Rhamphorhynchus DB.jpg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

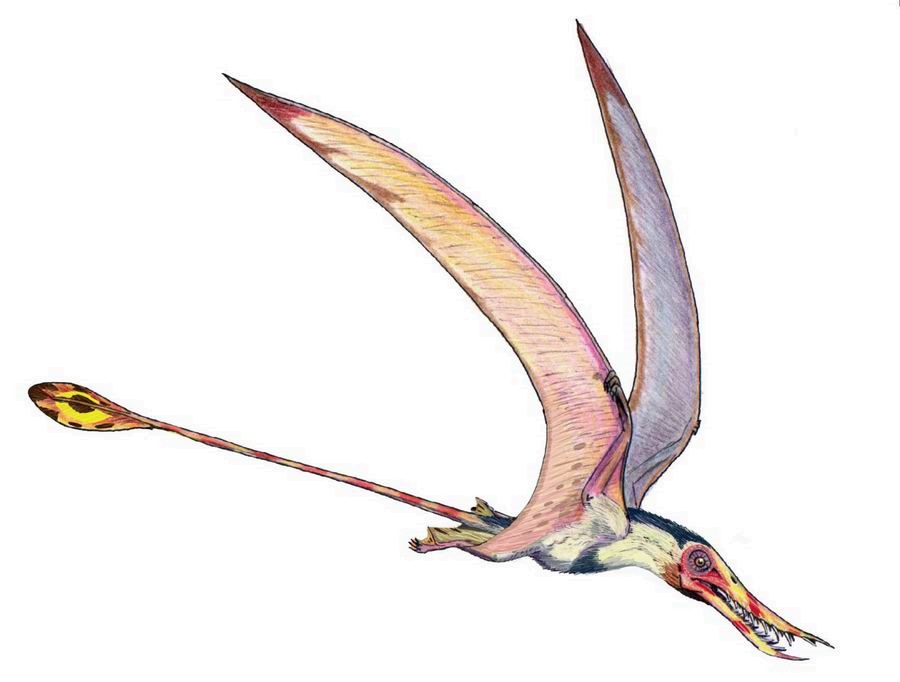

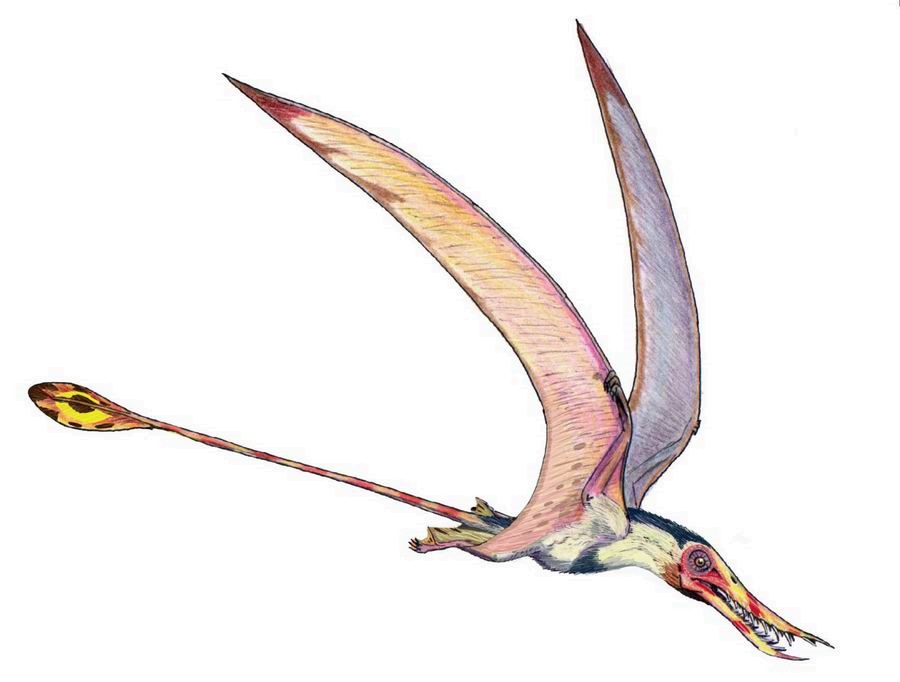

''Rhamphorhynchus'' (, from

The classification and

The classification and

The original species, ''Pterodactylus münsteri'', remained misclassified until a re-evaluation was published by Richard Owen in an 1861 book, in which he renamed it as ''Rhamphorhynchus münsteri''.Owen, R. (1861). ''Palaeontology, or a Systematic Summary of Extinct Animals and their Geological Relations''. Adam and Charles Black, Edinburgh, 1-463. The type specimen of ''R. muensteri'', described by Münster and Goldfuss, was lost during

