The Fatimid Caliphate was an

Ismaili Shi'a caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of

North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the

Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

in the east. The

Fatimids, a dynasty of Arab origin, trace their ancestry to Muhammad's daughter

Fatima and her husband

‘Ali b. Abi Talib, the first

Shi‘a imam. The Fatimids were acknowledged as the rightful imams by different

Isma‘ili communities, but also in many other Muslim lands, including

Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

and the adjacent regions. Originating during the

Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

, the Fatimids conquered

Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

and established the city of "

al-Mahdiyya" ( ar, المهدية). The Ismaili dynasty ruled territories across the

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western Europe, Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa ...

coast of Africa and ultimately made

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

the center of the caliphate. At its height, the caliphate included – in addition to Egypt – varying areas of the

Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ar, الْمَغْرِب, al-Maghrib, lit=the west), also known as the Arab Maghreb ( ar, المغرب العربي) and Northwest Africa, is the western part of North Africa and the Arab world. The region includes Algeria, ...

,

Sudan,

Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, the

Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

, and the

Hijaz

The Hejaz (, also ; ar, ٱلْحِجَاز, al-Ḥijāz, lit=the Barrier, ) is a region in the west of Saudi Arabia. It includes the cities of Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, Tabuk, Yanbu, Taif, and Baljurashi. It is also known as the "Western Provi ...

.

Between 902 to 909 the foundation of the Fatimid state was realized by the

Kutama

The Kutama ( Berber: ''Ikutamen''; ar, كتامة) was a Berber tribe in northern Algeria classified among the Berber confederation of the Bavares. The Kutama are attested much earlier, in the form ''Koidamousii'' by the Greek geographer Ptolemy. ...

Berbers, under the leadership of the ''

da'i'' (missionary)

Abu Abdallah, whose conquest of

Ifriqiya paved the way for the establishment of the Caliphate.

After this conquest,

Abdallah al-Mahdi Billah was retrieved from

Sijilmasa and then accepted as the Imam of the movement, becoming the first Caliph and founder of the ruling dynasty in 909.

In 921, the city of

al-Mahdiyya was established as the capital. In 948, they shifted their capital to

al-Mansuriyya, near

Kairouan

Kairouan (, ), also spelled El Qayrawān or Kairwan ( ar, ٱلْقَيْرَوَان, al-Qayrawān , aeb, script=Latn, Qeirwān ), is the capital of the Kairouan Governorate in Tunisia and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The city was founded by t ...

. In 969, during the reign of

al-Mu'izz

Abu Tamim Ma'ad al-Muizz li-Din Allah ( ar, ابو تميم معد المعزّ لدين الله, Abū Tamīm Maʿad al-Muʿizz li-Dīn Allāh, Glorifier of the Religion of God; 26 September 932 – 19 December 975) was the fourth Fatimid calip ...

, they conquered

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

, and in 973 the caliphate was moved to the new capital of

Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the Capital city, capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, List of ...

. Egypt became the political, cultural, and religious centre of their empire, which developed a new and "indigenous Arabic" culture.

After its initial conquests, the caliphate often allowed a degree of religious tolerance towards non-Shia sects of

Islam, as well as to

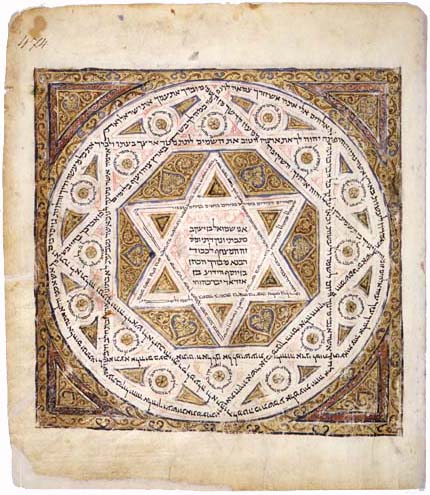

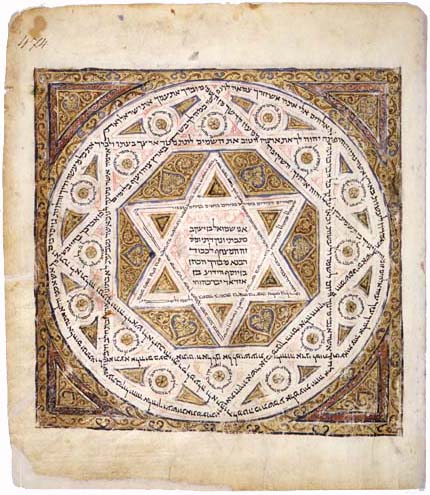

Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

and

Christians

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words '' Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρ ...

. However, its

leader

Leadership, both as a research area and as a practical skill, encompasses the ability of an individual, group or organization to "lead", influence or guide other individuals, teams, or entire organizations. The word "leadership" often gets vi ...

s made little headway in persuading the Egyptian population to adopt its religious beliefs.

After the reigns of al-'Aziz and al-Hakim, the long reign of al-Mustansir entrenched a regime in which the caliph remained aloof from state affairs and

vizier

A vizier (; ar, وزير, wazīr; fa, وزیر, vazīr), or wazir, is a high-ranking political advisor or minister in the near east. The Abbasid caliphs gave the title ''wazir'' to a minister formerly called '' katib'' (secretary), who was ...

s took on greater importance. Political and ethnic factionalism within the army led to a civil war in the 1060s which threatened the empire's survival. After a period of revival during the tenure of the vizier

Badr al-Jamali

Abū'l-Najm Badr ibn ʿAbdallāh al-Jamālī al-Mustanṣirī, better known as Badr al-Jamali ( ar, بدر الجمالى) was an Armenian Shia Muslim Fatimid vizier, and prominent statesman for the Fatimid Caliphate under Caliph al-Mustansir. H ...

(d. 1094), the Fatimid caliphate declined rapidly during the late eleventh and twelfth centuries. In addition to internal difficulties, the caliphate was weakened by the encroachment of the

Seljuk Turks

The Seljuk dynasty, or Seljukids ( ; fa, سلجوقیان ''Saljuqian'', alternatively spelled as Seljuqs or Saljuqs), also known as Seljuk Turks, Seljuk Turkomans "The defeat in August 1071 of the Byzantine emperor Romanos Diogenes

by the Turk ...

into

Syria in the 1070s and the arrival of the

Crusaders

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were in ...

in the

Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

after 1098. In 1171,

Saladin

Yusuf ibn Ayyub ibn Shadi () ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known by the epithet Saladin,, ; ku, سهلاحهدین, ; was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from an ethnic Kurdish family, he was the first of both Egypt and ...

abolished the dynasty's rule and founded the

Ayyubid dynasty, which incorporated Egypt into the nominal sphere of authority of the .

Name

The

Fatimid dynasty

The Fatimid dynasty () was an Isma'ili Shi'a dynasty of Arab descent that ruled an extensive empire, the Fatimid Caliphate, between 909 and 1171 CE. Claiming descent from Fatima and Ali, they also held the Isma'ili imamate, claiming to be the r ...

claimed descent from

Fatimah

Fāṭima bint Muḥammad ( ar, فَاطِمَة ٱبْنَت مُحَمَّد}, 605/15–632 CE), commonly known as Fāṭima al-Zahrāʾ (), was the daughter of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and his wife Khadija. Fatima's husband was Ali, ...

, the daughter of the

Islamic prophet Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mo ...

. The dynasty legitimized its claim through descent from Muhammad by way of his daughter and her husband

Ali

ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib ( ar, عَلِيّ بْن أَبِي طَالِب; 600 – 661 CE) was the last of four Rightly Guided Caliphs to rule Islam (r. 656 – 661) immediately after the death of Muhammad, and he was the first Shia Imam ...

, the first

Shī'a Imām, hence the dynasty's name ''fāṭimiyy'' (), the Arabic

relative adjective for "Fāṭima".

Emphasizing its

Alid descent, the dynasty named itself simply as the 'Alid dynasty' (), but many hostile

Sunni sources only refer to them as the 'Ubaydids' (), after the diminutive form Ubayd Allah for the name of the first Fatimid caliph.

