Fidel Castro in the Cuban Revolution on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Cuban communist revolutionary and politician Fidel Castro took part in the

Over the following days, the rebels were rounded up, with some being executed and others – including Castro – transported to a prison north of Santiago. Believing Castro incapable of planning the attack alone, the government accused ''Ortodoxo'' and PSP politicians of involvement, putting 122 defendants on trial on September 21 at the Palace of Justice, Santiago. Although censored from reporting on it, journalists were permitted to attend, which proved an embarrassment for the Batista administration. Acting as his own defense council, Castro convinced the 3 judges to overrule the army's decision to keep all defendants handcuffed in court, proceeding to argue that the charge with which they were accused – of "organizing an uprising of armed persons against the Constitutional Powers of the State" – was incorrect, for they had risen up against Batista, who had seized power in an unconstitutional manner. When asked who was the intellectual author of the attack, Castro claimed that it was the long deceased national icon José Martí, quoting Martí's works that justified uprisings.

The trial revealed that the army had tortured suspects, utilizing castration and the gouging out of eyes; the judges agreed to investigate these crimes, embarrassing the army, which tried unsuccessfully to prevent Castro from testifying any further, claiming he was too ill to leave his cell. The trial ended on October 5, with the acquittal of most defendants; 55 were sentenced to prison terms of between 7 months and 13 years. Castro was sentenced separately, on October 16, during which he delivered a speech that would be printed under the title of ''

Over the following days, the rebels were rounded up, with some being executed and others – including Castro – transported to a prison north of Santiago. Believing Castro incapable of planning the attack alone, the government accused ''Ortodoxo'' and PSP politicians of involvement, putting 122 defendants on trial on September 21 at the Palace of Justice, Santiago. Although censored from reporting on it, journalists were permitted to attend, which proved an embarrassment for the Batista administration. Acting as his own defense council, Castro convinced the 3 judges to overrule the army's decision to keep all defendants handcuffed in court, proceeding to argue that the charge with which they were accused – of "organizing an uprising of armed persons against the Constitutional Powers of the State" – was incorrect, for they had risen up against Batista, who had seized power in an unconstitutional manner. When asked who was the intellectual author of the attack, Castro claimed that it was the long deceased national icon José Martí, quoting Martí's works that justified uprisings.

The trial revealed that the army had tortured suspects, utilizing castration and the gouging out of eyes; the judges agreed to investigate these crimes, embarrassing the army, which tried unsuccessfully to prevent Castro from testifying any further, claiming he was too ill to leave his cell. The trial ended on October 5, with the acquittal of most defendants; 55 were sentenced to prison terms of between 7 months and 13 years. Castro was sentenced separately, on October 16, during which he delivered a speech that would be printed under the title of ''

In 1955, bombings and violent demonstrations led to a crackdown on dissent; Castro was placed under protective armed guard by supporters, before he and Raúl fled the country. MR-26-7 members remaining in Cuba were left to prepare cells for revolutionary action and await Castro's return. He sent a letter to the press, declaring that he was "leaving Cuba because all doors of peaceful struggle have been closed to me. Six weeks after being released from prison I am convinced more than ever of the dictatorship's intention, masked in many ways, to remain in power for twenty years, ruling as now by the use of terror and crime and ignoring the patience of the Cuban people, which has its limits. As a follower of Martí, I believe the hour has come to take our rights and not beg for them, to fight instead of pleading for them." The Castros and several comrades traveled to Mexico, which had a long history of offering asylum to leftist exiles. Here, Raúl befriended an Argentine doctor and Marxist-Leninist named

In 1955, bombings and violent demonstrations led to a crackdown on dissent; Castro was placed under protective armed guard by supporters, before he and Raúl fled the country. MR-26-7 members remaining in Cuba were left to prepare cells for revolutionary action and await Castro's return. He sent a letter to the press, declaring that he was "leaving Cuba because all doors of peaceful struggle have been closed to me. Six weeks after being released from prison I am convinced more than ever of the dictatorship's intention, masked in many ways, to remain in power for twenty years, ruling as now by the use of terror and crime and ignoring the patience of the Cuban people, which has its limits. As a follower of Martí, I believe the hour has come to take our rights and not beg for them, to fight instead of pleading for them." The Castros and several comrades traveled to Mexico, which had a long history of offering asylum to leftist exiles. Here, Raúl befriended an Argentine doctor and Marxist-Leninist named

The ''Granma'' crash-landed in a mangrove swamp at Playa Las Coloradas, close to Los Cayuelos, on 2 December 1956. Within a few hours a naval vessel started bombarding the invaders – fleeing inland, they headed for the forested mountain range of Oriente's

The ''Granma'' crash-landed in a mangrove swamp at Playa Las Coloradas, close to Los Cayuelos, on 2 December 1956. Within a few hours a naval vessel started bombarding the invaders – fleeing inland, they headed for the forested mountain range of Oriente's

The U.S. realized that Batista would lose the war, and fearing that Castro would displace U.S. interests with socialist reforms, decided to aid Batista's removal by supporting a rightist military junta, believing that General Cantillo, then commanding most of the country's armed forces, should lead it. After being approached with this proposal, Cantillo secretly met with Castro, agreeing that the two would call a ceasefire, following which Batista would be apprehended and tried as a war criminal. Double-crossing Castro, Cantillo warned Batista of the revolutionary's intentions. Wishing to avoid a tribunal, Batista resigned on 31 December 1958, informing the armed forces that they were now under Cantillo's control. With his family and closest advisers, Batista fled into exile to the

The U.S. realized that Batista would lose the war, and fearing that Castro would displace U.S. interests with socialist reforms, decided to aid Batista's removal by supporting a rightist military junta, believing that General Cantillo, then commanding most of the country's armed forces, should lead it. After being approached with this proposal, Cantillo secretly met with Castro, agreeing that the two would call a ceasefire, following which Batista would be apprehended and tried as a war criminal. Double-crossing Castro, Cantillo warned Batista of the revolutionary's intentions. Wishing to avoid a tribunal, Batista resigned on 31 December 1958, informing the armed forces that they were now under Cantillo's control. With his family and closest advisers, Batista fled into exile to the

Cuban Revolution

The Cuban Revolution ( es, Revolución Cubana) was carried out after the 1952 Cuban coup d'état which placed Fulgencio Batista as head of state and the failed mass strike in opposition that followed. After failing to contest Batista in co ...

from 1953 to 1959. Following on from his early life, Castro decided to fight for the overthrow of Fulgencio Batista

Fulgencio Batista y Zaldívar (; ; born Rubén Zaldívar, January 16, 1901 – August 6, 1973) was a Cuban military officer and politician who served as the elected president of Cuba from 1940 to 1944 and as its U.S.-backed military dictator ...