The original species, ''Pterodactylus münsteri'', remained misclassified until a re-evaluation was published by Richard Owen in an 1861 book, in which he renamed it as ''Rhamphorhynchus münsteri''.Owen, R. (1861). ''Palaeontology, or a Systematic Summary of Extinct Animals and their Geological Relations''. Adam and Charles Black, Edinburgh, 1-463. The type specimen of ''R. muensteri'', described by Münster and Goldfuss, was lost during

The largest known specimen of ''Rhamphorhynchus muensteri'' (catalog number BMNH 37002) measures long with a wingspan of . A very large, fragmentary rhamphorhynchid specimen from Ettling in Germany may also belong to the genus, in which case ''Rhamphorhynchus'' would be the largest known non-pterodactyloid pterosaur and one of the largest pterosaurs known from the Jurassic. This specimen represents an individual around 180% the size of the next largest specimen of the genus, with an estimated wingspan of over 3 metres.

The largest known specimen of ''Rhamphorhynchus muensteri'' (catalog number BMNH 37002) measures long with a wingspan of . A very large, fragmentary rhamphorhynchid specimen from Ettling in Germany may also belong to the genus, in which case ''Rhamphorhynchus'' would be the largest known non-pterodactyloid pterosaur and one of the largest pterosaurs known from the Jurassic. This specimen represents an individual around 180% the size of the next largest specimen of the genus, with an estimated wingspan of over 3 metres.

The smallest known ''Rhamphorhynchus'' specimen has a wingspan of only 290 millimeters; however, it is likely that even such a small individual was capable of flight. Bennett examined two possibilities for hatchlings: that they were

The smallest known ''Rhamphorhynchus'' specimen has a wingspan of only 290 millimeters; however, it is likely that even such a small individual was capable of flight. Bennett examined two possibilities for hatchlings: that they were

Having determined that ''Rhamphorhynchus'' specimens fit into discrete year-classes, Bennett was able to estimate the growth rate during one year by comparing the size of one-year-old specimens with two-year-old specimens. He found that the average growth rate during the first year of life for ''Rhamphorhynchus'' was 130% to 173%, slightly faster than the growth rate in

Having determined that ''Rhamphorhynchus'' specimens fit into discrete year-classes, Bennett was able to estimate the growth rate during one year by comparing the size of one-year-old specimens with two-year-old specimens. He found that the average growth rate during the first year of life for ''Rhamphorhynchus'' was 130% to 173%, slightly faster than the growth rate in

Though ''Rhamphorhynchus'' is often depicted as an aerial piscivore, recent evidence suggests that, much like most modern aquatic birds, it probably foraged while swimming. Like several

Though ''Rhamphorhynchus'' is often depicted as an aerial piscivore, recent evidence suggests that, much like most modern aquatic birds, it probably foraged while swimming. Like several

In 2003, a team of researchers led by Lawrence Witmer studied the brain anatomy of several types of pterosaurs, including ''Rhamphorhynchus muensteri'', using endocasts of the brain they retrieved by performing CAT scans of fossil skulls. Using comparisons to modern animals, they were able to estimate various physical attributes of pterosaurs, including relative head orientation during flight and coordination of the wing membrane muscles. Witmer and his team found that ''Rhamphorhynchus'' held its head parallel to the ground due to the orientation of the ''osseous labyrinth'' of the inner ear, which helps animals detect

In 2003, a team of researchers led by Lawrence Witmer studied the brain anatomy of several types of pterosaurs, including ''Rhamphorhynchus muensteri'', using endocasts of the brain they retrieved by performing CAT scans of fossil skulls. Using comparisons to modern animals, they were able to estimate various physical attributes of pterosaurs, including relative head orientation during flight and coordination of the wing membrane muscles. Witmer and his team found that ''Rhamphorhynchus'' held its head parallel to the ground due to the orientation of the ''osseous labyrinth'' of the inner ear, which helps animals detect

/ref>

Several limestone slabs have been discovered in which fossils of ''Rhamphorhynchus'' are found in close association with the

Several limestone slabs have been discovered in which fossils of ''Rhamphorhynchus'' are found in close association with the

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic p ...

