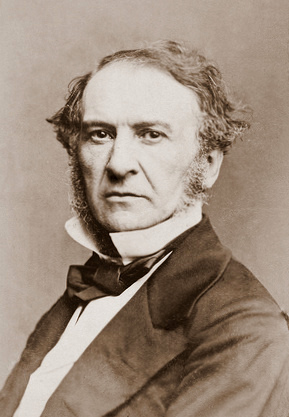

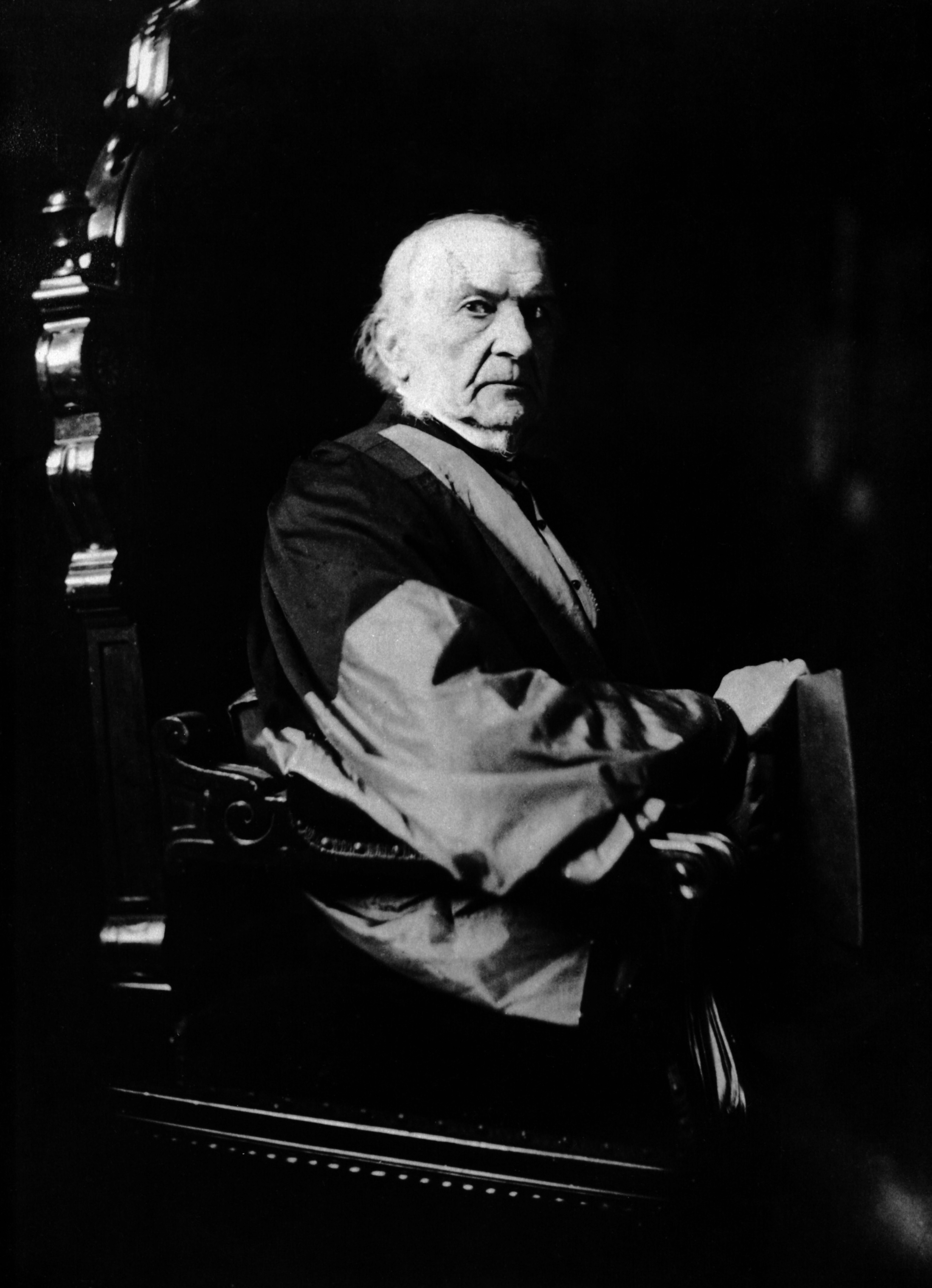

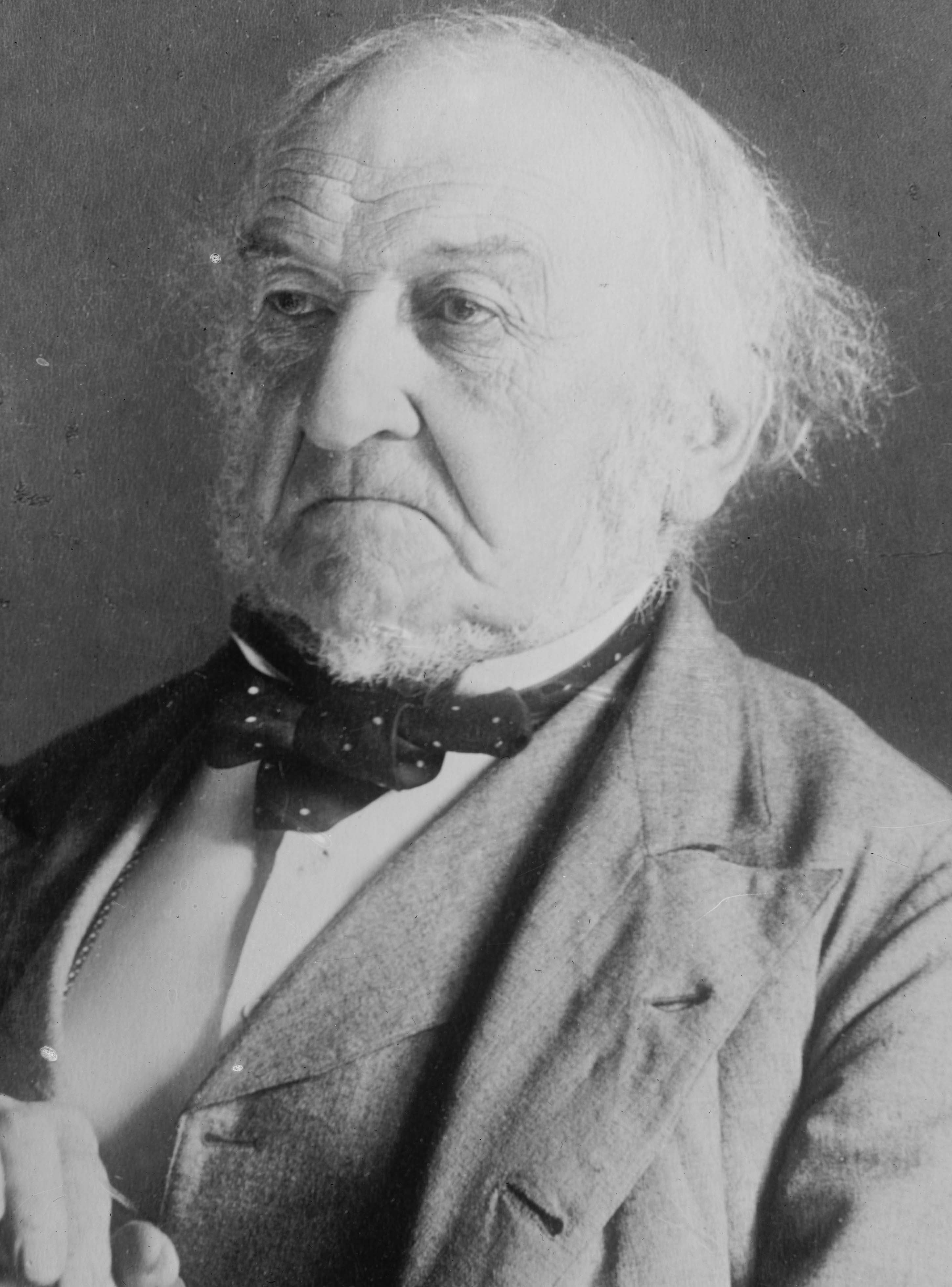

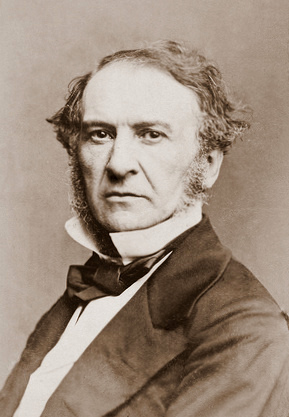

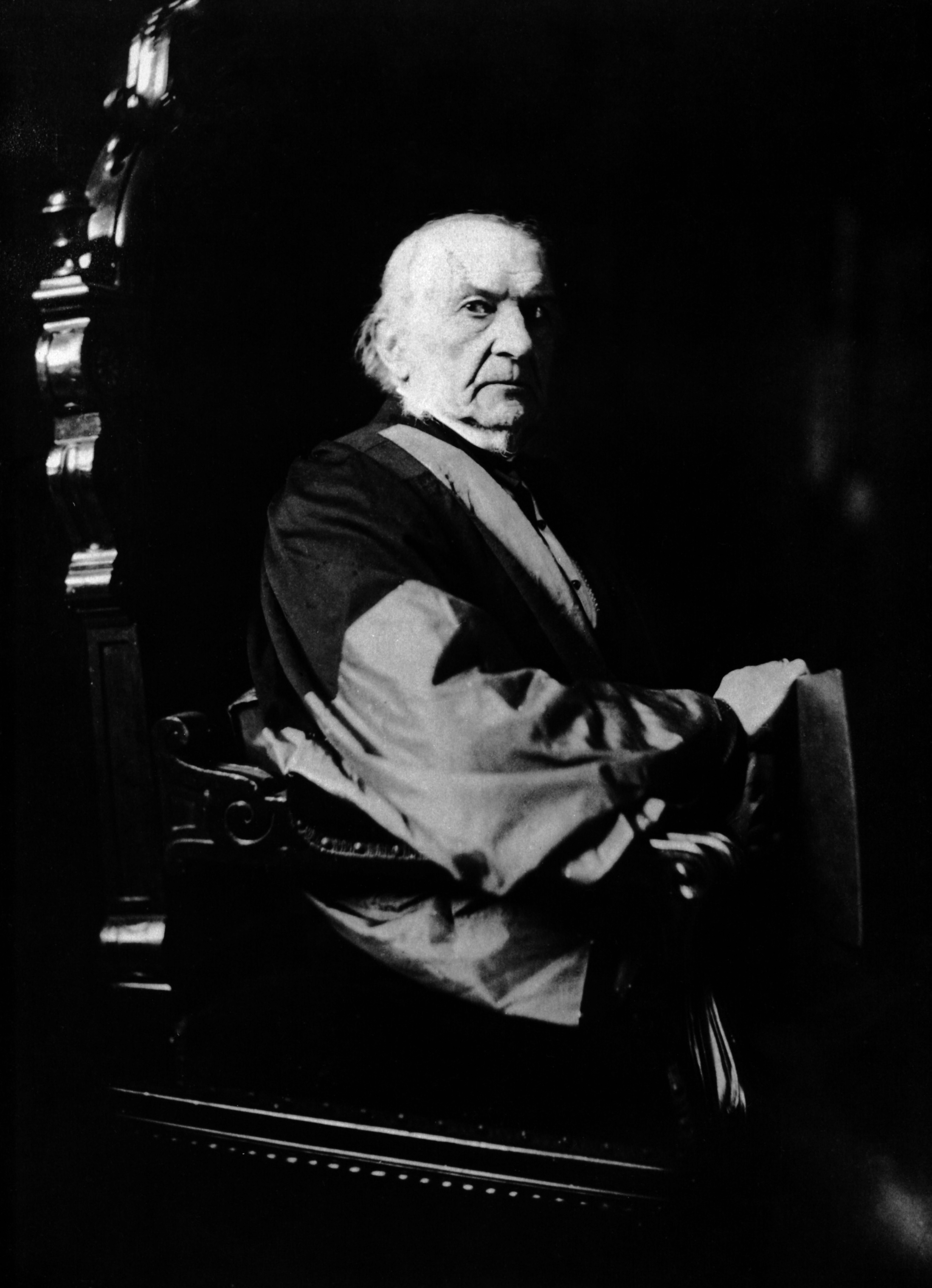

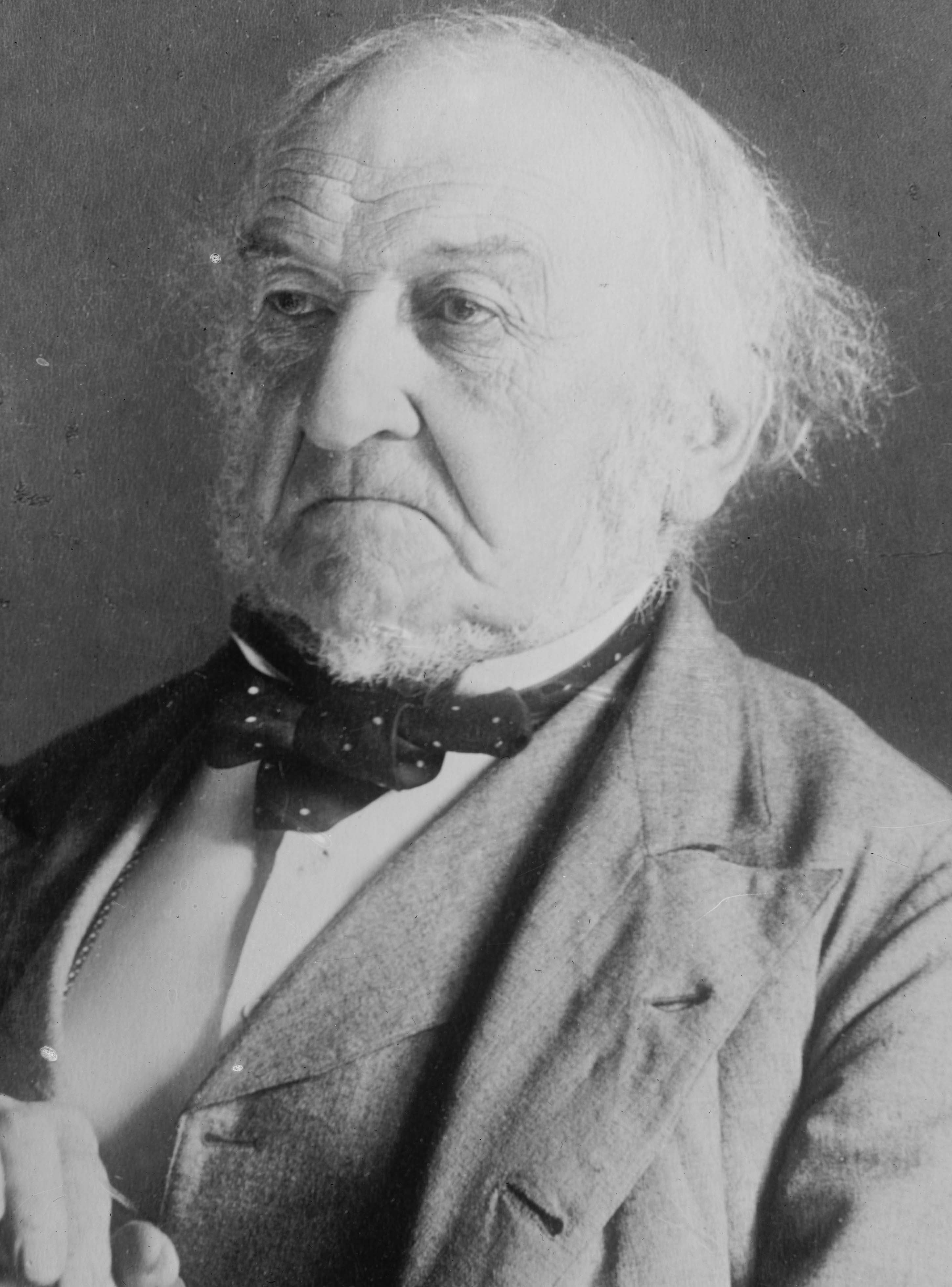

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and

Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern ...

, spread over four non-consecutive terms (the most of any British prime minister) beginning in 1868 and ending in 1894. He also served as

Chancellor of the Exchequer four times, serving over 12 years.

Gladstone was born in

Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a populat ...

to Scottish parents. He first entered the

House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

in 1832, beginning his political career as a

High Tory

In the United Kingdom and elsewhere, High Toryism is the old traditionalist conservatism which is in line with the Toryism originating in the 17th century. High Tories and their worldview are sometimes at odds with the modernising elements of the ...

, a grouping which became the

Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

under

Robert Peel in 1834. Gladstone served as a minister in both of Peel's governments, and in 1846 joined the breakaway

Peelite faction, which eventually merged into the new

Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

in 1859. He was chancellor under

Lord Aberdeen

George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen, (28 January 178414 December 1860), styled Lord Haddo from 1791 to 1801, was a British statesman, diplomat and landowner, successively a Tory, Conservative and Peelite politician and specialist in ...

(1852–1855),

Lord Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, (20 October 1784 – 18 October 1865) was a British statesman who was twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in the mid-19th century. Palmerston dominated British foreign policy during the period ...

(1859–1865) and

Lord Russell (1865–1866). Gladstone's own political doctrine—which emphasised

equality of opportunity

Equal opportunity is a state of fairness in which individuals are treated similarly, unhampered by artificial barriers, prejudices, or preferences, except when particular distinctions can be explicitly justified. The intent is that the important ...

and opposition to trade

protectionism

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulatio ...

—came to be known as

Gladstonian liberalism. His popularity amongst the

working-class earned him the sobriquet "The People's William".

