Boshin War mortar.jpg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The , sometimes known as the Japanese Revolution or Japanese Civil War, was a

The , sometimes known as the Japanese Revolution or Japanese Civil War, was a

The Shogun had sought French assistance for training and weaponry since 1865. Léon Roches, French consul to Japan, supported the Shogunal military reform efforts to promote French influence, hoping to make Japan into a dependent client state. This caused the British to send their own military mission to compete with the French.

Despite the bombardment of Kagoshima, the Satsuma Domain had become closer to the British and was pursuing the modernization of its army and navy with their support. The Scottish merchant

The Shogun had sought French assistance for training and weaponry since 1865. Léon Roches, French consul to Japan, supported the Shogunal military reform efforts to promote French influence, hoping to make Japan into a dependent client state. This caused the British to send their own military mission to compete with the French.

Despite the bombardment of Kagoshima, the Satsuma Domain had become closer to the British and was pursuing the modernization of its army and navy with their support. The Scottish merchant

Following a

Following a

Numerous types of more or less modern

Numerous types of more or less modern

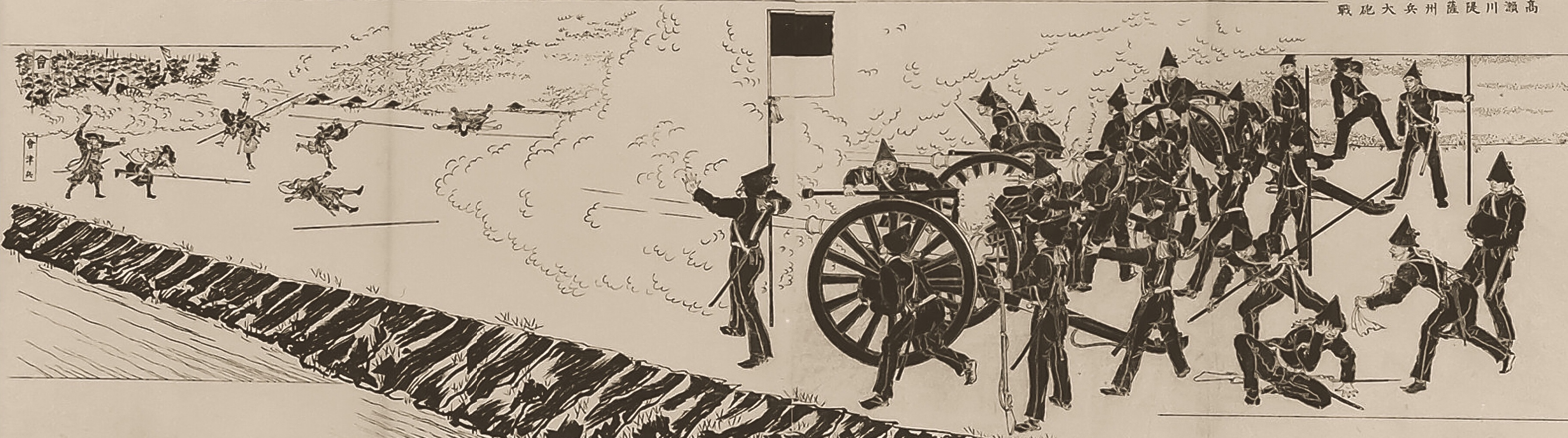

For artillery,

For artillery,

On January 27, 1868, shogunate forces attacked the forces of Chōshū and Satsuma, clashing near Toba and Fushimi, at the southern entrance to Kyoto in the Battle of Toba–Fushimi. Some parts of the 15,000-strong shogunate forces had been trained by French military advisers. Among their numbers during this battle were the noted ''

On January 27, 1868, shogunate forces attacked the forces of Chōshū and Satsuma, clashing near Toba and Fushimi, at the southern entrance to Kyoto in the Battle of Toba–Fushimi. Some parts of the 15,000-strong shogunate forces had been trained by French military advisers. Among their numbers during this battle were the noted '' After the defections, Yoshinobu, apparently distressed by the imperial approval given to the actions of Satsuma and Chōshū, fled

After the defections, Yoshinobu, apparently distressed by the imperial approval given to the actions of Satsuma and Chōshū, fled

Beginning in February, with the help of the French ambassador

Beginning in February, with the help of the French ambassador

After Yoshinobu's surrender, he was placed under house arrest, and stripped of all titles, land and power. He was later released, when he demonstrated no further interest and ambition in national affairs. He retired to

After Yoshinobu's surrender, he was placed under house arrest, and stripped of all titles, land and power. He was later released, when he demonstrated no further interest and ambition in national affairs. He retired to  Enomoto's fleet reached Sendai harbour on August 26. Although the Northern Coalition was numerous, it was poorly equipped, and relied on traditional fighting methods. Modern armament was scarce, and last-minute efforts were made to build

Enomoto's fleet reached Sendai harbour on August 26. Although the Northern Coalition was numerous, it was poorly equipped, and relied on traditional fighting methods. Modern armament was scarce, and last-minute efforts were made to build

