Samaritan Pentateuch (detail).jpg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Samaritan Torah (Samaritan Hebrew: , ''Tōrāʾ''), also called the Samaritan Pentateuch, is a text of the Torah written in the Samaritan script and used as Religious text, sacred scripture by the Samaritans. It dates back to one of the ancient versions of the Hebrew Bible that existed during the Second Temple period, and constitutes the entire biblical canon in Samaritanism.

Some six thousand differences exist between the Samaritan and the Masoretic Text, Jewish Masoretic Text. Most are minor variations in the spelling of words or Grammatical construction, grammatical constructions, but others involve significant semantic changes, such as the uniquely Samaritan commandment to construct an altar on Mount Gerizim. Nearly two thousand of these textual variations agree with the Koine Greek Septuagint and some are shared with the Vulgate, Latin Vulgate. Throughout their history, Samaritans have made use of translations of the Samaritan Pentateuch into Aramaic language, Aramaic, Greek, and Arabic, as well as Liturgy, liturgical and Exegesis, exegetical works based upon it.

It first became known to the Western world in 1631, proving the first example of the Samaritan script, Samaritan alphabet and sparking an intense theological debate regarding its relative age versus the Masoretic Text. This first published copy, much later labelled as Codex B by :de:August von Gall, August von Gall, became the source of most Western Textual criticism, critical editions of the Samaritan Pentateuch until the latter half of the 20th century; today the codex is held in the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Some Pentateuchal manuscripts discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls have been identified as bearing a "pre-Samaritan" text type.''The Canon Debate'', McDonald & Sanders editors, 2002, chapter 6: ''Questions of Canon through the Dead Sea Scrolls'' by James C. VanderKam, page 94, citing private communication with Emanuel Tov on ''biblical manuscripts'': Qumran scribe type c. 25%, proto-Masoretic Text c. 40%, pre-Samaritan texts c. 5%, texts close to the Hebrew model for the Septuagint c. 5% and nonaligned c. 25%.

The Samaritan Torah (Samaritan Hebrew: , ''Tōrāʾ''), also called the Samaritan Pentateuch, is a text of the Torah written in the Samaritan script and used as Religious text, sacred scripture by the Samaritans. It dates back to one of the ancient versions of the Hebrew Bible that existed during the Second Temple period, and constitutes the entire biblical canon in Samaritanism.

Some six thousand differences exist between the Samaritan and the Masoretic Text, Jewish Masoretic Text. Most are minor variations in the spelling of words or Grammatical construction, grammatical constructions, but others involve significant semantic changes, such as the uniquely Samaritan commandment to construct an altar on Mount Gerizim. Nearly two thousand of these textual variations agree with the Koine Greek Septuagint and some are shared with the Vulgate, Latin Vulgate. Throughout their history, Samaritans have made use of translations of the Samaritan Pentateuch into Aramaic language, Aramaic, Greek, and Arabic, as well as Liturgy, liturgical and Exegesis, exegetical works based upon it.

It first became known to the Western world in 1631, proving the first example of the Samaritan script, Samaritan alphabet and sparking an intense theological debate regarding its relative age versus the Masoretic Text. This first published copy, much later labelled as Codex B by :de:August von Gall, August von Gall, became the source of most Western Textual criticism, critical editions of the Samaritan Pentateuch until the latter half of the 20th century; today the codex is held in the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Some Pentateuchal manuscripts discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls have been identified as bearing a "pre-Samaritan" text type.''The Canon Debate'', McDonald & Sanders editors, 2002, chapter 6: ''Questions of Canon through the Dead Sea Scrolls'' by James C. VanderKam, page 94, citing private communication with Emanuel Tov on ''biblical manuscripts'': Qumran scribe type c. 25%, proto-Masoretic Text c. 40%, pre-Samaritan texts c. 5%, texts close to the Hebrew model for the Septuagint c. 5% and nonaligned c. 25%.

Samaritans believe that God authored their Pentateuch and gave Moses the first copy along with the Tablets of Stone, two tablets containing the Ten Commandments.Gaster, T.H. "Samaritans," pp. 190–197 in ''Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible, Volume 4''. George Arthur Buttrick, gen. ed. Nashville: Abingdon, 1962. They believe that they preserve this divinely composed text uncorrupted to the present day. Samaritans commonly refer to their Pentateuch as (''Qushta'', Aramaic for "Truth").

Samaritans include only the Pentateuch in their biblical canon. They do not recognize Authorship of the Bible#Divine authorship, divine authorship or Biblical inspiration, inspiration in any other book in the Jewish Tanakh. A Book of Joshua (Samaritan), Samaritan Book of Joshua partly based upon the Tanakh's Book of Joshua exists, but Samaritans regard it as a non-canonical secular historical chronicle.

According to a view based on the biblical Book of Ezra (), the Samaritans are the people of Samaria who parted ways with the people of Kingdom of Judah, Judah (the Judahites) in the Yehud Medinata, Persian period.Tov 2001, pp. 82–83

Samaritans believe that God authored their Pentateuch and gave Moses the first copy along with the Tablets of Stone, two tablets containing the Ten Commandments.Gaster, T.H. "Samaritans," pp. 190–197 in ''Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible, Volume 4''. George Arthur Buttrick, gen. ed. Nashville: Abingdon, 1962. They believe that they preserve this divinely composed text uncorrupted to the present day. Samaritans commonly refer to their Pentateuch as (''Qushta'', Aramaic for "Truth").

Samaritans include only the Pentateuch in their biblical canon. They do not recognize Authorship of the Bible#Divine authorship, divine authorship or Biblical inspiration, inspiration in any other book in the Jewish Tanakh. A Book of Joshua (Samaritan), Samaritan Book of Joshua partly based upon the Tanakh's Book of Joshua exists, but Samaritans regard it as a non-canonical secular historical chronicle.

According to a view based on the biblical Book of Ezra (), the Samaritans are the people of Samaria who parted ways with the people of Kingdom of Judah, Judah (the Judahites) in the Yehud Medinata, Persian period.Tov 2001, pp. 82–83

The Samaritans believe that it was not they, but the Jews, who separated from the authentic stream of the Israelites, Israelite tradition and law, around the time of Eli (biblical figure), Eli, in the 11th century BCE. Jews have traditionally connected the origin of the Samaritans with the later events described in claiming that the Samaritans are not related to the Israelites, but to those brought to Samaria by the Assyrians.

Manuscripts of the Samaritan Pentateuch are written in a different script than the one used in the Masoretic Text, Masoretic Pentateuch, used by Jews. The Samaritan text is written with the Samaritan alphabet, derived from the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet used by the Israelite community prior to the Babylonian captivity. During the exile in Babylon, Jews adopted the Ktav Ashuri, Ashuri script, based on the Babylonians' Aramaic alphabet, which was developed into the modern Hebrew alphabet. Originally, all manuscripts of the Samaritan Pentateuch consisted of unvocalized text written using only the letters of the Samaritan alphabet. Beginning in the 12th century, some manuscripts show a partial vocalization resembling the Jewish Tiberian vocalization used in Masoretic manuscripts. More recently, manuscripts have been produced with full vocalization. The Samaritan Pentateuchal text is divided into 904 paragraphs. Divisions between sections of text are marked with various combinations of lines, dots or an asterisk; a dot is used to indicate the separation between words.

