France (), officially the French Republic ( ),

is a country primarily located in

Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

. It also comprises of

overseas regions and territories in the

Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

and the

Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

,

Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

and

Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by t ...

s. Its

metropolitan area extends from the

Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

to the Atlantic Ocean and from the

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

to the

English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

and the

North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea, epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the ...

; overseas territories include

French Guiana

French Guiana ( or ; french: link=no, Guyane ; gcr, label=French Guianese Creole, Lagwiyann ) is an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France on the northern Atlantic coast of South America in the Guianas. ...

in

South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sout ...

,

Saint Pierre and Miquelon

Saint Pierre and Miquelon (), officially the Territorial Collectivity of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon (french: link=no, Collectivité territoriale de Saint-Pierre et Miquelon ), is a self-governing territorial overseas collectivity of France in t ...

in the North Atlantic, the

French West Indies, and many islands in

Oceania

Oceania (, , ) is a geographical region that includes Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Spanning the Eastern and Western hemispheres, Oceania is estimated to have a land area of and a population of around 44.5 million ...

and the Indian Ocean. Due to its several coastal territories, France has the largest

exclusive economic zone in the world. France borders

Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

,

Luxembourg

Luxembourg ( ; lb, Lëtzebuerg ; french: link=no, Luxembourg; german: link=no, Luxemburg), officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, ; french: link=no, Grand-Duché de Luxembourg ; german: link=no, Großherzogtum Luxemburg is a small lan ...

,

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

,

Switzerland,

Monaco

Monaco (; ), officially the Principality of Monaco (french: Principauté de Monaco; Ligurian: ; oc, Principat de Mónegue), is a sovereign city-state and microstate on the French Riviera a few kilometres west of the Italian region of Lig ...

,

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

,

Andorra

, image_flag = Flag of Andorra.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Andorra.svg

, symbol_type = Coat of arms

, national_motto = la, Virtus Unita Fortior, label=none (Latin)"United virtue is stro ...

, and

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

in

continental Europe, as well as the

Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

,

Suriname, and

Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

in the Americas via its overseas territories in French Guiana and

Saint Martin. Its

eighteen integral regions (five of which are overseas) span a combined area of and contain close to 68 million people ().

[ France is a ]unitary

Unitary may refer to:

Mathematics

* Unitary divisor

* Unitary element

* Unitary group

* Unitary matrix

* Unitary morphism

* Unitary operator

* Unitary transformation

* Unitary representation

* Unitarity (physics)

* ''E''-unitary inverse semigrou ...

semi-presidential

A semi-presidential republic, is a republic in which a president exists alongside a prime minister and a cabinet, with the latter two being responsible to the legislature of the state. It differs from a parliamentary republic in that it has a ...

republic with its capital in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

, the country's largest city

The United Nations uses three definitions for what constitutes a city, as not all cities in all jurisdictions are classified using the same criteria. Cities may be defined as the cities proper, the extent of their urban area, or their metropo ...

and main cultural and commercial centre; other major urban areas

An urban area, built-up area or urban agglomeration is a human settlement with a high population density and infrastructure of built environment. Urban areas are created through urbanization and are categorized by urban morphology as cities, ...

include Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Fra ...

, Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan language, Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, third-largest city and Urban area (France), second-largest metropolitan area of F ...

, Toulouse

Toulouse ( , ; oc, Tolosa ) is the prefecture of the French department of Haute-Garonne and of the larger region of Occitania. The city is on the banks of the River Garonne, from the Mediterranean Sea, from the Atlantic Ocean and from Pa ...

, Lille

Lille ( , ; nl, Rijsel ; pcd, Lile; vls, Rysel) is a city in the northern part of France, in French Flanders. On the river Deûle, near France's border with Belgium, it is the capital of the Hauts-de-France region, the prefecture of the N ...

, Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( , ; Gascon oc, Bordèu ; eu, Bordele; it, Bordò; es, Burdeos) is a port city on the river Garonne in the Gironde department, Southwestern France. It is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the prefect ...

, and Nice

Nice ( , ; Niçard dialect, Niçard: , classical norm, or , nonstandard, ; it, Nizza ; lij, Nissa; grc, Νίκαια; la, Nicaea) is the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes departments of France, department in France. The Nice urban unit, agg ...

.

Inhabited since the Palaeolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic (), also called the Old Stone Age (from Greek: παλαιός ''palaios'', "old" and λίθος '' lithos'', "stone"), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone to ...

era, the territory of Metropolitan France was settled by Celtic tribes known as Gauls

The Gauls ( la, Galli; grc, Γαλάται, ''Galátai'') were a group of Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age and the Roman period (roughly 5th century BC to 5th century AD). Their homeland was known as Gaul (''Gallia''). They s ...

during the Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostl ...

. Rome annexed the area in 51 BC, leading to a distinct Gallo-Roman culture that laid the foundation of the French language. The Germanic Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools, ...

formed the Kingdom of Francia

Francia, also called the Kingdom of the Franks ( la, Regnum Francorum), Frankish Kingdom, Frankland or Frankish Empire ( la, Imperium Francorum), was the largest post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Franks dur ...

, which became the heartland of the Carolingian Empire

The Carolingian Empire (800–888) was a large Frankish-dominated empire in western and central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the ...

. The Treaty of Verdun

The Treaty of Verdun (), agreed in , divided the Frankish Empire into three kingdoms among the surviving sons of the emperor Louis I, the son and successor of Charlemagne. The treaty was concluded following almost three years of civil war and ...

of 843 partitioned the empire, with West Francia

In medieval history, West Francia (Medieval Latin: ) or the Kingdom of the West Franks () refers to the western part of the Frankish Empire established by Charlemagne. It represents the earliest stage of the Kingdom of France, lasting from about ...

becoming the Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France ( fro, Reaume de France; frm, Royaulme de France; french: link=yes, Royaume de France) is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the medieval and early modern period ...

in 987. In the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended around AD 150 ...

, France was a powerful but highly decentralised feudal kingdom. Philip II Philip II may refer to:

* Philip II of Macedon (382–336 BC)

* Philip II (emperor) (238–249), Roman emperor

* Philip II, Prince of Taranto (1329–1374)

* Philip II, Duke of Burgundy (1342–1404)

* Philip II, Duke of Savoy (1438-1497)

* Philip ...

successfully strengthened royal power and defeated his rivals to double the size of the crown lands

Crown land (sometimes spelled crownland), also known as royal domain, is a territorial area belonging to the monarch, who personifies the Crown. It is the equivalent of an entailed estate and passes with the monarchy, being inseparable from it. ...