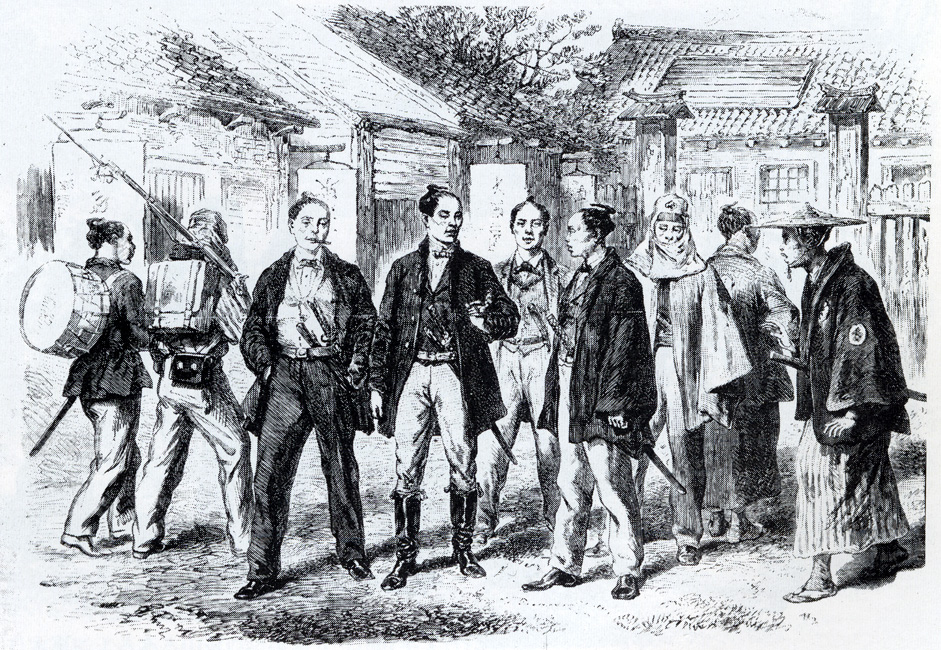

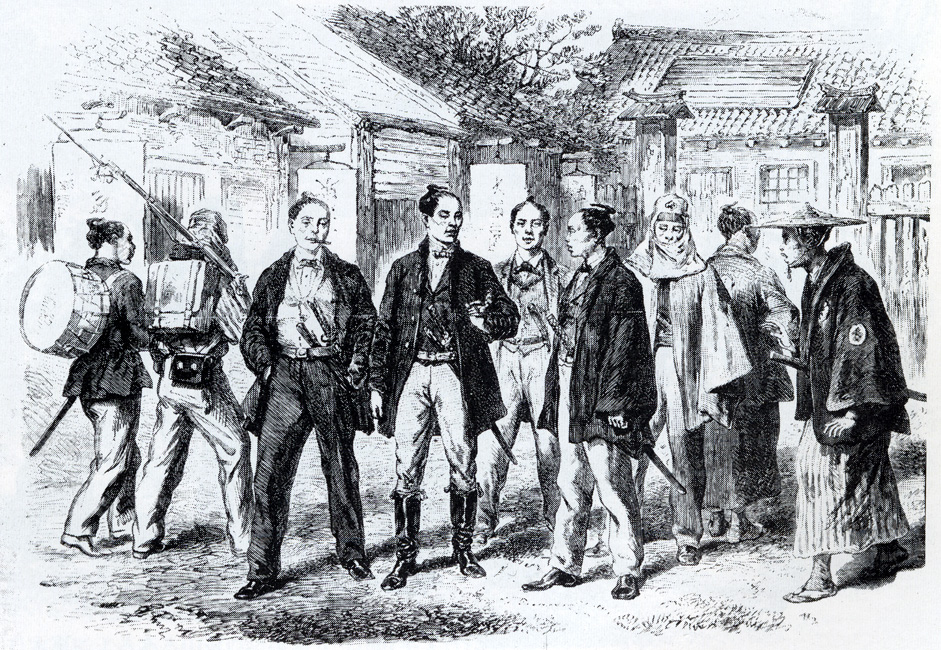

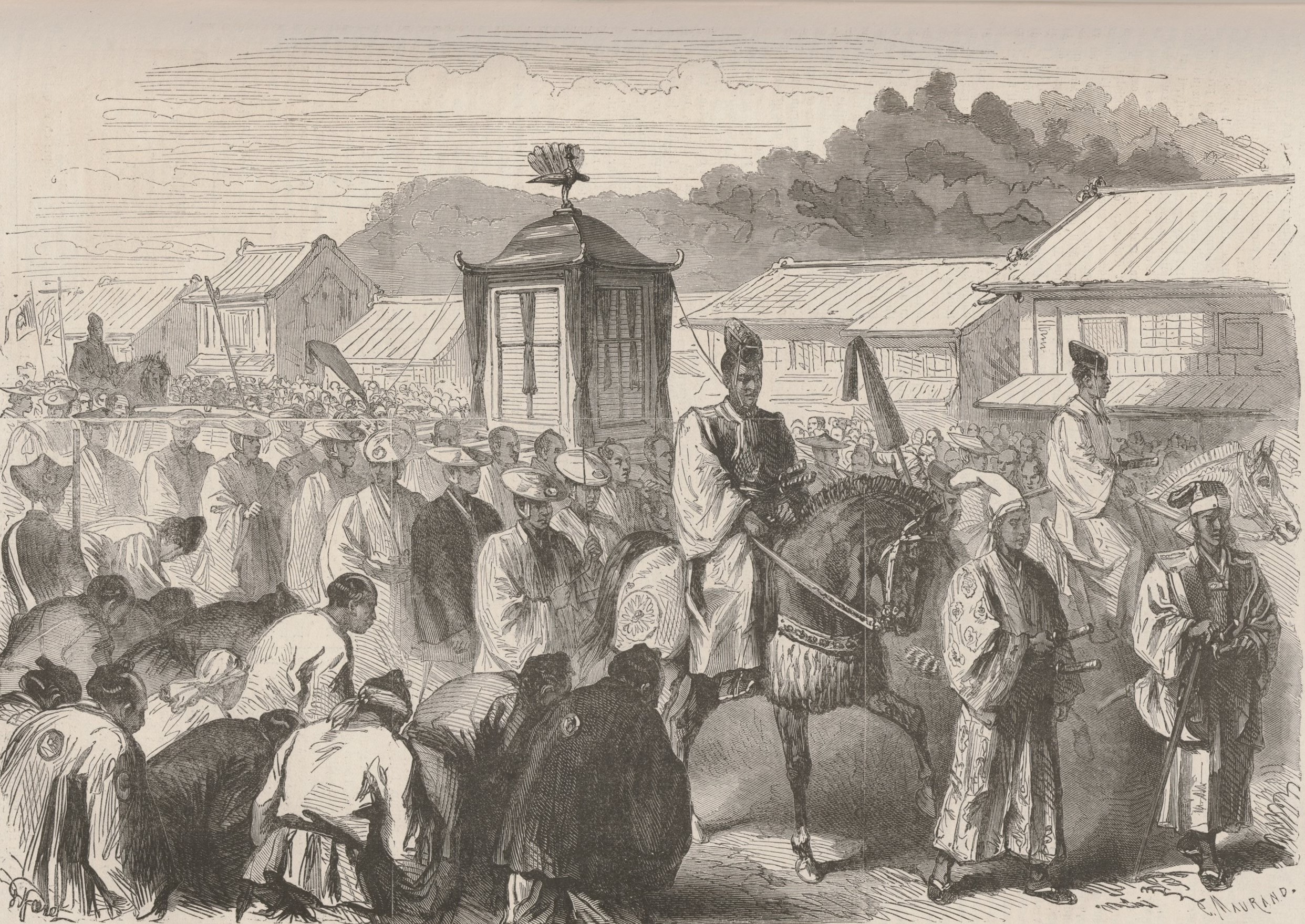

Image:French Military Advisors Jules Brunet and Japanese Allies Boshin War 1868-1869.png, 225px, The Japanese and their French military advisers in Hokkaido

poly 0 350 18 341 48 315 47 304 36 305 22 283 22 246 36 220 65 210 69 194 62 171 66 136 94 132 109 152 104 201 140 219 150 231 156 285 145 369 118 391 68 391 54 433 49 462 10 457 Hosoya Yasutaro

poly 224 555 152 405 172 353 186 294 184 237 216 224 219 202 211 165 229 146 250 146 267 156 271 168 284 171 272 182 273 216 304 224 323 289 323 349 333 388 339 431 326 450 339 529 306 552 Captain Jules Brunet

poly 324 560 355 524 348 388 337 375 334 343 342 299 369 265 393 230 410 224 404 202 404 185 392 185 399 175 399 163 435 150 454 159 463 169 463 205 468 224 498 241 509 257 517 308 519 330 496 394 473 558 Commander in chief Matsudaira Taro

poly 548 372 531 327 528 285 529 244 545 231 575 212 558 192 558 175 556 175 554 147 560 138 577 131 594 131 609 159 605 165 610 187 610 212 646 227 679 261 708 299 670 363 666 383 657 387 664 396 671 449 716 503 714 517 658 453 654 534 528 535 Tajima Kintaro

poly 162 365 148 235 109 184 117 144 135 106 164 92 175 78 169 49 169 31 178 24 195 24 208 35 215 41 215 47 207 55 208 72 217 82 225 91 253 104 263 141 193 365 Captain Cazeneuve

poly 265 227 267 150 272 139 297 129 293 106 287 91 294 66 305 60 321 60 333 71 338 78 344 81 344 89 340 97 336 103 334 122 360 139 365 139 376 149 391 179 398 226 358 245 371 305 315 362 Sargeant Jean Marlin

poly 380 222 386 171 404 151 405 134 399 116 403 114 396 99 410 86 444 97 451 104 451 109 442 115 444 133 441 142 460 170 Fukushima Tokinosuke

poly 457 166 461 121 475 104 503 89 509 82 499 72 496 48 489 21 523 17 539 37 541 48 534 71 534 78 547 91 565 99 580 104 627 185 623 210 545 307 577 481 469 493 Sergeant Arthur Fortant

rect 0 0 713 561 Use button to enlarge or cursor to investigate

desc none

Following defeat on Honshū, Enomoto Takeaki fled to Hokkaidō with the remnants of the navy and his handful of French advisers. Together they organized a government, with the objective of establishing an independent island nation dedicated to the development of Hokkaidō. They formally established the

The Imperial Navy reached the harbour of Miyako on March 20, but anticipating the arrival of the Imperial ships, the Ezo rebels organized a daring plan to seize the ''Kōtetsu''. Led by Shinsengumi commander Hijikata Toshizō, three warships were dispatched for a surprise attack, in what is known as the Battle of Miyako Bay. The battle ended in failure for the Tokugawa side, owing to bad weather, engine trouble and the decisive use of a Gatling gun by Imperial troops against samurai boarding parties.

Imperial forces soon consolidated their hold on mainland Japan, and, in April 1869, dispatched a fleet and an infantry force of 7,000 to Ezo, starting the

The Imperial Navy reached the harbour of Miyako on March 20, but anticipating the arrival of the Imperial ships, the Ezo rebels organized a daring plan to seize the ''Kōtetsu''. Led by Shinsengumi commander Hijikata Toshizō, three warships were dispatched for a surprise attack, in what is known as the Battle of Miyako Bay. The battle ended in failure for the Tokugawa side, owing to bad weather, engine trouble and the decisive use of a Gatling gun by Imperial troops against samurai boarding parties.

Imperial forces soon consolidated their hold on mainland Japan, and, in April 1869, dispatched a fleet and an infantry force of 7,000 to Ezo, starting the

Of the approximately 120,000 men mobilized over the course of the conflict, about 8,200 were killed and more than 5,000 were wounded. Following victory, the new government proceeded with unifying the country under a single, legitimate and powerful rule by the Imperial Court. The emperor's residence was effectively transferred from

Of the approximately 120,000 men mobilized over the course of the conflict, about 8,200 were killed and more than 5,000 were wounded. Following victory, the new government proceeded with unifying the country under a single, legitimate and powerful rule by the Imperial Court. The emperor's residence was effectively transferred from  The Imperial side did not pursue its objective of expelling foreign interests from Japan, but instead shifted to a more progressive policy aiming at the continued modernization of the country and the renegotiation of

The Imperial side did not pursue its objective of expelling foreign interests from Japan, but instead shifted to a more progressive policy aiming at the continued modernization of the country and the renegotiation of  Upon his coronation, Meiji issued his Charter Oath, calling for deliberative assemblies, promising increased opportunities for the common people, abolishing the "evil customs of the past", and seeking knowledge throughout the world "to strengthen the foundations of imperial rule".Jansen, p. 338. The reforms culminated in the 1889 issuance of the

Upon his coronation, Meiji issued his Charter Oath, calling for deliberative assemblies, promising increased opportunities for the common people, abolishing the "evil customs of the past", and seeking knowledge throughout the world "to strengthen the foundations of imperial rule".Jansen, p. 338. The reforms culminated in the 1889 issuance of the

In modern summaries, the

In modern summaries, the

The Boshin War

* National Archives of Japan

{{featured article 1868 in Japan 1869 in Japan Civil wars involving the states and peoples of Asia Civil wars of the Industrial era Meiji Restoration Wars involving Japan

civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

in Japan fought from 1868 to 1869 between forces of the ruling Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate (, Japanese 徳川幕府 ''Tokugawa bakufu''), also known as the , was the military government of Japan during the Edo period from 1603 to 1868. Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005)"''Tokugawa-jidai''"in ''Japan Encyclopedia ...

and a clique seeking to seize political power in the name of the Imperial Court.

The war stemmed from dissatisfaction among many nobles

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The characteri ...

and young samurai

were the hereditary military nobility and officer caste of medieval and early-modern Japan from the late 12th century until their abolition in 1876. They were the well-paid retainers of the '' daimyo'' (the great feudal landholders). They h ...

with the shogunate's handling of foreigners following the opening of Japan

was the final years of the Edo period when the Tokugawa shogunate ended. Between 1853 and 1867, Japan ended its isolationist foreign policy known as and changed from a feudal Tokugawa shogunate to the modern empire of the Meiji government. ...

during the prior decade. Increasing Western influence in the economy led to a decline similar to that of other Asian countries at the time. An alliance of western samurai, particularly the domains of Chōshū, Satsuma Satsuma may refer to:

* Satsuma (fruit), a citrus fruit

* ''Satsuma'' (gastropod), a genus of land snails

Places Japan

* Satsuma, Kagoshima, a Japanese town

* Satsuma District, Kagoshima, a district in Kagoshima Prefecture

* Satsuma Domain, a sou ...

