Louvre 032007 15.jpg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Trois têtes d'hommes en relation avec le lion.jpg, Three lion-like heads; by

The Louvre is owned by the French government. Since the 1990s, its management and governance have been made more independent. Since 2003, the museum has been required to generate funds for projects. By 2006, government funds had dipped from 75 percent of the total budget to 62 percent. Every year, the Louvre now raises as much as it gets from the state, about €122 million. The government pays for operating costs (salaries, safety, and maintenance), while the rest – new wings, refurbishments, acquisitions – is up to the museum to finance.Farah Nayeri (20 January 2009)

The Louvre is owned by the French government. Since the 1990s, its management and governance have been made more independent. Since 2003, the museum has been required to generate funds for projects. By 2006, government funds had dipped from 75 percent of the total budget to 62 percent. Every year, the Louvre now raises as much as it gets from the state, about €122 million. The government pays for operating costs (salaries, safety, and maintenance), while the rest – new wings, refurbishments, acquisitions – is up to the museum to finance.Farah Nayeri (20 January 2009)

Banks compete to manage Louvre's endowment

'' International Herald Tribune''. A further €3 million to €5 million a year is raised by the Louvre from exhibitions that it curates for other museums, while the host museum keeps the ticket money. As the Louvre became a point of interest in the book ''

Louvre's superstore to go ahead despite protests

''

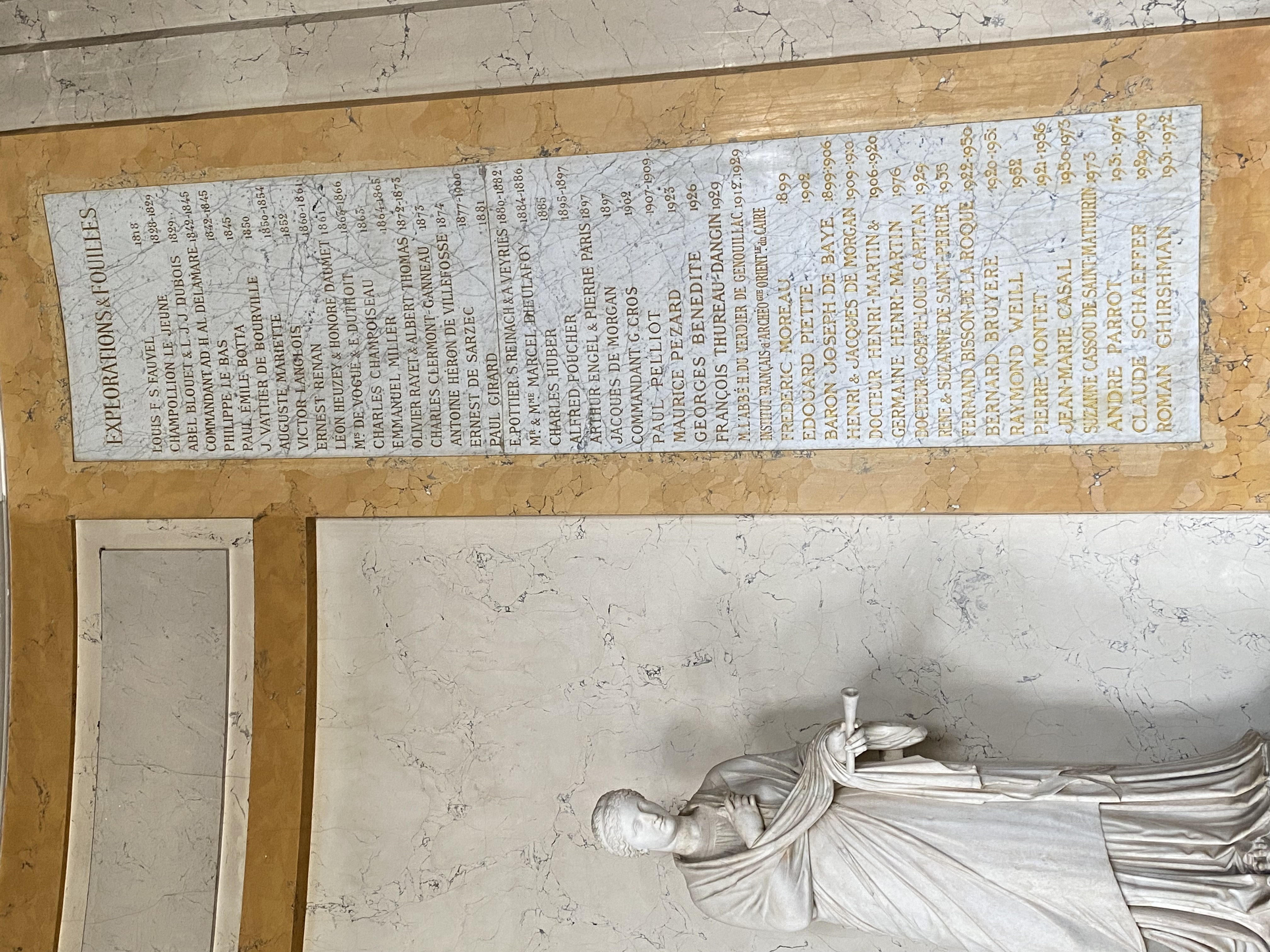

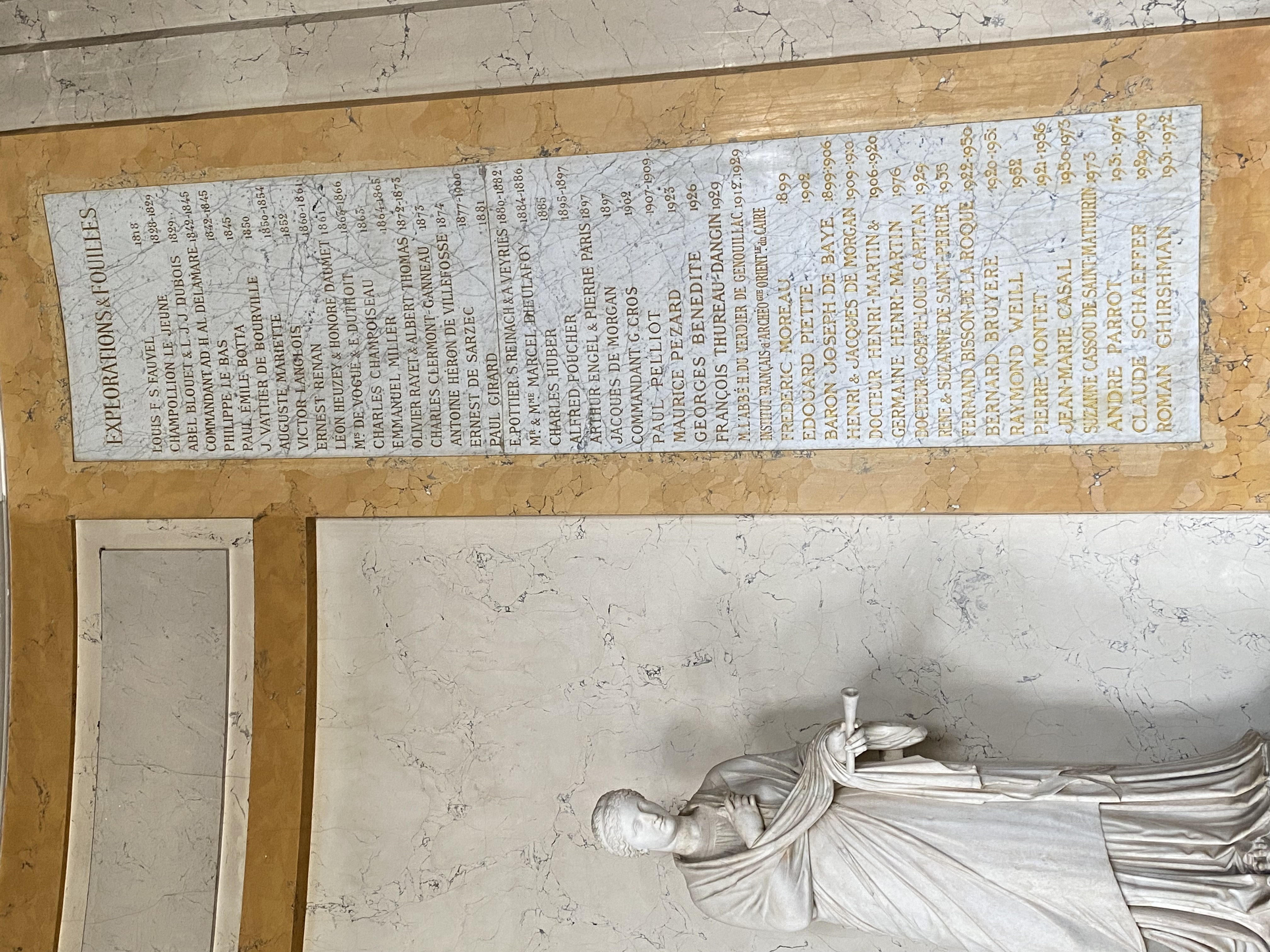

The Louvre's ancient art collections are to a significant extent the product of excavations, some of which the museum sponsored under various legal regimes over time, often as a companion to France's diplomacy and/or colonial enterprises. In the , a carved marble panel lists a number of such campaigns, led by:

* Louis-François-Sébastien Fauvel in Greece (1818)

* Jean-François Champollion in Egypt (1828-1829)

*

The Louvre's ancient art collections are to a significant extent the product of excavations, some of which the museum sponsored under various legal regimes over time, often as a companion to France's diplomacy and/or colonial enterprises. In the , a carved marble panel lists a number of such campaigns, led by:

* Louis-François-Sébastien Fauvel in Greece (1818)

* Jean-François Champollion in Egypt (1828-1829)

*

:What Is Frank Gehry Doing About Labor Conditions in Abu Dhabi?"

