Lingchi (cropped).jpg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Lingchi'' (

''Lingchi'' (

''Lingchi'' existed under the earliest emperors, although similar but less cruel tortures were often prescribed instead. Under the reign of

''Lingchi'' existed under the earliest emperors, although similar but less cruel tortures were often prescribed instead. Under the reign of

The first Western photographs of ''lingchi'' were taken in 1890 by William Arthur Curtis of Kentucky in Canton.

French soldiers stationed in

The first Western photographs of ''lingchi'' were taken in 1890 by William Arthur Curtis of Kentucky in Canton.

French soldiers stationed in

''Lingchi'' (

''Lingchi'' (IPA

IPA commonly refers to:

* India pale ale, a style of beer

* International Phonetic Alphabet, a system of phonetic notation

* Isopropyl alcohol, a chemical compound

IPA may also refer to:

Organizations International

* Insolvency Practitioners ...

: lǐŋ.ʈʂʰɨ̌, ), usually translated "slow slicing" or "death by a thousand cuts", was a form of torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons such as punishment, extracting a confession, interrogational torture, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties. definitions of tortur ...

and execution

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

used in China from around the 10th century until the early 20th century. It was also used in Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

and Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

. In this form of execution, a knife was used to methodically remove portions of the body over an extended period of time, eventually resulting in death. ''Lingchi'' was reserved for crimes viewed as especially heinous, such as treason. Even after the practice was outlawed, the concept itself has still appeared across many types of media.

Etymology

The term ''lingchi'' first appeared in a line in Chapter 28 of the third-century BCE philosophical text '' Xunzi'' that describes the difficulty of travel on mountainous terrain. Later on, it was used to describe the prolonging of a person's agony when the person is being killed. An alternative theory suggests that the term originated from the Khitan language, as the penal meaning of the word emerged during the KhitanLiao dynasty

The Liao dynasty (; Khitan language, Khitan: ''Mos Jælud''; ), also known as the Khitan Empire (Khitan: ''Mos diau-d kitai huldʒi gur''), officially the Great Liao (), was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China that exi ...

.

