Castra Vetoniana - Dolchenium.png on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In the

A ''castrum'' was designed to house and protect the soldiers, their equipment and supplies when they were not fighting or marching.

The most detailed description that survives about Roman military camps is ''

A ''castrum'' was designed to house and protect the soldiers, their equipment and supplies when they were not fighting or marching.

The most detailed description that survives about Roman military camps is ''

The ideal enforced a linear plan for a camp or fort: a square for camps to contain one legion or smaller unit, a rectangle for two legions, each legion being placed back-to-back with headquarters next to each other. Laying it out was a geometric exercise conducted by experienced officers called ''metatores'', who used graduated measuring rods called ''decempedae'' ("10-footers") and ''gromatici'' who used a groma, a sighting device consisting of a vertical staff with horizontal cross pieces and vertical plumb-lines. Ideally the process started in the centre of the planned camp at the site of the headquarters tent or building (principia). Streets and other features were marked with coloured pennants or rods.

The street plans of various present-day cities still retain traces of a Roman camp, for example Marsala in Sicily, the ancient Lilybaeum, where the name of the main street, the Cassaro, perpetuates the name "castrum".

The ideal enforced a linear plan for a camp or fort: a square for camps to contain one legion or smaller unit, a rectangle for two legions, each legion being placed back-to-back with headquarters next to each other. Laying it out was a geometric exercise conducted by experienced officers called ''metatores'', who used graduated measuring rods called ''decempedae'' ("10-footers") and ''gromatici'' who used a groma, a sighting device consisting of a vertical staff with horizontal cross pieces and vertical plumb-lines. Ideally the process started in the centre of the planned camp at the site of the headquarters tent or building (principia). Streets and other features were marked with coloured pennants or rods.

The street plans of various present-day cities still retain traces of a Roman camp, for example Marsala in Sicily, the ancient Lilybaeum, where the name of the main street, the Cassaro, perpetuates the name "castrum".

The Castrum's special structure also defended from attacks.

The base (''munimentum'', "fortification") was placed entirely within the ''

The Castrum's special structure also defended from attacks.

The base (''munimentum'', "fortification") was placed entirely within the ''

Every camp included "main street", which ran through the camp in a north–south direction and was very wide. The names of streets in many cities formerly occupied by the Romans suggest that the street was called ''

Every camp included "main street", which ran through the camp in a north–south direction and was very wide. The names of streets in many cities formerly occupied by the Romans suggest that the street was called '' Across the central plaza (''principia'') to the east or west was the main gate, the ''Porta Praetoria''. Marching through it and down "headquarters street" a unit ended up in formation in front of the headquarters. The standards of the legion were located on display there, very much like the flag of modern camps.

On the other side of the praetorium the ''Via Praetoria'' continued to the wall, where it went through the ''Porta Decumana''. In theory this was the back gate. Supplies were supposed to come in through it and so it was also called, descriptively, the ''Porta Quaestoria''. The term Decumana, "of the 10th", came from the arranging of ''manipuli'' or ''turmae'' from the first to the 10th, such that the 10th was near the ''intervallum'' on that side. The ''Via Praetoria'' on that side might take the name ''Via Decumana'' or the entire ''Via Praetoria'' be replaced with ''Decumanus Maximus''.

Across the central plaza (''principia'') to the east or west was the main gate, the ''Porta Praetoria''. Marching through it and down "headquarters street" a unit ended up in formation in front of the headquarters. The standards of the legion were located on display there, very much like the flag of modern camps.

On the other side of the praetorium the ''Via Praetoria'' continued to the wall, where it went through the ''Porta Decumana''. In theory this was the back gate. Supplies were supposed to come in through it and so it was also called, descriptively, the ''Porta Quaestoria''. The term Decumana, "of the 10th", came from the arranging of ''manipuli'' or ''turmae'' from the first to the 10th, such that the 10th was near the ''intervallum'' on that side. The ''Via Praetoria'' on that side might take the name ''Via Decumana'' or the entire ''Via Praetoria'' be replaced with ''Decumanus Maximus''.

The ''Via Quintana'' and the ''Via Principalis'' divided the camp into three districts: the ''Latera Praetorii'', the ''Praetentura'' and the ''Retentura''. In the ''latera'' ("sides") were the ''Arae'' (sacrificial altars), the ''Auguratorium'' (for auspices), the ''Tribunal'', where courts martial and arbitrations were conducted (it had a raised platform), the guardhouse, the quarters of various kinds of staff and the storehouses for grain (''horrea'') or meat (''carnarea''). Sometimes the ''horrea'' were located near the barracks and the meat was stored on the hoof. Analysis of sewage from latrines indicates the legionary diet was mainly grain. Also located in the ''Latera'' was the ''Armamentarium'', a long shed containing any heavy weapons and artillery not on the wall.

The ''Via Quintana'' and the ''Via Principalis'' divided the camp into three districts: the ''Latera Praetorii'', the ''Praetentura'' and the ''Retentura''. In the ''latera'' ("sides") were the ''Arae'' (sacrificial altars), the ''Auguratorium'' (for auspices), the ''Tribunal'', where courts martial and arbitrations were conducted (it had a raised platform), the guardhouse, the quarters of various kinds of staff and the storehouses for grain (''horrea'') or meat (''carnarea''). Sometimes the ''horrea'' were located near the barracks and the meat was stored on the hoof. Analysis of sewage from latrines indicates the legionary diet was mainly grain. Also located in the ''Latera'' was the ''Armamentarium'', a long shed containing any heavy weapons and artillery not on the wall.

The ''Praetentura'' ("stretching to the front") contained the ''Scamnum Legatorum'', the quarters of officers who were below general but higher than company commanders (''Legati''). Near the ''Principia'' were the ''Valetudinarium'' (hospital), ''Veterinarium'' (for horses), ''Fabrica'' ("workshop", metals and wood), and further to the front the quarters of special forces. These included ''Roman navy, Classici'' ("marines", as most European camps were on rivers and contained a river naval command), ''Equites'' ("cavalry"), ''Speculatores, Exploratores'' ("scouts"), and ''Vexillarii'' (carriers of vexillae, the official pennants of the legion and its units). Troops who did not fit elsewhere also were there.

The part of the ''Retentura'' ("stretching to the rear") closest to the ''Principia'' contained the ''Quaestorium''. By the late empire it had developed also into a safekeep for plunder and a prison for hostages and high-ranking enemy captives. Near the ''Quaestorium'' were the quarters of the headquarters guard (''Statores''), who amounted to two Centuria, centuries (companies). If the ''Imperator'' was present they served as his bodyguard.

The ''Praetentura'' ("stretching to the front") contained the ''Scamnum Legatorum'', the quarters of officers who were below general but higher than company commanders (''Legati''). Near the ''Principia'' were the ''Valetudinarium'' (hospital), ''Veterinarium'' (for horses), ''Fabrica'' ("workshop", metals and wood), and further to the front the quarters of special forces. These included ''Roman navy, Classici'' ("marines", as most European camps were on rivers and contained a river naval command), ''Equites'' ("cavalry"), ''Speculatores, Exploratores'' ("scouts"), and ''Vexillarii'' (carriers of vexillae, the official pennants of the legion and its units). Troops who did not fit elsewhere also were there.

The part of the ''Retentura'' ("stretching to the rear") closest to the ''Principia'' contained the ''Quaestorium''. By the late empire it had developed also into a safekeep for plunder and a prison for hostages and high-ranking enemy captives. Near the ''Quaestorium'' were the quarters of the headquarters guard (''Statores''), who amounted to two Centuria, centuries (companies). If the ''Imperator'' was present they served as his bodyguard.

Further from the ''Quaestorium'' were the tents of the ''Nationes'' ("natives"), who were auxiliaries of foreign troops, and the legionaries themselves in double rows of tents or barracks (''Strigae''). One ''Striga'' was as long as required and 18 m wide. In it were two ''Hemistrigia'' of facing tents centered in its 9 m strip. Arms could be stacked before the tents and baggage carts kept there as well. Space on the other side of the tent was for passage.

