It is bordered on the southeast by Sierra National Forest

Sierra National Forest is a U.S. national forest located on the western slope of central Sierra Nevada in Central California and bounded on the northwest by Yosemite National Park and the south by Kings Canyon National Park. The forest is kno ...

and on the northwest by Stanislaus National Forest

Stanislaus National Forest is a U.S. National Forest which manages of land in four counties in the Sierra Nevada in Northern California. It was established on February 22, 1897, making it one of the oldest national forests. It was named after t ...

. The park is managed by the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an agency of the United States federal government within the U.S. Department of the Interior that manages all national parks, most national monuments, and other natural, historical, and recreational propertie ...

and covers in four countiescentered in Tuolumne and Mariposa, extending north and east to Mono

Mono may refer to:

Common meanings

* Infectious mononucleosis, "the kissing disease"

* Monaural, monophonic sound reproduction, often shortened to mono

* Mono-, a numerical prefix representing anything single

Music Performers

* Mono (Japanese b ...

and south to Madera. Designated a World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for h ...

in 1984, Yosemite is internationally recognized for its granite cliffs, waterfalls, clear streams, groves of giant sequoia, lakes, mountains, meadows, glaciers, and biological diversity

Biodiversity or biological diversity is the variety and variability of life on Earth. Biodiversity is a measure of variation at the genetic (''genetic variability''), species (''species diversity''), and ecosystem (''ecosystem diversity'') lev ...

. Almost 95 percent of the park is designated wilderness

Wilderness or wildlands (usually in the plural), are natural environments on Earth that have not been significantly modified by human activity or any nonurbanized land not under extensive agricultural cultivation. The term has traditionally re ...

. Yosemite is one of the largest and least fragmented habitat blocks in the Sierra Nevada

The Sierra Nevada () is a mountain range in the Western United States, between the Central Valley of California and the Great Basin. The vast majority of the range lies in the state of California, although the Carson Range spur lies primarily ...

.

Its geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Ear ...

is characterized by granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained (phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies undergro ...

and remnants of older rock. About 10 million years ago, the Sierra Nevada

The Sierra Nevada () is a mountain range in the Western United States, between the Central Valley of California and the Great Basin. The vast majority of the range lies in the state of California, although the Carson Range spur lies primarily ...

was uplifted and tilted to form its unique slopes, which increased the steepness of stream and river beds, forming deep, narrow canyons. About one million years ago glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its Ablation#Glaciology, ablation over many years, often Century, centuries. It acquires dis ...

s formed at higher elevations. They moved downslope, cutting and sculpting the U-shaped Yosemite Valley

Yosemite Valley ( ; ''Yosemite'', Miwok for "killer") is a U-shaped valley, glacial valley in Yosemite National Park in the western Sierra Nevada (U.S.), Sierra Nevada mountains of Central California. The valley is about long and deep, surroun ...

.

European American settlers first entered the valley in 1851. Other travelers entered earlier, but James D. Savage James D. Savage (born November 14, 1951) is a political science professor at the University of Virginia who teaches public policy in the Department of Politics and the Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy. He is an expert in governmen ...

is credited with discovering the area that became Yosemite National Park. Native Americans had inhabited the region for nearly 4,000 years, although humans may have first visited as long as 8,000 to 10,000 years ago.

Yosemite was critical to the development of the concept of national parks. Galen Clark

Galen Clark (March 28, 1814 – March 24, 1910) was a Canadian-born American conservationist and writer. He is known as the first European American to discover the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoia trees, and is notable for his role in gaining leg ...

and others lobbied to protect Yosemite Valley from development, ultimately leading to President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

's signing of the Yosemite Grant of 1864 that declared Yosemite as federally preserved land. In 1890, John Muir

John Muir ( ; April 21, 1838December 24, 1914), also known as "John of the Mountains" and "Father of the National Parks", was an influential Scottish-American naturalist, author, environmental philosopher, botanist, zoologist, glaciologist, a ...

led a successful movement to motivate Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

to establish Yosemite Valley and its surrounding areas as a National Park. This helped pave the way for the National Park System. Yosemite draws about four million visitors annually. Most visitors spend the majority of their time in the valley's . The park set a visitation record in 2016, surpassing five million visitors for the first time. In 2023, the park saw nearly four million visitors.

Toponym

The word ''Yosemite'' (derived from ''yohhe'meti,'' "they are killers" inMiwok

The Miwok (also spelled Miwuk, Mi-Wuk, or Me-Wuk) are members of four linguistically related Native American groups indigenous to what is now Northern California, who traditionally spoke one of the Miwok languages in the Utian family. The word ' ...

) historically referred to the name that the Miwok

The Miwok (also spelled Miwuk, Mi-Wuk, or Me-Wuk) are members of four linguistically related Native American groups indigenous to what is now Northern California, who traditionally spoke one of the Miwok languages in the Utian family. The word ' ...

gave to the Ahwahneechee

The Ahwahnechee are a Native American people who traditionally lived in the Yosemite Valley and still live in surrounding area. They are the seven tribes of Yosemite Miwok, Northern Paiute, Kucadikadi Mono Lake people. As one of the most docume ...

People, the resident indigenous tribe. Previously, the region had been called "Ahwahnee" ("big mouth") by its only indigenous inhabitants, the Ahwahneechee. The term ''Yosemite'' in Miwok is easily confused with a similar term for "grizzly bear", and is still a common misconception.

History

Ahwahneechee and the Mariposa Wars

The indigenous natives of Yosemite called themselves theAhwahneechee

The Ahwahnechee are a Native American people who traditionally lived in the Yosemite Valley and still live in surrounding area. They are the seven tribes of Yosemite Miwok, Northern Paiute, Kucadikadi Mono Lake people. As one of the most docume ...

, meaning "dwellers" in Ahwahnee. The Ahwahneechee People were the only tribe that lived within the park boundaries, but other tribes lived in surrounding areas. Together they formed a larger Indigenous population in California, called the Southern Sierra Miwok. They are related to the Northern Paiute and Mono

Mono may refer to:

Common meanings

* Infectious mononucleosis, "the kissing disease"

* Monaural, monophonic sound reproduction, often shortened to mono

* Mono-, a numerical prefix representing anything single

Music Performers

* Mono (Japanese b ...

tribes. Other tribes like the Central Sierra Miwoks

The Plains and Sierra Miwok were once the largest group of California Indian Miwok people, indigenous to California. Their homeland included regions of the Sacramento Valley, San Joaquin Valley, and the Sierra Nevada.