's military junta by founding a paramilitary organization, "The Movement". In July 1953, they launched a failed attack on the Moncada Barracks

The Moncada Barracks was a military barracks in Santiago de Cuba, named after General Guillermo Moncada, a hero of the Cuban War of Independence. On 26 July 1953, the barracks was the site of an armed attack by a small group of revolutionaries ...

, during which many militants were killed and Castro was arrested. Placed on trial, he defended his actions and provided his famous "History Will Absolve Me

''History Will Absolve Me'' (Spanish: ''La historia me absolverá'') is the title of a two-hour speech made by Fidel Castro on 16 October 1953. Castro made the speech in his own defense in court against the charges brought against him after he led ...

" speech, before being sentenced to 15 years' imprisonment in the Model Prison on the Isla de Pinos

Isla de la Juventud (; en, Isle of Youth) is the second-largest Cuban island (after Cuba's mainland) and the seventh-largest island in the West Indies (after mainland Cuba itself, Hispaniola, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, Trinidad, and Andro ...

. Renaming his group the " 26th of July Movement" (MR-26-7), Castro was pardoned by Batista's government in May 1955, who no longer considered him a political threat. Restructuring the MR-26-7, he fled to Mexico with his brother Raul Castro

Raul, Raúl and Raül are the Italian, Portuguese, Romanian, Spanish, Galician, Asturian, Basque, Aragonese, and Catalan forms of the Anglo-Germanic given name Ralph or Rudolph. They are cognates of the French Raoul.

Raul, Raúl or Raül may r ...

, where he met with Argentine Marxist-Leninist Che Guevara

Ernesto Che Guevara (; 14 June 1928The date of birth recorded on /upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/78/Ernesto_Guevara_Acta_de_Nacimiento.jpg his birth certificatewas 14 June 1928, although one tertiary source, (Julia Constenla, quot ...

, and together they put together a small revolutionary force intent on overthrowing Batista.

In November 1956, Castro and 81 revolutionaries sailed from Mexico aboard the '' Granma'', crash-landing near to Los Cayuelos. Attacked by Batista's forces, they fled to the Sierra Maestra

The Sierra Maestra is a mountain range that runs westward across the south of the old Oriente Province in southeast Cuba, rising abruptly from the coast. The range falls mainly within the Santiago de Cuba and in Granma Provinces. Some view it a ...

mountain range, where the 19 survivors set up an encampment from which they waged guerrilla war against the army. Boosted by new recruits that increased the guerilla army's numbers to 200, they co-ordinated their attacks with the actions of other revolutionaries across Cuba, and Castro became an international celebrity after being interviewed by ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

''. In 1958, Batista launched a counter-offensive, Operation Verano

Operation Verano (, "Operation Summer") was the name given to the summer offensive in 1958 by the Batista government during the Cuban Revolution, known to the rebels as ''La Ofensiva''. The offensive was designed to crush Fidel Castro's revoluti ...

, but his army's use of conventional warfare was overwhelmed by Castro's guerrilla tactics, and the MR-26-7 eventually pushed out of the Sierra Maestra and took control of most of Oriente and Las Villas

Las Villas is a natural region and ''comarca'' in Andalusia, southern Spain. It is located in the mountainous area at the eastern end of Jaén Province. The main town is Villacarrillo.

Together with the Sierra de Cazorla and Sierra de Segura ...

. Recognising that he was losing the war, Batista fled to the Dominican Republic while military leader Eulogio Cantillo

Eulogio Cantillo Porras (13 September 1911 – 9 September 1978) was a general in the Cuban Army. General Cantillo served as Chief of the Joint Staff during the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, but did not participate in the military coup that ...

took control of the country. With revolutionary forces controlling most of Cuba, Castro ordered Cantillo's arrest, before establishing a new government with Manuel Urrutia Lleó

Manuel Urrutia Lleó (December 8, 1901 – 5 July 1981) was a liberal Cuban lawyer and politician. He campaigned against the Gerardo Machado government and the second presidency of Fulgencio Batista during the 1950s, before serving as president ...

as governor and José Miró Cardona

José Miró Cardona (22 August 1902 – 10 August 1974) was a Cuban politician. He served as Prime Minister for a period of some six weeks in early 1959, following his appointment by President Manuel Urrutia on 5 January 1959. On 13 February ...

as Prime minister (John 234), ensuring that they enacted laws to erode the power of the Batistanos. (Jared 259)

The Movement and the Moncada Barracks attack: 1952–54

In March 1952, Cuban military generalFulgencio Batista

Fulgencio Batista y Zaldívar (; ; born Rubén Zaldívar, January 16, 1901 – August 6, 1973) was a Cuban military officer and politician who served as the elected president of Cuba from 1940 to 1944 and as its U.S.-backed military dictator ...

seized power in a military coup, with the elected President Carlos Prío Socarrás

Carlos Manuel Prío Socarrás (July 14, 1903 – April 5, 1977) was a Cuban politician. He served as the President of Cuba from 1948 until he was deposed by a military coup led by Fulgencio Batista on March 10, 1952, three months before new ele ...

fleeing to Mexico. Declaring himself president, Batista cancelled the planned presidential elections, describing his new system as "disciplined democracy"; Castro, like many others, considered it a one-man dictatorship. Batista developed ties with the United States, severing diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union, suppressing trade unions and persecuting Cuban socialist groups. Intent on opposing Batista's administration, Castro brought several legal cases against them, arguing that Batista had committed sufficient criminal acts to warrant imprisonment and accusing various ministers of breaching labor laws. His lawsuits coming to nothing, Castro began thinking of alternate ways to oust the new government.

Dissatisfied with the '' Partido Ortodoxos non-violent opposition, Castro formed "The Movement", a group consisting of both a civil and a military committee. The former agitated through underground newspaper ''El Acusador'' (''The Accuser''), while the latter armed and trained anti-Batista recruits. With Castro as the Movement's head, the organization was based upon a clandestine cell system, with each cell containing 10 members. A dozen individuals formed the Movement's nucleus, many also dissatisfied ''Ortodoxo'' members, although from July 1952 they went on a recruitment drive, gaining around 1,200 members in a year, organized into over a hundred cells, with the majority coming from Havana's poorer districts. Although he had close ties to revolutionary socialism

Revolutionary socialism is a political philosophy, doctrine, and tradition within socialism that stresses the idea that a social revolution is necessary to bring about structural changes in society. More specifically, it is the view that revolut ...