, and Tosa, and court officials secured control of the Imperial Court and influenced the young Emperor Meiji. Tokugawa Yoshinobu, the sitting ''shōgun

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamak ...

'', realizing the futility of his situation, abdicated and handed over political power to the emperor. Yoshinobu had hoped that by doing this the House of Tokugawa could be preserved and participate in the future government.

However, military movements by imperial forces, partisan violence in Edo, and an imperial decree promoted by Satsuma and Chōshū abolishing the House of Tokugawa led Yoshinobu to launch a military campaign to seize the emperor's court in Kyoto

Kyoto (; Japanese language, Japanese: , ''Kyōto'' ), officially , is the capital city of Kyoto Prefecture in Japan. Located in the Kansai region on the island of Honshu, Kyoto forms a part of the Keihanshin, Keihanshin metropolitan area along wi ...

. The military tide rapidly turned in favour of the smaller but relatively modernized Imperial faction, and, after a series of battles culminating in the surrender of Edo, Yoshinobu personally surrendered. Those loyal to the Tokugawa shōgun retreated to northern Honshū and later to Hokkaidō, where they founded the Republic of Ezo

The was a short-lived separatist state established in 1869 on the island of Ezo, now Hokkaido, by a part of the former military of the Tokugawa shogunate at the end of the ''Bakumatsu'' period in Japan. It was the first government to attempt t ...

. Defeat at the Battle of Hakodate

The was fought in Japan from December 4, 1868 to June 27, 1869, between the remnants of the Tokugawa shogunate army, consolidated into the armed forces of the rebel Ezo Republic, and the armies of the newly formed Imperial government (composed ...

broke this last holdout and left the Emperor as defacto supreme ruler throughout the whole of Japan, completing the military phase of the Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored practical imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Although there were ...

.

Around 69,000 men were mobilized

Mobilization is the act of assembling and readying military troops and supplies for war. The word ''mobilization'' was first used in a military context in the 1850s to describe the preparation of the Prussian Army. Mobilization theories and ...

during the conflict, and of these about 8,200 were killed. In the end, the victorious Imperial faction abandoned its objective of expelling foreigners from Japan and instead adopted a policy of continued modernization with an eye to eventual renegotiation of the unequal treaties with the Western powers. Due to the persistence of Saigō Takamori

was a Japanese samurai and nobleman. He was one of the most influential samurai in Japanese history and one of the three great nobles who led the Meiji Restoration. Living during the late Edo and early Meiji periods, he later led the Satsum ...

, a prominent leader of the Imperial faction, the Tokugawa loyalists were shown clemency

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the j ...

, and many former shogunate leaders and samurai were later given positions of responsibility under the new government.

When the Boshin War began, Japan was already modernizing, following the same course of advancement as that of the industrialized Western nations. Since Western nations, especially the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, were deeply involved in the country's politics, the installation of Imperial power added more turbulence to the conflict. Over time, the war was romanticized as a "bloodless revolution", as the number of casualties was small relative to the size of Japan's population. However, conflicts soon emerged between the western samurai and the modernists in the Imperial faction, which led to the bloodier Satsuma Rebellion

The Satsuma Rebellion, also known as the was a revolt of disaffected samurai against the new imperial government, nine years into the Meiji Era. Its name comes from the Satsuma Domain, which had been influential in the Restoration and b ...

.

Etymology

is the designation for the fifth year of asexagenary cycle

The sexagenary cycle, also known as the Stems-and-Branches or ganzhi ( zh, 干支, gānzhī), is a cycle of sixty terms, each corresponding to one year, thus a total of sixty years for one cycle, historically used for recording time in China and t ...

in traditional East Asian calendars. The characters can also be read as in Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

, literally "Elder Brother of Earth-Dragon". In Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of ...

, it translates as "Yang

Yang may refer to:

* Yang, in yin and yang, one half of the two symbolic polarities in Chinese philosophy

* Korean yang, former unit of currency of Korea from 1892 to 1902

* YANG, a data modeling language for the NETCONF network configuration ...

Earth Dragon", which is associated with that particular year in the sexagenary cycle. The war started in the fourth year of the Keiō

was a after '' Genji'' and before '' Meiji''. The period spanned the years from May 1865 to October 1868. The reigning emperors were and .

Change of era

* May 1, 1865 (''Genji 2/Keiō 1, 7th day of the 4th month'') : The new era name of ''K ...

era

An era is a span of time defined for the purposes of chronology or historiography, as in the regnal eras in the history of a given monarchy, a calendar era used for a given calendar, or the geological eras defined for the history of Earth.

Comp ...

,Nussbaum, p. 505. which also became the first year of the Meiji era in October of that year, and ended in the second year of the Meiji era.Nussbaum, p. 624.

Political background

Early discontent against the shogunate

For the two centuries prior to 1854, Japan had a strict policy of isolationism, restricting all interactions with foreign powers, with the notable exceptions ofKorea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

via Tsushima, Qing China via the Ryukyu Islands

The , also known as the or the , are a chain of Japanese islands that stretch southwest from Kyushu to Taiwan: the Ōsumi, Tokara, Amami, Okinawa, and Sakishima Islands (further divided into the Miyako and Yaeyama Islands), with Yona ...

, and the Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

through the trading post of Dejima

, in the 17th century also called Tsukishima ( 築島, "built island"), was an artificial island off Nagasaki, Japan that served as a trading post for the Portuguese (1570–1639) and subsequently the Dutch (1641–1854). For 220 years, i ...

. In 1854, the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

Commodore

Commodore may refer to:

Ranks

* Commodore (rank), a naval rank

** Commodore (Royal Navy), in the United Kingdom

** Commodore (United States)

** Commodore (Canada)

** Commodore (Finland)

** Commodore (Germany) or ''Kommodore''

* Air commodore ...

Matthew C. Perry

Matthew Calbraith Perry (April 10, 1794 – March 4, 1858) was a commodore of the United States Navy who commanded ships in several wars, including the War of 1812 and the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). He played a leading role in the o ...

's expedition opened Japan to global commerce through the implied threat of force, thus initiating rapid development of foreign trade and Westernization

Westernization (or Westernisation), also Europeanisation or occidentalization (from the ''Occident''), is a process whereby societies come under or adopt Western culture in areas such as industry, technology, science, education, politics, econo ...

. In large part due to the humiliating terms of the unequal treaties

Unequal treaty is the name given by the Chinese to a series of treaties signed during the 19th and early 20th centuries, between China (mostly referring to the Qing dynasty) and various Western powers (specifically the British Empire, France, the ...

, as agreements like those negotiated by Perry are called, the Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate (, Japanese 徳川幕府 ''Tokugawa bakufu''), also known as the , was the military government of Japan during the Edo period from 1603 to 1868. Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005)"''Tokugawa-jidai''"in ''Japan Encyclopedia ...

soon faced internal dissent, which coalesced into a radical movement, the ''sonnō jōi

was a ''yojijukugo'' (four-character compound) phrase used as the rallying cry and slogan of a political movement in Japan in the 1850s and 1860s during the Bakumatsu period. Based on Neo-Confucianism and Japanese nativism, the movement soug ...

'' (meaning "revere the Emperor, expel the barbarians").Hagiwara, p. 34.

Emperor Kōmei

was the 121st Emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession.Imperial Household Agency (''Kunaichō'')孝明天皇 (121)/ref> Kōmei's reign spanned the years from 1846 through 1867, corresponding to the final years of the ...

agreed with such sentiments and, breaking with centuries of Imperial tradition, began to take an active role in matters of state: as opportunities arose, he vehemently protested against the treaties and attempted to interfere in the shogunal succession. His efforts culminated in March 1863 with his "order to expel barbarians

The was an edict issued by the Japanese Emperor Kōmei in 1863 against the Westernization of Japan following the opening of the country by Commodore Perry in 1854.

The order

The edict was based on widespread anti-foreign and legitimist sentim ...

". Although the shogunate had no intention of enforcing it, the order nevertheless inspired attacks against the shogunate itself and against foreigners in Japan: the most famous incident was that of the English trader Charles Lennox Richardson

Charles Lennox Richardson (16 April 1834 – 14 September 1862) was a British merchant based in Shanghai who was killed in Japan during the Namamugi Incident. His middle name is spelled ''Lenox'' in census and family documents.

Merchant

Richardso ...

, for whose death the Tokugawa government had to pay an indemnity

In contract law, an indemnity is a contractual obligation of one party (the ''indemnitor'') to compensate the loss incurred by another party (the ''indemnitee'') due to the relevant acts of the indemnitor or any other party. The duty to indemni ...

of one hundred thousand British pounds

Sterling (abbreviation: stg; Other spelling styles, such as STG and Stg, are also seen. ISO code: GBP) is the currency of the United Kingdom and nine of its associated territories. The pound ( sign: £) is the main unit of sterling, and t ...

.Jansen, pp. 314–315. Other attacks included the shelling of foreign shipping in the port of Shimonoseki

is a city located in Yamaguchi Prefecture, Japan. With a population of 265,684, it is the largest city in Yamaguchi Prefecture and the fifth-largest city in the Chūgoku region. It is located at the southwestern tip of Honshu facing the Tsush ...

.Hagiwara, p. 35.

During 1864, these actions were successfully countered by armed retaliations by foreign powers, such as the British bombardment of Kagoshima

The Bombardment of Kagoshima, also known as the , was a military engagement fought between Britain and the Satsuma Domain in Kagoshima from 15 to 17 August 1863. The British were attempting to extract compensation and legal justice from ''daim ...

and the multinational Shimonoseki campaign. At the same time, the forces of Chōshū Domain, together with ''rōnin

A ''rōnin'' ( ; ja, 浪人, , meaning 'drifter' or 'wanderer') was a samurai without a lord or master during the feudal period of Japan (1185–1868). A samurai became masterless upon the death of his master or after the loss of his master ...