Geography

The Plains an ...

and the Yokuts

The Yokuts (previously known as MariposasPowell, 1891:90–91.) are an ethnic group of Native Americans native to central California. Before European contact, the Yokuts consisted of up to 60 tribes speaking several related languages. ''Yokuts ...

, who both lived in the San Joaquin Valley

The San Joaquin Valley ( ; es, Valle de San Joaquín) is the area of the Central Valley of the U.S. state of California that lies south of the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta and is drained by the San Joaquin River. It comprises seven c ...

and central California, visited Yosemite to trade and intermarry. This resulted in a blending of culture that helped preserve their presence in Yosemite after early American settlements and urban development threatened their survival. Vegetation and game in the region were similar to modern times; acorns were a dietary staple, as well as other seeds and plants, salmon and deer.

The 1848–1855 California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California fro ...

was a major event impacting the native population. It drew more than 90,000 European Americans to the area in 1849, causing competition for resources between gold miners and residents. About 70 years before the Gold Rush, the indigenous population was estimated to be 300,000, quickly dropping to 150,000, and just ten years later, only about 50,000 remained. The reasons for such a decline included disease, birth rate decreases, starvation, and conflict. The conflict in Yosemite, which is known as the Mariposa War, was part of the California genocide, which was the systemic killing of indigenous peoples throughout the State between the 1840s and 1870s. It started in December 1850 when California funded a state militia to drive Native people from contested territory to suppress Native American resistance to the European American influx.

Yosemite tribes often stole from settlers and miners, sometimes killing them, in retribution for the extermination/domestication of their people, and loss of their lands and resources. The War and formation of the Mariposa Battalion was partially the result of a single incident involving James Savage, a Fresno trader whose trading post was attacked in December, 1850. After the incident, Savage rallied other miners and gained the support of local officials to pursue a war against the Natives. He was appointed United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

Major and leader of the Mariposa Battalion in the beginning of 1851. He and Captain John Boling were responsible for pursuing the Ahwahneechee people, led by Chief Tenaya

Tenaya (died 1853) was a leader of the Ahwahnechee people in Yosemite Valley, California.

Background

Tenaya's father was a leader of the Ahwahnechee people (or Awahnichi). The Ahwahneechee had become a tribe distinct from the other tribes in th ...

and driving them west, and out of Yosemite. In March 1851 under Savage's command, the Mariposa Battalion captured about 70 Ahwahneechee and planned to take them to a reservation in Fresno, but they escaped. Later in May, under the command of Boling, the battalion captured 35 Ahwahneechee, including Chief Tenaya, and marched them to the reservation. Most were allowed to eventually leave and the rest escaped. Tenaya and others fled across the Sierra Nevada

The Sierra Nevada () is a mountain range in the Western United States, between the Central Valley of California and the Great Basin. The vast majority of the range lies in the state of California, although the Carson Range spur lies primarily ...

and settled with the Mono Lake Paiutes

The Kucadikadi are a band of Northern Paiute people who live near Mono Lake in Mono County, California. They are the southernmost band of Northern Paiute.Fowler and Liljeblad 437Arkush, Brooke S"Historic Northern Paiute Winter Houses in Mono Basi ...

. Tenaya and some of his companions were ultimately killed in 1853 either over stealing horses or a gambling conflict. The survivors of Tenaya's group and other Ahwahneechee

The Ahwahnechee are a Native American people who traditionally lived in the Yosemite Valley and still live in surrounding area. They are the seven tribes of Yosemite Miwok, Northern Paiute, Kucadikadi Mono Lake people. As one of the most docume ...

were absorbed into the Mono Lake Paiute tribe.

Accounts from this battalion were the first well-documented reports of European Americans entering Yosemite Valley. Attached to Savage's unit was Doctor

Accounts from this battalion were the first well-documented reports of European Americans entering Yosemite Valley. Attached to Savage's unit was Doctor Lafayette Bunnell

Lafayette Houghton Bunnell (March 13, 1824 – July 21, 1903) was an American physician, author, and explorer. He is most well known for his involvement with the Mariposa Battalion, the first non-Indians to enter Yosemite Valley, and his book Dis ...

, who later wrote about his awestruck impressions of the valley in ''The Discovery of the Yosemite''. Bunnell is credited with naming Yosemite Valley, based on his interviews with Chief Tenaya. Bunnell wrote that Chief Tenaya was the founder of the Ahwahnee colony. Bunnell falsely believed that the word "Yosemite" meant "full-grown grizzly bear".

Indigenous peoples' continuing presence

After the Mariposa War, Native Americans continued to live in the Yosemite area in reduced numbers. The remaining Yosemite

After the Mariposa War, Native Americans continued to live in the Yosemite area in reduced numbers. The remaining Yosemite Ahwahneechee

The Ahwahnechee are a Native American people who traditionally lived in the Yosemite Valley and still live in surrounding area. They are the seven tribes of Yosemite Miwok, Northern Paiute, Kucadikadi Mono Lake people. As one of the most docume ...

tribe members there were forced to relocate to a village constructed in 1851 by the state government. They learned to live within this camp and their limited rights, adapting to the changed environment by entering the tourism industry through employment and small businesses, manufacturing and selling goods and providing services. In 1953, the National Park Service banned all non-employee Natives from residing in the Park and evicted the non-employees who had residence. In 1969, with only a few families left in the Park, the National Park Service evicted the remaining Native people living within in the Park (all Park employees and their families) to a government housing area for park employees and destroyed the village as part of a fire-fighting exercise. A reconstructed "Indian Village of Ahwahnee" sits behind the Yosemite Museum

The Yosemite Museum is located in Yosemite Valley in Yosemite National Park in California. Founded in 1926 through the efforts of Ansel Franklin Hall, the museum's displays focus on the heritage and culture of the Ahwahnechee people who lived ...

, located next to the Yosemite Valley Visitor Center.

By the late 19th century, the population of all native inhabitants in Yosemite was difficult to determine, estimates ranged from thirty to several hundred. The Ahwahneechee people and their descendants were hard to identify. The last full-blooded Ahwahneechee died in 1931. Her name was Totuya, or Maria Lebrado. She was the granddaughter of Chief Tenaya

Tenaya (died 1853) was a leader of the Ahwahnechee people in Yosemite Valley, California.