In 1868, Gladstone became prime minister for the first time. Many reforms were passed during his first ministry, including the disestablishment of the

Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the secon ...

and the introduction of

secret voting. After electoral defeat in

1874, Gladstone resigned as leader of the Liberal Party. From 1876 he began a comeback based on opposition to the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

's reaction to the

Bulgarian April Uprising. His

Midlothian Campaign

The Midlothian campaign of 1878–80 was a series of foreign policy speeches given by William Gladstone, leader of Britain's Liberal Party. It is often cited as the first modern political campaign. It also set the stage for Gladstone's comeback ...

of 1879–1880 was an early example of many modern political campaigning techniques.

After the

1880 general election, Gladstone formed his second ministry (1880–1885), which saw the passage of the

Third Reform Act

In the United Kingdom under the premiership of William Gladstone, the Representation of the People Act 1884 (48 & 49 Vict. c. 3, also known informally as the Third Reform Act) and the Redistribution Act of the following year were laws which ...

as well as crises in Egypt (culminating in the

Fall of Khartoum) and Ireland, where his government passed repressive measures but also improved the legal rights of Irish tenant farmers.

Back in office in early 1886, Gladstone proposed

home rule for Ireland

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the e ...

but was defeated in the House of Commons. The resulting split in the Liberal Party helped keep them out of office—with one short break—for 20 years. Gladstone formed his last government in

1892

Events

January–March

* January 1 – Ellis Island begins accommodating immigrants to the United States.

* February 1 - The historic Enterprise Bar and Grill was established in Rico, Colorado.

* February 27 – Rudolf Diesel applies fo ...

, at the age of 82. The

Government of Ireland Bill 1893

The Government of Ireland Bill 1893 (known generally as the Second Home Rule Bill) was the second attempt made by Liberal Party leader William Ewart Gladstone, as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, to enact a system of home rule for Ireland. ...

passed through the Commons but was defeated in the

House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminste ...

in 1893, after which Irish Home Rule became a lesser part of his party's agenda. Gladstone left office in March 1894, aged 84, as both the oldest person to serve as Prime Minister and the only prime minister to have served four non-consecutive terms. He left Parliament in

1895

Events

January–March

* January 5 – Dreyfus affair: French officer Alfred Dreyfus is stripped of his army rank, and sentenced to life imprisonment on Devil's Island.

* January 12 – The National Trust for Places of Histor ...

and died three years later.

Gladstone was known affectionately by his supporters as "The People's William" or the "G.O.M." ("Grand Old Man", or, to political rivals "God's Only Mistake"). Historians often call him one of Britain's greatest leaders.

Early life

Born in 1809 in

Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a populat ...

, at 62

Rodney Street, William Ewart Gladstone was the fourth son of the wealthy slaveowner

John Gladstone, and his second wife, Anne MacKenzie Robertson.

He was named after a close friend of his father, William Ewart, another Liverpool merchant and the father of

William Ewart, later a Liberal politician. In 1835, the family name was changed from Gladstones to Gladstone by royal licence. His father was made a

baronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14t ...

, of Fasque and Balfour, in 1846.

Although born and raised in Liverpool, William Gladstone was of purely

Scottish ancestry.

[Shannon, 1985] His grandfather

Thomas Gladstones

Thomas Gladstones (3 June 1732 – 12 May 1809) was a Scottish flour merchant and philanthropist. He was the father of Sir John Gladstone and the grandfather of the British prime minister William Ewart Gladstone.

Early life

Born at the farm of ...

(1732–1809) was a prominent merchant from

Leith

Leith (; gd, Lìte) is a port area in the north of the city of Edinburgh, Scotland, founded at the mouth of the Water of Leith. In 2021, it was ranked by ''Time Out'' as one of the top five neighbourhoods to live in the world.

The earliest ...

, and his maternal grandfather, Andrew Robertson, was Provost of Dingwall and a Sheriff-Substitute of

Ross-shire

Ross-shire (; gd, Siorrachd Rois) is a historic county in the Scottish Highlands. The county borders Sutherland to the north and Inverness-shire to the south, as well as having a complex border with Cromartyshire – a county consisting o ...

.

His biographer

John Morley

John Morley, 1st Viscount Morley of Blackburn, (24 December 1838 – 23 September 1923) was a British Liberal statesman, writer and newspaper editor.

Initially, a journalist in the North of England and then editor of the newly Liberal-leani ...

described him as "a highlander in the custody of a lowlander", and an adversary as "an ardent Italian in the custody of a Scotsman". One of his earliest childhood memories was being made to stand on a table and say "Ladies and gentlemen" to the assembled audience, probably at a gathering to promote the election of

George Canning as MP for Liverpool in 1812. In 1814, young "Willy" visited

Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

for the first time, as he and his brother

John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

travelled with their father to

Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian on the southern shore of t ...

,

Biggar and

Dingwall

Dingwall ( sco, Dingwal, gd, Inbhir Pheofharain ) is a town and a royal burgh in the Highland council area of Scotland. It has a population of 5,491. It was an east-coast harbour that now lies inland. Dingwall Castle was once the biggest cas ...

to visit their relatives. Willy and his brother were both made

freemen of the burgh of Dingwall. In 1815, Gladstone also travelled to

London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

and

Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a College town, university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cam ...

for the first time with his parents. Whilst in London, he attended a service of thanksgiving with his family at

St Paul's Cathedral following the

Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo, Belgium, Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by two of the armie ...

, where he saw the

Prince Regent

A prince regent or princess regent is a prince or princess who, due to their position in the line of succession, rules a monarchy as regent in the stead of a monarch regnant, e.g., as a result of the sovereign's incapacity (minority or illness ...

.

William Gladstone was educated from 1816 to 1821 at a

preparatory school at the vicarage of St. Thomas' Church at

Seaforth, close to his family's residence,

Seaforth House

Seaforth House was a mansion in Seaforth, Merseyside England built in 1813 for Sir John Gladstone, father of William Ewart Gladstone who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom four times.

Sir John had lived on Rodney Street, Liverpool and de ...

.

In 1821, William followed in the footsteps of his elder brothers and attended

Eton College

Eton College () is a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. intended as a sister institution to King's College, ...

before

matriculating

Matriculation is the formal process of entering a university, or of becoming eligible to enter by fulfilling certain academic requirements such as a matriculation examination.

Australia

In Australia, the term "matriculation" is seldom used now. ...

in 1828 at

Christ Church, Oxford, where he read

Classics and

Mathematics, although he had no great interest in the latter subject. In December 1831, he achieved the

double first-class degree he had long desired. Gladstone served as President of the

Oxford Union

The Oxford Union Society, commonly referred to simply as the Oxford Union, is a debating society in the city of Oxford England, whose membership is drawn primarily from the University of Oxford. Founded in 1823, it is one of Britain's oldest ...

, where he developed a reputation as an orator, which followed him into the

House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

. At university, Gladstone was a

Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

and denounced

Whig proposals for parliamentary reform.

Following the success of his double first, William travelled with his brother

John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

on a

Grand Tour

The Grand Tour was the principally 17th- to early 19th-century custom of a traditional trip through Europe, with Italy as a key destination, undertaken by upper-class young European men of sufficient means and rank (typically accompanied by a tut ...

of western Europe.

Although Gladstone entered

Lincoln's Inn in 1833, with intentions of becoming a

barrister, by 1839 he had requested that his name should be removed from the list because he no longer intended to be called to

the Bar.

In September 1842 he lost the

forefinger

The index finger (also referred to as forefinger, first finger, second finger, pointer finger, trigger finger, digitus secundus, digitus II, and many other terms) is the second digit of a human hand. It is located between the thumb and the mid ...

of his left hand in an accident while reloading a gun. Thereafter he wore a glove or finger sheath (stall).

House of Commons

First term

When Gladstone was 22 the

Duke of Newcastle

Duke of Newcastle upon Tyne was a title that was created three times, once in the Peerage of England and twice in the Peerage of Great Britain. The first grant of the title was made in 1665 to William Cavendish, 1st Marquess of Newcastle ...

, a Conservative party activist, provided him with one of two seats at

Newark

Newark most commonly refers to:

* Newark, New Jersey, city in the United States

* Newark Liberty International Airport, New Jersey; a major air hub in the New York metropolitan area

Newark may also refer to:

Places Canada

* Niagara-on-the ...

where he controlled about a fourth of the very small electorate. The Duke spent thousands of pounds entertaining the voters. Gladstone displayed remarkably strong technique as a campaigner and stump speaker. He won his seat at the

1832 United Kingdom general election with 887 votes. Initially a disciple of

High Toryism

In the United Kingdom and elsewhere, High Toryism is the old traditionalist conservatism which is in line with the Toryism originating in the 17th century. High Tories and their worldview are sometimes at odds with the modernising elements of the ...

, Gladstone's maiden speech as a young

Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

was a defence of the rights of West Indian sugar plantation magnates—slave-owners—among whom his father was prominent. He immediately came under attack from anti-slavery elements. He also surprised the duke by urging the need to increase pay for unskilled factory workers.; After new bills to protect child workers were proposed following the publication of the

Sadler report

:''This is an article about a 19th century British report. It should not be confused with the Sadler Commission, an investigation into Indian University education at the end of the First World War.''

The Sadler Report, also known as the Report of ...

, he voted against the 1833

Factory Acts that would regulate the hours of work and welfare of minors employed in cotton mills.