, Castro avoided an alliance with the communist PSP, fearing it would frighten away political moderates, but kept in contact with several PSP members, including his brother Raúl. He later related that the Movement's members were simply anti-Batista, and few had strong socialist or anti-imperialist views, something which Castro attributed to "the overwhelming weight of the Yankees' ideological and advertising machinery" which he believed suppressed class consciousness

In Marxism, class consciousness is the set of beliefs that a person holds regarding their social class or economic rank in society, the structure of their class, and their class interests. According to Karl Marx, it is an awareness that is key to ...

among Cuba's working class.

Castro stockpiled weapons for a planned attack on the Moncada Barracks

The Moncada Barracks was a military barracks in Santiago de Cuba, named after General Guillermo Moncada, a hero of the Cuban War of Independence. On 26 July 1953, the barracks was the site of an armed attack by a small group of revolutionaries ...

, a military garrison outside Santiago de Cuba

Santiago de Cuba is the second-largest city in Cuba and the capital city of Santiago de Cuba Province. It lies in the southeastern area of the island, some southeast of the Cuban capital of Havana.

The municipality extends over , and contains ...

, Oriente. Castro's militants intended to dress in army uniforms and arrive at the base on July 25, the festival of St James, when many officers would be away. The rebels would seize control, raid the armory and escape before reinforcements arrived. Supplied with new weaponry, Castro intended to arm supporters and spark a revolution among Oriente's impoverished cane cutters. The plan was to then seize control of a Santiago radio station, broadcasting the Movement's manifesto, hence promoting further uprisings. Castro's plan emulated those of the 19th century Cuban independence fighters who had raided Spanish barracks; Castro saw himself as the heir to independence leader and national hero José Martí

José Julián Martí Pérez (; January 28, 1853 – May 19, 1895) was a Cuban nationalist, poet, philosopher, essayist, journalist, translator, professor, and publisher, who is considered a Cuban national hero because of his role in the libera ...

.

Castro gathered 165 revolutionaries for the mission; 138 stationed in Santiago, the other 27 in Bayamo. Mostly young men from Havana and Pinar del Río

Pinar del Río is the capital city of Pinar del Río Province, Cuba. With a population of 139,336 (2004) in a municipality of 190,332, it is the 10th-largest city in Cuba. Inhabitants of the area are called ''Pinareños''.

History

Pinar del R� ...

, Castro insured that – with the exception of himself – none had children, and ordered his troops not to cause bloodshed unless they met armed resistance. The attack took place on July 26, 1953, but ran into trouble; 3 of the 16 cars that had set out from Santiago failed to get there. Reaching the barracks, the alarm was raised, with most of the rebels pinned down outside the base by machine gun fire. Those that got inside faced heavy resistance, and 4 were killed before Castro ordered a retreat. The rebels had suffered 6 fatalities and 15 other casualties, whilst the army suffered 19 dead and 27 wounded.

Meanwhile, some rebels took over a civilian hospital; subsequently stormed by government soldiers, the rebels were rounded up, tortured and 22 were executed without trial. Those that had escaped, including Fidel and Raúl, assembled at their base where some debated surrender, while others wished to flee to Havana. Accompanied by 19 comrades, Castro decided to set out for Gran Piedra in the rugged Sierra Maestra

The Sierra Maestra is a mountain range that runs westward across the south of the old Oriente Province in southeast Cuba, rising abruptly from the coast. The range falls mainly within the Santiago de Cuba and in Granma Provinces. Some view it a ...

mountains several miles to the north, where they could establish a guerrilla base. In response to the Moncada attack, Batista's government proclaimed martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

, ordering a violent crackdown on dissent and imposing strict censorship of the media. Propaganda broadcast misinformation about the event, claiming that the rebels were communists who had killed hospital patients. Despite this censorship, news and photographs soon spread of the army's use of torture and summary executions in Oriente, causing widespread public and some governmental disapproval.

Trial and ''History Will Absolve Me'': 1953

Over the following days, the rebels were rounded up, with some being executed and others – including Castro – transported to a prison north of Santiago. Believing Castro incapable of planning the attack alone, the government accused ''Ortodoxo'' and PSP politicians of involvement, putting 122 defendants on trial on September 21 at the Palace of Justice, Santiago. Although censored from reporting on it, journalists were permitted to attend, which proved an embarrassment for the Batista administration. Acting as his own defense council, Castro convinced the 3 judges to overrule the army's decision to keep all defendants handcuffed in court, proceeding to argue that the charge with which they were accused – of "organizing an uprising of armed persons against the Constitutional Powers of the State" – was incorrect, for they had risen up against Batista, who had seized power in an unconstitutional manner. When asked who was the intellectual author of the attack, Castro claimed that it was the long deceased national icon José Martí, quoting Martí's works that justified uprisings.

The trial revealed that the army had tortured suspects, utilizing castration and the gouging out of eyes; the judges agreed to investigate these crimes, embarrassing the army, which tried unsuccessfully to prevent Castro from testifying any further, claiming he was too ill to leave his cell. The trial ended on October 5, with the acquittal of most defendants; 55 were sentenced to prison terms of between 7 months and 13 years. Castro was sentenced separately, on October 16, during which he delivered a speech that would be printed under the title of ''

Over the following days, the rebels were rounded up, with some being executed and others – including Castro – transported to a prison north of Santiago. Believing Castro incapable of planning the attack alone, the government accused ''Ortodoxo'' and PSP politicians of involvement, putting 122 defendants on trial on September 21 at the Palace of Justice, Santiago. Although censored from reporting on it, journalists were permitted to attend, which proved an embarrassment for the Batista administration. Acting as his own defense council, Castro convinced the 3 judges to overrule the army's decision to keep all defendants handcuffed in court, proceeding to argue that the charge with which they were accused – of "organizing an uprising of armed persons against the Constitutional Powers of the State" – was incorrect, for they had risen up against Batista, who had seized power in an unconstitutional manner. When asked who was the intellectual author of the attack, Castro claimed that it was the long deceased national icon José Martí, quoting Martí's works that justified uprisings.

