Abacus 6.png on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

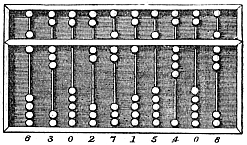

The abacus (''plural'' abaci or abacuses), also called a counting frame, is a calculating tool which has been used since ancient times. It was used in the ancient Near East, Europe,

The abacus (''plural'' abaci or abacuses), also called a counting frame, is a calculating tool which has been used since ancient times. It was used in the ancient Near East, Europe,

The normal method of calculation in ancient Rome, as in Greece, was by moving counters on a smooth table. Originally pebbles (''calculi'') were used. Later, and in medieval Europe,

The normal method of calculation in ancient Rome, as in Greece, was by moving counters on a smooth table. Originally pebbles (''calculi'') were used. Later, and in medieval Europe,

The earliest known written documentation of the Chinese abacus dates to the 2nd century BC.

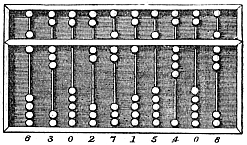

The Chinese abacus, also known as the ''

The earliest known written documentation of the Chinese abacus dates to the 2nd century BC.

The Chinese abacus, also known as the ''

In Japan, the abacus is called '' soroban'' (, lit. "counting tray"). It was imported from China in the 14th century. It was probably in use by the working class a century or more before the ruling class adopted it, as the class structure obstructed such changes. The 1:4 abacus, which removes the seldom-used second and fifth bead became popular in the 1940s.

Today's Japanese abacus is a 1:4 type, four-bead abacus, introduced from China in the

In Japan, the abacus is called '' soroban'' (, lit. "counting tray"). It was imported from China in the 14th century. It was probably in use by the working class a century or more before the ruling class adopted it, as the class structure obstructed such changes. The 1:4 abacus, which removes the seldom-used second and fifth bead became popular in the 1940s.

Today's Japanese abacus is a 1:4 type, four-bead abacus, introduced from China in the

Some sources mention the use of an abacus called a ''nepohualtzintzin'' in ancient Aztec culture. This Mesoamerican abacus used a 5-digit base-20 system. The word Nepōhualtzintzin comes from

Some sources mention the use of an abacus called a ''nepohualtzintzin'' in ancient Aztec culture. This Mesoamerican abacus used a 5-digit base-20 system. The word Nepōhualtzintzin comes from

The Russian abacus, the ''schoty'' (, plural from , counting), usually has a single slanted deck, with ten beads on each wire (except one wire with four beads for quarter- ruble fractions). 4-bead wire was introduced for quarter-

The Russian abacus, the ''schoty'' (, plural from , counting), usually has a single slanted deck, with ten beads on each wire (except one wire with four beads for quarter- ruble fractions). 4-bead wire was introduced for quarter-

Around the world, abacuses have been used in pre-schools and elementary schools as an aid in teaching the numeral system and

Around the world, abacuses have been used in pre-schools and elementary schools as an aid in teaching the numeral system and

File:Gregor Reisch, Margarita Philosophica, 1508 (1230x1615).png

File:Rechentisch.png

File:Rechnung auff der Linihen und Federn.JPG

File:Köbel Böschenteyn 1514.jpg

File:Rechnung auff der linihen 1525 Adam Ries.PNG

File:1543 Robert Recorde.PNG

File:Peter Apian 1544.PNG

File:Adam riesen.jpg

File:Rekenaar 1553.jpg

The binary abacus is used to explain how computers manipulate numbers. The abacus shows how numbers, letters, and signs can be stored in a binary system on a computer, or via ASCII. The device consists of a series of beads on parallel wires arranged in three separate rows. The beads represent a switch on the computer in either an "on" or "off" position.

The binary abacus is used to explain how computers manipulate numbers. The abacus shows how numbers, letters, and signs can be stored in a binary system on a computer, or via ASCII. The device consists of a series of beads on parallel wires arranged in three separate rows. The beads represent a switch on the computer in either an "on" or "off" position.

Min Multimedia

*

Abacus in Various Number Systems

at

Java applet of Chinese, Japanese and Russian abaci

Indian Abacus

{{Authority control Mathematical tools Chinese mathematics Egyptian mathematics Greek mathematics Indian mathematics Japanese mathematics Korean mathematics Roman mathematics

The abacus (''plural'' abaci or abacuses), also called a counting frame, is a calculating tool which has been used since ancient times. It was used in the ancient Near East, Europe,

The abacus (''plural'' abaci or abacuses), also called a counting frame, is a calculating tool which has been used since ancient times. It was used in the ancient Near East, Europe, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, and Russia, centuries before the adoption of the Hindu-Arabic numeral system. The exact origin of the abacus has not yet emerged. It consists of rows of movable beads, or similar objects, strung on a wire. They represent digits. One of the two numbers is set up, and the beads are manipulated to perform an operation such as addition, or even a square or cubic root.

In their earliest designs, the rows of beads could be loose on a flat surface or sliding in grooves. Later the beads were made to slide on rods and built into a frame, allowing faster manipulation. Abacuses are still made, often as a bamboo frame with beads sliding on wires. In the ancient world, particularly before the introduction of positional notation

Positional notation (or place-value notation, or positional numeral system) usually denotes the extension to any base of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system (or decimal system). More generally, a positional system is a numeral system in which the ...

, abacuses were a practical calculating tool. The abacus is still used to teach the fundamentals of mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

to some children, for example, in Russia.

