Peloneustes BW.jpg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Peloneustes'' (meaning "mud swimmer") is a

The strata of the Peterborough Member of the

The strata of the Peterborough Member of the  Naturalist

Naturalist  The Leeds Collection contained multiple ''Peloneustes'' specimens. In 1895, palaeontologist

The Leeds Collection contained multiple ''Peloneustes'' specimens. In 1895, palaeontologist

Another of the species described by Seeley in 1869 was ''Pliosaurus evansi'', based on specimens in the Woodwardian Museum. These consisted of cervical and dorsal (back) vertebrae, ribs, and a coracoid. Due to it being a smaller species of ''Pliosaurus'' and its similarity to ''Peloneustes philarchus'', Lydekker reassigned it to ''Peloneustes'' in 1890, noting that it was larger than ''Peloneustes philarchus''. He also thought that a large mandible and paddle attributed to ''Pleiosaurus ?grandis'' by Phillips in 1871 belonged to this species instead. In 1913, Andrews assigned a partial skeleton of another large pliosaur found by Leeds to ''Peloneustes evansi'', noting that while the mandible and vertebrae were similar to other ''Peloneustes evansi'' specimens, they were quite different from those of ''Peloneustes philarchus''. Consequently, Andrews considered it possible that ''P. evansi'' really belonged to a separate genus that was morphologically intermediate between ''Peloneustes'' and ''Pliosaurus''. In his 1960 review of pliosaurids, Tarlo synonymised ''Peloneustes evansi'' with ''Peloneustes philarchus'' due to their cervical vertebrae being identical (save for a difference in size). He considered the larger specimens of ''Peloneustes evansi'' distinct, and assigned them to a new species of ''Pliosaurus'', ''P. andrewsi'' (although this species is no longer considered to belong in ''Pliosaurus''). Hilary F. Ketchum and Roger B. J. Benson disagreed with this synonymy, and in 2011 considered that since the holotype of ''Peloneustes evansi'' is nondiagnostic (lacking distinguishing features), ''P. evansi'' is a '' nomen dubium'' and therefore an indeterminate pliosaurid.

Palaeontologist E. Koken described another species of ''Peloneustes'', ''P. kanzleri'', in 1905, from the

Another of the species described by Seeley in 1869 was ''Pliosaurus evansi'', based on specimens in the Woodwardian Museum. These consisted of cervical and dorsal (back) vertebrae, ribs, and a coracoid. Due to it being a smaller species of ''Pliosaurus'' and its similarity to ''Peloneustes philarchus'', Lydekker reassigned it to ''Peloneustes'' in 1890, noting that it was larger than ''Peloneustes philarchus''. He also thought that a large mandible and paddle attributed to ''Pleiosaurus ?grandis'' by Phillips in 1871 belonged to this species instead. In 1913, Andrews assigned a partial skeleton of another large pliosaur found by Leeds to ''Peloneustes evansi'', noting that while the mandible and vertebrae were similar to other ''Peloneustes evansi'' specimens, they were quite different from those of ''Peloneustes philarchus''. Consequently, Andrews considered it possible that ''P. evansi'' really belonged to a separate genus that was morphologically intermediate between ''Peloneustes'' and ''Pliosaurus''. In his 1960 review of pliosaurids, Tarlo synonymised ''Peloneustes evansi'' with ''Peloneustes philarchus'' due to their cervical vertebrae being identical (save for a difference in size). He considered the larger specimens of ''Peloneustes evansi'' distinct, and assigned them to a new species of ''Pliosaurus'', ''P. andrewsi'' (although this species is no longer considered to belong in ''Pliosaurus''). Hilary F. Ketchum and Roger B. J. Benson disagreed with this synonymy, and in 2011 considered that since the holotype of ''Peloneustes evansi'' is nondiagnostic (lacking distinguishing features), ''P. evansi'' is a '' nomen dubium'' and therefore an indeterminate pliosaurid.

Palaeontologist E. Koken described another species of ''Peloneustes'', ''P. kanzleri'', in 1905, from the  In 1998, palaeontologist Frank Robin O'Keefe proposed that a pliosaurid specimen from the

In 1998, palaeontologist Frank Robin O'Keefe proposed that a pliosaurid specimen from the

''Peloneustes'' is a small- to medium-sized member of Pliosauridae. NHMUK R3318, the mounted skeleton in the Natural History Museum in London, is long, while the mounted skeleton in the Institut für Geowissenschaften, University of Tübingen measures in length. Plesiosaurs typically can be described as being of the small-headed, long-necked "plesiosauromorph" morphotype or the large-headed, short-necked "pliosauromorph" morphotype. ''Peloneustes'' is of the latter morphotype, with its skull making up a little less than a fifth of the animal's total length. ''Peloneustes'', like all plesiosaurs, had a short tail, massive torso, and all of its limbs modified into large flippers.

''Peloneustes'' is a small- to medium-sized member of Pliosauridae. NHMUK R3318, the mounted skeleton in the Natural History Museum in London, is long, while the mounted skeleton in the Institut für Geowissenschaften, University of Tübingen measures in length. Plesiosaurs typically can be described as being of the small-headed, long-necked "plesiosauromorph" morphotype or the large-headed, short-necked "pliosauromorph" morphotype. ''Peloneustes'' is of the latter morphotype, with its skull making up a little less than a fifth of the animal's total length. ''Peloneustes'', like all plesiosaurs, had a short tail, massive torso, and all of its limbs modified into large flippers.

While the holotype of ''Peloneustes'' lacks the rear portion of its cranium, many additional well-preserved specimens, including one that has not been crushed from top to bottom, have been assigned to this genus. These crania vary in size, measuring in length. The cranium of ''Peloneustes'' is elongated and slopes upwards towards its back end. Viewed from above, the cranium is shaped like an isosceles triangle, with the back of the cranium broad and the front elongated into a narrow

While the holotype of ''Peloneustes'' lacks the rear portion of its cranium, many additional well-preserved specimens, including one that has not been crushed from top to bottom, have been assigned to this genus. These crania vary in size, measuring in length. The cranium of ''Peloneustes'' is elongated and slopes upwards towards its back end. Viewed from above, the cranium is shaped like an isosceles triangle, with the back of the cranium broad and the front elongated into a narrow  Characteristically, the

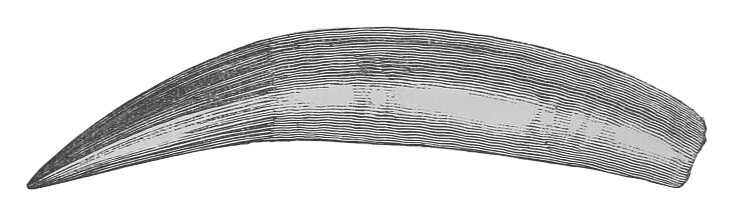

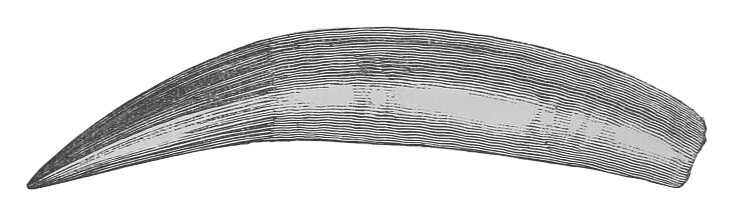

Characteristically, the  The teeth of ''Peloneustes'' have circular cross sections, as seen in other pliosaurids of its age. The teeth have the shape of recurved

The teeth of ''Peloneustes'' have circular cross sections, as seen in other pliosaurids of its age. The teeth have the shape of recurved

In 1913, Andrews reported that ''Peloneustes'' had 21 to 22 cervical, 2 to 3 pectoral, and around 20

In 1913, Andrews reported that ''Peloneustes'' had 21 to 22 cervical, 2 to 3 pectoral, and around 20

Seeley initially described ''Peloneustes'' as a species of ''Plesiosaurus'', a rather common practice (at the time, the scope of genera was similar to what is currently used for

Seeley initially described ''Peloneustes'' as a species of ''Plesiosaurus'', a rather common practice (at the time, the scope of genera was similar to what is currently used for  Within Pliosauridae, the exact phylogenetic position of ''Peloneustes'' is uncertain. In 1889, Lydekker considered ''Peloneustes'' to represent a transitional form between ''Pliosaurus'' and earlier plesiosaurs, although he found it unlikely that ''Peloneustes'' was ancestral to ''Pliosaurus''. In 1960, Tarlo considered ''Peloneustes'' to be a close relative of ''Pliosaurus'', since both taxa had elongated mandibular symphyses. In 2001, O'Keefe and colleagues recovered it as a basal (early-diverging) member of this family, outside of a group including ''