; by the end of his reign, France had emerged as the most powerful state in Europe. From the mid-14th to the mid-15th century, France was plunged into a series of dynastic conflicts involving England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, collectively known as the Hundred Years' War, and a distinct French identity emerged as a result. The French Renaissance

The French Renaissance was the cultural and artistic movement in France between the 15th and early 17th centuries. The period is associated with the pan-European Renaissance, a word first used by the French historian Jules Michelet to define th ...

saw art and culture flourish, conflict with the House of Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

, and the establishment of a global colonial empire, which by the 20th century would become the second-largest in the world.Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

that severely weakened the country. France again emerged as Europe's dominant power in the 17th century under Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Ver ...

following the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of battle ...

. Inadequate economic policies, inequitable taxes and frequent wars (notably a defeat in the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (175 ...

and costly involvement in the American War of Independence) left the kingdom in a precarious economic situation by the end of the 18th century. This precipitated the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

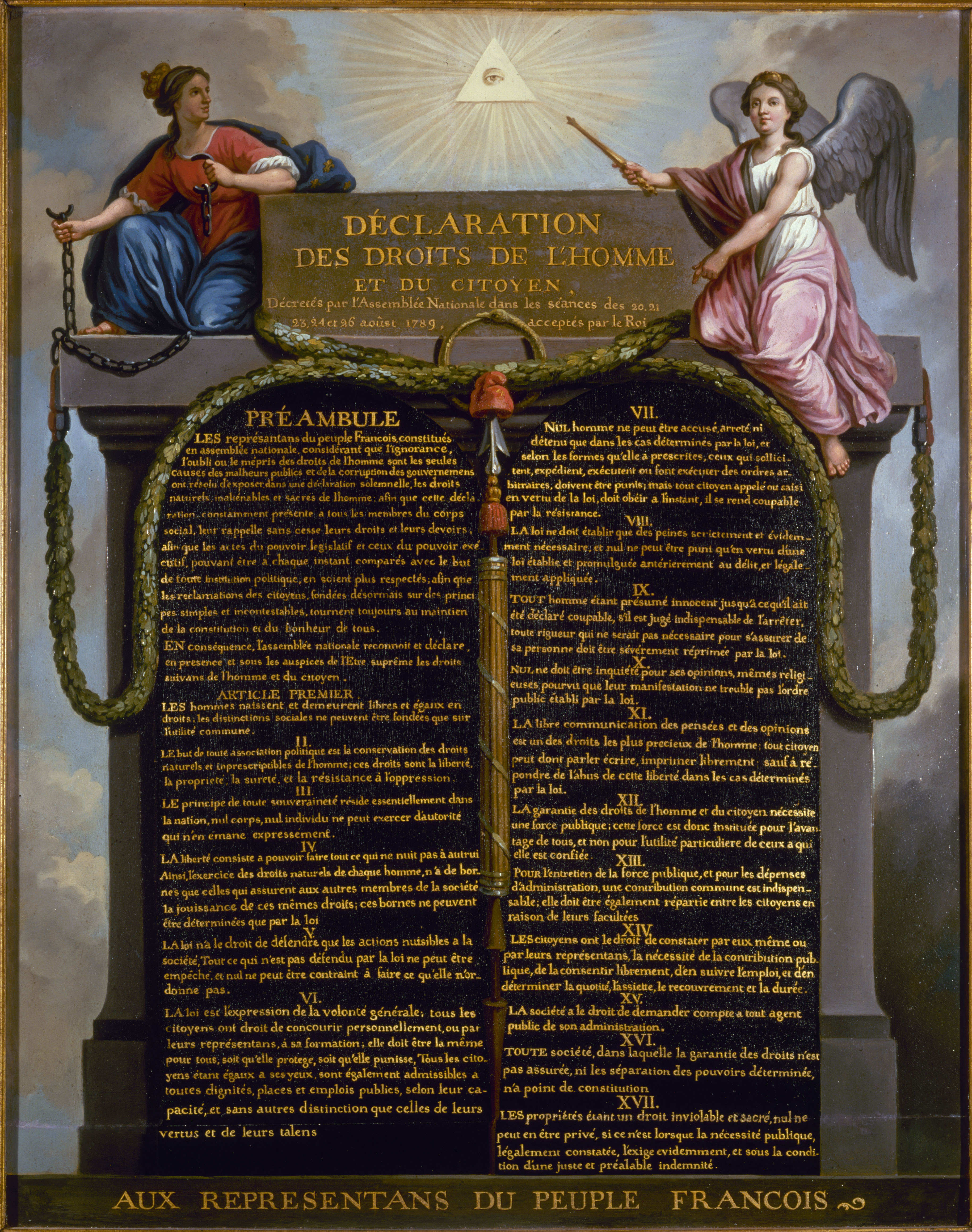

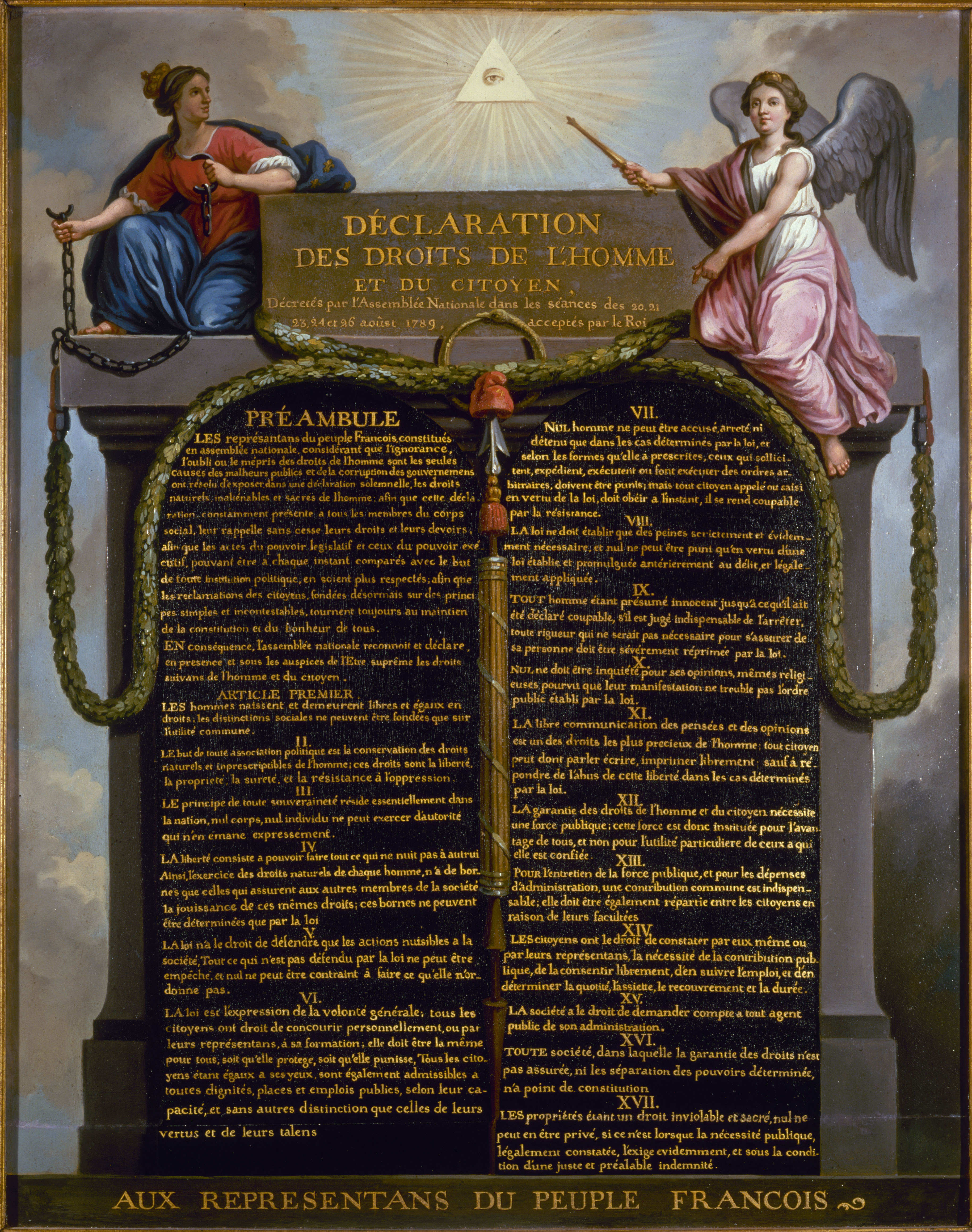

of 1789, which overthrew the and produced the Declaration of the Rights of Man

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (french: Déclaration des droits de l'homme et du citoyen de 1789, links=no), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human civil rights document from the French Revolu ...

, which expresses the nation's ideals to this day.

France reached its political and military zenith in the early 19th century under Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

, subjugating much of continental Europe and establishing the First French Empire

The First French Empire, officially the French Republic, then the French Empire (; Latin: ) after 1809, also known as Napoleonic France, was the empire ruled by Napoleon Bonaparte, who established French hegemony over much of continental E ...

. The French Revolutionary

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are consider ...

and Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

shaped the course of European and world history. The collapse of the empire initiated a period of relative decline, in which France endured a tumultuous succession of governments until the founding of the French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (french: Troisième République, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 19 ...

during the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. Subsequent decades saw a period of optimism, cultural and scientific flourishing, as well as economic prosperity, known as the Belle Époque. France was one of the major participants of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, from which it emerged victorious at a great human and economic cost. It was among the Allied powers of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

but was soon occupied

' (Norwegian: ') is a Norwegian political thriller TV series that premiered on TV2 on 5 October 2015. Based on an original idea by Jo Nesbø, the series is co-created with Karianne Lund and Erik Skjoldbjærg. Season 2 premiered on 10 October ...

by the Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

in 1940. Following liberation

Liberation or liberate may refer to:

Film and television

* ''Liberation'' (film series), a 1970–1971 series about the Great Patriotic War

* "Liberation" (''The Flash''), a TV episode

* "Liberation" (''K-9''), an episode

Gaming

* '' Liberati ...

