Tagore Gandhi.jpg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Rabindranath Tagore (; bn, রবীন্দ্রনাথ ঠাকুর; 7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941) was a

The youngest of 13 surviving children, Tagore (nicknamed "Rabi") was born on 7 May 1861 in the

The youngest of 13 surviving children, Tagore (nicknamed "Rabi") was born on 7 May 1861 in the  Tagore was raised mostly by servants; his mother had died in his early childhood and his father travelled widely. The

Tagore was raised mostly by servants; his mother had died in his early childhood and his father travelled widely. The

In 1890 Tagore began managing his vast ancestral estates in Shelaidaha (today a region of Bangladesh); he was joined there by his wife and children in 1898. Tagore released his ''Manasi'' poems (1890), among his best-known work. As ''

In 1890 Tagore began managing his vast ancestral estates in Shelaidaha (today a region of Bangladesh); he was joined there by his wife and children in 1898. Tagore released his ''Manasi'' poems (1890), among his best-known work. As ''

In 1901 Tagore moved to

In 1901 Tagore moved to

Dutta and Robinson describe this phase of Tagore's life as being one of a "peripatetic

Dutta and Robinson describe this phase of Tagore's life as being one of a "peripatetic

Between 1878 and 1932, Tagore set foot in more than thirty countries on five continents. In 1912, he took a sheaf of his translated works to England, where they gained attention from missionary and Gandhi protégé Charles F. Andrews, Irish poet

Between 1878 and 1932, Tagore set foot in more than thirty countries on five continents. In 1912, he took a sheaf of his translated works to England, where they gained attention from missionary and Gandhi protégé Charles F. Andrews, Irish poet

Tagore's experiences with drama began when he was sixteen, with his brother Jyotirindranath. He wrote his first original dramatic piece when he was twenty — '' Valmiki Pratibha'' which was shown at the Tagore's mansion. Tagore stated that his works sought to articulate "the play of feeling and not of action". In 1890 he wrote ''Visarjan'' (an adaptation of his novella ''Rajarshi''), which has been regarded as his finest drama. In the original Bengali language, such works included intricate subplots and extended monologues. Later, Tagore's dramas used more philosophical and allegorical themes. The play ''

Tagore's experiences with drama began when he was sixteen, with his brother Jyotirindranath. He wrote his first original dramatic piece when he was twenty — '' Valmiki Pratibha'' which was shown at the Tagore's mansion. Tagore stated that his works sought to articulate "the play of feeling and not of action". In 1890 he wrote ''Visarjan'' (an adaptation of his novella ''Rajarshi''), which has been regarded as his finest drama. In the original Bengali language, such works included intricate subplots and extended monologues. Later, Tagore's dramas used more philosophical and allegorical themes. The play ''

Tagore began his career in short stories in 1877—when he was only sixteen—with "Bhikharini" ("The Beggar Woman").. With this, Tagore effectively invented the Bengali-language short story genre. The four years from 1891 to 1895 are known as Tagore's "Sadhana" period (named for one of Tagore's magazines). This period was among Tagore's most fecund, yielding more than half the stories contained in the three-volume ''Galpaguchchha'', which itself is a collection of eighty-four stories. Such stories usually showcase Tagore's reflections upon his surroundings, on modern and fashionable ideas, and on interesting mind puzzles (which Tagore was fond of testing his intellect with). Tagore typically associated his earliest stories (such as those of the "''Sadhana''" period) with an exuberance of vitality and spontaneity; these characteristics were intimately connected with Tagore's life in the common villages of, among others,

Tagore began his career in short stories in 1877—when he was only sixteen—with "Bhikharini" ("The Beggar Woman").. With this, Tagore effectively invented the Bengali-language short story genre. The four years from 1891 to 1895 are known as Tagore's "Sadhana" period (named for one of Tagore's magazines). This period was among Tagore's most fecund, yielding more than half the stories contained in the three-volume ''Galpaguchchha'', which itself is a collection of eighty-four stories. Such stories usually showcase Tagore's reflections upon his surroundings, on modern and fashionable ideas, and on interesting mind puzzles (which Tagore was fond of testing his intellect with). Tagore typically associated his earliest stories (such as those of the "''Sadhana''" period) with an exuberance of vitality and spontaneity; these characteristics were intimately connected with Tagore's life in the common villages of, among others,

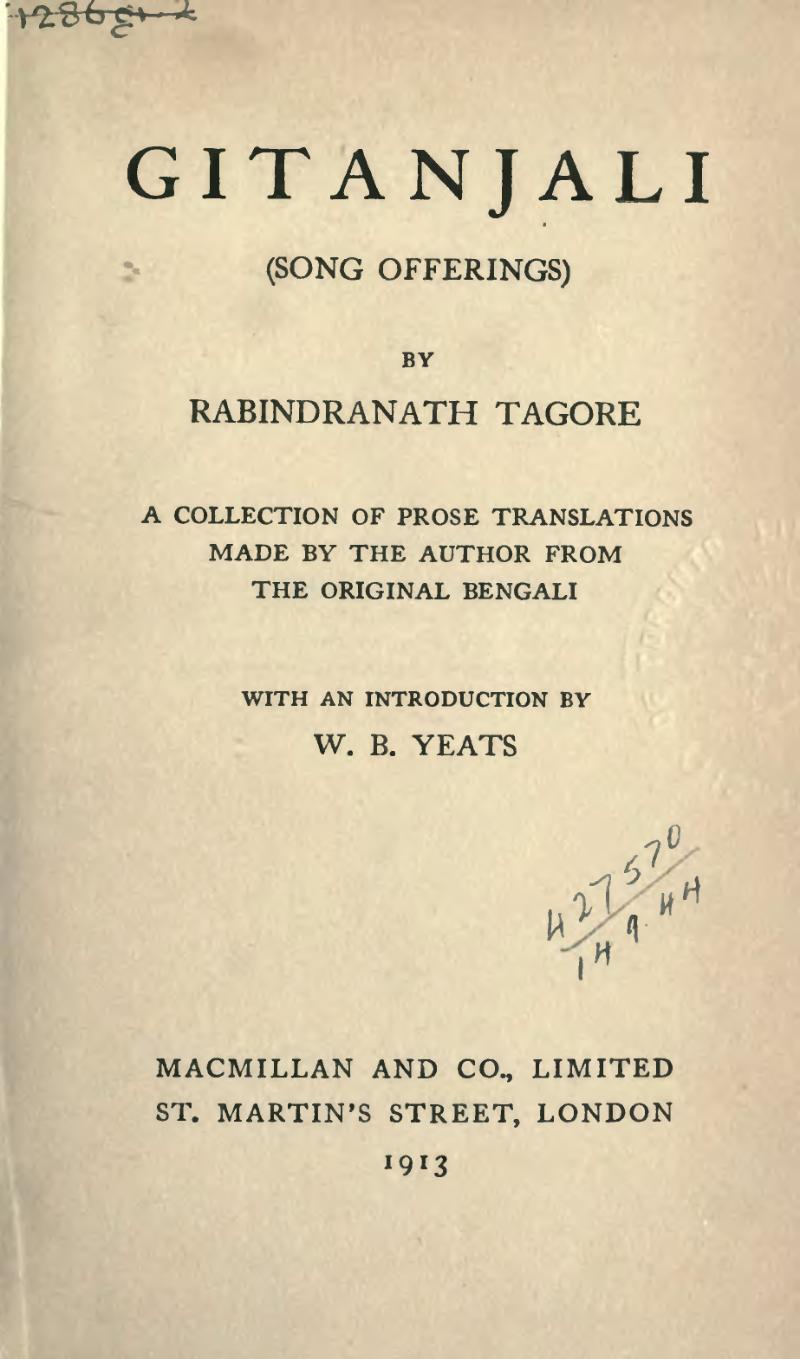

Internationally, ''Gitanjali'' ( bn, গীতাঞ্জলি) is Tagore's best-known collection of poetry, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913. Tagore was the first non-European to receive a Nobel Prize in Literature and second non-European to receive a Nobel Prize after

Internationally, ''Gitanjali'' ( bn, গীতাঞ্জলি) is Tagore's best-known collection of poetry, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913. Tagore was the first non-European to receive a Nobel Prize in Literature and second non-European to receive a Nobel Prize after

Tagore opposed imperialism and supported Indian nationalists, and these views were first revealed in ''Manast'', which was mostly composed in his twenties. Evidence produced during the

Tagore opposed imperialism and supported Indian nationalists, and these views were first revealed in ''Manast'', which was mostly composed in his twenties. Evidence produced during the

Tagore despised rote classroom schooling: in "The Parrot's Training", a bird is caged and force-fed textbook pages—to death. Visiting Santa Barbara in 1917, Tagore conceived a new type of university: he sought to "make Santiniketan the connecting thread between India and the world nda world center for the study of humanity somewhere beyond the limits of nation and geography." The school, which he named

Tagore despised rote classroom schooling: in "The Parrot's Training", a bird is caged and force-fed textbook pages—to death. Visiting Santa Barbara in 1917, Tagore conceived a new type of university: he sought to "make Santiniketan the connecting thread between India and the world nda world center for the study of humanity somewhere beyond the limits of nation and geography." The school, which he named

Every year, many events pay tribute to Tagore: ''Kabipranam'', his birth anniversary, is celebrated by groups scattered across the globe; the annual Tagore Festival held in Urbana, Illinois (USA); ''Rabindra Path Parikrama'' walking pilgrimages from Kolkata to Santiniketan; and recitals of his poetry, which are held on important anniversaries. Bengali culture is fraught with this legacy: from language and arts to history and politics. Amartya Sen deemed Tagore a "towering figure", a "deeply relevant and many-sided contemporary thinker". Tagore's Bengali originals—the 1939 ''Rabīndra Rachanāvalī''—is canonized as one of his nation's greatest cultural treasures, and he was roped into a reasonably humble role: "the greatest poet India has produced".