Within Pliosauridae, the exact phylogenetic position of ''Peloneustes'' is uncertain. In 1889, Lydekker considered ''Peloneustes'' to represent a transitional form between ''Pliosaurus'' and earlier plesiosaurs, although he found it unlikely that ''Peloneustes'' was ancestral to ''Pliosaurus''. In 1960, Tarlo considered ''Peloneustes'' to be a close relative of ''Pliosaurus'', since both taxa had elongated mandibular symphyses. In 2001, O'Keefe and colleagues recovered it as a basal (early-diverging) member of this family, outside of a group including ''

Plesiosaurs were well-adapted to marine life. They grew at rates comparable to those of birds and had high

Plesiosaurs were well-adapted to marine life. They grew at rates comparable to those of birds and had high

In a 2001 dissertation, Noè noted many adaptations in pliosaurid skulls for predation. To avoid damage while feeding, the skulls of pliosaurids like ''Peloneustes'' are highly akinetic, where the bones of the cranium and mandible were largely locked in place to prevent movement. The snout contains elongated bones that helped to prevent bending and bears a reinforced junction with the facial region to better resist the stresses of feeding. When viewed from the side, little tapering is visible in the mandible, strengthening it. The mandibular symphysis would have helped deliver an even bite and prevent the mandibles from moving independently. The enlarged coronoid eminence provides a large, strong region for the anchorage of the jaw muscles, although this structure is not as large in ''Peloneustes'' as it is in other contemporary pliosaurids. The regions where the jaw muscles were anchored are located further back on the skull to avoid interference with feeding. The kidney-shaped mandibular glenoid would have made the jaw joint steadier and stopped the mandible from dislocating. Pliosaurid teeth are firmly rooted and interlocking, which strengthens the edges of the jaws. This configuration also works well with the simple rotational movements that pliosaurid jaws were limited to and strengthens the teeth against the struggles of prey. The larger front teeth would have been used to impale prey while the smaller rear teeth crushed and guided the prey backwards toward the throat. With their wide gapes, pliosaurids would not have processed their food very much before swallowing.

In a 2001 dissertation, Noè noted many adaptations in pliosaurid skulls for predation. To avoid damage while feeding, the skulls of pliosaurids like ''Peloneustes'' are highly akinetic, where the bones of the cranium and mandible were largely locked in place to prevent movement. The snout contains elongated bones that helped to prevent bending and bears a reinforced junction with the facial region to better resist the stresses of feeding. When viewed from the side, little tapering is visible in the mandible, strengthening it. The mandibular symphysis would have helped deliver an even bite and prevent the mandibles from moving independently. The enlarged coronoid eminence provides a large, strong region for the anchorage of the jaw muscles, although this structure is not as large in ''Peloneustes'' as it is in other contemporary pliosaurids. The regions where the jaw muscles were anchored are located further back on the skull to avoid interference with feeding. The kidney-shaped mandibular glenoid would have made the jaw joint steadier and stopped the mandible from dislocating. Pliosaurid teeth are firmly rooted and interlocking, which strengthens the edges of the jaws. This configuration also works well with the simple rotational movements that pliosaurid jaws were limited to and strengthens the teeth against the struggles of prey. The larger front teeth would have been used to impale prey while the smaller rear teeth crushed and guided the prey backwards toward the throat. With their wide gapes, pliosaurids would not have processed their food very much before swallowing.

The numerous teeth of ''Peloneustes'' rarely are broken, but often show signs of wear at their tips. Their sharp points, slightly curved, gracile shape, and prominent spacing indicate that they were built for piercing. The slender, elongated snout is similar in shape to that of a

The numerous teeth of ''Peloneustes'' rarely are broken, but often show signs of wear at their tips. Their sharp points, slightly curved, gracile shape, and prominent spacing indicate that they were built for piercing. The slender, elongated snout is similar in shape to that of a

''Peloneustes'' is known from the Peterborough Member (formerly known as the Lower Oxford Clay) of the Oxford Clay Formation. While ''Peloneustes'' has been listed as coming from the Oxfordian stage (spanning from about 164 to 157 million years ago) of the Upper Jurassic, the Peterborough Member actually dates to the

''Peloneustes'' is known from the Peterborough Member (formerly known as the Lower Oxford Clay) of the Oxford Clay Formation. While ''Peloneustes'' has been listed as coming from the Oxfordian stage (spanning from about 164 to 157 million years ago) of the Upper Jurassic, the Peterborough Member actually dates to the  The surrounding land would have had a

The surrounding land would have had a

Plesiosaurs are common in the Peterborough Member, and besides pliosaurids, are represented by cryptoclidids, including ''Cryptoclidus'', '' Muraenosaurus'', '' Tricleidus'', and '' Picrocleidus''. They were smaller plesiosaurs with thin teeth and long necks, and, unlike pliosaurids such as ''Peloneustes'', would have mainly eaten small animals. The ichthyosaur ''

Plesiosaurs are common in the Peterborough Member, and besides pliosaurids, are represented by cryptoclidids, including ''Cryptoclidus'', '' Muraenosaurus'', '' Tricleidus'', and '' Picrocleidus''. They were smaller plesiosaurs with thin teeth and long necks, and, unlike pliosaurids such as ''Peloneustes'', would have mainly eaten small animals. The ichthyosaur '' More pliosaurid species are known from the Peterborough Member than any other assemblage. Besides ''Peloneustes'', these pliosaurids include ''Liopleurodon ferox'', ''Simolestes vorax'', ''"Pliosaurus" andrewsi'', '' Marmornectes candrewi'', '' Eardasaurus powelli'', and, potentially, '' Pachycostasaurus dawni''. However, there is considerable variation in the anatomy of these species, indicating that they fed on different prey, thereby avoiding competition (

More pliosaurid species are known from the Peterborough Member than any other assemblage. Besides ''Peloneustes'', these pliosaurids include ''Liopleurodon ferox'', ''Simolestes vorax'', ''"Pliosaurus" andrewsi'', '' Marmornectes candrewi'', '' Eardasaurus powelli'', and, potentially, '' Pachycostasaurus dawni''. However, there is considerable variation in the anatomy of these species, indicating that they fed on different prey, thereby avoiding competition (

genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

of pliosaurid

Pliosauridae is a family of plesiosaurian marine reptiles from the Latest Triassic to the early Late Cretaceous (Rhaetian to Turonian stages) of Australia, Europe, North America and South America. The family is more inclusive than the archetypal ...

plesiosaur from the Middle Jurassic of England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

. Its remains are known from the Peterborough Member of the Oxford Clay Formation

The Oxford Clay (or Oxford Clay Formation) is a Jurassic marine sedimentary rock formation underlying much of southeast England, from as far west as Dorset and as far north as Yorkshire. The Oxford Clay Formation dates to the Jurassic, specifica ...

, which is Callovian

In the geologic timescale, the Callovian is an age and stage in the Middle Jurassic, lasting between 166.1 ± 4.0 Ma (million years ago) and 163.5 ± 4.0 Ma. It is the last stage of the Middle Jurassic, following the Bathonian and preceding the ...

in age. It was originally described as a species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

of ''Plesiosaurus

''Plesiosaurus'' (Greek: ' ('), near to + ' ('), lizard) is a genus of extinct, large marine sauropterygian reptile that lived during the Early Jurassic. It is known by nearly complete skeletons from the Lias of England. It is distinguishable b ...

'' by palaeontologist

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

Harry Govier Seeley

Harry Govier Seeley (18 February 1839 – 8 January 1909) was a British paleontologist.

Early life

Seeley was born in London on 18 February 1839, the second son of Richard Hovill Seeley, a goldsmith, and his second wife Mary Govier. When his fat ...

in 1896, before being given its own genus by naturalist Richard Lydekker

Richard Lydekker (; 25 July 1849 – 16 April 1915) was an English naturalist, geologist and writer of numerous books on natural history.

Biography

Richard Lydekker was born at Tavistock Square in London. His father was Gerard Wolfe Lydekker, ...

in 1889. While many species have been assigned to ''Peloneustes'', ''P. philarchus'' is currently the only one still considered valid, with the others moved to different genera, considered '' nomina dubia'', or synonymised with ''P. philarchus''. Some of the material formerly assigned to ''P. evansi'' have since been reassigned to ''"Pliosaurus

''Pliosaurus'' (meaning 'more lizard') is an extinct genus of thalassophonean pliosaurid known from the Kimmeridgian and Tithonian stages (Late Jurassic) of Europe and South America. Their diet would have included fish, cephalopods, and marin ...

" andrewsi''. ''Peloneustes'' is known from many specimens, including some very complete material.

With a total length of , ''Peloneustes'' is not a large pliosaurid. It had a large, triangular skull, which occupied about a fifth of its body length. The front of the skull is elongated into a narrow rostrum

Rostrum may refer to:

* Any kind of a platform for a speaker:

**dais

**pulpit

* Rostrum (anatomy), a beak, or anatomical structure resembling a beak, as in the mouthparts of many sucking insects

* Rostrum (ship), a form of bow on naval ships

* Ros ...