Designs such as the Japanese soroban have been used for practical calculations of up to multi-digit numbers. Any particular abacus design supports multiple methods to perform calculations, including addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and square and cube root

In mathematics, a cube root of a number is a number such that . All nonzero real numbers, have exactly one real cube root and a pair of complex conjugate cube roots, and all nonzero complex numbers have three distinct complex cube roots. Fo ...

s. Some of these methods work with non- natural numbers (numbers such as and ).

Although calculator

An electronic calculator is typically a portable electronic device used to perform calculations, ranging from basic arithmetic to complex mathematics.

The first solid-state electronic calculator was created in the early 1960s. Pocket-sized ...

s and computer

A computer is a machine that can be programmed to Execution (computing), carry out sequences of arithmetic or logical operations (computation) automatically. Modern digital electronic computers can perform generic sets of operations known as C ...

s are commonly used today instead of abacuses, abacuses remain in everyday use in some countries. Merchants, traders, and clerks in some parts of Eastern Europe, Russia, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, and Africa use abacuses. The abacus remains in common use as a scoring system in non- electronic table games. Others may use an abacus due to visual impairment that prevents the use of a calculator.

Etymology

The word ''abacus'' dates to at least AD 1387 when a Middle English work borrowed the word from Latin that described a sandboard abacus. The Latin word is derived from ancient Greek (''abax'') which means something without a base, and colloquially, any piece of rectangular material. Alternatively, without reference to ancient texts on etymology, it has been suggested that it means "a square tablet strewn with dust", or "drawing-board covered with dust (for the use of mathematics)" (the exact shape of the Latin perhaps reflects thegenitive form

In grammar, the genitive case (abbreviated ) is the grammatical case that marks a word, usually a noun, as modifying another word, also usually a noun—thus indicating an attributive relationship of one noun to the other noun. A genitive can al ...

of the Greek word, (''abakos'')). While the table strewn with dust definition is popular, some argue evidence is insufficient for that conclusion. Greek probably borrowed from a Northwest Semitic language

Northwest Semitic is a division of the Semitic languages comprising the indigenous languages of the Levant. It emerged from Proto-Semitic in the Early Bronze Age. It is first attested in proper names identified as Amorite in the Middle Bronze Age ...

like Phoenician, evidenced by a cognate with the Hebrew word ''ʾābāq'' (), or “dust” (in the post-Biblical sense "sand used as a writing surface").

Both ''abacuses'' and ''abaci'' (soft or hard "c") are used as plurals. The user of an abacus is called an ''abacist''.

History

Mesopotamia

TheSumer

Sumer () is the earliest known civilization in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. It is one of the cradles of c ...

ian abacus appeared between 2700–2300 BC. It held a table of successive columns which delimited the successive orders of magnitude of their sexagesimal (base 60) number system.

Some scholars point to a character in Babylonian cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo-syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedge-sha ...

that may have been derived from a representation of the abacus. It is the belief of Old Babylonian scholars, such as Ettore Carruccio, that Old Babylonians "seem to have used the abacus for the operations of addition and subtraction; however, this primitive device proved difficult to use for more complex calculations".

Egypt

Greek historian Herodotus mentioned the abacus in Ancient Egypt. He wrote that the Egyptians manipulated the pebbles from right to left, opposite in direction to the Greek left-to-right method. Archaeologists have found ancient disks of various sizes that are thought to have been used as counters. However, wall depictions of this instrument are yet to be discovered.Persia

At around 600 BC, Persians first began to use the abacus, during theAchaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

. Under the Parthian Parthian may be:

Historical

* A demonym "of Parthia", a region of north-eastern of Greater Iran

* Parthian Empire (247 BC – 224 AD)

* Parthian language, a now-extinct Middle Iranian language

* Parthian shot, an archery skill famously employed by ...

, Sassanian, and Iranian empires, scholars concentrated on exchanging knowledge and inventions with the countries around them – India, China, and the Roman Empire- which is how the abacus may have been exported to other countries.

Greece

The earliest archaeological evidence for the use of the Greek abacus dates to the 5th century BC. Demosthenes (384 BC–322 BC) complained that the need to use pebbles for calculations was too difficult. A play by Alexis from the 4th century BC mentions an abacus and pebbles for accounting, and bothDiogenes

Diogenes ( ; grc, Διογένης, Diogénēs ), also known as Diogenes the Cynic (, ) or Diogenes of Sinope, was a Greek philosopher and one of the founders of Cynicism (philosophy). He was born in Sinope, an Ionian colony on the Black Sea ...

and Polybius

Polybius (; grc-gre, Πολύβιος, ; ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , which covered the period of 264–146 BC and the Punic Wars in detail.

Polybius is important for his analysis of the mixed ...

use the abacus as a metaphor for human behavior, stating "that men that sometimes stood for more and sometimes for less" like the pebbles on an abacus. The Greek abacus was a table of wood or marble, pre-set with small counters in wood or metal for mathematical calculations. This Greek abacus was used in Achaemenid Persia, the Etruscan civilization, Ancient Rome, and the Western Christian world until the French Revolution.

A tablet found on the Greek island Salamis in 1846 AD (the Salamis Tablet

The Salamis Tablet is a marble counting board (an early counting device) dating from around 300 BC, that was discovered on the island of Salamis in 1846. A precursor to the abacus, it is thought that it represents an ancient Greek means of perfo ...