Every year, many events pay tribute to Tagore: ''Kabipranam'', his birth anniversary, is celebrated by groups scattered across the globe; the annual Tagore Festival held in Urbana, Illinois (USA); ''Rabindra Path Parikrama'' walking pilgrimages from Kolkata to Santiniketan; and recitals of his poetry, which are held on important anniversaries. Bengali culture is fraught with this legacy: from language and arts to history and politics. Amartya Sen deemed Tagore a "towering figure", a "deeply relevant and many-sided contemporary thinker". Tagore's Bengali originals—the 1939 ''Rabīndra Rachanāvalī''—is canonized as one of his nation's greatest cultural treasures, and he was roped into a reasonably humble role: "the greatest poet India has produced".

Tagore was renowned throughout much of Europe, North America, and East Asia. He co-founded

Tagore was renowned throughout much of Europe, North America, and East Asia. He co-founded

There are eight Tagore museums, three in India and five in Bangladesh:

* Rabindra Bharati Museum, at

There are eight Tagore museums, three in India and five in Bangladesh:

* Rabindra Bharati Museum, at

School of Wisdom

* Analyses

Ezra Pound: "Rabindranath Tagore"

''The Fortnightly Review'', March 1913

''Mary Lago Collection''

University of Missouri Audiobooks * Texts *

Bichitra: Online Tagore Variorum

* * Talks

South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Tagore, Rabindranath Writers from Kolkata Rabindranath Tagore, 1861 births 1941 deaths Presidency University, Kolkata alumni Alumni of University College London Bengali Hindus Bengali philosophers Bengali writers Bengali zamindars Brahmos Founders of Indian schools and colleges Indian Nobel laureates National anthem writers Nobel laureates in Literature People associated with Santiniketan Oriental Seminary alumni Vangiya Sahitya Parishad English-language poets from India 19th-century Bengali poets Bengali-language poets Indian Hindus Indian male dramatists and playwrights Indian male songwriters Indian male essayists 19th-century Indian painters Tagore family, Rabindranath Musicians from Kolkata 19th-century Indian educational theorists Indian portrait painters Artist authors Indian male poets 20th-century Indian painters 19th-century Indian poets 20th-century Indian poets 19th-century Indian musicians 19th-century Indian composers 20th-century Indian composers 19th-century Indian philosophers 20th-century Indian philosophers 20th-century Bengali poets Bengali male poets Indian male painters Poets from West Bengal 19th-century Indian dramatists and playwrights 20th-century Indian dramatists and playwrights 20th-century Indian essayists 19th-century Indian essayists 20th-century Indian novelists 20th-century Indian educational theorists Knights Bachelor Painters from West Bengal 19th-century male musicians Indian classical composers 19th-century classical musicians Haiku poets People associated with Shillong Indian social reformers

Bengali

Bengali or Bengalee, or Bengalese may refer to:

*something of, from, or related to Bengal, a large region in South Asia

* Bengalis, an ethnic and linguistic group of the region

* Bengali language, the language they speak

** Bengali alphabet, the w ...

polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

who worked as a poet, writer, playwright, composer, philosopher, social reformer and painter. He reshaped Bengali literature and music

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspe ...

as well as Indian art with Contextual Modernism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Author of the "profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful" poetry of ''Gitanjali

__NOTOC__

''Gitanjali'' ( bn, গীতাঞ্জলি, lit='Song offering') is a collection of poems by the Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore. Tagore received the Nobel Prize for Literature, for the English translation, Gitanjali:'' Song Off ...

'', he became in 1913 the first non-European and the first lyricist to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Tagore's poetic songs were viewed as spiritual and mercurial; however, his "elegant prose and magical poetry" remain largely unknown outside Bengal. He was a fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society

The Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, commonly known as the Royal Asiatic Society (RAS), was established, according to its royal charter of 11 August 1824, to further "the investigation of subjects connected with and for the en ...

. Referred to as "the Bard of Bengal", Tagore was known by sobriquets

A sobriquet ( ), or soubriquet, is a nickname, sometimes assumed, but often given by another, that is descriptive. A sobriquet is distinct from a pseudonym, as it is typically a familiar name used in place of a real name, without the need of expla ...

: Gurudev, Kobiguru, Biswakobi.

A Bengali Brahmin

The Bengali Brahmins are Hindu Brahmins who traditionally reside in the Bengal region of the Indian subcontinent, currently comprising the Indian state of West Bengal and the country of Bangladesh.

The Bengali Brahmins, along with Baidyas an ...

from Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, the official name until 2001) is the Capital city, capital of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal, on the eastern ba ...

with ancestral gentry

Gentry (from Old French ''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest c ...

roots in Burdwan district*

*

* and Jessore

Jessore ( bn, যশোর, jôshor, ), officially Jashore, is a city of Jessore District situated in Khulna Division. It is situated in the south-western part of Bangladesh. It is the administrative centre (headquarter) of the eponymous district ...

, Tagore wrote poetry as an eight-year-old. At the age of sixteen, he released his first substantial poems under the pseudonym ''Bhānusiṃha'' ("Sun Lion"), which were seized upon by literary authorities as long-lost classics. By 1877 he graduated to his first short stories and dramas, published under his real name. As a humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

, universalist, internationalist

Internationalist may refer to:

* Internationalism (politics), a movement to increase cooperation across national borders

* Liberal internationalism, a doctrine in international relations

* Internationalist/Defencist Schism, socialists opposed to ...

, and ardent critic of nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

, he denounced the British Raj

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was him ...

and advocated independence from Britain. As an exponent of the Bengal Renaissance

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

, he advanced a vast canon that comprised paintings, sketches and doodles, hundreds of texts, and some two thousand songs; his legacy also endures in his founding of Visva-Bharati University

Visva-Bharati () is a public central university and an Institution of National Importance located in Shantiniketan, West Bengal, India. It was founded by Rabindranath Tagore who called it ''Visva-Bharati'', which means the communion of the ...

.

Tagore modernised Bengali art by spurning rigid classical forms and resisting linguistic strictures. His novels, stories, songs, dance-dramas, and essays spoke to topics political and personal. ''Gitanjali

__NOTOC__

''Gitanjali'' ( bn, গীতাঞ্জলি, lit='Song offering') is a collection of poems by the Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore. Tagore received the Nobel Prize for Literature, for the English translation, Gitanjali:'' Song Off ...

'' (''Song Offerings''), '' Gora'' (''Fair-Faced'') and ''Ghare-Baire'' ('' The Home and the World'') are his best-known works, and his verse, short stories, and novels were acclaimed—or panned—for their lyricism, colloquialism, naturalism, and unnatural contemplation. His compositions were chosen by two nations as national anthems: India's "Jana Gana Mana

"" (Sanskrit: जन गण मन) is the national anthem of the Republic of India. It was originally composed as '' Bharoto Bhagyo Bidhata'' in Bengali by polymath Rabindranath Tagore. The first stanza of the song ''Bharoto Bhagyo Bidhata' ...

" and Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mos ...

's " Amar Shonar Bangla". The Sri Lankan national anthem was inspired by his work.*

*

*

Family history

The name Tagore is the anglicised transliteration of Thakur. The original surname of the Tagores was Kushari. They werePirali Brahmin

The Bengali Brahmins are Hindu Brahmins who traditionally reside in the Bengal region of the Indian subcontinent, currently comprising the Indian state of West Bengal and the country of Bangladesh.

The Bengali Brahmins, along with Baidyas a ...

('Pirali’ historically carried a stigmatized and pejorative connotation) originally belonged to a village named ''Kush'' in the district named Burdwan

Bardhaman (, ) is a city and a municipality in the state of West Bengal, India. It is the headquarters of Purba Bardhaman district, having become a district capital during the period of British rule. Burdwan, an alternative name for the city, ...

in West Bengal

West Bengal (, Bengali: ''Poshchim Bongo'', , abbr. WB) is a state in the eastern portion of India. It is situated along the Bay of Bengal, along with a population of over 91 million inhabitants within an area of . West Bengal is the fou ...

. The biographer of Rabindranath Tagore, Prabhat Kumar Mukhopadhyaya wrote in the first volume of his book ''Rabindrajibani O Rabindra Sahitya Prabeshak'' that

Life and events

Early life: 1861–1878

The youngest of 13 surviving children, Tagore (nicknamed "Rabi") was born on 7 May 1861 in the

The youngest of 13 surviving children, Tagore (nicknamed "Rabi") was born on 7 May 1861 in the Jorasanko mansion

Jorasanko Thakur Bari (Bengali language, Bengali: ''House of the Thakur (Indian title), Thakurs''; anglicised to ''Tagore'') in Jorasanko, North Kolkata, West Bengal, India, is the ancestral home of the Tagore family. It is the birthplace of po ...

in Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, the official name until 2001) is the Capital city, capital of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal, on the eastern ba ...

, the son of Debendranath Tagore

Debendranath Tagore (15 May 1817 – 19 January 1905) was an Indian Hindu philosopher and religious reformer, active in the Brahmo Samaj (earlier called Bhramho Sabha) ("Society of Brahma", also translated as ''Society of God''). He joined Brahm ...