Background

Tenaya's father was a leader of the Ahwahnechee people (or Awahnichi). The Ahwahneechee had become a tribe distinct from the other tribes in th ...

and one of many forced out of her ancestral homelands. The Ahwahneechee live through the memory of their descendants, their fellow Yosemite Natives, and through the Yosemite exhibit in the Smithsonian and the Yosemite Museum. As a method of self-preservation and resilience, the Indigenous people of California proposed treaties in 1851 and 1852 that would have established land reservations for them, but Congress refused to ratify them. The Southern Sierra Miwuk Nation is seeking tribal sovereignty and federal recognition. The National Park Service created policies to protect sacred sites and allow Native People to return to their homelands and use National Park resources.

Early tourists

In 1855, entrepreneurJames Mason Hutchings

James Mason Hutchings (February 10, 1820 – October 31, 1902) was an American businessman and one of the principal promoters of what is now Yosemite National Park.

Biography

Born in Towcester in England, Hutchings immigrated to the U.S. i ...

, artist Thomas Ayres and two others were the first tourists to visit. Hutchings and Ayres were responsible for much of Yosemite's earliest publicity, writing articles and special issues about the valley. Ayres' style was detailed with exaggerated angularity. His works and written accounts were distributed nationally, and an exhibition of his drawings was held in New York City. Hutchings' publicity efforts between 1855 and 1860 increased tourism to Yosemite. Natives supported the growing tourism industry by working as laborers or maids. Later, they performed dances for tourists, acted as guides, and sold handcrafted goods, notably woven baskets. The Indian village and its peoples fascinated visitors, especially James Hutchings who advocated for Yosemite tourism. He and others considered the indigenous presence to be one of Yosemite's greatest attractions.

Wawona was an early Indian encampment for Nuchu and Ahwahneechee people who were captured and relocated to a reservation on the Fresno River by Savage and the Mariposa Battalion in March 1851. Galen Clark

Galen Clark (March 28, 1814 – March 24, 1910) was a Canadian-born American conservationist and writer. He is known as the first European American to discover the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoia trees, and is notable for his role in gaining leg ...

discovered the Mariposa Grove

Mariposa Grove is a sequoia grove located near Wawona, California, United States, in the southernmost part of Yosemite National Park. It is the largest grove of giant sequoias in the park, with several hundred mature examples of the tree. Two of i ...

of giant sequoia in Wawona in 1857. He had simple lodgings and roads built. In 1879, the Wawona Hotel

The Wawona Hotel is a historic hotel located within southern Yosemite National Park, in California. It was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1987, and is on the National Register of Historic Places .

History

The Wawona Hotel is one of the ...

was built to serve tourists visiting Mariposa Grove. As tourism increased, so did the number of trails and hotels to build on it.

The Wawona Tree

The Wawona Tree, also known as the Wawona Tunnel Tree, was a famous giant sequoia that stood in Mariposa Grove, Yosemite National Park, California, USA, until February 1969. It had a height of and was in diameter at the base.

The origin of the ...

, also known as the Tunnel Tree

A tunnel tree is a large tree in whose trunk a tunnel has been drilled. This practice took place mainly at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century in the west of the United States.

The tunnel allowed tourists to walk or drive through ...

, was a giant sequoia that grew in the Mariposa Grove

Mariposa Grove is a sequoia grove located near Wawona, California, United States, in the southernmost part of Yosemite National Park. It is the largest grove of giant sequoias in the park, with several hundred mature examples of the tree. Two of i ...

. It was tall, and was in circumference. When a carriage-wide tunnel was cut through the tree in 1881, it became even more popular as a tourist photo attraction. Carriages and automobiles, traversed the road that passed through the tree. The tree was permanently weakened by the tunnel, and it fell in 1969 under a heavy load of snow. It was estimated to have been 2,100 years old.

Yosemite's first concession was established in 1884 when John Degnan and his wife established a bakery and store. In 1916, the National Park Service granted a 20-year concession to the Desmond Park Service Company. It bought out or built hotels, stores, camps, a dairy, a garage, and other park facilities. The Hotel Del Portal

Hotel Del Portal was one of the early first-class hotels established by the Yosemite Valley Railroad to take passengers from Merced to the terminus at El Portal, California, just outside of Yosemite National Park. The hotel set the standard for ...

was completed in 1908 by a subsidiary of the Yosemite Valley Railroad

The Yosemite Valley Railroad (YVRR) was a short-line railroad operating from 1907 to 1945 in the state of California, mostly following the Merced River from Merced to Yosemite National Park, carrying a mixture of passenger and freight traffic. ...

. It was located at El Portal, California

El Portal (Spanish for "The Gateway") is a census-designated place in Mariposa County, California, United States. It is located west-southwest of Yosemite Village, at an elevation of . The population was 372 at the 2020 census, down from 474 at ...

just outside of Yosemite.

The Curry Company started in 1899, led by David and Jennie Curry to provide concessions. They founded Camp Curry, now Curry Village

Curry Village is a resort in Mariposa County, California in Yosemite National Park within the Yosemite Valley.

A rockfall in 2008 damaged a number of structures, and about one third of visitor units were closed because of risk. In 2012, eight vi ...

.

Park service administrators felt that limiting the number of concessionaires in the park would be more financially sound. The Curry Company and its rival, the Yosemite National Park Company, were forced to merge in 1925 to form the Yosemite Park & Curry Company

The Ahwahnee Hotel is a grand hotel in Yosemite National Park, California, on the floor of Yosemite Valley. It was built by the Yosemite Park and Curry Company and opened for business in 1927. The hotel is constructed of steel, stone, concret ...

(YP&CC). The company built the Ahwahnee Hotel in 1926–27.