The Polyglot (book)#London Polyglot, ''London Polyglot'' lists six thousand instances where the Samaritan Pentateuch differs from the Masoretic (Jewish) text.Hjelm 2000, p. 77

Manuscripts of the Samaritan Pentateuch are written in a different script than the one used in the Masoretic Text, Masoretic Pentateuch, used by Jews. The Samaritan text is written with the Samaritan alphabet, derived from the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet used by the Israelite community prior to the Babylonian captivity. During the exile in Babylon, Jews adopted the Ktav Ashuri, Ashuri script, based on the Babylonians' Aramaic alphabet, which was developed into the modern Hebrew alphabet. Originally, all manuscripts of the Samaritan Pentateuch consisted of unvocalized text written using only the letters of the Samaritan alphabet. Beginning in the 12th century, some manuscripts show a partial vocalization resembling the Jewish Tiberian vocalization used in Masoretic manuscripts. More recently, manuscripts have been produced with full vocalization. The Samaritan Pentateuchal text is divided into 904 paragraphs. Divisions between sections of text are marked with various combinations of lines, dots or an asterisk; a dot is used to indicate the separation between words.

The Polyglot (book)#London Polyglot, ''London Polyglot'' lists six thousand instances where the Samaritan Pentateuch differs from the Masoretic (Jewish) text.Hjelm 2000, p. 77

As different printed editions of the Samaritan Pentateuch are based upon different sets of manuscripts, the precise number varies significantly from one edition to another.Purvis, J.D. "Samaritan Pentateuch," pp. 772–775 in ''Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible, Supplementary Volume''. Keith Crim, gen. ed. Nashville: Abingdon, 1976. Only a minority of such differences are significant. Most are simply spelling differences, usually concerning Hebrew letters of similar appearance; the use of more ''Mater lectionis, matres lectionis'' (symbols indicating vowels) in the Samaritan Pentateuch, compared with the Masoretic; different placement of words in a sentence; and the replacement of some verbal constructions with equivalent ones.Vanderkam 2002, p. 93

A comparison between both versions shows a preference in the Samaritan version for the Hebrew Preposition and postposition, preposition ''al'' where the Masoretic text has ''el''. The most notable substantial differences between both texts are those related to Mount Gerizim, the Samaritans' place of worship. The Samaritan version of the Ten Commandments includes the command that an altar be built on Mount Gerizim on which all sacrifices should be offered. "But there is at least one case, Deut.27.4–7, in which the reading 'Gerizim' in the Samaritan Pentateuch, confirmed by Σ and by the Old Latin, seems to be preferable to that of the Massoretic text, which has Ebal, the other mountain standing above Nablus." The Samaritan Pentateuch contains the following paragraph, which is absent from the Jewish version: Another important difference between the Samaritan Torah and the Jewish (Masoretic) Torah is in . According to the Jewish text, the Israelites were told to enter the Promised Land and build an altar on Mount Ebal, while the Samaritan text says that such altar, the first built by the Israelites in the Promised Land, should be built on Mount Gerizim. A few verses afterwards, both the Jewish and the Samaritan texts contain instructions for the Israelites to perform two ceremonies upon entering the Promised Land: one of blessings, to be held on Mount Gerizim, and one of cursings, to take place on Mount Ebal. In 1946, the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered, which include the oldest known versions of the Torah. In , the Dead Sea scroll fragments bring "Gerizim" instead of "Ebal", indicating that the Samaritan version was likely the original reading. A newly published Dead Sea Scroll fragment of Deuteronomy has "Gerizim" instead of "Ebal" in Deuteronomy 27:4. Other differences between the Samaritan and the Masoretic (Jewish) texts include: In , the Samaritan Pentateuch refers to Moses' Zipporah, wife as "''kaashet''", which translates as "the beautiful woman", while the Jewish version and the Jewish commentaries suggest that the word used was "''Kushi''", meaning "black woman" or "Cushitic languages, Cushite woman." For the Samaritans, therefore, Moses had only one wife, Zipporah, throughout his whole life, while Jewish sources generally understand that Moses had two wives, Zipporah and a second, unnamed Cushite woman. Several other differences are found. The Samaritan Pentateuch uses less Anthropomorphism, anthropomorphic language in descriptions of God, with intermediaries performing actions that the Jewish version attributes directly to God. Where the Jewish text describes Yahweh as a "man of war" (), the Samaritan has "hero of war", a phrase applied to spiritual beings. In , the Samaritan text reads "The Angel of the Lord, Angel of God found Balaam", in contrast with the Jewish text, which reads "And God met Balaam." In , the Jewish text says that Joseph (Genesis), Joseph's grandchildren were born "upon the knees of Joseph", while the Samaritan text says they were born "in the days of Joseph". In about thirty-four instances, the Samaritan Pentateuch has repetitions in one section of text that was also found in other parts of the Pentateuch. Such repetitions are also implied or presupposed in the Jewish text, but not explicitly recorded in it. For example, the Samaritan text in the Book of Exodus on multiple occasions records Moses repeating to Pharaoh exactly what both God had previously instructed Moses to tell him, which makes the text look repetitious, in comparison with the Jewish text. In other occasions, the Samaritan Pentateuch has subject (grammar), subjects, prepositions, grammatical particle, particles, apposition, appositives, including the repetition of words and phrases within a single passage, that are absent from the Jewish text.

The earliest recorded assessments of the Samaritan Pentateuch are found in rabbinical literature and Church fathers, Christian Patristic writings of the first millennium CE. The Talmud records Jewish Rabbi Eleazar b. Simeon condemning the Samaritan scribes: "You have falsified your Pentateuch...and you have not profited aught by it." Some early Christian writers found the Samaritan Pentateuch useful for textual criticism. Cyril of Alexandria, Procopius of Gaza and others spoke of certain words missing from the Jewish Bible, but present in the Samaritan Pentateuch. Eusebius of Caesarea wrote that the "Greek translation [of the Bible] also differs from the Hebrew, though not so much from the Samaritan" and noted that the Septuagint agrees with the Samaritan Pentateuch in the number of years elapsed from Noah's Flood to Abraham. Christian interest in the Samaritan Pentateuch fell into neglect during the Middle Ages.

The publication of a manuscript of the Samaritan Pentateuch in 17th-century Europe reawakened interest in the text and fueled a controversy between Protestants and Roman Catholics over which Old Testament textual traditions are authoritative. Roman Catholics showed a particular interest in the study of the Samaritan Pentateuch on account of the antiquity of the text and its frequent agreements with the Septuagint and the Latin Vulgate, two Bible translations to which Catholics have traditionally ascribed considerable authority. Some Catholics including Jean Morin (theologian), Jean Morin, a convert from Calvinism to Catholicism, argued that the Samaritan Pentateuch's correspondences with the Latin Vulgate and Septuagint indicated that it represents a more authentic Hebrew text than the Masoretic. Several Protestants replied with a defense of the Masoretic text's authority and argued that the Samaritan text is a late and unreliable derivation from the Masoretic.

The 18th-century Protestant Hebrew scholar Benjamin Kennicott's analysis of the Samaritan Pentateuch stands as a notable exception to the general trend of early Protestant research on the text. He questioned the underlying assumption that the Masoretic text must be more authentic simply because it has been more widely accepted as the authoritative Hebrew version of the Pentateuch:

:"We see then that as the evidence of one text destroys the evidence of the other and as there is in fact the authority of versions to oppose to the authority of versions no certain argument or rather no argument at all can be drawn from hence to fix the corruption on either side".