(snout). The mandibular symphysis

A symphysis (, pl. symphyses) is a fibrocartilaginous fusion between two bones. It is a type of cartilaginous joint, specifically a secondary cartilaginous joint.

# A symphysis is an amphiarthrosis, a slightly movable joint.

# A growing togethe ...

, where the front ends of each side of the mandible

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movable bone ...

(lower jaw) fuse, is elongate in ''Peloneustes'', and helped strengthen the jaw. An elevated ridge is located between the tooth rows on the mandibular symphysis. The teeth of ''Peloneustes'' are conical and have circular cross-sections, bearing vertical ridges on all sides. The front teeth are larger than the back teeth. With only 19 to 21 cervical (neck) vertebrae, ''Peloneustes'' had a short neck for a plesiosaur. The limbs of ''Peloneustes'' were modified into flippers, with the back pair larger than the front.

''Peloneustes'' has been interpreted as both a close relative of ''Pliosaurus'' or as a more basal (early-diverging) pliosaurid within Thalassophonea

Thalassophonea is an extinct clade of pliosaurids from the Middle Jurassic to the early Late Cretaceous ( Callovian to Turonian) of Australia, Europe, North America and South America. ''Thalassophonea'' was erected by Roger Benson and Patrick ...

, with the latter interpretation finding more support. Like other plesiosaurs, ''Peloneustes'' was well-adapted to aquatic life, using its flippers for a method of swimming known as subaqueous flight. Pliosaurid skulls were reinforced to better withstand the stresses of feeding. The long, narrow snout of ''Peloneustes'' could have been swung quickly through the water to catch fish

Fish are aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish as well as various extinct related groups. Approximately 95% of ...

, which it pierced with its numerous sharp teeth. ''Peloneustes'' would have inhabited an epicontinental (inland) sea that was around deep. It shared its habitat with a variety of other animals, including invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordate ...

s, fish, thalattosuchians, ichthyosaurs, and other plesiosaurs. At least five other pliosaurids are known from the Peterborough Member, but they were quite varied in anatomy, indicating that they would have eaten different food sources, thereby avoiding competition.

History of research

Oxford Clay Formation

The Oxford Clay (or Oxford Clay Formation) is a Jurassic marine sedimentary rock formation underlying much of southeast England, from as far west as Dorset and as far north as Yorkshire. The Oxford Clay Formation dates to the Jurassic, specifica ...

have long been mined for brickmaking

A brick is a type of block used to build walls, pavements and other elements in masonry construction. Properly, the term ''brick'' denotes a block composed of dried clay, but is now also used informally to denote other chemically cured cons ...

. Ever since the late 19th century, when these operations began, the fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s of many marine animals have been excavated from the rocks. Among these was the specimen which would become the holotype

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of sever ...

of ''Peloneustes philarchus'', discovered by geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid, liquid, and gaseous matter that constitutes Earth and other terrestrial planets, as well as the processes that shape them. Geologists usually study geology, earth science, or geophysics, althoug ...

Henry Porter in a clay pit

A clay pit is a quarry or mine for the extraction of clay, which is generally used for manufacturing pottery, bricks or Portland cement. Quarries where clay is mined to make bricks are sometimes called brick pits.

A brickyard or brickworks is ...

close to Peterborough

Peterborough () is a cathedral city in Cambridgeshire, east of England. It is the largest part of the City of Peterborough unitary authority district (which covers a larger area than Peterborough itself). It was part of Northamptonshire until ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

. The specimen includes a mandible

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movable bone ...

, the front part of the upper jaw, various vertebrae

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates, Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristi ...

from throughout the body, elements from the shoulder girdle

The shoulder girdle or pectoral girdle is the set of bones in the appendicular skeleton which connects to the arm on each side. In humans it consists of the clavicle and scapula; in those species with three bones in the shoulder, it consists of ...

and pelvis, humeri

The humerus (; ) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extremity consists of a round ...

(upper arm bones), femora

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates with t ...

(upper leg bones), and various other limb bones. In 1866, geologist Adam Sedgwick purchased the specimen for the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209 and granted a royal charter by Henry III in 1231, Cambridge is the world's third oldest surviving university and one of its most pr ...

's Woodwardian Museum

The Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences, is the geology museum of the University of Cambridge. It is part of the Department of Earth Sciences and is located on the university's Downing Site in Downing Street, central Cambridge, England. The Sedgw ...

(now the Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences, Cambridge), with the specimen being catalogued as CAMSM J.46913 and stored in the university's lecture room within cabinet D. Palaeontologist

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

Harry Govier Seeley

Harry Govier Seeley (18 February 1839 – 8 January 1909) was a British paleontologist.

Early life

Seeley was born in London on 18 February 1839, the second son of Richard Hovill Seeley, a goldsmith, and his second wife Mary Govier. When his fat ...

described the specimen as a new species of the preexisting genus ''Plesiosaurus'', ''Plesiosaurus

''Plesiosaurus'' (Greek: ' ('), near to + ' ('), lizard) is a genus of extinct, large marine sauropterygian reptile that lived during the Early Jurassic. It is known by nearly complete skeletons from the Lias of England. It is distinguishable b ...

philarchus'', in 1869. The specific name means "power-loving", possibly due to its large, powerful skull. Seeley did not describe this specimen in detail, mainly just giving a list of the known material. While later publications would further describe these remains, CAMSM J.46913 remains poorly described.

Alfred Leeds and his brother Charles Leeds had been collecting fossils from the Oxford Clay since around 1867, encouraged by geologist John Phillips of the University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

, assembling what became known as the Leeds Collection. While Charles eventually left, Alfred, who collected the majority of the specimens, continued to gather fossils until 1917. Eventually, after a visit by Henry Woodward of the British Museum of Natural History

The Natural History Museum in London is a museum that exhibits a vast range of specimens from various segments of natural history. It is one of three major museums on Exhibition Road in South Kensington, the others being the Science Museum ...

(now the Natural History Museum in London) to Leeds' collection in Eyebury in 1885, the museum bought around of fossils in 1890. This brought Leeds' collection to wider renown, and he would later sell specimens to museums throughout Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

, and even some in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

. The carefully prepared material was usually in good condition, although it quite frequently had been crushed and broken by geological processes. Skulls were particularly vulnerable to this.

Naturalist

Naturalist Richard Lydekker

Richard Lydekker (; 25 July 1849 – 16 April 1915) was an English naturalist, geologist and writer of numerous books on natural history.

Biography

Richard Lydekker was born at Tavistock Square in London. His father was Gerard Wolfe Lydekker, ...

was informed of a plesiosaur skeleton in the British Museum of Natural History by geologist George Charles Crick, who worked there. The specimen, catalogued under NHMUK R1253, had been discovered in the Oxford Clay Formation in Green End, Kempston

Kempston is a town and Civil parishes in England, civil parish in the Borough of Bedford, Bedfordshire, England. It had a population of 19,330 in the 2011 census. Kempston is part of Bedford, Bedford's built-up area and is situated directly sout ...

, near Bedford

Bedford is a market town in Bedfordshire, England. At the 2011 Census, the population of the Bedford built-up area (including Biddenham and Kempston) was 106,940, making it the second-largest settlement in Bedfordshire, behind Luton, whilst ...

. While Lydekker speculated that the skeleton was once complete, it was damaged during excavation. The limb girdles had been heavily fragmented when the specimen arrived at the museum, but a worker named Lingard in the Geology Department managed to restore much of them. In addition to the limb girdles, the specimen also consists of a partial mandible, teeth, multiple vertebrae (although none from the neck), and much of the limbs. Lydekker identified this specimen as an individual of ''Plesiosaurus philarchus'' and published a description of it in 1889. After studying this and other specimens in the Leeds Collection, he concluded that plesiosaurs

The Plesiosauria (; Greek: πλησίος, ''plesios'', meaning "near to" and ''sauros'', meaning "lizard") or plesiosaurs are an order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared i ...

with shortened necks and large heads could not be classified as species of ''Plesiosaurus'', meaning that ''"P." philarchus'' belonged to a different genus. He initially assigned it to ''Thaumatosaurus

''Rhomaleosaurus'' (meaning "strong lizard") is an extinct genus of Early Jurassic (Toarcian age, about 183 to 175.6 million years ago) rhomaleosaurid pliosauroid known from Northamptonshire and from Yorkshire of the United Kingdom. It was fir ...

'' in 1888, but later decided that it was distinct enough to warrant its own genus, which he named ''Peloneustes'' in his 1889 publication. The name ''Peloneustes'' comes from the Greek words , meaning "mud" or "clay", in reference to the Oxford Clay Formation, and , meaning "swimmer". Seeley, however, lumped ''Peloneustes'' into ''Pliosaurus

''Pliosaurus'' (meaning 'more lizard') is an extinct genus of thalassophonean pliosaurid known from the Kimmeridgian and Tithonian stages (Late Jurassic) of Europe and South America. Their diet would have included fish, cephalopods, and marin ...