History

Origins

The Fatimid dynasty came to power as the leaders of

Isma'ilism

Isma'ilism ( ar, الإسماعيلية, al-ʾIsmāʿīlīyah) is a branch or sub-sect of Shia Islam. The Isma'ili () get their name from their acceptance of Imam Isma'il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor (imām) to Ja'far al-S ...

, a revolutionary

Shi'a movement "which was at the same time political and religious, philosophical and social", and which originally proclaimed nothing less than the arrival of an Islamic

messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of '' mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach ...

. The origins of that movement, and of the dynasty itself, are obscure prior to the late ninth century.

The

Fatimids rulers were Arab in origin, starting with its founder the

Isma'ili

Isma'ilism ( ar, الإسماعيلية, al-ʾIsmāʿīlīyah) is a branch or sub-sect of Shia Islam. The Isma'ili () get their name from their acceptance of Imam Isma'il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor ( imām) to Ja'far al- ...

Shia

Caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

Abdallah al-Mahdi Billah. Their military were from

Kabylia

Kabylia ('' Kabyle: Tamurt n Leqbayel'' or ''Iqbayliyen'', meaning "Land of Kabyles", '','' meaning "Land of the Tribes") is a cultural, natural and historical region

Historical regions (or historical areas) are geographical regions which ...

in

Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

, several historians attribute the military creation/establishment and its origin to the Kutama Berbers.

Early Shi'ism and the roots of Isma'ilism

The Shi'a opposed the

Umayyad

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by the ...

and

Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

caliphates, whom they considered usurpers. Instead, they believed in the exclusive right of the descendants of

Ali

ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib ( ar, عَلِيّ بْن أَبِي طَالِب; 600 – 661 CE) was the last of four Rightly Guided Caliphs to rule Islam (r. 656 – 661) immediately after the death of Muhammad, and he was the first Shia Imam ...

through Muhammad's daughter,

Fatima, to lead the Muslim community. This manifested itself in a line of

imams

Imam (; ar, إمام '; plural: ') is an Islamic leadership position. For Sunni Muslims, Imam is most commonly used as the title of a worship leader of a mosque. In this context, imams may lead Islamic worship services, lead prayers, serve ...

, descendants of Ali via

al-Husayn

Abū ʿAbd Allāh al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib ( ar, أبو عبد الله الحسين بن علي بن أبي طالب; 10 January 626 – 10 October 680) was a grandson of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a son of Ali ibn Abi ...

, whom their followers considered as the true representatives of God on earth. At the same time, there was a widespread messianic tradition in Islam concerning the appearance of a ("the Rightly Guided One") or ("He Who Arises"), who would restore true Islamic government and justice and usher in the

end times

Eschatology (; ) concerns expectations of the end of the present age, human history, or of the world itself. The end of the world or end times is predicted by several world religions (both Abrahamic and non-Abrahamic), which teach that nega ...

. This figure was widely expectednot just among the Shi'ato be a descendant of Ali. Among Shi'a, however, this belief became a core tenet of their faith, and was applied to several Shi'a leaders who were killed or died; their followers believed that they had gone into "

occultation

An occultation is an event that occurs when one object is hidden from the observer by another object that passes between them. The term is often used in astronomy, but can also refer to any situation in which an object in the foreground blocks ...

" () and would return (or be resurrected) at the appointed time.

These traditions manifested themselves in the succession of the sixth imam,

Ja'far al-Sadiq

Jaʿfar ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAlī al-Ṣādiq ( ar, جعفر بن محمد الصادق; 702 – 765 CE), commonly known as Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq (), was an 8th-century Shia Muslim scholar, jurist, and theologian.. He was the founder of th ...

. Al-Sadiq had appointed his son

Isma'il ibn Ja'far

Abū Muḥammad Ismāʿīl ibn Jaʿfar al-Mubārak ( ar, إسماعيل بن جعفر; c.719 AD – c.762 AD) was the eldest son of Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq. He is also known as Isma'il al-Ãraj ibn Ja'far al-Sadiq (اسماعيل الاعرج ...

as his successor, but Isma'il died before his father, and when al-Sadiq himself died in 765, the succession was left open. Most of his followers followed al-Sadiq's son

Musa al-Kazim

Musa ibn Ja'far al-Kazim ( ar, مُوسَىٰ ٱبْن جَعْفَر ٱلْكَاظِم, Mūsā ibn Jaʿfar al-Kāẓim), also known as Abū al-Ḥasan, Abū ʿAbd Allāh or Abū Ibrāhīm, was the seventh Imam in Twelver Shia Islam, after ...

down to a

twelfth and final imam who supposedly went into occultation in 874 and would one day return as the . This branch is hence known as the "Twelvers". Others followed other sons, or even refused to believe that al-Sadiq had died, and expected his return as the . Another branch believed that Ja'far was followed by a seventh imam, who had gone into occultation and would one day return; hence this party is known as the "Seveners". The exact identity of that seventh imam was disputed, but by the late ninth century had commonly been identified with

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mo ...

, son of Isma'il and grandson of al-Sadiq. From Muhammad's father, Isma'il, the sect, which gave rise to the Fatimids, receives its name of "Isma'ili". Due to the harsh Abbasid persecution of the Alids, the Ismaili Imams went into hiding and neither Isma'il's nor Muhammad's lives are well known, and after Muhammad's death during the reign of

Harun al-Rashid

Abu Ja'far Harun ibn Muhammad al-Mahdi ( ar

, أبو جعفر هارون ابن محمد المهدي) or Harun ibn al-Mahdi (; or 766 – 24 March 809), famously known as Harun al-Rashid ( ar, هَارُون الرَشِيد, translit=Hārūn ...

(), the history of the early Isma'ili movement becomes obscure.

The secret network

While the awaited Muhammad ibn Isma'il remained hidden, however, he would need to be represented by agents, who would gather the faithful, spread the word (, "invitation, calling"), and prepare his return. The head of this secret network was the living proof of the imam's existence, or "seal" (). It is this role that the ancestors of the Fatimids are first documented. The first known ''ḥujja'' was a certain Abdallah al-Akbar ("Abdallah the Elder"), a wealthy merchant from

Khuzestan, who established himself at the small town of

Salamiya

A full view of Shmemis (spring 1995)

Salamieh ( ar, سلمية ') is a city and district in western Syria, in the Hama Governorate. It is located southeast of Hama, northeast of Homs. The city is nicknamed the "mother of Cairo" because it wa ...

on the western edge of the

Syrian Desert. Salamiya became the centre of the Isma'ili , with Abdallah al-Akbar being succeeded by his son and grandson as the secret "grand masters" of the movement.

In the last third of the ninth century, the Isma'ili spread widely, profiting from the collapse of Abbasid power in the

Anarchy at Samarra

The Anarchy at Samarra () was a period of extreme internal instability from 861 to 870 in the history of the Abbasid Caliphate, marked by the violent succession of four caliphs, who became puppets in the hands of powerful rival military groups.

T ...

and the subsequent

Zanj Revolt, as well as from dissatisfaction among Twelver adherents with the

political quietism of their leadership and the recent disappearance of the twelfth imam. Missionaries (s) such as

Hamdan Qarmat

Hamdan Qarmat ibn al-Ash'ath ( ar, حمدان قرمط بن الأشعث, Ḥamdān Qarmaṭ ibn al-Ashʿath; CE) was a Persian ruler and the eponymous founder of the Qarmatian sect of Isma'ilism. Originally the chief Isma'ili missionary () in ...

and

Ibn Hawshab

Abu'l-Qāsim al-Ḥasan ibn Faraj ibn Ḥawshab ibn Zādān al-Najjār al-Kūfī ( ar, أبو القاسم الحسن ابن فرج بن حوشب زاذان النجار الكوفي ; died 31 December 914), better known simply as Ibn Ḥawshab, ...

spread the network of agents to the area round

Kufa

Kufa ( ar, الْكُوفَة ), also spelled Kufah, is a city in Iraq, about south of Baghdad, and northeast of Najaf. It is located on the banks of the Euphrates River. The estimated population in 2003 was 110,000. Currently, Kufa and Najaf a ...

in the late 870s, and from there to

Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

(882) and thence India (884),

Bahrayn

Bahrain ( ; ; ar, البحرين, al-Bahrayn, locally ), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, ' is an island country in Western Asia. It is situated on the Persian Gulf, and comprises a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and an ad ...