(1817–1905) and Sarada Devi (1830–1875).

Tagore was raised mostly by servants; his mother had died in his early childhood and his father travelled widely. The

Tagore was raised mostly by servants; his mother had died in his early childhood and his father travelled widely. The Tagore family

The Tagore family (also spelled as ''Thakur''), with over three hundred years of history,Deb, Chitra, pp 64–65. has been one of the leading families of Calcutta, India, and is regarded as one of the key influencers during the Bengali Renaissa ...

was at the forefront of the Bengal renaissance

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

. They hosted the publication of literary magazines; theatre and recitals of Bengali and Western classical music featured there regularly. Tagore's father invited several professional Dhrupad

Dhrupad is a genre in Hindustani classical music from the Indian subcontinent. It is the oldest known style of major vocal styles associated with Hindustani classical music, Haveli Sangeet of Pushtimarg Sampraday and also related to the South In ...

musicians to stay in the house and teach Indian classical music to the children. Tagore's oldest brother Dwijendranath was a philosopher and poet. Another brother, Satyendranath, was the first Indian appointed to the elite and formerly all-European Indian Civil Service

The Indian Civil Service (ICS), officially known as the Imperial Civil Service, was the higher civil service of the British Empire in India during British rule in the period between 1858 and 1947.

Its members ruled over more than 300 million p ...

. Yet another brother, Jyotirindranath, was a musician, composer, and playwright. His sister Swarnakumari became a novelist. Jyotirindranath's wife Kadambari Devi

Kadambari Devi (5 July 1859 – 21 April 1884) was the wife of Jyotirindranath Tagore and daughter-in-law of Debendranath Tagore. She was ten years younger than her husband, whom she married on 5 July 1868 (২৫শে আষাঢ়, ১২� ...

, slightly older than Tagore, was a dear friend and powerful influence. Her abrupt suicide in 1884, soon after he married, left him profoundly distraught for years.

Tagore largely avoided classroom schooling and preferred to roam the manor or nearby Bolpur

Bolpur is a city and a municipality in Birbhum district in the state of West Bengal, India. It is the headquarters of the Bolpur subdivision. Bolpur municipal area includes Santiniketan, Sriniketan and Prantik. The city is known as a Cultural ...

and Panihati, which the family visited. His brother Hemendranath tutored and physically conditioned him—by having him swim the Ganges or trek through hills, by gymnastics, and by practising judo and wrestling. He learned drawing, anatomy, geography and history, literature, mathematics, Sanskrit, and English—his least favourite subject. Tagore loathed formal education—his scholarly travails at the local Presidency College spanned a single day. Years later he held that proper teaching does not explain things; proper teaching stokes curiosity:

After his ''upanayan

''Upanayana'' ( sa, उपनयनम्, lit=initiation, translit=Upanāyanam) is a Hindu educational sacrament, one of the traditional saṃskāras or rites of passage that marked the acceptance of a student by a preceptor, such as a ''guru'' ...

'' (coming-of-age rite) at age eleven, Tagore and his father left Calcutta in February 1873 to tour India for several months, visiting his father's Santiniketan

Santiniketan is a neighbourhood of Bolpur town in the Bolpur subdivision of Birbhum district in West Bengal, India, approximately 152 km north of Kolkata. It was established by Maharshi Devendranath Tagore, and later expanded by his son ...

estate and Amritsar before reaching the Himalayan hill station of Dalhousie. There Tagore read biographies, studied history, astronomy, modern science, and Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

, and examined the classical poetry of Kālidāsa.. During his 1-month stay at Amritsar in 1873 he was greatly influenced by melodious gurbani

Gurbani ( pa, ਗੁਰਬਾਣੀ) is a Sikh term, very commonly used by Sikhs to refer to various compositions by the Sikh Gurus and other writers of Guru Granth Sahib. In general, hymns in the central text of the Sikhs, the Guru Granth Sahi ...

and nanak bani

Gurū Nānak (15 April 1469 – 22 September 1539; Gurmukhi: ਗੁਰੂ ਨਾਨਕ; pronunciation: , ), also referred to as ('father Nānak'), was the founder of Sikhism and is the first of the ten Sikh Gurus. His birth is celebrated wor ...

being sung at Golden Temple for which both father and son were regular visitors. He mentions about this in his ''My Reminiscences'' (1912) He wrote 6 poems relating to Sikhism and a number of articles in Bengali children's magazine about Sikhism. Tagore returned to Jorosanko and completed a set of major works by 1877, one of them a long poem in the Maithili style of Vidyapati

Vidyapati ( – 1460), also known by the sobriquet ''Maithil Kavi Kokil'' (the poet cuckoo of Maithili), was a Maithili and Sanskrit polymath-poet-saint, playwright, composer, biographer, philosopher, law-theorist, writer, courtier ...

. As a joke, he claimed that these were the lost works of newly discovered 17th-century Vaiṣṇava poet Bhānusiṃha.. Regional experts accepted them as the lost works of the fictitious poet. He debuted in the short-story genre in Bengali with "Bhikharini

"Bhikharini" (English: The Beggar Woman) is a Bengali short story written by Rabindranath Tagore. The story was first published in 1877 in ''Bharati'' and was the first short story written in Bengali language. This was also Tagore's own first short ...

" ("The Beggar Woman"). Published in the same year, ''Sandhya Sangit'' (1882) includes the poem "Nirjharer Swapnabhanga" ("The Rousing of the Waterfall").

Shelaidaha: 1878–1901

Because Debendranath wanted his son to become a barrister, Tagore enrolled at a public school in Brighton, East Sussex, England in 1878. He stayed for several months at a house that the Tagore family owned near Brighton andHove

Hove is a seaside resort and one of the two main parts of the city of Brighton and Hove, along with Brighton in East Sussex, England. Originally a "small but ancient fishing village" surrounded by open farmland, it grew rapidly in the 19th c ...

, in Medina Villas; in 1877 his nephew and niece—Suren and Indira Devi

Indira Devi, born as Indira Raje (19 February 1892 – 6 September 1968), was the Maharani of the princely state of Cooch Behar, British India. She was the daughter of Chimnabai II. She broke her arranged engagement to marry Jitendra Narayan ...

, the children of Tagore's brother Satyendranath—were sent together with their mother, Tagore's sister-in-law, to live with him. He briefly read law at University College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = ...

, but again left school, opting instead for independent study of Shakespeare's plays

Shakespeare's plays are a canon of approximately 39 dramatic works written by English poet, playwright, and actor William Shakespeare. The exact number of plays—as well as their classifications as tragedy, history, comedy, or otherwise—is a ...

''Coriolanus

''Coriolanus'' ( or ) is a tragedy by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1605 and 1608. The play is based on the life of the legendary Roman leader Caius Marcius Coriolanus. Shakespeare worked on it during the same yea ...

'', and '' Antony and Cleopatra and the Religio Medici

''Religio Medici'' (''The Religion of a Doctor'') by Sir Thomas Browne is a spiritual testament and early psychological self-portrait. Published in 1643 after an unauthorized version was distributed the previous year, it became a European best-s ...

of Thomas Browne.'' Lively English, Irish, and Scottish folk tunes impressed Tagore, whose own tradition of Nidhubabu-authored ''kirtans

Kirtana ( sa, कीर्तन; ), also rendered as Kirtan, is a Sanskrit word that means "narrating, reciting, telling, describing" of an idea or story, specifically in Indian religions. It also refers to a genre of religious performance art ...

'' and ''tappa Tappa is a form of Indian semi-classical vocal music. Its specialty is a rolling pace based on fast, subtle and knotty construction. Its tunes are melodious and sweet, and depict the emotional outbursts of a lover. Tappe (plural) were sung mostly by ...

s'' and Brahmo

Bengali Brahmos are those who adhere to Brahmoism, the philosophy of Brahmo Samaj which was founded by Raja Rammohan Roy. A recent publication describes the disproportionate influence of Brahmos on India's development post-19th Century as unpa ...

hymnody was subdued. In 1880 he returned to Bengal degree-less, resolving to reconcile European novelty with Brahmo traditions, taking the best from each. After returning to Bengal, Tagore regularly published poems, stories, and novels. These had a profound impact within Bengal itself but received little national attention. In 1883 he married 10-year-old Mrinalini Devi

Mrinalini Devi (1 March 1874 – 23 November 1902) was a translator and the wife of Nobel laureate poet, philosopher, author and musician Rabindranath Tagore. She was from the Jessor district, where her father worked at the Tagore estate. In ...

, born Bhabatarini, 1873–1902 (this was a common practice at the time). They had five children, two of whom died in childhood.

In 1890 Tagore began managing his vast ancestral estates in Shelaidaha (today a region of Bangladesh); he was joined there by his wife and children in 1898. Tagore released his ''Manasi'' poems (1890), among his best-known work. As ''

In 1890 Tagore began managing his vast ancestral estates in Shelaidaha (today a region of Bangladesh); he was joined there by his wife and children in 1898. Tagore released his ''Manasi'' poems (1890), among his best-known work. As ''Zamindar

A zamindar ( Hindustani: Devanagari: , ; Persian: , ) in the Indian subcontinent was an autonomous or semiautonomous ruler of a province. The term itself came into use during the reign of Mughals and later the British had begun using it as ...