In the northern places like Britain, where it got cold in the winter, they would make wood or stone barracks. The Romans would also put a fireplace in the barracks. They had about three bunk beds in it. They had a small room beside it where they put their armour; it was as big as the tents. They would also make these barracks if the fort they had was going to stay there for good.

A tent was 3 by 3.5 metres (0.6 m for the aisle), ten men per tent. Ideally a company took 10 tents, arranged in a line of 10 companies, with the 10th near the ''Porta Decumana''. Of the c. 9.2 square metres of bunk space each man received 0.9, or about 0.6 by 1.5 m, which was only practical if they slept with heads to the aisle. The single tent with its men was called ''Contubernium (Roman army unit), contubernium'', also used for "squad". A squad during some periods was 8 men or fewer.

The ''Centurion'', or company commander, had a double-sized tent for his quarters, which served also as official company area. Other than there, the men had to find other places to be. To avoid mutiny, it became extremely important for the officers to keep them busy.

A covered portico might protect the walkway along the tents. If barracks had been constructed, one company was housed in one barracks building, with the arms at one end and the common area at the other. The company area was used for cooking and recreation, such as gaming. The army provisioned the men and had their bread (''panis militaris'') baked in outdoor ovens, but the men were responsible for cooking and serving themselves. They could buy meals or supplementary foods at the canteen. The officers were allowed servants.

Further from the ''Quaestorium'' were the tents of the ''Nationes'' ("natives"), who were auxiliaries of foreign troops, and the legionaries themselves in double rows of tents or barracks (''Strigae''). One ''Striga'' was as long as required and 18 m wide. In it were two ''Hemistrigia'' of facing tents centered in its 9 m strip. Arms could be stacked before the tents and baggage carts kept there as well. Space on the other side of the tent was for passage.

In the northern places like Britain, where it got cold in the winter, they would make wood or stone barracks. The Romans would also put a fireplace in the barracks. They had about three bunk beds in it. They had a small room beside it where they put their armour; it was as big as the tents. They would also make these barracks if the fort they had was going to stay there for good.

A tent was 3 by 3.5 metres (0.6 m for the aisle), ten men per tent. Ideally a company took 10 tents, arranged in a line of 10 companies, with the 10th near the ''Porta Decumana''. Of the c. 9.2 square metres of bunk space each man received 0.9, or about 0.6 by 1.5 m, which was only practical if they slept with heads to the aisle. The single tent with its men was called ''Contubernium (Roman army unit), contubernium'', also used for "squad". A squad during some periods was 8 men or fewer.

The ''Centurion'', or company commander, had a double-sized tent for his quarters, which served also as official company area. Other than there, the men had to find other places to be. To avoid mutiny, it became extremely important for the officers to keep them busy.

A covered portico might protect the walkway along the tents. If barracks had been constructed, one company was housed in one barracks building, with the arms at one end and the common area at the other. The company area was used for cooking and recreation, such as gaming. The army provisioned the men and had their bread (''panis militaris'') baked in outdoor ovens, but the men were responsible for cooking and serving themselves. They could buy meals or supplementary foods at the canteen. The officers were allowed servants.

The influence of a base extended far beyond its walls. The total land required for the maintenance of a permanent base was called its ''territoria''. In it were located all the resources of nature and the terrain required by the base: pastures, woodlots, water sources, stone quarries, mines, exercise fields and attached villages. The central castra might also support various fortified adjuncts to the main base, which were not in themselves self-sustaining (as was the base). In this category were ''speculae'', "watchtowers", ''castella'', "small camps", and naval bases.

All the major bases near rivers featured some sort of fortified naval installation, one side of which was formed by the river or lake. The other sides were formed by a polygonal wall and ditch constructed in the usual way, with gates and watchtowers. The main internal features were the boat sheds and the docks. When not in use, the boats were drawn up into the sheds for maintenance and protection. Since the camp was placed to best advantage on a hill or slope near the river, the naval base was usually outside its walls. The ''classici'' and the ''optiones'' of the naval installation relied on the camp for its permanent defense. Naval personnel generally enjoyed better quarters and facilities. Many were civilians working for the military.

The influence of a base extended far beyond its walls. The total land required for the maintenance of a permanent base was called its ''territoria''. In it were located all the resources of nature and the terrain required by the base: pastures, woodlots, water sources, stone quarries, mines, exercise fields and attached villages. The central castra might also support various fortified adjuncts to the main base, which were not in themselves self-sustaining (as was the base). In this category were ''speculae'', "watchtowers", ''castella'', "small camps", and naval bases.

All the major bases near rivers featured some sort of fortified naval installation, one side of which was formed by the river or lake. The other sides were formed by a polygonal wall and ditch constructed in the usual way, with gates and watchtowers. The main internal features were the boat sheds and the docks. When not in use, the boats were drawn up into the sheds for maintenance and protection. Since the camp was placed to best advantage on a hill or slope near the river, the naval base was usually outside its walls. The ''classici'' and the ''optiones'' of the naval installation relied on the camp for its permanent defense. Naval personnel generally enjoyed better quarters and facilities. Many were civilians working for the military.

Ordinary camp life began with a ''buccina'' call at daybreak, the first watch of the day. The soldiers arose at this time and shortly after collected in the company area for breakfast and assembly. The centurions were up before them and off to the ''principia'' where they and the ''equites'' were required to assemble. The regimental commanders, the tribunes, were already converging on the ''praetorium''. There the general staff was busily at work planning the day. At a staff meeting the ''Tribunes'' received the password and the orders of the day. They brought those back to the ''centuriones'', who returned to their company areas to instruct the men.

For soldiers, the main item of the agenda was a vigorous training session lasting about a watch long. Recruits received two, one in the morning and one in the afternoon.Vegetius Book I, linked in Primary sources below. Planning and supervision of training were under a general staff officer, who might manage training at several camps. According to Vegetius, the men might take a hike or a jog under full pack, or swim a river. Marching drill was always in order.

Each soldier was taught the use of every weapon and also was taught to ride. Seamanship was taught at naval bases. Soldiers were generalists in the military and construction arts. They practiced archery, spear-throwing and above all swordsmanship against posts (''pali'') fixed in the ground. Training was taken very seriously and was democratic. Ordinary soldiers would see all the officers training with them including the ''praetor'', or the Emperor, if he was in camp.

Swordsmanship lessons and use of the shooting range probably took place on the ''campus'', a "field" outside the ''castra'', from which English camp derives. Its surface could be lightly paved. Winter curtailed outdoor training. The general might in that case have sheds constructed, which served as field houses for training. There is archaeological evidence in one case of an indoor equestrian ring.

Apart from the training, each soldier had a regular job on the base, of which there were a large variety from the various kinds of clerks to the craftsmen. Soldiers changed jobs frequently. The commander's policy was to have all the soldiers skilled in all the arts and crafts so that they could be as interchangeable as possible. Even then the goal was not entirely achievable. The gap was bridged by the specialists, the ''optiones'' or "chosen men", of which there were many different kinds. For example, a skilled artisan might be chosen to superintend a workshop. Soldiers were also expected to build the camp upon arrival before engaging in any sort of warfare after a day's march.

Ordinary camp life began with a ''buccina'' call at daybreak, the first watch of the day. The soldiers arose at this time and shortly after collected in the company area for breakfast and assembly. The centurions were up before them and off to the ''principia'' where they and the ''equites'' were required to assemble. The regimental commanders, the tribunes, were already converging on the ''praetorium''. There the general staff was busily at work planning the day. At a staff meeting the ''Tribunes'' received the password and the orders of the day. They brought those back to the ''centuriones'', who returned to their company areas to instruct the men.