Kennicott also states that the reading Gerizim may actually be the original reading, since that is the mountain for proclaiming blessings, and that it is very green and rich of vegetation (as opposed to Mt. Ebal, which is barren and the mountain for proclaiming curses) amongst other arguments.

German scholar Wilhelm Gesenius published a study of the Samaritan Pentateuch in 1815 which biblical scholars widely embraced during the next century. He argued that the Septuagint and the Samaritan Pentateuch share a common source in a family of Hebrew manuscripts which he named the "Alexandrino-Samaritanus". In contrast to the proto-Masoretic "Judean" manuscripts carefully preserved and copied in Jerusalem, he regarded the Alexandrino-Samaritanus as having been carelessly handled by scribal copyists who popularized, simplified, and expanded the text. Gesenius concluded that the Samaritan text contained only four valid variants when compared to the Masoretic text.

In 1915, Paul E. Kahle, Paul Kahle published a paper which compared passages from the Samaritan text to Pentateuchal quotations in the New Testament and pseudepigraphal texts including the Book of Jubilees, the First Book of Enoch and the Assumption of Moses. He concluded that the Samaritan Pentateuch preserves "many genuine old readings and an ancient form of the Pentateuch."

Support for Kahle's thesis was bolstered by the discovery of biblical manuscripts among the Dead Sea Scrolls, which contain a text similar to the Samaritan Pentateuch. The Dead Sea Scroll texts have demonstrated that a Pentateuchal text type resembling the Samaritan Pentateuch goes back to the second century BCE and perhaps even earlier.

These discoveries have demonstrated that manuscripts bearing a "pre-Samaritan" text of at least some portions of the Pentateuch such as Book of Exodus, Exodus and Book of Numbers, Numbers circulated alongside other manuscripts with a "pre-Masoretic" text. One Dead Sea Scroll copy of the Book of Exodus, conventionally named 4QpaleoExodm, shows a particularly close relation to the Samaritan Pentateuch:

:The scroll shares all the major typological features with the SP, including all the major expansions of that tradition where it is extant (twelve), with the single exception of the new tenth commandment inserted in Exodus 20 from Deuteronomy 11 and 27 regarding the altar on Mount Gerizim.

Frank Moore Cross has described the origin of the Samaritan Pentateuch within the context of his local texts hypothesis. He views the Samaritan Pentateuch as having emerged from a manuscript tradition local to the Land of Israel. The Hebrew texts that form the underlying basis for the Septuagint branched from the Israelite tradition as Israelites emigrated to Egypt and took copies of the Pentateuch with them. Cross states that the Samaritan and the Septuagint share a nearer common ancestor than either does with the Masoretic, which he suggested developed from local texts used by the Babylonian Jewish community. His explanation accounts for the Samaritan and the Septuagint sharing variants not found in the Masoretic and their differences reflecting the period of their independent development as distinct local text traditions. On the basis of archaizing and pseudo-archaic forms, Cross dates the emergence of the Samaritan Pentateuch as a uniquely Samaritan textual tradition to the post-Maccabees, Maccabean age.

Scholars widely agree that many textual elements previously classified as "Samaritan variants" actually derive from the earlier phases of the Pentateuch's textual history.

Regarding the controversy between the Samaritan and Masoretic versions of , the Dead Sea Scrolls texts agree with the Samaritan version, in that, in them, the Israelites were instructed to build their first altar in the Promised Land on Mount Gerizim, as stated in the Samaritan Torah, and not on Mount Ebal, as stated in the Masoretic text.

The earliest recorded assessments of the Samaritan Pentateuch are found in rabbinical literature and Church fathers, Christian Patristic writings of the first millennium CE. The Talmud records Jewish Rabbi Eleazar b. Simeon condemning the Samaritan scribes: "You have falsified your Pentateuch...and you have not profited aught by it." Some early Christian writers found the Samaritan Pentateuch useful for textual criticism. Cyril of Alexandria, Procopius of Gaza and others spoke of certain words missing from the Jewish Bible, but present in the Samaritan Pentateuch. Eusebius of Caesarea wrote that the "Greek translation [of the Bible] also differs from the Hebrew, though not so much from the Samaritan" and noted that the Septuagint agrees with the Samaritan Pentateuch in the number of years elapsed from Noah's Flood to Abraham. Christian interest in the Samaritan Pentateuch fell into neglect during the Middle Ages.

The publication of a manuscript of the Samaritan Pentateuch in 17th-century Europe reawakened interest in the text and fueled a controversy between Protestants and Roman Catholics over which Old Testament textual traditions are authoritative. Roman Catholics showed a particular interest in the study of the Samaritan Pentateuch on account of the antiquity of the text and its frequent agreements with the Septuagint and the Latin Vulgate, two Bible translations to which Catholics have traditionally ascribed considerable authority. Some Catholics including Jean Morin (theologian), Jean Morin, a convert from Calvinism to Catholicism, argued that the Samaritan Pentateuch's correspondences with the Latin Vulgate and Septuagint indicated that it represents a more authentic Hebrew text than the Masoretic. Several Protestants replied with a defense of the Masoretic text's authority and argued that the Samaritan text is a late and unreliable derivation from the Masoretic.

The 18th-century Protestant Hebrew scholar Benjamin Kennicott's analysis of the Samaritan Pentateuch stands as a notable exception to the general trend of early Protestant research on the text. He questioned the underlying assumption that the Masoretic text must be more authentic simply because it has been more widely accepted as the authoritative Hebrew version of the Pentateuch:

:"We see then that as the evidence of one text destroys the evidence of the other and as there is in fact the authority of versions to oppose to the authority of versions no certain argument or rather no argument at all can be drawn from hence to fix the corruption on either side".

Kennicott also states that the reading Gerizim may actually be the original reading, since that is the mountain for proclaiming blessings, and that it is very green and rich of vegetation (as opposed to Mt. Ebal, which is barren and the mountain for proclaiming curses) amongst other arguments.

German scholar Wilhelm Gesenius published a study of the Samaritan Pentateuch in 1815 which biblical scholars widely embraced during the next century. He argued that the Septuagint and the Samaritan Pentateuch share a common source in a family of Hebrew manuscripts which he named the "Alexandrino-Samaritanus". In contrast to the proto-Masoretic "Judean" manuscripts carefully preserved and copied in Jerusalem, he regarded the Alexandrino-Samaritanus as having been carelessly handled by scribal copyists who popularized, simplified, and expanded the text. Gesenius concluded that the Samaritan text contained only four valid variants when compared to the Masoretic text.

In 1915, Paul E. Kahle, Paul Kahle published a paper which compared passages from the Samaritan text to Pentateuchal quotations in the New Testament and pseudepigraphal texts including the Book of Jubilees, the First Book of Enoch and the Assumption of Moses. He concluded that the Samaritan Pentateuch preserves "many genuine old readings and an ancient form of the Pentateuch."

Support for Kahle's thesis was bolstered by the discovery of biblical manuscripts among the Dead Sea Scrolls, which contain a text similar to the Samaritan Pentateuch. The Dead Sea Scroll texts have demonstrated that a Pentateuchal text type resembling the Samaritan Pentateuch goes back to the second century BCE and perhaps even earlier.

These discoveries have demonstrated that manuscripts bearing a "pre-Samaritan" text of at least some portions of the Pentateuch such as Book of Exodus, Exodus and Book of Numbers, Numbers circulated alongside other manuscripts with a "pre-Masoretic" text. One Dead Sea Scroll copy of the Book of Exodus, conventionally named 4QpaleoExodm, shows a particularly close relation to the Samaritan Pentateuch:

:The scroll shares all the major typological features with the SP, including all the major expansions of that tradition where it is extant (twelve), with the single exception of the new tenth commandment inserted in Exodus 20 from Deuteronomy 11 and 27 regarding the altar on Mount Gerizim.

