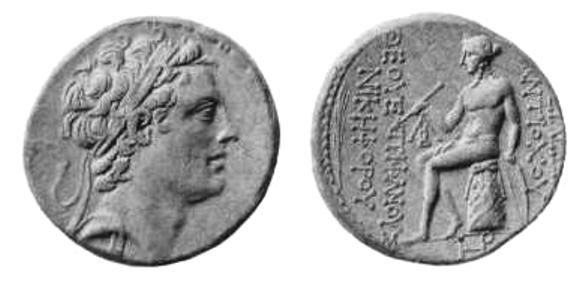

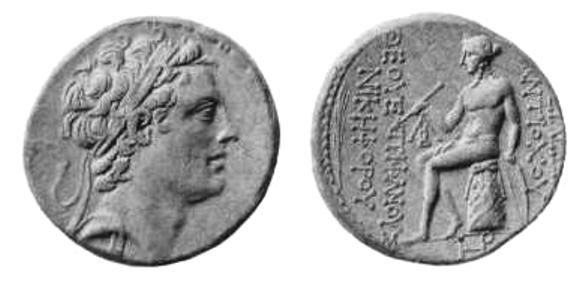

Seleucid prince Massimo Inv1049.jpg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a

It is generally thought that Chandragupta married Seleucus's daughter, or a Macedonian princess, a gift from Seleucus to formalize an alliance. In a return gesture, Chandragupta sent 500

It is generally thought that Chandragupta married Seleucus's daughter, or a Macedonian princess, a gift from Seleucus to formalize an alliance. In a return gesture, Chandragupta sent 500

Following his and Lysimachus' decisive victory over Antigonus at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC, Seleucus took control over eastern

Following his and Lysimachus' decisive victory over Antigonus at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC, Seleucus took control over eastern

Antiochus I Soter, Antiochus I (reigned 281–261 BC) and his son and successor Antiochus II Theos (reigned 261–246 BC) were faced with challenges in the west, including repeated wars with Ptolemy II of Egypt, Ptolemy II and a Celtic invasion of Asia Minor—distracting attention from holding the eastern portions of the Empire together. Towards the end of Antiochus II's reign, various provinces simultaneously asserted their independence, such as Bactria and Sogdiana under Diodotus of Bactria, Diodotus, Cappadocia under Ariarathes III of Cappadocia, Ariarathes III, and Parthia under Andragoras (Seleucid satrap), Andragoras. A few years later, the last was defeated and killed by the invading Parni of Arsaces I of Parthia, Arsaces – the region would then become the core of the Parthian Empire.

Diodotus of Bactria, Diodotus, governor for the Bactrian territory, asserted independence in around 245 BC, although the exact date is far from certain, to form the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. This kingdom was characterized by a rich Hellenistic culture and was to continue its domination of Bactria until around 125 BC when it was overrun by the invasion of northern nomads. One of the Greco-Bactrian kings, Demetrius I of Bactria, invaded India around 180 BC to form the Indo-Greek Kingdoms.

The rulers of Persis, called Fratarakas, also seem to have established some level of independence from the Seleucids during the 3rd century BC, especially from the time of Vahbarz. They would later overtly take the title of Kings of Persis, before becoming vassals to the newly formed Parthian Empire.

The Seleucid satrap of Parthia, named Andragoras (3rd century BC), Andragoras, first claimed independence, in a parallel to the secession of his Bactrian neighbour. Soon after, however, a Parthian tribal chief called Arsaces I of Parthia, Arsaces Parni conquest of Parthia, invaded the Parthian territory around 238 BC to form the Parthian Empire, Arsacid dynasty, from which the Parthian Empire originated.

Antiochus II's son Seleucus II Callinicus came to the throne around 246 BC. Seleucus II was soon dramatically defeated in the Third Syrian War against Ptolemy III of Egypt and then had to fight a civil war against his own brother Antiochus Hierax. Taking advantage of this distraction, Bactria and Parthia seceded from the empire. In Asia Minor too, the Seleucid dynasty seemed to be losing control: the Gauls had fully established themselves in Galatia, semi-independent semi-Hellenized kingdoms had sprung up in Bithynia, Pontus (region), Pontus, and Cappadocia, and the city of Kingdom of Pergamon, Pergamum in the west was asserting its independence under the Attalid Dynasty. The Seleucid economy started to show the first signs of weakness, as Galatians gained independence and Pergamum took control of coastal cities in Anatolia. Consequently, they managed to partially block contact with the West.

Antiochus I Soter, Antiochus I (reigned 281–261 BC) and his son and successor Antiochus II Theos (reigned 261–246 BC) were faced with challenges in the west, including repeated wars with Ptolemy II of Egypt, Ptolemy II and a Celtic invasion of Asia Minor—distracting attention from holding the eastern portions of the Empire together. Towards the end of Antiochus II's reign, various provinces simultaneously asserted their independence, such as Bactria and Sogdiana under Diodotus of Bactria, Diodotus, Cappadocia under Ariarathes III of Cappadocia, Ariarathes III, and Parthia under Andragoras (Seleucid satrap), Andragoras. A few years later, the last was defeated and killed by the invading Parni of Arsaces I of Parthia, Arsaces – the region would then become the core of the Parthian Empire.

Diodotus of Bactria, Diodotus, governor for the Bactrian territory, asserted independence in around 245 BC, although the exact date is far from certain, to form the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. This kingdom was characterized by a rich Hellenistic culture and was to continue its domination of Bactria until around 125 BC when it was overrun by the invasion of northern nomads. One of the Greco-Bactrian kings, Demetrius I of Bactria, invaded India around 180 BC to form the Indo-Greek Kingdoms.

The rulers of Persis, called Fratarakas, also seem to have established some level of independence from the Seleucids during the 3rd century BC, especially from the time of Vahbarz. They would later overtly take the title of Kings of Persis, before becoming vassals to the newly formed Parthian Empire.

The Seleucid satrap of Parthia, named Andragoras (3rd century BC), Andragoras, first claimed independence, in a parallel to the secession of his Bactrian neighbour. Soon after, however, a Parthian tribal chief called Arsaces I of Parthia, Arsaces Parni conquest of Parthia, invaded the Parthian territory around 238 BC to form the Parthian Empire, Arsacid dynasty, from which the Parthian Empire originated.

Antiochus II's son Seleucus II Callinicus came to the throne around 246 BC. Seleucus II was soon dramatically defeated in the Third Syrian War against Ptolemy III of Egypt and then had to fight a civil war against his own brother Antiochus Hierax. Taking advantage of this distraction, Bactria and Parthia seceded from the empire. In Asia Minor too, the Seleucid dynasty seemed to be losing control: the Gauls had fully established themselves in Galatia, semi-independent semi-Hellenized kingdoms had sprung up in Bithynia, Pontus (region), Pontus, and Cappadocia, and the city of Kingdom of Pergamon, Pergamum in the west was asserting its independence under the Attalid Dynasty. The Seleucid economy started to show the first signs of weakness, as Galatians gained independence and Pergamum took control of coastal cities in Anatolia. Consequently, they managed to partially block contact with the West.

A revival would begin when Seleucus II's younger son,

A revival would begin when Seleucus II's younger son,

Following the defeat of his erstwhile ally Philip V of Macedon, Philip by Rome in 197 BC, Antiochus saw the opportunity for expansion into Greece itself. Encouraged by the exiled Carthage, Carthaginian general Hannibal, and making an alliance with the disgruntled Aetolian League, Antiochus launched an invasion across the Hellespont. With his huge army he aimed to establish the Seleucid empire as the foremost power in the Hellenic world, but these plans put the empire on a collision course with the new rising power of the Mediterranean, the

Following the defeat of his erstwhile ally Philip V of Macedon, Philip by Rome in 197 BC, Antiochus saw the opportunity for expansion into Greece itself. Encouraged by the exiled Carthage, Carthaginian general Hannibal, and making an alliance with the disgruntled Aetolian League, Antiochus launched an invasion across the Hellespont. With his huge army he aimed to establish the Seleucid empire as the foremost power in the Hellenic world, but these plans put the empire on a collision course with the new rising power of the Mediterranean, the

The reign of his son and successor Seleucus IV Philopator (187–175 BC) was largely spent in attempts to pay the large indemnity, and Seleucus was ultimately assassinated by his minister Heliodorus (minister), Heliodorus.