For soldiers, the main item of the agenda was a vigorous training session lasting about a watch long. Recruits received two, one in the morning and one in the afternoon.Vegetius Book I, linked in Primary sources below. Planning and supervision of training were under a general staff officer, who might manage training at several camps. According to Vegetius, the men might take a hike or a jog under full pack, or swim a river. Marching drill was always in order.

Each soldier was taught the use of every weapon and also was taught to ride. Seamanship was taught at naval bases. Soldiers were generalists in the military and construction arts. They practiced archery, spear-throwing and above all swordsmanship against posts (''pali'') fixed in the ground. Training was taken very seriously and was democratic. Ordinary soldiers would see all the officers training with them including the ''praetor'', or the Emperor, if he was in camp.

Swordsmanship lessons and use of the shooting range probably took place on the ''campus'', a "field" outside the ''castra'', from which English camp derives. Its surface could be lightly paved. Winter curtailed outdoor training. The general might in that case have sheds constructed, which served as field houses for training. There is archaeological evidence in one case of an indoor equestrian ring.

Apart from the training, each soldier had a regular job on the base, of which there were a large variety from the various kinds of clerks to the craftsmen. Soldiers changed jobs frequently. The commander's policy was to have all the soldiers skilled in all the arts and crafts so that they could be as interchangeable as possible. Even then the goal was not entirely achievable. The gap was bridged by the specialists, the ''optiones'' or "chosen men", of which there were many different kinds. For example, a skilled artisan might be chosen to superintend a workshop. Soldiers were also expected to build the camp upon arrival before engaging in any sort of warfare after a day's march.

The supply administration was run as a business using money as the medium of exchange. The aureus was the preferred coin of the late republic and early empire; in the late empire the Solidus (coin), solidus came into use. The larger bases, such as ''Moguntiacum'', minted their own coins. As does any business, the base quaestorium required careful record keeping, performed mainly by the optiones. A chance cache of tablets from Vindolanda in Britain gives us a glimpse of some supply transactions. They record, among other things, the purchase of consumables and raw supplies, the storage and repair of clothing and other items, and the sale of items, including foodstuffs, to achieve an income. Vindolanda traded vigorously with the surrounding natives.

Another feature of the camp was the military hospital (''valetudinarium'', later ''hospitium''). Augustus instituted the first permanent medical corps in the Roman army. Its physicians, the ''medici ordinarii'', had to be qualified physicians. They were allowed medical students, practitioners and whatever orderlies they needed; i.e., the military hospitals were medical schools and places of residency as well.

Officers were allowed to marry and to reside with their families on base. The army did not extend the same privileges to the men, who were not allowed to marry. However, they often kept common law families off base in communities nearby. The communities might be native, as the tribesmen tended to build around a permanent base for purposes of trade, but also the base sponsored villages (''vici'') of dependents and businessmen. Dependants were not allowed to follow an army on the march into hostile territory.

Military service was for about 25 years. At the end of that time, the veteran was given a certificate of honorable discharge (''honesta missio''). Some of these have survived engraved on stone. Typically they certify that the veteran, his wife (one per veteran) and children or his sweetheart were now Roman citizens, which is a good indication that troops, which were used chiefly on the frontier, were from peoples elsewhere on the frontier who wished to earn Roman citizenship. However, under Antoninus Pius, citizenship was no longer granted to the children of rank-and-file veterans, the privilege becoming restricted only to officers.

Veterans often went into business in the communities near a base. They became permanent members of the community and would stay on after the troops were withdrawn, as in the notable case of Saint Patrick's family.

The supply administration was run as a business using money as the medium of exchange. The aureus was the preferred coin of the late republic and early empire; in the late empire the Solidus (coin), solidus came into use. The larger bases, such as ''Moguntiacum'', minted their own coins. As does any business, the base quaestorium required careful record keeping, performed mainly by the optiones. A chance cache of tablets from Vindolanda in Britain gives us a glimpse of some supply transactions. They record, among other things, the purchase of consumables and raw supplies, the storage and repair of clothing and other items, and the sale of items, including foodstuffs, to achieve an income. Vindolanda traded vigorously with the surrounding natives.

Another feature of the camp was the military hospital (''valetudinarium'', later ''hospitium''). Augustus instituted the first permanent medical corps in the Roman army. Its physicians, the ''medici ordinarii'', had to be qualified physicians. They were allowed medical students, practitioners and whatever orderlies they needed; i.e., the military hospitals were medical schools and places of residency as well.

Officers were allowed to marry and to reside with their families on base. The army did not extend the same privileges to the men, who were not allowed to marry. However, they often kept common law families off base in communities nearby. The communities might be native, as the tribesmen tended to build around a permanent base for purposes of trade, but also the base sponsored villages (''vici'') of dependents and businessmen. Dependants were not allowed to follow an army on the march into hostile territory.

Military service was for about 25 years. At the end of that time, the veteran was given a certificate of honorable discharge (''honesta missio''). Some of these have survived engraved on stone. Typically they certify that the veteran, his wife (one per veteran) and children or his sweetheart were now Roman citizens, which is a good indication that troops, which were used chiefly on the frontier, were from peoples elsewhere on the frontier who wished to earn Roman citizenship. However, under Antoninus Pius, citizenship was no longer granted to the children of rank-and-file veterans, the privilege becoming restricted only to officers.

Veterans often went into business in the communities near a base. They became permanent members of the community and would stay on after the troops were withdrawn, as in the notable case of Saint Patrick's family.

Conducted in parallel with the ordinary activities was "the duty", the official chores required by the camp under strict military discipline. The ''Legate'' was ultimately responsible for them as he was for the entire camp, but he delegated the duty to a tribune chosen as officer of the day. The line ''Tribunes'' were commanders of ''cohort (military unit), Cohortes'' and were approximately the equivalent of colonels. The 6 tribunes were divided into units of two, with each unit being responsible for filling the position of officer of the day for two months. The two men of a unit decided among themselves who would take what day. They could alternate days or each take a month. One filled in for the other in case of illness. On his day, the tribune effectively commanded the camp and was even respected as such by the ''Legate''.

The equivalent concept of the duties performed in modern camps is roughly the detail. The responsibilities (''curae'') of the many kinds of detail were distributed to the men by all the methods considered fair and democratic: lot, rotation and negotiation. Certain kinds of ''cura'' were assigned certain classes or types of troops; for example, wall sentries were chosen only from ''Velites''. Soldiers could be temporarily or permanently exempted: the ''immunes''. For example, a Triarii, Triarius was ''immunis'' from the ''curae'' of the Hastati.

The duty year was divided into time slices, typically one or two months, which were apportioned to units, typically maniple (military unit), maniples or centuria, centuries. They were always allowed to negotiate who took the duty and when. The most common kind of ''cura'' were the posts of the sentinels, called the ''excubiae'' by day and the ''vigilae'' at night. Wall posts were ''praesidia'', gate posts, ''custodiae'', advance positions before the gates, ''stationes''.

In addition were special guards and details. One post was typically filled by four men, one sentinel and the others at ease until a situation arose or it was their turn to be sentinel. Some of the details were:

*guarding, cleaning and maintaining the ''principia''.

*guarding and maintaining the quarters of each

Conducted in parallel with the ordinary activities was "the duty", the official chores required by the camp under strict military discipline. The ''Legate'' was ultimately responsible for them as he was for the entire camp, but he delegated the duty to a tribune chosen as officer of the day. The line ''Tribunes'' were commanders of ''cohort (military unit), Cohortes'' and were approximately the equivalent of colonels. The 6 tribunes were divided into units of two, with each unit being responsible for filling the position of officer of the day for two months. The two men of a unit decided among themselves who would take what day. They could alternate days or each take a month. One filled in for the other in case of illness. On his day, the tribune effectively commanded the camp and was even respected as such by the ''Legate''.