''Architectural Record'', September 25, 2014 In 2010, the Guggenheim Foundation placed on its website a joint statement with Abu Dhabi’s Tourism Development and Investment Company (TDIC) recognizing the following workers' rights issues, among others: health and safety of the workers; their access to their passports and other documents that the employers have been retaining to guaranty that they stay on the job; using a general contractor that agrees to obey the labor laws; maintaining an independent site monitor; and ending the system that has been generally used in the Persian Gulf region of requiring workers to reimburse recruitment fees. In 2013, ''The Observer'' reported that conditions for the workers at the Louvre and New York University construction sites on Saadiyat amounted to "modern-day slavery".Carrick, Glenn and David Batty

"In Abu Dhabi, they call it Happiness Island. But for the migrant workers, it is a place of misery"

''The Observer'', 22 December 2013, accessed 30 June 2014; Batty, David

"Conditions for Abu Dhabi's migrant workers 'shame the west'"

''The Observer'', 22 December 2013, accessed 1 December 2014; Batty, David

"Campaigners criticise UAE for failing to tackle exploitation of migrant workers"

''The Observer'', 22 December 2013, accessed 30 June 2014 In 2014, the Guggenheim's Director, Richard Armstrong (museum director), Richard Armstrong, said that he believed that living conditions for the workers at the Louvre project were now good and that "many fewer" of them were having their passports confiscated. He stated that the main issue then remaining was the recruitment fees charged to workers by agents who recruit them.Kaminer, Ariel and Sean O'Driscoll

"Workers at N.Y.U.’s Abu Dhabi Site Faced Harsh Conditions"

''The New York Times'', 18 May 2014 Later in 2014, the Guggenheim's architect, Gehry, commented that working with the Abu Dhabi officials to implement the law to improve the labor conditions at the museum's site is "a moral responsibility." He encouraged the TDIC to build additional worker housing and proposed that the contractor cover the cost of the recruitment fees. In 2012, TDIC engaged PricewaterhouseCoopers as an independent monitor required to issue reports every quarter. Labor lawyer Scott Horton told ''Architectural Record'' that he hoped the Guggenheim project will influence the treatment of workers on other Saadiyat sites and will "serve as a model for doing things right."Rosenbaum, Lee

"Guggenheim Abu Dhabi Still Stalled, as Monitoring Report Is Issued on Saadiyat Island Labor Conditions"

CultureGrrl, ArtsJournal.com, February 4, 2016

Digital CollectionLouvre's 360x180 degree panorama virtual tour

{{Good article Louvre, 1793 establishments in France Archaeological museums in France Art museums and galleries in Paris Art museums established in 1793 Egyptological collections in France History museums in France Institut de France Louvre Palace Museums in Paris Museums of ancient Greece in France Museums of Ancient Near East in France Museums of ancient Rome in France National museums of France Order of Arts and Letters of Spain recipients

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is the world's most-visited museum, and an historic landmark in

The Louvre museum is located inside the Louvre Palace, in the center of Paris, adjacent to the

The Louvre museum is located inside the Louvre Palace, in the center of Paris, adjacent to the

The Louvre Palace, which houses the museum, was begun by King Philip II in the late 12th century to protect the city from the attack from the West, as the

The Louvre Palace, which houses the museum, was begun by King Philip II in the late 12th century to protect the city from the attack from the West, as the

The museum opened on 10 August 1793, the first anniversary of the monarchy's demise, as ''Muséum central des arts de la République''. The public was given free accessibility on three days per week, which was "perceived as a major accomplishment and was generally appreciated". The collection showcased 537 paintings and 184 objects of art. Three quarters were derived from the royal collections, the remainder from confiscated émigrés and

The museum opened on 10 August 1793, the first anniversary of the monarchy's demise, as ''Muséum central des arts de la République''. The public was given free accessibility on three days per week, which was "perceived as a major accomplishment and was generally appreciated". The collection showcased 537 paintings and 184 objects of art. Three quarters were derived from the royal collections, the remainder from confiscated émigrés and

For most of the 19th century, from

For most of the 19th century, from

File:Dernière salle des antiquités égyptiennes (Louvre).jpg, First room

File:Egyptian antiquities in the Louvre - Room 27 and others.jpg, Room 27

File:Egyptian antiquities in the Louvre - Room 29 D201903.jpg, Room 29

File:Salles des colonnes du Louvre, vue vers l'ouest.jpg, Salle des Colonnes

File:Greek antiquities in the Louvre - Room 35 D201903.jpg, Room 35

File:Room 36 of the Greek antiquities in the Louvre.jpg, Room 36

File:Greek antiquities in the Louvre - Room 38 D201903.jpg, Room 38

Following the

File:Musée Napoléon III.jpg, Entrance to a section of the ''Musée Napoléon III'' from the ''salle des séances'', then a double-height space

File:Galerie Daru - Musée du Louvre.jpg, ''Galerie Daru'', part of the New Louvre building program under Napoleon III

File:Paris - Musée du Louvre (30612872064).jpg, ''Salle Daru'' above the ''galerie Daru'', also created under Napoleon III

File:LOUVRE Museum (interior) Paris (1).jpg, ''Escalier Mollien'' in the New Louvre

File:P1080712 Louvre salle romaine rwk.JPG, ''Salle des Empereurs''

The Louvre narrowly escaped serious damage during the suppression of the

The Louvre narrowly escaped serious damage during the suppression of the  Meanwhile, during the Third Republic (1870–1940) the Louvre acquired new artefacts mainly via donations, gifts, and sharing arrangements on excavations abroad. The 583-item , donated in 1869 by

Meanwhile, during the Third Republic (1870–1940) the Louvre acquired new artefacts mainly via donations, gifts, and sharing arrangements on excavations abroad. The 583-item , donated in 1869 by  In the late 1920s, Louvre Director

In the late 1920s, Louvre Director

File:Louvre Courtyard, Looking West.jpg, The Napoleon Courtyard and

President Jacques Chirac, who had succeeded Mitterrand in 1995, insisted on the return of non-Western art to the Louvre, upon a recommendation from his friend the art collector and dealer . On his initiative, a selection of highlights from the collections of what would become the Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac was installed on the ground floor of the and opened in 2000, six years ahead of the Musée du Quai Branly itself.

The main other initiative in the aftermath of the Grand Louvre project was Chirac's decision to create a new department of Islamic Art, by executive order of 1 August 2003, and to move the corresponding collections from their prior underground location in the Richelieu Wing to a more prominent site in the Denon Wing. That new section opened on 22 September 2012, together with collections from the Roman-era Eastern Mediterranean, with financial support from the Al Waleed bin Talal Foundation and on a design by

President Jacques Chirac, who had succeeded Mitterrand in 1995, insisted on the return of non-Western art to the Louvre, upon a recommendation from his friend the art collector and dealer . On his initiative, a selection of highlights from the collections of what would become the Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac was installed on the ground floor of the and opened in 2000, six years ahead of the Musée du Quai Branly itself.

The main other initiative in the aftermath of the Grand Louvre project was Chirac's decision to create a new department of Islamic Art, by executive order of 1 August 2003, and to move the corresponding collections from their prior underground location in the Richelieu Wing to a more prominent site in the Denon Wing. That new section opened on 22 September 2012, together with collections from the Roman-era Eastern Mediterranean, with financial support from the Al Waleed bin Talal Foundation and on a design by

Islamic art, covered

''

File:Pavillon des Sessions 01.jpg, The 's display of non-Western art from the Musée du Quai Branly, opened in 2000

File:Cour Visconti (Louvre) D201512a.jpg, The 's ground floor covered to host the new Islamic Art Department in 2012

File:Les arts de lIslam au Louvre (8055981963).jpg, Islamic art display in the covered , 2012

File:Louvre, dipartimento di arte islamica, 01.JPG, Underground display of the Islamic Art Department, 2012

p. 29, website www.louvre.fr. of which 482,943 are accessible online since 24 March 2021 and displays 35,000 works of art in eight curatorial departments.

