Edmontosaurus pelvis left.jpg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Edmontosaurus'' ( ) (meaning "lizard from Edmonton") is a genus of hadrosaurid (duck-billed) dinosaur. It contains two known species: ''Edmontosaurus regalis'' and ''Edmontosaurus annectens''. Fossils of ''E. regalis'' have been found in rocks of western North America that date from the late Campanian Stage (stratigraphy), stage of the Cretaceous Period (geology), Period 73 million years ago, while those of ''E. annectens'' were found in the same geographic region but in rocks dated to the end of the Maastrichtian stage of the Cretaceous, 66 million years ago. ''Edmontosaurus'' was one of the last non-bird, avian dinosaurs, and lived alongside dinosaurs like ''Triceratops'', ''Tyrannosaurus'', ''Ankylosaurus'', and ''Pachycephalosaurus'' shortly before the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event.

''Edmontosaurus'' included some of the largest hadrosaurid species, with ''E. annectens'' measuring up to in length and weighing around in average asymptotic body mass, although some individuals would have been larger. Several well-preserved specimens are known that include not only bones, but in some cases extensive skin impressions and possible gut contents. It is classified as a genus of Saurolophinae, saurolophine (or Hadrosaurinae, hadrosaurine) hadrosaurid, a member of the group of hadrosaurids which lacked large, hollow crests, instead having smaller solid crests or fleshy combs.

The first fossils named ''Edmontosaurus'' were discovered in southern Alberta (named after Edmonton, the capital city), in the Horseshoe Canyon Formation (formerly called the lower Edmonton Formation). The type species, ''E. regalis'', was named by Lawrence Lambe in 1917, although several other species that are now classified in ''Edmontosaurus'' were named earlier. The best known of these is ''E. annectens'', named by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1892; originally as a species of ''Claosaurus'', known for many years as a species of ''Trachodon'', and later as ''Anatosaurus annectens''. ''Anatosaurus,'' ''Anatotitan'' and probably ''Ugrunaaluk'' are now generally regarded as synonyms of ''Edmontosaurus''.

''Edmontosaurus'' was widely distributed across western North America, ranging from Colorado to the north slopes of Alaska. The distribution of ''Edmontosaurus'' fossils suggests that it preferred coasts and coastal plains. It was a herbivore that could move on both two legs and four. Because it is known from several bone beds, ''Edmontosaurus'' is thought to have lived in groups, and may have been migratory as well. The wealth of fossils has allowed researchers to study its paleobiology in detail, including its brain, how it may have fed, and its injuries and pathology, pathologies, such as evidence for tyrannosaur attacks on a few edmontosaur specimens.

''Edmontosaurus'' has had a long and complicated history in paleontology, having spent decades with various species classified in other genera. Its Taxonomy (biology), taxonomic history intertwines at various points with the genera ''Agathaumas'', ''Anatosaurus'', ''Anatotitan'', ''Claosaurus'', ''Hadrosaurus'', ''Thespesius'', and ''Trachodon'', and references predating the 1980s typically use ''Anatosaurus'', ''Claosaurus'', ''Thespesius'', or ''Trachodon'' for edmontosaur fossils (excluding those assigned to ''E. regalis''), depending on author and date. Although ''Edmontosaurus'' was only named in 1917, its oldest well-supported species (''E. annectens'') was named in 1892 as a species of ''Claosaurus''.

The first well-supported species of ''Edmontosaurus'' was named in 1892 as ''Claosaurus annectens'' by Othniel Charles Marsh. This species is holotype, based on National Museum of Natural History, USNM 2414, a partial skull-roof and skeleton, with a second skull and skeleton, Peabody Museum of Natural History, YPM 2182, designated the paratype. Both were collected in 1891 by John Bell Hatcher from the late Maastrichtian-age Upper Cretaceous Lance Formation of Niobrara County, Wyoming, Niobrara County (then part of Converse County, Wyoming, Converse County), Wyoming. This species has some historical footnotes attached: it is among the first dinosaurs to receive a skeletal restoration, and is the first hadrosaurid so restored; and YPM 2182 and UNSM 2414 are, respectively, the first and second essentially complete mounted dinosaur skeletons in the United States. YPM 2182 was put on display in 1901, and USNM 2414 in 1904.

''Edmontosaurus'' has had a long and complicated history in paleontology, having spent decades with various species classified in other genera. Its Taxonomy (biology), taxonomic history intertwines at various points with the genera ''Agathaumas'', ''Anatosaurus'', ''Anatotitan'', ''Claosaurus'', ''Hadrosaurus'', ''Thespesius'', and ''Trachodon'', and references predating the 1980s typically use ''Anatosaurus'', ''Claosaurus'', ''Thespesius'', or ''Trachodon'' for edmontosaur fossils (excluding those assigned to ''E. regalis''), depending on author and date. Although ''Edmontosaurus'' was only named in 1917, its oldest well-supported species (''E. annectens'') was named in 1892 as a species of ''Claosaurus''.

The first well-supported species of ''Edmontosaurus'' was named in 1892 as ''Claosaurus annectens'' by Othniel Charles Marsh. This species is holotype, based on National Museum of Natural History, USNM 2414, a partial skull-roof and skeleton, with a second skull and skeleton, Peabody Museum of Natural History, YPM 2182, designated the paratype. Both were collected in 1891 by John Bell Hatcher from the late Maastrichtian-age Upper Cretaceous Lance Formation of Niobrara County, Wyoming, Niobrara County (then part of Converse County, Wyoming, Converse County), Wyoming. This species has some historical footnotes attached: it is among the first dinosaurs to receive a skeletal restoration, and is the first hadrosaurid so restored; and YPM 2182 and UNSM 2414 are, respectively, the first and second essentially complete mounted dinosaur skeletons in the United States. YPM 2182 was put on display in 1901, and USNM 2414 in 1904.

Because of the incomplete understanding of hadrosaurids at the time, following Marsh's death in 1897 ''Claosaurus annectens'' was variously classified as a species of ''Claosaurus'', ''Thespesius'' or ''Trachodon''. Opinions varied greatly; textbooks and encyclopedias drew a distinction between the "''Iguanodon''-like" ''Claosaurus annectens'' and the "duck-billed" ''Hadrosaurus'' (based on remains now known as adult ''Edmontosaurus annectens''), while Hatcher explicitly identified ''C. annectens'' as synonymous with the hadrosaurid represented by those same duck-billed skulls. Hatcher's revision, published in 1902, was sweeping: he considered almost all hadrosaurid genera then known as synonyms of ''Trachodon''. This included ''Cionodon'', ''Diclonius'', ''Hadrosaurus'', ''Hadrosaurus, Ornithotarsus'', ''Pteropelyx'', and ''Thespesius'', as well as ''Claorhynchus'' and ''Polyonax'', fragmentary genera now thought to be ceratopsia, horned dinosaurs. Hatcher's work led to a brief consensus, until after 1910 new material from Canada and Montana showed a greater diversity of hadrosaurids than previously suspected. Charles W. Gilmore in 1915 reassessed hadrosaurids and recommended that ''Thespesius'' be reintroduced for hadrosaurids from the Lance Formation and rock units of equivalent age, and that ''Trachodon'', based on inadequate material, should be restricted to a hadrosaurid from the older Judith River Formation and its equivalents. In regards to ''Claosaurus annectens'', he recommended that it be considered the same as ''Thespesius occidentalis''. His reinstatement of ''Thespesius'' for Lance-age hadrosaurids would have other consequences for the taxonomy of ''Edmontosaurus'' in the following decades.

Because of the incomplete understanding of hadrosaurids at the time, following Marsh's death in 1897 ''Claosaurus annectens'' was variously classified as a species of ''Claosaurus'', ''Thespesius'' or ''Trachodon''. Opinions varied greatly; textbooks and encyclopedias drew a distinction between the "''Iguanodon''-like" ''Claosaurus annectens'' and the "duck-billed" ''Hadrosaurus'' (based on remains now known as adult ''Edmontosaurus annectens''), while Hatcher explicitly identified ''C. annectens'' as synonymous with the hadrosaurid represented by those same duck-billed skulls. Hatcher's revision, published in 1902, was sweeping: he considered almost all hadrosaurid genera then known as synonyms of ''Trachodon''. This included ''Cionodon'', ''Diclonius'', ''Hadrosaurus'', ''Hadrosaurus, Ornithotarsus'', ''Pteropelyx'', and ''Thespesius'', as well as ''Claorhynchus'' and ''Polyonax'', fragmentary genera now thought to be ceratopsia, horned dinosaurs. Hatcher's work led to a brief consensus, until after 1910 new material from Canada and Montana showed a greater diversity of hadrosaurids than previously suspected. Charles W. Gilmore in 1915 reassessed hadrosaurids and recommended that ''Thespesius'' be reintroduced for hadrosaurids from the Lance Formation and rock units of equivalent age, and that ''Trachodon'', based on inadequate material, should be restricted to a hadrosaurid from the older Judith River Formation and its equivalents. In regards to ''Claosaurus annectens'', he recommended that it be considered the same as ''Thespesius occidentalis''. His reinstatement of ''Thespesius'' for Lance-age hadrosaurids would have other consequences for the taxonomy of ''Edmontosaurus'' in the following decades.

During this time frame (1902–1915), two additional important specimens of ''C. annectens'' were recovered. The first, the Edmontosaurus mummy AMNH 5060, "mummy" specimen AMNH 5060, was discovered in 1908 by Charles Hazelius Sternberg and his sons in Lance Formation rocks near Lusk, Wyoming, Lusk, Wyoming. Sternberg was working for the Natural History Museum, London, British Museum of Natural History, but Henry Fairfield Osborn of the American Museum of Natural History was able to purchase the specimen for $2,000. The Sternbergs recovered a Edmontosaurus mummy in the Naturmuseum Senckenberg, second similar specimen from the same area in 1910, not as well preserved but also found with skin impressions. They sold this specimen (SM 4036) to the Senckenberg Museum in Germany.