Description

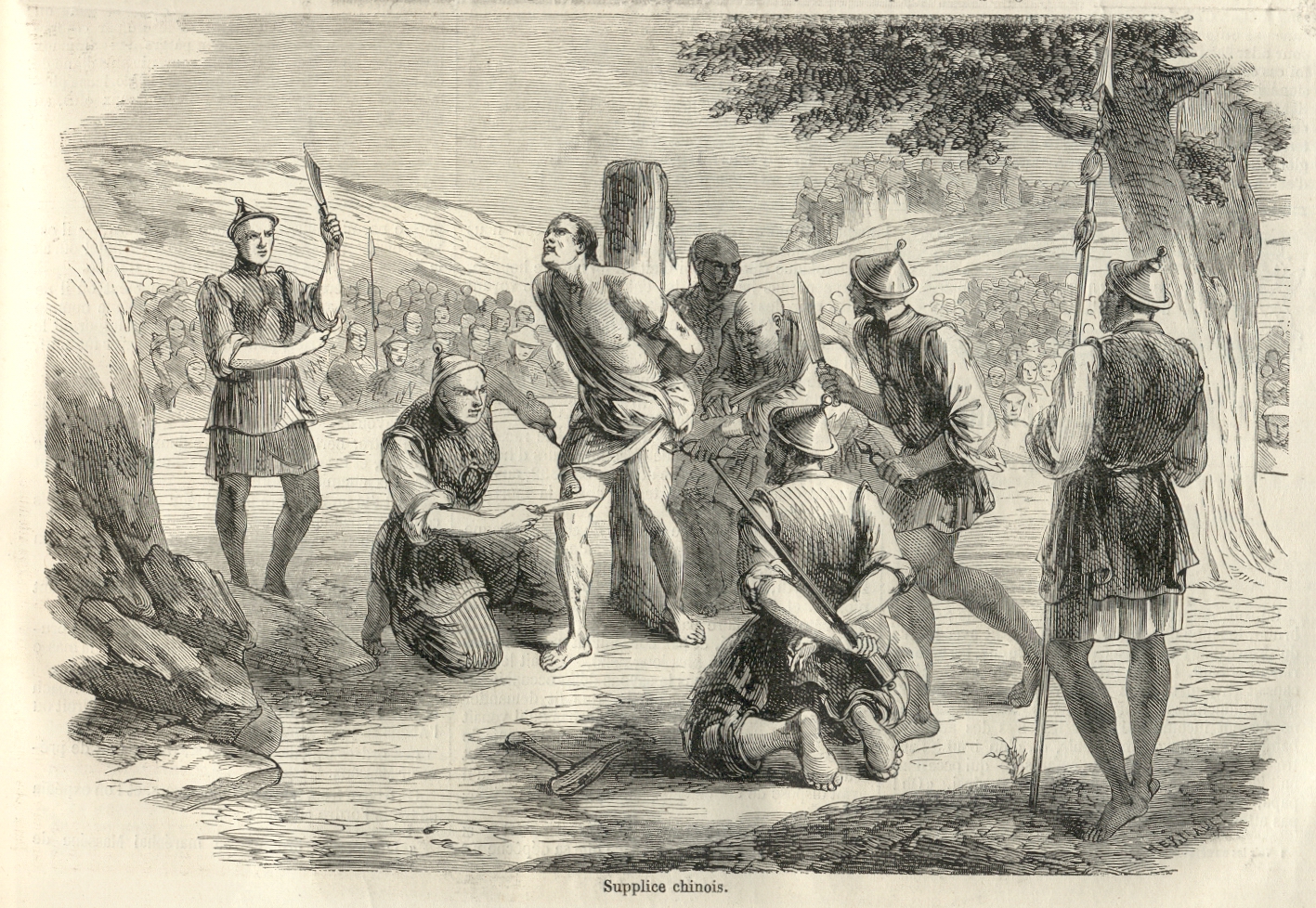

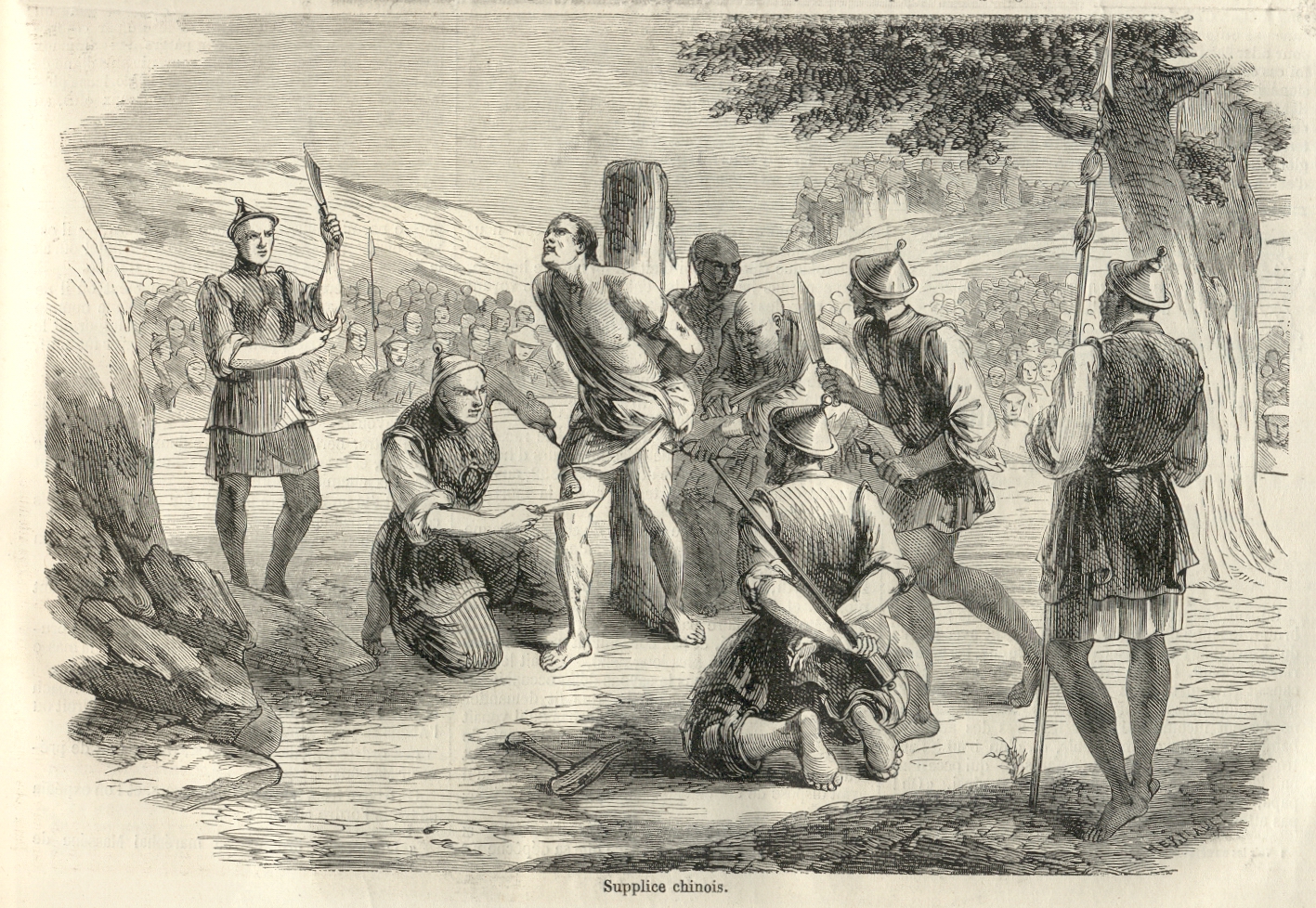

The process involved tying the condemned prisoner to a wooden frame, usually in a public place. The flesh was then cut from the body in multiple slices in a process that was not specified in detail in Chinese law, and therefore most likely varied. The punishment worked on three levels: as a form of public humiliation, as a slow and lingering death, and as a punishment after death. According to theConfucian

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China. Variously described as tradition, a philosophy, a religion, a humanistic or rationalistic religion, a way of governing, or ...

principle of filial piety

In Confucianism, Chinese Buddhism, and Daoist ethics, filial piety (, ''xiào'') (Latin: pietas) is a virtue of respect for one's parents, elders, and ancestors. The Confucian '' Classic of Filial Piety'', thought to be written around the lat ...

, to alter one's body or to cut the body are considered unfilial practices. ''Lingchi'' therefore contravenes the demands of filial piety. In addition, to be cut to pieces meant that the body of the victim would not be "whole" in spiritual life after death. This method of execution became a fixture in the image of China among some Westerners.

''Lingchi'' could be used for the torture and execution of a person, or applied as an act of humiliation after death. It was meted out for major offences such as high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

, mass murder, patricide

Patricide is (i) the act of killing one's own father, or (ii) a person who kills their own father or stepfather. The word ''patricide'' derives from the Greek word ''pater'' (father) and the Latin suffix ''-cida'' (cutter or killer). Patricid ...

/matricide

Matricide is the act of killing one's own mother.

Known or suspected matricides

* Amastrine, Amastris, queen of Heraclea, was drowned by her two sons in 284 BC.

* Cleopatra III of Egypt was assassinated in 101 BC by order of her son, Pto ...

, or the murder of one's master or employer (English: petty treason

Petty treason or petit treason was an offence under the common law of England in which a person killed or otherwise violated the authority of a social superior, other than the king. In England and Wales, petty treason ceased to be a distinct offen ...

). Emperors used it to threaten people and sometimes ordered it for minor offences. There were forced convictions and wrongful executions. Some emperors meted out this punishment to the family members of their enemies.

While it is difficult to obtain accurate details of how the executions took place, they generally consisted of cuts to the arms, legs, and chest leading to amputation of limbs, followed by decapitation or a stab to the heart. If the crime was less serious or the executioner merciful, the first cut would be to the throat causing death; subsequent cuts served solely to dismember the corpse.

Art historian James Elkins argues that extant photos of the execution clearly show that the "death by division" (as it was termed by German criminologist Robert Heindl

Robert Heindl (24 July 1883 - 25 September 1958) was a German criminologist and lawyer, most noted for his advocacy of fingerprinting

A fingerprint is an impression left by the friction ridges of a human finger. The recovery of partial fing ...

) involved some degree of dismemberment

Dismemberment is the act of cutting, ripping, tearing, pulling, wrenching or otherwise disconnecting the limbs from a living or dead being. It has been practiced upon human beings as a form of capital punishment, especially in connection with ...

while the subject was living. Elkins also argues that, contrary to the apocryphal version of "death by a thousand cuts", the actual process could not have lasted long. The condemned individual is not likely to have remained conscious and aware (if even alive) after one or two severe wounds, so the entire process could not have included more than a "few dozen" wounds.

In the Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fift ...

, 100 cuts were inflicted but by the Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last orthodox dynasty of China ruled by the Han peo ...

there were records of 3,000 incisions. It is described as a fast process lasting no longer than 15 to 20 minutes. The ''coup de grâce

A coup de grâce (; 'blow of mercy') is a death blow to end the suffering of a severely wounded person or animal. It may be a mercy killing of mortally wounded civilians or soldiers, friends or enemies, with or without the sufferer's consent. ...

'' was all the more certain when the family could afford a bribe to have a stab to the heart inflicted first. Some emperors ordered three days of cutting while others may have ordered specific tortures before the execution, or a longer execution. For example, records showed that during Yuan Chonghuan

Yuan Chonghuan (; 6 June 1584 – 22 September 1630), courtesy name Yuansu or Ziru, was a Chinese politician, military general and writer who served under the Ming dynasty. Widely regarded as a patriot in Chinese culture, he is best known for d ...

's execution, Yuan was heard shouting for half a day before his death.

The flesh of the victims may also have been sold as medicine. As an official punishment, death by slicing may also have involved slicing the bones, cremation, and scattering of the deceased's ashes.

Western perceptions

The Western perception of ''lingchi'' has often differed considerably from actual practice, and some misconceptions persist to the present. The distinction between the sensationalised Western myth and the Chinese reality was noted by Westerners as early as 1895. That year, Australian traveller and later representative of the government of the Republic of ChinaGeorge Ernest Morrison

George Ernest Morrison (4 February 1862 – 30 May 1920) was an Australian journalist, political adviser to and representative of the government of the Republic of China during the First World War and owner of the then largest Asiatic library ...

, who claimed to have witnessed an execution by slicing, wrote that "''lingchi'' ascommonly, and quite wrongly, translated as 'death by slicing into 10,000 pieces' – a truly awful description of a punishment whose cruelty has been extraordinarily misrepresented ... The mutilation is ghastly and excites our horror as an example of barbarian cruelty; but it is not cruel, and need not excite our horror, since the mutilation is done, not before death, but after."