Gebel el-Arak knife mp3h8783-cropped.jpg, The ''

Cup Idalion Louvre N3455.jpg,

The Greek, Etruscan, and Roman department displays pieces from the Mediterranean Basin dating from the

The Greek, Etruscan, and Roman department displays pieces from the Mediterranean Basin dating from the

Head figurine Spedos Louvre Ma2709.jpg,

Spagna, cordoba, pisside col nome di al-mughina, avorio, X sec. 04.JPG, The ''

The sculpture department consists of works created before 1850 not belonging in the Etruscan, Greek, and Roman department. The Louvre has been a repository of sculpted material since its time as a palace; however, only ancient architecture was displayed until 1824, except for Michelangelo's ''

The sculpture department consists of works created before 1850 not belonging in the Etruscan, Greek, and Roman department. The Louvre has been a repository of sculpted material since its time as a palace; however, only ancient architecture was displayed until 1824, except for Michelangelo's ''

Tomb of Philippe Pot, Right Side - Louvre, Room 10.jpg, The ''

Armoire Louvre OA 6968.jpg, Henry II style wardrobe; circa 1580; walnut and oak, partially gilded and painted; height: 2.06 m, width: 1.50 m, depth: 0.60 m

Musée du Louvre - Département des Objets d'art - Salle 34 -2.JPG,

The painting collection has more than 7,500 works from the 13th century to 1848 and is managed by 12 curators who oversee the collection's display. Nearly two-thirds are by French artists, and more than 1,200 are Northern European. The Italian paintings compose most of the remnants of Francis I and Louis XIV's collections, others are unreturned artwork from the Napoleon era, and some were bought. The collection began with Francis, who acquired works from Italian masters such as

The painting collection has more than 7,500 works from the 13th century to 1848 and is managed by 12 curators who oversee the collection's display. Nearly two-thirds are by French artists, and more than 1,200 are Northern European. The Italian paintings compose most of the remnants of Francis I and Louis XIV's collections, others are unreturned artwork from the Napoleon era, and some were bought. The collection began with Francis, who acquired works from Italian masters such as

Quentin Massys 001.jpg, '' The Money Changer and His Wife''; by

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially res ...

purchased by François I">

Virgin of the Rocks (Louvre).jpg,

Leonardo da Vinci - Virgin and Child with St Anne C2RMF retouched.jpg,

Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

. It is the home of some of the best-known works of art, including the ''Mona Lisa

The ''Mona Lisa'' ( ; it, Gioconda or ; french: Joconde ) is a Half length portrait, half-length portrait painting by Italian artist Leonardo da Vinci. Considered an archetypal masterpiece of the Italian Renaissance, it has been described ...

'' and the ''Venus de Milo

The ''Venus de Milo'' (; el, Αφροδίτη της Μήλου, Afrodíti tis Mílou) is an ancient Greek sculpture that was created during the Hellenistic period, sometime between 150 and 125 BC. It is one of the most famous works of ancient ...

''. A central landmark of the city, it is located on the Right Bank

In geography, a bank is the land alongside a body of water. Different structures are referred to as ''banks'' in different fields of geography, as follows.

In limnology (the study of inland waters), a stream bank or river bank is the terrai ...

of the Seine in the city's 1st arrondissement (district or ward). At any given point in time, approximately 38,000 objects from prehistory to the 21st century are being exhibited over an area of 72,735 square meters (782,910 square feet). Attendance in 2021 was 2.8 million due to the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic, also known as the coronavirus pandemic, is an ongoing global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The novel virus was first identi ...

, up five percent from 2020, but far below pre-COVID attendance. Nonetheless, the Louvre still topped the list of most-visited art museums

This article lists the most-visited art museums in the world in 2021. The primary source is '' The Art Newspaper'' annual survey of the number of visitors to major art museums in 2021, published 28 March 2022.

Total attendance in the top one hu ...

in the world in 2021."The Art Newspaper", 30 March 2021.

The museum is housed in the Louvre Palace, originally built in the late 12th to 13th century under Philip II. Remnants of the Medieval Louvre

The Louvre Castle (french: Château fort du Louvre), also known as the Medieval Louvre (french: Louvre médiéval, links=no), was a castle (french: château fort, links=no) built by King Philip II of France on the right bank of the Seine, to rei ...

fortress are visible in the basement of the museum. Due to urban expansion, the fortress eventually lost its defensive function, and in 1546 Francis I converted it into the primary residence of the French Kings

France was ruled by Monarch, monarchs from the establishment of the West Francia, Kingdom of West Francia in 843 until the end of the Second French Empire in 1870, with several interruptions.

Classical French historiography usually regards Cl ...

. The building was extended many times to form the present Louvre Palace. In 1682, Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Ver ...

chose the Palace of Versailles for his household, leaving the Louvre primarily as a place to display the royal collection, including, from 1692, a collection of ancient Greek and Roman sculpture. In 1692, the building was occupied by the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres

The Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres () is a French learned society devoted to history, founded in February 1663 as one of the five academies of the Institut de France. The academy's scope was the study of ancient inscriptions (epigr ...

and the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, which in 1699 held the first of a series of salons. The Académie remained at the Louvre for 100 years. During the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

, the National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the rep ...

decreed that the Louvre should be used as a museum to display the nation's masterpieces.

The museum opened on 10 August 1793 with an exhibition of 537 paintings, the majority of the works being royal and confiscated church property. Because of structural problems with the building, the museum was closed in 1796 until 1801. The collection was increased under Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

and the museum was renamed ''Musée Napoléon'', but after Napoleon's abdication, many works seized by his armies were returned to their original owners. The collection was further increased during the reigns of Louis XVIII

Louis XVIII (Louis Stanislas Xavier; 17 November 1755 – 16 September 1824), known as the Desired (), was King of France from 1814 to 1824, except for a brief interruption during the Hundred Days in 1815. He spent twenty-three years in ...

and Charles X

Charles X (born Charles Philippe, Count of Artois; 9 October 1757 – 6 November 1836) was King of France from 16 September 1824 until 2 August 1830. An uncle of the uncrowned Louis XVII and younger brother to reigning kings Louis XVI and Lou ...

, and during the Second French Empire

The Second French Empire (; officially the French Empire, ), was the 18-year Imperial Bonapartist regime of Napoleon III from 14 January 1852 to 27 October 1870, between the Second and the Third Republic of France.

Historians in the 1930 ...

the museum gained 20,000 pieces. Holdings have grown steadily through donations and bequests since the Third Republic. The collection is divided among eight curatorial departments: Egyptian Antiquities

Egyptology (from ''Egypt'' and Greek , ''-logia''; ar, علم المصريات) is the study of ancient Egyptian history, language, literature, religion, architecture and art from the 5th millennium BC until the end of its native religious p ...

; Near Eastern Antiquities; Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, Etruscan __NOTOC__

Etruscan may refer to:

Ancient civilization

*The Etruscan language, an extinct language in ancient Italy

*Something derived from or related to the Etruscan civilization

**Etruscan architecture

**Etruscan art

**Etruscan cities

** Etrusca ...

, and Roman Antiquities

Dionysius of Halicarnassus ( grc, Διονύσιος Ἀλεξάνδρου Ἁλικαρνασσεύς,

; – after 7 BC) was a Greek historian and teacher of rhetoric, who flourished during the reign of Emperor Augustus. His literary styl ...

; Islamic Art

Islamic art is a part of Islamic culture and encompasses the visual arts produced since the 7th century CE by people who lived within territories inhabited or ruled by Muslim populations. Referring to characteristic traditions across a wide ra ...

; Sculpture

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable ...

; Decorative Arts

]

The decorative arts are arts or crafts whose object is the design and manufacture of objects that are both beautiful and functional. It includes most of the arts making objects for the interiors of buildings, and interior design, but not usual ...

; Paintings; Prints and Drawings.

The Musée du Louvre contains more than 380,000 objects and displays 35,000 works of art in eight curatorial departments with more than dedicated to the permanent collection. The Louvre exhibits sculptures, objet d'art, objets d'art, paintings, drawings, and archaeological finds.

Location and visit

The Louvre museum is located inside the Louvre Palace, in the center of Paris, adjacent to the

The Louvre museum is located inside the Louvre Palace, in the center of Paris, adjacent to the Tuileries Gardens

The Tuileries Garden (french: Jardin des Tuileries, ) is a public garden located between the Louvre and the Place de la Concorde in the 1st arrondissement of Paris, France. Created by Catherine de' Medici as the garden of the Tuileries Palace in ...

. The two nearest Métro stations are Louvre-Rivoli and Palais Royal-Musée du Louvre, the latter having a direct underground access to the Carrousel du Louvre commercial mall.