in 1944, the short-lived Fourth Republic was established and later dissolved in the course of the Algerian War. The current Fifth Republic was formed in 1958 by Charles de Gaulle. Algeria and most French colonies became independent in the 1960s, with the majority retaining close economic and military ties with France.

France retains its centuries-long status as a global centre of art

Art is a diverse range of human activity, and resulting product, that involves creative or imaginative talent expressive of technical proficiency, beauty, emotional power, or conceptual ideas.

There is no generally agreed definition of wha ...

, science

Science is a systematic endeavor that Scientific method, builds and organizes knowledge in the form of Testability, testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earli ...

and philosophy. It hosts

A host is a person responsible for guests at an event or for providing hospitality during it.

Host may also refer to:

Places

*Host, Pennsylvania, a village in Berks County

People

*Jim Host (born 1937), American businessman

*Michel Host ( ...

the fifth-largest number of UNESCO World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for h ...

s and is the world's leading tourist destination, receiving over 89 million foreign visitors in 2018. France is a developed country ranked 28th in the Human Development Index

The Human Development Index (HDI) is a statistic composite index of life expectancy, education (mean years of schooling completed and expected years of schooling upon entering the education system), and per capita income indicators, wh ...

, with the world's seventh-largest economy by nominal GDP and tenth-largest by PPP; in terms of aggregate household wealth, it ranks fourth in the world. France performs well in international rankings

This is a list of international rankings.

By category

Agriculture

*List of largest producing countries of agricultural commodities

*List of countries by apple production

* List of countries by apricot production

* List of countries by artichoke p ...

of education

Education is a purposeful activity directed at achieving certain aims, such as transmitting knowledge or fostering skills and character traits. These aims may include the development of understanding, rationality, kindness, and honesty ...

, health care, and life expectancy

Life expectancy is a statistical measure of the average time an organism is expected to live, based on the year of its birth, current age, and other demographic factors like sex. The most commonly used measure is life expectancy at birth ...

. It remains a great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power in ...

in global affairs, being one of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council

The permanent members of the United Nations Security Council (also known as the Permanent Five, Big Five, or P5) are the five sovereign states to whom the UN Charter of 1945 grants a permanent seat on the UN Security Council: China, France, ...

and an official nuclear-weapon state. France is a founding and leading member of the European Union and the Eurozone

The euro area, commonly called eurozone (EZ), is a currency union of 19 member states of the European Union (EU) that have adopted the euro ( €) as their primary currency and sole legal tender, and have thus fully implemented EMU polici ...

,Group of Seven

The Group of Seven (G7) is an intergovernmental political forum consisting of Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States; additionally, the European Union (EU) is a "non-enumerated member". It is officiall ...

, North Atlantic Treaty Organization

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

(NATO), Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and Francophonie.

Etymology and pronunciation

Originally applied to the whole Frankish Empire

Francia, also called the Kingdom of the Franks ( la, Regnum Francorum), Frankish Kingdom, Frankland or Frankish Empire ( la, Imperium Francorum), was the largest post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Franks du ...