Seleucus' younger brother, Antiochus IV Epiphanes, now seized the throne. He attempted to restore Seleucid power and prestige with a successful war against the old enemy, Ptolemaic Egypt, which met with initial success as the Seleucids defeated and drove the Egyptian army back to Alexandria itself. As the king planned on how to conclude the war, he was informed that Roman commissioners, led by the Proconsul Gaius Popillius Laenas, were near and requesting a meeting with the Seleucid king. Antiochus agreed, but when they met and Antiochus held out his hand in friendship, Popilius placed in his hand the tablets on which was written the decree of the senate and told him to read it. The decree demanded that he should abort his attack on Alexandria and immediately stop waging the war on Ptolemy. When the king said that he would call his friends into council and consider what he ought to do, Popilius drew a circle in the sand around the king's feet with the stick he was carrying and said, "Before you step out of that circle give me a reply to lay before the senate." For a few moments he hesitated, astounded at such a peremptory order, and at last replied, "I will do what the senate thinks right." He then chose to withdraw rather than set the empire to war with Rome again.

On his return journey, according to Josephus, he made an expedition to Judea, took Jerusalem by force, slew a great many who had favored Ptolemaic Egypt, Ptolemy, sent his soldiers to plunder them without mercy. He also spoiled the Second temple, temple, and interrupted the constant practice of offering a daily sacrifice of expiation, for three years and six months.

The latter part of his reign saw a further disintegration of the Empire despite his best efforts. Weakened economically, militarily and by loss of prestige, the Empire became vulnerable to rebels in the eastern areas of the empire, who began to further undermine the empire while the Parthians moved into the power vacuum to take over the old Persian lands. Antiochus' aggressive Hellenizing (or de-Judaizing) activities provoked a full scale armed rebellion in Judea—the Maccabean Revolt. Efforts to deal with both the Parthians and the Jews as well as retain control of the provinces at the same time proved beyond the weakened empire's power. Antiochus died during a military expedition against the Parthians in 164 BC.

The reign of his son and successor Seleucus IV Philopator (187–175 BC) was largely spent in attempts to pay the large indemnity, and Seleucus was ultimately assassinated by his minister Heliodorus (minister), Heliodorus.

Seleucus' younger brother, Antiochus IV Epiphanes, now seized the throne. He attempted to restore Seleucid power and prestige with a successful war against the old enemy, Ptolemaic Egypt, which met with initial success as the Seleucids defeated and drove the Egyptian army back to Alexandria itself. As the king planned on how to conclude the war, he was informed that Roman commissioners, led by the Proconsul Gaius Popillius Laenas, were near and requesting a meeting with the Seleucid king. Antiochus agreed, but when they met and Antiochus held out his hand in friendship, Popilius placed in his hand the tablets on which was written the decree of the senate and told him to read it. The decree demanded that he should abort his attack on Alexandria and immediately stop waging the war on Ptolemy. When the king said that he would call his friends into council and consider what he ought to do, Popilius drew a circle in the sand around the king's feet with the stick he was carrying and said, "Before you step out of that circle give me a reply to lay before the senate." For a few moments he hesitated, astounded at such a peremptory order, and at last replied, "I will do what the senate thinks right." He then chose to withdraw rather than set the empire to war with Rome again.

On his return journey, according to Josephus, he made an expedition to Judea, took Jerusalem by force, slew a great many who had favored Ptolemaic Egypt, Ptolemy, sent his soldiers to plunder them without mercy. He also spoiled the Second temple, temple, and interrupted the constant practice of offering a daily sacrifice of expiation, for three years and six months.

The latter part of his reign saw a further disintegration of the Empire despite his best efforts. Weakened economically, militarily and by loss of prestige, the Empire became vulnerable to rebels in the eastern areas of the empire, who began to further undermine the empire while the Parthians moved into the power vacuum to take over the old Persian lands. Antiochus' aggressive Hellenizing (or de-Judaizing) activities provoked a full scale armed rebellion in Judea—the Maccabean Revolt. Efforts to deal with both the Parthians and the Jews as well as retain control of the provinces at the same time proved beyond the weakened empire's power. Antiochus died during a military expedition against the Parthians in 164 BC.

After the death of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, the Seleucid Empire became increasingly unstable. Frequent civil wars made central authority tenuous at best. Epiphanes' young son, Antiochus V Eupator, was first overthrown by Seleucus IV's son, Demetrius I Soter in 161 BC. Demetrius I attempted to restore Seleucid power in Judea particularly, but was overthrown in 150 BC by

After the death of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, the Seleucid Empire became increasingly unstable. Frequent civil wars made central authority tenuous at best. Epiphanes' young son, Antiochus V Eupator, was first overthrown by Seleucus IV's son, Demetrius I Soter in 161 BC. Demetrius I attempted to restore Seleucid power in Judea particularly, but was overthrown in 150 BC by

By 100 BC, the once-formidable Seleucid Empire encompassed little more than Antioch and some Syrian cities. Despite the clear collapse of their power, and the decline of their kingdom around them, nobles continued to play kingmakers on a regular basis, with occasional intervention from Ptolemaic Egypt and other outside powers. The Seleucids existed solely because no other nation wished to absorb them – seeing as they constituted a useful buffer between their other neighbours. In the wars in Anatolia between Mithridates VI of Kingdom of Pontus, Pontus and Sulla of Rome, the Seleucids were largely left alone by both major combatants.

Mithridates' ambitious son-in-law,

By 100 BC, the once-formidable Seleucid Empire encompassed little more than Antioch and some Syrian cities. Despite the clear collapse of their power, and the decline of their kingdom around them, nobles continued to play kingmakers on a regular basis, with occasional intervention from Ptolemaic Egypt and other outside powers. The Seleucids existed solely because no other nation wished to absorb them – seeing as they constituted a useful buffer between their other neighbours. In the wars in Anatolia between Mithridates VI of Kingdom of Pontus, Pontus and Sulla of Rome, the Seleucids were largely left alone by both major combatants.

Mithridates' ambitious son-in-law,

As with the other major Hellenistic armies, the Seleucid army fought primarily in the Greco-Macedonian style, with its main body being the Phalanx formation, phalanx. The phalanx was a large, dense formation of men armed with small shields and a long pike called the ''sarissa''. This form of fighting had been developed by the Ancient Macedonian army, Macedonian army in the reign of Philip II of Macedon and his son Alexander the Great. Alongside the phalanx, the Seleucid armies used a great deal of native and mercenary troops to supplement their Greek forces, which were limited due to the distance from the Seleucid rulers' Macedonian homeland. The size of the Seleucid army usually varied between 70,000 and 200,000 in manpower.

The distance from Greece put a strain on the Seleucid military system, as it was primarily based around the recruitment of Greeks as the key segment of the army. In order to increase the population of Greeks in their kingdom, the Seleucid rulers created military settlements. There were two main periods in the establishment of settlements, firstly under

As with the other major Hellenistic armies, the Seleucid army fought primarily in the Greco-Macedonian style, with its main body being the Phalanx formation, phalanx. The phalanx was a large, dense formation of men armed with small shields and a long pike called the ''sarissa''. This form of fighting had been developed by the Ancient Macedonian army, Macedonian army in the reign of Philip II of Macedon and his son Alexander the Great. Alongside the phalanx, the Seleucid armies used a great deal of native and mercenary troops to supplement their Greek forces, which were limited due to the distance from the Seleucid rulers' Macedonian homeland. The size of the Seleucid army usually varied between 70,000 and 200,000 in manpower.