Before the Grand Louvre

The Grand Louvre refers to the decade-long project initiated by French President François Mitterrand in 1981 of expanding and remodeling the Louvre – both the building and the museum – by moving the French Finance Ministry, which had been ...

overhaul of the late 1980s and 1990s, the Louvre had several street-level entrances, most of which are now permanently closed. Since 1993, the museum's main entrance has been the underground space under the Louvre Pyramid

The Louvre Pyramid (Pyramide du Louvre) is a large glass and metal structure designed by the Chinese-American architect I. M. Pei. The pyramid is in the main courtyard ( Cour Napoléon) of the Louvre Palace in Paris, surrounded by three small ...

, or ''Hall Napoléon'', which can be accessed from the Pyramid itself, from the underground Carrousel du Louvre, or (for authorized visitors) from the connecting to the nearby rue de Rivoli

Rue de Rivoli (; English: "Rivoli Street") is a street in central Paris, France. It is a commercial street whose shops include leading fashionable brands. It bears the name of Napoleon's early victory against the Austrian army, at the Battle of R ...

. A secondary entrance at the , near the western end of the Denon Wing, was created in 1999 but is not permanently open.

The museum's entrance conditions have varied over time. Initially, artists and foreign visitors had privileged access, a feature that only disappeared in the 1850s. At the time of initial opening in 1793, the French Republican calendar had imposed ten-days "weeks" (french: décades), the first six days of which were reserved for visits by artists and foreigners and the last three for visits by the general public. In the early 1800s, after the seven-day week had been reinstated, the general public had only four hours of museum access per weeks, between 2pm and 4pm on Saturdays and Sundays. In 1824, a new regulation allowed public access only on Sundays and holidays; the other days the museum was open only to artists and foreigners, except for closure on Mondays. That changed in 1855 when the museum became open to the public all days except Mondays. It was free until 1922, when an entrance fee was introduced except on Sundays. Since its post-World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

reopening in 1946, the Louvre has been closed on Tuesdays, and habitually open to the public the rest of the week except for some holidays.

The use of cameras and video recorders is permitted inside, but flash photography is forbidden.

History

Before the Museum

Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various History of Anglo-Saxon England, Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Kingdom of Scotland, ...

still held Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

at the time. Remnants of the Medieval Louvre

The Louvre Castle (french: Château fort du Louvre), also known as the Medieval Louvre (french: Louvre médiéval, links=no), was a castle (french: château fort, links=no) built by King Philip II of France on the right bank of the Seine, to rei ...

are still visible in the crypt. Whether this was the first building on that spot is not known, and it is possible that Philip modified an existing tower.

The origins of the name "Louvre" are somewhat disputed. According to the authoritative '' Grand Larousse encyclopédique'', the name derives from an association with wolf hunting

Wolf hunting is the practice of hunting gray wolves ''(Canis lupus)'' or other species of wolves. Wolves are mainly hunted for sport, for their skins, to protect livestock and, in some rare cases, to protect humans. Wolves have been actively hun ...

den (via Latin: ''lupus'', lower Empire: ''lupara'').Edwards, pp. 193–94 In the 7th century, Burgundofara

Burgundofara (died 643 or 655), also Saint Fara or Fare, was the founder and first Abbess of the Abbey of Faremoutiers.

Life

Her family is knowns as the Faronids, named after her brother Saint Faro. Her name may mean: 'She who moves the Burgundi ...

(also known as Saint Fare), abbess in Meaux, is said to have gifted part of her "Villa called Luvra situated in the region of Paris" to a monastery, even though it is doubtful that this land corresponded exactly to the present site of the Louvre.

The Louvre Palace has been subject to numerous renovations since its construction. In the 14th century, Charles V converted the building from its military role into a residence. In 1546, Francis I started its rebuilding in French Renaissance

The French Renaissance was the cultural and artistic movement in France between the 15th and early 17th centuries. The period is associated with the pan-European Renaissance, a word first used by the French historian Jules Michelet to define th ...

style.Edwards, p. 198 After Louis XIV chose Versailles as his residence in 1682, construction works slowed to a halt. The royal move away from Paris resulted in the Louvre being used as a residence for artists, under Royal patronage. For example, four generations of craftsmen-artists from the Boulle family were granted Royal patronage and resided in the Louvre.

Meanwhile, the collections of the Louvre originated in the acquisitions of paintings and other artworks by the monarchs of the House of France

The term House of France refers to the branch of the Capetian dynasty which provided the Kings of France following the election of Hugh Capet. The House of France consists of a number of branches and their sub-branches. Some of its branches ha ...

. At the Palace of Fontainebleau

Palace of Fontainebleau (; ) or Château de Fontainebleau, located southeast of the center of Paris, in the commune of Fontainebleau, is one of the largest French royal châteaux. The medieval castle and subsequent palace served as a residence ...

, Francis collected art that would later be part of the Louvre's art collections, including Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially res ...

's ''Mona Lisa

The ''Mona Lisa'' ( ; it, Gioconda or ; french: Joconde ) is a Half length portrait, half-length portrait painting by Italian artist Leonardo da Vinci. Considered an archetypal masterpiece of the Italian Renaissance, it has been described ...

''.

The Cabinet du Roi consisted of seven rooms west of the Galerie d'Apollon on the upper floor of the remodeled Petite Galerie. Many of the king's paintings were placed in these rooms in 1673, when it became an art gallery, accessible to certain art lovers as a kind of museum. In 1681, after the court moved to Versailles, 26 of the paintings were transferred there, somewhat diminishing the collection, but it is mentioned in Paris guide books from 1684 on, and was shown to ambassadors from Siam

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

in 1686.

By the mid-18th century there were an increasing number of proposals to create a public gallery in the Louvre. Art critic Étienne La Font de Saint-Yenne

Étienne La Font de Saint-Yenne (born 1688 in Lyon, died 1771 in Paris) was a French art critic

An art critic is a person who is specialized in analyzing, interpreting, and evaluating art. Their written critiques or reviews contribute to art ...

in 1747 published a call for a display of the royal collection. On 14 October 1750, Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached ...

decided on a display of 96 pieces from the royal collection, mounted in the Galerie royale de peinture of the Luxembourg Palace

The Luxembourg Palace (french: Palais du Luxembourg, ) is at 15 Rue de Vaugirard in the 6th arrondissement of Paris. It was originally built (1615–1645) to the designs of the French architect Salomon de Brosse to be the royal residence of th ...

. A hall was opened by Le Normant de Tournehem and the Marquis de Marigny for public viewing of the "king's paintings" (''Tableaux du Roy'') on Wednesdays and Saturdays. The Luxembourg gallery included Andrea del Sarto's ''Charity'' and works by Raphael

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, better known as Raphael (; or ; March 28 or April 6, 1483April 6, 1520), was an Italian painter and architect of the High Renaissance. His work is admired for its clarity of form, ease of composition, and visual a ...

; Titian

Tiziano Vecelli or Vecellio (; 27 August 1576), known in English as Titian ( ), was an Italian (Venetian) painter of the Renaissance, considered the most important member of the 16th-century Venetian school. He was born in Pieve di Cadore, nea ...

; Veronese; Rembrandt; Poussin

Nicolas Poussin (, , ; June 1594 – 19 November 1665) was the leading painter of the classical French Baroque style, although he spent most of his working life in Rome. Most of his works were on religious and mythological subjects painted for ...

or Van Dyck

Sir Anthony van Dyck (, many variant spellings; 22 March 1599 – 9 December 1641) was a Brabantian Flemish Baroque artist who became the leading court painter in England after success in the Southern Netherlands and Italy.

The seventh ...

. It closed in 1780 as a result of the royal gift of the Luxembourg palace to the Count of Provence

The land of Provence has a history quite separate from that of any of the larger nations of Europe. Its independent existence has its origins in the frontier nature of the dukedom in Merovingian Gaul. In this position, influenced and affected by ...

(the future king, Louis XVIII) by the king in 1778. Under Louis XVI

Louis XVI (''Louis-Auguste''; ; 23 August 175421 January 1793) was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. He was referred to as ''Citizen Louis Capet'' during the four months just before he was ...

, the idea of a royal museum in the Louvre came closer to fruition.Carbonell, p. 56 The comte d'Angiviller broadened the collection and in 1776 proposed to convert the Grande Galerie

The Grande Galerie, in the past also known as the Galerie du Bord de l'Eau (Waterside Gallery), is a wing of the Louvre Palace, perhaps more properly referred to as the Aile de la Grande Galerie (Grand Gallery Wing), since it houses the longest ...

of the Louvre – which at that time contained the '' plans-reliefs'' or 3D models of key fortified sites in and around France – into the "French Museum". Many design proposals were offered for the Louvre's renovation into a museum, without a final decision being made on them. Hence the museum remained incomplete until the French Revolution.

