Laurence Olivier (borders removed).jpg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier (; 22 May 1907 – 11 July 1989) was an English actor and director who, along with his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and

Olivier was born in Dorking, Surrey, the youngest of the three children of the Reverend Gerard Kerr Olivier (1869–1939) and his wife Agnes Louise, ''née'' Crookenden (1871–1920). Their elder children were Sybille (1901–1989) and Gerard Dacres "Dickie" (1904–1958). His great-great-grandfather was of French

Olivier was born in Dorking, Surrey, the youngest of the three children of the Reverend Gerard Kerr Olivier (1869–1939) and his wife Agnes Louise, ''née'' Crookenden (1871–1920). Their elder children were Sybille (1901–1989) and Gerard Dacres "Dickie" (1904–1958). His great-great-grandfather was of French  In 1916, after attending a series of preparatory schools, Olivier passed the singing examination for admission to the choir school of

In 1916, after attending a series of preparatory schools, Olivier passed the singing examination for admission to the choir school of

One of Olivier's contemporaries at the school was

One of Olivier's contemporaries at the school was

In 1931 RKO Pictures offered Olivier a two-film contract at $1,000 a week; he discussed the possibility with Coward, who, irked, told Olivier "You've no artistic integrity, that's your trouble; this is how you cheapen yourself." He accepted and moved to Hollywood, despite some misgivings. His first film was the drama '' Friends and Lovers'', in a supporting role, before RKO loaned him to

In 1931 RKO Pictures offered Olivier a two-film contract at $1,000 a week; he discussed the possibility with Coward, who, irked, told Olivier "You've no artistic integrity, that's your trouble; this is how you cheapen yourself." He accepted and moved to Hollywood, despite some misgivings. His first film was the drama '' Friends and Lovers'', in a supporting role, before RKO loaned him to

After ''Hamlet'', the company presented ''Twelfth Night'' in what the director,

After ''Hamlet'', the company presented ''Twelfth Night'' in what the director,

In 1938 Olivier joined Richardson to film the spy thriller ''

In 1938 Olivier joined Richardson to film the spy thriller '' After returning to London briefly in mid-1939, the couple returned to America, Leigh to film the final takes for ''Gone with the Wind'', and Olivier to prepare for filming of Alfred Hitchcock's '' Rebecca''—although the couple had hoped to appear in it together. Instead,

After returning to London briefly in mid-1939, the couple returned to America, Leigh to film the final takes for ''Gone with the Wind'', and Olivier to prepare for filming of Alfred Hitchcock's '' Rebecca''—although the couple had hoped to appear in it together. Instead,  In 1943, at the behest of the Ministry of Information, Olivier began working on ''

In 1943, at the behest of the Ministry of Information, Olivier began working on ''

The triumvirate secured the New Theatre for their first season and recruited a company. Thorndike was joined by, among others,

The triumvirate secured the New Theatre for their first season and recruited a company. Thorndike was joined by, among others,

By the end of the Australian tour, both Leigh and Olivier were exhausted and ill, and he told a journalist, "You may not know it, but you are talking to a couple of walking corpses." Later he would comment that he "lost Vivien" in Australia, a reference to Leigh's affair with the Australian actor Peter Finch, whom the couple met during the tour. Shortly afterwards Finch moved to London, where Olivier auditioned him and put him under a long-term contract with Laurence Olivier Productions. Finch and Leigh's affair continued on and off for several years.

Although it was common knowledge that the Old Vic triumvirate had been dismissed, they refused to be drawn on the matter in public, and Olivier even arranged to play a final London season with the company in 1949, as Richard III, Sir Peter Teazle, and Chorus in his own production of

By the end of the Australian tour, both Leigh and Olivier were exhausted and ill, and he told a journalist, "You may not know it, but you are talking to a couple of walking corpses." Later he would comment that he "lost Vivien" in Australia, a reference to Leigh's affair with the Australian actor Peter Finch, whom the couple met during the tour. Shortly afterwards Finch moved to London, where Olivier auditioned him and put him under a long-term contract with Laurence Olivier Productions. Finch and Leigh's affair continued on and off for several years.

Although it was common knowledge that the Old Vic triumvirate had been dismissed, they refused to be drawn on the matter in public, and Olivier even arranged to play a final London season with the company in 1949, as Richard III, Sir Peter Teazle, and Chorus in his own production of

In their third production of the 1955 Stratford season, Olivier played the title role in ''

In their third production of the 1955 Stratford season, Olivier played the title role in ''

Osborne was already at work on a new play, '' The Entertainer'', an allegory of Britain's post-colonial decline, centred on a seedy

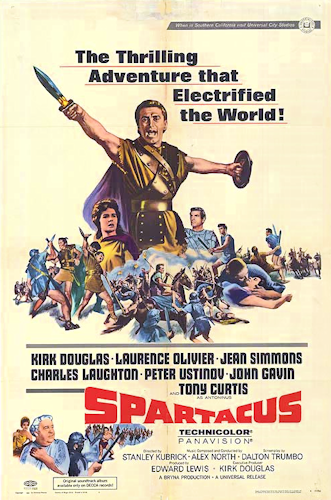

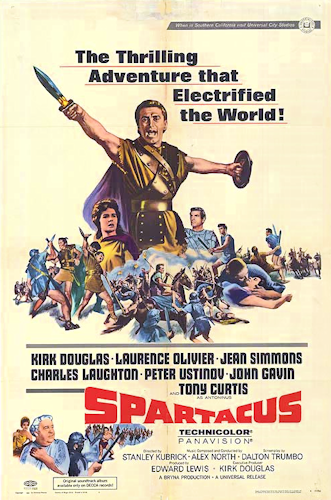

Osborne was already at work on a new play, '' The Entertainer'', an allegory of Britain's post-colonial decline, centred on a seedy  Two films featuring Olivier were released in 1960. The first—filmed in 1959—was ''

Two films featuring Olivier were released in 1960. The first—filmed in 1959—was ''

After this Olivier played three more stage roles: James Tyrone in

After this Olivier played three more stage roles: James Tyrone in

Tynan remarked to Olivier, "you aren't really a contemplative or philosophical actor"; Olivier was known for the strenuous physicality of his performances in some roles. He told Tynan this was because he was influenced as a young man by

Tynan remarked to Olivier, "you aren't really a contemplative or philosophical actor"; Olivier was known for the strenuous physicality of his performances in some roles. He told Tynan this was because he was influenced as a young man by

Laurence Olivier Archive

at the

John Gielgud

Sir Arthur John Gielgud, (; 14 April 1904 – 21 May 2000) was an English actor and theatre director whose career spanned eight decades. With Ralph Richardson and Laurence Olivier, he was one of the trinity of actors who dominated the Brit ...

, was one of a trio of male actors who dominated the British stage of the mid-20th century. He also worked in films throughout his career, playing more than fifty cinema roles. Late in his career, he had considerable success in television roles.

His family had no theatrical connections, but Olivier's father, a clergyman, decided that his son should become an actor. After attending a drama school in London, Olivier learned his craft in a succession of acting jobs during the late 1920s. In 1930 he had his first important West End success in Noël Coward's ''Private Lives

''Private Lives'' is a 1930 comedy of manners in three acts by Noël Coward. It concerns a divorced couple who, while honeymooning with their new spouses, discover that they are staying in adjacent rooms at the same hotel. Despite a perpetu ...

'', and he appeared in his first film. In 1935 he played in a celebrated production of ''Romeo and Juliet'' alongside Gielgud and Peggy Ashcroft

Dame Edith Margaret Emily Ashcroft (22 December 1907 – 14 June 1991), known professionally as Peggy Ashcroft, was an English actress whose career spanned more than 60 years.

Born to a comfortable middle-class family, Ashcroft was deter ...

, and by the end of the decade he was an established star. In the 1940s, together with Richardson and John Burrell, Olivier was the co-director of the Old Vic

The Old Vic is a 1,000-seat, not-for-profit producing theatre in Waterloo, London, England. Established in 1818 as the Royal Coburg Theatre, and renamed in 1833 the Royal Victoria Theatre. In 1871 it was rebuilt and reopened as the Royal ...