''rhamphos'' meaning "beak" and ''rhynchus'' meaning "snout") is a genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

of long-tailed pterosaur

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 ...

s in the Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The Jurassic constitutes the middle period of ...

period. Less specialized than contemporary, short-tailed pterodactyloid

Pterodactyloidea (derived from the Greek words ''πτερόν'' (''pterón'', for usual ''ptéryx'') "wing", and ''δάκτυλος'' (''dáktylos'') "finger" meaning "winged finger", "wing-finger" or "finger-wing") is one of the two traditional ...

pterosaurs such as ''Pterodactylus

''Pterodactylus'' (from Greek () meaning 'winged finger') is an extinct genus of pterosaurs. It is thought to contain only a single species, ''Pterodactylus antiquus'', which was the first pterosaur to be named and identified as a flying rept ...

'', it had a long tail, stiffened with ligaments, which ended in a characteristic soft-tissue tail vane. The mouth of ''Rhamphorhynchus'' housed needle-like teeth, which were angled forward, with a curved, sharp, beak-like tip lacking teeth, indicating a diet mainly of fish

Fish are aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish as well as various extinct related groups. Approximately 95% of ...

; indeed, fish and cephalopod remains are frequently found in ''Rhamphorhynchus'' abdominal contents, as well as in their coprolite

A coprolite (also known as a coprolith) is fossilized feces. Coprolites are classified as trace fossils as opposed to body fossils, as they give evidence for the animal's behaviour (in this case, diet) rather than morphology. The name is de ...

s.

Although fragmentary fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

remains possibly belonging to ''Rhamphorhynchus'' have been found in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands ...

, and Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

, the best preserved specimens come from the Solnhofen limestone of Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

. Many of these fossils preserve not only the bones but impressions of soft tissues, such as wing membranes. Scattered teeth believed to belong to ''Rhamphorhynchus'' have been found in Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

as well.''Rhamphorhynchus.'' In: Cranfield, Ingrid (ed.). ''The Illustrated Directory of Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Creatures''. London: Salamander Books, Ltd. Pp. 302-305.

History and classification

The classification and

The classification and taxonomy

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. ...

of ''Rhamphorhynchus'', like many pterosaur species known since the Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardia ...

, is complex, with a long history of reclassification under a variety of names, often for the same specimens.

The first named specimen of ''Rhamphorhynchus'' was brought to the attention of Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring

Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring (28 January 1755 – 2 March 1830) was a German physician, anatomist, anthropologist, paleontologist and inventor. Sömmerring discovered the macula in the retina of the human eye. His investigations on the brain ...

by the collector Georg Graf zu Münster in 1825. Von Sömmerring concluded that it belonged to an ancient bird. When further preparation uncovered teeth, Graf zu Münster sent a cast to Professor Georg August Goldfuss

Georg August Goldfuss (Goldfuß, 18 April 1782 – 2 October 1848) was a German palaeontologist, zoologist and botanist.

Goldfuss was born at Thurnau near Bayreuth. He was educated at Erlangen, where he graduated PhD in 1804 and became profes ...

, who recognised it as a pterosaur. Like most pterosaurs described in the mid 19th century, ''Rhamphorhynchus'' was originally considered to be a species of ''Pterodactylus

''Pterodactylus'' (from Greek () meaning 'winged finger') is an extinct genus of pterosaurs. It is thought to contain only a single species, ''Pterodactylus antiquus'', which was the first pterosaur to be named and identified as a flying rept ...

''. However, at the time, many scientists incorrectly considered ''Ornithocephalus'' to be the valid name for ''Pterodactylus''. This specimen of ''Rhamphorhynchus'' was therefore originally named ''Ornithocephalus Münsteri''. This was first mentioned in 1830 by Graf zu Münster himself.Münster, G. Graf zu. (1830). "Nachtrag zu der Abhandlung des Professor Goldfuss über den ''Ornithocephalus Münsteri'' (Goldf.)." ''Bayreuth'', 8 p. However, the description making the name valid was given by Goldfuss in an 1831 follow-up to Münster's short paper. Note that the ICZN later ruled that non-standard Latin characters, such as ''ü'', would not be allowed in scientific names, and the spelling ''münsteri'' was emended to ''muensteri'' by Richard Lydekker

Richard Lydekker (; 25 July 1849 – 16 April 1915) was an English naturalist, geologist and writer of numerous books on natural history.

Biography

Richard Lydekker was born at Tavistock Square in London. His father was Gerard Wolfe Lydekker, ...

in 1888.