'', raised the Hamaguri rebellion trying to seize the city of Kyoto

Kyoto (; Japanese language, Japanese: , ''Kyōto'' ), officially , is the capital city of Kyoto Prefecture in Japan. Located in the Kansai region on the island of Honshu, Kyoto forms a part of the Keihanshin, Keihanshin metropolitan area along wi ...

, where the Emperor's court was, but were repelled by shogunate forces under the future ''shōgun

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamak ...

'' Tokugawa Yoshinobu. The shogunate further ordered a punitive expedition

A punitive expedition is a military journey undertaken to punish a political entity or any group of people outside the borders of the punishing state or union. It is usually undertaken in response to perceived disobedient or morally wrong beh ...

against Chōshū, the First Chōshū expedition

The First Chōshū expedition ( ja, 第一次長州征討) was a punitive military expedition by the Tokugawa shogunate against the Chōshū Domain in September–November 1864. The expedition was in retaliation for Chōshū's role in the attack ...

, and obtained Chōshū's submission without actual fighting. At this point the initial resistance among the leadership in Chōshū and the Imperial Court subsided, but over the next year the Tokugawa proved unable to reassert full control over the country as most ''daimyō

were powerful Japanese magnates, feudal lords who, from the 10th century to the early Meiji period in the middle 19th century, ruled most of Japan from their vast, hereditary land holdings. They were subordinate to the shogun and nominal ...

s'' began to ignore orders and questions from the Tokugawa seat of power in Edo.Jansen, pp. 303–305.

Foreign military assistance

Thomas Blake Glover

Thomas Blake Glover (6 June 1838 – 16 December 1911) was a Scottish merchant in the Bakumatsu and Meiji period in Japan.

Early life (1838–1858)

Thomas Blake Glover was born at 15 Commerce Street, Fraserburgh, Aberdeenshire in northeast Sco ...

sold quantities of warships and guns to the southern domains. American and British military experts, usually former officers, may have been directly involved in this military effort. The British ambassador, Harry Smith Parkes

Sir Harry Smith Parkes (24 February 1828 – 22 March 1885) was a British diplomat who served as Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary and Consul General of the United Kingdom to the Empire of Japan from 1865 to 1883 and the Chinese ...

, supported the anti-shogunate forces in a drive to establish a legitimate, unified Imperial rule in Japan, and to counter French influence with the shogunate. During that period, southern Japanese leaders such as Saigō Takamori

was a Japanese samurai and nobleman. He was one of the most influential samurai in Japanese history and one of the three great nobles who led the Meiji Restoration. Living during the late Edo and early Meiji periods, he later led the Satsum ...

of Satsuma, or Itō Hirobumi

was a Japanese politician and statesman who served as the first Prime Minister of Japan. He was also a leading member of the ''genrō'', a group of senior statesmen that dictated Japanese policy during the Meiji era.

A London-educated samu ...

and Inoue Kaoru

Marquess Inoue Kaoru (井上 馨, January 16, 1836 – September 1, 1915) was a Japanese politician and a prominent member of the Meiji oligarchy during the Meiji period of the Empire of Japan. As one of the senior statesmen ('' Genrō'') in J ...

of Chōshū cultivated personal connections with British diplomats, notably Ernest Mason Satow

Sir Ernest Mason Satow, (30 June 1843 – 26 August 1929), was a British scholar, diplomat and Japanologist.

Satow is better known in Japan than in Britain or the other countries in which he served, where he was known as . He was a key figu ...

. Satsuma domain received British assistance for their naval modernisation, and they became the second largest purchaser of western ships after the Shogunate itself, of which nearly all were British-built. As Satsuma samurai became dominant in the Imperial navy after the war, the navy frequently sought assistance from the British.Henny, et al, pp.173-174.

In preparation for future conflict, the shogunate also modernized its forces. In line with Parkes's strategy, the British, previously the shogunate's primary foreign partner, proved reluctant to provide assistance. The Tokugawa thus came to rely mainly on French expertise, comforted by the military prestige of Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

at that time, acquired through his successes in the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

and the Second Italian War of Independence

The Second Italian War of Independence, also called the Franco-Austrian War, the Austro-Sardinian War or Italian War of 1859 ( it, Seconda guerra d'indipendenza italiana; french: Campagne d'Italie), was fought by the Second French Empire and t ...

.

The shogunate took major steps towards the construction of a modern and powerful military: a navy with a core of eight steam warships had been built over several years and was already the strongest in Asia. In 1865, Japan's first modern naval arsenal was built in Yokosuka

is a city in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan.

, the city has a population of 409,478, and a population density of . The total area is . Yokosuka is the 11th most populous city in the Greater Tokyo Area, and the 12th in the Kantō region.

The city ...

by the French engineer Léonce Verny

François Léonce Verny, (2 December 1837 – 2 May 1908) was a French officer and naval engineerSims, Richard. (1998) ''French Policy Towards the Bakufu and Meiji Japan 1854-95: A Case of Misjudgement and Missed Opportunities,'' p. 246./ref> ...

. In January 1867, a French military mission arrived to reorganize the shogunate army and create the ''Denshūtai

The was a corps of elite troops of the Tokugawa Bakufu during the Bakumatsu period in Japan. The corps was founded by Ōtori Keisuke with the help of the 1867–68 French Military Mission to Japan.

The corps was composed of 800 men. They w ...

'' elite force, and an order was placed with the US to buy the French-built ironclad warship

An ironclad is a steam-propelled warship protected by iron or steel armor plates, constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships to explosive or incendiary shells. Th ...

CSS ''Stonewall'', which had been built for the Confederate States Navy

The Confederate States Navy (CSN) was the Navy, naval branch of the Confederate States Armed Forces, established by an act of the Confederate States Congress on February 21, 1861. It was responsible for Confederate naval operations during the Amer ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

. Due to the Western powers' declared neutrality, the US refused to release the ship, but once neutrality was lifted, the imperial faction obtained the vessel and employed it in engagements in Hakodate under the name ''Kōtetsu'' ("Ironclad").

Coups d'état

Following a

Following a coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

within Chōshū which returned to power the extremist factions opposed to the shogunate, the shogunate announced its intention to lead a Second Chōshū expedition

The Second Chōshū expedition (Japanese: 第二次長州征討), also called the Summer War, was a punitive expedition led by the Tokugawa shogunate against the Chōshū Domain. It followed the First Chōshū expedition of 1864.

Background

Th ...

to punish the renegade domain. This, in turn, prompted Chōshū to form a secret alliance with Satsuma. In the summer of 1866, the shogunate was defeated by Chōshū, leading to a considerable loss of authority. In late 1866, however, first ''shōgun'' Tokugawa Iemochi

(July 17, 1846 – August 29, 1866) was the 14th ''shōgun'' of the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan, who held office from 1858 to 1866.

During his reign there was much internal turmoil as a result of the "re-opening" of Japan to western nations. ...

and then Emperor Kōmei

was the 121st Emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession.Imperial Household Agency (''Kunaichō'')孝明天皇 (121)/ref> Kōmei's reign spanned the years from 1846 through 1867, corresponding to the final years of the ...

died, succeeded by Tokugawa Yoshinobu and Emperor Meiji respectively. These events, in the words of historian Marius Jansen

Marius Berthus Jansen (April 11, 1922 – December 10, 2000) was an American academic, historian, and Emeritus Professor of Japanese History at Princeton University.Princeton University, Office of Communications"Professor Marius Berthus Jansen, sc ...

, "made a truce inevitable".Jansen, p. 307.

On November 9, 1867, a secret order was created by Satsuma and Chōshū in the name of Emperor Meiji commanding the "slaughtering of the traitorous subject Yoshinobu". Just prior to this, however—and following a proposal from the ''daimyō'' of the Tosa Domain

The was a feudal domain under the Tokugawa shogunate of Edo period Japan, controlling all of Tosa Province in what is now Kōchi Prefecture on the island of Shikoku. It was centered around Kōchi Castle, and was ruled throughout its history by ...

—Yoshinobu resigned his post and authority to the emperor, agreeing to "be the instrument for carrying out" imperial orders.Satow, p. 282. This ended the Tokugawa shogunate.Keene, p. 116.Jansen, pp. 310–311.

While Yoshinobu's resignation had created a nominal void at the highest level of government, his apparatus of state continued to exist. Moreover, the shogunate government, the Tokugawa family in particular, remained a prominent force in the evolving political order and retained many executive powers.Keene, pp. 120–121.Satow, p. 283. Moreover, Satow speculates that Yoshinobu had agreed to an assembly of ''daimyōs'' on the hope that such a body would restore him,Satow, p. 285. a prospect hard-liners from Satsuma and Chōshū found intolerable.Satow, p. 286. Events came to a head on January 3, 1868, when these elements seized the imperial palace in Kyoto, and the following day had the fifteen-year-old Emperor Meiji declare his own restoration to full power. Although the majority of the imperial consultative assembly representing all the domains was happy with the formal declaration of direct rule by the imperial court and tended to support a continued collaboration with the Tokugawa (under the concept of ), Saigō Takamori

was a Japanese samurai and nobleman. He was one of the most influential samurai in Japanese history and one of the three great nobles who led the Meiji Restoration. Living during the late Edo and early Meiji periods, he later led the Satsum ...

threatened the assembly into abolishing the title "''shōgun''" and ordering the confiscation of Yoshinobu's lands.

Although he initially agreed to these demands, on January 17, 1868, Yoshinobu declared that he would not be bound by the Restoration proclamation and called for its repeal.Keene, p. 124. On January 24, he decided to prepare an attack on Kyoto, which was occupied by Satsuma and Chōshū forces. This decision was prompted by his learning of a series of arsons in Edo, starting with the burning of the outer works of Edo Castle, the main Tokugawa residence. This was blamed on Satsuma ''rōnin'', who on that day attacked a government office. The next day shogunate forces responded by attacking the Edo residence of the ''daimyō'' of Satsuma, where many opponents of the shogunate, under Saigo's direction, had been hiding and creating trouble. The residence was burned down, and many opponents killed or later executed.Keene, p. 125.