Attitude towards slavery

Gladstone's early attitude towards slavery was highly shaped by his father,

Sir John Gladstone, one of the largest slave owners in the British Empire. Gladstone wanted gradual rather than immediate emancipation, and proposed that slaves should serve a period of apprenticeship after being freed. They also opposed the international slave trade (which lowered the value of the slaves the father already owned). The antislavery movement demanded the immediate abolition of slavery. Gladstone opposed this and said in 1832 that emancipation should come after moral emancipation through the adoption of an education and the inculcation of "honest and industrious habits" among the slaves. Then "with the utmost speed that prudence will permit, we shall arrive at that exceedingly desired consummation, the utter extinction of slavery." In 1831, when the Oxford Union considered a motion in favour of the immediate emancipation of the slaves in the West Indies, Gladstone moved an amendment in favour of gradual manumission along with better protection for the personal and civil rights of the slaves and better provision for their Christian education. His early Parliamentary speeches followed a similar line: in June 1833, Gladstone concluded his speech on the ‘slavery question’ by declaring that though he had dwelt on "the dark side" of the issue, he looked forward to "a safe and gradual emancipation".

In 1834, when slavery was abolished across the British Empire, the owners were paid full value for the slaves. Gladstone helped his father obtain £106,769 in official reimbursement by the government for the 2,508 slaves he owned across nine plantations in the Caribbean.

In later years Gladstone's attitude towards slavery became more critical as his father's influence over his politics diminished. In 1844 Gladstone broke with his father when, as

President of the Board of Trade, he advanced proposals to halve duties on foreign sugar not produced by slave labour, in order to "secure the effectual exclusion of slave-grown sugar" and to encourage Brazil and Spain to end slavery. Sir John Gladstone, who opposed any reduction in duties on foreign sugar, wrote a letter to ''The Times'' criticizing the measure. Looking back late in life, Gladstone named the abolition of slavery as one of ten great achievements of the previous sixty years where the masses had been right and the upper classes had been wrong.

[''The Times'' (29 June 1886), p. 11.]

Opposition to the opium trade

Gladstone was an intense opponent of the

opium trade

Opium (or poppy tears, scientific name: ''Lachryma papaveris'') is dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy ''Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which i ...

.

Referring to the opium trade between

British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

and

Qing China, Gladstone described it as "infamous and atrocious".

Gladstone emerged as a fierce critic of the

Opium Wars

The Opium Wars () were two conflicts waged between China and Western powers during the mid-19th century. The First Opium War was fought from 1839 to 1842 between China and the United Kingdom, and was triggered by the Chinese government's c ...

, which Britain waged to re-legalise the British opium trade into China, which had been made illegal by the Chinese government.

He publicly lambasted the wars as "

Palmerston's Opium War" and said that he felt "in dread of the judgements of God upon England for our national iniquity towards China" in May 1840.

A famous speech was made by Gladstone in Parliament against the

First Opium War.

Gladstone criticised it as "a war more unjust in its origin, a war more calculated in its progress to cover this country with permanent disgrace".

His hostility to opium stemmed from the effects of opium upon his sister Helen.

Before 1841, Gladstone was reluctant to join the Peel government because of the First Opium War, which Palmerston had brought on.

Minister under Peel (1841–1846)

Gladstone was re-elected in 1841. In the second ministry of Robert Peel, he served as

President of the Board of Trade (1843–1845).

Gladstone was responsible for the

Railways Act 1844, regarded by historians as the birth of the

regulatory state, of network industry regulation, of rate of return regulation, and telegraph regulation. Examples of its foresight are the clauses empowering government to take control of railway in time of war, the concept of

Parliamentary train

A parliamentary train was a passenger service operated in the United Kingdom to comply with the Railway Regulation Act 1844 that required train companies to provide inexpensive and basic rail transport for less affluent passengers. The act req ...

s, limited in cost to a penny a mile, of universal service, and of control of the recently invented electric telegraph which ran alongside railway lines. Railways were the largest investment (as a percentage of GNP) in human history and this Bill the most heavily lobbied in Parliamentary history. Gladstone succeeded in guiding the Act through Parliament at the height of the

railway bubble.

Gladstone became concerned with the situation of "coal whippers". These were the men who worked on London docks, "whipping" in baskets from ships to barges or wharves all incoming coal from the sea. They were called up and relieved through public houses, so a man could not get this job unless he had the favourable opinion of the publican, who looked most favourably upon those who drank. The man's name was written down and the "score" followed. Publicans issued employment solely on the capacity of the man to pay, and men were often drunk when they left the pub to work. They spent their savings on drink to secure the favourable opinion of publicans and further employment.

Gladstone initiated the Coal Vendors Act 1843, which set up a central office for employment. When that Act expired in 1856, a Select Committee was appointed by the Lords in 1857 to look into the question. Gladstone gave evidence to the committee, stating: "I approached the subject in the first instance as I think everyone in Parliament of necessity did, with the strongest possible prejudice against the proposal

o interfere

O, or o, is the fifteenth letter and the fourth vowel letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''o'' (pronounced ), pl ...

but the facts stated were of so extraordinary and deplorable a character, that it was impossible to withhold attention from them. Then the question being whether legislative interference was required I was at length induced to look at a remedy of an extraordinary character as the only one I thought applicable to the case ... it was a great innovation". Looking back in 1883, Gladstone wrote that "In principle, perhaps my Coalwhippers Act of 1843 was the most Socialistic measure of the last half century".

He resigned in 1845 over the

Maynooth Grant

The Maynooth Grant was a cash grant from the British government to a Catholic seminary in Ireland. In 1845, the Conservative Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel, sought to improve the relationship between Catholic Ireland and Protestant Britain by in ...

issue, which was a matter of conscience for him. To improve relations with the Catholic Church, Peel's government proposed increasing the annual grant paid to the

Maynooth Seminary for training Catholic priests in Ireland. Gladstone, who had previously argued in a book that a Protestant country should not pay money to other churches, nevertheless supported the increase in the Maynooth grant and voted for it in Commons, but resigned rather than face charges that he had compromised his principles to remain in office. After accepting Gladstone's resignation, Peel confessed to a friend, "I really have great difficulty sometimes in exactly comprehending what he means". In December 1845, Gladstone returned to Peel's government as

Colonial Secretary. The ''

Dictionary of National Biography'' notes: "As such, he had to stand for re-election, but the strong protectionism of the Duke of Newcastle, his patron in Newark, meant that he could not stand there and no other seat was available. Throughout the corn law crisis of 1846, therefore, Gladstone was in the highly anomalous and possibly unique position of being a secretary of state without a seat in either house and thus unanswerable to parliament."

Return to the backbenches (1846–1851)

When Peel's government fell in 1846, Gladstone and other Peel loyalists followed their leader in separating from the protectionist Conservatives; instead offering tentative support to the new Whig prime minister

Lord John Russell

John Russell, 1st Earl Russell, (18 August 1792 – 28 May 1878), known by his courtesy title Lord John Russell before 1861, was a British Whig and Liberal statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1846 to 1852 and a ...

, with whom Peel had cooperated over the repeal of the

Corn Laws

The Corn Laws were tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and corn enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846. The word ''corn'' in British English denotes all cereal grains, including wheat, oats and barley. They wer ...

. After Peel's death in 1850, Gladstone emerged as the leader of the

Peelites

The Peelites were a breakaway dissident political faction of the British Conservative Party from 1846 to 1859. Initially led by Robert Peel, the former Prime Minister and Conservative Party leader in 1846, the Peelites supported free trade whilst ...

in the House of Commons. He was re-elected for the

University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

(i.e. representing the MA graduates of the university) at the General Election in 1847—Peel had once held this seat but had lost it because of his espousal of Catholic Emancipation in 1829. Gladstone became a constant critic of

Lord Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, (20 October 1784 – 18 October 1865) was a British statesman who was twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in the mid-19th century. Palmerston dominated British foreign policy during the period ...

.

In 1847 Gladstone helped to establish

Glenalmond College

Glenalmond College is a co-educational independent boarding school in Perth and Kinross, Scotland, for children aged between 12 and 18 years. It is situated on the River Almond near the village of Methven, about west of the city of Perth. ...

, then The Holy and Undivided Trinity College at Glenalmond. The school was set up as an episcopal foundation to spread the ideas of

Anglicanism in Scotland, and to educate the sons of the gentry.

As a young man Gladstone had treated his father's estate, Fasque, in

Forfarshire, southwest of Aberdeen, as home, but as a younger son he would not inherit it. Instead, from the time of his marriage, he lived at his wife's family's estate at

Hawarden

Hawarden (; cy, Penarlâg) is a village, community and electoral ward in Flintshire, Wales. It is part of the Deeside conurbation on the Wales-England border and is home to Hawarden Castle. In the 2011 census the ward of the same name had ...

in Flintshire, Wales. He never actually owned Hawarden, which belonged first to his brother-in-law

Sir Stephen Glynne, and was then inherited by Gladstone's eldest son in 1874. During the late 1840s, when he was out of office, he worked extensively to turn Hawarden into a viable business.