(899),

Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, and the

Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ar, الْمَغْرِب, al-Maghrib, lit=the west), also known as the Arab Maghreb ( ar, المغرب العربي) and Northwest Africa, is the western part of North Africa and the Arab world. The region includes Algeria, ...

(893).

The Qarmatian schism and its aftermath

In 899, Abdallah al-Akbar's great-grandson,

Abdallah, became the new head of the movement, and introduced a radical change in the doctrine: no longer was he and his forebears merely the stewards for Muhammad ibn Isma'il, but they were declared to be the rightful imams, and Abdallah himself was the awaited . Various genealogies were later put forth by the Fatimids to justify this claim by proving their descent from Isma'il ibn Ja'far, but even in pro-Isma'ili sources, the succession and names of imams differ, while

Sunni and Twelver sources of course reject any Fatimid descent from the Alids altogether and consider them impostors. Abdallah's claim caused a rift in the Isma'ili movement, as Hamdan Qarmat and other leaders denounced this change and held onto the original doctrine, becoming known as the "

Qarmatians", while other communities remained loyal to Salamiya. Shortly after, in 902–903, pro-Fatimid loyalists began a great uprising in

Syria. The large-scale Abbasid reaction it precipitated and the attention it brought on him, forced Abdallah to abandon Salamiya for Palestine, Egypt, and finally for the

Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ar, الْمَغْرِب, al-Maghrib, lit=the west), also known as the Arab Maghreb ( ar, المغرب العربي) and Northwest Africa, is the western part of North Africa and the Arab world. The region includes Algeria, ...

, where the

Abu Abdallah al-Shi'i

Al-Husayn ibn Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Zakariyya, better known as Abu Abdallah al-Shi'i ( ar, ابو عبد الله الشيعي, Abū ʿAbd Allāh ash-Shi'ī), was an Isma'ili missionary ('' dāʿī'') active in Yemen and North Africa, mainly amon ...

had made great headway in converting the

Kutama

The Kutama ( Berber: ''Ikutamen''; ar, كتامة) was a Berber tribe in northern Algeria classified among the Berber confederation of the Bavares. The Kutama are attested much earlier, in the form ''Koidamousii'' by the Greek geographer Ptolemy. ...

Berbers to the Isma'ili cause. Unable to join his directly, Abdallah instead settled at

Sijilmasa sometime between 904 and 905.

Rise to power

Establishment of the Isma'ili State

Prior to the Fatimid rise to power, a large part of the Maghreb including

Ifriqiya was under the control of the

Aghlabids

The Aghlabids ( ar, الأغالبة) were an Arab dynasty of emirs from the Najdi tribe of Banu Tamim, who ruled Ifriqiya and parts of Southern Italy, Sicily, and possibly Sardinia, nominally on behalf of the Abbasid Caliph, for about a c ...

, an Arab dynasty who ruled nominally on behalf the Abbasids but were ''de facto'' independent. In 893 the Abu Abdallah al-Shi'i first settled among the Banu Saktan tribe (part of the larger Kutama tribe) in

Ikjan, near the city of

Mila (in northwestern Algeria today). However, due to hostility from the local Aghlabid authorities and other Kutuma tribes, he was forced to leave Ikjan and sought the protection of another Kutama tribe, the Banu Ghashman, in Tazrut (two miles southwest of Mila). From there, he began to build support for a new movement. Shortly after, the hostile Kutama tribes and the Arab lords of the nearby cities (Mila,

Setif, and

Bilizma) allied together to march against him, but he was able to move quickly and muster enough support from friendly Kutama to defeat them one by one before they were able to unite. This first victory brought Abu Abdallah and his Kutama troops valuable loot and attracted more support to the 's cause. Over the next two years Abu Abdallah was able to win over most of the Kutama tribes in the region through either persuasion or coercion. This left much of the countryside under his control, while the major cities remained under Aghlabid control. He established an Isma'ili theocratic state based in Tazrut, operating in a way similar to previous Isma'ili missionary networks in Mesopotamia but adapted to local Kutama tribal structures. He adopted the role of a traditional Islamic ruler at the head of this organization while remaining in frequent contact with Abdallah. He continued to preach to his followers, known as the ''Awliya' Allah'' ('Friends of God'), and to initiate them into Isma'ili doctrine.

Conquest of Aghlabid Ifriqiya

In 902, while the Aghlabid emir

Ibrahim II was away on campaign in

Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, Abu Abdallah struck the first significant blow against Aghlabid authority in

North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

by attacking and capturing the city of Mila for the first time. This news triggered a serious response from the Aghlabids, who sent a punitive expedition of 12,000 men from Tunis in October of the same year. Abu Abdallah's forces were unable to resist this counterattack and after two defeats they evacuated Tazrut (which was largely unfortified) and fled to Ikjan, leaving Mila to be retaken. Ikjan became the new center of the Fatimid movement and the reestablished his network of missionaries and spies.

Ibrahim II died in October 902 while in

southern Italy and was succeeded by

Abdallah II. In early 903 Abdallah II set out on another expedition to destroy Ikjan and the Kutama rebels, but he ended the expedition prematurely due to troubles at home arising from disputes over his succession. On 27 July 903 he was assassinated and his son

Ziyadat Allah III

Abu Mudhar Ziyadat Allah III ( ar, أبو مضر زيادة الله الثالث) (died 911–916) was the eleventh and last Emir of the Aghlabids in Ifriqiya (903–909).

He came to power after the murder of his father Abdallah II on 27 Ju ...

took power in Tunis. These internal Aghlabid troubles gave Abu Abdallah the opportunity to recapture Mila and then go on to capture Setif, another fortified city, by October or November 904. In 905 the Aghlabids sent a third expedition to try and subdue the Kutama. They based themselves in

Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

*Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given name ...

and in the fall of 905, after receiving further reinforcements, set out to march against Abu Abdallah. However, they were surprised by Kutama forces on the first day of their march, which caused a panic and scattered their army. The Aghlabid general fled and the Kutama captured a large booty. Another Aghlabid military expedition organized the next year (906) failed when the soldiers mutinied. Around the same time or soon after, Abu Abdallah's forces besieged and captured the fortified cities of

Tubna

Tubna ( ar, تبنة, also spelled ''Tibna'' or ''Tebnah'') is a village in southern Syria, administratively part of the Daraa Governorate in the Hauran region. It is located 58 km south Damascus and 42 km from Daraa.

History

Tubna w ...

and Bilizma. The capture of Tubna was significant as it was the first major commercial center to come under Abu Abdallah's control.

Meanwhile, Ziyadat Allah III moved his court from Tunis to

Raqqada

Raqqāda ( ar, رقّادة) is the site of the second capital of the 9th-century dynasty of Aghlabids, located about ten kilometers southwest of Kairouan, Tunisia. The site now houses the National Museum of Islamic Art.

History

In 876, the ni ...

, the palace-city near

Kairouan

Kairouan (, ), also spelled El Qayrawān or Kairwan ( ar, ٱلْقَيْرَوَان, al-Qayrawān , aeb, script=Latn, Qeirwān ), is the capital of the Kairouan Governorate in Tunisia and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The city was founded by t ...

, in response to the growing threat. He fortified Raqqada in 907. In early 907 another Aghlabid army marched eastwards again against Abu Abdallah, accompanied by Berber reinforcements from the

Aurès Mountains. They were again scattered by Kutama cavalry and retreated to

Baghaya, the most fortified town on the old southern Roman road between Ifriqiya and the central Maghreb. The fortress, however, fell to the Kutama without a siege when local notables arranged to have the gates opened to them in May or June 907. This opened a hole in the wider defensive system of Ifriqiya and created panic in Raqqada. Ziyadat Allah III stepped up anti-Fatimid propaganda, recruited volunteers, and took measures to defend the weakly-fortified city of Kairouan. He spent the winter of 907–908 with his army in al-Aribus (

Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

-era Laribus, between present-day

El Kef

El Kef ( ar, الكاف '), also known as ''Le Kef'', is a city in northwestern Tunisia. It serves as the capital of the Kef Governorate.