Weapons and uniforms

The forces of Chōshū and Satsuma were fully modernized withArmstrong Gun

An Armstrong gun was a uniquely designed type of rifled breech-loading field and heavy gun designed by Sir William Armstrong and manufactured in England beginning in 1855 by the Elswick Ordnance Company and the Royal Arsenal at Woolwich. Such g ...

s, Minié rifle

The Minié rifle was an important infantry rifle of the mid-19th century. A version was adopted in 1849 following the invention of the Minié ball in 1847 by the French Army captain Claude-Étienne Minié of the Chasseurs d'Orléans and Henr ...

s and one Gatling gun.Esposito, pp. 40–41. The shogunate forces had been slightly lagging in terms of equipment, although the French military mission had recently trained a core elite force.Esposito, pp. 23–34. The ''shōgun'' also relied on troops supplied by allied domains, which were not necessarily as advanced in terms of military equipment and methods, composing an army that had both modern and outdated elements.Ravina (2005), pp. 149-160.

Individual guns

Numerous types of more or less modern

Numerous types of more or less modern smoothbore

A smoothbore weapon is one that has a barrel without rifling. Smoothbores range from handheld firearms to powerful tank guns and large artillery mortars.

History

Early firearms had smoothly bored barrels that fired projectiles without signi ...

muskets and rifles were imported, from countries as varied as France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

, and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

, and coexisted with traditional types such as the ''tanegashima'' matchlock. Most shogunate troops used smoothbore muskets, about 200,000 of which had been imported into Japan over the years since around 1600.

The first modern firearms were initially imported about 1840 from the Netherlands by the pro-Western reformist Takashima Shūhan

was a samurai and military engineer in Bakumatsu period Japan. He is significant in having started to import flintlock guns from the Netherlands at the end of Japan's period of Seclusion, during the Late Tokugawa Shogunate.Jansen, Marius. (20 ...

.Jansen, p. 288. The ''daimyō'' of Nagaoka Domain

was a '' fudai'' feudal domain under the Tokugawa shogunate of Edo period Japan. It is located in Echigo Province, Honshū. The domain was centered at Nagaoka Castle, located in what is now part of the city of Nagaoka in Niigata Prefecture ...

, however, an ally of the ''shōgun'', possessed two Gatling guns and several thousand modern rifles.Esposito, p. 10. The shogunate is known to have placed an order for 30,000 modern Dreyse needle gun Dreyse may refer to:

* Johann Nicolaus von Dreyse (1787–1867), German firearms inventor

* Hitch Dreyse, a fictional character in ''Attack on Titan'' (''Shingeki no Kyojin'') series who serves in the military police.

* Dreyse needle gun, a German ...

s in 1866. Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

provided Yoshinobu with 2,000 state-of-the-art Chassepot

The Chassepot (pronounced ''SHAS-poh''), officially known as ''Fusil modèle 1866'', was a bolt-action military breechloading rifle. It is famous for having been the arm of the French forces in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871. It repla ...

rifles, which he used to equip his personal guard. Antiquated ''tanegashima'' matchlocks are also known to have been used by the shogunate, however.Ryozen Museum of History

The is a history museum located in Kyoto, Japan. It specializes in the history of the Bakumatsu period and the Meiji Restoration.

The Museum is next to the Kyoto Ryozen Gokoku Shrine

The is a Shinto Shrine located in Kyoto, Japan. It ho ...

exhibit.

Imperial troops mainly used Minié rifles, which were much more accurate, lethal, and had a much longer range than the imported smoothbore muskets, although, being also muzzle-loading, they were similarly limited to two shots per minute. Improved breech-loading mechanisms, such as the Snider Snider may refer to:

Places

;United States

* Snider, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

* Sniderville, Wisconsin, an unincorporated community

Other uses

* Snider (surname)

*Snider–Enfield, a firearm

See also

*Snyder (disambiguation)

*Sc ...

, developing a rate of about ten shots a minute, are known to have been used by Chōshū troops against the shogunate's Shōgitai

The Shōgitai (, "Manifest Righteousness Regiment") was an elite samurai shock infantry formation of the Tokugawa shogunate military formed in 1868 by the hatamoto and Hitotsubashi Gosankyō retainer in Zōshigaya, Edo (now Tokyo). The Shōg ...

regiment at the Battle of Ueno in July 1868. In the second half of the conflict, in the northeast theater, Tosa troops are known to have used American-made Spencer repeating rifle

The Spencer repeating rifles and carbines were 19th-century American lever-action firearms invented by Christopher Spencer. The Spencer was the world's first military metallic-cartridge repeating rifle, and over 200,000 examples were manufacture ...

s. American-made handguns were also popular, such as the 1863 Smith & Wesson Army No 2, which was imported to Japan by Glover and used by Satsuma forces.

Artillery

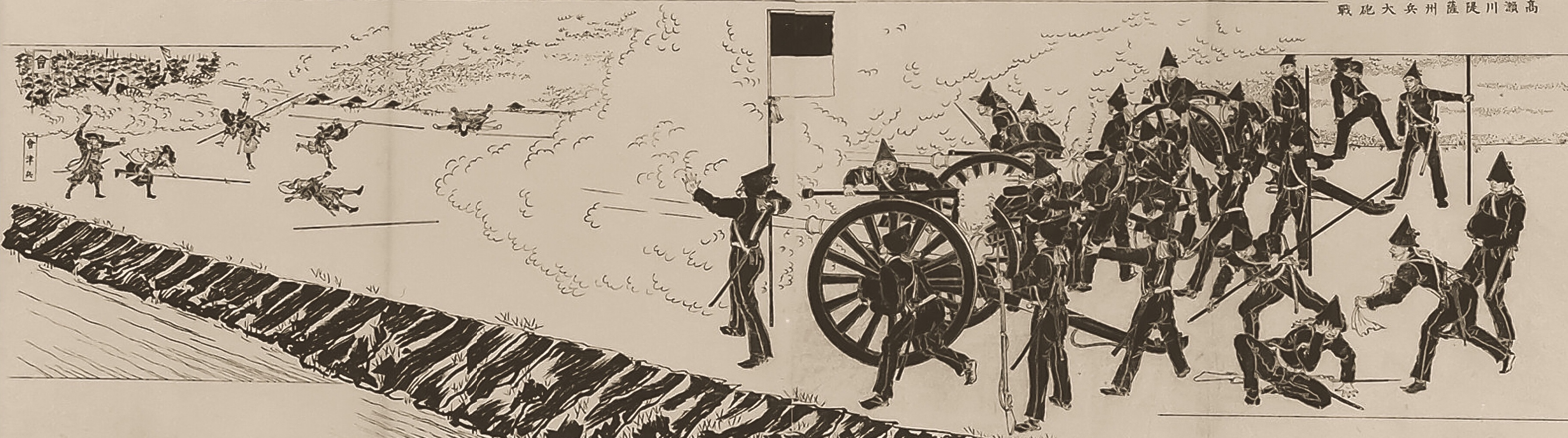

For artillery,

For artillery, wooden cannon

Wooden cannons have been manufactured and used in wars in many countries. The wooden parts were invariably strengthened with metal fittings or even rope.

Expedient technique

The use of wood for cannon-making could be dictated either by the lack ...

s, only able to fire 3 or 4 shots before bursting, coexisted with state-of-the-art Armstrong gun

An Armstrong gun was a uniquely designed type of rifled breech-loading field and heavy gun designed by Sir William Armstrong and manufactured in England beginning in 1855 by the Elswick Ordnance Company and the Royal Arsenal at Woolwich. Such g ...

s using explosive shells. Armstrong guns were efficiently used by Satsuma and Saga troops throughout the war.

The Shogunate as well as the Imperial side also used native Japanese cannons, with Japan making cannons domestically as far back as 1575.Perrin, p. 19.

Warships

In the area of warships also, some of the most recent ironclads such as the ''Kōtetsu'' coexisted with older types of steamboats and even traditional sailboats. The shogunate initially had the edge in warships, and it had the vision to buy the ''Kōtetsu''. The ship was blocked from delivery by foreign powers on grounds of neutrality once the conflict had started, and was ultimately delivered to the Imperial faction shortly after the Battle of Toba–Fushimi.Keene, pp. 165–166.Uniforms

Uniforms were Western-style for modernized troops (usually dark, with variations in the shape of the helmet: tall conical for Satsuma, flat conical for Chōshū, rounded for the shogunate).Esposito, pp. 17–23. Officers of the shogunate often wore French and British uniforms. Traditional troops however retained theirsamurai

were the hereditary military nobility and officer caste of medieval and early-modern Japan from the late 12th century until their abolition in 1876. They were the well-paid retainers of the '' daimyo'' (the great feudal landholders). They h ...

clothes. Some of the Imperial troops wore peculiar headgear, involving the use of long, colored, "bear" hair. The wigs indicated officers from Tosa, the wigs officers from Chōshū, and the "black bear" (黒熊, ''koguma'') wigs officers from Satsuma.Gonick, p. 25.

Opening conflicts

On January 27, 1868, shogunate forces attacked the forces of Chōshū and Satsuma, clashing near Toba and Fushimi, at the southern entrance to Kyoto in the Battle of Toba–Fushimi. Some parts of the 15,000-strong shogunate forces had been trained by French military advisers. Among their numbers during this battle were the noted ''

On January 27, 1868, shogunate forces attacked the forces of Chōshū and Satsuma, clashing near Toba and Fushimi, at the southern entrance to Kyoto in the Battle of Toba–Fushimi. Some parts of the 15,000-strong shogunate forces had been trained by French military advisers. Among their numbers during this battle were the noted ''Shinsengumi

The was a special police force organized by the (military government) during Japan's Bakumatsu period (late Tokugawa shogunate) in 1863. It was active until 1869. It was founded to protect the shogunate representatives in Kyoto at a time wh ...