, building it into a highly respected company. There his most celebrated roles included Shakespeare's Richard III and Sophocles

Sophocles (; grc, Σοφοκλῆς, , Sophoklễs; 497/6 – winter 406/5 BC)Sommerstein (2002), p. 41. is one of three ancient Greek tragedians, at least one of whose plays has survived in full. His first plays were written later than, or c ...

's Oedipus. In the 1950s Olivier was an independent actor-manager, but his stage career was in the doldrums until he joined the ''avant-garde'' English Stage Company

The Royal Court Theatre, at different times known as the Court Theatre, the New Chelsea Theatre, and the Belgravia Theatre, is a non-commercial West End theatre in Sloane Square, in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, London, England ...

in 1957 to play the title role in '' The Entertainer'', a part he later played on film. From 1963 to 1973 he was the founding director of Britain's National Theatre, running a resident company that fostered many future stars. His own parts there included the title role in '' Othello'' (1965) and Shylock in ''The Merchant of Venice

''The Merchant of Venice'' is a play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1596 and 1598. A merchant in Venice named Antonio defaults on a large loan provided by a Jewish moneylender, Shylock.

Although classified as ...

'' (1970).

Among Olivier's films are ''Wuthering Heights

''Wuthering Heights'' is an 1847 novel by Emily Brontë, initially published under her pen name Ellis Bell. It concerns two families of the landed gentry living on the West Yorkshire moors, the Earnshaws and the Lintons, and their turbulent re ...

'' (1939), '' Rebecca'' (1940), and a trilogy of Shakespeare films as actor/director: ''Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (c. 1173–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (1 ...

'' (1944), ''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depicts ...

'' (1948), and '' Richard III'' (1955). His later films included ''Spartacus

Spartacus ( el, Σπάρτακος '; la, Spartacus; c. 103–71 BC) was a Thracian gladiator who, along with Crixus, Gannicus, Castus, and Oenomaus, was one of the escaped slave leaders in the Third Servile War, a major slave uprisin ...

'' (1960), '' The Shoes of the Fisherman'' (1968), ''Sleuth

Sleuth may refer to:

* Detective

*Sleuth, collective noun for a group of bears

Computing

* The Sleuth Kit, a collection of forensic analysis software

*SLEUTH assembler language for the UNIVAC 1107

Entertainment and media

*Cloo

Cloo (stylized ...

'' (1972), '' Marathon Man'' (1976), and '' The Boys from Brazil'' (1978). His television appearances included an adaptation of ''The Moon and Sixpence

''The Moon and Sixpence'' is a novel by W. Somerset Maugham, first published on 15 April 1919. It is told in episodic form by a first-person narrator providing a series of glimpses into the mind and soul of the central character, Charles Stric ...

'' (1960), '' Long Day's Journey into Night'' (1973), ''Love Among the Ruins Love Among the Ruins may refer to:

Literature

* "Love Among the Ruins" (poem), a poem by Robert Browning

* ''Love Among the Ruins. A Romance of the Near Future'', a novel by Evelyn Waugh

* ''Love Among the Ruins'', a novel by Warwick Deeping

* ''L ...

'' (1975), '' Cat on a Hot Tin Roof'' (1976), ''Brideshead Revisited

''Brideshead Revisited: The Sacred & Profane Memories of Captain Charles Ryder'' is a novel by English writer Evelyn Waugh, first published in 1945. It follows, from the 1920s to the early 1940s, the life and romances of the protagonist Charles ...

'' (1981) and ''King Lear

''King Lear'' is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare.

It is based on the mythological Leir of Britain. King Lear, in preparation for his old age, divides his power and land between two of his daughters. He becomes destitute and insane ...

'' (1983).

Olivier's honours included a knighthood

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the ...

(1947), a life peerage (1970), and the Order of Merit (1981). For his on-screen work he received four Academy Awards

The Academy Awards, better known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international film industry. The awards are regarded by many as the most prestigious, significant awards in the entertainment ind ...

, two British Academy Film Awards, five Emmy Awards, and three Golden Globe Awards. The National Theatre's largest auditorium is named in his honour, and he is commemorated in the Laurence Olivier Awards, given annually by the Society of London Theatre

The Society of London Theatre (SOLT) is an umbrella organisation for West End theatre in London. Founded in 1908, as Society of West End Theatre Managers, then Society of West End Theatre in 1975, changing to its current name in 1994, the (SOLT) ...

. He was married three times, to the actresses Jill Esmond

Jill Esmond (born Jill Esmond Moore; 26 January 1908 – 28 July 1990) was an English stage and screen actress. She was the first wife of Laurence Olivier.

Early life

Esmond was born in London, the daughter of stage actors Henry V. Esmond and ...

from 1930 to 1940, Vivien Leigh from 1940 to 1960, and Joan Plowright

Joan Ann Olivier, Baroness Olivier, (née Plowright; born 28 October 1929), professionally known as Dame Joan Plowright, is an English retired actress whose career has spanned over seven decades. She has won two Golden Globe Awards and a Tony ...

from 1961 until his death.

Life and career

Family background and early life (1907–1924)

Olivier was born in Dorking, Surrey, the youngest of the three children of the Reverend Gerard Kerr Olivier (1869–1939) and his wife Agnes Louise, ''née'' Crookenden (1871–1920). Their elder children were Sybille (1901–1989) and Gerard Dacres "Dickie" (1904–1958). His great-great-grandfather was of French

Olivier was born in Dorking, Surrey, the youngest of the three children of the Reverend Gerard Kerr Olivier (1869–1939) and his wife Agnes Louise, ''née'' Crookenden (1871–1920). Their elder children were Sybille (1901–1989) and Gerard Dacres "Dickie" (1904–1958). His great-great-grandfather was of French Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

descent, and Olivier came from a long line of Protestant clergymen. Gerard Olivier had begun a career as a schoolmaster, but in his thirties he discovered a strong religious vocation and was ordained as a priest of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

. He practised extremely high church

The term ''high church'' refers to beliefs and practices of Christian ecclesiology, liturgy, and theology that emphasize formality and resistance to modernisation. Although used in connection with various Christian traditions, the term originate ...

, ritualist

Ritualism, in the history of Christianity, refers to an emphasis on the rituals and liturgical ceremonies of the church. Specifically, the Christian ritual of Holy Communion.

In the Anglican church in the 19th century, the role of ritual became ...

Anglicanism and liked to be addressed as "Father Olivier". This made him unacceptable to most Anglican congregations, and the only church posts he was offered were temporary, usually deputising for regular incumbents

The incumbent is the current holder of an office or position, usually in relation to an election. In an election for president, the incumbent is the person holding or acting in the office of president before the election, whether seeking re-ele ...

in their absence. This meant a nomadic existence, and for Laurence's first few years, he never lived in one place long enough to make friends.

In 1912, when Olivier was five, his father secured a permanent appointment as assistant rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

at St Saviour's, Pimlico

St Saviour's is an Anglo-Catholic church in Pimlico, City of Westminster, London, England, located at the north end of St George's Square. It was constructed in the 1860s as part of Thomas Cubitt's development of the area on behalf of the Marqu ...

. He held the post for six years and a stable family life was at last possible. Olivier was devoted to his mother, but not to his father, whom he found a cold and remote parent. Nevertheless, he learned a great deal of the art of performing from him. As a young man Gerard Olivier had considered a stage career and was a dramatic and effective preacher. Olivier wrote that his father knew "when to drop the voice, when to bellow about the perils of hellfire, when to slip in a gag, when suddenly to wax sentimental ... The quick changes of mood and manner absorbed me, and I have never forgotten them."

In 1916, after attending a series of preparatory schools, Olivier passed the singing examination for admission to the choir school of

In 1916, after attending a series of preparatory schools, Olivier passed the singing examination for admission to the choir school of All Saints, Margaret Street

All Saints, Margaret Street, is a Grade I listed Anglo-Catholic church in London. The church was designed by the architect William Butterfield and built between 1850 and 1859. It has been hailed as Butterfield's masterpiece and a pioneering buil ...