Frank Moore Cross has described the origin of the Samaritan Pentateuch within the context of his local texts hypothesis. He views the Samaritan Pentateuch as having emerged from a manuscript tradition local to the Land of Israel. The Hebrew texts that form the underlying basis for the Septuagint branched from the Israelite tradition as Israelites emigrated to Egypt and took copies of the Pentateuch with them. Cross states that the Samaritan and the Septuagint share a nearer common ancestor than either does with the Masoretic, which he suggested developed from local texts used by the Babylonian Jewish community. His explanation accounts for the Samaritan and the Septuagint sharing variants not found in the Masoretic and their differences reflecting the period of their independent development as distinct local text traditions. On the basis of archaizing and pseudo-archaic forms, Cross dates the emergence of the Samaritan Pentateuch as a uniquely Samaritan textual tradition to the post-Maccabees, Maccabean age.

Scholars widely agree that many textual elements previously classified as "Samaritan variants" actually derive from the earlier phases of the Pentateuch's textual history.

Regarding the controversy between the Samaritan and Masoretic versions of , the Dead Sea Scrolls texts agree with the Samaritan version, in that, in them, the Israelites were instructed to build their first altar in the Promised Land on Mount Gerizim, as stated in the Samaritan Torah, and not on Mount Ebal, as stated in the Masoretic text.

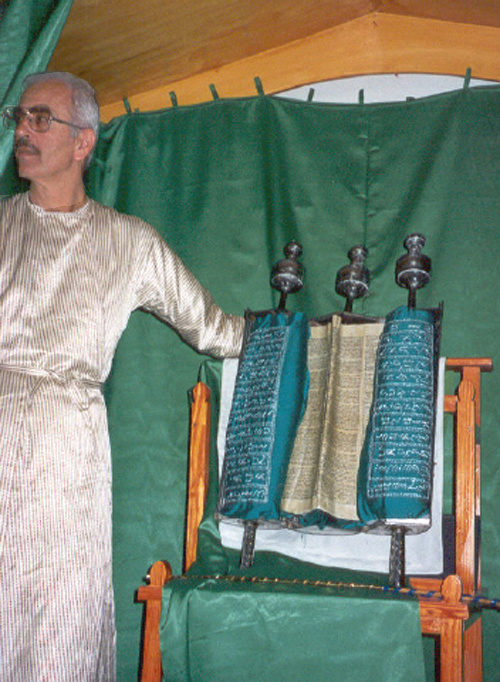

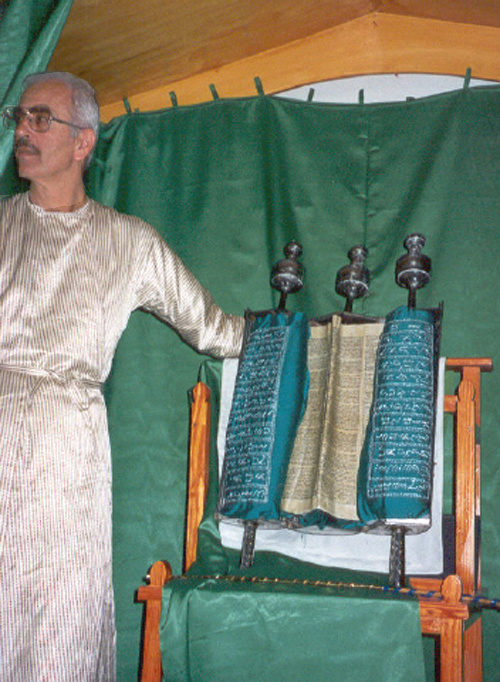

Samaritans attach special importance to the ''Abisha Scroll'' used in the Samaritan synagogue of Nablus. It consists of a continuous length of parchment sewn together from the skins of rams that, according to a Samaritan tradition, were ritually sacrificed. The text is written in gold letters. Rollers tipped with ornamental knobs are attached to both ends of the parchment and the whole is kept in a cylindrical silver case when not in use. Samaritans claim it was penned by Abishua, great-grandson of Aaron (), thirteen years after the entry into the land of Israel under the leadership of Joshua, son of Nun, although contemporary scholars describe it as a composite of several fragmentary scrolls each penned between the 12th and 14th centuries CE. Other manuscripts of the Samaritan Pentateuch consist of vellum or cotton paper written upon with black ink. Numerous manuscripts of the text exist, but none written in the original Hebrew or in translation predates the Middle Ages. The scroll contains a cryptogram, dubbed the ''tashqil'' by scholars, which Samaritans consider to be Abishua's ancient colophon:

Samaritans attach special importance to the ''Abisha Scroll'' used in the Samaritan synagogue of Nablus. It consists of a continuous length of parchment sewn together from the skins of rams that, according to a Samaritan tradition, were ritually sacrificed. The text is written in gold letters. Rollers tipped with ornamental knobs are attached to both ends of the parchment and the whole is kept in a cylindrical silver case when not in use. Samaritans claim it was penned by Abishua, great-grandson of Aaron (), thirteen years after the entry into the land of Israel under the leadership of Joshua, son of Nun, although contemporary scholars describe it as a composite of several fragmentary scrolls each penned between the 12th and 14th centuries CE. Other manuscripts of the Samaritan Pentateuch consist of vellum or cotton paper written upon with black ink. Numerous manuscripts of the text exist, but none written in the original Hebrew or in translation predates the Middle Ages. The scroll contains a cryptogram, dubbed the ''tashqil'' by scholars, which Samaritans consider to be Abishua's ancient colophon:

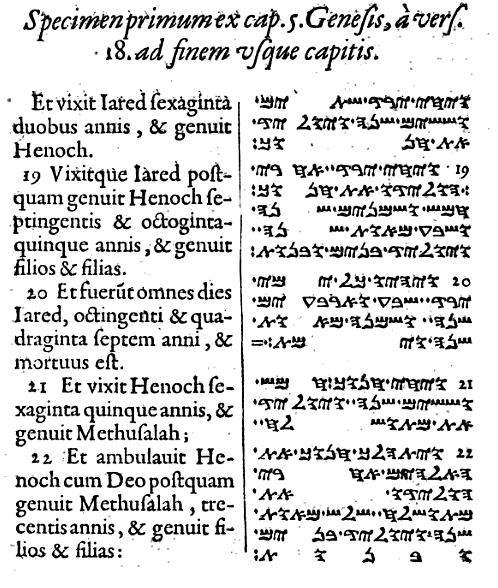

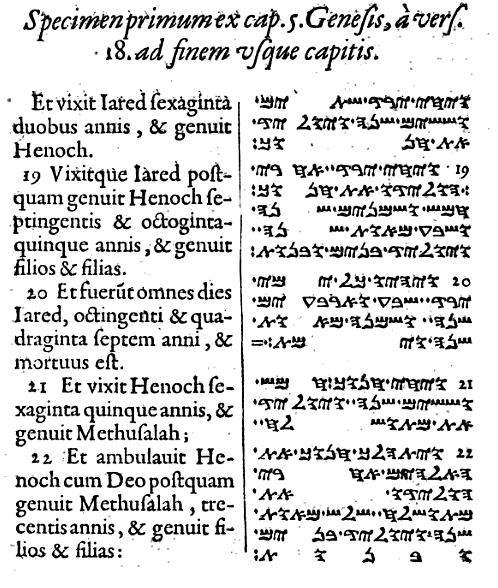

Interest in the Samaritan Pentateuch was awakened in 1616 when the traveler Pietro della Valle purchased a copy of the text in Damascus. This manuscript, now known as Codex B, was deposited in a Parisian library. In 1631, an edited copy of Codex B was published in Le Jay's (Paris) Polyglot by Jean Morin.: "When the Samaritan version of the Pentateuch was revealed to the Western world early in the 17th century... [footnote: 'In 1632 the Frenchman Jean Morin published the Samaritan Pentateuch in the Parisian Biblia Polyglotta based on a manuscript that the traveler Pietro Della Valle had bought from Damascus sixteen years previously.]" It was republished in Walton's Polyglot in 1657. Subsequently, Archbishop Ussher and others procured additional copies which were brought to Europe and later, America.