El Kef is situated to the west of Tunis and some east of the border between Algeria and Tunisia. It has a ...

and

Maktar), expecting an attack from the north. However, Abu Abdallah's forces had been unable to capture the northerly city of Constantine and therefore they instead attacked along the southern road from Baghaya in early 908 and captured

Maydara (present-day Haïdra). An indecisive battle subsequently occurred between the Aghalabid and Kutama armies near Dar Madyan (probably a site between

Sbeitla

Sbeitla or Sufetula ( ber, Sbitla or Seftula, ar, سبيطلة ') is a small town in west-central Tunisia. Nearby are the Byzantine ruins of Sufetula, containing the best preserved Byzantine forum temples in Tunisia. It was the entry point of the ...

and

Kasserine

Kasserine ( ar, القصرين, al-Qasrīn, Tunisian Arabic: ڨصرين ') is the capital city of the Kasserine Governorate, in west-central Tunisia. It is situated below Jebel ech Chambi ( جبل الشعانبي), Tunisia's highest mountain. ...

), with neither side gaining the upper hand. During the winter of 908–909 Abu Abdallah campaigned in the region around

Chott el-Jerid, capturing the towns of

Tuzur (Tozeur),

Nafta, and

Qafsa (Gafsa) and taking control of the region. The Aghlabids responded by besieging Baghaya soon afterward in the same winter, but they were quickly repelled.

On 25 February 909, Abu Abdallah set out from Ikjan with an army of 200,000 men for a final invasion of Kairouan. The remaining Aghlabid army, led by an Aghlabid prince named Ibrahim Ibn Abi al-Aghlab, met them near al-Aribus on 18 March. The battle lasted until the afternoon, when a contingent of Kutama horsemen managed to outflank the Aghlabid army and finally caused a rout. When news of the defeat reached Raqqada, Ziyadat Allah III packed his valuable treasures and fled towards Egypt. The population of Kairouan looted the abandoned palaces of Raqqada and resisted Ibn Abi al-Aghlab's calls to organise a last-ditch resistance. Upon hearing of the looting, Abu Abdallah sent an advance force of Kutama horsemen who secured Raqqada on 24 March. On 25 March 909 (Saturday, 1

Rajab

Rajab ( ar, رَجَب) is the seventh month of the Islamic calendar. The lexical definition of the classical Arabic verb ''rajaba'' is "to respect" which could also mean "be awe or be in fear", of which Rajab is a derivative.

This month is re ...

296), Abu Abdallah himself entered Raqqada and took up residence here.

Establishment of the Caliphate

Upon assuming power in Raqqada, Abu Abdallah inherited much of the Aghlabid state's apparatus and allowed its former officials to continue working for the new regime. He established a new, Isma'ili Shi'a regime on behalf of his absent, and for the moment unnamed, master. He then led his army west to Sijilmasa, whence he led Abdallah in triumph to Raqqada, which he entered on 15 January 910. There Abdallah publicly proclaimed himself as

caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

with the

regnal name

A regnal name, or regnant name or reign name, is the name used by monarchs and popes during their reigns and, subsequently, historically. Since ancient times, some monarchs have chosen to use a different name from their original name when they ...

of , and presented his son and heir, with the regnal name of

al-Qa'im. Al-Mahdi quickly fell out with Abu Abdallah: not only was the over-powerful, but he demanded proof that the new caliph was the true . The elimination of Abu Abdallah al-Shi'i and his brother led to an uprising among the Kutama, led by a child-, which was suppressed. At the same time, al-Mahdi repudiated the millenarian hopes of his followers and curtailed their

antinomian

Antinomianism (Ancient Greek: ἀντί 'anti''"against" and νόμος 'nomos''"law") is any view which rejects laws or legalism and argues against moral, religious or social norms (Latin: mores), or is at least considered to do so. The term ha ...

tendencies.

The new regime regarded its presence in Ifriqiya as only temporary: the real target was

Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon. I ...

, the capital of the Fatimids' Abbasid rivals. The ambition to carry the revolution eastward had to be postponed after the failure of two successive invasions of Egypt, led by al-Qa'im, in

914–915 and

919–921. In addition, the Fatimid regime was as yet unstable. The local population were mostly adherents of

Maliki

The ( ar, مَالِكِي) school is one of the four major schools of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was founded by Malik ibn Anas in the 8th century. The Maliki school of jurisprudence relies on the Quran and hadiths as primary ...

Sunnism and various

Kharijite sects such as

Ibadism

The Ibadi movement or Ibadism ( ar, الإباضية, al-Ibāḍiyyah) is a school of Islam. The followers of Ibadism are known as the Ibadis.

Ibadism emerged around 60 years after the Islamic prophet Muhammad's death in 632 AD as a moderate sc ...

, so that the real power base of Fatimids in Ifriqiya was quite narrow, resting on the Kutama soldiery, later extended by the

Sanhaja

The Sanhaja ( ber, Aẓnag, pl. Iẓnagen, and also Aẓnaj, pl. Iẓnajen; ar, صنهاجة, ''Ṣanhaja'' or زناگة ''Znaga'') were once one of the largest Berber tribal confederations, along with the Zanata and Masmuda confederations. Ma ...

Berber tribes as well. The historian

Heinz Halm

Heinz Halm (born 21 February 1942 in Andernach, Rhine Province) is a German scholar of Islamic Studies, with a particular expertise on early Shia history, the Ismailites and other Shia sects.

Life

Born and raised in Andernach, Halm studied Islami ...

describes the early Fatimid state as being, in essence, "a hegemony of the Kutama and Sanhaja Berbers over the eastern and central Maghrib". In 912 al-Mahdi began looking for the site of a new capital along the Mediterranean shore.

Construction of the new fortified palace city,

al-Mahdiyya, began in 916. The new city was officially inaugurated on 20 February 921, though construction continued after this.

The new capital was removed from the Sunni stronghold of Kairouan, allowing for the establishment of a secure base for the Caliph and his Kutama forces without raising further tensions with the local population.

The Fatimids also inherited the Aghlabid province of

Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, which the Aghlabids had

gradually conquered from the

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

starting in 827. The conquest was generally completed when the last

Christian stronghold,

Taormina

Taormina ( , , also , ; scn, Taurmina) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Messina, on the east coast of the island of Sicily, Italy. Taormina has been a tourist destination since the 19th century. Its beaches on ...

, was conquered by Ibrahim II in 902.

However, some Christian or Byzantine resistance continued in some spots in the northeast of Sicily until 967, and the Byzantines still held territories in southern Italy, where the Aghlabids had also campaigned.

This ongoing confrontation with the traditional foe of the Islamic world provided the Fatimids with a prime opportunity for propaganda, in a setting where geography gave them the advantage. Sicily itself proved troublesome, and only after a rebellion under

Ibn Qurhub was subdued, was Fatimid authority on the island consolidated.

Consolidation and western rivalry

For a large part of the tenth century the Fatimids also engaged in a rivalry with the

Umayyads of Cordoba – who ruled

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

and were hostile to the Fatimids' pretensions – in an effort to establish domination over the western Maghreb. In 911,

Tahert

Tiaret ( ar, تاهرت / تيارت; Berber: Tahert or Tihert, i.e. "Lioness") is a major city in northwestern Algeria that gives its name to the wider farming region of Tiaret Province. Both the town and region lie south-west of the capital of ...

, which had been briefly captured by Abu Abdallah al-Shi'i in 909, had to be retaken by the Fatimid general

Masala ibn Habus of the

Miknasa

The Miknasa (Berber: ''Imeknasen'') was a Zenata Berber tribe in Morocco and Algeria.