) dates to 300 BC, making it the oldest counting board discovered so far. It is a slab of white marble in length, wide, and thick, on which are 5 groups of markings. In the tablet's center is a set of 5 parallel lines equally divided by a vertical line, capped with a semicircle at the intersection of the bottom-most horizontal line and the single vertical line. Below these lines is a wide space with a horizontal crack dividing it. Below this crack is another group of eleven parallel lines, again divided into two sections by a line perpendicular to them, but with the semicircle at the top of the intersection; the third, sixth and ninth of these lines are marked with a cross where they intersect with the vertical line. Also from this time frame, the Darius Vase

The Darius Vase is a famous vase painted by an anonymous Magna Graecia Apulian vase painter, commonly called the Darius Painter, the most eminent representative at the end of the "Ornate Style" in South Italian red-figure vase painting. The vase ...

was unearthed in 1851. It was covered with pictures, including a "treasurer" holding a wax tablet in one hand while manipulating counters on a table with the other.

Rome

The normal method of calculation in ancient Rome, as in Greece, was by moving counters on a smooth table. Originally pebbles (''calculi'') were used. Later, and in medieval Europe,

The normal method of calculation in ancient Rome, as in Greece, was by moving counters on a smooth table. Originally pebbles (''calculi'') were used. Later, and in medieval Europe, jeton

Jetons or jettons are tokens or coin-like medals produced across Europe from the 13th through the 18th centuries. They were produced as counters for use in calculation on a counting board, a lined board similar to an abacus. They also found use ...

s were manufactured. Marked lines indicated units, fives, tens, etc. as in the Roman numeral system. This system of 'counter casting' continued into the late Roman empire and in medieval Europe and persisted in limited use into the nineteenth century. Due to Pope Sylvester II's reintroduction of the abacus with modifications, it became widely used in Europe again during the 11th century This abacus used beads on wires, unlike the traditional Roman counting boards, which meant the abacus could be used much faster and was more easily moved.

Writing in the 1st century BC, Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 – 27 November 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his ' ...

refers to the wax abacus, a board covered with a thin layer of black wax on which columns and figures were inscribed using a stylus.