Yosemite Grant

Concerned by the impact of commercial interests, citizens includingGalen Clark

Galen Clark (March 28, 1814 – March 24, 1910) was a Canadian-born American conservationist and writer. He is known as the first European American to discover the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoia trees, and is notable for his role in gaining leg ...

and Senator John Conness

John Conness (September 22, 1821 – January 10, 1909) was a first-generation Irish-American businessman who served as a U.S. Senator (1863–1869) from California during the American Civil War and the early years of Reconstruction. He intr ...

advocated protection for the area. The 38th United States Congress

The 38th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1863, ...

passed legislation that was signed by President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

on June 30, 1864, creating the Yosemite Grant. This is the first time land was set aside specifically for preservation and public use by the U.S. government, and set a precedent for the 1872 creation of Yellowstone

Yellowstone National Park is an American national park located in the western United States, largely in the northwest corner of Wyoming and extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U.S. Congress with the Yellowston ...

national park, the nation's first. Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove

Mariposa Grove is a sequoia grove located near Wawona, California, United States, in the southernmost part of Yosemite National Park. It is the largest grove of giant sequoias in the park, with several hundred mature examples of the tree. Two of i ...

were ceded to California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

as a state park

State parks are parks or other protected areas managed at the sub-national level within those nations which use "state" as a political subdivision. State parks are typically established by a state to preserve a location on account of its natural ...

, and a board of commissioners was established two years later.

Galen Clark was appointed by the commission as the Grant's first guardian, but neither Clark nor the commissioners had the authority to evict homesteaders

The Homestead Acts were several laws in the United States by which an applicant could acquire ownership of government land or the public domain, typically called a homestead. In all, more than of public land, or nearly 10 percent of th ...

(which included Hutchings). The issue was not settled until 1872 when the homesteader land holdings were invalidated by the U.S. Supreme Court. Clark and the commissioners were ousted in a dispute that reached the Supreme Court in 1880. The two Supreme Court decisions affecting management of the Yosemite Grant are considered precedents in land management law. Hutchings became the new park guardian.

Tourist access to the park improved, and conditions in the Valley became more hospitable. Tourism significantly increased after the first transcontinental railroad

North America's first transcontinental railroad (known originally as the "Pacific Railroad" and later as the " Overland Route") was a continuous railroad line constructed between 1863 and 1869 that connected the existing eastern U.S. rail netwo ...

was completed in 1869, while the long horseback ride to reach the area was a deterrent. Three stagecoach

A stagecoach is a four-wheeled public transport coach used to carry paying passengers and light packages on journeys long enough to need a change of horses. It is strongly sprung and generally drawn by four horses although some versions are draw ...

roads were built in the mid-1870s to provide better access for the growing number of visitors.

John Muir

John Muir ( ; April 21, 1838December 24, 1914), also known as "John of the Mountains" and "Father of the National Parks", was an influential Scottish-American naturalist, author, environmental philosopher, botanist, zoologist, glaciologist, a ...

was a Scottish-born American naturalist and explorer. Muir's leadership ensured that many National Parks were left untouched, including Yosemite.

Muir wrote articles popularizing the area and increasing scientific interest in it. Muir was one of the first to theorize that the major landforms in Yosemite Valley were created by alpine glaciers, bucking established scientists such as Josiah Whitney. Muir wrote scientific papers on the area's biology. Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted

Frederick Law Olmsted (April 26, 1822August 28, 1903) was an American landscape architect, journalist, social critic, and public administrator. He is considered to be the father of landscape architecture in the USA. Olmsted was famous for co- ...

emphasized the importance of conservation of Yosemite Valley.

Increased protection efforts

Overgrazing of meadows (especially by sheep), logging of giant sequoia, and other damage led Muir to become an advocate for further protection. Muir convinced prominent guests of the importance of putting the area under federal protection. One such guest wasRobert Underwood Johnson

Robert Underwood Johnson (January 12, 1853 – October 14, 1937) was an American writer, poet, and diplomat.

Biography

Robert Underwood Johnson was born in Centerville, Indiana, on January 12, 1853. His brother Henry Underwood Johnson b ...

, editor of ''Century Magazine

''The Century Magazine'' was an illustrated monthly magazine first published in the United States in 1881 by The Century Company of New York City, which had been bought in that year by Roswell Smith and renamed by him after the Century Associati ...

''. Muir and Johnson lobbied Congress for the Act that created Yosemite National Park on October 1, 1890. The State of California, however, retained control of Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove. Muir's writings raised awareness about the damage caused by sheep grazing, and he actively campaigned to virtually eliminate grazing from the Yosemite's high-country.

The newly created national park came under the jurisdiction of the United States Army's Troop I of the 4th Cavalry on May 19, 1891, which set up camp in Wawona with Captain Abram Epperson Wood as acting superintendent. By the late 1890s, sheep grazing was no longer a problem, and the Army made other improvements. However, the cavalry could not intervene to ease the worsening conditions. From 1899 to 1913, cavalry regiments of the Western Department, including the all Black 9th Cavalry

The 9th Cavalry Regiment is a parent cavalry regiment of the United States Army. It is not related to the 9th Kansas Cavalry Regiment of the Union Army. Historically, it was one of the Army's four segregated African-American regiments and was ...

(known as the "Buffalo Soldiers") and the 1st Cavalry, stationed two troops at Yosemite.

Muir and his

Muir and his Sierra Club

The Sierra Club is an environmental organization with chapters in all 50 United States, Washington D.C., and Puerto Rico. The club was founded on May 28, 1892, in San Francisco, California, by Scottish-American preservationist John Muir, who be ...

continued to lobby the government and influential people for the creation of a unified Yosemite National Park. In May 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

camped with Muir near Glacier Point for three days. On that trip, Muir convinced Roosevelt to take control of Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove away from California and return it to the federal government. In 1906, Roosevelt signed a bill that shifted control.

National Park Service

TheNational Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an agency of the United States federal government within the U.S. Department of the Interior that manages all national parks, most national monuments, and other natural, historical, and recreational propertie ...

(NPS) was formed in 1916, and Yosemite was transferred to that agency's jurisdiction. Tuolumne Meadows Lodge, Tioga Pass Road

State Route 120 (SR 120) is a state highway in the central part of California, connecting the San Joaquin Valley with the Sierra Nevada, Yosemite National Park, and the Mono Lake area. Its western terminus is at Interstate 5 in Lathrop, and its ...

, and campgrounds at Tenaya and Merced lakes were also completed in 1916. Automobiles started to enter the park in ever-increasing numbers following the opening of all-weather highways to the park. The Yosemite Museum was founded in 1926 through the efforts of Ansel Franklin Hall

Ansel F. Hall (May 6, 1894 in Oakland, California – March 28, 1962) was an American naturalist. He was the first Chief Naturalist and first Chief Forester of the United States National Park Service.