The trial revealed that the army had tortured suspects, utilizing castration and the gouging out of eyes; the judges agreed to investigate these crimes, embarrassing the army, which tried unsuccessfully to prevent Castro from testifying any further, claiming he was too ill to leave his cell. The trial ended on October 5, with the acquittal of most defendants; 55 were sentenced to prison terms of between 7 months and 13 years. Castro was sentenced separately, on October 16, during which he delivered a speech that would be printed under the title of ''History Will Absolve Me

''History Will Absolve Me'' (Spanish: ''La historia me absolverá'') is the title of a two-hour speech made by Fidel Castro on 16 October 1953. Castro made the speech in his own defense in court against the charges brought against him after he led ...

''. Although the maximum penalty for leading an uprising was a 20 years, Castro was sentenced to 15, being imprisoned in the hospital wing of the Model Prison (''Presidio Modelo

The Presidio Modelo was a "model prison" with panopticon design, built on the Isla de Pinos ("Isle of Pines"), now the Isle of Youth, Isla de la Juventud ("Isle of Youth"), in Cuba. It is located in the suburban quarter of Chacón, Nueva Gerona ...

''), a relatively comfortable and modern institution on the Isla de Pinos

Isla de la Juventud (; en, Isle of Youth) is the second-largest Cuban island (after Cuba's mainland) and the seventh-largest island in the West Indies (after mainland Cuba itself, Hispaniola, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, Trinidad, and Andro ...

, 60 miles off of Cuba's southwest coast.

Imprisonment and the 26th of July Movement: 1953–55

Imprisoned with 25 fellow conspirators, Castro renamed "The Movement" the " 26th of July Movement" (MR-26-7) in memory of the Moncada attack's date. Forming a school for prisoners, the Abel Santamaría Ideological Academy, Castro organized five hours a day of teaching in ancient and modern history, philosophy and English. He read widely, enjoying the works ofKarl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

, Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

, and Martí but also reading books by Freud, Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and aest ...

, Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

, Munthe, Maugham and Dostoyevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (, ; rus, Фёдор Михайлович Достоевский, Fyódor Mikháylovich Dostoyévskiy, p=ˈfʲɵdər mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪdʑ dəstɐˈjefskʲɪj, a=ru-Dostoevsky.ogg, links=yes; 11 November 18219 ...

, analyzing them within a Marxist framework. He began reading about Roosevelt's New Deal, believing that something similar should be enacted in Cuba. Corresponding with supporters outside of prison, he maintained control over the Movement and organized the publication of ''History Will Absolve Me'', with an initial print run of 27,500 copies. Initially permitted a relatively high amount of freedom within the prison compared to other inmates, he was locked up in solitary confinement after his comrades sang anti-Batista songs on a visit by the President in February 1954. Meanwhile, Castro's wife Mirta gained employment in the Ministry of the Interior, having been encouraged to do so by her brother, a friend and ally of Batista's. This was kept a secret from Castro, who found out through a radio announcement. Appalled, he raged that he would rather die "a thousand times" than "suffer impotently from such an insult". Both Fidel and Mirta initiated divorce proceedings, with Mirta taking custody of their son Fidelito; this angered Castro, who did not want his son growing up in a bourgeois environment.

In 1954, Batista's government held presidential elections, but no politician had risked standing against him; he won, but the election was widely considered fraudulent. It had allowed some political opposition to be voiced, and Castro's supporters had agitated for an amnesty for the Moncada incident's perpetrators. Some politicians suggested an amnesty would be good publicity, and the Congress and Batista agreed. Backed by the U.S. and major corporations, Batista believed Castro to be no political threat, and on May 15, 1955 the prisoners were released. Returning to Havana, Castro was carried on the shoulders of supporters, and set about giving radio interviews and press conferences; the government closely monitored him, curtailing his activities. Now divorced, Castro had sexual affairs with two female supporters, Naty Revuelta and Maria Laborde, each conceiving him a child. Setting about strengthening the MR-26-7, he established an 11-person National Directorate; despite these structural changes, there was still dissent, with some questioning Castro's autocratic leadership. Castro dismissed calls for the leadership to be transferred to a democratic board, arguing that a successful revolution could not be run by committee. Some then abandoned the MR-26-7, labeling Castro a ''caudillo

A ''caudillo'' ( , ; osp, cabdillo, from Latin , diminutive of ''caput'' "head") is a type of personalist leader wielding military and political power. There is no precise definition of ''caudillo'', which is often used interchangeably with " ...

'' (dictator), although the majority remained loyal.

Mexico and guerrilla training: 1955–56

In 1955, bombings and violent demonstrations led to a crackdown on dissent; Castro was placed under protective armed guard by supporters, before he and Raúl fled the country. MR-26-7 members remaining in Cuba were left to prepare cells for revolutionary action and await Castro's return. He sent a letter to the press, declaring that he was "leaving Cuba because all doors of peaceful struggle have been closed to me. Six weeks after being released from prison I am convinced more than ever of the dictatorship's intention, masked in many ways, to remain in power for twenty years, ruling as now by the use of terror and crime and ignoring the patience of the Cuban people, which has its limits. As a follower of Martí, I believe the hour has come to take our rights and not beg for them, to fight instead of pleading for them." The Castros and several comrades traveled to Mexico, which had a long history of offering asylum to leftist exiles. Here, Raúl befriended an Argentine doctor and Marxist-Leninist named