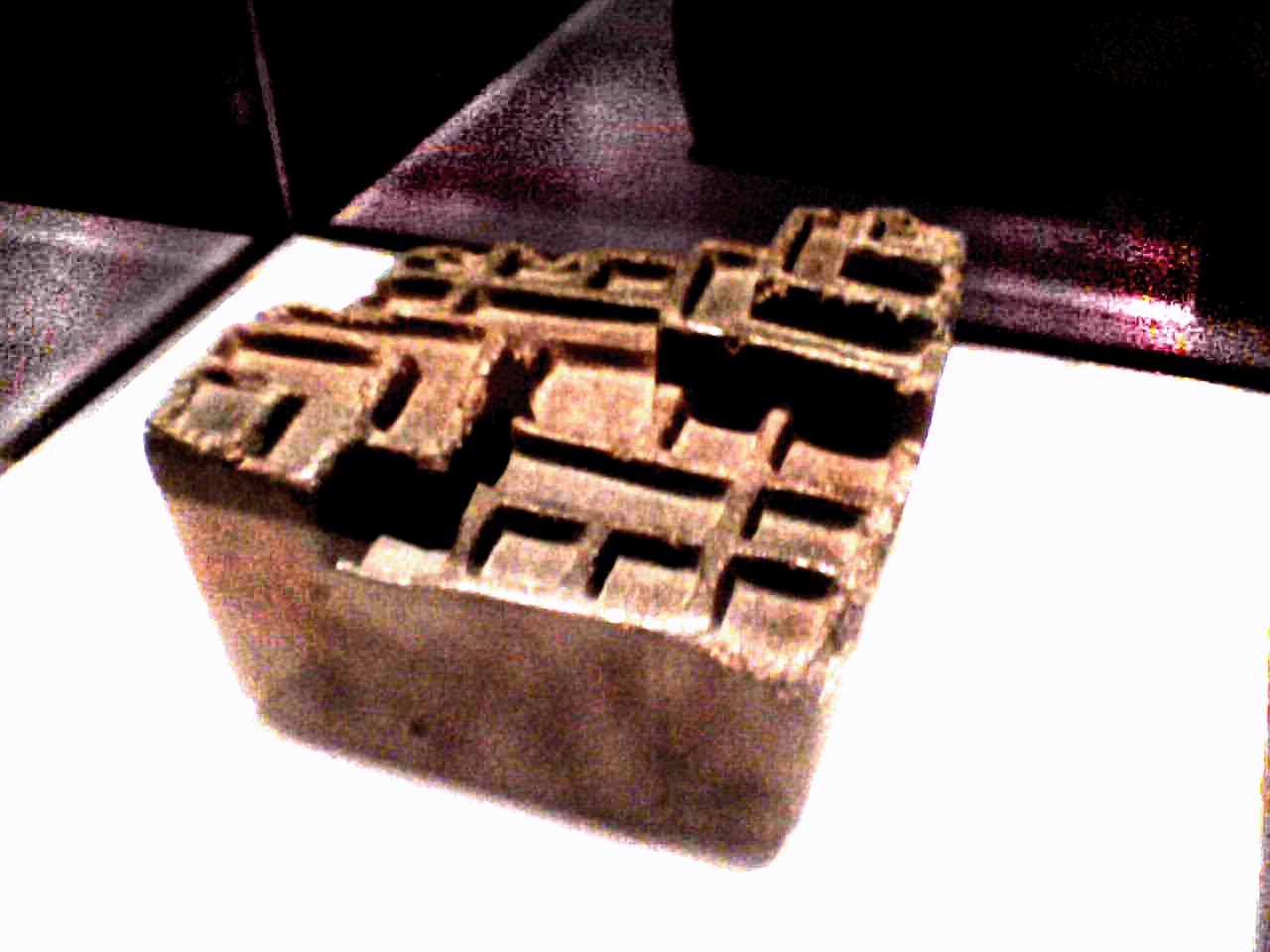

One example of archaeological evidence of the Roman abacus, shown nearby in reconstruction, dates to the 1st century AD. It has eight long grooves containing up to five beads in each and eight shorter grooves having either one or no beads in each. The groove marked I indicates units, X tens, and so on up to millions. The beads in the shorter grooves denote fives –five units, five tens, etc., essentially in a bi-quinary coded decimal

Bi-quinary coded decimal is a numeral encoding scheme used in many abacuses and in some early computers, including the Colossus. The term ''bi-quinary'' indicates that the code comprises both a two-state (''bi'') and a five-state (''quin''ary) ...

system, related to the Roman numerals

Roman numerals are a numeral system that originated in ancient Rome and remained the usual way of writing numbers throughout Europe well into the Late Middle Ages. Numbers are written with combinations of letters from the Latin alphabet, eac ...

. The short grooves on the right may have been used for marking Roman "ounces" (i.e. fractions).

China

The earliest known written documentation of the Chinese abacus dates to the 2nd century BC.

The Chinese abacus, also known as the ''

The earliest known written documentation of the Chinese abacus dates to the 2nd century BC.

The Chinese abacus, also known as the ''suanpan

The suanpan (), also spelled suan pan or souanpan) is an abacus of Chinese origin first described in a 190 CE book of the Eastern Han Dynasty, namely ''Supplementary Notes on the Art of Figures'' written by Xu Yue. However, the exact design ...

'' (算盤/算盘, lit. "calculating tray"), is typically tall and comes in various widths, depending on the operator. It usually has more than seven rods. There are two beads on each rod in the upper deck and five beads each in the bottom one. The beads are usually rounded and made of hardwood

Hardwood is wood from dicot trees. These are usually found in broad-leaved temperate and tropical forests. In temperate and boreal latitudes they are mostly deciduous, but in tropics and subtropics mostly evergreen. Hardwood (which comes from ...

. The beads are counted by moving them up or down towards the beam; beads moved toward the beam are counted, while those moved away from it are not. One of the top beads is 5, while one of the bottom beads is 1. Each rod has a number under it, showing the place value. The ''suanpan'' can be reset to the starting position instantly by a quick movement along the horizontal axis to spin all the beads away from the horizontal beam at the center.

The prototype of the Chinese abacus appeared during the Han Dynasty, and the beads are oval. The Song Dynasty and earlier used the 1:4 type or four-beads abacus similar to the modern abacus including the shape of the beads commonly known as Japanese-style abacus.

In the early Ming Dynasty, the abacus began to appear in a 1:5 ratio. The upper deck had one bead and the bottom had five beads. In the late Ming Dynasty, the abacus styles appeared in a 2:5 ratio. The upper deck had two beads, and the bottom had five.

Various calculation techniques were devised for ''Suanpan'' enabling efficient calculations. Some schools teach students how to use it.

In the long scroll '' Along the River During the Qingming Festival'' painted by Zhang Zeduan during the Song dynasty (960–1297), a ''suanpan'' is clearly visible beside an account book and doctor's prescriptions on the counter of an apothecary's (Feibao).

The similarity of the Roman abacus to the Chinese one suggests that one could have inspired the other, given evidence of a trade relationship between the Roman Empire and China. However, no direct connection has been demonstrated, and the similarity of the abacuses may be coincidental, both ultimately arising from counting with five fingers per hand. Where the Roman model (like most modern Korean and Japanese) has 4 plus 1 bead per decimal place, the standard ''suanpan'' has 5 plus 2. Incidentally, this allows use with a hexadecimal

In mathematics and computing, the hexadecimal (also base-16 or simply hex) numeral system is a positional numeral system that represents numbers using a radix (base) of 16. Unlike the decimal system representing numbers using 10 symbols, hexa ...

numeral system (or any base up to 18) which may have been used for traditional Chinese measures of weight. (Instead of running on wires as in the Chinese, Korean, and Japanese models, the Roman model used grooves, presumably making arithmetic calculations much slower.)

Another possible source of the ''suanpan'' is Chinese counting rods, which operated with a decimal system but lacked the concept of zero as a placeholder. The zero was probably introduced to the Chinese in the Tang dynasty (618–907) when travel in the Indian Ocean and the Middle East would have provided direct contact with India, allowing them to acquire the concept of zero and the decimal point from Indian merchants and mathematicians.