Interest in the Samaritan Pentateuch was awakened in 1616 when the traveler Pietro della Valle purchased a copy of the text in Damascus. This manuscript, now known as Codex B, was deposited in a Parisian library. In 1631, an edited copy of Codex B was published in Le Jay's (Paris) Polyglot by Jean Morin.: "When the Samaritan version of the Pentateuch was revealed to the Western world early in the 17th century... [footnote: 'In 1632 the Frenchman Jean Morin published the Samaritan Pentateuch in the Parisian Biblia Polyglotta based on a manuscript that the traveler Pietro Della Valle had bought from Damascus sixteen years previously.]" It was republished in Walton's Polyglot in 1657. Subsequently, Archbishop Ussher and others procured additional copies which were brought to Europe and later, America.

and between 1961 and 1965 by A. and R. Sadaqa in ''Jewish and Samaritan Versions of the Pentateuch – With Particular Stress on the Differences Between Both Texts''. In 1976 L.F. Giron-Blanc published Codex Add. 1846, a Samaritan Pentateuch codex dating to 1100 CE in the critical edition ''Pentateuco Hebreo-Samaritano: Génesis'' supplemented with variants found in fifteen previously unpublished manuscripts. Certain recently published critical editions of Pentateuchal books take Samaritan variants into account, including D.L. Phillips' edition of Exodus. The Arabic translation of the Samaritan Pentateuch has been edited and published at the beginning of the 21st century. Several publications containing the text of the Samaritan Targum have appeared. In 1875, the German scholar Adolf Brüll published his ''Das samaritanische Targum zum Pentateuch'' (''The Samaritan Targum to the Pentateuch''). More recently a two volume set edited by Abraham Tal appeared featuring the first critical edition based upon all extant manuscripts containing the Targumic text.

* Shoulson, Mark E, compiler. ''The Torah: Jewish and Samaritan versions compared'' (Hebrew Edition, 2008). Evertype. / . * Schorch, Stefan. ''Die Vokale des Gesetzes: Die samaritanische Lesetradition als Textzeugin der Tora (Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft)'' (German Edition). Pub. Walter de Gruyter (June 3, 2004). / * A.C. Hwiid, Specimen ineditae versionis Arabico-Samaritanae, Pentateuchi e codice manuscripto Bibliothecae Barberinae (Rome, 1780). * A.S. Halkin, “The Scholia to Numbers and Deuteronomy in the Samaritan Arabic Pentateuch,” Jewish Quarterly Review 34 n.s. (1943–44): 41-59. * T.G.J. Juynboll, “Commentatio de versione Arabico-Samaritana, et de scholiis, quae codicibus Parisiensibus n. 2 et 4 adscripta sunt,” Orientalia 2 (1846), pp. 113–157.

Jewish Encyclopedia: Samaritans: Samaritan Version of the Pentateuch

Samaritan Pentateuch Add.1846

nbsp;– digitised version of the earliest complete manuscript of the Samaritan Pentateuch on Cambridge Digital Library {{Authority control 2nd-century BC books Torah Biblical criticism Early versions of the Bible Ancient Jewish literature Jewish prayer and ritual texts Samaritan texts Texts attributed to Moses Ancient Hebrew texts

The Samaritan Torah (Samaritan Hebrew: , ''Tōrāʾ''), also called the Samaritan Pentateuch, is a text of the Torah written in the Samaritan script and used as Religious text, sacred scripture by the Samaritans. It dates back to one of the ancient versions of the Hebrew Bible that existed during the Second Temple period, and constitutes the entire biblical canon in Samaritanism.

Some six thousand differences exist between the Samaritan and the Masoretic Text, Jewish Masoretic Text. Most are minor variations in the spelling of words or Grammatical construction, grammatical constructions, but others involve significant semantic changes, such as the uniquely Samaritan commandment to construct an altar on Mount Gerizim. Nearly two thousand of these textual variations agree with the Koine Greek Septuagint and some are shared with the Vulgate, Latin Vulgate. Throughout their history, Samaritans have made use of translations of the Samaritan Pentateuch into Aramaic language, Aramaic, Greek, and Arabic, as well as Liturgy, liturgical and Exegesis, exegetical works based upon it.

It first became known to the Western world in 1631, proving the first example of the Samaritan script, Samaritan alphabet and sparking an intense theological debate regarding its relative age versus the Masoretic Text. This first published copy, much later labelled as Codex B by :de:August von Gall, August von Gall, became the source of most Western Textual criticism, critical editions of the Samaritan Pentateuch until the latter half of the 20th century; today the codex is held in the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Some Pentateuchal manuscripts discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls have been identified as bearing a "pre-Samaritan" text type.''The Canon Debate'', McDonald & Sanders editors, 2002, chapter 6: ''Questions of Canon through the Dead Sea Scrolls'' by James C. VanderKam, page 94, citing private communication with Emanuel Tov on ''biblical manuscripts'': Qumran scribe type c. 25%, proto-Masoretic Text c. 40%, pre-Samaritan texts c. 5%, texts close to the Hebrew model for the Septuagint c. 5% and nonaligned c. 25%.

The Samaritan Torah (Samaritan Hebrew: , ''Tōrāʾ''), also called the Samaritan Pentateuch, is a text of the Torah written in the Samaritan script and used as Religious text, sacred scripture by the Samaritans. It dates back to one of the ancient versions of the Hebrew Bible that existed during the Second Temple period, and constitutes the entire biblical canon in Samaritanism.

Some six thousand differences exist between the Samaritan and the Masoretic Text, Jewish Masoretic Text. Most are minor variations in the spelling of words or Grammatical construction, grammatical constructions, but others involve significant semantic changes, such as the uniquely Samaritan commandment to construct an altar on Mount Gerizim. Nearly two thousand of these textual variations agree with the Koine Greek Septuagint and some are shared with the Vulgate, Latin Vulgate. Throughout their history, Samaritans have made use of translations of the Samaritan Pentateuch into Aramaic language, Aramaic, Greek, and Arabic, as well as Liturgy, liturgical and Exegesis, exegetical works based upon it.

It first became known to the Western world in 1631, proving the first example of the Samaritan script, Samaritan alphabet and sparking an intense theological debate regarding its relative age versus the Masoretic Text. This first published copy, much later labelled as Codex B by :de:August von Gall, August von Gall, became the source of most Western Textual criticism, critical editions of the Samaritan Pentateuch until the latter half of the 20th century; today the codex is held in the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Some Pentateuchal manuscripts discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls have been identified as bearing a "pre-Samaritan" text type.''The Canon Debate'', McDonald & Sanders editors, 2002, chapter 6: ''Questions of Canon through the Dead Sea Scrolls'' by James C. VanderKam, page 94, citing private communication with Emanuel Tov on ''biblical manuscripts'': Qumran scribe type c. 25%, proto-Masoretic Text c. 40%, pre-Samaritan texts c. 5%, texts close to the Hebrew model for the Septuagint c. 5% and nonaligned c. 25%.