'' in 1892, claiming that the two were insufficiently different to warrant separate genera. Seeley and Lydekker could not agree on which genus to classify ''P. philarchus'' in, representing part of a feud between the two scientists. However, ''Peloneustes'' has since become the accepted name.

The Leeds Collection contained multiple ''Peloneustes'' specimens. In 1895, palaeontologist

The Leeds Collection contained multiple ''Peloneustes'' specimens. In 1895, palaeontologist Charles William Andrews

Charles William Andrews (30 October 1866 – 25 May 1924) F.R.S., was a British palaeontologist whose career as a vertebrate paleontologist, both as a curator and in the field, was spent in the services of the British Museum, Department of Ge ...

described the anatomy of the skull of ''Peloneustes'' based on four partial skulls in the Leeds Collection. In 1907, geologist Frédéric Jaccard published a description of two ''Peloneustes'' specimens from the Oxford Clay near Peterborough, housed in the Musée Paléontologique de Lausanne, Switzerland. The more complete of the two specimens includes a complete skull preserving both jaws; multiple isolated teeth; 13 cervical

In anatomy, cervical is an adjective that has two meanings:

# of or pertaining to any neck.

# of or pertaining to the female cervix: i.e., the ''neck'' of the uterus.

*Commonly used medical phrases involving the neck are

**cervical collar

**cerv ...

(neck), 5 pectoral (shoulder), and 7 caudal (tail) vertebrae; ribs; both scapulae, a coracoid

A coracoid (from Greek κόραξ, ''koraks'', raven) is a paired bone which is part of the shoulder assembly in all vertebrates except therian mammals (marsupials and placentals). In therian mammals (including humans), a coracoid process is prese ...

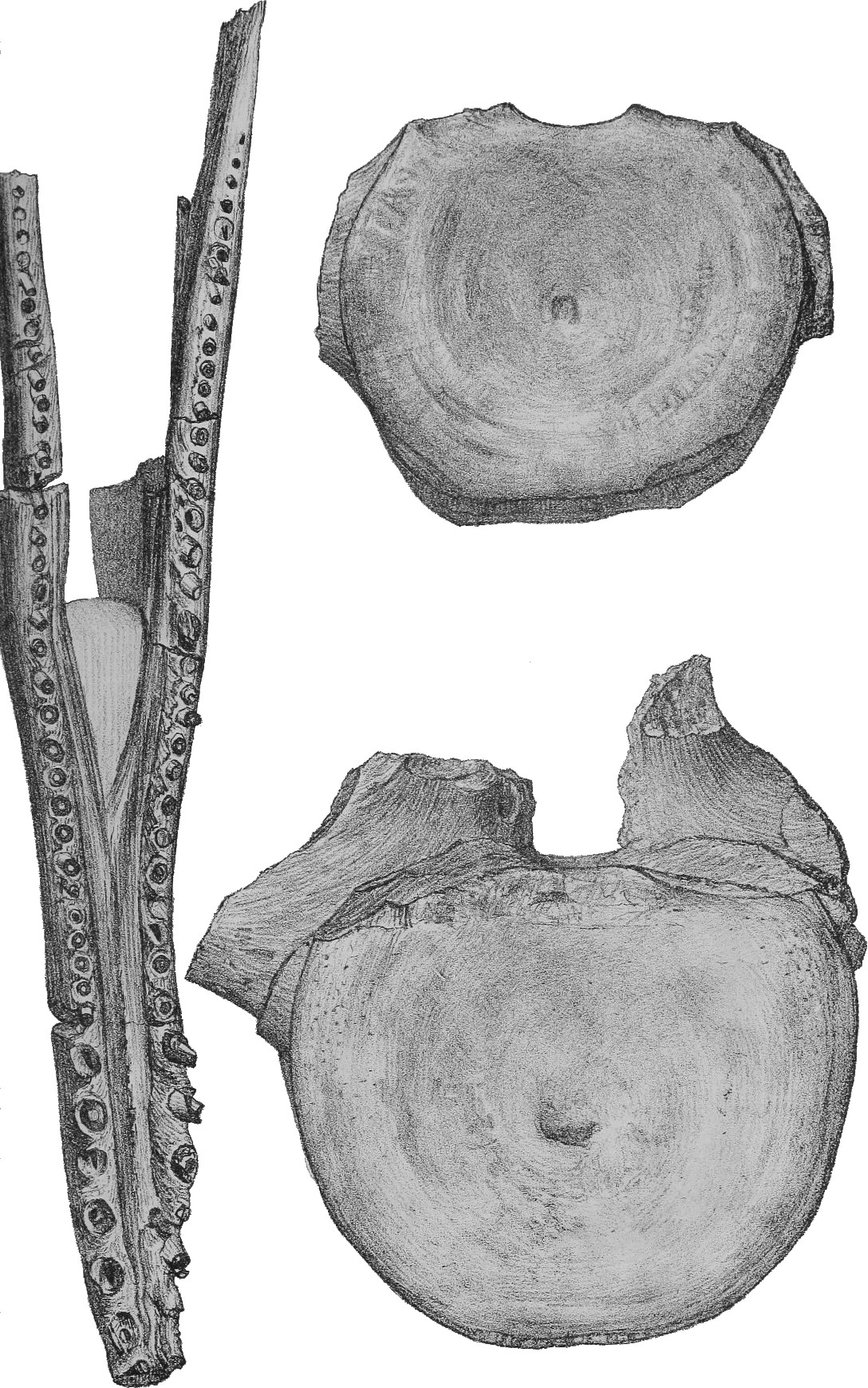

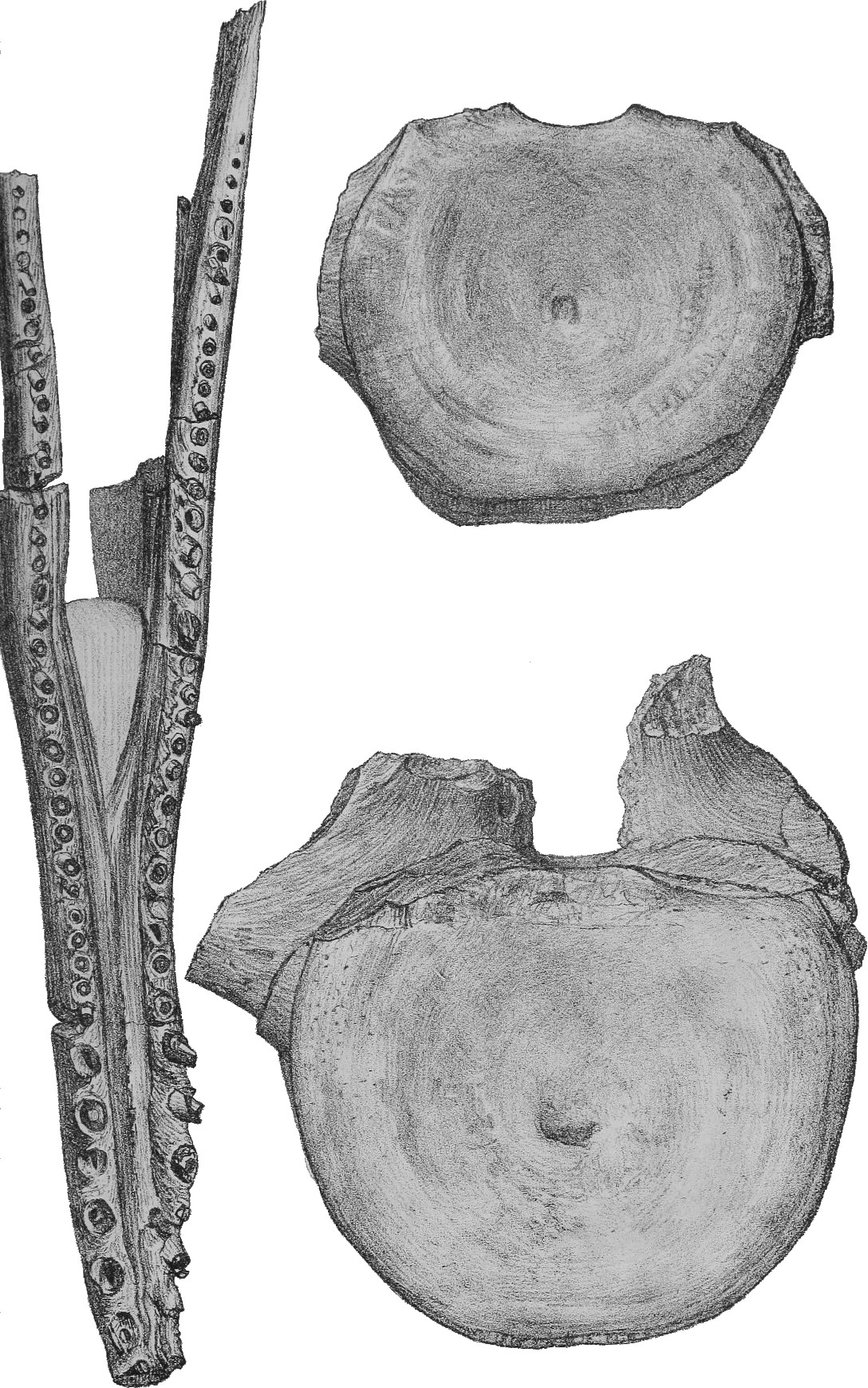

; a partial interclavicale; a complete pelvis save for an ischium; and all four limbs, which were nearly complete. The other specimen preserved 33 vertebrae and some associated ribs. Since the specimen Lydekker described was in some need of restoration, and missing information was filled in with data from other specimens in his publication, Jaccard found it pertinent to publish a description containing photographs of the more complete specimen in Lausanne to better illustrate the anatomy of ''Peloneustes''.