Babu'', Tagore criss-crossed the Padma River

The Padma ( bn, পদ্মা ''Pôdma'') is a major river in Bangladesh. It is the main distributary of the Ganges, flowing generally southeast for to its confluence with the Meghna River near the Bay of Bengal. The city of Rajshahi is sit ...

in command of the ''Padma'', the luxurious family barge (also known as " budgerow"). He collected mostly token rents and blessed villagers who in turn honoured him with banquets—occasionally of dried rice and sour milk. He met Gagan Harkara

Gaganchandra Dam ( bn, গগনচন্দ্র দাম; 1845–1910), mostly known as Gagan Harkara ( bn, গগন হরকরা), was a Bengali Baul poet after the tune of whose famous song " Ami Kothay Pabo Tare" (কোথায় � ...

, through whom he became familiar with Baul

The Baul ( bn, বাউল) are a group of mystic minstrels of mixed elements of Sufism, Vaishnavism and Tantra from Bangladesh and the neighboring Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura and Assam's Barak Valley and Meghalaya. Bauls cons ...

Lalon Shah, whose folk songs greatly influenced Tagore. Tagore worked to popularise Lalon's songs. The period 1891–1895, Tagore's ''Sadhana'' period, named after one of his magazines, was his most productive; in these years he wrote more than half the stories of the three-volume, 84-story ''Galpaguchchha''. Its ironic and grave tales examined the voluptuous poverty of an idealised rural Bengal.

Santiniketan: 1901–1932

In 1901 Tagore moved to

In 1901 Tagore moved to Santiniketan

Santiniketan is a neighbourhood of Bolpur town in the Bolpur subdivision of Birbhum district in West Bengal, India, approximately 152 km north of Kolkata. It was established by Maharshi Devendranath Tagore, and later expanded by his son ...

to found an ashram with a marble-floored prayer hall—''The Mandir''—an experimental school, groves of trees, gardens, a library. There his wife and two of his children died. His father died in 1905. He received monthly payments as part of his inheritance and income from the Maharaja of Tripura

Tripura (, Bengali: ) is a state in Northeast India. The third-smallest state in the country, it covers ; and the seventh-least populous state with a population of 36.71 lakh ( 3.67 million). It is bordered by Assam and Mizoram to the ea ...

, sales of his family's jewellery, his seaside bungalow in Puri

Puri () is a coastal city and a municipality in the state of Odisha in eastern India. It is the district headquarters of Puri district and is situated on the Bay of Bengal, south of the state capital of Bhubaneswar. It is also known as '' ...

, and a derisory 2,000 rupees in book royalties. He gained Bengali and foreign readers alike; he published ''Naivedya

200px, Prasad thaal offered to Swaminarayan temple in Ahmedabad ">Shri Swaminarayan Mandir, Ahmedabad">Swaminarayan temple in Ahmedabad

Prasada (, Sanskrit: प्रसाद, ), Prasadam or Prasad is a religious offering in Hinduism. Most o ...

'' (1901) and ''Kheya'' (1906) and translated poems into free verse.

In 1912, Tagore translated his 1910 work ''Gitanjali

__NOTOC__

''Gitanjali'' ( bn, গীতাঞ্জলি, lit='Song offering') is a collection of poems by the Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore. Tagore received the Nobel Prize for Literature, for the English translation, Gitanjali:'' Song Off ...

'' into English. While on a trip to London, he shared these poems with admirers including William Butler Yeats

William Butler Yeats (13 June 186528 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival and became a pillar of the Irish liter ...

and Ezra Pound. London's India Society The Royal India Society was a 20th-century British learned society concerned with India.

The Society has had several names: the India Society (founded 1910); the Royal India Society (from 1944); the Royal India and Pakistan Society; the Royal Indi ...

published the work in a limited edition, and the American magazine ''Poetry

Poetry (derived from the Greek ''poiesis'', "making"), also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings i ...

'' published a selection from ''Gitanjali''. In November 1913, Tagore learned he had won that year's Nobel Prize in Literature: the Swedish Academy appreciated the idealistic—and for Westerners—accessible nature of a small body of his translated material focused on the 1912 ''Gitanjali: Song Offerings''. He was awarded a knighthood by King George V in the 1915 Birthday Honours

The 1915 Birthday Honours were appointments by King George V to various orders and honours to reward and highlight good works by citizens of the British Empire. The appointments were made to celebrate the official birthday of The King, and were ...

, but Tagore renounced it after the 1919 Jallianwala Bagh massacre

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre, also known as the Amritsar massacre, took place on 13 April 1919. A large peaceful crowd had gathered at the Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar, Punjab, to protest against the Rowlatt Act and arrest of pro-independenc ...

. Renouncing the knighthood, Tagore wrote in a letter addressed to Lord Chelmsford, the then British Viceroy of India, "The disproportionate severity of the punishments inflicted upon the unfortunate people and the methods of carrying them out, we are convinced, are without parallel in the history of civilised governments...The time has come when badges of honour make our shame glaring in their incongruous context of humiliation, and I for my part wish to stand, shorn of all special distinctions, by the side of my country men."

In 1919, he was invited by the president and chairman of Anjuman-e-Islamia, Syed Abdul Majid

The Hon'ble Moulvi Khan Bahadur Syed Abdul Majid, CIE ( bn, সৈয়দ আব্দুল মজিদ; 1872–1922), also known by his daak naam Kaptan Miah ( bn, কাপ্তান মিঞা), was a Bengali politician, lawyer and ...

to visit Sylhet for the first time. The event attracted over 5000 people.

In 1921, Tagore and agricultural economist Leonard Elmhirst set up the "Institute for Rural Reconstruction", later renamed Shriniketan or "Abode of Welfare", in Surul, a village near the ''ashram''. With it, Tagore sought to moderate Gandhi's '' Swaraj'' protests, which he occasionally blamed for British India's perceived mental – and thus ultimately colonial – decline. He sought aid from donors, officials, and scholars worldwide to "free village from the shackles of helplessness and ignorance" by "vitalis ngknowledge". In the early 1930s he targeted ambient "abnormal caste consciousness" and untouchability

Untouchability is a form of social institution that legitimises and enforces practices that are discriminatory, humiliating, exclusionary and exploitative against people belonging to certain social groups. Although comparable forms of discrimin ...

. He lectured against these, he penned Dalit

Dalit (from sa, दलित, dalita meaning "broken/scattered"), also previously known as untouchable, is the lowest stratum of the castes in India. Dalits were excluded from the four-fold varna system of Hinduism and were seen as forming ...

heroes for his poems and his dramas, and he campaigned—successfully—to open Guruvayoor Temple

Guruvayur Temple is a Hindu temple dedicated to Guruvayurappan, a form of Vishnu, located in the town of Guruvayur in Kerala, India. It is one of the most important places of worship for Hindus in Kerala and Tamil Nadu and is often referred ...

to Dalits.

Twilight years: 1932–1941

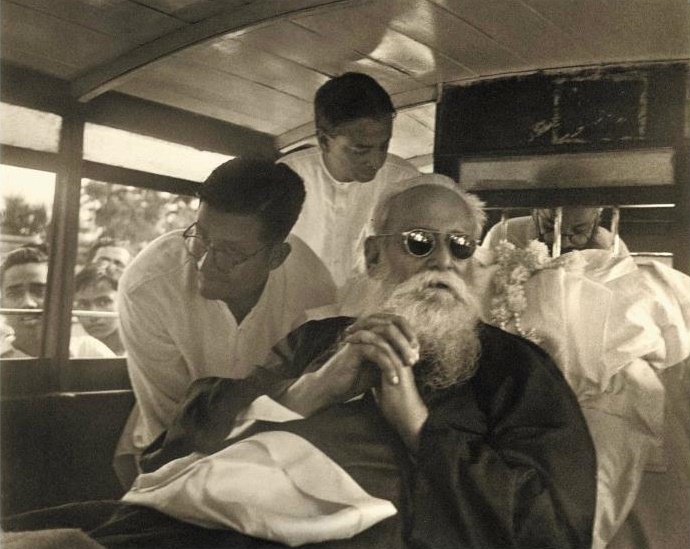

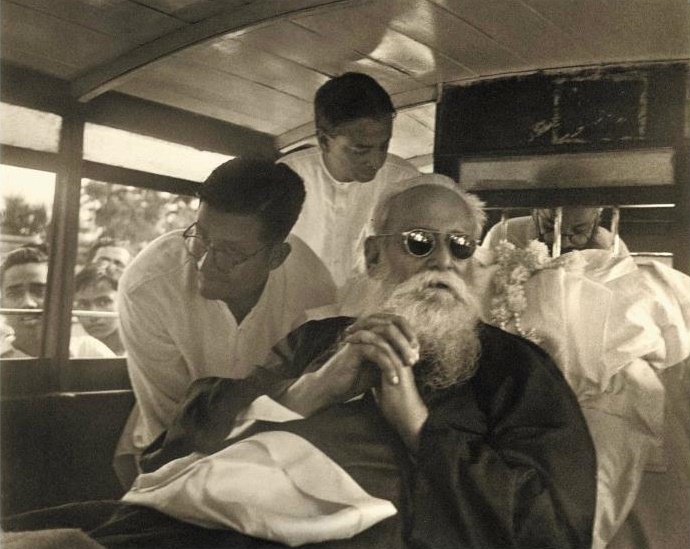

Dutta and Robinson describe this phase of Tagore's life as being one of a "peripatetic

Dutta and Robinson describe this phase of Tagore's life as being one of a "peripatetic litterateur

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the reality of society, and who proposes solutions for the normative problems of society. Coming from the world of culture, either as a creator or as ...