As a side note, ''Trachodon selwyni'', described by Lawrence Lambe in 1902 for a lower jaw from what is now known as the Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, was erroneously described by Glut (1997) as having been assigned to ''Edmontosaurus regalis'' by Lull and Wright. It was not, instead being designated "of very doubtful validity."Lull, Richard Swann; and Wright, Nelda E. (1942). ''Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America''. pp. 220–221. More recent reviews of hadrosaurids have concurred.

During this time frame (1902–1915), two additional important specimens of ''C. annectens'' were recovered. The first, the Edmontosaurus mummy AMNH 5060, "mummy" specimen AMNH 5060, was discovered in 1908 by Charles Hazelius Sternberg and his sons in Lance Formation rocks near Lusk, Wyoming, Lusk, Wyoming. Sternberg was working for the Natural History Museum, London, British Museum of Natural History, but Henry Fairfield Osborn of the American Museum of Natural History was able to purchase the specimen for $2,000. The Sternbergs recovered a Edmontosaurus mummy in the Naturmuseum Senckenberg, second similar specimen from the same area in 1910, not as well preserved but also found with skin impressions. They sold this specimen (SM 4036) to the Senckenberg Museum in Germany.

As a side note, ''Trachodon selwyni'', described by Lawrence Lambe in 1902 for a lower jaw from what is now known as the Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, was erroneously described by Glut (1997) as having been assigned to ''Edmontosaurus regalis'' by Lull and Wright. It was not, instead being designated "of very doubtful validity."Lull, Richard Swann; and Wright, Nelda E. (1942). ''Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America''. pp. 220–221. More recent reviews of hadrosaurids have concurred.

Two more species that would come to be included with ''Edmontosaurus'' were named from Canadian remains in the 1920s, but both would initially be assigned to ''Thespesius''. Gilmore named the first, ''Thespesius edmontoni'', in 1924. ''T. edmontoni'' also came from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation. It was based on NMC 8399, another nearly complete skeleton lacking most of the tail. NMC 8399 was discovered on the Red Deer River in 1912 by a Sternberg party. Its forelimbs, ossified tendons, and skin impressions were briefly described in 1913 and 1914 by Lambe, who at first thought it was an example of a species he had named ''Trachodon marginatus'', but then changed his mind. The specimen became the first dinosaur skeleton to be mounted for exhibition in a Canadian museum. Gilmore found that his new species compared closely to what he called ''Thespesius annectens'', but left the two apart because of details of the arms and hands. He also noted that his species had more vertebrae than Marsh's in the back and neck, but proposed that Marsh was mistaken in assuming that the ''annectens'' specimens were complete in those regions.

In 1926, Charles Mortram Sternberg named ''Thespesius saskatchewanensis'' for NMC 8509, a skull and partial skeleton from the Wood Mountain plateau of southern Saskatchewan. He had collected this specimen in 1921, from rocks that were assigned to the Lance Formation, now the Frenchman Formation. NMC 8509 included an almost complete skull, numerous vertebrae, partial shoulder and hip girdles, and partial hind limbs, representing the first substantial dinosaur specimen recovered from Saskatchewan. Sternberg opted to assign it to ''Thespesius'' because that was the only hadrosaurid genus known from the Lance Formation at the time. At the time, ''T. saskatchewanensis'' was unusual because of its small size, estimated at in length.

Two more species that would come to be included with ''Edmontosaurus'' were named from Canadian remains in the 1920s, but both would initially be assigned to ''Thespesius''. Gilmore named the first, ''Thespesius edmontoni'', in 1924. ''T. edmontoni'' also came from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation. It was based on NMC 8399, another nearly complete skeleton lacking most of the tail. NMC 8399 was discovered on the Red Deer River in 1912 by a Sternberg party. Its forelimbs, ossified tendons, and skin impressions were briefly described in 1913 and 1914 by Lambe, who at first thought it was an example of a species he had named ''Trachodon marginatus'', but then changed his mind. The specimen became the first dinosaur skeleton to be mounted for exhibition in a Canadian museum. Gilmore found that his new species compared closely to what he called ''Thespesius annectens'', but left the two apart because of details of the arms and hands. He also noted that his species had more vertebrae than Marsh's in the back and neck, but proposed that Marsh was mistaken in assuming that the ''annectens'' specimens were complete in those regions.

In 1926, Charles Mortram Sternberg named ''Thespesius saskatchewanensis'' for NMC 8509, a skull and partial skeleton from the Wood Mountain plateau of southern Saskatchewan. He had collected this specimen in 1921, from rocks that were assigned to the Lance Formation, now the Frenchman Formation. NMC 8509 included an almost complete skull, numerous vertebrae, partial shoulder and hip girdles, and partial hind limbs, representing the first substantial dinosaur specimen recovered from Saskatchewan. Sternberg opted to assign it to ''Thespesius'' because that was the only hadrosaurid genus known from the Lance Formation at the time. At the time, ''T. saskatchewanensis'' was unusual because of its small size, estimated at in length.

In 1942, Lull and Wright attempted to resolve the complicated taxonomy of crestless hadrosaurids by naming a new genus, ''Anatosaurus'', to take in several species that did not fit well under their previous genera. ''Anatosaurus'', meaning "duck lizard", because of its wide, duck-like beak (Latin ''anas'' = duck + Ancient Greek, Greek ''sauros'' = lizard), had as its type species Marsh's old ''Claosaurus annectens''. Also assigned to this genus were ''Thespesius edmontoni'', ''T. saskatchewanensis'', a large lower jaw that Marsh had named ''Trachodon longiceps'' in 1890, and a new species, ''Anatosaurus copei'', for two skeletons on display at the American Museum of Natural History that had long been known as ''Diclonius mirabilis'' (or variations thereof). Thus, the various species became ''Anatosaurus annectens'', ''A. copei'', ''A. edmontoni'', ''A. longiceps'', and ''A. saskatchewanensis''. ''Anatosaurus'' would come to be called the "classic duck-billed dinosaur."

This state of affairs persisted for several decades, until Michael K. Brett-Surman reexamined the pertinent material for his graduate studies in the 1970s and 1980s. He concluded that the type species of ''Anatosaurus'', ''A. annectens'', was actually a species of ''Edmontosaurus'' and that ''A. copei'' was different enough to warrant its own genus. Although theses and dissertations are not regarded as official publications by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature, which regulates the naming of organisms, his conclusions were known to other paleontologists, and were adopted by several popular works of the time. Brett-Surman and Ralph Chapman designated a new genus for ''A. copei'' (''Anatotitan'') in 1990. Of the remaining species, ''A. saskatchewanensis'' and ''A. edmontoni'' were assigned to ''Edmontosaurus'' as well, and ''A. longiceps'' went to ''Anatotitan'', as either a second species or as a synonym of ''A. copei''. Because the type species of ''Anatosaurus'' (''A. annectens'') was sunk into ''Edmontosaurus'', the name ''Anatosaurus'' is abandoned as a synonym (taxonomy), junior synonym of ''Edmontosaurus''.

In 1942, Lull and Wright attempted to resolve the complicated taxonomy of crestless hadrosaurids by naming a new genus, ''Anatosaurus'', to take in several species that did not fit well under their previous genera. ''Anatosaurus'', meaning "duck lizard", because of its wide, duck-like beak (Latin ''anas'' = duck + Ancient Greek, Greek ''sauros'' = lizard), had as its type species Marsh's old ''Claosaurus annectens''. Also assigned to this genus were ''Thespesius edmontoni'', ''T. saskatchewanensis'', a large lower jaw that Marsh had named ''Trachodon longiceps'' in 1890, and a new species, ''Anatosaurus copei'', for two skeletons on display at the American Museum of Natural History that had long been known as ''Diclonius mirabilis'' (or variations thereof). Thus, the various species became ''Anatosaurus annectens'', ''A. copei'', ''A. edmontoni'', ''A. longiceps'', and ''A. saskatchewanensis''. ''Anatosaurus'' would come to be called the "classic duck-billed dinosaur."

This state of affairs persisted for several decades, until Michael K. Brett-Surman reexamined the pertinent material for his graduate studies in the 1970s and 1980s. He concluded that the type species of ''Anatosaurus'', ''A. annectens'', was actually a species of ''Edmontosaurus'' and that ''A. copei'' was different enough to warrant its own genus. Although theses and dissertations are not regarded as official publications by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature, which regulates the naming of organisms, his conclusions were known to other paleontologists, and were adopted by several popular works of the time. Brett-Surman and Ralph Chapman designated a new genus for ''A. copei'' (''Anatotitan'') in 1990. Of the remaining species, ''A. saskatchewanensis'' and ''A. edmontoni'' were assigned to ''Edmontosaurus'' as well, and ''A. longiceps'' went to ''Anatotitan'', as either a second species or as a synonym of ''A. copei''. Because the type species of ''Anatosaurus'' (''A. annectens'') was sunk into ''Edmontosaurus'', the name ''Anatosaurus'' is abandoned as a synonym (taxonomy), junior synonym of ''Edmontosaurus''.

The conception of ''Edmontosaurus'' that emerged included three valid species: the type ''E. regalis'', ''E. annectens'' (including ''Anatosaurus edmontoni'', amended to ''edmontonensis''), and ''E. saskatchewanensis''. The debate about the proper taxonomy of the ''A. copei'' specimens continues to the present: returning to Hatcher's argument of 1902, Jack Horner, David B. Weishampel, and Catherine Forster regarded ''Anatotitan copei'' as representing specimens of ''Edmontosaurus annectens'' with crushed skulls. In 2007 another "mummy" was announced; nicknamed "Dakota (fossil), Dakota", it was discovered in 1999 by Tyler Lyson, and came from the Hell Creek Formation of North Dakota.