Early career

Hall was graduated in 1917 from ...

. In the 1920s, the museum featured Native Americans practicing traditional crafts, and many Southern Sierra Miwok continued to live in Yosemite Valley until they were evicted from the park in the 1960s. Although the NPS helped create a museum that included Native American culture, its early actions and organizational values were dismissive of Yosemite Natives and the Ahwahneechee. NPS in the early 20th century criticized and restricted the expression of indigenous culture and behavior. For example, park officials penalized Natives for playing games and drinking during the Indian Field Days of 1924. In 1929, Park Superintendent Charles G. Thomson concluded that the Indian village was aesthetically unpleasant and was limiting white settler development and ordered the camp to be burned down. In 1969, many Native residents left in search of work as a result of the decline in tourism. NPS demolished their empty houses, evicted the remaining residents, and destroyed the entire village. This was the last Indigenous settlement within the park.

In 1903, a dam in Hetch Hetchy Valley

Hetch Hetchy is a valley, a reservoir, and a water system in California in the United States. The glacial Hetch Hetchy Valley lies in the northwestern part of Yosemite National Park and is drained by the Tuolumne River. For thousands of years bef ...

in the northwestern region of the park was proposed. Its purpose was to provide water and hydroelectric power to San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

. Muir and the Sierra Club opposed the project, while others, including Gifford Pinchot, supported it. In 1913, the O'Shaughnessy Dam was approved via passage of the Raker Act The Raker Act was an act of the United States Congress that permitted building of the O'Shaughnessy Dam and flooding of Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park, California. It is named for John E. Raker, its chief sponsor. The Act, passed by ...

.

In 1918, Clare Marie Hodges

Clare Marie Hodges (1890–1970) was the first paid female ranger for the National Park Service, working at Yosemite National Park.

Early life

Clare Marie Hodges was born in Santa Cruz, California, Santa Cruz in 1890. She first visited Yosemit ...

was hired as the first female Park Ranger in Yosemite. Following Hodges in 1921, Enid Michael was hired as a seasonal Park Ranger and continued to serve in that position for 20 years.

In 1937, conservationist

In 1937, conservationist Rosalie Edge

Rosalie Barrow Edge (November 3, 1877 – November 30, 1962) was an American environmentalist and suffragist. In 1929, she established the Emergency Conservation Committee to expose the conservation establishment's ineffectiveness and advocate ...

, head of the Emergency Conservation Committee (ECC), successfully lobbied Congress to purchase about of old-growth sugar pines on the perimeter of Yosemite National Park that were to be logged.

By 1968, traffic congestion

Traffic congestion is a condition in transport that is characterized by slower speeds, longer trip times, and increased vehicular queueing. Traffic congestion on urban road networks has increased substantially since the 1950s. When traffic de ...

and parking in Yosemite Valley during the summer months has become a concern. NPS reduced artificial inducements to visit the park, such as the '' Firefall'', in which red-hot embers were pushed off a cliff near Glacier Point at night.

In 1984, preservationists persuaded Congress to designate , or about 89 percent of the park, as the Yosemite Wilderness. As a wilderness area

Wilderness or wildlands (usually in the plural), are natural environments on Earth that have not been significantly modified by human activity or any nonurbanized land not under extensive agricultural cultivation. The term has traditionally re ...

, it would be preserved in its natural state with humans being only temporary visitors.

In 2016, The Trust for Public Land

The Trust for Public Land is a U.S. nonprofit organization with a mission to "create parks and protect land for people, ensuring healthy, livable communities for generations to come". Since its founding in 1972, the Trust for Public Land has compl ...

(TPL) purchased Ackerson Meadow, a on the western edge of the park for $2.3 million. Ackerson Meadow was originally included in the proposed 1890 park boundary, but never acquired by the federal government. The purchase and donation of the meadow was made possible through a cooperative effort by TPL, NPS, and Yosemite Conservancy. On September 7, 2016, NPS accepted the donation of the land, making the meadow the largest addition to Yosemite since 1949.

Geography

Yosemite National Park is located in the central Sierra Nevada. Three wilderness areas are adjacent to Yosemite: the Ansel Adams Wilderness to the southeast, the

Yosemite National Park is located in the central Sierra Nevada. Three wilderness areas are adjacent to Yosemite: the Ansel Adams Wilderness to the southeast, the Hoover Wilderness

The Hoover Wilderness is a wilderness area in the Inyo and Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forests. It lies to the east of the crest of the central Sierra Nevada in California, to the north and east of Yosemite National Park - a long strip stretchin ...

to the northeast, and the Emigrant Wilderness

The Emigrant Wilderness of Stanislaus National Forest is a wilderness area in the Sierra Nevada. It is bordered by Yosemite National Park on the south, the Toiyabe National Forest and the Hoover Wilderness on the east, and State Route 108 ...

to the north.

The park contains thousands of lakes and ponds, of streams, of hiking trails, and of roads. Two federally designated Wild and Scenic River

The National Wild and Scenic Rivers System was created by the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968 (Public Law 90-542), enacted by the U.S. Congress to preserve certain rivers with outstanding natural, cultural, and recreational values in a free- ...

s, the Merced

Merced (; Spanish for "Mercy") is a city in, and the county seat of, Merced County, California, United States, in the San Joaquin Valley. As of the 2020 Census, the city had a population of 86,333, up from 78,958 in 2010. Incorporated on April 1 ...

and the Tuolumne, begin within Yosemite's borders and flow westward through the Sierra foothills into the Central Valley of California

The Central Valley is a broad, elongated, flat valley that dominates the interior of California. It is wide and runs approximately from north-northwest to south-southeast, inland from and parallel to the Pacific coast of the state. It covers ...

.

Rocks and erosion

Sierra Nevada Batholith

The Sierra Nevada Batholith is a large batholith which forms the core of the Sierra Nevada mountain range in California, exposed at the surface as granite.

The batholith is composed of many individual masses of rock called ''plutons'', which fo ...