". It affirmed his opinion that human divisions were shallow. During a May 1932 visit to a Bedouin encampment in the Iraqi desert, the tribal chief told him that "Our Prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the s ...

has said that a true Muslim is he by whose words and deeds not the least of his brother-men may ever come to any harm ..." Tagore confided in his diary: "I was startled into recognizing in his words the voice of essential humanity." To the end Tagore scrutinized orthodoxy—and in 1934, he struck. That year, an earthquake hit Bihar and killed thousands. Gandhi hailed it as seismic ''karma

Karma (; sa, कर्म}, ; pi, kamma, italic=yes) in Sanskrit means an action, work, or deed, and its effect or consequences. In Indian religions, the term more specifically refers to a principle of cause and effect, often descriptivel ...

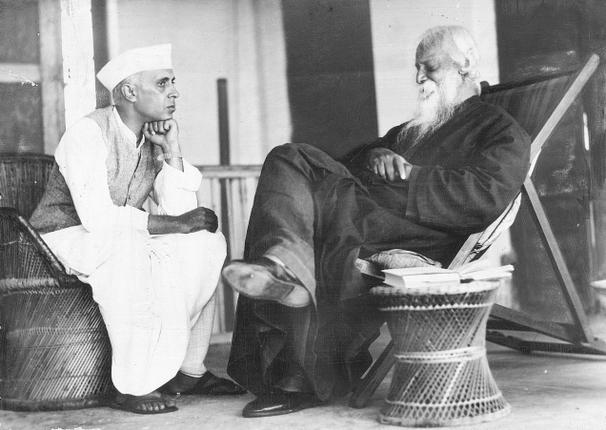

'', as divine retribution avenging the oppression of Dalits. Tagore rebuked him for his seemingly ignominious implications. He mourned the perennial poverty of Calcutta and the socioeconomic decline of Bengal and detailed this newly plebeian aesthetics in an unrhymed hundred-line poem whose technique of searing double-vision foreshadowed Satyajit Ray's film '' Apur Sansar''. Fifteen new volumes appeared, among them prose-poem works ''Punashcha'' (1932), ''Shes Saptak'' (1935), and ''Patraput'' (1936). Experimentation continued in his prose-songs and dance-dramas— '' Chitra'' (1914), ''Shyama'' (1939), and ''Chandalika'' (1938)— and in his novels— ''Dui Bon'' (1933), ''Malancha'' (1934), and ''Char Adhyay'' (1934).

Tagore's remit expanded to science in his last years, as hinted in ''Visva-Parichay'', a 1937 collection of essays. His respect for scientific laws and his exploration of biology, physics, and astronomy informed his poetry, which exhibited extensive naturalism and verisimilitude. He wove the ''process'' of science, the narratives of scientists, into stories in ''Se'' (1937), ''Tin Sangi'' (1940), and ''Galpasalpa'' (1941). His last five years were marked by chronic pain and two long periods of illness. These began when Tagore lost consciousness in late 1937; he remained comatose and near death for a time. This was followed in late 1940 by a similar spell, from which he never recovered. Poetry from these valetudinary years is among his finest. A period of prolonged agony ended with Tagore's death on 7 August 1941, aged 80. He was in an upstairs room of the Jorasanko mansion in which he grew up. The date is still mourned. A. K. Sen, brother of the first chief election commissioner, received dictation from Tagore on 30 July 1941, a day prior to a scheduled operation: his last poem.

Travels

Between 1878 and 1932, Tagore set foot in more than thirty countries on five continents. In 1912, he took a sheaf of his translated works to England, where they gained attention from missionary and Gandhi protégé Charles F. Andrews, Irish poet

Between 1878 and 1932, Tagore set foot in more than thirty countries on five continents. In 1912, he took a sheaf of his translated works to England, where they gained attention from missionary and Gandhi protégé Charles F. Andrews, Irish poet William Butler Yeats

William Butler Yeats (13 June 186528 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival and became a pillar of the Irish liter ...

, Ezra Pound, Robert Bridges

Robert Seymour Bridges (23 October 1844 – 21 April 1930) was an English poet who was Poet Laureate from 1913 to 1930. A doctor by training, he achieved literary fame only late in life. His poems reflect a deep Christian faith, and he is ...

, Ernest Rhys

Ernest Percival Rhys ( ; 17 July 1859 – 25 May 1946) was a Welsh-English writer, best known for his role as founding editor of the Everyman's Library series of affordable classics. He wrote essays, stories, poetry, novels and plays.

Early life

...

, Thomas Sturge Moore, and others. Yeats wrote the preface to the English translation of ''Gitanjali''; Andrews joined Tagore at Santiniketan. In November 1912 Tagore began touring the United States and the United Kingdom, staying in Butterton, Staffordshire with Andrews's clergymen friends. From May 1916 until April 1917, he lectured in Japan and the United States. He denounced nationalism. His essay "Nationalism in India" was scorned and praised; it was admired by Romain Rolland

Romain Rolland (; 29 January 1866 – 30 December 1944) was a French dramatist, novelist, essayist, art historian and mystic who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1915 "as a tribute to the lofty idealism of his literary production a ...

and other pacifists.

Shortly after returning home the 63-year-old Tagore accepted an invitation from the Peruvian government. He travelled to Mexico. Each government pledged 100,000 to his school to commemorate the visits. A week after his 6 November 1924 arrival in Buenos Aires, an ill Tagore shifted to the Villa Miralrío at the behest of Victoria Ocampo

Ramona Victoria Epifanía Rufina Ocampo (7 April 1890 – 27 January 1979) was an Argentine writer and intellectual. Best known as an advocate for others and as publisher of the literary magazine '' Sur'', she was also a writer and critic in he ...

. He left for home in January 1925. In May 1926 Tagore reached Naples; the next day he met Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

in Rome. Their warm rapport ended when Tagore pronounced upon ''Il Duce''s fascist finesse. He had earlier enthused: " ithout any doubt he is a great personality. There is such a massive vigor in that head that it reminds one of Michael Angelo's chisel." A "fire-bath" of fascism was to have educed "the immortal soul of Italy ... clothed in quenchless light".

On 1 November 1926 Tagore arrived at Hungary and spent some time on the shore of Lake Balaton in the city of Balatonfüred, recovering from heart problems at a sanitarium. He planted a tree, and a bust statue was placed there in 1956 (a gift from the Indian government, the work of Rasithan Kashar, replaced by a newly gifted statue in 2005) and the lakeside promenade still bears his name since 1957.

On 14 July 1927 Tagore and two companions began a four-month tour of Southeast Asia. They visited Bali, Java, Kuala Lumpur, Malacca, Penang, Siam, and Singapore. The resultant travelogues compose ''Jatri'' (1929). In early 1930 he left Bengal for a nearly year-long tour of Europe and the United States. Upon returning to Britain—and as his paintings were exhibited in Paris and London—he lodged at a Birmingham Quaker settlement. He wrote his Oxford Hibbert Lectures The Hibbert Lectures are an annual series of non-sectarian lectures on theological issues. They are sponsored by the Hibbert Trust, which was founded in 1847 by the Unitarian Robert Hibbert with a goal to uphold "the unfettered exercise of privat ...

and spoke at the annual London Quaker meet. There, addressing relations between the British and the Indians – a topic he would tackle repeatedly over the next two years – Tagore spoke of a "dark chasm of aloofness". He visited Aga Khan III

Sultan Muhammad Shah (2 November 187711 July 1957), commonly known by his religious title Aga Khan III, was the 48th Imam of the Nizariyya. He played an important role in British Indian politics.

Born to Aga Khan II in Karachi, Aga Khan II ...

, stayed at Dartington Hall

Dartington Hall in Dartington, near Totnes, Devon, England, is an historic house and country estate of dating from medieval times. The group of late 14th century buildings are Grade I listed; described in Pevsner's Buildings of England as "on ...

, toured Denmark, Switzerland, and Germany from June to mid-September 1930, then went on into the Soviet Union. In April 1932 Tagore, intrigued by the Persian mystic Hafez

Khwāje Shams-od-Dīn Moḥammad Ḥāfeẓ-e Shīrāzī ( fa, خواجه شمسالدین محمّد حافظ شیرازی), known by his pen name Hafez (, ''Ḥāfeẓ'', 'the memorizer; the (safe) keeper'; 1325–1390) and as "Hafiz", ...

, was hosted by Reza Shah Pahlavi

,

, spouse = Maryam Savadkoohi Tadj ol-Molouk Ayromlu (queen consort)Turan AmirsoleimaniEsmat Dowlatshahi

, issue = Princess Hamdamsaltaneh Princess ShamsMohammad Reza Shah Princess Ashraf Prince Ali Reza Prince Gholam Reza Prin ...