''.Vaporis, p. 33. The forces of Chōshū and Satsuma were outnumbered 3:1 but fully modernized with Armstrong howitzers, Minié rifles and a few Gatling guns.

After an inconclusive start, an Imperial banner was presented to the defending troops on the second day, and a relative of the Emperor, Ninnajinomiya Yoshiaki, was named nominal commander in chief, making the forces officially an . Moreover, convinced by courtiers, several local ''daimyōs'', up to this point faithful to the ''shōgun'', started to defect to the side of the Imperial Court. These included the ''daimyōs'' of Yodo and Tsu in February, tilting the military balance in favour of the Imperial side.

After the defections, Yoshinobu, apparently distressed by the imperial approval given to the actions of Satsuma and Chōshū, fled

After the defections, Yoshinobu, apparently distressed by the imperial approval given to the actions of Satsuma and Chōshū, fled Osaka

is a designated city in the Kansai region of Honshu in Japan. It is the capital of and most populous city in Osaka Prefecture, and the third most populous city in Japan, following Special wards of Tokyo and Yokohama. With a population of ...

aboard the , withdrawing to Edo. Demoralized by his flight and by the betrayal by Yodo and Tsu, shogunate forces retreated, resulting in an Imperial victory, although it is often considered the shogunate forces should have won the encounter. Osaka Castle

is a Japanese castle in Chūō-ku, Osaka, Japan. The castle is one of Japan's most famous landmarks and it played a major role in the unification of Japan during the sixteenth century of the Azuchi-Momoyama period.

Layout

The main tower ...

was soon invested on March 1 (February 8 in the Tenpō calendar), putting an end to the battle.Hagiwara, pp. 43–45.

The day after the battle of Toba–Fushimi commenced, the naval Battle of Awa took place between the shogunate and elements of the Satsuma navy in Awa Bay near Osaka. This was Japan's second engagement between two modern navies.Togo (1993). The battle, although small in scale, ended with a victory for the shogunate.Tucker, p. 274.

On the diplomatic front, the ministers of foreign nations, gathered in the open harbour of Hyōgo (present day Kobe) in early February, issued a declaration according to which the shogunate was still considered the only rightful government in Japan, giving hope to Tokugawa Yoshinobu that foreign nations (especially France) might consider an intervention in his favour. A few days later however an Imperial delegation visited the ministers declaring that the shogunate was abolished, that harbours would be open in accordance with International treaties, and that foreigners would be protected. The ministers finally decided to recognize the new government.Polak, p. 75.

The rise of anti-foreign sentiment nonetheless led to several attacks on foreigners in the following months. Eleven French sailors from the corvette ''Dupleix'' were killed by samurai of Tosa in the Sakai incident

270px, Monument to the Tosa samurai at Myōkoku-ji in Sakai

The was a diplomatic incident that occurred on March 8, 1868, in Bakumatsu period Japan involving the deaths of eleven French sailors from the French corvette ''Dupleix'' in the port ...

on March 8, 1868. Fifteen days later, Sir Harry Parkes, the British ambassador, was attacked by a group of samurai in a street of Kyoto.

Surrender of Edo

Beginning in February, with the help of the French ambassador

Beginning in February, with the help of the French ambassador Léon Roches

Léon Roches (September 27, 1809, Grenoble – 1901) was a representative of the French government in Japan from 1864 to 1868.

Léon Roches was a student at the Lycée de Tournon in Grenoble, and followed an education in Law. After only 6 mo ...

, a plan was formulated to stop the Imperial Court's advance at Odawara

is a city in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 188,482 and a population density of 1,700 persons per km2. The total area of the city is .

Geography

Odawara lies in the Ashigara Plains, in the far western por ...

, the last strategic entry point to Edo, but Yoshinobu decided against the plan. Shocked, Léon Roches resigned from his position. In early March, under the influence of the British minister Harry Parkes, foreign nations signed a strict neutrality agreement, according to which they could not intervene or provide military supplies to either side until the resolution of the conflict.Polak, p. 77.

Saigō Takamori

was a Japanese samurai and nobleman. He was one of the most influential samurai in Japanese history and one of the three great nobles who led the Meiji Restoration. Living during the late Edo and early Meiji periods, he later led the Satsum ...

led the victorious imperial forces north and east through Japan, winning the Battle of Kōshū-Katsunuma

The was a battle between pro-Imperial and Tokugawa shogunate forces during the Boshin War in Japan. The battle followed the Battle of Toba–Fushimi on 29 March 1868 (Gregorian calendar).

Prelude

After defeating the forces of the Tokugawa sho ...

. He eventually surrounded Edo in May 1868, leading to its unconditional defeat after Katsu Kaishū

Count , best known by his nickname , was a Japanese statesman and naval engineer during the late Tokugawa shogunate and early Meiji period. Kaishū was a nickname which he took from a piece of calligraphy (Kaishū Shooku ) by Sakuma Shōzan. He ...

, the ''shōgun''s Army Minister, negotiated the surrender.Hagiwara, p. 46. Some groups continued to resist after this surrender but were defeated in the Battle of Ueno on July 4, 1868.Perez, p. 32.

Meanwhile, the leader of the ''shōgun''s navy, Enomoto Takeaki, refused to surrender all his ships. He remitted just four ships, among them the ''Fujiyama'', but he then escaped north with the remnants of the ''shōgun''s navy (eight steam warships: ''Kaiten'', ''Banryū'', ''Chiyodagata'', ''Chōgei'', ''Kaiyō Maru'', ''Kanrin Maru'', ''Mikaho'' and ''Shinsoku''), and 2,000 personnel, in the hope of staging a counter-attack together with the northern ''daimyōs''. He was accompanied by a handful of French military advisers, notably Jules Brunet

Jules Brunet (2 January 1838 – 12 August 1911) was a French military officer who served the Tokugawa shogunate during the Boshin War in Japan. Originally sent to Japan as an artillery instructor with the French military mission of 1867, he refu ...

, who had formally resigned from the French Army to accompany the rebels.

Resistance of the Northern Coalition

After Yoshinobu's surrender, he was placed under house arrest, and stripped of all titles, land and power. He was later released, when he demonstrated no further interest and ambition in national affairs. He retired to

After Yoshinobu's surrender, he was placed under house arrest, and stripped of all titles, land and power. He was later released, when he demonstrated no further interest and ambition in national affairs. He retired to Shizuoka

Shizuoka can refer to:

* Shizuoka Prefecture, a Japanese prefecture

* Shizuoka (city), the capital city of Shizuoka Prefecture

* Shizuoka Airport

* Shizuoka Domain, the name from 1868 to 1871 for Sunpu Domain, a predecessor of Shizuoka Prefecture

...

, the place to which his ancestor Tokugawa Ieyasu

was the founder and first ''shōgun'' of the Tokugawa Shogunate of Japan, which ruled Japan from 1603 until the Meiji Restoration in 1868. He was one of the three "Great Unifiers" of Japan, along with his former lord Oda Nobunaga and fello ...

had also retired. Most of Japan accepted the emperor's rule, but a core of domains in the North, supporting the Aizu clan, continued the resistance.Bolitho, p. 246.Black, p. 214. In May, several northern ''daimyō

were powerful Japanese magnates, feudal lords who, from the 10th century to the early Meiji period in the middle 19th century, ruled most of Japan from their vast, hereditary land holdings. They were subordinate to the shogun and nominal ...

s'' formed an Alliance to fight Imperial troops, the coalition of northern domains composed primarily of forces from the domains of Sendai, Yonezawa

Yonezawa City Hall

is a city in Yamagata Prefecture, Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 81,707 in 33,278 households, and a population density of 150 persons per km2. The total area of the city is . Yonezawa is most famous for ...

, Aizu, Shōnai and Nagaoka, with a total of 50,000 troops.Polak, pp. 79–91. Apart from those core domains, most of the northern domains were part of the alliance.

In May 1868, the ''daimyō'' of Nagaoka inflicted high losses on the Imperial troops in the Battle of Hokuetsu

The was a battle of the Boshin War of the Meiji Restoration, which occurred in 1868 in the northwestern part of Japan, in the area of modern Niigata Prefecture.

Background

The Boshin War erupted in 1868 between troops favourable to the resto ...

, but his castle ultimately fell on May 19. Imperial troops continued to progress north, defeating the Shinsengumi

The was a special police force organized by the (military government) during Japan's Bakumatsu period (late Tokugawa shogunate) in 1863. It was active until 1869. It was founded to protect the shogunate representatives in Kyoto at a time wh ...

at the Battle of Bonari Pass, which opened the way for their attack on the castle of Aizuwakamatsu

is a city in Fukushima Prefecture, Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 118,159 in 50,365 households, and a population density of 310 persons per km2. The total area of the city was .

Geography

Aizuwakamatsu is located in the west ...

in the Battle of Aizu in October 1868, thus making the position in Sendai untenable.Turnbull, pp. 153–58.

cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

s made of wood and reinforced with roping, firing stone projectiles. Such cannons, installed on defensive structures, could only fire four or five projectiles before bursting. On the other hand, the ''daimyō'' of Nagaoka managed to procure two of the three Gatling guns in Japan and 2,000 modern French rifles from the German weapons dealer Henry Schnell

Edward Schnell (June 3, 1830 - August 22, 1911) and Henry Schnell (August 4, 1834 - October 15, 1917) were brothers of Dutch extraction and German arms dealers active in Japan. After the enforced opening of Yokohama to foreign trade, Edward, who ...

.Vaporis, p. 35.