, in central London. His elder brother was already a pupil and Olivier gradually settled in, though he felt himself to be something of an outsider. The church's style of worship was (and remains) Anglo-Catholic

Anglo-Catholicism comprises beliefs and practices that emphasise the Catholic heritage and identity of the various Anglican churches.

The term was coined in the early 19th century, although movements emphasising the Catholic nature of Anglica ...

, with emphasis on ritual, vestments and incense. The theatricality of the services appealed to Olivier, and the vicar encouraged the students to develop a taste for secular as well as religious drama. In a school production of ''Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, ...

'' in 1917, the ten-year-old Olivier's performance as Brutus impressed an audience that included Lady Tree

Helen Maud Holt (5 October 1863 – 7 August 1937), professionally known as Mrs Beerbohm Tree and later Lady Tree, was an English actress. She was the wife of the actor Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree and the mother of Viola Tree, Felicity Tree and Ir ...

, the young Sybil Thorndike, and Ellen Terry

Dame Alice Ellen Terry, (27 February 184721 July 1928), was a leading English actress of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Born into a family of actors, Terry began performing as a child, acting in Shakespeare plays in London, and tour ...

, who wrote in her diary, "The small boy who played Brutus is already a great actor." He later won praise in other schoolboy productions, as Maria in ''Twelfth Night

''Twelfth Night'', or ''What You Will'' is a romantic comedy by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written around 1601–1602 as a Twelfth Night's entertainment for the close of the Christmas season. The play centres on the twins Vi ...

'' (1918) and Katherine in ''The Taming of the Shrew

''The Taming of the Shrew'' is a comedy by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1590 and 1592. The play begins with a framing device, often referred to as the induction, in which a mischievous nobleman tricks a drunken ...

'' (1922).

From All Saints, Olivier went on to St Edward's School, Oxford

St Edward's School is a public school (English independent day and boarding school) in Oxford, England. It is known informally as 'Teddies'.

Approximately sixty pupils live in each of its thirteen houses. The school is a member of the Rugby G ...

, from 1921 to 1924. He made little mark until his final year, when he played Puck in the school's production of '' A Midsummer Night's Dream''; his performance was a tour de force that won him popularity among his fellow pupils. In January 1924, his brother left England to work in India as a rubber planter. Olivier missed him greatly and asked his father how soon he could follow. He recalled in his memoirs that his father replied, "Don't be such a fool, you're not going to India, you're going on the stage."

Early acting career (1924–1929)

In 1924 Gerard Olivier, a habitually frugal man, told his son that he must gain not only admission to theCentral School of Speech Training and Dramatic Art

The Royal Central School of Speech and Drama was founded by Elsie Fogerty in 1906, as The Central School of Speech Training and Dramatic Art, to offer a new form of training in speech and drama for young actors and other students. It became a ...

, but also a scholarship with a bursary to cover his tuition fees and living expenses. Olivier's sister had been a student there and was a favourite of Elsie Fogerty, the founder and principal of the school. Olivier later speculated that it was on the strength of this that Fogerty agreed to award him the bursary.

One of Olivier's contemporaries at the school was

One of Olivier's contemporaries at the school was Peggy Ashcroft

Dame Edith Margaret Emily Ashcroft (22 December 1907 – 14 June 1991), known professionally as Peggy Ashcroft, was an English actress whose career spanned more than 60 years.

Born to a comfortable middle-class family, Ashcroft was deter ...

, who observed he was "rather uncouth in that his sleeves were too short and his hair stood on end but he was intensely lively and great fun". By his own admission, he was not a very conscientious student, but Fogerty liked him and later said that he and Ashcroft stood out among her many pupils.

After leaving the Central School in 1925, Olivier worked for small theatrical companies. At his first stage appearance, in a sketch called ''The Unfailing Instinct'' at the Brighton Hippodrome

Brighton Hippodrome is an entertainment venue in the ancient centre of Brighton, part of the English city of Brighton and Hove. It has been empty and out of use since 2007, when its use as a Bingo (Commonwealth), bingo hall ceased.

From its const ...

in August 1925, he tripped on his entrance and fell flat on his face. Later that year, he was taken on by Sybil Thorndike (the daughter of a friend of Olivier's father) and her husband Lewis Casson

Sir Lewis Thomas Casson MC (26 October 187516 May 1969) was an English actor and theatre director, and the husband of actress Dame Sybil Thorndike.Devlin, DianaCasson, Sir Lewis Thomas (1875–1969) ''The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography ...

as a bit-part player, understudy, and assistant stage manager for their London company. Olivier modelled his performing style on that of Gerald du Maurier

Sir Gerald Hubert Edward Busson du Maurier (26 March 1873 – 11 April 1934) was an English actor and manager. He was the son of author George du Maurier and his wife, Emma Wightwick, and the brother of Sylvia Llewelyn Davies. In 1903, he ...

, of whom he said, "He seemed to mutter on stage but had such perfect technique. When I started I was so busy doing a du Maurier that no one ever heard a word I said. The Shakespearean actors one saw were terrible hams like Frank Benson." Olivier's concern with speaking naturally and avoiding what he called "singing" Shakespeare's verse was the cause of much frustration in his early career, as critics regularly decried his delivery.

In 1926, on Thorndike's recommendation, Olivier joined the Birmingham Repertory Company

Birmingham Repertory Theatre, commonly called Birmingham Rep or just The Rep, is a producing theatre based on Centenary Square in Birmingham, England. Founded by Barry Jackson, it is the longest-established of Britain's building-based theatre c ...

. His biographer Michael Billington describes the Birmingham company as "Olivier's university", where in his second year he was given the chance to play a wide range of important roles, including Tony Lumpkin in ''She Stoops to Conquer

''She Stoops to Conquer'' is a comedy by Oliver Goldsmith, first performed in London in 1773. The play is a favourite for study by English literature and theatre classes in the English-speaking world. It is one of the few plays from the 18t ...

'', the title role in ''Uncle Vanya

''Uncle Vanya'' ( rus, Дя́дя Ва́ня, r=Dyádya Ványa, p=ˈdʲædʲə ˈvanʲə) is a play by the Russian playwright Anton Chekhov. It was first published in 1898, and was first produced in 1899 by the Moscow Art Theatre under the dir ...

'', and Parolles in '' All's Well That Ends Well''. Billington adds that the engagement led to "a lifelong friendship with his fellow actor Ralph Richardson that was to have a decisive effect on the British theatre."

While playing the juvenile lead in ''Bird in Hand'' at the Royalty Theatre

The Royalty Theatre was a small London theatre situated at 73 Dean Street, Soho. Established by the actress Frances Maria Kelly in 1840, it opened as Miss Kelly's Theatre and Dramatic School and finally closed to the public in 1938.

in June 1928, Olivier began a relationship with Jill Esmond

Jill Esmond (born Jill Esmond Moore; 26 January 1908 – 28 July 1990) was an English stage and screen actress. She was the first wife of Laurence Olivier.

Early life

Esmond was born in London, the daughter of stage actors Henry V. Esmond and ...

, the daughter of the actors Henry V. Esmond and Eva Moore

Eva Moore (9 February 1868 – 27 April 1955) was an English actress. Her career on stage and in film spanned six decades, and she was active in the women's suffrage movement. In her 1923 book of reminiscences, ''Exits and Entrances'', she des ...

. Olivier later recounted that he thought "she would most certainly do excellent well for a wife ... I wasn't likely to do any better at my age and with my undistinguished track-record, so I promptly fell in love with her."

In 1928 Olivier created the role of Stanhope in R. C. Sherriff's ''Journey's End

''Journey's End'' is a 1928 dramatic play by English playwright R. C. Sherriff, set in the trenches near Saint-Quentin, Aisne, towards the end of the First World War. The story plays out in the officers' dugout of a British Army infantry c ...

'', in which he scored a great success at its single Sunday night premiere. He was offered the part in the West End production the following year, but turned it down in favour of the more glamorous role of Beau Geste

''Beau Geste'' is an adventure novel by British writer P. C. Wren, which details the adventures of three English brothers who enlist separately in the French Foreign Legion following the theft of a valuable jewel from the country house of a rel ...

in a stage adaptation of P. C. Wren

Percival Christopher Wren (1 November 187522 November 1941) was an English writer, mostly of adventure fiction. He is remembered best for ''Beau Geste'', a much-filmed book of 1924, involving the French Foreign Legion in North Africa. This was ...