, the name ''France'' comes from the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, or "realm of the Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools, ...

". Modern France is still named today in Italian and Spanish, while in German, in Dutch and in Swedish all mean "Land/realm of the Franks".

The name of the Franks

The name of the Franks (Latin ''Franci''), alongside the derived names of ''Francia'' and ''Franconia'' (and the adjectives ''Frankish'' and ''Franconian''), are derived from the name given to a Germanic tribal confederation which emerged in the ...

is related to the English word ''frank'' ("free"): the latter stems from the Old French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intellig ...

("free, noble, sincere"), ultimately from Medieval Latin

Medieval Latin was the form of Literary Latin used in Roman Catholic Western Europe during the Middle Ages. In this region it served as the primary written language, though local languages were also written to varying degrees. Latin functione ...

''francus'' ("free, exempt from service; freeman, Frank"), a generalisation of the tribal name that emerged as a Late Latin

Late Latin ( la, Latinitas serior) is the scholarly name for the form of Literary Latin of late antiquity.Roberts (1996), p. 537. English dictionary definitions of Late Latin date this period from the , and continuing into the 7th century in t ...

borrowing of the reconstructed Frankish

Frankish may refer to:

* Franks, a Germanic tribe and their culture

** Frankish language or its modern descendants, Franconian languages

* Francia, a post-Roman state in France and Germany

* East Francia, the successor state to Francia in Germany ...

endonym .Proto-Germanic

Proto-Germanic (abbreviated PGmc; also called Common Germanic) is the reconstructed proto-language of the Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages.

Proto-Germanic eventually developed from pre-Proto-Germanic into three Germanic bran ...

word , which translates as "javelin" or "lance" (the throwing axe of the Franks was known as the '' francisca''), although these weapons may have been named because of their use by the Franks, not the other way around.Received Pronunciation

Received Pronunciation (RP) is the accent traditionally regarded as the standard and most prestigious form of spoken British English. For over a century, there has been argument over such questions as the definition of RP, whether it is geog ...

, though it can be also heard in some other dialects such as Cardiff English

The Cardiff accent, also known as Cardiff English, is the regional accent of English, and a variety of Welsh English, as spoken in and around the city of Cardiff, and is somewhat distinctive in Wales, compared with other Welsh accents. Its pit ...

, in which is in free variation with .

History

Prehistory (before the 6th century BC)

The oldest traces of human life in what is now France date from approximately 1.8 million years ago.

The oldest traces of human life in what is now France date from approximately 1.8 million years ago.[Jean Carpentier (dir.), François Lebrun (dir.), Alain Tranoy, Élisabeth Carpentier et Jean-Marie Mayeur (préface de Jacques Le Goff), Histoire de France, Points Seuil, coll. " Histoire ", Paris, 2000 (1re éd. 1987), p. 17 ] Over the ensuing millennia, human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, cultu ...

s were confronted by a harsh and variable climate, marked by several glacial period

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betwe ...

s. Early hominids led a nomad

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the po ...

ic hunter-gatherer life.Upper Paleolithic

The Upper Paleolithic (or Upper Palaeolithic) is the third and last subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. Very broadly, it dates to between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago (the beginning of the Holocene), according to some theories coin ...

era, including one of the most famous and best-preserved, Lascaux

Lascaux ( , ; french: Grotte de Lascaux , "Lascaux Cave") is a network of caves near the village of Montignac, in the department of Dordogne in southwestern France. Over 600 parietal wall paintings cover the interior walls and ceilings of ...

Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several p ...

era and its inhabitants became sedentary

Sedentary lifestyle is a lifestyle type, in which one is physically inactive and does little or no physical movement and or exercise. A person living a sedentary lifestyle is often sitting or lying down while engaged in an activity like soci ...

.

After strong demographic and agricultural development between the 4th and 3rd millennia, metallurgy appeared at the end of the 3rd millennium, initially working gold, copper and bronze, as well as later iron. France has numerous megalith

A megalith is a large stone that has been used to construct a prehistoric structure or monument, either alone or together with other stones. There are over 35,000 in Europe alone, located widely from Sweden to the Mediterranean sea.

The ...

ic sites from the Neolithic period, including the exceptionally dense Carnac stones site (approximately 3,300 BC).

Antiquity (6th century BC–5th century AD)

In 600 BC, Ionian

In 600 BC, Ionian Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, oth ...

from Phocaea

Phocaea or Phokaia (Ancient Greek: Φώκαια, ''Phókaia''; modern-day Foça in Turkey) was an ancient Ionian Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia. Greek colonists from Phocaea founded the colony of Massalia (modern-day Marseille, in ...

founded the colony

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state' ...

of Massalia (present-day Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Fra ...

), on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

. This makes it France's oldest city. At the same time, some Gallic Celtic tribes penetrated parts of Eastern and Northern France, gradually spreading through the rest of the country between the 5th and 3rd century BC. The concept of Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

emerged during this period, corresponding to the territories of Celtic settlement ranging between the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

, the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

, the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees (; es, Pirineos ; french: Pyrénées ; ca, Pirineu ; eu, Pirinioak ; oc, Pirenèus ; an, Pirineus) is a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. It extends nearly from its union with the Cantabrian Mountains to ...

and the Mediterranean. The borders of modern France roughly correspond to ancient Gaul, which was inhabited by Celtic ''Gauls''. Gaul was then a prosperous country, of which the southernmost part was heavily subject to Greek and Roman cultural and economic influences.

Around 390 BC, the Gallic

Around 390 BC, the Gallic chieftain

A tribal chief or chieftain is the leader of a tribal society or chiefdom.

Tribe

The concept of tribe is a broadly applied concept, based on tribal concepts of societies of western Afroeurasia.

Tribal societies are sometimes categorized a ...

Brennus

Brennus or Brennos is the name of two Gaulish chieftains, famous in ancient history:

* Brennus, chieftain of the Senones, a Gallic tribe originating from the modern areas of France known as Seine-et-Marne, Loiret, and Yonne; in 387 BC, in t ...

and his troops made their way to Italy through the Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Swi ...

, defeated the Romans in the Battle of the Allia

The Battle of the Allia was a battle fought between the Senones – a Gallic tribe led by Brennus, who had invaded Northern Italy – and the Roman Republic. The battle was fought at the confluence of the Tiber and Allia rivers, 11 Roman ...

, and besieged and ransomed Rome. The Gallic invasion left Rome weakened, and the Gauls continued to harass the region until 345 BC when they entered into a formal peace treaty with Rome. But the Romans and the Gauls would remain adversaries for the next centuries, and the Gauls would continue to be a threat in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

.