The equivalent concept of the duties performed in modern camps is roughly the detail. The responsibilities (''curae'') of the many kinds of detail were distributed to the men by all the methods considered fair and democratic: lot, rotation and negotiation. Certain kinds of ''cura'' were assigned certain classes or types of troops; for example, wall sentries were chosen only from ''Velites''. Soldiers could be temporarily or permanently exempted: the ''immunes''. For example, a Triarii, Triarius was ''immunis'' from the ''curae'' of the Hastati.

The duty year was divided into time slices, typically one or two months, which were apportioned to units, typically maniple (military unit), maniples or centuria, centuries. They were always allowed to negotiate who took the duty and when. The most common kind of ''cura'' were the posts of the sentinels, called the ''excubiae'' by day and the ''vigilae'' at night. Wall posts were ''praesidia'', gate posts, ''custodiae'', advance positions before the gates, ''stationes''.

In addition were special guards and details. One post was typically filled by four men, one sentinel and the others at ease until a situation arose or it was their turn to be sentinel. Some of the details were:

*guarding, cleaning and maintaining the ''principia''.

*guarding and maintaining the quarters of each

The Romans in Britain, Glossary of Military terms

Note that both Latin and Greek terms with the same meaning are included.

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

and the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

, the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

word ''castrum'', plural ''castra'', was a military-related term.

In Latin usage, the singular form ''castrum'' meant 'fort', while the plural form ''castra'' meant 'camp'. The singular and plural forms could refer in Latin to either a building or plot of land, used as a fortified military base

A military base is a facility directly owned and operated by or for the military or one of its branches that shelters military equipment and personnel, and facilitates training and operations. A military base always provides accommodations for ...

.. Included is a discussion about the typologies of Roman fortifications.

In English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

usage, ''castrum'' commonly translates to "Roman fort", "Roman camp" and "Roman fortress". However, scholastic convention tends to translate ''castrum'' as "fort", "camp", "marching camp" or "fortress".

Romans used the term ''castrum'' for different sizes of camps – including large legionary fortresses, smaller forts for cohorts or for auxiliary forces, temporary encampments, and "marching" forts. The diminutive form '' castellum'' was used for fortlets, typically occupied by a detachment of a cohort or a '' centuria''.

For a list of known castra, see List of castra

Castra (Latin, singular castrum) were military forts of various sizes used by the Roman army throughout the Empire in various places of Europe, Asia and Africa.

The largest castra were permanent legionary fortresses.

Locations

The disposition ...

.

Etymology

''Castrum'' appears inOscan

Oscan is an extinct Indo-European language of southern Italy. The language is in the Osco-Umbrian or Sabellic branch of the Italic languages. Oscan is therefore a close relative of Umbrian.

Oscan was spoken by a number of tribes, including ...

and Umbrian

Umbrian is an extinct Italic language formerly spoken by the Umbri in the ancient Italian region of Umbria. Within the Italic languages it is closely related to the Oscan group and is therefore associated with it in the group of Osco-Umbrian ...

, two other Italic languages, suggesting an origin at least as old as Proto-Italic language

The Proto-Italic language is the ancestor of the Italic languages, most notably Latin and its descendants, the Romance languages. It is not directly attested in writing, but has been reconstructed to some degree through the comparative method. P ...

.

Julius Pokorny traces a probable derivation from *k̂es-, ("cut") in *k̂es-tro-m, ("cutting tool").

These Italic reflexes based on *kastrom include Oscan ( genitive case) and Umbrian , ( accusative case). They have the same meaning, says Pokorny, as Latin , an estate, or tract of land. This is not any land, but is a prepared or cultivated tract, such as a farm enclosed by a fence or a wooden or stone wall of some kind. Cornelius Nepos

Cornelius Nepos (; c. 110 BC – c. 25 BC) was a Roman biographer. He was born at Hostilia, a village in Cisalpine Gaul not far from Verona.

Biography

Nepos's Cisalpine birth is attested by Ausonius, and Pliny the Elder calls him ''Pad ...

uses Latin in that sense: when Alcibiades deserts to the Persians, Pharnabazus gives him an estate () worth 500 talents in tax revenues. This is a change of meaning from the reflexes in other languages, which still mean some sort of knife, axe, or spear. Pokorny explains it as , "a lager, as a cut-off piece of land">

If this is the civilian interpretation, the military version must be "military reservation", a piece of land cut off from the common land around it and modified for military use. All castra must be defended by works, often no more than a stockade, for which the soldiers carried stakes, and a ditch. The could be prepared under attack within a hollow square or behind a battle line. Considering that the earliest military shelters were tents made of hide or cloth, and all but the most permanent bases housed the men in tents placed in quadrangles and separated by numbered streets, one may well have acquired the connotation of tent.

Linguistic development of the military castra

The commonest Latin syntagmata (here phrases) for the term are: ; : Permanent camp/fortresses ; : Summer camp/fortresses ; : Winter camp/fortresses ; / : Navy camp/fortresses In Latin the term is much more frequently used as a proper name for geographical locations: e.g., , , , , . The plural was also used as a place name, as , and from this comes the Welsh place name prefix (e.g.Caerleon

Caerleon (; cy, Caerllion) is a town and community in Newport, Wales. Situated on the River Usk, it lies northeast of Newport city centre, and southeast of Cwmbran. Caerleon is of archaeological importance, being the site of a notable Roman ...

and Caerwent

Caerwent ( cy, Caer-went) is a village and community in Monmouthshire, Wales. It is located about five miles west of Chepstow and 11 miles east of Newport. It was founded by the Romans as the market town of ''Venta Silurum'', an important sett ...

) and English suffixes '' -caster'' and ''-chester'' (e.g. Winchester and Lancaster).

, "son of the camps", was one of the names used by the emperor Caligula and then also by other emperors.

, also derived from , is a common Spanish family name as well as toponym

Toponymy, toponymics, or toponomastics is the study of '' toponyms'' (proper names of places, also known as place names and geographic names), including their origins, meanings, usage and types. Toponym is the general term for a proper name of ...

in Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

and other Hispanophone countries, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, and the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

, either by itself or in various compounds such as the World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for h ...

of (earlier ).

The terms (''army camp'') and (''fortification

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere' ...

'') were used by Greek language

Greek ( el, label= Modern Greek, Ελληνικά, Elliniká, ; grc, Ἑλληνική, Hellēnikḗ) is an independent branch of the Indo-European family of languages, native to Greece, Cyprus, southern Italy ( Calabria and Salento), southe ...

authors to translate and , respectively.

Description

A ''castrum'' was designed to house and protect the soldiers, their equipment and supplies when they were not fighting or marching.

The most detailed description that survives about Roman military camps is ''

A ''castrum'' was designed to house and protect the soldiers, their equipment and supplies when they were not fighting or marching.

The most detailed description that survives about Roman military camps is ''De Munitionibus Castrorum

''De Munitionibus Castrorum'' ("Concerning the fortifications of a military camp") is a work by an unknown author. Due to this work formerly being attributed to Hyginus Gromaticus, its author is often called "Pseudo-Hyginus". This work is the most ...

'', a manuscript of 11 pages that dates most probably from the late 1st to early 2nd century AD.

Regulations required a major unit in the field to retire to a properly constructed camp every day. "… as soon as they have marched into an enemy's land, they do not begin to fight until they have walled their camp about; nor is the fence they raise rashly made, or uneven; nor do they all abide ill it, nor do those that are in it take their places at random; but if it happens that the ground is uneven, it is first levelled: their camp is also four-square by measure, and carpenters are ready, in great numbers, with their tools, to erect their buildings for them." To this end a marching column ported the equipment needed to build and stock the camp in a baggage train of wagons and on the backs of the soldiers.