In 1848 he founded the

Church Penitentiary Association for the Reclamation of

Fallen Women. In May 1849 he began his most active "rescue work" and met prostitutes late at night on the street, in his house or in their houses, writing their names in a private notebook. He aided the

House of Mercy at

Clewer

Clewer (also known as Clewer Village) is an ecclesiastical parish and an area of Windsor in the county of Berkshire, England. Clewer makes up three wards of the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead, namely Clewer North, Clewer South and Cl ...

near

Windsor

Windsor may refer to:

Places Australia

* Windsor, New South Wales

** Municipality of Windsor, a former local government area

* Windsor, Queensland, a suburb of Brisbane, Queensland

**Shire of Windsor, a former local government authority around Wi ...

(which exercised extreme in-house discipline) and spent much time arranging employment for ex-prostitutes. In a "Declaration" signed on 7 December 1896 and only to be opened after his death, Gladstone wrote, "I desire to record my solemn declaration and assurance, as in the sight of God and before His Judgement Seat, that at no period of my life have I been guilty of the act which is known as that of infidelity to the marriage bed."

In 1850–51 Gladstone visited

Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

. Italy, for the benefit of his daughter Mary's eyesight. Giacomo Lacaita, legal adviser to the British embassy, was at the time imprisoned by the Neapolitan government, as were other political dissidents. Gladstone became concerned at the political situation in Naples and the arrest and imprisonment of Neapolitan liberals. In February 1851 Gladstone visited the prisons where thousands of them were held and was extremely outraged. In April and July he published two ''Letters to the Earl of Aberdeen'' against the Neapolitan government and responded to his critics in ''An Examination of the Official Reply of the Neapolitan Government'' in 1852. Gladstone's first letter described what he saw in Naples as "the negation of God erected into a system of government".

Chancellor of the Exchequer (1852–1855)

In 1852, following the appointment of

Lord Aberdeen

George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen, (28 January 178414 December 1860), styled Lord Haddo from 1791 to 1801, was a British statesman, diplomat and landowner, successively a Tory, Conservative and Peelite politician and specialist in ...

as Prime Minister, head of a coalition of

Whigs and Peelites, Gladstone became

Chancellor of the Exchequer. The Whig Sir

Charles Wood and the Tory Disraeli had both been perceived to have failed in the office and so this provided Gladstone with a great political opportunity.

His first budget in 1853 almost completed the work begun by Peel eleven years before in simplifying Britain's tariff of duties and customs. 123 duties were abolished and 133 duties were reduced. The income tax had legally expired but Gladstone proposed to extend it for seven years to fund tariff reductions:

We propose, then, to re-enact it for two years, from April, 1853, to April, 1855, at the rate of 7d. in the £; from April, 1855, to enact it for two more years at 6d. in the £; and then for three years more ... from April, 1857, at 5d. Under this proposal, on 5 April 1860, the income-tax will by law expire.

Gladstone wanted to maintain a balance between direct and indirect taxation and to abolish income tax. He knew that its abolition depended on a considerable retrenchment in government expenditure. He therefore increased the number of people eligible to pay it by lowering the threshold from £150 to £100. The more people that paid income tax, Gladstone believed, the more the public would pressure the government into abolishing it.

[Matthew, ''Gladstone, 1809–1874'', p. 127.] Gladstone argued that the £100 line was "the dividing line ... between the educated and the labouring part of the community" and that therefore the income tax payers and the electorate were to be the same people, who would then vote to cut government expenditure.

The budget speech (delivered on 18 April), nearly five hours long, raised Gladstone "at once to the front rank of financiers as of orators".

H.C.G. Matthew has written that Gladstone "made finance and figures exciting, and succeeded in constructing budget speeches epic in form and performance, often with lyrical interludes to vary the tension in the Commons as the careful exposition of figures and argument was brought to a climax". The contemporary diarist

Charles Greville wrote of Gladstone's speech:

... by universal consent it was one of the grandest displays and most able financial statement that ever was heard in the House of Commons; a great scheme, boldly, skilfully, and honestly devised, disdaining popular clamour and pressure from without, and the execution of it absolute perfection. Even those who do not admire the Budget, or who are injured by it, admit the merit of the performance. It has raised Gladstone to a great political elevation, and, what is of far greater consequence than the measure itself, has given the country assurance of a man equal to great political necessities, and fit to lead parties and direct governments.

During wartime, he insisted on raising taxes and not borrowing funds to pay for the war. The goal was to turn wealthy Britons against expensive wars. Britain entered the

Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

in February 1854, and Gladstone introduced his budget on 6 March. He had to increase expenditure on the military and a vote of credit of £1,250,000 was taken to send a force of 25,000 to the front. The deficit for the year would be £2,840,000 (estimated revenue £56,680,000; estimated expenditure £59,420,000). Gladstone refused to borrow the money needed to rectify this deficit and instead increased income tax by half, from sevenpence to tenpence-halfpenny in the pound (from 2.92% to 4.38%). By May another £6,870,000 was needed for the war and Gladstone raised the income tax from tenpence halfpenny to fourteen pence in the pound to raise £3,250,000. Spirits, malt, and sugar were taxed to raise the rest of the money needed. He proclaimed:

:The expenses of a war are the moral check which it has pleased the Almighty to impose upon the ambition and lust of conquest that are inherent in so many nations ... The necessity of meeting from year to year the expenditure which it entails is a salutary and wholesome check, making them feel what they are about, and making them measure the cost of the benefit upon which they may calculate

He served until 1855, a few weeks into Lord Palmerston's first premiership, and resigned along with the rest of the Peelites after a motion was passed to appoint a committee of inquiry into the conduct of the war.

Opposition (1855–1859)

The Conservative Leader

Lord Derby

Edward George Geoffrey Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby, (29 March 1799 – 23 October 1869, known before 1834 as Edward Stanley, and from 1834 to 1851 as Lord Stanley) was a British statesman, three-time Prime Minister of the United Kingdom ...

became Prime Minister in 1858, but Gladstone—who like the other Peelites was still nominally a Conservative—declined a position in his government, opting not to sacrifice his free trade principles.

Between November 1858 and February 1859, Gladstone, on behalf of Lord Derby's government, was made Extraordinary

Lord High Commissioner of the Ionian Islands

The Lord High Commissioner of the Ionian Islands was the local representative of the British government in the United States of the Ionian Islands between 1816 and 1864, succeeding the earlier office of the Civil Commissioner of the Ionian Island ...

embarking via Vienna and Trieste on a twelve-week mission to the southern Adriatic entrusted with complex challenges that had arisen in connection with the future of the British protectorate of the

United States of the Ionian Islands

The United States of the Ionian Islands ( el, Ἡνωμένον Κράτος τῶν Ἰονίων Νήσων, Inoménon-Krátos ton Ioníon Níson, United State of the Ionian Islands; it, Stati Uniti delle Isole Ionie) was a Greek state and a ...

.

In 1858, Gladstone took up the hobby of tree felling, mostly of oak trees, an exercise he continued with enthusiasm until he was 81 in 1891. Eventually, he became notorious for this activity, prompting

Lord Randolph Churchill

Lord Randolph Henry Spencer-Churchill (13 February 1849 – 24 January 1895) was a British statesman. Churchill was a Tory radical and coined the term 'Tory democracy'. He inspired a generation of party managers, created the National Union of ...

to observe: "For the purposes of recreation he has selected the felling of trees; and we may usefully remark that his amusements, like his politics, are essentially destructive. Every afternoon the whole world is invited to assist at the crashing fall of some beech or elm or oak. The forest laments in order that Mr Gladstone may perspire." Less noticed at the time was his practice of replacing the trees felled by planting new saplings.

Gladstone was a lifelong

bibliophile

Bibliophilia or bibliophilism is the love of books. A bibliophile or bookworm is an individual who loves and frequently reads and/or collects books.

Profile

The classic bibliophile is one who loves to read, admire and collect books, often ama ...

. In his lifetime, he read around 20,000 books, and eventually owned a library of over 32,000.

Chancellor of the Exchequer (1859–1866)

In 1859, Lord Palmerston formed a new mixed government with Radicals included, and Gladstone again joined the government (with most of the other remaining Peelites) as Chancellor of the Exchequer, to become part of the new

Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

.

Gladstone inherited a deficit of nearly £5,000,000, with income tax now set at 5d (fivepence). Like Peel, Gladstone dismissed the idea of borrowing to cover the deficit. Gladstone argued that "In time of peace nothing but dire necessity should induce us to borrow". Most of the money needed was acquired through raising the income tax to 9d. Usually not more than two-thirds of a tax imposed could be collected in a financial year so Gladstone therefore imposed the extra four pence at a rate of 8d. during the first half of the year so that he could obtain the additional revenue in one year. Gladstone's dividing line set up in 1853 had been abolished in 1858 but Gladstone revived it, with lower incomes to pay 6½d. instead of 9d. For the first half of the year the lower incomes paid 8d. and the higher incomes paid 13d. in income tax.

On 12 September 1859 the Radical MP

Richard Cobden

Richard Cobden (3 June 1804 – 2 April 1865) was an English Radical and Liberal politician, manufacturer, and a campaigner for free trade and peace. He was associated with the Anti-Corn Law League and the Cobden–Chevalier Treaty.