(a batholith

A batholith () is a large mass of intrusive igneous rock (also called plutonic rock), larger than in area, that forms from cooled magma deep in Earth's crust. Batholiths are almost always made mostly of felsic or intermediate rock types, such ...

is a large mass of intrusive igneous rock

Igneous rock (derived from the Latin word ''ignis'' meaning fire), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main The three types of rocks, rock types, the others being Sedimentary rock, sedimentary and metamorphic rock, metamorphic. Igneous rock ...

that formed deep below the surface). About five percent of the park's landforms (mostly in its eastern margin near Mount Dana) are metamorphosed volcanic

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plates a ...

and sedimentary rock

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock that are formed by the accumulation or deposition of mineral or organic particles at Earth's surface, followed by cementation. Sedimentation is the collective name for processes that cause these particles ...

s. These roof pendants

In structural geology, a roof pendant, also known as a pendant, is a mass of country rock that projects downward into and is entirely surrounded by an igneous intrusion such as a batholith or other pluton. In lay terminology sometimes "rock hat" ...

once formed the roof over the underlying granitic magma.

Erosion

Erosion is the action of surface processes (such as water flow or wind) that removes soil, rock, or dissolved material from one location on the Earth's crust, and then transports it to another location where it is deposited. Erosion is distin ...

acting upon different types of uplift-generated joint and fracture systems is responsible for producing the valleys, canyons, domes

A dome () is an architectural element similar to the hollow upper half of a sphere. There is significant overlap with the term cupola, which may also refer to a dome or a structure on top of a dome. The precise definition of a dome has been a m ...

, and other features. These joints and fracture systems do not move, and are therefore not faults. Spacing between joints is controlled by the amount of silica

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , most commonly found in nature as quartz and in various living organisms. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is one ...

in the granite and granodiorite rocks; more silica tends to form a more resistant rock, resulting in larger spaces between joints and fractures.

Pillars and columns, such as Washington Column

Washington Column is a roughly 1800-foot high rock formation, arising from Yosemite Valley. It is east of the Royal Arches, behind the Ahwahnee Hotel. North Dome

North Dome is a granite dome in Yosemite National Park, California. It is the ...

and Lost Arrow, are generated by cross joints. Erosion acting on master joints is responsible for shaping valleys and later canyons. The single most erosive force over the last few million years has been large alpine glaciers

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires distinguishing features, such as ...

, which turned the previously V-shaped river-cut valleys into U-shaped glacial-cut canyons (such as Yosemite Valley and Hetch Hetchy Valley). Exfoliation (caused by the tendency of crystal

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macros ...

s in pluton

In geology, an igneous intrusion (or intrusive body or simply intrusion) is a body of intrusive igneous rock that forms by crystallization of magma slowly cooling below the surface of the Earth. Intrusions have a wide variety of forms and com ...

ic rocks to expand at the surface) acting on granitic rock with widely spaced joints is responsible for producing domes such as Half Dome

Half Dome is a granite dome at the eastern end of Yosemite Valley in Yosemite National Park, California. It is a well-known rock formation in the park, named for its distinct shape. One side is a sheer face while the other three sides are smooth ...

and North Dome

North Dome is a granite dome in Yosemite National Park, California. It is the southernmost summit of Indian Ridge, north of Washington Column and the Royal Arches on the northeastern wall of Yosemite Valley. It can be reached by trail from th ...

and inset arches like Royal Arches.

Popular features

Yosemite Valley represents only one percent of the park area. TheTunnel View

Tunnel View is a scenic viewpoint on California State Route 41 in Yosemite National Park. Visitors have seen and documented the iconic and expansive views of Yosemite Valley from the overlook since its opening in 1933.

The large viewpoint area ...

gives a view of the valley. El Capitan

El Capitan ( es, El Capitán; "the Captain" or "the Chief") is a vertical Rock formations in the United States, rock formation in Yosemite National Park, on the north side of Yosemite Valley, near its western end. The El Capitan Granite, granit ...

is a prominent granite cliff that looms over the valley, and is a rock climbing favorite because of its sheer size, diverse climbing routes, and year-round accessibility. Granite dome

Granite domes are domical hills composed of granite with bare rock exposed over most of the surface. Generally, domical features such as these are known as bornhardts. Bornhardts can form in any type of plutonic rock but are typically composed o ...

s such as Sentinel Dome and Half Dome

Half Dome is a granite dome at the eastern end of Yosemite Valley in Yosemite National Park, California. It is a well-known rock formation in the park, named for its distinct shape. One side is a sheer face while the other three sides are smooth ...

rise , respectively, above the valley floor. The park contains dozens of other granite domes

Granite domes are domical hills composed of granite with bare rock exposed over most of the surface. Generally, domical features such as these are known as bornhardts. Bornhardts can form in any type of plutonic rock but are typically composed o ...

.

The high country of Yosemite contains other important features such as Tuolumne Meadows, Dana Meadows, the Clark Range, the Cathedral Range, and the Kuna Crest

Kuna Crest is a mountain range near Tuolumne Meadows, in Yosemite National Park, California.

Name

The word ''Kuna'' probably derives from a Shoshonean language, Shoshonean word meaning "fire," which appears in the Mono language (California), Mo ...

. The Sierra crest and the Pacific Crest Trail run through Yosemite. Mount Dana and Mount Gibbs

Mount Gibbs is located in the Sierra Nevada of the U.S. state of California, south of Mount Dana. The mountain was named in honor of Oliver Gibbs, a professor at Harvard University and friend of Josiah Whitney. The summit marks the boundary ...

are peaks of red metamorphic rock. Granite peaks include Mount Conness

Mount Conness is a mountain in the Sierra Nevada range, to the west of the Hall Natural Area. Conness is on the boundary between the Inyo National Forest and Yosemite National Park. The Conness Glacier lies north of the summit.

History

Mount ...

, Cathedral Peak Cathedral Peak may be any of several mountains, typically those with steep sides and towers reminiscent of a cathedral. In the United States alone, the USGS identifies 17 summits named "Cathedral Peak".

In other countries:

*Cathedr ...

, and Matterhorn Peak

Matterhorn Peak is located in the Sierra Nevada (U.S.), Sierra Nevada, in California, at the northern boundary of Yosemite National Park. At elevation, it is the tallest peak in the craggy Alps-like Sawtooth Ridge and the northernmost peak in ...

. Mount Lyell is the highest point in the park, standing at . The Lyell Glacier is the largest glacier in the park and one of the few remaining in the Sierra.

The park has three groves of ancient giant sequoia ('' Sequoiadendron giganteum'') trees; the Mariposa Grove

Mariposa Grove is a sequoia grove located near Wawona, California, United States, in the southernmost part of Yosemite National Park. It is the largest grove of giant sequoias in the park, with several hundred mature examples of the tree. Two of i ...