Camps were the responsibility of engineering units to which specialists of many types belonged, officered by ''architecti'', "chief engineers", who requisitioned manual labor from the soldiers at large as required. They could throw up a camp under enemy attack in as little as a few hours. Judging from the names, they probably used a repertory of camp plans, selecting the one appropriate to the length of time a legion would spend in it: ''tertia castra'', ''quarta castra'', etc. (''a camp of three days'', ''four days'', etc.).

More permanent camps were ''castra stativa'' (''standing camps''). The least permanent of these were ''castra aestiva'' or ''aestivalia'', "summer camps", in which the soldiers were housed ''sub pellibus'' or ''sub tentoriis'', "under tents". Summer was the campaign season. For the winter the soldiers retired to ''castra hiberna'' containing barracks and other buildings of more solid materials, with timber construction gradually being replaced by stone. ''Castra hibernas'' held eight soldiers to a room, who slept on bunkbeds. The soldiers in each room were also required to cook their own meals and eat with their "roommates".

The camp allowed the Romans to keep a rested and supplied army in the field. Neither the Celtic nor Germanic armies had this capability: they found it necessary to disperse after only a few days.

The largest castra were '' legionary fortresses'' built as bases for one or more whole legions.

From the time of Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

more permanent castra with wooden or stone buildings and walls were introduced as the distant and hard-won boundaries of the expanding empire required permanent garrisons to control local and external threats from warlike tribes. Previously, legions were raised for specific military campaigns and subsequently disbanded, requiring only temporary castra. From then on many castra of various sizes were established many of which became permanent settlements.

Plan of forts

Sources and origins

From the most ancient times Roman camps were constructed according to a certain ideal pattern, formally described in two main sources, the ''De Munitionibus Castrorum

''De Munitionibus Castrorum'' ("Concerning the fortifications of a military camp") is a work by an unknown author. Due to this work formerly being attributed to Hyginus Gromaticus, its author is often called "Pseudo-Hyginus". This work is the most ...

'' and the works of Polybius. P. Fl. Vegetius Renatus has a small section on entrenched camps as well. The terminology varies but the basic plan is the same. The hypothesis of an Etruscan origin is a viable alternative.

Layout

The ideal enforced a linear plan for a camp or fort: a square for camps to contain one legion or smaller unit, a rectangle for two legions, each legion being placed back-to-back with headquarters next to each other. Laying it out was a geometric exercise conducted by experienced officers called ''metatores'', who used graduated measuring rods called ''decempedae'' ("10-footers") and ''gromatici'' who used a groma, a sighting device consisting of a vertical staff with horizontal cross pieces and vertical plumb-lines. Ideally the process started in the centre of the planned camp at the site of the headquarters tent or building (principia). Streets and other features were marked with coloured pennants or rods.

The street plans of various present-day cities still retain traces of a Roman camp, for example Marsala in Sicily, the ancient Lilybaeum, where the name of the main street, the Cassaro, perpetuates the name "castrum".

The ideal enforced a linear plan for a camp or fort: a square for camps to contain one legion or smaller unit, a rectangle for two legions, each legion being placed back-to-back with headquarters next to each other. Laying it out was a geometric exercise conducted by experienced officers called ''metatores'', who used graduated measuring rods called ''decempedae'' ("10-footers") and ''gromatici'' who used a groma, a sighting device consisting of a vertical staff with horizontal cross pieces and vertical plumb-lines. Ideally the process started in the centre of the planned camp at the site of the headquarters tent or building (principia). Streets and other features were marked with coloured pennants or rods.

The street plans of various present-day cities still retain traces of a Roman camp, for example Marsala in Sicily, the ancient Lilybaeum, where the name of the main street, the Cassaro, perpetuates the name "castrum".

Wall and ditch

The Castrum's special structure also defended from attacks.

The base (''munimentum'', "fortification") was placed entirely within the ''

The Castrum's special structure also defended from attacks.

The base (''munimentum'', "fortification") was placed entirely within the ''vallum

Vallum is either the whole or a portion of the fortifications of a Roman camp. The vallum usually comprised an earthen or turf rampart (Agger) with a wooden palisade on top, with a deep outer ditch (fossa). The name is derived from '' vallus'' (a ...

'' ("wall"), which could be constructed under the protection of the legion in battle formation if necessary. The ''vallum'' was quadrangular aligned on the cardinal points of the compass. The construction crews dug a trench (''fossa''), throwing the excavated material inward, to be formed into the rampart (''agger''). On top of this a palisade of stakes ('' sudes'' or ''valli'') was erected. The soldiers had to carry these stakes on the march. Over the course of time, the palisade might be replaced by a fine brick or stone wall, and the ditch

A ditch is a small to moderate divot created to channel water. A ditch can be used for drainage, to drain water from low-lying areas, alongside roadways or fields, or to channel water from a more distant source for plant irrigation. Ditches ar ...

serve also as a moat. A legion-sized camp always placed towers at intervals along the wall with positions between for the division artillery.

Interval

Around the inside periphery of the ''vallum'' was a clear space, the ''intervallum'', which served to catch enemy missiles, as an access route to the ''vallum'' and as a storage space for cattle (''capita'') and plunder (''praeda''). Legionaries were quartered in a peripheral zone inside the ''intervallum'', which they could rapidly cross to take up position on the ''vallum''. Inside of the legionary quarters was a peripheral road, the ''Via Sagularis'', probably a type of "service road", as the ''sagum

The sagum was a garment of note generally worn by members of the Roman military during both the Republic and early Empire. Regarded symbolically as one of war by the same tradition which embraced the toga as a garment of peace,{{cite encycloped ...

'', a kind of cloak, was the garment of soldiers.

Streets, gates and central plaza

Every camp included "main street", which ran through the camp in a north–south direction and was very wide. The names of streets in many cities formerly occupied by the Romans suggest that the street was called ''

Every camp included "main street", which ran through the camp in a north–south direction and was very wide. The names of streets in many cities formerly occupied by the Romans suggest that the street was called ''cardo

A cardo (plural ''cardines'') was a north–south street in Ancient Roman cities and military camps as an integral component of city planning. The cardo maximus, or most often the ''cardo'', was the main or central north–south-oriented street.

...

'' or ''cardus maximus''. This name applies more to cities than it does to ancient camps.

Typically "main street" was the ''via principalis''. The central portion was used as a parade ground and headquarters area. The "headquarters" building was called the ''praetorium

The Latin term (also and ) originally identified the tent of a general within a Roman castrum (encampment), and derived from the title praetor, which identified a Roman magistrate.Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, 2 ed., ...

'' because it housed the ''praetor

Praetor ( , ), also pretor, was the title granted by the government of Ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected '' magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to discharge vari ...

'' or base commander ("first officer"), and his staff. In the camp of a full legion he held the rank of ''consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throu ...

'' or ''proconsul

A proconsul was an official of ancient Rome who acted on behalf of a consul. A proconsul was typically a former consul. The term is also used in recent history for officials with delegated authority.

In the Roman Republic, military command, or ...

'' but officers of lesser ranks might command.

On one side of the ''praetorium'' was the ''quaestorium'', the building of the '' quaestor'' (supply officer). On the other side was the ''forum

Forum or The Forum (plural forums or fora) may refer to:

Common uses

* Forum (legal), designated space for public expression in the United States

*Forum (Roman), open public space within a Roman city

**Roman Forum, most famous example

*Internet ...

'', a small duplicate of an urban forum, where public business could be conducted. Along the ''Via Principalis'' were the homes or tents of the several tribune

Tribune () was the title of various elected officials in ancient Rome. The two most important were the tribunes of the plebs and the military tribunes. For most of Roman history, a college of ten tribunes of the plebs acted as a check on th ...

s in front of the barracks of the units they commanded.

The ''Via Principalis'' went through the ''vallum'' in the ''Porta Principalis Dextra'' ("right principal gate") and ''Porta Principalis Sinistra'' ("left, etc."), which were gates fortified with ''turres'' ("towers"). Which was on the north and which on the south depends on whether the praetorium faced east or west, which remains unknown.