In 1839, Münster described another specimen that he considered to belong to ''Ornithocephalus'' (i.e. ''Pterodactylus''), with a distinctive long tail. He named it ''Ornithocephalus longicaudus'', meaning "long tail", to differentiate it from the specimens with short tails (the true specimens of ''Pterodactylus'').

In 1845, Hermann von Meyer

Christian Erich Hermann von Meyer (3 September 1801 – 2 April 1869), known as Hermann von Meyer, was a German palaeontologist. He was awarded the 1858 Wollaston medal by the Geological Society of London.

Life

He was born at Frankfurt am Ma ...

officially emended the original species ''Ornithocephalus münsteri'' to ''Pterodactylus münsteri'', since the name ''Pterodactylus'' had been by that point recognized as having priority over ''Ornithocephalus''. In a subsequent 1846 paper describing a new species of long-tailed 'pterodactyl', von Meyer decided that the long-tailed forms of ''Pterodactylus'' were different enough from the short-tailed forms to warrant placement in a subgenus, and he named his new species ''Pterodactylus (Rhamphorhynchus) gemmingi'' after a specimen owned by collector Captain Carl Eming von Gemming that was later by von Gemming sold for three hundred guilders to the Teylers Museum

Teylers Museum () is an art, natural history, and science museum in Haarlem, Netherlands. Established in 1778, Teylers Museum was founded as a centre for contemporary art and science. The historic centre of the museum is the neoclassical Oval R ...

in Haarlem. It was not until 1847 that von Meyer elevated ''Rhamphorhynchus'' to a full-fledged genus, and officially included in it both long-tailed species of ''Pterodactylus'' known at the time, ''R. longicaudus'' (the original species preserving a long tail) and ''R. gemmingi''.Meyer, H. von. (1847). "''Homeosaurus maximiliani'' und ''Rhamphorhynchus (Pterodactylus) longicaudus'', zwei fossile Reptilien aus der Kalkschiefer von Solenhofen." 4X, Frankfurt, 22 p. The type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specime ...

of ''Rhamphorhynchus'' is ''R. longicaudus''; its type specimen

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes th ...

or holotype

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of sever ...

also was sold to the Teylers Museum, where it still resides as TM 6924.

The original species, ''Pterodactylus münsteri'', remained misclassified until a re-evaluation was published by Richard Owen in an 1861 book, in which he renamed it as ''Rhamphorhynchus münsteri''.Owen, R. (1861). ''Palaeontology, or a Systematic Summary of Extinct Animals and their Geological Relations''. Adam and Charles Black, Edinburgh, 1-463. The type specimen of ''R. muensteri'', described by Münster and Goldfuss, was lost during

The original species, ''Pterodactylus münsteri'', remained misclassified until a re-evaluation was published by Richard Owen in an 1861 book, in which he renamed it as ''Rhamphorhynchus münsteri''.Owen, R. (1861). ''Palaeontology, or a Systematic Summary of Extinct Animals and their Geological Relations''. Adam and Charles Black, Edinburgh, 1-463. The type specimen of ''R. muensteri'', described by Münster and Goldfuss, was lost during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. If available, a new specimen, or neotype

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes the ...

, is designated as the type specimen if the original is lost or deemed too poorly preserved. Peter Wellnhofer

Peter Wellnhofer (born Munich, 1936) is a German paleontologist at the Bayerische Staatssammlung fur Paläontologie in Munich. He is best known for his work on the various fossil specimens of ''Archaeopteryx'' or "Urvogel", the first known bird. W ...

declined to designate a neotype in his 1975 review of the genus, because a number of high-quality casts of the original specimen were still available in museum collections. These can serve as plastotypes.

By the 1990s (and following Wellnhofer's consolidation of many previously named species), about five species of ''Rhamphorhynchus'' were recognized from the Solnhofen limestone of Germany, with a few others having been named from Africa, Spain, and the UK based on fragmentary remains. Most of the Solnhofen species were differentiated based on their relative size, and size-related features, such as the relative length of the skull.

In 1995, pterosaur researcher Chris Bennett published an extensive review of the currently recognized German species. Bennett concluded that all the supposedly distinct German species were actually different year-classes of a single species, ''R. muensteri'', representing distinct age groups, with the smaller species being juveniles and the larger adults. Bennett's paper did not cover the British and African species, though he suggested that these should be considered indeterminate members of the family Rhamphorhynchidae

Rhamphorhynchidae is a group of early pterosaurs named after ''Rhamphorhynchus'', that lived in the Late Jurassic. The family Rhamphorhynchidae was named in 1870 by Harry Govier Seeley.Seeley, H.G. (1870). "The Orithosauria: An Elementary Study o ...

and not necessarily species of ''Rhamphorhynchus'' itself. Despite the reduction of the genus to a single species, the type species remains ''R. longicaudus''.