Around 125 BC, the south of Gaul was conquered by the Romans, who called this region ("Our Province"), which over time evolved into the name Provence

Provence (, , , , ; oc, Provença or ''Prouvènço'' , ) is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which extends from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the Italian border to the east; it is bor ...

in French. Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, ...

conquered the remainder of Gaul and overcame a revolt carried out by the Gallic chieftain Vercingetorix

Vercingetorix (; Greek: Οὐερκιγγετόριξ; – 46 BC) was a Gallic king and chieftain of the Arverni tribe who united the Gauls in a failed revolt against Roman forces during the last phase of Julius Caesar's Gallic Wars. Despite ha ...

in 52 BC.

Gaul was divided by Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

into Roman provinces.[Carpentier ''et al.'' 2000, pp. 53–55.] Many cities were founded during the Gallo-Roman period

Roman Gaul refers to GaulThe territory of Gaul roughly corresponds to modern-day France, Belgium and Luxembourg, and adjacient parts of the Netherlands, Switzerland and Germany. under provincial rule in the Roman Empire from the 1st century ...

, including Lugdunum

Lugdunum (also spelled Lugudunum, ; modern Lyon, France) was an important Roman city in Gaul, established on the current site of Lyon. The Roman city was founded in 43 BC by Lucius Munatius Plancus, but continued an existing Gallic settle ...

(present-day Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan language, Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, third-largest city and Urban area (France), second-largest metropolitan area of F ...

), which is considered the capital of the Gauls.[ These cities were built in traditional Roman style, with a forum, a ]theatre

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The perform ...

, a circus

A circus is a company of performers who put on diverse entertainment shows that may include clowns, acrobats, trained animals, trapeze acts, musicians, dancers, hoopers, tightrope walkers, jugglers, magicians, ventriloquists, and unicyclis ...

, an amphitheatre

An amphitheatre (British English) or amphitheater (American English; both ) is an open-air venue used for entertainment, performances, and sports. The term derives from the ancient Greek ('), from ('), meaning "on both sides" or "around" and ...

and thermal baths

A spa is a location where mineral-rich spring water (and sometimes seawater) is used to give medicinal baths. Spa towns or spa resorts (including hot springs resorts) typically offer various health treatments, which are also known as baln ...

. The Gauls mixed with Roman settlers and eventually adopted Roman culture and Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

speech (Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, from which the French language evolved). Roman polytheism

Religion in ancient Rome consisted of varying imperial and provincial religious practices, which were followed both by the people of Rome as well as those who were brought under its rule.

The Romans thought of themselves as highly religious, ...

merged with Gallic paganism into the same syncretism.

From the 250s to the 280s AD, Roman Gaul suffered a serious crisis with its fortified borders being attacked on several occasions by barbarians.[Carpentier et al. 2000, pp. 76–77] Nevertheless, the situation improved in the first half of the 4th century, which was a period of revival and prosperity for Roman Gaul. In 312, Emperor Constantine I

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to Constantine the Great and Christianity, convert to Christiani ...

converted to Christianity. Subsequently, Christians, who had been persecuted until then, increased rapidly across the entire Roman Empire. But, from the beginning of the 5th century, the Barbarian Invasions resumed. Teutonic tribes invaded the region from present-day Germany, the Visigoths

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is ...

settling in the southwest, the Burgundians along the Rhine River Valley, and the Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools, ...

(from whom the French take their name) in the north.

Early Middle Ages (5th–10th century)

At the end of the Antiquity period, ancient Gaul was divided into several Germanic kingdoms and a remaining Gallo-Roman territory, known as the Kingdom of Syagrius. Simultaneously, Celtic Britons, fleeing the

At the end of the Antiquity period, ancient Gaul was divided into several Germanic kingdoms and a remaining Gallo-Roman territory, known as the Kingdom of Syagrius. Simultaneously, Celtic Britons, fleeing the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain

The Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain is the process which changed the language and culture of most of what became England from Romano-British to Germanic. The Germanic-speakers in Britain, themselves of diverse origins, eventually develope ...

, settled in the western part of Armorica

Armorica or Aremorica (Gaulish: ; br, Arvorig, ) is the name given in ancient times to the part of Gaul between the Seine and the Loire that includes the Brittany Peninsula, extending inland to an indeterminate point and down the Atlantic Coast ...

. As a result, the Armorican peninsula was renamed Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period ...

, Celtic culture was revived and independent petty kingdom

A petty kingdom is a kingdom described as minor or "petty" (from the French 'petit' meaning small) by contrast to an empire or unified kingdom that either preceded or succeeded it (e.g. the numerous kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England unified into ...

s arose in this region.

The first leader to make himself king of all the Franks was Clovis I, who began his reign in 481, routing the last forces of the Roman governors of the province in 486. Clovis claimed that he would be baptised a Christian in the event of his victory against the Visigoths

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is ...

, which was said to have guaranteed the battle. Clovis regained the southwest from the Visigoths, was baptised in 508 and made himself master of what is now western Germany.

Clovis I was the first Germanic conqueror after the fall of the Roman Empire to convert to Catholic Christianity, rather than Arianism; thus France was given the title "Eldest daughter of the Church" (') by the papacy, and French kings would be called "the Most Christian Kings of France" (').

The Franks embraced the Christian Gallo-Roman culture and ancient Gaul was eventually renamed ''

The Franks embraced the Christian Gallo-Roman culture and ancient Gaul was eventually renamed ''Francia

Francia, also called the Kingdom of the Franks ( la, Regnum Francorum), Frankish Kingdom, Frankland or Frankish Empire ( la, Imperium Francorum), was the largest post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Franks dur ...

'' ("Land of the Franks"). The Germanic Franks adopted Romanic languages

The Romance languages, sometimes referred to as Latin languages or Neo-Latin languages, are the various modern languages that evolved from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic languages in the Indo-European language fa ...

, except in northern Gaul where Roman settlements were less dense and where Germanic languages

The Germanic languages are a branch of the Indo-European language family spoken natively by a population of about 515 million people mainly in Europe, North America, Oceania and Southern Africa. The most widely spoken Germanic language, E ...

emerged. Clovis made Paris his capital and established the Merovingian dynasty

The Merovingian dynasty () was the ruling family of the Franks from the middle of the 5th century until 751. They first appear as "Kings of the Franks" in the Roman army of northern Gaul. By 509 they had united all the Franks and northern Gauli ...