Revolutionary opening

The Louvre finally became a public museum during the French Revolution. In May 1791, the National Constituent Assembly declared that the Louvre would be "a place for bringing together monuments of all the sciences and arts". On 10 August 1792, Louis XVI was imprisoned and the royal collection in the Louvre became national property. Because of fear of vandalism or theft, on 19 August, the National Assembly pronounced the museum's preparation as urgent. In October, a committee to "preserve the national memory" began assembling the collection for display.Church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a building for Christian religious activities

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian communal worship

* C ...

property ('' biens nationaux''). To expand and organize the collection, the Republic dedicated 100,000 livres

The (; ; abbreviation: ₶.) was one of numerous currencies used in medieval France, and a unit of account (i.e., a monetary unit used in accounting) used in Early Modern France.

The 1262 monetary reform established the as 20 , or 80.88 gr ...

per year.Nora, p. 278 In 1794, France's revolutionary armies began bringing pieces from Northern Europe, augmented after the Treaty of Tolentino

{{unreferenced, date=June 2018

The Treaty of Tolentino was a peace treaty between Revolutionary France and the Papal States, signed on 19 February 1797 and imposing terms of surrender on the Papal side. The signatories for France were the French Di ...

(1797) by works from the Vatican, such as the ''Laocoön

Laocoön (; grc, , Laokóōn, , gen.: ), is a figure in Greek and Roman mythology and the Epic Cycle. Laocoon was a Trojan priest. He and his two young sons were attacked by giant serpents, sent by the gods. The story of Laocoön has been the su ...

'' and ''Apollo Belvedere

The ''Apollo Belvedere'' (also called the ''Belvedere Apollo, Apollo of the Belvedere'', or ''Pythian Apollo'') is a celebrated marble sculpture from Classical Antiquity.

The ''Apollo'' is now thought to be an original Roman creation of Hadri ...

'', to establish the Louvre as a museum and as a "sign of popular sovereignty".

The early days were hectic. Privileged artists continued to live in residence, and the unlabeled paintings hung "frame to frame from floor to ceiling".Alderson, pp. 24, 25 The structure itself closed in May 1796 due to structural deficiencies. It reopened on 14 July 1801, arranged chronologically and with new lighting and columns. On 15 August 1797, the Galerie d'Apollon

The Galerie d'Apollon is a large and iconic room of the Louvre Palace, on the first (upper) floor of a wing known as the Petite Galerie. Its current setup was first designed in the 1660s. It has been part of the Louvre Museum since the 1790s, was ...

was opened with an exhibition of drawings. Meanwhile, the Louvre's gallery of Antiquity sculpture (''musée des Antiques''), with artefacts brought from Florence and the Vatican, had opened in November 1800 in Anne of Austria

Anne of Austria (french: Anne d'Autriche, italic=no, es, Ana María Mauricia, italic=no; 22 September 1601 – 20 January 1666) was an infanta of Spain who became Queen of France as the wife of King Louis XIII from their marriage in 1615 un ...

's former summer apartment, located on the ground floor just below the Galerie d'Apollon.

Napoleonic era

On 19 November 1802, Napoleon appointedDominique Vivant Denon

Dominique Vivant, Baron Denon (4 January 1747 – 27 April 1825) was a French artist, writer, diplomat, author, and archaeologist. Denon was a diplomat for France under Louis XV and Louis XVI. He was appointed as the first Director of the Louvre ...

, a scholar and polymath who had participated in the Egyptian campaign

The French campaign in Egypt and Syria (1798–1801) was Napoleon Bonaparte's campaign in the Ottoman territories of Egypt and Syria, proclaimed to defend French trade interests, to establish scientific enterprise in the region. It was the pr ...

of 1798–1801, as the museum's first director, in preference to alternative contenders such as antiquarian Ennio Quirino Visconti

Ennio Quirino Visconti (November 1, 1751 – February 7, 1818) was an Italian antiquarian and art historian, papal Prefect of Antiquities, and the leading expert of his day in the field of ancient Roman sculpture. His son, Pietro Ercole Visconti, ...

, painter Jacques-Louis David, sculptor Antonio Canova and architects Léon Dufourny or Pierre Fontaine. On Denon's suggestion in July 1803, the museum itself was renamed ''Musée Napoléon''.

The collection grew through successful military campaigns. Acquisitions were made of Spanish, Austrian, Dutch, and Italian works, either as the result of war looting

Looting is the act of stealing, or the taking of goods by force, typically in the midst of a military, political, or other social crisis, such as war, natural disasters (where law and civil enforcement are temporarily ineffective), or rioting. ...

or formalized by treaties such as the Treaty of Tolentino

{{unreferenced, date=June 2018

The Treaty of Tolentino was a peace treaty between Revolutionary France and the Papal States, signed on 19 February 1797 and imposing terms of surrender on the Papal side. The signatories for France were the French Di ...

. At the end of Napoleon's First Italian Campaign in 1797, the Treaty of Campo Formio

The Treaty of Campo Formio (today Campoformido) was signed on 17 October 1797 (26 Vendémiaire VI) by Napoleon Bonaparte and Count Philipp von Cobenzl as representatives of the French Republic and the Austrian monarchy, respectively. The trea ...

was signed with Count Philipp von Cobenzl

Johann Philipp, Graf von Cobenzl (28 May 1741 – 30 August 1810) was a statesman of the Habsburg monarchy and the Austrian Empire.

Life

Cobenzl was born in Ljubljana, Duchy of Carniola, Carniola, the son of treasurer Count Guidobald von Cobenzl ...

of the Austrian Monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy (german: Habsburgermonarchie, ), also known as the Danubian monarchy (german: Donaumonarchie, ), or Habsburg Empire (german: Habsburgerreich, ), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities ...

. This treaty marked the completion of Napoleon's conquest of Italy and the end of the first phase of the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted France against Britain, Austria, Prussia ...

. It compelled Italian cities to contribute pieces of art and heritage to Napoleon's "parades of spoils" through Paris before being put into the Louvre Museum.Plant, p. 36 The Horses of Saint Mark

The Horses of Saint Mark ( it, Cavalli di San Marco), also known as the Triumphal Quadriga or Horses of the Hippodrome of Constantinople, is a set of bronze statues of four horses, originally part of a monument depicting a quadriga (a four-hor ...

, which had adorned the basilica of San Marco in Venice after the sack of Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya ( Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

in 1204, were brought to Paris where they were placed atop Napoleon's Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel

The Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel () ( en, Triumphal Arch of the Carousel) is a triumphal arch in Paris, located in the Place du Carrousel. It is an example of Neoclassical architecture in the Corinthian order. It was built between 1806 and 1808 ...

in 1797. Under the Treaty of Tolentino

{{unreferenced, date=June 2018

The Treaty of Tolentino was a peace treaty between Revolutionary France and the Papal States, signed on 19 February 1797 and imposing terms of surrender on the Papal side. The signatories for France were the French Di ...

, the two statues of the Nile and Tiber were taken to Paris from the Vatican in 1797, and were both kept in the Louvre until 1815. (The Nile was later returned to Rome, whereas the Tiber has remained in the Louvre to this day.) The despoilment of Italian churches and palaces outraged the Italians and their artistic and cultural sensibilities.

After the French defeat at Waterloo, the looted works' former owners sought their return. The Louvre's administrator Denon was loath to comply in absence of a treaty of restitution. In response, foreign states sent emissaries to London to seek help, and many pieces were returned, though far from all.Alderson, p. 25 In 1815 Louis XVIII

Louis XVIII (Louis Stanislas Xavier; 17 November 1755 – 16 September 1824), known as the Desired (), was King of France from 1814 to 1824, except for a brief interruption during the Hundred Days in 1815. He spent twenty-three years in ...

finally concluded agreements with the Austrian

Austrian may refer to:

* Austrians, someone from Austria or of Austrian descent

** Someone who is considered an Austrian citizen, see Austrian nationality law

* Austrian German dialect

* Something associated with the country Austria, for example: ...

government for the keeping of works such as Veronese's ''Wedding at Cana

The transformation of water into wine at the wedding at Cana (also called the marriage at Cana, wedding feast at Cana or marriage feast at Cana) is the first miracle attributed to Jesus in the Gospel of John.

In the Gospel account, Jesus Chris ...

'' which was exchanged for a large Le Brun or the repurchase of the Albani collection.

From 1815 to 1852

For most of the 19th century, from

For most of the 19th century, from Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's time to the Second Empire Second Empire may refer to:

* Second British Empire, used by some historians to describe the British Empire after 1783

* Second Bulgarian Empire (1185–1396)

* Second French Empire (1852–1870)

** Second Empire architecture, an architectural styl ...

, the Louvre and other national museums were managed under the monarch's civil list and thus depended much on the ruler's personal involvement. Whereas the most iconic collection remained that of paintings in the Grande Galerie

The Grande Galerie, in the past also known as the Galerie du Bord de l'Eau (Waterside Gallery), is a wing of the Louvre Palace, perhaps more properly referred to as the Aile de la Grande Galerie (Grand Gallery Wing), since it houses the longest ...