The Miknasa Berbers historically populated the Aurès and are part of the Dharisa tribe belonging to Botr who descended from Madghis, coming from the Aures mount ...

tribe. The first Fatimid expeditions to what is now northern Morocco occurred in 917 and 921 and were primarily aimed at the

Principality of Nakur, which they subjugated on both occasions. Fez and Sijilmasa were also captured in 921. These two expeditions were led by Masala ibn Habus, who had been made governor of

Tahert

Tiaret ( ar, تاهرت / تيارت; Berber: Tahert or Tihert, i.e. "Lioness") is a major city in northwestern Algeria that gives its name to the wider farming region of Tiaret Province. Both the town and region lie south-west of the capital of ...

. Thereafter, the weakened

Idrisids

The Idrisid dynasty or Idrisids ( ar, الأدارسة ') were an Arab Muslim dynasty from 788 to 974, ruling most of present-day Morocco and parts of present-day western Algeria. Named after the founder, Idris I, the Idrisids were an Alid and ...

and various local

Zenata

The Zenata ( Berber language: Iznaten) are a group of Amazigh (Berber) tribes, historically one of the largest Berber confederations along with the Sanhaja and Masmuda. Their lifestyle was either nomadic or semi-nomadic.

Etymology

''Iznaten ( ...

and

Sanhaja

The Sanhaja ( ber, Aẓnag, pl. Iẓnagen, and also Aẓnaj, pl. Iẓnajen; ar, صنهاجة, ''Ṣanhaja'' or زناگة ''Znaga'') were once one of the largest Berber tribal confederations, along with the Zanata and Masmuda confederations. Ma ...

leaders acted as proxies whose formal allegiances oscillated between the Umayyads or the Fatimids depending on the circumstances.

As a result of the political instability in the western Maghreb, effective Fatimid control did not extend much beyond the former territory of the Aghlabids. Masala's successor,

Musa ibn Abi'l-Afiya, captured Fez from the Idrisids again, but in 932 defected to the Umayyads, taking the western Maghreb with him. The Umayyads gained the upper hand again in northern Morocco during the 950s, until the Fatimid general

Jawhar

Jawhar is a city and a municipal council in Palghar district of Maharashtra state in Konkan division of India. Jawhar was a capital city of the erstwhile Koli princely state of Jawhar.

Situated in the ranges of the Western Ghats, Jawhar is ...

, on behalf of Caliph

Al-Mu'izz li-Din Allah, led another major

expedition to Morocco in 958 and spent two years subjugating most of northern Morocco. He was accompanied by

Ziri ibn Manad Ziri ibn Manad or Ziri son of Mennad (died in 971) was the founder of the Zirid dynasty in the Maghreb.

Ziri ibn Mennad was a chief of the Takalata branch of the Sanhajah confederation, to which the Kutama Berbers belonged located in the Central M ...

, the leader of the

Zirids

The Zirid dynasty ( ar, الزيريون, translit=az-zīriyyūn), Banu Ziri ( ar, بنو زيري, translit=banū zīrī), or the Zirid state ( ar, الدولة الزيرية, translit=ad-dawla az-zīriyya) was a Sanhaja Berber dynasty from ...

. Jawhar took Sijilmasa in September or October 958 and then, with the help of Ziri, his forces took Fez in November 959. He was unable, however, to dislodge the Umayyad garrisons in

Sala,

Sebta (present-day Ceuta) and

Tangier

Tangier ( ; ; ar, طنجة, Ṭanja) is a city in northwestern Morocco. It is on the Moroccan coast at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar, where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Spartel. The town is the capi ...

, and this marked the only time that the Fatimid army was present at the

Strait of Gibraltar. Jawhar and Ziri returned to al-Mansuriyya in 960. The subjugated parts of Morocco, including Fez and Sijilmasa, were left under the control of local vassals while most of the central Maghreb (Algeria), including Tahert, was given to Ziri ibn Manad to govern on the caliph's behalf.

All this warfare in the Maghreb and Sicily necessitated the maintenance of a strong army, and a

capable fleet as well. Nevertheless, by the time of al-Mahdi's death in 934, the Fatimid Caliphate "had become a great power in the Mediterranean". The reign of the second Fatimid imam-caliph, al-Qa'im, was dominated by the Kharijite rebellion of

Abu Yazid

Abu Yazid Makhlad ibn Kaydad (; – 19 August 947), known as the Man on the Donkey (), was an Ibadi Berber of the Banu Ifran tribe who led a rebellion against the Fatimid Caliphate in Ifriqiya (modern Tunisia and eastern Algeria) starting ...

. Starting in 943/4 among the

Zenata

The Zenata ( Berber language: Iznaten) are a group of Amazigh (Berber) tribes, historically one of the largest Berber confederations along with the Sanhaja and Masmuda. Their lifestyle was either nomadic or semi-nomadic.

Etymology

''Iznaten ( ...

Berbers, the uprising spread through Ifriqiya, taking Kairouan and blockading al-Qa'im at al-Mahdiyya, which was besieged in January–September 945. Al-Qa'im died during the siege, but this was kept secret by his son and successor, Isma'il, until he had defeated Abu Yazid; he then announced his father's death and proclaimed himself imam and caliph as

al-Mansur

Abū Jaʿfar ʿAbd Allāh ibn Muḥammad al-Manṣūr (; ar, أبو جعفر عبد الله بن محمد المنصور; 95 AH – 158 AH/714 CE – 6 October 775 CE) usually known simply as by his laqab Al-Manṣūr (المنصور) w ...

. While al-Mansur was campaigning to suppress the last remnants of the revolt, a new palace city was being constructed for him south of Kairouan. Construction began around 946 and it was only fully completed under al-Mansur's son and successor, al-Mu'izz.

It was named

al-Mansuriyya (also known as Sabra al-Mansuriyya) and became the new seat of the caliphate.

Apogee

Conquest of Egypt and transfer of the Caliphate to Cairo

In 969 Jawhar launched a carefully-prepared and successful

invasion of Egypt, which had been under the control of the

Ikhshidids

The Ikhshidid dynasty (, ) was a Turkic mamluk dynasty who ruled Egypt and the Levant from 935 to 969. Muhammad ibn Tughj al-Ikhshid, a Turkic mamluk soldier, was appointed governor by the Abbasid Caliph al-Radi. The dynasty carried the Arabic t ...

, another regional dynasty whose formal allegiance was to the Abbasids. Al-Mu'izz had given Jawhar specific instructions to carry out after the conquest, and one of his first actions was to found a new capital named ''al-Qāhira'' (

Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the Capital city, capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, List of ...

) in 969. The name ''al-Qāhirah'' ( ar , القاهرة), meaning "the Vanquisher" or "the Conqueror", referenced the planet

Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin at ...

, "The Subduer",

rising in the sky at the time when the construction of the city started. The city was located several miles northeast of

Fusṭāt, the older regional capital founded by the

Arab conquerors in the seventh century.

Control of Egypt was secured with relative ease and soon afterward, in 970, Jawhar sent a force to invade Syria and remove the remaining Ikhshidids who had fled there from Egypt. This Fatimid force was led by a Kutama general named

Ja'far ibn Falāḥ. This invasion was successful at first and many cities, including Damascus, were occupied that same year. Ja'far's next step was to attack the Byzantines, who had captured

Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

and subjugated

Aleppo in 969 (around the same time as Jawhar was arriving in Egypt), but he was forced to call off the advance in order to face a new threat from the east. The Qarmatis of Bahrayn, responding to the appeal of the recently defeated leaders of Damascus, had organized a large coalition of Arab tribesmen to attack him. Ja'far chose to confront them in the desert in August 971, but his army was surrounded and defeated and Ja'far himself was killed. A month later the Qarmati imam Hasan al-A'ṣam led the army, with new reinforcements from

Transjordan, into Egypt, seemingly without opposition. The Qarmatis spent time occupying the Nile Delta region, which gave Jawhar time to organize a defense of Fustat and Cairo. The Qarmati advance was halted just north of the city and eventually routed. A

Kalbid

The Kalbids () were a Muslim Arab dynasty in the Emirate of Sicily, which ruled from 948 to 1053. They were formally appointed by the Fatimids, but gained, progressively, ''de facto'' autonomous rule.

History

In 827, in the midst of internal By ...

relief force arriving by sea secured the expulsion of the Qarmatis from Egypt.