The central region of the ''Via Principalis'' with the buildings for the command staff was called the ''Principia'' (plural of ''principium''). It was actually a square, as across this at right angles to the ''Via Principalis'' was the ''Via Praetoria'', so called because the ''praetorium'' interrupted it. The ''Via Principalis'' and the ''Via Praetoria'' offered another division of the camp into four quarters.

Across the central plaza (''principia'') to the east or west was the main gate, the ''Porta Praetoria''. Marching through it and down "headquarters street" a unit ended up in formation in front of the headquarters. The standards of the legion were located on display there, very much like the flag of modern camps.

On the other side of the praetorium the ''Via Praetoria'' continued to the wall, where it went through the ''Porta Decumana''. In theory this was the back gate. Supplies were supposed to come in through it and so it was also called, descriptively, the ''Porta Quaestoria''. The term Decumana, "of the 10th", came from the arranging of ''manipuli'' or ''turmae'' from the first to the 10th, such that the 10th was near the ''intervallum'' on that side. The ''Via Praetoria'' on that side might take the name ''Via Decumana'' or the entire ''Via Praetoria'' be replaced with ''Decumanus Maximus''.

Across the central plaza (''principia'') to the east or west was the main gate, the ''Porta Praetoria''. Marching through it and down "headquarters street" a unit ended up in formation in front of the headquarters. The standards of the legion were located on display there, very much like the flag of modern camps.

On the other side of the praetorium the ''Via Praetoria'' continued to the wall, where it went through the ''Porta Decumana''. In theory this was the back gate. Supplies were supposed to come in through it and so it was also called, descriptively, the ''Porta Quaestoria''. The term Decumana, "of the 10th", came from the arranging of ''manipuli'' or ''turmae'' from the first to the 10th, such that the 10th was near the ''intervallum'' on that side. The ''Via Praetoria'' on that side might take the name ''Via Decumana'' or the entire ''Via Praetoria'' be replaced with ''Decumanus Maximus''.

Canteen

In peaceful times the camp set up a marketplace with the natives in the area. They were allowed into the camp as far as the units numbered 5 (half-way to the praetorium). There another street crossed the camp at right angles to the ''Via Decumana'', called the ''Via Quintana'', "5th street". If the camp needed more gates, one or two of the ''Porta Quintana'' were built, presumably named ''dextra'' and ''sinistra''. If the gates were not built, the ''Porta Decumana'' also became the ''Porta Quintana''. At "5th street" a public market was allowed.Major buildings

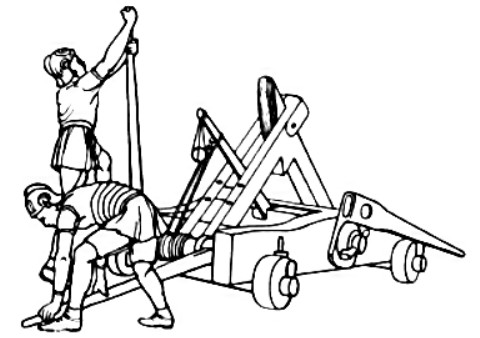

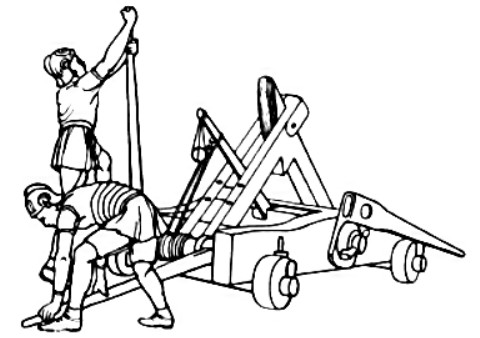

The ''Via Quintana'' and the ''Via Principalis'' divided the camp into three districts: the ''Latera Praetorii'', the ''Praetentura'' and the ''Retentura''. In the ''latera'' ("sides") were the ''Arae'' (sacrificial altars), the ''Auguratorium'' (for auspices), the ''Tribunal'', where courts martial and arbitrations were conducted (it had a raised platform), the guardhouse, the quarters of various kinds of staff and the storehouses for grain (''horrea'') or meat (''carnarea''). Sometimes the ''horrea'' were located near the barracks and the meat was stored on the hoof. Analysis of sewage from latrines indicates the legionary diet was mainly grain. Also located in the ''Latera'' was the ''Armamentarium'', a long shed containing any heavy weapons and artillery not on the wall.

The ''Via Quintana'' and the ''Via Principalis'' divided the camp into three districts: the ''Latera Praetorii'', the ''Praetentura'' and the ''Retentura''. In the ''latera'' ("sides") were the ''Arae'' (sacrificial altars), the ''Auguratorium'' (for auspices), the ''Tribunal'', where courts martial and arbitrations were conducted (it had a raised platform), the guardhouse, the quarters of various kinds of staff and the storehouses for grain (''horrea'') or meat (''carnarea''). Sometimes the ''horrea'' were located near the barracks and the meat was stored on the hoof. Analysis of sewage from latrines indicates the legionary diet was mainly grain. Also located in the ''Latera'' was the ''Armamentarium'', a long shed containing any heavy weapons and artillery not on the wall.

The ''Praetentura'' ("stretching to the front") contained the ''Scamnum Legatorum'', the quarters of officers who were below general but higher than company commanders (''Legati''). Near the ''Principia'' were the ''Valetudinarium'' (hospital), ''Veterinarium'' (for horses), ''Fabrica'' ("workshop", metals and wood), and further to the front the quarters of special forces. These included ''Roman navy, Classici'' ("marines", as most European camps were on rivers and contained a river naval command), ''Equites'' ("cavalry"), ''Speculatores, Exploratores'' ("scouts"), and ''Vexillarii'' (carriers of vexillae, the official pennants of the legion and its units). Troops who did not fit elsewhere also were there.

The part of the ''Retentura'' ("stretching to the rear") closest to the ''Principia'' contained the ''Quaestorium''. By the late empire it had developed also into a safekeep for plunder and a prison for hostages and high-ranking enemy captives. Near the ''Quaestorium'' were the quarters of the headquarters guard (''Statores''), who amounted to two Centuria, centuries (companies). If the ''Imperator'' was present they served as his bodyguard.

The ''Praetentura'' ("stretching to the front") contained the ''Scamnum Legatorum'', the quarters of officers who were below general but higher than company commanders (''Legati''). Near the ''Principia'' were the ''Valetudinarium'' (hospital), ''Veterinarium'' (for horses), ''Fabrica'' ("workshop", metals and wood), and further to the front the quarters of special forces. These included ''Roman navy, Classici'' ("marines", as most European camps were on rivers and contained a river naval command), ''Equites'' ("cavalry"), ''Speculatores, Exploratores'' ("scouts"), and ''Vexillarii'' (carriers of vexillae, the official pennants of the legion and its units). Troops who did not fit elsewhere also were there.

The part of the ''Retentura'' ("stretching to the rear") closest to the ''Principia'' contained the ''Quaestorium''. By the late empire it had developed also into a safekeep for plunder and a prison for hostages and high-ranking enemy captives. Near the ''Quaestorium'' were the quarters of the headquarters guard (''Statores''), who amounted to two Centuria, centuries (companies). If the ''Imperator'' was present they served as his bodyguard.

Barracks

Further from the ''Quaestorium'' were the tents of the ''Nationes'' ("natives"), who were auxiliaries of foreign troops, and the legionaries themselves in double rows of tents or barracks (''Strigae''). One ''Striga'' was as long as required and 18 m wide. In it were two ''Hemistrigia'' of facing tents centered in its 9 m strip. Arms could be stacked before the tents and baggage carts kept there as well. Space on the other side of the tent was for passage.