The distance from Greece put a strain on the Seleucid military system, as it was primarily based around the recruitment of Greeks as the key segment of the army. In order to increase the population of Greeks in their kingdom, the Seleucid rulers created military settlements. There were two main periods in the establishment of settlements, firstly under

Currency plays an increasingly central role under the Seleucids; however, we should note that monetization was nothing new in their newly acquired lands. Rather, the introduction and widespread implementation of currency is attributed to Darius I's tax reforms centuries prior; hence, the Seleucids see a continuation rather than shift in this practice, i.e. the payment of taxation in silver or, if necessary, in kind. In this regard, the Seleucids are notable for paying their sizeable armies exclusively in silver. Nevertheless, there are two significant developments of currency during the Seleucid period: the adoption of the "Attic Standard" in certain regions, and the popularization of bronze coinage.

The adoption of the Attic standard was not uniform across the realm. The Attic standard was already the common currency of the Mediterranean prior to Alexander's conquest; that is, it was the preferred currency for foreign transactions. As a result, coastal regions under the Seleucids —Syria and Asia Minor—were quick to adopt the new standard. In Mesopotamia however, the millennia-old shekel (weighing 8.33g Silver) prevailed over the Attic standard. According to Historian R.J. van der Spek, this is due to their particular method in recording price, which favored bartering over monetary transactions. The Mesopotamians used the value of one shekel as a fixed reference point, against which the amount of a good is given. Prices themselves are accounted in terms of their weight in silver ''per ton'', i.e. 60g Silver, Barley, June 242 BC. The minute difference in weight between a Shekel and Didrachm (weighing 8.6g Silver) could not be expressed in this barter system. And the use of a Greek tetradrachm would be "a far too heavy denomination…in daily trade."

Bronze coinage, dating from the late fifth and fourth century, and was popularized as a "fiduciary" currency facilitating "small-scale exchanges" in the Hellenistic period. It was principally a legal tender which circulated only around its locales of production;[3]however, the great Seleucid mint at Antioch during Antiochus III's reign (which Numismatist Arthur Houghton dubs "The Syrian and Coele-Syrian Experiment") began minting bronze coins (weighing 1.25–1.5g) to serve a "regional purpose." The reasons behind this remain unclear. However, Spek notes a chronic shortage of silver in the Seleucid empire. In fact, Antiochus I's heavy withdrawal of silver from a satrap is noted by the Babylonian astronomical diary (AD No. –273 B 'Rev. 33'): "purchases in Babylon and other cities were made in Greek bronze coins." This was unprecedented because "in official documents [bronze coins] played no part"; it was a sign of "hardship" for the Seleucids. Nevertheless, the low denomination of bronze coinage meant it was used in tandem with bartering; making it a popular and successful medium of exchange.

Currency plays an increasingly central role under the Seleucids; however, we should note that monetization was nothing new in their newly acquired lands. Rather, the introduction and widespread implementation of currency is attributed to Darius I's tax reforms centuries prior; hence, the Seleucids see a continuation rather than shift in this practice, i.e. the payment of taxation in silver or, if necessary, in kind. In this regard, the Seleucids are notable for paying their sizeable armies exclusively in silver. Nevertheless, there are two significant developments of currency during the Seleucid period: the adoption of the "Attic Standard" in certain regions, and the popularization of bronze coinage.

The adoption of the Attic standard was not uniform across the realm. The Attic standard was already the common currency of the Mediterranean prior to Alexander's conquest; that is, it was the preferred currency for foreign transactions. As a result, coastal regions under the Seleucids —Syria and Asia Minor—were quick to adopt the new standard. In Mesopotamia however, the millennia-old shekel (weighing 8.33g Silver) prevailed over the Attic standard. According to Historian R.J. van der Spek, this is due to their particular method in recording price, which favored bartering over monetary transactions. The Mesopotamians used the value of one shekel as a fixed reference point, against which the amount of a good is given. Prices themselves are accounted in terms of their weight in silver ''per ton'', i.e. 60g Silver, Barley, June 242 BC. The minute difference in weight between a Shekel and Didrachm (weighing 8.6g Silver) could not be expressed in this barter system. And the use of a Greek tetradrachm would be "a far too heavy denomination…in daily trade."

Bronze coinage, dating from the late fifth and fourth century, and was popularized as a "fiduciary" currency facilitating "small-scale exchanges" in the Hellenistic period. It was principally a legal tender which circulated only around its locales of production;[3]however, the great Seleucid mint at Antioch during Antiochus III's reign (which Numismatist Arthur Houghton dubs "The Syrian and Coele-Syrian Experiment") began minting bronze coins (weighing 1.25–1.5g) to serve a "regional purpose." The reasons behind this remain unclear. However, Spek notes a chronic shortage of silver in the Seleucid empire. In fact, Antiochus I's heavy withdrawal of silver from a satrap is noted by the Babylonian astronomical diary (AD No. –273 B 'Rev. 33'): "purchases in Babylon and other cities were made in Greek bronze coins." This was unprecedented because "in official documents [bronze coins] played no part"; it was a sign of "hardship" for the Seleucids. Nevertheless, the low denomination of bronze coinage meant it was used in tandem with bartering; making it a popular and successful medium of exchange.

Recent evidence indicates that Mesopotamian grain production, under the Seleucids, was subject to market forces of supply and demand. Traditional "primitivist" narratives of the ancient economy argue that it was "marketless"; however, the Babylonian astronomical diaries show a high degree of market integration of barley and date prices—to name a few—in Seleucid Babylonia. Prices exceeding ''370g'' silver per ton in Seleucid Mesopotamia was considered a sign of famine. Therefore, during periods of war, heavy taxation, and crop failure, prices increase drastically. In an extreme example, Spek believes tribal Arab raiding into Babylonia caused barley prices to skyrocket to a whopping ''1493g'' silver per ton from 5–8 May, 124 BC. The average Mesopotamian peasant, if working for a wage at a temple, would receive 1 shekel; it "was a reasonable monthly wage for which one could buy one kor of grain= 180 [liters]." While this appears dire, we should be reminded that Mesopotamia under the Seleucids was largely stable and prices remained low. With encouraged Greek colonization and land reclamation increasing the supply of grain production, however, the question of whether this artificially kept prices stable is uncertain.

The Seleucids also continued the tradition of actively maintaining the Mesopotamian waterways. As the greatest source of state income, the Seleucid kings actively managed the irrigation, reclamation, and population of Mesopotamia. In fact, canals were often dug by royal decrees, to which "some were called the King's Canal for that reason." For example, the construction of the Pallacottas canal was able to control the water level of the Euphrates which, as Arrian notes in his Anabasis 7.21.5, required: "over two months of work by more than 10,000 Assyrians."

Recent evidence indicates that Mesopotamian grain production, under the Seleucids, was subject to market forces of supply and demand. Traditional "primitivist" narratives of the ancient economy argue that it was "marketless"; however, the Babylonian astronomical diaries show a high degree of market integration of barley and date prices—to name a few—in Seleucid Babylonia. Prices exceeding ''370g'' silver per ton in Seleucid Mesopotamia was considered a sign of famine. Therefore, during periods of war, heavy taxation, and crop failure, prices increase drastically. In an extreme example, Spek believes tribal Arab raiding into Babylonia caused barley prices to skyrocket to a whopping ''1493g'' silver per ton from 5–8 May, 124 BC. The average Mesopotamian peasant, if working for a wage at a temple, would receive 1 shekel; it "was a reasonable monthly wage for which one could buy one kor of grain= 180 [liters]." While this appears dire, we should be reminded that Mesopotamia under the Seleucids was largely stable and prices remained low. With encouraged Greek colonization and land reclamation increasing the supply of grain production, however, the question of whether this artificially kept prices stable is uncertain.

The Seleucids also continued the tradition of actively maintaining the Mesopotamian waterways. As the greatest source of state income, the Seleucid kings actively managed the irrigation, reclamation, and population of Mesopotamia. In fact, canals were often dug by royal decrees, to which "some were called the King's Canal for that reason." For example, the construction of the Pallacottas canal was able to control the water level of the Euphrates which, as Arrian notes in his Anabasis 7.21.5, required: "over two months of work by more than 10,000 Assyrians."