In 1913, naturalist Hermann Linder described multiple specimens of ''Peloneustes philarchus'' housed in the Institut für Geowissenschaften, University of Tübingen

The University of Tübingen, officially the Eberhard Karl University of Tübingen (german: Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen; la, Universitas Eberhardina Carolina), is a public research university located in the city of Tübingen, Baden-W� ...

and State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

. These specimens had also come from the Leeds Collection. Among the specimens he described from the former institution was a nearly complete mounted skeleton, lacking two cervical vertebrae, some caudal vertebrae from the end of the tail, and some distal phalanges. Only the rear part of the cranium was in good condition, but the mandible was mostly undamaged. Another of the specimens Linder described was a well-preserved skull (GPIT RE/3409), also from the University of Tübingen, preserving a sclerotic ring

Sclerotic rings are rings of bone found in the eyes of many animals in several groups of vertebrates, except for mammals and crocodilians. They can be made up of single bones or multiple segments and take their name from the sclera. They are bel ...

(the set of small bones that support the eye), only the fourth time these bones had been reported in a plesiosaur.

Andrews later described the marine reptile specimens of the Leeds Collection that were in the British Museum of Natural History, publishing two volumes, one in 1910 and the other in 1913. The anatomy of the ''Peloneustes'' specimens was described in the second volume, based primarily on the well-preserved skulls NHMUK R2679 and NHMUK R3808 and NHMUK R3318, an almost complete skeleton. NHMUK R3318 was so well preserved that it could be rearticulated and mounted, although the missing parts of the pelvis and limbs had to be filled in. The mounted skeleton was put on display in the museum's Gallery of Fossil Reptiles. Andrews had described this mount in 1910, remarking that it was the first skeletal mount of a pliosaurid

Pliosauridae is a family of plesiosaurian marine reptiles from the Latest Triassic to the early Late Cretaceous (Rhaetian to Turonian stages) of Australia, Europe, North America and South America. The family is more inclusive than the archetypal ...

, thus providing important information about the overall anatomy of the group.

In 1960, palaeontologist Lambert Beverly Tarlo published a review of pliosaurid species that had been reported from the Upper Jurassic. Many pliosaurids species had been named based on isolated fragments, creating confusion. Tarlo also found that inaccurate descriptions of the material and palaeontologists ignoring each other's work only made this confusion worse. Of the 36 species he reviewed, he only found nine of them to be valid, including ''Peloneustes philarchus''. In 2011, palaeontologists Hilary Ketchum and Roger Benson described the anatomy of the skull of ''Peloneustes''. Since the previous anatomical studies of Andrews and Linder, more specimens had been found, including NHMUK R4058, a skull preserved in three dimensions, providing a better idea of the skull's shape.

Other assigned species

Many further species have been assigned to ''Peloneustes'' throughout its history, but these have all since been reassigned to different genera or considered invalid. In the same publication in which he named ''P. philarchus'', Seeley also named anotherspecies

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

of ''Plesiosaurus'', ''P. sterrodeirus'' based on seven specimens in the Woodwardian Museum consisting of cranial and vertebral material. When Lydekker erected the genus ''Peloneustes'' for ''P. philarchus'', he also reclassified ''"Plesiosaurus" sterrodeirus'' and ''" Pleiosaurus" aequalis'' (a species named by John Phillips in 1871) as members of this genus. In his 1960 review of pliosaurid taxonomy

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. ...

, Tarlo considered ''P. aequalis'' to be invalid, since it was based on propodials (upper limb bones), which cannot be used to differentiate different pliosaurid species. He considered ''Peloneustes sterrodeirus'' to instead belong to ''Pliosaurus'', possibly within ''P. brachydeirus''.

Another of the species described by Seeley in 1869 was ''Pliosaurus evansi'', based on specimens in the Woodwardian Museum. These consisted of cervical and dorsal (back) vertebrae, ribs, and a coracoid. Due to it being a smaller species of ''Pliosaurus'' and its similarity to ''Peloneustes philarchus'', Lydekker reassigned it to ''Peloneustes'' in 1890, noting that it was larger than ''Peloneustes philarchus''. He also thought that a large mandible and paddle attributed to ''Pleiosaurus ?grandis'' by Phillips in 1871 belonged to this species instead. In 1913, Andrews assigned a partial skeleton of another large pliosaur found by Leeds to ''Peloneustes evansi'', noting that while the mandible and vertebrae were similar to other ''Peloneustes evansi'' specimens, they were quite different from those of ''Peloneustes philarchus''. Consequently, Andrews considered it possible that ''P. evansi'' really belonged to a separate genus that was morphologically intermediate between ''Peloneustes'' and ''Pliosaurus''. In his 1960 review of pliosaurids, Tarlo synonymised ''Peloneustes evansi'' with ''Peloneustes philarchus'' due to their cervical vertebrae being identical (save for a difference in size). He considered the larger specimens of ''Peloneustes evansi'' distinct, and assigned them to a new species of ''Pliosaurus'', ''P. andrewsi'' (although this species is no longer considered to belong in ''Pliosaurus''). Hilary F. Ketchum and Roger B. J. Benson disagreed with this synonymy, and in 2011 considered that since the holotype of ''Peloneustes evansi'' is nondiagnostic (lacking distinguishing features), ''P. evansi'' is a '' nomen dubium'' and therefore an indeterminate pliosaurid.

Palaeontologist E. Koken described another species of ''Peloneustes'', ''P. kanzleri'', in 1905, from the

Another of the species described by Seeley in 1869 was ''Pliosaurus evansi'', based on specimens in the Woodwardian Museum. These consisted of cervical and dorsal (back) vertebrae, ribs, and a coracoid. Due to it being a smaller species of ''Pliosaurus'' and its similarity to ''Peloneustes philarchus'', Lydekker reassigned it to ''Peloneustes'' in 1890, noting that it was larger than ''Peloneustes philarchus''. He also thought that a large mandible and paddle attributed to ''Pleiosaurus ?grandis'' by Phillips in 1871 belonged to this species instead. In 1913, Andrews assigned a partial skeleton of another large pliosaur found by Leeds to ''Peloneustes evansi'', noting that while the mandible and vertebrae were similar to other ''Peloneustes evansi'' specimens, they were quite different from those of ''Peloneustes philarchus''. Consequently, Andrews considered it possible that ''P. evansi'' really belonged to a separate genus that was morphologically intermediate between ''Peloneustes'' and ''Pliosaurus''. In his 1960 review of pliosaurids, Tarlo synonymised ''Peloneustes evansi'' with ''Peloneustes philarchus'' due to their cervical vertebrae being identical (save for a difference in size). He considered the larger specimens of ''Peloneustes evansi'' distinct, and assigned them to a new species of ''Pliosaurus'', ''P. andrewsi'' (although this species is no longer considered to belong in ''Pliosaurus''). Hilary F. Ketchum and Roger B. J. Benson disagreed with this synonymy, and in 2011 considered that since the holotype of ''Peloneustes evansi'' is nondiagnostic (lacking distinguishing features), ''P. evansi'' is a '' nomen dubium'' and therefore an indeterminate pliosaurid.

Palaeontologist E. Koken described another species of ''Peloneustes'', ''P. kanzleri'', in 1905, from the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

of Germany. In 1960, Tarlo reidentified this species as an elasmosaurid

Elasmosauridae is an extinct family of plesiosaurs, often called elasmosaurs. They had the longest necks of the plesiosaurs and existed from the Hauterivian to the Maastrichtian stages of the Cretaceous, and represented one of the two groups of ...