In 2015, a new species of ''Rhamphorhynchus, R. etchesi'' was named for associated remains of a left and right wing from the Kimmeridge Clay

The Kimmeridge Clay is a sedimentary deposit of fossiliferous marine clay which is of Late Jurassic to lowermost Cretaceous age and occurs in southern and eastern England and in the North Sea. This rock formation is the major source rock for Nor ...

in the United Kingdom, the name commemorates the discoverer, Steve Etches, a local collector of the fossils of the Kimmeridge Clay. It is distinguished from other species of ''Rhamphorhynchus'' by "the unique length ratio between wing phalanx 1 and wing phalanx 2"

Phylogeny

Thecladogram

A cladogram (from Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an evolutionary tree because it does not show how ancestors are related to ...

of below is the result of a large phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups o ...

analysis published by Brian Andres & Timothy Myers in 2013. The species ''R. muensteri'' was recovered within the family Rhamphorhynchidae, sister taxon to both '' Cacibupteryx'' and '' Nesodactylus''.

Description

Skull

Contrary to a 1927 report by pterosaur researcherFerdinand Broili

Ferdinand Broili (11 April 1874 in Mühlbach – 30 April 1946 in Mühlbach) was a German paleontologist.

He studied natural sciences at the universities of Würzburg and Munich, where his influences were Karl von Zittel and August Rothpletz. ...

, ''Rhamphorhynchus'' lacked any bony or soft tissue crest, as seen in several species of contemporary small pterodactyloid pterosaurs. Broili claimed to have found a two-millimeter-tall crest made of thin bone that ran much of the skull's length in one ''Rhamphorhynchus'' specimen, evidenced by an impression in the surrounding rock and a few small fragments of the crest itself. However, subsequent examination of this specimen by Wellnhofer in 1975 and Bennett in 2002 using both visible and ultraviolet light found no trace of a crest; both concluded that Broili was mistaken. The supposed crest, they concluded, was simply an artifact of preservation., 148: 132-186, 149: 1-30. The teeth of ''Rhamphorhynchus'' intermesh when the jaw is closed and are suggestive of a piscivorous

A piscivore () is a carnivorous animal that eats primarily fish. The name ''piscivore'' is derived . Piscivore is equivalent to the Greek-derived word ichthyophage, both of which mean "fish eater". Fish were the diet of early tetrapod evoluti ...

diet. There are twenty teeth in the upper jaws and fourteen in the lower jaws.

Paleobiology

Life history

Traditionally, the large size variation between specimens of ''Rhamphorhynchus'' has been taken to represent species variation. However, in a 1995 paper, Bennett argued that these "species" actually represent year-classes of a single species, ''Rhamphorhynchus muensteri'', from flaplings to adults. Following from this interpretation, Bennett found several notable changes that occurred in ''R. muensteri'' as the animal aged. Juvenile ''Rhamphorhynchus'' had relatively short skulls with large eyes, and the toothless beak-like tips of the jaws were shorter in juveniles than adults, with rounded, blunt lower jaw tips eventually becoming slender and pointed as the animals grew. Adult ''Rhamphorhynchus'' also developed a strong upward "hook" at the end of the lower jaw. The number of teeth remained constant from juvenile to adult, though the teeth became relatively shorter and stockier as the animals grew, possibly to accommodate larger and more powerful prey. The pelvic and pectoral girdles fused as the animals aged, with full pectoral fusion attained by one year of age. The shape of the tail vane also changed across various age classes of ''Rhamphorhynchus''. In juveniles, the vane was shallow relative to the tail and roughly oval, or " lancet-shaped". As growth progressed, the tail vane becamediamond

Diamond is a solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Another solid form of carbon known as graphite is the chemically stable form of carbon at room temperature and pressure, ...

-shaped, and finally triangular

A triangle is a polygon with three edges and three vertices. It is one of the basic shapes in geometry. A triangle with vertices ''A'', ''B'', and ''C'' is denoted \triangle ABC.

In Euclidean geometry, any three points, when non- collinea ...

in the largest individuals.