(200 trees), the Tuolumne Grove (25 trees), and the Merced Grove

Merced Grove is a giant sequoia grove located about west of Crane Flat in the Merced River watershed of Yosemite National Park, California. The grove occupies a small valley at an elevation of and is accessible by a dirt trail.

The grove host ...

(20 trees). This species grows larger in volume than any other and is one of the tallest and longest-lived.

Water and ice

The Tuolumne and

The Tuolumne and Merced River

The Merced River (), in the central part of the U.S. state of California, is a -long tributary of the San Joaquin River flowing from the Sierra Nevada (U.S.), Sierra Nevada into the San Joaquin Valley. It is most well known for its swift and st ...

systems originate along the crest of the Sierra in the park and have carved river canyons deep. The Tuolumne River drains the entire northern portion of the park, an area of approximately . The Merced River begins in the park's southern peaks, primarily the Cathedral and Clark Ranges, and drains an area of approximately .

Hydrologic processes, including glaciation

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betw ...

, flooding, and fluvial geomorphic response, have been fundamental in creating park landforms. The park contains approximately 3,200 lakes (greater than 100 m2), two reservoirs, and of streams. Wetland

A wetland is a distinct ecosystem that is flooded or saturated by water, either permanently (for years or decades) or seasonally (for weeks or months). Flooding results in oxygen-free (anoxic) processes prevailing, especially in the soils. The ...

s flourish in valley bottoms throughout the park, and are often hydrologically linked to nearby lakes and rivers through seasonal flooding and groundwater. Meadow habitats, distributed at elevations from in the park, are generally wetlands, as are the riparian habitats found on the banks of Yosemite's watercourses.

Ribbon Fall

Ribbon Fall, located in Yosemite National Park in California, flows off a cliff on the west side of El Capitan and is the longest single-drop waterfall

A waterfall is a point in a river or stream where water flows over a vertical drop or a s ...

s, which has the highest single vertical drop, . Perhaps the most prominent of the valley waterfalls is Bridalveil Fall

Bridalveil Fall is one of the most prominent waterfalls in the Yosemite Valley in California.

The waterfall is in height and flows year round.

Geology

The glaciers that carved Yosemite Valley left many hanging valleys that spawned the waterfa ...

. Wapama Falls in Hetch Hetchy Valley is another notable waterfall. Hundreds of ephemeral

Ephemerality (from the Greek word , meaning 'lasting only one day') is the concept of things being transitory, existing only briefly. Academically, the term ephemeral constitutionally describes a diverse assortment of things and experiences, fr ...

waterfalls become active in the park after heavy rains or melting snowpack.

Park glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its Ablation#Glaciology, ablation over many years, often Century, centuries. It acquires dis ...

s are relatively small and occupy areas that are in almost permanent shade, such as north- and northeast-facing cirques

A (; from the Latin word ') is an amphitheatre-like valley formed by glacial erosion. Alternative names for this landform are corrie (from Scottish Gaelic , meaning a pot or cauldron) and (; ). A cirque may also be a similarly shaped landform ...

. Lyell Glacier is the largest glacier in Yosemite (the Palisades Glaciers are the largest in the Sierra Nevada) and covers . None of the Yosemite glaciers are a remnant of the Ice Age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages and gree ...

alpine glaciers responsible for sculpting the Yosemite landscape. Instead, they were formed during one of the neoglacial

The neoglaciation ("renewed glaciation") describes the documented cooling trend in the Earth's climate during the Holocene, following the retreat of the Wisconsin glaciation, the most recent glacial period. Neoglaciation has followed the hypsither ...

episodes that have occurred since the thawing of the Ice Age (such as the Little Ice Age

The Little Ice Age (LIA) was a period of regional cooling, particularly pronounced in the North Atlantic region. It was not a true ice age of global extent. The term was introduced into scientific literature by François E. Matthes in 1939. Ma ...

). Many Yosemite glaciers have disappeared, such as the Black Mountain Glacier that was marked in 1871 and had gone by the mid-1980s. Yosemite's final two glaciers – the Lyell and Maclure glaciers – have receded over the last 100 years and are expected to disappear as a result of climate change.

Climate

Yosemite has a

Yosemite has a Mediterranean climate

A Mediterranean climate (also called a dry summer temperate climate ''Cs'') is a temperate climate sub-type, generally characterized by warm, dry summers and mild, fairly wet winters; these weather conditions are typically experienced in the ...

(Köppen climate classification

The Köppen climate classification is one of the most widely used climate classification systems. It was first published by German-Russian climatologist Wladimir Köppen (1846–1940) in 1884, with several later modifications by Köppen, notabl ...

''Csa''), meaning most precipitation falls during the mild winter, and the other seasons are nearly dry (less than three percent of precipitation falls during the long, hot summers). Because of orographic lift, precipitation increases with elevation up to where it slowly decreases to the crest. Precipitation amounts vary from at elevation to at . Snow does not typically accumulate until November in the high country. It deepens into March or early April.

Mean daily temperatures range from to at Tuolumne Meadows at . At the Wawona Entrance (elevation ), mean daily temperature ranges from . At the lower elevations below , temperatures are hotter; the mean daily high temperature at Yosemite Valley (elevation ) varies from . At elevations above , the hot, dry summer temperatures are moderated by frequent summer thunderstorms, along with snow that can persist into July. The combination of dry vegetation, low relative humidity, and thunderstorms results in frequent lightning-caused fires as well.

At park headquarters (elevation ), January averages , while July averages . In summer the nights are much cooler than the days. An average of 45.5 days have highs of or higher and an average of 105.6 nights with freezing temperatures. Freezing temperatures have been recorded in every month of the year. The record high temperature was on July 22 and July 24, 1915, while the record low temperature was on January 1, 2009. Average annual precipitation is nearly , falling on 67 days. The wettest year was 1983 with and the driest year was 1976 with . The most precipitation in one month was in December 1955 and the most in one day was on December 23, 1955. Average annual snowfall is . The snowiest winter was 1948–1949 with . The most snow in one month was in January 1993.