In a 2011 study by Nicolás Campione and David Evans, the authors conducted the first ever morphometric analysis to compare the various specimens assigned to ''Edmontosaurus''. They concluded that only two species are valid: ''E. regalis'', from the late Campanian, and ''E. annectens'', from the late Maastrichtian. Their study provided further evidence that ''Anatotitan copei'' is a synonym of ''E. annectens''; specifically, that the long, low skull of ''A. copei'' is the result of ontogenetic change and represents mature ''E. annectens'' individuals.

The conception of ''Edmontosaurus'' that emerged included three valid species: the type ''E. regalis'', ''E. annectens'' (including ''Anatosaurus edmontoni'', amended to ''edmontonensis''), and ''E. saskatchewanensis''. The debate about the proper taxonomy of the ''A. copei'' specimens continues to the present: returning to Hatcher's argument of 1902, Jack Horner, David B. Weishampel, and Catherine Forster regarded ''Anatotitan copei'' as representing specimens of ''Edmontosaurus annectens'' with crushed skulls. In 2007 another "mummy" was announced; nicknamed "Dakota (fossil), Dakota", it was discovered in 1999 by Tyler Lyson, and came from the Hell Creek Formation of North Dakota.

In a 2011 study by Nicolás Campione and David Evans, the authors conducted the first ever morphometric analysis to compare the various specimens assigned to ''Edmontosaurus''. They concluded that only two species are valid: ''E. regalis'', from the late Campanian, and ''E. annectens'', from the late Maastrichtian. Their study provided further evidence that ''Anatotitan copei'' is a synonym of ''E. annectens''; specifically, that the long, low skull of ''A. copei'' is the result of ontogenetic change and represents mature ''E. annectens'' individuals.

''Edmontosaurus'' is currently regarded as having two valid species: type species ''E. regalis'', and ''E. annectens''. ''E. regalis'' is known only from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation of Alberta, dating from the late Campanian stage of the late Cretaceous period. At least a dozen individuals are known, including seven skulls with associated postcrania, and five to seven other skulls. The species formerly known as ''Thespesius edmontoni'' or ''Anatosaurus edmontoni'' represents immature individuals.Campione, N.E. (2009). "Cranial variation in ''Edmontosaurus'' (Hadrosauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of North America." ''North American Paleontological Convention (NAPC 2009): Abstracts'', p. 95a

''Edmontosaurus'' is currently regarded as having two valid species: type species ''E. regalis'', and ''E. annectens''. ''E. regalis'' is known only from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation of Alberta, dating from the late Campanian stage of the late Cretaceous period. At least a dozen individuals are known, including seven skulls with associated postcrania, and five to seven other skulls. The species formerly known as ''Thespesius edmontoni'' or ''Anatosaurus edmontoni'' represents immature individuals.Campione, N.E. (2009). "Cranial variation in ''Edmontosaurus'' (Hadrosauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of North America." ''North American Paleontological Convention (NAPC 2009): Abstracts'', p. 95a

PDF link

''E. annectens'' is known from the Frenchman Formation of Saskatchewan, the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, and the Lance Formation of South Dakota and Wyoming. It is limited to late Maastrichtian rocks, and is represented by at least twenty skulls, some with postcranial remains. One author, Kraig Derstler, has described ''E. annectens'' as "perhaps the most perfectly-known dinosaur to date [1994]." ''Anatosaurus copei'' and ''E. saskatchewanensis'' are now thought to be growth stages of ''E. annectens'': ''A. copei'' as adults, and ''E. saskatchewanensis'' as juveniles. ''Trachodon longiceps'' may be a synonym of ''E. annectens'' as well. ''Anatosaurus edmontoni'' was mistakenly listed as a synonym of ''E. annectens'' in both reviews of the Dinosauria, but this does not appear to be the case. ''E. annectens'' differed from ''E. regalis'' by having a longer, lower, less robust skull. Although Brett-Surman regarded ''E. regalis'' and ''E. annectens'' as potentially representing males and females of the same species, all ''E. regalis'' specimens come from older formations than ''E. annectens'' specimens. Edmontosaurine specimens from the Prince Creek Formation of Alaska formerly assigned to ''Edmontosaurus'' sp. were given their own genus and species name, ''Ugrunaaluk kuukpikensis'', in 2015. However, the identification of ''Ugrunaaluk'' as a separate genus was questioned by a 2017 study from Hai Xing and colleagues, who regarded it as a ''nomen dubium'' indistinguishable from other ''Edmontosaurus''. In 2020, Ryuji Takasaki and colleagues agreed that the Prince Creek remains should be classified as ''Edmontosaurus'', though species designation is unclear as the specimens are juveniles. ''Edmontosaurus'' was also reported from the Javelina Formation of Big Bend National Park, western Texas based on TMM 41442-1, but was later referred to ''Kritosaurus cf. navajovius'' by Wagner (2001), before being assigned to ''Kritosaurus'' sp. by Lehman ''et al.'' (2016).

''E. annectens'' differed from ''E. regalis'' by having a longer, lower, less robust skull. Although Brett-Surman regarded ''E. regalis'' and ''E. annectens'' as potentially representing males and females of the same species, all ''E. regalis'' specimens come from older formations than ''E. annectens'' specimens. Edmontosaurine specimens from the Prince Creek Formation of Alaska formerly assigned to ''Edmontosaurus'' sp. were given their own genus and species name, ''Ugrunaaluk kuukpikensis'', in 2015. However, the identification of ''Ugrunaaluk'' as a separate genus was questioned by a 2017 study from Hai Xing and colleagues, who regarded it as a ''nomen dubium'' indistinguishable from other ''Edmontosaurus''. In 2020, Ryuji Takasaki and colleagues agreed that the Prince Creek remains should be classified as ''Edmontosaurus'', though species designation is unclear as the specimens are juveniles. ''Edmontosaurus'' was also reported from the Javelina Formation of Big Bend National Park, western Texas based on TMM 41442-1, but was later referred to ''Kritosaurus cf. navajovius'' by Wagner (2001), before being assigned to ''Kritosaurus'' sp. by Lehman ''et al.'' (2016).

''Edmontosaurus'' was among the largest hadrosaurids. Like other hadrosaurids, it was a bulky animal with a long, laterally flattened tail and a head with an expanded, duck-like beak. The fore legs were not as heavily built as the hind legs, but were long enough to be used in standing or movement. depending on the species, previous estimates suggested that a fully grown adult could have been long, and some of the larger specimens reached the range of Lull, Richard Swann; and Wright, Nelda E. (1942). ''Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America''. p. 225. with a body mass on the order of .

''Edmontosaurus'' was among the largest hadrosaurids. Like other hadrosaurids, it was a bulky animal with a long, laterally flattened tail and a head with an expanded, duck-like beak. The fore legs were not as heavily built as the hind legs, but were long enough to be used in standing or movement. depending on the species, previous estimates suggested that a fully grown adult could have been long, and some of the larger specimens reached the range of Lull, Richard Swann; and Wright, Nelda E. (1942). ''Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America''. p. 225. with a body mass on the order of .

''E. annectens'' is often seen as smaller. Two mounted skeletons, National Museum of Natural History, USNM 2414 and Peabody Museum of Natural History, YPM 2182, measure long and long, respectively. However, these are probably subadult individuals, and there is at least one report of a much larger potential ''E. annectens'' specimen, almost long. Two specimens still under study in the collection of the Museum of the Rockies - a tail labelled as MOR 1142 and another labelled as MOR 1609 - indicate that ''Edmontosaurus annectens'' could have grown to larger sizes, possibly rivaling ''Shantungosaurus'' in size. The individuals to which these specimens belong may have reached nearly in length and weighed , but such large individuals were likely very rare.

A 2022 study on the osteohistology and growth of ''E. annectens'' suggested that previous estimates might have underestimated or overestimated the size of this dinosaur and proposed that a fully grown adult ''E. annectens'' would have measured up to in length and approximately in average asymptotic body mass, while the largest individuals measured more than , even up to , based on the comparison between various specimens of different sizes from the Ruth Mason Dinosaur Quarry and other specimens from different localities; according to this analysis, ''E. regalis'' may have been heavier, but not enough samples exist to provide a valid estimate and examination on its osteohistology and growth, so the results for ''E. regalis'' aren't statistically significant.

''E. annectens'' is often seen as smaller. Two mounted skeletons, National Museum of Natural History, USNM 2414 and Peabody Museum of Natural History, YPM 2182, measure long and long, respectively. However, these are probably subadult individuals, and there is at least one report of a much larger potential ''E. annectens'' specimen, almost long. Two specimens still under study in the collection of the Museum of the Rockies - a tail labelled as MOR 1142 and another labelled as MOR 1609 - indicate that ''Edmontosaurus annectens'' could have grown to larger sizes, possibly rivaling ''Shantungosaurus'' in size. The individuals to which these specimens belong may have reached nearly in length and weighed , but such large individuals were likely very rare.

A 2022 study on the osteohistology and growth of ''E. annectens'' suggested that previous estimates might have underestimated or overestimated the size of this dinosaur and proposed that a fully grown adult ''E. annectens'' would have measured up to in length and approximately in average asymptotic body mass, while the largest individuals measured more than , even up to , based on the comparison between various specimens of different sizes from the Ruth Mason Dinosaur Quarry and other specimens from different localities; according to this analysis, ''E. regalis'' may have been heavier, but not enough samples exist to provide a valid estimate and examination on its osteohistology and growth, so the results for ''E. regalis'' aren't statistically significant.