Origin and canonical significance

Samaritan traditions

Samaritans believe that God authored their Pentateuch and gave Moses the first copy along with the Tablets of Stone, two tablets containing the Ten Commandments.Gaster, T.H. "Samaritans," pp. 190–197 in ''Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible, Volume 4''. George Arthur Buttrick, gen. ed. Nashville: Abingdon, 1962. They believe that they preserve this divinely composed text uncorrupted to the present day. Samaritans commonly refer to their Pentateuch as (''Qushta'', Aramaic for "Truth").

Samaritans include only the Pentateuch in their biblical canon. They do not recognize Authorship of the Bible#Divine authorship, divine authorship or Biblical inspiration, inspiration in any other book in the Jewish Tanakh. A Book of Joshua (Samaritan), Samaritan Book of Joshua partly based upon the Tanakh's Book of Joshua exists, but Samaritans regard it as a non-canonical secular historical chronicle.

According to a view based on the biblical Book of Ezra (), the Samaritans are the people of Samaria who parted ways with the people of Kingdom of Judah, Judah (the Judahites) in the Yehud Medinata, Persian period.Tov 2001, pp. 82–83

Samaritans believe that God authored their Pentateuch and gave Moses the first copy along with the Tablets of Stone, two tablets containing the Ten Commandments.Gaster, T.H. "Samaritans," pp. 190–197 in ''Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible, Volume 4''. George Arthur Buttrick, gen. ed. Nashville: Abingdon, 1962. They believe that they preserve this divinely composed text uncorrupted to the present day. Samaritans commonly refer to their Pentateuch as (''Qushta'', Aramaic for "Truth").

Samaritans include only the Pentateuch in their biblical canon. They do not recognize Authorship of the Bible#Divine authorship, divine authorship or Biblical inspiration, inspiration in any other book in the Jewish Tanakh. A Book of Joshua (Samaritan), Samaritan Book of Joshua partly based upon the Tanakh's Book of Joshua exists, but Samaritans regard it as a non-canonical secular historical chronicle.

According to a view based on the biblical Book of Ezra (), the Samaritans are the people of Samaria who parted ways with the people of Kingdom of Judah, Judah (the Judahites) in the Yehud Medinata, Persian period.Tov 2001, pp. 82–83The Samaritans believe that it was not they, but the Jews, who separated from the authentic stream of the Israelites, Israelite tradition and law, around the time of Eli (biblical figure), Eli, in the 11th century BCE. Jews have traditionally connected the origin of the Samaritans with the later events described in claiming that the Samaritans are not related to the Israelites, but to those brought to Samaria by the Assyrians.

Scholarly perspective

Modern scholarship connects the formation of the Samaritan community with events which followed the Babylonian captivity. One view is that the Samaritans are the people of the Kingdom of Israel (Samaria), Kingdom of Israel who separated from the Kingdom of Judah. Another view is that the event happened somewhere around 432 BCE, when Manasseh, the son-in-law of Sanballat, went off to found a community in Samaria, as related in the Book of Nehemiah 13:28 and ''Antiquities of the Jews'' by Josephus. Josephus himself, however, dates this event and the building of the temple at Shechem to the time of Alexander the Great. Others believe that the real schism between the peoples did not take place until Hasmonean times when the Gerizim temple was destroyed in 128 BCE by John Hyrcanus. The script of the Samaritan Pentateuch, its close connections at many points with the Septuagint, and its even closer agreements with the present Hebrew text, all suggest a date about 122 BCE.Buttrick 1952, p. 35. Excavation work undertaken since 1982 by Yitzhak Magen has firmly dated the temple structures on Gerizim to the middle of the 5th century BCE, built by Sanballat the Horonite, a contemporary of Ezra and Nehemiah, who lived more than one hundred years before the Sanballat that is mentioned by Josephus. The adoption of the Pentateuch as the sacred text of the Samaritans before their final schism with the Palestinian Jewish community provides evidence that it was already widely accepted as a canonical authority in that region.Comparison with other versions

Comparison with the Masoretic

Manuscripts of the Samaritan Pentateuch are written in a different script than the one used in the Masoretic Text, Masoretic Pentateuch, used by Jews. The Samaritan text is written with the Samaritan alphabet, derived from the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet used by the Israelite community prior to the Babylonian captivity. During the exile in Babylon, Jews adopted the Ktav Ashuri, Ashuri script, based on the Babylonians' Aramaic alphabet, which was developed into the modern Hebrew alphabet. Originally, all manuscripts of the Samaritan Pentateuch consisted of unvocalized text written using only the letters of the Samaritan alphabet. Beginning in the 12th century, some manuscripts show a partial vocalization resembling the Jewish Tiberian vocalization used in Masoretic manuscripts. More recently, manuscripts have been produced with full vocalization. The Samaritan Pentateuchal text is divided into 904 paragraphs. Divisions between sections of text are marked with various combinations of lines, dots or an asterisk; a dot is used to indicate the separation between words.

The Polyglot (book)#London Polyglot, ''London Polyglot'' lists six thousand instances where the Samaritan Pentateuch differs from the Masoretic (Jewish) text.Hjelm 2000, p. 77

Manuscripts of the Samaritan Pentateuch are written in a different script than the one used in the Masoretic Text, Masoretic Pentateuch, used by Jews. The Samaritan text is written with the Samaritan alphabet, derived from the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet used by the Israelite community prior to the Babylonian captivity. During the exile in Babylon, Jews adopted the Ktav Ashuri, Ashuri script, based on the Babylonians' Aramaic alphabet, which was developed into the modern Hebrew alphabet. Originally, all manuscripts of the Samaritan Pentateuch consisted of unvocalized text written using only the letters of the Samaritan alphabet. Beginning in the 12th century, some manuscripts show a partial vocalization resembling the Jewish Tiberian vocalization used in Masoretic manuscripts. More recently, manuscripts have been produced with full vocalization. The Samaritan Pentateuchal text is divided into 904 paragraphs. Divisions between sections of text are marked with various combinations of lines, dots or an asterisk; a dot is used to indicate the separation between words.