's 1929 novel of the same name. ''Journey's End'' became a long-running success; ''Beau Geste'' failed. ''The Manchester Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' commented, "Mr. Laurence Olivier did his best as Beau, but he deserves and will get better parts. Mr. Olivier is going to make a big name for himself". For the rest of 1929 Olivier appeared in seven plays, all of which were short-lived. Billington ascribes this failure rate to poor choices by Olivier rather than mere bad luck.

Rising star (1930–1935)

In 1930, with his impending marriage in mind, Olivier earned some extra money with small roles in two films. In April he travelled to Berlin to film the English-language version of '' The Temporary Widow'', a crime comedy withLilian Harvey

Lilian Harvey (born Helene Lilian Muriel Pape; 19 January 1906 – 27 July 1968) was an Anglo-German actress and singer, long based in Germany, where she is best known for her role as Christel Weinzinger in Erik Charell's 1931 film ''Der Kongr ...

, and in May he spent four nights working on another comedy, '' Too Many Crooks''. During work on the latter film, for which he was paid £60, he met Laurence Evans, who became his personal manager. Olivier did not enjoy working in film, which he dismissed as "this anaemic little medium which could not stand great acting", but financially it was much more rewarding than his theatre work.

Olivier and Esmond married on 25 July 1930 at All Saints, Margaret Street, although within weeks both realised they had erred. Olivier later recorded that the marriage was "a pretty crass mistake. I insisted on getting married from a pathetic mixture of religious and animal promptings. ... She had admitted to me that she was in love elsewhere and could never love me as completely as I would wish". Olivier later recounted that following the wedding he did not keep a diary for ten years and never followed religious practices again, although he considered those facts to be "mere coincidence", unconnected to the nuptials.

In 1930 Noël Coward cast Olivier as Victor Prynne in his new play ''Private Lives

''Private Lives'' is a 1930 comedy of manners in three acts by Noël Coward. It concerns a divorced couple who, while honeymooning with their new spouses, discover that they are staying in adjacent rooms at the same hotel. Despite a perpetu ...

'', which opened at the new Phoenix Theatre in London in September. Coward and Gertrude Lawrence

Gertrude Lawrence (4 July 1898 – 6 September 1952) was an English actress, singer, dancer and musical comedy performer known for her stage appearances in the West End of London and on Broadway in New York.

Early life

Lawrence was born Gertr ...

played the lead roles, Elyot Chase and Amanda Prynne. Victor is a secondary character, along with Sybil Chase; the author called them "extra puppets, lightly wooden ninepins, only to be repeatedly knocked down and stood up again". To make them credible spouses for Amanda and Elyot, Coward was determined that two outstandingly attractive performers should play the parts. Olivier played Victor in the West End and then on Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

**Broadway Theatre (53rd Stree ...

; Adrianne Allen

Adrianne Allen (7 February 1907 – 14 September 1993) was an English stage actress.

Most often seen in light comedy, Allen played Sybil Chase in the original West End production of ''Private Lives'' and Elizabeth Bennet in the 1935 Broadw ...

was Sybil in London, but could not go to New York, where the part was taken by Esmond. In addition to giving the 23-year-old Olivier his first successful West End role, Coward became something of a mentor. In the late 1960s Olivier told Sheridan Morley

Sheridan Morley (5 December 1941 − 16 February 2007) was an English author, biographer, critic and broadcaster. He was the official biographer of Sir John Gielgud and wrote biographies of many other theatrical figures he had known, includin ...

:

In 1931 RKO Pictures offered Olivier a two-film contract at $1,000 a week; he discussed the possibility with Coward, who, irked, told Olivier "You've no artistic integrity, that's your trouble; this is how you cheapen yourself." He accepted and moved to Hollywood, despite some misgivings. His first film was the drama '' Friends and Lovers'', in a supporting role, before RKO loaned him to

In 1931 RKO Pictures offered Olivier a two-film contract at $1,000 a week; he discussed the possibility with Coward, who, irked, told Olivier "You've no artistic integrity, that's your trouble; this is how you cheapen yourself." He accepted and moved to Hollywood, despite some misgivings. His first film was the drama '' Friends and Lovers'', in a supporting role, before RKO loaned him to Fox Studios

20th Century Studios, Inc. (previously known as 20th Century Fox) is an American film production company headquartered at the Fox Studio Lot in the Century City area of Los Angeles. As of 2019, it serves as a film production arm of Walt Dis ...

for his first film lead, a British journalist in a Russia under martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

in ''The Yellow Ticket

''The Yellow Ticket'' is a 1931 pre-Code American drama film based on the 1914 play of the same name by Michael Morton, produced by the Fox Film Corporation, directed by Raoul Walsh, and starring Elissa Landi, Lionel Barrymore and Laurence ...

'', alongside Elissa Landi

Elissa Landi (born Elisabeth Marie Christine Kühnelt; December 6, 1904 – October 21, 1948) was an Austrian-American actress born in Venice, who was popular as a performer in Hollywood films of the 1920s and 1930s. She was noted for her a ...

and Lionel Barrymore. The cultural historian Jeffrey Richards

Jeffrey Richards (born c.1945)Chris Arno"Fast Forward: Jeffrey Richards" ''The Guardian'', 11 January 2005 is a British historian.

Educated at Jesus College, Cambridge, he is Professor of Cultural History at Lancaster University. A leading cul ...

describes Olivier's look as an attempt by Fox Studios to produce a likeness of Ronald Colman, and Colman's moustache, voice and manner are "perfectly reproduced". Olivier returned to RKO to complete his contract with the 1932 drama ''Westward Passage

''Westward Passage'' is a 1932 American pre-Code drama film directed by Robert Milton and starring Ann Harding, Laurence Olivier, ZaSu Pitts and Irving Pichel. The screenplay concerns a woman who falls in love and marries, but soon discovers ho ...

'', which was a commercial failure. Olivier's initial foray into American films had not provided the breakthrough he hoped for; disillusioned with Hollywood, he returned to London, where he appeared in two British films, '' Perfect Understanding'' with Gloria Swanson

Gloria May Josephine Swanson (March 27, 1899April 4, 1983) was an American actress and producer. She first achieved fame acting in dozens of silent films in the 1920s and was nominated three times for the Academy Award for Best Actress, most f ...

and ''No Funny Business

''No Funny Business'' is a 1933 British comedy film directed by Victor Hanbury and starring Laurence Olivier, Gertrude Lawrence, Jill Esmond and Edmund Breon. The film is a comedy of errors set in a divorce case. It was made at Ealing Studios. ...

''—in which Esmond also appeared. He was tempted back to Hollywood in 1933 to appear opposite Greta Garbo

Greta Garbo (born Greta Lovisa Gustafsson; 18 September 1905 – 15 April 1990) was a Swedish-American actress. Regarded as one of the greatest screen actresses, she was known for her melancholic, somber persona, her film portrayals of tragic ch ...

in '' Queen Christina'', but was replaced after two weeks of filming because of a lack of chemistry between the two.

Olivier's stage roles in 1934 included Bothwell in Gordon Daviot

Josephine Tey was a pseudonym used by Elizabeth MacKintosh (25 July 1896 – 13 February 1952), a Scottish author. Her novel ''The Daughter of Time'' was a detective work investigating the role of Richard III of England in the death of the Prin ...

's ''Queen of Scots'', which was only a moderate success for him and for the play, but led to an important engagement for the same management (Bronson Albery

Sir Bronson James Albery (6 March 1881 – 21 July 1971) was an English theatre director and impresario. Second son of James Albery and Mary Moore, and brother to Irving Albery and Wyndham Albery, he was knighted in 1949 for his services to th ...

) shortly afterwards. In the interim he had a great success playing a thinly disguised version of the American actor John Barrymore

John Barrymore (born John Sidney Blyth; February 14 or 15, 1882 – May 29, 1942) was an American actor on stage, screen and radio. A member of the Drew and Barrymore theatrical families, he initially tried to avoid the stage, and briefly att ...

in George S. Kaufman and Edna Ferber

Edna Ferber (August 15, 1885 – April 16, 1968) was an American novelist, short story writer and playwright. Her novels include the Pulitzer Prize-winning '' So Big'' (1924), ''Show Boat'' (1926; made into the celebrated 1927 musical), '' Ci ...