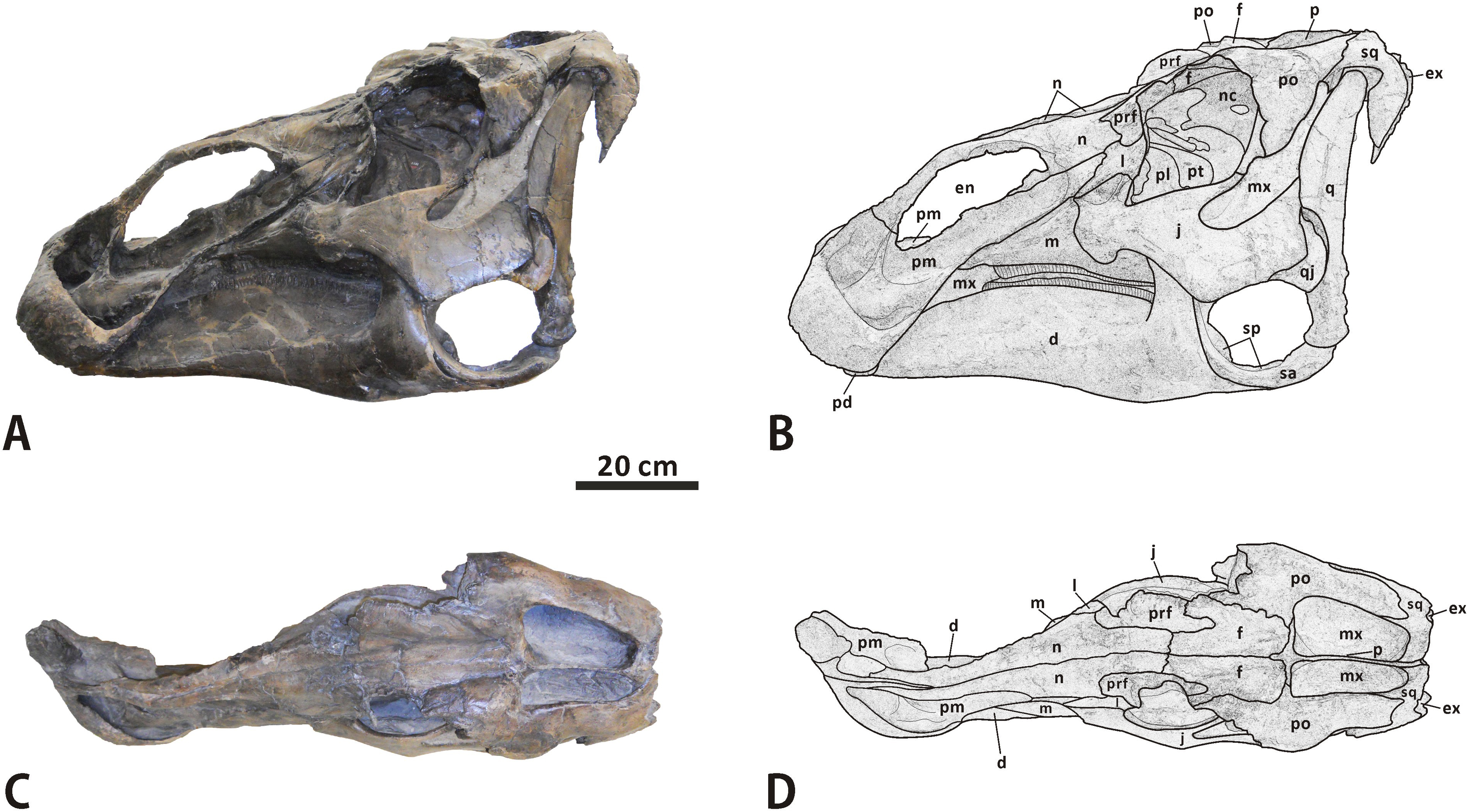

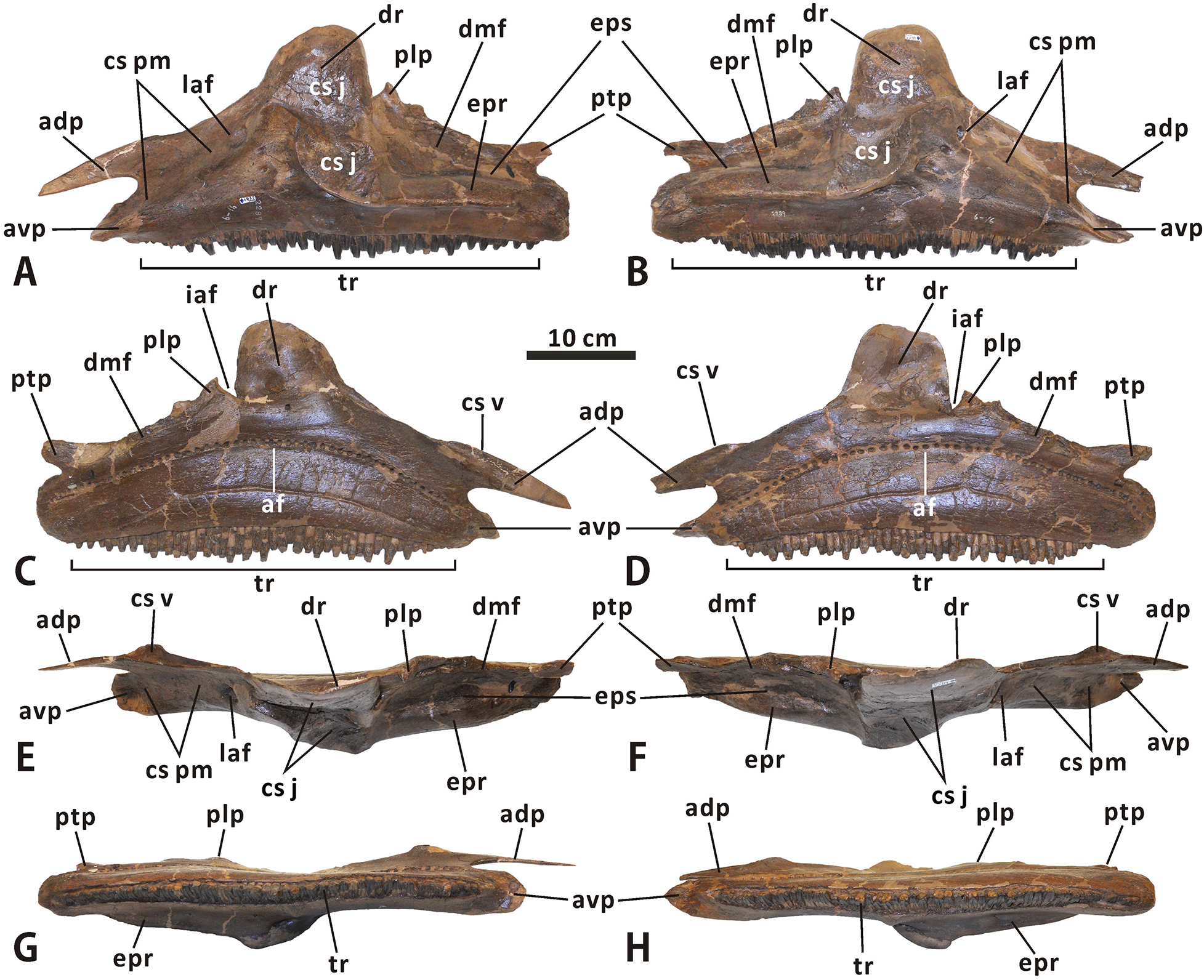

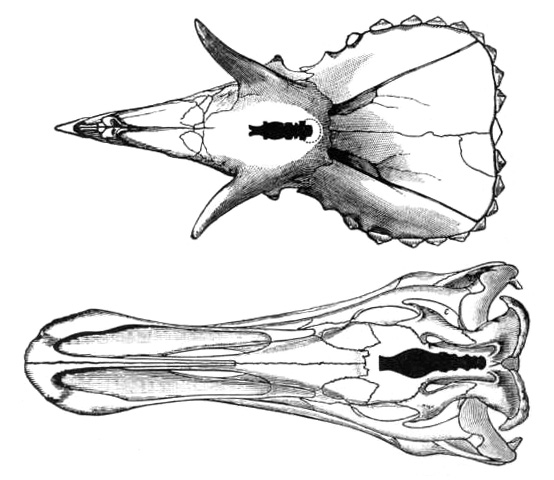

The skull of a fully grown ''Edmontosaurus'' could be over a metre long. One skull of ''E. annectens'' (formerly ''Anatotitan'') measures long. The skull was roughly triangular in profile, with no bony cranial crest.Lull, Richard Swann; and Wright, Nelda E. (1942). ''Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America''. pp. 151–164. Viewed from above, the front and rear of the skull were expanded, with the broad front forming a duck-bill or spoonbill, spoon-bill shape. The beak was toothless, and both the upper and lower beaks were extended by keratinous material. Substantial remains of the keratinous upper beak are known from Edmontosaurus mummy S.M. R4036, the "mummy" kept at the Senckenberg Museum. In this specimen, the preserved nonbony part of the beak extended for at least beyond the bone, projecting down vertically.Lull, Richard Swann; and Wright, Nelda E. (1942). ''Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America''. pp. 110–117. The nasal openings of ''Edmontosaurus'' were elongate and housed in deep depressions surrounded by distinct bony rims above, behind, and below.

In at least one case (the Senckenberg specimen), rarely preserved sclerotic rings were preserved in the eye sockets.Lull, Richard Swann; and Wright, Nelda E. (1942). ''Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America''. pp. 128–130. Another rarely seen bone, the stapes (the reptilian ear bone), has also been seen in a specimen of ''Edmontosaurus''.