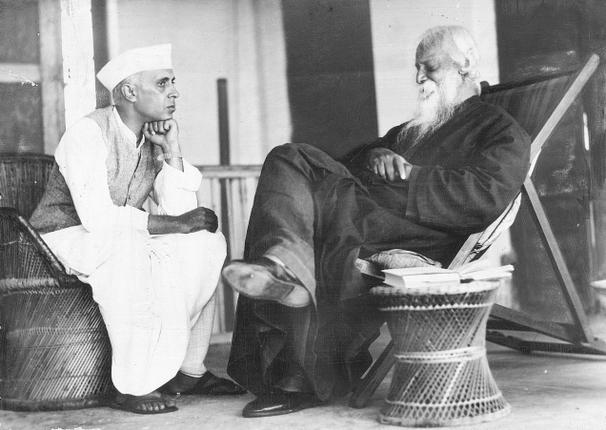

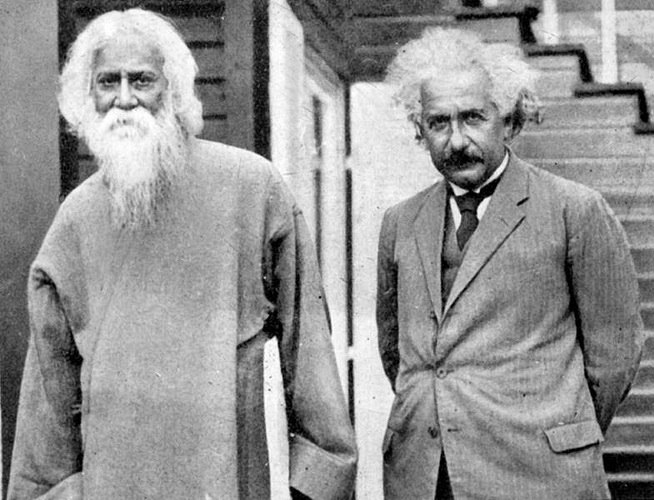

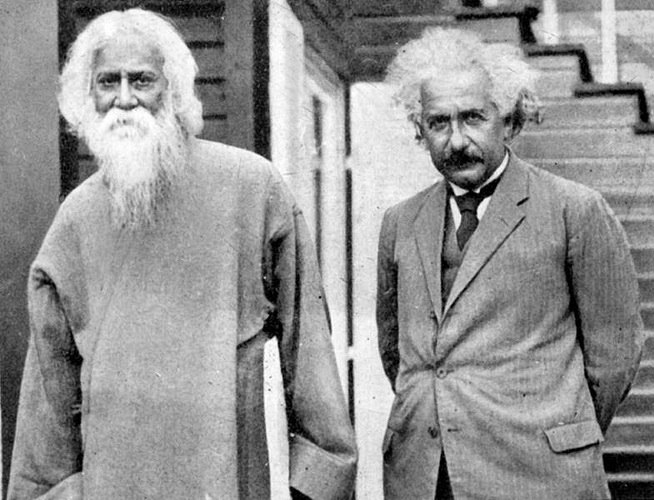

. In his other travels, Tagore interacted with Henri Bergson, Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

, Robert Frost, Thomas Mann

Paul Thomas Mann ( , ; ; 6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. His highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novell ...

, George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

, H.G. Wells, and Romain Rolland

Romain Rolland (; 29 January 1866 – 30 December 1944) was a French dramatist, novelist, essayist, art historian and mystic who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1915 "as a tribute to the lofty idealism of his literary production a ...

. Visits to Persia and Iraq (in 1932) and Sri Lanka (in 1933) composed Tagore's final foreign tour, and his dislike of communalism

Communalism may refer to:

* Communalism (Bookchin), a theory of government in which autonomous communities form confederations

* , a historical method that follows the development of communities

* Communalism (South Asia), violence across ethnic ...

and nationalism only deepened.

Vice-president of India M. Hamid Ansari

Hamid refers to two different but related Arabic given names, both of which come from the Arabic triconsonantal root of Ḥ-M-D (ِِح-م-د):

# (Arabic: حَامِد ''ḥāmid'') also spelled Haamed, Hamid or Hamed, and in Turkish Hamit; i ...

has said that Rabindranath Tagore heralded the cultural rapprochement between communities, societies and nations much before it became the liberal norm of conduct. Tagore was a man ahead of his time. He wrote in 1932, while on a visit to Iran, that "each country of Asia will solve its own historical problems according to its strength, nature and needs, but the lamp they will each carry on their path to progress will converge to illuminate the common ray of knowledge."

Works

Known mostly for his poetry, Tagore wrote novels, essays, short stories, travelogues, dramas, and thousands of songs. Of Tagore's prose, his short stories are perhaps most highly regarded; he is indeed credited with originating the Bengali-language version of the genre. His works are frequently noted for their rhythmic, optimistic, and lyrical nature. Such stories mostly borrow from the lives of common people. Tagore's non-fiction grappled with history, linguistics, and spirituality. He wrote autobiographies. His travelogues, essays, and lectures were compiled into several volumes, including ''Europe Jatrir Patro'' (''Letters from Europe'') and ''Manusher Dhormo'' (''The Religion of Man

''The Religion of Man'' is a 1931 compilation of lectures by Rabindranath Tagore, edited by him and drawn largely from his Hibbert Lectures given at Oxford University in May 1930.''The Religion of Man'', preface by Rabindranath Tagore A Brahmo p ...

''). His brief chat with Einstein, "Note on the Nature of Reality", is included as an appendix to the latter. On the occasion of Tagore's 150th birthday, an anthology (titled ''Kalanukromik Rabindra Rachanabali'') of the total body of his works is currently being published in Bengali in chronological order. This includes all versions of each work and fills about eighty volumes. In 2011, Harvard University Press

Harvard University Press (HUP) is a publishing house established on January 13, 1913, as a division of Harvard University, and focused on academic publishing. It is a member of the Association of American University Presses. After the retir ...

collaborated with Visva-Bharati University

Visva-Bharati () is a public central university and an Institution of National Importance located in Shantiniketan, West Bengal, India. It was founded by Rabindranath Tagore who called it ''Visva-Bharati'', which means the communion of the ...

to publish ''The Essential Tagore

''The Essential Tagore'' is the largest collection of Rabindranath Tagore's works available in English. It was published by Harvard University Press in the United States and Visva-Bharati University in India to mark the 150th anniversary of Tagore ...

'', the largest anthology of Tagore's works available in English; it was edited by Fakrul Alam

Fakrul Alam (born 20 July 1951) is a Bangladeshi academic, writer, and translator. He writes on literary matters and postcolonial issues and translated works of Jibanananda Das and Rabindranath Tagore into English. He is the recipient of Bangla ...

and Radha Chakravarthy and marks the 150th anniversary of Tagore's birth.

Drama

Tagore's experiences with drama began when he was sixteen, with his brother Jyotirindranath. He wrote his first original dramatic piece when he was twenty — '' Valmiki Pratibha'' which was shown at the Tagore's mansion. Tagore stated that his works sought to articulate "the play of feeling and not of action". In 1890 he wrote ''Visarjan'' (an adaptation of his novella ''Rajarshi''), which has been regarded as his finest drama. In the original Bengali language, such works included intricate subplots and extended monologues. Later, Tagore's dramas used more philosophical and allegorical themes. The play ''

Tagore's experiences with drama began when he was sixteen, with his brother Jyotirindranath. He wrote his first original dramatic piece when he was twenty — '' Valmiki Pratibha'' which was shown at the Tagore's mansion. Tagore stated that his works sought to articulate "the play of feeling and not of action". In 1890 he wrote ''Visarjan'' (an adaptation of his novella ''Rajarshi''), which has been regarded as his finest drama. In the original Bengali language, such works included intricate subplots and extended monologues. Later, Tagore's dramas used more philosophical and allegorical themes. The play ''Dak Ghar

''Dak Ghar'' 1965 Bollywood fim based on an eponymous 1912 play by Rabindranath Tagore. It was directed by Zul Vellani and starred Sachin, Mukri, AK Hangal, Sudha and Satyen Kappu among others, with cameo appearances by Balraj Sahni and Shar ...

'' (''The Post Office; 1912), describes the child Amal defying his stuffy and puerile confines by ultimately "fall ngasleep", hinting his physical death. A story with borderless appeal—gleaning rave reviews in Europe—''Dak Ghar'' dealt with death as, in Tagore's words, "spiritual freedom" from "the world of hoarded wealth and certified creeds". Another is Tagore's ''Chandalika'' (''Untouchable Girl''), which was modelled on an ancient Buddhist legend describing how Ananda, the Gautama Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was born in Lu ...

's disciple, asks a tribal

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide usage of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. This definition is contested, in part due to conflic ...

girl for water. In ''Raktakarabi'' ("Red" or "Blood Oleanders") is an allegorical struggle against a kleptocrat king who rules over the residents of ''Yaksha

The yakshas ( sa, यक्ष ; pi, yakkha, i=yes) are a broad class of nature-spirits, usually benevolent, but sometimes mischievous or capricious, connected with water, fertility, trees, the forest, treasure and wilderness. They appear in ...

puri

Puri () is a coastal city and a municipality in the state of Odisha in eastern India. It is the district headquarters of Puri district and is situated on the Bay of Bengal, south of the state capital of Bhubaneswar. It is also known as '' ...

''.

''Chitrangada'', ''Chandalika'', and ''Shyama'' are other key plays that have dance-drama adaptations, which together are known as '' Rabindra Nritya Natya''.