Ramla

Ramla or Ramle ( he, רַמְלָה, ''Ramlā''; ar, الرملة, ''ar-Ramleh'') is a city in the Central District of Israel. Today, Ramle is one of Israel's mixed cities, with both a significant Jewish and Arab populations.

The city was f ...

, the capital of

Palestine, was retaken by the Fatimids in May 972, but otherwise the progress in Syria had been lost.

Once Egypt was sufficiently pacified and the new capital was ready, Jawhar sent for al-Mu'izz in Ifriqiya. The caliph, his court, and his treasury, departed from al-Mansuriyya in fall 972, traveling by land but shadowed by the Fatimid navy sailing along the coast. After making triumphant stops in major cities along the way, the caliph arrived in Cairo on 10 June 973. Like other royal capitals before it, Cairo was constructed as an administrative and palatine city, housing the

palaces of the caliph and the official state mosque,

Al-Azhar Mosque

Al-Azhar Mosque ( ar, الجامع الأزهر, al-Jāmiʿ al-ʾAzhar, lit=The Resplendent Congregational Mosque, arz, جامع الأزهر, Gāmiʿ el-ʾazhar), known in Egypt simply as al-Azhar, is a mosque in Cairo, Egypt in the histori ...

. In 988 the mosque also became an academic institution that was central in the dissemination of Isma'ili teachings.

Until the last years of the Fatimid Caliphate, the economic centre of Egypt remained Fustat, where most of the general population lived and traded.

Under the Fatimids, Egypt became the centre of an empire that included at its peak parts of North Africa, Sicily, the

Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

(including Transjordan), the

Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

coast of Africa,

Tihamah

Tihamah or Tihama ( ar, تِهَامَةُ ') refers to the Red Sea coastal plain of the Arabian Peninsula from the Gulf of Aqaba to the Bab el Mandeb.

Etymology

Tihāmat is the Proto-Semitic language's term for ' sea'. Tiamat (or Tehom, in m ...

,

Hejaz,

Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

, with its most remote territorial reach being

Multan (in modern-day Pakistan).

Egypt flourished, and the Fatimids developed an extensive trade network both in the Mediterranean and in the Indian Ocean. Their trade and diplomatic ties, extending all the way to China under the

Song Dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the rest ...

(), eventually determined the economic course of Egypt during the

High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended around AD 150 ...

. The Fatimid focus on agriculture further increased their riches and allowed the dynasty and the Egyptians to flourish. The use of cash crops and the propagation of the

flax trade allowed Fatimids to import other items from various parts of the world. The Fatimids built upon some of the bureaucratic foundations laid by the Ikhshidids and the old Abbasid imperial order. The office of the ''wazīr'' (

vizier

A vizier (; ar, وزير, wazīr; fa, وزیر, vazīr), or wazir, is a high-ranking political advisor or minister in the near east. The Abbasid caliphs gave the title ''wazir'' to a minister formerly called '' katib'' (secretary), who was ...

), which existed under the Ikhshidids, was soon revived under the Fatimids. The first to be appointed to this position was the

Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

convert

Ya'qub ibn Killis Abu'l-Faraj Ya'qub ibn Yusuf ibn Killis ( ar, يعقوب ابن كلس, Abu’l-Faraj Yaʿqūb ibn Yūsuf ibn Killis, he, יעקוב אבן כיליס), (930 in Baghdad – 991), commonly known simply by his patronymic surname as Ibn Killis, was a ...

, who was elevated to this office in 979 by al-Mu'izz's successor

al-Aziz

Abu Mansur Nizar ( ar, أبو منصور نزار , Abū Manṣūr Nizār; 10 May 955 – 14 October 996), known by his regnal name as al-Aziz Billah ( ar, العزيز بالله, al-ʿAzīz bi-llāh, the Mighty One through God), was the fifth ...

. The office of the vizier became progressively more important over the years, as the vizier became the intermediary between the caliph and the large bureaucratic state that he ruled.

Campaigns in Syria

In 975 the Byzantine emperor

John Tzimisces retook most of Palestine and Syria, leaving only

Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis may refer to:

Cities and other geographic units Greece

*Tripoli, Greece, the capital of Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in ...

in Fatimid control. He aimed to eventually capture

Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

, but he died in 976 on his way back to

Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya ( Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

, thus staving off the Byzantine threat to the Fatimids. Meanwhile, the Turkish ''

ghulām'' (plural: ''ghilmān'', meaning soldiers recruited as slaves)

Aftakin

Alptakin (also known as Aftakin) was a Turkish military officer of the Buyids, who participated, and eventually came to lead, an unsuccessful rebellion against them in Iraq from 973 to 975. Fleeing west with 300 followers, he exploited the power v ...

, a

Buyid

The Buyid dynasty ( fa, آل بویه, Āl-e Būya), also spelled Buwayhid ( ar, البويهية, Al-Buwayhiyyah), was a Shia Islam, Shia Iranian peoples, Iranian dynasty of Daylamites, Daylamite origin, which mainly ruled over Iraq and central ...

refugee who had fled an unsuccessful rebellion in Baghdad with his own contingent of Turkish soldiers, became the protector of Damascus. He allied with the Qarmatis and with Arab

Bedouin tribes in Syria and invaded Palestine in the spring of 977. Jawhar, once again called into action, repelled their invasion and besieged Damascus. However he suffered a rout during the winter and was forced to hold out in

Ascalon against Aftakin. When his Kutama soldiers mutinied in April 978, Caliph al-Aziz himself led an army to relieve him. Instead of returning to Damascus, Aftakin and his Turkish ''ghilman'' joined the Fatimid army and became a useful instrument in the Syrian effort.

After Ibn Killis became vizier in 979, the Fatimids changed tactics. Ibn Killis was able to subjugate most of Palestine and southern Syria (the former Ikhshidid territories) by paying off the Qarmatis with an annual tribute and making alliances with local tribes and dynasties, such as the

Jarrahids

The Jarrahids () (also known as Banu al-Jarrah) were an Arab dynasty that intermittently ruled Palestine and controlled Transjordan and northern Arabia in the late 10th and early 11th centuries. They were described by historian Marius Canard ...

and the

Banu Kilab

The Banu Kilab ( ar, بنو كِلاب, Banū Kilāb) was an Arab tribe in the western Najd (central Arabia) where they controlled the horse-breeding pastures of Dariyya from the mid-6th century until at least the mid-9th century. The tribe was div ...

. Following another failed attempt by a Kutama general, Salman, to take Damascus, the Turkish ''ghulām'' Bultakīn finally succeeded in occupying the city for the Fatimids in 983, demonstrating the value of this new force. Another ''ghulām'', Bajkūr, who appointed governor of Damascus at this time. That same year he tried and failed to take Aleppo, but he was soon able to conquer

Raqqa

Raqqa ( ar, ٱلرَّقَّة, ar-Raqqah, also and ) (Kurdish: Reqa/ ڕەقە) is a city in Syria on the northeast bank of the Euphrates River, about east of Aleppo. It is located east of the Tabqa Dam, Syria's largest dam. The Hellenistic, ...

and

Rahba

Al-Rahba (/ALA-LC: ''al-Raḥba'', sometimes spelled ''Raḥabah''), also known as Qal'at al-Rahba, which translates as the "Citadel of al-Rahba", is a medieval Arab fortress on the west bank of the Euphrates River, adjacent to the city of Ma ...

in the

Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers''). Originating in Turkey, the Eup ...

valley (present-day northeast

Syria). Cairo eventually judged him to be a little too popular as governor of Damascus and he was forced to move to Raqqa while Munir, a eunuch in the caliph's household (like Jawhar before him), took direct control in Damascus on behalf of the caliph. Further north, Aleppo remained out of reach and under

Hamdanid

The Hamdanid dynasty ( ar, الحمدانيون, al-Ḥamdāniyyūn) was a Twelver Shia Arab dynasty of Northern Mesopotamia and Syria (890–1004). They descended from the ancient Banu Taghlib Christian tribe of Mesopotamia and Eastern ...

control.