In the northern places like Britain, where it got cold in the winter, they would make wood or stone barracks. The Romans would also put a fireplace in the barracks. They had about three bunk beds in it. They had a small room beside it where they put their armour; it was as big as the tents. They would also make these barracks if the fort they had was going to stay there for good.

A tent was 3 by 3.5 metres (0.6 m for the aisle), ten men per tent. Ideally a company took 10 tents, arranged in a line of 10 companies, with the 10th near the ''Porta Decumana''. Of the c. 9.2 square metres of bunk space each man received 0.9, or about 0.6 by 1.5 m, which was only practical if they slept with heads to the aisle. The single tent with its men was called ''Contubernium (Roman army unit), contubernium'', also used for "squad". A squad during some periods was 8 men or fewer.

The ''Centurion'', or company commander, had a double-sized tent for his quarters, which served also as official company area. Other than there, the men had to find other places to be. To avoid mutiny, it became extremely important for the officers to keep them busy.

A covered portico might protect the walkway along the tents. If barracks had been constructed, one company was housed in one barracks building, with the arms at one end and the common area at the other. The company area was used for cooking and recreation, such as gaming. The army provisioned the men and had their bread (''panis militaris'') baked in outdoor ovens, but the men were responsible for cooking and serving themselves. They could buy meals or supplementary foods at the canteen. The officers were allowed servants.

Further from the ''Quaestorium'' were the tents of the ''Nationes'' ("natives"), who were auxiliaries of foreign troops, and the legionaries themselves in double rows of tents or barracks (''Strigae''). One ''Striga'' was as long as required and 18 m wide. In it were two ''Hemistrigia'' of facing tents centered in its 9 m strip. Arms could be stacked before the tents and baggage carts kept there as well. Space on the other side of the tent was for passage.

In the northern places like Britain, where it got cold in the winter, they would make wood or stone barracks. The Romans would also put a fireplace in the barracks. They had about three bunk beds in it. They had a small room beside it where they put their armour; it was as big as the tents. They would also make these barracks if the fort they had was going to stay there for good.

A tent was 3 by 3.5 metres (0.6 m for the aisle), ten men per tent. Ideally a company took 10 tents, arranged in a line of 10 companies, with the 10th near the ''Porta Decumana''. Of the c. 9.2 square metres of bunk space each man received 0.9, or about 0.6 by 1.5 m, which was only practical if they slept with heads to the aisle. The single tent with its men was called ''Contubernium (Roman army unit), contubernium'', also used for "squad". A squad during some periods was 8 men or fewer.

The ''Centurion'', or company commander, had a double-sized tent for his quarters, which served also as official company area. Other than there, the men had to find other places to be. To avoid mutiny, it became extremely important for the officers to keep them busy.

A covered portico might protect the walkway along the tents. If barracks had been constructed, one company was housed in one barracks building, with the arms at one end and the common area at the other. The company area was used for cooking and recreation, such as gaming. The army provisioned the men and had their bread (''panis militaris'') baked in outdoor ovens, but the men were responsible for cooking and serving themselves. They could buy meals or supplementary foods at the canteen. The officers were allowed servants.

Sanitation

For sanitary facilities, a camp had both public and private latrines. A public latrine consisted of a bank of seats situated over a channel of running water. One of the major considerations for selecting the site of a camp was the presence of running water, which the engineers diverted into the sanitary channels. Drinking water came from wells; however, the larger and more permanent bases featured the ''Roman aqueduct, aqueduct'', a structure running a stream captured from high ground (sometimes miles away) into the camp. The praetorium had its own latrine, and probably the quarters of the high-ranking officers. In or near the ''intervallum'', where they could easily be accessed, were the latrines of the soldiers. A public bathhouse for the soldiers, also containing a latrine, was located near or on the ''Via Principalis''.Territory

The influence of a base extended far beyond its walls. The total land required for the maintenance of a permanent base was called its ''territoria''. In it were located all the resources of nature and the terrain required by the base: pastures, woodlots, water sources, stone quarries, mines, exercise fields and attached villages. The central castra might also support various fortified adjuncts to the main base, which were not in themselves self-sustaining (as was the base). In this category were ''speculae'', "watchtowers", ''castella'', "small camps", and naval bases.

All the major bases near rivers featured some sort of fortified naval installation, one side of which was formed by the river or lake. The other sides were formed by a polygonal wall and ditch constructed in the usual way, with gates and watchtowers. The main internal features were the boat sheds and the docks. When not in use, the boats were drawn up into the sheds for maintenance and protection. Since the camp was placed to best advantage on a hill or slope near the river, the naval base was usually outside its walls. The ''classici'' and the ''optiones'' of the naval installation relied on the camp for its permanent defense. Naval personnel generally enjoyed better quarters and facilities. Many were civilians working for the military.

The influence of a base extended far beyond its walls. The total land required for the maintenance of a permanent base was called its ''territoria''. In it were located all the resources of nature and the terrain required by the base: pastures, woodlots, water sources, stone quarries, mines, exercise fields and attached villages. The central castra might also support various fortified adjuncts to the main base, which were not in themselves self-sustaining (as was the base). In this category were ''speculae'', "watchtowers", ''castella'', "small camps", and naval bases.

All the major bases near rivers featured some sort of fortified naval installation, one side of which was formed by the river or lake. The other sides were formed by a polygonal wall and ditch constructed in the usual way, with gates and watchtowers. The main internal features were the boat sheds and the docks. When not in use, the boats were drawn up into the sheds for maintenance and protection. Since the camp was placed to best advantage on a hill or slope near the river, the naval base was usually outside its walls. The ''classici'' and the ''optiones'' of the naval installation relied on the camp for its permanent defense. Naval personnel generally enjoyed better quarters and facilities. Many were civilians working for the military.

Modifications in practice

This ideal was always modified to suit the terrain and the circumstances. Each camp discovered by archaeology has its own specific layout and architectural features, which makes sense from a military point of view. If, for example, the camp was built on an outcrop, it followed the lines of the outcrop. The terrain for which it was best suited and for which it was probably designed in distant prehistoric times was the rolling plain. The camp was best placed on the summit and along the side of a low hill, with spring water running in rivulets through the camp (''aquatio'') and pastureland to provide grazing (''pabulatio'') for the animals. In case of attack, arrows, javelins and sling missiles could be fired down at an enemy tiring himself to come up. For defence troops could be formed in an ''acies'', or "battle-line", outside the gates, where they could be easily resupplied and replenished, as well as being supported by archery from the palisade. The streets, gates and buildings present depended on the requirements and resources of the camp. The gates might vary from two to six and not be centred on the sides. Not all the streets and buildings might be present.Quadrangular camps in later times

Many settlements in Europe originated as Roman military camps and still show traces of their original pattern (e.g. Castres in France, Barcelona inSpain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

). The pattern was also used by Spanish colonization of the Americas, Spanish colonizers in America following strict rules by the Spanish monarchy for founding new cities in the New World.

Many of the towns of England still retain forms of the word ''castra'' in their names, usually as the suffixes "-caster", "-cester" or "-chester" – Lancaster, England, Lancaster, Tadcaster, Worcester, England, Worcester, Gloucester, Mancetter, Uttoxeter, Colchester, Chester, Manchester and Ribchester for example. Castle has the same derivation, from the diminutive ''castellum'' or "little fort", but does not usually indicate a former Roman camp. Whitley Castle however is an exception, referring to the Roman fort of Epiacum in Northumberland. It is now provided with a car park and café and open to the public under its Roman name of Epiacum.