's '' Theatre Royal''. His success was vitiated by his breaking an ankle two months into the run, in one of the athletic, acrobatic stunts with which he liked to enliven his performances.

In 1935, under Albery's management, John Gielgud

Sir Arthur John Gielgud, (; 14 April 1904 – 21 May 2000) was an English actor and theatre director whose career spanned eight decades. With Ralph Richardson and Laurence Olivier, he was one of the trinity of actors who dominated the Brit ...

staged ''Romeo and Juliet'' at the New Theatre, co-starring with Peggy Ashcroft, Edith Evans, and Olivier. Gielgud had seen Olivier in ''Queen of Scots'', spotted his potential, and gave him a major step up in his career. For the first weeks of the run Gielgud played Mercutio

Mercutio ( , ) is a fictional character in William Shakespeare's 1597 tragedy, ''Romeo and Juliet''. He is a close friend to Romeo and a blood relative to Prince Escalus and Count Paris. As such, Mercutio is one of the named characters in the ...

and Olivier played Romeo

Romeo Montague () is the male protagonist of William Shakespeare's tragedy ''Romeo and Juliet''. The son of Lord Montague and his wife, Lady Montague, he secretly loves and marries Juliet, a member of the rival House of Capulet, through a priest ...

, after which they exchanged roles. The production broke all box-office records for the play, running for 189 performances. Olivier was enraged at the notices after the first night, which praised the virility of his performance but fiercely criticised his speaking of Shakespeare's verse, contrasting it with his co-star's mastery of the poetry. The friendship between the two men was prickly, on Olivier's side, for the rest of his life.

Old Vic and Vivien Leigh (1936–1938)

In May 1936 Olivier and Richardson jointly directed and starred in a new piece by J. B. Priestley, '' Bees on the Boatdeck''. Both actors won excellent notices, but the play, an allegory of Britain's decay, did not attract the public and closed after four weeks. Later in the same year Olivier accepted an invitation to jointhe Old Vic

The Old Vic is a 1,000-seat, not-for-profit producing theatre in Waterloo, London, England. Established in 1818 as the Royal Coburg Theatre, and renamed in 1833 the Royal Victoria Theatre. In 1871 it was rebuilt and reopened as the Royal ...

company. The theatre, in an unfashionable location south of the Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

, had offered inexpensive tickets for opera and drama under its proprietor Lilian Baylis

Lilian Mary Baylis

CH (9 May 187425 November 1937) was an English theatrical producer and manager. She managed the Old Vic and Sadler's Wells theatres in London and ran an opera company, which became the English National Opera (ENO); a theatre ...

since 1912. Her drama company specialised in the plays of Shakespeare and many leading actors had taken very large cuts in their pay to develop their Shakespearean techniques there. Gielgud had been in the company from 1929 to 1931 and Richardson from 1930 to 1932. Among the actors whom Olivier joined in late 1936 were Edith Evans, Ruth Gordon

Ruth Gordon Jones (October 30, 1896 – August 28, 1985) was an American actress, screenwriter, and playwright. She began her career performing on Broadway at age 19. Known for her nasal voice and distinctive personality, Gordon gained internati ...

, Alec Guinness and Michael Redgrave

Sir Michael Scudamore Redgrave CBE (20 March 1908 – 21 March 1985) was an English stage and film actor, director, manager and author. He received a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance in ''Mourning Becomes Elec ...

. In January 1937 Olivier took the title role in an uncut version of ''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depicts ...

'', in which once again his delivery of the verse was unfavourably compared with that of Gielgud, who had played the role on the same stage seven years previously to enormous acclaim. ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the ...

''s Ivor Brown

Ivor John Carnegie Brown CBE (25 April 1891 – 22 April 1974) was a British journalist and man of letters.

Biography

Born in Penang, Malaya, Brown was the younger of two sons of Dr. William Carnegie Brown, a specialist in tropical diseases ...

praised Olivier's "magnetism and muscularity" but missed "the kind of pathos so richly established by Mr Gielgud". The reviewer in ''The Times'' found the performance "full of vitality", but at times "too light ... the character slips from Mr Olivier's grasp".

Tyrone Guthrie

Sir William Tyrone Guthrie (2 July 1900 – 15 May 1971) was an English theatrical director instrumental in the founding of the Stratford Festival of Canada, the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and the Tyrone Guthrie Centre at h ...

, summed up as "a baddish, immature production of mine, with Olivier outrageously amusing as Sir Toby and a very young Alec Guinness outrageous and more amusing as Sir Andrew". ''Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (c. 1173–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (1 ...

'' was the next play, presented in May to mark the Coronation of George VI. A pacifist, as he then was, Olivier was as reluctant to play the warrior king as Guthrie was to direct the piece, but the production was a success and Baylis had to extend the run from four to eight weeks.

Following Olivier's success in Shakespearean stage productions, he made his first foray into Shakespeare on film in 1936, as Orlando

Orlando () is a city in the U.S. state of Florida and is the county seat of Orange County. In Central Florida, it is the center of the Orlando metropolitan area, which had a population of 2,509,831, according to U.S. Census Bureau figures re ...

in '' As You Like It'', directed by Paul Czinner, "a charming if lightweight production", according to Michael Brooke of the British Film Institute

The British Film Institute (BFI) is a film and television charitable organisation which promotes and preserves film-making and television in the United Kingdom. The BFI uses funds provided by the National Lottery (United Kingdom), National Lot ...

's (BFI's) Screenonline

Screenonline is a website about the history of British film, television and social history as documented by film and television. The project has been developed by the British Film Institute and funded by a £1.2 million grant from the National Lo ...

. The following year Olivier appeared alongside Vivien Leigh in the historical drama ''Fire Over England

''Fire Over England'' is a 1937 London Film Productions film drama, notable for providing the first pairing of Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh. It was directed by William K. Howard and written by Clemence Dane from the 1936 novel '' Fire ...

''. He had first met Leigh briefly at the Savoy Grill and then again when she visited him during the run of ''Romeo and Juliet'', probably early in 1936, and the two had begun an affair sometime that year. Of the relationship, Olivier later said that "I couldn't help myself with Vivien. No man could. I hated myself for cheating on Jill, but then I had cheated before, but this was something different. This wasn't just out of lust. This was love that I really didn't ask for but was drawn into." While his relationship with Leigh continued he conducted an affair with the actress Ann Todd, and possibly had a brief affair with the actor Henry Ainley, according to the biographer Michael Munn.

In June 1937 the Old Vic company took up an invitation to perform ''Hamlet'' in the courtyard of the castle at Elsinore, where Shakespeare located the play. Olivier secured the casting of Leigh to replace Cherry Cottrell as Ophelia

Ophelia () is a character in William Shakespeare's drama '' Hamlet'' (1599–1601). She is a young noblewoman of Denmark, the daughter of Polonius, sister of Laertes and potential wife of Prince Hamlet, who, due to Hamlet's actions, ends u ...

. Because of torrential rain the performance had to be moved from the castle courtyard to the ballroom of a local hotel, but the tradition of playing Hamlet at Elsinore was established, and Olivier was followed by, among others, Gielgud (1939), Redgrave (1950), Richard Burton

Richard Burton (; born Richard Walter Jenkins Jr.; 10 November 1925 – 5 August 1984) was a Welsh actor. Noted for his baritone voice, Burton established himself as a formidable Shakespearean actor in the 1950s, and he gave a memorable pe ...

(1954), Christopher Plummer

Arthur Christopher Orme Plummer (December 13, 1929 – February 5, 2021) was a Canadian actor. His career spanned seven decades, gaining him recognition for his performances in film, stage, and television. He received multiple accolades, inc ...

(1964), Derek Jacobi

Sir Derek George Jacobi (; born 22 October 1938) is an English actor. He has appeared in various stage productions of William Shakespeare such as ''Hamlet'', ''Much Ado About Nothing'', '' Macbeth'', ''Twelfth Night'', '' The Tempest'', ''Kin ...