. In 1913, Linder created a subspecies of ''Peloneustes'', ''P. philarchus'' var. ''spathyrhynchus'', differentiating it based on its spatulate mandibular symphysis

A symphysis (, pl. symphyses) is a fibrocartilaginous fusion between two bones. It is a type of cartilaginous joint, specifically a secondary cartilaginous joint.

# A symphysis is an amphiarthrosis, a slightly movable joint.

# A growing togethe ...

(where the two sides of the mandible meet and fuse). Tarlo considered it to be a synonym of ''Peloneustes philarchus'' in 1960, and the mandibular symphysis of ''Peloneustes'' is proportionately wider in larger specimens, making this trait more likely to be due to intraspecific variation (variation within species). Crushing makes accurate measurement of these proportions difficult. In 1948, palaeontologist Nestor Novozhilov

Nestor Ivanovich Novozhilov was a Soviet paleontologist. In 1948, Novozhilov described a pliosaur specimen discovered on the banks of Russia's Volga Riveras a new species, ''Pliosaurus rossicus''. The specimen, while large, was damaged during the e ...

named a new species of ''Peloneustes'', ''P. irgisensis'', based on PIN 426, a partial skeleton consisting of a large, incomplete skull, vertebrae, and a partial hind limb, with stomach contents preserved. The specimen was unearthed in the Lower Volga Basin in Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

. In his 1960 review, Tarlo considered this species to be too different from ''Peloneustes philarchus'' to belong to ''Peloneustes'', tentatively placing it in ''Pliosaurus''. He speculated that Novozhilov had incorrectly thought ''Peloneustes'' to be the sole long-snouted pliosaurid, hence the initial assignment. In 1964 Novozhilov erected a new genus, '' Strongylokrotaphus'', for this species, but further studies concurred with Tarlo and reassigned the species to ''Pliosaurus'', possibly a synonym of ''Pliosaurus rossicus''. By then, PIN 426 had suffered from heavy pyrite

The mineral pyrite (), or iron pyrite, also known as fool's gold, is an iron sulfide with the chemical formula Fe S2 (iron (II) disulfide). Pyrite is the most abundant sulfide mineral.

Pyrite's metallic luster and pale brass-yellow hue giv ...

damage.

Lower Jurassic

The Early Jurassic Epoch (in chronostratigraphy corresponding to the Lower Jurassic Series) is the earliest of three epochs of the Jurassic Period. The Early Jurassic starts immediately after the Triassic-Jurassic extinction event, 201.3 Ma&nb ...

Posidonia Shale

The Posidonia Shale (german: Posidonienschiefer, also called Schistes Bitumineux in Luxembourg) geologically known as the Sachrang Formation, is an Early Jurassic (Toarcian) geological formation of southwestern and northeast Germany, northern Swit ...

of Germany might represent a new species of ''Peloneustes''. In 2001, he considered it to belong to a separate genus, naming it '' Hauffiosaurus zanoni''. Palaeontologists Zulma Gasparini and Manuel A. Iturralde-Vinent assigned a pliosaurid from the Upper Jurassic Jagua Formation of Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

to ''Peloneustes'' sp. in 2006. In 2009, Gasparini redescribed it as ''Gallardosaurus iturraldei

''Gallardosaurus'' is a genus of pliosaurid plesiosaur from the Caribbean seaway. It contains the single species ''Gallardosaurus iturraldei''. ''Gallardosaurus'' was found in middle-late Oxfordian stage, Oxfordian-age (Late Jurassic) rocks of t ...

''. In 2011, Ketchum and Benson considered ''Peloneustes'' to contain only one species, ''P. philarchus''. They recognised twenty one definite specimens of ''Peloneustes philarchus'', all from the Peterborough Member of the Oxford Clay Formation. They considered some specimens from the Peterborough Member and Marquise, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

previously assigned to ''Peloneustes'' to belong to different, currently unnamed pliosaurids.

Description

Skull

rostrum

Rostrum may refer to:

* Any kind of a platform for a speaker:

**dais

**pulpit

* Rostrum (anatomy), a beak, or anatomical structure resembling a beak, as in the mouthparts of many sucking insects

* Rostrum (ship), a form of bow on naval ships

* Ros ...

. The rearmost part of the cranium has roughly parallel sides, unlike the tapering front regions. The external nares (openings for the nostrils) are small and located about halfway along the length of the cranium. The kidney-shaped eye sockets

In anatomy, the orbit is the cavity or socket of the skull in which the eye and its appendages are situated. "Orbit" can refer to the bony socket, or it can also be used to imply the contents. In the adult human, the volume of the orbit is , o ...

face forwards and outwards and are located on the back half of the cranium. The sclerotic rings are composed of at least 16 individual elements, an unusually high number for a reptile. The temporal fenestrae

The skull is a bone protective cavity for the brain. The skull is composed of four types of bone i.e., cranial bones, facial bones, ear ossicles and hyoid bone. However two parts are more prominent: the cranium and the mandible. In humans, th ...

(openings in the back of the cranium) are enlarged, elliptical, and located on the cranium's rearmost quarter.

Characteristically, the

Characteristically, the premaxillae

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammal has b ...

(front upper tooth-bearing bones) of ''Peloneustes'' bear six teeth each, and the diastemata (gaps between teeth) of the upper jaw are narrow. While it has been stated that ''Peloneustes'' had nasals

In phonetics, a nasal, also called a nasal occlusive or nasal stop in contrast with an oral stop or nasalized consonant, is an occlusive consonant produced with a lowered velum, allowing air to escape freely through the nose. The vast majorit ...

(bones bordering the external nares), well-preserved specimens indicate that this is not the case. The frontals (bones bordering the eye sockets) of ''Peloneustes'' contact both the eye sockets and the external nares, a distinctive trait of ''Peloneustes''. There has been some contention as to whether or not ''Peloneustes'' had lacrimals (bones bordering the lower front edges of the eye sockets), due to poor preservation. However, well preserved specimens indicate that the lacrimals are distinct bones as in other pliosaurids, as opposed to extensions of the jugal

The jugal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians and birds. In mammals, the jugal is often called the malar or zygomatic. It is connected to the quadratojugal and maxilla, as well as other bones, which may vary by species.

Anatomy ...

s (bones bordering the lower rear edges of the eye sockets). The palate

The palate () is the roof of the mouth in humans and other mammals. It separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity.

A similar structure is found in crocodilians, but in most other tetrapods, the oral and nasal cavities are not truly separ ...

of ''Peloneustes'' is flat and bears many openings, including the internal nares (the opening of the nasal passage into the mouth). These openings are contacted by palatal bones known as palatines

Palatines (german: Pfälzer), also known as the Palatine Dutch, are the people and princes of Palatinates ( Holy Roman principalities) of the Holy Roman Empire. The Palatine diaspora includes the Pennsylvania Dutch and New York Dutch.

In 1709 ...

, a configuration used to identify this genus. The parasphenoid (a bone that forms the lower front part of the braincase) bears a long cultriform process (a frontwards projection of the braincase) that is visible when the palate is viewed from below, another distinctive characteristic of ''Peloneustes''. The occiput

The occipital bone () is a cranial dermal bone and the main bone of the occiput (back and lower part of the skull). It is trapezoidal in shape and curved on itself like a shallow dish. The occipital bone overlies the occipital lobes of the cereb ...

(rear part of the cranium) of ''Peloneustes'' is open, bearing large fenestrae.

''Peloneustes'' is known from many mandibles, some of which are well-preserved. The longest of these measures . The mandibular symphysis is elongated, making up about a third of the total mandibular length. Behind the symphysis, the two sides of the mandible diverge before gently curving back inwards near the hind end. Each dentary

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movable bone ...

(the tooth-bearing bone in the mandible) has between 36 and 44 teeth, 13 to 15 of which are located on the symphysis. The second to seventh tooth sockets (tooth sockets) are larger than those located further back, and the symphysis is the widest around the fifth and sixth. In addition to the characteristics of its mandibular teeth, ''Peloneustes'' can also be identified by its coronoids (upper inner mandibular bones), which contribute to the mandibular symphysis. Between the tooth rows, the mandibular symphysis bears an elevated ridge where the dentaries meet. This is a unique feature of ''Peloneustes'', not seen in any other plesiosaurs. The mandibular glenoid (socket of the jaw joint) is broad, kidney-shaped, and angled upwards and inwards.

The teeth of ''Peloneustes'' have circular cross sections, as seen in other pliosaurids of its age. The teeth have the shape of recurved

The teeth of ''Peloneustes'' have circular cross sections, as seen in other pliosaurids of its age. The teeth have the shape of recurved cone

A cone is a three-dimensional geometric shape that tapers smoothly from a flat base (frequently, though not necessarily, circular) to a point called the apex or vertex.