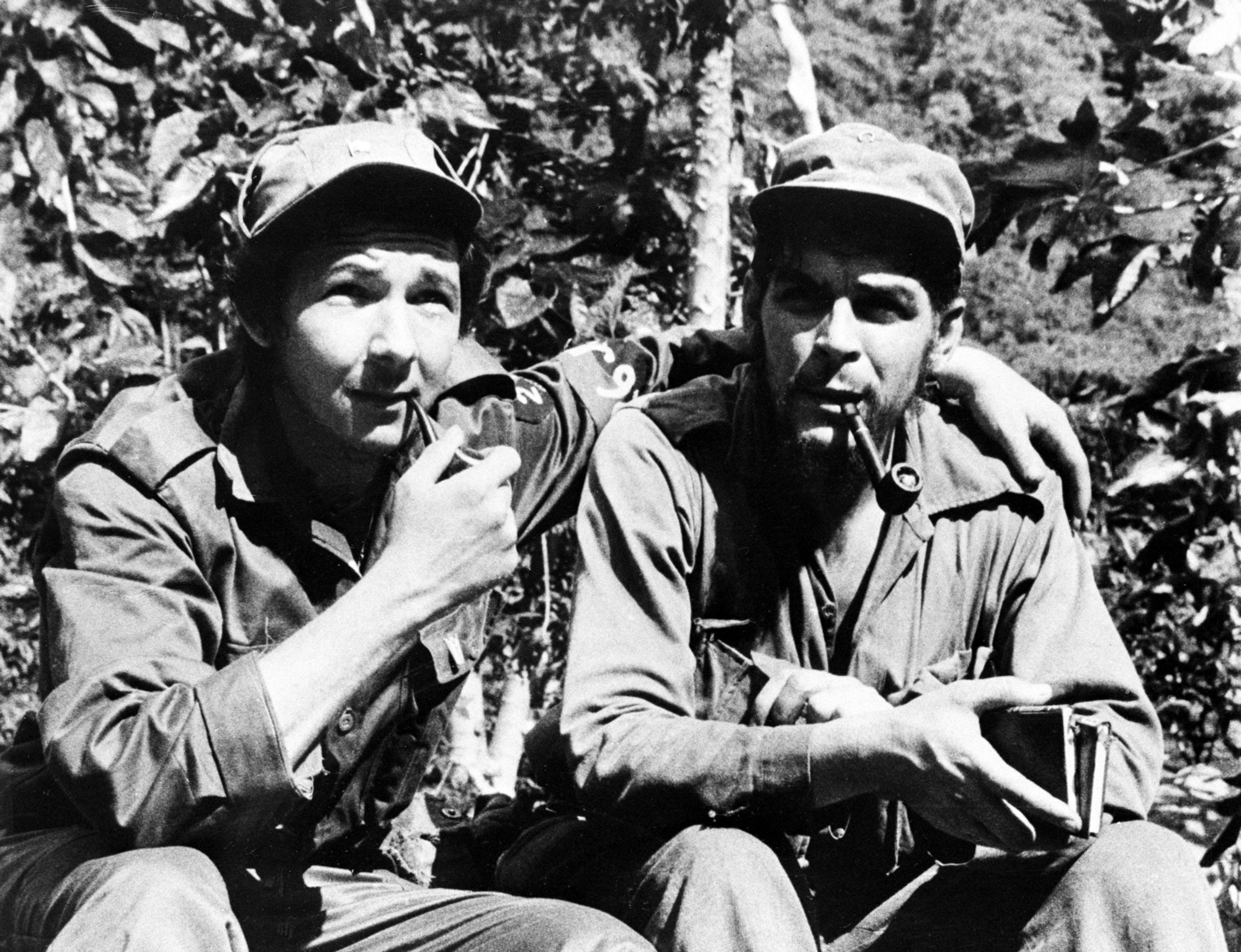

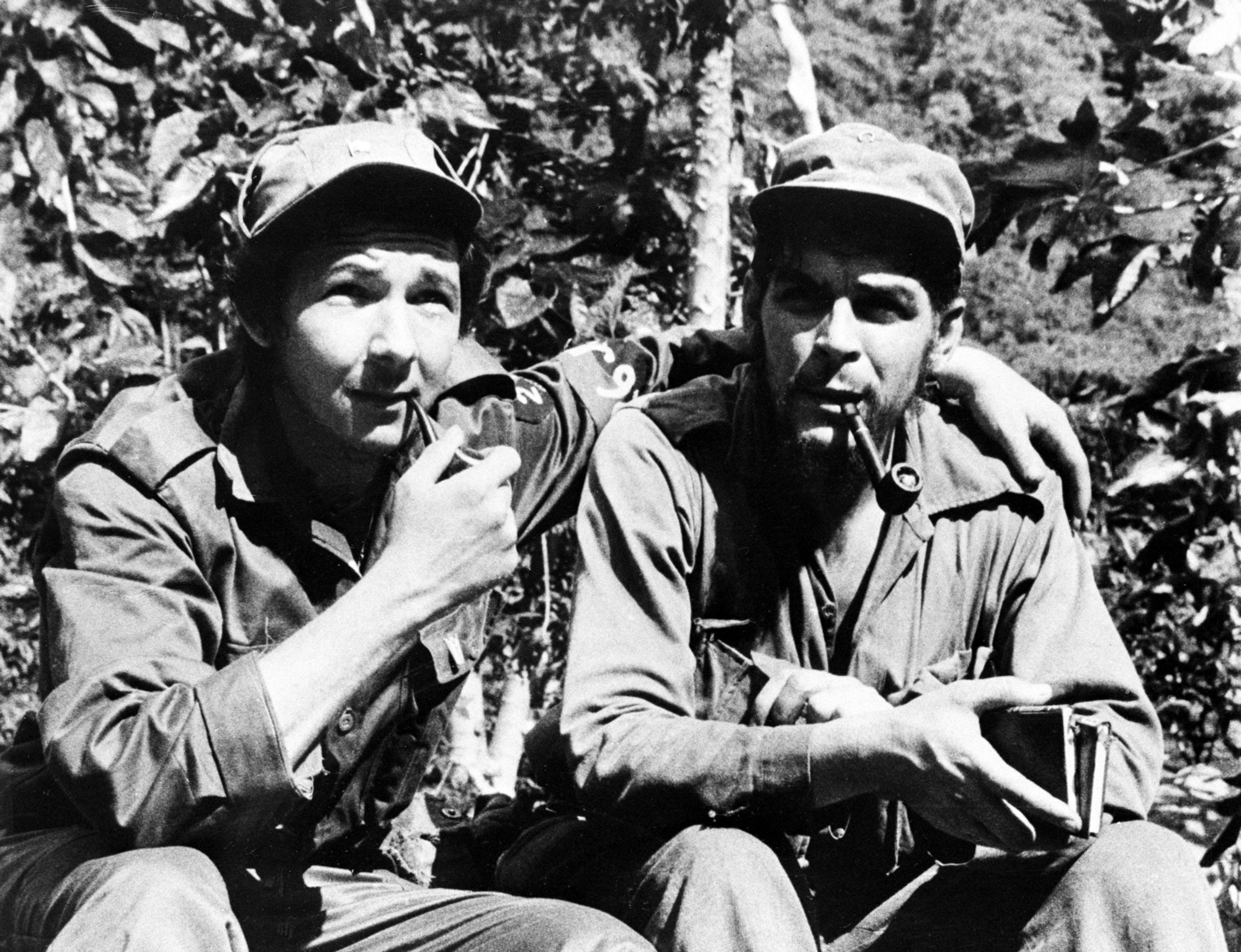

In 1955, bombings and violent demonstrations led to a crackdown on dissent; Castro was placed under protective armed guard by supporters, before he and Raúl fled the country. MR-26-7 members remaining in Cuba were left to prepare cells for revolutionary action and await Castro's return. He sent a letter to the press, declaring that he was "leaving Cuba because all doors of peaceful struggle have been closed to me. Six weeks after being released from prison I am convinced more than ever of the dictatorship's intention, masked in many ways, to remain in power for twenty years, ruling as now by the use of terror and crime and ignoring the patience of the Cuban people, which has its limits. As a follower of Martí, I believe the hour has come to take our rights and not beg for them, to fight instead of pleading for them." The Castros and several comrades traveled to Mexico, which had a long history of offering asylum to leftist exiles. Here, Raúl befriended an Argentine doctor and Marxist-Leninist named Ernesto "Che" Guevara

Ernesto Che Guevara (; 14 June 1928The date of birth recorded on /upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/78/Ernesto_Guevara_Acta_de_Nacimiento.jpg his birth certificatewas 14 June 1928, although one tertiary source, (Julia Constenla, quoted ...