ISBN 978-0-520081833 .

Livius

by Jona Lendering

Genealogy of the Seleucids

{{Authority control Seleucid Empire, Ancient history of Iran Former empires in Asia Former countries in Central Asia Former countries in South Asia Former countries in Western Asia Superpowers 4th-century BC establishments States and territories established in the 4th century BC 310s BC establishments 312 BC States and territories disestablished in the 1st century BC 63 BC disestablishments Classical Anatolia Empires and kingdoms of Iran Offshoots of the Macedonian Empire Former monarchies of Central Asia Former monarchies of Western Asia Former monarchies of South Asia

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

state in West Asia

Western Asia, West Asia, or Southwest Asia, is the westernmost subregion of the larger geographical region of Asia, as defined by some academics, UN bodies and other institutions. It is almost entirely a part of the Middle East, and includes Ana ...

that existed during the Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the Macedonian general Seleucus I Nicator

Seleucus I Nicator (; ; grc-gre, Σέλευκος Νικάτωρ , ) was a Macedonian Greek general who was an officer and successor ( ''diadochus'') of Alexander the Great. Seleucus was the founder of the eponymous Seleucid Empire. In the po ...

, following the division

Division or divider may refer to:

Mathematics

*Division (mathematics), the inverse of multiplication

*Division algorithm, a method for computing the result of mathematical division

Military

*Division (military), a formation typically consisting ...

of the Macedonian Empire

Macedonia (; grc-gre, Μακεδονία), also called Macedon (), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, and later the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled ...

originally founded by Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

.

After receiving the Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

n region of Babylonia in 321 BC, Seleucus I began expanding his dominions to include the Near Eastern territories that encompass modern-day Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to the north, Iran to the east, the Persian Gulf and K ...

, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

, Syria, all of which had been under Macedonian control after the fall of the former Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

n Achaemenid Empire. At the Seleucid Empire's height, it had consisted of territory that had covered Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

, Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

, and what are now modern Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to the north, Iran to the east, the Persian Gulf and K ...

, Kuwait

Kuwait (; ar, الكويت ', or ), officially the State of Kuwait ( ar, دولة الكويت '), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated in the northern edge of Eastern Arabia at the tip of the Persian Gulf, bordering Iraq to the nort ...

, Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

, and parts of Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan ( or ; tk, Türkmenistan / Түркменистан, ) is a country located in Central Asia, bordered by Kazakhstan to the northwest, Uzbekistan to the north, east and northeast, Afghanistan to the southeast, Iran to the sout ...

.

The Seleucid Empire was a major center of Hellenistic culture

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

. Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

customs and language were privileged; the wide variety of local traditions had been generally tolerated, while an urban Greek elite had formed the dominant political class and was reinforced by steady immigration from Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

.Britannica,'' Seleucid kingdom'', 2008, O.Ed. The empire's western territories were repeatedly contested with Ptolemaic Egypt—a rival Hellenistic state. To the east, conflict with the Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

ruler Chandragupta of the Maurya Empire in 305 BC led to the cession

The act of cession is the assignment of property to another entity. In international law it commonly refers to land transferred by treaty. Ballentine's Law Dictionary defines cession as "a surrender; a giving up; a relinquishment of jurisdictio ...

of vast territory west of the Indus and a political alliance.

In the early second century BC, Antiochus III the Great

Antiochus III the Great (; grc-gre, Ἀντίoχoς Μέγας ; c. 2413 July 187 BC) was a Greek Hellenistic king and the 6th ruler of the Seleucid Empire, reigning from 222 to 187 BC. He ruled over the region of Syria and large parts of the res ...

attempted to project Seleucid power and authority into Hellenistic Greece

Hellenistic Greece is the historical period of the country following Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the annexation of the classical Greek Achaean League heartlands by the Roman Republic. This culminated ...

, but his attempts were thwarted by the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

and its Greek allies. The Seleucids were forced to pay costly war reparations

War reparations are compensation payments made after a war by one side to the other. They are intended to cover damage or injury inflicted during a war.

History

Making one party pay a war indemnity is a common practice with a long history.

...

and had to relinquish territorial claims west of the Taurus Mountains

The Taurus Mountains ( Turkish: ''Toros Dağları'' or ''Toroslar'') are a mountain complex in southern Turkey, separating the Mediterranean coastal region from the central Anatolian Plateau. The system extends along a curve from Lake Eğird ...

in southern Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

, marking the gradual decline of their empire. Mithridates I of Parthia conquered much of the remaining eastern lands of the Seleucid Empire in the mid-second century BC, while the independent Greco-Bactrian Kingdom continued to flourish in the northeast. The Seleucid kings were thereafter reduced to a rump state

A rump state is the remnant of a once much larger state, left with a reduced territory in the wake of secession, annexation, occupation, decolonization, or a successful coup d'état or revolution on part of its former territory. In the last case ...

in Syria, until their conquest by Tigranes the Great

Tigranes II, more commonly known as Tigranes the Great ( hy, Տիգրան Մեծ, ''Tigran Mets''; grc, Τιγράνης ὁ Μέγας ''Tigránes ho Mégas''; la, Tigranes Magnus) (140 – 55 BC) was King of Armenia under whom the ...

of Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ' ...

in 83 BC, and ultimate overthrow by the Roman general Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a leading Roman general and statesman. He played a significant role in the transformation of ...

in 63 BC.

Name

Contemporary sources, such as a loyalist decree honoring Antiochus I from Ilium, in Greek language define the Seleucid state both as an empire (''arche'') and as a kingdom (''basileia''). Similarly, Seleucid rulers were described as kings in Babylonia. Starting from the 2nd century BC, ancient writers referred to the Seleucid ruler as theKing of Syria

The title King of Syria appeared in the second century BC in referring to the Seleucid kings who ruled the entirety of the region of Syria. It was also used to refer to Aramean kings in the Greek translations of the Old Testament, mainly indicatin ...

, Lord of Asia

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

, and other designations; the evidence for the Seleucid rulers representing themselves as kings of Syria is provided by the inscription of Antigonus son of Menophilus, who described himself as the "admiral of Alexander, king of Syria". He refers to either Alexander Balas

Alexander I Theopator Euergetes, surnamed Balas ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος Βάλας, Alexandros Balas), was the ruler of the Seleucid Empire from 150/Summer 152 – August 145 BC. Picked from obscurity and supported by the neighboring Roman ...

or Alexander II Zabinas

Alexander II Theos Epiphanes Nikephoros ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος Θεός Ἐπιφανής Νικηφόρος ''Áléxandros Theós Épiphanḗs Nikēphóros'', surnamed Zabinas; 150 BC – 123 BC) was a Hellenistic Seleucid monarch who r ...

as a ruler.

History

Partition of Alexander's empire

Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

, who quickly conquered the Persian Empire under its last Achaemenid dynast, Darius III, died young in 323 BC, leaving an expansive empire of partly Hellenised culture without an adult heir. The empire was put under the authority of a regent, Perdiccas

Perdiccas ( el, Περδίκκας, ''Perdikkas''; 355 BC – 321/320 BC) was a general of Alexander the Great. He took part in the Macedonian campaign against the Achaemenid Empire, and, following Alexander's death in 323 BC, rose to beco ...

, and the vast territories were divided among Alexander's generals, who thereby became satraps at the Partition of Babylon, all in that same year.

Rise of Seleucus

Alexander's generals, known as ''diadochi

The Diadochi (; singular: Diadochus; from grc-gre, Διάδοχοι, Diádochoi, Successors, ) were the rival generals, families, and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for control over his empire after his death in 323 BC. The War ...

'', jostled for supremacy over parts of his empire following his death. Ptolemy I Soter

Ptolemy I Soter (; gr, Πτολεμαῖος Σωτήρ, ''Ptolemaîos Sōtḗr'' "Ptolemy the Savior"; c. 367 BC – January 282 BC) was a Macedonian Greek general, historian and companion of Alexander the Great from the Kingdom of Macedo ...