The Polyglot (book)#London Polyglot, ''London Polyglot'' lists six thousand instances where the Samaritan Pentateuch differs from the Masoretic (Jewish) text.Hjelm 2000, p. 77As different printed editions of the Samaritan Pentateuch are based upon different sets of manuscripts, the precise number varies significantly from one edition to another.Purvis, J.D. "Samaritan Pentateuch," pp. 772–775 in ''Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible, Supplementary Volume''. Keith Crim, gen. ed. Nashville: Abingdon, 1976. Only a minority of such differences are significant. Most are simply spelling differences, usually concerning Hebrew letters of similar appearance; the use of more ''Mater lectionis, matres lectionis'' (symbols indicating vowels) in the Samaritan Pentateuch, compared with the Masoretic; different placement of words in a sentence; and the replacement of some verbal constructions with equivalent ones.Vanderkam 2002, p. 93

A comparison between both versions shows a preference in the Samaritan version for the Hebrew Preposition and postposition, preposition ''al'' where the Masoretic text has ''el''. The most notable substantial differences between both texts are those related to Mount Gerizim, the Samaritans' place of worship. The Samaritan version of the Ten Commandments includes the command that an altar be built on Mount Gerizim on which all sacrifices should be offered. "But there is at least one case, Deut.27.4–7, in which the reading 'Gerizim' in the Samaritan Pentateuch, confirmed by Σ and by the Old Latin, seems to be preferable to that of the Massoretic text, which has Ebal, the other mountain standing above Nablus." The Samaritan Pentateuch contains the following paragraph, which is absent from the Jewish version: Another important difference between the Samaritan Torah and the Jewish (Masoretic) Torah is in . According to the Jewish text, the Israelites were told to enter the Promised Land and build an altar on Mount Ebal, while the Samaritan text says that such altar, the first built by the Israelites in the Promised Land, should be built on Mount Gerizim. A few verses afterwards, both the Jewish and the Samaritan texts contain instructions for the Israelites to perform two ceremonies upon entering the Promised Land: one of blessings, to be held on Mount Gerizim, and one of cursings, to take place on Mount Ebal. In 1946, the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered, which include the oldest known versions of the Torah. In , the Dead Sea scroll fragments bring "Gerizim" instead of "Ebal", indicating that the Samaritan version was likely the original reading. A newly published Dead Sea Scroll fragment of Deuteronomy has "Gerizim" instead of "Ebal" in Deuteronomy 27:4. Other differences between the Samaritan and the Masoretic (Jewish) texts include: In , the Samaritan Pentateuch refers to Moses' Zipporah, wife as "''kaashet''", which translates as "the beautiful woman", while the Jewish version and the Jewish commentaries suggest that the word used was "''Kushi''", meaning "black woman" or "Cushitic languages, Cushite woman." For the Samaritans, therefore, Moses had only one wife, Zipporah, throughout his whole life, while Jewish sources generally understand that Moses had two wives, Zipporah and a second, unnamed Cushite woman. Several other differences are found. The Samaritan Pentateuch uses less Anthropomorphism, anthropomorphic language in descriptions of God, with intermediaries performing actions that the Jewish version attributes directly to God. Where the Jewish text describes Yahweh as a "man of war" (), the Samaritan has "hero of war", a phrase applied to spiritual beings. In , the Samaritan text reads "The Angel of the Lord, Angel of God found Balaam", in contrast with the Jewish text, which reads "And God met Balaam." In , the Jewish text says that Joseph (Genesis), Joseph's grandchildren were born "upon the knees of Joseph", while the Samaritan text says they were born "in the days of Joseph". In about thirty-four instances, the Samaritan Pentateuch has repetitions in one section of text that was also found in other parts of the Pentateuch. Such repetitions are also implied or presupposed in the Jewish text, but not explicitly recorded in it. For example, the Samaritan text in the Book of Exodus on multiple occasions records Moses repeating to Pharaoh exactly what both God had previously instructed Moses to tell him, which makes the text look repetitious, in comparison with the Jewish text. In other occasions, the Samaritan Pentateuch has subject (grammar), subjects, prepositions, grammatical particle, particles, apposition, appositives, including the repetition of words and phrases within a single passage, that are absent from the Jewish text.

Comparison with the Septuagint and Latin Vulgate

The Samaritan Torah contains frequent agreements with the Septuagint and the Vulgate, Latin Vulgate, the two Bible translations to which Catholics have traditionally ascribed considerable authority. The Septuagint text agrees with the Samaritan version in approximately 1,900 of the 6,000 instances in which it differs from the Masoretic (Jewish) text. Many of these agreements reflect inconsequential grammatical details, but some are significant. For example, in both the Samaritan and the Septuagint reads: :"Now the sojourning of the children of Israel and of their fathers which they had dwelt in the land of Canaan and in Egypt was four hundred and thirty years." In the Masoretic (Jewish) text, the passage reads: :"Now the sojourning of the children of Israel, who dwelt in Egypt, was four hundred and thirty years." Passages in the Vulgate, Latin Vulgate also show agreements with the Samaritan version, in contrast with the Masoretic (Jewish) version. In , the Samaritan Pentateuch places the Binding of Isaac, binding and near-sacrifice of Isaac in the "land of Moreh" (Hebrew: מוראה), while the Jewish Pentateuch has "land of Moriah" (Hebrew: מריה). The Samaritan "Moreh" describes the region around Shechem and modern-day Nablus, where the Samaritans' holy Mount Gerizim is situated, while Jews claim the land is the same as Temple Mount, Mount Moriah, in Jerusalem,. The Vulgate translates this phrase as ''in terram visionis'' ("in the land of vision") which implies that Jerome was familiar with the reading "Moreh", a Hebrew word whose Semitic root, triliteral root suggests "vision."Evaluations of its relevance for textual criticism

Derivative works

Translations

The Samaritan Targum, composed in the Samaritan dialect of Aramaic, is the earliest translation of the Samaritan Pentateuch. Its creation was motivated by the same need to translate the Pentateuch into the Aramaic language spoken by the community which led to the creation of Jewish Targums such as Targum Onkelos. Samaritans have traditionally ascribed the Targum to Nathanael, a Samaritan priest who died circa 20 BCE. The Samaritan Targum has a complex textual tradition represented by manuscripts belonging to one of three fundamental text types exhibiting substantial divergences from one another. Affinities that the oldest of these textual traditions share with the Dead Sea Scrolls and Onkelos suggest that the Targum may originate from the same school which finalized the Samaritan Pentateuch itself. Others have placed the origin of the Targum around the beginning of the third century or even later. Extant manuscripts of the Targum are "extremely difficult to use" on account of scribal errors caused by a faulty understanding of Hebrew on the part of the Targum's translators and a faulty understanding of Aramaic on the part of later copyists. Scholia of Origen's Hexapla and the writings of some church fathers contain references to "the Samareitikon" (Greek: το Σαμαρειτικόν), a work that is no longer extant. Despite earlier suggestions that it was merely a series of Greek scholia translated from the Samaritan Pentateuch, scholars now concur that it was a complete Greek translation of the Samaritan Pentateuch either directly translated from it or via the Samaritan Targum. It may have been composed for the use of a Greek-speaking Samaritan community residing in Egypt. With the displacement of Samaritan Aramaic by Arabic as the language of the Samaritan community in the centuries following the Muslim conquest of Syria, Arab conquest of Syria, they employed several Arabic translations of the Pentateuch. The oldest was an adaptation of Saadia Gaon's Arabic translation of the Jewish Torah. Although the text was modified to suit the Samaritan community, it still retained many unaltered Jewish readings. By the 11th or 12th century, a new Arabic translation directly based upon the Samaritan Pentateuch had appeared in Nablus. Manuscripts containing this translation are notable for their bilingual or trilingual character; the Arabic text is accompanied by the original Samaritan Hebrew in a parallel column and sometimes the Aramaic text of the Samaritan Targum in a third. Later Arabic translations also appeared; one featured a further Samaritan revision of Saadia Gaon's translation to bring it into greater conformity with the Samaritan Pentateuch and others were based upon Arabic Pentateuchal translations used by Christians. In April 2013, a complete English translation of the Samaritan Pentateuch comparing it to the Masoretic version was published.Exegetical and liturgical texts

Several biblical commentaries and other theological texts based upon the Samaritan Pentateuch have been composed by members of the Samaritan community from the fourth century CE onwards. Samaritans also employ liturgy, liturgical texts containing Catena (Biblical commentary), catenae extracted from their Pentateuch.Manuscripts and printed editions