, a proponent of guerrilla warfare keen to join Cuba's Revolution. Fidel liked him, later describing him as "a more advanced revolutionary than I was." Castro also associated with the Spaniard Alberto Bayo

Alberto Bayo y Giroud (27 March 1892 – 4 August 1967) was a Cuban military commander of the Republican faction during the Spanish Civil War. His most significant action during the war was the attempted invasion of the Nationalist-held islands ...

, a Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

veteran of the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, link ...

; Bayo agreed to teach Fidel's rebels the necessary skills in guerrilla warfare, clandestinely meeting them at Chapultepec

Chapultepec, more commonly called the "Bosque de Chapultepec" (Chapultepec Forest) in Mexico City, is one of the largest city parks in Mexico, measuring in total just over 686 hectares (1,695 acres). Centered on a rock formation called Chapultep ...

for training.

Requiring funding, Castro toured the U.S. in search of wealthy sympathizers; Prío contributed $100,000. Castro later claimed that he had been monitored by Batista's agents, who orchestrated a failed assassination against him. Batista's government bribed Mexican police to arrest the rebels, however with the support of several Mexican politicians who were sympathetic to their cause, they were soon released. Castro kept in contact with the MR-26-7 in Cuba, where they had gained a large support base in Oriente. Other militant anti-Batista groups had sprung up, primarily from the student movement; most notable was the Directorio Revolucionario Estudantil (DRE), founded by the Federation of University Students (FEU) President José Antonio Echevarría. Antonio traveled to Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital city, capital and primate city, largest city of Mexico, and the List of North American cities by population, most populous city in North Amer ...

to meet with Castro, but they disagreed on tactics; Antonio thought that it was legitimate to assassinate anyone connected to the government, something Castro thought rash and ineffective.

After purchasing a decrepit yacht, the '' Granma'', on 25 November 1956 Castro set sail from Tuxpan

Tuxpan (or Túxpam, fully Túxpam de Rodríguez Cano) is both a municipality and city located in the Mexican state of Veracruz. The population of the city was 78,523 and of the municipality was 134,394 inhabitants, according to the INEGI census ...

, Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

, with 81 revolutionaries armed with 90 rifles, 3 machine guns, around 40 pistols and 2 hand-held anti-tank guns. The 1,200 mile crossing to Cuba was harsh, and in the overcrowded conditions of the ship, many suffered seasickness

Motion sickness occurs due to a difference between actual and expected motion. Symptoms commonly include nausea, vomiting, cold sweat, headache, dizziness, tiredness, loss of appetite, and increased salivation. Complications may rarely include d ...

, and food supplies ran low. At some points they had to bail water caused by a leak, and at another a man fell overboard, delaying their journey. The plan had been for the crossing to take 5 days, and on the ship's scheduled day of arrival, 30 November, MR-26-7 members under Frank Pais led an armed uprising against government buildings in Santiago, Manzanillo and several other towns. However, the ''Granmas journey ultimately lasted 7 days, and with Castro and his men unable to provide reinforcements, Pais and his militants dispersed after two days of intermittent attacks.

Guerrilla war in the Sierra Maestra: 1956–58

Sierra Maestra

The Sierra Maestra is a mountain range that runs westward across the south of the old Oriente Province in southeast Cuba, rising abruptly from the coast. The range falls mainly within the Santiago de Cuba and in Granma Provinces. Some view it a ...

. At daybreak on 5 December, a detachment of Batista's Rural Guard attacked them; the rebels scattered, making their journey to the Sierra Maestra in small groups. Upon arrival, Castro discovered that of the 82 rebels who had arrived on the ''Granma'', only 19 had made it to their destination, the rest having been killed or captured.

Setting up an encampment

Camp may refer to:

Outdoor accommodation and recreation

* Campsite or campground, a recreational outdoor sleeping and eating site

* a temporary settlement for nomads

* Camp, a term used in New England, Northern Ontario and New Brunswick to descri ...

in the jungle, the survivors, including the Castros, Che Guevara, and Camilo Cienfuegos, began launching raids on small army-posts to obtain weaponry. In January 1957 they overran the outpost near to the beach at La Plata; Guevara treated the soldiers for any injuries, but the revolutionaries executed the local ''mayoral'' (land-company overseer) Chicho Osorio, whom the local peasants despised and who boasted of killing one of the MR-26-7 rebels several weeks previously. Osorio's execution aided the rebels in gaining the trust of locals, who typically hated the ''mayorals'' as enforcers of the wealthy landowners, although they largely remained unenthusiastic and suspicious of the revolutionaries. As trust grew, some locals joined the rebels, although most new recruits came from urban areas. With increasing numbers of volunteers, who now numbered over 200, in July 1957 Castro divided his army into three columns, keeping charge of one and giving control of the others to his brother and Guevara. The MR-26-7 members operating in urban areas continued agitation, sending supplies to Castro, and on 16 February 1957 he met with other senior members to discuss tactics; here he met Celia Sánchez, who would become a close friend.