As a you ...

visited Gladstone, who recorded it in his diary: "... further conv. with Mr. Cobden on Tariffs & relations with France. We are closely & warmly agreed". Cobden was sent as Britain's representative to the negotiations with France's

Michel Chevalier

Michel Chevalier (; 13 January 1806 – 18 November 1879) was a French engineer, statesman, economist and free market liberal.

Biography

Born in Limoges, Haute-Vienne, Chevalier studied at the ''École Polytechnique'', obtaining an engineerin ...

for a free trade treaty between the two countries. Gladstone wrote to Cobden: "... the great aim—the moral and political significance of the act, and its probable and desired fruit in binding the two countries together by interest and affection. Neither you nor I attach for the moment any superlative value to this Treaty for the sake of the extension of British trade. ... What I look to is the social good, the benefit to the relations of the two countries, and the effect on the peace of Europe".

Gladstone's budget of 1860 was introduced on 10 February along with the

Cobden–Chevalier Treaty

The Cobden–Chevalier Treaty was an Anglo-French free trade agreement signed between Great Britain and France on 23 January 1860. After Britain began free trade policies in 1846, there remained tariffs with France. The 1860 treaty ended tariffs o ...

between Britain and France that would reduce tariffs between the two countries. This budget "marked the final adoption of the Free Trade principle, that taxation should be levied for Revenue purposes alone, and that every protective, differential, or discriminating duty ... should be dislodged". At the beginning of 1859, there were 419 duties in existence. The 1860 budget reduced the number of duties to 48, with 15 duties constituting the majority of the revenue. To finance these reductions in indirect taxation, the income tax, instead of being abolished, was raised to 10d. for incomes above £150 and at 7d. for incomes above £100.

In 1860 Gladstone intended to abolish the duty on paper—a controversial policy—because the duty traditionally inflated the cost of publishing and hindered the dissemination of radical working-class ideas. Although Palmerston supported continuation of the duty, using it and income tax revenue to buy arms, a majority of his Cabinet supported Gladstone. The Bill to abolish duties on paper narrowly passed Commons but was rejected by the House of Lords. No

money bill

In the Westminster system (and, colloquially, in the United States), a money bill or supply bill is a bill that solely concerns taxation or government spending (also known as appropriation of money), as opposed to changes in public law.

Conv ...

had been rejected by Lords for over 200 years, and a furore arose over this vote. The next year, Gladstone included the abolition of paper duty in a consolidated

Finance Bill

A government budget is a document prepared by the government and/or other political entity presenting its anticipated tax revenues (Inheritance tax, income tax, corporation tax, import taxes) and proposed spending/expenditure (Healthcare, Educat ...

(the first ever) to force the Lords to accept it, and accept it they did. The proposal in the Commons of one bill only per session for the national finances was a precedent uniformly followed from that date until 1910, and it has been ever since the rule.

Gladstone steadily reduced Income tax over the course of his tenure as Chancellor. In 1861 the tax was reduced to ninepence (£0–0s–9d), in 1863 to sevenpence, in 1864 to fivepence and in 1865 to fourpence. Gladstone believed that government was extravagant and wasteful with taxpayers' money and so sought to let money "fructify in the pockets of the people" by keeping taxation levels down through "peace and retrenchment". In 1859 he wrote to his brother, who was a member of the Financial Reform Association at Liverpool: "Economy is the first and great article (economy such as I understand it) in my financial creed. The controversy between direct and indirect taxation holds a minor, though important place". He wrote to his wife on 14 January 1860: "I am ''certain'', from experience, of the immense advantage of strict account-keeping in early life. It is just like learning the grammar then, which when once learned need not be referred to afterwards".

Due to his actions as Chancellor, Gladstone earned the reputation as the liberator of British trade and the working man's breakfast table, the man responsible for the emancipation of the popular press from "taxes upon knowledge" and for placing a duty on the succession of the estates of the rich. Gladstone's popularity rested on his taxation policies which meant to his supporters balance, social equity and political justice. The most significant expression of working-class opinion was at Northumberland in 1862 when Gladstone visited.

George Holyoake

George Jacob Holyoake (13 April 1817 – 22 January 1906) was an English secularist, co-operator and newspaper editor. He coined the terms secularism in 1851 and " jingoism" in 1878. He edited a secularist paper, the ''Reasoner'', from 1846 to J ...

recalled in 1865:

When Mr Gladstone visited the North, you well remember when word passed from the newspaper to the workman that it circulated through mines and mills, factories and workshops, and they came out to greet the only British minister who ever gave the English people a right because it was just they should have it ... and when he went down the Tyne, all the country heard how twenty miles of banks were lined with people who came to greet him. Men stood in the blaze of chimneys; the roofs of factories were crowded; colliers came up from the mines; women held up their children on the banks that it might be said in after life that they had seen the Chancellor of the People go by. The river was covered like the land. Every man who could ply an oar pulled up to give Mr Gladstone a cheer. When Lord Palmerston went to Bradford the streets were still, and working men imposed silence upon themselves. When Mr Gladstone appeared on the Tyne he heard cheer no other English minister ever heard ... the people were grateful to him, and rough pitmen who never approached a public man before, pressed round his carriage by thousands ... and thousands of arms were stretched out at once, to shake hands with Mr Gladstone as one of themselves.

When Gladstone first joined Palmerston's government in 1859, he had opposed further electoral reform, but he changed his position during Palmerston's last premiership, and by 1865 he was firmly in favour of enfranchising the working classes in towns. The policy caused friction with Palmerston, who strongly opposed enfranchisement. At the beginning of each

session, Gladstone would passionately urge the Cabinet to adopt new policies, while Palmerston would fixedly stare at a paper before him. At a lull in Gladstone's speech, Palmerston would smile, rap the table with his knuckles, and interject pointedly, "Now, my Lords and gentlemen, let us go to business". Although he personally was not a Nonconformist, and rather disliked them in person, he formed a coalition with the Nonconformists that gave the Liberals a powerful base of support.

American Civil War

Shortly after the outbreak of the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

Gladstone wrote to his friend the

Duchess of Sutherland that "the

principle announced by the

vice-president of the South...which asserts the superiority of the white man, and therewith founds on it his right to hold the black in slavery, I think that principle detestable, and I am wholly with the opponents of it" but that he felt that the North was wrong to try to restore the Union by military force, which he believed would end in failure.

[Morley, ''Life of Gladstone: II'', p. 82.] Palmerston's government adopted a position of British neutrality throughout the war, while declining to recognise the independence of the

Confederacy. In October 1862 Gladstone made a speech in

Newcastle Newcastle usually refers to:

*Newcastle upon Tyne, a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England

*Newcastle-under-Lyme, a town in Staffordshire, England

*Newcastle, New South Wales, a metropolitan area in Australia, named after Newcastle ...

in which he said that

Jefferson Davis and the other Confederate leaders had "made a nation", that the Confederacy seemed certain to succeed in asserting its independence from the North, and that the time might come when it would be the duty of the European powers to "offer friendly aid in compromising the quarrel." The speech caused consternation on both sides of the Atlantic and led to speculation that the Britain might be about to recognise the Confederacy."

[''The Times'' (20 October 1862), p. 7.] Gladstone was accused of sympathising with the South, a charge he rejected.

Gladstone was forced to clarify in the press that his comments in Newcastle had not been intended to signal a change in Government policy, but to express his belief that the North's efforts to defeat the South would fail, due to the strength of Southern resistance.

In a memorandum to the Cabinet later that month Gladstone wrote that, although he believed the Confederacy would probably win the war, it was "seriously tainted by its connection with slavery" and argued that the European powers should use their influence on the South to effect the "mitigation or removal of slavery."

Electoral reform

In May 1864 Gladstone said that he saw no reason in principle why all mentally able men could not be enfranchised, but admitted that this would only come about once the working classes themselves showed more interest in the subject. Queen Victoria was not pleased with this statement, and an outraged Palmerston considered it a seditious incitement to agitation.

Gladstone's support for electoral reform and disestablishment of the (Anglican)

Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the secon ...

won support from Nonconformists but alienated him from constituents in his Oxford University seat, and he lost it in the

1865 general election. A month later he stood as a candidate in

South Lancashire

South Lancashire is a geographical county area, used to indicate the southern part of the historic county of Lancashire, today without any administrative purpose. The county region has no exact boundaries but generally includes areas that form t ...

, where he was elected third MP (South Lancashire at this time elected three MPs). Palmerston campaigned for Gladstone in Oxford because he believed that his constituents would keep him "partially muzzled"; many Oxford graduates were Anglican clergymen at that time. A victorious Gladstone told his new constituency, "At last, my friends, I am come among you; and I am come—to use an expression which has become very famous and is not likely to be forgotten—I am come 'unmuzzled'."