Short stories

Tagore began his career in short stories in 1877—when he was only sixteen—with "Bhikharini" ("The Beggar Woman").. With this, Tagore effectively invented the Bengali-language short story genre. The four years from 1891 to 1895 are known as Tagore's "Sadhana" period (named for one of Tagore's magazines). This period was among Tagore's most fecund, yielding more than half the stories contained in the three-volume ''Galpaguchchha'', which itself is a collection of eighty-four stories. Such stories usually showcase Tagore's reflections upon his surroundings, on modern and fashionable ideas, and on interesting mind puzzles (which Tagore was fond of testing his intellect with). Tagore typically associated his earliest stories (such as those of the "''Sadhana''" period) with an exuberance of vitality and spontaneity; these characteristics were intimately connected with Tagore's life in the common villages of, among others,

Tagore began his career in short stories in 1877—when he was only sixteen—with "Bhikharini" ("The Beggar Woman").. With this, Tagore effectively invented the Bengali-language short story genre. The four years from 1891 to 1895 are known as Tagore's "Sadhana" period (named for one of Tagore's magazines). This period was among Tagore's most fecund, yielding more than half the stories contained in the three-volume ''Galpaguchchha'', which itself is a collection of eighty-four stories. Such stories usually showcase Tagore's reflections upon his surroundings, on modern and fashionable ideas, and on interesting mind puzzles (which Tagore was fond of testing his intellect with). Tagore typically associated his earliest stories (such as those of the "''Sadhana''" period) with an exuberance of vitality and spontaneity; these characteristics were intimately connected with Tagore's life in the common villages of, among others, Patisar

Naogaon District ( bn, নওগাঁ, Nôugã) is a district in northern Bangladesh, part of the Rajshahi Division. It is named after its headquarters, the city of Naogaon in Naogaon Sadar Upazila.

Demographics

According to the 2022 Census ...

, Shajadpur, and Shilaida while managing the Tagore family's vast landholdings. There, he beheld the lives of India's poor and common people; Tagore thereby took to examining their lives with a penetrative depth and feeling that was singular in Indian literature up to that point. In particular, such stories as " Kabuliwala" ("The Fruitseller from Kabul

Kabul (; ps, , ; , ) is the capital and largest city of Afghanistan. Located in the eastern half of the country, it is also a municipality, forming part of the Kabul Province; it is administratively divided into 22 municipal districts. Acco ...

", published in 1892), "Kshudita Pashan" ("The Hungry Stones") (August 1895), and "Atithi" ("The Runaway", 1895) typified this analytic focus on the downtrodden. Many of the other ''Galpaguchchha'' stories were written in Tagore's ''Sabuj Patra'' period from 1914 to 1917, also named after one of the magazines that Tagore edited and heavily contributed to.

Novels

Tagore wrote eight novels and four novellas, among them ''Chaturanga'', ''Shesher Kobita

''Shesher Kabita'' (Bengali: শেষের কবিতা) is a novel by Rabindranath Tagore. The novel was serialised in 1928, from Bhadra to Choitro in the magazine ''Probashi'', and was published in book form the following year. It has been t ...

'', ''Char Odhay'', and ''Noukadubi''. ''Ghare Baire'' ('' The Home and the World'')—through the lens of the idealistic ''zamindar

A zamindar ( Hindustani: Devanagari: , ; Persian: , ) in the Indian subcontinent was an autonomous or semiautonomous ruler of a province. The term itself came into use during the reign of Mughals and later the British had begun using it as ...

'' protagonist Nikhil—excoriates rising Indian nationalism, terrorism, and religious zeal in the ''Swadeshi'' movement; a frank expression of Tagore's conflicted sentiments, it emerged from a 1914 bout of depression. The novel ends in Hindu-Muslim violence and Nikhil's—likely mortal—wounding.

''Gora'' raises controversial questions regarding the Indian identity. As with ''Ghare Baire'', matters of self-identity (''jāti

''Jāti'' is the term traditionally used to describe a cohesive group of people in the Indian subcontinent, like a tribe, community, clan, sub-clan, or a religious sect. Each Jāti typically has an association with an occupation, geography or t ...

''), personal freedom, and religion are developed in the context of a family story and love triangle. In it an Irish boy orphaned in the Sepoy Mutiny

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against the rule of the British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the British Crown. The rebellion began on 10 May 1857 in the for ...

is raised by Hindus as the titular ''gora''—"whitey". Ignorant of his foreign origins, he chastises Hindu religious backsliders out of love for the indigenous Indians and solidarity with them against his hegemon-compatriots. He falls for a Brahmo girl, compelling his worried foster father to reveal his lost past and cease his nativist zeal. As a "true dialectic" advancing "arguments for and against strict traditionalism", it tackles the colonial conundrum by "portray ngthe value of all positions within a particular frame ..not only syncretism, not only liberal orthodoxy, but the extremist reactionary traditionalism he defends by an appeal to what humans share." Among these Tagore highlights "identity ..conceived of as '' dharma.''"

In ''Jogajog

''Jogajog'' or ''Yogayog'' is a novel by Rabindranath Tagore. It was published in book form in 1929 (Asharh 1336). It was first serialised in the magazine ''Bichitra'' from Ashwin 1334 to Choitro 1335. In the first two issues the novel was titled ...

'' (''Relationships''), the heroine Kumudini—bound by the ideals of ''Śiva

Shiva (; sa, शिव, lit=The Auspicious One, Śiva ), also known as Mahadeva (; ɐɦaːd̪eːʋɐ, or Hara, is one of the principal deities of Hinduism. He is the Supreme Being in Shaivism, one of the major traditions within Hindu ...

-Sati

Sati or SATI may refer to:

Entertainment

* ''Sati'' (film), a 1989 Bengali film by Aparna Sen and starring Shabana Azmi

* ''Sati'' (novel), a 1990 novel by Christopher Pike

*Sati (singer) (born 1976), Lithuanian singer

*Sati, a character in ''Th ...

'', exemplified by Dākshāyani—is torn between her pity for the sinking fortunes of her progressive and compassionate elder brother and his foil: her roue of a husband. Tagore flaunts his feminist leanings; ''pathos'' depicts the plight and ultimate demise of women trapped by pregnancy, duty, and family honor; he simultaneously trucks with Bengal's putrescent landed gentry. The story revolves around the underlying rivalry between two families—the Chatterjees, aristocrats now on the decline (Biprodas) and the Ghosals (Madhusudan), representing new money and new arrogance. Kumudini, Biprodas' sister, is caught between the two as she is married off to Madhusudan. She had risen in an observant and sheltered traditional home, as had all her female relations.

Others were uplifting: ''Shesher Kobita''—translated twice as ''Last Poem'' and ''Farewell Song''—is his most lyrical novel, with poems and rhythmic passages written by a poet protagonist. It contains elements of satire and postmodernism and has stock characters who gleefully attack the reputation of an old, outmoded, oppressively renowned poet who, incidentally, goes by a familiar name: "Rabindranath Tagore". Though his novels remain among the least-appreciated of his works, they have been given renewed attention via film adaptations by Ray and others: '' Chokher Bali'' and '' Ghare Baire'' are exemplary. In the first, Tagore inscribes Bengali society via its heroine: a rebellious widow who would live for herself alone. He pillories the custom of perpetual mourning on the part of widows, who were not allowed to remarry, who were consigned to seclusion and loneliness. Tagore wrote of it: "I have always regretted the ending".

Poetry

Internationally, ''Gitanjali'' ( bn, গীতাঞ্জলি) is Tagore's best-known collection of poetry, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913. Tagore was the first non-European to receive a Nobel Prize in Literature and second non-European to receive a Nobel Prize after

Internationally, ''Gitanjali'' ( bn, গীতাঞ্জলি) is Tagore's best-known collection of poetry, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913. Tagore was the first non-European to receive a Nobel Prize in Literature and second non-European to receive a Nobel Prize after Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

.

Besides ''Gitanjali'', other notable works include ''Manasi'', '' Sonar Tori'' ("Golden Boat"), ''Balaka'' ("Wild Geese" — the title being a metaphor for migrating souls)

Tagore's poetic style, which proceeds from a lineage established by 15th- and 16th-century Vaishnava poets, ranges from classical formalism to the comic, visionary, and ecstatic. He was influenced by the atavistic mysticism of Vyasa

Krishna Dvaipayana ( sa, कृष्णद्वैपायन, Kṛṣṇadvaipāyana), better known as Vyasa (; sa, व्यासः, Vyāsaḥ, compiler) or Vedavyasa (वेदव्यासः, ''Veda-vyāsaḥ'', "the one who cl ...

and other ''rishi''-authors of the Upanishad

The Upanishads (; sa, उपनिषद् ) are late Vedic Sanskrit texts that supplied the basis of later Hindu philosophy.Wendy Doniger (1990), ''Textual Sources for the Study of Hinduism'', 1st Edition, University of Chicago Press, , ...

s, the Bhakti- Sufi mystic Kabir

Kabir Das (1398–1518) was a 15th-century Indian mystic poet and saint. His writings influenced Hinduism's Bhakti movement, and his verses are found in Sikhism's scripture Guru Granth Sahib, the Satguru Granth Sahib of Saint Garib Das ...

, and Ramprasad Sen

( bn, রামপ্রসাদ সেন; c. 1718 or c. 1723 – c. 1775) was a Hindu Shakta poet and saint of eighteenth century Bengal. His ''bhakti'' poems, known as Ramprasadi, are still popular in Bengal—they are usually a ...

. Tagore's most innovative and mature poetry embodies his exposure to Bengali rural folk music, which included mystic Baul

The Baul ( bn, বাউল) are a group of mystic minstrels of mixed elements of Sufism, Vaishnavism and Tantra from Bangladesh and the neighboring Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura and Assam's Barak Valley and Meghalaya. Bauls cons ...

ballads such as those of the bard Lalon

Lalon ( bn, লালন; 14 October 1772 – 17 October 1890), also known as Lalon Shah, Lalon Fakir, Shahji and titled Fakir, Shah, was a prominent Bengali spiritual leader, philosopher, mystic poet and social reformer. Regarded as an icon of ...