Across Cuba, militant groups rose up against Batista, carrying out bombings and acts of sabotage. Police responded with mass arrests, torture and extrajudicial killings, with corpses hung on trees to intimidate dissidents. In March 1957, Antonio's DR launched a failed attack on the presidential palace, with Antonio being shot dead; his death removed a charismatic rival to Castro's leadership of the revolution. Frank Pais was also killed, leaving Castro the unchallenged leader of the MR-26-7. Castro hid his Marxist-Leninist beliefs, in contrast to Guevara and Raúl, whose beliefs were well known; in doing so, he hoped to gain the support of less radical dissenters, and in 1957 he met with leading members of the ''Partido Ortodoxo''. Castro and ''Ortodoxo'' leaders Raúl Chibás and Felipe Pazos

Felipe Pazos Roque (September 27, 1912 – February 26, 2001) was a Cuban economist who initially supported the Cuban Revolution of Fidel Castro, but became disillusioned with the increasingly radical nature of the revolutionary government. Born in ...

drafted and signed the Sierra Maestra Manifesto, in which they laid out their plans for a post-Batista Cuba. Rejecting the rule of a provisional military junta, it demanded the setting up of a provisional civilian government "supported by all" which would implement moderate agrarian reform, industrialization and a literacy campaign before introducing "truly fair, democratic, impartial, elections".

Batista's government censored the Cuban press, and so Castro contacted foreign media to spread his message. Herbert Matthews

Herbert Lionel Matthews (January 10, 1900 – July 30, 1977) was a reporter and editorialist for ''The New York Times'' who, at the age of 57, won widespread attention after revealing that the 30-year-old Fidel Castro was still alive and living i ...

, a journalist from ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'', interviewed Castro, attracting international interest to the rebel's cause and turning Castro into a celebrity

Celebrity is a condition of fame and broad public recognition of a person or group as a result of the attention given to them by mass media. An individual may attain a celebrity status from having great wealth, their participation in sports ...

. Under the disguise of a wealthy American sugar owner, Matthews and Castro’s men were able to slip by Batista’s men posted near the Sierra Maestra

The Sierra Maestra is a mountain range that runs westward across the south of the old Oriente Province in southeast Cuba, rising abruptly from the coast. The range falls mainly within the Santiago de Cuba and in Granma Provinces. Some view it a ...

mountain. Upon meeting with Castro, he detailed the events that occurred since December 2, 1956. Months beforehand, the US media spread news that Castro had died in the midst of the failed Granma landing in Oriente Province on December 2, 1956. Instead, Castro and the rest of the survivors retreated to the Sierra Mountains and had since been engaged in guerilla warfare with Batista military. The New York Times published the article on February 24, 1957, letting the rest of the world, including US embassy officials, know for the first time that Castro was indeed alive.

Other reporters followed, sent by such news agencies as CBS

CBS Broadcasting Inc., commonly shortened to CBS, the abbreviation of its former legal name Columbia Broadcasting System, is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the CBS Entertainm ...

, while a reporter from ''Paris Match

''Paris Match'' () is a French-language weekly news magazine. It covers major national and international news along with celebrity lifestyle features.

History and profile

A sports news magazine, ''Match l'intran'' (a play on '' L'Intransigeant ...

'' stayed with the rebels for around 4 months, documenting their routine.

Castro's guerrillas increased their attacks on military outposts, forcing the government to withdraw from the Sierra Maestra region, and by spring 1958 the rebels controlled a hospital, schools, a printing press, slaughterhouse, land-mine factory and a cigar-making factory.

Batista's fall and Cantillo's military junta: 1958–1959

Batista had come under increasing pressure by 1958. His army's military failures, coupled with his press censorship and the police and army's use of torture and extrajudicial executions, were increasingly criticized both domestically and abroad. Influenced by anti-Batista sentiment among their citizens, the U.S. government ceased supplying him with weaponry, leading him to buy arms from the United Kingdom. The opposition used this opportunity to call a general strike, accompanied by armed attacks from the MR-26-7. Beginning on 9 April, it received strong support in central and eastern Cuba, but little elsewhere. Batista responded with an all-out-attack on Castro's guerrillas, ''Operation Verano

Operation Verano (, "Operation Summer") was the name given to the summer offensive in 1958 by the Batista government during the Cuban Revolution, known to the rebels as ''La Ofensiva''. The offensive was designed to crush Fidel Castro's revoluti ...

'' (28 June to 8 August 1958). The army aerially bombarded forested areas and villages suspected of aiding the militants, while 10,000 soldiers under the command of General Eulogio Cantillo

Eulogio Cantillo Porras (13 September 1911 – 9 September 1978) was a general in the Cuban Army. General Cantillo served as Chief of the Joint Staff during the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, but did not participate in the military coup that ...

surrounded the Sierra Maestra, driving north to the rebel encampments. Despite their numerical and technological superiority, the army had no experience with guerrilla warfare or with the mountainous region. Now with 300 men at his command, Castro avoided open confrontation, using land mines and ambushes to halt the enemy offensive. The army suffered heavy losses and a number of embarrassments; in June 1958 a battalion surrendered, their weapons were confiscated and they were handed over to the Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure respect for all human beings, and ...

. Many of Batista's soldiers, appalled at the human rights abuses that they were ordered to carry out, defected to Castro's rebels, who also benefited from popular support in the areas they controlled. In the summer, the MR-26-7 went on the offensive, pushing the army back, out of the mountain range and into the lowlands, with Castro using his columns in a pincer movement to surround the main army concentration in Santiago. By November, Castro's forces controlled most of Oriente and Las Villas, and tightened their grip around the capitals of Santiago and Santa Clara. Through control of Las Villas, the rebels divided Cuba in two by closing major roads and rail lines, severely disadvantaging Batista's forces.

The U.S. realized that Batista would lose the war, and fearing that Castro would displace U.S. interests with socialist reforms, decided to aid Batista's removal by supporting a rightist military junta, believing that General Cantillo, then commanding most of the country's armed forces, should lead it. After being approached with this proposal, Cantillo secretly met with Castro, agreeing that the two would call a ceasefire, following which Batista would be apprehended and tried as a war criminal. Double-crossing Castro, Cantillo warned Batista of the revolutionary's intentions. Wishing to avoid a tribunal, Batista resigned on 31 December 1958, informing the armed forces that they were now under Cantillo's control. With his family and closest advisers, Batista fled into exile to the

The U.S. realized that Batista would lose the war, and fearing that Castro would displace U.S. interests with socialist reforms, decided to aid Batista's removal by supporting a rightist military junta, believing that General Cantillo, then commanding most of the country's armed forces, should lead it. After being approached with this proposal, Cantillo secretly met with Castro, agreeing that the two would call a ceasefire, following which Batista would be apprehended and tried as a war criminal. Double-crossing Castro, Cantillo warned Batista of the revolutionary's intentions. Wishing to avoid a tribunal, Batista resigned on 31 December 1958, informing the armed forces that they were now under Cantillo's control. With his family and closest advisers, Batista fled into exile to the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares with ...

with over US$300,000,000. Cantillo then entered Havana's Presidential Palace, proclaimed the Supreme Court judge Carlos Piedra

Carlos Manuel Piedra y Piedra (or Carlos Modesto Piedra y Piedra) (1895–1988) was a Cuban politician who served as the Interim President of Cuba for a single day (January 2–3, 1959) during the transition of power between Fulgencio Batista and r ...

as the new President, and began appointing new members of the government.