India

The '' Abhidharmakośabhāṣya'' of Vasubandhu (316-396), a Sanskrit work on Buddhist philosophy, says that the second-century CE philosopherVasumitra

Vasumitra (or Sumitra, according to the ''d'' manuscript of the ''Matsya Purana'') (; died 124 BCE), was the fourth ruler of the Shunga Empire of North India. He was the son of Agnimitra by his queen Dharini and brother or half-brother of Vasujye ...

said that "placing a wick (Sanskrit ''vartikā'') on the number one (''ekāṅka'') means it is a one while placing the wick on the number hundred means it is called a hundred, and on the number one thousand means it is a thousand". It is unclear exactly what this arrangement may have been. Around the 5th century, Indian clerks were already finding new ways of recording the contents of the abacus. Hindu texts used the term ''śūnya'' (zero) to indicate the empty column on the abacus.

Japan

Muromachi era

The is a division of Japanese history running from approximately 1336 to 1573. The period marks the governance of the Muromachi or Ashikaga shogunate (''Muromachi bakufu'' or ''Ashikaga bakufu''), which was officially established in 1338 by t ...

. It adopts the form of the upper deck one bead and the bottom four beads. The top bead on the upper deck was equal to five and the bottom one is similar to the Chinese or Korean abacus, and the decimal number can be expressed, so the abacus is designed as a one:four device. The beads are always in the shape of a diamond. The quotient division is generally used instead of the division method; at the same time, in order to make the multiplication and division digits consistently use the division multiplication. Later, Japan had a 3:5 abacus called 天三算盤, which is now in the Ize Rongji collection of Shansi Village in Yamagata City. Japan also used a 2:5 type abacus.

The four-bead abacus spread, and became common around the world. Improvements to the Japanese abacus arose in various places. In China an aluminium frame plastic bead abacus was used. The file is next to the four beads, and pressing the "clearing" button put the upper bead in the upper position, and the lower bead in the lower position.

The abacus is still manufactured in Japan even with the proliferation, practicality, and affordability of pocket electronic calculators. The use of the soroban is still taught in Japanese primary schools as part of mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

, primarily as an aid to faster mental calculation. Using visual imagery can complete a calculation as quickly as a physical instrument.

Korea

The Chinese abacus migrated from China to Korea around 1400 AD. Koreans call it ''jupan'' (주판), ''supan'' (수판) or ''jusan'' (주산). The four-beads abacus (1:4) was introduced during theGoryeo Dynasty

Goryeo (; ) was a Korean kingdom founded in 918, during a time of national division called the Later Three Kingdoms period, that unified and ruled the Korean Peninsula until 1392. Goryeo achieved what has been called a "true national unificati ...

. The 5:1 abacus was introduced to Korea from China during the Ming Dynasty.

Native America

Some sources mention the use of an abacus called a ''nepohualtzintzin'' in ancient Aztec culture. This Mesoamerican abacus used a 5-digit base-20 system. The word Nepōhualtzintzin comes from

Some sources mention the use of an abacus called a ''nepohualtzintzin'' in ancient Aztec culture. This Mesoamerican abacus used a 5-digit base-20 system. The word Nepōhualtzintzin comes from Nahuatl

Nahuatl (; ), Aztec, or Mexicano is a language or, by some definitions, a group of languages of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Varieties of Nahuatl are spoken by about Nahua peoples, most of whom live mainly in Central Mexico and have smaller ...

, formed by the roots; ''Ne'' – personal -; ''pōhual'' or ''pōhualli'' – the account -; and ''tzintzin'' – small similar elements. Its complete meaning was taken as: counting with small similar elements. Its use was taught in the Calmecac to the ''temalpouhqueh'' , who were students dedicated to taking the accounts of skies, from childhood.

The Nepōhualtzintzin was divided into two main parts separated by a bar or intermediate cord. In the left part were four beads. Beads in the first row have unitary values (1, 2, 3, and 4), and on the right side, three beads had values of 5, 10, and 15, respectively. In order to know the value of the respective beads of the upper rows, it is enough to multiply by 20 (by each row), the value of the corresponding count in the first row.

The device featured 13 rows with 7 beads, 91 in total. This was a basic number for this culture. It had a close relation to natural phenomena, the underworld, and the cycles of the heavens. One Nepōhualtzintzin (91) represented the number of days that a season of the year lasts, two Nepōhualtzitzin (182) is the number of days of the corn's cycle, from its sowing to its harvest, three Nepōhualtzintzin (273) is the number of days of a baby's gestation, and four Nepōhualtzintzin (364) completed a cycle and approximated one year. When translated into modern computer arithmetic, the Nepōhualtzintzin amounted to the rank from 10 to 18 in floating point, which precisely calculated large and small amounts, although round off was not allowed.

The rediscovery of the Nepōhualtzintzin was due to the Mexican engineer David Esparza Hidalgo, who in his travels throughout Mexico found diverse engravings and paintings of this instrument and reconstructed several of them in gold, jade, encrustations of shell, etc. Very old Nepōhualtzintzin are attributed to the Olmec culture, and some bracelets of Mayan origin, as well as a diversity of forms and materials in other cultures.

Sanchez wrote in ''Arithmetic in Maya'' that another base 5, base 4 abacus had been found in the Yucatán Peninsula that also computed calendar data. This was a finger abacus, on one hand, 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 were used; and on the other hand 0, 1, 2, and 3 were used. Note the use of zero at the beginning and end of the two cycles.