A cone is formed by a set of line segments, half-lines, or lines con ...

s. The enamel of the crowns

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, partic ...

bears regularly-spaced vertical ridges of varying length on all sides. These ridges are more concentrated on the concave edge of the teeth. Most of the ridges extend to one half to two-thirds of the total crown height, with few actually reaching the tooth's apex. The dentition of ''Peloneustes'' is heterodont, that is, it has teeth of different shapes. The larger teeth are caniniform and located at the front of the jaws, while the smaller teeth are more sharply recurved, stouter, and located further back.

Postcranial skeleton

In 1913, Andrews reported that ''Peloneustes'' had 21 to 22 cervical, 2 to 3 pectoral, and around 20

In 1913, Andrews reported that ''Peloneustes'' had 21 to 22 cervical, 2 to 3 pectoral, and around 20 dorsal

Dorsal (from Latin ''dorsum'' ‘back’) may refer to:

* Dorsal (anatomy), an anatomical term of location referring to the back or upper side of an organism or parts of an organism

* Dorsal, positioned on top of an aircraft's fuselage

* Dorsal c ...

vertebrae, with the exact number of sacral (hip) and caudal vertebrae unknown, based on specimens in the Leeds Collection. However, in the same year, Linder reported 19 cervical, 5 pectoral, 20 dorsal, 2 sacral, and at least 17 caudal vertebrae in ''Peloneustes'', based on a specimen in the Institut für Geowissenschaften, University of Tübingen. The first two cervical vertebrae, the atlas

An atlas is a collection of maps; it is typically a bundle of maps of Earth or of a region of Earth.

Atlases have traditionally been bound into book form, but today many atlases are in multimedia formats. In addition to presenting geograp ...

and axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

, are fused in adults, but in juveniles they are present as several unfused elements. The intercentrum (part of the vertebral body) of the axis is roughly rectangular, extending beneath the centrum

(Latin for ''center'') may refer to:

Places In Greenland

* Nuuk Centrum, a district of Nuuk, Greenland

* Centrum Lake, Greenland In the Netherlands

* Amsterdam-Centrum, the inner-most borough of Amsterdam, Netherlands

* Rotterdam Centrum, a borou ...

(vertebral body) of the atlas. The cervical vertebrae bear tall neural spine

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates,Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristic ...

s that are compressed from side to side. The cervical centra are about half as long as wide. They bear strongly concave articular surfaces, with a prominent rim around the lower edge in the vertebrae located towards the front of the series. Each cervical centrum has a strong keel along the midline of its underside. Most of the cervical rib

A cervical rib in humans is an extra rib which arises from the seventh cervical vertebra. Their presence is a congenital abnormality located above the normal first rib. A cervical rib is estimated to occur in 0.2% to 0.5% (1 in 200 to 500) of th ...

s bear two heads that are separated by a notch.

The pectoral vertebrae bear articulations for their respective ribs partially on both their centra and neural arches. Following these vertebrae are the dorsal vertebrae, which are more elongated than the cervical vertebrae and have shorter neural spines. The sacral and caudal vertebrae both have less elongated centra that are wider than tall. Many of the ribs from the hip and the base of the tail bear enlarged outer ends that seem to articulate with each other. Andrews hypothesised in 1913 that this configuration would have stiffened the tail, possibly to support the large hind limbs. The terminal (last) caudal vertebrae sharply decrease in size and would have supported proportionately larger chevrons

Chevron (often relating to V-shaped patterns) may refer to:

Science and technology

* Chevron (aerospace), sawtooth patterns on some jet engines

* Chevron (anatomy), a bone

* '' Eulithis testata'', a moth

* Chevron (geology), a fold in rock l ...

than the caudal vertebrae located further forwards. In 1913, Andrews speculated that this morphology may have been present to support a small tail fin-like structure. Other plesiosaurs have also been hypothesised to have tail fins, with impressions of such a structure possibly known in one species.

The shoulder girdle of ''Peloneustes'' was large, although not as heavily built as in some other plesiosaurs. The coracoids are the largest bones in the shoulder girdle, and are plate-like in form. The shoulder joint is formed by both the scapula

The scapula (plural scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on eith ...

(shoulder balde) and the coracoid, with the two bones forming a 70° angle with each other. The scapulae are typical in form for a pliosaurid and triradiate, bearing three prominent projections, or rami. The dorsal (upper) ramus is directed outwards, upwards, and backwards. The underside of each scapula bears a ridge directed towards the front edge of its ventral (lower) ramus. The ventral rami of the two scapulae were separated from each other by a triangular bone known as the interclavicle

An interclavicle is a bone which, in most tetrapods, is located between the clavicles. Therian mammals (marsupials and placentals) are the only tetrapods which never have an interclavicle, although some members of other groups also lack one. In t ...

. As seen in other pliosaurs, the pelvis of ''Peloneustes'' bears large and flat ischia and pubic bones

In vertebrates, the pubic region ( la, pubis) is the most forward-facing (ventral and anterior) of the three main regions making up the coxal bone. The left and right pubic regions are each made up of three sections, a superior ramus, inferior r ...

. The third pelvic bone, the ilium, is smaller and elongated, articulating with the ischium. The upper end of the ilium shows a large amount of variation within ''P. philarchus'', with two forms known, one with a rounded upper edge, the other with a flat upper edge and more angular shape.

The hind limbs of ''Peloneustes'' are longer than its forelimbs, with the femur being longer than the humerus, although the humerus is the more robust of the two elements. The radius

In classical geometry, a radius ( : radii) of a circle or sphere is any of the line segments from its center to its perimeter, and in more modern usage, it is also their length. The name comes from the latin ''radius'', meaning ray but also the ...

(one of the lower forelimb bones) is approximately as wide as it is long, unlike the ulna

The ulna (''pl''. ulnae or ulnas) is a long bone found in the forearm that stretches from the elbow to the smallest finger, and when in anatomical position, is found on the medial side of the forearm. That is, the ulna is on the same side of t ...

(the other lower forelimb bone), which is wider than long. The radius is the larger of these two elements. The tibia

The tibia (; ), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outside of the tibia); it connects ...

is larger than the fibula

The fibula or calf bone is a leg bone on the lateral side of the tibia, to which it is connected above and below. It is the smaller of the two bones and, in proportion to its length, the most slender of all the long bones. Its upper extremity i ...

(lower hindlimb bones) and longer than wide, while the fibula is wider than long in some specimens. The metacarpal

In human anatomy, the metacarpal bones or metacarpus form the intermediate part of the skeletal hand located between the phalanges of the fingers and the carpal bones of the wrist, which forms the connection to the forearm. The metacarpal bones ar ...

s, metatarsal

The metatarsal bones, or metatarsus, are a group of five long bones in the foot, located between the tarsal bones of the hind- and mid-foot and the phalanges of the toes. Lacking individual names, the metatarsal bones are numbered from the me ...

s, and the proximal manual phalanges (some of the bones making up the outer part of the paddle) are flattened. Most of the phalanges in both limbs have rounded cross-sections, and all of them have prominent constrictions in their middles. The number of phalanges in each digit is unknown in both the fore- and hind limbs.

Classification

Seeley initially described ''Peloneustes'' as a species of ''Plesiosaurus'', a rather common practice (at the time, the scope of genera was similar to what is currently used for

Seeley initially described ''Peloneustes'' as a species of ''Plesiosaurus'', a rather common practice (at the time, the scope of genera was similar to what is currently used for families

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Ideal ...

). In 1874, Seeley named a new family of plesiosaurs, Pliosauridae, to contain forms similar to ''Pliosaurus''. In 1890, Lydekker placed ''Peloneustes'' in this family, to which it has been consistently assigned since. Exactly how pliosaurids are related to other plesiosaurs is uncertain. In 1940, palaeontologist Theodore E. White considered pliosaurids to be close relatives of Elasmosauridae based on shoulder anatomy. Palaeontologist Samuel P. Welles, however, thought that pliosaurids were more similar to Polycotylidae

Polycotylidae is a family of plesiosaurs from the Cretaceous, a sister group to Leptocleididae. Polycotylids first appeared during the Albian stage of the Early Cretaceous, before becoming abundant and widespread during the early Late Cretaceous. ...

, as they both had large skulls and short necks, among other characteristics. He grouped these two families into the superfamily Pliosauroidea

Pliosauroidea is an extinct clade of plesiosaurs, known from the earliest Jurassic to early Late Cretaceous. They are best known for the subclade Thalassophonea, which contained crocodile-like short-necked forms with large heads and massive t ...

, with other plesiosaurs forming the superfamily Plesiosauroidea

Plesiosauroidea (; Greek: 'near, close to' and 'lizard') is an extinct clade of carnivorous marine reptiles. They have the snake-like longest neck to body ratio of any reptile. Plesiosauroids are known from the Jurassic and Cretaceous period ...