(1979), Kenneth Branagh

Sir Kenneth Charles Branagh (; born 10 December 1960) is a British actor and filmmaker. Branagh trained at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London and has served as its president since 2015. He has won an Academy Award, four BAFTAs (plus ...

(1988) and Jude Law (2009). Back in London, the company staged '' Macbeth'', with Olivier in the title role. The stylised production by Michel Saint-Denis

Michel Jacques Saint-Denis (13 September 1897 – 31 July 1971), ''dit'' Jacques Duchesne, was a French actor, theatre director, and drama theorist whose ideas on actor training have had a profound influence on the development of European th ...

was not well liked, but Olivier had some good notices among the bad. On returning from Denmark, Olivier and Leigh told their respective spouses about the affair and that their marriages were over; Esmond moved out of the marital house and in with her mother. After Olivier and Leigh made a tour of Europe in mid-1937 they returned to separate film projects—'' A Yank at Oxford'' for her and ''The Divorce of Lady X

''The Divorce of Lady X'' is a 1938 British Technicolor romantic comedy film produced by London Films; it stars Merle Oberon, Laurence Olivier, Ralph Richardson and Binnie Barnes. It was directed by Tim Whelan and produced by Alexander Kord ...

'' for him—and moved into a property together in Iver

Iver is a large civil parish in Buckinghamshire, England. In addition to the central clustered village, the parish includes the residential neighbourhoods of Iver Heath and Richings Park.

Geography, transport and economy

Part of the 43-square- ...

, Buckinghamshire.

Olivier returned to the Old Vic for a second season in 1938. For '' Othello'' he played Iago

Iago () is a fictional character in Shakespeare's ''Othello'' (c. 1601–1604). Iago is the play's main antagonist, and Othello's standard-bearer. He is the husband of Emilia, who is in turn the attendant of Othello's wife Desdemona. Iago ha ...

, with Richardson in the title role. Guthrie wanted to experiment with the theory that Iago's villainy is driven by a suppressed love for Othello. Olivier was willing to co-operate, but Richardson was not; audiences and most critics failed to spot the supposed motivation of Olivier's Iago, and Richardson's Othello seemed underpowered. After that comparative failure, the company had a success with ''Coriolanus

''Coriolanus'' ( or ) is a tragedy by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1605 and 1608. The play is based on the life of the legendary Roman leader Caius Marcius Coriolanus. Shakespeare worked on it during the same yea ...

'' starring Olivier in the title role. The notices were laudatory, mentioning him alongside great predecessors such as Edmund Kean

Edmund Kean (4 November 178715 May 1833) was a celebrated British Shakespearean stage actor born in England, who performed, among other places, in London, Belfast, New York, Quebec, and Paris. He was known for his short stature, tumultuo ...

, William Macready

William Charles Macready (3 March 179327 April 1873) was an English actor.

Life

He was born in London the son of William Macready the elder, and actress Christina Ann Birch. Educated at Rugby School where he became headboy, and where now the t ...

, and Henry Irving

Sir Henry Irving (6 February 1838 – 13 October 1905), christened John Henry Brodribb, sometimes known as J. H. Irving, was an English stage actor in the Victorian era, known as an actor-manager because he took complete responsibility ( ...

. The actor Robert Speaight

Robert William Speaight (; 1904 – 1976) was a British actor and writer, and the brother of George Speaight, the puppeteer.

Speaight studied under Elsie Fogerty at the Central School of Speech and Drama, then based in the Royal Albert Hal ...

described it as "Olivier's first incontestably great performance". This was Olivier's last appearance on a London stage for six years.

Hollywood and the Second World War (1938–1944)

In 1938 Olivier joined Richardson to film the spy thriller ''

In 1938 Olivier joined Richardson to film the spy thriller ''Q Planes

''Q Planes'' (known as ''Clouds Over Europe'' in the United States) is a 1939 British comedy spy film starring Ralph Richardson, Laurence Olivier and Valerie Hobson. Olivier and Richardson were a decade into their fifty-year friendship and were ...

'', released the following year. Frank Nugent

Frank Stanley Nugent (May 27, 1908 – December 29, 1965) was an American screenwriter, journalist, and film reviewer, who wrote 21 film scripts, 11 for director John Ford. He wrote almost a thousand reviews for ''The New York Times'' before lea ...

, the critic for ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'', thought Olivier was "not quite so good" as Richardson, but was "quite acceptable". In late 1938, lured by a salary of $50,000, the actor travelled to Hollywood to take the part of Heathcliff in the 1939 film ''Wuthering Heights

''Wuthering Heights'' is an 1847 novel by Emily Brontë, initially published under her pen name Ellis Bell. It concerns two families of the landed gentry living on the West Yorkshire moors, the Earnshaws and the Lintons, and their turbulent re ...

'', alongside Merle Oberon

Merle Oberon (born Estelle Merle O'Brien Thompson; 19 February 191123 November 1979) was a British actress who began her film career in British films as Anne Boleyn in ''The Private Life of Henry VIII'' (1933). After her success in ''The Scarle ...

and David Niven

James David Graham Niven (; 1 March 1910 – 29 July 1983) was a British actor, soldier, memoirist, and novelist. He won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance as Major Pollock in '' Separate Tables'' (1958). Niven's other roles ...

. In less than a month Leigh had joined him, explaining that her trip was "partially because Larry's there and partially because I intend to get the part of Scarlett O'Hara

Katie Scarlett O'Hara Hamilton Kennedy Butler is a fictional character and the protagonist in Margaret Mitchell's 1936 novel ''Gone with the Wind'' and in the 1939 film of the same name, where she is portrayed by Vivien Leigh. She also is the ...

"—the role in ''Gone with the Wind

Gone with the Wind most often refers to:

* ''Gone with the Wind'' (novel), a 1936 novel by Margaret Mitchell

* ''Gone with the Wind'' (film), the 1939 adaptation of the novel

Gone with the Wind may also refer to:

Music

* ''Gone with the Wind'' ...

'' in which she was eventually cast. Olivier did not enjoy making ''Wuthering Heights'', and his approach to film acting, combined with a dislike for Oberon, led to tensions on set. The director, William Wyler

William Wyler (; born Willi Wyler (); July 1, 1902 – July 27, 1981) was a Swiss-German-American film director and producer who won the Academy Award for Best Director three times, those being for '' Mrs. Miniver'' (1942), ''The Best Years of ...

, was a hard taskmaster, and Olivier learned to remove what Billington described as "the carapace of theatricality" to which he was prone, replacing it with "a palpable reality". The resulting film was a commercial and critical success that earned him a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actor and created his screen reputation. Caroline Lejeune, writing for ''The Observer'', considered that "Olivier's dark, moody face, abrupt style, and a certain fine arrogance towards the world in his playing are just right" in the role, while the reviewer for ''The Times'' wrote that Olivier "is a good embodiment of Heathcliff ... impressive enough on a more human plane, speaking his lines with real distinction, and always both romantic and alive."

Joan Fontaine

Joan de Beauvoir de Havilland (October 22, 1917 – December 15, 2013), known professionally as Joan Fontaine, was a British-American actress who is best known for her starring roles in Hollywood films during the "Golden Age". Fontaine appeared ...

was selected for the role of Mrs de Winter, as the producer David O. Selznick thought that not only was she more suitable for the role, but that it was best to keep Olivier and Leigh apart until their divorces came through. Olivier followed ''Rebecca'' with '' Pride and Prejudice'', in the role of Mr. Darcy

Fitzwilliam Darcy Esquire, generally referred to as Mr. Darcy, is one of the two central characters in Jane Austen's 1813 novel '' Pride and Prejudice''. He is an archetype of the aloof romantic hero, and a romantic interest of Elizabeth Benn ...