According to apocryphal lore, ''lingchi'' began when the torturer, wielding an extremely sharp knife, began by cutting out the eyes, rendering the condemned incapable of seeing the remainder of the torture and, presumably, adding considerably to the psychological terror of the procedure. Successive relatively minor cuts chopped off ears, nose, tongue, fingers, toes and genitals preceding cuts that removed large portions of flesh from more sizable parts, e.g., thighs and shoulders. The entire process was said to last three days, and to total 3,600 cuts. The heavily carved bodies of the deceased were then put on a parade for a show in the public. Some victims were reportedly given doses of opium to alleviate suffering.

John Morris Roberts

John Morris Roberts (14 April 1928 – 30 May 2003), often known as J. M. Roberts, was a British historian with significant published works. From 1979 to 1985 he was vice chancellor of the University of Southampton, and from 1985 to 1994 ...

, in ''Twentieth Century: The History of the World, 1901 to 2000'' (2000), writes "the traditional punishment of death by slicing ... became part of the western image of Chinese backwardness as the 'death of a thousand cuts'." Roberts then notes that slicing "was ordered, in fact, for K'ang Yu-Wei

Kang Youwei (; Cantonese: ''Hōng Yáuh-wàih''; 19March 185831March 1927) was a prominent political thinker and reformer in China of the late Qing dynasty. His increasing closeness to and influence over the young Guangxu Emperor spar ...

, a man termed the 'Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

of China', and a major advocate of intellectual and government reform in the 1890s".

Although officially outlawed by the government of the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-spea ...

in 1905, ''lingchi'' became a widespread Western symbol of the Chinese penal system from the 1910s on, and in Zhao Erfeng

Zhao Erfeng (1845–1911), courtesy name Jihe, was a late Qing Dynasty official and Han Chinese bannerman, who belonged to the Plain Blue Banner. He was an assistant amban in Tibet at Chamdo in Kham (eastern Tibet). He was appointed in March ...

's administration. Three sets of photographs shot by French soldiers in 1904–05 were the basis for later mythification. The abolition was immediately enforced, and definite: no official sentences of ''lingchi'' were performed in China after April 1905.

Regarding the use of opium, as related in the introduction to Morrison's book, Meyrick Hewlett insisted that "most Chinese people sentenced to death were given large quantities of opium before execution, and Morrison avers

Avers ( rm, Avras; wae, Òòver(s), , ) is a high Alpine valley region and a municipality in the Viamala Region in the Swiss canton of Graubünden. It includes Juf, the highest-altitude year-round settlement in Europe.

History

Avers is first ...

that a charitable person would be permitted to push opium into the mouth of someone dying in agony, thus hastening the moment of decease." At the very least, such tales were deemed credible to Western observers such as Morrison.

History

''Lingchi'' existed under the earliest emperors, although similar but less cruel tortures were often prescribed instead. Under the reign of

''Lingchi'' existed under the earliest emperors, although similar but less cruel tortures were often prescribed instead. Under the reign of Qin Er Shi

Qin Er Shi (; (230–October 207 BCE) was the second emperor of the Qin dynasty from 210 to 207 BCE. The son of Qin Shi Huang, he was born as Ying Huhai. He was put on the throne by Li Si and Zhao Gao, circumventing Fusu, Ying's brother a ...

, the second emperor of the Qin dynasty

The Qin dynasty ( ; zh, c=秦朝, p=Qín cháo, w=), or Ch'in dynasty in Wade–Giles romanization ( zh, c=, p=, w=Ch'in ch'ao), was the first dynasty of Imperial China. Named for its heartland in Qin state (modern Gansu and Shaanxi), ...

, various tortures were used to punish officials. The arbitrary, cruel, and short-lived Liu Ziye

Former Deposed Emperor of Liu Song or Emperor Qianfei ((劉)宋前廢帝) (25 February 449 – 1 January 466''wuwu'' day of the 11th month of the 1st year of the ''Yong'guang'' era, per Liu Ziye's biography in ''Book of Song''), personal name Liu ...

was apt to kill innocent officials by ''lingchi''. Gao Yang killed only six people by this method, and An Lushan

An Lushan (; 20th day of the 1st month 19 February 703 – 29 January 757) was a general in the Tang dynasty and is primarily known for instigating the An Lushan Rebellion.

An Lushan was of Sogdian and Göktürk origin,Yang, Zhijiu, "An Lush ...

killed only one man. ''Lingchi'' was known in the Five Dynasties

The Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (), from 907 to 979, was an era of political upheaval and division in 10th-century History of China#Imperial China, Imperial China. Five Dynasties in Chinese history, dynastic states quickly succeeded ...

period (907–960 CE); but, in one of the earliest such acts, Shi Jingtang abolished it. Other rulers continued to use it.

The method was prescribed in the Liao dynasty

The Liao dynasty (; Khitan language, Khitan: ''Mos Jælud''; ), also known as the Khitan Empire (Khitan: ''Mos diau-d kitai huldʒi gur''), officially the Great Liao (), was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China that exi ...

law codes, and was sometimes used. Emperor Tianzuo often executed people in this way during his rule. It became more widely used in the Song dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the rest ...

under Emperor Renzong and Emperor Shenzong.

Another early proposal for abolishing ''lingchi'' was submitted by Lu You

Lu You (; 1125–1210) was a Chinese historian and poet of the Southern Song Dynasty (南宋).

Career Early life and marriage

Lu You was born on a boat floating in the Wei River early on a rainy morning, November 13, 1125. At the time of his ...

(1125–1210) in a memorandum to the imperial court of the Southern Song dynasty. Lu You there stated, "When the muscles of the flesh are already taken away, the breath of life is not yet cut off, liver and heart are still connected, seeing and hearing still exist. It affects the harmony of nature, it is injurious to a benevolent government, and does not befit a generation of wise men." Lu You's elaborate argument against ''lingchi'' was dutifully copied and transmitted by generations of scholars, among them influential jurists of all dynasties, until the late Qing dynasty reformist Shen Jiaben (1840–1913) included it in his 1905 memorandum that obtained the abolition. This anti-''lingchi'' trend coincided with a more general attitude opposed to "cruel and unusual" punishments (such as the exposure of the head) that the Tang dynasty had not included in the canonic table of the Five Punishments

The Five Punishments () was the collective name for a series of physical penalties meted out by the legal system of pre-modern dynastic China. Over time, the nature of the Five Punishments varied. Before the time of Western Han dynasty Emperor H ...

, which defined the legal ways of punishing crime. Hence the abolitionist trend is deeply ingrained in the Chinese legal tradition, rather than being purely derived from Western influences.

Under later emperors, ''lingchi'' was reserved for only the most heinous acts, such as treason, a charge often dubious or false, as exemplified by the deaths of Liu Jin

Liu Jin (; 28 February 1451 – 25 August 1510) was a powerful Ming dynasty Chinese eunuch during the reign of the Zhengde Emperor.

Liu was famous for being one of the most influential officials in Chinese history. For some time, Liu was the em ...

, a Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last orthodox dynasty of China ruled by the Han peo ...

eunuch, and Yuan Chonghuan

Yuan Chonghuan (; 6 June 1584 – 22 September 1630), courtesy name Yuansu or Ziru, was a Chinese politician, military general and writer who served under the Ming dynasty. Widely regarded as a patriot in Chinese culture, he is best known for d ...