The smallest known ''Rhamphorhynchus'' specimen has a wingspan of only 290 millimeters; however, it is likely that even such a small individual was capable of flight. Bennett examined two possibilities for hatchlings: that they were

The smallest known ''Rhamphorhynchus'' specimen has a wingspan of only 290 millimeters; however, it is likely that even such a small individual was capable of flight. Bennett examined two possibilities for hatchlings: that they were altricial

In biology, altricial species are those in which the young are underdeveloped at the time of birth, but with the aid of their parents mature after birth. Precocial species are those in which the young are relatively mature and mobile from the mome ...

, requiring some period of parental care before leaving the nest, or that they were precocial

In biology, altricial species are those in which the young are underdeveloped at the time of birth, but with the aid of their parents mature after birth. Precocial species are those in which the young are relatively mature and mobile from the mome ...

, hatching with sufficient size and ability for flight. If precocious, Bennett suggested that clutches would be small, with only one or two eggs laid per clutch, to compensate for the relatively large size of the hatchings. Bennett did not speculate on which possibility was more likely, though the discovery of a pterosaur embryo (''Avgodectes'') with strongly ossified bones suggests that pterosaurs in general were precocial, able to fly soon after hatching with minimal parental care. This theory was contested by a histological

Histology,

also known as microscopic anatomy or microanatomy, is the branch of biology which studies the microscopic anatomy of biological tissues. Histology is the microscopic counterpart to gross anatomy, which looks at larger structures vis ...

study of ''Rhamphorhynchus'' that showed the initial rapid growth was followed by a prolonged period of slow growth.

In 2020, published ontogenetic analyses indicated that ''Rhamphorhynchus'' could fly soon after hatching, supporting the theory of precociality in the species. It has also been suggested that juveniles may have occupied different sequential niches throughout their growth as they matured.

Metabolism

Having determined that ''Rhamphorhynchus'' specimens fit into discrete year-classes, Bennett was able to estimate the growth rate during one year by comparing the size of one-year-old specimens with two-year-old specimens. He found that the average growth rate during the first year of life for ''Rhamphorhynchus'' was 130% to 173%, slightly faster than the growth rate in

Having determined that ''Rhamphorhynchus'' specimens fit into discrete year-classes, Bennett was able to estimate the growth rate during one year by comparing the size of one-year-old specimens with two-year-old specimens. He found that the average growth rate during the first year of life for ''Rhamphorhynchus'' was 130% to 173%, slightly faster than the growth rate in alligator

An alligator is a large reptile in the Crocodilia order in the genus ''Alligator'' of the family Alligatoridae. The two extant species are the American alligator (''A. mississippiensis'') and the Chinese alligator (''A. sinensis''). Additiona ...

s. Growth likely slowed considerably after sexual maturity, so it would have taken more than three years to attain maximum adult size.

This growth rate is much slower than the rate seen in large pterodactyloid

Pterodactyloidea (derived from the Greek words ''πτερόν'' (''pterón'', for usual ''ptéryx'') "wing", and ''δάκτυλος'' (''dáktylos'') "finger" meaning "winged finger", "wing-finger" or "finger-wing") is one of the two traditional ...

pterosaurs, such as '' Pteranodon'', which attained near-adult size within the first year of life. Additionally, pterodactyloids had ''determinate growth'', meaning that the animals reached a fixed maximum adult size and stopped growing. Previous assumptions of rapid growth rate in rhamphorhynchoids were based on the assumption that they needed to be warm-blooded

Warm-blooded is an informal term referring to animal species which can maintain a body temperature higher than their environment. In particular, homeothermic species maintain a stable body temperature by regulating metabolic processes. The onl ...

to sustain active flight. Warm-blooded animals, like modern bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweig ...

s and bat

Bats are mammals of the order Chiroptera.''cheir'', "hand" and πτερόν''pteron'', "wing". With their forelimbs adapted as wings, they are the only mammals capable of true and sustained flight. Bats are more agile in flight than most ...

s, normally show rapid growth to adult size and determinate growth. Because there is no evidence for either in ''Rhamphorhynchus'', Bennett considered his findings consistent with an ectotherm

An ectotherm (from the Greek () "outside" and () "heat") is an organism in which internal physiological sources of heat are of relatively small or of quite negligible importance in controlling body temperature.Davenport, John. Animal Life ...

ic metabolism, though he recommended more studies needed to be done. Cold-blooded ''Rhamphorhynchus'', Bennett suggested, may have basked in the sun or worked their muscles to accumulate enough energy for bouts of flight, and cooled to ambient temperature when not active to save energy, like modern reptiles.