, a former general and then current satrap of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

, was the first to challenge the new system, which eventually led to the demise of Perdiccas. Ptolemy's revolt created a new subdivision of the empire with the Partition of Triparadisus

The Partition of Triparadisus was a power-sharing agreement passed at Triparadisus in 321 BC between the generals (''Diadochi'') of Alexander the Great, in which they named a new regent and arranged the repartition of the satrapies of Alexander's e ...

in 320 BC. Seleucus, who had been "Commander-in-Chief of the Companion cavalry

The Companions ( el, , ''hetairoi'') were the elite cavalry of the Macedonian army from the time of king Philip II of Macedon, achieving their greatest prestige under Alexander the Great, and regarded as the first or among the first shock cav ...

" (''hetairoi'') and appointed first or court chiliarch Chiliarch is a military rank dating back to antiquity. Originally denoting the commander of a unit of about one thousand men (a chiliarchy) in the Macedonian army, it was subsequently used as a Greek translation of a Persian officer who functioned ...

(which made him the senior officer in the Royal Army after the regent and commander-in-chief Perdiccas since 323 BC, though he helped to assassinate him later) received Babylonia and, from that point, continued to expand his dominions ruthlessly. Seleucus established himself in Babylon in 312 BC, the year later used as the foundation date of the Seleucid Empire.

Babylonian War (311–309 BC)

The rise of Seleucus in Babylon threatened the eastern extent of the territory of Antigonus I Monophthalmus in Asia. Antigonus, along with his sonDemetrius I Poliorcetes

Demetrius I (; grc, Δημήτριος; 337–283 BC), also called Poliorcetes (; el, Πολιορκητής, "The Besieger"), was a Macedonian nobleman, military leader, and king of Macedon (294–288 BC). He belonged to the Antigonid dynasty ...

, unsuccessfully led a campaign to annex Babylon. The victory of Seleucus ensured his claim of Babylon and legitimacy. He ruled not only Babylonia, but the entire enormous eastern part of Alexander's empire, as described by the historian Appian

Appian of Alexandria (; grc-gre, Ἀππιανὸς Ἀλεξανδρεύς ''Appianòs Alexandreús''; la, Appianus Alexandrinus; ) was a Greek historian with Roman citizenship who flourished during the reigns of Emperors of Rome Trajan, Ha ...

:

Seleucid–Mauryan War (305–303 BC)

Chandragupta Maurya ( Sandrokottos) founded the Maurya Empire in 321 BC after theconquest

Conquest is the act of military subjugation of an enemy by force of arms.

Military history provides many examples of conquest: the Roman conquest of Britain, the Mauryan conquest of Afghanistan and of vast areas of the Indian subcontinent, t ...

of the Nanda Empire and their capital Pataliputra

Pataliputra ( IAST: ), adjacent to modern-day Patna, was a city in ancient India, originally built by Magadha ruler Ajatashatru in 490 BCE as a small fort () near the Ganges river.. Udayin laid the foundation of the city of Pataliputra at the ...

in Magadha

Magadha was a region and one of the sixteen sa, script=Latn, Mahajanapadas, label=none, lit=Great Kingdoms of the Second Urbanization (600–200 BCE) in what is now south Bihar (before expansion) at the eastern Ganges Plain. Magadha was ruled ...

. Chandragupta then redirected his attention to the Indus and by 317 BC he conquered the remaining Greek satraps left by Alexander. Expecting a confrontation, Seleucus gathered his army and marched to the Indus. It is said that Chandragupta could have fielded a conscript

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

army of 600,000 men and 9,000 war elephants.

Mainstream scholarship asserts that Chandragupta received, formalized through a treaty, vast territory west of the Indus, including the Hindu Kush

The Hindu Kush is an mountain range in Central and South Asia to the west of the Himalayas. It stretches from central and western Afghanistan, Quote: "The Hindu Kush mountains run along the Afghan border with the North-West Frontier Province ...

, modern day Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

, and the Balochistan

Balochistan ( ; bal, بلۏچستان; also romanised as Baluchistan and Baluchestan) is a historical region in Western and South Asia, located in the Iranian plateau's far southeast and bordering the Indian Plate and the Arabian Sea coastline. ...

province of Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 243 million people, and has the world's second-lar ...

. Archaeologically, concrete indications of Mauryan rule, such as the inscriptions of the Edicts of Ashoka

The Edicts of Ashoka are a collection of more than thirty inscriptions on the Pillars of Ashoka, as well as boulders and cave walls, attributed to Emperor Ashoka of the Maurya Empire who reigned from 268 BCE to 232 BCE. Ashoka used the exp ...

, are known as far as Kandahar

Kandahar (; Kandahār, , Qandahār) is a city in Afghanistan, located in the south of the country on the Arghandab River, at an elevation of . It is Afghanistan's second largest city after Kabul, with a population of about 614,118. It is the c ...

in southern Afghanistan. According to Appian:

It is generally thought that Chandragupta married Seleucus's daughter, or a Macedonian princess, a gift from Seleucus to formalize an alliance. In a return gesture, Chandragupta sent 500

It is generally thought that Chandragupta married Seleucus's daughter, or a Macedonian princess, a gift from Seleucus to formalize an alliance. In a return gesture, Chandragupta sent 500 war elephant

A war elephant was an elephant that was trained and guided by humans for combat. The war elephant's main use was to charge the enemy, break their ranks and instill terror and fear. Elephantry is a term for specific military units using elepha ...

s, a military asset which would play a decisive role at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC. In addition to this treaty, Seleucus dispatched an ambassador, Megasthenes

Megasthenes ( ; grc, Μεγασθένης, c. 350 BCE– c. 290 BCE) was an ancient Greek historian, diplomat and Indian ethnographer and explorer in the Hellenistic period. He described India in his book '' Indica'', which is now lost, but ha ...

, to Chandragupta, and later Deimakos

Deimachus or Daimachus (; grc, Δηΐμαχος or Δαΐμαχος) was a Greek from Plataeae, who lived during the third-century BCE. He became an ambassador to the court of the Mauryan ruler Bindusara "Amitragatha" (son of Chandragupta Mau ...

to his son Bindusara

Bindusara (), also Amitraghāta or Amitrakhāda (Sanskrit: अमित्रघात, "slayer of enemies" or "devourer of enemies") or Amitrochates (Greek: Ἀμιτροχάτης) (Strabo calls him Allitrochades (Ἀλλιτροχάδης)) ...

, at the Mauryan court at Pataliputra

Pataliputra ( IAST: ), adjacent to modern-day Patna, was a city in ancient India, originally built by Magadha ruler Ajatashatru in 490 BCE as a small fort () near the Ganges river.. Udayin laid the foundation of the city of Pataliputra at the ...

(modern Patna in Bihar state). Megasthenes wrote detailed descriptions of India and Chandragupta's reign, which have been partly preserved to us through Diodorus Siculus. Later Ptolemy II Philadelphus, the ruler of Ptolemaic Egypt and contemporary of Ashoka the Great, is also recorded by Pliny the Elder as having sent an ambassador named Dionysius (ambassador), Dionysius to the Mauryan court.

Other territories ceded before Seleucus' death were Gedrosia in the south-east of the Iranian plateau, and, to the north of this, Arachosia on the west bank of the Indus River.

Westward expansion

Following his and Lysimachus' decisive victory over Antigonus at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC, Seleucus took control over eastern

Following his and Lysimachus' decisive victory over Antigonus at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC, Seleucus took control over eastern Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

and northern Syria.

In the latter area, he founded a new capital at Antioch on the Orontes, a city he named after his father. An alternative capital was established at Seleucia on the Tigris, north of Babylon. Seleucus's empire reached its greatest extent following his defeat of his erstwhile ally, Lysimachus, at Battle of Corupedion, Corupedion in 281 BC, after which Seleucus expanded his control to encompass western Anatolia. He hoped further to take control of Lysimachus's lands in Europe – primarily Thrace and even Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedonia itself, but was assassinated by Ptolemy Ceraunus on landing in Europe.