, a Ming dynasty general. In 1542, ''lingchi'' was inflicted on a group of palace women who had attempted to assassinate the Jiajing Emperor

The Jiajing Emperor (; 16September 150723January 1567) was the 12th Emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigning from 1521 to 1567. Born Zhu Houcong, he was the former Zhengde Emperor's cousin. His father, Zhu Youyuan (1476–1519), Prince of Xing, w ...

, along with his favourite concubine, Consort Duan. The bodies of the women were then displayed in public. Reports from Qing dynasty jurists such as Shen Jiaben show that executioners' customs varied, as the regular way to perform this penalty was not specified in detail in the penal code.

''Lingchi'' was also known in Vietnam, notably being used as the method of execution of the French missionary Joseph Marchand, in 1835, as part of the repression following the unsuccessful Lê Văn Khôi revolt

The Lê Văn Khôi revolt ( vi, Cuộc nổi dậy Lê Văn Khôi, 1833–1835) was an important revolt in 19th-century Vietnam, in which southern Vietnamese, Vietnamese Catholics, French Catholic missionaries and Chinese settlers under the ...

. An 1858 account by ''Harper's Weekly

''Harper's Weekly, A Journal of Civilization'' was an American political magazine based in New York City. Published by Harper & Brothers from 1857 until 1916, it featured foreign and domestic news, fiction, essays on many subjects, and humor, ...

'' claimed the martyr Auguste Chapdelaine was also killed by ''lingchi'' but in China; in reality he was beaten to death.

As Western countries moved to abolish similar punishments, some Westerners began to focus attention on the methods of execution used in China. As early as 1866, the time when Britain itself moved to abolish the practise of hanging, drawing, and quartering from the British legal system, Thomas Francis Wade

Sir Thomas Francis Wade, (25August 181831July 1895) was a British diplomat and sinologist who produced an early Chinese textbook in English, in 1867, that was later amended, extended and converted into the Wade-Giles romanization system for M ...

, then serving with the British diplomatic mission in China, unsuccessfully urged the abolition of ''lingchi''. ''Lingchi'' remained in the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-spea ...

's code of laws for persons convicted of high treason and other serious crimes, but the punishment was abolished as a result of the 1905 revision of the Chinese penal code by Shen Jiaben.

People put to death by ''lingchi''

Ming dynasty

*Fang Xiaoru

Fang Xiaoru (; 1357–1402), courtesy name Xizhi (希直) or Xigu (希古), was a Chinese politician and Confucian scholar of the Ming dynasty. He was an orthodox Confucian scholar-bureaucrat, famous for his continuation of the Jinhua school of ...

(方孝孺): trusted bureaucrat of the Hanlin Academy relied upon by the Jianwen Emperor

The Jianwen Emperor (5 December 1377 – ?), personal name Zhu Yunwen (), was the second Emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigned from 1398 to 1402. The era name of his reign, Jianwen, means "establishing civility" and represented a sharp chan ...

, put to death by ''lingchi'' in 1402 outside of Nanjing's Jubao Gate due to his refusal to draft an edict confirming the ascendance of the Yongle Emperor

The Yongle Emperor (; pronounced ; 2 May 1360 – 12 August 1424), personal name Zhu Di (), was the third Emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigning from 1402 to 1424.

Zhu Di was the fourth son of the Hongwu Emperor, the founder of the Ming dyn ...

to the throne. He was forced to witness the brutal, special ten familial exterminations, the only one in history, where his family, friends and students were all executed, before he himself was killed.

* (曹吉祥): important eunuch

A eunuch ( ) is a male who has been castrated. Throughout history, castration often served a specific social function.

The earliest records for intentional castration to produce eunuchs are from the Sumerian city of Lagash in the 2nd millenni ...

serving under Emperor Yingzong of Ming

Emperor Yingzong of Ming (; 29 November 1427 – 23 February 1464), personal name Zhu Qizhen (), was the sixth and eighth Emperor of the Ming dynasty. He ascended the throne as the Zhengtong Emperor () in 1435, but was forced to abdicate in ...

, put to death by ''lingchi'' in 1461 for leading an army in rebellion.

* Sang Chong (桑沖): put to death by ''lingchi'' during the reign of the Chenghua Emperor

The Chenghua Emperor (; 9 December 1447 – 9 September 1487), personal name Zhu Jianshen, was the ninth Emperor of the Ming dynasty, who reigned from 1464 to 1487. His era name " Chenghua" means "accomplished change".

Childhood

Zhu Jianshen wa ...

for the rape of 182 women.

* Zheng Wang (郑旺): peasant from Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

, put to death by ''lingchi'' in 1506 for claiming that the newly enthroned Zhengde Emperor

The Zhengde Emperor (; 26 October 149120 April 1521) was the 11th Emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigned from 1505 to 1521.

Born Zhu Houzhao, he was the Hongzhi Emperor's eldest son. Zhu Houzhao took the throne at only 14 with the era name Zh ...

's birth mother was not Empress Zhang (Hongzhi), but Zheng Jinlian, Zheng Wang's daughter, causing massive controversy.

* Liu Jin

Liu Jin (; 28 February 1451 – 25 August 1510) was a powerful Ming dynasty Chinese eunuch during the reign of the Zhengde Emperor.

Liu was famous for being one of the most influential officials in Chinese history. For some time, Liu was the em ...

(劉瑾): important eunuch serving under the Zhengde Emperor

The Zhengde Emperor (; 26 October 149120 April 1521) was the 11th Emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigned from 1505 to 1521.

Born Zhu Houzhao, he was the Hongzhi Emperor's eldest son. Zhu Houzhao took the throne at only 14 with the era name Zh ...

, put to death by ''lingchi'' in 1510 for arrogating power. Legend has it that the punishment was carried out across 3 days, with 3300 slices in total. It was reported that when Liu Jin returned to prison after the first day, he continued to eat white porridge. After the punishment was completed, the people of Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

, especially those persecuted under Liu Jin and their families, haggled for pieces of his flesh for a wen

Wen, wen, or WEN may refer to:

* WEN, New York Stock Exchange symbol for Wendy's/Arby's Group

* WEN, Amtrak station code for Columbia Station in Wenatchee, Washington, United States

* WEN, ICAO airline designator for WestJet Encore

* Wen (surnam ...

, and ate them with wine, to vent their anger.

* Palace plot of Renyin year: the 16 palace maids involved, including Yang Jinying and Huang Yulian, along with Imperial Concubine Wang Ning and Consort Duan were all put to death by ''lingchi'' in 1542 for the attempted assassination of the Jiajing Emperor

The Jiajing Emperor (; 16September 150723January 1567) was the 12th Emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigning from 1521 to 1567. Born Zhu Houcong, he was the former Zhengde Emperor's cousin. His father, Zhu Youyuan (1476–1519), Prince of Xing, w ...

.

* Wang Gao (王杲): a Jianzhou Jurchen

The Jianzhou Jurchens () were one of the three major groups of Jurchens as identified by the Ming dynasty. Although the geographic location of the Jianzhou Jurchens changed throughout history, during the 14th century they were located south of t ...

awarded a position of command in Jianzhou. He was put to death by ''lingchi'' at Beijing in 1575 due to repeated raids into Ming border territories. He is said to be Nurhaci

Nurhaci (14 May 1559 – 30 September 1626), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Taizu of Qing (), was a Jurchen chieftain who rose to prominence in the late 16th century in Manchuria. A member of the House of Aisin-Gioro, he reigned ...

's maternal great-grandfather or maternal grandfather.