The skull of a fully grown ''Edmontosaurus'' could be over a metre long. One skull of ''E. annectens'' (formerly ''Anatotitan'') measures long. The skull was roughly triangular in profile, with no bony cranial crest.Lull, Richard Swann; and Wright, Nelda E. (1942). ''Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America''. pp. 151–164. Viewed from above, the front and rear of the skull were expanded, with the broad front forming a duck-bill or spoonbill, spoon-bill shape. The beak was toothless, and both the upper and lower beaks were extended by keratinous material. Substantial remains of the keratinous upper beak are known from Edmontosaurus mummy S.M. R4036, the "mummy" kept at the Senckenberg Museum. In this specimen, the preserved nonbony part of the beak extended for at least beyond the bone, projecting down vertically.Lull, Richard Swann; and Wright, Nelda E. (1942). ''Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America''. pp. 110–117. The nasal openings of ''Edmontosaurus'' were elongate and housed in deep depressions surrounded by distinct bony rims above, behind, and below.

In at least one case (the Senckenberg specimen), rarely preserved sclerotic rings were preserved in the eye sockets.Lull, Richard Swann; and Wright, Nelda E. (1942). ''Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America''. pp. 128–130. Another rarely seen bone, the stapes (the reptilian ear bone), has also been seen in a specimen of ''Edmontosaurus''.

Teeth were present only in the maxillae (upper cheeks) and dentaries (main bone of the lower jaw). The teeth were continually replaced, taking about half a year to form. They were composed of six types of tissues, rivaling the complexity of mammal teeth. They grew in columns, with an observed maximum of six in each, and the number of columns varied based on the animal's size. Known column counts for the two species are: 51 to 53 columns per maxilla and 48 to 49 per dentary (teeth of the upper jaw being slightly narrower than those in the lower jaw) for ''E. regalis''; and 52 columns per maxilla and 44 per dentary for ''E. annectens'' (an ''E. saskatchewanensis'' specimen).

Teeth were present only in the maxillae (upper cheeks) and dentaries (main bone of the lower jaw). The teeth were continually replaced, taking about half a year to form. They were composed of six types of tissues, rivaling the complexity of mammal teeth. They grew in columns, with an observed maximum of six in each, and the number of columns varied based on the animal's size. Known column counts for the two species are: 51 to 53 columns per maxilla and 48 to 49 per dentary (teeth of the upper jaw being slightly narrower than those in the lower jaw) for ''E. regalis''; and 52 columns per maxilla and 44 per dentary for ''E. annectens'' (an ''E. saskatchewanensis'' specimen).

The number of vertebrae differs between specimens. ''E. regalis'' had thirteen neck vertebrae, eighteen back vertebrae, nine hip vertebrae, and an unknown number of tail vertebrae. A specimen once identified as belonging to ''Anatosaurus edmontoni'' (now considered to be the same as ''E. regalis'') is reported as having an additional back vertebra and 85 tail vertebrae, with an undisclosed amount of restoration. Other hadrosaurids are only reported as having 50 to 70 tail vertebrae, so this appears to have been an overestimate. The anatomical terms of location, anterior back was curved toward the ground, with the neck flexed upward and the rest of the back and tail held horizontally. Most of the back and tail were lined by ossification, ossified tendons arranged in a latticework along the spinous process, neural spines of the vertebrae. This condition has been described as making the back and at least part of the tail "ramrod" straight. The ossified tendons are interpreted as having strengthened the vertebral column against gravitational stress, incurred through being a large animal with a horizontal vertebral column otherwise supported mostly by the hind legs and hips.

The scapula, shoulder blades were long flat blade-like bones, held roughly parallel to the vertebral column. The pelvis, hips were composed of three elements each: an elongate ilium (bone), ilium above the articulation with the leg, an ischium below and behind with a long thin rod, and a pubis (bone), pubis in front that flared into a plate-like structure. The structure of the hip hindered the animal from standing with its back erect, because in such a position the femur, thigh bone would have pushed against the joint of the ilium and pubis, instead of pushing only against the solid ilium. The nine fused hip vertebrae provided support for the hip.

The fore legs were shorter and less heavily built than the hind legs. The humerus, upper arm had a large deltopectoral crest for muscle attachment, while the ulna and radius (bone), radius were slim. The upper arm and forearm were similar in length. The Carpal bones, wrist was simple, with only two small bones. Each hand had four fingers, with no thumb (first finger). The index (second), third, and fourth fingers were approximately the same length and were united in life within a fleshy covering. Although the second and third finger had hoof-like unguals, these bones were also within the skin and not apparent from the outside. The little finger diverged from the other three and was much shorter. The thigh bone was robust and straight, with a prominent fourth trochanter, flange about halfway down the anatomical terms of location, posterior side. This ridge was for the attachment of powerful muscles attached to the hips and tail that pulled the thighs (and thus the hind legs) backward and helped maintain the use of the tail as a balancing organ.Lull, Richard Swann; and Wright, Nelda E. (1942). ''Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America''. pp. 98–110. Each foot had three toes, with no big toe or little toe. The toes had hoof-like tips.

The number of vertebrae differs between specimens. ''E. regalis'' had thirteen neck vertebrae, eighteen back vertebrae, nine hip vertebrae, and an unknown number of tail vertebrae. A specimen once identified as belonging to ''Anatosaurus edmontoni'' (now considered to be the same as ''E. regalis'') is reported as having an additional back vertebra and 85 tail vertebrae, with an undisclosed amount of restoration. Other hadrosaurids are only reported as having 50 to 70 tail vertebrae, so this appears to have been an overestimate. The anatomical terms of location, anterior back was curved toward the ground, with the neck flexed upward and the rest of the back and tail held horizontally. Most of the back and tail were lined by ossification, ossified tendons arranged in a latticework along the spinous process, neural spines of the vertebrae. This condition has been described as making the back and at least part of the tail "ramrod" straight. The ossified tendons are interpreted as having strengthened the vertebral column against gravitational stress, incurred through being a large animal with a horizontal vertebral column otherwise supported mostly by the hind legs and hips.

The scapula, shoulder blades were long flat blade-like bones, held roughly parallel to the vertebral column. The pelvis, hips were composed of three elements each: an elongate ilium (bone), ilium above the articulation with the leg, an ischium below and behind with a long thin rod, and a pubis (bone), pubis in front that flared into a plate-like structure. The structure of the hip hindered the animal from standing with its back erect, because in such a position the femur, thigh bone would have pushed against the joint of the ilium and pubis, instead of pushing only against the solid ilium. The nine fused hip vertebrae provided support for the hip.

The fore legs were shorter and less heavily built than the hind legs. The humerus, upper arm had a large deltopectoral crest for muscle attachment, while the ulna and radius (bone), radius were slim. The upper arm and forearm were similar in length. The Carpal bones, wrist was simple, with only two small bones. Each hand had four fingers, with no thumb (first finger). The index (second), third, and fourth fingers were approximately the same length and were united in life within a fleshy covering. Although the second and third finger had hoof-like unguals, these bones were also within the skin and not apparent from the outside. The little finger diverged from the other three and was much shorter. The thigh bone was robust and straight, with a prominent fourth trochanter, flange about halfway down the anatomical terms of location, posterior side. This ridge was for the attachment of powerful muscles attached to the hips and tail that pulled the thighs (and thus the hind legs) backward and helped maintain the use of the tail as a balancing organ.Lull, Richard Swann; and Wright, Nelda E. (1942). ''Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America''. pp. 98–110. Each foot had three toes, with no big toe or little toe. The toes had hoof-like tips.

''Edmontosaurus'' was a hadrosaurid (a duck-billed dinosaur), a member of a family (biology), family of dinosaurs which to date are known only from the Late Cretaceous. It is classified within the Saurolophinae (alternately Hadrosaurinae), a clade of hadrosaurids which lacked hollow crests. Other members of the group include ''Brachylophosaurus'', ''Gryposaurus'', ''Lophorhothon'', ''Maiasaura'', ''Naashoibitosaurus'', ''Prosaurolophus'', and ''Saurolophus''. It was either closely related to or includes the species ''Anatosaurus annectens'' (alternately ''Edmontosaurus annectens''), a large hadrosaurid from various latest Cretaceous formation (stratigraphy), formations of western North America. The giant Chinese hadrosaurine ''Shantungosaurus giganteus'' is also anatomically similar to ''Edmontosaurus''; M. K. Brett-Surman found the two to differ only in details related to the greater size of ''Shantungosaurus'', based on what had been described of the latter genus.

While the status of ''Edmontosaurus'' as a saurolophine has not been challenged, its exact placement within the clade is uncertain. Early phylogenetics, phylogenies, such as that presented in R. S. Lull and Nelda Wright's influential 1942 monograph, had ''Edmontosaurus'' and various species of ''Anatosaurus'' (most of which would be later considered as additional species or specimens of ''Edmontosaurus'') as one lineage among several lineages of "flat-headed" hadrosaurs.Lull, Richard Swann; and Wright, Nelda E. (1942). ''Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America''. p. 48. One of the first analyses using cladistics, cladistic methods found it to be linked with ''Anatosaurus'' (=''Anatotitan'') and ''Shantungosaurus'' in an informal "edmontosaur" clade, which was paired with the spike-crested "saurolophs" and more distantly related to the "brachylophosaurs" and arch-snouted "gryposaurs". A 2007 study by Terry Gates and Scott Sampson found broadly similar results, in that ''Edmontosaurus'' remained close to ''Saurolophus'' and ''Prosaurolophus'' and distant from ''Gryposaurus'', ''Brachylophosaurus'', and ''Maiasaura''. However, the most recent review of Hadrosauridae, by Jack Horner (paleontologist), Jack Horner and colleagues (2004), came to a noticeably different result: ''Edmontosaurus'' was nested between ''Gryposaurus'' and the "brachylophosaurs", and distant from ''Saurolophus''.

Left cladistics, cladogram per Horner ''et al.'' (2004), right cladogram per Gates and Sampson (2007).