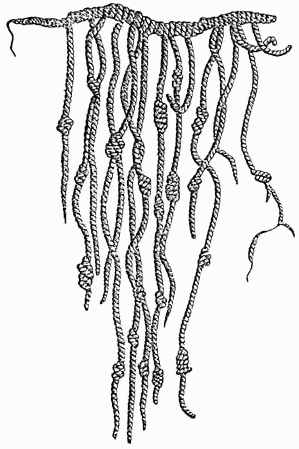

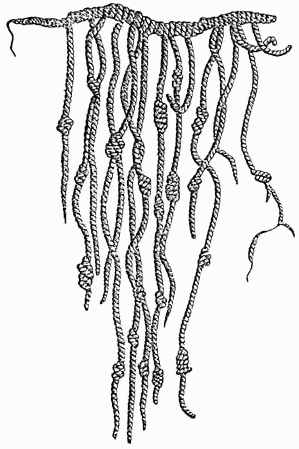

The quipu of the Incas was a system of colored knotted cords used to record numerical data, like advanced tally stick

A tally stick (or simply tally) was an ancient memory aid device used to record and document numbers, quantities and messages. Tally sticks first appear as animal bones carved with notches during the Upper Palaeolithic; a notable example is the ...

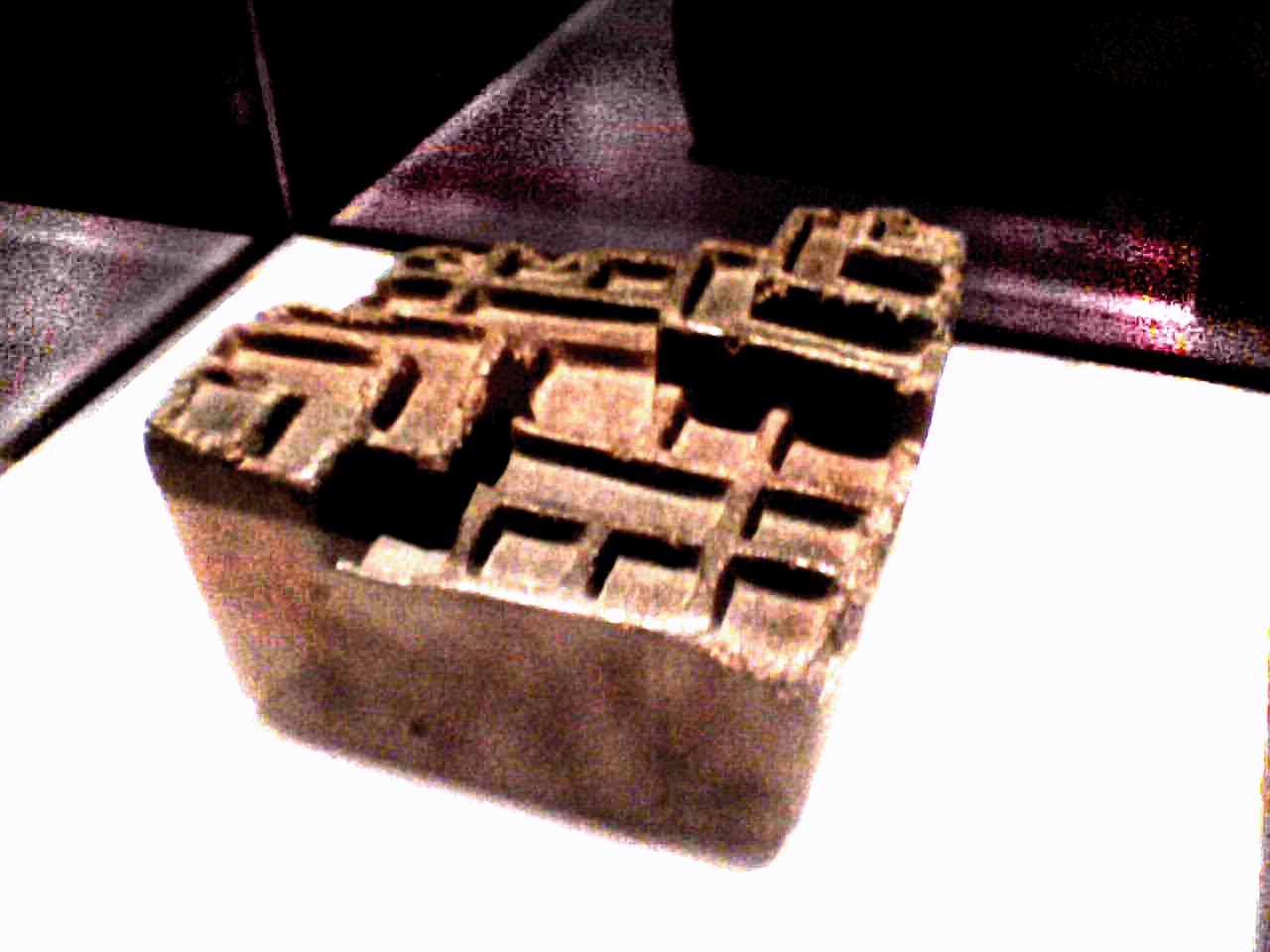

s – but not used to perform calculations. Calculations were carried out using a yupana

A ''yupana'' (from Quechua: ''yupay'' 'count') is an abacus used to perform arithmetic operations, dating back to the time of the Incas.

Types

The term ''yupana'' refers to two distinct classes of objects:

* Table Yupana (or archaeological y ...