The coalition crumbled, and on October 12, 1868, the fleet left Sendai for Hokkaidō, after having acquired two more ships (''Oe'' and ''Hōō'', previously borrowed by Sendai from the shogunate), and about 1,000 more troops: remaining shogunate troops under Ōtori Keisuke

was a Japanese military leader and diplomat.Perez, Louis G. (2013)"Ōtori Keisuke"in ''Japan at War: An Encyclopedia,'' p. 304.

Biography

Early life and education

Ōtori Keisuke was born in Akamatsu Village, in the Akō domain of Harima Pro ...

, Shinsengumi

The was a special police force organized by the (military government) during Japan's Bakumatsu period (late Tokugawa shogunate) in 1863. It was active until 1869. It was founded to protect the shogunate representatives in Kyoto at a time wh ...

troops under Hijikata Toshizō, the guerilla corps (''yugekitai'') under Hitomi Katsutarō Hitomi may refer to:.

People

* Hitomi (given name), a feminine Japanese given name

* Hitomi (voice actress) (born 1967), Japanese voice actress

* Hitomi (singer) (born 1976, as Hitomi Furuya), Japanese singer and songwriter

* Hitomi Nabatame (b ...

, as well as several more French advisers (Fortant, Garde, Marlin, Bouffier).

On October 26, Edo was renamed Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and List of cities in Japan, largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, ...

, and the Meiji period

The is an era of Japanese history that extended from October 23, 1868 to July 30, 1912.

The Meiji era was the first half of the Empire of Japan, when the Japanese people moved from being an isolated feudal society at risk of colonization ...

officially started. Aizu was besieged starting that month, leading to the mass suicide of the ''Byakkotai

The was a group of around 305 young teenage samurai of the Aizu Domain, who fought in the Boshin War (1868–1869) on the side of the Tokugawa shogunate.

History

The Byakkotai was part of Aizu's four-unit military, formed in April 1868 in the ...

'' (White Tiger Corps) young warriors. After a protracted month-long battle, Aizu finally admitted defeat on November 6.Turnbull, p. 11.

Hokkaidō campaign

Creation of the Ezo Republic

Republic of Ezo

The was a short-lived separatist state established in 1869 on the island of Ezo, now Hokkaido, by a part of the former military of the Tokugawa shogunate at the end of the ''Bakumatsu'' period in Japan. It was the first government to attempt t ...

on the American model, Japan's only ever republic, and Enomoto was elected as president, with a large majority. The republic tried to reach out to foreign legations present in Hakodate, such as the Americans, French, and Russians

, native_name_lang = ru

, image =

, caption =

, population =

, popplace =

118 million Russians in the Russian Federation (2002 '' Winkler Prins'' estimate)

, region1 =

, pop1 ...

, but was not able to garner any international recognition or support. Enomoto offered to confer the territory to the Tokugawa ''shōgun'' under Imperial rule, but his proposal was declined by the Imperial Governing Council.

During the winter, they fortified their defenses around the southern peninsula of Hakodate

is a city and port located in Oshima Subprefecture, Hokkaido, Japan. It is the capital city of Oshima Subprefecture. As of July 31, 2011, the city has an estimated population of 279,851 with 143,221 households, and a population density of 412.8 ...

, with the new fortress of Goryōkaku at the center. The troops were organized under a Franco-Japanese command, the commander-in-chief Ōtori Keisuke

was a Japanese military leader and diplomat.Perez, Louis G. (2013)"Ōtori Keisuke"in ''Japan at War: An Encyclopedia,'' p. 304.

Biography

Early life and education

Ōtori Keisuke was born in Akamatsu Village, in the Akō domain of Harima Pro ...

being seconded by the French captain Jules Brunet

Jules Brunet (2 January 1838 – 12 August 1911) was a French military officer who served the Tokugawa shogunate during the Boshin War in Japan. Originally sent to Japan as an artillery instructor with the French military mission of 1867, he refu ...

, and divided between four brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute a division.

B ...

s. Each of these was commanded by a French non-commissioned officer ( Fortant, Marlin

Marlins are fish from the family Istiophoridae, which includes about 10 species. A marlin has an elongated body, a spear-like snout or bill, and a long, rigid dorsal fin which extends forward to form a crest. Its common name is thought to deri ...

, Cazeneuve Cazeneuve may refer to:

People

*André Cazeneuve (died 1874), French soldier in Japanese service

*Bernard Cazeneuve (born 1963), French prime minister

* Jean Cazeneuve (1915–2005), French sociologist and anthropologist.

* Louis Cazeneuve (1 ...

, Bouffier), and were themselves divided into eight half-brigades, each under Japanese command.Polak, pp. 85–89.

Final losses and surrender

The Imperial Navy reached the harbour of Miyako on March 20, but anticipating the arrival of the Imperial ships, the Ezo rebels organized a daring plan to seize the ''Kōtetsu''. Led by Shinsengumi commander Hijikata Toshizō, three warships were dispatched for a surprise attack, in what is known as the Battle of Miyako Bay. The battle ended in failure for the Tokugawa side, owing to bad weather, engine trouble and the decisive use of a Gatling gun by Imperial troops against samurai boarding parties.

Imperial forces soon consolidated their hold on mainland Japan, and, in April 1869, dispatched a fleet and an infantry force of 7,000 to Ezo, starting the

The Imperial Navy reached the harbour of Miyako on March 20, but anticipating the arrival of the Imperial ships, the Ezo rebels organized a daring plan to seize the ''Kōtetsu''. Led by Shinsengumi commander Hijikata Toshizō, three warships were dispatched for a surprise attack, in what is known as the Battle of Miyako Bay. The battle ended in failure for the Tokugawa side, owing to bad weather, engine trouble and the decisive use of a Gatling gun by Imperial troops against samurai boarding parties.

Imperial forces soon consolidated their hold on mainland Japan, and, in April 1869, dispatched a fleet and an infantry force of 7,000 to Ezo, starting the Battle of Hakodate

The was fought in Japan from December 4, 1868 to June 27, 1869, between the remnants of the Tokugawa shogunate army, consolidated into the armed forces of the rebel Ezo Republic, and the armies of the newly formed Imperial government (composed ...

. The Imperial forces progressed swiftly and won the naval engagement at Hakodate Bay, Japan's first large-scale naval battle between modern navies, and the fortress of Goryōkaku was surrounded. Seeing the situation had become desperate, the French advisers escaped to a French ship stationed in Hakodate Bay'' Coëtlogon'', under the command of Abel-Nicolas Bergasse du Petit-Thouars

Abel-Nicolas Georges Henri Bergasse du Petit-Thouars (March 23, 1832 – March 14, 1890) was a French sailor and vice-admiral who took part in the Crimean War, the Boshin War, the Franco-Prussian War and the War of the Pacific. He is considered a ...

from where they were shipped back to Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of T ...

and then France. The Japanese requested that the French advisers be given judgement in France; however, due to popular support in France for their actions, the former French advisers were not punished for their actions.

Invited to surrender, Enomoto at first refused, and sent the Naval Codes he had brought back from Holland to the general of the Imperial troops, Kuroda Kiyotaka

Count , also known as , was a Japanese politician of the Meiji era. He was Prime Minister of Japan from 1888 to 1889. He was also vice chairman of the Hokkaido Development Commission ( Kaitaku-shi).

Biography

As a Satsuma ''samurai''

Ku ...

, to prevent their loss. Ōtori Keisuke

was a Japanese military leader and diplomat.Perez, Louis G. (2013)"Ōtori Keisuke"in ''Japan at War: An Encyclopedia,'' p. 304.

Biography

Early life and education

Ōtori Keisuke was born in Akamatsu Village, in the Akō domain of Harima Pro ...

convinced him to surrender, telling him that deciding to live through defeat is the truly courageous way: "Dying is easy; you can do that anytime."Perez, p. 84. Enomoto surrendered on June 27, 1869, accepting Emperor Meiji's rule, and the Ezo Republic ceased to exist.Onodera, p.196.