. These, rediscovered and re-popularized by Tagore, resemble 19th-century Kartābhajā hymns that emphasize inward divinity and rebellion against bourgeois ''bhadralok'' religious and social orthodoxy. During his Shelaidaha years, his poems took on a lyrical voice of the ''moner manush'', the Bāuls' "man within the heart" and Tagore's "life force of his deep recesses", or meditating upon the ''jeevan devata''—the demiurge or the "living God within". This figure connected with divinity through appeal to nature and the emotional interplay of human drama. Such tools saw use in his Bhānusiṃha poems chronicling the Radha-Krishna

Krishna (; sa, कृष्ण ) is a major deity in Hinduism. He is worshipped as the eighth avatar of Vishnu and also as the Supreme god in his own right. He is the god of protection, compassion, tenderness, and love; and is one ...

romance, which were repeatedly revised over the course of seventy years.

Later, with the development of new poetic ideas in Bengal – many originating from younger poets seeking to break with Tagore's style – Tagore absorbed new poetic concepts, which allowed him to further develop a unique identity. Examples of this include ''Africa'' and ''Camalia'', which are among the better known of his latter poems.

Songs (Rabindra Sangeet)

Tagore was a prolific composer with around 2,230 songs to his credit. His songs are known as '' rabindrasangit'' ("Tagore Song"), which merges fluidly into his literature, most of which—poems or parts of novels, stories, or plays alike—were lyricized. Influenced by the ''thumri

Thumri () is a vocal genre or style of Indian music. The term "thumri" is derived from the Hindi verb ''thumuknaa'', which means "to walk with a dancing gait in such a way that the ankle-bells tinkle." The form is, thus, connected with dance, dr ...

'' style of Hindustani music

Hindustani classical music is the classical music of northern regions of the Indian subcontinent. It may also be called North Indian classical music or, in Hindustani, ''shastriya sangeet'' (). It is played in instruments like the violin, sita ...

, they ran the entire gamut of human emotion, ranging from his early dirge-like Brahmo devotional hymns to quasi-erotic compositions. They emulated the tonal color of classical '' ragas'' to varying extents. Some songs mimicked a given raga's melody and rhythm faithfully, others newly blended elements of different ''ragas''. Yet about nine-tenths of his work was not ''bhanga gaan'', the body of tunes revamped with "fresh value" from select Western, Hindustani, Bengali folk and other regional flavors "external" to Tagore's own ancestral culture.

In 1971, '' Amar Shonar Bangla'' became the national anthem of Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mos ...

. It was written – ironically – to protest the 1905 Partition of Bengal

The first Partition of Bengal (1905) was a territorial reorganization of the Bengal Presidency implemented by the authorities of the British Raj. The reorganization separated the largely Muslim eastern areas from the largely Hindu western are ...

along communal lines: cutting off the Muslim-majority East Bengal from Hindu-dominated West Bengal was to avert a regional bloodbath. Tagore saw the partition as a cunning plan to stop the independence movement

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

, and he aimed to rekindle Bengali unity and tar communalism. ''Jana Gana Mana

"" (Sanskrit: जन गण मन) is the national anthem of the Republic of India. It was originally composed as '' Bharoto Bhagyo Bidhata'' in Bengali by polymath Rabindranath Tagore. The first stanza of the song ''Bharoto Bhagyo Bidhata' ...

'' was written in '' shadhu-bhasha'', a Sanskritised form of Bengali, and is the first of five stanzas of the Brahmo hymn ''Bharot Bhagyo Bidhata

''Bharoto Bhagyo Bidhata'' ( bn, ভারত ভাগ্য বিধাতা, lit=Dispenser of India's destiny) is a five-stanza Brahmo hymn in Bengali language dedicated to Supreme divine God who is the dispenser of the destiny of India. I ...

'' that Tagore composed. It was first sung in 1911 at a Calcutta session of the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party but often simply the Congress, is a political party in India with widespread roots. Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British E ...

and was adopted in 1950 by the Constituent Assembly of the Republic of India as its national anthem.

Sri Lanka's National Anthem was inspired by his work.

For Bengalis, the songs' appeal, stemming from the combination of emotive strength and beauty described as surpassing even Tagore's poetry, was such that the ''Modern Review'' observed that " ere is in Bengal no cultured home where Rabindranath's songs are not sung or at least attempted to be sung... Even illiterate villagers sing his songs". Tagore influenced ''sitar'' maestro Vilayat Khan

Ustad Vilayat Khan (28 August 1928 – 13 March 2004) was an Indian classical sitar player.sarod

The sarod is a stringed instrument, used in Hindustani music on the Indian subcontinent. Along with the sitar, it is among the most popular and prominent instruments. It is known for a deep, weighty, introspective sound, in contrast with the sweet ...

iyas'' Buddhadev Dasgupta and Amjad Ali Khan

Ustad Amjad Ali Khan (born 9 October 1945) is an Indian classical ''sarod'' player, best known for his clear and fast ekhara taans. Khan was born into a classical musical family and has performed internationally since the 1960s. He was awar ...

.

Art works

At sixty, Tagore took up drawing and painting; successful exhibitions of his many works—which made a debut appearance in Paris upon encouragement by artists he met in the south of France—were held throughout Europe. He was likely red, greencolor blind

Color blindness or color vision deficiency (CVD) is the decreased ability to see color or differences in color. It can impair tasks such as selecting ripe fruit, choosing clothing, and reading traffic lights. Color blindness may make some aca ...

, resulting in works that exhibited strange color schemes and off-beat aesthetics. Tagore was influenced by numerous styles, including scrimshaw

Scrimshaw is scrollwork, engravings, and carvings done in bone or ivory. Typically it refers to the artwork created by whalers, engraved on the byproducts of whales, such as bones or cartilage. It is most commonly made out of the bones and teeth ...

by the Malanggan people of northern New Ireland, Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea (abbreviated PNG; , ; tpi, Papua Niugini; ho, Papua Niu Gini), officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea ( tpi, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niugini; ho, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niu Gini), is a country i ...

, Haida carvings from the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (sometimes Cascadia, or simply abbreviated as PNW) is a geographic region in western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Tho ...

region of North America, and woodcuts by the German Max Pechstein

Hermann Max Pechstein (31 December 1881 – 29 June 1955) was a German expressionist painter and printmaker and a member of the Die Brücke group. He fought on the Western Front during World War I and his art was classified as Degenerate Ar ...

. His artist's eye for handwriting was revealed in the simple artistic and rhythmic leitmotifs embellishing the scribbles, cross-outs, and word layouts of his manuscripts. Some of Tagore's lyrics corresponded in a synesthetic sense with particular paintings.

India's National Gallery of Modern Art

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, c ...

lists 102 works by Tagore in its collections.

In 1937, Tagore's paintings were removed from Berlin's baroque Crown Prince Palace by the Nazi regime and five were included in the inventory of "degenerate art

Degenerate art (german: Entartete Kunst was a term adopted in the 1920s by the Nazi Party in Germany to describe modern art. During the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler, German modernist art, including many works of internationally renowned artists, ...

" compiled by the Nazis in 1941–1942.

Politics

Tagore opposed imperialism and supported Indian nationalists, and these views were first revealed in ''Manast'', which was mostly composed in his twenties. Evidence produced during the

Tagore opposed imperialism and supported Indian nationalists, and these views were first revealed in ''Manast'', which was mostly composed in his twenties. Evidence produced during the Hindu–German Conspiracy Trial The Hindu–German Conspiracy Trial commenced in the District Court in San Francisco on November 12, 1917, following the uncovering of the :Hindu–German Conspiracy (also known as the Indo German plot) for initiating a revolt in India. It was pa ...

and latter accounts affirm his awareness of the Ghadarites and stated that he sought the support of Japanese Prime Minister Terauchi Masatake

Gensui Count Terauchi Masatake ( ja, 寺内 正毅), GCB (5 February 1852 – 3 November 1919), was a Japanese military officer, proconsul and politician. He was a '' Gensui'' (or Marshal) in the Imperial Japanese Army and the Prime Minister o ...

and former Premier Ōkuma Shigenobu

Marquess was a Japanese statesman and a prominent member of the Meiji oligarchy. He served as Prime Minister of the Empire of Japan in 1898 and from 1914 to 1916. Ōkuma was also an early advocate of Western science and culture in Japan, and ...

. Yet he lampooned the Swadeshi movement

The Swadeshi movement was a self-sufficiency movement that was part of the Indian independence movement and contributed to the development of Indian nationalism. Before the BML Government's decision for the partition of Bengal was made public in ...

; he rebuked it in ''The Cult of the Charkha

''The Cult of the Charkha'' is an essay by Rabindranath Tagore which first appeared in September 1925 in the ''Modern Review (Calcutta), Modern Review''. In the essay Tagore offered critique on the Gandhism, Gandhian ethic of "Charkha (spinning wh ...

'', an acrid 1925 essay. According to Amartya Sen

Amartya Kumar Sen (; born 3 November 1933) is an Indian economist and philosopher, who since 1972 has taught and worked in the United Kingdom and the United States. Sen has made contributions to welfare economics, social choice theory, econom ...

, Tagore rebelled against strongly nationalist forms of the independence movement, and he wanted to assert India's right to be independent without denying the importance of what India could learn from abroad. He urged the masses to avoid victimology and instead seek self-help and education, and he saw the presence of British administration as a "political symptom of our social disease". He maintained that, even for those at the extremes of poverty, "there can be no question of blind revolution"; preferable to it was a "steady and purposeful education".