Geology

Tectonic and volcanic activity

passive continental margin

A continental margin is the outer edge of continental crust abutting oceanic crust under coastal waters. It is one of the three major zones of the ocean floor, the other two being deep-ocean basins and mid-ocean ridges. The continental margin ...

during the Precambrian

The Precambrian (or Pre-Cambrian, sometimes abbreviated pꞒ, or Cryptozoic) is the earliest part of Earth's history, set before the current Phanerozoic Eon. The Precambrian is so named because it preceded the Cambrian, the first period of the ...

and early Paleozoic

The Paleozoic (or Palaeozoic) Era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The name ''Paleozoic'' ( ;) was coined by the British geologist Adam Sedgwick in 1838

by combining the Greek words ''palaiós'' (, "old") and ' ...

. Sediment was derived from continental sources and was deposited in shallow water. These rocks became deformed and metamorphosed.

Heat generated from the Farallon Plate

The Farallon Plate was an ancient oceanic plate. It formed one of the three main plates of Panthalassa, alongside the Phoenix Plate and Izanagi Plate, which were connected by a triple junction. The Farallon Plate began subducting under the west c ...

subducting below the North American Plate

The North American Plate is a tectonic plate covering most of North America, Cuba, the Bahamas, extreme northeastern Asia, and parts of Iceland and the Azores. With an area of , it is the Earth's second largest tectonic plate, behind the Pacific ...

led to the creation of an island arc of volcanoes on the west coast of proto-North America between the late Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the Silurian, million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Carboniferous, Mya. It is named after Devon, England, whe ...

and Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.9 Mya. It is the last period of the Paleoz ...

periods. Material accreted onto the western edge of North America, and mountains were raised to the east in Nevada.

The first phase of regional plutonism

Plutonism is the geologic theory that the igneous rocks forming the Earth originated from intrusive magmatic activity, with a continuing gradual process of weathering and erosion wearing away rocks, which were then deposited on the sea bed, re- ...

started 210 million years ago in the late Triassic and continued throughout the Jurassic to about 150 million years before present ( BP), which led to the creation of the Sierra Nevada Batholith

The Sierra Nevada Batholith is a large batholith which forms the core of the Sierra Nevada mountain range in California, exposed at the surface as granite.

The batholith is composed of many individual masses of rock called ''plutons'', which fo ...

. The resulting rocks were mostly granitic in composition and lay about below the surface. Around the same time, the Nevadan orogeny

The Nevadan orogeny occurred along the western margin of North America during the Middle Jurassic to Early Cretaceous time which is approximately from 155 Ma to 145 Ma. Throughout the duration of this orogeny there were at least two different kin ...

built the Nevadan mountain range (also called the Ancestral Sierra Nevada) to a height of .

The second major pluton emplacement phase lasted from about 120 million to 80 million years ago during the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of th ...

. This was part of the Sevier orogeny

The Sevier orogeny was a mountain-building event that affected western North America from northern Canada to the north to Mexico to the south.

The Sevier orogeny was the result of convergent boundary tectonic activity, and deformation occurred fr ...

.

Starting 20 million years ago (in the Cenozoic

The Cenozoic ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterised by the dominance of mammals, birds and flowering plants, a cooling and drying climate, and the current configura ...

) and lasting until 5 million years ago, a now-extinct extension of Cascade Range

The Cascade Range or Cascades is a major mountain range of western North America, extending from southern British Columbia through Washington and Oregon to Northern California. It includes both non-volcanic mountains, such as the North Cascades, ...

volcanoes erupted, bringing large amounts of igneous material in the area. These igneous deposits blanketed the region north of the Yosemite region. Volcanic activity persisted past 5 million years BP east of the current park borders in the Mono Lake and Long Valley areas.

Uplift and erosion

Starting 10 million years ago, vertical movement along the Sierra fault started to uplift the Sierra Nevada. Subsequent tilting of the Sierra block and the resulting accelerated uplift of the Sierra Nevada increased the

Starting 10 million years ago, vertical movement along the Sierra fault started to uplift the Sierra Nevada. Subsequent tilting of the Sierra block and the resulting accelerated uplift of the Sierra Nevada increased the gradient

In vector calculus, the gradient of a scalar-valued differentiable function of several variables is the vector field (or vector-valued function) \nabla f whose value at a point p is the "direction and rate of fastest increase". If the gradi ...

of western-flowing streams. The streams consequently ran faster and thus cut their valleys more quickly. Additional uplift occurred when major faults developed to the east, forming Owens Valley

Owens Valley (Numic

Numic is a branch of the Uto-Aztecan language family. It includes seven languages spoken by Native American peoples traditionally living in the Great Basin, Colorado River basin, Snake River basin, and southern Great Pl ...

from Basin and Range

Basin and range topography is characterized by alternating parallel mountain ranges and valleys. It is a result of crustal extension due to mantle upwelling, gravitational collapse, crustal thickening, or relaxation of confining stresses. The e ...

-associated extensional forces. Sierra uplift accelerated again about two million years ago during the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

.

The uplifting and increased erosion exposed granitic rocks to surface pressures, resulting in exfoliation (responsible for the rounded shape of the many domes in the park) and mass wasting following the numerous fracture joint planes (cracks; especially vertical ones) in the now solidified plutons. Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

glaciers further accelerated this process, while glacial meltwater transported the resulting talus and till from valley floors.

Numerous vertical joint planes controlled where and how fast erosion took place. Most of these long, linear and very deep cracks trend northeast or northwest and form parallel, often regularly spaced sets.

Glacial sculpting

A series of glaciations further modified the region starting about 2 to 3 million years ago and ending sometime around 10,000 BP. At least four major glaciations occurred in the Sierra, locally called the Sherwin (also called the pre-Tahoe), Tahoe, Tenaya, and Tioga. The Sherwin glaciers were the largest, filling Yosemite and other valleys, while later stages produced much smaller glaciers. A Sherwin-age glacier was almost surely responsible for the major excavation and shaping of Yosemite Valley and other canyons in the area.

Glacial systems reached depths of up to and left their marks. The longest glacier ran down the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne River for , passing well beyond Hetch Hetchy Valley. Merced Glacier flowed out of Yosemite Valley and into the Merced River Gorge. Lee Vining Glacier carved Lee Vining Canyon and emptied into Lake Russel (the much-enlarged ice age version of Mono Lake). Only the highest peaks, such as Mount Dana and Mount Conness, were not covered by glaciers. Retreating glaciers often left recessional