, a number of other initiatives mushroomed in the vast building, named as if they were separate museums even though they were generally managed under the same administrative umbrella. Correspondingly, the museum complex was often referred to in the plural ("") rather than singular.

During the Bourbon Restoration (1814–1830), Louis XVIII

Louis XVIII (Louis Stanislas Xavier; 17 November 1755 – 16 September 1824), known as the Desired (), was King of France from 1814 to 1824, except for a brief interruption during the Hundred Days in 1815. He spent twenty-three years in ...

and Charles X

Charles X (born Charles Philippe, Count of Artois; 9 October 1757 – 6 November 1836) was King of France from 16 September 1824 until 2 August 1830. An uncle of the uncrowned Louis XVII and younger brother to reigning kings Louis XVI and Lou ...

added to the collections. The Greek and Roman sculpture gallery on the ground floor of the southwestern side of the Cour Carrée

The Cour Carrée (Square Court) is one of the main courtyards of the Louvre Palace in Paris. The wings surrounding it were built gradually, as the walls of the medieval Louvre were progressively demolished in favour of a Renaissance palace.

Cons ...

was completed on designs by Percier and Fontaine

Percier and Fontaine was a noted partnership between French architects Charles Percier and Pierre François Léonard Fontaine.

History

Together, Percier and Fontaine were inventors and major proponents of the rich and grand, consciously archaeol ...

. In 1819 an exhibition of manufactured products was opened in the first floor of the Cour Carrée's southern wing and would stay there until the mid-1820s. Charles X in 1826 created the and in 1827 included it in his broader , a new section of the museum complex located in a suite of lavishly decorated rooms on the first floor of the South Wing of the Cour Carrée

The Cour Carrée (Square Court) is one of the main courtyards of the Louvre Palace in Paris. The wings surrounding it were built gradually, as the walls of the medieval Louvre were progressively demolished in favour of a Renaissance palace.

Cons ...

. The Egyptian collection, initially curated by Jean-François Champollion, formed the basis for what is now the Louvre's Department of Egyptian Antiquities. It was formed from the purchased collections of Edmé-Antoine Durand

Edmé-Antoine Durand (1768-1835) was a French diplomat and art collector.

Life

The son of a rich businessman, Durand acquired a wide variety of objects, both locally on his travels (especially in central Italy) and also by buying items from existi ...

, Henry Salt and the second collection of Bernardino Drovetti

Bernardino Michele Maria Drovetti (January 7, 1776 – March 5, 1852) was an Italian antiquities collector, diplomat, and politician. He is best remembered for having acquired the Turin Royal Canon and for his questionable behavior in colle ...

(the first one having been purchased by Victor Emmanuel I of Sardinia

Victor Emmanuel I (Vittorio Emanuele; 24 July 1759 – 10 January 1824) was the Duke of Savoy and King of Sardinia (1802–1821).

Biography

Victor Emmanuel was the second son of King Victor Amadeus III of Sardinia and Maria Antonia Ferdinand ...

to form the core of the present Museo Egizio

The Museo Egizio ( Italian for Egyptian Museum) is an archaeological museum in Turin, Piedmont, Italy, specializing in Egyptian archaeology and anthropology. It houses one of the largest collections of Egyptian antiquities, with more than 30,0 ...

in Turin

Turin ( , Piedmontese: ; it, Torino ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in Northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital from 1861 to 1865. The ...

). The Restoration period also saw the opening in 1824 of the , a section of largely French sculptures on the ground floor of the Northwestern side of the Cour Carrée

The Cour Carrée (Square Court) is one of the main courtyards of the Louvre Palace in Paris. The wings surrounding it were built gradually, as the walls of the medieval Louvre were progressively demolished in favour of a Renaissance palace.

Cons ...

, many of whose artefacts came from the Palace of Versailles and from Alexandre Lenoir's Musée des Monuments Français following its closure in 1816. Meanwhile, the French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

created an exhibition of ship models in the Louvre in December 1827, initially named in honor of Dauphin Louis Antoine, building on an 18th-century initiative of Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau

Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau (20 July 1700, Paris13 August 1782, Paris), was a French physician, naval engineer and botanist.

Biography

Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau was born in Paris in 1700, the son of Alexandre Duhamel, lord of Denai ...

. This collection, renamed in 1833 and later to develop into the Musée national de la Marine

The Musée national de la Marine (National Navy Museum) is a maritime museum located in the Palais de Chaillot, Trocadéro, in the 16th arrondissement of Paris. It has annexes at Brest, Port-Louis, Rochefort ( Musée National de la Marine de ...

, was initially located on the first floor of the Cour Carrée

The Cour Carrée (Square Court) is one of the main courtyards of the Louvre Palace in Paris. The wings surrounding it were built gradually, as the walls of the medieval Louvre were progressively demolished in favour of a Renaissance palace.

Cons ...

's North Wing, and in 1838 moved up one level to the 2nd-floor attic, where it remained for more than a century.

July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution (french: révolution de Juillet), Second French Revolution, or ("Three Glorious ays), was a second French Revolution after the first in 1789. It led to the overthrow of King ...

, King Louis Philippe focused his interest on the repurposing of the Palace of Versailles into a Museum of French History conceived as a project of national reconciliation, and the Louvre was kept in comparative neglect. Louis-Philippe did, however, sponsor the creation of the to host the monumental Assyrian sculpture

Assyrian sculpture is the sculpture of the ancient Assyrian states, especially the Neo-Assyrian Empire of 911 to 612 BC, which was centered around the city of Assur in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) which at its height, ruled over all of Mesopo ...

works brought to Paris by Paul-Émile Botta, in the ground-floor gallery north of the eastern entrance of the Cour Carrée

The Cour Carrée (Square Court) is one of the main courtyards of the Louvre Palace in Paris. The wings surrounding it were built gradually, as the walls of the medieval Louvre were progressively demolished in favour of a Renaissance palace.

Cons ...

. The Assyrian Museum opened on 1 May 1847. Separately, Louis-Philippe had his Spanish gallery

The Spanish gallery, also called Spanish museum was a gallery of Spanish painting created by French King Louis Philippe I in 1838, shown in the Louvre, then dismantled in 1853.

Historical context

Until the French Revolution, Spanish art was seldo ...

displayed in the Louvre from 7 January 1838, in five rooms on the first floor of the Cour Carrée's East (Colonnade

In classical architecture, a colonnade is a long sequence of columns joined by their entablature, often free-standing, or part of a building. Paired or multiple pairs of columns are normally employed in a colonnade which can be straight or cur ...

) Wing, but the collection remained his personal property. As a consequence, the works were removed after Louis-Philippe was deposed in 1848, and were eventually auctioned away in 1853.

The short-lived Second Republic had more ambitions for the Louvre. It initiated repair work, the completion of the Galerie d'Apollon

The Galerie d'Apollon is a large and iconic room of the Louvre Palace, on the first (upper) floor of a wing known as the Petite Galerie. Its current setup was first designed in the 1660s. It has been part of the Louvre Museum since the 1790s, was ...

and of the , and the overhaul of the (former site of the iconic yearly Salon) and of the Grande Galerie

The Grande Galerie, in the past also known as the Galerie du Bord de l'Eau (Waterside Gallery), is a wing of the Louvre Palace, perhaps more properly referred to as the Aile de la Grande Galerie (Grand Gallery Wing), since it houses the longest ...

. In 1848, the Naval Museum in the Cour Carrée's attic was brought under the common Louvre Museum management, a change which was again reversed in 1920. In 1850 under the leadership of curator Adrien de Longpérier, the musée mexicain

The ''musée mexicain'', later ''musée américain'' (Mexican Museum / American Museum), was a section of the Louvre that was dedicated to pre-Columbian art, with an initial emphasis on Mexican archaeology. It opened in 1850, and closed in 1887 w ...

opened within the Louvre as the first European museum dedicated to pre-Columbian art

Pre-Columbian art refers to the visual arts of indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, North, Central, and South Americas from at least 13,000 BCE to the European conquests starting in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. The Pre-Columbian era c ...

.

Second Empire

The rule ofNapoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

was transformational for the Louvre, both the building and the museum. In 1852, he created the Musée des Souverains

The ''Musée des Souverains'' (''Museum of Sovereigns'') was a history-themed museum of objects associated with former French monarchs. It was created by the future Napoleon III as a separate section within the Louvre Palace, with the aim to glor ...

in the Colonnade Wing, an ideological project aimed at buttressing his personal legitimacy. In 1861, he bought 11,835 artworks including 641 paintings, Greek gold and other antiquities of the Campana collection. For its display, he created another new section within the Louvre named , occupying a number of rooms in various parts of the building. Between 1852 and 1870, the museum added 20,000 new artefacts to its collections.