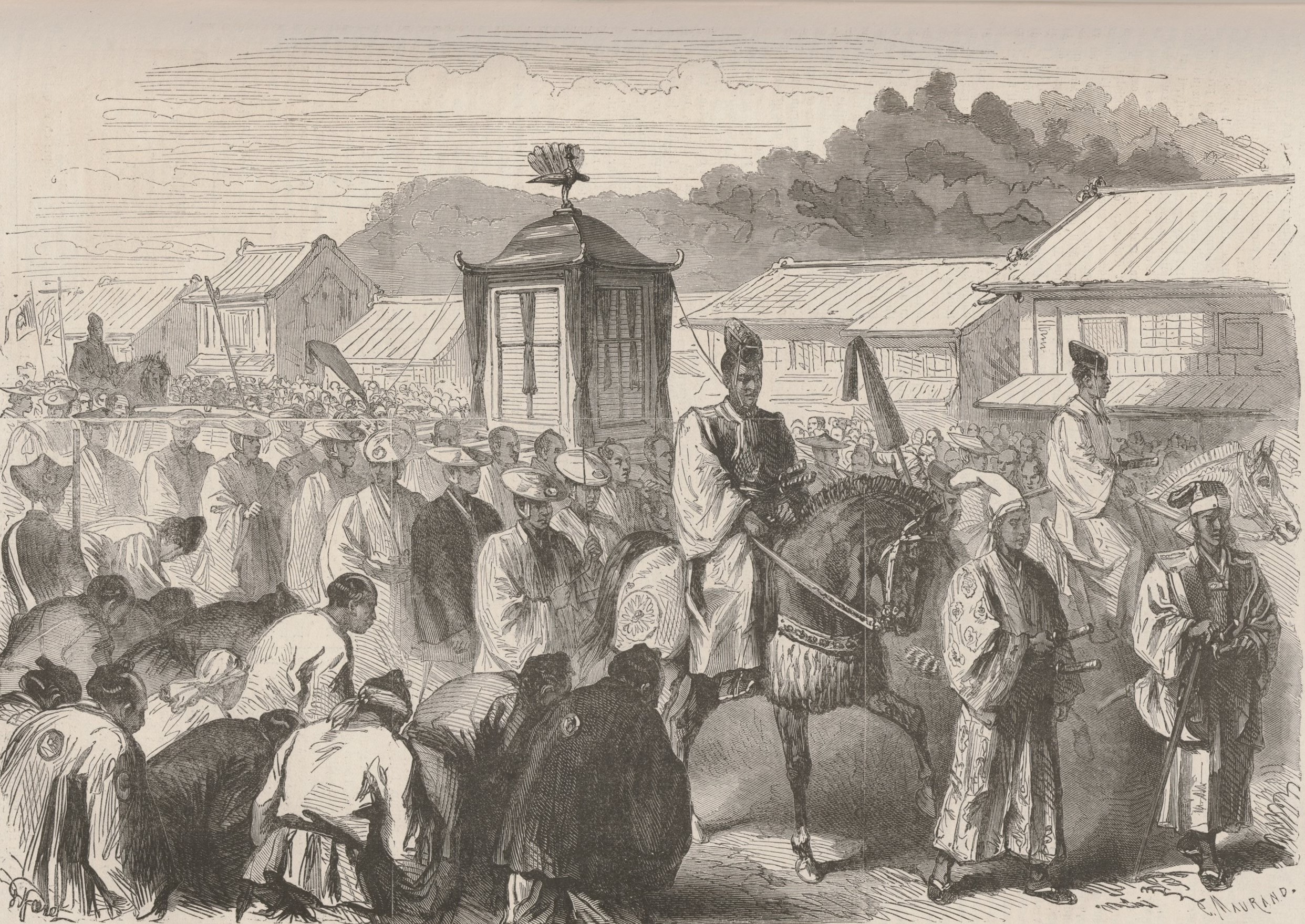

Aftermath

Of the approximately 120,000 men mobilized over the course of the conflict, about 8,200 were killed and more than 5,000 were wounded. Following victory, the new government proceeded with unifying the country under a single, legitimate and powerful rule by the Imperial Court. The emperor's residence was effectively transferred from

Of the approximately 120,000 men mobilized over the course of the conflict, about 8,200 were killed and more than 5,000 were wounded. Following victory, the new government proceeded with unifying the country under a single, legitimate and powerful rule by the Imperial Court. The emperor's residence was effectively transferred from Kyoto

Kyoto (; Japanese language, Japanese: , ''Kyōto'' ), officially , is the capital city of Kyoto Prefecture in Japan. Located in the Kansai region on the island of Honshu, Kyoto forms a part of the Keihanshin, Keihanshin metropolitan area along wi ...

to Edo at the end of 1868, and the city renamed to Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and List of cities in Japan, largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, ...

. The military and political power of the domains was progressively eliminated, and the domains themselves were transformed in 1871 into prefectures

A prefecture (from the Latin ''Praefectura'') is an administrative jurisdiction traditionally governed by an appointed prefect. This can be a regional or local government subdivision in various countries, or a subdivision in certain international ...

, whose governors were appointed by the emperor.Gordon, pp. 64–65.

A major reform was the effective expropriation and abolition of the samurai class, allowing many samurai to change into administrative or entrepreneurial positions, but forcing many others into poverty. The southern domains of Satsuma, Chōshū and Tosa, having played a decisive role in the victory, occupied most of the key posts in government for several decades following the conflict, a situation sometimes called the "Meiji oligarchy

The Meiji oligarchy was the new ruling class of Meiji period Japan. In Japanese, the Meiji oligarchy is called the .

The members of this class were adherents of ''kokugaku'' and believed they were the creators of a new order as grand as that est ...

" and formalized with the institution of the genrō

was an unofficial designation given to certain retired elder Japanese statesmen who served as informal extraconstitutional advisors to the emperor, during the Meiji, Taishō, and Shōwa eras in Japanese history.

The institution of ''genrō ...

. In 1869, the Yasukuni Shrine

is a Shinto shrine located in Chiyoda, Tokyo. It was founded by Emperor Meiji in June 1869 and commemorates those who died in service of Japan, from the Boshin War of 1868–1869, to the two Sino-Japanese Wars, 1894–1895 and 1937–1945 resp ...

in Tokyo was built in honor of the victims of the Boshin War.

Some leading partisans of the former ''shōgun'' were imprisoned, but narrowly escaped execution. This clemency derives from the insistence of Saigō Takamori and Iwakura Tomomi

was a Japanese statesman during the Bakumatsu and Meiji period. He was one of the leading figures of the Meiji Restoration, which saw Japan's transition from feudalism to modernity.

Born to a noble family, he was adopted by the influential Iwa ...

, although much weight was placed on the advice of Parkes Parkes may refer to:

* Sir Henry Parkes (1815–1896), Australian politician, one of the earliest and most prominent advocates for Australian federation

Named for Henry Parkes

* Parkes, New South Wales, a regional town

* Parkes Observatory, a radi ...

, the British envoy. He had urged Saigō, in the words of Ernest Satow, "that severity towards Keiki oshinobuor his supporters, especially in the way of personal punishment, would injure the reputation of the new government in the opinion of European Powers".Keene, p. 143. After two or three years of imprisonment, most of them were called to serve the new government, and several pursued brilliant careers. Enomoto Takeaki, for instance, would later serve as an envoy to Russia and China and as the education minister.Iguro, p. 559.Keene, pp. 204, 399, 434.

The Imperial side did not pursue its objective of expelling foreign interests from Japan, but instead shifted to a more progressive policy aiming at the continued modernization of the country and the renegotiation of

The Imperial side did not pursue its objective of expelling foreign interests from Japan, but instead shifted to a more progressive policy aiming at the continued modernization of the country and the renegotiation of unequal treaties

Unequal treaty is the name given by the Chinese to a series of treaties signed during the 19th and early 20th centuries, between China (mostly referring to the Qing dynasty) and various Western powers (specifically the British Empire, France, the ...

with foreign powers, later under the motto.Keene, pp. 206–209.

The shift in stance towards foreigners came during the early days of the civil war: on April 8, 1868, new signboards were erected in Kyoto (and later throughout the country) that specifically repudiated violence against foreigners.Keene, p. 142. During the course of the conflict, Emperor Meiji personally received European envoys, first in Kyoto, then later in Osaka and Tokyo.Keene, pp. 143–144, 165. Also unprecedented was Emperor Meiji's reception of Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh

Alfred (Alfred Ernest Albert; 6 August 184430 July 1900) was the sovereign duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha from 1893 to 1900. He was the second son and fourth child of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. He was known as the Duke of Edinburgh from 1 ...

, in Tokyo, "as his ''equal'' in point of blood".Parkes, quoted in Keene, pp. 183–187. Emphasis in the original.

Although the early Meiji era witnessed a warming of relations between the Imperial Court and foreign powers, relations with France temporarily soured due to the initial support by France for the ''shōgun''. Soon, however, a second military mission was invited to Japan in 1874, and a third one in 1884. A high level of interaction resumed around 1886, when France helped build the Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrend ...

's first large-scale modern fleet, under the direction of naval engineer Louis-Émile Bertin

Louis-Émile Bertin (23 March 1840 – 22 October 1924) was a French naval engineer, one of the foremost of his time, and a proponent of the " Jeune École" philosophy of using light, but powerfully armed warships instead of large battleships.

...

.Evans and Peattie, p. 15. The modernization of the country had started during the last years of the shogunate, and the Meiji government ultimately adopted the same policy.Takada (1990).Furukawa (1995).

Upon his coronation, Meiji issued his Charter Oath, calling for deliberative assemblies, promising increased opportunities for the common people, abolishing the "evil customs of the past", and seeking knowledge throughout the world "to strengthen the foundations of imperial rule".Jansen, p. 338. The reforms culminated in the 1889 issuance of the

Upon his coronation, Meiji issued his Charter Oath, calling for deliberative assemblies, promising increased opportunities for the common people, abolishing the "evil customs of the past", and seeking knowledge throughout the world "to strengthen the foundations of imperial rule".Jansen, p. 338. The reforms culminated in the 1889 issuance of the Meiji Constitution

The Constitution of the Empire of Japan (Kyūjitai: ; Shinjitai: , ), known informally as the Meiji Constitution (, ''Meiji Kenpō''), was the constitution of the Empire of Japan which was proclaimed on February 11, 1889, and remained in for ...

. However, despite the support given to the Imperial Court by samurai, many of the early Meiji reforms were seen as detrimental to their interests. The creation of a conscript army made of commoners, as well as the loss of hereditary prestige and stipends, antagonized many former samurai.Jansen, pp. 367–368. Tensions ran particularly high in the south, leading to the 1874 Saga Rebellion

The was an 1874 uprising in Kyūshū against the new Meiji government of Japan.Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "Saga no ran" in . It was led by Etō Shinpei and Shima Yoshitake in their native domain of Hizen.

Background

Following the 18 ...

, and a rebellion in Chōshū in 1876. Former samurai in Satsuma, led by Saigō Takamori, who had left government over foreign policy differences, started the Satsuma Rebellion

The Satsuma Rebellion, also known as the was a revolt of disaffected samurai against the new imperial government, nine years into the Meiji Era. Its name comes from the Satsuma Domain, which had been influential in the Restoration and b ...

in 1877. Fighting for the maintenance of the samurai

were the hereditary military nobility and officer caste of medieval and early-modern Japan from the late 12th century until their abolition in 1876. They were the well-paid retainers of the '' daimyo'' (the great feudal landholders). They h ...

class and a more virtuous government, their slogan was . It ended with a heroic but total defeat at the Battle of Shiroyama

The took place on 24 September 1877, in Kagoshima, Japan. It was the final battle of the Satsuma Rebellion, where the heavily outnumbered samurai under Saigō Takamori made their last stand against Imperial Japanese Army troops under the comman ...

.Hagiwara, pp. 94–120.

Later depictions

Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored practical imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Although there were ...