The incorporation of the Turkish troops into the Fatimid army had long-term consequences. On the one hand, they were a necessary addition to the military in order for the Fatimids to compete militarily with other powers in the region. The Fatimids began to recruit ''ghilmān'' much as the Abbasids had done before them. They were soon joined by recruited

Daylamis (footmen from the Buyid homeland in

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

).

Black Africans from the

Sudan (upper Nile valley) were also recruited afterward. In the short term the Kutama warriors remained the most important troops of the Caliph, but resentment and rivalry eventually grew between the different ethnic components of the army.

Bajkūr, based in Raqqa, made another unsuccessful attempt against Aleppo in 991 which resulted in his capture and execution. That same year, Ibn Killis died and Munir was accused of conducting treasonous correspondence with Baghdad. These difficulties triggered a strong response in Cairo. A major military campaign was prepared to impose Fatimid control over all of Syria. Along the way, Munir was arrested in Damascus and sent back to Cairo. Circumstances were favourable to the Fatimids as the Byzantine emperor

Basil II

Basil II Porphyrogenitus ( gr, Βασίλειος Πορφυρογέννητος ;) and, most often, the Purple-born ( gr, ὁ πορφυρογέννητος, translit=ho porphyrogennetos).. 958 – 15 December 1025), nicknamed the Bulgar S ...

was campaigning far away in the

Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

and the Hamdanid ruler

Sa'd al-Dawla

Abu 'l-Ma'ali Sharif, more commonly known by his honorific title, Sa'd al-Dawla ( ar, سعد الدولة), was the second ruler of the Hamdanid Emirate of Aleppo, encompassing most of northern Syria. The son of the emirate's founder, Sayf al-D ...

died in late 991. Manjūtakīn, the Turkish Fatimid commander, advanced methodically north along the Orontes valley. He took Homs and Hama in 992 and defeated a combined force from Hamdanid Aleppo and Byzantine-held Antioch. In 993 he took Shayzar and in 994 he began the siege of Aleppo. In May 995, however, Basil II unexpectedly arrived in the region after a

forced march

A loaded march is a relatively fast march over distance carrying a load and is a common military exercise.

A loaded march is known as a forced foot march in the US Army. Less formally, it is a ruck march in the Canadian Armed Forces and the US A ...

with his army through Anatolia, forcing Manjūtakīn to lift the siege and return to Damascus. Before another Fatimid expedition could be sent, Basil II negotiated a one-year truce with the caliph, which the Fatimids used to recruit and build new ships for their fleet. In 996 many of the ships were destroyed by a fire at al-Maqs, the port on the Nile near Fustat, further delaying the expedition. Finally, in August 996 al-Aziz died and the objective of Aleppo became secondary to other concerns.

The Zirids in the Maghreb

Before leaving for Egypt, al-Mu'izz had installed

Buluggin ibn Ziri

Buluggin ibn Ziri, often transliterated Bologhine, in full ʾAbū al Futūḥ Sayf ad Dawlah Bulukīn ibn Zīrī ibn Manād aṣ Ṣanhājī ( ar, أبو الفتوح سيف الدولة بلكين بن زيري بن مناد الصنهاجي; die ...

, the son of Ziri bn Manad (who died in 971), as his viceroy in the Maghreb. This established a dynasty of viceroys, with the title of "amir", who ruled the region on behalf of the Fatimids.

Their authority remained disputed in the western Maghreb, where the rivalry with the Umayyads and with local Zenata leaders continued. After Jawhar's successful western expedition, the Umayyads returned to northern Morocco in 973 to reassert their authority. Buluggin launched one last expedition in 979–980 that reestablished his authority in the region temporarily, until a final decisive Umayyad intervention in 984–985 put an end to further efforts.

In 978 the caliph also gave

Tripolitania

Tripolitania ( ar, طرابلس '; ber, Ṭrables, script=Latn; from Vulgar Latin: , from la, Regio Tripolitana, from grc-gre, Τριπολιτάνια), historically known as the Tripoli region, is a historic region and former province o ...

to Buluggin to govern, though Zirid authority there was later replaced by a local dynasty in 1001.

In 988 Buluggin's son and successor al-Mansur moved the Zirid dynasty's base from

Ashir (central Algeria) to the former Fatimid capital al-Mansuriyya, cementing the status of the Zirids as more or less ''de facto'' independent rulers of Ifriqiya, while still officially maintaining their allegiance to the Fatimid caliphs. Caliph al-Aziz accepted this situation for pragmatic reasons to maintain his own formal status as universal ruler. Both dynasties exchanged gifts and the succession of new Zirid rulers to the throne was officially sanctioned by the caliph in Cairo.

The reign of al-Hakim

After al-Aziz's unexpected death, his young son al-Mansur, 11 years old, was installed on the throne as

al-Hakim. Hasan ibn Ammar, the leader of the Kalbid clan in Egypt, a military veteran, and one of the last remaining members of al-Mu'izz's old guard, initially became regent, but he was soon forced to flee by Barjawan, the eunuch and tutor of the young al-Hakim, who took power in his stead. Barjawan stabilized the internal affairs of the empire but refrained from pursuing al-Aziz's policy of expansion towards Aleppo. In the year 1000, Barjawan was assassinated by al-Hakim, who now took direct and autocratic control of the state. His reign, which lasted until his mysterious disappearance in 1021, is the most controversial in Fatimid history. Traditional narratives have described him as either eccentric or outright insane, but more recent studies have tried to provide more measured explanations based on the political and social circumstances of the time.

Among other things, al-Hakim was known for executing his officials when unsatisfied with them, seemingly without warning, rather than dismissing them from their posts as had been traditional practice. Many of the executions were members of the financial administration, which may mean that this was al-Hakim's way of trying to impose discipline in an institution rife with corruption. He also opened the ''Dar al-'Ilm'' ("House of Knowledge"), a library for the study of the sciences, which was in line with al-Aziz's previous policy of cultivating this knowledge. For the general population, he was noted for being more accessible and willing to receive petitions in person, as well as for riding out in person among the people in the streets of Fustat. On the other hand, he was also known for his capricious decrees aimed at curbing what he saw as public improprieties. He also unsettled the plurality of Egyptian society by imposing new restrictions on Christians and Jews, particularly on the way they dressed or behaved in public. He ordered or sanctioned the destruction of a number of churches and monasteries (mostly

Coptic or

Melkite), which was unprecedented, and in 1009, for reasons that remain unclear, he ordered the demolition of the

Church of the Holy Sephulchre in Jerusalem.

Al-Hakim greatly expanded the recruitment of Black Africans into the army, who subsequently became another powerful faction to balance against the Kutama, Turks, and Daylamis. In 1005, during his early reign, a dangerous uprising led by

Abu Rakwa was successfully put down but had come within striking distance of Cairo. In 1012 the leaders of the Arab

Tayyi tribe occupied Ramla and proclaimed the

sharif

Sharīf ( ar, شريف, 'noble', 'highborn'), also spelled shareef or sherif, feminine sharīfa (), plural ashrāf (), shurafāʾ (), or (in the Maghreb) shurfāʾ, is a title used to designate a person descended, or claiming to be descended, f ...

of

Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow ...

,

al-Ḥasan ibn Ja'far, as the Sunni anti-caliph, but the latter's death in 1013 led to their surrender. Despite his policies against Christians and his demolition of the church in Jerusalem, al-Hakim maintained a ten-year truce with the Byzantines that began in 1001. For most of his reign, Aleppo remained a buffer state that paid tribute to Constantinople. This lasted until 1017, when the Fatimid

Armenian

Armenian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Armenia, a country in the South Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Armenians, the national people of Armenia, or people of Armenian descent

** Armenian Diaspora, Armenian communities across the ...

general

Fatāk finally occupied Aleppo at the invitation of a

local commander who had expelled the Hamdanid ''ghulām'' ruler

Mansur ibn Lu'lu'

Manṣūr ibn Luʾluʾ ( ar, منصور بن لؤلؤ), also known by his ''laqab'' (honorific epithet) of Murtaḍā ad-Dawla (, 'Approved of the State'), was the ruler of the Emirate of Aleppo between 1008 and 1016. He succeeded his father Lu' ...

. After a year or two, however, Fatāk made himself effectively independent in Aleppo.