The main change of that period was to the building itself. In the 1850s architects Louis Visconti

Louis Tullius Joachim Visconti (Rome February 11, 1791 – December 29, 1853) was an Italian-born French architect and designer.

Life

Son of the Italian archaeologist and art historian Ennio Quirino Visconti, Visconti designed many Par ...

and Hector Lefuel

Hector-Martin Lefuel (14 November 1810 – 31 December 1880) was a French architect, best known for his work on the Palais du Louvre, including Napoleon III's Louvre expansion and the reconstruction of the Pavillon de Flore.

Biography

He wa ...

created massive new spaces around what is now called the Cour Napoléon, some of which (in the South Wing, now Aile Denon) went to the museum. In the 1860s, Lefuel also led the creation of the with a new closer to Napoleon III's residence in the Tuileries Palace

The Tuileries Palace (french: Palais des Tuileries, ) was a royal and imperial palace in Paris which stood on the right bank of the River Seine, directly in front of the Louvre. It was the usual Parisian residence of most French monarchs, f ...

, with the effect of shortening the Grande Galerie

The Grande Galerie, in the past also known as the Galerie du Bord de l'Eau (Waterside Gallery), is a wing of the Louvre Palace, perhaps more properly referred to as the Aile de la Grande Galerie (Grand Gallery Wing), since it houses the longest ...

by about a third of its previous length. A smaller but significant Second Empire project was the decoration of the below the Salon carré

The Salon Carré is an iconic room of the Louvre Palace, created in its current dimensions during a reconstruction of that part of the palace following a fire in February 1661. It gave its name to the longstanding tradition of exhibitions of cont ...

.

From 1870 to 1981

The Louvre narrowly escaped serious damage during the suppression of the

The Louvre narrowly escaped serious damage during the suppression of the Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (french: Commune de Paris, ) was a revolutionary government that seized power in Paris, the capital of France, from 18 March to 28 May 1871.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defended ...

. On 23 May 1871, as the French Army advanced into Paris, a force of ''Communards'' led by set fire to the adjoining Tuileries Palace

The Tuileries Palace (french: Palais des Tuileries, ) was a royal and imperial palace in Paris which stood on the right bank of the River Seine, directly in front of the Louvre. It was the usual Parisian residence of most French monarchs, f ...

. The fire burned for forty-eight hours, entirely destroying the interior of the Tuileries and spreading to the north west wing of the museum next to it. The emperor's Louvre library (''Bibliothèque du Louvre'') and some of the adjoining halls, in what is now the Richelieu Wing, were separately destroyed. But the museum was saved by the efforts of Paris firemen and museum employees led by curator Henry Barbet de Jouy

Joseph-Henry Barbet de Jouy (16 July 1812, Canteleu – 26 May 1896, Paris) was a French archaeologist, art historian, and curator.

Biography

His father was the industrialist, . From 1832 to 1840, he studied at both the Faculty of Law of Paris ...

.

Following the end of the monarchy, several spaces in the Louvre's South Wing went to the museum. The Salle du Manège was transferred to the museum in 1879, and in 1928 became its main entrance lobby. The large Salle des Etats that had been created by Lefuel between the Grande Galerie

The Grande Galerie, in the past also known as the Galerie du Bord de l'Eau (Waterside Gallery), is a wing of the Louvre Palace, perhaps more properly referred to as the Aile de la Grande Galerie (Grand Gallery Wing), since it houses the longest ...

and Pavillon Denon was redecorated in 1886 by , Lefuel's successor as architect of the Louvre, and opened as a spacious exhibition room. Edomond Guillaume also decorated the first-floor room at the northwest corner of the Cour Carrée

The Cour Carrée (Square Court) is one of the main courtyards of the Louvre Palace in Paris. The wings surrounding it were built gradually, as the walls of the medieval Louvre were progressively demolished in favour of a Renaissance palace.

Cons ...

, on the ceiling of which he placed in 1890 a monumental painting by Carolus-Duran, ''The Triumph of Marie de' Medici'' originally created in 1879 for the Luxembourg Palace

The Luxembourg Palace (french: Palais du Luxembourg, ) is at 15 Rue de Vaugirard in the 6th arrondissement of Paris. It was originally built (1615–1645) to the designs of the French architect Salomon de Brosse to be the royal residence of th ...

.

Meanwhile, during the Third Republic (1870–1940) the Louvre acquired new artefacts mainly via donations, gifts, and sharing arrangements on excavations abroad. The 583-item , donated in 1869 by

Meanwhile, during the Third Republic (1870–1940) the Louvre acquired new artefacts mainly via donations, gifts, and sharing arrangements on excavations abroad. The 583-item , donated in 1869 by Louis La Caze

Louis La Caze (6 May 1798 – 28 September 1869) was a successful French physician and collector of paintings whose bequest of 583 paintings to the Musée du Louvre was one of the largest the museum has ever received. Among the paintings, the most ...

, included works by Chardin; Fragonard, Rembrandt and Watteau

Jean-Antoine Watteau (, , ; baptised October 10, 1684died July 18, 1721) Alsavailablevia Oxford Art Online (subscription needed). was a French painter and draughtsman whose brief career spurred the revival of interest in colour and movement, as ...

. In 1883, the ''Winged Victory of Samothrace

The ''Winged Victory of Samothrace'', or the ''Nike of Samothrace'', is a votive monument originally found on the island of Samothrace, north of the Aegean Sea. It is a masterpiece of Greek sculpture from the Hellenistic era, dating from the be ...

'', which had been found in the Aegean Sea in 1863, was prominently displayed as the focal point of the Escalier Daru. Major artifacts excavated at Susa in Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, including the massive ''Apadana capital'' and glazed brick decoration from the Palace of Darius there, accrued to the Oriental (Near Eastern) Antiquities Department in the 1880s. The Société des amis du Louvre was established in 1897 and donated prominent works, such as the '' Pietà of Villeneuve-lès-Avignon''. The expansion of the museum and its collections slowed after World War I, however, despite some prominent acquisitions such as Georges de La Tour

Georges de La Tour (13 March 1593 – 30 January 1652) was a French Baroque painter, who spent most of his working life in the Duchy of Lorraine, which was temporarily absorbed into France between 1641 and 1648. He painted mostly religious chia ...

's ''Saint Thomas'' and Baron Edmond de Rothschild

Baron Abraham Edmond Benjamin James de Rothschild (Hebrew: הברון אברהם אדמונד בנימין ג'יימס רוטשילד - ''HaBaron Avraham Edmond Binyamin Ya'akov Rotshield''; 19 August 1845 – 2 November 1934) was a French memb ...

's 1935 donation of 4,000 prints, 3,000 drawings, and 500 illustrated books.

From the late 19th century, the Louvre gradually veered away from its mid-century ambition of universality to become a more focused museum of French, Western and Near Eastern art, covering a space ranging from Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

to the Atlantic. The collections of the Louvre's musée mexicain

The ''musée mexicain'', later ''musée américain'' (Mexican Museum / American Museum), was a section of the Louvre that was dedicated to pre-Columbian art, with an initial emphasis on Mexican archaeology. It opened in 1850, and closed in 1887 w ...

were transferred to the Musée d'Ethnographie du Trocadéro in 1887. As the was increasingly constrained to display its core naval-themed collections in the limited space it had in the second-floor attic of the northern half of the Cour Carrée

The Cour Carrée (Square Court) is one of the main courtyards of the Louvre Palace in Paris. The wings surrounding it were built gradually, as the walls of the medieval Louvre were progressively demolished in favour of a Renaissance palace.

Cons ...

, many of its significant holdings of non-Western artefacts were transferred in 1905 to the Trocadéro ethnography museum, the National Antiquities Museum in Saint-Germain-en-Laye

Saint-Germain-en-Laye () is a commune in the Yvelines department in the Île-de-France in north-central France. It is located in the western suburbs of Paris, from the centre of Paris.

Inhabitants are called ''Saint-Germanois'' or ''Saint-Ge ...

, and the Chinese Museum in the Palace of Fontainebleau

Palace of Fontainebleau (; ) or Château de Fontainebleau, located southeast of the center of Paris, in the commune of Fontainebleau, is one of the largest French royal châteaux. The medieval castle and subsequent palace served as a residence ...

. The Musée de Marine itself was relocated to the Palais de Chaillot

The Palais de Chaillot () is a building at the top of the in the Trocadéro area in the 16th ''arrondissement'' of Paris, France.

For the Exposition Internationale of 1937, the old 1878 Palais du Trocadéro was partly demolished and partly ...

in 1943. The Louvre's extensive collections of Asian art

The history of Asian art includes a vast range of arts from various cultures, regions, and religions across the continent of Asia. The major regions of Asia include Central, East, South, Southeast, and West Asia.