On Palmerston's death in October, Earl Russell formed his second ministry. Russell and Gladstone (now the senior Liberal in the House of Commons) attempted to pass a reform bill, which was defeated in the Commons because the "

Adullamite" Whigs, led by

Robert Lowe, refused to support it. The Conservatives then formed a ministry, in which after long Parliamentary debate Disraeli passed the

Second Reform Act of 1867; Gladstone's proposed bill had been totally outmanoeuvred; he stormed into the Chamber, but too late to see his arch-enemy pass the bill. Gladstone was furious; his animus commenced a long rivalry that would only end on Disraeli's death and Gladstone's encomium in the Commons in 1881.

Leader of the Liberal Party, from 1867

Lord Russell retired in 1867 and Gladstone became leader of the Liberal Party.

[ In 1868 the Irish Church Resolutions was proposed as a measure to reunite the Liberal Party in government (on the issue of disestablishment of the ]Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the secon ...

—this would be done during Gladstone's First Government in 1869 and meant that Irish Roman Catholics did not need to pay their tithe

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash or cheques or more ...

s to the Anglican Church of Ireland). When it was passed Disraeli took the hint and called a General Election.

First premiership (1868–1874)

In the next general election in 1868, the South Lancashire constituency had been broken up by the Second Reform Act

The Representation of the People Act 1867, 30 & 31 Vict. c. 102 (known as the Reform Act 1867 or the Second Reform Act) was a piece of British legislation that enfranchised part of the urban male working class in England and Wales for the first ...

into two: South East Lancashire and South West Lancashire. Gladstone stood for South West Lancashire and for Greenwich

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich ...

, it being quite common then for candidates to stand in two constituencies

An electoral district, also known as an election district, legislative district, voting district, constituency, riding, ward, division, or (election) precinct is a subdivision of a larger state (a country, administrative region, or other polity ...

simultaneously.The only means which have been placed in my power of 'raising the wages of colliers' has been by endeavouring to beat down all those restrictions upon trade which tend to reduce the price to be obtained for the product of their labour, & to lower as much as may be the taxes on the commodities which they may require for use or for consumption. Beyond this I look to the forethought not yet so widely diffused in this country as in Scotland, & in some foreign lands; & I need not remind you that in order to facilitate its exercise the Government have been empowered by Legislation to become through the Dept. of the P.O. the receivers & guardians of savings.

Gladstone's first premiership instituted reforms in the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

, civil service, and local government to cut restrictions on individual advancement. The Local Government Board Act 1871 put the supervision of the Poor Law under the Local Government Board (headed by G.J. Goschen) and Gladstone's "administration could claim spectacular success in enforcing a dramatic reduction in supposedly sentimental and unsystematic outdoor poor relief, and in making, in co-operation with the Charity Organization Society

The Charity Organisation Societies were founded in England in 1869 following the ' Goschen Minute' that sought to severely restrict outdoor relief distributed by the Poor Law Guardians. In the early 1870s a handful of local societies were formed w ...

(1869), the most sustained attempt of the century to impose upon the working classes the Victorian values of providence, self-reliance, foresight, and self-discipline". Gladstone was associated with the Charity Organization Society's first annual report in 1870. Some leading Conservatives at this time were contemplating an alliance between the aristocracy and the working class against the capitalist class, an idea called the New Social Alliance. At a speech at Blackheath on 28 October 1871, he warned his constituents against these social reformers:

... they are not your friends, but they are your enemies in fact, though not in intention, who teach you to look to the Legislature for the radical removal of the evils that afflict human life. ... It is the individual mind and conscience, it is the individual character, on which mainly human happiness or misery depends. (Cheers.) The social problems that confront us are many and formidable. Let the Government labour to its utmost, let the Legislature labour days and nights in your service; but, after the very best has been attained and achieved, the question whether the English father is to be the father of a happy family and the centre of a united home is a question which must depend mainly upon himself. (Cheers.) And those who ... promise to the dwellers in towns that every one of them shall have a house and garden in free air, with ample space; those who tell you that there shall be markets for selling at wholesale prices retail quantities—I won't say are impostors, because I have no doubt they are sincere; but I will say they are quacks (cheers); they are deluded and beguiled by a spurious philanthropy, and when they ought to give you substantial, even if they are humble and modest boons, they are endeavouring, perhaps without their own consciousness, to delude you with fanaticism, and offering to you a fruit which, when you attempt to taste it, will prove to be but ashes in your mouths. (Cheers.)

Gladstone instituted abolition of the sale of commissions in the army: he also instituted the Cardwell Reforms in 1869 that made peacetime

Gladstone instituted abolition of the sale of commissions in the army: he also instituted the Cardwell Reforms in 1869 that made peacetime flogging

Flagellation (Latin , 'whip'), flogging or whipping is the act of beating the human body with special implements such as whips, rods, switches, the cat o' nine tails, the sjambok, the knout, etc. Typically, flogging has been imposed on ...

illegal. In 1870, his government passed the Irish Land Act

The Land Acts (officially Land Law (Ireland) Acts) were a series of measures to deal with the question of tenancy contracts and peasant proprietorship of land in Ireland in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Five such acts were introduced by ...

and Forster's Education Act. In 1871 his government passed the Trade Union Act allowing trade unions to organise and operate legally for the first time (although picketing remained illegal). Gladstone later counted this reform as one of the most significant of the previous half century, saying that prior to its passage the law had effectively "compelled the British workman to work...in chains."Universities Tests Act

The Universities Tests Act 1871 was an Act of Parliament, Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It abolished religious "Tests" and allowed Roman Catholics, Nonconformist (Protestantism), non-conformists and non-Christians to take up profe ...

. He secured passage of the Ballot Act for secret ballots, and the Licensing Act 1872

The Licensing Act 1872 (35 & 36 Vict c 94) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is one of the Licensing Acts 1828 to 1886 and was one of the Licensing (Ireland) Acts 1833 to 1886. It enacted various regulations and offences r ...

. In foreign affairs his over-riding aim was to promote peace and understanding, characterised by his settlement of the ''Alabama'' Claims in 1872 in favour of the Americans. During this time, his government gave approval to launch the expedition of HMS Challenger at a time when public interest had turned away from scientific explorations. His leadership also led to the passage of the Supreme Court of Judicature Act 1873

The Supreme Court of Judicature Act 1873 (sometimes known as the Judicature Act 1873) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom in 1873. It reorganised the English court system to establish the High Court and the Court of Appeal, and ...

restructuring the courts to create the modern High Court and Court of Appeal.

Gladstone unexpectedly dissolved Parliament in January 1874 and called a general election.

Gladstone's proposals went some way to meet working-class demands, such as the realisation of the free breakfast table through repealing duties on tea and sugar, and reform of local taxation which was increasing for the poorer ratepayers. According to the working-class financial reformer Thomas Briggs, writing in the trade unionist newspaper '' The Bee-Hive'', the manifesto relied on "a much higher authority than Mr. Gladstone...viz., the late Richard Cobden". The dissolution itself was reported in ''The Times'' on 24 January. On 30 January, the names of the first fourteen MPs for uncontested seats were published. By 9 February a Conservative victory was apparent. In contrast to 1868 and 1880 when the Liberal campaign lasted several months, only three weeks separated the news of the dissolution and the election. The working-class newspapers were so taken by surprise they had little time to express an opinion on Gladstone's manifesto before the election was over. Unlike the efforts of the Conservatives, the organisation of the Liberal Party had declined since 1868 and they had also failed to retain Liberal voters on the electoral register. George Howell wrote to Gladstone on 12 February: "There is one lesson to be learned from this Election, that is Organization. ... We have lost not by a change of sentiment so much as by want of organised power". The Liberals received a majority of the vote in each of the constituent countries of the United Kingdom and 189,000 more votes nationally than the Conservatives. However, they obtained a minority of seats in the House of Commons.

Opposition (1874–1880)

In the wake of Benjamin Disraeli's victory, Gladstone retired from the leadership of the Liberal party, although he retained his seat in the House.

In the wake of Benjamin Disraeli's victory, Gladstone retired from the leadership of the Liberal party, although he retained his seat in the House.

Anti-Catholicism

Gladstone had a complex ambivalence about Catholicism. He was attracted by its international success in majestic traditions. More important, he was strongly opposed to the authoritarianism of its pope and bishops, its profound public opposition to liberalism, and its refusal to distinguish between secular allegiance on the one hand and spiritual obedience on the other. The danger came when the pope or bishops attempted to exert temporal power, as in the Vatican decrees of 1870 as the climax of the papal attempt to control churches in different nations, despite their independent nationalism. On the other hand, when ritual practices in the Church of England—such as vestments and incense—came under attack as too ritualistic and too much akin to Catholicism, Gladstone strongly opposed passage of the Public Worship Regulation Act

The Public Worship Regulation Act 1874 (37 & 38 Vict c 85) was an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom, introduced as a Private Member's Bill by Archbishop of Canterbury Archibald Campbell Tait, to limit what he perceived as the growing ritual ...

in 1874.