Al-Hakim also alarmed his Isma'ili followers in several ways. In 1013 he announced the designation of two great-great-grandsons of al-Mahdi as two separate heirs: one, Abd al-Raḥīm ibn Ilyās, would inherit the title of caliphate as the role of political ruler, and the other, Abbās ibn Shu'ayb, would inherit the imamate or religious leadership. This was a serious departure from a central purpose of the Fatimid Imam-Caliphs, which was to combine these two functions in one person. In 1015 he also suddenly halted the Isma'ili doctrinal lectures of the ''majālis al-ḥikma'' ("sessions of wisdom") which had taken place regularly inside the palace. In 1021, while wandering the desert outside Cairo on one of his nightly excursions, he disappeared. He was purportedly murdered, but his body was never found.

Decline

Losses, successes, and civil war

After al-Hakim's death his two designated heirs were killed, putting an end to his succession scheme, and his sister

Sitt al-Mulk

Sitt al-Mulk ( ar, ست الملك, , Lady of the Kingdom ; 970–1023), was a Fatimid princess. After the disappearance of her half-brother, the caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, in 1021, she was instrumental in securing the succession of her ne ...

arranged to have his 15-year-old son Ali installed on the throne as

al-Zahir

Abū Nasr Muhammad ibn al-Nāsir ( ar, أبو نصر محمد بن الناصر; 1175 – 11 July 1226), better known with his regnal name al-Zāhir bi-Amr Allāh ( ar, الظاهر بأمر الله, , He Who Appears Openly by the Order of God) ...

. She served as his regent until her death in 1023, at which point an alliance of courtiers and officials ruled, with

al-Jarjarā'ī, a former finance official, at their head. Fatimid control in Syria was threatened during the 1020s. In Aleppo, Fatāk, who had declared his independence, was killed and replaced in 1022, but this opened the way for a coalition of Bedouin chiefs from the Banu Kilab, Jarrahids, and

Banu Kalb

The Banu Kalb ( ar, بنو كلب) was an Arab tribe which mainly dwelt in the desert between northwestern Arabia and central Syria. The Kalb was involved in the tribal politics of the eastern frontiers of the Byzantine Empire, possibly as early ...

led by

Salih ibn Mirdas

Abu Ali Salih ibn Mirdas ( ar, ابو علي صالح بن مرداس, Abū ʿAlī Ṣāliḥ ibn Mirdās), also known by his ''laqab'' (honorific epithet) Asad al-Dawla ('Lion of the State'), was the founder of the Mirdasid dynasty and emir of ...

to take the city in 1024 or 1025 and to begin imposing their control on the rest of Syria. Al-Jarjarā'ī sent

Anushtakin al-Dizbari

Sharaf al-Maʿālī Abu Manṣūr Anūshtakīn al-Dizbarī (died January 1042) was a Fatimid statesman and general who became the most powerful Fatimid governor of Syria. Under his Damascus-based administration, all of Syria was united under a si ...

, a Turkish commander, with a force that defeated them in 1029 at the Battle of Uqḥuwāna near Lake Tiberias. In 1030 the new Byzantine emperor

Romanos III

Romanos III Argyros ( el, Ρωμανός Αργυρός; Latinized Romanus III Argyrus; 968 – 11 April 1034), or Argyropoulos was Byzantine Emperor from 1028 until his death. He was a Byzantine noble and senior official in Constantinople whe ...

broke a truce to

invade northern Syria and forced Aleppo to recognize his suzerainty. His death in 1034 changed the situation again and in 1036 peace was restored. In 1038 Aleppo was directly annexed by the Fatimids state for the first time.

Al-Zahir died in 1036 and was succeeded by his son,

al-Mustansir, who had the longest reign in Fatimid history, serving as caliph from 1036 to 1094. However, he remained largely uninvolved in politics and left the government in the hands of others. He was seven years old at his accession and thus al-Jarjarā'ī continued to serve as vizier and his guardian. When al-Jarjarā'ī died in 1045 a series of court figures ran the government until

al-Yāzūrī, a

jurist of Palestinian origin, took and kept the office of vizier from 1050 to 1058.

In the 1040s (possibly in 1041 or 1044), the Zirids declared their independence from the Fatimids and recognized the Sunni Abbasid caliphs of Baghdad, which led the Fatimids to launch the devastating

Banū Hilal invasions of North Africa.

Fatimid suzerainty over Sicily also faded as the Muslim polity there fragmented and external attacks increased. By 1060, when the

Italo-Norman

The Italo-Normans ( it, Italo-Normanni), or Siculo-Normans (''Siculo-Normanni'') when referring to Sicily and Southern Italy, are the Italian-born descendants of the first Norman conquerors to travel to southern Italy in the first half of th ...

Roger I Roger I may refer to:

:''In chronological order''

* Roger I of Carcassonne (died 1012), Count of Carcassonne

* Roger I of Tosny (), Norman noble

* Roger I "de Berkeley" (died 1093), Norman noble, possibly the son of Roger I of Tosny - see Baron ...

began his conquest of the island (completed in 1091), the Kalbid dynasty, along with any Fatimid authority, were already gone.

There was more success in the east, however. In 1047 the Fatimid

Ali Muhammad al-Ṣulayḥi in Yemen built a fortress and recruited tribes with which he was able to capture

San'a

Sanaa ( ar, صَنْعَاء, ' , Yemeni Arabic: ; Old South Arabian: 𐩮𐩬𐩲𐩥 ''Ṣnʿw''), also spelled Sana'a or Sana, is the capital and largest city in Yemen and the centre of Sanaa Governorate. The city is not part of the Govern ...

in 1048. In 1060 he began a campaign to conquer all of Yemen, capturing

Aden and

Zabid

Zabid ( ar, زَبِيد) (also spelled Zabīd, Zabeed and Zebid) is a town with an urban population of around 52,590 people on Yemen's western coastal plain. It is one of the oldest towns in Yemen, and has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since ...

. In 1062 he marched on Mecca, where

Shukr ibn Abi al-Futuh's death in 1061 provided an excuse. Along the way he forced the

Zaydi

Zaydism (''h'') is a unique branch of Shia Islam that emerged in the eighth century following Zayd ibn Ali‘s unsuccessful rebellion against the Umayyad Caliphate. In contrast to other Shia Muslims of Twelver Shi'ism and Isma'ilism, Zaydis, ...

Imam in

Sa'da into submission. Upon arriving in Mecca, he installed

Abu Hashim Muhammad ibn Ja'far

Abū Hāshim Muḥammad ibn Ja‘far al-Ḥasanī al-‘Alawī ( ar, أبو هاشم محمد بن جعفر الحسني العلوي; d. 1094/1095) was the first Emir of Mecca from the sharifian dynasty of the Hawashim. He was appointed Emir by ...

as the new sharif and custodian of the holy sites under the suzerainty of the Fatimids. He returned to San'a where he established his family as rulers on behalf of the Fatimid caliphs. His brother founded the city of

Ta'izz

Taiz ( ar, تَعِزّ, Taʿizz) is a city in southwestern Yemen. It is located in the Yemeni Highlands, near the port city of Mocha on the Red Sea, at an elevation of about above sea level. It is the capital of Taiz Governorate. With a populat ...

, while the city of Aden became an important hub of trade between Egypt and

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, which brought Egypt further wealth.

Events degenerated in Egypt and Syria, however. Starting in 1060, various local leaders began to break away or challenge Fatimid dominion in Syria. While the ethnic-based army was generally successful on the battlefield, it had begun to have negative effects on Fatimid internal politics. Traditionally the Kutama element of the army had the strongest sway over political affairs, but as the Turkish element grew more powerful, it began to challenge this. In 1062, the tentative balance between the different ethnic groups within the Fatimid army collapsed and they quarreled constantly or fought each other in the streets. At the same time, Egypt suffered a 7-year period of drought and famine. Viziers came and went in flurry, the bureaucracy broke down, and the caliph was unable or unwilling to assume responsibilities in their absence. Declining resources accelerated the problems among the different ethnic factions, and outright civil war began, primarily between the Turks under