Central Asian art primarily c ...

were moved to the Guimet Museum

The Guimet Museum (full name in french: Musée national des arts asiatiques-Guimet; MNAAG; ) is an art museum located at 6, place d'Iéna in the 16th arrondissement of Paris, France. Literally translated into English, its full name is the Nationa ...

in 1945. Nevertheless, the Louvre's first gallery of Islamic art

Islamic art is a part of Islamic culture and encompasses the visual arts produced since the 7th century CE by people who lived within territories inhabited or ruled by Muslim populations. Referring to characteristic traditions across a wide ra ...

opened in 1922.

In the late 1920s, Louvre Director

In the late 1920s, Louvre Director Henri Verne

Henri Jean François Joseph Verne (21 September 1880, Cannes – 11 February 1949, Paris) was a French museum director and curator.

Biography

He held degrees in literature and law. In 1906, he became a document editor at the Ministry of Trade ...

devised a master plan for the rationalization of the museum's exhibitions, which was partly implemented in the following decade. In 1932–1934, Louvre architects and Albert Ferran redesigned the Escalier Daru to its current appearance. The in the South Wing was covered by a glass roof in 1934. Decorative arts exhibits were expanded in the first floor of the North Wing of the Cour Carrée

The Cour Carrée (Square Court) is one of the main courtyards of the Louvre Palace in Paris. The wings surrounding it were built gradually, as the walls of the medieval Louvre were progressively demolished in favour of a Renaissance palace.

Cons ...

, including some of France's first period room A period room is a display that represents the interior design and decorative art of a particular historical social setting usually in a museum. Though it may incorporate elements of an individual real room that once existed somewhere, it is usuall ...

displays. In the late 1930s, The La Caze donation was moved to a remodeled above the , with reduced height to create more rooms on the second floor and a sober interior design by Albert Ferran.

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, the Louvre conducted an elaborate plan of evacuation of its art collection. When Germany occupied the Sudetenland, many important artworks such as the ''Mona Lisa

The ''Mona Lisa'' ( ; it, Gioconda or ; french: Joconde ) is a Half length portrait, half-length portrait painting by Italian artist Leonardo da Vinci. Considered an archetypal masterpiece of the Italian Renaissance, it has been described ...

'' were temporarily moved to the Château de Chambord

The Château de Chambord () in Chambord, Centre-Val de Loire, France, is one of the most recognisable châteaux in the world because of its very distinctive French Renaissance architecture which blends traditional French medieval forms with cla ...

. When war was formally declared a year later, most of the museum's paintings were sent there as well. Select sculptures such as ''Winged Victory of Samothrace

The ''Winged Victory of Samothrace'', or the ''Nike of Samothrace'', is a votive monument originally found on the island of Samothrace, north of the Aegean Sea. It is a masterpiece of Greek sculpture from the Hellenistic era, dating from the be ...

'' and the ''Venus de Milo

The ''Venus de Milo'' (; el, Αφροδίτη της Μήλου, Afrodíti tis Mílou) is an ancient Greek sculpture that was created during the Hellenistic period, sometime between 150 and 125 BC. It is one of the most famous works of ancient ...

'' were sent to the Château de Valençay

Château de Valençay is a château in the commune of Valençay, in the Indre department of France. It was a residence of the d'Estampes and Talleyrand-Périgord families. Although it is part of the province of Berry, its architecture invit ...

. On 27 August 1939, after two days of packing, truck convoys began to leave Paris. By 28 December, the museum was cleared of most works, except those that were too heavy and "unimportant paintings hat

A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mecha ...

were left in the basement". In early 1945, after the liberation of France, art began returning to the Louvre.

New arrangements after the war revealed the further evolution of taste away from the lavish decorative practices of the late 19th century. In 1947, Edmond Guillaume's ceiling ornaments were removed from the , where the ''Mona Lisa

The ''Mona Lisa'' ( ; it, Gioconda or ; french: Joconde ) is a Half length portrait, half-length portrait painting by Italian artist Leonardo da Vinci. Considered an archetypal masterpiece of the Italian Renaissance, it has been described ...

'' was first displayed in 1966. Around 1950, Louvre architect streamlined the interior decoration of the Grande Galerie

The Grande Galerie, in the past also known as the Galerie du Bord de l'Eau (Waterside Gallery), is a wing of the Louvre Palace, perhaps more properly referred to as the Aile de la Grande Galerie (Grand Gallery Wing), since it houses the longest ...

. In 1953, a new ceiling by Georges Braque was inaugurated in the , next to the . In the late 1960s, seats designed by Pierre Paulin were installed in the Grande Galerie

The Grande Galerie, in the past also known as the Galerie du Bord de l'Eau (Waterside Gallery), is a wing of the Louvre Palace, perhaps more properly referred to as the Aile de la Grande Galerie (Grand Gallery Wing), since it houses the longest ...

. In 1972, the 's museography was remade with lighting from a hung tubular case, designed by Louvre architect with assistance from designers , Joseph-André Motte

Joseph-André Motte (6 January 1925 – 1 June 2013) was a French furniture designer and interior designer and ranks among the most influential and innovative figures of post-war French design.

Joseph-André Motte was born in Saint-Bonnet-en-C ...

and Paulin.

In 1961, the Finance Ministry accepted to leave the Pavillon de Flore

The Pavillon de Flore, part of the Palais du Louvre in Paris, France, stands at the southwest end of the Louvre, near the Pont Royal. It was originally constructed in 1607–1610, during the reign of Henry IV, as the corner pavilion between ...

at the southwestern end of the Louvre building, as Verne had recommended in his 1920s plan. New exhibition spaces of sculptures (ground floor) and paintings (first floor) opened there later in the 1960s, on a design by government architect Olivier Lahalle.

Grand Louvre

In 1981, French President François Mitterrand proposed, as one of his Grands Projets, the Grand Louvre plan to relocate the Finance Ministry, until then housed in the North Wing of the Louvre, and thus devote almost the entire Louvre building (except its northwestern tip, which houses the separate Musée des Arts Décoratifs) to the museum which would be correspondingly restructured. In 1984I. M. Pei

Ieoh Ming Pei

– website of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners ( ; ; April 26, 1917 – May 16, 2019) was ...

, the architect personally selected by Mitterrand, proposed a master plan including an underground entrance space accessed through a glass pyramid in the Louvre's central ''Cour Napoléon''.

The open spaces surrounding the pyramid were inaugurated on 15 October 1988, and its underground lobby was opened on 30 March 1989. New galleries of early modern French paintings on the 2nd floor of the – website of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners ( ; ; April 26, 1917 – May 16, 2019) was ...

Cour Carrée

The Cour Carrée (Square Court) is one of the main courtyards of the Louvre Palace in Paris. The wings surrounding it were built gradually, as the walls of the medieval Louvre were progressively demolished in favour of a Renaissance palace.

Cons ...

, for which the planning had started before the ''Grand Louvre'', also opened in 1989. Further rooms in the same sequence, designed by Italo Rota, opened on 15 December 1992.

On 18 November 1993, Mitterrand inaugurated the next major phase of the Grand Louvre plan: the renovated North (Richelieu) Wing in the former Finance Ministry site, the museum's largest single expansion in its entire history, designed by Pei, his French associate Michel Macary, and Jean-Michel Wilmotte

Jean-Michel Wilmotte (born 1948 in Soissons) is a French architect.

Biography

Jean-Michel Wilmotte studied interior design at the Camondo school of interior design in Paris. Just two years after graduating, he founded his own agency in Paris in ...

. Further underground spaces known as the Carrousel du Louvre, centered on the Inverted Pyramid and designed by Pei and Macary, had opened in October 1993. Other refurbished galleries, of Italian sculptures and Egyptian antiquities, opened in 1994. The third and last main phase of the plan unfolded mainly in 1997, with new renovated rooms in the Sully and Denon wings. A new entrance at the ''porte des Lions'' opened in 1998, leading on the first floor to new rooms of Spanish paintings.

As of 2002, the Louvre's visitor count had doubled from its pre-Grand-Louvre levels.

I. M. Pei

Ieoh Ming Pei

– website of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners ( ; ; April 26, 1917 – May 16, 2019) was ...

's – website of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners ( ; ; April 26, 1917 – May 16, 2019) was ...

pyramid

A pyramid (from el, πυραμίς ') is a structure whose outer surfaces are triangular and converge to a single step at the top, making the shape roughly a pyramid in the geometric sense. The base of a pyramid can be trilateral, quadrilat ...

in its center, at dusk.

21st century

President Jacques Chirac, who had succeeded Mitterrand in 1995, insisted on the return of non-Western art to the Louvre, upon a recommendation from his friend the art collector and dealer . On his initiative, a selection of highlights from the collections of what would become the Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac was installed on the ground floor of the and opened in 2000, six years ahead of the Musée du Quai Branly itself.