* Zheng Man (鄭鄤): a shujishi

Shujishi (; Manchu: ''geren giltusi'') which means "All good men of virtue" is a scholastic title during the Ming and Qing dynasty of China. It can be used to denote a group of people who hold this title as well as individuals who possess the ti ...

during the reign of the Chongzhen Emperor

The Chongzhen Emperor (; 6 February 1611 – 25 April 1644), personal name Zhu Youjian (), courtesy name Deyue (),Wang Yuan (王源),''Ju ye tang wen ji'' (《居業堂文集》), vol. 19. "聞之張景蔚親見烈皇帝神主題御諱字德� ...

, who was defamed by Chief Grand Secretary Wen Tiren and charged with the crimes of "causing his mother to be caned (due to ''fuji''), and raping his younger sister and daughter-in-law". Executed by ''lingchi'' in 1636.

* Yuan Chonghuan

Yuan Chonghuan (; 6 June 1584 – 22 September 1630), courtesy name Yuansu or Ziru, was a Chinese politician, military general and writer who served under the Ming dynasty. Widely regarded as a patriot in Chinese culture, he is best known for d ...

(袁崇煥): famous general during the reign of the Chongzhen Emperor

The Chongzhen Emperor (; 6 February 1611 – 25 April 1644), personal name Zhu Youjian (), courtesy name Deyue (),Wang Yuan (王源),''Ju ye tang wen ji'' (《居業堂文集》), vol. 19. "聞之張景蔚親見烈皇帝神主題御諱字德� ...

, entrusted with defence against the Jurchens

Jurchen (Manchu: ''Jušen'', ; zh, 女真, ''Nǚzhēn'', ) is a term used to collectively describe a number of East Asian Tungusic-speaking peoples, descended from the Donghu people. They lived in the northeast of China, later known as Manch ...

. The Emperor reportedly fell for the Jurchens' stratagem of sowing discord, and sentenced him to death by ''lingchi'' for the crime of attempting to rebel with the help of the Jurchens. It is said that the people of Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

, not knowing of Yuan's innocence, fought to eat pieces of his flesh.

Qing dynasty

*Geng Jingzhong

Geng Jingzhong (; died 1682) was a powerful military commander of the early Qing dynasty. He inherited the title of "King/Prince of Jingnan" (靖南王) from his father Geng Jimao, who had inherited it from Jingzhong's grandfather Geng Zhongming ...

(耿精忠): one of the rulers of the Three Feudatories during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor

The Kangxi Emperor (4 May 1654– 20 December 1722), also known by his temple name Emperor Shengzu of Qing, born Xuanye, was the third emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the second Qing emperor to rule over China proper, reigning from 1661 to ...

. He was put to death by ''lingchi'' after their revolt failed.

* He Luohui (何洛會) and Hu Ci (胡錫): put to death by ''lingchi'' due to their earlier defamation of Hooge, Prince Su

Hooge ( Manchu: ; 16 April 1609 – 4 May 1648), formally known as Prince Su, was a Manchu prince of the Qing dynasty. He was the eldest son of Hong Taiji, the second ruler of the Qing dynasty.

Life

Hooge was born in the Aisin Gioro clan a ...

.

* Zhu Yigui

Zhu Yigui (; 1690–1722) was the leader of a Taiwanese uprising against Qing dynasty rule in mid-1721.

He came from a peasant family of Zhangzhou Hokkien ancestry and lived in the village of Lohanmen located in the area of modern-day Neimen Dist ...

(朱一貴): duck farmer in Taiwan during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor

The Kangxi Emperor (4 May 1654– 20 December 1722), also known by his temple name Emperor Shengzu of Qing, born Xuanye, was the third emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the second Qing emperor to rule over China proper, reigning from 1661 to ...

. Unhappy with the local governor's indulgence of his son's excesses, he revolted to re-establish the Ming dynasty by claiming to be a descendant of the Hongwu Emperor. After the revolt failed, he was transported to Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

and put to death by ''lingchi''.

* On 1 November 1728, after the Qing reconquest of Lhasa in Tibet, several Tibetan rebels were sliced to death by Qing Manchu officers and officials in front of the Potala Palace

The Potala Palace is a ''dzong'' fortress in Lhasa, Tibet. It was the winter palace of the Dalai Lamas from 1649 to 1959, has been a museum since then, and a World Heritage Site since 1994.

The palace is named after Mount Potalaka, the mythic ...

. Qing Manchu President of the Board of Civil Office, Jalangga, Mongol sub-chancellor Sen-ge and brigadier-general Manchu Mala ordered Tibetan rebels Lum-pa-nas and Na-p'od-pa to be sliced. Tibetan rNam-rgyal-grva-ts'an college administrator (gner-adsin) and sKyor'lun Lama were tied together with Lum-pa-nas and Na-p'od-pa on four scaffolds (k'rims-sin) to be sliced. The Manchus used musket matchlocks to fire three salvoes and then the Manchus strangled the two lamas while slicing Lum-pa-nas and Na-p'od-pa to death. The Tibetan population was depressed by the scene and the writer of MBTJ continued to feel sad as he described it 5 years later. The public execution spectacle worked on the Tibetans since they were "cowed into submission" by the Qing. Even the Tibetan collaborator with the Qing, Polhané Sönam Topgyé (P'o-lha-nas), felt sad at his fellow Tibetans being executed in this manner and prayed for them. All of this was included in a report sent to the Qing Yongzheng Emperor

The Yongzheng Emperor (13 December 1678 – 8 October 1735), also known by his temple name Emperor Shizong of Qing, born Yinzhen, was the fourth Emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the third Qing emperor to rule over China proper. He reigned from ...

.

* On 23 January 1751 (25/XII), Tibetan rebels who participated in the Lhasa riot of 1750 against the Qing were sliced to death by Qing Manchu general Bandi, similar to what happened on 1 November 1728. 6 Tibetan rebel leaders plus Tibetan rebel leader Blo-bzan-bkra-sis were sliced to death. Manchu General Bandi sent a report to the Qing Qianlong emperor on 26 January 1751 on how he carried out the slicing of the Tibetan rebels: dBan-rgyas (Wang-chieh), Padma-sku-rje-c'os-a 額爾登額)_or_possibly_w:zh:額爾景額.html" ;"title="w:zh:額爾登額.html" ;"title="el (Pa-t'e-ma-ku-erh-chi-ch'un-p'i-lo) and Tarqan Yasor (Ta-erh-han Ya-hsün) were sliced to death for injuring the Manchu ambans with arrows, bows and fowling pieces during the Lhasa riot when they assaulted the building the Manchu ambans (Labdon and Fucin) were in; Sacan Hasiha (Ch'e-ch'en-ha-shih-ha) for murder of multiple individuals; Ch'ui-mu-cha-t'e and Rab-brtan (A-la-pu-tan) for looting money and setting fire during the attack on the Ambans; Blo-bzan-bkra-sis, the mgron-gner for being the overall leader of the rebels who led the attack which looted money and killed the Manchu ambans.

* Eledeng'e (w:zh:額爾登額">額爾登額) or possibly w:zh:額爾景額">額爾景額): The Qianlong emperor ordered Manchu general Eledeng'e (also spelled E'erdeng'e 額爾登額) to be sliced to death after his commander Mingrui was defeated at the Battle of Maymyo in the Sino-Burmese War#Third invasion (1767–1768), Sino-Burmese War in 1768 because Eledeng'i was not able to help flank Mingrui when he did not arrive at a rendezvous.