''Edmontosaurus'' was a hadrosaurid (a duck-billed dinosaur), a member of a family (biology), family of dinosaurs which to date are known only from the Late Cretaceous. It is classified within the Saurolophinae (alternately Hadrosaurinae), a clade of hadrosaurids which lacked hollow crests. Other members of the group include ''Brachylophosaurus'', ''Gryposaurus'', ''Lophorhothon'', ''Maiasaura'', ''Naashoibitosaurus'', ''Prosaurolophus'', and ''Saurolophus''. It was either closely related to or includes the species ''Anatosaurus annectens'' (alternately ''Edmontosaurus annectens''), a large hadrosaurid from various latest Cretaceous formation (stratigraphy), formations of western North America. The giant Chinese hadrosaurine ''Shantungosaurus giganteus'' is also anatomically similar to ''Edmontosaurus''; M. K. Brett-Surman found the two to differ only in details related to the greater size of ''Shantungosaurus'', based on what had been described of the latter genus.

While the status of ''Edmontosaurus'' as a saurolophine has not been challenged, its exact placement within the clade is uncertain. Early phylogenetics, phylogenies, such as that presented in R. S. Lull and Nelda Wright's influential 1942 monograph, had ''Edmontosaurus'' and various species of ''Anatosaurus'' (most of which would be later considered as additional species or specimens of ''Edmontosaurus'') as one lineage among several lineages of "flat-headed" hadrosaurs.Lull, Richard Swann; and Wright, Nelda E. (1942). ''Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America''. p. 48. One of the first analyses using cladistics, cladistic methods found it to be linked with ''Anatosaurus'' (=''Anatotitan'') and ''Shantungosaurus'' in an informal "edmontosaur" clade, which was paired with the spike-crested "saurolophs" and more distantly related to the "brachylophosaurs" and arch-snouted "gryposaurs". A 2007 study by Terry Gates and Scott Sampson found broadly similar results, in that ''Edmontosaurus'' remained close to ''Saurolophus'' and ''Prosaurolophus'' and distant from ''Gryposaurus'', ''Brachylophosaurus'', and ''Maiasaura''. However, the most recent review of Hadrosauridae, by Jack Horner (paleontologist), Jack Horner and colleagues (2004), came to a noticeably different result: ''Edmontosaurus'' was nested between ''Gryposaurus'' and the "brachylophosaurs", and distant from ''Saurolophus''.

Left cladistics, cladogram per Horner ''et al.'' (2004), right cladogram per Gates and Sampson (2007).

As a hadrosaurid, ''Edmontosaurus'' was a large terrestrial herbivore. Its teeth were continually replaced and packed into dental batteries that contained hundreds of teeth, only a relative handful of which were in use at any time. It used its broad beak to cut loose food, perhaps by cropping, or by closing the jaws in a clamshell-like manner over twigs and branches and then stripping off the more nutritious leaves and shoots. Because the tooth rows are deeply indented from the outside of the jaws, and because of other anatomical details, it is inferred that ''Edmontosaurus'' and most other ornithischians had cheek-like structures, muscular or non-muscular. The function of the cheeks was to retain food in the mouth.Fastovsky, D.E., and Smith, J.B. (2004). "Dinosaur paleoecology." ''The Dinosauria''. pp. 614–626. The animal's feeding range would have been from ground level to around above.

Before the 1960s and 1970s, the prevailing interpretation of hadrosaurids like ''Edmontosaurus'' was that they were aquatic and fed on aquatic plants. An example of this is William Morris's 1970 interpretation of an edmontosaur skull with nonbony beak remnants. He proposed that the animal had a diet much like that of some modern ducks, filtering plants and aquatic invertebrates like mollusca, mollusks and crustaceans from the water and discharging water via V-shaped furrows along the inner face of the upper beak. This interpretation of the beak has been rejected, as the furrows and ridges are more like those of herbivorous turtle beaks than the flexible structures seen in filter-feeding birds.

Because scratches dominate the microwear texture of the teeth, Williams ''et al.'' suggested ''Edmontosaurus'' was a Grazing (behaviour), grazer instead of a Browsing (herbivory), browser, which would be predicted to have fewer scratches due to eating less abrasive materials. Candidates for ingested abrasives include silicon dioxide, silica-rich plants like equisetum, horsetails and soil that was accidentally ingested due to feeding at ground level. The tooth structure indicates combined slicing and grinding capabilities.

Reports of gastroliths, or stomach stones, in the hadrosaurid ''Claosaurus'' is actually based on a probable double misidentification. First, the specimen is actually of ''Edmontosaurus annectens''. Barnum Brown, who discovered the specimen in 1900, referred to it as ''Claosaurus'' because ''E. annectens'' was thought to be a species of ''Claosaurus'' at the time. Additionally, it is more likely that the supposed gastroliths represent gravel washed in during burial.

As a hadrosaurid, ''Edmontosaurus'' was a large terrestrial herbivore. Its teeth were continually replaced and packed into dental batteries that contained hundreds of teeth, only a relative handful of which were in use at any time. It used its broad beak to cut loose food, perhaps by cropping, or by closing the jaws in a clamshell-like manner over twigs and branches and then stripping off the more nutritious leaves and shoots. Because the tooth rows are deeply indented from the outside of the jaws, and because of other anatomical details, it is inferred that ''Edmontosaurus'' and most other ornithischians had cheek-like structures, muscular or non-muscular. The function of the cheeks was to retain food in the mouth.Fastovsky, D.E., and Smith, J.B. (2004). "Dinosaur paleoecology." ''The Dinosauria''. pp. 614–626. The animal's feeding range would have been from ground level to around above.

Before the 1960s and 1970s, the prevailing interpretation of hadrosaurids like ''Edmontosaurus'' was that they were aquatic and fed on aquatic plants. An example of this is William Morris's 1970 interpretation of an edmontosaur skull with nonbony beak remnants. He proposed that the animal had a diet much like that of some modern ducks, filtering plants and aquatic invertebrates like mollusca, mollusks and crustaceans from the water and discharging water via V-shaped furrows along the inner face of the upper beak. This interpretation of the beak has been rejected, as the furrows and ridges are more like those of herbivorous turtle beaks than the flexible structures seen in filter-feeding birds.

Because scratches dominate the microwear texture of the teeth, Williams ''et al.'' suggested ''Edmontosaurus'' was a Grazing (behaviour), grazer instead of a Browsing (herbivory), browser, which would be predicted to have fewer scratches due to eating less abrasive materials. Candidates for ingested abrasives include silicon dioxide, silica-rich plants like equisetum, horsetails and soil that was accidentally ingested due to feeding at ground level. The tooth structure indicates combined slicing and grinding capabilities.

Reports of gastroliths, or stomach stones, in the hadrosaurid ''Claosaurus'' is actually based on a probable double misidentification. First, the specimen is actually of ''Edmontosaurus annectens''. Barnum Brown, who discovered the specimen in 1900, referred to it as ''Claosaurus'' because ''E. annectens'' was thought to be a species of ''Claosaurus'' at the time. Additionally, it is more likely that the supposed gastroliths represent gravel washed in during burial.

Both of the "mummy" specimens collected by the Sternbergs were reported to have had possible gut contents. Charles H. Sternberg reported the presence of carbonization, carbonized gut contents in the American Museum of Natural History specimen, but this material has not been described. The plant remains in the Senckenberg Museum specimen have been described, but have proven difficult to interpret. The plants found in the carcass included needles of the conifer ''Cunninghamites elegans'', twigs from conifer and broadleaf trees, and numerous small seeds or fruits. Upon their description in 1922, they were the subject of a debate in the German-language journal ''Paläontologische Zeitschrift''. Kräusel, who described the material, interpreted it as the gut contents of the animal, while Abel could not rule out that the plants had been washed into the carcass after death.

At the time, hadrosaurids were thought to have been aquatic animals, and Kräusel made a point of stating that the specimen did not rule out hadrosaurids eating water plants. The discovery of possible gut contents made little impact in English-speaking circles, except for another brief mention of the aquatic-terrestrial dichotomy, until it was brought up by John Ostrom in the course of an article reassessing the old interpretation of hadrosaurids as water-bound. Instead of trying to adapt the discovery to the aquatic model, he used it as a line of evidence that hadrosaurids were terrestrial herbivores. While his interpretation of hadrosaurids as terrestrial animals has been generally accepted, the Senckenberg plant fossils remain equivocal. Kenneth Carpenter has suggested that they may actually represent the gut contents of a starving animal, instead of a typical diet. Other authors have noted that because the plant fossils were removed from their original context in the specimen and were heavily prepared, it is no longer possible to follow up on the original work, leaving open the possibility that the plants were washed-in debris.

Both of the "mummy" specimens collected by the Sternbergs were reported to have had possible gut contents. Charles H. Sternberg reported the presence of carbonization, carbonized gut contents in the American Museum of Natural History specimen, but this material has not been described. The plant remains in the Senckenberg Museum specimen have been described, but have proven difficult to interpret. The plants found in the carcass included needles of the conifer ''Cunninghamites elegans'', twigs from conifer and broadleaf trees, and numerous small seeds or fruits. Upon their description in 1922, they were the subject of a debate in the German-language journal ''Paläontologische Zeitschrift''. Kräusel, who described the material, interpreted it as the gut contents of the animal, while Abel could not rule out that the plants had been washed into the carcass after death.