, but his kingdom would not survive his death. The Franks treated land purely as a private possession and divided it among their heirs, so four kingdoms emerged from that of Clovis: Paris, Orléans

Orléans (;["Orleans"](_blank)

(US) and [Soissons

Soissons () is a commune in the northern French department of Aisne, in the region of Hauts-de-France. Located on the river Aisne, about northeast of Paris, it is one of the most ancient towns of France, and is probably the ancient capital o ...]

, and Rheims

Reims ( , , ; also spelled Rheims in English) is the most populous city in the French department of Marne, and the 12th most populous city in France. The city lies northeast of Paris on the Vesle river, a tributary of the Aisne.

Founded by ...

. The last Merovingian kings lost power to their mayors of the palace (head of household). One mayor of the palace, Charles Martel

Charles Martel ( – 22 October 741) was a Frankish political and military leader who, as Duke and Prince of the Franks and Mayor of the Palace, was the de facto ruler of Francia from 718 until his death. He was a son of the Frankish statesm ...

, defeated an Umayyad invasion of Gaul

The Umayyad invasion of Gaul occurred in two phases in 719 and 732. Although the Umayyads secured control of Septimania, their incursions beyond this into the Loire and Rhône valleys failed. By 759 they had lost Septimania to the Christian ...

at the Battle of Tours

The Battle of Tours, also called the Battle of Poitiers and, by Arab sources, the Battle of tiles of Martyrs ( ar, معركة بلاط الشهداء, Maʿrakat Balāṭ ash-Shuhadā'), was fought on 10 October 732, and was an important battle ...

(732) and earned respect and power within the Frankish kingdoms. His son, Pepin the Short, seized the crown of Francia from the weakened Merovingians and founded the Carolingian dynasty

The Carolingian dynasty (; known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family named after Charlemagne, grandson of mayor Charles Martel and a descendant of the Arnulfing and Pippin ...

. Pepin's son, Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first ...

, reunited the Frankish kingdoms and built a vast empire across Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

and Central Europe.

Proclaimed Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Leo III and thus establishing in earnest the French Government's longtime historical association

The Historical Association is a membership organisation of historians and scholars founded in 1906 and based in London. Its goals are to support "the study and enjoyment of history at all levels by creating an environment that promotes lifelong lea ...

with the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

,[ See drop-down essay on "Religion and Politics until the French Revolution"] Charlemagne tried to revive the Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period ...

and its cultural grandeur. Charlemagne's son, Louis I Louis I may refer to:

* Louis the Pious, Louis I of France, "the Pious" (778–840), king of France and Holy Roman Emperor

* Louis I, Landgrave of Thuringia (ruled 1123–1140)

* Ludwig I, Count of Württemberg (c. 1098–1158)

* Louis I of Blois ...

(Emperor 814–840), kept the empire united; however, this Carolingian Empire would not survive his death. In 843, under the Treaty of Verdun

The Treaty of Verdun (), agreed in , divided the Frankish Empire into three kingdoms among the surviving sons of the emperor Louis I, the son and successor of Charlemagne. The treaty was concluded following almost three years of civil war and ...

, the empire was divided between Louis' three sons, with East Francia going to Louis the German

Louis the German (c. 806/810 – 28 August 876), also known as Louis II of Germany and Louis II of East Francia, was the first king of East Francia, and ruled from 843 to 876 AD. Grandson of emperor Charlemagne and the third son of Louis the P ...

, Middle Francia

Middle Francia ( la, Francia media) was a short-lived Frankish kingdom which was created in 843 by the Treaty of Verdun after an intermittent civil war between the grandsons of Charlemagne resulted in division of the united empire. Middle Franc ...

to Lothair I, and West Francia

In medieval history, West Francia (Medieval Latin: ) or the Kingdom of the West Franks () refers to the western part of the Frankish Empire established by Charlemagne. It represents the earliest stage of the Kingdom of France, lasting from about ...

to Charles the Bald

Charles the Bald (french: Charles le Chauve; 13 June 823 – 6 October 877), also known as Charles II, was a 9th-century king of West Francia (843–877), king of Italy (875–877) and emperor of the Carolingian Empire (875–877). After a ...

. West Francia approximated the area occupied by and was the precursor to, modern France.

During the 9th and 10th centuries, continually threatened by Viking invasions, France became a very decentralised state: the nobility's titles and lands became hereditary, and the authority of the king became more religious than secular and thus was less effective and constantly challenged by powerful noblemen. Thus was established feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structur ...

in France. Over time, some of the king's vassals would grow so powerful that they often posed a threat to the king. For example, after the Battle of Hastings

The Battle of Hastings nrf, Batâle dé Hastings was fought on 14 October 1066 between the Norman-French army of William, the Duke of Normandy, and an English army under the Anglo-Saxon King Harold Godwinson, beginning the Norman Conque ...

in 1066, William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first House of Normandy, Norman List of English monarchs#House of Norman ...

added "King of England" to his titles, becoming both the vassal to (as Duke of Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

) and the equal of (as king of England) the king of France, creating recurring tensions.

High and Late Middle Ages (10th–15th century)

The Carolingian dynasty ruled France until 987, when

The Carolingian dynasty ruled France until 987, when Hugh Capet

Hugh Capet (; french: Hugues Capet ; c. 939 – 14 October 996) was the King of the Franks from 987 to 996. He is the founder and first king from the House of Capet. The son of the powerful duke Hugh the Great and his wife Hedwige of Saxony, ...

, Duke of France and Count of Paris, was crowned King of the Franks. His descendantsthe Capetians, the House of Valois

The Capetian house of Valois ( , also , ) was a cadet branch of the Capetian dynasty. They succeeded the House of Capet (or "Direct Capetians") to the French throne, and were the royal house of France from 1328 to 1589. Junior members of the f ...

and the House of Bourbonprogressively unified the country through wars and dynastic inheritance into the Kingdom of France, which was fully declared in 1190 by Philip II of France

Philip II (21 August 1165 – 14 July 1223), byname Philip Augustus (french: Philippe Auguste), was King of France from 1180 to 1223. His predecessors had been known as kings of the Franks, but from 1190 onward, Philip became the first French m ...

(''Philippe Auguste''). Later kings would expand their directly possessed ''domaine royal'' to cover over half of modern continental France by the 15th century, including most of the north, centre and west of France. During this process, the royal authority became more and more assertive, centred on a hierarchically conceived society distinguishing nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The character ...

, clergy, and commoners

A commoner, also known as the ''common man'', ''commoners'', the ''common people'' or the ''masses'', was in earlier use an ordinary person in a community or nation who did not have any significant social status, especially a member of neither ...

.