Swimming

Though ''Rhamphorhynchus'' is often depicted as an aerial piscivore, recent evidence suggests that, much like most modern aquatic birds, it probably foraged while swimming. Like several

Though ''Rhamphorhynchus'' is often depicted as an aerial piscivore, recent evidence suggests that, much like most modern aquatic birds, it probably foraged while swimming. Like several pteranodontia

Pteranodontia is an extinct group of ornithocheiroid pterodactyloid pterosaurs that lived during the Late Cretaceous period (Coniacian to Maastrichtian stages) of North America and Africa. They were some of the most advanced pterosaurs, and posse ...

ns it has hatchet-shaped deltopectoral crests, a short torso and short legs, all features associated with water based launching in pterosaurs. Its feet are broad and large, being useful for propulsion, and the predicted floating position is adequate by pterosaur standards. The animal's ability to swim may account for the genus' generally excellent fossil record, being in a position where preservation would be much easier.

Sexual dimorphism

Both Koh Ting-Pong andPeter Wellnhofer

Peter Wellnhofer (born Munich, 1936) is a German paleontologist at the Bayerische Staatssammlung fur Paläontologie in Munich. He is best known for his work on the various fossil specimens of ''Archaeopteryx'' or "Urvogel", the first known bird. W ...

recognized two distinct groups among adult ''Rhamphorhynchus muensteri'', differentiated by the proportions of the neck, wing, and hind limbs, but particularly in the ratio of skull to humerus length. Both researchers noted that these two groups of specimens were found in roughly a 1:1 ratio, and interpreted them as different sexes. Bennett tested for sexual dimorphism in ''Rhamphorhynchus'' by using a statistical analysis, and found that the specimens did indeed group together into small-headed and large-headed sets. However, without any known variation in the actual form of the bones or soft tissue (morphological differences), he found the case for sexual dimorphism inconclusive.

Head orientation

In 2003, a team of researchers led by Lawrence Witmer studied the brain anatomy of several types of pterosaurs, including ''Rhamphorhynchus muensteri'', using endocasts of the brain they retrieved by performing CAT scans of fossil skulls. Using comparisons to modern animals, they were able to estimate various physical attributes of pterosaurs, including relative head orientation during flight and coordination of the wing membrane muscles. Witmer and his team found that ''Rhamphorhynchus'' held its head parallel to the ground due to the orientation of the ''osseous labyrinth'' of the inner ear, which helps animals detect

In 2003, a team of researchers led by Lawrence Witmer studied the brain anatomy of several types of pterosaurs, including ''Rhamphorhynchus muensteri'', using endocasts of the brain they retrieved by performing CAT scans of fossil skulls. Using comparisons to modern animals, they were able to estimate various physical attributes of pterosaurs, including relative head orientation during flight and coordination of the wing membrane muscles. Witmer and his team found that ''Rhamphorhynchus'' held its head parallel to the ground due to the orientation of the ''osseous labyrinth'' of the inner ear, which helps animals detect balance

Balance or balancing may refer to:

Common meanings

* Balance (ability) in biomechanics

* Balance (accounting)

* Balance or weighing scale

* Balance as in equality or equilibrium

Arts and entertainment Film

* ''Balance'' (1983 film), a Bulgaria ...

. In contrast, pterodactyloid pterosaurs, such as ''Anhanguera Anhanguera may refer to:

People

* Bartolomeu Bueno da Silva (1672–1740), a bandeirante

Places in Brazil

* Anhanguera, Goiás, a municipality in the state of Goiás

* Anhanguera (district of São Paulo), a district in São Paulo

* Parque Anhan ...

'', appear to have normally held their heads at a downward angle, both in flight and while on the ground.Witmer, L.M., S. Chatterjee, J. Franzosa, T. Rowe, and R. C. Ridgely. (2004). "Neuroanatomy and vestibular apparatus of pterosaurs: Implications for flight, posture, and behavior." Annual Meeting of the Society of Integrative and Comparative Biology, New Orleans, LA. ''Integrative and Comparative Biology'', 43(6): 832/ref>

Daily activity patterns

Comparisons between the sclerotic ring, scleral rings of ''Rhamphorhynchus'' and modern birds and reptiles suggest that it may have been nocturnal, and may have had activity patterns similar to those of modern nocturnal seabirds. This may also indicateniche partitioning

In ecology, niche differentiation (also known as niche segregation, niche separation and niche partitioning) refers to the process by which competing species use the environment differently in a way that helps them to coexist. The competitive exclu ...

with contemporary pterosaurs inferred to be diurnal, such as ''Scaphognathus

''Scaphognathus'' was a pterosaur that lived around Germany during the Late Jurassic. It had a wingspan of 0.9 m (3 ft).