* Chen De (陈德): a retrenched chef during the reign of the Jiaqing Emperor

The Jiaqing Emperor (13 November 1760 – 2 September 1820), also known by his temple name Emperor Renzong of Qing, born Yongyan, was the sixth emperor of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty, and the fifth Qing emperor to rule over China proper, from ...

. Put to death by ''lingchi'' in 1803 for a failed assassination of the emperor outside the Forbidden City

The Forbidden City () is a palace complex in Dongcheng District, Beijing, China, at the center of the Imperial City of Beijing. It is surrounded by numerous opulent imperial gardens and temples including the Zhongshan Park, the sacrifi ...

.

* Zhang Liangbi Zhang may refer to:

Chinese culture, etc.

* Zhang (surname) (張/张), common Chinese surname

** Zhang (surname 章), a rarer Chinese surname

* Zhang County (漳县), of Dingxi, Gansu

* Zhang River (漳河), a river flowing mainly in Henan

* Zhang ...

(张良璧): a pedophile

Pedophilia ( alternatively spelt paedophilia) is a psychiatric disorder in which an adult or older adolescent experiences a primary or exclusive sexual attraction to prepubescent children. Although girls typically begin the process of puberty a ...

during the reign of the Jiaqing Emperor

The Jiaqing Emperor (13 November 1760 – 2 September 1820), also known by his temple name Emperor Renzong of Qing, born Yongyan, was the sixth emperor of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty, and the fifth Qing emperor to rule over China proper, from ...

. He was 70 years old when caught. He was in put to death by ''lingchi'' in 1811 for raping 16 underage girls, resulting in the deaths of 11 of them.

* Pan Zhaoxiang (潘兆祥): poisoned his father. Put to death by ''lingchi'' on 24 June in the fifth year of the reign of the Daoguang Emperor

The Daoguang Emperor (; 16 September 1782 – 26 February 1850), also known by his temple name Emperor Xuanxong of Qing, born Mianning, was the seventh Emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the sixth Qing emperor to rule over China proper, reigning ...

(1825).

* Jahangir Khoja

Jahanghir Khoja, Jāhangīr Khwāja or Jihangir Khoja (, جهانگير خوجة; ; 1788 – 1828), was a member of the influential East Turkestan Afaqi khoja clan, who managed to wrest Kashgaria from the Qing Empire's power for a few year ...

( 張格爾): a Uyghur Muslim Sayyid

''Sayyid'' (, ; ar, سيد ; ; meaning 'sir', 'Lord', 'Master'; Arabic plural: ; feminine: ; ) is a surname of people descending from the Islamic prophet Muhammad through his grandsons, Hasan ibn Ali and Husayn ibn Ali, sons of Muhamma ...

and Naqshbandi Sufi rebel of the Afaqi suborder, Jahangir Khoja was sliced to death in 1828 by the Manchus for leading a rebellion against the Qing.

* Li Shangfa (李尚發): slashed his mother to death in a fit of hysteria. Put to death by ''lingchi'' in May of the 25th year of the reign of the Daoguang Emperor

The Daoguang Emperor (; 16 September 1782 – 26 February 1850), also known by his temple name Emperor Xuanxong of Qing, born Mianning, was the seventh Emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the sixth Qing emperor to rule over China proper, reigning ...

(1845). Three bystanders were sentenced to 100 strokes of the cane each for not moving to stop him.

* Shi Dakai

Shi Dakai (1 March 1831 – 25 June 1863; ), born in Guigang, Guangxi, also known as Wing King () or phonetically translated as Yi-Wang, was one of the most highly acclaimed leaders in the Taiping Rebellion and a poet.

Early life

Shi Dakai wa ...

(石達開): the most decorated general of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom

The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, later shortened to the Heavenly Kingdom or Heavenly Dynasty, was an unrecognised rebel kingdom in China and a Chinese Christian theocratic absolute monarchy from 1851 to 1864, supporting the overthrow of the Q ...

, proclaimed as the Wing King. He was trapped during a crossing of the Dadu River

The Dadu River (), known in Tibetan as the Gyelmo Ngul Chu, is a major river located primarily in Sichuan province, southwestern China. The Dadu flows from the eastern Tibetan Plateau into the Sichuan Basin where it joins with the Min River, a t ...

due to a sudden flood, and surrendered to Qing forces to save his army. He was put to death by ''lingchi'' together with his immediate subordinates. He chided his subordinates for crying in pain during their ordeal, and he himself said not a word during his turn.

* Hong Tianguifu

Hong Tianguifu (23 November 1849 – 18 November 1864) was the second and last king of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. He is popularly referred to as the Junior Lord (). Officially, like his father Hong Xiuquan, he was the King of Heaven (). To dif ...

(洪天貴福): son of the Heavenly King Hong Xiuquan

Hong Xiuquan (1 January 1814 – 1 June 1864), born Hong Huoxiu and with the courtesy name Renkun, was a Chinese revolutionary who was the leader of the Taiping Rebellion against the Qing dynasty. He established the Taiping Heavenly Kingdo ...

of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom

The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, later shortened to the Heavenly Kingdom or Heavenly Dynasty, was an unrecognised rebel kingdom in China and a Chinese Christian theocratic absolute monarchy from 1851 to 1864, supporting the overthrow of the Q ...

. He was captured by famous general Shen Baozhen

Shen Baozhen (1820–1879), formerly romanized , was an official during the Qing dynasty.

Biography

Born in Minhou in Fujian province, he obtained the highest degree in the imperial examinations in 1847 and was soon appointed to the Hanlin ...

and put to death by ''lingchi''. He was possibly the youngest to ever have been subjected to ''lingchi'', at 14 years old.

* Lin Fengxiang (林鳳祥): general of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom

The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, later shortened to the Heavenly Kingdom or Heavenly Dynasty, was an unrecognised rebel kingdom in China and a Chinese Christian theocratic absolute monarchy from 1851 to 1864, supporting the overthrow of the Q ...

. Put to death by ''lingchi'' in March 1855 at the Beijing Caishikou Execution Grounds

Caishikou Execution Grounds (), also known as Vegetable Market Execution Ground, was an important execution ground in Beijing during the Qing Dynasty. It was located at the crossroads of Xuanwumen Outer Street and Luomashi Street. The exact locat ...

. Reportedly, the process was recorded.

* Kumud Pazik (古穆·巴力克): a chief of the Sakizaya people

The Sakizaya (native name: Sakuzaya, literally "real man"; ; occasionally Sakiraya or Sakidaya) are Taiwanese indigenous peoples with a population of approximately 1,000. They primarily live in Hualien (formerly known as ''Kiray''), where their ...

in Hualien County

Hualien County ( Mandarin Wade–Giles: Hua¹-lien² Hsien⁴; Pīnyīn: ''Huālián Xiàn''; Hokkien POJ: ''Hoa-lian-koān'' or ''Hoa-liân-koān''; Hakka PFS: ''Fâ-lièn-yen''; Amis: ''Kalingko'') is a county on the east coast of Taiwan. I ...

, Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the nort ...

. He allied with the Kavalan people

The Kavalan (endonym ; "people living in the plain"; ) or Kuvalan are an indigenous people of Taiwan. Most of them moved to the coastal area of Hualien County and Taitung County in the 19th century due to encroachment by Han settlers. Their la ...

in armed rebellion against the Qing's expansionist policies against the Taiwanese indigenous peoples (a result of the Japanese invasion of Taiwan in 1874). He was publicly put to death by ''lingchi'' on 9 September 1878 as a warning to the various villages in the aftermath of the Karewan Incident.