. To his disappointment Elizabeth Bennet

Elizabeth Bennet is the protagonist in the 1813 novel ''Pride and Prejudice'' by Jane Austen. She is often referred to as Eliza or Lizzy by her friends and family. Elizabeth is the second child in a family of five daughters. Though the circu ...

was played by Greer Garson

Eileen Evelyn Greer Garson (29 September 1904 – 6 April 1996) was an English-American actress and singer. She was a major star at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer who became popular during the Second World War for her portrayal of strong women on the hom ...

rather than Leigh. He received good reviews for both films and showed a more confident screen presence than he had in his early work. In January 1940 Olivier and Esmond were granted their divorce. In February, following another request from Leigh, her husband also applied for their marriage to be terminated.

On stage, Olivier and Leigh starred in ''Romeo and Juliet'' on Broadway. It was an extravagant production, but a commercial failure. In ''The New York Times'' Brooks Atkinson

Justin Brooks Atkinson (November 28, 1894 – January 14, 1984) was an American theatre critic. He worked for '' The New York Times'' from 1922 to 1960. In his obituary, the ''Times'' called him "the theater's most influential reviewer of hi ...

praised the scenery but not the acting: "Although Miss Leigh and Mr Olivier are handsome young people they hardly act their parts at all." The couple had invested almost all their savings in the project, and its failure was a grave financial blow. They were married in August 1940, at the San Ysidro Ranch in Santa Barbara.

The war in Europe had been under way for a year and was going badly for Britain. After his wedding Olivier wanted to help the war effort. He telephoned Duff Cooper

Alfred Duff Cooper, 1st Viscount Norwich, (22 February 1890 – 1 January 1954), known as Duff Cooper, was a British Conservative Party politician and diplomat who was also a military and political historian.

First elected to Parliament in 19 ...

, the Minister of Information

An information minister (also called minister of information) is a position in the governments of some countries responsible for dealing with information matters; it is often linked with censorship and propaganda. Sometimes the position is given to ...

under Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, hoping to get a position in Cooper's department. Cooper advised him to remain where he was and speak to the film director Alexander Korda

Sir Alexander Korda (; born Sándor László Kellner; hu, Korda Sándor; 16 September 1893 – 23 January 1956)That Hamilton Woman

''That Hamilton Woman'', also known as ''Lady Hamilton'', is a 1941 black-and-white historical film drama produced and directed by Alexander Korda for his British company during his exile in the United States. Set during the Napoleonic Wars, th ...

'', with Olivier as Horatio Nelson and Leigh in the title role

The title character in a narrative work is one who is named or referred to in the title of the work. In a performed work such as a play or film, the performer who plays the title character is said to have the title role of the piece. The title of ...

. Korda saw that the relationship between the couple was strained. Olivier was tiring of Leigh's suffocating adulation, and she was drinking to excess. The film, in which the threat of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

paralleled that of Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

, was seen by critics as "bad history but good British propaganda", according to the BFI.

Olivier's life was under threat from the Nazis and pro-German sympathisers. The studio owners were concerned enough that Samuel Goldwyn

Samuel Goldwyn (born Szmuel Gelbfisz; yi, שמואל געלבפֿיש; August 27, 1882 (claimed) January 31, 1974), also known as Samuel Goldfish, was a Polish-born American film producer. He was best known for being the founding contributor an ...

and Cecil B. DeMille

Cecil Blount DeMille (; August 12, 1881January 21, 1959) was an American film director, producer and actor. Between 1914 and 1958, he made 70 features, both silent and sound films. He is acknowledged as a founding father of the American cine ...

both provided support and security to ensure his safety. On the completion of filming, Olivier and Leigh returned to Britain. He had spent the previous year learning to fly and had completed nearly 250 hours by the time he left America. He intended to join the Royal Air Force but instead made another propaganda film, '' 49th Parallel'', narrated short pieces for the Ministry of Information, and joined the Fleet Air Arm

The Fleet Air Arm (FAA) is one of the five fighting arms of the Royal Navy and is responsible for the delivery of naval air power both from land and at sea. The Fleet Air Arm operates the F-35 Lightning II for maritime strike, the AW159 Wil ...

because Richardson was already in the service. Richardson had gained a reputation for crashing aircraft, which Olivier rapidly eclipsed. Olivier and Leigh settled in a cottage just outside RNAS Worthy Down

RAF Worthy Down was a Royal Air Force station built in 1918, north of Winchester, Hampshire, England. After it was transferred to Royal Navy control in 1939 as RNAS Worthy Down (HMS Kestrel), the airfield remained in use throughout the Second Wo ...

, where he was stationed with a training squadron; Noël Coward visited the couple and thought Olivier looked unhappy. Olivier spent much of his time taking part in broadcasts and making speeches to build morale, and in 1942 he was invited to make another propaganda film, ''The Demi-Paradise

''The Demi-Paradise'' (also known as ''Adventure for Two'') is a 1943 British comedy film made by Two Cities Films. It stars Laurence Olivier as a Soviet Russian inventor who travels to England to have his revolutionary propeller manufactured, a ...

'', in which he played a Soviet engineer who helps improve British-Russian relationships.

In 1943, at the behest of the Ministry of Information, Olivier began working on ''

In 1943, at the behest of the Ministry of Information, Olivier began working on ''Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (c. 1173–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (1 ...

''. Originally he had no intention of taking the directorial duties, but ended up directing and producing, in addition to taking the title role. He was assisted by an Italian internee, Filippo Del Giudice

Filippo Del Giudice, (26 March 1892 – 1 January 1963), born in Trani, Apulia, Trani, Italy, was an Italian film producer. Giudice was a lawyer, legal advisor and film producer. He worked with people that were already well known in their field ...

, who had been released to produce propaganda for the Allied cause. The decision was made to film the battle scenes in neutral Ireland, where it was easier to find the 650 extras. John Betjeman, the press attaché at the British embassy in Dublin, played a key liaison role with the Irish government in making suitable arrangements. The film was released in November 1944. Brooke, writing for the BFI, considers that it "came too late in the Second World War to be a call to arms as such, but formed a powerful reminder of what Britain was defending." The music for the film was written by William Walton

Sir William Turner Walton (29 March 19028 March 1983) was an English composer. During a sixty-year career, he wrote music in several classical genres and styles, from film scores to opera. His best-known works include ''Façade'', the cantat ...

, "a score that ranks with the best in film music", according to the music critic Michael Kennedy. Walton also provided the music for Olivier's next two Shakespearean adaptations, ''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depicts ...

'' (1948) and '' Richard III'' (1955). ''Henry V'' was warmly received by critics. The reviewer for ''The Manchester Guardian'' wrote that the film combined "new art hand-in-hand with old genius, and both superbly of one mind", in a film that worked "triumphantly". The critic for ''The Times'' considered that Olivier "plays Henry on a high, heroic note and never is there danger of a crack", in a film described as "a triumph of film craft". There were Oscar nominations for the film, including Best Picture and Best Actor, but it won none and Olivier was instead presented with a "Special Award". He was unimpressed, and later commented that "this was my first absolute fob-off, and I regarded it as such."

Co-directing the Old Vic (1944–1948)

Throughout the war Tyrone Guthrie had striven to keep the Old Vic company going, even after German bombing in 1942 left the theatre a near-ruin. A small troupe toured the provinces, with Sybil Thorndike at its head. By 1944, with the tide of the war turning, Guthrie felt it time to re-establish the company in a London base and invited Richardson to head it. Richardson made it a condition of accepting that he should share the acting and management in a triumvirate. Initially he proposed Gielgud and Olivier as his colleagues, but the former declined, saying, "It would be a disaster, you would have to spend your whole time as referee between Larry and me." It was finally agreed that the third member would be the stage director John Burrell. The Old Vic governors approached the Royal Navy to secure the release of Richardson and Olivier; the Sea Lords consented, with, as Olivier put it, "a speediness and lack of reluctance which was positively hurtful."Harcourt Williams

Ernest George Harcourt Williams (30 March 1880 – 13 December 1957) was an English actor and director. After early experience in touring companies he established himself as a character actor and director in the West End. From 1929 to 1934 he ...

, Joyce Redman

Joyce Olivia Redman (7 December 1915Jonathan Croall, "Redman, Joyce Olivia (1915–2012)", ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, Jan 201available online Retrieved 1 April 2020. – 9 May 2012) was an Anglo-Irish a ...

and Margaret Leighton

Margaret Leighton, CBE (26 February 1922 – 13 January 1976) was an English actress, active on stage and television, and in film. Her film appearances included (her first credited debut feature) in Anatole de Grunwald's ''The Winslow Boy'' ( ...