( Quechua for "counting tool"; see figure) which was still in use after the conquest of Peru. The working principle of a yupana is unknown, but in 2001 Italian mathematician De Pasquale proposed an explanation. By comparing the form of several yupanas, researchers found that calculations were based using the Fibonacci sequence 1, 1, 2, 3, 5 and powers of 10, 20, and 40 as place values for the different fields in the instrument. Using the Fibonacci sequence would keep the number of grains within any one field at a minimum.

Russia

The Russian abacus, the ''schoty'' (, plural from , counting), usually has a single slanted deck, with ten beads on each wire (except one wire with four beads for quarter- ruble fractions). 4-bead wire was introduced for quarter-

The Russian abacus, the ''schoty'' (, plural from , counting), usually has a single slanted deck, with ten beads on each wire (except one wire with four beads for quarter- ruble fractions). 4-bead wire was introduced for quarter-kopek

The kopek or kopeck ( rus, копейка, p=kɐˈpʲejkə, ukr, копійка, translit=kopiika, p=koˈpʲijkə, be, капейка) is or was a coin or a currency unit of a number of countries in Eastern Europe closely associated with t ...

s, which were minted until 1916. The Russian abacus is used vertically, with each wire running horizontally. The wires are usually bowed upward in the center, to keep the beads pinned to either side. It is cleared when all the beads are moved to the right. During manipulation, beads are moved to the left. For easy viewing, the middle 2 beads on each wire (the 5th and 6th bead) usually are of a different color from the other eight. Likewise, the left bead of the thousands wire (and the million wire, if present) may have a different color.

The Russian abacus was in use in shops and markets throughout the former Soviet Union, and its usage was taught in most schools until the 1990s. Even the 1874 invention of mechanical calculator, Odhner arithmometer, had not replaced them in Russia; according to Yakov Perelman. Some businessmen attempting to import calculators into the Russian Empire were known to leave in despair after watching a skilled abacus operator. Likewise, the mass production of Felix arithmometers since 1924 did not significantly reduce abacus use in the Soviet Union. The Russian abacus began to lose popularity only after the mass production of domestic microcalculators in 1974.

The Russian abacus was brought to France around 1820 by mathematician Jean-Victor Poncelet, who had served in Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's army and had been a prisoner of war in Russia. The abacus had fallen out of use in western Europe in the 16th century with the rise of decimal notation and algorismic methods. To Poncelet's French contemporaries, it was something new. Poncelet used it, not for any applied purpose, but as a teaching and demonstration aid. The Turks and the Armenian people used abacuses similar to the Russian schoty. It was named a ''coulba'' by the Turks and a ''choreb'' by the Armenians.

School abacus

arithmetic

Arithmetic () is an elementary part of mathematics that consists of the study of the properties of the traditional operations on numbers— addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, exponentiation, and extraction of roots. In the 19th ...

.

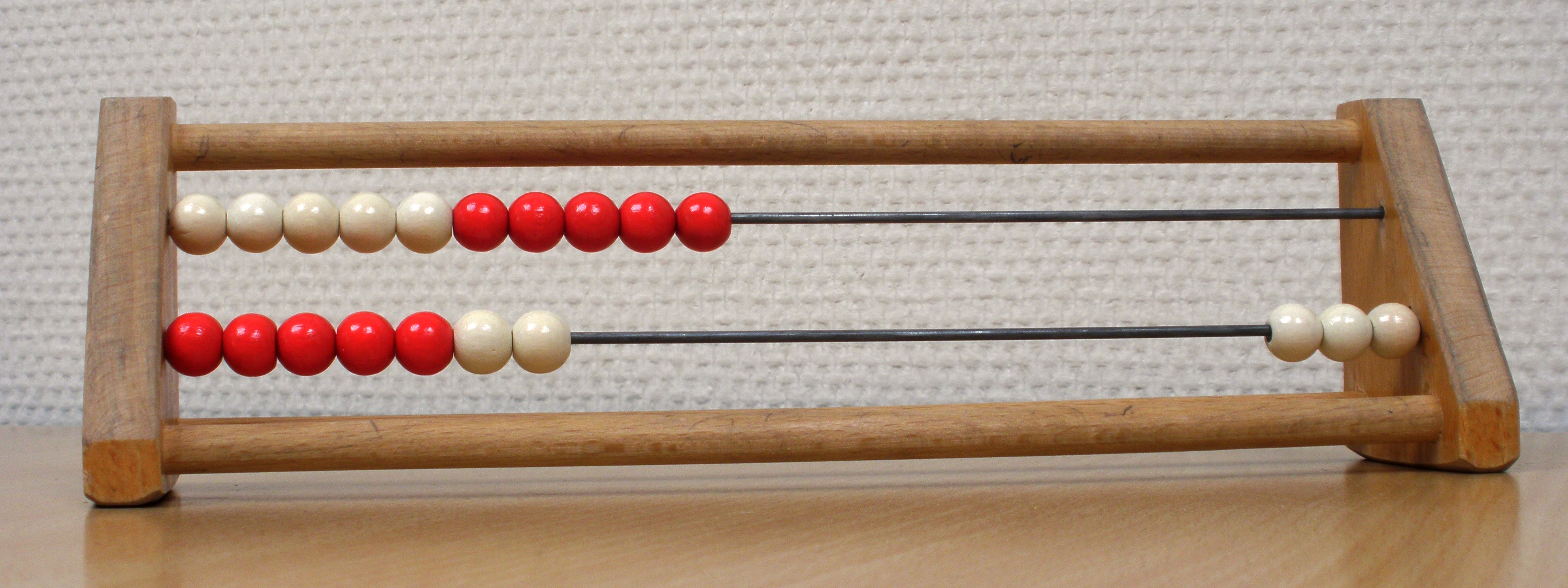

In Western countries, a bead frame similar to the Russian abacus but with straight wires and a vertical frame is common (see image).