His son and successor, Antiochus I Soter, was left with an enormous realm consisting of nearly all of the Asian portions of the Empire, but faced with Antigonus II Gonatas in Macedonia and Ptolemy II Philadelphus in Egypt, he proved unable to pick up where his father had left off in conquering the European portions of Alexander's empire.

Breakup of Central Asian territories

Antiochus I Soter, Antiochus I (reigned 281–261 BC) and his son and successor Antiochus II Theos (reigned 261–246 BC) were faced with challenges in the west, including repeated wars with Ptolemy II of Egypt, Ptolemy II and a Celtic invasion of Asia Minor—distracting attention from holding the eastern portions of the Empire together. Towards the end of Antiochus II's reign, various provinces simultaneously asserted their independence, such as Bactria and Sogdiana under Diodotus of Bactria, Diodotus, Cappadocia under Ariarathes III of Cappadocia, Ariarathes III, and Parthia under Andragoras (Seleucid satrap), Andragoras. A few years later, the last was defeated and killed by the invading Parni of Arsaces I of Parthia, Arsaces – the region would then become the core of the Parthian Empire.

Diodotus of Bactria, Diodotus, governor for the Bactrian territory, asserted independence in around 245 BC, although the exact date is far from certain, to form the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. This kingdom was characterized by a rich Hellenistic culture and was to continue its domination of Bactria until around 125 BC when it was overrun by the invasion of northern nomads. One of the Greco-Bactrian kings, Demetrius I of Bactria, invaded India around 180 BC to form the Indo-Greek Kingdoms.

The rulers of Persis, called Fratarakas, also seem to have established some level of independence from the Seleucids during the 3rd century BC, especially from the time of Vahbarz. They would later overtly take the title of Kings of Persis, before becoming vassals to the newly formed Parthian Empire.

The Seleucid satrap of Parthia, named Andragoras (3rd century BC), Andragoras, first claimed independence, in a parallel to the secession of his Bactrian neighbour. Soon after, however, a Parthian tribal chief called Arsaces I of Parthia, Arsaces Parni conquest of Parthia, invaded the Parthian territory around 238 BC to form the Parthian Empire, Arsacid dynasty, from which the Parthian Empire originated.

Antiochus II's son Seleucus II Callinicus came to the throne around 246 BC. Seleucus II was soon dramatically defeated in the Third Syrian War against Ptolemy III of Egypt and then had to fight a civil war against his own brother Antiochus Hierax. Taking advantage of this distraction, Bactria and Parthia seceded from the empire. In Asia Minor too, the Seleucid dynasty seemed to be losing control: the Gauls had fully established themselves in Galatia, semi-independent semi-Hellenized kingdoms had sprung up in Bithynia, Pontus (region), Pontus, and Cappadocia, and the city of Kingdom of Pergamon, Pergamum in the west was asserting its independence under the Attalid Dynasty. The Seleucid economy started to show the first signs of weakness, as Galatians gained independence and Pergamum took control of coastal cities in Anatolia. Consequently, they managed to partially block contact with the West.

Antiochus I Soter, Antiochus I (reigned 281–261 BC) and his son and successor Antiochus II Theos (reigned 261–246 BC) were faced with challenges in the west, including repeated wars with Ptolemy II of Egypt, Ptolemy II and a Celtic invasion of Asia Minor—distracting attention from holding the eastern portions of the Empire together. Towards the end of Antiochus II's reign, various provinces simultaneously asserted their independence, such as Bactria and Sogdiana under Diodotus of Bactria, Diodotus, Cappadocia under Ariarathes III of Cappadocia, Ariarathes III, and Parthia under Andragoras (Seleucid satrap), Andragoras. A few years later, the last was defeated and killed by the invading Parni of Arsaces I of Parthia, Arsaces – the region would then become the core of the Parthian Empire.

Diodotus of Bactria, Diodotus, governor for the Bactrian territory, asserted independence in around 245 BC, although the exact date is far from certain, to form the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. This kingdom was characterized by a rich Hellenistic culture and was to continue its domination of Bactria until around 125 BC when it was overrun by the invasion of northern nomads. One of the Greco-Bactrian kings, Demetrius I of Bactria, invaded India around 180 BC to form the Indo-Greek Kingdoms.

The rulers of Persis, called Fratarakas, also seem to have established some level of independence from the Seleucids during the 3rd century BC, especially from the time of Vahbarz. They would later overtly take the title of Kings of Persis, before becoming vassals to the newly formed Parthian Empire.

The Seleucid satrap of Parthia, named Andragoras (3rd century BC), Andragoras, first claimed independence, in a parallel to the secession of his Bactrian neighbour. Soon after, however, a Parthian tribal chief called Arsaces I of Parthia, Arsaces Parni conquest of Parthia, invaded the Parthian territory around 238 BC to form the Parthian Empire, Arsacid dynasty, from which the Parthian Empire originated.

Antiochus II's son Seleucus II Callinicus came to the throne around 246 BC. Seleucus II was soon dramatically defeated in the Third Syrian War against Ptolemy III of Egypt and then had to fight a civil war against his own brother Antiochus Hierax. Taking advantage of this distraction, Bactria and Parthia seceded from the empire. In Asia Minor too, the Seleucid dynasty seemed to be losing control: the Gauls had fully established themselves in Galatia, semi-independent semi-Hellenized kingdoms had sprung up in Bithynia, Pontus (region), Pontus, and Cappadocia, and the city of Kingdom of Pergamon, Pergamum in the west was asserting its independence under the Attalid Dynasty. The Seleucid economy started to show the first signs of weakness, as Galatians gained independence and Pergamum took control of coastal cities in Anatolia. Consequently, they managed to partially block contact with the West.

Revival (223–191 BC)

A revival would begin when Seleucus II's younger son,

A revival would begin when Seleucus II's younger son, Antiochus III the Great

Antiochus III the Great (; grc-gre, Ἀντίoχoς Μέγας ; c. 2413 July 187 BC) was a Greek Hellenistic king and the 6th ruler of the Seleucid Empire, reigning from 222 to 187 BC. He ruled over the region of Syria and large parts of the res ...

, took the throne in 223 BC. Although initially unsuccessful in the Fourth Syrian War against Egypt, which led to a defeat at the Battle of Raphia (217 BC), Antiochus would prove himself to be the greatest of the Seleucid rulers after Seleucus I himself. He spent the next ten years on his wikt:anabasis, anabasis (journey) through the eastern parts of his domain and restoring rebellious vassals like Parthia and Greco-Bactria to at least nominal obedience. He gained many victories such as the Battle of Mount Labus and Battle of the Arius and Siege of Bactra, besieged the Bactrian capital. He even emulated Seleucus with an expedition into India where he met with King Sophagasenus (Sanskrit: ''Subhagasena'') receiving war elephants, perhaps in accordance of the existing treaty and alliance set after the Seleucid-Mauryan War.

Actual translation of Polybius 11.34 (No other source except Polybius makes any reference to Sophagasenus):

When he returned to the west in 205 BC, Antiochus found that with the death of Ptolemy IV, the situation now looked propitious for another western campaign. Antiochus and Philip V of Macedon then made a pact to divide the Ptolemaic possessions outside of Egypt, and in the Fifth Syrian War, the Seleucids ousted Ptolemy V from control of Coele-Syria. The Battle of Panium (200 BC) definitively transferred these holdings from the Ptolemies to the Seleucids. Antiochus appeared, at the least, to have restored the Seleucid Kingdom to glory.