Camp life

Activities conducted in a castra can be divided into ordinary and "the duty" or "the watch". Ordinary activity was performed during regular working hours. The duty was associated with operating the installation as a military facility. For example, none of the soldiers were required to man the walls all the time, but round-the clock duty always required a portion of the soldiers to be on duty at any time. Duty time was divided into ''vigilia'', the eight watches into which the 24-hour day was divided so they stood guard for 3 hours that day. The Romans used signals on brass instruments to mark time. These were mainly the ''buccina'' or ''bucina'', the ''cornu (horn), cornu'' and the ''Roman tuba, tuba''. As they did not possess valves for regulating the pitch, the range of these instruments was somewhat limited. Nevertheless, the musicians (''Aenatores'', "brassmen") managed to define enough signals for issuing commands. The instrument used to mark the passage of a watch was the ''buccina'', from which the trumpet derives. It was sounded by a ''buccinator''.Ordinary life

Ordinary camp life began with a ''buccina'' call at daybreak, the first watch of the day. The soldiers arose at this time and shortly after collected in the company area for breakfast and assembly. The centurions were up before them and off to the ''principia'' where they and the ''equites'' were required to assemble. The regimental commanders, the tribunes, were already converging on the ''praetorium''. There the general staff was busily at work planning the day. At a staff meeting the ''Tribunes'' received the password and the orders of the day. They brought those back to the ''centuriones'', who returned to their company areas to instruct the men.

For soldiers, the main item of the agenda was a vigorous training session lasting about a watch long. Recruits received two, one in the morning and one in the afternoon.Vegetius Book I, linked in Primary sources below. Planning and supervision of training were under a general staff officer, who might manage training at several camps. According to Vegetius, the men might take a hike or a jog under full pack, or swim a river. Marching drill was always in order.

Each soldier was taught the use of every weapon and also was taught to ride. Seamanship was taught at naval bases. Soldiers were generalists in the military and construction arts. They practiced archery, spear-throwing and above all swordsmanship against posts (''pali'') fixed in the ground. Training was taken very seriously and was democratic. Ordinary soldiers would see all the officers training with them including the ''praetor'', or the Emperor, if he was in camp.

Swordsmanship lessons and use of the shooting range probably took place on the ''campus'', a "field" outside the ''castra'', from which English camp derives. Its surface could be lightly paved. Winter curtailed outdoor training. The general might in that case have sheds constructed, which served as field houses for training. There is archaeological evidence in one case of an indoor equestrian ring.

Apart from the training, each soldier had a regular job on the base, of which there were a large variety from the various kinds of clerks to the craftsmen. Soldiers changed jobs frequently. The commander's policy was to have all the soldiers skilled in all the arts and crafts so that they could be as interchangeable as possible. Even then the goal was not entirely achievable. The gap was bridged by the specialists, the ''optiones'' or "chosen men", of which there were many different kinds. For example, a skilled artisan might be chosen to superintend a workshop. Soldiers were also expected to build the camp upon arrival before engaging in any sort of warfare after a day's march.

Ordinary camp life began with a ''buccina'' call at daybreak, the first watch of the day. The soldiers arose at this time and shortly after collected in the company area for breakfast and assembly. The centurions were up before them and off to the ''principia'' where they and the ''equites'' were required to assemble. The regimental commanders, the tribunes, were already converging on the ''praetorium''. There the general staff was busily at work planning the day. At a staff meeting the ''Tribunes'' received the password and the orders of the day. They brought those back to the ''centuriones'', who returned to their company areas to instruct the men.

For soldiers, the main item of the agenda was a vigorous training session lasting about a watch long. Recruits received two, one in the morning and one in the afternoon.Vegetius Book I, linked in Primary sources below. Planning and supervision of training were under a general staff officer, who might manage training at several camps. According to Vegetius, the men might take a hike or a jog under full pack, or swim a river. Marching drill was always in order.

Each soldier was taught the use of every weapon and also was taught to ride. Seamanship was taught at naval bases. Soldiers were generalists in the military and construction arts. They practiced archery, spear-throwing and above all swordsmanship against posts (''pali'') fixed in the ground. Training was taken very seriously and was democratic. Ordinary soldiers would see all the officers training with them including the ''praetor'', or the Emperor, if he was in camp.

Swordsmanship lessons and use of the shooting range probably took place on the ''campus'', a "field" outside the ''castra'', from which English camp derives. Its surface could be lightly paved. Winter curtailed outdoor training. The general might in that case have sheds constructed, which served as field houses for training. There is archaeological evidence in one case of an indoor equestrian ring.

Apart from the training, each soldier had a regular job on the base, of which there were a large variety from the various kinds of clerks to the craftsmen. Soldiers changed jobs frequently. The commander's policy was to have all the soldiers skilled in all the arts and crafts so that they could be as interchangeable as possible. Even then the goal was not entirely achievable. The gap was bridged by the specialists, the ''optiones'' or "chosen men", of which there were many different kinds. For example, a skilled artisan might be chosen to superintend a workshop. Soldiers were also expected to build the camp upon arrival before engaging in any sort of warfare after a day's march.

The supply administration was run as a business using money as the medium of exchange. The aureus was the preferred coin of the late republic and early empire; in the late empire the Solidus (coin), solidus came into use. The larger bases, such as ''Moguntiacum'', minted their own coins. As does any business, the base quaestorium required careful record keeping, performed mainly by the optiones. A chance cache of tablets from Vindolanda in Britain gives us a glimpse of some supply transactions. They record, among other things, the purchase of consumables and raw supplies, the storage and repair of clothing and other items, and the sale of items, including foodstuffs, to achieve an income. Vindolanda traded vigorously with the surrounding natives.

Another feature of the camp was the military hospital (''valetudinarium'', later ''hospitium''). Augustus instituted the first permanent medical corps in the Roman army. Its physicians, the ''medici ordinarii'', had to be qualified physicians. They were allowed medical students, practitioners and whatever orderlies they needed; i.e., the military hospitals were medical schools and places of residency as well.

Officers were allowed to marry and to reside with their families on base. The army did not extend the same privileges to the men, who were not allowed to marry. However, they often kept common law families off base in communities nearby. The communities might be native, as the tribesmen tended to build around a permanent base for purposes of trade, but also the base sponsored villages (''vici'') of dependents and businessmen. Dependants were not allowed to follow an army on the march into hostile territory.

Military service was for about 25 years. At the end of that time, the veteran was given a certificate of honorable discharge (''honesta missio''). Some of these have survived engraved on stone. Typically they certify that the veteran, his wife (one per veteran) and children or his sweetheart were now Roman citizens, which is a good indication that troops, which were used chiefly on the frontier, were from peoples elsewhere on the frontier who wished to earn Roman citizenship. However, under Antoninus Pius, citizenship was no longer granted to the children of rank-and-file veterans, the privilege becoming restricted only to officers.

Veterans often went into business in the communities near a base. They became permanent members of the community and would stay on after the troops were withdrawn, as in the notable case of Saint Patrick's family.

The supply administration was run as a business using money as the medium of exchange. The aureus was the preferred coin of the late republic and early empire; in the late empire the Solidus (coin), solidus came into use. The larger bases, such as ''Moguntiacum'', minted their own coins. As does any business, the base quaestorium required careful record keeping, performed mainly by the optiones. A chance cache of tablets from Vindolanda in Britain gives us a glimpse of some supply transactions. They record, among other things, the purchase of consumables and raw supplies, the storage and repair of clothing and other items, and the sale of items, including foodstuffs, to achieve an income. Vindolanda traded vigorously with the surrounding natives.

Another feature of the camp was the military hospital (''valetudinarium'', later ''hospitium''). Augustus instituted the first permanent medical corps in the Roman army. Its physicians, the ''medici ordinarii'', had to be qualified physicians. They were allowed medical students, practitioners and whatever orderlies they needed; i.e., the military hospitals were medical schools and places of residency as well.

Officers were allowed to marry and to reside with their families on base. The army did not extend the same privileges to the men, who were not allowed to marry. However, they often kept common law families off base in communities nearby. The communities might be native, as the tribesmen tended to build around a permanent base for purposes of trade, but also the base sponsored villages (''vici'') of dependents and businessmen. Dependants were not allowed to follow an army on the march into hostile territory.