The French nobility played a prominent role in most Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

to restore Christian access to the Holy Land. French knights made up the bulk of the steady flow of reinforcements throughout the two-hundred-year span of the Crusades, in such a fashion that the Arabs uniformly referred to the crusaders as ''Franj'' caring little whether they came from France.Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

, making French the base of the '' lingua franca'' (lit. "Frankish language") of the Crusader states.Cathars

Catharism (; from the grc, καθαροί, katharoi, "the pure ones") was a Christian dualist or Gnostic movement between the 12th and 14th centuries which thrived in Southern Europe, particularly in northern Italy and southern France. F ...

in the southwestern area of modern-day France. In the end, the Cathars were exterminated and the autonomous County of Toulouse was annexed into the crown lands of France

The crown lands, crown estate, royal domain or (in French) ''domaine royal'' (from demesne) of France were the lands, fiefs and rights directly possessed by the kings of France. While the term eventually came to refer to a territorial unit, the ...

.

From the 11th century, the House of Plantagenet, the rulers of the County of Anjou, succeeded in establishing its dominion over the surrounding provinces of

From the 11th century, the House of Plantagenet, the rulers of the County of Anjou, succeeded in establishing its dominion over the surrounding provinces of Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and ...

and Touraine

Touraine (; ) is one of the traditional provinces of France. Its capital was Tours. During the political reorganization of French territory in 1790, Touraine was divided between the departments of Indre-et-Loire, :Loir-et-Cher, Indre and Vien ...

, then progressively built an "empire" that spanned from England to the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees (; es, Pirineos ; french: Pyrénées ; ca, Pirineu ; eu, Pirinioak ; oc, Pirenèus ; an, Pirineus) is a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. It extends nearly from its union with the Cantabrian Mountains to ...

and covering half of modern France. Tensions between the kingdom of France and the Plantagenet empire would last a hundred years, until Philip II of France conquered, between 1202 and 1214, most of the continental possessions of the empire, leaving England and Aquitaine

Aquitaine ( , , ; oc, Aquitània ; eu, Akitania; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Aguiéne''), archaic Guyenne or Guienne ( oc, Guiana), is a historical region of southwestern France and a former administrative region of the country. Since 1 Janu ...

to the Plantagenets.

Charles IV the Fair died without an heir in 1328.Edward III of England

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring ...

. During the reign of Philip of Valois

Philip VI (french: Philippe; 1293 – 22 August 1350), called the Fortunate (french: le Fortuné, link=no) or the Catholic (french: le Catholique, link=no) and of Valois, was the first king of France from the House of Valois, reigning from 132 ...

, the French monarchy reached the height of its medieval power.Joan of Arc

Joan of Arc (french: link=yes, Jeanne d'Arc, translit= �an daʁk} ; 1412 – 30 May 1431) is a patron saint of France, honored as a defender of the French nation for her role in the siege of Orléans and her insistence on the coronat ...

and La Hire

Étienne de Vignolles, Sieur de Montmorillon, Chatelain de Longueville (), also known as La Hire (; 1390 – 11 January 1443), was a French military commander during the Hundred Years' War.

Nickname

One explanation for his nickname of La ...

, strong French counterattacks won back most English continental territories. Like the rest of Europe, France was struck by the Black Death due to which half of the 17 million population of France died.

Early modern period (15th century–1789)

The French Renaissance saw spectacular cultural development and the first standardisation of the French language, which would become the official language of France and the language of Europe's aristocracy. It also saw a long set of wars, known as the

The French Renaissance saw spectacular cultural development and the first standardisation of the French language, which would become the official language of France and the language of Europe's aristocracy. It also saw a long set of wars, known as the Italian Wars

The Italian Wars, also known as the Habsburg–Valois Wars, were a series of conflicts covering the period 1494 to 1559, fought mostly in the Italian peninsula, but later expanding into Flanders, the Rhineland and the Mediterranean Sea. The pr ...

, between France and the House of Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

. French explorers, such as Jacques Cartier or Samuel de Champlain, claimed lands in the Americas for France, paving the way for the expansion of the First French colonial empire. The rise of Protestantism in Europe led France to a civil war known as the French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion is the term which is used in reference to a period of civil war between French Catholics and Protestants, commonly called Huguenots, which lasted from 1562 to 1598. According to estimates, between two and four mi ...

, where, in the most notorious incident, thousands of Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

s were murdered in the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre of 1572. The Wars of Religion were ended by Henry IV's Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes () was signed in April 1598 by King Henry IV and granted the Calvinist Protestants of France, also known as Huguenots, substantial rights in the nation, which was in essence completely Catholic. In the edict, Henry aimed pr ...

, which granted some freedom of religion to the Huguenots. Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

troops, the terror of Western Europe, assisted the Catholic side during the Wars of Religion in 1589–1594, and invaded northern France in 1597; after some skirmishing in the 1620s and 1630s, Spain and France returned to all-out war between 1635 and 1659. The war cost France 300,000 casualties.

Under Louis XIII

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown ...

, the energetic Cardinal Richelieu promoted the centralisation of the state and reinforced the royal power by disarming domestic power holders in the 1620s. He systematically destroyed castles of defiant lords and denounced the use of private violence (duelling, carrying weapons and maintaining private armies). By the end of the 1620s, Richelieu established "the royal monopoly of force" as the doctrine. During Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Ver ...

's minority and the regency of Queen Anne and Cardinal Mazarin

Cardinal Jules Mazarin (, also , , ; 14 July 1602 – 9 March 1661), born Giulio Raimondo Mazzarino () or Mazarini, was an Italian cardinal, diplomat and politician who served as the chief minister to the Kings of France Louis XIII and Louis X ...

, a period of trouble known as the Fronde

The Fronde () was a series of civil wars in France between 1648 and 1653, occurring in the midst of the Franco-Spanish War, which had begun in 1635. King Louis XIV confronted the combined opposition of the princes, the nobility, the law cour ...

occurred in France. This rebellion was driven by the great feudal lords and sovereign court

A ''parlement'' (), under the French Ancien Régime, was a provincial appellate court of the Kingdom of France. In 1789, France had 13 parlements, the oldest and most important of which was the Parlement of Paris. While both the modern Fr ...

s as a reaction to the rise of royal absolute power in France.

The monarchy reached its peak during the 17th century and the reign of Louis XIV (1643–1715). By turning powerful feudal lords into

The monarchy reached its peak during the 17th century and the reign of Louis XIV (1643–1715). By turning powerful feudal lords into courtier

A courtier () is a person who attends the royal court of a monarch or other royalty. The earliest historical examples of courtiers were part of the retinues of rulers. Historically the court was the centre of government as well as the official ...

s at the Palace of Versailles, military-integrated command unchallenged. Remembered for his numerous wars, he made France the leading European power. France became the most populous country in Europe and had tremendous influence over European politics, economy, and culture. French became the most-used language in diplomacy, science, literature and international affairs, and remained so until the 20th century.Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached ...