Naming

The first known ''Scaphognathus'' specimen was described in 1831 by August Goldfuss who mistook the taill ...

'' and ''Pterodactylus

''Pterodactylus'' (from Greek () meaning 'winged finger') is an extinct genus of pterosaurs. It is thought to contain only a single species, ''Pterodactylus antiquus'', which was the first pterosaur to be named and identified as a flying rept ...

''.

Ecology

Several limestone slabs have been discovered in which fossils of ''Rhamphorhynchus'' are found in close association with the

Several limestone slabs have been discovered in which fossils of ''Rhamphorhynchus'' are found in close association with the ganoid

A fish scale is a small rigid plate that grows out of the skin of a fish. The skin of most jawed fishes is covered with these protective scales, which can also provide effective camouflage through the use of reflection and colouration, as w ...

fish '' Aspidorhynchus''. In one of these specimens, the jaws of an ''Aspidorhynchus'' pass through the wings of the ''Rhamphorhynchus'' specimen. The ''Rhamphorhynchus'' also has the remains of a small fish, possibly '' Leptolepides'', in its throat. This slab, cataloged as WDC CSG 255, may represent two levels of predation; one by ''Rhamphorhynchus'' and one by ''Aspidorhynchus''. In a 2012 description of WDC CSG 255, researchers proposed that the ''Rhamphorhynchus'' individual had just caught a ''Leptolepides'' while it was swimming. As the ''Leptolepides'' was travelling down its pharynx

The pharynx (plural: pharynges) is the part of the throat behind the mouth and nasal cavity, and above the oesophagus and trachea (the tubes going down to the stomach and the lungs). It is found in vertebrates and invertebrates, though its st ...

, a large ''Aspidorhynchus'' would have attacked from below the water, accidentally puncturing the left wing membrane of the ''Rhamphorhynchus'' with its sharp rostrum

Rostrum may refer to:

* Any kind of a platform for a speaker:

**dais

**pulpit

* Rostrum (anatomy), a beak, or anatomical structure resembling a beak, as in the mouthparts of many sucking insects

* Rostrum (ship), a form of bow on naval ships

* Ros ...

in the process. The teeth in its snout were ensnared in the fibrous tissue of the wing membrane, and as the fish thrashed to release itself the left wing of ''Rhamphorhynchus'' was pulled backward into the distorted position seen in the fossil. The encounter resulted in the death of both individuals, most likely because the two animals sank into an anoxic

The term anoxia means a total depletion in the level of oxygen, an extreme form of hypoxia or "low oxygen". The terms anoxia and hypoxia are used in various contexts:

* Anoxic waters, sea water, fresh water or groundwater that are depleted of diss ...

layer in the water body, depriving the fish of oxygen. The two may have been preserved together as the weight of the head of ''Aspidorhynchus'' held down the much lighter body of ''Rhamphorhynchus''.

"Odontorhynchus"

"Odontorhynchus" ''aculeatus'' was based on a skull with lower jaws that is now lost. This set of jaws supposedly differed in having two teeth united at the tip of the lower jaw, and none at the tip of the upper jaw. The skull was , making it a small form. Stolley, who described the specimen in 1936, argued that ''R. longicaudus'' also should be reclassified in the genus "Odontorhynchus". Both Koh and Wellnhofer rejected this idea, arguing instead that "Odontorhynchus" was a junior synonym of ''R. longicaudus''. Bennett agreed with their assessments, and included both "Odontorhynchus" and ''R. longicaudus'' as synonyms of ''R. muensteri''.See also

*List of pterosaur genera

This list of pterosaurs is a comprehensive listing of all genera that have ever been included in the order Pterosauria, excluding purely vernacular terms. The list includes all commonly accepted genera, but also genera that are now considered inval ...

* Timeline of pterosaur research

This timeline of pterosaur research is a chronologically ordered list of important fossil discoveries, controversies of interpretation, and taxonomic revisions of pterosaurs, the famed flying reptiles of the Mesozoic era. Although pterosaurs w ...

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Rhamphorhynchus (Pterosaur) Late Jurassic pterosaurs of Europe Jurassic reptiles of Africa Rhamphorhynchids Solnhofen fauna Fossil taxa described in 1846 Taxa named by Christian Erich Hermann von Meyer