* Kang Xiaoba (康小八): a bandit who robbed and killed countless innocents, armed with a gun stolen from Westerners. He caused disturbances in Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

, managing to scare Empress Dowager Cixi

Empress Dowager Cixi ( ; mnc, Tsysi taiheo; formerly romanised as Empress Dowager T'zu-hsi; 29 November 1835 – 15 November 1908), of the Manchu Yehe Nara clan, was a Chinese noblewoman, concubine and later regent who effectively controlled ...

, before he was caught and put to death by ''lingchi''.

* Wang Weiqin (王維勤): an influential landowner in his village in Shandong who masterminded the killings of a rival family of twelve. He was put to death by ''lingchi'' in October 1904. He rode a chariot to the execution grounds, so he was suspected to have much influence. French soldiers took photos of the execution, and it is believed that this is the first time photographs of ''lingchi'' spread overseas.

* Fujuri (富珠哩): a Mongol prince's slave, who reportedly rebelled against said prince because the prince tried to force himself upon Fujuri's wife. He was put to death by ''lingchi'' on 10 April 1905. ''Lingchi'' was abolished as a punishment two weeks later, due to pressure by Westerners, in part because French soldiers took clear photos of Fujuri's execution.

* Xu Xilin

Xu Xilin (December 17 1873 – July 7 1907), was a Chinese revolutionary born in Dongpu, Shanyin, Shaoxing, Zhejiang during the Qing dynasty.

Xu was sent to Japan in 1903 for study where he joined other Zhejiang students in rescuing Zhan ...

(徐錫麟): a member of the Guangfuhui {{Unreferenced, date=December 2009

Guangfuhui ( zh, t=光復會, p=Guāngfùhuì, l=Revive the Light Society), or the Restoration Society, was an anti-Qing organization established by Cai Yuanpei in 1904. Many members were from Zhejiang. Notable me ...

; put to death by ''lingchi'' on 6 July 1907.

Republican era

* Ling Fushun (凌福顺): soldier of theChinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Civil ...

, who was caught at Puyuanzhen in Zhouning County

Zhouning County (; Foochow Romanized: Ciŭ-nìng-gâing) is a county of northeastern Fujian province, People's Republic of China. It is under the administration of the prefecture-level city of Ningde

Ningde (; Foochow Romanized: Nìng-dáik), als ...

after returning from soliciting donations in Jian'ou

Jian'ou is a county-level city in Nanping in northern Fujian province, China. Under the name Jianning (Kienning), it was formerly the seat of its own prefecture and was the namesake of its province.

Jian'ou is within a major bamboo and rice ...

. He was put to death by ''lingchi'' by Republican forces on 25 April 1936.

Published accounts

* Sir Henry Norman, ''The People and Politics of the Far East'' (1895). Norman was a Liberal British Parliamentarian and government minister whose collection is now owned by theUniversity of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209 and granted a royal charter by Henry III in 1231, Cambridge is the world's third oldest surviving university and one of its most pr ...

. Norman gives an eyewitness account of various physical punishments and tortures inflicted in a magistrate's court (''yamen

A ''yamen'' (''ya-men''; ; Manchu: ''yamun'') was the administrative office or residence of a local bureaucrat or mandarin in imperial China. A ''yamen'' can also be any governmental office or body headed by a mandarin, at any level of gover ...

'') and of the execution by beheading of 15 men. He gives the following graphic account of a ''lingchi'' execution but does not claim to have witnessed such an execution himself. " he executionergrasping handfuls from the fleshy parts of the body such as the thighs and breasts slices them away ... the limbs are cut off piecemeal at the wrists and ankles, the elbows and knees, shoulders and hips. Finally the condemned is stabbed to the heart and the head is cut off."

* George Ernest Morrison

George Ernest Morrison (4 February 1862 – 30 May 1920) was an Australian journalist, political adviser to and representative of the government of the Republic of China during the First World War and owner of the then largest Asiatic library ...

, ''An Australian in China'' (1895) differs from some other reports in stating that most ''lingchi'' mutilations are in fact made postmortem. Morrison wrote his description based on an account related by a claimed eyewitness: "The prisoner is tied to a rude cross: he is invariably deeply under the influence of opium. The executioner, standing before him, with a sharp sword makes two quick incisions above the eyebrows, and draws down the portion of skin over each eye, then he makes two more quick incisions across the breast, and in the next moment he pierces the heart, and death is instantaneous. Then he cuts the body in pieces; and the degradation consists in the fragmentary shape in which the prisoner has to appear in heaven."

* ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' (f ...

'' (9 December 1927), a journalist reported from Canton that the Communists were targeting Christian priests and that "It was announced that Father Wong was to be publicly executed by the slicing process."

* George de Roerich

George Nicolas de Roerich ( Russian: Юрий Николаевич Рёрих, ; August 16, 1902 in Okulovka, Novgorod Governorate – May 21, 1960 in Moscow) was a prominent 20th century Tibetologist. His name at birth was Yuri Nikolaevich Reri ...

, ''Trails to Inmost Asia'' (1931), p . 119, relates the story of the assassination of Yang Tseng-hsin, Governor of Sinkiang

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwest ...

in July 1928, by the bodyguard of his foreign minister Fan Yao-han. Fan was seized, and he and his daughter were both executed by ''lingchi'', the minister forced to watch his daughter's execution first. Roerich was not an eyewitness to this event, having already returned to India by the date of the execution.

* George Ryley Scott

George Ryley Scott (6 October 1886 – c. 1980) was a prolific British author of books about sexual intercourse, active from the late 1920s to the 1970s. He also wrote on the subjects of poultry, health, corporal punishment, and writing itself. ...

in ''History of Torture'' (1940) claims that many were executed this way by the Chinese Communist insurgents; he cites claims made by the Nanking government in 1927. It is likely that these claims were anti-communist propaganda. Scott also uses the term "the slicing process" and differentiates between the different types of execution in different parts of the country. There is no mention of opium. Riley's book contains a picture of a sliced corpse (with no mark to the heart) that was killed in Guangzhou (Canton) in 1927. It gives no indication of whether the slicing was done post-mortem. Scott claims it was common for the relatives of the condemned to bribe the executioner to kill the condemned before the slicing procedure began.

Photographs

The first Western photographs of ''lingchi'' were taken in 1890 by William Arthur Curtis of Kentucky in Canton.

French soldiers stationed in

The first Western photographs of ''lingchi'' were taken in 1890 by William Arthur Curtis of Kentucky in Canton.

French soldiers stationed in Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

had the opportunity to photograph three different ''lingchi'' executions in 1904 and 1905:

* Wang Weiqin (王維勤), a former official who killed two families, executed on 31 October 1904.

* Unknown, reason unknown, possibly a young deranged boy who killed his mother, and was executed in January 1905. Photographs were published in various volumes of Georges Dumas' ''Nouveau traité de psychologie'', 8 vols., Paris, 1930–1943, and again nominally by Bataille (in fact by Lo Duca), who mistakenly appended abstracts of Fou-tchou-li's executions as related by Carpeaux (see below).

* Fou-tchou-li or Fuzhuli (符珠哩), a Mongol guard who killed his master, the Prince of the Aohan Banner

Aohan Banner ( Mongolian: ''Aoqan qosiɣu''; ) is a banner of southeastern Inner Mongolia, People's Republic of China, bordering Liaoning province to the south. It is under the administration of Chifeng

Chifeng ( zh, s=赤峰市), also known ...

of Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China. Its border includes most of the length of China's border with the country of Mongolia. Inner Mongolia also accounts for a ...