In November 1874, he published the pamphlet '' The Vatican Decrees in their Bearing on Civil Allegiance'', directed at the First Vatican Council's dogmatising Papal Infallibility

Papal infallibility is a dogma of the Catholic Church which states that, in virtue of the promise of Jesus to Peter, the Pope when he speaks '' ex cathedra'' is preserved from the possibility of error on doctrine "initially given to the apos ...

in 1870, which had outraged him. Gladstone claimed that this decree had placed British Catholics in a dilemma over conflicts of loyalty to the Crown. He urged them to reject papal infallibility as they had opposed the Spanish Armada of 1588. The pamphlet sold 150,000 copies by the end of 1874. Cardinal Manning denied that the council had changed the relation of Catholics to their civil governments, and Archbishop James Roosevelt Bayley

James Roosevelt Bayley (August 23, 1814 – October 3, 1877) was an American prelate of the Catholic Church. He served as the first Bishop of Newark (1853–1872) and the eighth Archbishop of Baltimore (1872–1877).

Early life and educa ...

, in a letter which was obtained by the '' New York Herald'' and published without Bayley's express permission, called Gladstone's declaration "a shameful calumny" and attributed his "monomania" to the "political hari-kari" he had committed by dissolving Parliament, accusing him of "putting on 'the cap and bells

A cap is a flat headgear, usually with a visor. Caps have crowns that fit very close to the head. They made their first appearance as early as 3200 BC. Caps typically have a visor, or no brim at all. They are popular in casual and informal se ...

' and attempting to play the part of Lord George Gordon

Lord George Gordon (26 December 1751 – 1 November 1793) was a British politician best known for lending his name to the Gordon Riots of 1780.

An eccentric and flighty personality, he was born into the Scottish nobility and sat in the Hous ...

" in order to restore his political fortunes.John Henry Newman

John Henry Newman (21 February 1801 – 11 August 1890) was an English theologian, academic, intellectual, philosopher, polymath, historian, writer, scholar and poet, first as an Anglican ministry, Anglican priest and later as a Catholi ...

wrote the ''Letter to the Duke of Norfolk

''Letter to the Duke of Norfolk'' is a book written in 1875 by St John Henry Newman. Consisting of about 150 pages, it was meant as a response to Protestant-Catholic polemics that had emerged in the era of the First Vatican Council. In the book, ...

'' in reply to Gladstone's charges that Catholics have "no mental freedom" and cannot be good citizens.

A second pamphlet followed in Feb 1875, a defence of the earlier pamphlet and a reply to his critics, entitled ''Vaticanism: an Answer to Reproofs and Replies''. He described the Catholic Church as "an Asian monarchy: nothing but one giddy height of despotism, and one dead level of religious subservience". He further claimed that the Pope wanted to destroy the rule of law and replace it with arbitrary tyranny, and then to hide these "crimes against liberty beneath a suffocating cloud of incense".

Opposition to socialism

Gladstone was opposed to socialism after 1842, when he heard a socialist lecturer. Lord Kilbracken, one of Gladstone's secretaries commented:

The Liberal doctrines of that time, with their violent anti-socialist spirit and their strong insistence on the gospel of thrift, self-help, settlement of wages by the higgling of the market, and non-interference by the State.... I think that Mr. Gladstone was the strongest anti-socialist that I have ever known....It is quite true, as has been often said, that “we are all socialists up to a certain point”; but Mr. Gladstone fixed that point lower, and was more vehement against those who went above it, than any other politician or official of my acquaintance. I remember his speaking indignantly to me of the budget of 1874 as “That socialistic budget of Northcote's,” merely because of the special relief which it gave to the poorer class of income-tax payers. His strong belief in Free Trade was only one of the results of his deep-rooted conviction that the Government's interference with the free action of the individual, whether by taxation or otherwise, should be kept at an irreducible minimum. It is, indeed, not too much to say that his conception of Liberalism was the negation of Socialism.

Bulgarian Horrors

A pamphlet Gladstone published on 6 September 1876, ''Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East'', attacked the Disraeli government for its indifference to the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

's violent repression of the Bulgarian April uprising. Gladstone made clear his hostility focused on the Turkish people, rather than on the Muslim religion. The Turks he said:

The historian

The historian Geoffrey Alderman

Geoffrey Alderman (born 10 February 1944) is a British historian that specialises in 19th and 20th centuries Jewish community in England. He is also a political adviser and journalist.

Life

Born in Middlesex, Alderman was educated at Hackney D ...

has described Gladstone as "unleashing the full fury of his oratorical powers against Jews and Jewish influence" during the Bulgarian Crisis (1885–88) Bulgarian Crisis may refer to:

* Bulgarian Crisis (1885–88)

*Bulgarian Declaration of Independence (1908)

*Negotiations of Bulgaria with the Central Powers and the Entente The Negotiations of Bulgaria with the Central Powers and the Entente were a ...

, telling a journalist in 1876 that: "I deeply deplore the manner in which, what I may call Judaic sympathies, beyond as well as within the circle of professed Judaism, are now acting on the question of the East".[Alderman, Geoffrey. ''Modern British Jewry''. Oxford: Clarendon, 1992, p. 100] Gladstone similarly refused to speak out against the persecution of Romanian Jews in the 1870s and Russian Jews in the early 1880s.Russian Jews

The history of the Jews in Russia and areas historically connected with it goes back at least 1,500 years. Jews in Russia have historically constituted a large religious and ethnic diaspora; the Russian Empire at one time hosted the largest pop ...

... Alderman attributes these developments, along with other factors, to the collapse of the previously strong ties between British Jews and Liberalism.Midlothian campaign

The Midlothian campaign of 1878–80 was a series of foreign policy speeches given by William Gladstone, leader of Britain's Liberal Party. It is often cited as the first modern political campaign. It also set the stage for Gladstone's comeback ...

, he rousingly denounced Disraeli's foreign policies during the ongoing Second Anglo-Afghan War

The Second Anglo-Afghan War (Dari: جنگ دوم افغان و انگلیس, ps, د افغان-انګرېز دويمه جګړه) was a military conflict fought between the British Raj and the Emirate of Afghanistan from 1878 to 1880, when the l ...

in Afghanistan. (See Great Game

The Great Game is the name for a set of political, diplomatic and military confrontations that occurred through most of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century – involving the rivalry of the British Empire and the Russian Empi ...

). He saw the war as "great dishonour" and also criticised British conduct in the Zulu War

The Anglo-Zulu War was fought in 1879 between the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom. Following the passing of the British North America Act of 1867 forming a federation in Canada, Lord Carnarvon thought that a similar political effort, coup ...

. Gladstone also (on 29 November) condemned what he saw as the Conservative government's profligate spending:

...the Chancellor of the Exchequer shall boldly uphold economy in detail; and it is the mark ... of ... a chicken-hearted Chancellor of the Exchequer, when he shrinks from upholding economy in detail, when, because it is a question of only £2,000 or £3,000, he says that is no matter. He is ridiculed, no doubt, for what is called saving candle-ends and cheese-parings. No Chancellor of the Exchequer is worth his salt who is not ready to save what are meant by candle-ends and cheese-parings in the cause of his country. No Chancellor of the Exchequer is worth his salt who makes his own popularity either his first consideration, or any consideration at all, in administrating the public purse. You would not like to have a housekeeper or steward who made her or his popularity with the tradesmen the measure of the payments that were to be delivered to them. In my opinion the Chancellor of the Exchequer is the trusted and confidential steward of the public. He is under a sacred obligation with regard to all that he consents to spend.... I am bound to say hardly ever in the six years that Sir Stafford Northcote has been in office have I heard him speak a resolute word on behalf of economy.

Second premiership (1880–1885)

In 1880, the Liberals won again and the Liberal leaders, Lord Hartington (leader in the House of Commons) and Lord Granville, retired in Gladstone's favour. Gladstone won his constituency election in Midlothian and also in

In 1880, the Liberals won again and the Liberal leaders, Lord Hartington (leader in the House of Commons) and Lord Granville, retired in Gladstone's favour. Gladstone won his constituency election in Midlothian and also in Leeds

Leeds () is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the third-largest settlement (by popula ...

, where he had also been adopted as a candidate. As he could lawfully only serve as MP for one constituency, Leeds was passed to his son Herbert

Herbert may refer to:

People Individuals

* Herbert (musician), a pseudonym of Matthew Herbert

Name

* Herbert (given name)

* Herbert (surname)

Places Antarctica

* Herbert Mountains, Coats Land

* Herbert Sound, Graham Land

Australia

* Herbert ...

. One of his other sons, Henry

Henry may refer to:

People

*Henry (given name)

* Henry (surname)

* Henry Lau, Canadian singer and musician who performs under the mononym Henry

Royalty

* Portuguese royalty

** King-Cardinal Henry, King of Portugal

** Henry, Count of Portugal, ...

, was also elected as an MP. Queen Victoria asked Lord Hartington to form a ministry, but he persuaded her to send for Gladstone. Gladstone's second administration—both as Prime Minister and again as Chancellor of the Exchequer until 1882—lasted from June 1880 to June 1885. He originally intended to retire at the end of 1882, the 50th anniversary of his entry into politics, but did not do so.

Foreign policy

Historians have debated the wisdom of Gladstone's foreign-policy during his second ministry. Paul Hayes says it "provides one of the most intriguing and perplexing tales of muddle and incompetence in foreign affairs, unsurpassed in modern political history until the days of Grey