. Another plesiosaur family, Rhomaleosauridae, has since been assigned to Pliosauroidea, while Polycotylidae has been reassigned to Plesiosauroidea. However, in 2012, Benson and colleagues recovered a different topology, with Pliosauridae being more closely related to Plesiosauroidea than Rhomaleosauridae. This pliosaurid-plesiosauroid clade was termed Neoplesiosauria.

Within Pliosauridae, the exact phylogenetic position of ''Peloneustes'' is uncertain. In 1889, Lydekker considered ''Peloneustes'' to represent a transitional form between ''Pliosaurus'' and earlier plesiosaurs, although he found it unlikely that ''Peloneustes'' was ancestral to ''Pliosaurus''. In 1960, Tarlo considered ''Peloneustes'' to be a close relative of ''Pliosaurus'', since both taxa had elongated mandibular symphyses. In 2001, O'Keefe and colleagues recovered it as a basal (early-diverging) member of this family, outside of a group including ''

Within Pliosauridae, the exact phylogenetic position of ''Peloneustes'' is uncertain. In 1889, Lydekker considered ''Peloneustes'' to represent a transitional form between ''Pliosaurus'' and earlier plesiosaurs, although he found it unlikely that ''Peloneustes'' was ancestral to ''Pliosaurus''. In 1960, Tarlo considered ''Peloneustes'' to be a close relative of ''Pliosaurus'', since both taxa had elongated mandibular symphyses. In 2001, O'Keefe and colleagues recovered it as a basal (early-diverging) member of this family, outside of a group including ''Liopleurodon

''Liopleurodon'' (; meaning 'smooth-sided teeth') is an extinct genus of large, carnivorous marine reptile belonging to the Thalassophonea, a clade of short-necked pliosaurid plesiosaurs. ''Liopleurodon'' lived from the Callovian Stage of the Mi ...

'', ''Pliosaurus'', and '' Brachauchenius''. However, in 2008, palaeontologists Adam S. Smith and Gareth J. Dyke found ''Peloneustes'' to be the sister taxon

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and ...

of ''Pliosaurus''. In 2013, Benson and palaeontologist Patrick S. Druckenmiller named a new clade within Pliosauridae, Thalassophonea

Thalassophonea is an extinct clade of pliosaurids from the Middle Jurassic to the early Late Cretaceous ( Callovian to Turonian) of Australia, Europe, North America and South America. ''Thalassophonea'' was erected by Roger Benson and Patrick ...

. This clade included the "classic", short-necked pliosaurids while excluding the earlier, long-necked, more gracile forms. ''Peloneustes'' was found to be the most basal thalassophonean. Subsequent studies have uncovered a similar position for ''Peloneustes''.

The following cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an evolutionary tree because it does not show how ancestors are related to ...

follows Valentin Fischer and colleagues, 2017.

Palaeobiology

Plesiosaurs were well-adapted to marine life. They grew at rates comparable to those of birds and had high

Plesiosaurs were well-adapted to marine life. They grew at rates comparable to those of birds and had high metabolism

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run c ...

s, indicating homeothermy

Homeothermy, homothermy or homoiothermy is thermoregulation that maintains a stable internal body temperature regardless of external influence. This internal body temperature is often, though not necessarily, higher than the immediate environmen ...

or even endothermy

An endotherm (from Greek ἔνδον ''endon'' "within" and θέρμη ''thermē'' "heat") is an organism that maintains its body at a metabolically favorable temperature, largely by the use of heat released by its internal bodily functions inste ...

. The bony labyrinth

The bony labyrinth (also osseous labyrinth or otic capsule) is the rigid, bony outer wall of the inner ear in the temporal bone. It consists of three parts: the vestibule, semicircular canals, and cochlea. These are cavities hollowed out of the su ...

, a hollow within the skull which held a sensory organ associated with balance and orientation, of ''Peloneustes'' and other plesiosaurs is similar in shape to that of sea turtle

Sea turtles (superfamily Chelonioidea), sometimes called marine turtles, are reptiles of the order Testudines and of the suborder Cryptodira. The seven existing species of sea turtles are the flatback, green, hawksbill, leatherback, loggerhe ...

s. Palaeontologist James Neenan and colleagues hypothesised in 2017 that this shape probably evolved alongside the flapping motions used by plesiosaurs to swim. ''Peloneustes'' and other short-necked plesiosaurs also had smaller labyrinths than plesiosaurs with longer necks, a pattern also seen in cetaceans. Additionally, ''Peloneustes'' probably had salt gland

The salt gland is an organ for excreting excess salts. It is found in the cartilaginous fishes subclass elasmobranchii (sharks, rays, and skates), seabirds, and some reptiles. Salt glands can be found in the rectum of sharks. Birds and reptiles ...

s in its head to cope with excess amount of salt within its body. However, ''Peloneustes'' appears to have been a predator of vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () (chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, with c ...

s, which contain less salt than invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordate ...

s, therefore leading palaeontologist Leslie Noè to suggest in a 2001 dissertation that these glands would not have had to be especially large. ''Peloneustes'', like many other pliosaurs, displayed a reduced level of ossification

Ossification (also called osteogenesis or bone mineralization) in bone remodeling is the process of laying down new bone material by cells named osteoblasts. It is synonymous with bone tissue formation. There are two processes resulting in ...

of its bones. Palaeontologist Arthur Cruickshank and colleagues in 1966 proposed that this may have helped ''Peloneustes'' maintain its buoyancy

Buoyancy (), or upthrust, is an upward force exerted by a fluid that opposes the weight of a partially or fully immersed object. In a column of fluid, pressure increases with depth as a result of the weight of the overlying fluid. Thus the ...

or improved its maneuverability. A 2019 study by palaeontologist Corinna Fleischle and colleagues found that plesiosaurs had enlarged red blood cell

Red blood cells (RBCs), also referred to as red cells, red blood corpuscles (in humans or other animals not having nucleus in red blood cells), haematids, erythroid cells or erythrocytes (from Greek ''erythros'' for "red" and ''kytos'' for "holl ...

s, based on the morphology of their vascular canals, which would have aided them while diving.

Plesiosaurs such as ''Peloneustes'' employed a method of swimming known as subaqueous flight, using their flippers as hydrofoils. Plesiosaurs are unusual among marine reptiles in that they utilised all four of their limbs, but not movements of the vertebral column, for propulsion. The short tail, while unlikely to have been used for swimming, could have helped stabilize or steer the plesiosaur. The front flippers of ''Peloneustes'' have aspect ratios of 6.36, while the rear flippers have aspect ratios of 8.32. These ratios are similar to those of the wings of modern falcon

Falcons () are birds of prey in the genus ''Falco'', which includes about 40 species. Falcons are widely distributed on all continents of the world except Antarctica, though closely related raptors did occur there in the Eocene.

Adult falcons ...

s. In 2001, O'Keefe proposed that, much like falcons, pliosauromorph plesiosaurs such as ''Peloneustes'' probably were capable of moving quickly and nimbly, albeit inefficiently, in order to capture prey. Computer modelling by palaeontologist Susana Gutarra and colleagues in 2022 found that due to their large flippers, a plesiosaur would have produced more drag than a comparably-sized cetacean or ichthyosaur. However, plesiosaurs counteracted this with their large trunks and body size. Due to the reduction in drag by their shorter, deeper bodies, palaeontologist Judy Massare

Judy is a short form of the name Judith.

Judy may refer to:

Places

* Judy, Kentucky, village in Montgomery County, United States

* Judy Woods, woodlands in Bradford, West Yorkshire, England, United Kingdom

Animals

* Judy (dog) (1936–1950) ...

propsed in 1988 that plesiosaurs could actively search for and pursue their food instead of having to lie in wait for it.

Feeding mechanics

In a 2001 dissertation, Noè noted many adaptations in pliosaurid skulls for predation. To avoid damage while feeding, the skulls of pliosaurids like ''Peloneustes'' are highly akinetic, where the bones of the cranium and mandible were largely locked in place to prevent movement. The snout contains elongated bones that helped to prevent bending and bears a reinforced junction with the facial region to better resist the stresses of feeding. When viewed from the side, little tapering is visible in the mandible, strengthening it. The mandibular symphysis would have helped deliver an even bite and prevent the mandibles from moving independently. The enlarged coronoid eminence provides a large, strong region for the anchorage of the jaw muscles, although this structure is not as large in ''Peloneustes'' as it is in other contemporary pliosaurids. The regions where the jaw muscles were anchored are located further back on the skull to avoid interference with feeding. The kidney-shaped mandibular glenoid would have made the jaw joint steadier and stopped the mandible from dislocating. Pliosaurid teeth are firmly rooted and interlocking, which strengthens the edges of the jaws. This configuration also works well with the simple rotational movements that pliosaurid jaws were limited to and strengthens the teeth against the struggles of prey. The larger front teeth would have been used to impale prey while the smaller rear teeth crushed and guided the prey backwards toward the throat. With their wide gapes, pliosaurids would not have processed their food very much before swallowing.