Expansion into Greece and war with Rome

Following the defeat of his erstwhile ally Philip V of Macedon, Philip by Rome in 197 BC, Antiochus saw the opportunity for expansion into Greece itself. Encouraged by the exiled Carthage, Carthaginian general Hannibal, and making an alliance with the disgruntled Aetolian League, Antiochus launched an invasion across the Hellespont. With his huge army he aimed to establish the Seleucid empire as the foremost power in the Hellenic world, but these plans put the empire on a collision course with the new rising power of the Mediterranean, the

Following the defeat of his erstwhile ally Philip V of Macedon, Philip by Rome in 197 BC, Antiochus saw the opportunity for expansion into Greece itself. Encouraged by the exiled Carthage, Carthaginian general Hannibal, and making an alliance with the disgruntled Aetolian League, Antiochus launched an invasion across the Hellespont. With his huge army he aimed to establish the Seleucid empire as the foremost power in the Hellenic world, but these plans put the empire on a collision course with the new rising power of the Mediterranean, the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

. At the battles of Battle of Thermopylae (191 BC), Thermopylae (191 BC) and Battle of Magnesia, Magnesia (190 BC), Antiochus's forces suffered resounding defeats, and he was compelled to make peace and sign the Treaty of Apamea (188 BC), the main clause of which saw the Seleucids agree to pay a large indemnity, to retreat from Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

and to never again attempt to expand Seleucid territory west of the Taurus Mountains

The Taurus Mountains ( Turkish: ''Toros Dağları'' or ''Toroslar'') are a mountain complex in southern Turkey, separating the Mediterranean coastal region from the central Anatolian Plateau. The system extends along a curve from Lake Eğird ...

. The Kingdom of Pergamum and the Rhodes#Hellenistic and Roman periods, Republic of Rhodes, Rome's allies in the war, gained the former Seleucid lands in Anatolia. Antiochus died in 187 BC on another expedition to the east, where he sought to extract money to pay the indemnity.

Roman power, Parthia and Judea

The reign of his son and successor Seleucus IV Philopator (187–175 BC) was largely spent in attempts to pay the large indemnity, and Seleucus was ultimately assassinated by his minister Heliodorus (minister), Heliodorus.

Seleucus' younger brother, Antiochus IV Epiphanes, now seized the throne. He attempted to restore Seleucid power and prestige with a successful war against the old enemy, Ptolemaic Egypt, which met with initial success as the Seleucids defeated and drove the Egyptian army back to Alexandria itself. As the king planned on how to conclude the war, he was informed that Roman commissioners, led by the Proconsul Gaius Popillius Laenas, were near and requesting a meeting with the Seleucid king. Antiochus agreed, but when they met and Antiochus held out his hand in friendship, Popilius placed in his hand the tablets on which was written the decree of the senate and told him to read it. The decree demanded that he should abort his attack on Alexandria and immediately stop waging the war on Ptolemy. When the king said that he would call his friends into council and consider what he ought to do, Popilius drew a circle in the sand around the king's feet with the stick he was carrying and said, "Before you step out of that circle give me a reply to lay before the senate." For a few moments he hesitated, astounded at such a peremptory order, and at last replied, "I will do what the senate thinks right." He then chose to withdraw rather than set the empire to war with Rome again.

On his return journey, according to Josephus, he made an expedition to Judea, took Jerusalem by force, slew a great many who had favored Ptolemaic Egypt, Ptolemy, sent his soldiers to plunder them without mercy. He also spoiled the Second temple, temple, and interrupted the constant practice of offering a daily sacrifice of expiation, for three years and six months.

The latter part of his reign saw a further disintegration of the Empire despite his best efforts. Weakened economically, militarily and by loss of prestige, the Empire became vulnerable to rebels in the eastern areas of the empire, who began to further undermine the empire while the Parthians moved into the power vacuum to take over the old Persian lands. Antiochus' aggressive Hellenizing (or de-Judaizing) activities provoked a full scale armed rebellion in Judea—the Maccabean Revolt. Efforts to deal with both the Parthians and the Jews as well as retain control of the provinces at the same time proved beyond the weakened empire's power. Antiochus died during a military expedition against the Parthians in 164 BC.

The reign of his son and successor Seleucus IV Philopator (187–175 BC) was largely spent in attempts to pay the large indemnity, and Seleucus was ultimately assassinated by his minister Heliodorus (minister), Heliodorus.

Seleucus' younger brother, Antiochus IV Epiphanes, now seized the throne. He attempted to restore Seleucid power and prestige with a successful war against the old enemy, Ptolemaic Egypt, which met with initial success as the Seleucids defeated and drove the Egyptian army back to Alexandria itself. As the king planned on how to conclude the war, he was informed that Roman commissioners, led by the Proconsul Gaius Popillius Laenas, were near and requesting a meeting with the Seleucid king. Antiochus agreed, but when they met and Antiochus held out his hand in friendship, Popilius placed in his hand the tablets on which was written the decree of the senate and told him to read it. The decree demanded that he should abort his attack on Alexandria and immediately stop waging the war on Ptolemy. When the king said that he would call his friends into council and consider what he ought to do, Popilius drew a circle in the sand around the king's feet with the stick he was carrying and said, "Before you step out of that circle give me a reply to lay before the senate." For a few moments he hesitated, astounded at such a peremptory order, and at last replied, "I will do what the senate thinks right." He then chose to withdraw rather than set the empire to war with Rome again.

On his return journey, according to Josephus, he made an expedition to Judea, took Jerusalem by force, slew a great many who had favored Ptolemaic Egypt, Ptolemy, sent his soldiers to plunder them without mercy. He also spoiled the Second temple, temple, and interrupted the constant practice of offering a daily sacrifice of expiation, for three years and six months.

The latter part of his reign saw a further disintegration of the Empire despite his best efforts. Weakened economically, militarily and by loss of prestige, the Empire became vulnerable to rebels in the eastern areas of the empire, who began to further undermine the empire while the Parthians moved into the power vacuum to take over the old Persian lands. Antiochus' aggressive Hellenizing (or de-Judaizing) activities provoked a full scale armed rebellion in Judea—the Maccabean Revolt. Efforts to deal with both the Parthians and the Jews as well as retain control of the provinces at the same time proved beyond the weakened empire's power. Antiochus died during a military expedition against the Parthians in 164 BC.

Civil war and further decay

After the death of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, the Seleucid Empire became increasingly unstable. Frequent civil wars made central authority tenuous at best. Epiphanes' young son, Antiochus V Eupator, was first overthrown by Seleucus IV's son, Demetrius I Soter in 161 BC. Demetrius I attempted to restore Seleucid power in Judea particularly, but was overthrown in 150 BC by

After the death of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, the Seleucid Empire became increasingly unstable. Frequent civil wars made central authority tenuous at best. Epiphanes' young son, Antiochus V Eupator, was first overthrown by Seleucus IV's son, Demetrius I Soter in 161 BC. Demetrius I attempted to restore Seleucid power in Judea particularly, but was overthrown in 150 BC by Alexander Balas

Alexander I Theopator Euergetes, surnamed Balas ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος Βάλας, Alexandros Balas), was the ruler of the Seleucid Empire from 150/Summer 152 – August 145 BC. Picked from obscurity and supported by the neighboring Roman ...

– an impostor who (with Egyptian backing) claimed to be the son of Epiphanes. Alexander Balas reigned until 145 BC when he was overthrown by Demetrius I's son, Demetrius II Nicator. Demetrius II proved unable to control the whole of the kingdom, however. While he ruled Babylonia and eastern Syria from Damascus, the remnants of Balas' supporters – first supporting Balas' son Antiochus VI, then the usurping general Diodotus Tryphon – held out in Antioch.

Meanwhile, the decay of the Empire's territorial possessions continued apace. By 143 BC, the Ancient Israel, Jews in the form of the Maccabees had fully established their independence. Parthian Empire, Parthian expansion continued as well. In 139 BC, Demetrius II was defeated in battle by the Parthians and was captured. By this time, the entire Iranian Plateau had been lost to Parthian control.