The wireframe may be used either with positional notation like other abacuses (thus the 10-wire version may represent numbers up to 9,999,999,999), or each bead may represent one unit (e.g. 74 can be represented by shifting all beads on 7 wires and 4 beads on the 8th wire, so numbers up to 100 may be represented). In the bead frame shown, the gap between the 5th and 6th wire, corresponding to the color change between the 5th and the 6th bead on each wire, suggests the latter use. Teaching multiplication, e.g. 6 times 7, may be represented by shifting 7 beads on 6 wires.

The red-and-white abacus is used in contemporary primary schools for a wide range of number-related lessons. The twenty bead version, referred to by its Dutch name ''rekenrek'' ("calculating frame"), is often used, either on a string of beads or on a rigid framework.

Feynman vs the abacus

Physicist Richard Feynman was noted for facility in mathematical calculations. He wrote about an encounter in Brazil with a Japanese abacus expert, who challenged him to speed contests between Feynman's pen and paper, and the abacus. The abacus was much faster for addition, somewhat faster for multiplication, but Feynman was faster at division. When the abacus was used for a really difficult challenge, i.e. cube roots, Feynman won easily. However, the number chosen at random was close to a number Feynman happened to know was an exact cube, allowing him to use approximate methods.Neurological analysis

Learning how to calculate with the abacus may improve capacity for mental calculation. Abacus-based mental calculation (AMC), which was derived from the abacus, is the act of performing calculations, including addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division, in the mind by manipulating an imagined abacus. It is a high-level cognitive skill that runs calculations with an effective algorithm. People doing long-term AMC training show higher numerical memory capacity and experience more effectively connected neural pathways. They are able to retrieve memory to deal with complex processes. AMC involves both visuospatial and visuomotor processing that generate the visual abacus and move the imaginary beads. Since it only requires that the final position of beads be remembered, it takes less memory and less computation time.Renaissance abacuses

Binary abacus

The binary abacus is used to explain how computers manipulate numbers. The abacus shows how numbers, letters, and signs can be stored in a binary system on a computer, or via ASCII. The device consists of a series of beads on parallel wires arranged in three separate rows. The beads represent a switch on the computer in either an "on" or "off" position.

The binary abacus is used to explain how computers manipulate numbers. The abacus shows how numbers, letters, and signs can be stored in a binary system on a computer, or via ASCII. The device consists of a series of beads on parallel wires arranged in three separate rows. The beads represent a switch on the computer in either an "on" or "off" position.

Visually impaired users

An adapted abacus, invented by Tim Cranmer, and called a Cranmer abacus is commonly used by visually impaired users. A piece of soft fabric or rubber is placed behind the beads, keeping them in place while the users manipulate them. The device is then used to perform the mathematical functions of multiplication, division, addition, subtraction, square root, and cube root. Although blind students have benefited from talking calculators, the abacus is often taught to these students in early grades. Blind students can also complete mathematical assignments using a braille-writer andNemeth code

The Nemeth Braille Code for Mathematics is a Braille code for encoding mathematical and scientific notation linearly using standard six-dot Braille cells for tactile reading by the visually impaired. The code was developed by Abraham Nemeth. Th ...

(a type of braille code for mathematics) but large multiplication and long division problems are tedious. The abacus gives these students a tool to compute mathematical problems that equals the speed and mathematical knowledge required by their sighted peers using pencil and paper. Many blind people find this number machine a useful tool throughout life.

See also

*Chinese Zhusuan Zhusuan (; literally: "bead calculation") is the knowledge and practices of arithmetic calculation through the suanpan or Chinese abacus. In the year 2013, it has been inscribed on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage ...

* Chisanbop

* Logical abacus A logical abacus is a mechanical digital computer.

Also referred to as a "logical machine", the logical abacus is analogous to the ordinary (mathematical) abacus. It is based on the principle of truth tables.

It is constructed to show all the p ...

* Mental abacus

The abacus system of mental calculation is a system where users mentally visualize an abacus to carry out arithmetical calculations. No physical abacus is used; only the answers are written down. Calculations can be made at great speed in this way ...

* Napier's bones

* Sand table

* Slide rule

* Soroban

* Suanpan

The suanpan (), also spelled suan pan or souanpan) is an abacus of Chinese origin first described in a 190 CE book of the Eastern Han Dynasty, namely ''Supplementary Notes on the Art of Figures'' written by Xu Yue. However, the exact design ...

Notes

Footnotes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Reading

* * * * * *External links

*Tutorials

*Min Multimedia

*

Abacus curiosities

*Abacus in Various Number Systems

at

cut-the-knot

Alexander Bogomolny (January 4, 1948 July 7, 2018) was a Soviet-born Israeli-American mathematician. He was Professor Emeritus of Mathematics at the University of Iowa, and formerly research fellow at the Moscow Institute of Electronics and Math ...

Java applet of Chinese, Japanese and Russian abaci

Indian Abacus

{{Authority control Mathematical tools Chinese mathematics Egyptian mathematics Greek mathematics Indian mathematics Japanese mathematics Korean mathematics Roman mathematics