At the time, hadrosaurids were thought to have been aquatic animals, and Kräusel made a point of stating that the specimen did not rule out hadrosaurids eating water plants. The discovery of possible gut contents made little impact in English-speaking circles, except for another brief mention of the aquatic-terrestrial dichotomy, until it was brought up by John Ostrom in the course of an article reassessing the old interpretation of hadrosaurids as water-bound. Instead of trying to adapt the discovery to the aquatic model, he used it as a line of evidence that hadrosaurids were terrestrial herbivores. While his interpretation of hadrosaurids as terrestrial animals has been generally accepted, the Senckenberg plant fossils remain equivocal. Kenneth Carpenter has suggested that they may actually represent the gut contents of a starving animal, instead of a typical diet. Other authors have noted that because the plant fossils were removed from their original context in the specimen and were heavily prepared, it is no longer possible to follow up on the original work, leaving open the possibility that the plants were washed-in debris.

The diet and physiology of ''Edmontosaurus'' have been probed by using stable isotopes of carbon and oxygen as recorded in tooth enamel. When feeding, drinking, and breathing, animals take in carbon and oxygen, which become incorporated into bone. The isotopes of these two elements are determined by various internal and external factors, such as the type of plants being eaten, the physiology of the animal, salinity, and climate. If isotope ratios in fossils are not altered by fossilization and later diagenesis, changes, they can be studied for information about the original factors; endothermy, warmblooded animals will have certain isotopic compositions compared to their surroundings, animals that eat certain types of plants or use certain digestive processes will have distinct isotopic compositions, and so on. Enamel is typically used because the structure of the mineral that forms enamel makes it the most resistant material to chemical change in the skeleton.

A 2004 study by Kathryn Thomas and Sandra Carlson used teeth from the upper jaw of three individuals interpreted as a juvenile, a subadult, and an adult, recovered from a bone bed in the Hell Creek Formation of Corson County, South Dakota, Corson County, South Dakota. In this study, successive teeth in columns in the edmontosaurs' dental batteries were sampled from multiple locations along each tooth using a microdrilling system. This sampling method takes advantage of the organization of hadrosaurid dental batteries to find variation in tooth isotopes over a period of time. From their work, it appears that edmontosaur teeth took less than about 0.65 years to form, slightly faster in younger edmontosaurs. The teeth of all three individuals appeared to show variation in oxygen isotope ratios that could correspond to warm/dry and cool/wet periods; Thomas and Carlson considered the possibility that the animals were migrating instead, but favored local seasonal variations because migration would have more likely led to ratio homogenization, as many animals migrate to stay within specific temperature ranges or near particular food sources.

The edmontosaurs also showed enriched carbon isotope values, which for modern mammals would be interpreted as a mixed diet of C3 carbon fixation, C3 plants (most plants) and C4 carbon fixation, C4 plants (grasses); however, C4 plants were extremely rare in the Late Cretaceous if present at all. Thomas and Carlson put forward several factors that may have been operating, and found the most likely to include a diet heavy in gymnosperms, consuming salt-stressed plants from coastal areas adjacent to the Western Interior Seaway, and a physiological difference between dinosaurs and mammals that caused dinosaurs to form tissue with different carbon ratios than would be expected for mammals. A combination of factors is also possible.

The diet and physiology of ''Edmontosaurus'' have been probed by using stable isotopes of carbon and oxygen as recorded in tooth enamel. When feeding, drinking, and breathing, animals take in carbon and oxygen, which become incorporated into bone. The isotopes of these two elements are determined by various internal and external factors, such as the type of plants being eaten, the physiology of the animal, salinity, and climate. If isotope ratios in fossils are not altered by fossilization and later diagenesis, changes, they can be studied for information about the original factors; endothermy, warmblooded animals will have certain isotopic compositions compared to their surroundings, animals that eat certain types of plants or use certain digestive processes will have distinct isotopic compositions, and so on. Enamel is typically used because the structure of the mineral that forms enamel makes it the most resistant material to chemical change in the skeleton.

A 2004 study by Kathryn Thomas and Sandra Carlson used teeth from the upper jaw of three individuals interpreted as a juvenile, a subadult, and an adult, recovered from a bone bed in the Hell Creek Formation of Corson County, South Dakota, Corson County, South Dakota. In this study, successive teeth in columns in the edmontosaurs' dental batteries were sampled from multiple locations along each tooth using a microdrilling system. This sampling method takes advantage of the organization of hadrosaurid dental batteries to find variation in tooth isotopes over a period of time. From their work, it appears that edmontosaur teeth took less than about 0.65 years to form, slightly faster in younger edmontosaurs. The teeth of all three individuals appeared to show variation in oxygen isotope ratios that could correspond to warm/dry and cool/wet periods; Thomas and Carlson considered the possibility that the animals were migrating instead, but favored local seasonal variations because migration would have more likely led to ratio homogenization, as many animals migrate to stay within specific temperature ranges or near particular food sources.

The edmontosaurs also showed enriched carbon isotope values, which for modern mammals would be interpreted as a mixed diet of C3 carbon fixation, C3 plants (most plants) and C4 carbon fixation, C4 plants (grasses); however, C4 plants were extremely rare in the Late Cretaceous if present at all. Thomas and Carlson put forward several factors that may have been operating, and found the most likely to include a diet heavy in gymnosperms, consuming salt-stressed plants from coastal areas adjacent to the Western Interior Seaway, and a physiological difference between dinosaurs and mammals that caused dinosaurs to form tissue with different carbon ratios than would be expected for mammals. A combination of factors is also possible.

Weishampel developed his model with the aid of a computer simulation. Natalia Rybczynski and colleagues have updated this work with a much more sophisticated Three-dimensional space, three-dimensional animation model, scanning a skull of ''E. regalis'' with lasers. They were able to replicate the proposed motion with their model, although they found that additional secondary movements between other bones were required, with maximum separations of between some bones during the chewing cycle. Rybczynski and colleagues were not convinced that the Weishampel model is viable, but noted that they have several improvements to implement to their animation. Planned improvements include incorporating soft tissue and tooth wear marks and scratches, which should better constrain movements. They note that there are several other hypotheses to test as well. Further research published in 2012 by Robin Cuthbertson and colleagues found the motions required for Weishampel's model to be unlikely, and favored a model in which movements of the lower jaw produced grinding action. The lower jaw's joint with the upper jaw would permit anterior–posterior motion along with the usual rotation, and the anterior joint of the two halves of the lower jaw would also permit motion; in combination, the two halves of the lower jaw could move slightly back and forth as well as rotating slightly along their long axes. These motions would account for the observed tooth wear and a more solidly constructed skull than modeled by Weishampel.

Weishampel developed his model with the aid of a computer simulation. Natalia Rybczynski and colleagues have updated this work with a much more sophisticated Three-dimensional space, three-dimensional animation model, scanning a skull of ''E. regalis'' with lasers. They were able to replicate the proposed motion with their model, although they found that additional secondary movements between other bones were required, with maximum separations of between some bones during the chewing cycle. Rybczynski and colleagues were not convinced that the Weishampel model is viable, but noted that they have several improvements to implement to their animation. Planned improvements include incorporating soft tissue and tooth wear marks and scratches, which should better constrain movements. They note that there are several other hypotheses to test as well. Further research published in 2012 by Robin Cuthbertson and colleagues found the motions required for Weishampel's model to be unlikely, and favored a model in which movements of the lower jaw produced grinding action. The lower jaw's joint with the upper jaw would permit anterior–posterior motion along with the usual rotation, and the anterior joint of the two halves of the lower jaw would also permit motion; in combination, the two halves of the lower jaw could move slightly back and forth as well as rotating slightly along their long axes. These motions would account for the observed tooth wear and a more solidly constructed skull than modeled by Weishampel.

In a 2011 study, Campione and Evans recorded data from all known "edmontosaur" skulls from the Campanian and Maastrichtian and used it to plot a ''morphometric'' graph, comparing variable features of the skull with skull size. Their results showed that within both recognized ''Edmontosaurus'' species, many features previously used to classify additional species or genera were directly correlated with skull size. Campione and Evans interpreted these results as strongly suggesting that the shape of ''Edmontosaurus'' skulls changed dramatically as they grew. This has led to several apparent mistakes in classification in the past. The Campanian species ''Thespesius edmontoni'', previously considered a synonym of ''E. annectens'' due to its small size and skull shape, is more likely a subadult specimen of the contemporary ''E. regalis''. Similarly, the three previously recognized Maastrichtian edmontosaur species likely represent growth stages of a single species, with ''E. saskatchewanensis'' representing juveniles, ''E. annectens'' subadults, and ''Anatotitan copei'' fully mature adults. The skulls became longer and flatter as the animals grew.

In a 2014 study, researchers proposed that ''E. regalis'' reached maturity in 10-15 years of age. In a 2022 study, Wosik and Evans proposed that ''E. annectens'' reached maturity in 9 years of age based on their analysis for various specimens from different loaclities. They found the result to be similar to that of other hadrosaurs.

In a 2011 study, Campione and Evans recorded data from all known "edmontosaur" skulls from the Campanian and Maastrichtian and used it to plot a ''morphometric'' graph, comparing variable features of the skull with skull size. Their results showed that within both recognized ''Edmontosaurus'' species, many features previously used to classify additional species or genera were directly correlated with skull size. Campione and Evans interpreted these results as strongly suggesting that the shape of ''Edmontosaurus'' skulls changed dramatically as they grew. This has led to several apparent mistakes in classification in the past. The Campanian species ''Thespesius edmontoni'', previously considered a synonym of ''E. annectens'' due to its small size and skull shape, is more likely a subadult specimen of the contemporary ''E. regalis''. Similarly, the three previously recognized Maastrichtian edmontosaur species likely represent growth stages of a single species, with ''E. saskatchewanensis'' representing juveniles, ''E. annectens'' subadults, and ''Anatotitan copei'' fully mature adults. The skulls became longer and flatter as the animals grew.

In a 2014 study, researchers proposed that ''E. regalis'' reached maturity in 10-15 years of age. In a 2022 study, Wosik and Evans proposed that ''E. annectens'' reached maturity in 9 years of age based on their analysis for various specimens from different loaclities. They found the result to be similar to that of other hadrosaurs.