Still in Oriente, Castro was furious. Recognizing the establishment of a military junta, he ended the ceasefire and continued on the offensive. The MR-26-7 put together a plan to oust the Cantillo-Piedra junta, freeing the high-ranking military officer Colonel Ramón Barquín from the Isle of Pines prison (where he had been held captive for plotting to overthrow Batista), and commanding him to fly to Havana to arrest Cantillo. Accompanying widespread celebrations as news of Batista's downfall spread across Cuba on 1 January 1959, Castro ordered the MR-26-7 to take responsibility for policing the country, in order to prevent widespread looting and vandalism.

Whilst Cienfuegos and Guevara led their columns into Havana on 2 January, Castro entered Santiago, accepting the surrender of the Moncada Barracks and giving a speech invoking the wars of independence. He spoke out against the Cantillo-Piedra junta, called for justice against human rights abusers and proclaimed a better era for women's rights. Heading toward Havana, he met José Antonio Echevarría's mother, and greeted cheering crowds in every town, giving press conferences and interviews. Foreign journalists commented on the unprecedented level of public adulation, with Castro striking a heroic "Christ-like figure" and wearing a medallion of the Virgin Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Joseph and the mother of ...

. One such journalist, Herbert L. Matthews, spoke highly of Castro, noting his charisma and sharp, political mind frame. Comments like these helped shape the positive image Castro had during this era.

Provisional government: 1959

Castro had made his opinion clear that lawyerManuel Urrutia Lleó

Manuel Urrutia Lleó (December 8, 1901 – 5 July 1981) was a liberal Cuban lawyer and politician. He campaigned against the Gerardo Machado government and the second presidency of Fulgencio Batista during the 1950s, before serving as president ...

should become president, leading a provisional civilian government following Batista's fall. Politically moderate, Urrutia had defended MR-26-7 revolutionaries in court, arguing that the Moncada Barracks attack was legal according to the Cuban constitution. Castro believed Urrutia would make a good leader, being both established yet sympathetic to the revolution. With the leaders of the junta under arrest, Urrutia was proclaimed provisional president on 2 January 1959, Urrutia had been chosen because of his prestige and acceptability to both the moderate middle-class backers of the revolution and to the guerrilla forces who took part in the alliance formed in Caracas in 1958. with Castro erroneously announcing he had been selected by "popular election"; most of Urrutia's cabinet were MR-26-7 members. On January 8, 1959, Castro's army entered Havana. Proclaiming himself Representative of the Rebel Armed Forces of the Presidency, Castro – along with close aides and family members – set up home and office in the penthouse of the Havana Hilton Hotel, there meeting with journalists, foreign visitors and government ministers.

Officially having no role in the provisional government, Castro exercised a great deal of influence, largely because of his popularity and control of the rebel army. Ensuring the government implemented policies to cut corruption and fight illiteracy, he did not initially force through any radical proposals. Attempting to rid Cuba's government of Batistanos, the Congress elected under Batista was abolished, and all those elected in the rigged elections of 1954 and 1958 were banned from politics. The government now ruling by decree, Castro pushed the president to issue a temporary ban on all political parties, but repeatedly stated that they would get around to organizing multiparty elections; this never occurred. He began meeting members of the Popular Socialist Party, believing they had the intellectual capacity to form a socialist government, but repeatedly denied being a communist himself.

In suppressing the revolution, Batista's government had orchestrated mass human rights abuses, with most estimates for the death toll typically placing it at around 20,000. Popular uproar across Cuba demanded that those figures who had been complicit in the widespread torture and killing of civilians be brought to justice. Although remaining a moderating force and opposing the mass reprisal killings advocated by many, Castro helped set-up trials of many Batistanos, resulting in hundreds of executions. Although widely popular domestically, critics – in particular from the U.S. press – argued that many were not fair trial

A fair (archaic: faire or fayre) is a gathering of people for a variety of entertainment or commercial activities. Fairs are typically temporary with scheduled times lasting from an afternoon to several weeks.

Types

Variations of fairs incl ...

s, and condemned Cuba's government as being more interested in vengeance than justice. In response, Castro proclaimed that "revolutionary justice is not based on legal precepts, but on moral conviction", organizing the first Havana trial to take place before a mass audience of 17,000 at the Sports Palace stadium. He also intervened in other trials to ensure that what he saw as "revolutionary justice" was carried out; when a group of aviators accused of bombing a village were found not guilty at a trial in Santiago de Cuba

Santiago de Cuba is the second-largest city in Cuba and the capital city of Santiago de Cuba Province. It lies in the southeastern area of the island, some southeast of the Cuban capital of Havana.

The municipality extends over , and contains ...

, Castro ordered a retrial in which they were found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Acclaimed across Latin America, Castro traveled to Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

to attend the first-anniversary celebrations of Marcos Pérez Jiménez

Marcos Evangelista Pérez Jiménez (25 April 1914 – 20 September 2001) was a Venezuelan military and general officer of the Army of Venezuela and the dictator of Venezuela from 1950 to 1958, ruling as member of the military junta from 19 ...

's overthrow. Meeting President-elect Rómulo Betancourt

Rómulo Ernesto Betancourt Bello (22 February 1908 – 28 September 1981; ), known as "The Father of Venezuelan Democracy", was the president of Venezuela, serving from 1945 to 1948 and again from 1959 to 1964, as well as leader of Acción De ...

, Castro proposed greater relations between the two nations, unsuccessfully requesting a loan of $300,000,000 and a new deal for Venezuelan oil. Returning home, an argument between Castro and senior government figures broke out; the government had banned the National Lottery and closed down the casinos and brothels, leaving thousands of waiters, croupiers and prostitutes unemployed, infuriating Castro. As a result, Prime Minister José Miró Cardona

José Miró Cardona (22 August 1902 – 10 August 1974) was a Cuban politician. He served as Prime Minister for a period of some six weeks in early 1959, following his appointment by President Manuel Urrutia on 5 January 1959. On 13 February ...

resigned, going into exile in the U.S. and joining the anti-Castro movement.; ; .

References

Footnotes

Bibliography

* * * * * {{Fidel Castro Fidel Castro