, and who was executed on 10 April 1905; as ''lingchi'' was to be abolished two weeks later, this was presumably the last attested case of ''lingchi'' in Chinese history, or said Kang Xiaoba (康小八) Photographs appeared in books by Matignon (1910), and Carpeaux (1913), the latter claiming (falsely) that he was present. Carpeaux's narrative was mistakenly, but persistently, associated with photographs published by Dumas and Bataille. Even related to the correct set of photos, Carpeaux's narrative is highly dubious; for instance, an examination of the Chinese judicial archives shows that Carpeaux bluntly invented the execution decree. The proclamation is reported to state: "The Mongolian princes demand that the aforesaid Fou-Tchou-Le, guilty of the murder of Prince Ao-Han-Ouan, be burned alive, but the Emperor finds this torture too cruel and condemns Fou-Tchou-Li to slow death by ''leng-tch-e'' (different spelling of ''lingchi'', cutting into pieces)."

Popular culture

Accounts of ''lingchi'' or the extant photographs have inspired or referenced in numerous artistic, literary, and cinematic media:Nonfiction

Susan Sontag mentions the 1905 case in ''Regarding the Pain of Others'' (2003). One reviewer wrote that though Sontag includes no photographs in her book – a volume about photography – "she does tantalisingly describe a photograph that obsessed the philosopher Georges Bataille, in which a Chinese criminal, while being chopped up and slowlyflayed

Flaying, also known colloquially as skinning, is a method of slow and painful execution in which skin is removed from the body. Generally, an attempt is made to keep the removed portion of skin intact.

Scope

A dead animal may be flayed when pr ...

by executioners, rolls his eyes heavenwards in transcendent bliss." Bataille wrote about ''lingchi'' in (1943) and in (1944). He included five pictures in his ''The Tears of Eros'' (1961; translated into English and published by City Lights in 1989).

Music

The tenth song onTaylor Swift

Taylor Alison Swift (born December 13, 1989) is an American singer-songwriter. Her discography spans multiple genres, and her vivid songwriting—often inspired by her personal life—has received critical praise and wide media coverage. Bor ...

's ninth album, '' Lover'', is entitled "Death By A Thousand Cuts" and compares the singer's heartbreak to this ancient Chinese punishment.

Literature

The "death by a thousand cuts" with reference to China is mentioned inAmy Tan

Amy Ruth Tan (born on February 19, 1952) is an American author known for the novel '' The Joy Luck Club,'' which was adapted into a film of the same name, as well as other novels, short story collections, and children's books.

Tan has written ...

's novel '' The Joy Luck Club'', and Robert van Gulik

Robert Hans van Gulik (, 9 August 1910 – 24 September 1967) was a Dutch orientalist, diplomat, musician (of the guqin), and writer, best known for the Judge Dee historical mysteries, the protagonist of which he borrowed from the 18th-century ...

's ''Judge Dee

Judge Dee, or Judge Di, is a semi-fictional character based on the historical figure Di Renjie, county magistrate and statesman of the Tang court. The character appeared in the 18th-century Chinese detective and '' gong'an'' crime novel ''Di Gong ...

'' novels. The 1905 photos are mentioned in Thomas Harris

William Thomas Harris III (born 1940/1941) is an American writer, best known for a series of suspense novels about his most famous character, Hannibal Lecter. The majority of his works have been adapted into films and television, the most notab ...

' novel '' Hannibal'' and in Julio Cortázar's novel ''Hopscotch

Hopscotch is a popular playground game in which players toss a small object, called a lagger, into numbered triangles or a pattern of rectangles outlined on the ground and then hop or jump through the spaces and retrieve the object. It is a ch ...

''. Agustina Bazterrica mentioned the torture in her book ''Tender is the Flesh'', as the method used by the sister of the protagonist to make the meat served at the memorial party fresh and tasty. The Chinese idiom "千刀萬剮" ''qiāndāo wànguǎ'' is also a reference to ''linchi''.

Film

A scene of Lingchi appeared in the 1966 film ''The Sand Pebbles

''The Sand Pebbles'' is a 1962 novel by American author Richard McKenna about a Yangtze River gunboat and its crew in 1926. It was the winner of the 1963 Harper Prize for fiction. The book was initially serialized in the ''Saturday Evening Po ...

''. Inspired by the 1905 photos, Chinese artist Chen Chieh-jen created a 25-minute, 2002 video called ''Lingchi – Echoes of a Historical Photograph'', which has generated some controversy. The 2007 film ''The Warlords

''The Warlords'' (), previously known as ''The Blood Brothers'', is a 2007 epic action war drama film directed by Peter Chan and starring Jet Li, Andy Lau, Takeshi Kaneshiro and Xu Jinglei. The film was released on 13 December 2007 simultaneo ...

'', which is loosely based on historical events during the Taiping Rebellion

The Taiping Rebellion, also known as the Taiping Civil War or the Taiping Revolution, was a massive rebellion and civil war that was waged in China between the Manchu-led Qing dynasty and the Han, Hakka-led Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. It laste ...

, ended with one of its main characters executed by Lingchi. Lingchi is shown as a method of execution in the 2014 TV series ''The 100 The 100 may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* 100 (DC Comics), fictional organized crime groups appearing in DC Comics

* ''The 100'' (novel series), a 2013–2016 science fiction novel series written by Kass Morgan

* ''The 100'' (TV series), 20 ...

''. Lingchi was portrayed in the 2015 Netflix-exclusive TV series '' Jessica Jones''.

See also

* ''Death by a Thousand Cuts

''Lingchi'' (; ), translated variously as the slow process, the lingering death, or slow slicing, and also known as death by a thousand cuts, was a form of torture and execution used in China from roughly 900 CE up until the practice ended aro ...

'' – a 2008 book that examines the practice of ''lingchi''

* Hanged, drawn and quartered – an English method of torturous execution

* Scaphism

Scaphism (from Greek , meaning "boat"), also known as the boats, is an alleged ancient Persian method of execution mentioned by Plutarch in his ''Life of Artaxerxes''. It ostensibly entailed trapping the victim between two boats, feeding and cove ...

– an alleged ancient Persian method of torturous execution

* Sinophobia

Anti-Chinese sentiment, also known as Sinophobia, is a fear or dislike of China, Chinese people or Chinese culture. It often targets Chinese minorities living outside of China and involves immigration, development of national identity in ...

* Tameshigiri

''Tameshigiri'' (試し斬り, 試し切り, 試斬, 試切) is the Japanese art of target test cutting. The kanji literally mean "test cut" (kun'yomi: ためし ぎり ''tameshi giri''). This practice was popularized in the Edo period (17th ce ...

– in Japan, cuts for testing swords, sometimes used on people

* Waist chop

Waist chop or waist cutting (), also known as cutting in two at the waist, was a form of execution used in ancient China. As its name implies, it involved the condemned being sliced in two at the waist by an executioner.

History

Waist chopping ...

– a form of execution in China, also noted for causing a lingering death

* Yellow Peril

The Yellow Peril (also the Yellow Terror and the Yellow Specter) is a racial color metaphor that depicts the peoples of East and Southeast Asia as an existential danger to the Western world. As a psychocultural menace from the Eastern world ...

Notes

References

* * {{capital punishment 1905 disestablishments in China Capital punishment in China Execution methods History of Imperial China Torture in China *