. It was agreed to open with a repertory of four plays: '' Peer Gynt'', '' Arms and the Man'', '' Richard III'' and ''Uncle Vanya''. Olivier's roles were the Button Moulder, Sergius, Richard and Astrov; Richardson played Peer, Bluntschli, Richmond and Vanya. The first three productions met with acclaim from reviewers and audiences; ''Uncle Vanya'' had a mixed reception, although ''The Times'' thought Olivier's Astrov "a most distinguished portrait" and Richardson's Vanya "the perfect compound of absurdity and pathos". In ''Richard III'', according to Billington, Olivier's triumph was absolute: "so much so that it became his most frequently imitated performance and one whose supremacy went unchallenged until Antony Sher

Sir Antony Sher (14 June 1949 – 2 December 2021) was a British actor, writer and theatre director of South African origin. A two-time Laurence Olivier Award winner and a four-time nominee, he joined the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1982 a ...

played the role forty years later". In 1945 the company toured Germany, where they were seen by many thousands of Allied servicemen; they also appeared at the Comédie-Française

The Comédie-Française () or Théâtre-Français () is one of the few state theatres in France. Founded in 1680, it is the oldest active theatre company in the world. Established as a French state-controlled entity in 1995, it is the only state ...

theatre in Paris, the first foreign company to be given that honour. The critic Harold Hobson

Sir Harold Hobson CBE, (4 August 1904 – 12 March 1992) was an English drama critic and author.

Early life and education

Hobson was born in Thorpe Hesley near Rotherham then in the West Riding of Yorkshire, England. He attended Sheffield Gramm ...

wrote that Richardson and Olivier quickly "made the Old Vic the most famous theatre in the Anglo-Saxon world."

The second season, in 1945, featured two double bills. The first consisted of ''Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2''. Olivier played the warrior Hotspur in the first and the doddering Justice Shallow in the second. He received good notices, but by general consent the production belonged to Richardson as Falstaff

Sir John Falstaff is a fictional character who appears in three plays by William Shakespeare and is eulogised in a fourth. His significance as a fully developed character is primarily formed in the plays '' Henry IV, Part 1'' and '' Part 2'', w ...

. In the second double bill it was Olivier who dominated, in the title roles of '' Oedipus Rex'' and ''The Critic

''The Critic'' was an American primetime adult animated sitcom revolving around the life of New York film critic Jay Sherman, voiced by Jon Lovitz. It was created by writing partners Al Jean and Mike Reiss, who had previously worked as writers a ...

''. In the two one-act plays his switch from searing tragedy and horror in the first half to farcical comedy in the second impressed most critics and audience members, though a minority felt that the transformation from Sophocles

Sophocles (; grc, Σοφοκλῆς, , Sophoklễs; 497/6 – winter 406/5 BC)Sommerstein (2002), p. 41. is one of three ancient Greek tragedians, at least one of whose plays has survived in full. His first plays were written later than, or c ...

's bloodily blinded hero to Sheridan's vain and ludicrous Mr Puff "smacked of a quick-change turn in a music hall". After the London season the company played both the double bills and ''Uncle Vanya'' in a six-week run on Broadway.

The third, and final, London season under the triumvirate was in 1946–47. Olivier played King Lear, and Richardson took the title role in ''Cyrano de Bergerac

Savinien de Cyrano de Bergerac ( , ; 6 March 1619 – 28 July 1655) was a French novelist, playwright, epistolarian, and duelist.

A bold and innovative author, his work was part of the libertine literature of the first half of the 17th cen ...

''. Olivier would have preferred the roles to be reversed, but Richardson did not wish to attempt Lear. Olivier's Lear received good but not outstanding reviews. In his scenes of decline and madness towards the end of the play some critics found him less moving than his finest predecessors in the role. The influential critic James Agate

James Evershed Agate (9 September 1877 – 6 June 1947) was an English diarist and theatre critic between the two world wars. He took up journalism in his late twenties and was on the staff of ''The Manchester Guardian'' in 1907–1914. He later ...

suggested that Olivier used his dazzling stage technique to disguise a lack of feeling, a charge that the actor strongly rejected, but which was often made throughout his later career. During the run of ''Cyrano'', Richardson was knighted, to Olivier's undisguised envy. The younger man received the accolade six months later, by which time the days of the triumvirate were numbered. The high profile of the two star actors did not endear them to the new chairman of the Old Vic governors, Lord Esher

Viscount Esher, of Esher in the County of Surrey, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created on 11 November 1897 for the prominent lawyer and judge William Brett, 1st Baron Esher, upon his retirement as Master of the Rolls ...

. He had ambitions to be the first head of the National Theatre and had no intention of letting actors run it. He was encouraged by Guthrie, who, having instigated the appointment of Richardson and Olivier, had come to resent their knighthoods and international fame.

In January 1947 Olivier began working on his second film as a director, ''Hamlet'' (1948), in which he also took the lead role. The original play was heavily cut to focus on the relationships, rather than the political intrigue. The film became a critical and commercial success in Britain and abroad, although Lejeune, in ''The Observer'', considered it "less effective than livier'sstage work. ... He speaks the lines nobly, and with the caress of one who loves them, but he nullifies his own thesis by never, for a moment, leaving the impression of a man who cannot make up his own mind; here, you feel rather, is an actor-producer-director who, in every circumstance, knows exactly what he wants, and gets it". Campbell Dixon, the critic for ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was f ...

'' thought the film "brilliant ... one of the masterpieces of the stage has been made into one of the greatest of films." ''Hamlet'' became the first non-American film to win the Academy Award for Best Picture, while Olivier won the Award for Best Actor.

In 1948 Olivier led the Old Vic company on a six-month tour of Australia and New Zealand. He played Richard III, Sir Peter Teazle in Sheridan's'' The School for Scandal

''The School for Scandal'' is a comedy of manners written by Richard Brinsley Sheridan. It was first performed in London at Drury Lane Theatre on 8 May 1777.

Plot

Act I

Scene I: Lady Sneerwell, a wealthy young widow, and her hireling Sn ...

'' and Antrobus in Thornton Wilder

Thornton Niven Wilder (April 17, 1897 – December 7, 1975) was an American playwright and novelist. He won three Pulitzer Prizes — for the novel '' The Bridge of San Luis Rey'' and for the plays ''Our Town'' and '' The Skin of Our Teeth'' — ...

's ''The Skin of Our Teeth

''The Skin of Our Teeth'' is a play by Thornton Wilder that won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. It opened on October 15, 1942, at the Shubert Theatre in New Haven, Connecticut, before moving to the Plymouth Theatre on Broadway on November 18, ...

'', appearing alongside Leigh in the latter two plays. While Olivier was on the Australian tour and Richardson was in Hollywood, Esher terminated the contracts of the three directors, who were said to have "resigned". Melvyn Bragg in a 1984 study of Olivier, and John Miller in the authorised biography of Richardson, both comment that Esher's action put back the establishment of a National Theatre for at least a decade. Looking back in 1971, Bernard Levin

Henry Bernard Levin (19 August 1928 – 7 August 2004) was an English journalist, author and broadcaster, described by ''The Times'' as "the most famous journalist of his day". The son of a poor Jewish family in London, he won a scholarship t ...

wrote that the Old Vic company of 1944 to 1948 "was probably the most illustrious that has ever been assembled in this country". ''The Times'' said that the triumvirate's years were the greatest in the Old Vic's history; as ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' put it, "the governors summarily sacked them in the interests of a more mediocre company spirit".

Post-war (1948–1951)

By the end of the Australian tour, both Leigh and Olivier were exhausted and ill, and he told a journalist, "You may not know it, but you are talking to a couple of walking corpses." Later he would comment that he "lost Vivien" in Australia, a reference to Leigh's affair with the Australian actor Peter Finch, whom the couple met during the tour. Shortly afterwards Finch moved to London, where Olivier auditioned him and put him under a long-term contract with Laurence Olivier Productions. Finch and Leigh's affair continued on and off for several years.