(r. 1715–1774), France lost New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

and most of its Indian possessions after its defeat in the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (175 ...

(1756–1763). Its European territory kept growing, however, with notable acquisitions such as Lorraine

Lorraine , also , , ; Lorrain: ''Louréne''; Lorraine Franconian: ''Lottringe''; german: Lothringen ; lb, Loutrengen; nl, Lotharingen is a cultural and historical region in Northeastern France, now located in the administrative region of Gra ...

(1766) and Corsica (1770). An unpopular king, Louis XV's weak rule, his ill-advised financial, political and military decisions – as well as the debauchery of his court– discredited the monarchy, which arguably paved the way for the French Revolution 15 years after his death.

Louis XVI

Louis XVI (''Louis-Auguste''; ; 23 August 175421 January 1793) was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. He was referred to as ''Citizen Louis Capet'' during the four months just before he was ...

(r. 1774–1793), actively supported the Americans with money, fleets and armies, helping them win independence from Great Britain. France gained revenge but spent so heavily that the government verged on bankruptcy—a factor that contributed to the French Revolution. Some of the Enlightenment occurred in French intellectual circles, and major scientific breakthroughs and inventions, such as the discovery of oxygen (1778) and the first hot air balloon carrying passengers (1783), were achieved by French scientists. French explorers, such as Bougainville and Lapérouse, took part in the voyages of scientific exploration through maritime expeditions around the globe. The Enlightenment philosophy, in which reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, ...

is advocated as the primary source of legitimacy

Legitimacy, from the Latin ''legitimare'' meaning "to make lawful", may refer to:

* Legitimacy (criminal law)

* Legitimacy (family law)

* Legitimacy (political)

See also

* Bastard (law of England and Wales)

* Illegitimacy in fiction

* Legit (d ...

, undermined the power of and support for the monarchy and also was a factor in the French Revolution.

Revolutionary France (1789–1799)

Facing financial troubles, King

Facing financial troubles, King Louis XVI

Louis XVI (''Louis-Auguste''; ; 23 August 175421 January 1793) was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. He was referred to as ''Citizen Louis Capet'' during the four months just before he was ...

summoned the Estates-General (gathering the three Estates of the realm

The estates of the realm, or three estates, were the broad orders of social hierarchy used in Christendom (Christian Europe) from the Middle Ages to early modern Europe. Different systems for dividing society members into estates developed an ...

) in May 1789 to propose solutions to his government. As it came to an impasse, the representatives of the Third Estate

The estates of the realm, or three estates, were the broad orders of social hierarchy used in Christendom (Christian Europe) from the Middle Ages to early modern Europe. Different systems for dividing society members into estates developed and ...

formed a National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the rep ...

, signaling the outbreak of the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

. Fearing that the king would suppress the newly created National Assembly, insurgents stormed the Bastille on 14 July 1789, a date which would become France's National Day.

In early August 1789, the National Constituent Assembly abolished the privileges of the nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The character ...

such as personal serfdom and exclusive hunting rights. Through the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (french: Déclaration des droits de l'homme et du citoyen de 1789, links=no), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human civil rights document from the French Revolu ...

(27 August 1789), France established fundamental rights for men. The Declaration affirms "the natural and imprescriptible rights of man" to "liberty, property, security and resistance to oppression". Freedom of speech and press were declared, and arbitrary arrests were outlawed. It called for the destruction of aristocratic privileges and proclaimed freedom and equal rights for all men, as well as access to public office based on talent rather than birth. In November 1789, the Assembly decided to nationalise and sell all property of the Catholic Church which had been the largest landowner in the country. In July 1790, a Civil Constitution of the Clergy reorganised the French Catholic Church, cancelling the authority of the Church to levy taxes, et cetera. This fueled much discontent in parts of France, which would contribute to the civil war breaking out some years later. While King Louis XVI still enjoyed popularity among the population, his disastrous flight to Varennes (June 1791) seemed to justify rumours he had tied his hopes of political salvation to the prospects of foreign invasion. His credibility was so deeply undermined that the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of a republic became an increasing possibility.

In August 1791, the Emperor of Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

and the King of Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

in the Declaration of Pillnitz

The Declaration of Pillnitz was a statement of five sentences issued on 27 August 1791 at Pillnitz Castle near Dresden (Saxony) by Frederick William II of Prussia and the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II who was Marie Antoinette's broth ...

threatened revolutionary France to intervene by force of arms to restore the French absolute monarchy. In September 1791, the National Constituent Assembly forced King Louis XVI to accept the French Constitution of 1791, thus turning the French absolute monarchy into a constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

. In the newly established Legislative Assembly (October 1791), enmity developed and deepened between a group, later called the ' Girondins', who favoured war with Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

and Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

, and a group later called 'Montagnards

Montagnard (''of the mountain'' or ''mountain dweller'') may refer to:

* Montagnard (French Revolution), members of The Mountain (''La Montagne''), a political group during the French Revolution (1790s)

** Montagnard (1848 revolution), members of t ...

' or ' Jacobins', who opposed such a war. A majority in the Assembly

Assembly may refer to:

Organisations and meetings

* Deliberative assembly, a gathering of members who use parliamentary procedure for making decisions

* General assembly, an official meeting of the members of an organization or of their representa ...

in 1792 however saw a war with Austria and Prussia as a chance to boost the popularity of the revolutionary government and thought that France would win a war against those gathered monarchies. On 20 April 1792, therefore, they declared war on Austria.

On 10 August 1792, an angry crowd threatened the palace of King Louis XVI, who took refuge in the Legislative Assembly.

On 10 August 1792, an angry crowd threatened the palace of King Louis XVI, who took refuge in the Legislative Assembly.[ A Prussian Army invaded France later in August 1792. In early September, Parisians, infuriated by the Prussian Army capturing Verdun and counter-revolutionary uprisings in the west of France, murdered between 1,000 and 1,500 prisoners by raiding the Parisian prisons. The ]Assembly

Assembly may refer to:

Organisations and meetings

* Deliberative assembly, a gathering of members who use parliamentary procedure for making decisions

* General assembly, an official meeting of the members of an organization or of their representa ...

and the Paris City Council seemed unable to stop that bloodshed.[ The ]National Convention

The National Convention (french: link=no, Convention nationale) was the parliament of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for the rest of its existence during the French Revolution, following the two-year Nationa ...

, chosen in the first elections under male universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political stan ...