Demetrius Nicator's brother, Antiochus VII Sidetes, took the throne after his brother's capture. He faced the enormous task of restoring a rapidly crumbling empire, one facing threats on multiple fronts. Hard-won control of Coele-Syria was threatened by the Jewish Maccabee rebels. Once-vassal dynasties in Armenia, Cappadocia, and Pontus were threatening Syria and northern Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

; the nomadic Parthians, brilliantly led by Mithridates I of Parthia, had overrun upland Media (home of the famed Nisean horse herd); and Roman intervention was an ever-present threat. Sidetes managed to bring the Maccabees to heel and frighten the Anatolian dynasts into a temporary submission; then, in 133, he turned east with the full might of the Royal Army (supported by a body of Jews under the Hasmonean prince, John Hyrcanus) to drive back the Parthians.

Sidetes' campaign initially met with spectacular success, recapturing Mesopotamia, Babylonia, and Media. In the winter of 130/129 BC, his army was scattered in winter quarters throughout Media and Persis when the Parthian king, Phraates II, counter-attacked. Moving to intercept the Parthians with only the troops at his immediate disposal, he was ambushed and killed at the Battle of Ecbatana in 129 BC. Antiochus Sidetes is sometimes called the last great Seleucid king.

After the death of Antiochus VII Sidetes, all of the recovered eastern territories were recaptured by the Parthians. The Maccabees again rebelled, civil war soon tore the empire to pieces, and the Armenians began to encroach on Syria from the north.

Collapse (100–63 BC)

Tigranes the Great

Tigranes II, more commonly known as Tigranes the Great ( hy, Տիգրան Մեծ, ''Tigran Mets''; grc, Τιγράνης ὁ Μέγας ''Tigránes ho Mégas''; la, Tigranes Magnus) (140 – 55 BC) was King of Armenia under whom the ...

, king of Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ' ...

, however, saw opportunity for expansion in the constant civil strife to the south. In 83 BC, at the invitation of one of the factions in the interminable civil wars, he invaded Syria and soon established himself as ruler of Syria, putting the Seleucid Empire virtually at an end.

Seleucid rule was not entirely over, however. Following the Roman general Lucullus' defeat of both Mithridates and Tigranes in 69 BC, a rump Seleucid kingdom was restored under Antiochus XIII. Even so, civil wars could not be prevented, as another Seleucid, Philip II Philoromaeus, Philip II, contested rule with Antiochus. After the Roman conquest of Pontus, the Romans became increasingly alarmed at the constant source of instability in Syria under the Seleucids. Once Mithridates was defeated by Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a leading Roman general and statesman. He played a significant role in the transformation of ...

in 63 BC, Pompey set about the task of remaking the Hellenistic East, by creating new client kingdoms and establishing provinces. While client nations like Armenia and Judea were allowed to continue with some degree of autonomy under local kings, Pompey saw the Seleucids as too troublesome to continue; doing away with both rival Seleucid princes, he made Syria (Roman province), Syria into a Roman province.

Culture

The domain of the Seleucids stretched from the Aegean Sea to what is now History of Afghanistan, Afghanistan andPakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 243 million people, and has the world's second-lar ...

, therefore including a diverse array of cultures and ethnic groups. Greeks, Assyrian people, Assyrians, Armenians, Georgians, Persian people, Persians, Medes, Mesopotamians, Jews, and more all lived within its bounds. The immense size of the empire gave the Seleucid rulers a difficult balancing act to maintain order, resulting in a mixture of concessions to local cultures to maintain their own practices while also firmly controlling and unifying local elites under the Seleucid banner.

The government established Greek cities and settlements throughout the empire via a program of colonization that encouraged immigration from Macedonia and Greece; both city settlements as well as rural ones were created that were inhabited by ethnic Greeks. These Greeks were given good land and privileges, and in exchange were expected to serve in military service for the state. Despite being a tiny minority of the overall population, these Greeks were the backbone of the empire: loyal and committed to a cause that gave them vast territory to rule, they overwhelmingly served in the military and government. Unlike Ptolemaic Egypt, Greeks in the Seleucid Empire seem to rarely have engaged in mixed marriages with non-Greeks; they kept to their own cities.

The various non-Greek peoples of the empire were still influenced by the spread of Greek thought and culture, a phenomenon referred to as Hellenization. Historically significant towns and cities, such as Antioch, were created or renamed with Greek names, and hundreds of new cities were established for trade purposes and built in Greek style from the start. Local educated elites who needed to work with the government learned the Greek language, wrote in Greek, absorbed Greek philosophical ideas, and took on Greek names; some of these practices then slowly filtered down to the lower classes. Hellenic ideas began an almost 250-year expansion into the Near East, Middle East, and Central Asian cultures.

Synthesizing Hellenic and indigenous cultural, religious, and philosophical ideas met with varying degrees of success. The result was times of simultaneous peace and rebellion in various parts of the empire. In general, the Seleucids allowed local religions to operate undisturbed, such as incorporating Babylonian religion, Babylonian religious tenets to gain support. However, a rare exception proved one of the most heavily documented parts of Seleucid history: the Maccabean Revolt in Judea. While most Seleucid governments had ignored Judaism, under King Antiochus IV the government rather uncharacteristically banned and restricted its practice after a period of favoritism and apparently selling the List of High Priests of Israel, High Priest position to the highest bidder. The result was the eventual loss of control of Judea to an independent Hasmonean kingdom, proving the wisdom of the usual policy of not overly interfering with local religious practice.

Military

As with the other major Hellenistic armies, the Seleucid army fought primarily in the Greco-Macedonian style, with its main body being the Phalanx formation, phalanx. The phalanx was a large, dense formation of men armed with small shields and a long pike called the ''sarissa''. This form of fighting had been developed by the Ancient Macedonian army, Macedonian army in the reign of Philip II of Macedon and his son Alexander the Great. Alongside the phalanx, the Seleucid armies used a great deal of native and mercenary troops to supplement their Greek forces, which were limited due to the distance from the Seleucid rulers' Macedonian homeland. The size of the Seleucid army usually varied between 70,000 and 200,000 in manpower.

The distance from Greece put a strain on the Seleucid military system, as it was primarily based around the recruitment of Greeks as the key segment of the army. In order to increase the population of Greeks in their kingdom, the Seleucid rulers created military settlements. There were two main periods in the establishment of settlements, firstly under

As with the other major Hellenistic armies, the Seleucid army fought primarily in the Greco-Macedonian style, with its main body being the Phalanx formation, phalanx. The phalanx was a large, dense formation of men armed with small shields and a long pike called the ''sarissa''. This form of fighting had been developed by the Ancient Macedonian army, Macedonian army in the reign of Philip II of Macedon and his son Alexander the Great. Alongside the phalanx, the Seleucid armies used a great deal of native and mercenary troops to supplement their Greek forces, which were limited due to the distance from the Seleucid rulers' Macedonian homeland. The size of the Seleucid army usually varied between 70,000 and 200,000 in manpower.

The distance from Greece put a strain on the Seleucid military system, as it was primarily based around the recruitment of Greeks as the key segment of the army. In order to increase the population of Greeks in their kingdom, the Seleucid rulers created military settlements. There were two main periods in the establishment of settlements, firstly under Seleucus I Nicator

Seleucus I Nicator (; ; grc-gre, Σέλευκος Νικάτωρ , ) was a Macedonian Greek general who was an officer and successor ( ''diadochus'') of Alexander the Great. Seleucus was the founder of the eponymous Seleucid Empire. In the po ...

and Antiochus I Soter and then under Antiochus IV Epiphanes. The military settlers were given land, "varying in size according to rank and arm of service'. They were settled in 'colonies of an urban character, which at some point could acquire the status of a polis". Unlike the Ptolemaic military settlers, who were known as ''Kleruchoi'', the Seleucid settlers were called ''Katoikoi''. The settlers would maintain the land as their own and in return, they would serve in the Seleucid army when called. The majority of settlements were concentrated in Lydia, northern Syria, the upper Euphrates and Medes, Media. The Greeks were dominant in Lydia, Phrygia and Syria. For example, Antiochus III brought Greeks from Euboea, Crete and Aetolia and settled them in Antioch.