The brain of ''Edmontosaurus'' has been described in several papers and abstracts through the use of endocasts of the cavity where the brain had been. ''E. annectens'' and ''E. regalis'', as well as specimens not identified to species,Lull, Richard Swann; and Wright, Nelda E. (1942). ''Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America''. pp. 122–128. have been studied in this way. The brain was not particularly large for an animal the size of ''Edmontosaurus''. The space holding it was only about a quarter of the length of the skull, and various endocasts have been measured as displacing to , which does not take into account that the brain may have occupied as little as 50% of the space of the endocast, the rest of the space being taken up by the dura mater surrounding the brain. For example, the brain of the specimen with the 374 millilitre endocast is estimated to have had a volume of . The brain was an elongate structure, and as with other non-mammals, there would have been no neocortex. Like ''Stegosaurus'', the neural canal was expanded in the hips, but not to the same degree: the endosacral space of ''Stegosaurus'' had 20 times the volume of its endocranial cast, whereas the endosacral space of ''Edmontosaurus'' was only 2.59 times larger in volume.

The brain of ''Edmontosaurus'' has been described in several papers and abstracts through the use of endocasts of the cavity where the brain had been. ''E. annectens'' and ''E. regalis'', as well as specimens not identified to species,Lull, Richard Swann; and Wright, Nelda E. (1942). ''Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America''. pp. 122–128. have been studied in this way. The brain was not particularly large for an animal the size of ''Edmontosaurus''. The space holding it was only about a quarter of the length of the skull, and various endocasts have been measured as displacing to , which does not take into account that the brain may have occupied as little as 50% of the space of the endocast, the rest of the space being taken up by the dura mater surrounding the brain. For example, the brain of the specimen with the 374 millilitre endocast is estimated to have had a volume of . The brain was an elongate structure, and as with other non-mammals, there would have been no neocortex. Like ''Stegosaurus'', the neural canal was expanded in the hips, but not to the same degree: the endosacral space of ''Stegosaurus'' had 20 times the volume of its endocranial cast, whereas the endosacral space of ''Edmontosaurus'' was only 2.59 times larger in volume.

In 2003, evidence of tumors, including hemangiomas, desmoplastic fibroma, metastatic cancer, and osteoblastoma, was described in ''Edmontosaurus'' bones. Rothschild ''et al.'' tested dinosaur vertebrae for tumors using computerized tomography and fluoroscope screening. Several other hadrosaurids, including ''Brachylophosaurus'', ''Gilmoreosaurus'', and ''Bactrosaurus'', also tested positive. Although more than 10,000 fossils were examined in this manner, the tumors were limited to ''Edmontosaurus'' and closely related genera. The tumors may have been caused by environmental factors or genetics, genetic propensity.

Osteochondrosis, or surficial pits in bone at places where bones articulate, is also known in ''Edmontosaurus''. This condition, resulting from cartilage failing to be replaced by bone during growth, was found to be present in 2.2% of 224 edmontosaur toe bones. The underlying cause of the condition is unknown. Genetic predisposition, trauma, feeding intensity, alterations in blood supply, excess thyroid hormones, and deficiencies in various growth factors have been suggested. Among dinosaurs, osteochondrosis (like tumors) is most commonly found in hadrosaurids.

In 2003, evidence of tumors, including hemangiomas, desmoplastic fibroma, metastatic cancer, and osteoblastoma, was described in ''Edmontosaurus'' bones. Rothschild ''et al.'' tested dinosaur vertebrae for tumors using computerized tomography and fluoroscope screening. Several other hadrosaurids, including ''Brachylophosaurus'', ''Gilmoreosaurus'', and ''Bactrosaurus'', also tested positive. Although more than 10,000 fossils were examined in this manner, the tumors were limited to ''Edmontosaurus'' and closely related genera. The tumors may have been caused by environmental factors or genetics, genetic propensity.

Osteochondrosis, or surficial pits in bone at places where bones articulate, is also known in ''Edmontosaurus''. This condition, resulting from cartilage failing to be replaced by bone during growth, was found to be present in 2.2% of 224 edmontosaur toe bones. The underlying cause of the condition is unknown. Genetic predisposition, trauma, feeding intensity, alterations in blood supply, excess thyroid hormones, and deficiencies in various growth factors have been suggested. Among dinosaurs, osteochondrosis (like tumors) is most commonly found in hadrosaurids.

Like other hadrosaurids, ''Edmontosaurus'' is thought to have been a facultative biped, meaning that it mostly moved on four legs, but could adopt a bipedal stance when needed. It probably went on all fours when standing still or moving slowly, and switched to using the hind legs alone when moving more rapidly. Research conducted by computer modeling in 2007 suggests that ''Edmontosaurus'' could run at high speeds, perhaps up to . Further simulations using a subadult specimen estimated as weighing when alive produced a model that could run or hop bipedally, use a trot (horse gait), trot, Horse gait#Pace, pace, or single foot symmetric quadrupedal gait, or move at a Horse gait#Gallop, gallop. The researchers found to their surprise that the fastest gait was kangaroo-like hopping (maximum simulated speed of ), which they regarded as unlikely based on the size of the animal and lack of hopping footprints in the fossil record, and instead interpreted the result as indicative of an inaccuracy in their simulation. The fastest non-hopping gaits were galloping (maximum simulated speed of ) and running bipedally (maximum simulated speed of ). They found weak support for bipedal running as the most likely option for high-speed movement, but did not rule out high-speed quadrupedal movement.

While long thought to have been aquatic or semiaquatic, hadrosaurids were not as well-suited for swimming as other dinosaurs (particularly theropods, who were once thought to have been unable to pursue hadrosaurids into water). Hadrosaurids had slim hands with short fingers, making their forelimbs ineffective for propulsion, and the tail was also not useful for propulsion because of the ossified tendons that increased its rigidity, and the poorly developed attachment points for muscles that would have moved the tail from side to side.

Like other hadrosaurids, ''Edmontosaurus'' is thought to have been a facultative biped, meaning that it mostly moved on four legs, but could adopt a bipedal stance when needed. It probably went on all fours when standing still or moving slowly, and switched to using the hind legs alone when moving more rapidly. Research conducted by computer modeling in 2007 suggests that ''Edmontosaurus'' could run at high speeds, perhaps up to . Further simulations using a subadult specimen estimated as weighing when alive produced a model that could run or hop bipedally, use a trot (horse gait), trot, Horse gait#Pace, pace, or single foot symmetric quadrupedal gait, or move at a Horse gait#Gallop, gallop. The researchers found to their surprise that the fastest gait was kangaroo-like hopping (maximum simulated speed of ), which they regarded as unlikely based on the size of the animal and lack of hopping footprints in the fossil record, and instead interpreted the result as indicative of an inaccuracy in their simulation. The fastest non-hopping gaits were galloping (maximum simulated speed of ) and running bipedally (maximum simulated speed of ). They found weak support for bipedal running as the most likely option for high-speed movement, but did not rule out high-speed quadrupedal movement.

While long thought to have been aquatic or semiaquatic, hadrosaurids were not as well-suited for swimming as other dinosaurs (particularly theropods, who were once thought to have been unable to pursue hadrosaurids into water). Hadrosaurids had slim hands with short fingers, making their forelimbs ineffective for propulsion, and the tail was also not useful for propulsion because of the ossified tendons that increased its rigidity, and the poorly developed attachment points for muscles that would have moved the tail from side to side.

''Edmontosaurus'' was a wide-ranging genus in both time and space. At the southern range of its distribution, the rock units from which it is known can be divided into two groups by age: the older Horseshoe Canyon and St. Mary River formations, and the younger Frenchman, Hell Creek, and Lance formations. The time span covered by the Horseshoe Canyon Formation and equivalents is also known as Edmontonian, and the time span covered by the younger units is also known as Lancian. The Edmontonian and Lancian time intervals had distinct dinosaur faunas. At its northern range, ''Edmontosaurus'' is known from a single locality; the Liscomb Bonebed of the Prince Creek Formation.

The Edmontonian land vertebrate age is defined by the first appearance of ''Edmontosaurus regalis'' in the fossil record. Although sometimes reported as of exclusively early Maastrichtian age, the Horseshoe Canyon Formation was of somewhat longer duration. Deposition began approximately 73 million years ago, in the late Campanian, and ended between 68.0 and 67.6 million years ago. ''Edmontosaurus regalis'' is known from the lowest of five units within the Horseshoe Canyon Formation, but is absent from at least the second to the top. As many as three quarters of the dinosaur specimens from badlands near Drumheller, Alberta may pertain to ''Edmontosaurus''.

''Edmontosaurus'' was a wide-ranging genus in both time and space. At the southern range of its distribution, the rock units from which it is known can be divided into two groups by age: the older Horseshoe Canyon and St. Mary River formations, and the younger Frenchman, Hell Creek, and Lance formations. The time span covered by the Horseshoe Canyon Formation and equivalents is also known as Edmontonian, and the time span covered by the younger units is also known as Lancian. The Edmontonian and Lancian time intervals had distinct dinosaur faunas. At its northern range, ''Edmontosaurus'' is known from a single locality; the Liscomb Bonebed of the Prince Creek Formation.

The Edmontonian land vertebrate age is defined by the first appearance of ''Edmontosaurus regalis'' in the fossil record. Although sometimes reported as of exclusively early Maastrichtian age, the Horseshoe Canyon Formation was of somewhat longer duration. Deposition began approximately 73 million years ago, in the late Campanian, and ended between 68.0 and 67.6 million years ago. ''Edmontosaurus regalis'' is known from the lowest of five units within the Horseshoe Canyon Formation, but is absent from at least the second to the top. As many as three quarters of the dinosaur specimens from badlands near Drumheller, Alberta may pertain to ''Edmontosaurus''.