Manuscripts

Abisha Scroll

Samaritans attach special importance to the ''Abisha Scroll'' used in the Samaritan synagogue of Nablus. It consists of a continuous length of parchment sewn together from the skins of rams that, according to a Samaritan tradition, were ritually sacrificed. The text is written in gold letters. Rollers tipped with ornamental knobs are attached to both ends of the parchment and the whole is kept in a cylindrical silver case when not in use. Samaritans claim it was penned by Abishua, great-grandson of Aaron (), thirteen years after the entry into the land of Israel under the leadership of Joshua, son of Nun, although contemporary scholars describe it as a composite of several fragmentary scrolls each penned between the 12th and 14th centuries CE. Other manuscripts of the Samaritan Pentateuch consist of vellum or cotton paper written upon with black ink. Numerous manuscripts of the text exist, but none written in the original Hebrew or in translation predates the Middle Ages. The scroll contains a cryptogram, dubbed the ''tashqil'' by scholars, which Samaritans consider to be Abishua's ancient colophon:

Samaritans attach special importance to the ''Abisha Scroll'' used in the Samaritan synagogue of Nablus. It consists of a continuous length of parchment sewn together from the skins of rams that, according to a Samaritan tradition, were ritually sacrificed. The text is written in gold letters. Rollers tipped with ornamental knobs are attached to both ends of the parchment and the whole is kept in a cylindrical silver case when not in use. Samaritans claim it was penned by Abishua, great-grandson of Aaron (), thirteen years after the entry into the land of Israel under the leadership of Joshua, son of Nun, although contemporary scholars describe it as a composite of several fragmentary scrolls each penned between the 12th and 14th centuries CE. Other manuscripts of the Samaritan Pentateuch consist of vellum or cotton paper written upon with black ink. Numerous manuscripts of the text exist, but none written in the original Hebrew or in translation predates the Middle Ages. The scroll contains a cryptogram, dubbed the ''tashqil'' by scholars, which Samaritans consider to be Abishua's ancient colophon:

I, Abishua,—the son of Phinehas, the son of Eleazar, the son of Aaron, unto them be accorded the grace of YHWH and His glory—wrote the holy book at the entrance of the tabernacle of the congregation, at Mount Gerizim, in the year thirteen of the possession by the children of Israel, of the Land of Canaan according to its boundaries [all] around; I praise YHWH.

Western scholarship

Interest in the Samaritan Pentateuch was awakened in 1616 when the traveler Pietro della Valle purchased a copy of the text in Damascus. This manuscript, now known as Codex B, was deposited in a Parisian library. In 1631, an edited copy of Codex B was published in Le Jay's (Paris) Polyglot by Jean Morin.: "When the Samaritan version of the Pentateuch was revealed to the Western world early in the 17th century... [footnote: 'In 1632 the Frenchman Jean Morin published the Samaritan Pentateuch in the Parisian Biblia Polyglotta based on a manuscript that the traveler Pietro Della Valle had bought from Damascus sixteen years previously.]" It was republished in Walton's Polyglot in 1657. Subsequently, Archbishop Ussher and others procured additional copies which were brought to Europe and later, America.

Interest in the Samaritan Pentateuch was awakened in 1616 when the traveler Pietro della Valle purchased a copy of the text in Damascus. This manuscript, now known as Codex B, was deposited in a Parisian library. In 1631, an edited copy of Codex B was published in Le Jay's (Paris) Polyglot by Jean Morin.: "When the Samaritan version of the Pentateuch was revealed to the Western world early in the 17th century... [footnote: 'In 1632 the Frenchman Jean Morin published the Samaritan Pentateuch in the Parisian Biblia Polyglotta based on a manuscript that the traveler Pietro Della Valle had bought from Damascus sixteen years previously.]" It was republished in Walton's Polyglot in 1657. Subsequently, Archbishop Ussher and others procured additional copies which were brought to Europe and later, America.

Modern publications

Until the latter half of the 20th century, Textual criticism, critical editions of the Samaritan Pentateuch were largely based upon Codex B. The most notable of these is ''Der Hebräische Pentateuch der Samaritaner'' (''The Hebrew Pentateuch of the Samaritans'') compiled by August von Gall and published in 1918. An extensive critical apparatus is included listing variant readings found in previously published manuscripts of the Samaritan Pentateuch. His work is still regarded as being generally accurate despite the presence of some errors, but it neglects important manuscripts including the Abisha Scroll which had not yet been published at the time. Textual variants found in the Abisha scroll were published in 1959 by Federico Pérez CastroBrotzman 1994, p. 66and between 1961 and 1965 by A. and R. Sadaqa in ''Jewish and Samaritan Versions of the Pentateuch – With Particular Stress on the Differences Between Both Texts''. In 1976 L.F. Giron-Blanc published Codex Add. 1846, a Samaritan Pentateuch codex dating to 1100 CE in the critical edition ''Pentateuco Hebreo-Samaritano: Génesis'' supplemented with variants found in fifteen previously unpublished manuscripts. Certain recently published critical editions of Pentateuchal books take Samaritan variants into account, including D.L. Phillips' edition of Exodus. The Arabic translation of the Samaritan Pentateuch has been edited and published at the beginning of the 21st century. Several publications containing the text of the Samaritan Targum have appeared. In 1875, the German scholar Adolf Brüll published his ''Das samaritanische Targum zum Pentateuch'' (''The Samaritan Targum to the Pentateuch''). More recently a two volume set edited by Abraham Tal appeared featuring the first critical edition based upon all extant manuscripts containing the Targumic text.

See also

* Samaritan HebrewReferences

Citations

Sources

* * * * George Arthur Buttrick, Buttrick, George Arthur and board, eds. (1952). ''The Interpreter's Bible'', Vol. 1. Nashville, Tennessee: Abingdon Press. * * * * * * * * * * *Bibliography

* Tsedaka, Benyamim, and Sharon Sullivan, eds. ''The Israelite Samaritan Version of the Torah: First English Translation Compared with the Masoretic Version''. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2013.* Shoulson, Mark E, compiler. ''The Torah: Jewish and Samaritan versions compared'' (Hebrew Edition, 2008). Evertype. / . * Schorch, Stefan. ''Die Vokale des Gesetzes: Die samaritanische Lesetradition als Textzeugin der Tora (Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft)'' (German Edition). Pub. Walter de Gruyter (June 3, 2004). / * A.C. Hwiid, Specimen ineditae versionis Arabico-Samaritanae, Pentateuchi e codice manuscripto Bibliothecae Barberinae (Rome, 1780). * A.S. Halkin, “The Scholia to Numbers and Deuteronomy in the Samaritan Arabic Pentateuch,” Jewish Quarterly Review 34 n.s. (1943–44): 41-59. * T.G.J. Juynboll, “Commentatio de versione Arabico-Samaritana, et de scholiis, quae codicibus Parisiensibus n. 2 et 4 adscripta sunt,” Orientalia 2 (1846), pp. 113–157.

External links

Jewish Encyclopedia: Samaritans: Samaritan Version of the Pentateuch

Samaritan Pentateuch Add.1846

nbsp;– digitised version of the earliest complete manuscript of the Samaritan Pentateuch on Cambridge Digital Library {{Authority control 2nd-century BC books Torah Biblical criticism Early versions of the Bible Ancient Jewish literature Jewish prayer and ritual texts Samaritan texts Texts attributed to Moses Ancient Hebrew texts